Abstract

This paper looks at how a Finnish music trio and its audience managed to reconcile locality and globality during a Christmas concert streamed through Facebook Live amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. It does so as this pandemic forced the numerous and hugely popular Christmas concerts in Finland that are usually held in churches and other venues to move online, where musicians were now not just addressing local, Finnish-speaking listeners but a global audience. Specifically, I examine how both the musicians and the audience constructed this Christmas-at-home concert as a distinctly translocal event through adopting various multilingual practices that enabled them to experience local and global senses of identity and community. Using an online ethnographic perspective, which combines discourse-centred online ethnography with analytic autoethnography, I discuss transcripts of the musicians’ spoken discourse, written comments from the audience in Facebook Live’s chat, and excerpts from an interview with one of the musicians to showcase the translocality of digital communication; the translocality of Finnish culture; and the translocality of the Christmas and the Christmas-at-home experience in pandemic times.

Abstrakti

Tässä artikkelissa tarkastellaan, kuinka suomalainen musiikkitrio ja sen yleisö onnistuivat yhdistämään paikallisuuden ja globaalisuuden joulukonsertissa, joka suoratoistettiin Facebook Liven kautta COVID-19-pandemian aikana. Pandemian seurauksena lukuisat, laajasti suositut joulukonsertit, jotka Suomessa järjestetään tyypillisesti kirkoissa ja muissa esiintymispaikoissa, siirtyivät verkkoon. Näin ollen muusikot eivät enää esiintyneet ainoastaan paikalliselle suomenkieliselle yleisölle, vaan myös globaalille katsojakunnalle. Tutkin erityisesti sitä, kuinka sekä muusikot että yleisö rakensivat Joulu kotona-konsertin selkeästi translokaaliseksi tapahtumaksi hyödyntämällä erilaisia monikielisiä käytänteitä, jotka mahdollistivat sekä paikallisen että globaalin identiteetin ja yhteisöllisyyden kokemuksen. Hyödynnän verkkotutkimuksellista lähestymistapaa, joka yhdistää diskurssikeskeisen verkkoetnografian ja analyyttisen autoetnografian. Analysoin muusikoiden puheesta tehtyjä transkriptioita, yleisön kirjallisia kommentteja Facebook Liven keskustelussa sekä otteita yhden muusikon haastattelusta. Näiden avulla tarkastelen digitaalisen viestinnän translokaalisuutta, suomalaisen kulttuurin translokaalisuutta sekä joulun ja Joulu kotona-kokemuksen translokaalisuutta pandemian aikana.

1 Introduction

The goal of this paper is to explore translocality[1] from the point of view of multilingualism in digital communication. Drawing on Nederveen Pieterse (1995) and Leppänen et al. (2009), Kytölä (2016: 372) explains that, in digital communication, “translocality is manifest in the enhanced connectivity afforded by burgeoning digital technologies and the semiotic (often linguistic, multilingual) choices that people make to identify themselves and to orient to their audiences ranging in the continuum between local and global”. Having as a point of departure Miller’s (2017: 422) argument that contemporary Christmas is “the most local and the most global festival,” this paper looks at how a Finnish music trio and its audience managed to reconcile locality and globality during a Christmas concert streamed through Facebook Live amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The participants (artists and audience) in the event could communicate not just with their local peers but also with people from very different geographical, national, ethnic, cultural and linguistic backgrounds. For them, Facebook Live did not just constitute an abstract global space isolated from their offline localities; on the contrary, Facebook Live can be viewed as a space where their diverse, often scattered globally, local practices encountered each other in processes which entailed the negotiation of locally defined meanings (see Tagg and Seargeant 2014: 181, based on Blommaert 2010).

Finland is a country closely associated with Christmas. During the Christmas festive season, which in its current form has evolved through a fusion of indigenous pre-Christian customs with imported Christian traditions, numerous and hugely popular concerts are held in churches and other venues across Finland where choirs and musicians perform Christmas carols in the Finnish language (Hebert et al. 2012: 403). For Finnish people, these concerts are tantamount to rituals that both preserve traditions and mediate the cultural and societal transformations of contemporary Finland (Hebert et al. 2012: 420).

In December 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the concomitant lockdowns of venues and tour cancellations, several Finnish Christmas concerts were alternatively held online via various platforms. In this fashion, not only people who reside in Finland but also people from all over the world had the opportunity to go through the Finnish Christmas carols ritual.

The Finnish Christmas concert I zoom in on herein was called Joulu Kotona (Finnish for ‘Christmas at home’) and was performed by Juha-Pekka (JP) Leppäluoto (vocals, acoustic guitar), Elias Kahila (cello) and Samuli Erkkilä (electric guitar, vocals). The concert was live streamed on Leppäluoto’s official Facebook page, via the facility of Facebook Live, on Sunday 20 December 2020. One of the most commendable features of the event was that in-between songs Kahila was wishing “Merry Christmas” in different languages while reading out messages that members of the audience from around the world had written on the stream’s chat section. This initiated a vibrant multilingual exchange between the musicians and the audience, constituting an excellent occasion to examine how translocality is practically done. More precisely, it was found that translocality in Joulu Kotona manifested in the participants’ multilingual practices, which involved language choice, code-switching, and metalinguistic discourses. With the above in mind, I aim to address the following questions:

What languages did the musicians and the audience choose to employ during the livestream of Joulu Kotona?

What were the motivations behind and the functions of their language choices?

What stances (i.e. thoughts, feelings, beliefs and values) did they express in relation to the languages used during the livestream?

What identities were constructed at a translocal level within the multilingual context of Joulu Kotona and how?

Theoretically, my study is situated within the sociolinguistic and discourse-analytical cohort, and more specifically, within the strand of online multilingualism (e.g. Androutsopoulos 2015b; Lee 2017; Leppänen and Peuronen 2012), that is, how individuals select and employ multiple languages in digital communication settings to achieve their contextually and communally significant goals (Leppänen and Peuronen 2012).[2] Existing literature has extensively explored multilingualism in written online discourse, such as email messages, chatroom/IM interactions, forum and blog posts, and Facebook status updates (for succinct reviews of relevant studies, see Lee 2017; Leppänen and Sultana 2023). However, there has been little discussion on multilingualism in spoken online discourse, such as vlogs on YouTube and videoconferencing/VoIP interactions in platforms like Zoom and Skype. It is hoped that the current study will offer a fresh perspective on existing knowledge on translocality by examining Joulu Kotona’s multilingualism in the artists’ spoken discourse and the audience’s written discourse as well as the intertwining of these two types of discourse as enabled by Facebook Live affordances. In so doing, the study may well have a bearing on previous scholarship within media culture studies on the shift towards more personal connections between musicians and audiences due to digital communication platforms (see Baym 2018). Methodologically, I adopt an online ethnographic perspective, which combines premises from discourse-centred online ethnography (Androutsopoulos 2008) and analytic autoethnography (Anderson 2006), since I was an active (non-Finnish) member of Joulu Kotona’s audience.

The paper is structured as follows: I start with an overview of key concepts and analytic orientations of the study. I then discuss research methods, data, and the context of Joulu Kotona. I continue with the analysis, which is divided into two parts: 1) choosing languages during Joulu Kotona, and 2) talking about languages during Joulu Kotona. I conclude with a discussion of the findings and their implications.

2 Key concepts and analytic orientations

As already mentioned, translocality in Joulu Kotona was performed through language choice, code-switching practices and metalinguistic discourses. Commencing with language choice, the term deals with the codes or linguistic resources (e.g. languages, scripts, speech, emojis, visual images, gestures, voice) at the disposal of online users and how they negotiate their code choices when interacting with others who may or may not share the same resources (Lee 2017: 23). Code-switching online is understood as a process whereby a single user draws upon two or more linguistic resources in a single discourse or multiple discourses (Lee 2017: 40).[3] As Androutsopoulos (2007: 340–341) explains, the study of language choice operates on a macro-level casting light on the linguistic repertoires of a(n) (online) community, pointing to contexts where multilingualism occurs. The study of code-switching operates on a micro-level focusing on these contexts, examining, for instance, the co-existence of different linguistic codes in the same message; different structural patterns of code-switching; and different discourse functions of code-switching (Androutsopoulos 2007: 340–341; Lee 2017: 38). Recent research (as cited in Androutsopoulos 2015b; Lee 2017) recognizes that code-switching in digital communication, as has been the case in offline environments, plays a crucial role in shaping social relationships and constructing identities, across various platforms, synchronously and asynchronously, privately and publicly, with diverse audiences and through a multitude of resources as mentioned above. As will be shown in the analysis, language choice and code-switching allowed Joulu Kotona participants to reveal multiple allegiances to places of belonging. With respect to metalinguistic discourses, these pertain to how people talk or write about language(s).[4] These discourses can be produced by anyone, irrespective of whether they have a formal background in linguistics or knowledge of different languages. With the advent of the internet, people now have an unprecedented space to express their lay perspectives on language matters (Lee 2017; Rymes and Leone 2014). Paying attention to the metalinguistic discourses produced by Joulu Kotona participants provides a window into how they negotiated their translocal identities. By means of such discourses, they positioned themselves and others as experts/learners of another culture’s language system just as they expressed their appreciation for local cultural practices (i.e. Finnish Christmas carols) even though they did not understand that culture’s language. Overall, talking about languages served the social function of boosting and widening participation in Joulu Kotona’s translocal community.

In order to explore the translocal identities performed in Joulu Kotona, I draw on Adaskou and colleagues’ (1990) typology on the dimensions of culture as modified by Stamou (2020: 57–58). Focusing on particular aspects of a local culture allows us to explore how people manifest their interest in, knowledge of and/or adherence to that culture or even multiple cultures at the same time. The aforementioned typology distinguishes between four dimensions of culture: aesthetic, sociological, semantic and sociolinguistic. The aesthetic dimension of culture pertains to cultural elements of high aesthetic, intellectual, historical or philosophical value (e.g. art, music, literature). In my analysis, the aesthetic dimension comprised references to ethnonyms (e.g. Finnish) and toponyms (e.g. Vanaja Church), Finnish songs and significant cultural events (e.g. Raskasta Joulua; see note 7). The sociological dimension of culture explores the cultural aspects present in everyday life. As highlighted by Stamou (2020: 57), cultural values and meanings are not confined to the realm of art but are also manifest in everyday life (e.g. manners and customs, the weather, food) and the behavioural patterns that characterize each country/culture. Put it differently, this dimension relates to a more socio-anthropological understanding of culture. In my dataset, the sociological dimension was detected in references to Christmas cultural practices along with references to patterns of mentality and behaviour linked to Finland (e.g. melancholy). The semantic dimension of culture relates to the conceptual systems linked to a specific country or culture and expressed through its language (e.g. the concepts of time, space). This dimension was not traced in my data. The sociolinguistic dimension of culture concerns the communicative conventions, rhetorical schemes and stylistic levels of a culture’s language system. In the analysis, I examine how non-Finnish participants use Finnish to index Finnishness and other languages to index other local identities (e.g. Spanish, Polish).

Lastly, I employ the concept of stance-taking, which feeds into Adaskou et al.’s (1990) typology and also proved to be a significant linchpin for the analysis of Joulu Kotona’s metalinguistic discourses. Attending to people’s stance enables us to identify how they (in)directly express their feelings (affective stance) and/or thoughts (epistemic stance) about a particular target (Du Bois 2007, Jaffe 2009), such as, among other things, whether a particular practice (like Finnish music, Christmas carols) is ‘global’ or ‘local’. A central notion pertinent to stance-taking is that of alignment or disalignment, as proposed by Du Bois (2007), namely, our agreement or disagreement with the attitudes and beliefs of others. Stance-taking is always a means of self-presentation and social judgment, conveying information about ourselves and others, indicating thus their similarity or dissimilarity to us.

The next section describes the methods, data, and ethics of the study as well as the overall context of Joulu Kotona.

3 Research context

3.1 Methods and data

This is an ‘ethnographically informed study’ (Barton and Lee 2017: 146) in which my position is that of an insider. To conduct my research from an insider perspective, I synthesized premises from analytic autoethnography and discourse-centred online ethnography.

According to Anderson (2006), the key features of analytic autoethnography are that the researcher is (1) a full member in the research setting; (2) visible as such a member in the sense that their feelings and experiences are incorporated into the study and considered as crucial data for comprehending the social world being observed; and (3) committed to contributing to the elaboration and extension of theoretical understanding. I come from Greece and my native language is Greek. I have a C2 level of English, a B1 level of Spanish and an A2 level of Finnish.[5] As a discourse analyst-sociolinguist, I focus on the intersection of discourse, social media and society, specializing in the construction of identities. It should be stressed from the outset that I actively participated in Joulu Kotona without initially intending to study it. I have been an ardent fan of the Finnish metal scene and of Leppäluoto’s work since mid-2000s.[6] At some point in 2010, I listened to Leppäluoto singing in Finnish the song Sydäntalvella (‘In the heart of the winter’). Such was my fondness of the specific song that I instantly started learning Finnish in my home country. Throughout the years, I have developed deep respect for the Finnish culture by and large. In 2013–2014, I lived in Jyväskylä, Finland, as a visiting researcher. There I attended a live performance of Raskasta Joulua,[7] a Finnish Christmas concert featuring Leppäluoto as a key singer. Regarding Joulu Kotona, I watched the entire livestreamed event and actively engaged in the chat by offering comments and reactions (e.g. Like and Love) to the artists and fellow viewers. The idea to explore the multilingual discourse of Joulu Kotona sparked my interest within the first half-hour of the livestream. I got fascinated by Joulu Kotona’s cellist, Elias Kahila, as he was wishing to the audience in various languages, igniting a dynamic interaction between artists and viewers and between members of the audience. In sum, I position myself in this study as an ‘aca-fan’ (Jenkins 1992) – an academic who openly identifies as a fan of Leppäluoto’s music and Finnish carols.

I also elicited an insider perspective by drawing on the discourse-centred online ethnographic paradigm (Androutsopoulos 2008) which combines online ethnography with discourse analysis. This approach encompasses screen-based observations of online discourse and direct interactions with the producers of this discourse through interviews, whether in person or mediated via email, instant messaging, or VoIP services.

I started my preliminary observation of Joulu Kotona’s discourse in real time, right after the streaming had started. Although my initial aim was to enjoy the Finnish carols while in lockdown, I was alert to spot certain aspects (in the artists’ interaction and chat comments) that merited analysis. My systematic observation occurred after the streaming had concluded, and for the period it was available online (see below), with repeated viewings of the concert and multiple readings of the viewers’ comments. For information concerning the viewers whose comments were analyzed, such as their nationality, gender, place of residence and linguistic repertoires, I anchored in my systematic ethnographic observation and knowledge as a member of Leppäluoto’s fans online community on Facebook and Instagram. As part of the screen-based dimension of the study, my data included transcripts of selected extracts of spoken discourse produced by the musicians between songs along with comments posted by the audience in Facebook Live’s chat. The chat communication yielded 2,687 comments in total, with 19 of them posted after the end of the streaming. The comments were exported using the service ExportComments (https://exportcomments.com/). As far as the participant-based dimension of the study is concerned, I conducted (in English) via email an interview with Elias Kahila. I sent him an initial message on September 12, 2021, explaining the purposes of my project and posing him a series of questions that revolved around what inspired him to wish “Merry Christmas” in different languages; the criteria upon which he chose to wish in specific languages; and the idea to read aloud fans’ comments. He provided his responses in writing via a lengthy email message (approximately 1,800 words) on September 13, 2021. His written responses have been rendered intact in the present paper. The interview dataset was complemented by field notes from my self-observation and the viewers’ observation of activities and practices surrounding Joulu Kotona’s multilingual discourse. For presenting and discussing the data, the following conventions have been used throughout the analysis: data from the interview are enumerated as Interview with Kahila (1), Interview with Kahila (2) etc.; data from the artists’ interaction as Artists’ spoken discourse (1), Artists’ spoken discourse (2) etc.; and data from the chat as Facebook Live Chat (1), Facebook Live chat (2) etc.

3.2 Data processing

The analysis started with an inductive process of coding and re-coding of the data until conceptual groupings and explanatory categories in relation to the aims of the study emerged from the data themselves. The main discourse practices I discerned in the Joulu Kotona dataset were (see also next section, on the discursive, linguistic and cultural context of the event): introductory greetings, expression of wishes, replies to Kahila’s multilingual wishes and talk about cultural practices (Christmas in Finland, Christmas in other places, Finnish carols, carols in other places, wearing woolen socks in Finland during winter, the Joulu Kotona livestream).

My next step was to identify in these discourse practices which languages were used, who used them (musicians, members of the audience) and who they wished to address. I initially spotted the co-existence of different languages in the same message (e.g. Spanish and Finnish) and then I looked into different structural patterns of code-switching (e.g. whole parts of the musicians’ interaction switched to English; an international viewer’s comment in English and Finnish where Finnish was reserved for referring to Finnish cultural practices) and different discourse functions of code-switching (e.g. viewers using English to exchange greetings with each other and Finnish to thank the musicians). For the use of Finnish, specifically, by non-Finnish viewers, I paid attention to references to Finnish names, ethnonyms and toponyms, Finnish songs, and Finnish cultural practices and events, in line with Adaskou et al.’s (1990) aesthetic dimension of culture. I also examined cases of multilingual activities which were carried out without involving multiple languages (e.g. a Ukrainian viewer writing in English about a Finnish carol based on a Ukrainian one).

Throughout the stream and the interview with Kahila, viewers and artists expressed a range of perceptions, thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and values associated with cultural practices and languages, including Kahila’s multilingual wishing. The means I chose to analyze these instances was stance (see also Section 2). I particularly focused on the use of evaluative adjectives (e.g. ‘good’), evaluative adverbs (e.g. ‘amazingly’), emotive verbs (e.g. ‘enjoy’), cognitive verbs (e.g. ‘understand’), tropes (e.g. metonymy, simile), interjections (‘Dios mío!!!’ - my god, Bravo!), typographical emphasis (e.g. capitalization, exclamation marks), visualization of stances (e.g. emojis, smiling faces), and discourse markers that indicate stance-alignment (e.g. ‘yeah’).

For the instances involving attitudes to language(s), I additionally drew on Lee’s (2013: 77–79, 2017: 76–87) and Barton and Lee’s (2013: 115–119) types of metalinguistic discourses on the internet, which they identified based on data from YouTube, Flickr, and online news. These types include asserting native speaker authority; linguistic prescriptivism and purity; multilingualism as added value; engaging in multilingual activity in one language; perceived knowledge of English; apologetic and forgiveness seeking; native speaker norm as a model of “good” English; use of external resources (e.g. Google Translate); self-improvement in the foreign language; self-deprecating humor on one’s language skills; and the resource of photography as the lingua franca. The above types primarily concern discourses about English by non-English users. In the Joulu Kotona dataset, the metalinguistic discourses refer to various languages, including one’s own native language (e.g. Leppäluoto’s self-evaluative comment of Finnish).

3.3 Research ethics

After its streaming, Joulu Kotona was publicly available for rewatching on Leppäluoto’s Facebook page for one week. The ephemeral status of Joulu Kotona’s digital content posed an ethical challenge in terms of reproducing components from it (see Artieri et al. 2021, on ephemeral online data). My first step was to seek permission for using this content from Leppäluoto, since it appeared on (and then disappeared from) his page. I contacted him via email, explaining my research aims. I clarified the data I would utilize and how I would protect the viewers’ privacy. Moreover, I sent him a preliminary draft analysis to give him a clearer picture. Leppäluoto instantly granted permission, stating he was ‘honoured’. The same draft was sent to Kahila upon inviting him for an interview. Regarding Joulu Kotona’s viewers, all chat comments discussed in the analysis were pseudonymized, avoiding references to any personal/sensitive information.

3.4 Joulu Kotona

This section tackles the socio-historical, technical, discursive, linguistic and cultural context of Joulu Kotona. Starting with the socio-historical context, COVID-19 was initially discovered in late-2019 in China, subsequently sparking a global pandemic. To prevent the virus from spreading, many countries implemented strict lockdowns in mid-March 2020. These lockdowns had major repercussions for the economy, culture, education, health, the environment, politics and people’s lifestyle. Specifically, the arts and culture sectors were severely affected as museums, performance venues, and other cultural institutions worldwide cancelled or postponed exhibitions, performances and events. For several services and artists, the digital realm offered a viable alternative. The idea of live streaming Joulu Kotona was not new for Leppäluoto and his bandmates, as they had already successfully streamed a concert on March 27, 2020.

Moving to the technical aspects, Joulu Kotona was livestreamed through Facebook Live, a free feature that allows users to broadcast directly on the platform. Viewers can engage in real-time interactions and watch a recording later. Facebook Live, like most livestreaming services, combines the physical and digital experiences, featuring a unique media convergence: it marries the live video stream with a text-based chat application, enabling synchronous video interaction with real-time commenting on the broadcasted video (Yus 2021: 195).

The streaming of Joulu Kotona took place on 20 December 2020, at 7 pm Eastern European Time, with approximately 2,000–2,100 viewers. The event lasted 1 h and 40 min. Its recorded version was made available on Leppäluoto’s Facebook page for a week. The streaming was free to watch, but viewers could purchase tickets to support the artists. The physical concert occurred at JaBa Studio in Hankasalmi, Finland, and a team from Tuupa Records Oy production handled the video recording.

Figure 1 is a screenshot of Joulu Kotona at the time of its occurrence. As shown, most space is taken up by the artists-streamers: Samuli Erkkilä on the left, JP Leppäluoto in the middle and Elias Kahila on the right. Next to the video display is a text-based chat, to which viewers actively contributed by sending messages to both the artists and other attendees. Next to Kahila (not visible in the image), there was a laptop from which he was reading out the viewers’ messages in-between songs, a practice he had effectively adopted in their March 2020 stream.

Screenshot of the Joulu Kotona concert on Facebook Live.

From a discourse perspective, Joulu Kotona viewers on Facebook Live’s chat engaged in various interactions. They greeted each other and the artists, shared Christmas wishes, discussed their pre-Christmas evening activities, evaluated the songs and the artists’ performance, expressed their feelings for celebrating Christmas on a lockdown, commented on the artists’ appearance (e.g. Leppäluoto’s woollen socks, Kahila’s hat), requested specific carols, and asked Kahila for greetings in different languages. Much of the artists’ spoken discourse relied on audience comments read aloud by Kahila. However, it was not entirely spontaneous. In the interview, Kahila revealed that he had been learning how to say ‘Merry Christmas’ in various languages before the stream. Additionally, Leppäluoto and Erkkilä challenged Kahila to wish in specific languages like Russian, French, and Mandarin Chinese, which he had rehearsed in advance.

Linguistically speaking, the trio are native Finnish speakers with a very good command of English. While Leppäluoto initially sang in English at the start of his career, he transitioned to predominantly Finnish singing in 2009. This shift led many fans, including myself, to start learning Finnish to understand the lyrics. During the Joulu Kotona event, the trio primarily spoke in Finnish, occasionally switching to English. Their spoken discourse was further imbued with Kahila’s multilingual Christmas wishes. In the following interview extract, Kahila sees multiple languages as the glue of communality online, especially during challenging times like the pandemic:

Interview with Kahila (1)

Wishing “Merry Christmas” in different Leppäluoto fans native languages was my slightly odd, humoristic way of recognizing the fans, respectfully spreading positivity and trying to put a smile on their face on these difficult times. Trying to bring people together using music and language.

From a cultural perspective, as already mentioned, Joulu Kotona aimed to celebrate Christmas, a culturally significant time for Finnish people, inextricably linked to carol singing (Hebert et al. 2012). The streaming comments included references, particularly from Finnish viewers, to local Christmas customs such as enjoying ‘glögi’ (mulled wine), ‘piparit’ (gingerbread cookies), chocolate, wearing woolen socks, and lighting candles, all happening simultaneously with the stream. A similar atmosphere was created within the physical studio the trio was performing (see Figure 1). Another cultural issue brought up by Kahila and Leppäluoto during Joulu Kotona relates to the melancholy that characterises Finnish carols (see Section 4.1.1).

4 Multilingual practices in Joulu Kotona

This section proceeds to the analysis proper, which pivots on the translocal multilingual practices of choosing languages and talking about languages during Joulu Kotona as well as on the multilingual promotion of the event.

4.1 Choosing languages during Joulu Kotona

The main findings in this subsection are clustered into (1) the language choices made by the artists, and (2) the language choices made by the audience, including international and Finnish viewers. The focus is on the motivations behind and the functions of the participants’ language choices. In the case of Kahila, I relied on the interview I conducted with him. As for the audience, I drew on the chat data to infer possible motivations.

4.1.1 The artists

During Joulu Kotona, Kahila wished “Merry Christmas” in Finnish, English, Swedish, Spanish, Indonesian, Dutch, Italian, Polish, Mandarin Chinese, French, Russian and Hungarian. Kahila unfolds the motivations behind his language choices below:

Interview with Kahila (2)

Some languages were more randomly chosen, but some were chosen in purpose because of the location of some most intense fans. Spanish I did for the South American fans. There’s one in Argentina that I wanted to surprise. […] I knew a fan from Indonesia that was very active online enjoying Leppäluoto music. And I knew in general that JP had fans in Italy, French and Russia etc. […] Swedish was a natural one to choose. Mandarin Chinese was just a fun, crazy idea to try something that I definitely could NOT pronounce well in a live stream concert hahaha. […] Dutch was chosen because I have special new and old friends there. It used to be that my very best friend was a Dutch woman living near Rotterdam. […] She organized my very first set of solo concerts outside Finland, in Nijmegen Holland, in 2007.

For the choice of Polish, Kahila provides a more elaborate narrative:

Interview with Kahila (3)

Poland owns a special place in my heart […] I have played cello from the age 7 […] and right from the start I had an excellent cello teacher from Poland. She and her family […] moved here in the late 80’s for work. […] So my completely Finnish family and the highly-skilled music professionals, immigrating from Poland […] and their families became friends with us. In the 90’s we invited them to our house to celebrate Finnish Christmas almost every year. Many times they invited my family to their homes on vacations for polish dinners. It was a versatile, interesting surrounding.

As can be deduced, Kahila is mostly socio-culturally driven in his language choices. Languages such as Spanish, Indonesian, Italian, French and Spanish constituted sources for pursuing affinity and communality with Joulu Kotona’s viewers. On the other hand, Kahila’s switching to Dutch and Polish served as a way of paying homage to the cultural and linguistic background of two pivotal figures in his music career: his Polish cello teacher and his Dutch friend who arranged his first concerts in Holland. Swedish was a ‘natural choice’ due to its official status in Finland.[8] Lastly, his use of Mandarin Chinese occurred for aesthetic and bantering reasons (reinforced with the typed laughter ‘haha’).

During the livestream, Kahila and Leppäluoto switched to English as a vehicular language to maximize comprehensibility. Specifically, they chose English to tease each other; dedicate songs to the audience; thank the audience for watching, commenting and buying optional tickets; read unabridged fans’ messages; and respond to English comments. Kahila was the one who favored English with Leppäluoto occasionally switching to align with Kahila’s choice. Commendably, English was chosen as a medium for translating and/or explaining aspects of the local Finnish culture to non-Finnish viewers (cf. Barton and Lee 2013: 46). An illustrative excerpt[9] is given below:

| Artists’ spoken discourse (1) | |

| 1. Kahila: | And I think uh lots of people don’t know but we are playing mostly Finnish songs son- Christmas songs from Finland [so |

| 2. Leppäluoto: | [What do you mean mostly? |

| (0.2) They’re all Finnish. | |

| 3. Kahila: | Oh are they? ((laughing)) They are more melancholic and stuff like that it’s not like a carnival in Finland in Christmas time. It’s more like melancholic kind of stuff ((looking at Leppäluoto)) |

| 4. Leppäluoto: | Yeah (0.2) That’s how it is. |

| 5. Kahila: | Or do you disagree with me? |

| 6. Leppäluoto: | You-you-I love it like this. |

| 7. Kahila: | The Finnish soul is like that but let’s go the next song as requested right now. |

| 8. Leppäluoto: | Tiesitkö Maria. |

| ‘Did you know Maria’. | |

In this interaction, Kahila constructs Finnishness, drawing on an aesthetic and a sociological sense of culture. Sociolinguistically, this is attained by dint of stance-taking in English. His references to music (turn 1) along with the use of the ethnonym ‘Finnish’ (turns 1, 7) and the toponym ‘Finland’ (turns 1, 3) constitute aesthetic cultural elements. We witness that the two artists take stances towards Finnish Christmas songs and Finnish mentality and in doing so, they have a mild disagreement concerning the meaning of ‘Finnish’ (turns 1 and 2). By ‘Finnish songs’, Kahila refers to Christmas songs originally conceived and composed by Finnish musicians and not already existing songs translated into Finnish from other languages; hence, his use of ‘mostly’. In turn 2, Leppäluoto disaligns from Kahila through the emphatically stressed epistemic stance of certainty ‘They’re all Finnish’, denoting that all of the songs comprise lyrics solely in the Finnish language irrespective of the composers’ origin.[10] Sociologically, as relates to mentality and character, Finnishness is identified with melancholy (for melancholy as a key element in Finnish carols, see Hebert et al. 2012: 421–422). In turn 3, Kahila articulates an epistemic stance towards Finnish Christmas songs through the assertion ‘They are more melancholic’, and concomitantly, in turn 7, towards Finnishness (‘is like that’, namely, melancholic) employing the metonymy ‘Finnish soul’. Additionally, in turn 3, Kahila, constructs a relation of distinction (Bucholtz and Hall 2005) between Finland and other countries which celebrate Christmas, indexed via comparison (‘more melancholic’) and juxtaposition (‘not like a carnival’). In this manner, he presents Finnishness as identified with melancholy and therefore timely, universally pertinent, given the time of year. In turns 4 and 6, Leppäluoto shows alignment with Kahila’s construction of Finnishness via the discourse marker ‘yeah’ and the epistemic stance ‘That’s how it is’ (turn 4), as well as by employing an affective stance (with the emotive verb ‘love’ in turn 6). In sum, the artists attained to reconcile locality and globality by (a) singing in Finnish but greeting the audience in other languages; and (b) questioning the Finnishness of the songs and reflecting upon melancholy as a key Finnish element in English.

4.1.2 The audience

In the written comments produced by the audience during Joulu Kotona, several languages were found to co-exist and alternate. The main patterns detected in the international viewers’ discourse concerned the use of: 1) English, 2) Finnish, 3) English and Finnish, 4) their native language, 5) their native language and English, 6) their native language and Finnish, 7) their native language, English and Finnish. By writing back partly or wholly in Finnish as well as drawing on their native languages, they contributed to the reconciling of the local with the global. Concerning Finnish viewers, the most notable patterns had to do with the translocal combination of Finnish with English as well as of Finnish with Swedish.

4.1.2.1 International viewers

English

Many international viewers chose English for formulaic purposes (Androutsopoulos 2013): to convey greetings and share Christmas wishes with fellow participants, often including their city or country of origin in their messages, as illustrated in examples 1–5.

Facebook Live chat (1)

Hello from the Netherlands (Dutch viewer 1)[11]

Facebook Live chat (2)

Saying Hi! from Spain  (Spanish viewer)

(Spanish viewer)

Facebook Live chat (3)

greetings from Athens, Greece (Greek viewer, my comment)

Facebook Live chat (4)

Merry Christmas from Portugal for you all <3  (Portuguese viewer)

(Portuguese viewer)

Facebook Live chat (5)

Merry Christmas from Bolivia  (Bolivian viewer)

(Bolivian viewer)

English was frequently deployed for the evaluation of Finnish Christmas songs and the trio’s performance as is the case in example 6.

Facebook Live chat (6)

Thanks to you guys, this old Christmas song got a new life and I really like this new sound!!! The combination of guitar and cello will make EVERYTHING great! (Ukrainian viewer)

Here the subject matter is the Finnish song “Kellojen joululaulu” (Carol of the bells), based on the Ukrainian folk chant Shchedryk.[12] Although the viewer comments in English, without any traces of neither Finnish nor Ukrainian in her discourse, she attains translocality by engaging in multilingual and multicultural activity in one language (cf. Lee 2017: 85–87).

Finnish

Several international viewers switched to the addressees’ language, namely Finnish, performing what Auer (1988) calls ‘participant-related switching’, to show their respect to and solidarity with the artists, which can be taken as a sign of positive affect (Jaffe 2007) towards them and the event. In examples (7) and (8), the commenters used exclusively Finnish to communicate more evocatively their wishes and evaluations respectively. Notably, the viewer in example (8) adds a heart emoji as an extra proof that what she writes is positively intended, enhancing thus further her feelings. The same effect is observed in example 9 below.

Facebook Live chat (7)

Hyvää Joulua Tsekkista! (Czech viewer)

‘Merry Christmas from the Czech Republic!’

Facebook Live chat (8)

Suomalainen musiikki on täydellinen sielulleni ❤ (Argentinian viewer 1)

‘Finnish music is perfect for my soul’

English and Finnish

The combination of English and Finnish was preferred for varied purposes and effects. In the following examples, the viewers switch to Finnish for the formulaic discourse purpose of thanking (Androutsopoulos 2013: 681). In example 9, the commenter thanks (Kiitos: ‘thank you’) for the carol “Konstan joululaulu”,[13] whereas in examples 10 (kiitos paljon: ‘thank you very much’) and 11 (Kiitos: ‘thank you’), the commenters thank the artists for the stream in its entirety. In example 10, we witness two parallel textual units, namely units where the one literally translates the other in a different language (Sebba 2012): thank you so much - kiitos paljon. As this comment was produced by me, my parallelism here was intended for a collective multilingual reading by the artists and other audience (Finnish and non-Finnish) members alike. Such a practice can be seen as a booster of positive affect akin to that found in examples 8 and 9.

Facebook Live chat (9)

An already amazingly beautiful song + that sound… Kiitos, it’s been so touching ❤ (Spanish viewer)

Facebook Live chat (10)

wonderful live!thank you so much - kiitos paljon! (Greek viewer, my comment)

Facebook Live chat (11)

Kiitos guys! A beautiful evening with you!! Merry Christmas!!  (Italian viewer)

(Italian viewer)

While Kahila sociolinguistically constructed Finnishness in English, the audience did so by interspersing their English comments with specific Finnish items, which feature aesthetic as well as sociological dimensions of the Finnish culture. In this vein, the viewers appeared to be familiar with the Finnish context. Consider the following examples:

Facebook Live chat (12)

Hugs from Moscow! No Vanajan kirkko this year, but thank you for the stream! You saved the Christmas  (Russian viewer 1)

(Russian viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (13)

I always like Tonttu when JP sings this at Raskasta Joulua. (Latvian viewer)

Facebook Live chat (14)

Is JP a tonttu? (American viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (15)

one of the fave joululaulu

one of the fave joululaulu  (Russian viewer 2)

(Russian viewer 2)

Facebook Live chat (16)

Villasukat rulez! (Hungarian viewer)

In example 12, the aesthetic sense of Finnishness in indexed with the toponym ‘Vanajan kirkko’ (a church in Hämeenlinna, Finland), where the trio had performed a –pre-pandemic– Christmas concert in 2019, probably attended by the viewer. Other significant aesthetic cultural elements are encountered in example 13, with the reference to the Finnish Christmas song Tonttu (The Elf) and the Finnish Christmas music event Raskasta Joulua (Heavy Christmas).[14] In example 14, through an intertextual linkage to Tonttu, the viewer employs positive affective stance-taking by likening Leppäluoto to an elf, attaching him the connotations of mystery and magic. The audience also constructs Finnishness sociologically by mentioning the Finnish cultural practices and customs of enjoying ‘joululaulu’ (Christmas song) in example 15 and wearing ‘villasukat’ (woolen socks) in example 16, with particular reference to the socks that Leppäluoto was wearing during the stream.

Native language

Several members of the audience selected their native language to greet as well as to indicate how they wish ‘Merry Christmas’. Two concrete examples are provided below:

Facebook Live chat (17)

Saludos desde Santiago de Chile!!! (Chilean viewer)

‘Greetings from Santiago in Chile!!!’ (original in Spanish)

Facebook Live chat (18)

Buon Natale!!! (Italian viewer 2)

(Italian viewer 2)

‘Merry Christmas’ (original in Italian)

Native language and English

Native languages were witnessed to co-exist with English for the expression of Christmas wishes. For instance, Merry Christmas is expressed in Swedish (God Jul) in example 19; in Indonesian (SELAMAT NATAL) in 20; in French (Joyeux Noel) in 21; in Polish (Dziękuję bardzo) in 22 and in Portuguese (Feliz Natal) in 23. In this fashion, the viewers, on the one hand, bestowed a more local flavour to their comments. On the other hand, this choice can be seen as a positive affective stance-follow to Kahila’s wishing in different languages (mostly evident in examples 19 and 20). Notably in 20, the viewer promptly reciprocates Kahila’s Indonesian greeting by expressing her wishes in the same language, transliterating it in the Roman alphabet to facilitate comprehension.

Facebook Live chat (19)

Thank you so much for this livestream! <3 Merry Christmas guys! And to “the cello guy”…God Jul!;-) (Swedish viewer)

Facebook Live chat (20)

SELAMAT NATAL TOO ELIASSSSS (Indonesian viewer)

Facebook Live chat (21)

Thank you for making this Christmas wonderful, despite everything. Merry Christmas and Joyeux Noel (Canadian viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (22)

Thank you for magical performance  Your music touched my heart

Your music touched my heart  Dziękuję bardzo

Dziękuję bardzo  (Polish viewer 1)

(Polish viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (23)

Thank you so much for this beautiful concert, Feliz Natal <3 (Portuguese viewer)

Native language and Finnish

In example 24, along with her native language, Spanish, used for the immediate expression of a positive affective stance (‘Dios mío!! gracias!’), the viewer chooses Finnish as an addressivity strategy (Seargeant et al. 2012) to index Leppäluoto. The use of ‘Jussi,’ a diminutive of Juha-Pekka (Leppäluoto’s first name), not only expresses her affection for the artist but also demonstrates her familiarity with Finnish ways of showing endearment and affection.

Facebook Live chat (24)

Dios mío!!! gracias! Konstan joululaulu! Minä itken. Se koskettaa sydäntäni, rakas Jussi

gracias! Konstan joululaulu! Minä itken. Se koskettaa sydäntäni, rakas Jussi  (Argentinian viewer 1)

(Argentinian viewer 1)

‘My God!!! thank you!’ (in Spanish) ‘I’m crying. It touches my heart, dear Jussi’ (in Finnish)

Native language, English and Finnish

In example 25, the viewer adopts the addressivity strategy of providing a trilingual comment in Finnish, English, and her native Spanish, to reach and include as many audience members as possible. Similarly, in example 26, three languages are employed: Finnish, English, and the viewer’s native Polish. By referencing the Finnish song title (Tiesitko Maria) and explaining in English that there is a Polish version of the same carol, albeit without any traces of Polish, the viewer, akin to example 6, promotes a translocal practice.

Facebook Live chat (25)

Hyvää Joulua kaikille, Merry Xmas everyone, Feliz Navidad!  (Argentinian viewer 2)

(Argentinian viewer 2)

Facebook Live chat (26)

Tiesitko Maria sounds great in Finnish! We also have a very melancholic version of this Carol in Polish! Greetings from Poland! (Polish viewer 2)

4.1.2.2 Finnish viewers

English

Apart from using their native language, Finnish viewers chose English with a view to rendering a more inclusive and international discourse that would embrace all event participants. This is exemplified in 27.

Facebook Live chat (27)

Merry christmas to everyone joining this stream and keep on rockin’ 2021. (Finnish viewer 1)

Finnish and English

Finnish viewers also combined Finnish with English, as seen in example 28. This is a case of parallel bilingual writing where the English text is a word for word translation from the Finnish one. The viewer states that she comes from Raahe, a coastal town in western Finland. This is crucial since Raahe is Leppäluoto’s hometown, something that most –if not all– of his fans are aware of. By constructing Raahe translocally through a positive affective stance in both languages (idyllisestä – idyllic), the viewer appears to be proud for coming from the same place as Leppäluoto. To ensure this vital piece of information is not missed, she renders her message in English as well, giving thus the international audience members a choice of language (Sebba 2012) in case they do not comprehend Finnish.

Facebook Live chat (28)

Hyvää joulua kaikille idyllisestä Raahesta. ❤Merry Christmas to all from the idyllic Raahe!  (Finnish viewer 2)

(Finnish viewer 2)

Finnish and Swedish

A few Finnish viewers living in Sweden mixed Swedish with Finnish in their comments, conveying a dual sense of place identity, as shown in example (29).

Facebook Live chat (29)

God jul Uppsalasta! <3 (Finnish viewer 3)

‘Merry Christmas (in Swedish) from Uppsala (in Finnish)!’

As shown in this section, the members of the audience sought to attain communality and identification with other viewers and with the artists by selecting and alternating between languages in manifold ways: using English as a lingua franca, employing Finnish to serve symbolic functions, mixing English and Finnish, combining English with their native languages to give a local flavor, and drawing on their native languages only. Through their digitally mediated multilingual practices, the viewers formed a translocal community. On the one hand, they indicated, to borrow Kytölä’s (2016: 382) phrasing, ‘strong orientations to the globally occurring and globally meaningful aspects’ of celebrating Christmas and singing carols. On the other hand, they appropriated these global aspects into locally significant experiences (Christmas in Finland, Finnish carols, carols in other cultures and languages). More specifically, in English, they identified themselves as not English (but Finnish, Dutch, Spanish, Polish and so on) indicating at the same time their place of origin. In Finnish, non-Finnish viewers performed Finnishness showing their respect to the artists and Finnish Christmas music as well as their familiarization with the Finnish cultural context, flagging simultaneously their origin (e.g. Argentinian). Moreover, the use of phatic expressions in Finnish (where, for example, a single ‘thank you’ phrase in English would have been adequate) indicates that these viewers devoted an extra effort to orient to the musicians and Finnish members of the audience. Lastly, there were viewers who used parallel textual units in two or three languages within the same message to attain translocal connection, making, in this manner, music and Christmas celebration points of identification for all Joulu Kotona participants.

4.2 Talking about languages during Joulu Kotona

In what follows, I present different types of metalinguistic discourses identified in Joulu Kotona, including validating speaker’s authenticity; differentiating languages; juxtaposing with native Finnish norms; apologizing and seeking forgiveness for errors; utilizing external resources for multilingual practices; and identifying music as the lingua franca.

4.2.1 Validating speaker’s authenticity

Kahila acknowledged in the interview that he did not intend to present himself as an authentic speaker of the multiple languages he deployed. Yet, the viewers authenticated him through positive assessments, confirming Androutsopoulos (2015a) in that the negotiation of authenticity in social media spaces is principally a matter of audience reception. As shown in the examples below, produced as soon as Kahila was wishing in a given language, these assessments are realized with adverbs (‘well’ in 30, ‘great’ and ‘very well’ in 31, ‘NICEEEEE’ in 34), adjectives (‘good’ in 36, ‘that good’ in 37), approval interjection (‘Bravo!’ in 32), and value-laden vocabulary (‘nut case’ in 33). In example 35, the viewer’s stance is indexed with the choice of Finnish while in example 37 the viewer employs Russian as a way of linguistic mirroring to Kahila’s wish in Russian to calibrate alignment between the two parties. The audience also accompanied their stances with exclamation marks (examples 32, 34 and 36), capitalization (example 34), emoji (heart in 31) and emoticons (heart in 32 and smiling faces in 37) that further reinforce the favorable attitude.

Facebook Live chat (30)

Yes, you speak well in Dutch, thank you (Dutch viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (31)

Great  You said it very well in Polish (Polish viewer 1)

You said it very well in Polish (Polish viewer 1)

Facebook Live chat (32)

Bravo! Wesołych świąt <3 (Polish viewer 3)

‘Bravo! Merry Christmas’ (Polish in the original)

Facebook Live chat (33)

Elias a little nut case of Merry xmas (Finnish viewer 4)

Facebook Live chat (34)

NICEEEEE, Elias !!!!!!!!!!! (Russian viewer 2)

Facebook Live chat (35)

Venäjä kanssasi) (Russian viewer 3)

‘Russia is with you’

Facebook Live chat (36)

Elias you have a good russian!!! (Russian viewer 4)

Facebook Live chat (37)

Since you’re that good in languages, there’s one for you to read:) Mi vas lubim, bud’te zdorovi!In Russian it means - “we love you, be well”:) (Russian viewer 5)

4.2.2 Differentiating languages

In excerpt 2, the artists reflect upon other languages having their native Finnish as a yardstick. In turn 1, Kahila constructs a relation of distinction (Bucholtz and Hall 2005) between Finnish, Dutch and Polish, implicitly considering the latter two more challenging than Finnish. The differentiation of Polish is foregrounded with affective stance markers: the adjective ‘difficult’ intensified with ‘very’, the exclamation of surprise ‘oh my God’, the phrase ‘speaking differently’ intensified with ‘years of’ and emphasized with his gesture of touching his neck/vocal cords. Leppäluoto, on the other hand, in turn 2, draws a relation of similarity (Bucholtz and Hall 2005) between Polish and Finnish, by means of epistemic (‘I think’) and affective stances (‘the same’, ‘it ain’t easy either’). Notably, in turn 4, Leppäluoto expresses a lay linguistic attitude echoing Chomsky (1986) on our inborn capacity for language acquisition. In turn 5, Kahila hastily shows alignment with Leppäluoto on the difficulty of Finnish (‘Yeah …as well’) to proceed to wishing in Polish.

| Artists’ spoken discourse (2) | |

| 1. Kahila: | Merry Christmas in Polish is very difficult. You know (.) I thought Holland ((he means Dutch)) was difficult but (.) oh my God (.) Merry Christmas in Polish language (0.1) needs years of (.) u:h you know (.) just ((approaches his hand to his neck)) speaking differently (.) but I can give it a shot if you want. |

| 2. Leppäluoto: | I think they- (.) I think the same about Finnish language (0.1) It ain’t easy either. |

| 3. Kahila: | But OK [Merry Christmas |

| 4. Leppäluoto: | [We’re planned (.) we’re born with it. |

| 5. Kahila: | Yeah yeah it’s (.) Finnish is very difficult as well but let-let’s (.) I wanna (.) get this done and away with it. OK (.) Merry Christmas in Polish for all you Polish people there (.) Poland u:h (.) Wesołych Świąt! ((he waves smiling as soon as he says the wish in Polish)) |

4.2.3 Juxtaposing with native Finnish norms

The comments below center upon spoken Finnish and, more specifically, on the pronunciation of the Finnish rolling “r,” which poses a challenge for foreign learners of Finnish. Unlike English and other languages, the Finnish “r” sound is always pronounced with the tip of the tongue trilled. The viewer in comment 38 expresses her admiration for Leppäluoto’s pronunciation via the affective verb ‘love’. In example 39, the viewer juxtaposes herself with the specific native speaker norm, expressing a negative attitude towards her pronunciation (‘I can’t’, ‘plays dead’) whereas in example 40, the viewer wishes she could sound more authentic while speaking Finnish.

Facebook Live chat (38)

i love how he rolls the R (German viewer)

Facebook Live chat (39)

I can’t roll my “r” like that. It rolls over and plays dead (American viewer 2)

Facebook Live chat (40)

I wish I could roll my R like that.  (Canadian viewer 2)

(Canadian viewer 2)

4.2.4 Apologizing and seeking forgiveness for errors

This type of comments comprises cases of self-deprecating metalanguage, where individuals downplay their own language abilities, often to negotiate their belonging to a particular community (Barton and Lee 2013: 114). Such metalanguage came principally from Kahila who asked the audience to forgive any possible pronunciation errors of his while wishing in different languages (‘I’m sorry I can’t speak better’ in excerpt 3, ‘my apologies to the people of (.) Budapest and other places’ in excerpt 4). In excerpt 4, Kahila adds a touch of humor based on the near homophony of ‘boldog’ (‘merry’ in Hungarian) and ‘bulldog’ (a dog breed), which helped him remember the correct pronunciation in Hungarian. Hence, he seeks for forgiveness in case his pronunciation was closer to ‘bulldog’.

| Artists’ spoken discourse (3) | |

| Kahila: | [name of fan] from Poland says kiitos from Poland. So I think (0.2) I was not able to piss off all the Polish people and I’m very thankful for this. And I- I’m sorry I can’t speak better. I’m- I’m just a (.) cello guy ((all three artists laugh)) |

| Artists’ spoken discourse (4) | |

| Kahila: | That’s Merry Christmas in Russian (.) and Hungary is my favourite (.) Boldog Karácsonyt ((Merry Christmas in Hungarian)) ((Erkkila repeats it in the background)) It’s really boldog but it’s easier (.) to remember (.) bulldog. ((Erkkila laughs)) So (.) my apologies to the people of (.) Budapest and other places. |

4.2.5 Utilizing external resources for multilingual practices

In these metalinguistic comments, the artists and the viewers explain what supported their multilingual speaking/writing. As Kahila conceded in the interview, he had to prepare himself in advance for his multilingual wishing utilizing Google Translate’s audio-voice feature:

Interview with Kahila (4)

I used the computer-generated female voice on the Google Translator to listen to the correct pronunciation of different languages. This is how it happened with all new languages. I’d first put the English word “Merry Christmas” in and then translate the phrase in another language. I listened to the computer-generated audio voice because I knew I could get much closer to the way “Merry Christmas” should be said in different languages. Maybe a musician’s ear helped me there a little, but it was difficult to adapt to different languages. I was re-playing that female voice a lot! Although my goal was not to be great in this, but more to entertain people and have some fun. I wouldn’t mind people laughing at my pronunciation haha. I remember I did these tasks with my headphones on, on the train from Jyväskylä to Tampere and back, first choosing a quiet place with no other people around haha.

Kahila outlines his precise literacy practices for learning the wishes: 1) inserting ‘Merry Christmas’ into Google Translate; 2) translating it into the desired language; 3) listening to Google Translate’s audio voice using headphones; 4) repeatedly playing the audio voice; and 5) practicing the translated phrase aloud (not explicitly stated, but inferred from his choice to practice in a quiet train compartment). Kahila here substantiates Lee’s (2017: 113) argument that online translation tools serve not only to understand word meanings but also to accomplish specific goals – in his case, entertaining an international audience and having fun.

Google Translate was also used by some international viewers who wished to participate in the chat writing in Finnish and therefore position themselves within the broader translocal context of the event. This is featured in example 41 where the viewer acknowledges the potential inaccuracies yielding from Google Translate.

Facebook Live chat (41)

Apeldoorn, Hollanti. Hyvää Joulua teille kaikille. (Errors courtesy of google translate) (Dutch viewer 2)

‘Apeldoorn, Holland. Merry Christmas to you all.’ (in Finnish)

4.2.6 Identifying music as the lingua franca

Akin to Barton and Lee’s (2013) findings on the role of photography as a lingua franca on Flickr, a few Joulu Kotona chat comments, as shown below, dealt with the secondary role of (Finnish) language to Christmas songs, recognizing the vital role of music in invoking sentiments and uniting people.

Facebook Live chat (42)

Truly music has its own language. I don’t understand what the songs say but you already have my eyes watery. (Spanish viewer)

Facebook Live chat (43)

I don’t understand a word but I don’t really need one to enjoy good music. greetings from Romania (Romanian viewer)

Facebook Live chat (44)

Näen suomen kielen oppimisen tulokset! Ymmärrän puolet sanoista, mutta koko musiikin, koska se on kansainvälistä (Argentinian viewer 1)

‘I can see the results of learning the Finnish language! I understand half the words but all the music because it’s international’

The viewers above convey epistemic stances realized via the cognitive verb ‘understand’ in English and Finnish, accompanying them with affective stance tokens related to the music (‘truly’, ‘good’) and their feelings (‘watery’, ‘enjoy’). What is more, the viewer in example 44 acknowledges that listening to Finnish songs has assisted her in improving her learning of Finnish.

Overall, the metalinguistic discourses spotted in Joulu Kotona serve the main social function of encouraging and widening participation in the multicultural and multilingual world of social media (see also Barton and Lee 2013; Lee 2013, 2017). Talking about their skills in different languages (e.g. Kahila for his Polish, international viewers for their Finnish) enabled the geographically dispersed Joulu Kotona participants to establish rapport; to build a supportive environment where they could develop their multilingual practices; and, by and large, to position themselves as active members within the broader translocal context of Joulu Kotona and the global world of Facebook. By arguing about how difficult it is to speak another language (discourse of differentiating languages), by apologizing for his pronunciation (discourse of apologizing and seeking forgiveness for errors), and by explaining in detail how he used Google Translate to practice his multilingual Christmas wishing (discourse of utilizing external resources for multilingual practices), Kahila appears to have put in considerable effort to perform in the different languages he used during the livestream with a view to reaching a larger and more global audience. That effort of his was strongly applauded by the audience (discourse of validating speaker’s authenticity). To non-Finnish viewers, degrading their proficiency in Finnish (discourse of juxtaposing with native Finnish norms) enables them to create a friendly and supportive space (see also Barton and Lee 2013) where they can share their language learning experiences in a humorous way. Moreover, the very act of talking about their attempt to perform in Finnish indicates their willingness to immerse in the Finnish context. Lastly, with the discourse of identifying music as the lingua franca, the viewers across different places manifest translocality by attaching emotional significance to the cultural product of Finnish carols.

4.3 The multilingual promotion of Joulu Kotona

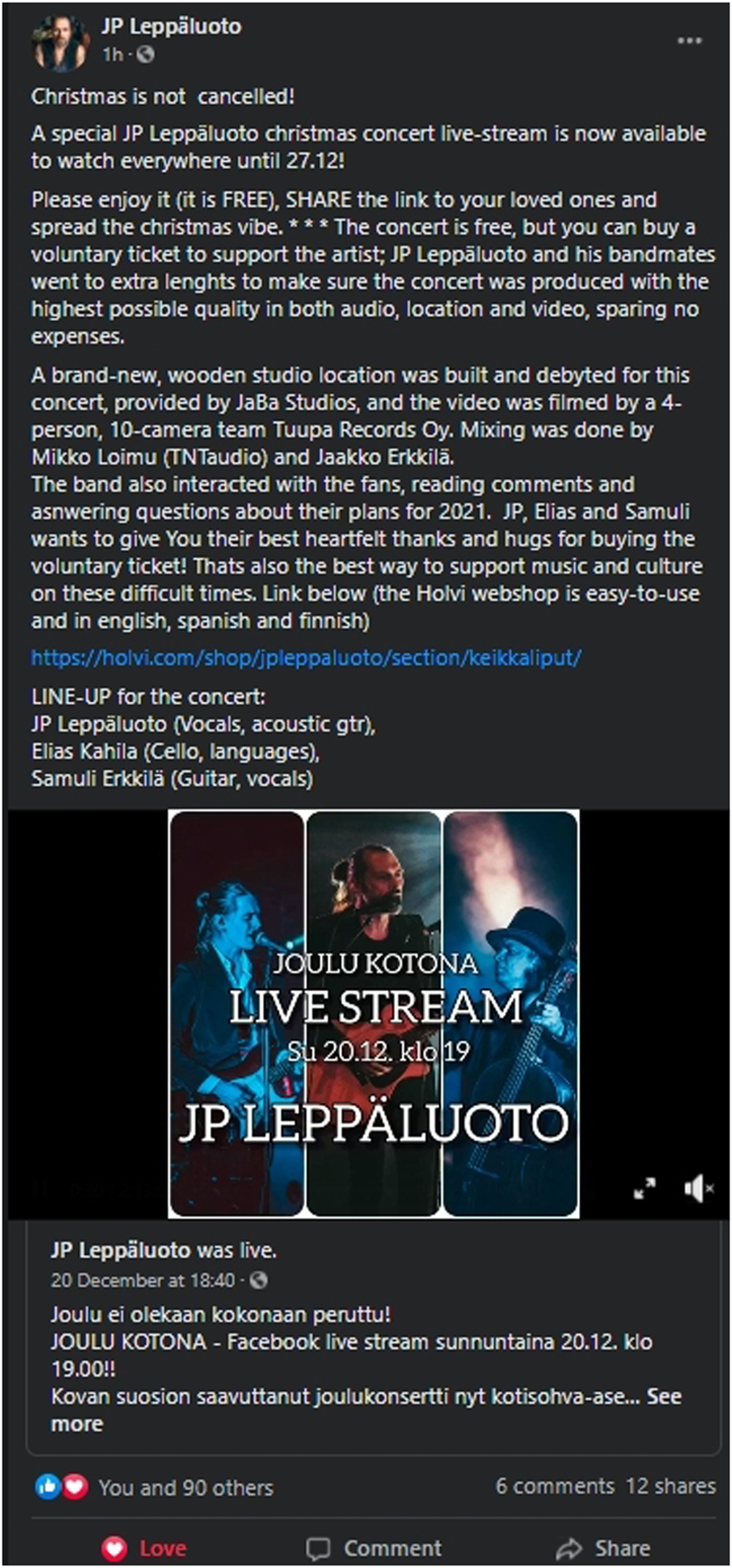

As indicated previously, after its streaming, the video of the event and the comments were available for one week on Leppäluoto’s Facebook page. The artist promoted anew the event in subsequent Facebook posts during that week for the fans who had not been able to watch it live and/or wished to buy an optional ticket to support the trio as well as the fans who wanted to rewatch it. The multilingual character that the event acquired, both in-between the songs performance and in the chat comments, shaped the way in which Joulu Kotona was promoted in these after-event Facebook posts. Figure 2 depicts the advertisement of the event before its occurrence: the language of the post is Finnish and Kahila is presented as a cellist solely. In this fashion, the local relevance of Joulu Kotona becomes prominent. Figure 3 shows Joulu Kotona’s later recontextualization: the post prioritizes English, to address international fans as well as to provide them with much more information about the event, in comparison with the original Finnish advertisement, while Kahila appears skillful in cello as well as in languages. This recontextualization contributes to the artists’ transnational and translocal connection with their local and global audience.

Promotion of Joulu Kotona before its streaming on Leppäluoto’s Facebook page.

Promotion of Joulu Kotona after its streaming on Leppäluoto’s Facebook page.

5 Concluding remarks

Employing tools from discourse-centred online ethnography and analytic autoethnography, the present study set out to explore translocality in Joulu Kotona, a Finnish Christmas concert which was livestreamed via Facebook Live during the COVID-19 lockdown in December 2020. As shown, the artists and the audience together co-constructed the translocal qualities of the event and the Finnish Christmas carol tradition through their multilingual practices. These included language choice, code-switching and stances towards languages as detected in the artists’ spoken discourse (during the event and in the interview with Kahila) and the audience’s written comments in the chat.

The analysis is consistent with Leppänen and Peuronen’s observations (2012), indicating that Kahila’s and the viewers’ language choices were resources for the creation of stylistic and cultural effects, as well as for identity and community negotiation at a translocal level. By using an arsenal of selected languages, Kahila constructed his identity as an artist who shows respect to his artistic heritage as well as connectivity with the local and global fans, revealing his intention to entertain them, to provide solace during the pandemic, and to enhance and diversify the Christmas atmosphere. Interestingly, as discussed in 4.2.1, Kahila’s identity was validated by the viewers’ positive affective stance-taking on his facility for different languages. Beyond his individual identity, Kahila, together with Leppäluoto, constructed a collective Finnish identity. By choosing English as a lingua franca, they explained and clarified facets of the Finnish culture (i.e. melancholy) to the world that might not have been that translucid to all international viewers. This finding accords with Barton and Lee (2013) who have pointed out the use of English as a medium for explaining the Chinese culture to non-Chinese users of Flickr. By providing these English explanations, the artists also distinguished Finland’s Christmas traditions from those of other countries.

With respect to the audience and their multilingual practices, the analysis identified intertwined layers of desired connectivity with other viewers and with the artists. A notable finding concerns the sociolinguistic construction of Finnishness, with non-Finnish viewers using Finnish while Kahila preferred to do so in English. This can be attributed to different motivations: Kahila aimed to elucidate aspects of Finnish culture to the world, whereas the fans sought to express and manifest their appreciation of Finland and Finnish music by demonstrating their (attempted/ritual) knowledge of Finnish. Simultaneously, the viewers projected their local identities through their native languages. This use served as a semiotic strategy (Leppänen and Peuronen 2012), allowing the participants to differentiate themselves and assert their unique voices, maintaining thus their existing identities, within the translocal environment of Joulu Kotona.

As for Joulu Kotona’s metalinguistic discourses, the examples discussed evinced, akin to Drasovean and Tagg’s (2015) research, that the participants’ talk about languages functioned as a community-building resource, enabling them to interact digitally across and between locales and cluster around shared views and emotional attitudes around languages and their speakers as well as cultural practices.

In summary, the multilingual practices adopted by Joulu Kotona participants showcased the translocal nature of digital communication enabled through the affordances of Facebook Live; the translocality of the Finnish culture and other cultures; the translocality of Finnish Christmas carols as a cultural product; the translocality of the Christmas, in general, and the Christmas-at-home, in particular, experience, in light of the pandemic.

Considering the ethnographically informed approach in this study, some important observations emerge. Firstly, it allowed one of the core participants, Kahila, to reflect on his language choices and practices during Joulu Kotona and beyond. As he stated after our interview:

Interview with Kahila (5)

I am sorry If my answers were too long. I didn’t think I was gonna write this long, but some new things kept popping in my head, I guess I learned something of myself here too.

Second, conducting and sharing this research can be seen as a way of giving back to the Leppäluoto and Finnish Christmas songs fan community, opening up a channel for further bonding (see also Lee 2021). Lastly, the selected approach contributes to the historicization of Joulu Kotona as well as of COVID-19, more broadly. Recent scholarship (e.g. Damiens 2023) underlines the critical need to archive how cultural actors, be that musicians, filmmakers, curators, and audiences, responded to the COVID-19 crisis. Further research in this direction is required to explore how discourse practices, including multilingual ones, are reconfigured when cultural events no longer adhere to traditional physical mobility, interaction, and socialization patterns (Georgakopoulou and Bolander 2022: 13).

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Elias Kahila and JP Leppäluoto for inspiring this study and giving me permission to conduct it. My gratitude also goes to Jürgen Jaspers and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions that significantly improved this paper. I also thank Hanna Männikkölahti for editing the abstract in Finnish. The publication of the paper in open access mode was financially supported by HEAL-Link.

References

Adaskou, Karima, David Britten & Bouazza Fahsi. 1990. Design decisions on the cultural content of a secondary English course for Morocco. ELT Journal 44(1). 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/44.1.3.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, Leon. 2006. Analytical autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4). 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2007. Language choice and code-switching in German-based diasporic web forums. In Brenda Danet & Susan C. Herring (eds.), The multilingual internet, 340–361. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2008. Potentials and limitations of discourse-centred online ethnography. Language@Internet 5. https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2008/1610.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2013. Code-switching in computer-mediated communication. In Susan C. Herring, Dieter Stein & Tuija Virtanen (eds.), Pragmatics of computer-mediated communication, 667–694. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter Mouton.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2015a. Negotiating authenticities in mediatized times. Discourse, Context & Media 8. 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2015b. Networked multilingualism: Some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism 19(2). 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006913489198.Search in Google Scholar

Artieri, Giovanni Boccia, Stefano Brilli & Elisabetta Zurovac. 2021. Below the radar: Private groups, locked platforms, and ephemeral content. Social Media + Society 7(1).Search in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter. 1988. A conversation analytic approach to code-switching and transfer. In Monica Heller (ed.), Code-switching: Anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives, 187–213. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Barton, David & Carmen Lee. 2013. Language online: Investigating digital texts and practices. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Barton, David & Carmen Lee. 2017. Methodologies for researching multilingual online texts and practices. In Marilyn Martin Jones & Deirdre Martin (eds.), Researching multilingualism: Critical and ethnographic perspectives, 141–154. Abingdon: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Baym, Nancy K. 2018. Playing to the crowd: Musicians, audiences, and the intimate work of connection. New York: New York University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The sociolinguistics of globalization, 81–96. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bucholtz, Mary & Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies 7(4-5). 584–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use. New York: Praeger.Search in Google Scholar

Damiens, Antoine. 2023. Festivals, Covid-19, and the crisis of archiving. In Marijke de Valck & Antoine Damiens (eds.), Rethinking film festivals in the pandemic era and after. Framing film festivals, 291–305. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Drasovean, Anda & Caroline Tagg. 2015. Evaluative language and its solidarity-building role on TED.com: An appraisal and corpus analysis. Language@Internet 12. article 1.Search in Google Scholar

Du Bois, John W. 2007. The stance triangle. In Robert Englebretson (ed.), Stancetaking in discourse: Subjectivity, evaluation, interaction, 139–182. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Georgakopoulou, Alexandra & Brook Bolander. 2022. ‘New normal’, new media. Covid issues, challenges & implications for a sociolinguistics of the digital. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, Paper 296. 1–19.Search in Google Scholar

Hebert, David, Alexis Anja Kallio & Albi Odendaal. 2012. Not so silent night: Tradition, transformation and cultural understandings of Christmas music events in Helsinki, Finland. Ethnomusicology Forum 21(3). 402–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2012.721525.Search in Google Scholar

Jaffe, Alexandra. 2007. Codeswitching and stance: Issues in interpretation. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 6(1). 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348450701341006.Search in Google Scholar

Jaffe, Alexandra. 2009. Introduction: The sociolinguistics of stance. In Alexandra M. Jaffe (ed.), Stance: Sociolinguistic perspectives, 3–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jenkins, Henry. 1992. Textual poachers: Television fans & participatory culture. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Kytölä, Samu. 2014a. Negotiating multilingual discourse in a Finland-based online football forum: Metapragmatic reflexivity on intelligibility, expertise and ‘nativeness’. In Janus Spindler Møller & Lian Malai Madsen. In Globalisering, sprogning og normativitet: Online og offline, Vol. 70, 81–122. Copenhagen: Københavns Universitet. The Copenhagen Studies in Bilingualism.Search in Google Scholar

Kytölä, Samu 2014b. Polylingual language use, framing and entextualization in digital discourse: Pseudonyms and ‘signatures’ on two Finnish online football forums. In Jukka Tyrkkö & Sirpa Leppänen (eds.), Texts and Discourses of new media (Studies in variation, contacts and change in English 15), Helsinki: VARIENG.Search in Google Scholar

Kytölä, Samu. 2016. Translocality. In Alexandra Georgakopoulou & Tereza Spilioti (eds.), Handbook of language and digital communication, 371–388. Abingdon: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Kytölä, Samu. 2023. Metapragmatics of “bad” English in Finnish social media. In Elizabeth Peterson & Kristy Beers Fägersten (eds.), English in the Nordic countries: Connections, tensions, and everyday realities, 185–203. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Carmen. 2013. ‘My English is so poor…so I take photos’. Meta-linguistic discourses about English on Flickr. In Deborah Tannen & Anna Marie Trester (eds.), Discourse 2.0: Language and new media, 73–83. Washington: Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Carmen. 2017. Multilingualism online. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Katja. 2021. Acafan methodologies and giving back to the fan community. Transformative Works and Cultures 36. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.2025.Search in Google Scholar

Leppänen, Sirpa & Saija Peuronen. 2012. Multilingualism on the internet. In Marilyn Martin-Jones, Andrian Blackledge & Angela Creese (eds.), Handbook of multilingualism, 384–402. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Leppänen, Sirpa, Anne Pitkänen-Huhta, Arja Piirainen-Marsh, Tarja Nikula & Saija Peuronen. 2009. Young people’s translocal new media uses: A multiperspective analysis of language choice and heteroglossia. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14(4). 1080–1107.Search in Google Scholar

Leppänen, Sirpa & Shaila Sultana. 2023. Digital multilingualism. In Carolyn McKinney, Pinky Makoe & Virginia Zavala (eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Daniel. 2017. Christmas: An anthropological lens. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7(3). 409–442. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau7.3.027.Search in Google Scholar

Nederveen Pieterse, Jan. 1995. Globalization as hybridization. In Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash & Roland Robertson (eds.), Global modernities, 45–69. London: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Rymes, Betsy & Andrea Leone. 2014. Citizen sociolinguistics: A new media methodology for understanding language and social life. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics 29(2). 25–44.Search in Google Scholar

Salo, Olli-Pekka. 2012. Finland’s official bilingualism: A bed of roses or of procrustes? In Jan Blommaert, Sirpa Leppänen, Päivi Pahta & Tiina Räisänen (eds.), Dangerous multilingualism: Northern perspectives on order, purity and normality, 25–40. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Seargeant, Philip, Caroline Tagg & Wipapan Ngampramuan. 2012. Language choice and addressivity strategies in Thai-English social network interactions. Journal of Sociolinguistics 16(4). 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2012.00540.x.Search in Google Scholar

Sebba, Mark. 2012. Researching and theorising multilingual texts. In Mark Sebba, Shahrzad Mahootian & Carla Jonsson (eds.), Language mixing and code-switching in writing: Approaches to mixed-language written discourse, 1–26. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar