Abstract

The topic of echo answers is vastly understudied in typology, with descriptive grammars primarily addressing how questions are formed rather than how they are answered. This paper offers a cross-linguistic investigation into the accessibility of echo answering strategies, specifically focusing on affirmative echo answers to affirmative polar questions. Based on questionnaire-elicited data from a convenience sample of 26 languages displaying echo answers, it has been found that, cross-linguistically, repeating the verbal predicate, either fully or partially, from the question, is the dominant echo answering strategy, and that there are two Echo-ability Hierarchies that impose constraints on which elements from the antecedent question can be repeated in an echo answer. After discussing the definition of echo answers, several related issues are also explored in detail, including the distinction between echo and repetitional answers, the polarity-based nature of the echo system, the range of accessible echo answering strategies across the world’s languages, the cross-linguistic gradience of pragmatic markedness in repetitional/echo answers, and potential explanations for the predicate-dominance in echo answering strategies.

1 Introduction

Sadock and Zwicky (1985) identify three types of answering systems to polar questions in the world’s languages: the yes/no system, the agree/disagree system, and the echo system. The first two systems concern yes/no particles whereas the echo system involves “repeating the verb of the question, with or without additional material that varies from language and language” (1985: 191).[1] The echo system is illustrated in (1) with Irish, where the affirmative answer is given by repeating the verb bhris ‘break’ from the question and the negative answer is formed by repeating the verb and adding the negative word níor.

| Irish (Jones 1999: 29)2 | |||||

| Q: | Ar | bhris | sé | an | fhuinneog? |

| q.pst | break | he | the | window? | |

| ‘Did he break the window?’ | |||||

| A1: | Bhris . | ||||

| break | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| A2: | Níor | bhris . | |||

| not | break | ||||

| ‘No.’ | |||||

- 2

Unless otherwise stated, all the examples presented in this paper are drawn from my own questionnaire-elicited dataset.

I henceforth call answers like those in (1) “echo answers”. Languages such as Irish, which allow the repetition of the verb as an answer, are referred to as “echo languages”. According to Holmberg (2016), nearly half of the 130 languages that he inspected employ an echo answering system. The crucial difference between echo languages and non-echo languages is that non-echo languages, such as English, cannot repeat the verb from the question as a usual answering strategy, as shown in (2).

| Q: | Did he break the window? |

| A: | *Break/*Broke. |

| Intended meaning: ‘Yes.’ |

The topic of the echo answering system is vastly understudied in typology, and descriptive grammars primarily focus on how questions are formed, not on how they are answered (Holmberg 2016; Manninen 2017). In-depth typological studies of the accessibility of echo answers include Simpson (2014) and Holmberg (2016). Simpson (2014) provides an in-depth exploration of echo answers to a specific type of polar question, namely, polar questions that include an adverb or adverbial adjunct. In this type of question, adverbs or adverbial adjuncts are often narrowly focused,[3] resulting in non-neutral polar questions. As a result, their answers do not conform to the type defined by Sadock and Zwicky (1985). Holmberg (2016) mentions in passing possible variations of echo answers across languages, for the purpose of providing evidence to support his ellipsis analysis from a Generative Grammar perspective. The present paper aims to fill this research gap by conducting a systematic investigation into echo answering strategies across a sample of 26 languages.

Although the typological studies devoted to the echo answering system are scarce, there are a few studies tackling all kinds of answering systems, for instance Leslau (1962), Pope (1976), Holmberg (2016), Moser (2018, 2019), and Enfield et al. (2019). In-depth investigations of echo answers have been conducted for quite a number of individual languages, most noticeably Welsh (Jones 1999), Portuguese (Harjunpää and Ostermann 2023; Martins 2023; Rosemeyer and Schwenter 2019; Santos 2009), and Finnish (Holmberg 2001; Sorjonen 2001a, 2001b; Vepsäläinen et al. 2023).

Apart from typology, answering systems have been approached in other areas, from the perspectives of syntax (e.g. Holmberg 2001, 2013, 2016; Jones 1999; Kramer and Rawlins 2011; Martins 2023; Santos 2009), semantics (e.g. Farkas and Bruce 2010; Farkas and Roelofsen 2019; Krifka 2001, 2013; Kramer and Rawlins 2011; Roelofsen and Donka 2015), pragmatics (e.g. Bolden 2016, 2023; Bolden et al. 2023a, 2023b; Enfield et al. 2010, 2019; Heritage and Raymond 2012; Raymond 2003; Sorjonen 2001a, 2001b; Stivers 2005, 2019; Vepsäläinen et al. 2023), experimental studies (e.g. Akiyama 1979, 1992; Claus et al. 2017; Dimroth et al. 2018; Li et al. 2016; Choi 1991, 2014; Maldonado and Culbertson 2023; Noveck et al. 2021; Schmerse et al. 2014; Vanek and Zhang 2023), and multimodality (González-Fuente et al. 2015; Li et al. 2016; Tubau et al. 2015).

However, most of these studies are devoted either to response particles, or to possible responses to all kinds of questions or statements, with echo answers being only one aspect of the research. Additionally, they treat echo answers indiscriminately, without distinguishing them from other similar types of responses. Any repetition of the antecedent initiation, whether from a question or a statement, is categorized as an echo answer. Presumably, languages, whether echo or non-echo, can produce repetitional responses under circumstances such as those in which: (i) one element in the question is in focus (3a); (ii) a nominal phrase acts as a minimal question seeking confirmation for the accuracy of information such as the name, time and place (Bolden 2023: 52) (3b); (iii) denial/contradiction (Jones 1999: 35) (3c); and (iv) a confirmation/agreement is made in response to a statement (3d) or to a question (3e), when the answerer wants to assert her epistemic authority over the information required (Heritage and Raymond 2012).[4]

| (Simpson 2014: 328) | |

| Q: | Did you greet everyone who came to the party? |

| A: | EVeryone! |

| A: | Let’s meet and discuss at 14:00. |

| B: | Today? |

| A: | Today. |

| (Jones 1999: 35) | |

| A: | That’s not funny. |

| B: | It IS. |

| A: | After so many years, you are still doing it. |

| B: | I’m still doing it. |

| (Heritage and Raymond 2012: 182) | |

| A: | Can I just put you on the machine? |

| B: | You can. |

The broad inclusion of all kinds of repetitional answers has the advantage of considering both echo and non-echo languages. However, this approach has the disadvantage of not sufficiently acknowledging echo languages for their conventional use of echo answers. This is particularly notable in languages like Latin and Scottish Gaelic, which lack equivalents for yes/no particles as in English and where echo answers are the most common answering strategy (Potočnik 2023 for Latin; Lachlan Mackenzie, pers. comm. for Scottish Gaelic). Similarly, in languages that use yes/no particles, such as Tzeltal, echo answers are far more frequent than particle answers, and in ǂAakhoe Haiǁom, echo answers occur nearly as frequently as particle answers (Enfield et al. 2019).

As mentioned earlier, Sadock and Zwicky (1985: 191) define the echo system as involving repeating the verb, with or without further material. König and Siemund give a similar generalization: “the echo system, … works by using part of the question − usually the verb − as the answer” (2007: 321). Thus, echo answers are assumed to be typically made up of the verb from the question, cross-linguistically.

This paper aims to discover whether the repetition of the verb from the question is the default echo answering strategy and what material, besides the verb, can occur in an echo answer. The following questions will be addressed: (i) what is the range of possible echo answering strategies across the world’s languages?; (ii) what are the constraints on which element(s) from the antecedent question can be repeated in an echo answer, both within individual languages and cross-linguistically?; and (iii) what are the potential explanations for the formation of echo answering strategies? Given the scarcity of relevant information in descriptive grammars and literature, I designed two questionnaires to obtain first-hand data. Drawing on data elicited from language specialists in a convenience sample of 26 echo languages, this paper focuses on affirmative echo answers to neutral affirmative polar questions.

The organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 defines echo answers, distinguishes between repetitional and echo answers, discusses the polarity-based nature of echo answers, and provides an overview of echo answering strategies attested in individual languages. Section 3 describes the methods used for data collection and sampling. Section 4 presents the results and proposes two Echo-ability Hierarchies. Section 5 is devoted to discussing the potential reasons for the formation of echo answering strategies, and Section 6 concludes with a summary of the findings and suggestions for future research.

2 Echo answers: definition, nature and types

2.1 Introduction

When Sadock and Zwicky (1985) talk about short answers to yes/no questions, their classification concerns answering systems, not languages. No definition of “echo language” or “echo answer” is given. It seems that they do not confine echo answers to languages with an echo system as they consider the accompanying answer it is in (4) as an echo answer in English.

| (Sadock and Zwicky 1985: 191) | |

| Q: | Isn’t it raining? |

| A: | Yes, it is . |

In the literature, if an answer includes any repeated element from the question, it is referred to as a “repetitional answer”[5] or “repeat” (e.g., Enfield et al. 2019; Bolden et al. 2023b; Heritage and Raymond 2012; Sorjonen 2001b). Sometimes echo answers are differentiated from other types of repetitional answers by using terms such as “verb-echo answers” (Holmberg 2016), “echo responsives” (Jones 1999), “verb repeat” (Hakulinen and Sorjonen 2009), and “verbal answers” (Simpson 2014). As will be shown in Section 2.4, an echo system is not confined to using verbs as short answers. Defining echo answers as solely related to verbs may therefore not be entirely accurate. Of the 130 languages surveyed by Holmberg (2016) on answering systems, 62 languages use an echo system. To acknowledge this typological difference and to be in line with the term “echo” given by Sadock and Zwicky (1985), I differentiate echo answers from repetitional answers. Echo answers are a typologically distinct subtype of repetitional answers. Repetitional answers are defined in a broad sense: the term refers to any kind of repeated response; whereas echo answers are defined in a narrow sense, referring to repetitional answers to neutral polar questions that are present in languages such as Irish as in (1) above, yet not present in languages such as English as in (2).[6] Here neutral polar questions refer to yes/no questions, in which the whole proposition is questioned and there is no narrowly focused element other than the verb, if present. The differences in illocution between repetitional answers and echo answers will be explored in detail in Section 2.2. The polarity-based nature of the echo system will be discussed in Section 2.3. Section 2.4 will give an overview of possible echo answering strategies attested in individual languages.

2.2 Repetitional answers, echo answers and illocution

In this section, I further discuss the differences between echo answers and repetitional answers, based on the illocutions in which they can occur.

As illustrated in (3) above, repetitional answers can occur in contexts where certain pragmatic effects are involved, e.g., focus, denial, agreement, etc. Additionally, beyond polar questions, repetitional answers can occur in response to other types of illocutions: statements (5a); declarative questions (5b); alternative questions (5c); tag questions (5d); and even imperatives (5e). These kinds of repetitional answers are either used to achieve certain pragmatic effects (contradiction (5a), confirmation (5b), (5d), reassurance (5e)), or are a conventionalized way to respond, given the nature of the question type, as illustrated in (5c). Most likely, languages, whether echo or non-echo, do not differ significantly in this type of repetitional strategy.

| Statements | |

| A: | You don’t like my cooking. |

| B: | I DO. |

| Declarative questions | |||

| Spanish (Raymond 2015: 61) | |||

| A: | Lo | están | renovando? |

| it | are.3pl | renovating | |

| ‘They’re renovating it?’ | |||

| B: | Lo | están | renovando |

| it | are.3 pl | renovating | |

| ‘They’re renovating it.’ | |||

| Alternative questions | |||||

| German (Hella Olbertz pers. comm.) | |||||

| A: | Möchtest | du | Kaffee | oder | Tee? |

| want.pst.sbjv.2sg | you.informal | coffee | or | tea | |

| ‘Would you like coffee or tea?’ | |||||

| B: | Kaffee | bitte. | |||

| coffee | please | ||||

| ‘Coffee, please.’ | |||||

| Tag questions | ||||||||

| Japanese (Hayashi 2010: 2700) | ||||||||

| A: | demo | are | mukashi | wa, | aya-anna | no | hayatta | desho? |

| but | that | old.times | top | such | lk | was.popular | cop | |

| ‘But that type (of clothes) was popular a long time ago, right?’ | ||||||||

| B: | Hayatt(a). | |||||||

| was.popular | ||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||||

| Imperatives | ||||

| Italian (Riccardo Giomi pers. comm.) | ||||

| A: | Vai | subito | a | letto! |

| go.imp | immediately | to | bed | |

| ‘Go to bed immediately.’ | ||||

| B: | Vado. | |||

| go.1sg | ||||

| ‘OK.’ | ||||

In contrast, echo answers are limited to responses to polar questions, for the reason that echoing an element from the polar question is not a commonly available strategy in many languages.[7] I follow Sorjonen (2001a) in distinguishing between polar questions that seek information and those that seek confirmation. Information-seeking questions are a type of polar question where a questioner has no prior knowledge about the truth or falsity of the propositional content. The respondent is invited to affirm or disaffirm as in (6a). Confirmation-seeking questions are asked by a questioner who already holds certain knowledge or expectations about the answer and seeks confirmation, as in (6b).

| Did he phone you? |

| He still didn’t phone you? |

Echo answers are restricted to these two types of polar questions, as illustrated by the following examples in Mandarin Chinese (henceforth Chinese), an echo language. The questions in (7a) and (7b) look identical, yet they inquire about different information in two different contexts. In (7a), when John asks Mary whether she has been to the restaurant before, he has no knowledge about the truth status of the state-of-affairs that he inquires about. Hence, his question is seeking a new piece of information. However, in (7b), John has an assumption about whether Mary has been to the restaurant before based on the contextual evidence that Mary orders food without looking at the menu; hence John is seeking confirmation for this assumption. In response to both questions, the echo answer is used to affirm (7a) and to confirm (7b).

| Chinese (Yuan 2019: 51–52) |

| [Context: John and Mary want to find a place for dinner. When they pass by a restaurant called Green Leaf, John asks Mary if she has ever been to this restaurant, and Mary replies.] | |||||||

| John: | Ni | lai | guo | zhe | jia | can-ting | ma? |

| 2sg | come | exp | this | clf | restaurant | reinf | |

| ‘Have you been to this restaurant before?’ | |||||||

| Mary: | Lai | guo./ | *Shi | (de). | |||

| come | exp | yes | cert | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||

| [Context: John invites Mary to a restaurant called Green Leaf that he recently discovered for dinner. Mary orders her food without looking at the menu. John asks Mary if she has ever been to this restaurant, and Mary replies.] | |||||||

| John: | Ni | lai | guo | zhe | jia | can-ting | ma? |

| 2sg | come | exp | this | clf | restaurant | q | |

| ‘Have you been to this restaurant before?’ | |||||||

| Mary: | Lai | guo./ | Shi | (de). | |||

| come | exp | yes | cert | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||

Chinese has mixed answering systems: the agree/disagree system and the echo system.[8] The agree/disagree system uses the particles shi ‘yes’ and bu (shi) ‘no’. In response to questions, these particle answers, along with interjection-type answers such as en, wei, xing, hao, slightly outnumber repetitional answers in naturally occurring conversations (Wang 2021). However, there is a division of labor between them. As seen from (7a), particle answers are not acceptable in response to information-seeking polar questions, while they are acceptable in response to confirmation-seeking polar questions. In other words, in Chinese, information-seeking polar questions prefer echo answers. This preference is also reported to be dominant in other echo languages, such as Finnish (Sorjonen 2001b), Polish (Weidner 2023), and Brazilian Portuguese (Harjunpää and Ostermann 2023; Rosemeyer and Schwenter 2019). Enfield et al. (2019: 292) investigate polar answers in 14 languages and find that repetition-type answers show their “highest relative frequency in response to requests for new information”. Therefore, it seems that echo answers prototypically occur in response to information-seeking questions.

Nevertheless, as seen in (7b), echo answers can be available as a response to confirmation-seeking questions. In this kind of echo answers, there is a gradience of markedness in pragmatic meanings across echo languages. In some languages, such as Chinese, where both particle and echo answers are available, echo answers are more epistemically marked while in some other languages, such as Tzeltal, where echo answers are the default answering strategy (Brown 2010), they are not as epistemically marked. Response particles are anaphors (Krifka 2013) in the sense that they carry no inherent propositional content, which instead has to be recovered from the antecedent question, and they also accept the stance or attitude framed in that propositional content (Enfield and Sidnell 2015); in contrast, repetitional answers assert the propositional content in the way as if it were independent of the antecedent question, thereby claiming more epistemic authority over the information at issue (Heritage and Raymond 2012). For instance, in (7b), the particle answer shi de simply confirms or agrees with John’s assumption whereas the echo answer lai guo is more assertive, taking greater ownership over what is being said in the response, as lai guo can function as an independent sentence with its own propositional content, which is asserted by the speaker. Therefore, compared with particles answers, echo answers are more pragmatically marked in languages where both types of answers are common. This distinction is illustrated more clearly in the following Russian example (8). In response to Vara’s confirmation-seeking question ‘A thick one?’, Grandma confirms with an echo answer while simultaneously, Grandpa confirms with a particle answer. Grandma is the one who gives the instruction to draw a ‘big stick’, so she confirms that ‘thick’ is in fact what she meant by ‘big’, thus asserting her epistemic authority; on the other hand, Grandpa simply affirms the accuracy of Vara’s understanding (Bolden 2023).

| Russian (Bolden 2023: 55–57, adapted) | |||

| [Context: Grandma and Grandpa are teaching their grandchild Vara to draw. GMA: grandma, GPA: grandpa, VAR: Vara] | |||

| GMA: | Bal’shuju | palachku | risuj |

| big | stick.dim | draw.imp | |

| ‘Draw a big stick.’ | |||

| VAR: | Bal’shu?ju | (begins to draw, looking down) | |

| big | |||

| ‘A big one?’ | |||

| GMA: | Hm^mm | ||

| GPA: | Da | ||

| yes | |||

| ‘Yes’ | |||

| VAR: | T^o?lsten’kuju | (continues to draw, looking down) | |

| thick.dim | |||

| ‘A thick one?’ | |||

| GMA: | T[ olsten’kuju 9 | ||

| thick.dim | |||

| ‘A thick one’ | |||

| GPA: | [ Da | ||

| yes | |||

| ‘Yes’ | |||

| GPA: | Teper’ | smatri (takes Vara’s pencil) | |

| now | look | ||

| ‘Now look!’ (then draws part of a tree for Vara) | |||

- 9

The symbol “[” is used to indicate that Grandpa’s Da starts overlapping with the second sound in Grandma’s response Tolsten’kuju.

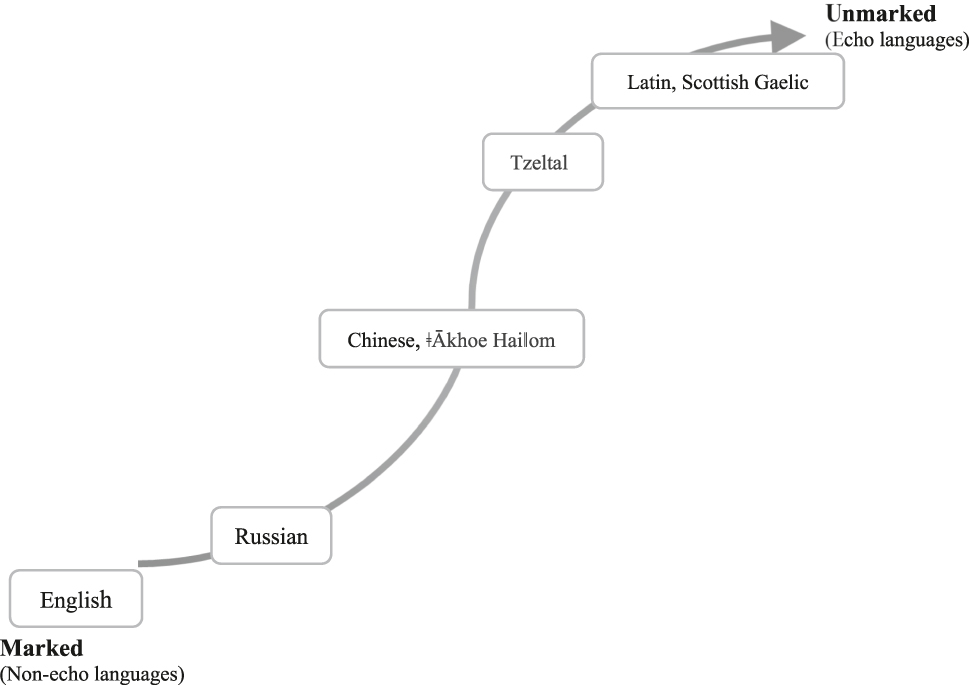

Enfield and Sidnell (2015), and Enfield et al. (2019) hypothesize that there is a “strong typological preference in the world’s languages for using interjection-type answers to polar questions” (2019: 301) and the repetition-type answers are “pragmatically marked and reserved for specific communicative purposes” (2019: 300). This is true in non-echo languages such as English, in which the use of repetition to confirm a polar question is not common in natural conversation (Enfield and Sidnell 2015: 138; Schegloff 1996). It is partly true for echo languages that have both answering options available for use in response to a confirmation-seeking question, such as Chinese, Russian (Bolden 2023), Finnish (Sorjonen 2001b), Polish (Weidner 2023), Estonian (Keevallik 2010), Brazilian Portuguese (Harjunpää and Ostermann 2023; Rosemeyer and Schwenter 2019), and Greek (Alvanoudi 2022). In these languages, echo answers occur much more frequently than in English, and thus they are generally less pragmatically marked than in languages like English. However, it is not true for Yurakaré (an isolate spoken in Bolivia; Gipper 2024) and for Mesoamerican languages such as Tzeltal, in which echo answers are the most frequent and default form for responses to polar questions, as shown by analyses of data from naturally occurring conversations (cf. Brown 2010: 2640; Brown et al. 2021) and repetitional answers do not impose epistemic authority or primacy as in languages such as English, Chinese, and Russian (Brown et al. 2021). The level of conventionalization of echo answers is even higher in languages such as Latin and Scottish Gaelic, in which there are no equivalents of yes/no words. Consequently, the frequency of echo answers in Latin and Scottish Gaelic is presumably higher than that in Tzeltal. In the languages that have echo answers as a default strategy, echo answers are least pragmatically marked. Hence, among the world’s languages, there is a spectrum of pragmatic markedness, with languages such as English on one end, languages such as Scottish Gaelic on the other, and others somewhere in between, as shown in Figure 1. There is a decrease of pragmatic markedness of repetitional or echo answers from non-echo to echo languages. Within each type of languages there is variation.

Gradience of pragmatic markedness of repetitional/echo answers in the world’s languages (this figure is just to illustrate roughly the spectrum of different degrees of pragmatic markedness. Only a few languages are included based on the findings in the literature, and there is no attempt to locate accurately every mentioned language on the axis. No doubt more quantitative analyses are needed to give a more fine-grained picture).

In this section, I have discussed the differences between echo answers and repetitional answers regarding illocution. Repetitional answers are not restricted to echo languages, and they have restriction on the illocutions that they can co-occur with. Echo answers have a strong tendency to occur as a response to an information-seeking polar question. When languages have both particle answers and echo answers available for use, they tend to carry different functions in response to confirmation-seeking questions. The more conventionalized an echo strategy is, the less pragmatically marked it is.

2.3 The polarity-based nature of echo answers

Apart from the echo system, the other two systems classified by Sadock and Zwicky (1985) are the yes/no system and the agree/disagree system. The former is also known as the ‘polarity-based’ system, as the particle yes indicates a positive polarity, while no indicates a negative polarity. Unlike the echo system, both the yes/no and agree/disagree systems use response particles to answer. The yes/no system uses yes/no particles, and the agree/disagree system uses agree/disagree particles. The difference between these response particles is particularly evident in how they answer a negative question with a negative bias (expecting a negative answer). If the polarity of particles like yes/no in English aligns with the polarity of the accompanying sentence answer, whether implicitly or explicitly expressed, or that of the antecedent question, then the language follows a polarity-based system. For example, in (9), the presence of ‘still’ explicitly indicates that the questioner expects a negative answer, based on evidence, e.g., that the answerer is still sitting in the kitchen. Confirmation is provided by using the negative particle no, which means ‘I haven’t’, thus aligning with the negative polarity of the question. Disconfirmation (contradiction), on the other hand, is conveyed by using the affirmative particle yes, meaning ‘I have’, thus dis-aligning with the negative polarity of the question. Hence, a polarity-based answering system functions by aligning the polarity of the answer with that of the preceding question.

| Q: | Have you still not been to the supermarket? (negatively biased) |

| A1: | No, (I haven’t.) |

| A2: | Yes, (I have.)10 |

- 10

It should be noted that a bare ‘yes’ answer to a negative question is partially ungrammatical and often creates ambiguity, as pointed out by Pope (1976), Kramer and Rawlins (2011), and Holmberg (2016).

However, in terms of polarity alignment, the opposite is true for an agree/disagree system, where the ‘no’ particle is used for disconfirmation while the ‘yes’ particle is used for confirmation. As in Japanese, in (10), the particle hai is used where English would use no, and the particle iie is used where English would use yes. This means that the polarity is misaligned between the particle and its accompanying answer, if expressed, and between the particle and the question. Therefore, the agree/disagree system is not based on polarity alignment. It is termed the “agree/disagree” system because the response particles are agree and disagree particles. As in Japanese, hai is always used to agree and iie is always to disagree, regardless of the polarity of the antecedent. For example, if the question in (10) is changed to an affirmative question, the agree particle hai, which indicates ‘I didn’t go’ in (10-A1), can still be employed to indicate a positive answer ‘I went’.

| Japanese (Kuno 1973: 273) | |||||||

| Q: | Kinoo | gakkoo | ni | ikimasen | desita | ka? | (negatively biased) |

| yesterday | school | to | go.not | did | q | ||

| ‘Did you not go to school yesterday?’ | |||||||

| A1: | Hai, | ikimasen | desita. | ||||

| yes | go.not | did | |||||

| ‘No, I did not go.’ | |||||||

| A2: | Iie, | ikimasita. | |||||

| no | went | ||||||

| ‘Yes, I did.’ | |||||||

Semantically, a yes/no (polar) question offers a selection from two alternatives which consist in the polar values of True/Not True (Dik 1997: 263). For instance, if the questioner’s expectation for a negative answer is disregarded, the yes/no question of (10) is semantically like the alternative question (11a). The answerer is expected to choose between two alternatives with opposing polar values. An affirmative answer is similar to (11b), while a negative answer is similar to (11c).

| Did you not go to school yesterday or did you go to school yesterday? |

| I went to school yesterday. |

| I did not go to school yesterday. |

In other words, the English no is semantically similar to (11c), while yes is semantically similar to (11b). However, in an agree/disagree system, the alternative question runs like (12a). The Japanese hai is semantically similar to (12b), while iie is semantically similar to (12c). Regardless of the polarity of the antecedent, hai always indicates ‘it is true’ while iie always indicates ‘it is not true’.

| Is it true that you didn’t go to school yesterday or is it not true that you didn’t go to school yesterday? |

| It’s true that I didn’t go to school yesterday. |

| It is not true that I didn’t go to school yesterday. |

The discussion above shows that the distinction between the yes/no system and the agree/disagree system lies in the different levels of polar values they address.

For a question like (10), a language with an echo system would confirm by repeating both the predicate and its negation, while it would disconfirm by repeating only the predicate, as illustrated by (13) in Chinese. Mei qu in (13-A1), consisting of the verb qu and the negator mei, is similar to the English response ‘No, (I didn’t.)’, while qu in (13-A2) is similar to ‘Yes, (I did).’

| Chinese | |||||

| Q: | ni | zuo-tian | mei | qu | xue-xiao? |

| you | yesterday | neg | go | school | |

| ‘Did you not go to school yesterday?’ | |||||

| A1: | Mei | qu . | |||

| neg | go | ||||

| ‘I didn’t.’ | |||||

| A2: | Qu | le. | |||

| go | pfv | ||||

| ‘I went.’ | |||||

Hence, echo answers also function by aligning/misaligning with the polarity of the antecedent question in the same way as yes/no particles in the yes/no system. In other words, echo answers, like yes/no particles, address the same level of polar values for the antecedent question. Therefore, the echo answering system is also polarity-based. The difference between the yes/no system and the echo system lies in how their answers are formed: one through the means of particles while the other through repetition.

However, it is not correct to claim that only the yes/no system and the echo system are polarity-based. The agree/disagree system also addresses polar values by directly concerning the truth status of the proposition expressed in the question, thus making it polarity-based as well. This is unsurprising, as all answering systems are framed by the nature of polar questions, which inquire about the polar values of the propositional content. Therefore, the term “polarity-based” is not useful for referring to just one type of the three answering systems.

2.4 Types of echo answers

According to Sadock and Zwicky, echo answers are made up of repetitions of the verb from the question, “with or without additional material” (1985: 191). It is unclear what they mean by “verb”. A verb may refer to a lexical verb, an auxiliary verb, or a copula. When a lexical verb functions as the predicate in a sentence, it may be morphologically marked for grammatical information such as tense or aspect, or it may appear bare, without any inflectional marking, as is the case in isolating languages. In this paper, the abbreviation “V” refers to a lexical verb, whether bare or inflected. “Auxiliary” refers to both auxiliary verbs and copulas, as copulas are considered a subtype of auxiliaries. This classification is because copulas only provide support for non-verbal predicates without contributing independent semantic content to the sentence, as evidenced by their non-obligatoriness (Dik 1987/2011, 1997; Hengeveld 1992). Predicates can be either verbal or non-verbal. Verbal predicates may consist of a single lexical verb, or a verbal complex that includes other elements besides the lexical verb, while non-verbal predicates are of various types, such as nominal, adjectival, adpositional, or possessive (Dik 1997). Unless otherwise specified, the term “predicate” in this paper refers to verbal predicates.

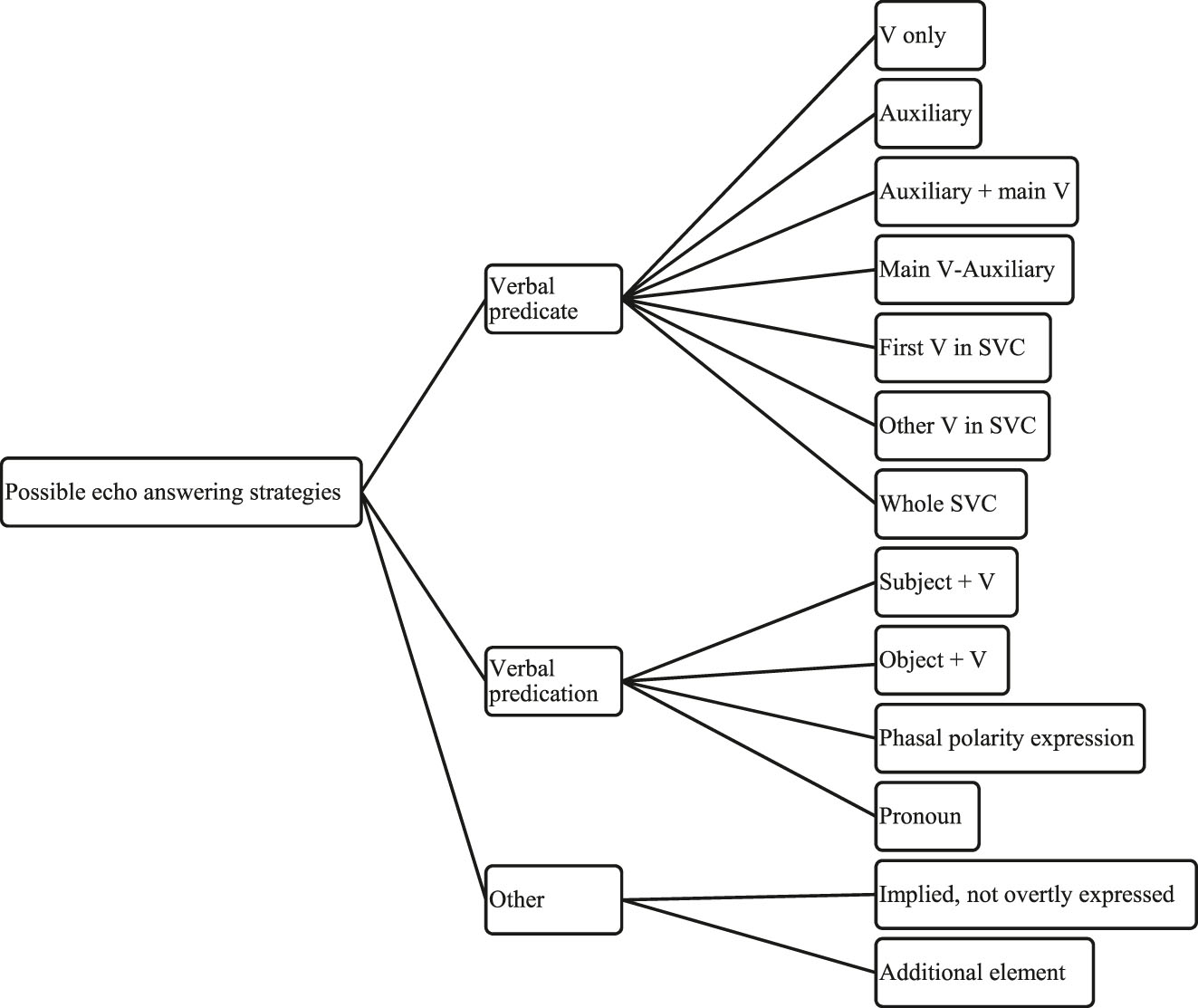

In this section, I will provide an overview of the types of possible echo answering strategies attested in individual languages, focusing on what kind of verbal material and/or additional material can serve as echo answers.[11] The summary is presented in Figure 2, and each type listed will be followed by detailed illustrations. It is important to note that the following discussion primarily addresses regular affirmative short answers (i.e., no special pragmatic effects are needed to validate the accessibility of a certain type of answer). As mentioned in Section 2.1, the polar questions involved are neutral affirmative ones.

An overview of possible echo answering strategies attested in individual languages.

A typical echo answer involves repeating the lexical verb, including its finiteness if applicable, from the antecedent to affirm, or repeating it with a negative word to disaffirm, as shown in (14). This strategy applies regardless of the transitivity status of the antecedent question.

| Czech (Jones 1999: 31) | ||

| Q: | Máte | radio? |

| have.prs.2pl | radio | |

| ‘Do you have a radio?’ | ||

| A1: | Máme . | |

| have. prs .1 pl | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||

| A2: | Nemáme. | |

| neg.have. prs .1 pl | ||

| ‘No.’ | ||

The finite marking on the verb is usually adapted in the answer. As seen in (14), the person marking is adapted into the first person if the question involves the second person. In rare cases, it may be directly copied, as in Brazilian Portuguese in (15).

| Brazilian Portuguese (Hengeveld and Mackenzie 2014: 223) | |||||

| Q: | Você | ligou | para | sua | mãe? |

| you | call- pst .pfv. 2sg | rec | poss.2sg | mother | |

| ‘Did you call your mother?’ | |||||

| A: | Ligou . | ||||

| call- pst. pfv. 2sg | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ (lit. “you called”) | |||||

However, when the question involves a third person, the person marking is always directly copied, as in (16).

| Tzeltal (Brown 2010: 2635) | ||||||||

| [Context: a person asks about the answerer’s father addressed as muk’ul jtatik.] | ||||||||

| Q: | kuxul-0 | to | wan | s-tukel | i | j-muk’ul | j-tatik | i? |

| be.alive-3sg .abs | still | part | 3erg-self | this | hon-big | hon-‘sir’ | deic | |

| ‘Big ‘sir’ (your father) is perhaps still alive?’ | ||||||||

| A: | Kuxul-0 . | |||||||

| be.alive-3sg .abs | ||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||||

Regarding tense marking, it is also directly copied, as in (14) and (15), yet it can also be adjusted as in (17a) in European Portuguese. Aspect marking is usually copied and repeated in the answer as in (17b).

| European Portuguese (Martins 2023: 436) | ||||

| Q: | Farás | isso | por | mim? |

| do-ind. fut -2sg | this | by | me | |

| ‘Will you do that for me?’ | ||||

| A1: | Faço . | |||

| do-ind. prs .1sg | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A2:? | Farei . | |||

| do-ind. fut -1sg | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| Chinese (Wei 2022: 113) | |||||||

| Q: | Ta | na | yi-fu | hui | jia | le | ma? |

| he | take | clothing | back | home | prf | reinf | |

| ‘Did he take (his) clothes and go back home?’ | |||||||

| A: | Na | le / | * Na | (guo). | |||

| take | prf | take | exp | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||

The verbal predicate in the antecedent question can be complex, consisting of a lexical verb as the main verb along with other elements that indicate tense, aspect, and modality, such as auxiliaries. Languages vary as to which part of the complex predicate can be repeated in an echo answer: the auxiliary alone (18a), the main verb without an auxiliary (18b), or both the auxiliary and the main verb (18c).

| Auxiliary alone: European Portuguese (Santos 2009: 15) | ||||||||||

| Q: | A | Eva | tinha | dado | o | livro | à | tia | de | manhã? |

| the | Eva | had | given | the | book | to+the | aunt | prep | morning | |

| ‘Eva had given the book to her aunt in the morning?’ | ||||||||||

| A: | Tinha [-]. | |||||||||

| had | ||||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||||||

| Main verb without auxiliary: Czech (Jones 1999: 32) | ||||

| Q: | Viděl | jsi | tu | hru? |

| see.pst | be.prs.2sg | det | game | |

| ‘Did you see the game?’ | ||||

| A: | Viděl | |||

| see.pst | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| Auxiliary and main verb: Breton (Jones 1999: 30) | ||||

| Q: | Ha | dont | a | reot ? |

| Q | come.inf | part | do.fut.2pl.aux | |

| ‘Will you come?’ | ||||

| A: | Dont | a | rin . | |

| come.inf | part | do.fut.1sg.aux | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

When the complex predicate involves a serial verb construction (concatenation of verbs without overt marking of subordination or coordination), the availability of echo answers is like that of the “auxiliary + verb” construction: the first verb (19a-A1), the whole verb series (19a-A2), or the second verb (19b).

| First verb or the whole verb serial: Chinese | |||||

| Q: | Ni | qu | kan | dian-ying | ma? |

| you | go | see | movie | reinf | |

| ‘Are you going to watch the movie?’ | |||||

| A1: | Qu . | ||||

| go | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| A2: | Qu | kan . | |||

| go | see | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| Second verb: Thai (Nitipong Pichetpan pers. comm.) | |||||

| Q: | ˈKʰun | ˈma | ˈkin | baˈmìi | ˈmǎy? |

| you | come.fut | eat | noodle | part | |

| ‘Are you going to eat (these) noodles?’ | |||||

| A: | ˈKin | ˈsî | |||

| eat | part | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

When the predicate in the question involves arguments, in some languages, the subject or the object can be repeated along with the verb as in (20).

| Finnish (Holmberg 2016: 112) | ||||

| Q: | Oletko | sinä | nähnyt | Marjan? |

| have-2sg-q | you | seen | Marja | |

| ‘Have you seen Marja?’ | ||||

| A: | Olen | minä | nähnyt. | |

| have | I | seen | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| Greek (Santos 2009: 62) | |||

| Q: | Agórases | to | vivlio? |

| bought.2sg | the | book | |

| ‘Did you buy the book?’ | |||

| A: | To | agórasa. | |

| it | bought | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

In Slovenian, the clitic object pronoun can even occur systematically alone to mean ‘yes’ as in (21).

| Slovenian (Dvořák 2007: 210) | |||

| Q: | A | mu | verjameš? |

| Q | cl.3.m.dat | believe.2 | |

| ‘Do you believe him?’ | |||

| A: | Mu | ||

| cl.3.m.dat | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

When phasal polarity expressions such as ‘already’ occur in the answer, be it an adverb or an aspect marker, they either occur alone as in (22a) and (22b), or along with the verb, even when they are not present in the antecedent question as in (22c).

| European Portuguese (Santos 2009: 59) | |||||

| Q: | Ele | já | encontrou | a | chave? |

| he | already | found.3sg | the | key | |

| ‘Has he already found the key?’ | |||||

| A: | Já . | ||||

| already | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| Semelai (Kruspe 2004: 327) | ||

| Q: | Lɒc | ca? |

| already | eat | |

| ‘(Have you) already eaten?’ | ||

| A: | Lɒc | |

| already | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||

| Vietnamese (Simpson 2014: 323) | |||||||

| Q: | Bạn | nhần | hai | lần | phải | không/ | chưa? 12 |

| friend | click | two | time | correct | neg | yet | |

| ‘You clicked twice, is that right/ Did you click twice yet?’ | |||||||

| A: | Nhần | rồi | |||||

| click | already.asp | ||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||

- 12

The slash used throughout this paper signifies ‘or’.

Sometimes, even a completive aspect particle can occur alone as in (23). This particle la in Tzeltal, in all other contexts a bound morpheme that cannot occur alone, functions alone as a yes answer.

| Tzeltal (Brown 2010: 2642) | ||||||

| Q: | La | y-ich’ | s-k’u’ | y-u’un-ik | ek’ | tz’in |

| compl | 3erg-get | 3erg-clothes | 3erg-reln-pl | too | part | |

| ‘They got their own (Tenejapan) clothes too then?’ | ||||||

| A: | La | |||||

| compl | ||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||

It has also been found that certain additional material that reinforces the meaning of the echo answer such as ‘indeed’ and ‘of course’ can be added as in (24).

| Latvian (Jones 1999: 34) | |||

| Q: | Vai | tu | paliksi? |

| q | you.sg | stay.2sg.fut | |

| ‘Are you staying?’ | |||

| A: | Palikšu | gan | |

| stay.1sg.fut | indeed | ||

| ‘I am indeed staying.’ | |||

The above are concerned with the polar questions in which everything is explicitly expressed. When it comes to a fragment polar question, i.e. certain elements, especially the predicate, are not overtly expressed, yet implied in the context, the unexpressed elements can still be recovered to form an echo answer as in (25). In (25a), the copula wyt ‘are’ and the verb cymryd ‘take’ are implied in the context, yet the copula auxiliary is recovered to indicate ‘yes’, much as it would be if every element of the question were overtly expressed.

| Welsh (Jones 1999: 110) | |||||

| Q: | ( Wyt | ti | ’n | cymryd) | siwgr? |

| are | you | prog | take | sugar | |

| ‘(Do you take) sugar?’ | |||||

| A: | Ydw / | Nac | ydw | ||

| am | neg | am | |||

| ‘Yes/No.’ | |||||

| European Portuguese (Martins 2023: 438) | |||

| [Context: B is showing A what he bought at the supermarket for their dinner party.] | |||

| A: | E | as | bebidas? |

| and | the | drinks | |

| ‘Did you buy the drinks? /What about the drinks?’ | |||

| B: | Comprei. | ||

| bought-1sg | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

To summarize, as shown in Figure 2, a variety of echoing strategies is available in echo languages. These strategies include: the lexical verb alone, with its finiteness if applicable; the auxiliary, with or without its main verb; the main verb without the auxiliary; the pronominal subject or pronominal object with the predicate; the personal pronoun; phasal polarity expressions such as ‘already’; reinforcing words alongside the usual echo answer; or recovered elements that are implied but not explicitly expressed in the context.

3 Data collection and method

In the previous section, I presented various types of echoing strategies attested in individual languages. Reference grammars often focus on questions and provide little information on answers, thus resulting in very limited available data. Hence, the relevant information was primarily gathered from research papers and books. Occasionally, a grammar book may include a few paragraphs or even a section on answering strategies for a specific language, but such discussions are limited to a few examples and do not cover the range of accessible answers presented in the previous section. On the Syntactic Structures of the World’s Languages (SSWL) website,[13] there used to be a database created by Anders Holmberg that provides information on answering strategies. Since my set of questions differs from those in the database, I had no choice but to consult language specialists to obtain first-hand data. To achieve this, I designed two questionnaires (see Supplementary Materials). The rationale for using two separate questionnaires is as follows: first, Questionnaire 1 is used to determine whether a language is an echo language.[14] If a language is identified as an echo language, Questionnaire 2 is then used to ask detailed questions about the types of echo answers, as illustrated in Section 2.4. Both questionnaires require both native speakers’ intuition and linguistic expertise, which complicated data collection. Since many of the languages initially surveyed are not echo languages, I ultimately obtained a convenience sample of 26 echo languages, as detailed in Table 1. Nevertheless, the sample encompasses languages from 11 language families, located in Eurasia, Africa and America. Table 1 provides details on the language families, the specific languages investigated, their geographic regions, Glottocodes, and the sources of information.

The language sample (while Section 2.4 primarily includes the data collected from the literature, the examples presented in Section 4 are taken from this sample. Names followed by a year indicate publication sources whereas names without a year refer to my informants).

| Language family | Language | Area | Glottocode | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afroasiatic: Semitic | Hebrew | Asia | hebr1245 | Nurit Dekel, Mira Ariel |

| Afroasiatic: Semitic | Amharic | Africa | amha1245 | Temesgen Haile |

| Afroasiatic: Berber | Berber | Africa | cent2194 | Khalid Mourigh |

| Austroasiatic: Vietic | Vietnamese | Asia | viet1252 | Thompson (1987), Nguyễn Minh Thư Hoàng, Kim Ngoc Quang, Thuan Tran |

| Austronesian: Malayo-Polynesian | Indonesian | Asia | indo1316 | Aone Engelenhoven |

| Dravidian: South Dravidian | Malayalam | Asia | mala1464 | Savithry Namboodiripad |

| Indo-European: Celtic | Scottish Gaelic | Europe | scot1245 | Lachlan Mackenzie |

| Indo-European: Celtic | Welsh | Europe | wels1263 | Jones (1999) |

| Indo-European: East Baltic | Latvian | Europe | latv1249 | Aleksandrs Gross |

| Indo-European: Hellenic | Greek | Europe | mode1248 | Joseph and Philippaki-Warburton (1987), Despoina Moysiadou, Kristina Gedgaudaite |

| Indo-European: Iranian | Persian | Asia | west2369 | Pegah Faghiri |

| Indo-European: Italic | Latin | Europe | lati1261 | Olga Spevak |

| Indo-European: Romance | European Portuguese | Europe | port1283 | Lachlan Mackenzie |

| Indo-European: Romance | Brazilian Portuguese | South America | port1283 | Marize Mattos Hattnher |

| Indo-European: Romance | Galician | Europe | gali1258 | Mercedes González Vázquez |

| Indo-European: Slavic | Bulgarian | Europe | bulg1262 | Margarita Gulian |

| Indo-European: Slavic | Croatian | Europe | Sout1528 | Lutz Lucic |

| Indo-European: Slavic | Russian | Eurasia | russ1263 | Egbert Fortuin, Olja Karmanova |

| Koreanic | Korean | Asia | kore1280 | Jeemin Park |

| Nilo-Saharan: Luo | Dholuo | Africa | luok1236 | Merceline Ochieng |

| Sino-Tibetan: Sinitic | Chinese | Asia | mand1415 | The author |

| Tai-Kadai: Northern Daic-Sek | Saek | Asia | saek1240 | Weijian Meng |

| Tai-Kadai: Central-Southwestern Thai | Thai | Asia | thai1261 | Yaisomanang (2012), Saranrat Kanlayakiti, Hnin Hnin Phyu, Nitipong Pichetpan |

| Turkic: Common Turkic | Turkish | Eurasia | nucl1301 | Beyza Sumer |

| Uralic: Finnic | Finnish | Europe | finn1318 | Holmberg (2001, 2016), Seppo Kittilä |

| Uralic: Ugric | Hungarian | Europe | hung1274 | István Kenesei |

4 The Echo-ability Hierarchies

4.1 Introduction

Section 2.4 provides an overview of echo strategies attested in individual languages. Based on these attested strategies, a survey was conducted across 26 languages to determine whether these strategies are available in each language and to investigate potential cross-linguistic constraints on the echo-ability of these strategies. It was found that languages share some strategies (Section 4.2) and vary in others (Section 4.3). There are two Echo-ability Hierarchies that impose constraints on which element(s) from the question can be repeated in an echo answer cross-linguistically (Section 4.3). Note that the elicited results are based on informants’ intuitions and may be subject to different judgments by different native speakers. On the other hand, intuition-based judgments are most probably concerned with the prototypical use of echo answers in a particular language.

4.2 Commonalities

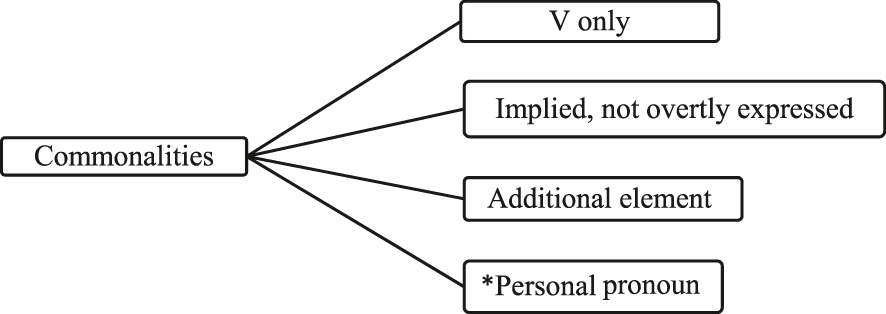

In all the languages investigated, except for Latin,[15] echo answers share four commonalities.

First, the lexical verb in a simple predicate can be repeated alone to indicate ‘yes’. No other element is found to be cross-linguistically as equally pervasive. When Sadock and Zwicky (1985) and König and Siemund (2007) define the echo answering strategy as repeating the verb, their hypothesis holds true if they are specifically referring to the lexical verb in a simple predicate, whether finite or bare. If there is morphological marking on the verb, person marking is usually adapted as in (26). No other language in the sample is found to copy the exact person marking as Brazilian Portuguese (cf. example 15). In contrast, markings such as tense are usually copied as in (26a), and most languages do not adapt the tense marking, except for European Portuguese, as in (17a) (Section 2.4), and Latvian, as in (26b).

| Latin (Terence, The Eunuch 691) | |||

| [Context: A master to a slave:] | |||

| Q: | Emi-ne | ego | te? |

| buy-1sg.prf .-q | I | you | |

| ‘Did I buy you?/Have I bought you?’ | |||

| A: | Emisti. | ||

| buy-2sg.prf | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| Latvian | |||

| Q: | Vai | esi | paēd-is? |

| Q | cop.2sg. prs | eat-sg . prs | |

| ‘Have you had your meal?’ | |||

| A: | Paēd-u | ||

| eat-1sg . pst | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

Of course, if there is no morphological marking on the verb, bare verbs are repeated as in (27).

| Thai (Yaisomanang 2012: 59) | |||

| Q: | Mii | phaa-yú | măy? |

| exist/have | thunder | q/neg | |

| ‘Was there thunder?’ | |||

| A: | Mii. | ||

| exist/have | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

In many languages of the world, an adjective can function syntactically as a verb. They are called “adjectival verbs”. When they are available in a language, they can also stand alone as in (28).

| Indonesian | |

| Q: | Sibuk? |

| be.busy | |

| ‘(Are you) busy?’ | |

| A: | Sibuk . |

| be.busy | |

| ‘Yes.’ | |

The second commonality is that elements that either reinforce or mitigate the force of the affirmative answer, or elements that express epistemic stance of the answerer, can be added. Note that this addition is still within the realm of affirmation, which is different from the expanded answer that gives some extra information apart from affirmation. In (29a), the affirmative answer is enhanced by the addition of the word mesmo ‘indeed’; in (29b), the affirmative answer to the question sounds more assertive with the addition of the sentence-final particle lèè3. Regardless of the effects the added words may introduce – reinforcement, mitigation, or uncertainty – they remain part of the short affirmative answer.

| Brazilian Portuguese | |||||

| Q: | Você | vai | ficar | em | casa? |

| 2sg | fut | stay | at | home | |

| ‘Are you going to stay at home?’ | |||||

| A: | Vou | mesmo! | |||

| fut.1sg | indeed | ||||

| ‘Yes indeed.’ | |||||

| Saek | ||||

| Q: | Sưư4nii6 | halii6 | thruan6 | lè4 |

| now | still | be.like.that | q.conj | |

| ‘Now they are still like that, I conjecture, right?’ | ||||

| A: | Thruan6 | lèè3 | ||

| be.like.that | stat.ayk | |||

| ‘Yes, as you know.’ | ||||

The third commonality is that the verbs can be recovered even when they are not overtly expressed, as seen in (30). However, it does not mean that whenever the verb from the question is not overtly expressed, it can always be recovered and used as an echo answer. There appear to be certain language-specific restrictions on the linguistic context that permits the recoverability of the verb from the question. In all the languages investigated, in the context of (30), copying the unexpressed verb is acceptable; however, this is not the case in other contexts such as (25a), repeated here as (31a). In this context, the echo answer is acceptable in some languages such as Welsh as in (25a), but it is unacceptable in others such as Persian as in (31b), where the ‘yes’ particle has to be used for the answer to be acceptable. This is an interesting topic for future investigation.

| Hungarian | ||

| [Context: A is back from the supermarket and B asks the following question.] | ||

| Q: | Bor-t? | |

| wine-acc | ||

| ‘(Did you buy) wine?’ | ||

| A: | Már | ve-tt-em . |

| already | buy-pst-1sg | |

| ‘Yes.’ | ||

| Welsh (Jones 1999: 110) | |||||

| Q: | ( Wyt | ti | ’n | cymryd) | siwgr? |

| are | you | prog | take | sugar | |

| ‘(Do you take) sugar?’ | |||||

| A: | Ydw . | ||||

| am | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| Persian | ||||

| Q: | Nušabe? | |||

| drink.n? | ||||

| ‘(Shall I serve you) a drink?’ | ||||

| A1: | * Be-riz-id | |||

| sbjv-serve-2sg.hon | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A2: | Bale, | (merci/mamnun) | lotfan | be-riz-id |

| yes | thanks | please | sbjv-serve-2sg.hon | |

| ‘Yes, please do (serve).’ | ||||

The fourth commonality is that a subject or object pronoun cannot stand alone as a ‘yes’ answer in all 26 languages inspected. That the object clitic can function as a short answer is idiosyncratic of Slovenian (cf. (21)), in which the object clitic has undergone an unusual development that leads to the acquisition of predicative characteristics (Dvořák 2007: 209). This explains why it can stand alone as a short affirmative answer.

A summary of the commonalities is provided in Figure 3.

Commonalities of echo answering strategies across the sampled languages.

4.3 Echo-ability hierarchies

4.3.1 Introduction

I term the accessibility of an element from the question in an echo answer as “echo-ability”. In the following sections, I will present two Echo-ability Hierarchies based on the analysis of the data. The hierarchy related to simple and complex predicates will be discussed in Section 4.3.2, while the hierarchy concerning predication will be presented in Section 4.3.3.

4.3.2 Verbal predicate: simple and complex

Verbal predicates generally fall into two types: simple predicates, which involve single lexical verbs, whether finite or bare, and complex predicates, which involve both auxiliaries and lexical verbs. When the predicate in the antecedent question is complex, languages vary in whether the auxiliary alone, the auxiliary and the main verb together, or the main verb without the auxiliary can serve as an answer.[16] The results are presented in Table 2.

Echo answer-forming strategies in verbal predicates.

| Languages | V only | Aux | Aux + main V | Main V (-Aux) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnamese | + | + | + | + |

| European Portuguese | + | + | + | ±a |

| Thai | + | + | + | + |

| Latvian | + | + | + | + |

| Dholuo | + | + | + | – |

| Finnish | + | + | + | – |

| Amharic | + | + | + | – |

| Brazilian Portuguese | + | + | + | – |

| Indonesian | + | + | ± | – |

| Chinese | + | + | + | – |

| Saek | + | + | + | – |

| Croatian | + | + | + | – |

| Persian | + | + | + | – |

| Galician | + | + | – | – |

| Welsh | + | + | – | – |

| Scottish Gaelic | + | + | – | – |

| Hungarian | + | + | – | – |

| Russian | + | +b | – | ±c |

| Latin | + | + | – | – |

| Greek | + | – | + | – |

| Bulgarian | + | – | + | – |

| Korean | + | – | + | – |

| Hebrew | + | – | + | – |

| Berber | + | – | – | – |

| Turkish | + | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Malayalam | + | N/A | N/A | N/A |

-

aThe symbol “±” in the tables in this paper indicates that the strategy is acceptable yet not commonly used. According to Martins (2023: 431–436), to answer by repeating the main verb is restricted to certain questions. Such examples will be provided in Section 5. bI adopt Dik’s (1987/2011) idea that the copula is a type of auxiliary. Hence, “Aux” here refers to the Russian copula, which can co-occur with another verb when it is in the present tense. cI mark “±” here since this strategy is considered as acceptable in Jones (1999: 33), but one of my informants judges it as somewhat unnatural.

In Table 2, “V only” is a general term referring to the use of the lexical verb in a simple predicate from the antecedent question alone as an affirmative answer. Languages differ in how a lexical verb functions alone as a predicate; therefore, the verb used as a predicate is not necessarily a finite verb. In languages like Thai and Chinese, for example, predicate verbs typically do not carry markers of finiteness. “Aux” in the third column indicates that the “auxiliary” is the only repeated element from the question in a complex predicate. This is also the case for “Aux + main verb” in the fourth column and “Main verb (-Aux)” in the fifth column. “Main verb (-Aux)” indicates that in a complex predicate, the other verb, other than the auxiliary, is repeated alone in the echo answer.

Among the 26 languages inspected, two languages do not have the relevant categories of a complex predicate listed in Table 2, and one language (Berber) only allows V. The remaining 23 languages fall into four types: all strategies in Table 2 are accessible (four languages); all strategies except for “Main V (-Aux)” are accessible (nine languages); “V only” and “Aux” strategies are accessible (six languages); and “V only” and “Aux + main V” are accessible (four languages). The percentages of these types are presented in Table 3.

Distribution of different answering strategies in the domain of verbal predicates.

| Accessible strategies | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| All | 4 | 15 % |

| V only, Aux, and Aux + main V | 9 | 35 % |

| V only and Aux | 6 | 23 % |

| V only and Aux + main V | 4 | 15 % |

| V only | 1 | 4 % |

| N/A | 2 | 8 % |

| Total | 26 | 100 % |

Hierarchies capture the underlying cross-linguistic pattern while at the same time providing a systematic specification of how the languages may differ from each other (Dik 1997). The analysis of echo strategies within the domain of verbal predicates leads to the generalization of the cross-linguistic Echo-ability Hierarchy for verbal predicates, as given in (32):

| V < Aux +/– main V < Main V17 |

- 17

The symbol “<” is used here in the sense of “is implied by” or “is less constrained than”.

This hierarchy outlines the cross-linguistic pattern for the accessibility of echo elements in the predicate domain. When relevant, if a language allows the main verb in a complex predicate to be an echo answer, then it also allows the strategies to the left on the hierarchy. And if a language allows an auxiliary to be used in the answer, it will also allow the lexical verb in a simple predicate to serve as an answer. Hence, there are three types of languages: (i) allow all the strategies on the hierarchy (15 %); (ii) allow both “Aux +/– main V” and “V only” (73 %); and (iii) only allow “V only” (4 %). The different types of languages are illustrated as follows.

Four languages (Vietnamese, European Portuguese, Latvian and Thai) generally do not impose many constraints on which element from the complex predicate can be repeated, as illustrated by European Portuguese in (33).

| European Portuguese |

| V only | |||

| Q: | Leste | este | livro? |

| read.pst.2sg | prox | book | |

| ‘Did you read this book?’ | |||

| A: | Li . | ||

| read.pst.1sg | |||

| ‘Yes’ | |||

| Aux or Main V (-Aux) (Martins 2023: 435) | |||||

| Q: | Ele | tem | tomado | os | comprimidos? |

| he | has | take.ptcp.pst | the | pills | |

| ‘Has he been taking his pills?’ | |||||

| A1: | Tem. | ||||

| has | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| A2: | Toma. | ||||

| take.ind.prs.3sg | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

| Aux + main V | ||||||

| Q: | O | João | tem | lido | o | jornal? |

| the | João | has | read | the | newspaper | |

| ‘Has João been reading the newspaper?’ | ||||||

| A: | Tem | lido . | ||||

| has | read | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||

In nine out of 26 languages, the strategies other than the “Main V (-Aux)” strategy are accessible as illustrated by Finnish in (34).

| Finnish |

| V only (Holmberg 2016: 3) | |||

| Q: | Tul-i-vat-ko | lapset | kotiin? |

| come-pst-3pl-q | children | home | |

| ‘Did the children come home?’ | |||

| A: | Tul-i-vat . | ||

| come-pst-3pl | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| Aux, or Aux + main V, or Main V (Holmberg 2001: 141–149) | ||||

| Q: | Onko | Matti | käynyt | Pariisissa?18 |

| has-q | Matti | been | in.Paris | |

| ‘Has Matti been to Paris?’ | ||||

| A1: | On . | |||

| has | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A2: | On | käynyt | ||

| has | been | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A3: | * Käynyt . | |||

| been | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

- 18

In Holmberg (2001), the answer provided to this question was a negative one, which has been adapted into a positive one here. And the other two answers were derived from the relevant discussions throughout his paper.

In Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Russian, Galician and Hungarian, “V only” or “Auxiliary” alone are the only options. The combination of the auxiliary and the main verb, or the main verb without the auxiliary, is not permitted, as illustrated in Scottish Gaelic in (35).

| Scottish Gaelic | |||||||||

| Q: | An | robh | Eubha | air | an | leabhar | a_thoirt | dha | piuthar |

| inter | be.pst | Eubha | prf | the | book | give.inf | to | sister | |

| a h-athar | sa | mhadainn? | |||||||

| her.father.gen | in | the.morning? | |||||||

| ‘Had Eve given the book to her aunt in the morning?’ | |||||||||

| A1: | Bha | ||||||||

| be.pst | |||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||||

| A2: | * Bha | a_ thoirt . | |||||||

| be.pst | give.inf | ||||||||

| A3: | * Thug . | ||||||||

| give.pst | |||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||||

In contrast, as seen in Table 2, four languages (Greek, Bulgarian, Korean and Hebrew) allow the combination of auxiliary and the main verb but not the auxiliary alone, as in Korean in (36).

| Korean |

| V only | |||

| Q: | 그가 | 창문을 | 깨뜨렸니? |

| Ku-ka | changmun-ul | kkayttuly-ess-ni? | |

| 3sg-nom | window-acc | break-pst-inter | |

| ‘Did he break the window?’ | |||

| A: | 깨뜨렸어요. | ||

| Kkayttuly-ess-supnita . | |||

| break-pst-hon | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| Aux and Aux + main V | |||

| Q: | 너 | 영어 | 할 수 있어? |

| Ne | yenge | hal_su_iss-e? | |

| 2sg | English | do-can-inter | |

| ‘Can you speak English?’ | |||

| A1: | 할 수 있어. | ||

| Hal_su_iss-e. | |||

| do-can-decl | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| A2: | *수 있어. | ||

| Su_iss-e. | |||

| can-decl | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

4.3.3 Predication

A predication includes the predicate and its arguments. Since not every language in the sample has a clear grammatical distinction for subjects, and there are “topic-prominent” languages (Chinese, Saek, Hungarian, etc.), I treat the notion “subject” as a functionally comparable concept, in line with Haspelmath (2010). As shown in Table 4, more than half of the languages investigated tend not to repeat either the subject or the object arguments along with the verb. Also, only four languages out of 26 allow phasal polarity expressions to stand alone as a ‘yes’ answer (cf. example (22) for illustrations of phasal-polarity type of echo answers).

Echo answer-forming strategies in predication.

| Languages | V only | V + O | S + V | Phasal polarity expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | + | + | + | – |

| Malayalam | + | + | + | – |

| Greek | + | + | – | – |

| Berber | + | + | – | – |

| Korean | + | + | – | – |

| Turkish | + | + | – | – |

| Bulgarian | + | + | – | – |

| Croatian | + | + | – | – |

| Brazilian Portuguese | + | – | ± | + |

| Finnish | + | – | + | – |

| European Portuguese | + | – | – | + |

| Indonesian | + | – | – | + |

| Vietnamese | + | – | – | + |

| Galician | + | – | – | – |

| Latin | + | – | – | – |

| Chinese | + | – | – | – |

| Russian | + | – | – | – |

| Saek | + | – | – | – |

| Persian | + | – | – | – |

| Welsh | + | – | – | – |

| Scottish Gaelic | + | – | – | – |

| Hungarian | + | – | – | – |

| Dholuo | + | – | – | – |

| Thai | + | – | – | – |

| Latvian | + | – | – | – |

| Amharic | + | – | – | – |

Regarding the presence or absence of the object or the subject in an echo answer, as shown in Table 5, languages are categorized into four types: (i) those that allow the subject and the object (2 languages); (ii) those that allow only the object (6 languages); (iii) those that allow only the subject (2 languages), and (iv) those that allow neither (16 languages). In theory, cross-linguistically, a subject or object can co-occur with the predicate when special emphasis is intended. This emphasis may be introduced by the questioner in the question or provided by the answerer in their response. It is important to note that the research presented in this paper focuses on neutral polar questions and neutral affirmative answers. The echo strategies presented in Table 4 involve only usual echo answers, that is, no special pragmatic effects are intended when a subject or object occurs.

Distribution of echo answering strategies in predication.

| Accessible strategies | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Phasal polarity expression + | 4 | 15 % |

| Phasal polarity expression − | 22 | 85 % |

| Total | 26 | 100 % |

| S + V and V + O | 2 | 8 % |

| V + O | 6 | 23 % |

| S + V | 2 | 8 % |

| V only | 16 | 61 % |

| Total | 26 | 100 % |

These four types are illustrated below.

Malayalam is one of the two languages that allow either the subject or the object to appear alongside the verb.

| Malayalam |

| V only, V+O and S+V | |||

| Q: | Avan | paηam | tannuvoo |

| he | money | give-pst-q | |

| ‘Did he give the money?’ | |||

| A1: | Tannu | ||

| give-pst | |||

| A2: | Avan | tannu | |

| he | give-pst | ||

| A3: | Paηam | tannu | |

| money | give-pst | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

In Greek, Berber, Korean, Turkish, Bulgarian, and Croatian, only V + O is allowed, as illustrated by (38) for Greek.

| Greek |

| V only (Joseph and Philippaki-Warburton 1987: 14) | |||

| Q: | δjavázis | polá | vivlía? |

| read.2sg | many | books.acc | |

| “Do you read many books?’ | |||

| A: | δjavázo | ||

| read.1sg | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| V+O (Joseph and Philippaki-Warburton 1987: 14) | ||||||

| Q: | Évales | to | vivlío | s | to | trapézi? |

| put.2sg | the | book.acc | on | the | table.acc | |

| ‘Did you put the book on the table?’ | ||||||

| A1: | to | évala | ||||

| it.acc | put.1sg | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||

| S+V | |||||

| Q: | Η | Μαρία | έφυγε | για | Άμστερνταμ? |

| I | María | éfyge | gia | Amsterdam? | |

| q | Mary | left.3sg | for | Amsterdam | |

| ‘Did Mary leave for Amsterdam?’ | |||||

| A: | *Αυτή | έφυγε | |||

| Aftí | éfyge | ||||

| she | left.3sg | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

Two languages (Finnish, Brazilian Portuguese) allow the subject, not the object, to appear in the echo answer, as shown for Finnish in (39).

| Finnish |

| V only (Holmberg 2001: 164) | ||||||

| Q: | Onko | Matti | koskaan | halunnut | käydä | Roomassa? |

| has-q | Matti | ever | wanted | to.go | to.Rome | |

| ‘Has Matti ever wanted to go to Rome?’ | ||||||

| A: | On | ( halunnut | ( käydä )) | |||

| has | wanted | to.go | ||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||

| V+O and S+V (Holmberg 2001: 150–151) | |||

| Q: | Ostiko | se | maitoa? |

| bought-q | he/she | milk | |

| ‘Did he/she buy milk?’ | |||

| A1: | Osti | se | |

| bought | she/he | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| A2: | * Osti | maitoa .19 | |

| bought | milk | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

- 19

One of the anonymous reviewers noted that this V + O answer is also acceptable. However, this answer highlights that milk was indeed purchased, making it different from the typical ‘yes’ answer discussed in this paper.

In the sample, 16 languages (61 %) do not permit the presence of either the subject or object in a typical affirmative short answer, as seen in Hungarian (40) and Chinese (41). Hungarian is a highly agglutinative language in which person is expressed in the verb, allowing the subject to be commonly dropped in sentences. Although person is not marked on the verb in Chinese, the subject is usually dropped if it can be inferred from the context. In both types of languages, echo answers are formed by repeating the predicate without including the subject or object.

| Hungarian |

| V only and V+O | |||

| Q: | Lát-od | a | ház-at? |

| see-2sg.def | the | house-acc | |

| ‘Do you see the house?’ | |||

| A1: | Lát-om | ||

| see-1sg.def | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| A2: | * Lát-om | az-t | |

| see-1sg.def | it-acc | ||

| S+V | |||

| Q: | Mari | lát-ott | valaki-t? |

| Mari | see-pst | someone-acc | |

| ‘Did Mari see someone/anyone?’ | |||

| A: | * Ő | lát-ott | |

| she | see-pst | ||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||

| Chinese | ||||

| V only, V+O and S+V | ||||

| Q: | Ni | yang | mao | ma? |

| you | raise | cat | reinf | |

| ‘Do you have cats?’ | ||||

| A1: | Yang | de. | ||

| raise | cert | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A2: | * Yang | mao. | ||

| raise | cat | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

| A3: | * Wo | yang . | ||

| I | raise | |||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||

As seen from Table 5, the majority of languages in the sample (85 %) do not have the phasal polarity expression[20] strategy as in (42) and the echo-ability of a phasal polarity word does not seem to be correlated with the echo-ability of the other strategies. Among the four types of languages discussed above, the phasal polarity expression answering strategy is accessible in two types of languages. One is the Brazilian Portuguese type that allows the S + V strategy and the other is the type that only allows the V only strategy as in European Portuguese, Vietnamese, and Indonesian (43). It appears that the phasal polarity expression strategy is more likely to be accessible in languages that do not allow either the S + V strategy or the V + O strategy, but the sample size is too small to draw any definitive conclusions. This correlation warrants further investigation.

| Chinese | ||||||

| Q: | Yue-liang | yi-jing | chu | lai | le | ma? |

| moon | already | out | come | pfv | reinf | |

| ‘Has the moon already appeared in the sky?’ | ||||||

| A: | * Yi-jing. | |||||

| already | ||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||

| Indonesian | |||||

| Q: | Apa | dia | sudah | mendapat | kuncinya? |

| q | he | already | get | key | |

| ‘Did he already find the key?’ | |||||

| A: | Sudah. | ||||

| already | |||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||

Based on the data analysis above, a (statistical) Echo-ability Hierarchy concerning the accessibility in predication can be established, as presented in (44).

| V only < V+O < S+V |

Cross-linguistically, languages generally prefer not to include either the subject or the object in an echo answer. When they do include one, they favor the strategy of V+O over S+V.

5 Why is repeating the verbal predicate the dominant strategy of echoing?

The cross-linguistic investigation of 26 languages shows that the definition of the echo system proposed by Sadock and Zwicky (1985) is only partially correct. Repeating the lexical verb from a simple predicate in the question (finite or bare, depending on the specific language), is possible in all the languages investigated. However, the repeated material from the question may involve not only a simple predicate, but also a complex one. In such cases, it is not only the lexical verb in the complex predicate that can function as an echo answer; an auxiliary, or both the auxiliary and main verb can also be echoed, as extensively illustrated in Section 4. Hence, it is more accurate to use the term “verbal predicate” rather than “verb” in the definition, to include both simple and complex predicates and exclude non-verbal predicates. The definition could be refined as follows: an echo system involves repeating the verbal predicate of the question, either fully or partially, with or without additional material. This raises the question: why is repeating the verbal predicate the dominant echo answering strategy?

A predicate expresses the properties or relations between arguments (Dik 1997); thus, it is the core constituent of the proposition. In a neutral yes/no question, the inquiry of the question is about whether the arguments have the property or relation as designated by the predicate. Hence, the predicate usually carries the polar value of the whole propositional content. A positive predicate indicates affirmation whereas a negative predicate indicates negation. The negative value is generally marked while the positive value is not. The fact that the predicate is the most salient part in the question is supported by evidence from Finnish. In Finnish, yes/no questions are marked by the question particle – ko or kö, which can be encliticized to different constituents in the question to indicate broad or narrow focus (Holmberg 2016: 28–29). If the particle is encliticized to the fronted finite verb or auxiliary, the question is unmarked and neutral as in (45a); when it is encliticized to other fronted constituents, this results in questions with narrow focus as in (45b). Questions with narrow focus cannot be answered by echo answers. They can only be answered by yes/no particles or by the narrowly focused constituent in the question. This shows that the predicate carries the polar value of the whole propositional content. Hence, it is quite natural to repeat it to form an answer.

| Finnish |

| (Holmberg 2016: 28) | |||

| Pidät- kö | sinä | tästä | kirjasta? |

| like-q | you | this.abl | book.abl |

| ‘Do you like this book?’ | |||

| (Simpson 2014: 317) | |||

| Huolellisesti- ko | Jussi | pesi | auton |

| attentively-q | Jussi | washed | car |

| ‘Was it attentively that Jussi washed his car?’ | |||

Polar questions can be simple, consisting of a predication, or extended, including other elements such as adverbs or adverbial adjuncts. As observed by Simpson (2014), in polar questions with the presence of an adverb or adverbial adjunct, it is likely, yet not necessarily, that the adverb or the adverbial adjunct is narrowly focused, in which case it is illegitimate to respond with an echo answer, as in (46a-A2). However, when the adverb or adverbial adjunct is not narrowly focused, i.e., when questions are concerned with whether the whole event designated by the proposition is true or not, the echo answer is legitimate as in (46b). Example (46b) shows that the echoed predicate có đi is representative of the whole propositional content in the question, which includes adverbial adjuncts such as với vợ ‘with wife’ and vào Chủ-Nhật ‘on Sunday’. The Vietnamese example demonstrates that the echo answering strategy is applicable only to neutral polar questions (where the entire proposition’s polarity is questioned), and not to questions with a narrow focus.

| Vietnamese (Simpson 2014: 323–324) |

| Q: | Sếp | của | Nga | đối-xử | nó | tệ | lắm | hả? |

| boss | of | Nga | treat | her | meanly | very | q | |

| ‘Does Nga’s boss treat her meanly?’ | ||||||||

| A1: | Tệ | lắm. | ||||||

| meanly | very | |||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||||

| A2: | *Đối-xử. | |||||||

| treat | ||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | ||||||||

| Q: | Bạn | có | đi | chùa | với | vợ | vào | Chủ-Nhật | không? |

| friend | be/have | go | temple | with | wife | on | Sunday | neg | |

| ‘On Sunday, do you go to the temple with your wife?’ | |||||||||

| A: | Có | đi. | |||||||

| be/have | go | ||||||||

| ‘Yes.’ | |||||||||