Reviewed Publications:

Kibrik Andrej A.. 2011. Reference in Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 688 pp. ISBN: 9780199215805.

van Gijn Rik, Hammond Jeremy, Dejan Matić, Saskia van Putten and Ana Vilacy Galucio (editors). 2014. Information Structure and Reference Tracking in Complex Sentences. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. vi, 409 pp. ISBN: 9789027206862.

Fernandez-Vest M. M. J.. 2015. Detachments for Cohesion: Toward an Information Grammar of Oral Languages. Berlin/Munich/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. x, 340 pp. ISBN 978-3-11-034924-5.

1 Introduction

How do you know what I am talking about; and how can a speaker anticipate and guide interpretations of referents and discussed events? These questions can be linked to a range of common activities in interaction, but also affect language structure in specific ways. The linguistic domains involved, discourse reference and information structure, have received increased and renewed attention in recent typological literature (e.g. Christiansen 2011; Fiedler & Schwarz 2010; Féry & Ishihara 2014; van Gijn & Hammond 2016; Guérin 2019; Kohler 2018; Krifka & Musan 2012; Riesberg et al. 2018; Song 2017; Zimmermann & Féry 2010; Adamou et al. 2018; Fernandez-Vest & Van Valin 2016). This book review seeks to examine three rather different approaches to this topic: the cognitive approach to discourse reference developed by Kibrik (2011), the more traditional typological sentence-oriented discussion of discourse reference and information structure by van Gijn et al. (2014) and the cognitive approach to information structure by Fernandez-Vest (2015), subtitled ‘toward an information grammar of oral languages’.

My main aim is to examine how typologists and descriptive linguists have recently discussed properties of language that are as intrinsically connected to fundamental cognitive and pragmatic features such as organising what is more/less important in discourse and tracking the addressee’s knowledge of referents. If there is an area of typology at all that can be truly theory-independent, discourse reference and information structure are certainly not in it. The three works that guide the discussion in this review take different approaches in calibrating the relation between theory and empirical observation. By comparing these approaches (Kibrik’s in Section 2, van Gijn et al.’s in Section 3 and Fernandez-Vest’s in Section 4) the review hopes to illustrate some current trends in typological thinking about these topics and identify possible implications for future studies (Section 5).

2 Kibrik’s (2011) cognitive perspective

On the face of it, the topic Kibrik (2011) is concerned with could hardly be narrower: At the start of the volume, Kibrik (2011) states that the study deals with specific, definite, third person reference (Kibrik 2011: 34–43), as in (1).

My neighbour from downstairs was an alcoholic. He used to start rows in the yard. (Kibrik 2011: 32)

The first underlined construction in (1) identifies a specific referent and the second underlined element, the pronoun ‘he’, points to the same specific third-person referent. The only difference between the two – Kibrik (2011) refers to these elements as ‘full’ and ‘reduced’ referential devices, respectively – lies in the level of detail they provide about the referent. More particularly, a full referential device marks a specific referent as inaccessible to the addressee, a reduced referential device as accessible.

So far, this analysis may seem of little consequence and perhaps rather thin material for the more than 600 pages Kibrik devotes to it over 16 chapters, grouped into five parts. But the volume is in fact a highly innovative and valuable typological contribution for three reasons: Kibrik (2011) develops a very detailed typology of referential expressions and (bound) pronouns on the one hand, and, what he calls, ‘referential aids’. These include, e.g. gender and noun class, whose contribution to maintaining discourse reference is often assumed cf.(Heath 1985), but difficult to pin down. Second, Kibrik (2011) presents an integrated discourse-based account that includes a multifactorial analysis of full texts, and even addresses aspects of communication that are even less commonly discussed in typology, such as multimodality. By taking up the challenge of discourse the volume broadens both the methodological and empirical base of typology. Third, Kibrik (2011) embeds the study in an original theory about the cognitive mechanisms behind referential acts that allows for positing quite a precise connection between cognition and linguistic form. I will address these points in reverse order.

In part I of the volume (Preliminaries) Kibrik (2011) defines reference as ‘the process of mentioning referents’ and referents, in turn, as ‘image[s] in a person’s mind [which may or may not have] an independent physical existence’ (Kibrik 2011: 5). They participate in events and states (which are thereby qualitatively different) and convey much of the central information in a stretch of talk. Because of their context-dependency discourse, a ‘maximal’ linguistic unit, of ‘unlimited size’, is the only environment in which it can be fully examined, framing the study as an exercise in ‘linguistic discourse analysis’ (Kibrik 2011: 8–11).

These goals are most directly taken up in part VI (The Cognitive Multi-Factorial Approach to Referential Choice) and V (Broadening the Perspective) of the book, where Kibrik (2011) links the form of a referential device to its ‘activation’ in working memory. Specifically, Kibrik (2011) proposes that a referential form (‘referential choice’) is determined by the degree of attention being paid to it (a prerequisite for a referent to enter working memory) and whether it is available in working memory (activation). The set of possible combinations in Table 1 lead to either the absence of a referential expression, a full referential device or a reduced referential device (examples edited to match (1) above).

Attention and activation in cognition and discourse, based on Kibrik (2011: 382).

| Cognitive | -attention | +attention | +attention | -attention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| structure | -activation | -activation | +activation | +activation |

| Linguistic | Referent is | Referent is | Referent is | Referent is |

| structure | not mentioned | mentioned by | mentioned by | not mentioned |

| a full NP | a reduced | (even though | ||

| referential device | being activated) | |||

| Example | n/a | My neighbour | he | n/a |

| from downstairs |

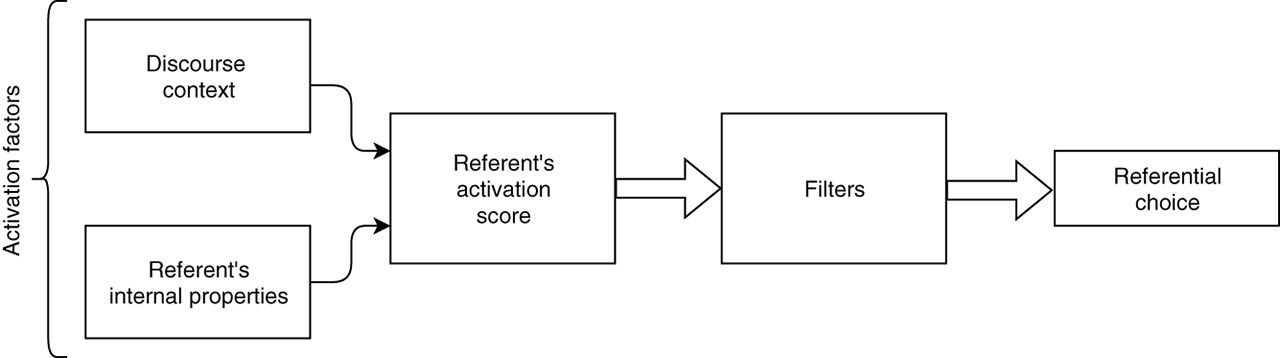

As Table 1 suggests, attention determines whether a referent is mentioned in discourse, absence of attention results in absence of mention. Once a referent receives attention, it may be activated in working memory or not, resulting in a full or reduced referential form, respectively (Kibrik 2011: 452). Activation itself can be analysed using the model of referential choice in Figure 1.

The discourse properties determining a referent’s ‘activation score’, as well as the relevant internal properties of the referent are language-specific. Mainly based on Russian and English narrative data Kibrik (2011) illustrates and develops the model in Figure 1 by scoring the relative weight of semantic factors of the referent such as animacy (inherent property) and discourse properties, such as whether the referent is a protagonist, its distance to the antecedent and the semantic/syntactic roles involved. Each factor receives a percentage for the number of times it occurs with a full or reduced referential device in a sample, resulting in a table of language-specific scores, of which the aggregate can serve to predict the likelihood of a full or reduced referential device being used (Kibrik 2011: 408–409). However, after an activation score has been determined, the expression of a referential device is further influenced by several filters, which may override the activation score and result in low-activated referents to be indicated with a reduced referential device or highly activated referents to be expressed with full NPs. Examples of such filters are what Kibrik (2011: 423) calls the ‘world boundary filter’, which can apply to referents that occur, e.g. adjacent but in different narrative spaces, or the referential conflict filter, which aims to resolve several types of potential ambiguity.

Kibrik (2011) acknowledges that the cross-linguistic aspect of discourse analysis is still at an ‘embryonic’ stage: ‘[a future fine-grained linguistic typology in the domain of discourse reference] may become possible [...] if a significant number of languages have detailed accounts of their referential systems in terms of individual activation factors, quantified for their relative contribution’ Kibrik (2011: 498). Kibrik (2011) also only briefly touches upon referential choice in sign languages and multimodal aspects of reference in Part V, but indicates it as the most exciting direction for future research Kibrik (2011: 563).

Model of referential choice in Kibrik (2011: 394).

The model of referential choice in Figure 1 is already introduced earlier in the book (Kibrik 2011: 64), with the goal of classifying referential elements and elements that affect the referential conflict filter.[1] Although this occurs in the more traditionally typological parts of the book, part II (Typology of Reduced Referential Devices) and III (Typology of Referential Aids), the distinctions the model in Figure 1 prompts, allow for an original cross-lingusitic classification of referential elements.

First, the model of referential choice naturally leads to the question what types of reduced referential devices are there. This prompts Kibrik (2011) to explore similarities and differences between free, bound and, what he calls ‘tenacious’ pronouns (multiple markings of reference) in synchrony and diachrony, and their relation to agreement systems also cf.(Kibrik 2019). But an even more innovative aspect of the typology is the distinction between referential devices proper and ‘referential aids’ (which the author called ‘subsidiary referential devices’ in earlier work; e.g. Kibrik 2001). Referential aids come in two broad classes: ad-hoc and conventional. An example of an ad-hoc referential aid is shown in (2), a conventional one in (3).

Cirebon Javanese (Austronesian, Java; Ewing (2001: 44))

| Ø | kewedien. |

| scared |

| yong | Ø | digolok | Ø | je’, |

| because | pass.slashed | ex |

| Ø | beli | apa-apa |

| neg | anything |

| Ø | beli | mempan |

| neg | vulnerable |

‘They [=Jatiwangi] were scared. Even though they [=Gunungjati] were slashed by them [=Jatiwangi], they [=Gunungjati] were not affected. They [=Gunungjati] were invulnerable’ (Kibrik 2011: 293)

Upper Kuskikwim (Na-Dene, Alaska, USA)

| no-di-ø-ghe-ghił |

| down-cl_wooden-3.nom-pfv-fell.elongated |

‘It fell down [for example, a stick]’ (Kibrik 2011: 303)

Without the cultural knowledge that Gunungjati is an invulnerable being, in addition to the information from prior discourse that Jatiwangi attacked Gunungjati, (2) is difficult to determine. But since a Cirebon Javanese addressee will possess this knowledge (Ewing 2001), the example has no ambiguity. Here, the verbal semantics of, e.g. digolok ‘they were slashed’ conspires with cultural knowledge to serve as a contextual, ad-hoc referential aid.

In example (3) the verbal classifier, marking the referent as an elongated wooden object, allows an addressee to identify the referent even if multiple potential referents are contextually available (e.g. when potential referents are a stone, a child and a stick, only the latter referent applies). Neither ad-hoc nor conventional referential aids are referential devices themselves, but they affect the necessity of a referential conflict filter. Kibrik (2011) adds the following important note:

Referential aids, such as gender, are certainly not used by speakers specifically in order to preclude referential conflicts. The dependency is quite the opposite: when two referents are distinguished due to the gender opposition or another property of the local discourse context, referential conflict is precluded by itself (Kibrik 2011: 65)

In other words, the point is not that referential aids disambiguate reference, but that if they are used referential conflict may not arise (and hence, a reduced referential device or no referential device at all may suffice).

The idea of an activation score is not unfamiliar in the literature on discourse reference, in which ‘scalarity’ often plays a role. For example, the idea that the ‘givenness’ of a referent is not binary but gradient is central to, e.g. the givenness hierarchy Gundel et al. (1993) develop and Kibrik (2011) partially borrows his approach to ‘scalar’ accessibility from Ariel (1988); Ariel (2009) and Prince (1981). But the model of referential choice allows for particularly fine-grained classification of the lingusitic elements involved and, importantly, Kibrik (2011) does not define the distinction between full and reduced referential devices on the basis of these scales alone. As Jeshion (2014) writes:

Kibrik (2011) advocates a multi-dimensional cognitive approach that [...] stresses the importance of extending beyond a single scale for determining referential choice. I am most sympathetic with a wider approach like Kibrik’s (Jeshion 2014: 393)

It may be hoped that that view gains wider uptake still. Despite some of the similarities in theme with the two other volumes discussed below it is only referenced once in van Gijn et al. (2014), and – to my knowledge – none of the more recent works on discourse reference have fully adopted the model of referential choice, or even the notion of referential aids. Also Kibrik’s (2011) very practical linking of cognitive capacities to concrete linguistic forms remains rather unique in the typological literature, and could well benefit analyses of other discourse phenomena, as the following contribution to Krifka & Musan (2012) about the psychology of information structure suggests:

topic status may be assigned at the pre-linguistic message level and then encoded linguistically, and there is some evidence that topic status has an influence that cannot be reduced to changes in the accessibility of referents. However, givenness (and the corresponding increase in accessibility) does appear to be highly relevant in sentence production as well (Wind Cowles 2012: 292)

Kibrik’s model, in which activation is mostly predictive of referent score and the type of referential device used, but is mediated through specific filters is a direct parallel to these insights, and in addition to that makes specific predictions about the types of linguistic elements that contribute to the interpretation.

3 Information structure and reference tracking at sentence level (van Gijn et al. 2014)

van Gijn et al. (2014) is one of the first of several more recent typological volumes that collects original fieldwork on discourse topics cf.(van Gijn & Hammond 2016; Riesberg et al. 2018). Specifically, the papers in van Gijn et al. (2014) deal with either information structure (first half) or discourse reference (discourse tracking) (second half), focussing on these phenomena at sentence level, i.e. in complex clauses. In the introduction to the volume the distinction between the two topics is described as follows:

Information structure can be defined as common ground management: speakers use certain linguistic forms in order to signal which aspects of the common ground are relevant at a given point in discourse and what operations are to be performed on the common ground. Common ground is understood in the Stalnakerian sense [...], as a set of possible worlds compatible with the propositions mutually accepted by the interlocutors. [...] [R]eference tracking, refers to the capability of the interlocutors to unequivocally determine the referent(s) of a linguistic expression. [...] [Information structure and information tracking] both [...] depend on the estimation by the interlocutors of what the current status of the common ground between them is (p. 2)

Whether these definitions sufficiently capture the categories of reference tracking and information structure is perhaps a matter of personal taste (one may wonder what aspects of interaction do not depend on the interlocutors’ estimation of the common ground). But this passage alone already demonstrates the deep engagement of the editors with linguistic theory in relation to their topic. It also highlights an aspect of discourse reference that is more implicit in, e.g. Kibrik’s (2011) definition: it is an intersubjective phenomenon, which, in addition to memory must also rely on socio-cognitive skills.

Although most of the terminology is formal semantic, the authors of the introduction seek a certain degree of cross-theoretical dialogue, particularly between Role and Reference Grammar, the paradigm that the editors are probably most closely associated with and Generative Grammar, in which notions such as anaphora and focus position have shaped important parts of the formalism. The introduction discusses several complex sentence types in relation to information structure and reference tracking, and states as one of its conclusions:

As a general rule, it seems to be the case that more loosely organised complex sentences [...] are more likely to interact with pragmatic factors than tighter constructions (p. 33)

Despite opening the volume with these definitions, the editors do not seem to have imposed any definitions or frameworks on the contributors of the 12 chapters in the volume, which leads to a wonderfully eclectic and rich collection of analyses. The papers are thematically grouped into two book parts: the first part focusing on information structure and the second one on reference tracking, but authors frequently indicate connections between the two. For example, Jenneke van der Wal’s contribution on ‘Subordinate clauses and exclusive focus in Makhuwa’ starts with the observation that Makhuwa word order ‘restrict[s] the preverbal domain to accessible elements functioning as topics’ (p. 45, emphasis added). Saskia van Putten examines ‘Left dislocation and subordination in Avatime (Kwa)’, such as the nominal construction between brackets as in (4).

| [ɔ́-dzɛ | yɛ | fóto-à] | bɛ-z’ɛ | ba | pɔá | |

| c1s-woman | c1s.pos | photo-def.c1p | c1p-receive | c1p | finish | q |

‘The woman’s photos, have they collected them all?’ (p. 75)

Since such constructions, in which an element is placed ‘outside’ the clause occur in subordinate clauses as well, van Putten questions the analysis of left dislocation as an extra-clausal syntactic phenomenon. Following similar suggestions in the introduction, she concludes that subordination can show varying degrees of integration. In his contribution ‘Chechen extraposition as an information ordering strategy’ Erwin R. Komen addresses a similar concern, pointing out that subordinate strategies can contain focal constructions, which complicates the view that subordination necessarily marks backgrounded information. Dejan Matić’s ‘Questions and syntactic islands in Tundra Yukaghir’ brings another variable into the mix: illocution. Luciana Storto returns in ‘Constituent order and information structure in Karitiana’ to the topic of word order in main and subordinate clauses and Patxi Laskurain Ibarluzea brings the section on information structure to a surprising close with ‘Mood selection in the complement of negation matrices in Spanish’. It examines alternations as in (5), showing interaction between focus marking and indicative (5a) vs. subjunctive mood (5b).

| No | dudo | que | eres | una | persona | muy | inteligente. |

| not | doubt.1sg | that | be.2sg.ind | a | person | very | intelligent |

‘I don’t doubt that you are a very intelligent person.’ (ind)

| No | dudo | que | seas | una | persona | muy | inteligente. |

| not | doubt.1sg | that | be.2sg.sbjv | a | person | very | intelligent |

‘I don’t doubt that you are a very intelligent person.’ (p 213–214)

While Laskurain Ibarluzea continues the central theme of the first part of the volume, examining how information structure can lend insight into the syntax of clause structure, the introduction of mood highlights a new aspect of information structure. ‘When the propositional content of the complement is assumed to be active in the addressee’s consciousness at the time of utterance, the subjunctive will be used by the speaker [...], when this is not what the speaker assumes, or it is not her intent to do so, the indicative will be used instead’ (p. 213). Such interactions between mood and information structure are not uncommon in the literature on information structure (cf. verum focus; Lohnstein 2015), but it is a welcome addition to the already broad range of topics caught under the notion.

Ger P. Reesink’s contribution ‘Topic management and clause combination in the Papuan language Usan’ opens the part of the book on reference tracking. The use of the label ‘topic’ may suggest a close connection between information structure and reference tracking, but Reesink defines it broadly as ‘what someone’s speech is about’ (p. 232). The structures discussed in this part of the book are rather similar to the elements Kibrik (2011) discusses (pronouns, inflection), but because of the orientation on clausal constructions the phenomena described are more closely conditioned by syntax. The other contributions to this part of the book are ‘Switch-reference antecedence and subordination in Whitesands (Oceanic)’ (Jeremy Hammond), ‘Repeated dependent clauses in Yurakaré’ (Rik van Gijn), ‘Clause chaining, switch reference and nominalisations in Aguaruna (Jivaroan)’ (Simon E. Overall), ‘The multiple coreference systems in the Ese Ejja subordinate clauses’ (Marine Vuillermet) and ‘Argument marking and reference tracking in Mekens’ (Ana Vilacy Galucio).

Some of the themes of the second half of the book are taken up in van Gijn & Hammond (2016).

van Gijn et al. (2014) strike an excellent balance between drawing connections with the formalist literature in which information structure is treated as an important functional domain in syntax cf.(Erteschik-Shir 2007; Schwabe & Winkler 2007) and allowing contributors to highlight aspects of information structure and discourse reference independent of this literature. This approach, recently also followed with a slightly more functionalist orientation by Riesberg et al. (2018), truly adds to a deeper understanding of the phenomena involved.

4 Discourse between morphosyntax and utterance (Fernandez-Vest 2015)

The types of structure Fernandez-Vest (2015) discusses are close to van Putten’s Avatime example in (4), a syntactic pattern she calls ‘detachments’. The languages that serve as the main empirical basis for the study are French, Swedish, and, particularly, Sámi and Finnish. Examples in these languages are shown as the bold underlined elements in (6) (apart from the addition of boldface and some underlining, all examples appear as in the source).

La peur, chacun la voit d’abord à sa porte ‘Fear, everyone sees it first at their gate’ (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 21, French)

den gamle mannen, han har glömt sin hatt på tåget ‘The old manhe has forgotten his hat on the train’ (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 72, Swedish)

In response to: Where there motorboats even then?

| Jo | / | dat | dat | [DIP] | gal | álge | dan | áigge | / | mohtir-fatnasat | [FD] | gal |

| Yes | / | they | then | [DIP] | yes | began | that | time | / | motorboats | [FD] | yes |

‘Yes / then they / yes they started at that time / the motorboats / yes’ (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 91, Sámi (Spoken))

No se / sota / tuo tuo talvisota [ID] / se loppu oikeestaan / minun kohdaltani siihe että samana / yönä / mentii evakkoon takasi ‘Well this / war / that that winter-war [ID] / it finished in fact / in my case this way that on the same / night / we went back to evacuation’ (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 93, Finnish (Spoken))

What happens in (6) is that, to use Kibrik’s terms, a full and a reduced referential device both occur in the same sentence. The full referential device is ‘detached’ and performs a range of communicative intentions. Detachments can occur sentence initially (as in 6abd) (marked with ‘ID’ in 6d) and finally, as in (6c), marked with ‘FD’.[2] Detachments have long been a research topic; formal approaches (more commonly labelled ‘left-dislocations’) and usage-based approaches, particularly in French, and Fernandez-Vest (2015) is set against this background and the extensive work on information structure in spoken French following Lambrecht (1994). But Fernandez-Vest (2015) draws her main theoretical influence from European functionalism, particularly information structure analysed in the Prague School’s Functional Sentence Perspective (see below).

Like van Gijn et al. (2014), Fernandez-Vest (2015) highlights the intersubjective, ‘common ground’ aspect of information structure/reference, and despite the fact that detachments are primarily an example of information structuring, she highlights the importance of reference for understanding it:

The problem of reference is fundamental regarding Information Structuring in general, and regarding Detachment Constructions in particular (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 40). [R]eference is [...] what the speaker suggests / presents / claims as such, i.e. in the best case, what belongs to a supposed shared knowledge between the interlocutors. (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 79)

But contrary to van Gijn et al. (2014)Fernandez-Vest (2015) does not advocate a syntactic approach, stating the

necessity of analyzing Detachment Constructions at the level on which they belong – the level of enunciation, distinct from that of morphosyntax (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 22)

The notion of ‘enunciation’ here should not be understood in a strict theoretical sense, such as in French/Scandinavian enunciative theory (Anscombre & Ducrot 1976; Nø lke et al. 2004), but rather refers to the traditional (European) functionalist/Prague School idea that language can be treated at a morphosyntactic level that is language-specific and a more general level of organisation that is mainly pragmatic and shows a large degree of cross-linguistic similarity (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 24). The enunciative level in Fernandez-Vest’s sense consists of the categories ‘Theme/Topic (“what is spoken about”) and Rheme/Focus (“what is said about it”) [and] a 3rd element, the Mneme, which is characterized by formal properties (a Post-Rheme marked by flat intonation) and semantic ones (supposedly shared knowledge, affective modulation, etc.)’ (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 24). This is the level of organisation at which detachments should be analysed, according to Fernandez-Vest (2015). And doing so reveals a structure that shows spoken language as having a grammatical organisation that is markedly different from written language.

The book develops this argument over four large chapters, addressing ‘Orality’ (chapter 1), ‘Information Structuring’ (with the progressive indicating that expressing information structure is an active organisational process, not a state of language) (chapter 2), a detailed cross-linguistic typology of detachments, mainly based on the four languages indicated above (‘Detachments in perspective’; chapter 3) and a final chapter addressing the role of syntax in relation to the level of enunciation (Oral syntax and information grammar; chapter 4).

Apart from presenting a wealth of discourse data, demonstrating that traditional labels such as Theme, Rheme and Mneme can be used to classify detachments across languages, Fernandez-Vest (2015) grounds her analysis in a fundamental approach to discourse organisation in oral language. Like the two previous works, the volume exemplifies a deep engagement with theoretical ideas in a typological description, but with a completely different orientation from both Kibrik (2011) and van Gijn et al. (2014). It breaks new ground, especially in the description of discourse structures in terms of enunciative functions and by exploring how this organisation does and does not match syntax, with a prospective ‘ultimate result’

to recognize the Information Grammar of oral languages in its own right, and not merely as a default reproduction of the style(s) pressed upon by the educational systems of our western languages..., that is, typologically highly unusual languages. (Fernandez-Vest 2015: 252)

5 Typological implications: Discussion and conclusion

Discourse reference, information structure and cohesion are each topics that have exerted great influence on the development of linguistic theories. This is true of (traditional) Functionalism, through the Prague school’s Functional Sentence Perspective (Daneš 1966; Firbas 1992), Systemic Functional Grammar’s account of cohesive relations within texts (Halliday & Hasan 1976) and Simon Dik’s formalisation of pragmatic roles (Dik 1989). It applies to Generative Grammar, through the exploration of anaphora and ‘binding’ (Chomsky 1981), and to Usage-Based approaches, by highlighting the contribution of pragmatics to shaping spoken language cf.(Prince 1981; Lambrecht 1994). Nevertheless, discourse reference and information structure have long remained understudied in newly described languages – with the exception of the discourse tradition in Tagmemic linguistics (Pike 1970; Longacre 1983) – and hence in typology. The three volumes that have formed the main focus of this review, as well as the steady stream of books that follow them seem to have initiated a change.

Kibrik (2011), van Gijn et al. (2014) and Fernandez-Vest (2015) demonstrate radically different approaches to discourse reference, but many potential points of convergence are left to be explored. In his opening chapter, Kibrik (2011: 7) writes: ‘This book is based on the assumption that the distinction between referents and event/states is very fundamental’. With respect to the labels Theme/Topic and Rheme/Focus, which Fernandez-Vest (2015) adopts, this presents an interesting challenge. Do themes require a fundamentally different cognitive model than rhemes? And what would a cognitive model for rhemes, parallel to Kibrik’s model of referential choice look like? The intersubjective aspects of the accounts in van Gijn et al. (2014) and Fernandez-Vest (2015) may provide a clue for this. The centrality of ‘common ground’ and shared knowledge to the analyses in van Gijn et al. (2014) and Fernandez-Vest (2015) suggest a broader cognitive basis for information structure (and also discourse reference) than working memory alone, and it would be interesting to see how such socio-cognitive skills cf.(Carlson et al. 2015) may be integrated in a model similar to that of Kibrik’s referential choice.

The papers in van Gijn et al. (2014) further hint at interesting connections between clausal and extra-clausal types of discourse reference and information structure, through, e.g. insubordination and clause-chaining. These would be worth exploring, as well as the connection with less traditionally referential categories, such as mood and discourse particles/affect, which Fernandez-Vest (2015) addresses.

The increased attention to information structure and discourse reference also seems to drive an increased descriptive effort, which may hopefully inspire greater documentary attention to data relevant for studying these topics. As Simpson (2012) notes, testing detailed hypotheses about discourse can only be done if these themes are given serious consideration in language documentation.

In this respect, the three volumes inspire optimism, because they each are the fruit of an organic blending of methodologies, based on personal connections and engagement across linguistic schools and practices. Kibrik (2011) pays tribute to two great typologists, Aleksandr Kibrik, whom he credits with proposing the foundations of his cognitive discourse analysis and Anna Siewierska, for her insight and shared interest in pronouns. But of equal importance to developing the ideas presented must have been his involvement in Athabascan linguistics and a research tradition as initiated by Chafe (1974) in which discussing language form in relation to ‘consciousness’ can be considered. The diverse editorial team of van Gijn et al. (2014) shows that bringing together fieldworkers, typologists and theorists is mutually highly beneficial. And Fernandez-Vest (2015) credits lectures on ‘text linguistics’ in Finland with raising her interest in discourse, and combines functionalist literature with a topic often discussed in French linguistics with original recordings/fieldwork of Finnish and Sámi. As such, these volumes are a testament to how transcending boundaries between frameworks and descriptive practices allows typological insight to grow.

Abbreviations

- c1s

noun class 1 singular (Avatime)

- cl_wooden

wooden object noun class (Upper Kuskikwim)

- ex

exclamative (Cirebon Javanese)

- p

plural (Avatime)

- pos

possessive (Avatime)

References

Adamou, E., K. Haude & M. Vanhove (eds.). 2018. Information structure in lesser-described languages. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.199Suche in Google Scholar

Anscombre, J.-C. & O. Ducrot. 1976. L’argumentation dans la langue. Langages 42. 5–27.10.3406/lgge.1976.2306Suche in Google Scholar

Ariel, M. 1988. Referring and accessibility. Journal of Linguisitics 24. 65–87.10.1017/S0022226700011567Suche in Google Scholar

Ariel, M. 2009. Discourse, grammar, discourse. Discourse Studies 11(1). 5–36.10.1177/1461445608098496Suche in Google Scholar

Carlson, S. M., L. J. Claxton & L. J. Moses. 2015. The relation between executive function and theory of mind is more than skin deep. Journal of Cognition and Development 16(1). 186–197.10.1080/15248372.2013.824883Suche in Google Scholar

Chafe, W. L. 1974. Language and consciousness. Language 50(1). 111–133.10.2307/412014Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.Suche in Google Scholar

Christiansen, T. 2011. Cohesion: A discourse perspective. Bern/New York: Peter Lang.10.3726/978-3-0351-0234-5Suche in Google Scholar

Daneš, F. 1966. A three-level approach to syntax. In F. Daneš, K. Horálek, V. Skalička, P. Trost & J. Vachek (eds.), Travaux linguistiques de Prague 1: L’École de Prague d’aujourd’hui. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck.Suche in Google Scholar

Dik, S. C. 1989. The theory of functional grammar. Dordrecht/Providence: Foris Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Erteschik-Shir, N. 2007. Information structure: The syntax–discourse interface. Oxford etc.: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ewing, M. C. 2001. Reference and recovery in Cirebon Javanese. Australian Journal of Linguistics 21(1). 25–47.10.1080/07268600120042444Suche in Google Scholar

Fernandez-Vest, M. M. J. 2015. Detachments for cohesion: Toward an information grammar of oral languages. Berlin/Munich/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110349535Suche in Google Scholar

Fernandez-Vest, M. M. J. & R. D. Van Valin (eds.). 2016. Information structuring of spoken language from a cross-linguistic perspective. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110368758Suche in Google Scholar

Féry, C. & S. Ishihara (eds.). 2014. The Oxford handbook of information structure. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Fiedler, I. & A. Schwarz (eds.). 2010. The expression of information structure: A documentation of its diversity across Africa. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.91Suche in Google Scholar

Firbas, J. 1992. Functional sentence perspective in written and spoken communication. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511597817Suche in Google Scholar

Gundel, J. K., N. Hedberg & R. Zacharski 1993. Cognitive status and the form of referring expressions in discourse. Language 69. 274–307.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199687305.013.5Suche in Google Scholar

Guérin, V. 2019. Bridging constructions. Berlin: Language Science Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K. & R. Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Heath, J. 1985. Discourse in the field: Clause structure in Ngandi. In J. Nichols & A. C. Woodbury (eds.), Grammar inside and outside the clause: Some approaches to theory from the field, 89–110. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Jeshion, R. 2014. Referentialism and predicativism about proper names. Erkenntnis 80(2). 363–404.10.1007/s10670-014-9700-3Suche in Google Scholar

Kibrik, A. A. 2001. Reference maintenance in discourse. In W. Oesterreicher. W. Raible Martin Haspelmath, Ekkehard König (eds.), Language typology and language universals, vol. 2, 1123–1141. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Kibrik, A. A. 2011. Reference in discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199215805.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kibrik, A. A. 2019. Rethinking agreement: Cognition-to-form mapping. Cognitive Linguistics 30(1). 37–83.10.1515/cog-2017-0035Suche in Google Scholar

Kohler, K. J. 2018. Communicative functions and linguistic forms in speech interaction. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316756782Suche in Google Scholar

Krifka, M. & R. Musan (eds.). 2012. The expression of information structure. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110261608Suche in Google Scholar

Lambrecht, K. 1994. Information structure and sentence form: Topic, focus and the mental representations of discourse referents. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620607Suche in Google Scholar

Lohnstein, H. 2015. Verum focus. Oxford etc.: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.33Suche in Google Scholar

Longacre, R. E. 1983. The grammmar of discourse. New York/London: Plenum Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Nølke, H., K. Fløttum & C. Norén. 2004. ScaPoLine: La théorie scandinave de la polyphonie linguistique. Paris: Kimé.Suche in Google Scholar

Pike, K. L. 1970. Tagmemic and matrix linguistics applied to selected African languages. Norman: Summer Institute of Linguistics of the University of Oklahoma.Suche in Google Scholar

Prince, E. A. 1981. Toward a taxonomy of given-new information. In P. Cole (ed.), Radical pragmatics, 223–256. New York: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Riesberg, S., A. Shiohara & A. Utsumi. 2018. Perspectives on information structure in Austronesian languages. Berlin: Language Science Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Schwabe, K. & S. Winkler (eds.). 2007. On information structure, meaning and form: Generalizations across languages. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.100Suche in Google Scholar

Simpson, J. 2012. Information structure, variation and the referential hierarchy. In F. Seifart, G. Haig, N. P. Himmelmann, D. Jung, A. Margetts & P. Trilsbeek (eds.), Potentials of language documentation: Methods, analyses, and utilization, 73–82. Mānoa: University of Hawai’i Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Song, S. 2017. Modeling information structure in a cross-linguistic perspective. Berlin: Language Science Press.Suche in Google Scholar

van Gijn, R. & J. Hammond (eds.). 2016. Switch reference 2.0. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.114Suche in Google Scholar

van Gijn, R., J. Hammond, D. Matić, S. van Putten & A. Vilacy Galucio (eds.). 2014. Information structure and reference tracking in complex sentences. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.105Suche in Google Scholar

Wind Cowles, H. 2012. The psychology of information structure. In M. Krifka & R. Musan (eds.), The expression of information structure, 287–317. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110261608.287Suche in Google Scholar

Zimmermann, M. & C. Féry (eds.). 2010. Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives. Oxford etc.: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Spronck, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research papers

- Introduction to Nordlinger’s and Rose’s papers

- From body part to applicative: Encoding ‘source’ in Murrinhpatha

- From classifiers to applicatives in Mojeño Trinitario: A new source for applicative markers

- Topicality and the typology of predicative possession

- Methodological contribution

- Token-based typology and word order entropy: A study based on Universal Dependencies

- Book reviews

- To whom it may concern

- Larry M. Hyman and Frans Plank: Phonological typology

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research papers

- Introduction to Nordlinger’s and Rose’s papers

- From body part to applicative: Encoding ‘source’ in Murrinhpatha

- From classifiers to applicatives in Mojeño Trinitario: A new source for applicative markers

- Topicality and the typology of predicative possession

- Methodological contribution

- Token-based typology and word order entropy: A study based on Universal Dependencies

- Book reviews

- To whom it may concern

- Larry M. Hyman and Frans Plank: Phonological typology