Abstract

Recent changes in Higher Education (HE) approaches to content delivery, coupled with breakthroughs in the Information and Communications Technology field, have led to a whole new multimodal approach to teaching (Jewitt, C. 2009). In: Jewitt, C. (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. Routledge, London & New York; Jewitt, C. (2013). Multimodal methods for researching digital technologies. In: Jewitt, C. and Brown, B. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of digital technology research. Sage, London, pp. 250–265; Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. Bloomsbury Academic, London). Multimodality in language teaching increasingly draws on multiple channels of communication and not simply text on a page. Multimodal awareness and competence are also paramount in intercultural and interpersonal communication, which has become increasingly common in today’s global workplace. Through the description of the activities implemented in the English for Professional Purposes (EPP) course entitled English for the World of Work, held at the University of Verona, we will illustrate our multimodal, EPP framework based on Littlewood’s learning continuum, which ranges from analytical study to experiential practice (2014). Our principal aim, however, is to highlight ways in which the didactic framework fosters an awareness of and competence in key areas such as multimodal competence and intercultural awareness as skills required for effective communication in today’s world of work.

1 Introduction

Lectures have traditionally been the key pedagogical tool in Higher Education (HE), where foreign language study often focuses on the top-down presentation of content rather than the development of skills. This delivery mode, however, has recently come in for considerable criticism, particularly in the USA (Atanga et al. 2015; De Los Santos et al. 2016). The debate on HE content delivery currently ranges from those who are in favour of traditional models to those who seek to transform the educational system completely. Increasingly in contemporary contexts, there is a call for didactic choices to reflect the communication norms of contemporary learners, which ultimately means a shift to a more interactional approach within HE teaching contexts.

The need for pedagogical change has also been triggered by breakthroughs in the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) field. These have led not only to the development of new teaching and learning materials and computer mediated instruction, called for already in the field of English for Academic Purposes (EAP) at the beginning of the century (Hyland and Hamp-Lyons 2002; Slaouti 2002; Warschauer 2002), but also to a whole new multimodal approach to teaching (Jewitt 2009, 2013; Kress and van Leeuwen 2001). Multimodality in teaching is not entirely new, since spoken and written language as well as visual aids and sound have long been the norm; however, in an ICT-mediated approach, the affordances of such modes can be more fully used with the introduction of video, with learner production and interaction such as discussions or project work, which extends teaching and enriches it with an array of tools. Indeed, “[i]nteractive practices in digital learning environments include accessing a range of multimodal representation and creating opportunities to demonstrate what [learners] know in an increasing range of modes” (Wang Guénier 2020, p. 219).

Perhaps as a result of this focus on ICT, Blended Learning (BL) has increasingly been adopted for HE content delivery by a number of institutions, where the ‘blend’ is usually taken to refer to a systematic use of digital technology combined with a face to face (f2f) element, in the form of a traditional, physical classroom setting (Hartle 2018; Bates 2016; Driscoll 2002; Friesen 2012; Laughlin et al. 2006; Sharma and Barrett 2007; Tomlinson and Whittaker 2013). Friesen, furthermore, expanded on Driscoll’s (2002) widely cited definition to include not only the combination of technological with f2f aspects, but the “range of possibilities” (Friesen, Op. cit.: 1) provided by the combination of online contexts with f2f ones. In addition, Picciano stressed the fact that a multimodal model for BL offers a range of tasks and materials that provide learning opportunities for learners from different generations, personality types and with different learning strategies, meeting the needs of a “wide spectrum of students” (Picciano 2009, p. 7).

Whether or not BL as an approach is as successful as – or even more successful than – traditional models depends on many factors, not least the way the blend is implemented. Jewitt (2006) also emphasizes the need to rethink educational practices. It is not only the use of technological tools that makes a difference in the learning situation but, as she claims, it is rather the interrelationship between multiple semiotic resources, both online and f2f, that are the key factors. Undoubtedly, there is a need for the affordances of the online and the f2f contexts to be applied in a well-thought-out approach, with a solid theoretical framework at its basis.

Bearing this in mind, our paper focuses on a professional development course, described in greater detail below, devised at the University of Verona, Italy, which forms the basis for a case study. The aim of the article is to illustrate the implementation of a theoretical framework for the teaching of English for Professional Purposes (EPP)[1] in BL, highlighting task types that develop multimodal (linguistic and visual) literacy and competence in specific writing and oral tasks designed to foster effective communication in today’s increasingly international and multicultural world of work.

We will first introduce the course itself and describe the theoretical framework adopted for blended EPP and for the use of English as a language of shared communication in the workplace (English as Business Lingua Franca – BELF); then, we will move on to discuss multimodality within the course, looking at both pedagogy and content for professional writing and speaking.

2 “English for the world of work (EWW)”: bridging the gap between the theoretical and the practical

The EWW course, developed by the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at the University of Verona, aims to develop the key English language competencies required in the (Italian) world of work. It caters for university students, both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels and from differing departments, as well as for professionals already using English at their workplace in a range of fields. In line with the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), it views English communication as a socio-cognitive construct (Council of Europe 2001), and the learning process as a constructivist framework of co-creating knowledge and developing skills, which is particularly advantageous for learners with different strengths working together to co-construct new communication skills.

This course came about as a result of the findings in a survey which called for EPP development in Italy. The worldwide survey English at Work, carried out jointly by Cambridge English Language Assessment and QS[2] (2016) in September 2016,[3] organized its findings according to country. In this survey, Italy ranked fifth regarding the need for professional English language training. Ninety-six percent of the Italian employers interviewed considered English training to be essential in their companies, particularly regarding the productive skills of speaking and writing. Key areas which emerged from the survey were speaking skills, writing emails, participating in meetings, and reading and dealing with reports.

Therefore, EWW aims to bridge the gap between the theoretical study of English language undertaken in mainstream university language courses and the practical English language communication skills required in the workplace. The course, which was first introduced in 2016, was designed to combine both university students and professionals who are already at work. The aim is to develop their professional English communication skills but this is not limited to a specific domain as participants may come from a range of backgrounds. This means that the skills to be developed are general skills, which can be applied across a range of fields, and can be considered under the umbrella term of EPP, rather than domain-specific competences and skills. Professionals in today’s world of work are likely to communicate with people from a wide range of linguacultural contexts: for this reason, our teaching approach is informed by research carried out on English as Business Lingua Franca (BELF), which emphasizes the importance of “[getting] the job done” and of establishing rapport rather than of grammatical accuracy (Kankaanranta et al. 2015, p. 130). According to Louihiala-Salminen and Kankaanranta’s Global Communicative Competence model (GCC) (2011), the three crucial aspects of successful international business communication are a) multicultural awareness, which involves the skills to engage in successful interactions with partners from different cultures, b) BELF competence, which includes linguistic and strategic competence, and c) business know-how, that is, “field-specific professional competence (2011, p. 259).

Developing a course such as this involves the design of an appropriate framework for learning, which caters for the differing needs and learning strategies of the participants. The choice of delivery, as mentioned above, is the BL approach which provides greater flexibility, in particular, for those who are at work but also for those with differing levels of linguistic competence. In our context, resources were made available asynchronously for course participants to access at their convenience (Thomlinson and Whittaker 2013; Walsh 2016). Online work was constantly recycled and reintegrated in the f2f work context (the classroom or by means of video-conferencing as a result of the COVID-19 emergency). The f2f sessions were a channel that facilitated activities involving interaction and discussion, whereas the asynchronous channel was essential for independent study and enabled participant choice of pace, timetable, rhythm and level. This is particularly beneficial for learners of differing strengths and weaknesses. A blended approach like this necessarily involves multimodal and multimedia teaching strategies which will be discussed in greater depth below.

The second key component of course design is an appropriate syllabus which will meet the desired outcomes of the course. The lack of principled pedagogical frameworks for ESP, and therefore for EPP, is a hotly debated issue in the English Language Teaching (ELT) world (Ennis and Mikel Petrie 2020; Littlewood 2014). The methodology adopted for ESP has traditionally reflected the methodology of General English with additional work on field related lexis. Littlewood posits the notion that this may stem from practitioners’ lack of awareness of the need for a specific framework. In fact, he advocates a teaching framework as a “communicative continuum” (2014, p. 287). This ranges from analytical learning, which involves non-communicative activities such as the study and analysis of new language forms, phrases or new content, to experiential learning or the practice of new skills and authentic communication. A framework such as Littlewood’s continuum caters for a range of methods including a focus on skills development within a communicative approach and this dovetails very well with the asynchronous and synchronous work done within a blended learning approach like ours. In our context analytical study is provided asynchronously, as mentioned above, and synchronously. The analytical goes alongside the experiential work which is largely task-based, informed by Ellis’ approach (2011).

The EPP programme for our course aims to develop a practical English language competence for specific professional contexts and events in international settings but, in fact, goes beyond this to include multimodal literacy and competences. Professional communication includes both the language skills and the awareness of how to create meanings effectively in various modes, so that, for instance, an employee will be aware not only of the appropriate language choices to make when writing a report but also such factors as appropriate choice of font, layout, colour and images, as will be explored below.

3 Multimodal literacy and multimodal competence

The ability to use English practically and effectively in the workplace includes, as has already been mentioned, multiple skill types: English language skills, strategic skills, multicultural awareness, business know-how, but also multimodal literacy and skills, which inform all the aforementioned aspects. Multimodal literacy means being conversant with the different modes used to create texts rather than simply being consumers of such texts. An effective multimodal reading of social networks, for instance, implies an awareness of how visual images (still and moving) and spoken/written language are used, as well as an awareness of layout and space and the impact that both language and image may have on the audience (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006).

Multimodal texts typically combine two or more modes such as verbal (spoken and written language), visual (still and moving images), audio, gestural, and spatial (Cope and Kalantzis 2009; New London Group 2000). Such texts, furthermore, are increasingly created by digital means such as professional reports produced by word processing software or live performances which avail themselves of digital support resources like PowerPoint or chat feeds available in video-conferencing tools. The ability to apply multimodal communication skills when writing or communicating orally involves not only an appropriate knowledge of the subject or field of the text, but also the textual knowledge of how to best convey meaning through the chosen text. This consists partly of the language aspect but increasingly requires knowledge of the technology and the use of other semiotic processes. In this way, the communication becomes multimodal and, in an effective professional text whether spoken or written, each mode has its own specific task and function (Kress 2010, p. 28) in the meaning making process. Being multimodally literate, therefore, is the first step for those who wish to then develop their own multimodal competence and create their own texts. In the context of EWW, where learners work on such content as developing their CVs, the awareness of appropriate colours, fonts, layout, spacing and organisation of different sections may have a significant effect on the impression created on the reader. Oral communication itself is multimodal, involving, in addition to the verbal mode, prosodic elements (speed, pitch, chunking, intonation), as well as non-verbal (facial expressions, gestures) and spatial (proxemics) aspects, whose delicate interplay is crucial to successful communication, including in intercultural contexts (e.g. Karpiński and Klessa 2018; Yang 2016). For example, giving a professional presentation, which is a key skill both for work meetings and conferences, requires an awareness of such factors as those mentioned above, as well as knowledge of the ICT tools such as PowerPoint that can be used effectively as a visual aid. These are all areas for study and experimentation, and concrete examples of how necessary such work is can be seen in the example of our learners’ multimodal competence in carrying out written and spoken tasks throughout the course.

In the next stage of this discussion, two specific cases which focus on developing multimodality are considered. The first is the case of writing a professional report and the second one focuses on oral intercultural communication.

4 Case 1: developing multimodal competence in professional report writing

Working within Littlewood’s (2014) above-mentioned analytical-experiential continuum, multimodal competence in report writing is developed firstly by means of the analysis and deconstruction of genre specific writing, an approach that is widely adopted in ESP (Bhatia 1991; Hyland 2018). Secondly, learners reconstruct the writing jointly and, finally, independently in a task-based approach. Querol-Julián and Fortanet-Gómez’s approach (2019) to the teaching of multimodal spoken academic genres, developed to cater for a lack of such a framework for spoken communication, followed a similar structure and was a learner-centred approach, which enabled learners to move towards independence in a specific genre as advocated by Hyland (2007), p. 161 (cited in Querol-Julián and Fortanet-Gómez 2019, p. 64). Our approach was also informed by the Teaching and Learning Cycle (TLC) originally developed to advance students’ reading and writing skills at schools (Chandler et al. 2010; Zammit 2015). It, however, provided a useful framework, which we adapted by highlighting the learner-centred aspect of learners moving towards the final task of producing texts in the specific genre in question. In this case the focus is primarily on the analysis of professional, written reports and the four stages can be seen in Table 1.

Four stages in the pedagogical model.

| 1) Building the context or field | Participants, working in groups, consider the context and audience related to the text and features such as content and content organisation in professional reports. |

| 2) Modelling the text (or deconstruction) |

|

| 3) Guided practice (or joint construction) | Participants work in groups to create their own shared texts, receiving continual feedback both from peers and teachers. This is followed by revision and editing. |

| 4) Independent construction | At this stage learners are able to create their own texts autonomously. |

4.1 Visual literacy

[4]Linguistic features typical of writing in ESP are commonly explored and analysed in genre-based ESP approaches (Bhatia 1991; Hyland 2018) whereas the visual is not usually taken into consideration. The visual literacy developed in stage 2 of the framework outlined above, however, focuses also on five key areas of those referred to in the TLC, which are most appropriate to the target texts of this professional course. Informed primarily by Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) and their grammar of visual design, as can be seen in Table 2, these areas involve the study of the five different visual elements.

Key visual elements in professional reports.

| 1. Symbols and logos | Images and logos used in professional reports. |

| 2. Lines and vectors, size and space | Line shape, curved or straight, that leads the eye in a certain direction. The study how the size of various elements on a page, may impact the audience. |

| 3. Size and spaces | The analysis of how space is used and the importance of the size of objects, images and text blocks. |

| 4. Colours and font choice | The choice of colours, as well as their emotional, socio-economic and cultural significance: hue, brightness and saturation in image production and the effects these may create. The study of the possible choice of fonts. |

| 5. Composition and the structure of the text | Placing of different visual elements for salience and to reflect the reading path: the reading path of the eye and how this is determined according to cultural norms. |

4.2 Example of a multimodal-professional report

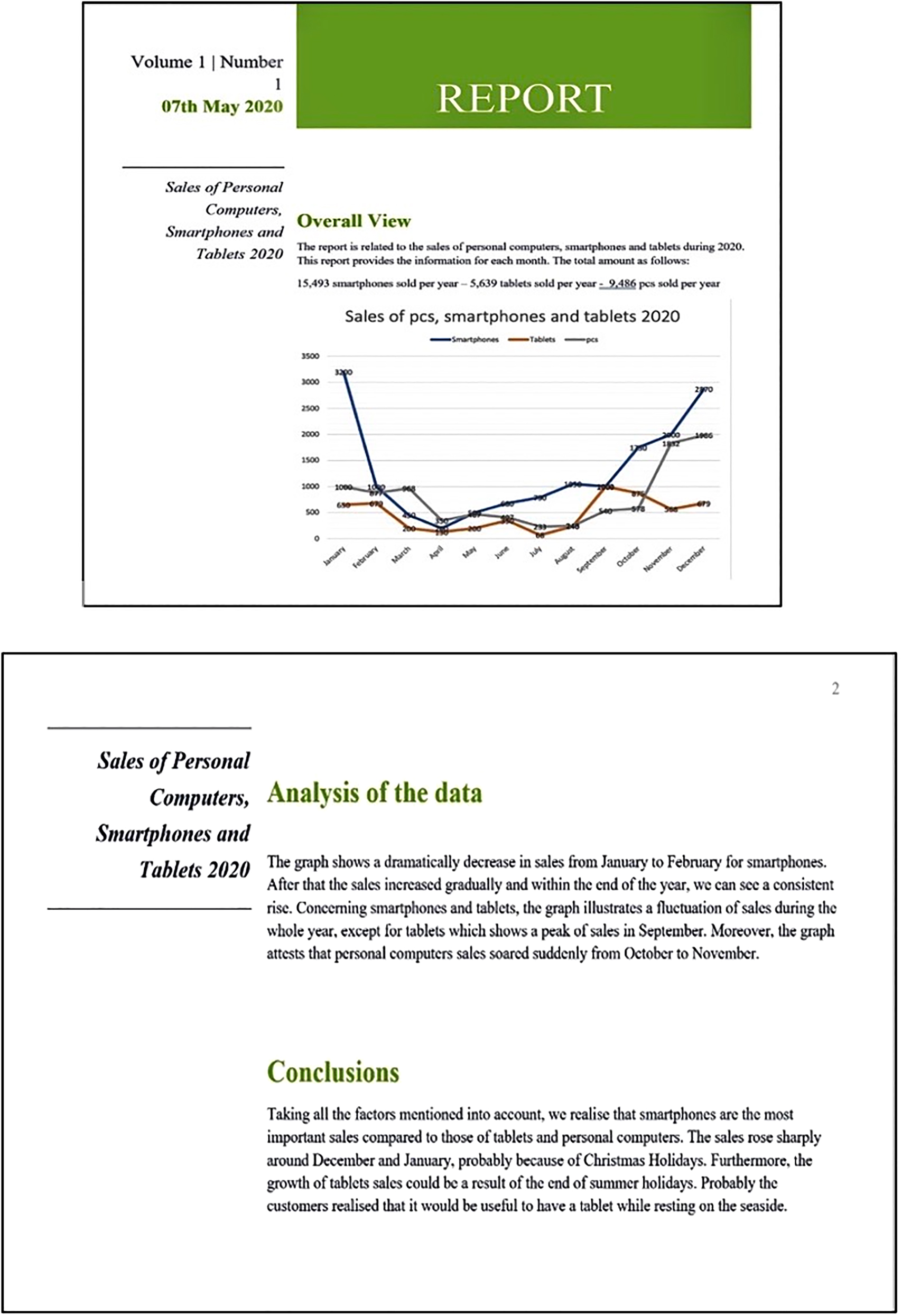

The analysis stage, which aims to develop literacy, is followed by an experiential, task-based stage which fosters competence, where multimodal elements combine harmoniously into a semiotically complex exchange. The final stage of the TLC is independent construction and, in this paragraph, we consider one concrete example: the production of a professional report. Course participants need primarily to develop an awareness of suitable language choices, register and text organisation skills but, at the same time, they also need to know how to organise their content visually. To achieve this aim, they begin by considering various example reports which are successful to a greater or lesser extent and discuss why this is so. Gradually, issues such as headings, fonts, spacing, colour, graphs etc. are introduced and discussed, along with language areas such as the lexis and phraseology used to describe graphs, or cohesion and coherence in writing (Halliday and Hasan 1976). Finally, the participants produce their own reports and submit them, revising them after feedback to create a final effective version. One example of such a multimodal report can be seen in Figure 1.

An example of a multimodal professional report produced during the 2020 course.

This report is an attempt to use multimodal features in the task for this part of the course, which was to produce a short report as a guided writing exercise based on a graph and notes, provided in advance. The headings and title, in this example, were written in green and the graph lines in blue, grey and orange. One heading was initially black and then became blue, which is perhaps not so effective but, the homogeneity of the colour green, used for the main heading and subheadings creates harmony throughout the report. The choice of layout with the main heading on the left is an interesting idea, but it does not work completely because it may be confused with the sub-headings. The spacing also needs work as does the size of the heading itself. The use of Times New Roman for the main text, but not in the graph itself, may also be distracting for the eye. The fact, however, that the graph has been included is appropriate and helpful for the reader. The addition of volume and number is also not appropriate for a short report of this type, intended for internal use in a specific company. As far as the lexis is concerned, there are instances of effective language use particularly when describing the sales, such as the phrase “illustrates a fluctuation” or “The report shows a dramatically decrease in sales”. When looking at the chart, it is clear that the decrease was dramatic, and even though in the written description there is the grammatical error of the inappropriate adverbial form “dramatically” instead of the adjectival one “dramatic”, the message is, in any case, clear. The content lacks cohesion in the overview, where “report” is repeated unnecessarily, but the second and third paragraphs evidence a more frequent use of cohesive language.

Overall, although this text is not completely successful multimodally, it is a good attempt and illustrates by its very shortcomings the need to work on developing multimodal literacy and competence.

5 Case 2: developing multimodal competence in intercultural communication

The issue of cultural differences in the workplace has come to the forefront of business communication as companies increasingly expand their activities beyond the national borders. As suggested in section, 2, multicultural awareness – alongside BELF competence and business know-how – is paramount to successful international business interactions (Louhiala-Salminen and Kankaanranta 2011), as cultural differences can influence or hinder successful workplace interactions. Effective users should therefore show competent use of interpersonal and intercultural skills as well as linguistic ones. Care with the appropriateness of register and the use of politeness, knowledge of how to fine-tune such language choices, and competent use of Communication Strategies (CSs) have the same importance for effective communication in today’s global workplace, especially when intercultural factors are taken into consideration. In addition to the verbal modes, intercultural communication involves multiple other semiotic modes, including spatial and gestural ones. Examples of these are prosody and nonverbal language, proxemics, physical contact, culturally-loaded gestures and emblems, as well as other social behaviors (business etiquette) (e.g. Birlik and Kaur 2020; Okoro 2013; Palmer-Silveira 2019). For this reason, a multimodal look at interculturality is paramount in courses focused on workplace English (Zheng 2018).

In EWW, all these aspects and modes are discussed multiple times throughout the course, but they are explicitly examined from an intercultural perspective in a dedicated module, described in the following subsections.

5.1 Multiple semiotic modes in EWW: building multicultural awareness and competence in BELF

The module on intercultural communication makes broad use of scaffolding, as it encourages learners to think about what they have acquired in the previous modules, such as: moving linguistically between a formal and informal register, using politeness appropriately, and keeping an open mind when communicating with other international speakers, including showing a flexible mindset towards accent variability in international communication.

Active or attentive listening, for example, is an important skill that fosters a collaborative attitude and contributes to facilitating comprehension and workplace performance, involving the ability “to ask for clarifications, make questions, repeat utterances, and paraphrase” (Kankaanranta and Louhiala-Salminen 2013, p. 28), and to use non-verbal signals such as backchannelling and nodding (Birlik and Kaur 2020). Being able to listen actively and to adopt a collaborative attitude can also clue users in as to comprehension issues, leading to pre-emptive – or reparative – action when comprehension issues occur or are suspected.

Other aspects of non-verbal language, such as posture and proxemics, are also recycled in this module and looked at more in detail from an intercultural perspective. For successful international communicators, it is important to learn how to choose the tools available to them in a variety of contexts, in order to ensure that mutual understanding is reached and the communicative goal of the interaction is effectively achieved. In this module, students learn how to look at familiar verbal and non-verbal modes from an intercultural perspective and do so multimodally, with visual, verbal, prosodic, gestural and spatial modes “combined to produce meaning, encourage interaction and learning in the classroom” (Marchetti and Cullen 2016, p. 39). Employing multimodal materials in instruction can in turn lead students to increase their own multimodal competence, as “multimodal pedagogy can help language students learn to exploit semiotic modes beyond the verbal message […] [a]nd to both understand and produce texts in the target language more effectively, while also enhancing their awareness of the target culture, particularly in relation to differences in non-verbal communication styles” (Laadem and Mallahi 2019, p. 36).

The development of the TLC in this module is detailed in Table 3 below.

Multimodal focus for intercultural communication in the TLC framework.

| Building the context or field | In previous modules, students are asked to reflect on the role of non-verbal language in workplace communication in general. Students are introduced to communication strategies (CSs) as “emergency phrases” and learn about register and politeness strategies. |

| Modelling the text (or deconstruction) | Students are shown visual examples of unsuccessful intercultural business communication and are invited to discuss the issues shown in groups. The different aspects of non-verbal communication are then described and the other two aspects of the GCC model are introduced. CSs, register and politeness are defined as verbal elements of intercultural communication, and students listen to an oral conversation where they have to recognize how CSs are used to ensure comprehension is attained. |

| Guided practice (or joint construction) | In groups and pairs, students perform two semi-guided activities: in a ‘debate club’ activity, students use politeness strategies to express agreement and disagreement on a topic of discussion, and in a telephone conversation role-play students have to use CSs to ensure that both parties have the correct information related to the business transaction. |

| Independent construction | Students participate in an intercultural communication simulation in which non-verbal cues signalling social and power dynamics have a prominent role, and they need to accommodate to a different way of communicating in order to sign a business deal that is satisfactory to both parties. |

To summarize the above framework, starting by recycling and building upon competences already acquired in previous modules, students learn how the different elements come into play and interact in intercultural communication. After focusing on individual aspects in two semi-guided activities, they are encouraged to employ all the different aspects and modes of intercultural communication in the final activity.

We conclude this case by reporting on an additional reflection activity that the students were engaged in during the latest edition of the course. Participants were asked to consider how mask-wearing and videoconference meetings have changed the way people communicate interculturally as a result of the sars-cov-19 pandemic. Student responses showed an increased awareness of the role that different semiotic modes play in oral interaction in intercultural professional contexts, and how changes in how such meetings are carried out affect them – positively or negatively.

Some participants suggested that videoconference calls can make intercultural communication easier as they eliminate the spatial dimension and therefore can avert any faux pas pertaining to interpersonal distance and physical contact, as in examples 1 and 2 below.

I had a few video conferences with people from a lot of different parts of the world and it seemed to me that people were more at ease than usual. Proxemics is eliminated and with it all the problems, worries about interpersonal distance […].

[…] it is clear that other cultural behaviours are no more taken into account. […] it is forbidden to shake hands […] as well as it is forbidden to greet someone with a hug in an ordinary context.

Other participants, on the other hand, highlighted increased difficulty caused by masks in f2f contexts (lack of facial expressions, lip reading) or due to interacting via a screen (turn-taking).

[…] people’s expressions allow the speaker to receive a non-verbal feedback, but because of masks they are not visible […] some gestures can: the listeners, for example, could help the speaker by nodding their head if they have understood what has been said.

I think the main issue is that wearing a mask hides half the face and blocks all those facial expressions that are essential in communicating. It’s also simply more difficult to hear one another, lips reading might not seem important but without even realising it we rely on them all the time to help us understand what’s being said […].

For example, I think turn-taking can be particularly challenging in intercultural communication, because it can be somehow an expression of power […].

While these comments focus on the current situation, they strongly suggest that participants have increased their awareness of the interplay between different modes in intercultural communication, recognizing their function and how they – or lack thereof – may affect the outcome of professional interactions.

6 Conclusions

The interconnection between linguistic skills, multimodal literacy and business know-how is crucial for anyone who aims to be successful in today’s world of work at an international level. The learner-centred EWW course illustrated in our contribution focuses specifically on such interconnection and, through multimodal pedagogy, contributes to the development of multimodal literacy and competence. Each participant builds on his/her own initial competence from different perspectives, first and foremost thanks to the BL approach; indeed, learners can choose their own pace, timetable and rhythm in the online context whilst interacting in a more direct way with teacher and peers in the f2f context, and the TLC provides a blend of analytical and experiential tasks.

Although the case study has provided promising feedback from participants, suggesting a growing awareness of the importance of multimodal factors in writing and speaking, it is limited to our specific context. Future research could focus on extending the implementation of the approach and measuring effective multimodal strategies quantitatively, which would, in turn, provide a more robust justification for the framework and delivery methods adopted. The variety of experiential activities, in any case, offered in the course modules and drawn from different cultural environments allows the course participants to develop multicultural awareness as well wide-reaching communicative skills involving register variation and degree of politeness. Hence, they shift gradually from an initial receptive mindset to an increasingly active attitude, both in oral and in written language.

As EWW has indeed proved, being conversant with the variety of modes used to create texts is a key skill that enables learners to produce and spoken texts for professional purposes more effectively. Being able to detect and decode the different cultural factors lying behind spoken utterances and written texts is also becoming increasingly essential to forge meaningful relationships with business partners and clients. Feeling confident when using such strategies and being able to adapt to different situations are markers of expertise that empower professionals in our demanding world. Communication in our times, in fact, is constantly changing the range of semiotic choices available to us. For this reason, being able to make effective choices on various levels is a key skill which can be overtly taught to aid those who wish to communicate effectively.

References

Atanga, M., Abgor, N., and Ayangwo, J. (2015). Criticisms of the “lecture” method in the teaching of nursing students: the case of nurse tutors in Bamenda, Cameroon. Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 6: 397–403, https://doi.org/10.9734/bjmmr/2015/13223.Suche in Google Scholar

Hartle. (2018). The quality lies in the blend: a digital, task based approach to professional English. LEND Riv. Lingua Nuova Didattica 2: 1–12.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, T. (2016). Are you ready for blended learning?, online learning and distance education resources, Available at: https://www.tonybates.ca/2016/12/12/are-we-ready-for-blended-learning/ (Accessed 08 September 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, V. (1991). A genre-based approach to ESP materials. World Englishes 10: 153–156, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971x.1991.tb00148.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Birlik, S. and Kaur, J. (2020). BELF expert users: making understanding visible in internal BELF meetings through the use of nonverbal communication strategies. Engl. Specif. Purp. 58: 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Cambridge English Language Assessment and (QS), Q. S. (2016). English at Work: global analysis of language skills in the workplace, (November), Available at: http://englishatwork.cambridgeenglish.org/ (Accessed 08 September 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Chandler, P., O’Brien, A., and Unsworth, L. (2010). Towards a 3D digital multimodal curriculum for the upper primary school. Aust. Educ. Comput. 25: 34–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Cope, B. and Kalantzis, M. (2009). A grammar of multimodality. Int. J. Learn. 16: 361–426.10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i02/46137Suche in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. (2001). The common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Council of Europe.Suche in Google Scholar

De Los Santos, S.B., Kupczynski, L., and Bain, S.F. (2016). The lecture mehod is D-E-A-D. Focus Coll. Univ. Sch. 10: 1–7, https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.v0i10.10.Suche in Google Scholar

Driscoll, M. (2002). Blended learning: let’s get beyond the hype. E-Learning 3: 54.Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, R. (2011). Macro- and micro-evaluations of task-based teaching. In: Tomlinson, B. (Ed.), Materials development in language teaching, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 4210–4694.10.1017/9781139042789.012Suche in Google Scholar

Ennis, M. and Mikel Petrie, G. (2020). A response to disparate/desperate circumstances. In: Ennis, M. and Mikel Petrie, G. (Eds.). Teaching English for tourism: bridging research and praxis. Routledge, London & New York, pp. 1–6.10.4324/9780429032141-101Suche in Google Scholar

Friesen, N. (2012). Defining blended learning, learning spaces, Available at: https://www.normfriesen.info/papers/Defining_Blended_Learning_NF.pdf (Accessed 08 September 2019).Suche in Google Scholar

Group, T. N. L. (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies designing social futures. In: Cope, B. and Kalantzis, M. (Eds.), Multiliteracies: literacy learning and the design of social futures. Routledge, London, pp. 9–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, M.A.K. and Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English. Longman, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. J. Sec Lang. Writ. 16: 148–164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. (2018). Genre and second language writing. In: Liontas, J., Anderson, N., Belcher, D., and Hirvela, A. (Eds.). The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching. John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken, pp. 2359–2364.10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0535Suche in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. and Hamp-Lyons, L. (2002). EAP: issues and directions. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 1: 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1475-1585(02)00002-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, literacy, learning. A multimodal approach. Routledge, London and New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Jewitt, C. (2009). In: Jewitt, C. (Ed.). The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. Routledge, London & New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Jewitt, C. (2013). Multimodal methods for researching digital technologies. In: Jewitt, C. and Brown, B. (Eds.). The SAGE handbook of digital technology research. Sage, London, pp. 250–265.10.4135/9781446282229.n18Suche in Google Scholar

Kankaanranta, A. and Louhiala-Salminen, L. (2013). What language does global business speak? – The concept and development of BELF. Ibérica 16: 17–34.Suche in Google Scholar

Kankaanranta, A., Louhiala-Salminen, L., and Karhunen, P. (2015). English in multinational companies: implications for teaching ‘English’ at an international business school. J. Engl. as a Lingua Franca 4: 125 – 148, https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2015-0010.Suche in Google Scholar

Karpiński, M. and Klessa, K. (2018). Methods, tools and techniques for multimodal analysis of accommodation in intercultural communication. Comput. Methods Sci. Technol. 24: 29–41.10.12921/cmst.2018.0000006Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication, multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, London & New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. Bloomsbury Academic, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: the grammar of visual design, 2nd ed. Routledge, London & New York.10.4324/9780203619728Suche in Google Scholar

Laadem, M. and Mallahi, H. (2019). Multimodal pedagogies in teaching English for specific purposes in higher education: perceptions, challenges and strategies. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 1: 33–38.10.46328/ijonse.3Suche in Google Scholar

Laughlin, P.R., Hatch, E., Silver, J., and Boh, L. (2006). Groups perform better than the best individuals on letters-to-numbers problems: effects of group size. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90: 644–651, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.644.Suche in Google Scholar

Littlewood, W. (2014). Methodology for teaching ESP. In: Bhatia, V. and Bremner, S. (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of language and professional communication. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 287–303.10.4324/9781315851686.ch19Suche in Google Scholar

Louhiala-Salminen, L. and Kankaanranta, A. (2011). Professional communication in a global business context: the notion of global communicative competence. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. Spec. Issue Prof. Commun. Global Contexts 54: 244–262, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpc.2011.2161844.Suche in Google Scholar

Marchetti, L. and Cullen, P. (2016). A multimodal approach in the classroom for creative learning and teaching. CASALC Rev. 2: 39–51.Suche in Google Scholar

Okoro, E. (2013). Negotiating with global managers and entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa – Nigeria: an analysis of nonverbal behavior in intercultural business communication. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 3: 239–250, https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v3-i8/140.Suche in Google Scholar

Palmer-Silveira, J.-C. (2019). Introducing business presentations to non-native speakers of English: communication strategies and intercultural awareness. Iperstoria 13: 47–58.Suche in Google Scholar

Picciano, A.G. (2009). Blending with purpose: the multimodal model. J. Async. Learn. Network 13: 7–18.10.24059/olj.v13i1.1673Suche in Google Scholar

Querol-Julián, M. and Fortanet-Gómez, I. (2019). Collaborative teaching and learning of interactive multimodal spoken academic genres for doctoral students. Int. J. Engl. Stud. 19: 61–82.10.6018/ijes.348911Suche in Google Scholar

Sharma, P. and Barrett, B. (2007). Blended learning using technology in and beyond the language classroom. Macmillan, Oxford.Suche in Google Scholar

Slaouti, D. (2002). The world wide web for academic purposes: old study skills for new? Engl. Specif. Purp. 21: 105–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-4906(00)00035-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Tomlinson, B. and Whittaker, C. (2013). In: Tomlinson, B. and Whittaker, C. (Eds.). Blended learning in English language teaching: course design and implementation. British Council, London.Suche in Google Scholar

Walsh, S. (2016). The role of interaction in a blended learning context. In: McCarthy, M. (Ed.). The Cambridge guide to blended learning for language teaching. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 36–52.10.1017/9781009024754.005Suche in Google Scholar

Wang Guénier, A.D. (2020). A multimodal course design for intercultural business communication. J. Teach. Int. Bus. 31: 214–237, https://doi.org/10.1080/08975930.2020.1831422.Suche in Google Scholar

Warschauer, M. (2002). Networking into academic discourse. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 1: 45–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1475-1585(02)00005-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, M.-Y. (2016). Achieving multimodal cohesion during intercultural conversations. Int. J. Soc. Cult. Lang. 4: 56–70.Suche in Google Scholar

Zammit, K. (2015). Extending students’ semiotic understandings: learning about and creating multimodal texts. In: Trionfas, P. (Ed.). International handbook of semiotics. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1291–1308.10.1007/978-94-017-9404-6_62Suche in Google Scholar

Zheng, X. (2018). Research on business English listening and speaking based on multimodal discourse theory. Theor. Pract. Lang. Stud. 8: 1748–1752, https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0812.23.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Towards developing multimodal literacies in the ESP classroom: methodological insights and practical applications

- Teaching communication strategies for the workplace: a multimodal framework

- Enhancing multimodal communicative competence in ESP: the case of job interviews

- Developing strategies for conceptual accessibility through multimodal literacy in the English for tourism classroom

- Engaging students in multimodal literacy practices in a university ESP context: towards understanding identity and ideology in government debates

- Growing theory for practice: empirical multimodality beyond the case study

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Towards developing multimodal literacies in the ESP classroom: methodological insights and practical applications

- Teaching communication strategies for the workplace: a multimodal framework

- Enhancing multimodal communicative competence in ESP: the case of job interviews

- Developing strategies for conceptual accessibility through multimodal literacy in the English for tourism classroom

- Engaging students in multimodal literacy practices in a university ESP context: towards understanding identity and ideology in government debates

- Growing theory for practice: empirical multimodality beyond the case study