Abstract

During the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, professors at a university in Canada were invited to fill-out a questionnaire inquiring about the role of body language in their lectures. Participants were asked to view body language in its largest sense, from facial expressions to hand gestures, eye movements, postures. The aim of this study was to investigate the way professors of different disciplines who were not used to classes held online perceived their body language to contribute to their teaching in the promotion of students’ learning at a moment in time when they could better relate to the differences between teaching in two class formats. This article examines the responses that 58 professors offered to the questionnaire, where the most important finding not only indicates that professors perceived their body language to make a salient contribution to their teaching, but also that this was the case especially during in-person classes.

1 Introduction

The aim of this article is to provide insights into professors’ perception of their body language and the way it contributes to teaching and to students’ learning (cf. Alibali et al. 2013; Küçük 2023; Maulana et al. 2023; Nathan et al. 2019; Stolz 2021), when class venue changes. A research study inspired by the literature in first and second language acquisition (e.g., Goldin-Meadow and Alibali 2013; Macedonia and Knösche 2011; Sime 2008; Stam and Urbanski 2023), as well as by the latest research on multimodality that encourages the use of the body for pedagogical purposes (cf. Azaoui 2019; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Farran and Morett 2024; Lim 2021; Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023; Mejía-Laguna 2023), was organized to inquire about whether professors of different disciplines who were not used to classes held online believed that their body language changes with teaching venue. In consideration of the expansion of online classes in today’s education and the fact that different class venues demand an adjustment of one’s verbal and nonverbal behaviours (e.g., Paradisi et al. 2021; Querol-Julián 2021, 2023; Satar 2015), this study investigated professors’ body language affordances and limitations, delineating some salient characteristics between lectures held in-person vs. online.

2 Literature review

Multimodality, that is the use of different modes such as movement, colours, images, tools, etc. to create and understand meaning in communication, has been found to facilitate comprehension between interlocutors, including between instructors and students (cf. Azaoui 2019; Belhiah 2013; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Campisi and Özyürek 2013; Dahl and Ludvigsen 2014; Farran and Morett 2024; Lim 2021; Mejía-Laguna 2023; Sime 2008). One of the modes typically considered to form part of the concept of multimodality is body language. In recent years, there has been a renewed attention to body language as different scholars have been interested in examining the way it constructs meaning and helps with the interpretation of contents expressed in words (cf. Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023). Moreover, scholars are increasingly interested in exploring instructors’ perception and awareness of the nonverbal characteristics that contribute to effective teaching in order to promote multimodal literacy (cf. Alibali et al. 2013; Küçük 2023; Morell 2020; Nathan et al. 2019; Salvato 2020) and prepare instructors for different teaching venues, their affordances and limitations (e.g., Querol-Julián 2021, 2023).

Because of their visual and motoric nature, body movements among which hand gestures, facial expressions, gaze, and postures, allow speakers to convey information holistically, spatially, and simultaneously (Bavelas and Chovil 2018; McNeill 1992; McNeill et al. 2015; Mehrabian 1969; Patterson et al. 2023). Concepts such as location, direction, shape, manner of an action, but also numbers, plurality, time, are particularly well-suited to be communicated via body movements (Kendon 2004, 2017): the specification of the size of an object through arm and hand gestures; the reproduction of the manner of an action, such as “running” as opposed to “walking”; showing the left side instead of the right side; identifying people, places or objects, via pointing; enumerating a list of things on fingers rising in sequence. It is interesting that these meanings are not always expressed in speech, which makes the observation of a speaker’s overall behaviour essential for the understanding of a message in its entirety (cf. Gullberg and Kita 2009).

With a specific attention to hand gestures, these body movements have the potential to not only illustrate meaning, for example via iconic gestures that represent some physical features such as shape or size, but also to create it metaphorically, which can make something abstract acquire a concrete form (e.g., the concept of “love” conveyed through a gesture mimicking the shape of a heart) (see classification in McNeill 1992). Moreover, via pointing, hand gestures can draw attention to some content in speech that is particularly important or relevant; or it can reinforce a message by providing redundancy of meaning with speech (e.g., showing three fingers when saying the word “three”); or it can pace the rhythm of a speaker’s words to help the speaker speak and the listener follow. If speech is ambiguous, hand gestures may help resolve the ambiguity. While engaging in reasoning and descriptions, speakers often rely on hand gestures to facilitate the performance of these tasks. Sometimes they can acquire conventionalized forms, which the speaker assumes the interlocutor to recognize and attribute the expected meaning to them (e.g., the thumb-up gesture) (cf. Argyriou et al. 2017; Gullberg and Holmqvist 2006; Kita 2009; McNeill 1992).

Embodied cognition is the research area that draws attention to perception and action as people engage in the understanding and learning of new contents, and as they relate to the environment around them (cf. Canagarajah 2018; Goodwin 2013; Hall and Knapp 2013; Jewitt 2009; Kimura and Canagarajah 2020; Kress 2010; Matsumoto et al. 2013; Mondada 2014). In coordinating with speech, body movements can help a speaker formulate the ideas that they want to express in words (e.g., grasping an object as they name it). In so doing, body movements reflect and support people’s thinking, whether about language or other areas of knowledge, revealing that body movements can establish a tight connection with language and thought (cf. Goldin-Meadow 2003; McNeill 1992). Encoding meaning through different modes is interpreted as the reason for a lasting effect on memory: a multimodal message, while drawing together the verbal, the visual and the motor modality, incorporates different levels of meaning that contribute to a stronger memory around an expression or a word (e.g., Repetto et al. 2021). In this regard, the dual coding theory (Clark and Paivio 1991) assumes that when words are learnt in conjunction with meaningful, congruent gestures (e.g., iconic), the processing of the information is facilitated while allowing for a deeper encoding of the information itself (e.g., learning the expression “picking something up” while performing the very action). Moreover, this way of learning produces effects on the representations of language onto the brain. The reading of an action word (e.g., picking something up) activates the brain area connected with the motor action, and vice versa. Consequently, triggering motor areas can speed up the processing of words related to those movements (Pulvermüller et al. 2005). Similarly to actions, gestures are also generated by mental stimulations that occur when people think about actions and movements (Hostetter and Alibali 2019).

All together, these research underpinnings support teaching practices that create a network of information associating with new words and the concepts that attach to them. Recent studies focused on the role of body language in the teaching and learning of disciplines ranging from math to language learning and music, have provided evidence that body language does help students’ learning across different educational levels and settings (cf. Aldugom et al. 2020; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Cook et al. 2013; Farran and Morett 2024; Guarino and Wakefield 2020; Lim 2021; Macedonia and Klimesch 2014; Mejía-Laguna 2023; Rueckert et al. 2017; Sime 2008; Simones 2019). In these studies, instructors’ body language is used to: capture the students’ attention; equip them with an additional level of understanding; invite them to participate; provide them with feedback and a comfortable learning environment; and motivate them to continue to learn (cf. Congdon et al. 2017; Dargue et al. 2019; Frymier et al. 2019; Kontra et al. 2015). In other words, instructors’ body language not only ensures effective communication, but it also supports the cognitive aspects of teaching and learning, as well as the emotional and social sides of these activities (cf. Maulana et al. 2023; Stolz 2021).

Considering then that, since the Covid-19 pandemic, scholars have expanded the investigation of the role that modalities other than speech play during online teaching (e.g., Querol-Julián 2021, 2023), studies have pointed out the affordances and limits of body language with digital tools as an additional line of investigation (see Jovanovic and van Leeuwen 2018). For example, in L2 classes held online, interlocutors may find iconic and deictic gestures especially useful to support lexical searches, to reinforce or disambiguate meaning, or to create cohesion across turns of speech (e.g., Canals 2021). During online interactions, interlocutors may raise their eyebrows to indicate a lack of understanding or to indicate that some content is particularly important. Besides functioning as a way to appeal for assistance or to scaffold communicative efforts, nonverbal backchanneling such as nods, smiles, and gaze, may be particularly important to make speakers be perceived as warm and friendly. Providing this type of signal can help maintain the contact between interlocutors and contribute to the negotiation of meaning (e.g., Satar 2015). Typically, gaze and eye movement assume a very focused role during online communication, together with the sense of hearing (cf. Paradisi et al. 2021).

On the other hand, technical issues or unclear visual material can have a negative impact on the effectiveness of modalities other than speech during online instruction (cf. Paradisi et al. 2021). Moreover, the perceived closeness between interlocutors is not accompanied by the opportunity for interlocutors to use the sense of touch or smell: people cannot handshake, tap on someone else’s shoulder or arm, pass objects from one another, etc. This unavailability of the whole range of senses produces consequences, mostly on bonding, social affiliation, empathy, shared emotions, and the like (e.g., Hall 1973; Patterson et al. 2023). Studies have demonstrated that eye contact, smiling, and physical proximity, enable a direct and immediate relationship between instructors and students, and they produce positive outcomes on students’ motivation, engagement, and learning (e.g., Frymier et al. 2019).

In focusing on the changes that the Covid-19 pandemic brought to education, Godhe and Wennås Brante (2022) identify two aspects that have negatively impacted instructors’ body language during online classes. One is that human gaze is replaced by the gaze of the camera, which instructors perceive to be limiting because they are being seen while they cannot see the students. On camera, instructors need to maintain the visibility of their face all the time, which can be strenuous. On the other hand, instructors cannot see their students’ body movements because typically students keep their cameras off, which prevents them from reading their students’ body language and maintaining eye contact with them, denying the opportunity to pick up some cues regarding students’ learning, understanding, willingness to participate and speak. The other change is that technology cannot replace some physical aspects of teaching without affecting the very nature of the teaching profession (e.g., walking around the classroom to engage students during a lecture). While online, people are seen rather than being in a physical space, where the latter is an essential component of the teaching profession.

In line with this review of the literature and to continue the tradition of studies that explore instructors’ perception of the nonverbal characteristics that contribute to effective teaching in different teaching venues (cf. Alibali et al. 2013; Küçük 2023; Morell 2020; Nathan et al. 2019; Querol-Julián 2021, 2023; Salvato 2020), an exploratory study was conducted during the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic to inquire about the way professors at a Canadian university perceived their body language employment during lectures held in-person vs. online. This was a unique moment when to investigate the topic considering that the professors surveyed were transitioning back to teaching in-person after the period of teaching online, which represented a novelty to them. Because of this circumstance, participants were probably in a better position to comment on body language presence and absence in the two class formats and to provide more accurate responses to the survey proposed to them. Ultimately, this study was organized to foster multimodal literacy among instructors and promote awareness of its pedagogical potential (cf. Lim 2021). Specifically, this study set out to investigate the following two research questions:

RQ1:

Do professors at a Canadian university perceive their body language to contribute to their teaching; if so, in which circumstances?

RQ2:

What differences or affordances in body language usage do professors perceive to occur as they teach in-person vs. online?

3 Methods

3.1 Procedure and material

This study took place during the winter semester 2022 at a university in Canada.[1] The principal investigator used the university mailing list to reach the 521 professors teaching in different Departments and Faculties, and to invite them via email to fill-out a Qualtrics questionnaire inquiring about body language usage during lectures held in-person and online. The questionnaire was formulated as an adaptation of the survey used with second language instructors teaching in-person classes before the Covid-19 pandemic (Salvato 2020). The intent of this adaptation was to explore the way professors teaching disciplines other than language studies would react to the employment of body movements for pedagogical purposes, in line with the interpretations offered by Gesture Studies in Linguistics and the literature on multimodality (cf. Kendon 2004; Lim 2021; McNeill 1992). Although the survey was divided into two parts, one focused on professors’ perception of their own body language, and the other focused on professors’ interpretation of their students’ body language (Salvato 2024), this article only examines the responses collected on the first part of the survey.[2]

In the presentation of the study, professors were informed that body language was to be interpreted in its largest sense from facial expressions, to hand gestures, to postures, to any other body movement they could think of. Professors were allowed a period of a month to access the survey and decide on whether they wanted to participate in this study. In conformity with ethics guidelines, professors could contact the principal investigator via email and ask any questions they had before consenting to participate, or they could seek clarification on the questions of the survey. Completion of the questionnaire was predicted to take about 20 min.

The reasons for the questions included in the first part of the survey are now presented. To begin with, professors were asked which types of body language they think they use during teaching in-person and online. This question was meant to raise professors’ awareness of their body language as a nonverbal modality that contributes to their lectures. Besides the literature on multimodality (e.g., Azaoui 2019; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Canals 2021; Farran and Morett 2024; Kimura and Canagarajah 2020; Küçük 2023; Lim 2021; Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023; Mejía-Laguna 2023), this question is in line with the literature in Gesture Studies, which in the first place supports the important role of different body movements during any interactions and for different communicative purposes (e.g., Bavelas and Chovil 2018; Hall and Knapp 2013; Kendon 2004, 2017; Matsumoto et al. 2013; McNeill 1992; Mehrabian 1969).

The survey continues with a focus on the pedagogical functions that professors attribute to their body language. A number of options were proposed, from illustrating meaning to organizing class stages to evaluating students’ production, in line with Tellier’s (2008) classification of pedagogical gestures into: those that provide information about language, words and ideas; those that manage a class; and those that evaluate students. The survey then draws the professors’ attention to the fact that their body language may contribute to the formulation of semantic concepts such as numbers, time, shape, manner of an action, etc., which are typically studied in Linguistics (cf. Akmajian et al. 2017). In addition, the survey asks whether professors perceive their body language to combine with parts of speech when the two modalities come together. These latter questions were motivated by the fact that body movements spontaneously combine with speech in communication and are particularly well-suited to produce the semantic meanings included in the survey (e.g., Beattie and Shovelton 1999; Kita et al. 2017; McNeill 1992; McNeill et al. 2015). Also, some parts of speech (e.g., nouns instead of verbs) may be perceived to be easier to combine with body movements while teaching (cf. García-Gámez and Macizo 2019; Macedonia and Knösche 2011).

To gather additional insights into professors’ interpretation of their body language, the survey also inquired about the reasons why professors use it or not, during teaching. The options included in this question (e.g., the influence of the first language) were inspired by the literature in Gesture Studies in general, but also by the fact that body language changes across cultures (e.g., Hall 1973; Kita 2009; Patterson et al. 2023). The first part of the survey ends with a question inquiring about the types of body language professors perceive to use more frequently in-person and online.

3.2 Participants

Ninety-two professors responded to the survey questions, but 3 withdrew before submitting their answers. Although 89 questionnaires were submitted, they were not necessarily filled out completely. This is because, in the guidelines provided, participants were informed to choose all the answers that applied, but also that they could skip any questions they did not feel comfortable responding. Considering that some of the submitted questionnaires lacked substantial information, it was decided that questionnaires that provided less than 15 % of the answers be eliminated because they were deemed inadequate for data analysis. Consequently, 58 professors form the actual number of participants in this study.

The majority of the 58 professors whose responses are examined in this article were female (N = 29), aged between 41 and 50 (N = 16), declared English as the language they used growing up in their family (N = 30), and they were members of the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (N = 23), the largest Faculty on campus including different Departments ranging from Drama to Philosophy, Music, Psychology, etc. Professors in the Department of Languages in the same Faculty did not receive the email invitation because the principal investigator is a colleague at the same Department and, in compliance with ethic guidelines, she did not want to exercise any influence on her colleagues’ decision to participate in this study. In terms of student population, participants stated that they teach predominantly undergraduate students who are speakers of different languages.

4 Data analysis and results

The statistical analysis in this section focuses on professors’ perception of their body language and its roles in the four areas included in the first part of the survey (i.e., types of body language; pedagogical functions body language accomplishes; semantic contents body language helps express; and parts of speech body language associates with) as well as across the two class formats considered (i.e., in-person vs. online).[3] The option responses available in the survey were reduced to: “in-person,” “online,” “never,” and “don’t know.” If professors chose “both,” this response was merged with “online” and “in-person” alike (i.e., 1 point was added to “in-person,” and 1 point to “online”) because the main interest in this study was to compare the two class formats. Depending on which response the professors selected, a binary value was then used for each response (i.e., 0 for not selected; 1 for selected). Fisher’s exact test was chosen as the most appropriate and accurate test to use in the performance of the statistical analysis of the small sample size of this study (N = 58), also in consideration of the fact that Fisher’s exact test does not have any assumptions for data distribution.

In Table 1, the overall analysis concerning professors’ perception of their body language usage in the four areas under examination shows high statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.001, two-sided), suggesting that across the two class formats, professors perceived their body language to be more salient to them during in-person classes than online. Statistical significance was revealed for the types of body language that professors perceived to use (t (57) = 6.57, p < 0.001); for the pedagogical functions that professors’ body language accomplishes (t(57) = 9.37, p < 0.001); for the semantic contents professors’ body language conveys (t(50) = 5.65, p < 0.001); and for the parts of speech professors’ body language combines with (t(51) = 3.37, p < 0.001):

Overall analysis of perception – paired samples test.

| Paired differences | t | df | Significance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean | 95 % confidence interval of the difference | One-sided p | Two-sided p | |||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Pair 1 | Type_InPerson–Type_Online | 1.207 | 1.399 | 0.184 | 0.839 | 1.575 | 6.571 | 57 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pair 2 | Pedag_InPerson–Pedag_Online | 2.983 | 2.424 | 0.318 | 2.345 | 3.620 | 9.370 | 57 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pair 3 | Semantic_InPerson–Semantic_Online | 2.078 | 2.629 | 0.368 | 1.339 | 2.818 | 5.645 | 50 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pair 4 | Parts_InPerson–Parts_Online | 0.827 | 1.768 | 0.245 | 0.335 | 1.319 | 3.372 | 51 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

The analysis proceeded with a more specific focus on professors’ perception of the types of body language that they use during in-person and online teaching, as reported in Table 2 below. Because all the professors stated that they use their “hands” while teaching in-person and almost everyone stated the same for when they teach online, a statistical analysis could not be run on the lack of variability in this case (i.e., 58 out of 58 participants for in-person and 53 out of 58 for online). With respect to the other options, perception of using “facial expressions” revealed no statistical significance (i.e., p = 0.134, two-sided), suggesting that there was no meaningful difference between in-person vs. online. Contrastively, perception of using “eyes” in-person vs. online showed high statistical significance (i.e., p < 0.001, two-sided). The same was found for “postures,” where a high statistical significance suggests an important difference between in-person and online (i.e., p = 0.005, two-sided). When the combination “words + body language” in-person vs. online was examined, the results also revealed a statistically significant difference (i.e., p = 0.001, two-sided). On the other hand, there was no statistical significance in relation to professors’ perception of body language occurring “more in-person vs. online” (i.e., p = 0.657, two-sided):

Professors’ perception of body language types in-person vs. online.

| Hands | Not able to run test | Value | df | Exact sig. (2-Sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial expressions | Pearson chi-square | 5.994 | 1 | 0.134 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.134 | |||

| Eyes | Pearson chi-square | 29.923 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Postures | Pearson chi-square | 8.083 | 1 | 0.005 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.005 | |||

| Combination words + body language | Pearson chi-square | 16.132 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.001 | |||

| More body language in-person vs. online | Pearson chi-square | 0.706 | 1 | 0.657 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.657 |

To continue, the analysis on the pedagogical functions that professors perceived their body language to accomplish during classes held in-person vs. online revealed the scenario reported in Table 3:

Professors’ perception of body language and pedagogical functions in-person vs. online.

| Value | df | Exact sig. (2-sided) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illustrate meaning | Pearson chi-square | 23.673 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Point at people, objects, places | Pearson chi-square | 4.521 | 1 | 0.044 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.044 | |||

| Accompanying rhythm of speech | Pearson chi-square | 32.933 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Emphasize words | Pearson chi-square | 6.360 | 1 | 0.138 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.138 | |||

| Add meaning to words | Pearson chi-square | 34.014 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Organize class | Pearson chi-square | 6.015 | 1 | 0.027 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.013 | |||

| Regulate interactions | Pearson chi-square | 5.319 | 1 | 0.024 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.024 | |||

| Discipline behaviour | Pearson chi-square | 9.913 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.001 | |||

| Check comprehension | Pearson chi-square | 19.535 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Evaluate | Pearson chi-square | 26.657 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Replace words | Pearson chi-square | 31.476 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Maintain cohesion | Pearson chi-square | 35.368 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 |

Whereas “to emphasize words” was not statistically significant (i.e., p = 0.138, two-sided), all the other pedagogical functions were found to be either highly significant (i.e., p = 0.001, two-sided) (i.e., “illustrate meaning; accompany rhythm of speech; add meaning to words; discipline behaviour; checking comprehension; evaluate; replace words; maintain cohesion”), or marginally significant (i.e., “pointing,” p = 0.044, two-sided; “organize class,” p = 0.013, two-sided; “regulate interactions,” p = 0.024, two-sided). These results suggest that professors perceived a difference in the way their body language performs pedagogical functions while teaching in-person vs. online.

When perception of semantic meanings conveyed through body language was tested, the high statistical significance of the results in Table 4 suggests that professors perceived a difference in body language usage in-person vs. online (i.e., between p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, two-sided):

Professors’ body language conveying semantic meanings in-person vs. online.

| Value | df | Exact sig. (2-sided) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Pearson chi-square | 26.429 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Location | Pearson chi-square | 9.381 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.003 | |||

| People | Pearson chi-square | 17.153 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Numbers | Pearson chi-square | 34.793 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Direction | Pearson chi-square | 16.397 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Possession | Pearson chi-square | 33.333 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Plurality | Pearson chi-square | 25.758 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Shape | Pearson chi-square | 23.684 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Space | Pearson chi-square | 16.276 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Negation | Pearson chi-square | 30.650 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Manner of action | Pearson chi-square | 9.400 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Fisher’s exact test | 0.002 |

Similarly, when professors expressed their opinion about the parts of speech that associate with body language, the results in Table 5 revealed high statistical significance (i.e., p = 0.001, two-sided), suggesting that professors perceived a difference between in-person and online throughout the options of this question:

Professors’ body language associating with parts of speech in-person vs. online.

| Value | df | Exact sig. (2-sided) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete nouns | Pearson chi-square | 16.520 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Abstract nouns | Pearson chi-square | 29.792 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Verbs | Pearson chi-square | 34.918 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Prepositions | Pearson chi-square | 33.150 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Adjectives | Pearson chi-square | 29.255 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Adverbs | Pearson chi-square | 30.469 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 | |||

| Conjunctions | Pearson chi-square | 30.857 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Fisher’s exact test | <0.001 |

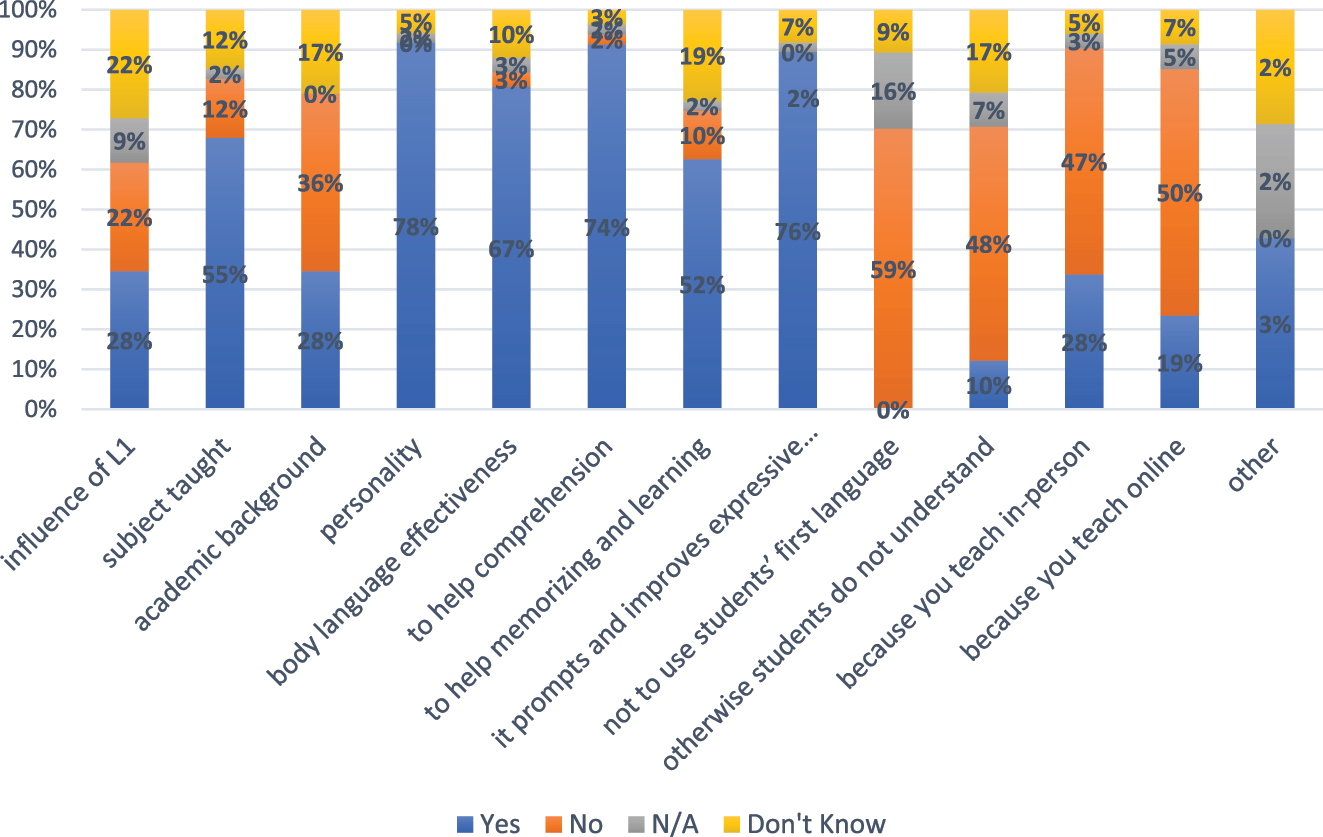

The first part of the survey ends with two questions asking professors to react to a number of reasons in favour of and against body language usage, and one question inquiring about types of body language professors think they use frequently during in-person and online teaching. Figure 1 shows the distribution of professors’ responses to the reasons in favour of body language usage:

Reasons for professors to use body language.

In Figure 1, the three responses that received the highest “yes” answers were: “your personality” (i.e., 78 %); “the fact that body language prompts and improves expressive abilities” (i.e., 76 %); and “the fact that stimuli of a different nature help comprehension” (i.e., 74 %). The three responses that received, instead, the highest “no” answers were: “the fact that you don’t want to use your students’ first language” (i.e., 59 %); “the fact that you teach online” (i.e., 50 %); “the fact that otherwise students do not understand” (i.e., 48 %,). Although less prominently, professors responded “don’t know” especially with: “the influence of their first language” (i.e., 22 %); “the fact that body language aids in memorizing and learning” (i.e., 19 %); “the fact that otherwise students do not understand” and professors’ “academic background” (i.e., 17 %, respectively). Moreover, some professors offered the following comments that reinforced their views on the importance of body language in different circumstances of communication, including in education: “habitually express the same way online and in person;” “I am just a hand talker it is not driven by pedagogy at all. I use the same gestures in social conversation;” “the fact that it feels natural to do so;” “there are many variables at play, but physical engagement seems to help with the engagement of the group and the discussions that take place. However, I have noticed my use of the body and gaze has become less confident even in person.”

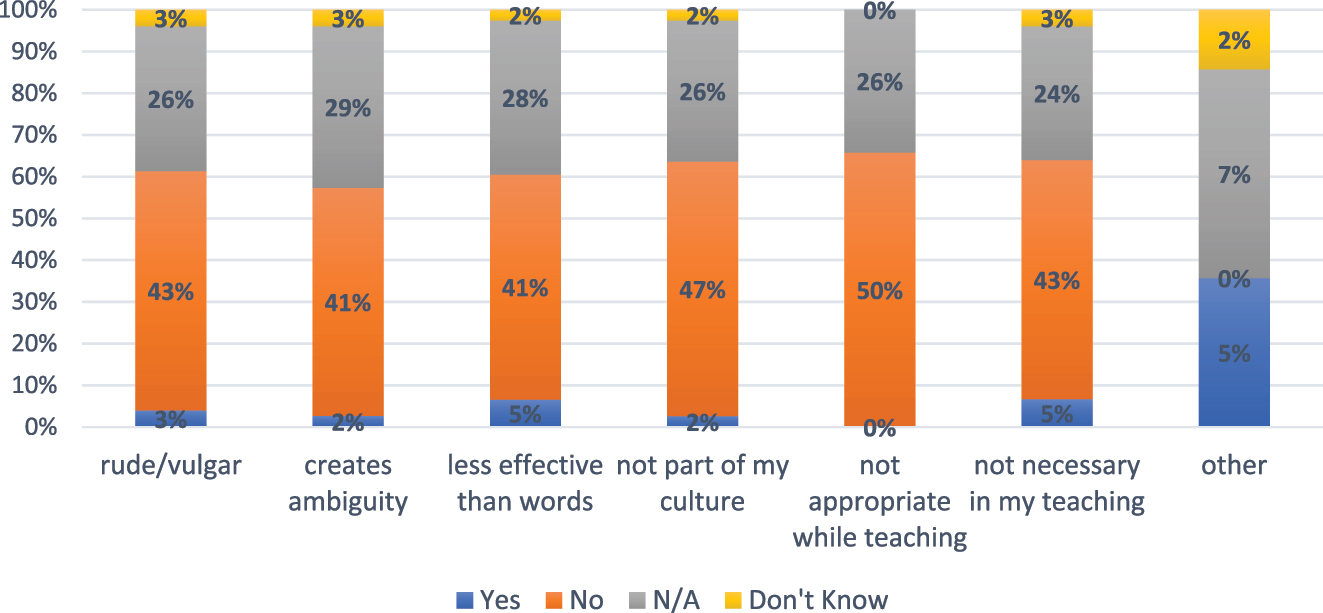

To follow, Figure 2 shows professors’ reaction to a series of reasons against body language usage during teaching:

Reasons for professors not to use body language.

The highest responses in Figure 2 gather around “no” and “n/a,” whereas only between 2 % and 5 % of the answers were “yes” and “don’t know.” Most professors disagreed with body language being: “not appropriate while teaching” (i.e., 50 %); “not part of my culture” (i.e., 47 %); “rude, vulgar” and “not necessary in teaching” (i.e., 43 %, respectively). Moreover, four professors offered these comments that explain when they use body language less: “I feel constrained by the online format and so I tend to restrain my hand/arm movements;” “not convenient;” “sometimes if I want the students to listen to a piece of text, I use less body language so that they focus in on what they are hearing. My body language becomes more concise when what I want them to hear is very specific or complicated”; “it is not expected.”

As for the question concerning frequent body language types in-person and online, most professors responded “hands” and “face” for both teaching venues.

5 Discussion and conclusions

This exploratory study aimed at investigating the way professors of different disciplines at a university in Canada perceived their body language to contribute to their teaching in general and, also, in a comparative manner between lectures held in-person and online. Overall, participants in this study believed their body language to be a salient modality of communication, effective in supporting their teaching (cf. Aldugom et al. 2020; Alibali et al. 2013; Argyriou et al. 2017; Azaoui 2019; Belhiah 2013; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Farran and Morett 2024; Küçük 2023; Lim 2021; Maulana et al. 2023; Mejía-Laguna 2023; Morell 2020; Nathan et al. 2019; Sato 2020; Stolz 2021; Valenzeno et al. 2003). Professors perceived that their body language integrates speech (McNeill 1992) and facilitates the pedagogical mission (Tellier 2008), especially when teaching takes place in a physical classroom where body language can make a greater contribution to their lectures, as for types, pedagogical functions, semantic contents, and parts of speech it typically associates with (see Table 1). These findings are confirmed in Figures 1 and 2, where the majority of the professors agreed with body language being necessary and appropriate while teaching, and being effective in the promotion of students’ comprehension, expression, memorization, and learning (cf. Clark and Paivio 1991; Cohen 1989; Congdon et al. 2017; Engelkamp and Krumnacker 1980; Engelkamp and Zimmer 1994; Hostetter and Alibali 2019; Kita et al. 2017; Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023; Pulvermüller et al. 2005; Repetto et al. 2021).

In spite of the limitations of this study (see below), there are a number of pedagogical insights and implications that derive from the findings reported in this article. To begin with, this study was conducted at a unique moment in history, the aftermaths of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which the professors surveyed were transitioning back to teaching in-person after the period when they were teaching online. This moment in time created a more suitable condition to investigate professors’ perception of body language usage because the period of online teaching probably made them more aware of the differences between the two class formats. The return to in-person classes likely helped the participants in this study gain more consciousness of the changes that they had to implement while online, including with respect to body language usage.

The opportunity to reflect on the role of body language in teaching was probably a novelty for many of the professors contacted for this study. Moreover, because body language behaviour generally lies outside of a person’s level of awareness (cf. Patterson et al. 2023), and the instructors in this study were new to the online format of classes during the Covid-19 period, completing a survey inquiring about body language usage in two class settings likely posed some challenges to the participants. These factors can explain why a minority of the professors contacted decided to participate in the study, and among those who submitted their questionnaire, some did not fully complete it, or they showed uncertainty through “don’t know” answers. The difficulty of the exercise proposed is also revealed by a lack of clarity on the results of one of the key questions of the survey: which class format correlates with “more body language.” Statistically, this question did not show significant results (see Table 2); in terms of frequency, although a higher percentage of participants selected “because you teach in-person” compared to “because you teach online,” a specific class venue was not the dominant reason why professors believed to use body language (see Figure 1) (cf. Godhe and Wennås Brante 2022; Paradisi et al. 2021).

On the other hand, professors whose discipline includes the study of the body as part of their pedagogical mission (e.g., medicine, drama) may have related better to the questions of this survey. It is true that the professors who fully responded to the questionnaire showed sensitivity towards the topic of this study: they perceived body language to be a composite notion constituted by a number of body parts and movements, each contributing individually and together, to the interaction that takes place in the classroom (cf. Hall and Knapp 2013; Matsumoto et al. 2013; Patterson et al. 2023). Except for the hands, the other body language types revealed some differences across class venue (see Table 2). Participants believed eyes and postures to be more salient in-person than online, whereas facial expressions were interpreted as less remarkably different across class format. It is true that, while online, professors are more limited in assuming different postures because they need to maintain the visibility of their face on the screen. Additionally, most students keep their cameras off, and this reduces the opportunities for professors to make eye contact with their interlocutors (cf. Godhe and Wennås Brante 2022; Paradisi et al. 2021). These findings suggest that the physical classroom is the setting where the professors in this study feel they can establish eye contact and assume different postures in more natural and typical ways.

Contrastively, the results concerning facial expressions in the two class venues were not as clear (see Table 2), suggesting some difficulty for the participants to comment on their facial expressions, especially in isolation from other types of body language and the context where they may occur (cf. Hall and Knapp 2013; Matsumoto et al. 2013; Patterson et al. 2023). This finding points to the necessity of encouraging more attention to facial expressions, for example during teacher’s training programs and workshops, when instructors could be helped to gain familiarity with the potential of facial expressions in conveying meaning, including their combination with other body language types and their adaptations to the variety of teaching formats. As a general insight from this study, the pedagogical opportunities (e.g., to demonstrate verbal meaning) that body language types (e.g., postures vs. face) enable need to be integrated into teacher’s training programs. This would ensure that the numerous research findings available in the literature and indicating that body language promote education are actually shared with instructors (cf. Goldin-Meadow and Alibali 2013; Kontra et al. 2015; Lim 2021; Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023; Rueckert et al. 2017; Sime 2008; Simones 2019; Stam and Urbanski 2023; Stolz 2021). The link between research findings and the classroom setting would also contribute to counteracting the long-standing tradition in education that has generally privileged speech over other modalities of instruction (cf. Macedonia 2019). The current study represents one attempt towards the exploration of body language as a modality that can change traditional ways of formulating teaching practices and can foster multimodal literacy among university professors (cf. Lim 2021). Continuing to underrepresent the role of body language in education perpetuates the distance between the way people communicate in the classroom and the way they naturally communicate in other settings, where body movements regularly integrate speech (cf. Kendon 2004, 2017; McNeill 1992; McNeill et al. 2015).

This study offers then insights into professors’ perception of their body language enabling the performance of different pedagogical functions. This is another area that can inform teacher’s training programs considering that the participants seemed to be inclined to identify some pedagogical functions as more easily performed through body language, also in accordance with class venue. To begin with, the majority of the participants stated that they employ body language because of “the characteristics of the subject that they teach” (Figure 1), which confirms the pedagogical value they attribute to body language. When the professors’ perception across class formats was examined statistically, the following differences emerged (see Table 3). While teaching in-person, body language was perceived to play a more salient role in the performance of these pedagogical functions: “to illustrate meaning; to accompany the rhythm of speech; to add meaning to words; to discipline behaviour; to check comprehension; to evaluate; to replace words; and to maintain cohesion.” This finding suggests that the physical presence of students, the opportunity to establish eye contact with them, and the availability of the classroom space, were interpreted as essential conditions for this set of pedagogical functions to be performed with the help of body language (cf. Azaoui 2019; Bernad-Mechó 2023; Farran and Morett 2024; Lim 2021; Mathias and von Kriegstein 2023; Mejía-Laguna 2023).

On the other hand, “to point at, to organize the stages of a class, to regulate interactions” were perceived to change less remarkably across class formats, suggesting reduced differences between class venues. As for “to emphasize words,” professors expressed agreement on using body language to this avail. The statistical results revealed this as the only pedagogical function not to be perceived to differ significantly across class format, suggesting an equivalent usage of body language in-person and online. Overall, the results of this question call for further investigations into the characteristics that body language could assume to perform pedagogical functions in different class venues (e.g., the instructor’s index finger pointing to a referent while raising eyebrows to draw students’ attention could be used in-person and online).

As an additional insight deriving from this study, participants agreed with the practice of combining body language with speech (see Figures 1 and 2), attributing salience to this pedagogical choice. A statistical difference between in-person and online emerged across the two class formats (see Table 2): professors perceived the physical classroom to enable a better opportunity to use speech and body language together, whereas online classes probably limited this opportunity and demanded new ways of organizing the verbal and nonverbal behaviour (cf. Jovanovic and van Leeuwen 2018; Querol-Julián 2021, 2023; Satar 2015). Compared to the online venue, then, professors believed the physical classroom to be more amenable to the expression of meanings through body language (see Table 4) and to the association of body language with parts of speech (see Table 5) (cf. Beattie and Shovelton 1999; García-Gámez and Macizo 2019; Kita et al. 2017; Macedonia and Knösche 2011; McNeill 1992; McNeill et al. 2015). These findings suggest that the online teaching venue likely represented a challenge for the participants in this study, and the reason could very well be that they lacked preparation for this change. It is true that, when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, most educational settings transitioned onto the online format by instructing educators about the technicalities concerning online platforms that were going to be used. Generally, little to no attention was paid to training instructors about the pedagogically sound practices that could be employed to make body language effective while teaching online (cf. Godhe and Wennås Brante 2022; Paradisi et al. 2021). Without this training, many instructors around the world including the participants in this study were left to their own devices in formulating their lectures online.

In conclusion, this exploration of professors’ perception of body language variation across class formats created an opportunity to expose a group of educators to concepts studied by multimodality research in the promotion of effective pedagogy. Like the university professors in this study, instructors can gain a better appreciation of body language versatility if opportunities to learn about this matter are available to them, especially through teacher’s training programs and workshops. Considering that educators are typically intentional about their teaching strategies and techniques, and they are responsive to what works and what does not work in class, it is expected that many would welcome the possibility of participating in training sessions that address body language awareness and employment for teaching effectiveness in different class venues.

6 Limitations of this study

The limitations of this study should be noted. To begin with, the small pool of participants needs to be expanded to better explore professors’ perception of body language during teaching. Besides screen fatigue from the Covid-19 period and the length of the online survey, the dropout of participation in this study may be due to the Linguistics-based questions (particularly, sections c and d in the survey) that could have been too challenging for lecturers who teach disciplines other than language studies. Moreover, considering that the participants in this study only taught online for a period, this class format was probably too novel for them to be able to respond to questions about body language occurrences during classes held in this type of venue in contrast with classes held in-person. Instructors who are trained to teach online may be able to better relate to the survey questions because they are likely more aware of their nonverbal behaviours in this teaching context. Furthermore, because the participants were invited to think about body language in its largest sense, the survey questions and the discussion in this article are not sufficiently focused on each individual type of body language (e.g., hand gestures vs. facial expressions vs. postures), offering only a broad view on professors’ body language perception. Finally, this study does not provide insights into how and why professors believe that body language usage is important. This limitation urges a vital avenue for future research, especially the inclusion of qualitative data (e.g., through interviews, focus group, or open-ended questions) that can provide a deeper and more powerful understanding of the contexts and rationale of body language usage.

Appendix: Body language during in-person and online university lectures: The professor’s view

Select ALL that apply and if you choose ‘other,’ please specify.

| 1. DURING YOUR LECTURES… | |||||

| a) In addition to speaking: | in-person | online | both | never | don’t know |

| you use your hands | |||||

| you use facial expressions | |||||

| you use your eyes | |||||

| you use different postures | |||||

| you use ____________________ | |||||

| you value the combination “words + body language” | |||||

| you use more body language | |||||

| b) You use body language to: | in-person | online | both | never | don’t know |

| illustrate the meaning of words or new concepts | |||||

| point at people or objects or places | |||||

| accompany the rhythm of your speech | |||||

| emphasize your words | |||||

| add meaning to your words | |||||

| organize your class (e.g., moving from lecturing to group work) | |||||

| regulate interactions in the classroom | |||||

| discipline behaviour in class | |||||

| check comprehension | |||||

| evaluate production | |||||

| replace words | |||||

| maintain cohesion (e.g., to maintain the same subject-matter) | |||||

| other_________________________ | |||||

| c) You note that you use body language to convey these semantic categories: | |||||

| time | in-person | online | both | never | don’t know |

| location | |||||

| people | |||||

| numbers | |||||

| direction | |||||

| possession | |||||

| plurality | |||||

| shape | |||||

| space | |||||

| negation | |||||

| manner of an action (e.g., running, walking) | |||||

| other____________________________ | |||||

| d) You note that you use body language generally with: | |||||

| concrete nouns (e.g., table) | in-person | online | both | never | don’t know |

| abstract nouns (e.g., beauty) | |||||

| verbs (e.g., to read) | |||||

| prepositions (e.g., in, to) | |||||

| adjectives (e.g., large, blue) | |||||

| adverbs (e.g., slowly, well) | |||||

| conjunctions (e.g., and, but) | |||||

| other____________________________ | |||||

| e) When you use body language, you attribute this choice to: | |||||

| the influence of your first language | yes | no | n/a | don’t know | |

| the characteristics of the subject that you teach | |||||

| your academic background | |||||

| your personality | |||||

| its effectiveness (e.g., it helps manage a class) | |||||

| the fact that stimuli of a different nature help comprehension | |||||

| the fact that body language aids in memorizing and learning | |||||

| the fact that body language prompts and improves expressive abilities | |||||

| the fact that you do not want to use your students’ first language | |||||

| the fact that otherwise students do not understand | |||||

| the fact that you teach in-person | |||||

| the fact that you teach online | |||||

| other____________________________ | |||||

| f) If during your lectures you do not use body language, this is because: | |||||

| it is rude, vulgar | yes | no | n/a | don’t know | |

| it creates ambiguity | |||||

| it is less effective than words | |||||

| it is not part of my culture | |||||

| it is not appropriate while teaching | |||||

| it is not necessary in my teaching | |||||

| other____________________ | |||||

| g) Please complete the following statement. | |||||

| In your teaching in-person, you frequently use this type of body language _________________ | |||||

| h) Please complete the following statement. | |||||

| In your teaching online, you frequently use this type of body language_____________________ | |||||

References

Akmajian, Adrian, Ann K. Farmer, L. Bickmore, Richard A. Demers & Robert M. Harnish. 2017. Linguistics. An introduction to language and communication. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Aldugom, Mary, Kimberly Fenn & Susan W. Cook. 2020. Gesture during math instruction specifically benefits learners with high visuospatial working memory capacity. Cognitive Research 5. 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00215-8.Search in Google Scholar

Alibali, Martha W., Andrew G. Young, Noelle M. Crooks, Amelia Yeo, Matthew S. Wolfgram, Iasmine M. Ledesma, Mitchell J. Nathan, Ruth B. Church & Erik J. Knuth. 2013. Students learn more when their teacher has learned to gesture effectively. Gesture 13(2). 210–233. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.13.2.05ali.Search in Google Scholar

Argyriou, Paraskevi, Christine Mohr & Sotaro Kita. 2017. Hand matters: Left-hand gestures enhance metaphor explanation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 43(6). 874–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000337.Search in Google Scholar

Azaoui, Brahim. 2019. Multimodalité, transmodalité et intermodalité: Considérations épistémologiques et didactiques. Revue de recherches en littératie médiatique multimodale 10. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065526ar.Search in Google Scholar

Bavelas, Janet & Nicole Chovil. 2018. Some pragmatic functions of conversational facial gestures. Gesture 17(1). 98–127. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.00012.bav.Search in Google Scholar

Beattie, Geoffrey & Heather Shovelton. 1999. Mapping the range of information contained in the iconic hand gestures that accompany spontaneous speech. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 18(4). 438–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x99018004005.Search in Google Scholar

Belhiah, Hassan. 2013. Using the hand to choreograph instruction: On the functional role of gesture in definition talk. The Modern Language Journal 97(2). 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12012.x.Search in Google Scholar

Bernad-Mechó, Edgar. 2023. Multimodal (inter)action analysis for the study of lectures: Active and passive uses of metadiscourse. Multimodal Communication 12(1). 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2023-0007.Search in Google Scholar

Campisi, Emanuela & Asli Özyürek. 2013. Iconicity as a communicative strategy: Recipient design in multimodal demonstrations for adults and children. Journal of Pragmatics 47(1). 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.12.007.Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, Suresh. 2018. Materializing ‘competence’: Perspectives from international STEM scholars. The Modern Language Journal 102(2). 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12464.Search in Google Scholar

Canals, Laia. 2021. Multimodality and translanguaging in negotiation of meaning. Foreign Language Annals 54. 647–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12547.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, James M. & Allan Paivio. 1991. Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review 3(3). 149–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01320076.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, Ronald L. 1989. Memory for action events: The power of enactment. Educational Psychology Review 1(1). 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01326550.Search in Google Scholar

Congdon, Eliza L., Miriam A. Novack, Neon Brooks, Hemani-Lopez Naureen, Lucy O’Keefe & Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2017. Better together: Simultaneous presentation of speech and gesture in math instruction supports generalization and retention. Learning and Instruction 50. 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.03.005.Search in Google Scholar

Cook, Susan W., Ryan G. Duffy & Kimberly M. Fenn. 2013. Consolidation and transfer of learning after observing hand gesture. Child Development 84(6). 1863–1871. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12097.Search in Google Scholar

Dahl, Tove Irene & Susanne Ludvigsen. 2014. How I see what you’re saying: The role of gestures in native and foreign language listening comprehension. The Modern Language Journal 98(3). 813–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12124.x.Search in Google Scholar

Dargue Nicole, Naomi Sweller & Michael P. Jones. 2019. When our hands help us understand: A meta-analysis into the effects of gesture on comprehension. Psychological Bulletin 145(8). 765–784. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000202.Search in Google Scholar

Engelkamp, Johannes & Hubert D. Krumnacker. 1980. Image- and motor-processes in the retention of verbal materials. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie 27. 511–533.Search in Google Scholar

Engelkamp, Johannes & Hubert D. Zimmer. 1994. The human memory: A multimodal approach. The University of Michigan: Hogrefe.Search in Google Scholar

Farran, Bashar M. & Laura Morett. 2024. Multimodal cues in L2 lexical tone acquisition: Current research and future directions. Frontiers in Education 9. 1410795. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1410795.Search in Google Scholar

Frymier, Ann B., Zachary W. Goldman & Christopher J. Claus. 2019. Why nonverbal immediacy matters: A motivation explanation. Communication Quarterly 67(5). 526–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2019.1668442.Search in Google Scholar

García-Gámez, Ana B. & Pedro Macizo. 2019. Learning nouns and verbs in a foreign language: The role of gestures. Applied Psycholinguistics 40. 473–507. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716418000656.Search in Google Scholar

Godhe, Anna-Lena & Eva Wennås Brante. 2022. Interacting with a screen – The deprivation of the ‘teacher body’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers and Teaching. 1–16.10.1080/13540602.2022.2062732Search in Google Scholar

Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2003. Hearing gesture: How our hands help us think. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.10.1037/e413812005-377Search in Google Scholar

Goldin-Meadow, Susan & Martha W. Alibali. 2013. Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language. Annual Review of Psychology 64. 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143802.Search in Google Scholar

Goodwin, Charles. 2013. The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. The Journal of Pragmatics 46. 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

Guarino, Kathrine F. & Elizabeth M. Wakefield. 2020. Teaching analogical reasoning with co-speech gesture shows children where to look, but only boosts learning for some. Frontiers in Psychology 11. 575628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575628.Search in Google Scholar

Gullberg, Marianne & Kenneth Holmqvist. 2006. What speakers do and what addressees look at: Visual attention to gestures in human interaction live and on video. Pragmatics and Cognition 14(1). 53–82. https://doi.org/10.1075/pc.14.1.05gul.Search in Google Scholar

Gullberg, Marianne & Sotaro Kita. 2009. Attention to speech-accompanying gestures: Eye movements and information uptake. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 33(4). 251–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-009-0073-2.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Edward T. 1973. The silent language. New York: Anchor Books.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Judith A. & Mark L. Knapp (eds.). 2013. Nonverbal communication. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110238150Search in Google Scholar

Hostetter, Autumn B. & Martha W. Alibali. 2019. Gesture as simulated action: Revisiting the framework. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 26. 721–752. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1548-0.Search in Google Scholar

Jewitt, Carey. 2009. An introduction to multimodality. In Carey Jewitt (ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis, 14–27. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Jovanovic, Danika & Theo van Leeuwen. 2018. Multimodal dialogue on social media. Social Semiotics 28(5). 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504732.Search in Google Scholar

Kendon, Adam. 2004. Gesture. Visible action as utterance. Cambridge: CUP.10.1017/CBO9780511807572Search in Google Scholar

Kendon, Adam. 2017. Pragmatic functions of gestures. Gesture 16(2). 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.16.2.01ken.Search in Google Scholar

Kimura, Daisuke & Suresh Canagarajah. 2020. Embodied semiotic resources in research group meetings: How language competence is framed. Journal of Sociolinguistics 24(5). 634–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12435.Search in Google Scholar

Kita, Sotaro. 2009. Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language & Cognitive Processes 24(2). 145–167. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003059783-1.Search in Google Scholar

Kita, Sotaro, Martha W. Alibali & Mingyuan Chu. 2017. How do gestures influence thinking and speaking? The gesture-for-conceptualization hypothesis. Psychological Review 124(3). 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000059.Search in Google Scholar

Kontra, Carly, Daniel J. Lyons, Susan M. Fischer & Sian L. Beilock. 2015. Physical experience enhances science learning. Psychological Science 26(6). 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569355.Search in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther R. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Küçük, Turgay. 2023. The power of body language in education: A study of teachers’ perception. International Journal of Social Sciences and Educational Studies 10(3). 275–289.10.23918/ijsses.v10i3p275Search in Google Scholar

Lim, Fei Victor. 2021. Designing learning with embodied teaching: Perspectives from multimodality. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429353178Search in Google Scholar

Macedonia, Manuela. 2019. Embodied learning: Why at school the mind needs the body. Frontiers in Psychology 10. 2098. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02098.Search in Google Scholar

Macedonia, Manuela & Wolfgang Klimesch. 2014. Long-term effects of gestures on memory for foreign language words trained in the classroom. Mind, Brain, and Education 8(2). 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12047.Search in Google Scholar

Macedonia, Manuela & Thomas R. Knösche. 2011. Body in mind: How gestures empower foreign language learning. Mind, Brain, and Education 5(4). 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228x.2011.01129.x.Search in Google Scholar

Mathias, Brian & Katharina von Kriegstein. 2023. Enriched learning: Behavior, brain, and computation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 27(1). 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.10.007.Search in Google Scholar

Matsumoto, David, Mark G. Frank & Hyi S. Hwang (eds.). 2013. Nonverbal communication: Science and applications. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.10.4135/9781452244037Search in Google Scholar

Maulana, Ridwan, Michelle Helms-Lorenz & Robert Klassen (eds.). 2023. Effective teaching around the world: Theoretical, empirical, methodological and practical insights. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4Search in Google Scholar

McNeill, David. 1992. Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

McNeill, David, Elena T. Levy & Susan D. Duncan. 2015. Gesture in discourse. In Deborah Tannen, Heidi Hamilton & Deborah Schiffrin (eds.), Handbook of discourse analysis, 262–319. New Jersey: Wiley.10.1002/9781118584194.ch12Search in Google Scholar

Mehrabian, Albert. 1969. Significance of posture and position in the communication of attitude and status relationships. Psychological Bulletin 71(5). 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027349.Search in Google Scholar

Mejía-Laguna, Jorge A. 2023. Critical learning episodes in the EFL classroom: A multimodal (inter)action analytical perspective. Multimodal Communication 12(1). 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2023-0006.Search in Google Scholar

Mondada, Lorenza. 2014. The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 65. 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

Morell, Teresa. 2020. EMI teacher training with a multimodal and interactive approach: A new horizon for LSP specialists. Language Value 12. 56–87. https://doi.org/10.6035/languagev.2020.12.4.Search in Google Scholar

Nathan, Mitchell J., Amelia Yeo, Rebecca Boncoddo, Autumn B. Hostetter & Martha W. Alibali. 2019. Teachers’ attitudes about gesture for learning and instruction. Gesture 18(1). 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.00032.nat.Search in Google Scholar

Paradisi, Paolo, Marina Raglianti & Laura Sebastiani. 2021. Online communication and body language. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 15. 709365. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.709365.Search in Google Scholar

Patterson, Miles L., Alan J. Fridlund & Carlos Crivelli. 2023. Four misconceptions about nonverbal communication. Perspectives on Psychological Science 18(6). 1388–1411. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221148142.Search in Google Scholar

Pulvermüller, Friedemann, Olaf Hauk, Vadim V. Nikulin & Risto J. Ilmoniemi. 2005. Functionallinks between motor and language systems. European Journal of Neuroscience 21(3). 793–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03900.x.Search in Google Scholar

Querol-Julián, Mercedes. 2021. How does digital context influence interaction in large live online lectures? The case of english-medium instruction. European Journal of English Studies 25(3). 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2021.1988265.Search in Google Scholar

Querol-Julián, Mercedes. 2023. Multimodal interaction in English-medium instruction: How does a lecturer promote and enhance students’ participation in a live online lecture? Journal of English for Academic Purposes 61. 101207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101207.Search in Google Scholar

Repetto, Claudia, Brian Mathias, Otto Weichselbaum & Manuela Macedonia. 2021. Visualrecognition of words learned with gestures induces motor resonance in the forearm muscles. Scientific Report 11. 17278. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96792-9.Search in Google Scholar

Rueckert, Linda, Ruth B. Church, Andrea Avila & Theresa Trejo. 2017. Gesture enhances learning of a complex statistical concept. Cognitive Research 2. 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0036-1.Search in Google Scholar

Salvato, Giuliana. 2020. Awareness of the role of the body in the pedagogy of Italian in Canada and in Italy. Language Awareness 29(1). 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1718683.Search in Google Scholar

Salvato, Giuliana. 2024. The salience of students’ body language during in-person and online lectures at a Canadian university. Multimodal Communication 13(3). 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1515/mc-2023-0062.Search in Google Scholar

Satar, Müge. 2015. Sustaining multimodal language learner interactions online. Calico Journal 32(3). 449–479. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v32i3.26508.Search in Google Scholar

Sato, Rintaro. 2020. Gesture in EFL classroom: Their relations with complexity, accuracy, and fluency in EFL teachers’ L2 utterances. System 89(1). 102215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102215.Search in Google Scholar

Sime, Daniela. 2008. “Because of her gesture, it is very easy to understand”: Learners’ perceptions of teachers’ gestures in the foreign language class. In Steven G. McCafferty & Gale Stam (eds.), Gesture: Second language acquisition and classroom research, 259–280. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Simones, Lilian. 2019. Understanding the meaningfulness of vocal and instrumental music teachers’ hand gestures through the teacher behavior and gesture framework. Frontiers in Education 4. 141. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00141.Search in Google Scholar

Stam, Gale & Kimberly Buescher Urbanski (eds.). 2023. Gesture and multimodality in second language acquisition. A research guide. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003100683Search in Google Scholar

Stolz, Steven A. (ed.). 2021. The body, embodiment, and education. An interdisciplinary approach. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003142010Search in Google Scholar

Tellier, Marion. 2008. Dire avec des gestes. Le Français dans le monde. Recherches et applications 44. 40–50.Search in Google Scholar

Valenzeno, Laura, Martha W. Alibali & Roberta Klatzky. 2003. Teachers’ gestures facilitate students’ learning: A lesson in symmetry. Contemporary Educational Psychology 28. 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0361-476x(02)00007-3.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Use of inscribed objects in roleplay training sessions at a Japanese insurance company

- Visual and multimodal literacies in secondary education in Spain: voices from English language teachers

- The marketization of higher education in China: a comparative multimodal genre analysis between top-public and international universities

- Sustainability as an element of corporate identity: multimodal analysis of an Italian coffee company’s website

- Communicating political achievements: a semiotic analysis of political posters in the linguistic landscape of Tanzania

- From aspiring to authentic engineers: prioritizing real people and real problems in engineering through service design methodology

- Whoosh! visual depictions of direction, speed, and temporality: a corpus analysis of motion events in global comics

- Sharing experience or selling service?: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of self-proclaimed Hong Kong female PhD student identity in Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book)

- Professors’ perception of body language in the aftermath of the Covid-19 online teaching period

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Use of inscribed objects in roleplay training sessions at a Japanese insurance company

- Visual and multimodal literacies in secondary education in Spain: voices from English language teachers

- The marketization of higher education in China: a comparative multimodal genre analysis between top-public and international universities

- Sustainability as an element of corporate identity: multimodal analysis of an Italian coffee company’s website

- Communicating political achievements: a semiotic analysis of political posters in the linguistic landscape of Tanzania

- From aspiring to authentic engineers: prioritizing real people and real problems in engineering through service design methodology

- Whoosh! visual depictions of direction, speed, and temporality: a corpus analysis of motion events in global comics

- Sharing experience or selling service?: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of self-proclaimed Hong Kong female PhD student identity in Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book)

- Professors’ perception of body language in the aftermath of the Covid-19 online teaching period