Abstract

The paper discusses languages with ternary quantity of vowels and consonants, analysing the evolutionary mechanisms of the rise of ternary quantity and its alignment with lexicalised laryngeal articulations. Six shared evolutionary mechanisms based on vowel coalescence and segment lengthening or shortening are distinguished, and a couple of alternative paths. Tonal stressless languages show a symmetric system where the voice quality contrast is “orthogonal” to both quantity and pitch. Stress languages manifest two types of asymmetric alignment between overlength (Q3) and laryngeal articulations: “synergistic” and “antagonistic”, the latter being more common across language groups. It appears that the synergistic alignment might instead reflect the situation in which the lexicalised laryngeal contrast is more recent and more dependent on the quantity contrast than in case of the antagonistic alignment. Additionally, an outline of an articulatory model which might account for the rise of the observed quantity-laryngeal-pitch templates in languages with ternary quantity is proposed.

1 Introduction

This paper discusses ternary quantity, which is attested in just a couple dozen languages (Blevins 2004: 201–202; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996: 320–321; Prehn 2012: 223–254), e.g.:

vocalic ternary quantity: Coatlán Lowland Mixe (Mixe-Zoquean) [ˈʦik] ‘coati’ – [ˈpeːt-] ‘sweep’ (bas) – [ˈʦiːˑk-] ‘hit’ (alt);

consonantal ternary quantity: Soikkola Ingrian (Finnic) [ˈkanaː] ‘hen’ – [ˈkanːaː] ‘hen:prt’ – [ˈlinːˑaː] ‘city:prt’.

The sample and the scope of this study are different from those of the most comprehensive overview of ternary quantity to date (Prehn 2012). Prehn considers only vocalic ternary quantity and aims at providing its formal phonological re-analysis as a combination of binary quantity and an additional feature, in line with many theories starting from Trubetzkoy (1939/1969: 177–181). The present study considers also consonantal quantity and includes a series of newly discovered cases and new literature on existing cases. It does not aim at a formal account of ternary quantity, or directly seek to prove or disprove its phonological status in each case. This work is rather in line with “de-exoticising” of rare phonological features by exploring their evolutionary paths and possible biological basis (Anderson et al. in press).

The first major contribution of the study is a typology of the evolutionary mechanisms giving rise to ternary quantity. I distinguish six main and a couple of additional paths and discuss their various combinations. Tracing the paths of emergence and disappearance of common and rare features helps us in explaining synchronic distributions (Bybee 2001; Blevins 2004, 2015; Easterday 2019; Hyman 2018: 16; Kiparsky 2008: 52).

This work also follows “multidimensional” approaches studying typological correlations between features (e.g. Forker 2016; Round and Corbett 2020; Tallman et al. 2024). One such correlation is foregrounded here. It appears that the rise of ternary quantity often includes an interaction between duration and secondary laryngeal articulations. The typology of interaction between ternary quantity, lexicalised laryngeal articulations, and word prosody (tone and stress), constitutes the second major contribution of this paper.

Three types of synchronic alignment between the three parameters are distinguished: a symmetric “orthogonal” alignment between quantity and laryngeal articulations in tone languages and two asymmetric ones (“synergistic” and “antagonistic”) in stress languages. I explore possible diachronic paths which have led to the observed synchronic distributions, as well as discussing their possible grounding in articulation.

This work builds upon the “synchronic typology of prosodic systems with laryngealised and pharyngealised tonemes” by Ivanov (1975), which addresses various correlations between laryngeal features, duration, and pitch. Current work by Iosad (in prep.) approaches the same topic from the perspective of word tone in North-Western Europe. The present paper focuses on durational phenomena and secondary laryngeal articulations.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the sample and the basic notions. Section 3 summarises the main evolutionary mechanisms leading to the rise of ternary quantity. Section 4 addresses the types of alignment between word prosody, ternary quantity, and lexicalised laryngeal articulations. The findings are discussed in Section 5, and Section 6 concludes the study.

2 Sample and key notions

2.1 Sample and sources

The data on 27 varieties analysed for this study are taken from existing publications, my own field research (on Soikkola Ingrian), and personal communication with experts (on Nenets, West Nilotic).

The sample on alleged ternary quantity includes the following areal-genetic groupings (the number of the varieties considered here is indicated in parentheses; see their full list in Supplementary Material 1; SM1):

Uralic (5 Finnic and 1 Saami) and Indo-European (1 Celtic, and 2 West Germanic) varieties of North-Western Europe;

Uralic (2 Nenets) and Yeniseian (2) varieties in North-Western Siberia;

West-Nilotic languages of East and Central Africa (4);

languages of eight families in North America (5) and in Mexico (5).

Available synchronic and diachronic data on many varieties are scarce, and their prosodic systems are often complex; thus the place of ternary quantity within these systems is not always clear. Particular data subsets considered in Sections 3 and 4 are outlined in Section 3.

2.2 Basic notions and transcription

In most varieties of the sample, ternary quantity is related to metrical stress.[1] The relevant prosodic domain of quantity and stress is typically the metrical foot (usually mono- and/or disyllabic, trochaic or iambic, rarer trisyllabic). The ternary quantity contrast appears in stressed syllables in almost all cases (excluding Southeastern Finnish dialects, cf. Supplementary Material 2; SM2).

Several languages of the sample feature lexicalised pitch. In most cases, however, lexicalised pitch is stress-dependent (cf. Hyman 2006), so I treat it as a phonetic cue of stress (referred to below as pitch-stress) rather than as lexical tone. The only clear (and well-studied) exceptions are West Nilotic languages, which synchronically feature lexical tone in the absence of any metrical prominence. In West Nilotic, the domain of both ternary quantity and tone is the syllable.

In all varieties, the domain of lexical prosody (foot or syllable) has a quite clearly defined structure. Prosodic weight is often relevant for prosodic contrasts and processes, including the distinction of light and heavy syllables. Light syllables include (C)V and sometimes word-final unstressed (C)VC structures, and heavy syllables include all other structural types.

All phonetic transcriptions are transformed into IPA for better comparability. The three degrees of quantity are coded as Q1, Q2, Q3 – from the shortest to the longest. In cases of phonologically relevant prosodic weight, Q3 is possible only in structurally heavy syllables. Phonetic studies also show that phonetic overlength in Q3 is a stress feature.

In stressed syllables, the durational ratios between the three degrees of quantity are typically 1 : 2 : 2.5–3.5, i.e. phonetically [short : long : overlong], reflected below as Q1 [ˈV/C] – Q2 [ˈVː/Cː] – Q3 [ˈVːˑ/Cːˑ].

In unstressed syllables (Southwestern Finnish, see SM2) or in stressless tonal languages (West Nilotic), the contrast of durational ratios is roughly 1 : 1.5 : 2, i.e. [short : lengthened : long] (phonetic transcriptions with such cases are not included in the main text, but see SM2).

3 Paths of emergence of ternary quantity

In all cases, the ternary quantity contrast is an innovation which can be traced back to a binary or no length contrast. Either the third degree of quantity (Q3), or, rarer, the second degree (Q2) could be an innovation.

Three varieties (Seri, Wichita, Seneca) indicate a merger of two or three short vowels, or a long and a short vowel, or a short and a long vowel without any additional lengthening processes, i.e. path 1:

| coalescence of vowels (often after a loss of intervocalic consonants): |

| e.g. Seneca *waha:yᴐˀ > [waːˑayoˀ] ‘he arrived’ (Chafe 1959: 493). |

In other cases, ternary quantity likely has prosodic origins, at least in part. This means that its emergence involves lengthening or shortening of sounds under certain prosodic conditions. Five processes are distinguished:

| stress-induced lengthening of long or short vowels (especially in or before open syllables): |

| e.g. qayaani ‘in his own kayak’ (under stress in an open syllable): [qaˈjaːni] in Alaskan Yupik, but [qaˈjaːˑni] in Central Siberian Yupik (Q3), Eskimo-Aleut (Krauss 1985: 21); |

| compensatory lengthening of short or long vowels or consonants due to the loss of the following syllable (Gess 2011; Kavitskaya 2002): |

| cf. cíin-ò ‘intestine’ in Päri with innovative c iì̤i n (Q3) in Dinka, West Nilotic (Andersen 1990: 17); |

| “anti-compensatory” lengthening of short or long consonants, or of long vowels before the longer following matter (Kuznetsova 2013, 2023): |

| e.g. *kanā > Soikkola Ingrian (Finnic) [ˈkanˑaː] ‘hen:prt’ (Q2) (Kuznetsova et al. 2023); |

| lengthening of short or long vowels or consonants in the monosyllabic foot (usually explained by stress lengthening, isochrony, or the minimal foot duration requirement): |

| e.g. *suu > Estonian [ˈsuːˑ] ‘mouth’ (Q3) (Viitso 2003: 11); |

| compensatory shortening of long vowels or consonants due to the longer following matter (i.e. long phonemes or more segments in the prosodic domain), which has been linked to poly-subconstituent shortening (poly-segmental, poly-syllabic, poly-foot; cf. Turk and Shattuck-Hufnagel 2020: 135–143): |

| e.g. *linnan > Estonian (Finnic) [ˈlinˑa(ˑ)] ‘city:gen’ (Q2) (Eek and Meister 2004: 350). |

These mechanisms also occur in various combinations (see case studies in Section 4 and in SM2). A combination can include a coalescence of two short vowels (path 1) and additional (over-)lengthening (cf. Scottish Gaelic in Section 4.5.2).

Potential additional paths 7–8 of the Q3 rise involve an interaction between duration and lexicalised pitch or vowel quality, but the data are too scarce for robust conclusions. For example for Sarsi, a coalescence of two short vowels under a particular lexical tone has been suggested as a source of Q3 (Cook 1971: 166). Interaction with pitch is also discussed below for some stress varieties (Yeniseian, Scottish Gaelic; also Franconian, and Mayo and Hiaki in SM2). A general chronological issue in such cases is whether a particular pitch curve triggers durational lengthening or vice versa. Interaction with vowel quality is mentioned for Franconian and North Low Saxon, but here, too, the relative chronology of cues (vowel quality, duration, pitch) is not straightforward (see Section 5.2).

The rise of Q3 always involves lengthening (usually of long phonemes), while Q2 can emerge either through the lengthening of singletons (as in Soikkola Ingrian) or through the shortening of long phonemes (as in Estonian).

Some of the main stress-related processes (i.e. paths 1–6) might be considered consequences or particular cases of others. This is touched upon in Section 5.1, while in Section 4 and SM2, I instead follow the interpretations of individual authors, without attempting to make the processes above mutually exclusive.

In the survey in Section 4, I consider only prosodic ternary quantity, which involves lengthening or shortening of sounds, so I leave aside Seri, Wichita, and Seneca, which manifest only vowel coalescence. I also omit the only case of ternary quantity in unstressed syllables (Southwestern Finnish dialects), because no alignment with laryngeal activity is detectable there (but see SM2 for the descriptions of this and other varieties not analysed in detail in the main text; Pai and Sarsi are omitted also from SM2 due to scarcity of data).

4 Alignment between quantity degrees and laryngeal articulations

4.1 The laryngeal articulator

A proper account for the activity of the lower vocal tract is still missing from typology (Seifart et al. 2018: e329–e330). However, recent years have seen the rise of the Laryngeal Articulator Model (e.g. Esling 2005; Moisik 2013), together with attempts to implement it in phonology (Moisik et al. 2021).

In the terminology of this model, adopted also here, ‘larynx’ equals ‘pharynx’ equals ‘lower vocal tract’. The lower vocal tract is an active articulator rather than a passive source of vocal fold vibration. All kinds of pharyngeal, epiglottal, and glottal sounds and phonations are produced by the complex aryepiglottic constrictor mechanism together with associated tongue retraction and larynx raising (Esling et al. 2019: 5).

In what follows, all such articulations are labelled as laryngeal articulations/actions. If a language description specifies a more precise mechanism of phonation, this can be mentioned. However, impressionistic descriptions might often be imprecise, because auditory identification of most laryngeal categories has not yet been widely practiced.

Pitch is set as a separate category, because of partially different properties as compared to secondary laryngeal articulations (e.g. the diagnostics outlined in the end of Section 4.3.2 cannot be straightforwardly applied to pitch).

Lexically relevant laryngeal articulations are the focus of this study. The broad phonetic notion of “laryngeal articulations” covers three main types of both synchronic and diachronic phonological units:

laryngeal and pharyngeal consonants (e.g. h, ʔ), and other types of consonants in case of the diachronic sources of synchronic laryngeals (see e.g. Yeniseian);

secondary laryngeal articulations of consonants (e.g. pre-aspiration in Saami or Scottish Gaelic) and voice quality in vowels (in West Nilotic);

word-prosodic units – lexicalised prosodies based on laryngeal articulations (e.g. hiatus in Scottish Gaelic; cf. also Kuznetsova 2018, 2022).

Finally, an important distinction related to lexicalised segmental laryngeal articulations is the contrast of lenis and fortis consonants. This contrast has been distinguished for many varieties studied here, but its phonetic manifestation varies both across languages and across consonantal types. In this study, I apply these terms in cases when more than one acoustic cue based either on duration or on laryngeal articulations distinguishes the members of the correlation (following a similar definition of “weak” and “strong” consonants by Trubetzkoy 1939/1969: 148). The variability of the primary cue may depend either on the prosodic position of a consonant or on its quality (stop, fricative, sonorant, etc.). For example, Leer (1985: 83–87) describes fortis consonants in Alutiiq (Eskimo-Aleut) through a complex bundle of features: as voiceless, tense, longer in duration than lenis (but shorter than geminates), truncating the preceding vowel, pre-occluded, with a preceding hiatus, a reduction of air pressure, or with a schwa-like transition. For the contrasts based on duration only, I use the terms “short” and “long”, while for those based only on voicing, I use the terms “voiced” and “voiceless”.

Ternary quantity and laryngeal articulations show different alignment under two main types of lexical prosody, stress and tone. In what follows, I discuss and exemplify the main types of alignment, starting with tonal languages (Section 4.2) and proceeding with stress languages (Section 4.3).

4.2 Symmetric “orthogonal” alignment: West Nilotic tonal languages

In stressless West Nilotic languages (Dinka, Nuer, Reel, Shilluk), lexical tones, vowel length, and voice quality are synchronically mutually independent parameters. These features show symmetrical orthogonal alignment: most combinations of their values are possible. Such combinations, including also the parameters of vowel quality and consonantal lenition, alternate to express most grammatical meanings, cf. a partial matrix of verbal derivation (columns) and inflection (rows) for tḛem/H ‘to cut’ in Agar Dinka in Table 1 (Andersen 1992–1994: 29). The domain of length, tone, and voice quality is the syllable (Remijsen and Ladd 2008); tone and voice quality are marked once per syllable in Table 1

Partial matrix of verbal derivation (columns) and inflection (rows) for tḛem/H ‘to cut’ in Agar Dinka.

| Simple | cf | cp | b | bap | ap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ø | tḛ̀em | teḛ́em | teè̤em | té̤em | té̤em | tè̤m |

| nf | teḛ́em | tɛɛ̰́ɛm | tɛɛ̤̀ɛm | tɛ̤́ɛm | tɛ̤́ɛm | tḛ̀m |

| nts | teḛ́em | teḛ́em | teé̤em | té̤em | té̤em | té̤em |

| 1sg | tɛɛ̰̀ɛm | tɛɛ̰́ɛm | tɛɛ̤̀ɛm | tɛ̤́ɛm | tɛ̤́ɛm | tɛ̤̀ɛm |

| 2sg | tḛ́em | tɛɛ̰̀ɛm-é̤ | teé̤em | tɛ̤̀ɛm-é̤ | tɛ̤̀ɛm-é̤ | tɛ̤̀ɛm-é̤ |

| 3sg | teḛ̀em | teḛ́em | teè̤em | té̤em | té̤em | tè̤em |

Modern West Nilotic languages vary by the systems of quantity, tone, and voice quality. There are languages with zero, binary, and ternary quantity contrasts (Andersen 1990). Agar Dinka has three tones (high, mid, low), while tone number reaches nine in Shilluk (Remijsen et al. 2019). Agar Dinka has a binary voice quality contrast (breathy vs. creaky), while in Bor Dinka, the voice quality distinctions include breathy, modal, creaky, and hollow (faucalised) (Edmondson and Esling 2006).

Proto-West-Nilotic apparently had only high and low tone (Storch 2005), a binary quantity contrast (Andersen 1990; Monich and Baerman 2022), and a [±ATR] contrast (Andersen 1990; Esling et al. 2019: 176–177). The subsequent enrichment of quantity, tonal, vowel and voice quality contrasts happened through the loss of one or two monosyllabic suffixes following the root.

In particular, the loss of suffixes triggered compensatory lengthening in stems. Original short (Q1) and long (Q2) vowels lengthened to Q2 and Q3 respectively. In other cases, original length was preserved, or Q2 vowels even shortened to Q1. These processes of compensatory lengthening and shortening have created ternary quantity (Andersen 1990; Monich and Baerman 2022). Similar compensatory lengthening of vowels before occasionally eliding glides or vowels is still an ongoing process in Shilluk and Nuer (Reid 2009, 2019).

The binary breathy/creaky voice contrast, as in Agar Dinka, likely originates from [±ATR] (see Section 5.2). In some cases, now vanished [+ATR] suffix vowels harmonised stem [-ATR] vowels, which has produced stem alternations in vowel and voice quality (Andersen 1990, 2017). Tonal enrichment apparently also partially stemmed from the loss of suffixes (Remijsen, pers. comm.).

4.3 Asymmetric alignment in stress languages: key notions

4.3.1 “Strong” and “weak” foot templates

In the stress varieties analysed here, phonological categories based on duration, laryngeal articulations and, in some cases, pitch curves manifest different types of asymmetric synchronic distribution. To analyse the asymmetries and their diachronic background, we need to introduce the notion of the “quantity-laryngeal(-pitch)” templates of the foot.

Often languages manifest just two templates, referred to below as “strong” versus “weak” (grade or pattern), so the system is binary. This is the case of the Indo-European, Eskimo-Aleut, and most Uralic varieties discussed here (cf. also Morrison 2019; Iosad in prep. on North European languages in a similar vein).

The templates themselves describe the types of synchronic distribution of quantity, laryngeal, and sometimes pitch values, but the terms “strong” and “weak” reflect the diachronic processes of stressed syllable/foot strengthening which have occurred under certain prosodic conditions. Depending on the foot structure and on the variety, the particular phonetic and phonological manifestation of the distinction between the strong and the weak pattern may vary. The diachronic principles are largely shared, however:[2]

“strong” templates reflect either the diachronic processes of lengthening and other kinds of phonetic stress-related “strengthening” of sounds (see processes 2–5 in Section 3), or a retention of a (non-weakened) proto-language pattern;

“weak” templates reflect either the diachronic processes of shortening and lenition of sounds (see e.g. process 6 in Section 3), or a retention of a (non-strengthened) proto-language pattern.

Consider three examples from North Saami (NSa) and Standard Finnish (Fin) in Table 2 and their reconstructions for the Finno-Saamic common state based on Sammallahti (1998), cf. Section 4.5.1. The weak pattern is present in genitive (before the foot-final syllable originally closed with *-n) and the strong pattern in nominative (before the original foot-final open syllable). Cases in Table 2 exemplify the three main types of correlations between the weak and the strong pattern observed in my sample:

(2-a) weakening – default (= retention of the proto-language state);

(2-b) default – strengthening;

(2-c) weakening – strengthening.

Examples of the three main types of correlations between the weak and the strong pattern observed in the sample.

| *Finno-Saamic | Weak template (gen) | Strong template (nom) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| *joke-n – *joki ‘river’ (gen – nom) |

a. Fin [ˈjoen] (weakening – loss of *k) b. NSa [ˈjo k aː] (default) |

Fin [ˈjo

k

i] (default – retention of *k) NSa [ˈjo hk aː] (strengthening *k > [hk] |

|

| *käte-n – *käti ‘hand’ (gen – nom) | c. NSa [ˈkie

ð

a] (weakening *t > [ð]) |

NSa [ˈkie

ht

a] (strengthening *t > [ht]) |

Some languages (Livonian, Mixe, Yeniseian) manifest more complex systems: four to six contrastive foot templates of a similar kind (see respective sections). Such complex systems are referred to below as multiple systems. Some of their templates can equally be considered strong and others weak.

4.3.2 Types of alignment

The alignment between quantity degrees and laryngeal articulations is analysed below with reference to weak versus strong foot templates.

Overlength (Q3) is always associated with strong templates. Laryngeal articulations, in turn, are associated with either weak or strong templates. The alignment of laryngeals and Q3 can be, therefore, divided into two broad types:

synergistic – laryngeal articulations are aligned with Q3 within the strong templates, as for example in Livonian infinitives [kilːˑə] ‘sow:inf’ (Q3), [piˀdːə] ‘keep:inf’ (stød, a glottal prosody) – while we find neither Q3 nor laryngeals in the weak templates in imperatives [kiːla] ‘sow:imp’, [pidaː] ‘keep:imp’ (cf. Section 4.6.1).

antagonistic – laryngeal articulations occur in weak templates and are aligned with Q1 or Q2, as in Scottish Gaelic varieties: Q2 [poː] (Applecross) ∼ [poˀo] (Barra) ∼ [po h ə ∼ po|ə] (Harris) ‘submerged rock’ – while the strong template can feature Q3 [poːˑ] (Applecross) ∼ Q2 [poː] (Barra, Harris) ‘cow’ (cf. Section 4.5.2).

These synchronic distributions likely reflect different kinds of functional mechanisms which have produced them (see Section 5). The laryngeals occurring in the syllable coda or intervocalically can be classified into two functional diachronic types corresponding to their synchronic distribution:

synergistic laryngeals – historically, culminative features additionally enhancing the stressed syllable (i.e., they have the same prosodic function as overlengthening);

antagonistic laryngeals – historically, delimitative features blocking syllable strengthening through (over)lengthening (i.e. they have a prosodic function opposed to that of overlengthening).

The outcome of the alleged enhancing versus blocking diachronic mechanism – a synergistic or antagonistic alignment between laryngeals and overlength – may be synchronically observed either in one variety across different foot structures, or in the same foot structure across different varieties.

In the Livonian examples above (see also Section 4.6), the strong template in the infinitive is realised either through durational lengthening or through a glottal prosody (stød), depending on the original foot structure. This indicates a common enhancing diachronic mechanism behind both.

By contrast, in the Scottish Gaelic examples above (see also Section 4.5.2), we observe that, in some varieties, Q3 may occur in the strong template, while laryngeal articulations may occur only in the opposed weak template. Therefore, we can suggest contrary diachronic prosodic mechanisms behind Q3 and laryngeals. As discussed in Section 5.4, different alignment might also reflect differences in the relative age of lexicalised quantity versus lexicalised laryngeal articulations.

In the overview below, I exemplify different types of alignment with some cases, while briefly mentioning other similar cases (see SM2 for more information on these latter varieties). I progress from more limited (Section 4.4) to broader alignment, and within the latter from simpler (Section 4.5) to more complex (Section 4.6) systems.

For each case, I discuss (i) the rise of ternary quantity and (ii) its synchronic alignment to lexicalised laryngeal articulations within weak and strong foot templates. The alignment of laryngeal articulations to weak or strong templates is detected based on three main diagnostics:

presence of laryngeal articulations in one pattern versus absence in another;

fortis consonants in one pattern versus lenis in another (see Section 4.1);

otherwise strengthened laryngeal articulation (longer, tenser etc.) in one pattern versus lack of strengthening in another.

4.4 Limited alignment in a binary pattern

We start from the cases of relatively limited alignment between ternary quantity and laryngeal articulations. Here, the alignment only concerns either certain groups of sounds (typically obstruents) or consonants at foot boundaries, i.e. outside the syllable nucleus, where overlengthening occurs.

4.4.1 Standard Estonian and other cases: synergistic alignment

Estonian is the only known language with ternary quantity both in vowels and in consonants (Table 3; examples are from Viitso 2003: 14). Estonian has a binary system: weak (Q1–Q2) versus strong (Q3) templates are respectively marked as /´/ versus /`/ in Table 3 (Eek 1990; Kuznetsova 2018; Viitso 1978). Stressed monosyllables manifest only Q3 (Viitso 2003: 11).

Examples of vocalic and consonantal ternary quantity in Standard Estonian.

| Vowels | Consonants | Etymology† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| weak | Q1 | a. ´vina [ˈvinaː] ‘streak of smoke’ | e. ´lina [ˈlinaː] ‘linen’ | < *lina |

| weak | Q2 | b. ´viina [ˈviːna(ˑ)] ‘vodka:gen’ | f. ´linna [ˈlinˑa(ˑ)] ‘city:gen’ | < *linnan << *lidnan |

| strong | Q3 | c. `viina [ˈviːˑna] ‘vodka:prt’ | g. `linna [ˈlinːˑa] ‘city:prt’ | < *linnā << *lidnata |

| d. `viin [ˈviːˑn] ‘vodka’ | h. `linn [ˈlinːˑ] ‘city’ | < *linna << *lidna |

-

Notes: †only the development of the consonantal quantity is exemplified (vowels show parallel development); Proto-Finnic is the deepest etymology.

Estonian ternary quantity has allegedly emerged through four main mechanisms in the foot-initial stressed syllable:

Q2 – compensatory shortening of vowels and consonants in the heavy syllable before a closed syllable: [ˈlinˑa(ˑ)] < *linnan (Table 3-f) (Eek and Meister 2004: 348; Tauli 1954; Viitso 1997);

Q3 – lengthening (possibly compensatory) in the stressed heavy syllable along with the loss of the following short vowel in an open syllable: [ˈlinːˑ] < *linna (Table 3-h) (Eek and Meister 2004: 338–348; Tauli 1954), `kandlen [ˈkanːˑd̥len] < *kantelen ‘kantele (traditional musical instrument):gen’ (Tauli 1954: 5);

Q3 – “anti-compensatory” lengthening of vowels and consonants before a “contracted” long vowel or diphthong[3] (cf. Kuznetsova 2013, 2023): [ˈlinːˑa] < *linnā < *linnata (Q3 < Q2) (Table 3-g), also late [ˈlinːˑa] < *linā < *linahan ‘linen:ill’ (Q3 < Q1);

monosyllabic Q3 – all monosyllables (excluding clitics) acquire Q3 under word/sentence stress, as in *suu > [ˈsuːˑ] ‘mouth’ (Hint 1977: 223–224; Tauli 1954: 15–16; Viitso 2003: 11).

None of those diachronic mechanisms manifests an involvement of overt laryngeal articulations. However, ternary quantity is synchronically supported by a phonetic (half-)voicing feature in lenis versus fortis stops (p, t, k) and fricatives (s, h) in the positions of ternary quantity distinction (after a vowel/sonorant before a vowel), e.g.: ´lagi [ˈlag̊iː] ‘ceiling’ (Q1) – ´saki [ˈsakˑi(ˑ)] ‘jag:gen’ – `sakki [ˈsakːˑi] ‘jag:prt’. This is an innovative lenition, as only a durational contrast between short and long voiceless stops has been reconstructed for Proto-Finnic (Setälä 1891). It rather indicates a synergistic alignment of Q3 and laryngeal articulations: “stronger” laryngeal articulations in fortis consonants are aligned together with Q3 within the strong pattern. However, also Q2 obstruents in a weak pattern are voiceless, so the alignment is not perfect (cf. with vowels in North Low Saxon in Section 4.4.2). Other potential subtle synergistic laryngeal activity in Estonian is discussed in Section 5.3.

Another Finnic variety with ternary quantity – the Soikkola dialect of Ingrian – manifests a similar picture: a binary system of foot templates, where ternary quantity is supported by the voicing feature in lenis versus fortis consonants (see SM2 and further data in Kuznetsova et al. 2023).

In Yupik (Eskimo-Aleut), vocalic overlength in Central Siberian Yupik and the laryngeal “fortition” of consonants in Central Alaskan Yupik (allophonic) and Alutiiq (phonologised; cf. the description in Section 4.1) also show a synergistic alignment within the strong template (the “stressed” foot”), as opposed to the weak template (the “unstressed foot”), but in a different form (see the detailed account in SM2). Lengthening of short vowels and overlengthening of long vowels under stress in open syllables has strengthened the foot nucleus – the stressed vowel, while consonantal fortition – the left boundary of the foot. Both foot boundaries can also be strengthened through consonantal gemination in Alutiiq and Central Alaskan Yupik. “These processes thus set apart the accented foot as a highly marked unit” (Leer 1985: 90). On the contrary, the “unaccented” foot “is not strengthened in either way” (p. 117).

4.4.2 North Low Saxon and other cases: antagonistic alignment

In North Low Saxon dialects (north Germany and north-east Netherlands; see Prehn 2012), ternary vocalic length exists in monosyllables or word-final stressed syllables, as shown in Table 4 (Prehn 2012: 2).

Example of vocalic ternary quantity in North Low Saxon.

| Q1 (weak) | Q2 (weak) | Q3 (strong) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. [ˈstık] ‘pencil’ < MLG *sticke |

b. [ˈsteːk] ‘pierce:1sg’ < MLG *steke |

c. [ˈsteːˑg̥] ‘jetty:pl’ < MLG *stege |

The system has developed from Middle Low German (MLG) through the compensatory lengthening of phonetically long stressed vowels/diphthongs to overlong, if followed by a lenis obstruent (Table 4-c), with a loss of the foot-final syllable. Lengthening did not happen if the stressed vowel was phonetically short (Table 4-a) and/or if the following consonant was a fortis obstruent (Table 4-b). From a diachronic point of view, Q3, based on lengthening, can be considered as the strong pattern versus Q1–Q2 with no lengthening as the weak pattern, so the model is binary.

As in Estonian, laryngeal articulations here are part of the phonemic distinction between lenis and fortis obstruents. However, laryngeal articulations here are antagonistic to overlength in the sense that fortis obstruents, with more prominent secondary laryngeal articulations, have blocked long vowel overlengthening.

Prehn (2012) found that synchronic word-final fortis obstruents manifest shorter closure and longer aspiration (i.e. more prominent laryngeal articulation) than lenis obstruents, at least in some speakers. On the other hand, words with a sonorant coda show little synchronic durational differences between expected Q2 and Q3 (e.g. expected *[miːn] ‘my’ vs. *[miːˑn] ‘(coal)mine’) both in vowel duration and in the sonorant coda duration. The original contrast between lenis and fortis sonorants has been, therefore, almost lost. Pitch is also generally irrelevant in distinguishing between Q2 and Q3 according to Prehn’s measurements.

On the other hand, ternary quantity in North Low German is supported by vowel quality: “lax” in Q1 (shorter and more open, Table 4-a) versus “tense” (longer and more close) in Q2-Q3 (Table 4b-c). Lax vowels have developed from MLG short vowels or long vowels in closed syllables, tense vowels elsewhere. Such a vowel contrast might also be based on different laryngeal articulations rather than simply on duration plus height, but no articulatory studies are available. Vowel quality, however, shows only partial alignment with the weak versus strong pattern (similar to the Estonian obstruents, cf. Section 4.4.1).

Cases parallel to North Low German are Nenets (Uralic) and possibly Hopi (Uto-Aztecan). In both, we observe compensatory lengthening of vowels (in Hopi) or stressed vowels and consonants (in Nenets) along with a loss of the subsequent syllable containing a reduced vowel (cf. SM2). For Hopi, an inverse relation of the vowel duration to the laryngeal “strength” of the coda obstruent has also been suggested. An inverse relation of the same kind is also observed within the multiple pattern of Lowland Mixe (Section 4.6.2). Franconian (High German) dialects also show a binary pattern partially overlapping with that of North Low Saxon. However, both synchronic and diachronic fit is only partial, and, in addition to durational differences, Franconian varieties manifest a strong pitch cue and a much stronger vowel quality cue (see SM2 and the discussion in Section 5.2).

4.5 Extended alignment in a binary pattern

In the varieties analysed in Section 4.5, the system is still binary, but an interaction between durational lengthening and laryngeal articulations is more immediate and more extended throughout the system. Laryngeal activity here is more closely related to stress rather than to single consonants and it occurs in the prosodic centre of the foot rather than at its margins.

4.5.1 Saami: synergistic alignment

The Saami languages manifest a binary pattern, traditionally called “gradation”. Phonetic manifestation of the contrast between the weak and the strong template depends both on the foot structure and on the Saami variety.

Examples in Table 5 are based on the Western Finnmark (or Inland) varieties of North Saami (Aikio and Ylikoski 2022; Bals et al. 2007; Bals Baal et al. 2012; Sammallahti 1998). The main mechanism of the rise of the strong template is the “anti-compensatory” lengthening of consonants, usually before an open syllable (Sammallahti 1998: 3). This is illustrated by nominatives in Table 5, while the weak (non-strengthened) pattern is exemplified by genitives with the second originally closed syllable (cf. Table 1 and notes to Table 5).

Examples of consonantal ternary quantity and other types of aligned contrasts in Western Finnmark (Inland) North Saami.

| Weak (gen) | Strong (nom) | Gloss | *PS < *FS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i. | Q1 | Q2 | after the 1st light syllable | |

| a. nama [ˈnamaː] | namma [ˈnamːaː] | ‘name’ | *ne̮m̀e̮ < *nimi | |

| b. gieđa [ˈkieða] | giehta [ˈkiehta] | ‘hand’ | *kiet̀e̮ < *käti | |

| c. joŋa [ˈjonʲaː] | jokŋa [ˈjotʲnʲaː ∼ ˈjoˀnʲaː] | ‘lingonberry’ | *jōηə ∼ F juo- | |

|

|

||||

| ii. | Q2 | Q3 | after the 1st heavy syllable | |

| d. golli [ˈkolːiː] | gol’li [ˈkolːˑiː] | ‘gold’ | *kollē < *kulta | |

| e. áhči [ˈaːhʧiː] | áhčči [ˈahˑ( a )ʧiː] | ‘father’ | *āh̀č’ē < *isä | |

| f. gopmi [ˈkopmiː ∼ ˈkoˀmiː] | gobmi [ˈkobˑmiː ∼ ˈkobˑˀpmiː ∼ ˈkomːˀmiː] | ‘ghost’ | ∼ F kummi- | |

| g. oappá [ˈoapːaː] | oabbá [ˈŏăbˑpaː] | ‘sister’ | *ōmpē ∼ F orpo | |

| h. bártni [ˈpaːrt|niː ∼ ˈpaːrˀ.niː] | bárdni [ˈpaːrˑ( ɛ )|t̆niː ∼ ˈpaːr( ɛ )|ˀniː] | ‘boy’ | *pār̀nē | |

-

Notes: Proto-Saami (“PS”) and Finno-Saamic (“FS”) reconstructions rely on Sammallahti (1998) and Lehtiranta (2001); in some cases, cognate Standard Finnish (“F”) stems are provided. All proto-stems roughly correspond to proto-nominatives, while proto-genitives additionally contained final *-n.

Original light feet (Q1) strengthened in Saami to Q2, while original heavy feet (Q2) strengthened to Q3. Strengthening concerned all types of consonants and clusters after the stressed syllable and is synchronically manifest through:

extra duration of consonants (Table 5-a, d);

pre-aspiration of voiceless short stops and affricates (Table 5-b);

lengthening of pre-aspiration (with an optional epenthetic vowel; Table 5-e);

lengthening of pre-occlusion/pre-glottalisation (Table 5-f);

voicing of obstruent geminates (Table 5-g);

allegedly different syllabification of clusters (with an optional epenthetic vowel; Table 5-h).

In addition to the “anti-compensatory” Q1>Q2 and Q2>Q3 lengthening shown in Table 5, Q3 North Saami also features the following processes:

“anti-compensatory” gemination of Q1>Q3 before original overlong vowels: sul’lot [sulːˑoh] < *suol̀ûk < *salojit ‘island:pl’ (Sammallahti 1998: 45);

in Western Finnmark only, further lengthening of Q2>Q3 after short vowels, e.g. Q2 in (5a, c-d) can be realised as Q3 (Hiovain et al. 2020);

Q3>Q2 shortening in “allegro” modern North Saami speech, especially in more frequent lexemes: bargá [parˑkaː → parka] ‘work:3sg’ (Aikio and Ylikoski 2022: 156–157).

The alignment between extra duration and the addition of laryngeal articulations (pre-aspiration, pre-glottalisation) in the strong Saami templates is synergistic. In the Q1>Q2 change, either a laryngeal articulation or extra duration has been added. In the Q2>Q3 change, duration and laryngeal features have received extra enhancement. All strengthening in the strong templates has been accounted through an additional subglottal pulse (Harms 1975; Sammallahti 1977, 2012), see Section 5.2.

4.5.2 Scottish Gaelic: antagonistic alignment

Scottish Gaelic dialects manifest a binary pattern evident in heavy feet, cf. parts (ii-iii) in Table 6 (examples are from Borgstrøm 1940, 1941; Morrison 2019). The strong template originates from the syllable nucleus strengthening in heavy monosyllables *(C)Vː (bò) and *(C)VC(C) (arm). The weak pattern with no strengthening and, in certain cases, a loss of intervocalic consonant originates from a disyllabic sequence *(C)VCV(C) (bodha, aran).

Examples of vocalic ternary quantity and other types of aligned contrasts in Scottish Gaelic varieties.

| Strong < *monosyllable | Weak <*disyllable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| i. | Synchronic V | Q1 < *(C)VC [ˈt̪ú(h) ∼ ˈtǔ] dubh ‘black’ [ˈt̪ûh] dubh [ˈtʲʰe(ˀ)] teth ‘hot’ |

|

| a. Lewis | |||

| b. Duirinish | |||

| c. Islay | |||

|

|

|||

| ii. | Synchronic VV | Q3 < *(C)Vː | Q2 < *(C)V|V <*(C)VCV |

| bò ‘cow’ | bodha ‘submerged rock’ | ||

| d. Lewis | [ˈpǒː ∼ ˈpóː] | [ˈpóə] | |

| e. Harris | [ˈpôː] | [ˈpo h ə ∼ ˈpo|ə] | |

| f. Barra | [ˈpoː] | [ˈpoˀo] | |

| g. Applecross | [ˈpoːˑ] | [ˈpoː] | |

| h. Duirinish | [ˈpóː ò ] | [ˈɔ́ò] ogha ‘grandchild’ | |

| j. Islay | [ˈpou] | [ˈpoˀu] | |

|

|

|||

| iii. | Synchronic VRV | (C){VRV}C < *(C)VR V C < *(C)VRC (svarabhakti) | *(C)VRVC |

| arm ‘army’ | aran ‘bread’ | ||

| k. Lewis | [ˈ{a|rá}m] | [ˈár|an] | |

| l. Barra | [ˈ{ɛnɛ}m] ainm ‘name’ | [ˈanəm] anam ‘soul’ | |

| m. Applecross, Duirinish | [ˈ{araˑ}m ∼ ˈ{araː}m] | [ˈaran] | |

| n. Islay | [ˈarəm] | [ˈaˀran] | |

| o. East Perthshire | [ˈɛnːm] ainm | [ˈpirəx] biorach ‘pointed’ | |

In some varieties, the contrast has been partially or completely lost, neither does it exist in Standard Irish. In other cases, the phonetic manifestation of the contrast varies both across structures and across varieties.

The strong template originating from *(C)Vː (bò) features vowel overlength [poːˑ] in the varieties of Applecross and Duirinish of Ross-shire (Table 6-g-h) (Borgstrøm 1941; Ternes 1973, 1980), possibly accompanied by minor differences in pitch (Ternes 2006: 139–140). In other varieties, the strong templates features either a plain long vowel, or a long vowel with a distinct pitch contour, e.g. rising/high in Lewis [pǒː ∼ póː] (Table 6-d).

In the *(C)VR(C) syllables with a cluster of a sonorant and a heterorganic consonant (arm), the strengthening in the strong template resulted in a specific epenthetic vowel after the sonorant (the so-called “svarabhakti” group, marked by {} in Table 6, part iii). The “svarabhakti” group is realised in Applecross and Duirinish through the lengthening of the epenthetic vowel: [{araˑ}m ∼ {araː}m] (Table 6-m), while in other dialects, e.g. through the rising/high pitch over the whole group (Table 6-k), the lack of epenthetic vowel qualitative reduction (Table 6-l), or the coda consonant lengthening (Table 6-o).

On the contrary, the weak pattern (bodha) contains a so-called “hiatus” at the former or still existing syllable boundary. Hiatus partly originates from Gaelic pre-history and phonetically often contains more or less acoustically evident laryngeal activity (see Section 5.2). Synchronically it is a prosodic feature, most evident under strong stress (Mandić 2021). Notably, in Applecross and Duirinish, hiatus has blocked the overlengthening of a long vowel, thus creating Q2: *(C)VCV > *(C)V|V > [poː] (Table 6-g-h). Other types of synchronic realisation of the *(C)V|V hiatus in the weak template involve more “visible” acoustic cues of laryngeal activity: weaker or stronger glottalisation (Table 6-f, g), insertion of a glottal fricative h (Table 6-e), a pitch drop (Table 6-d, h), and an intensity drop (see details in Mandić 2021).

In the *(C)VRVC structure (aran), where the intervocalic sonorant was not dropped, the acoustic cues of hiatus can nevertheless be present – again, as glottalisation (Table 6-n), as a pitch drop (Table 6-k), or simply as shorter duration in Applecross and Duirinish, as in [aran] (Table 6-m).

The fact that the laryngeal articulation typical of hiatus has prevented vowel overlengthening in the bodha type in Applecross and Duirinish, indicates the antagonistic alignment between lengthening and laryngeals, unlike in Saami.

4.6 Alignment in multiple patterns

Varieties in Section 4.6 present three different types of alignment in multiple patterns (from four to six quantity-laryngeal(-pitch) foot templates).

4.6.1 Livonian: synergistic alignment

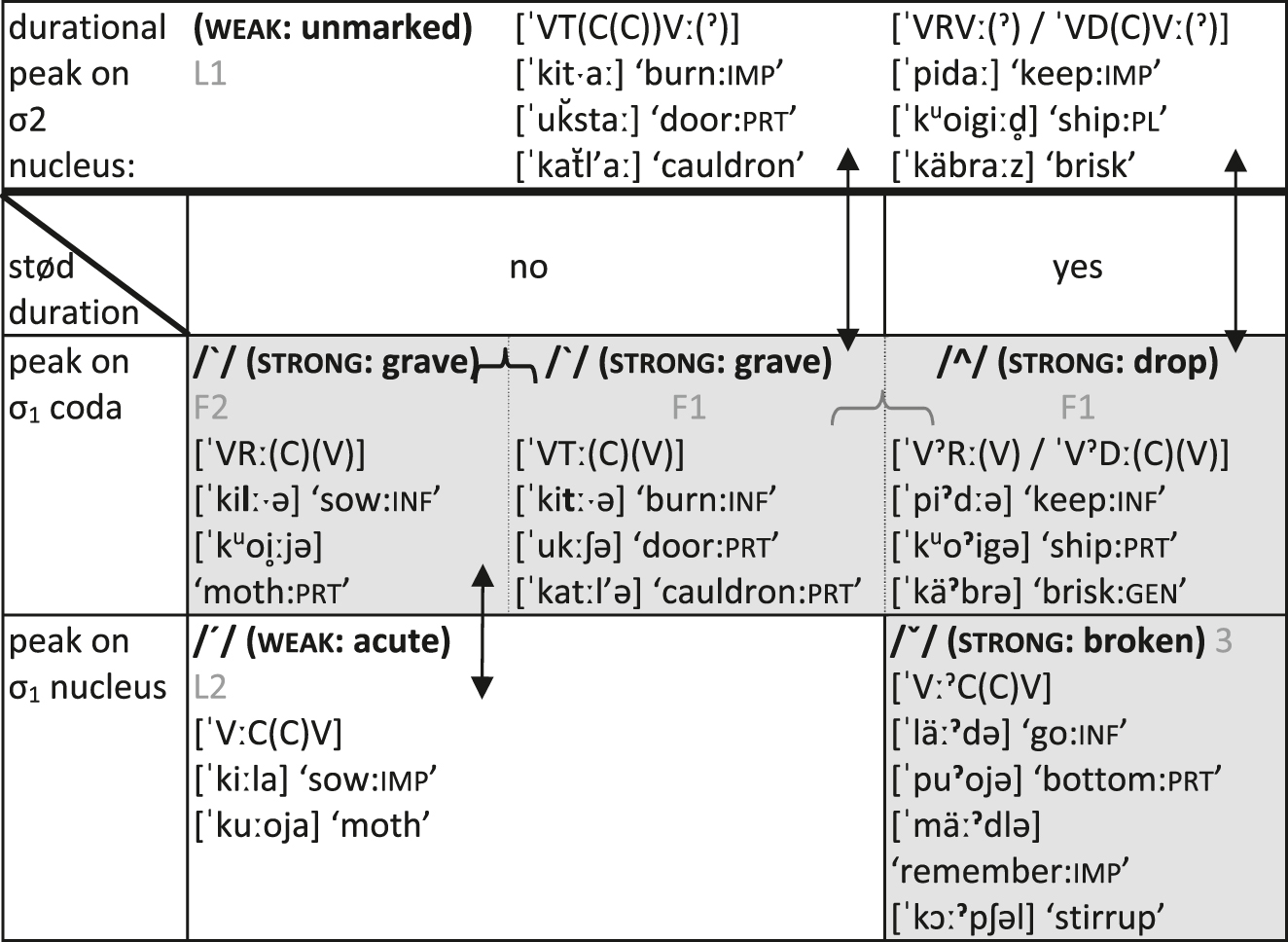

Livonian represents an innovative multiple Finnic pattern distinguishing between five quantity-stød foot templates. Two slightly different descriptions of these templates (referred to as “accents” in both) are combined in Figure 1.

Duration-stød templates in Livonian: labels of the “accents” by Viitso are in bold black, by Kuleshov – in bold grey (“F” = strong, “L” = weak). Vertical arrows show main paradigmatic alternations between templates, illustrated by examples.

The two systems differ in the grouping (shown by) of the [ˈVTː(C)(V)] type together with either [ˈVRː(C)(V)] on phonetic grounds (lack of stød; Viitso 1974, 1975) into the “grave accent”, or with [ˈVːˀC(C)V] on the basis of alternations in paradigms (Kuleshov 2012) into the “F1 accent”. Both systems in any case agree in their classification of certain foot templates as strong (called “strong” or “F”; grey-shaded in Figure 1) and others as weak (“weak” / “L”).

Strong templates, like in Saami, show lengthening or other types of coda strengthening in the stressed syllable (Viitso 2007), including the consonantal Q3 in [ˈkilːˑə], [ˈkitːˑə], or stød, as in [ˈpiˀdːə] or [ˈkuoˀigə]. Like in Saami, Livonian Q3 and stød are restricted to strong templates, so their alignment is synergistic. The two features are in complementary distribution across foot structures. Stød is possible in heavy stressed syllables with a long vowel/diphthong/triphthong, or with a short vowel followed by a voiced geminate/cluster.

In Livonian, coda strengthening in strong templates happened along with post-stress vowel reduction or loss. By contrast, weak templates manifest the lack of post-stress vowel reduction, e.g. [ˈkiːla], or even the lengthening of this vowel: [ˈkitˑaː], [ˈkuoigiːd̥] etc.

Notably, certain structures with either a weak (“L2 / acute accent”) or a strong (“3 / broken”) template have lengthened their stressed vowel, e.g. [ˈkuːoja], [ˈläːˀdə] (cf. Finnish k oi , l ä hteä). This late process happened on top of an already existing system of strong and weak templates. The resulting distribution is peculiar because this is the only case in the sample where we synchronically observe stressed vowel lengthening in weak templates.

In sum, the Livonian system represents the “gradation” quite different from a common Finnic type (Viitso 2007: 55). It can be described through a combination of two parameters: (a) presence versus absence of stød and (b) the locus of the durational peak in the foot: in the 1st syllable (σ1) nucleus or coda, or, in the “weak/unmarked” pattern, in the 2nd syllable (σ2) nucleus (Figure 1).

The diachronic processes of the consonantal ternary quantity formation are nevertheless similar to other Finnic languages (Viitso 2007, 2008), with an addition of stød rules. Livonian stød corresponds to a former syllable boundary (Kiparsky 2017; Wiik 1989; Table 7-d, f), which in some cases can ultimately originate from a loss of the consonant h (Table 7-g). The mechanisms of the ternary quantity and stød development can be summarised as follows:

lenition of original short obstruents to voiced (Table 7-a);

the development of stød with the loss of *h in some mono- and disyllables (Table 7-g).

Examples of the origins of consonantal ternary quantity and aligned types of contrasts in Livonian.

| Q1 | a. [ˈpidaː] ‘keep:imp’ | < *pidäk | |

| Q2 | b. [ˈkitˑaː] ‘burn:imp’ | < *küttäk | |

| Q3 | c. [ˈkitːˑə] ‘burn:inf’ | < *küttǟ < küttätäk | |

| Other types | d. [ˈpiˀdːə] ‘keep:inf’ | < *pitǟ < pitätäk | |

| e. [ukːʃ] ‘door’ f. [käˀd] ‘hand:gen’ g. [vɔːˀ] ‘wax’ |

< *uksi < *käten < *vaha |

4.6.2 Lowland Mixe: combined synergistic and antagonistic alignment

Vocalic ternary quantity before stops and sonorants (Table 8-a-c) has been described for the Coatlán (“Cn”), San José El Paraíso (“SJ”), and Camotlán (“Ca”) dialects of Lowland Oaxacan Mixe (Mexico). Lowland Mixe varieties contain six prosodic types of syllabic nuclei in stressed (foot-final) syllables, so it is a multiple pattern (Table 8-a-d; examples are from Bickford 1985; Dieterman van Haitsma and van Haitsma 1976; Hoogshagen 1959; Wichmann 1995). In paradigms, Q2 alternates with either Q1 or Q3.

Examples of vocalic ternary quantity and aligned types of contrasts in Lowland Mixe varieties.

| Type | pOM | Lowland Mixe varieties | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | Q1 | *CVC | CVC ∼ CVCː | |

| *cik | [ʦik] Cn, Ca ∼ [ʦikː] Gu | ‘coati’ | ||

| *pɨn | [pɨn] Cn, SJ, Ca ∼ [pɨnː] Gu | ‘who’ | ||

| b. | Q2 | *CV(ː)hC(C), CV(ː)CC | CV(ː)C ∼ CV(ː)Cː(C) | |

| *poːhš j -m j | [poːʃ] Cn, [poːʃp] Ca ∼ [poːʃjːp] Gu | ‘spider’ | ||

| *tunn | [tun] Cn ∼ [tuːn] Ca ∼ [tunː] Gu | ‘hill’ | ||

| c. | Q3 | *CVː(ˀ)C | CVːˑC ∼ CVːˀC | |

| *ciːˀk (alt) | [ʦiːˑk-] Cn, [ʦːˑg̊-] SJ ∼ [ʦiːˀp-] Gu | ‘hit’ | ||

| *kaːn | [kaːˑn] Cn, SJ, Ca, Gu | ‘salt’ | ||

| d. | Vh | *CVh(C) | CVh(ː), CVhT | |

| *pɨh- (alt) | [pih-] Cn ∼ [pihː-] Gu | ‘flourish’ | ||

| *pih-n | [pihtj] Ca, Gu | ‘bag’ | ||

| e. | Vˀ | *CVˀ(h)T(C), *CVːˀN j | CVˀC(C) ∼ CVˀVC(C) | |

| *nɨ́ˀhpjnj | [nïˀpj] Cn, [neˀpjtj] Ca, [nïˀtj ] Gu | ‘blood’ | ||

| *caːˀnj | [ʦaˀnj] Cn ∼ [ʦaˀanj] SJ, [ʦaˀanj(tj)] Ca | ‘snake’ | ||

| f. | VˀV | *CVˀV(h)C | CVˀVC(ː) ∼ CVˀC | |

| *paˀahk | [paˀak] Cn, Ca, Gu, [paˀag̊] SJ | ‘sweet’ | ||

| *taˀam | [taˀm] Cn ∼ [taˀam(ː)] Ca, Gu | ‘bitter’ |

Vocalic ternary quantity is likely accompanied by the contrast of lenis/fortis consonants, postulated for Midland and Lowland Mixe by Nordell (Bickford 1985; DiCanio and Bennett 2020; Wichmann 1995: 25–28). A phonetic study by Bickford (1985) on the Guichicovi variety of Lowland Mixe (“Gu” in Table 8) showed that both short and long vowels are shorter before fortis consonants and longer before lenis consonants. The durational difference in lenis versus fortis plosives is accompanied by their voicedness versus voicelessness. However, the durational difference between the expected fortis sonorants in Q2 and the lenis ones in Q3 was very subtle (see also measurements in Dieterman 2002: 34), which is similar to North Low Saxon (Section 4.4.2).

For Proto-Mixe-Zoque, Wichmann (1995: 67–68) reconstructs long vowels, laryngeal consonants *h and *ʔ, and many disyllabic templates. Most disyllables lost the second syllable without any compensatory lengthening. Few (iambic) disyllabic foot templates are still preserved in Lowland Mixe, e.g. CVCVC, CVCVhC, CVCVˀVC, CVCVː(C) (Wichmann 1995: 116–131).

Original laryngeals could precede or follow other consonants or occur word-finally post-vocalically; *ʔ could also occur intervocalically. However, most researchers prefer to see synchronic laryngeal articulations in Mixe languages as part of the prosodic “syllable nucleus templates” (Romero-Méndez 2009: 54), which is similar to Livonian.

According to Wichmann (1995: 25–34), Q2 is reconstructed as /*V(ː)hC(C)/ or /*V(ː)CC/ for Proto-Oaxacan Mixe (“pOM” in Table 8), cf. *poːhš j -m j , *tunn in (Table 8-b). In turn, Q3 rather corresponds to /*Vː(ˀ)/, where glottalisation is allegedly of prosodic origin,[6] cf. *ciːˀk (8c). Hoogshagen (1959) noticed that Lowland Mixe Q3 etymologically corresponds to /Vːˀ/ in Totontepec (North Highland Mixe).

Additionally, a diachronic and synchronic relation similar to Q2–Q3 is observed between the syllabic types /Vˀ/ and /VˀV/, cf. (Table 8-e, f) (the latter is considered overlong by Wichmann 1995: 47).

To summarise, the development of Lowland Mixe ternary quantity is likely a combination of three processes which together create an isochronic pattern:

(a) strengthening of the consonant coda in the *VC nucleus in Q1 (at least in some varieties);

(b) compensatory vowel shortening before a longer coda (currently, either a fortis consonant or a cluster, depending on the variety) in Q2;

(c) lengthening of short and long vowels before lenis consonants in Q3 (cf. Wichmann 1995: 47).

The division of the six Lowland Mixe foot templates into strong and weak is not immediately straightforward. Among the monosyllabic templates, Q1, Q2, /Vh/, and /Vˀ/ could be classified as weak, while Q3 and /VˀV/, with overlong vowels, as strong. The segmental laryngeal h (from *h) behaves as antagonistic to overlength. It has blocked the long vowel from overlengthening, which has produced Q2. By contrast, /ˀ/, with partially segmental and partially prosodic origins (cf. with Livonian), is rather a synergistic laryngeal, as it has not prevented long vowels from overlengthening (*ciːˀk > [ʦiːˑk-]). Synchronically, /ˀ/ is aligned together with overlong vowels in the strong templates.

4.6.3 Yugh and Ket: from combined to antagonistic alignment

In the Yeniseian languages Ket (Imbat Ket) and Yugh (or Sym Ket, south of core Ket), pitch plays an important but not clearly primary role along with quantity and laryngeal articulations in the distinction of foot templates (examples in Table 9 are from Werner 1979, 1996; see also Vajda 2000).

Examples of the four monosyllabic “tones” in Yugh and Ket.

| tone | Low | Lar. | Q3 | Yugh | Ket | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | – | a. [1ʧel] (Q1) | f. [1teːlʲ] (Q2) | ‘mammoth’ |

| b. [1siːr] (Q2) | g. [1sʲiːl’(i)] (Q2) | ‘summer’ | ||||

| 2 | – | + | – | c. [2iˀr(ː)] (Q1) | h. [2iˀlʲ(ː)] (Q1) | ‘song’ |

| 3 | – | – | + | d. [3soːˑl] (Q3) | i. [3sʲuːˑlʲ] (Q3) | ‘Polar sled’ |

| 4 | + | Y+ K(+)/- |

Y+ K+/- |

e. [4sɛˁːˑr] (Q3) | j. [4sɛ(ˁ)ːˑlʲi] (Q3) ∼ [4sɛlʲ(i)] (Q1) | ‘deer’ |

-

Notes: The matrix of features in the three columns after “tone” is a slightly adapted version of Ivanov (1975: 13; see other variants in Werner 1996: 20–28): “Low” – low pitch register, “Lar” – presence of laryngeal/pharyngeal articulations, “Q3” – presence of phonetic overlength; “Y” – Yugh, “K” – Ket.

Yeniseian feet distinguish between four monosyllabic templates (“tones 1–4” according to Werner) and two disyllabic templates (“tones 5–6”), so the system is multiple. Yugh is more conservative than Ket (Ivanov 1975: 20; Werner 1972: 93) in the following aspects:

in tone 1 (under high/rising pitch): a distinction between short and long vowels[7] in Yugh (Table 9-a-b) versus only long vowels in Ket (Table 9-f-g);

Tone 2 (Table 9-c, h) features short glottalised vowels (optionally interrupted or ending in a full glottal stop) under slightly rising and then steeply falling pitch. Syllable coda is often devoiced, and a sonorant coda can be lengthened.

Tone 3 is typically overlong non-pharyngealised, with rising-falling pitch (Table d, i), although single Yugh speakers occasionally pharyngealise it.

The disyllabic patterns 5 and 6 could be considered as disyllabic variants of tones 3 and 1 (cf. Vajda 2000 for tone 5). If a word becomes monosyllabic, tone 5 alternates with 3, while tone 6 alternates with 1:

tone 5 (rising on the 1st syllable, falling on the 2nd syllable): Yugh 5χɔχət > Ket 3kɔːˑt ‘hunger’;

tone 6 (rising on the 1st syllable, rising-falling on the 2nd syllable): Yugh 6kʌχɨnɨᶇ > Ket 6kʌʁɨᶇ ∼ 1kənː ‘fox:pl’.

Werner (1979, 1996) reconstructs the rise of the tonal system as follows.

Stage 1: distinction between two disyllabic tones like 5 and 6, differing only in pitch.

Stage 2: formation of two monosyllabic tones 1 and 2:

tone 1 with a compensatorily lengthened Q2 vowel < tone 6 through the loss of intervocalic k, g, ɣ, x, q, ʀ, χ and contraction of vowels, e.g. Ket 1təːn < *tʌ̀Rɨ́n ‘finger:pl’ (cf. Yugh 5tʌχɨn);

tone 2 with a short laryngealised (creaky) vowel < tone 5 through the loss of intervocalic k, g, ɣ, x, q, if the 2nd syllable was open, e.g. Yugh, Ket 2duˀ < *dúgə̀ ‘smoke’;

tone 1 with a Q2 vowel both in Yugh and in Ket < disyllabic tone 1 with a preservation of a long Q2 vowel, e.g. Yugh 1kuːl ‘beard’, attested as 1kuːlʲe in the 18th c. Yugh data and in North Ket;

tone 1 with a Q1 vowel in Yugh, but Q2 in Ket (Table 9-a, f) < monosyllables with an original Q1 vowel.

Stage 3: formation of tones 3 and 4 out of tone 2:

tone 3 with a compensatory overlengthened plain vowel < *2(C)VˀC + (C)V(C), with a loss of intervocalic k, g, ɣ, q, ʀ, χ, p, f, e.g. Ket 3saːˑn < *saˀʀɨn ‘squirrel:pl’ (in Yugh 1saχɨn; in singular 2saˀχ);

tone 4 with a compensatory overlengthened pharyngealised vowel <*2(C)Vˀ + (V)CV, e.g. Yugh 4χu ˁ ːˑt’ ‘pike’ < *2χuˀ + *-ədə < *2χuˀk + *-ədə.

The resulting word-prosodic system of Yugh, more conservative than that of Ket, shows a relatively symmetrical alignment between duration and laryngeal articulations. There are two strong templates with compensatorily lengthened Q3 (tones 3–4) and two weak templates without lengthening (tones 1–2). Both strong and weak templates oppose one pattern with a laryngeal articulation (tone 4, 2) and one pattern without it (tone 3, 1). The Yugh system is nevertheless a combined synergistic-antagonistic one rather than truly orthogonal (as in West Nilotic), because the types of laryngeal articulations in the weak versus strong template differ (laryngealisation in tone 2 vs. pharyngealisation in tone 4).

In more innovative Ket, the system is already clearly asymmetric. Tone 4 (with overlength and pharyngealisation) tends to lose either pharyngealisation, or overlength, or eventually both, thus turning into a weak template. Overlength is preserved only in tone 3 (without any laryngeal articulations). Additionally, there is a compensatory lengthening Q1>Q2 in tone 1 (Table 9-a), which also lacks laryngeal articulations. Durational lengthening and laryngeal features, therefore, are complementarily distributed across templates in Ket, i.e. they show an antagonistic alignment.

5 Discussion

The main findings of this study are summarised in Supplementary Material 3 (SM3). Only 13 varieties, for which there is enough synchronic and diachronic data, are included there. For each variety, SM3 shows main synchronic and diachronic parameters related to the ternary quantity contrast, the lexicalised laryngeal articulations, and their interaction.

In Section 5.1, I summarise the main biases in the distribution and the mechanisms of the rise of ternary quantity. A potential role of the laryngeal articulator in the rise of ternary quantity in the stress languages is discussed in Section 5.2, and a possible articulatory account of the rise of the observed quantity-laryngeal-pitch templates is given in Section 5.3. In Section 5.4, I briefly address a possible correlation between the relative chronology of lexicalised quantity and lexicalised laryngeal articulations and the type of their synchronic alignment.

5.1 Structural, genetic, and areal biases in the distribution and rise of ternary quantity and its alignment with laryngeal articulations

Ternary quantity, although rare, has been found in unrelated parts of the world. Most of these varieties have quite innovative word prosody. For many of them, areal contact has been suggested as a source of their phonological innovativeness (see SM2 for details).

Ternary vocalic length is far more common than consonantal (23 and five cases respectively for the 27 varieties considered in this study, cf. SM1). This could be linked to the fact that ternary quantity typically rises through stress-induced and compensatory processes. Compensatory lengthening and shortening are sometimes considered as directly induced by stress (White and Turk 2010; White 2014). Under this view, most if not all of the five main evolutionary mechanisms listed in Section 3 (paths 2–6) are likely the effects of stress (or of some kind of stress-like inequality in prominence, as in the history of West Nilotic). It is of no surprise then that stress-related lengthening more often affects vowels than consonants or that ternary quantity is mostly restricted to stressed syllables.

Consonantal ternary quantity is found only in Finnic and Saami (Uralic). The synergistic alignment of overlength with laryngeals is also mostly concentrated in these varieties. The emergence of both phenomena is closely linked to the specific “anti-compensatory” lengthening of consonants before longer segmental or syllabic matter. This process, not yet accounted for by Articulatory Phonology models, might be possibly linked to the tense pronunciation of the first stressed syllable in these languages (Kuznetsova 2023).

Ternary quantity is considered unstable. This has been explained by its poor perceptual salience and/or difficult articulation (Blevins 2004: 202). Ternary quantity might be especially unstable in unstressed syllables, like in Southeastern Finnish, where the phonetic distance between quantity degrees is very small (cf. SM2). Two paths of a likely further evolution of ternary quantity include either the restoration of binarity (usually a Q2/Q3 merger), or the development of other phonetic features which reinforce ternary quantity (Kuznetsova 2015; McRobbie-Utasi 2007; Remijsen and Gilley 2008).

The features reinforcing ternary quantity in stressed syllables often include an inverse ratio of the duration of certain foot segments to the duration of the sounds in three quantity degrees. For example, in North Low Saxon, Franconian, Lowland Mixe we find shorter vowel quantity degrees before (longer) fortis consonants but vocalic overlength before (shorter) lenis consonants. In Estonian and partly in Soikkola Ingrian, the length degrees in the first syllable are in an inverse relation to the post-stress vowel duration.

Additionally, we often observe correlating vowel quality contrasts (tense/lax, close/open, diphthongised/plain, cf. SM2), a difference in pitch and intensity curves, and antagonistic or synergistic laryngeal articulations. In particular, many of the durational and laryngeal articulations correlating with ternary quantity are part of the contrast of fortis and lenis consonants.

Most of those correlations reinforcing ternary quantity seem to be related to the general type of prosodic innovativeness of the stress languages analysed. In these languages, we observe extreme strengthening of the prominent syllable at the expense of extreme reduction and loss of non-prominent syllables. Metrically prominent syllables receive maximal prosodic enhancement by a whole array of mutually related phonetic features. Some of these cues may remain purely phonetic while others become lexicalised as independent phonological contrasts (see Sections 5.2–5.3).

The degree and/or the type of stress-induced strengthening in the prominent syllable is different across foot structures in the stress languages considered. We observe an interaction between durational lengthening and such factors as the number of syllables in the original structure, the presence of open/closed syllables in certain prosodic positions, the presence/absence of particular laryngeal articulations, the vowel quality type, and the type of pitch register and/or curve. These interactions have created from two to six distinctive quantity-laryngeal(-pitch) foot templates in these varieties.

Importantly, the distribution of quantity degrees, laryngeal articulations, and pitch curves is always asymmetrical to some degree in the stress languages. In particular, two main types of alignment between quantity and laryngeal articulations within foot templates have come to light. Phonetic overlength (Q3) is invariably linked to the “strong” templates (those based on the diachronic processes of strengthening or the lack of weakening). The lexicalised laryngeal articulations interacting with quantity occur either in the strong templates, thus creating a synergistic alignment with overlength, or in the “weak” templates (diachronically based on weakening or the lack of strengthening), thus showing an antagonistic alignment with Q3 (see Section 5.4 for chronological considerations).

By contrast, a group of stressless tonal West Nilotic languages manifests a symmetrical orthogonal alignment between quantity degrees, laryngeal articulations, and pitch. Most values of the three categories combine, creating numerous quantity-laryngeal-pitch foot templates. The lack of metrical stress is apparently part of the story here. Stress is more prone than tone to creating a “conspiracy” between durational, laryngeal, and pitch cues. Indeed, we do not observe anything close to the extremely numerous West Nilotic foot templates in the stress languages, where the combinations of quantity, laryngeal, and pitch values are far more restricted.

A complementary distribution of asymmetrical alignment between duration and laryngeal articulations in the stress languages versus orthogonal alignment in the tonal languages might, therefore, stem from a deep prosodic contrast between stress versus stressless languages. A possible articulatory basis of this difference is further discussed in the next section.

5.2 Potential role of the laryngeal articulator in languages with ternary quantity

The tonal and stress varieties analysed manifest differences also in the types of laryngeal articulations associated with quantity and pitch contrasts.

West Nilotic voice quality (register) contrast, orthogonal to both length and pitch, is a syllable-length larynx postural setting (cf. Esling et al. 2019: 2). The two registers of Agar Dinka – breathy and creaky/modal – correspond to two fundamental states of larynx: unconstricted/lax versus constricted/tense (Esling et al. 2019: 78–79). As noted in Section 4.2, this contrast has been linked to the original contrast in [+ATR] versus [-ATR]. Bor Dinka, with its four registers, “exploit ‘cardinal corners’ of laryngeal contrast: phonatory quality, sphincteric tightening, and larynx height” (Esling et al. 2019; cf. also Edmondson and Esling 2006). Esling and colleagues have also discussed a link of voice quality to other features. Larynx lowering versus raising is seen as a property connecting consonant voicing, pitch height bias, phonatory and vowel quality (Esling et al. 2019: 175–176; cf. also Denning 1989). A possible relation between voice quality and duration, however, is only mentioned in passing (Edmondson and Esling 2006: 188).

For the stress languages with ternary quantity, detailed articulatory studies on larynx activity are still missing. However, existing experimental and impressionistic observations and phonological descriptions show that the lexicalised laryngeal articulations in these languages are generally of a different type, as compared to West Nilotic registers. Rather than a longer-term larynx postural setting, here we observe a momentary “ballistic” articulatory gesture associated with the stressed syllable, typically that of laryngeal/pharyngeal constriction.[8]

The fact that the gesture is momentary likely explains the high variability in its acoustic output, observed for many of the languages analysed. This variability is seen in the phonetic experiments on Livonian stød (Tuisk 2015), Yeniseian laryngeal and pharyngeal articulations (Werner 1969: 88), laryngeal features in Otomanguean languages (Avelino Becerra et al. 2016: 172), in North Franconian laryngealisation under Accent 1 (Kehrein 2017: 169), in realisations of Scottish Gaelic hiatus (Mandić 2021), and in Nenets word-internal glottal stops (Janhunen 1986: 43; Lyublinskaya 2014). Momentary laryngeal constriction can provide a wide range of output, e.g. a glottal stop or a pharyngeal, stronger or weaker vowel glottalisation or pharyngealisation, a pitch and intensity dip, or even no visible acoustic cues (cf. with similarly variable realisation of Danish stød, a glottal prosody, in Grønnum and Basbøll 2007: 200).

Earlier accounts of some of the varieties analysed have suggested that such a laryngeal gesture could be the original source of the variable synchronic acoustic output which does not necessarily always feature overt laryngeals. For example, Harms (1975) and Sammallahti (1977: 63, 1998, 2012) proposed an additional “sub-laryngeal / sub-glottal pulse” on the first post-stress consonant before an open syllable (discernible on spectrograms as an increase in amplitude) as a single source of the strong foot template in Saami, which manifests synergistic/enhancing laryngeal articulations, durational lengthening and epenthetic vowels (cf. Section 4.5.1). Harms (1975: 435) links this alleged extra “ballistic” increase in sub-laryngeal pressure followed by its momentary loss also to a peculiar realisation of the Saami voiced geminates in the strong template: oabbá [ˈŏăbˑpaː], as compared to the voiceless geminates in the weak template: oappá [ˈoapːaː] (Table 5-g). Voiced geminates start as voiced, then become voiceless during closure, and resume voicing at the onset of the next syllable, i.e. are pronounced roughly as [bpb].

According to Harms, in the strong Saami template, not only the syllable peak is more prominent, but also the syllable boundary is more marked: “the stressed syllable is clearly set off from the following syllable by a distinct syllable boundary”, which is phonetically expressed by various means including also epenthetic vowels (Harms 1975: 437). This is parallel to observations on Yupik, where the foot in the strong template is prosodically “set apart” by strengthening both in its nucleus and at its boundaries (cf. Section 4.4.1 and SM2), and, as discussed below, on Estonian Q3, as well as to svarabhakti in the “strong” pattern of Scottish Gaelic (Section 4.5.2).

The variable synchronic output in the strong template in Saami, however, as noted by a reviewer, can also be considered as a direct transformation of an original durational cue rather than of a laryngeal gesture. Indeed, quantity contrasts are widespread across Finno-Saamic languages, while overt lexicalised laryngeal features are observed most prominently only in Saami and Livonian. Therefore, only lexicalised quantity is reconstructed for common Finno-Saamic and for Proto-Finnic. It is an open question, though, whether a durational cue or a laryngeal gesture proposed by Sammallahti and Harms should be reconstructed for Proto-Saami.

A “ballistic” laryngeal gesture might be proposed as the source of variable synchronic output also for some languages with antagonistic/blocking laryngeals. Hiatus versus its absence (accompanied by vowel epenthesis in some structures) is usually seen as the source of the contrast between the strong and the weak templates in Scottish Gaelic (Section 4.5.2). Synchronically, hiatus is realised through a laryngeal action, from “a break in the tension of the glottal chords” between vowels (Borgstrøm 1940, 1941) to an overt glottal stop, or through a falling pitch contour, or shorter duration, or a combination of some of these features (see phonetic details e.g. in Ladefoged et al. 1998; Mandić 2021; Nance 2015; Ternes 2006). There are no articulatory studies on hiatus, though; nor is it clear which realisation is diachronically primary. Given such a varied output and the pitch fall in the hiatus pattern, a laryngeal action associated with the syllable boundary might potentially be the source of synchronic variability (rather than for example the pitch cue). If that were the case, then such laryngeal articulation could have blocked stressed vowels from strengthening through (over-)lengthening (unlike in Saami) thus creating the “weak” pattern.

A unified account through a difference in laryngeal settings has been proposed also for North Franconian dialects (likewise featuring antagonistic/blocking laryngeals, cf. SM2). Engelmann (1910: 383–385) impressionistically described the difference between Accent 1 and 2 (the weak and the strong template) in Moselle-Franconian of Vianden as follows. Under Accent 1, syllables end with a sudden loss of expiration, and under Accent 2, they fade slowly. Engelmann also observed laryngoscopically an overt glottal closure after a vowel or a coda sonorant in Accent 1, especially under strong sentence-final stress (cf. SM2). Like Sammallahti for Saami, Engelmann holds an underlying laryngeal gesture in Franconian Accent 1 versus its absence in Accent 2 responsible for all observed acoustic differences in vocalic and consonantal duration between the two accents, as well as for the voicing contrast of consonants (while the pitch curve appears the same under both accents in this variety).

Franconian Accent 1, however, has only in part emerged out of original disyllables with a voiced intervocalic consonant, for which a syllable boundary marking with a laryngeal gesture can be proposed, cf. the “strong” template *[ˈhaʋz(ə)] ‘house:dat’ > Q3 [huːˑz̥] in North Low Saxon (Prehn 2012: 57, 288), but the “weak” template under a similar process in Franconian: *[ˈhaʋz(ə)] > [1huːs] in Cologne ∼ [1haʋs] in Arzbach (Gussenhoven and Peters 2004: 280; Köhnlein 2016: 92). This path of the rise of Accent 1 in Franconian appears secondary to its original rise out of long non-high vowels, where the intrinsic durational and F0 properties of vowels might have been at play as the primary cues (see SM2), so the role of the laryngeal articulator is not entirely clear here.

Ivanov (1971, 1975) also suggested a laryngeal cue (a transformation of some obstruents into laryngealisation/pharyngealisation under certain prosodic conditions, cf. Section 4.6.3) as the source of Yeniseian (Ket and Yugh) “tones”. Werner (1979, 1996), however, argued that a distinction between two pitch melodies on disyllabic words is older, otherwise some facts remain unexplained. A similar discussion exists e.g. on Danish stød, a lexicalised glottal prosody. Franconian Accent 1 is phonologically comparable to Swedish and Norwegian Accent 1 and to stød in Danish, while Franconian Accent 2 is comparable to Scandinavian Accent 2 and to lack of stød (Peters 2006). It is likewise contentious whether the Scandinavian pitch-based Accent 1 or the stød is older, the predominant view giving primacy to the pitch cue (Iosad 2016).

For Yeniseian, we can in any case say that the lexicalised durational cue is clearly more recent than both the laryngeal and the pitch cue. However, this holds only for glottalisation (the antagonistic laryngeal articulation in Yeniseian). Pharyngealisation (the synergistic laryngeal articulation), according to Werner (cf. Section 4.6.3), has developed later out of laryngealisation, when the durational cue had already been formed from vowel contractions.

From the diachronic point of view, therefore, duration, pitch, and laryngeal articulations in the languages with ternary quantity can apparently all serve as diachronically primary cues and can manifest transformations into each other. Vowel quality might also have a role in some cases, as in Franconian. Below I propose a possible articulatory model which might account for this.

5.3 Possible articulatory account for the rise of quantity-laryngeal-pitch templates in languages with ternary quantity

As said, the Laryngeal Articulator Model does not yet explicitly link duration to other articulatory events in the lower vocal tract. However, as this study also shows, durational events are closely interrelated with other types of laryngeal activity (e.g. laryngealisation, pharyngealisation, pitch and intensity curves), as well as with some events higher up in the vocal tract (e.g. vowel quality and its mutations; cf. SM2). This interaction is strong in stress languages and especially strong in longer types of stressed syllabic nuclei (Q2 and Q3), for the possible reasons explicated below.

If we follow an “approach to speech-motor control based on … phonology-extrinsic timing mechanisms and symbolic phonological representations” (Turk and Shattuck-Hufnagel 2020: 313), recently re-introduced to Articulatory Phonology, we may say that abstract phonological quantity controls the length of time that laryngeal mechanisms accompany oral postures over the course of their articulation.

A progressively longer duration of postures in greater phonological quantity degrees means progressively higher phonetic variability of sounds, because variability in both speech and non-speech movements grows linearly with an increase in duration of an interval (Turk and Shattuck-Hufnagel 2020: 90–95). Greater variability means a larger pool of phonetic realisations and, therefore, more diverse potential sources for sound change (Ohala 1989). Therefore, for long and especially overlong syllabic nuclei, we might expect a higher variability also in laryngeal articulations. For example, in longer sounds we can expect more important changes in the degree of larynx constriction than in shorter sounds. These bigger changes in the states of the larynx trigger, among other things, more prominent pitch and intensity falls in longer sounds, as well as some specific vowel quality mutations (e.g. vowel diphthongisation), observed less frequently or not at all in shorter sounds. Higher articulatory variability in longer sounds causes more phonetic variability, not only in pitch and intensity curves, but also a higher probability of stronger overt voice quality effects (such as laryngealisation, pharyngealisation, aspiration) accompanying durational events than in shorter sounds.

In the progression of a sound change, pitch and voice quality acoustic cues might lexicalise and take over durational cues in primacy, as indeed can be suggested for several varieties in this sample. However, a reverse process, where e.g. durational cues take over the laryngeal ones, or laryngeal cues take over the pitch cues, is also plausible and suggested for some varieties (see SM3). As noted above, stress, i.e. strong metrical prominence, is typically realised through a conspiracy of duration-laryngeal-pitch cues, with their variable primacy across languages and structures. With extra durational lengthening in languages with ternary quantity, the probability of some of these cues becoming prominent enough to be phonologised additionally increases.

As an example of a pool of subtle duration-laryngeal-pitch variability in extra-long syllabic nuclei, let us consider Standard Estonian. Estonian synchronically features complex lexicalised duration-based contrasts and only very limited and late lexicalised laryngeal contrasts interacting with quantity (Section 4.4.1). However, some experimental and impressionistic accounts suggest that subtle articulatory laryngeal activity, synergistic to the distinction between the strong (Q3) and the weak (Q1–Q2) template, might be present more broadly.

Lehiste (1960) and Harms (1962: 8, 11–12) impressionistically described Estonian Q3 through an additional energy pulse. Lehiste (1962) found a clear decrease of subglottal pressure at the end of the Estonian Q3 syllable coda. She interpreted this decrease as a phonetic marker a clear syllabic boundary in Q3, unlike in Q1–Q2 syllables. Like in Saami or Yupik, both the syllable peak and the syllable boundary seem to be strengthening in the strong template here. Harms characterised Q3 as a “free ballistic unchecked movement”[9] versus a shorter and more controlled gesture in Q2. He suggested that longer duration and a specific pitch curve in Q3 might be secondary consequences of this gesture.