Abstract

I evaluated bat assemblages in terms of species richness, relative abundance, trophic guild structure, and seasonal changes at three sites along of the Southern Yungas forests. A total of 854 individuals were captured, representing 25 species of three families, with an effort of 27,138 m of mist net opened per hour. Subtropical assemblages showed a similar structure to those from tropical landmark, with a dominance of frugivorous Phyllostomid; in addition, a few species were abundant, followed by a long tail of less common species. However, subtropical sites differed due to the dominance of the genus Sturnira and the great contribution to richness of Vespertilionidae and Molossidae families. Contrary to my original expectations, the latitudinal gradient of species richness does not seem to produce significant differences in richness between the northern and the southern sites, with the central site being different. Furthermore, guild structure and captures did not change between seasons. However, I found a high variation in guild structure among sites due to changes in β diversity and latitudinal lack of species with tropical filiations. These changes generated great differences in functional structure among assemblages, with eight guilds in the north and only four in the remaining sites. Moreover, other variables, such as roost site and resource availability, climatic conditions, and particular attributes of each species, could also be important in determining local richness and guild structure.

Introduction

In the Neotropics, bats account for about 50% of the mammal diversity, greatly influencing the structure and functionality of these communities (e.g., Simmons and Voss 1998, Aguirre 2002, Sampaio et al. 2003). Bats have a great diversity of dietary habits, playing a crucial functional roles as pollen and seed dispersers (Muscarella and Fleming 2007, Lobova et al. 2009) and as predators of arthropods and small vertebrates (Giannini and Kalko 2005, Kalka et al. 2008). Moreover, bats are important components in the diet of several predatory animals such as birds, reptiles, and others mammals (including other bats; Kunz and Parsons 2009), suggesting that bats may be important regulators of complex ecological processes and may provide important ecosystem services in Neotropical rainforests (Aguirre 2002, Kunz et al. 2011). An assemblage is a community subset defined by taxonomic constraints (Fauth et al. 1996). Many studies have analyzed tropical bat assemblages with the aim of describing their organization and understanding the mechanisms that determine their structure, which affects the composition and abundance of its constituent species (e.g., Kalko et al. 1996, Aguirre 2002, Aguirre et al. 2003, Sampaio et al. 2003). However, relatively few studies have analyzed bat assemblages in subtropical forests, especially in subtropical rainforests of South America (e.g., Bracamonte 2010, Weber et al. 2011).

In Argentina, bats represent ca. 18% of the 340 recognized terrestrial mammalian species, including 60 species belonging to four families (Barquez et al. 2006, 2013, Udrizar Sauthier et al. 2013). The major richness of this group is found in northern Argentina (Barquez et al. 2006), especially in montane Yungas forests and in lowland Atlantic forests. Interestingly, these forests represent the only subtropical rainforests in South America; both are situated mostly in northwestern and northeastern Argentina, being characterized by a strong and mild seasonality in annual rainfall, respectively (Hueck 1978, Di Bitetti et al. 2003). In the Yungas, bat richness declines with latitude (Barquez and Díaz 2001, Ojeda et al. 2008), being the limit of the southernmost distribution range for several tropical species (see Gardner 2007). Most of the studies conducted in this region have been focused on bat inventories and geographic distributions (e.g., Sandoval et al. 2010a) or on biogeographical patterns and ecological aspects of the diet (e.g., Sandoval et al. 2010b, Sánchez et al. 2012a,b). These studies contributed to the resolution of several taxonomic conflicts, the identification of areas of endemism, and the recognition of different life history aspects of some species. However, no study involving community characteristics such as species diversity and guild structure has been conducted. Describing the structure and dynamics of bat assemblages as affected by seasonality is an important step toward understanding the dynamics of mammal community in this subtropical forest. The aim of this study was to compare the structure of bat assemblages in terms of species richness, relative abundance, trophic guild structure, and seasonal variation at three sites along of the Southern Yungas forests. Particularly, significant changes in richness and guild structure in assemblages were expected due to seasonality in rainfall and latitudinal differences among sites.

Materials and methods

Study sites

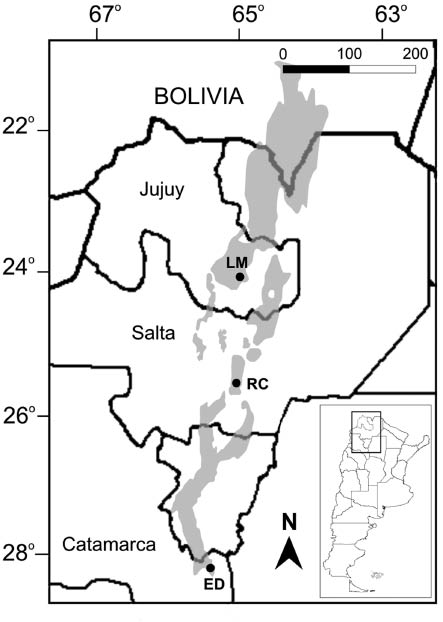

The study area was located in the Southern Yungas biogeographic province, northwestern Argentina (Cabrera 1976). In Argentina, these forests form a long and narrow east-west belt on the eastern slopes of the Andes, between 22° and 28°S (Brown et al. 2001). Climate is bi-seasonal, with a wet and hot austral “summer” (wet season, November–April, 80% of the annual rainfall) and a dry and mild austral “winter” (dry season, May–October; Hunzinger 1995). Annual rainfall varies between 1000 and 2000 mm (Brown et al. 2001), and the mean annual temperature is 19°C (Minetti et al. 2005). Three sites were studied along ca. 460 km in Yungas forests (Figure 1): (1) Laja Morada in Finca Las Capillas, Jujuy Province (24°02′S, 65°07′W, 1000 m a.s.l.; hereafter “LM”); (2) Río de Las Conchas in Salta Province (25°28′S, 65°00′W, 925 m a.s.l.; hereafter “RC”); (3) El Durazno in Catamarca Province (28°06′S, 65°36′W, 760 m a.s.l.; hereafter “ED”). Additional details of these locations are given in Sánchez (2011) and Sánchez et al. (2012a,b).

Map of Northern Argentina showing the locations sampled for bats.

LM, Laja Morada; RC, Río de Las Conchas; ED, Finca El Durazno. Subtropical rainforests are shaded in the map (after Brown et al. 2001).

Bat sampling

At each study site, bats were sampled using ten mist nets (12, 9, and 6 m×2.5 m) 40–50 m apart from one another. Nets were placed on the ground, at the subcanopy level (6–8 m high) inside the forest, in flight pathways, in riparian forest, over water and across creeks during five consecutive nights, changing net location frequently; mist nets were operated for approximately 6 h from sunset and were checked every 30 min. LM was sampled twice in the dry season and twice in the wet season between January 2006 and April 2007, RC and ED were sampled twice in the dry season and three times in the wet season between December 2005 and May 2007. Each captured bat was removed from the net and placed in cloth bags for data collection and identification; taxonomic treatment follows Barquez et al. (1999). For each specimen, we recorded forearm length to the nearest 0.1 mm using a digital caliper DIGIMESS® (Buenos Aires, Argentina), body mass to the nearest 0.5 g using a spring scale PESOLA™ (Baar, Switzerland), sex, and age (juvenile or adult). Bats were marked by trimming the hair on the back to avoid multiple counting of recapture; then they were released near the capture site. Recaptures were not included in the analyses. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Colección Mamíferos Lillo, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Argentina. It is known that mist-netting captures have a bias toward one part of bat fauna (Kalko and Handley 2001), i.e., some species are more likely to be captured using this method. However, annual bat capture based on intensive small-scale trapping with mist nets can be a useful tool for sampling bats in the Neotropics and allows broader comparison between studies (see Aguirre 2002, Estrada and Coates-Estrada 2002, Sampaio et al. 2003).

Analyses

All bats species were classified into the trophic groups or guilds proposed by Bonaccorso (1979), Kalko et al. (1996), and Schnitzler and Kalko (1998). Guild definition was based on three characteristics: foraging habitat, foraging mode, and diet. The first characteristic described the complexity of the acoustic environment of echolocation (uncluttered, background cluttered, and highly cluttered space); the second characteristic was related to foraging mode (aerial, gleaning, and trawling behavior); and the last one was defined by predominant items in the diet (e.g., arthropods, fruits, pollen, nectar, blood, or vertebrates). In addition, frugivorous species were differentiated by their tendency to forage mainly in the canopy or the understory. I used ecological data from literature to classify each bat species into the guild (e.g., Bonaccorso 1979, Schnitzler and Kalko 1998, Barquez et al. 1999, Gardner 2007, Sandoval et al. 2010b, Sánchez et al. 2012a). Species richness among sites was compared using individual-based rarefaction curve; 95% of confidence interval (CI) was estimated using EcoSim (Gotelli and Entsminger 2004). Because in classic rarefactions analysis both extremes of CI are zero, I also calculated rarefaction curves using unconditional variance expressions, a conservative analysis that assumes that a sample represents a random draw from a larger community (i.e., CIs remain open at the full-sample end of the curve; Colwell et al. 2012). This analysis was carried out using EstimateS 9 (Colwell 2013).

Differences in specific composition and guild structure among assemblages were evaluated using an analysis of similarity (ANOSIM); this is a nonparametric permutation test used to test the difference between two or more groups of sampling units (Clarke 1993). The contribution of each bat species to dissimilarity among assemblages was examined using SIMPER percentage analysis (Clarke 1993). All data were standardized as the number of individuals captured per 1000 m-net-h (meters of mist net opened per hour) and transformed to the log10(x+1) function before analyses. Statistical analyses were run in Primer v5 (Clarke and Gorley 2001) and R (R Development Core Team 2013). In addition, differences in richness, bat captures, and guild abundance among assemblages and seasons were tested with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey HSD post hoc test.

Results

Captures and richness

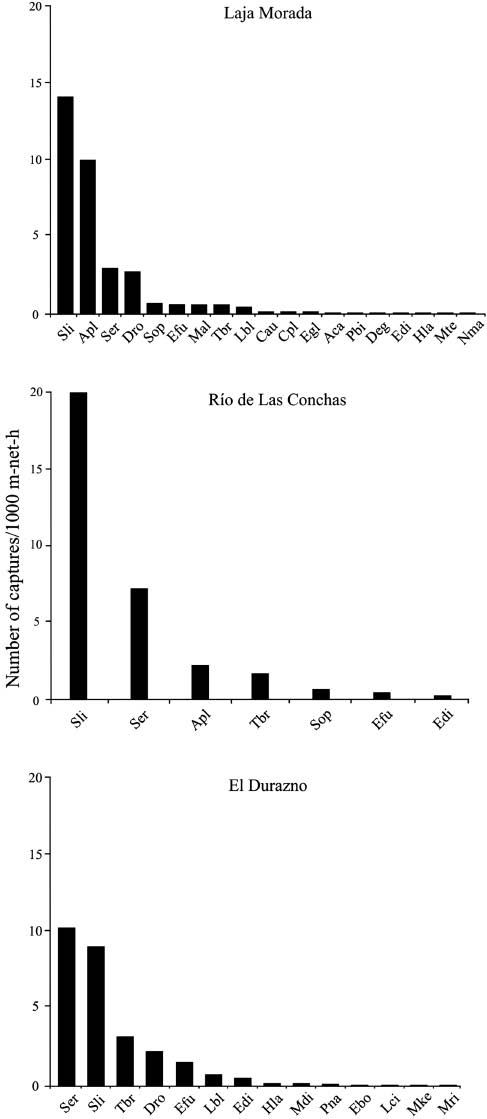

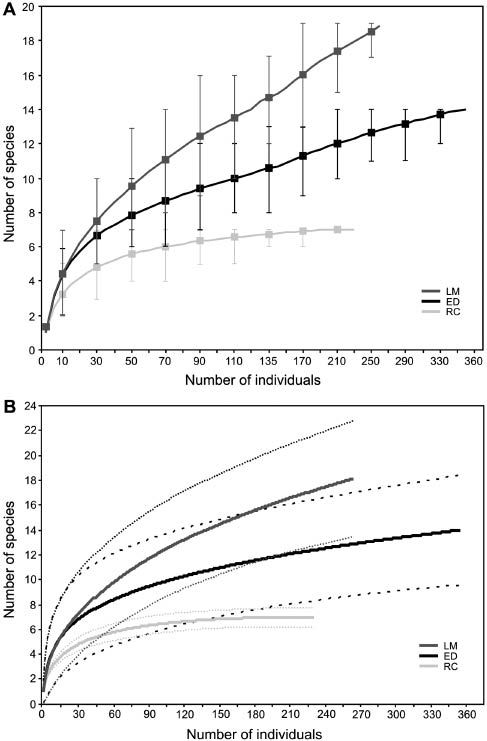

A total of 854 individuals were captured from all sites (265 at LM, 233 at RC and 356 at ED), with a total sampling effort of 27,138 m-net-h. Twenty-five species of Phyllostomidae, Vespertilionidae, and Molossidae families were identified (19 species at LM, 7 at RC, and 14 at ED; Table 1). Phyllostomidae accounted for 32.0% of the species and 84.3% of all individuals, whereas Vespertilionidae and Molossidae accounted for 40.0% and 28.0% of species and 7.7% and 8.0% individuals, respectively (Table 1). The frugivorous Sturnira lilium (É. Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1810) and Sturnira erythromos (Tschudi, 1844) were dominant, followed by Artibeus planirostris (Spix, 1823), Tadarida brasiliensis (I. Geoffrot St.-Hilaire, 1824), and Desmodus rotundus (É. Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1810) (Figure 2). Species accumulation curves only reached values close to the asymptote for RC, whereas in the remaining sites, the curves did not seem to stabilize with sampling effort (Figure 3A, B). Species richness differed among sites with samples of 230 individuals; however, only RC was significantly different according to the conservative analysis (Figure 3B). Seasonality variation in species richness and bats capture rations among sites or season were not significant different in any two-way ANOVA comparisons (p>0.05 in all cases).

Bat species sampled at three study sites in a subtropical rainforest of Argentina: relative abundance and respective number of captures (in brackets), family and subfamily are indicated for phyllostomid bats (following Wetterer et al. 2000), and trophic guild assignment (according to Bonaccorso 1979, Kalko et al. 1996, Schnitzler and Kalko 1998).

| Species | Laja Morada, % (n) | Río de las Conchas, % (n) | El Durazno, % (n) | Family and subfamily | Guild |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artibeus planirostris | 28.7 (76) | 6.9 (16) | Phyllostomidae/Stenodermatinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning frugivore/canopy | |

| Sturnira erythromos | 8.7 (23) | 22.3 (52) | 35.7 (127) | Phyllostomidae/Stenodermatinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning frugivore/understory |

| Sturnira lilium | 40.4 (107) | 61.4 (143) | 31.4 (112) | Phyllostomidae/Stenodermatinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning frugivore/understory |

| Sturnira oporaphilum | 2.3 (6) | 2.1 (5) | Phyllostomidae/Stenodermatinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning frugivore/understory | |

| Pygoderma bilabiatum | 0.4 (1) | Phyllostomidae/Stenodermatinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning frugivore/understory | ||

| Desmodus rotundus | 7.9 (21) | 7.9 (28) | Phyllostomidae/Desmodontinae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning hematophagous | |

| Chrotopterus auritus | 0.8 (2) | Phyllostomidae/Phyllostominae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning animalivore | ||

| Anoura caudifer | 0.4 (1) | Phyllostomidae/Glossophaginae | Highly cluttered space/gleaning nectarivore | ||

| Eptesicus furinalis | 1.9 (5) | 1.3 (3) | 5.6 (20) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore |

| Eptesicus diminutus | 0.4 (1) | 0.9 (2) | 2.0 (7) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore |

| Dasypterus ega | 0.4 (1) | Vespertilionidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Lasiurus blossevillii | 1.5 (4) | 2.8 (10) | Vespertilionidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | |

| Lasiurus cinereus | 0.3 (1) | Vespertilionidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Myotis albescens | 1.9 (5) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/trawling insectivore | ||

| Myotis dinellii | 0.8 (3) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Myotis keaysi | 0.3 (1) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Myotis riparius | 0.3 (1) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Histiotus laephotis | 0.4 (1) | 0.8 (3) | Vespertilionidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore | |

| Cynomops planirostris | 0.8 (2) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Eumops bonariensis | 0.3 (1) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Eumops glaucinus | 0.8 (2) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Nyctinomops macrotis | 0.4 (1) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Molossops temminckii | 0.4 (1) | Molossidae | Background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Promops nasutus | 0.6 (2) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore | ||

| Tadarida brasiliensis | 1.9 (5) | 5.2 (12) | 11.2 (40) | Molossidae | Uncluttered space/aerial insectivore |

| Captures | 265 | 233 | 356 | ||

| Species | 19 | 7 | 14 | ||

| % of Phyllostomidae | 89.4 | 92.6 | 75 | ||

| % of Vespertilionidae | 6.4 | 2.2 | 11.5 | ||

| % of Molossidae | 4.2 | 5.2 | 13.5 | ||

| Total number of guilds | 8 | 4 | 4 |

Relative abundance of each bat species in three sites of Argentina subtropical rainforests.

Total sample effort was 7538 m-net-h in Laja Morada; 7178 m-net-h in Río de Las Conchas; 12,422 m-net-h in El Durazno. Apl, Artibeus planirostris; Ser, Sturnira erythromos; Sli, S. lilium; Sop, Sturnira oporaphilum (Tschudi, 1844); Pbi, Pygoderma bilabiatum (Wagner, 1843); Dro, Desmodus rotundus; Cau, Chrotopterus auritus; Aca, Anoura caudifer; Efu, Eptesicus furinalis; Edi, Eptesicus diminutus (Osgood, 1915); Deg, Dasypterus ega (Gervais, 1856); Lbl, Lasiurus blossevillii (Lesson and Garnot, 1826); Lci, Lasiurus cinereus (Beauvois, 1796); Mal, Myotis albescens; Mdi, Myotis dinellii (Thomas, 1902); Mke, Myotis keaysi (J. A. Allen, 1914); Mri, Myotis riparius (Handley, 1960); Hla, Histiotus laephotis (Thomas, 1916); Cpl, Cynomops planirostris (Peters, 1865); Ebo, Eumops bonariensis (Peters, 1874); Egl, Eumops glaucinu (Wagner, 1843); Nma, Nyctinomops macrotis (Gray, 1839); Mte, Molossops temminckii (Burmeister, 1854); Pna, Promops nasutus (Spix, 1823); Tbr, Tadarida brasiliensis.

Individual-based rarefaction curves (solid lines) with 95% CIs (box or dashed lines) based in mist-netting captures for three sites in rainforests of Argentina.

(A) Traditional rarefactions analysis; note the values zero in the both extreme of CI. (B) Conservative analysis using an unconditional variance expression; CI is opened at the end of the curve. LM, Laja Morada; ED, El Durazno; RC, Río de Las Conchas.

Bat assemblages and guild structure

ANOSIM showed differences in specific compositions among assemblages when all sites and both seasons were considered; furthermore, LM and ED were also different when both seasons were considered (Table 2). According to SIMPER analysis, the main difference between LM and ED was determined by Artibeus planirostris, which was the species that made the biggest contribution due to its abundance in LM and its absence in ED; Tadarida brasiliensis, which was rare at LM and abundant at ED; and Myotis albescens (É Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1806), which was exclusive of LM (Table 3). Therefore, in order of importance, A. planirostris, Sturnira erythromos, Desmodus rotundus, T. brasiliensis, and Eptesicus furinalis (d’Orbingny and Gervais, 1847) made the strongest contributions to dissimilarity between LM and ED, accounting for <50% of the differences (Table 3).

ANOSIM on bat species and feeding guilds at three study sites in a subtropical rainforest of Argentina using a dissimilarity matrix based on Bray-Curtis similarity index.

| Factors | Species | Feeding guilds | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both seasons | Dry | Wet | Both seasons | Dry | Wet | |||||||

| R | p-Value | R | p-Value | R | p-Value | R | p-Value | R | p-Value | R | p-Value | |

| Between all sites | 0.173 | 0.043a | 0.278 | 0.331 | 0.143 | 0.217 | 0.231 | 0.038a | 0.056 | 0.389 | 0.306 | 0.106 |

| Laja Morada and El Durazno | 0.475 | 0.020a | 0.750 | 0.334 | -0.083 | 0.579 | 0.487 | 0.022a | 0.750 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.602 |

| Río Conchas and El Durazno | 0.112 | 0.191 | 0.000 | 0.661 | 0.407 | 0.206 | 0.180 | 0.151 | -0.250 | 1.000 | 0.630 | 0.110 |

| Río Conchas and Laja Morada | 0.031 | 0.373 | 0.500 | 0.345 | -0.167 | 0.729 | 0.119 | 0.226 | -0.250 | 0.689 | 0.167 | 0.413 |

Values for the R statistic, and their p value, are given for each factor of comparison.

aComparisons that were significant.

Contribution of each bat species and feeding guild to the dissimilarity among assemblages that resulted significant in the analysis of dissimilarity.

| El Durazno and Laja Morada | Avg. LM | Avg. ED | Avg. dissimilarity | % ac. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speciesa | ||||

| Artibeus planirostris | 9.18 | 0 | 9.28 (3.56) | 17.23 |

| Sturnira erythromos | 2.68 | 9.78 | 5.65 (1.75) | 27.71 |

| Desmodus rotundus | 2.73 | 1.50 | 5.33 (2.64) | 37.61 |

| Tadarida brasiliensis | 0.80 | 4.94 | 4.48 (1.39) | 45.93 |

| Eptesicus furinalis | 0.80 | 2.20 | 3.50 (1.37) | 52.42 |

| Myotis albescens | 0.65 | 0 | 3.08 (1.35) | 58.13 |

| Sturnira lilium | 14.05 | 9.20 | 2.82 (1.18) | 63.37 |

| Eptesicus diminutus | 0.10 | 0.80 | 2.39 (1.17) | 67.82 |

| Sturnira oporaphilum | 0.70 | 0 | 2.05 (0.92) | 71.62 |

| Feeding guildsb | ||||

| Gleaning frugivore/canopy | 9.18 | 0 | 13.28 (3.87) | 30.93 |

| Gleaning hematophagous | 2.73 | 1.50 | 7.60 (2.84) | 48.64 |

| Background/aerial insectivore | 1.2 | 3.54 | 6.20 (1.37) | 63.09 |

| Uncluttered/aerial insectivore | 2.45 | 6.32 | 5.72 (1.39) | 76.41 |

| Background/trawling insectivore | 0.65 | 0 | 4.53 (1.30) | 86.97 |

Average of abundance per site, average of dissimilarity and their standard deviation (indicated in brackets), and cumulative percentage are indicated for each species or guild. Avg. ED, average for El Durazno; Avg. LM, average for Laja Morada; % ac., accumulated percentage.

aOverall average of dissimilarity=53.87.

bOverall average of dissimilarity=42.93.

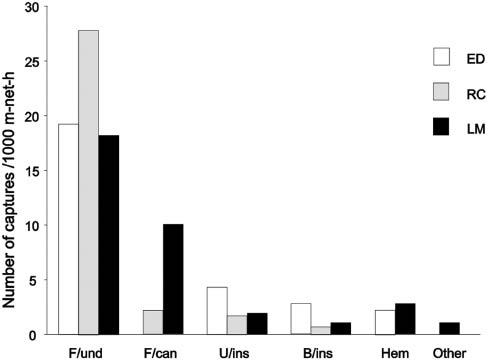

Eight feeding guilds were found at LM and four both at RC and ED (Table 1). Gleaning animalivores and nectarivores and cluttered-space/trawling insectivores were exclusive of LM, whereas the remaining sites had a subset of LM guilds described (Figure 4; Table 1). Guild structure was significantly different among sites mainly due to significant differences between LM and ED (Table 2); therefore, in seasonality analyses, none of the paired comparisons was significantly different. Dissimilarity between LM and ED was determined by the strongest contributions of gleaning frugivorous/canopy and gleaning hematophagous species (ca. 50% of dissimilarity, Table 3). Variations in guild abundance among sites or seasons were not significant in any of two-way ANOVA comparisons (p>0.05 in all cases; Figure 4).

Relative abundance plots for principal guilds of Argentina subtropical rainforest.

LM, Laja Morada; RC, Río de Las Conchas; ED, El Durazno. F/und, Frugivore understory; F/can, frugivore/canopy; U/ins, uncluttered space/aerial insectivore; B/ins, background-cluttered space/aerial insectivore; Hem, gleaning hematophagous.

Discussion

The species richness decreases from the north to the south as expected in these subtropical rainforests (see Barquez and Díaz 2001, Ojeda et al. 2008), but only is significantly lower in RC, which is in the center of the area. This suggests that latitude does not seem to have a significant impact on the richness of these assemblages, probably due to the relatively short geographic span of my study sites (ca. 4°; Figure 1). Interestingly, the low richness found in RC suggests that other variables not tested in this study can be relevant to determine local richness and structure in bat assemblages in the Yungas from Argentina (see below).

Abundance of bats obtained with mist net samples resemble results of other studies conducted elsewhere in the Neotropics (e.g., Simmons and Voss 1998, Kalko and Handley 2001, Aguirre 2002, Aguirre et al. 2003, Sampaio et al. 2003). Frugivorous species of the family Phyllostomid dominated subtropical assemblages in terms of bat captures, whereas the other guilds were less common, with the total number of individuals captured being low for most species (Figure 2). However, regarding specific composition, Yungas assemblages differ from those from tropical forests. For example, Yungas sites were dominated by frugivorous species of the genus Sturnira (one Andean genus; Velazco and Patterson 2013), whereas in tropical sites, the genus Carollia and Stenodermatini clade (see Wetterer et al. 2000) are dominant, both in terms of number of species and individuals. In addition, Vespertilionidae and Molossidae families contribute with many species, whereas in the tropical sites, Phyllostomidae is the family that accounts for the greatest richness (e.g., Simmons and Voss 1998, Estrada and Coates-Estrada 2002, Sampaio et al. 2003).

In the Yungas, guild structure showed changes among assemblages but not among seasons. Accordingly, seasonality in annual rainfall did not seem to influence bat captures in the study sites. However, a high variation in assemblage structure over time has been observed in other Neotropical sites (e.g., Aguirre et al. 2003, Mello 2009). In Atlantic forests, Mello (2009) found that guild structure of Phyllostomid bats changes across months or years and that some guilds exhibit higher abundance during some months of the rainy or dry season. In seasonal forests such as those of Argentina, important resources such as arthropods and fruits have strong temporal variations (Pearson and Derr 1986, Malizia 2001), which can affect the abundance of some guilds, such as frugivorous ones (see Sánchez et al. 2012a). Altogether, these lines of evidences suggest that bat assemblages of Argentina would vary over time. Hence, further studies involving longer sampling periods are necessary to test this assumption. Moreover, the strong change found in guild structure among sites can be linked to changes in β diversity and to latitudinal gradient in species richness, which generate a lack of species with tropical filiations, such as Artibeus planirostris, Anoura caudifer (É. Geoffroy St.-Hilaire, 1818), and Myotis albescens (see Gardner 2007), suggesting that both species turnover and lack of species have a great importance in the functional structure of guilds in these assemblages.

Low richness in RC and rareness or absence of some species in the samples can result from several factors. Availability of appropriate roosting sites, resource availability, or environmental conditions may influence the distribution, activity, and abundance of many species (Simmons and Voss 1998, Kalko and Handley 2001, Ramos Pereira et al. 2010, Stevens 2013); for example, in temperate regions, the presence of suitable roosting sites is determinant for the reproductive success of females and for overwinter survival of juveniles (Willis and Brigham 2005). Moreover, roosting in crevices is a prevalent feature of molossid and vespertilionid bats (Kunz 1982). In LM and ED, there are large and vertical cliffs that can provide many roosting sites, but there are no cliffs in the immediate vicinity of RC; this could explain the poor representation of insectivorous species in RC and their low richness. Interestingly, the most abundant insectivorous species in RC was Tadarida brasiliensis. This bat may fly 50 km or more to reach foraging areas (Wilkins 1989); hence, availability of roosting sites at a small scale, i.e., a few hectares, should not be a limiting factor for this species. Because flight is a very expensive type of locomotion (Norberg 1995), resource availability may limit bat activity; for example, frugivorous bats reduce their foraging activity to preserve energy during periods of food scarcity (Ramos Pereira et al. 2010). Climatic conditions may be determinant of abundance or presence of some species; for example, temperature range, maximum temperature of the warmest month and annual mean temperature determine the altitudinal distributions and abundances of Sturnira lilium and S. erythromos in the Yungas (Sánchez and Giannini 2014). Temperature seasonality is important in determining the latitudinal richness of Phyllostomid bats in the Atlantic forest (Stevens 2013). Therefore, in the Yungas these factors could determine the vagility or lack of some species and by the way the local richness and structure of these assemblages. In addition, some species such as Chrotopterus auritus (Peters, 1856) (a top predator) or gleaning insectivores are intrinsically rare in the sample because of their roosting site requirements, sedentary feeding mode, food preferences, small home range, specific habitat, or low population levels (Kalko and Handley 2001). Lastly, although in this study mist netting was carried out under the most favorable circumstances, due to the high representation of aerial insectivorous bats, sampling method with nets are biased toward one part of bat fauna; therefore, additional methods such as acoustic sampling are mandatory to enhance the knowledge of these assemblages.

In conclusion, the general structure in various subtropical bat assemblages resembles those of tropical assemblages in terms of the importance of some species, guilds, and the patterns of specific abundance. However, subtropical assemblages differed from tropical ones due to the dominance of one Andean bat genus and to the low number of Phyllostomidae species and a high contribution to richness of two insectivorous families. Seasonality does not appear to be determinant in assemblage structure and capture frequencies, whereas other variables, such as β diversity and latitudinal gradients in species richness, are determinant of guild structure. Moreover, other variables such as local availability of roosting sites and resource availability, climatic conditions, and characteristics of each species could be important to determine local richness and structure of these assemblages.

Acknowledgments

I especially thank C. Bracamonte, L. Fikdamir, D. Flores, N. Giannini, L. Krapovickas, M. Morales, G. Rodriguez, M. Sandoval, V. Segura, O. Varela, and W. Villafañes (El Alma) for their help in the field. Mariano Ordano, Leticia Moyers, and two anonymous reviewers significantly improved the scope and quality of the manuscript. Justo J. Correa and B. Maximiliano allowed me to work in Laja Morada (Finca Las Capillas) and El Durazno, respectively. The study was supported by Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT), Argentina.

References

Aguirre, L.F. 2002. Structure of a Neotropical savanna bat community. J. Mammal. 83: 775–784.10.1644/1545-1542(2002)083<0775:SOANSB>2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

Aguirre, L.F., L. Lens, R. van Damme and E. Matthysen. 2003. Consistency and variation in the bat assemblages inhabiting two forest islands within a Neotropical savanna in Bolivia. J. Trop. Ecol. 19: 367–374.10.1017/S0266467403003419Suche in Google Scholar

Barquez, R.M. and M.M. Díaz. 2001. Bats of the argentine Yungas: a systematic and distributional analysis. Acta Zool. Mex. (n.s.) 82: 29–81.10.21829/azm.2001.82821865Suche in Google Scholar

Barquez, R.M., M.A. Mares and J.K. Braun. 1999. The bats of Argentina. Texas Tech University and Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Oklahoma City, Norman, OK. pp. 275.Suche in Google Scholar

Barquez, R.M., M.M. Díaz and R.A. Ojeda. 2006. Mamíferos de Argentina: sistemática y distribución. Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos (SAREM), Mendoza, Argentina. pp. 357.Suche in Google Scholar

Barquez, R.M., M.N. Carbajal, M. Failla and M.M. Díaz. 2013. New distributional records for bats of the Argentine Patagonia and the southernmost known record for a molossid bat in the world. Mammalia 77: 119–126.10.1515/mammalia-2012-0053Suche in Google Scholar

Bonaccorso, F.J. 1979. Foraging and reproductive ecology in a Panamanian bats community. Bull. Florida St. Mus. Biol. Sci. 24: 359–408.Suche in Google Scholar

Bracamonte, J.C. 2010. Murciélagos de bosque montano del Parquet Provincial Potrero de Yala, Jujuy, Argentina. Mastozool. Neotrop. 17: 361–366.Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, A.D., H.R. Grau, L.R. Malizia and A. Grau. 2001. Argentina. In: (M. Kappelle and A.D. Brown, eds.) Bosques nublados del Neotrópico. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, INBio, Santo Domingo de Heredia, Heredia. pp. 623–659.Suche in Google Scholar

Cabrera, A.L. 1976. Regiones fitogeográficas Argentinas. Enciclopedia Argentina de agricultura y jardinería, segunda edición, Tomo II, Editorial ACME, Buenos Aires, Argentina. pp. 85.Suche in Google Scholar

Clarke, K.R. 1993. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 18: 117–143.10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.xSuche in Google Scholar

Clarke, K.R. and R.N. Gorley. 2001. Primer v5: user manual/tutorial. Primer-E, Plymouth, UK. pp. 91. http://www.primer-e.com/.Suche in Google Scholar

Colwell, R.K. 2013. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 9. http://purl.oclc.org/estimates.Suche in Google Scholar

Colwell, R.K., A. Chao, N.J. Gotelli, S. Lin, C.X. Mao, R.L. Chazdon and J.T. Longino. 2012. Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. J. Plant Ecol. 5: 3–21.Suche in Google Scholar

Di Bitetti, M.S., G. Placci and L.A. Dietz. 2003. A biodiversity vision for the upper Paraná Atlantic Forest Ecoregion: designing a biodiversity conservation landscape and setting priorities for conservation action. World Wildlife Fund, Washington, DC. pp. 116.Suche in Google Scholar

Estrada, A. and R. Coates-Estrada. 2002. Bats in continuous forest, forest fragments and in an agricultural mosaic habitat-island at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Biol. Conserv. 103: 237–245.10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00135-5Suche in Google Scholar

Fauth, J.E., J. Bernardo, M. Camara, W.J. Resetarits Jr., J. Van Buskirk and S.A. McCollum. 1996. Simplifying the jargon of community ecology: a conceptual approach. Am. Nat. 147: 282–286.10.1086/285850Suche in Google Scholar

Gardner, A.L. 2007. Order Chiroptera Blumenbach, 1779. In: (A.L. Gardner, ed.) Mammals of South America, volume 1, marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, and London, UK. pp. 187–484.Suche in Google Scholar

Giannini, N.P. and E.K.V. Kalko. 2005. The guild structure of animalivorous leaf-nosed bats of Barro Colorado Island, Panama, revisited. Acta Chiropterol. 7: 131–146.10.3161/1733-5329(2005)7[131:TGSOAL]2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

Gotelli, N.J. and G.L. Entsminger. 2004. EcoSim: null models software for ecology. Version 7.0. Acquired Intelligence Inc. & Kesey-Bear, Jericho, VT. http://www.uvm.edu/∼ngotelli/EcoSim/EcoSim.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Hueck, K. 1978. Los Bosques de Sudamérica. GTZ, Eschborn, Germany. pp. 476.Suche in Google Scholar

Hunzinger, H. 1995. La precipitación horizontal: su importancia para el bosque y a nivel de cuencas en la Sierra de San Javier, Tucumán, Argentina. In: (A.D. Brown and H.R. Grau, eds.) Investigación, conservación y desarrollo en selvas subtropicales de montaña. Laboratorio de Investigaciones Ecológicas de las Yungas, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina. pp. 53–58.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalka, M.B., A.R. Smith and E.K.V. Kalko. 2008. Bats limit arthropods and herbivory in a tropical forest. Science 320: 71.10.1126/science.1153352Suche in Google Scholar

Kalko, E.K.V. and C.O. Handley Jr. 2001. Neotropical bats in the canopy: diversity, community structure, and implications for conservation. Plant Ecol. 153: 319–333.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalko, E.K.V., C.O. Handley Jr. and D. Handley. 1996. Organization, diversity, and long-term dynamics of a Neotropical bat community. In: (M. Cody and J. Smallwood, eds.) Long-term studies in vertebrate communities. Academic Press, Los Angeles, CA. pp. 503–553.Suche in Google Scholar

Kunz, T.H. 1982. Roosting ecology of bats. In (T.H. Kunz, ed.) Ecology of bats. Plenum Press, New York, NY. pp. 425.Suche in Google Scholar

Kunz, T.H. and S. Parsons. 2009. Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats, second edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. pp. 920.Suche in Google Scholar

Kunz, T.K., E.B. de Torrez, D. Bauer, T. Lobova and T.H. Fleming. 2011. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1223: 1–38.10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06004.xSuche in Google Scholar

Lobova, T.A., C.K. Geiselman and S.A. Moris. 2009. Seed dispersal by bats in the Neotropics. Mem. NY Bot. Gard. 101: 1–471.Suche in Google Scholar

Malizia, L.R. 2001. Seasonal fluctuations of birds, fruits, and flowers in a subtropical forest of Argentina. Condor 103: 45–61.Suche in Google Scholar

Mello, M.A.R. 2009. Temporal variation in the organization of a Neotropical assemblage of leaf-nosed bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Oecol. 35: 280–286.10.1016/j.actao.2008.11.008Suche in Google Scholar

Minetti, J.L., M.E. Bobba and C. Hernández. 2005. Régimen espacial de temperaturas en el Noroeste de Argentina. In: (J.L. Minetti, ed.) El Clima del Noroeste Argentino Laboratorio Climatológico Sudamericano (LCS). Editorial Magna, Buenos Aires, Argentina. pp. 141–161.Suche in Google Scholar

Muscarella, R. and T.H. Fleming. 2007. The role of frugivorous bats in tropical forest succession. Biol. Rev. 82: 537–590.10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00026.xSuche in Google Scholar

Norberg, U.M. 1995. How a long tail and changes in mass and wing shape affect the cost for flight in animals. Funct. Ecol. 9: 48–54.10.2307/2390089Suche in Google Scholar

Ojeda, A.O., R.M. Barquez, J. Stadler and R. Brandl. 2008. Decline of mammal species diversity along the Yungas forest of Argentina. Biotropica 40: 515–521.10.1111/j.1744-7429.2008.00401.xSuche in Google Scholar

Pearson, D.L. and J.A. Derr. 1986. Seasonal patterns of lowland forest floor arthropod abundance in Southeastern Perú. Biotropica 18: 244–256.10.2307/2388493Suche in Google Scholar

R Development Core Team. 2013. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://cran.r-project.org.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramos Pereira, M.J., J.T. Marques and J.M. Palmeirim. 2010. Ecological responses of frugivorous bats to seasonal fluctuation in fruit availability in Amazonian forests. Biotropica 6: 680–687.10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00635.xSuche in Google Scholar

Sampaio, E., E.K.V. Kalko, E. Bernard, B. Rodríquez-Herrrera and C.O. Handley Jr. 2003. A biodiversity assessment of bats (Chiroptera) in a tropical lowland rainforest of central Amazonia, including methodological and conservation considerations. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 38: 17–31.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, M.S. 2011. Interacción entre murciélagos frugívoros y plantas en las selvas subtropicales de Argentina. PhD dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina. pp. 217.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, M.S. and M.P. Giannini. 2014. Altitudinal patterns in two syntopic species of Sturnira (Mammalia: Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in the montane rain forests of Argentina. Biotropica 46: 1–5.10.1111/btp.12082Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, M.S., L.V. Carrizo, N.P. Giannini and R.M. Barquez. 2012a. Seasonal patterns in the diet of frugivorous bats in the subtropical rainforests of Argentina. Mammalia 76: 269–275.10.1515/mammalia-2011-0059Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, M.S., N.P. Giannini and R.M. Barquez. 2012b. Bat frugivory in two subtropical rain forests of Northern Argentina: testing hypotheses of fruit selection in the Neotropics. Mammal. Biol. 77: 22–31.10.1016/j.mambio.2011.06.002Suche in Google Scholar

Sandoval, M.L., M.S. Sánchez and R.M. Barquez. 2010a. Mammalia, Chiroptera Blumenbach, 1779: new locality records, filling gaps, and geographic distribution maps from Northern Argentina. Check List 6: 64–70.Suche in Google Scholar

Sandoval, M.L., C.A. Szumik and R.M. Barquez. 2010b. Bats and marsupial as indicators of endemism in the Yungas forest of Argentina. Zool. Res. 31: 633–644.Suche in Google Scholar

Schnitzler, H.U. and E.K.V. Kalko. 1998. How echolocating bats search for food. In: (T.H. Kunz and P.A. Racey, eds.) Bats: phylogeny, morphology, echolocation, and conservation biology. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. pp. 183–196.Suche in Google Scholar

Simmons, N.B. and R.S. Voss. 1998. The mammals of Paracou, French Guiana: a Neotropical lowland rainforest fauna. Part 1. Bats. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 237: 1–219.Suche in Google Scholar

Stevens, R.D. 2013. Gradients of bat diversity in Atlantic forest of South America: environmental seasonality, sampling effort and spatial autocorrelation. Biotropica 45: 764–770.Suche in Google Scholar

Udrizar Sauthier, D.E., P. Teta, A.E. Formoso, A. Bernardis, P. Wallace and U.F.J. Pardiñas. 2013. Bats at the end of the world: new distributional data and fossil records from Patagonia, Argentina. Mammalia 77: 307–315.10.1515/mammalia-2012-0085Suche in Google Scholar

Velazco, P.M. and B.D. Patterson. 2013. Diversification of the yellow-shouldered bats, Genus Sturnira (Chiroptera, Phyllostominae), in the New World Tropics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68: 683–698.Suche in Google Scholar

Weber, M.M., J.L. Steindorff de Arruda, B.O. Azambuja, V.L. Camilatti and N.C. Cáceres. 2011. Resources partitioning in a fruit bat community of the southern Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Mammalia 75: 217–225.Suche in Google Scholar

Wetterer, A.L., M.V. Rockman and N.B. Simmons. 2000. Phylogeny of phyllostomid bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera): data from diverse morphological systems, sex chromosomes, and restriction sites. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 248: 1–248.10.1206/0003-0090(2000)248<0001:POPBMC>2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

Wilkins, K.T. 1989. Tadarida brasiliensis. Mamm. Species 331: 1–10.10.2307/3504148Suche in Google Scholar

Willis, C.K.R. and R.M. Brigham. 2005. Physiological and ecological aspects of roost selection by reproductive female hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus). J. Mammal. 86: 85–94.10.1644/1545-1542(2005)086<0085:PAEAOR>2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Studies

- Summer temperature and precipitation govern bat diversity at northern latitudes in Norway

- Structure of three subtropical bat assemblages (Chiroptera) in the Andean rainforests of Argentina

- Morphology, genetics and echolocation calls of the genus Kerivoula (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae: Kerivoulinae) in Thailand

- Status and population structure of a hunted population of Marco Polo Argali Ovis ammon polii (Cetartiodactyla, Bovidae) in Southeastern Tajikistan

- Habitat use of Himalayan grey goral in relation to livestock grazing in Machiara National Park, Pakistan

- Characterization and selection of microhabitat of Microcavia australis (Rodentia: Caviidae): first data in a rocky habitat in the hyperarid Monte Desert of Argentina

- Pregastric and caecal fermentation pattern in Syrian hamsters

- Short Notes

- Barn owl pellets collected in coastal savannas yield two additional species of small mammals for French Guiana

- Wiedomys cerradensis (Gonçalves, Almeida, Bonvicino, 2003) (Rodentia, Cricetidae): first record from the state of Maranhão, Brazil

- Morpho-anatomical characteristics of Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata) from Potohar Plateau, Pakistan

- First confirmed records of two bat species for Iraq: Rhinolophus euryale and Myotis emarginatus (Chiroptera)

- An efficient timing device to record activity patterns of small mammals in the field

- First record of Leontopithecus chrysopygus (Primates: Callitrichidae) in Carlos Botelho State Park, São Miguel Arcanjo, São Paulo, Brazil

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Studies

- Summer temperature and precipitation govern bat diversity at northern latitudes in Norway

- Structure of three subtropical bat assemblages (Chiroptera) in the Andean rainforests of Argentina

- Morphology, genetics and echolocation calls of the genus Kerivoula (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae: Kerivoulinae) in Thailand

- Status and population structure of a hunted population of Marco Polo Argali Ovis ammon polii (Cetartiodactyla, Bovidae) in Southeastern Tajikistan

- Habitat use of Himalayan grey goral in relation to livestock grazing in Machiara National Park, Pakistan

- Characterization and selection of microhabitat of Microcavia australis (Rodentia: Caviidae): first data in a rocky habitat in the hyperarid Monte Desert of Argentina

- Pregastric and caecal fermentation pattern in Syrian hamsters

- Short Notes

- Barn owl pellets collected in coastal savannas yield two additional species of small mammals for French Guiana

- Wiedomys cerradensis (Gonçalves, Almeida, Bonvicino, 2003) (Rodentia, Cricetidae): first record from the state of Maranhão, Brazil

- Morpho-anatomical characteristics of Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata) from Potohar Plateau, Pakistan

- First confirmed records of two bat species for Iraq: Rhinolophus euryale and Myotis emarginatus (Chiroptera)

- An efficient timing device to record activity patterns of small mammals in the field

- First record of Leontopithecus chrysopygus (Primates: Callitrichidae) in Carlos Botelho State Park, São Miguel Arcanjo, São Paulo, Brazil