Abstract

Teaching English for Tourism at university involves both developing specialized language skills and forming knowledgeable professionals capable of appropriate intercultural communication. The distinctive feature of most instances of tourism discourse is the fact that it draws from a range of specialized domains. It mediates the tourist experience and contributes to closing the gap between the home- and the destination’s culture by making culture-specific knowledge and specialized concepts accessible to non-specialists. The article discusses the instructional effects of authentic multimodal materials within task-based project-work carried out with learners at the University of Pisa. The focus is specifically on the communicative strategies used to make specialized terminology or concepts easily understandable for the hearer. This study reports on a multimodal analysis of two sets of videoclips created by the students before and after dedicated instruction based on authentic English L1 clips from documentaries, “docu-tours” and guided tours. It discusses the positive changes observed in the learners’ use of popularization strategies to create conceptual accessibility.

1 Introduction

Teaching English for Tourism (EfT) at the university level necessarily involves developing both specialized lexico-grammatical skills and forming knowledgeable professionals capable of appropriate and effective intercultural communication. Tourism discourse encompasses a wide range of communicative contexts, ranging from specialist-to-specialist interaction (e.g., corporate communication) to “layman-to-layman” exchanges (e.g., user-generated contents).

Undergraduate EfT learners are usually trained to manage instances of expert-to-non-expert tourism communication, which often have a hybrid generic and semantic nature (Gotti 2006). As future practitioners, their job will likely be to mediate between cultures. For this reason, they must be aware of the role played by different semiotic resources in making culture-specific knowledge and specialized concepts easily understandable (i.e., accessible) for the general public (Cappelli 2016; Cappelli and Bonsignori 2019; Cappelli and Masi 2019).

This article builds on the authors’ previous research on the features of English L1 documentaries, guided tours, and docu-tours (Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020). It draws from the study of the strategies observed in these genres to enhance conceptual accessibility when potentially obscure concepts are involved, as well as from the investigation of the effects of incorporating selected examples of authentic multimodal materials in professionalizing task-based activities for the ESP classroom (Cappelli and Bonsignori 2019; Ellis 2018; Hafner and Miller 2019).

We discuss the changes observed in the verbal and non-verbal resources used in short videos produced by EfT learners as part of a classroom project which involved the recording of two docu-tours (i.e., virtual video tours, a hybrid genre mixing features of documentaries and guided tours) on one and the same attraction. A video was recorded prior to dedicated instruction and the other at the end of the course. The analysis carried out on these learner-generated materials replicated the investigation conducted on English L1 docu-tours. The purpose was to identify the multimodal strategies used to help real or potential tourists make sense of possibly unfamiliar concepts. The learners’ progress is then discussed in terms of the ability to use different resources to this end through a qualitative analysis of the two sets of videos. Finally, we compare their strategies to those used in authentic L1 docu-tours (Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020) and draw some conclusions as to the potential of multimodal EfT pedagogy for both linguistic and professional development.

2 English for tourism, multimodality and multimodal pedagogy

Tourism discourse has two major functions: it “selects” what is worth seeing (i.e., leading function) and creates cultural accessibility for travellers (i.e., mediating function) through a range of diverse communicative strategies, both verbal and non-verbal (Dann 1996; Francesconi 2014; Urry 2002). Practitioners in the industry must therefore master the communicative tools necessary to offer cross-cultural representations of destinations, reduce the cultural gap between the tourist’s home culture and the local culture, and promote a process of socialization and enculturation of the traveller (cf. Cohen 1985; Dann 1996; Ap and Wong 2001; Dybiec 2008; Cappelli 2016; Maci 2020, among others). They must be able to create semantic (and cultural) accessibility while disseminating knowledge (Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020).

The term “accessibility” is used here to indicate the measure of the ease with which mental representations and pieces of stored information are retrieved from memory so that relevant aspects of the target culture become understandable (cf. Ariel 2006 and its adaptation in Cappelli 2016 and Cappelli and Masi 2019). In expert-to-non-expert contexts, the language of tourism is often shaped by the need to provide interpretive tools for tourists by creating connections between the “known” and the “new”, so that they can see the importance of the items selected as culturally relevant. This often requires mediating specific concepts that are essential for the understanding of local art, history, geography, language, traditions, etc. through available and more familiar mental representations, which are adapted to create new and more easily processed ones.

As in other specialized domains, conceptual accessibility in tourism discourse is created through the exploitation of popularization strategies (cf. Calsamiglia 2003; Calsamiglia and Van Dijk 2004; Gotti 2006, 2014; Myers 2003), which also contributes to knowledge dissemination. Such strategies are rarely unimodal: various semiotic resources are intertwined and together contribute to meaning-making in a given situational context (cf. Kress and van Leeuwen 1996; Norris 2004; Scollon and Levine 2004; O’Halloran 2004).

In spoken tourism discourse, as in the written genres, multimodal resources play a crucial role in meaning-making (Cappelli 2016; Francesconi 2014; Ignatova 2018; Manca 2016), and the way in which they are used can be considered distinctive features of the different genres. Thus, in guided tours, documentaries and docu-tours, non-verbal cues such as hand gestures, gaze direction, body posture, sounds, and images, greatly contribute to supporting, integrating, and creating meaning when specialized or culture-specific concepts are involved, in different ways in each genre (cf. Cappelli and Masi 2019; Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020). For example, tour guides needing to explain what sandstone means, while describing the building material of most constructions in Edinburgh, may use their hands to mimic layers of stratified rocks. In guided tours, the situational context is shared by all participants and, therefore, the exploitation of multiple semiotic resources is intrinsic to this genre. Both aural and visual elements are used alongside language to convey and fully explain concepts in nonsynchronous communicative events as well, such as documentaries and docu-tours. This shows that no communicative event can be analysed solely by taking into account the verbal component. For this reason, the specific instruction received by EfT learners should not be limited to the linguistic structures and the vocabulary necessary to refer to individual aspects of a destination and its culture. It should also focus on the multiple semiotic resources typically used in authentic materials and interactions and develop the learners’ multimodal communicative competence necessary to ensure cultural accessibility for their audience (Agorni and Spinzi 2019; Royce 2002).

In recent years, the role of multimodality in ESP teaching and research has received growing attention. After having remained marginal until the past decade, it is now widely believed that it should be an essential part of the ESP curriculum (Crawford Camiciottoli 2019; Plastina 2013; Prior 2013). The benefits of integrating multimodal corpora (Ackerley and Coccetta 2007) and multimodal resources in language teaching have been extensively described (Kaiser 2011; Sherman 2003; Webb and Rodgers 2009; cf. Bonsignori 2018; Hafner and Miller 2019 for ESP). The EfT classroom seems the ideal setting to implement multimodal pedagogy to advance both language and professional skills (Kalantzsis and Cope 2013). Project-work-based teaching that involves authentic multimodal materials and the creation of multimodal products can provide a working framework. One of the advantages of such an approach is the fact that it promotes the centrality of the learner by offering opportunities for learning-by-doing (Plastina 2013). The integration of task-based activities in the curriculum favours the learners’ active involvement, autonomy, and motivation (Díaz Ramírez 2014; Ellis 2018; Mamakou 2009; Stoller 2006). In designing the project, the hypothesis was therefore that the pairing of project-work and authentic videoclips can expand the learners’ expertise in their field and turn it into awareness of specific professional communicative practices, while avoiding the limitations of the non-authenticity of the learning task.

3 Strategies to create conceptual accessibility in L1 multimodal spoken tourism genres

To the best of our knowledge, no linguistic studies have specifically focused on multimodal strategies for accessibility in documentaries, docu-tours and guided tours. Travel documentaries have been discussed as a genre by Lopriore (2015). Thurlow and Jaworski (2011: 285) have considered how local languages have been “recontextualized and commodified” in different genres including TV broadcast and guided tours. Guided tours have also been the object of Cohen’s (1985) and Zillinger et al.’s (2012) investigations, although in a sociological, sociolinguistic and widely semiotic perspective. Costa and Ravetto (2018) adopt a discourse analysis approach to the language used by German speaking tour guides to compensate for the asymmetries in knowledge, age and language proficiency between them and the participants in the tours. Cox-Petersen et al. (2003) discuss the reception of guided school tours of a museum of natural history and the ways in which resorting to realia often helped students understand unfamiliar terminology. The exploitation of realia is also at the heart of Fukuda and Burdelski’s (2019) discussion of comprehension processes in sequences of interactions in guided tours at a culture centre and museum. Pierroux (2010) discusses the use of narrative as a semiotic resource in guided tours of art museums for high school students. Recent publications have analysed the reception of virtual tours (El Said and Aziz 2021; Rastati 2020).

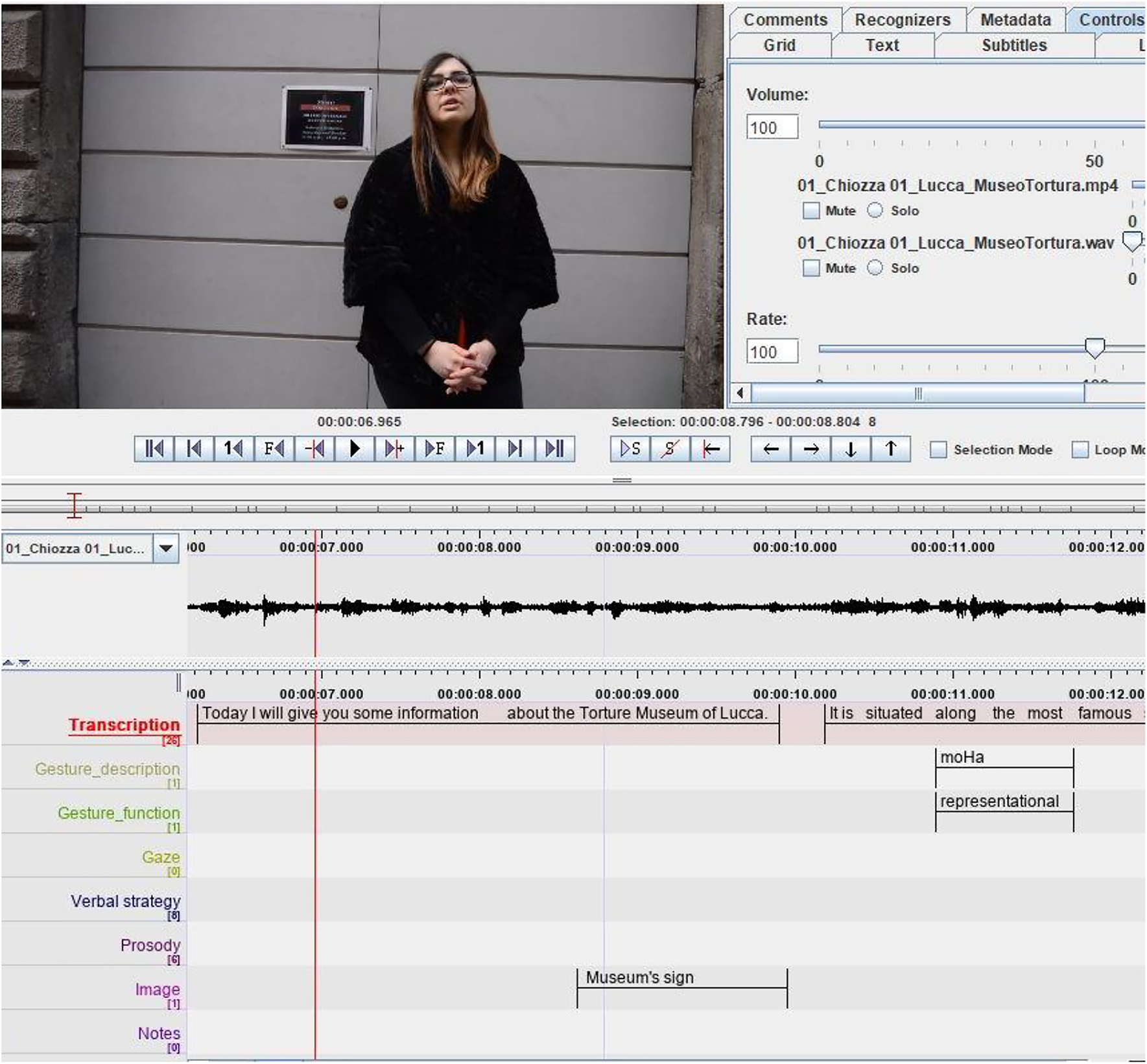

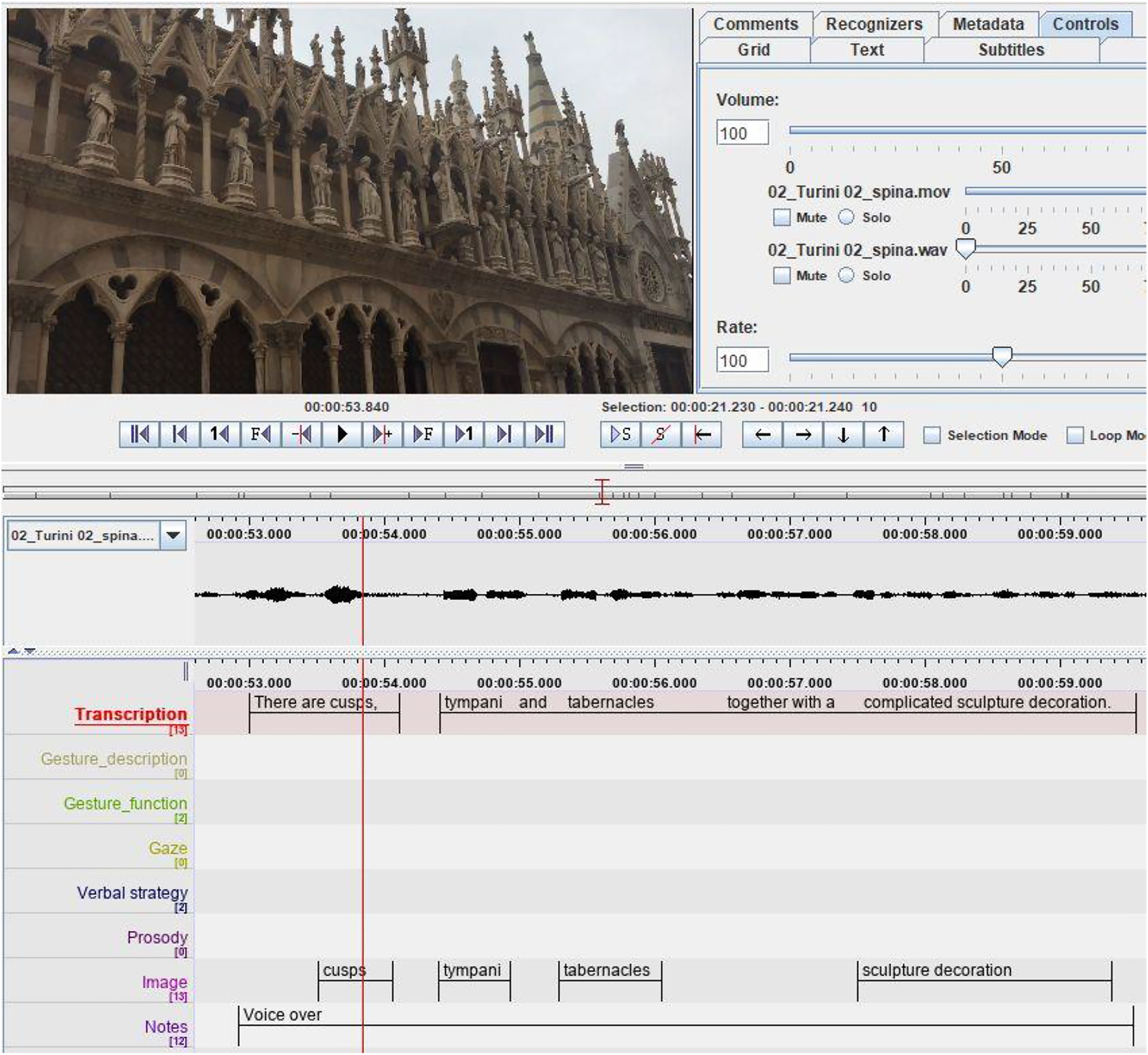

Bonsignori and Cappelli (2020) focus specifically on the way in which specialized terminology and culture-specific concepts are made (more) easily understandable for the audience of documentaries, docu-tours and guided tours. A multimodal English L1 corpus was created, consisting of 34 clips selected and cut from 20 authentic audiovisual documents across the three genres, namely 2 guided tours, 13 docu-tours and 5 documentaries, belonging to different specialised domains (e.g., medicine, business, art and culture, among others).[1] The clips were carefully watched and then transcribed. Firstly, quantitative data were retrieved relative to the instances of specialized or culture-specific terminology or concepts present in the verbal component of the clips. Secondly, the verbal popularization strategies employed for accessibility creation in association with these elements (e.g., explanation, anchoring, attribution; Calsamiglia and Van Dijk 2004) were retrieved and classified through a qualitative analysis. Finally, co-occurring non-verbal cues and strategies employed to ensure meaning accessibility (e.g., gestures, images, graphic aids, labels and sounds) were identified through a multimodal analysis with the annotator software ELAN (ELAN 2020). This holistic description was achieved through the creation of multiple tiers in the software, which can be filled with various analytical information using labels, i.e., “controlled vocabulary”, in their abbreviated and extended form. The system enables the analyst to visualise all the different elements that occur together in the communicative event alongside the video, which is streamed on the upper left side of the ELAN document window (cf. Figure 1 as an example). In this case, the tiers created in the software for this analysis were the following:

Transcription: speech is transcribed in synchronization with the video

Gesture_description: description of gestures using labels broadly based on Querol-Julián’s (2011) adaptation of Kendon (2004) (e.g., ‘Pu’ standing for ‘palm up’)

Gesture_function: description of gesture function which follows a combination of the classifications drawn by Kendon (2004) and Weinberg et al. (2013)

Gaze: description of gaze direction (e.g., ‘LaC’ standing for ‘looking at the camera’)

Verbal strategy: labels that refer to the strategies used for accessibility and popularization purposes (e.g., definition, denomination, etc.)

Prosody: indication of paralinguistic stress

Image: image description

Notes: information on camera angles; especially if the speaker is not on camera and can only be heard in voice-over, this becomes relevant in the analysis and should thus be taken into consideration (cf. Bonsignori 2016).

Multimodal analysis of an extract from clip 1, Student A.

The same analytical framework has been applied to the analysis of the multimodal learner corpus. The case studies illustrated in Section 5 exemplify the methodology used.

Although the size of the multimodal L1 corpus was limited and the distinction made between documentaries and “docu-tours” (i.e., the type of genre learners were asked to produce) was somewhat arbitrary, due to the fuzzy boundaries between some instances of the two genres (cf. Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020), the observations that could be made seemed to unveil some distinctive characteristics of the three different genres. The verbal and non-verbal strategies investigated show different distribution patterns across genres, which point to a possible continuum with respect to the features investigated.

Overall, non-verbal strategies were more commonly used than verbal strategies. Verbal strategies are preferred in guided tours, whereas their prominence progressively decreases in the two audiovisual genres. This was expected because, as Lopriore (2015: 221) states, in documentaries “the spoken text has to back up visuals rather than overpower them” and narration should be “kept as simple and as clear as possible to allow images to speak”. Moreover, documentaries are planned, scripted and edited and therefore the authors can pair non-verbal elements and terminology in an effective way to ensure maximum explanatory power. The same tendency was observed in docu-tours, where, however, non-verbal strategies often overlap with verbal strategies. Thus, in a style that is similar to that of guided tours, the speaker offers a verbal explanation of unfamiliar concepts while, at the same time, images (static or in the form of short narrative videos) echo his or her words as in a “canonical” documentary. Finally, in guided tours, although non-verbal strategies still looked preponderant, it was actually the verbal component that played the major role in creating accessibility, as the only non-verbal resource available to tour leaders is usually gestures.

Images were almost equally common in documentaries and docu-tours, while labels, graphic aids (e.g., arrows and animations) and sound effects were only found in the former, as they are typically added in the editing phase. The hybrid nature of docu-tours is again evidenced by the fact that, besides resorting to visual resources like documentaries, gestures are also typically used by the speakers on camera to enhance understanding, just as tour guides do in “real life” situations.

The use of verbal strategies also reflected the scripted versus non-scripted continuum along which the three genres can be ideally placed. Overall, the most common verbal strategies are description and definition (35%), followed by denomination (22%), exemplification (17%), paraphrase (16%) and anchoring (10%). All the strategies identified were found in guided tours and docu-tours, whereas only those which reveal proper planning (e.g., description, definition, exemplification) were retrieved in documentaries. Paraphrase was mostly found in the form of rephrasing, which is more typical of spontaneous spoken communication than planned written language. It is therefore not surprising that it is quite common in guided tours. Its frequency in docu-tours was instead unexpected, and the same holds for exemplification. This led to the conclusion that docu-tours can be seen as a hybrid genre, where accessibility is achieved through the sometimes redundant overlap of multiple verbal and non-verbal strategies. This is probably due to the fact that, contrary to what happens in documentaries, the verbal component precedes the visual component (Lopriore 2015), and thus docu-tours preserve some of the characteristics of the more spontaneous nature of guided tours.

4 Multimodal learner docu-tour corpus: participants and methods

The learner multimodal corpus includes a total of 98 videoclips (02:58:00, 20,897 words) produced by 49 second-year Italian-speaking students of Tourism Sciences (B1 low intermediate CEFR level). The corpus is made up of two versions of the same videoclips about an attraction in either Pisa or Lucca, which the participants recorded before (Clip 1) and after dedicated instruction (Clip 2) in the style of a “docu-tour”.

The instruction phase consisted in a series of lessons centred around the 34 short clips from our previous research described in Section 3. They were shown to students in class to increase exposure to the target language and provide models for professional skill development. Specifically designed awareness-raising activities were created which focused on the generic and linguistic features of these spoken tourism genres. For example, students were provided with the transcript of a docu-tour clip where some specialized terms (e.g., bowels, specimen, ignites) had been underlined. They were asked to guess the meaning and when they could not, they were prompted to watch the clip again while paying close attention to co-occurring images or gestures. We then verified if they had figured out the meaning of the new word and discussed the role played by visuals in this process. The operational tripartite classification (i.e., guided tour, docu-tour and documentary) proposed was based on the preliminary observations discussed above.

A quantitative and qualitative analysis was carried out on the two sets of clips following the same methodology adopted for L1 docu-tours discussed in Section 3 (Bonsignori and Cappelli 2020). Thus, after having identified specialised lexical items or culture-specific concepts, the associated verbal and non-verbal strategies used to help the audience understand their meanings were retrieved. The data obtained from the analysis of clip 1 and 2 were compared. The aim was to see if the instruction phase had led to a change in the learners’ communicative behaviour when it comes to contexts that may be obscure for the intended audience. Lastly, the data from the analyses of the multimodal learner corpus were compared to those from the multimodal L1 corpus to investigate similarities and differences between L1 and L2 accessibility strategies before and after instruction. The goal was to verify whether the activities proposed resulted in more native-like linguistic and communicative performance.

5 Multimodal learner corpus: analysis

This section illustrates two case studies that exemplify the multimodal analysis of the clips created by the students.[2]

5.1 Case study 1: Torture Museum, Lucca

The first two clips were shot by Student A at the Torture Museum in Lucca. Clip 1 (pre-instruction) lasts less than 2 min (00:01:53) and counts 227 words. It shares some features of the docu-tour and some others of the guided tour. More specifically, Student A is always on screen, looking at the camera and is standing in front of the museum’s doors while talking about the exhibit (cfr. Figure 1), as in a docu-tour. She acts like a tour guide, using the personal pronoun you and a few gestures, which, however, are not used to explain specialised terms. In the transcript of example (1) below, focus vocabulary is highlighted in bold, words used to express a particular verbal strategy for accessibility are in italics followed by the corresponding label within square brackets, while the symbol “[ ]” indicates that a gesture is performed:

]” indicates that a gesture is performed:

| Clip 1 from the Torture Museum, Student A |

Today I will give you some information about the Torture Museum of Lucca [image: sign]. It is situated along the most famous street [ ] of the city, which is Via Fillungo [denomination]. ] of the city, which is Via Fillungo [denomination]. |

In Figure 1, Student A names the museum but does not elaborate on the meaning of torture in this context. Since the site is closed, she relies on the museum sign behind her (i.e., see Image tier), which can barely be seen. Only after a few moments does she provide a definition, thus relying on the verbal element alone:

| Extract from the Torture Museum, Student A |

| But, first of all, we have to define what torture is, and it is a physical and psychological method of coercion , inflicted to punish or extort information or confessions [definition]. |

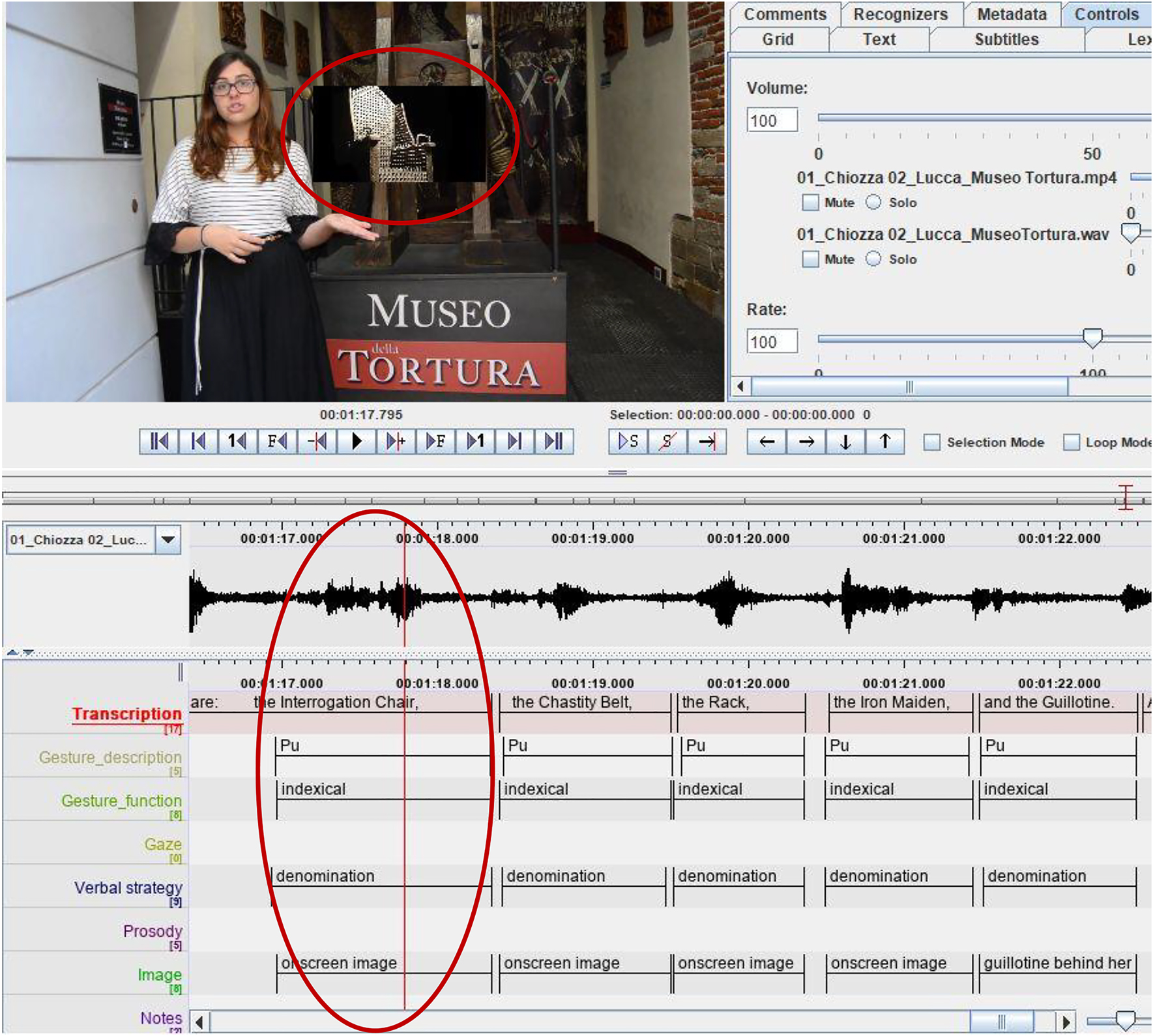

Clip 2 (post-instruction) is a docu-tour and is briefer than clip 1, lasting approximately 1 min and a half (00:01:25), and counting 211 words. Student A appears much more relaxed and professional: the museum is open this time, so she enters and starts talking while walking around, with the museum sign and one of the exhibits, i.e., a guillotine, clearly visible on the screen (Figure 2).

Entrance, clip 2, Student A.

The speaker is often on screen, even though when she introduces the main idea and purpose of the museum, she prefers voiceover, so that the viewer can see a room with its displays. Most importantly, in this second clip, the verbal message is associated with images, which Student A adds and makes appear on screen, accompanying them with gestures, to make specialised terms accessible to the viewer. For example, when she lists the most important instruments that are part of the exhibit, the corresponding image appears for each one and is highlighted with a gesture, annotated as “Pu” or Palm up in the Gesture_description tier, and performing an indexical function, as in extract (3) and Figure 3 below. By comparison, in clip 1, she simply listed them by using gestures for enumeration.

Integration of verbal and non-verbal cues in clip 2, Student A.

| Clip 2 from the Torture Museum, Student A |

The most important, the most famous are the

Interrogation Chair

[denomination] [image] [ ], the

Chastity Belt

[denomination] [image] [ ], the

Chastity Belt

[denomination] [image] [ ], the

Iron Maiden

[denomination] [ ], the

Iron Maiden

[denomination] [ ] [image], the

Guillotine

[denomination] [image] [ ] [image], the

Guillotine

[denomination] [image] [ ]. ]. |

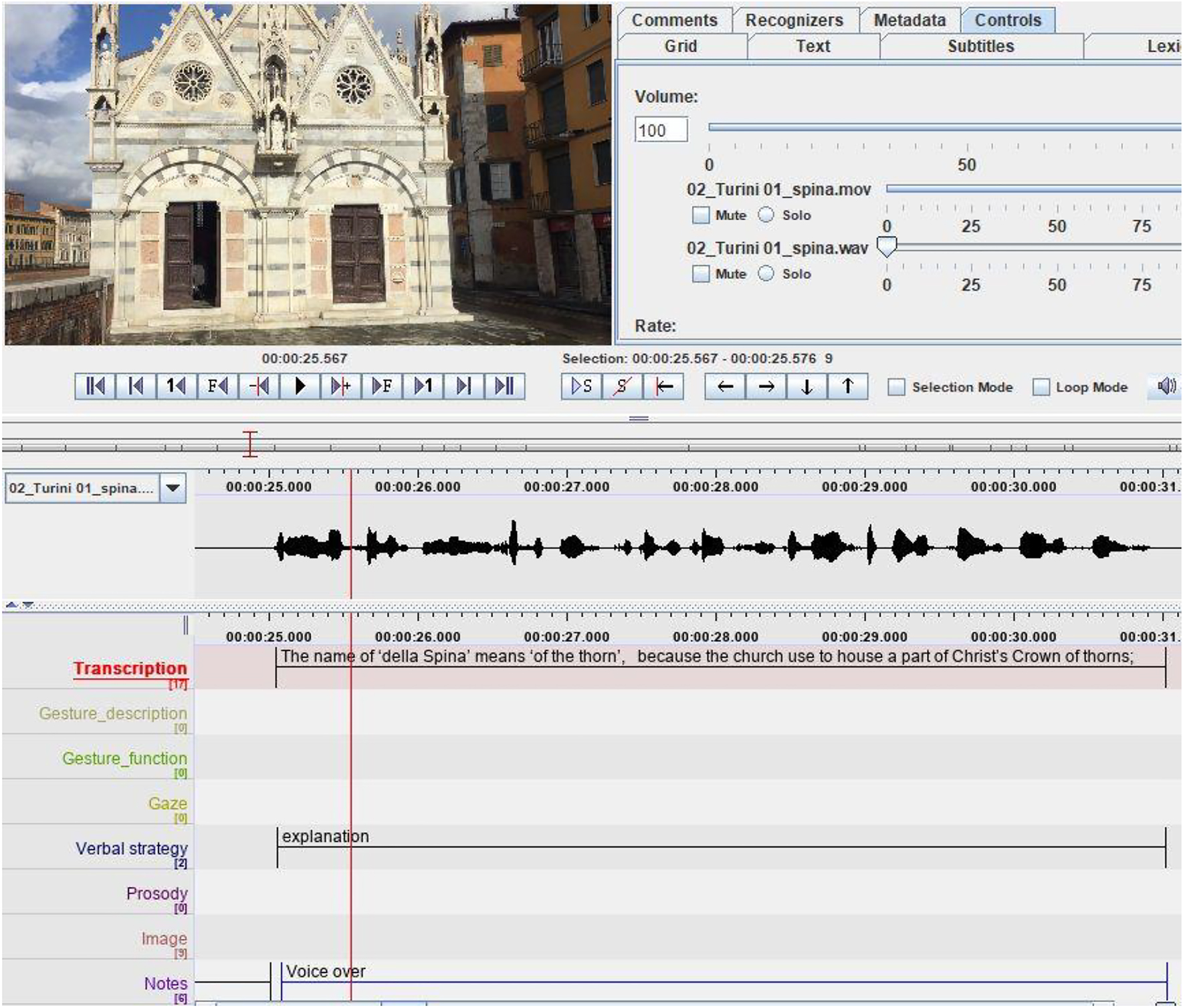

5.2 Case study 2: Chiesa della Spina, Pisa

The next pair of clips were shot by Student B at a famous church in Pisa, Chiesa della Spina. Clip 1 and Clip 2 are almost of the same length and approximate word count (00:02:10 and 212 words, Clip 1, vs. 00:01:53 and 204 words, Clip 2). However, a shift in genre can be noticed from Clip 1, which is merely a documentary, to Clip 2, which is a docu-tour proper. Indeed, in Clip 1, the speaker always uses the voice over technique that is typical of documentaries, delivering information in a scripted style. Moreover, she associates images with the verbal element only occasionally, since often the image of the church is employed in a general way, even when she is describing the details. Extract (4) shows an example where Student B explains the name of the church by using the term thorn, which is repeated three times but without any other specific aid to help the viewer understand it; conversely, the image of the façade of the church can be seen the whole time (cf. Figure 4):

Example of image not strictly associated to verbal elements in clip 1, Student B.

| Clip 1 from Chiesa della Spina, Student B |

| The name of ‘della Spina’ means ‘of the thorn’ [explanation], because the church used to house a part of Christ’s Crown of thorns; now we can find that thorn in another church called Chiesa di Santa Chiara. |

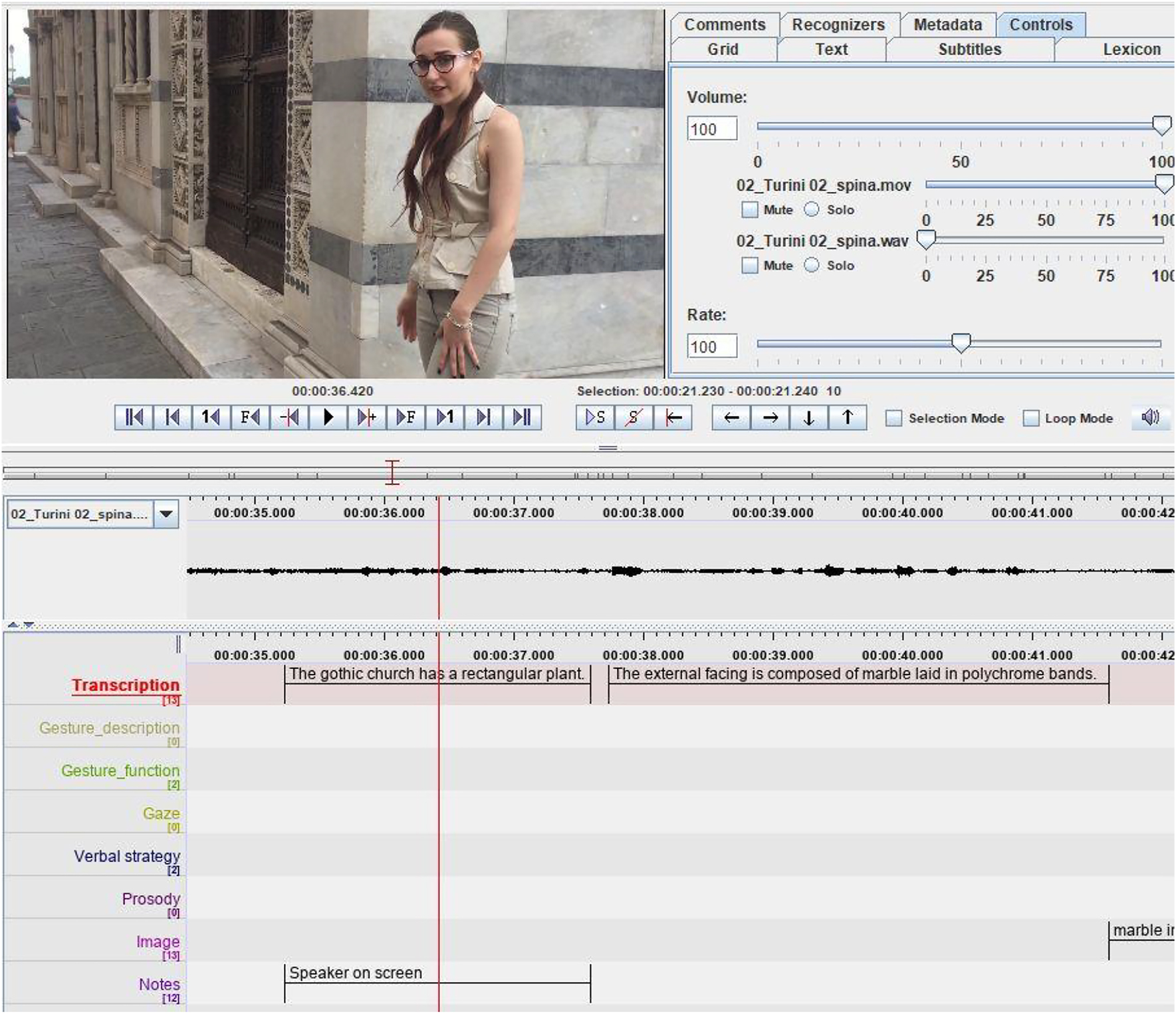

In the first part of Clip 2, Student B appears on screen, while in the second part, once again, the voice over technique is preferred (“[vo]” in example 5). However, in the first part, the speaker actively uses images as an important tool for understanding and engages with the viewer by looking directly at the camera and through gestures, mainly with an indexical function. In example (5), the speaker walks around the church while describing its plan (erroneously indicated as plant in the transcript), as she shows it to the viewer (cf. Figure 5), and then lets images help her clarify the meaning of the various specialised terms related to architecture needed to describe the church (cf. Figure 6):

Integration between the verbal element and images in clip 2, Student B.

Use of images to explain the term cusps in clip 2, Student B.

| Clip 2 from Chiesa della Spina, Student B |

| The gothic church has a rectangular plant. The external facing [image] is composed of marble laid in polychrome bands [image]. |

| [vo] We can find cusps [image], tympani [image] and tabernacles [image] together with a complicated sculpture decoration [image]. |

6 Multimodal learner corpus versus multimodal L1 corpus

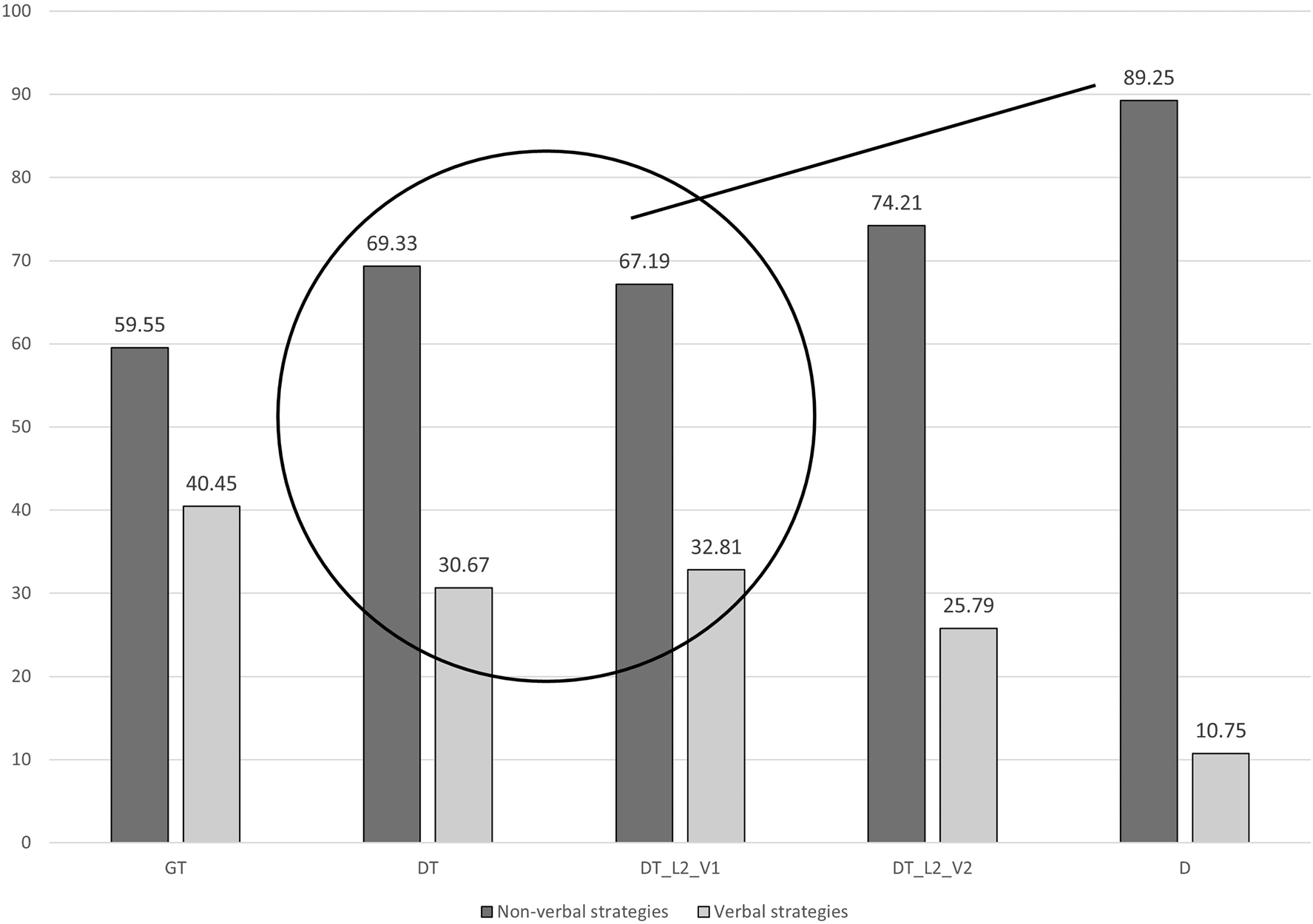

The analysis exemplified in Sections 5.1 and 5.2 has allowed us to evaluate the collected data both quantitatively and qualitatively. The distribution of strategies for the clarification of specialized terminology shows that, as in authentic materials, overall, non-verbal strategies are more commonly used than verbal strategies. We also found that, in the learners’ clips, the distribution is comparable to that in the L1 docu-tours. A slightly larger preference for verbal strategies was observed in L2 Clip 1 (L2 33 vs. L1 31%). However, a 7% increase in the use of non-verbal strategies was found in the videos produced after instruction, pushing the distribution patterns in Clip 2 closer to the data observed for documentaries in L1 (cf. Figure 7).

Distribution of verbal and non-verbal strategies in guided tours (GT), docu-tours (DT), learner’s videoclip 1 (DT_L2_V1), learners’ videoclip 2 (DT_L2_V2) and documentaries (D).

In docu-tours, non-verbal strategies often overlap with verbal strategies. Thus, in a style that is similar to that of guided tours, speakers offer a verbal explanation of unfamiliar concepts while, at the same time, images (static or in the form of short narrative videos) echo their words as in a “canonical” documentary. However, docu-tours can be planned like documentaries. The latter, though, are usually thoroughly scripted and edited and therefore the authors can pair non-verbal elements and terminology in an effective way to ensure maximum explanatory power.

As mentioned, learners seemed to resort to non-verbal strategies more frequently in Clip 2 than in Clip 1. We ascribe this result to the novelty effect exercised by the classroom activities. Another possible explanation is that, given the participants’ low proficiency level in English (B1), they exploited the newly discovered non-verbal strategies more extensively in their second clips to compensate for their relatively poor command of the language. The compensatory exploitation of multimodal resources is a known process in both L1 and L2 development (Gullberg and De Bot 2010). Gestures in L2 narratives can supplement and disambiguate incomplete or inaccurate information (Cristilli 2014). It is therefore plausible that the participants’ improved multimodal competence enhanced their expressive repertoire and provided them with new communicative tools to create semantic accessibility despite their limited proficiency in the foreign language.

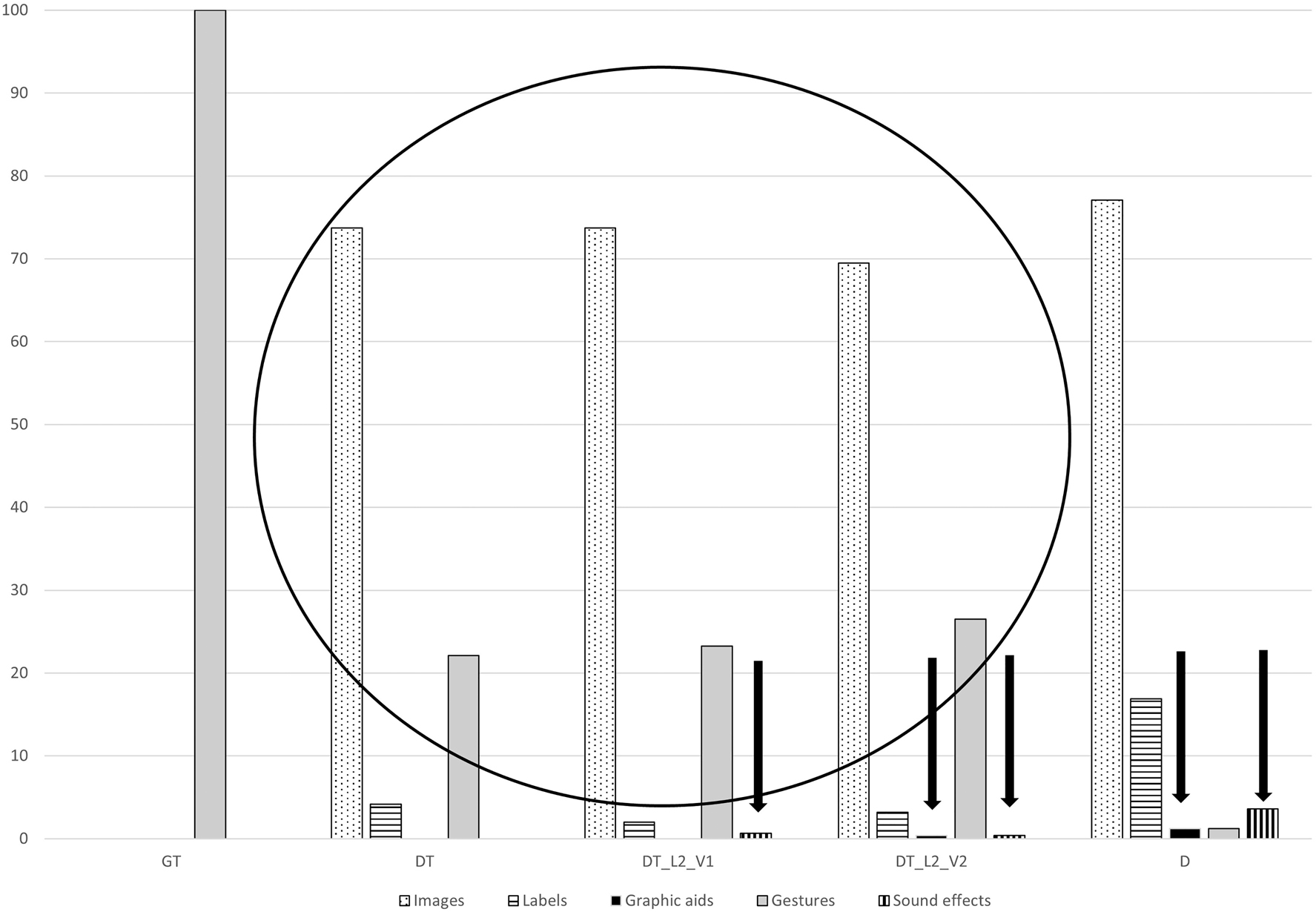

We then analysed the distribution of the individual verbal and non-verbal strategies used. The non-verbal strategies were similar both in type and distribution to those used in authentic docu-tours, where accessibility is mostly maximized through the use of images, gestures and labels added in the editing stage (cf. Figure 8).

Distribution of individual non-verbal strategies.

Learners resorted to sound effects as well (although minimally) and, in their second clips, to graphic aids. Learners’ Clip 2 saw an increase in the use of gestures and images and the introduction of labels and more sound effects, although in a very low percentage. This confirms that, in the second clip, tools were used that are more typical of post-edited materials. We relate this to the fact that, in the instruction phase, we worked on all three genres at the same time, and this may have generated some uncertainty in the participants as to the defining features of each genre. The fuzzy boundaries between documentaries and other professionally edited docu-tours may also have contributed to this result.

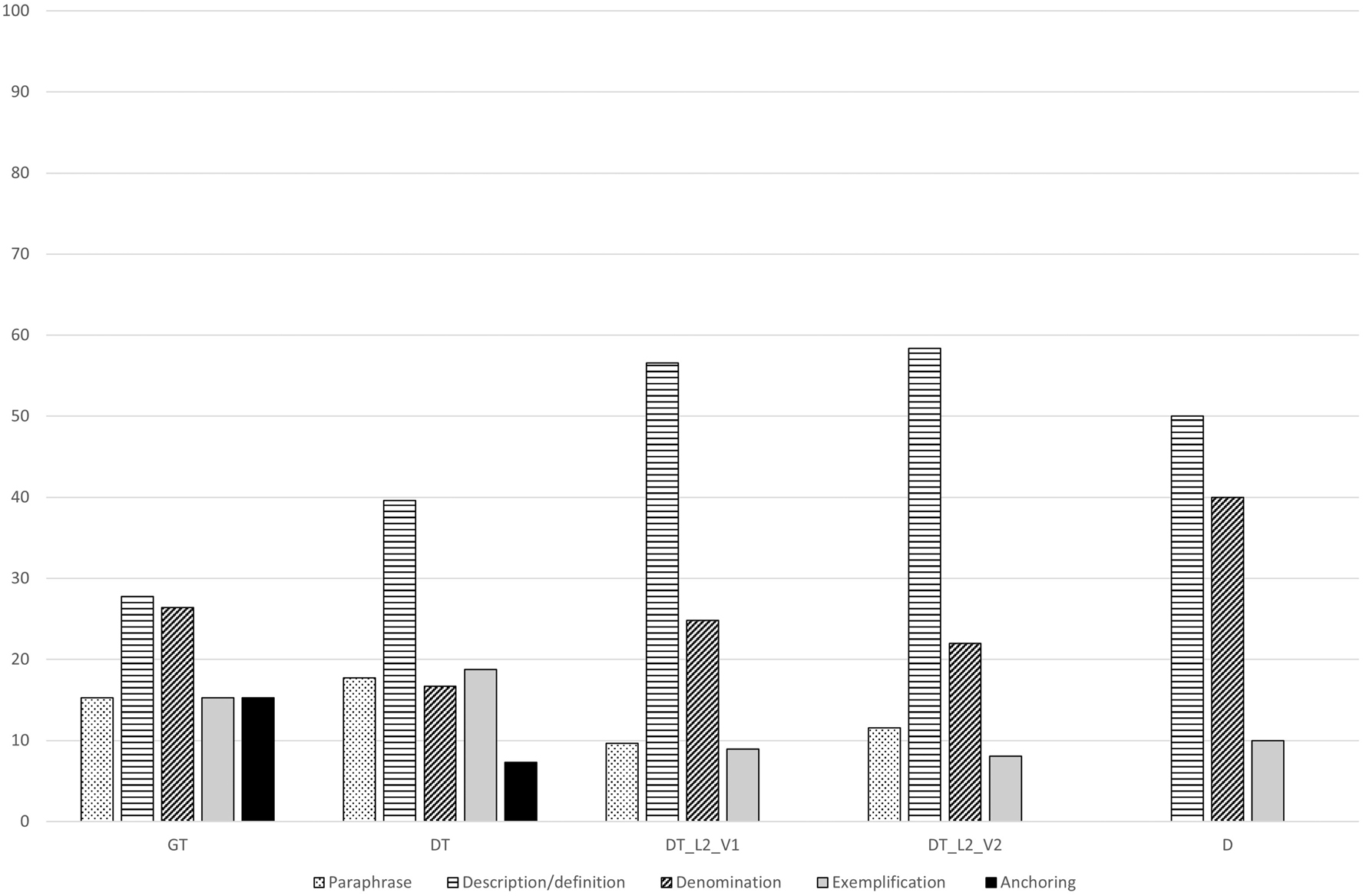

The analysis of the individual verbal strategies showed a marked preference for descriptions, definitions, denomination and exemplification, that is, for strategies which involve proper planning, similar to what happens in L1 documentaries. In the learners’ docu-tours, descriptions and definitions were used more extensively than in the authentic materials. However, we also observed a frequent use of paraphrase, which is typical of L1 docu-tours and hardly found in documentaries. In the L1 multimodal corpus, paraphrase was mostly found in guided tours and docu-tours in the form of rephrasing, which is more typical of spontaneous spoken communication than planned scripted language. In the learner corpus, paraphrase was mainly realized through appositions and the use of more general synonyms. Interestingly, we found no instances of anchoring (i.e., the reference to concepts or experiences that are familiar to the tourist and which can help explain unfamiliar ones analogically), which is quite common in L1 docu-tours (Figure 9).

Distribution of verbal strategies.

The learners’ choices may be explained by their experience with linguistic structures to describe, define, exemplify and paraphrase, which are usually part of the B1–B1+ syllabus in most commercial EfT coursebooks (e.g., Strutt 2013; Walker and Harding 2007). Moreover, learners may have prepared and revised the script for their commentary before recording the videos (especially Clip 2) and have used chunks of information taken from guidebooks and other videos about Pisa and Lucca. Thus, their products might be more heavily scripted than most L1 docu-tours. In addition, their proficiency level might have hindered the production of a more spontaneous and colloquial form of presentation typical of docu-tours. Finally, the total lack of anchoring to the tourist’s experience and cultural knowledge may be due to the fact that learners are likely unaware of differences and similarities between their own culture and that of their audience.

7 Concluding remarks

The aim of this article was to report on the learners’ use of the strategies used to ensure comprehension of “difficult” terms or concepts. A general improvement in mastering the generic features of the docu-tour was observed (e.g., the use of multimodal resources, and of anecdotes and humour for creating a relationship with the audience). Given that no explicit guidelines were given on how to revise Clip 1 to produce Clip 2, this was considered an effect of the work carried out in class.

In terms of the skills necessary to create accessibility when specialized terminology and culturally-loaded terms are involved, the fact that Clip 1 shared many features of L1 docu-tours indicates that our EfT learners already had a good spontaneous understanding of the features of the genre before the instruction phase. This is probably because travel programmes including instances of this genre have recently become quite popular in Italy (e.g., Ulisse [3]). The learners’ prior multimodal literacy might therefore have proven an asset and provided scaffolding for the development of the linguistic resources necessary to make tourism communication accessible to a wider audience. The instruction phase would have contributed to developing the verbal strategies and the ability to pair them appropriately with familiar and novel non-verbal strategies. The changes that could be observed in the learners’ clips point therefore towards progress in their communicative competence and confirm that multimodal literacy should be considered as an integral part of language proficiency rather than an addition. Effective communication involves a wider range of semiotic resources beyond verbal language, which language learners need to acknowledge especially in domain specific discursive contexts (Crawford Camiciottoli 2019). However, the effort made to develop this new multimodal communicative competence may be responsible for reduced accuracy observed at the lexical level (e.g., pronunciation mistakes, wrong choice of words). If we accept the view that growth in language development is resource dependent (De Bot et al. 2007), it is possible that progress in one domain may have resulted in a temporary delay in the advancement of another. Future research should include activities specifically designed to support vocabulary growth and verify how this impacts the overall development of the learners’ communicative proficiency.

The study has a few limitations. Firstly, due to the degree programme’s regulations which require that all students receive identical instruction, it lacks data from a control group. Secondly, the students had a low proficiency level of English (A2-B1), which may be responsible for the “scripted feel” of the verbal component in their docu-tours. Thirdly, work on the L1 genres overlapped in the instruction phrase, and the boundaries between different types of verbal strategies are sometimes fuzzy. To conclude, it would certainly be interesting to replicate the project with more advanced learners and to verify the impact of the L1 conventions for the same genres.

Overall, the task-based project also contributed to the learners’ professional development because it pushed them to create and improve an instance of an existing genre belonging to spoken tourism discourse, a “product” which brings together many relevant skills for communication in the tourism industry and may well be useful in their future careers. Moreover, exploiting the learners’ ability to “read” multimodal materials, the instruction phase prompted the learners’ reflection on the importance of taking into account the cultural background of their interlocutors, as well as on the most typical and natural strategies used in English to create accessibility (which may differ from those used in their L1).

References

Ackerley, K. and Coccetta, F. (2007). Enriching language learning through a multimedia corpus. ReCALL 19: 351–370, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0958344007000730.Search in Google Scholar

Agorni, M. and Spinzi, C. (Eds.) (2019). Mind the gap in tourism discourse: traduzione, mediazione, inclusione, Altre Modernità 21. https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/AMonline/issue/view/1392.Search in Google Scholar

Ap, J. and Wong, K.K. (2001). Case study on tour guiding: professionalism, issues and problems. Tourism Manag. 22: 551–563, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-5177(01)00013-9.Search in Google Scholar

Ariel, M. (2006). Accessibility theory. In: Allan, K. (Ed.). Concise encyclopedia of semantics. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 15–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-044854-2/04291-7.Search in Google Scholar

Bonsignori, V. (2016). Analysing political discourse in film language: a multimodal approach. In: Bonsignori, V. and Crawford Camiciottoli, B. (Eds.). Multimodality across communicative settings, discourse domains and genres. Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, pp. 189–211.Search in Google Scholar

Bonsignori, V. (2018). Using films and TV series for ESP teaching: a multimodal perspective. System 7: 58–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.01.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bonsignori, V. and Cappelli, G. (2020). Specialized and culture-bound knowledge dissemination through spoken tourism discourse: multimodal strategies in guided tours and documentaries. Lingue Linguaggio 40: 213–239, https://doi.org/10.1285/i22390359v40p213.Search in Google Scholar

Calsamiglia, H. (2003). Popularization discourse. Discourse Stud. 5: 139–146, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445603005002307.Search in Google Scholar

Calsamiglia, H. and Van Dijk, T.A. (2004). Popularization discourse and knowledge about the genome. Discourse Soc. 15: 369–389, https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926504043705.Search in Google Scholar

Cappelli, G. (2016). Popularization and accessibility in travel guidebooks for children in English. Cultus 9: 68–89.Search in Google Scholar

Cappelli, G. and Bonsignori, V. (2019). Teaching spoken English for tourism through project work and authentic clips: a pilot study. In: Danjo, C., Meddegama, I., O’Brien, D., Prudhoe, J., Walz, L., and Wicaksono, R. (Eds.). Taking risks in applied linguistics: online proceedings of the 51st annual meeting of the British Association for Applied Linguistics, York St John University, 6–8 September 2018, pp. 7–9, Retrieved from BAAL 2018, Available at: http://www.cvent.com/events/baal-2018-annual-meeting/custom-21-78e684777ce54042b0e7fd5e79f5dc7b.aspx (Accessed 9 July 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Cappelli, G. and Masi, S. (2019). Knowledge dissemination through tourist guidebooks: popularization strategies in English and Italian guidebooks for adults and for children. In: Bondi, M., Cacchiani, S., and Cavalieri, S. (Eds.). Knowledge dissemination at a crossroads. Genres and new media today. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, pp. 124–161.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, E. (1985). The tourist guide: the origins, structure and dynamics of a role. Ann. Tourism Res. 12: 5–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(85)90037-4.Search in Google Scholar

Costa, M. and Ravetto, M. (2018). Asymmetries and adaptation in guided tours with German as a foreign language. In: Held, G. (Ed.). Strategies of adaptation in tourist communication. Brill, Amsterdam, pp. 145–158.Search in Google Scholar

Cox‐Petersen, A.M., Marsh, D.D., Kisiel, J., and Melber, L.M. (2003). Investigation of guided school tours, student learning, and science reform recommendations at a museum of natural history. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 40: 200–218.10.1002/tea.10072Search in Google Scholar

Crawford Camiciottoli, B. (2019). Harnessing multimodal literacy for knowledge dissemination in ESP. In: Bonsignori, V., Cappelli, G., and Mattiello, E. (Eds.). Worlds of words: complexity, creativity and conventionality in English language, literature and culture, Vol. I – Language. PUP, Pisa, pp. 47–52.Search in Google Scholar

Cristilli, C. (2014). How gestures help children to track reference in narrative. In: Seyfeddinipur, M. and Gullberg, M. (Eds.). From gesture in conversation to visible action as utterance. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 331–350.10.1075/z.188.15criSearch in Google Scholar

Dann, G. (1996). The language of tourism: a sociolinguistic perspective. Cab International, Oxford.10.1079/9780851989990.0000Search in Google Scholar

De Bot, K., Lowie, W., and Verspoor, M. (2007). A dynamic systems theory approach to second language acquisition. Bilingualism 10: 7–21, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728906002732.Search in Google Scholar

Díaz Ramírez, M.I. (2014). Developing learner autonomy through project work in an ESP class. HOW 21: 54–73, https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.4.Search in Google Scholar

Dybiec, J. (2008). Tourist’s guidebooks: tackling cultural identities in translator training pedagogy. A Polish-Portuguese case study. In: Gonçalves, S. (Ed.). Identity, diversity and intercultural dialogue. ESEC, Coimbra, pp. 65–74.Search in Google Scholar

ELAN (Version 5.9) [Computer software]. (2020). Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive, Available at: https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan.Search in Google Scholar

El-Said, O. and Aziz, H. (2021). Virtual tours a means to an end: an analysis of virtual tours’ role in tourism recovery post COVID-19. J. Trav. Res., https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287521997567.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, R. (2018). Reflections on task-based language teaching. Multilingual Matters, Bristol.10.21832/ELLIS0131Search in Google Scholar

Francesconi, S. (2014). Reading tourism texts: a multimodal analysis. Channel View Publications, Bristol.10.21832/9781845414283Search in Google Scholar

Fukuda, C. and Burdelski, M. (2019). Multimodal demonstrations of understanding of visible, imagined, and tactile objects in guided tours. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 52: 20–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1572857.Search in Google Scholar

Gotti, M. (2006). The language of tourism as specialized discourse. In: Palusci, O. and Francesconi, S. (Eds.). Translating tourism. Linguistic/cultural representations. Editrice Università degli Studi di Trento, Trento, pp. 15–34.Search in Google Scholar

Gotti, M. (2014). Reformulation and recontextualization in popularization discourse. Ibérica 27: 15–34.Search in Google Scholar

Gullberg, M. and De Bot, K. (Eds.) (2010). Gestures in language development. John Benjamins, Amsterdam.10.1075/bct.28Search in Google Scholar

Hafner, C.A. and Miller, L. (Eds.) (2019). English in the disciplines. In: A multidimensional model for ESP course design. Routledge, London.10.4324/9780429452437Search in Google Scholar

Ignatova, E. (2018). Multimodal corpus analysis of representations of travel destinations: two methodological approaches. In: The 4th corpora and discourse international conference. Lancaster University. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/145316/.Search in Google Scholar

Kaiser, M. (2011). New approaches to exploiting film in the foreign language classroom. L2 J. 3: 232–249, https://doi.org/10.5070/l23210005.Search in Google Scholar

Kalantzsis, M. and Cope, B. (2013). Multiliteracies in education. In: Chapelle, C.A. (Ed.). The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 3963–3969.10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0809Search in Google Scholar

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: visible action as utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511807572Search in Google Scholar

Kress, G. and van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Visual images. The grammar of visual design. Routledge, London.Search in Google Scholar

Lopriore, L. (2015). Being there: travel documentaries. Iperstoria 6: 216–228.Search in Google Scholar

Maci, S.M. (2020). English tourism discourse: insights into the professional, promotional and digital language of tourism. Hoepli Editore, Milan.Search in Google Scholar

Mamakou, I. (2009). Project-based instruction for ESP in higher education. In: de Cássia Veiga Marriott, R. and Torres, P. Lupion (Eds.). Handbook of research on e-learning methodologies for language acquisition. IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 456–479.10.4018/978-1-59904-994-6.ch028Search in Google Scholar

Manca, E. (2016). Persuasion in tourism discourse: methodologies and models. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.Search in Google Scholar

Myers, G. (2003). Discourse studies of scientific popularization: questioning the boundaries. Discourse Stud. 5: 265–279, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445603005002006.Search in Google Scholar

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: a methodological framework. Routledge, London.10.4324/9780203379493Search in Google Scholar

O’Halloran, K.L. (Ed.) (2004). Multimodal discourse analysis: systemic functional perspectives. Continuum, London.Search in Google Scholar

Pierroux, P. (2010). Guiding meaning on guided tours. In: Morrison, A. (Ed.). Inside multimodal composition. Hampton Press, Kresskill, NJ, pp. 417–450.Search in Google Scholar

Plastina, A.F. (2013). Multimodality in English for specific purposes: reconceptualizing meaning-making practices. Rev. Lenguas Fines Específicos 19: 372–396.Search in Google Scholar

Prior, P. (2013). Multimodality and ESP research. In: Paltridge, B. and Starfield, S. (Eds.). The handbook of English for specific purposes. Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA, pp. 519–534.10.1002/9781118339855.ch27Search in Google Scholar

Querol-Julián, M. (2011). Evaluation in discussion sessions of conference paper presentation: a multimodal approach. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrücken.Search in Google Scholar

Rastati, R. (2020). Virtual tour: tourism in the time of Corona. In: 6th international conference on social and political sciences (ICOSAPS 2020). Atlantis Press, Dordrecht, pp. 489–494.10.2991/assehr.k.201219.074Search in Google Scholar

Royce, T. (2002). Multimodality in the TESOL classroom: exploring visual‐verbal synergy. Tesol Q. 36: 191–205, https://doi.org/10.2307/3588330.Search in Google Scholar

Scollon, R. and Levine, P. (Eds.) (2004). Multimodal discourse analysis as the confluence of discourse and technology. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC.Search in Google Scholar

Sherman, J. (2003). Using authentic video in the language classroom. CUP, Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

Stoller, F. (2006). Establishing a theoretical foundation for project-based learning in second and foreign language contexts. In: Beckett, G.H. and Miller, P.C. (Eds.). Project-based second and foreign language education: past, present, and future. Information Age Publishing, Greenwich, Connecticut, pp. 19–40.Search in Google Scholar

Strutt, P. (2013). English for international tourism, New ed. Intermediate coursebook. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow.Search in Google Scholar

Thurlow, C. and Jaworski, A. (2011). Tourism discourse: languages and banal globalization. Appl. Ling. Rev. 2: 285–312, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.285.Search in Google Scholar

Urry, J. (2002). The tourist gaze. SAGE, London.Search in Google Scholar

Walker, R. and Harding, K. (2007). Oxford English for careers. Tourism 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Webb, S. and Rodgers, H. (2009). The lexical coverage of movies. Appl. Ling. 30: 407–427, https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp010.Search in Google Scholar

Weinberg, A., Fukawa-Connelly, T., and Wiesner, E. (2013). Instructor gestures in proof-based mathematics lectures. In: Martinez, M. and Castro Superfine, A. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 35th annual meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for the psychology of mathematics education, Vol. 1119. University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago.Search in Google Scholar

Zillinger, M., Jonasson, M., and Adolfsson, P. (2012). Guided tours and tourism. Scand. J. Hospit. Tourism 12: 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.660314.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Veronica Bonsignori and Gloria Cappelli, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Towards developing multimodal literacies in the ESP classroom: methodological insights and practical applications

- Teaching communication strategies for the workplace: a multimodal framework

- Enhancing multimodal communicative competence in ESP: the case of job interviews

- Developing strategies for conceptual accessibility through multimodal literacy in the English for tourism classroom

- Engaging students in multimodal literacy practices in a university ESP context: towards understanding identity and ideology in government debates

- Growing theory for practice: empirical multimodality beyond the case study

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Towards developing multimodal literacies in the ESP classroom: methodological insights and practical applications

- Teaching communication strategies for the workplace: a multimodal framework

- Enhancing multimodal communicative competence in ESP: the case of job interviews

- Developing strategies for conceptual accessibility through multimodal literacy in the English for tourism classroom

- Engaging students in multimodal literacy practices in a university ESP context: towards understanding identity and ideology in government debates

- Growing theory for practice: empirical multimodality beyond the case study