Abstract

The paper is concerned with a particular nickname construction in German in which a linguistic expression is inserted between the given name and surname and enclosed by quotation marks (Johanna „Hansi“ Angermeier) or parentheses (Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth). The apparent interchangeability of quotation marks and parentheses in the construction raises the question of the exact meaning of the (variants of the) construction and what the respective punctuation marks contribute to this meaning. The aim of the paper is to develop a comprehensive account of the variation by unfolding the complex interplay between syntax, punctuation, and pragmatics in the meaning constitution of the construction. Based on a close linguistic analysis of examples from a corpus of death notices and supplemented by recent graphematic and pragmatic accounts on punctuation marks, the view is developed that the choice of quotation marks and parentheses is governed by two different, independent processes which partly overlap in the construction. While both quotation marks and parentheses play a role in marking an underlying parenthetical structure, quotation marks are richer in meaning, triggering an additional context shift effect and further conversational implicatures. The analysis lends support to the view that parentheses are boundary signals operating on syntactic structure, while quotation marks are boundary signals operating on the meaning of linguistic expressions.

1 Introduction

Quotation has long been a key issue in philosophical and linguistic approaches to meaning (e.g., Davidson 1979; Saka 1998; Recanati 2001; Cappelen and Lepore 2007; De Brabanter 2013; Maier 2020). Essential issues of debate over the last fifty years have been the nature of the use/mention distinction and its impact on theories of logic, philosophy of language, and the semantics/pragmatics interface; the different types of quotation and their classification; as well as the different kinds of quotation markers across languages (cf. for an overview Brendel et al. 2011). While it has been pointed out early that there are other linguistic and paralinguistic – e.g., graphematic, prosodic, or typographical – devices to signal quotation beyond quotation marks (Klockow 1980), these devices are still not very well understood. What is more, it is only very recently that those particular lexical and phrasal constructions that interact in various ways with quotation marks have received more attention (Finkbeiner 2015; Härtl 2018). Against this backdrop, the gist of the present paper is to show that a close comparison of the usage of different kinds of punctuation marks – quotation marks and parentheses – within the same restricted constructional context may help us to gain a better understanding of the workings of quotation marks at the use/mention boundary. The overall aim is to make not only a contribution to the existing research into the meaning of quotation, but also to foster our understanding of the graphematics/pragmatics interface, a field of study that is only in its beginnings (Meibauer 2020).

I will approach the broader issue of quotational meaning by exploring a particular nickname construction in German in which a linguistic expression enclosed by quotation marks or parentheses is inserted between a given name and surname.[1] This construction, which so far has received only very scant attention in the literature,[2] can be found in German written media discourse mainly within two genres: news reports about celebrities, and death notices. Depending on the genre context, the construction may serve different pragmatic functions. In order to streamline the discussion, I will focus on examples from the latter genre. However, at the end of the paper, I will broaden the perspective, sketching some pragmatic differences that may arise from the different genres.

The utterances (1) and (2) may exemplify the phenomenon to be examined in this paper. These utterances form the core part of the respective death notice, containing the name of the deceased person.[3] Usually, the name of the deceased is singled out, typographically, in a separate line. I indicate this here and in the following by //.

| Johanna „Hansi“ Angermeier // ist nach einem kurzen harten Kampf verstorben. |

| ‘Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier // has passed away after a short, hard struggle’. |

| (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 19 April 2018) |

| Für alle völlig überraschend hat uns // Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth // nach kurzer, schwerer Krankheit für immer verlassen. |

| ‘Suddenly and unexpectedly to all of us // Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth // left for good after a short, severe illness.’ |

| (Frankfurter Rundschau, 17 February 2017) |

In a first approximation, we can say that the expression enclosed in quotation marks in (1) and in parentheses in (2) receives the interpretation of an alternative name of the person whose death is being announced. Thus, both variants seem to yield an ‘also called X’-effect. If this is correct, the question arises why writers sometimes use quotation marks and sometimes parentheses to indicate this meaning. What is the exact contribution of quotation marks and parentheses to the construction, and how do these punctuation marks interact with syntactic and pragmatic factors?

I will pursue these questions on the empirical basis of a corpus of 50 death notices from German daily newspapers that feature instances of the nickname construction. Based on a close examination of the data, the view will be developed that quotation marks and parentheses have certain overlapping functions that may explain their apparent interchangeability in the nickname construction, but that their choice in fact is governed by two different, independent processes. More precisely, I will argue that the parentheses in the nickname construction are graphematic means marking an underlying parenthetical structure in order to facilitate syntactic computation, while the quotation marks in the nickname construction are graphematic means marking the need of reconstructing specific conversational implicatures.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a sketch of the general properties of quotation marks and parentheses in German. Section 3 examines the distribution of the two kinds of punctuation marks in the nickname construction in German death notices. Section 4 analyzes the syntax of the nickname construction, arguing that the expression enclosed by quotation marks or parentheses has the status of a parenthetical. Section 5 develops the view that the prime role of the parentheses as structural boundary signals is in indicating the parenthetical syntax. Section 6 examines the role of quotation marks more closely, arguing that their prime function is in indicating further conversational implicatures, while they, secondarily, also may take over a function as structural boundary signals. Section 7 provides some refinements to the account, particularly with respect to the use/mention distinction and the relevant kind of quotation. In Section 8, it is demonstrated that in different genres – death notices versus news reports – different affective implicatures may arise, depending on whether or not the user of the nickname construction is likely to be identified with the bearer of the nickname. Section 9 summarizes the findings.

2 General properties of quotation marks and parentheses in German

Previous theoretical work on the system of punctuation marks in German is provided by Gallmann (1985) and Bredel (2008, 2011. According to Bredel (2011: 15), quotation marks and parentheses share a number of formal (graphetic and graphotactic) properties, warranting their treatment as two subclasses of one joint superordinate class of punctuation marks. As to their graphetics, i.e., their internal form, quotation marks <„“> and parentheses <()> are “non-empty” signs, which means that they touch the baseline (“Grundlinie”) (as compared to, e.g., hyphen and en dash), they are vertical signs, which means that they go beyond the middle line (“Mittellinie”) (as compared to, e.g., colon and semicolon), and they are reduplicated signs – in fact, the only two true twin signs in German – which means that they are comprised of two elements that always occur together (as compared to, e.g., comma or full stop) (Bredel 2011: 15–17).

As to their graphotactics, i.e., their position in the line and their relationship with neighboring elements, quotation marks and parentheses are clitics, i.e., they attach to an auxiliary sign (“Stützzeichen”, Bredel 2011: 20) and do not fill their own segmental space. This property distinguishes them from en dashes, which may also occur in twin use, but which are no clitics. As compared to, e.g., commas or question marks, which are enclitics, quotation marks and parentheses are combinations of a proclitic and an enclitic, with graphetic differences between the proclitic and the enclitic element. The opening parentheses <(> is curved to the right, the closing parentheses <)> to the left; the opening quotation mark <„> is on the baseline, curved to the left, the closing quotation mark <“> is on the upper line, curved to the right.

Quotation marks and parentheses do not only share formal properties but are also similar in their functions. Gallmann (1985: 28) takes them, together with other punctuation marks, to be boundary signals (“Grenzsignale”), which he defines as graphic means facilitating the segmentation of textual units. Similarly, Bredel (2008) assumes that punctuation marks guide the reader in the computation of written language. As to quotation marks and parentheses, particularly, she holds the view that their function is in the management and regulation of interactional role shifts (Bredel 2008: 128).

Together with <?> and <!>, Bredel (2011: 49) subsumes <„“> and <()> into the class of communicative signs. Roughly speaking, while quotation marks, on this account, manage the integration of voices of others at the level of the speaker/hearer system, parentheses manage the integration of the author’s own voice at the level of the author/reader system. For example, the quotation marks in (3) ascribe the quoted sentence to Anna, i.e., they make clear to the reader that this is not the author’s statement. The information provided by the sentence is to be evaluated at the level of the speaker/hearer system (i.e., the world of Anna and her addressees). The parentheses in (4), by contrast, ascribe the sentence to the author, who – otherwise covert – is here speaking overtly to the reader. This sentence thus must be evaluated at the level of the author-reader-system.

| Anna sagte: „Die Erde ist eine Scheibe.“ |

| ‘“The Earth is a disk”, Anna said.’ |

| Die Erde (wir wissen alle, dass sie keine Scheibe ist) dreht sich um die Sonne. |

| ‘Earth (we all know it is not a disk) revolves around the sun.’ |

From this short sketch, it becomes clear that quotation marks and parentheses share a number of formal properties and fulfill similar, more general functions. This may be taken as an initial motivation for the fact that they may alternate in the nickname construction. At the same time, the comparison of (3) and (4) makes it very clear that quotation marks and parentheses, at a more specialized level, are distinct graphemes with distinct functions. This can be demonstrated very easily by the fact that if we exchange the punctuation marks, the sentences get ungrammatical, cf. (5)–(6).

| *Anna sagte: (Die Erde ist eine Scheibe.) |

| ‘(Earth is a disk), Anna said.’ |

| *Die Erde „wir wissen alle, dass sie keine Scheibe ist“ dreht sich um die Sonne. |

| ‘Earth “we all know it is not a disk” revolves around the sun.’ |

In light of the ungrammaticality of (5)–(6), it seems even more remarkable that quotation marks and parentheses may vary within the context of the nickname construction.

In the next section, it will be shown that there are, in fact, crucial differences in the distribution of <()> and <„“> in the nickname construction, suggesting an analysis that does not assume them to be functionally equivalent. It will be argued that the ‘also called X’-effect, which arises in both constructional variants, is not induced by the quotation marks or parentheses as such, but is to be ascribed to an independent process of syntactic insertion.

3 Distribution of quotation marks and parentheses in the nickname construction

In order to examine the distribution of quotation marks and parentheses in the nickname construction, I compiled a corpus of 50 examples of the nickname construction from death notices published in various German daily newspapers that I collected in an unsystematic fashion between 2017 and 2021.[4] The corpus illustrates the range of constructional variants and points to usage tendencies, without claiming to be exhaustive or representative in a quantitative sense. The complete corpus of constructional variants (types) and their number of attestations (tokens) can be found in the Appendix.

As becomes clear from the overview in the Appendix, most attestations in the corpus, grossly two-thirds (n = 35), can be assigned to the constructional variants [1][5] N1 „X“ N2 (n = 19) and [2] N1 (X) N2 (n = 16). The other examples are distributed across eight other variants, of which the variants [3]–[5] have less than five attestations each and the variants [6]–[10] have only one attestation each. Therefore, I take the constructional variants [1] and [2] to represent the core construction. I will first examine the core construction in more detail, before commenting – in the course of the paper – on the more peripheral variants.

The core construction consists of a sequence of N1 (given name), some expression X, and N2 (surname), with N1 and N2 being of the category proper noun. X is, typically, interpreted as a nickname which – outside the construction – could be used referringly or as a term of address. At first glance, the quoted and the bracketed variant [1] and [2] thus behave rather similarly. However, a close examination of the data reveals there are crucial differences between them.

First, the quoted variant [1] allows for a broader variety of categories as nicknames in X-position compared to the bracketed variant [2]. In the quoted variant, we find as nicknames N0-categories that are morphophonological derivatives of the proper noun in the given name function, e.g., (7), morphophonological derivatives of the proper noun in the surname function, e.g., (8), common nouns, e.g., (9), as well as opaque words that are neither in a morphophonological relation with the given name or surname nor exist as common nouns in German, cf. (10).[6] [7]

| Gertrud „Trudy“ Zink | [1-7] |

| Georg „ Schorsch“ Diehl | [1-6] |

| Ulrich „Lobj“ Lobjinskij | [1-17] |

| Burkhard „Flax“ Flachmann | [1-3] |

| Dirk „Würmchen“ 6 Fuchs | [1-4] |

| Maria „Floh“ 7 Lindermaier-Färbinger | [1-14] |

| Ralf „möfpf“ Maier | [1-16] |

| Günter „Stopei“ Roß | [1-8] |

Furthermore, there is an instance of a DP at X-position, cf. (11).

| Harry „der Chef“ Engelke | [1-9] |

By contrast, in the variant [2] with parentheses, we find at X-position exclusively N0-categories that are derivatives of the given name or surname, e.g., (12), no common nouns or opaque words; neither do we find phrasal categories in between given name and surname.

| Cornelia (Conny) Meister | [2-4] |

| Günter (Utz) Ullrich | [2-6] |

A Fisher’s exact test shows this association to be statistically significant at p < 0.05 (p = 0.02).

Second, there are differences in the sequential ordering of official names and nicknames. While in the quoted variant [1], N1 always represents the official given name and X the nickname (with one exception, [see Footnote 25]), there are several instances of the bracketed variant [2] with reverse order, in which N1 represents the nickname and X the official given name,[8] e.g., (13).

| Käthi (Katharina) Schwinn | [2-10] |

| Otti (Ottilie) Dietz | [2-14] |

A Fisher’s exact test shows also this association to be statistically significant at p < 0.05 (p = 0.035).

Third, with respect to other constructional variants, the sample reveals certain differences as to the licensing of alternative positions of the nickname. While there are, likewise, variants in which a quoted expression immediately succeeds (cf. [4]) or precedes (cf. [5]) the given name-surname combination, cf. Examples (14) and (15), there is no constructional variant in which an expression in parentheses precedes the given name-surname construction. For the cases enclosed in parentheses, only the postponed variant is attested, cf. [3], with the examples (16).[9]

| Margarete Luise Beck // „Gretel“ | [4-2] |

| Marie Nold // „die Glocke Marie“ | [4-3] |

| „Kako“ // Ulla Kalbfleisch-Kottsieper | [5-1] |

| „Oma Lene“ // Maria Magdalena Stephan | [5-2] |

| Gerda Pfeiffer // (Schwester Gerda) | [3-1] |

| Hubertine Jansen // (Tante Tinni) | [3-2] |

While this distributional difference can be observed in the corpus, it is not statistically significant according to Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.47), due to the small total number of attestations for the variants [3]–[5] (n = 10).

Interestingly, in all examples (except one)[10] in which the nickname precedes or follows the given name-surname construction, there is a line break between the two types of names in addition to the punctuation marks (indicated by //, cf. (14)–(17)). As (17) indicates (one attestation), the line break may even render punctuation marks obsolete.

| Christine Biedermann-Tautfest // Krickel | [7-1] |

Sometimes, the line breaks are accompanied by varying font sizes or font styles between the nickname and the given name-surname construction, as in (15a), where “Kako” is represented in the original death notice in a smaller font size than Ulla Kalbfleisch-Kottsieper. More generally, these observations suggest that typography and punctuation systematically interact in the marking of linguistic meaning differences, something which is often neglected in research on the graphematics/pragmatics interface.[11]

Taken together, the analysis of the corpus so far indicates that quotes and parentheses are not interchangeable in the construction across the board, but that there are specific differences in their distribution. In the remainder of the paper, the hypothesis will be developed that quotation marks and parentheses in the nickname construction are licensed by two different processes: While parentheses are licensed syntactically, as markers of a parenthetical structure, the quotation marks are licensed pragmatically, signaling the need to reconstruct additional conversational implicatures. This function may, due to graphematic absorption in certain cases, overlap with a (secondary) function of signaling syntactic markedness in the nickname construction. In order to develop this view, I will first analyze the syntax of the construction, before I go into the role of parentheses and quotation marks in more detail.

4 Syntax of the nickname construction

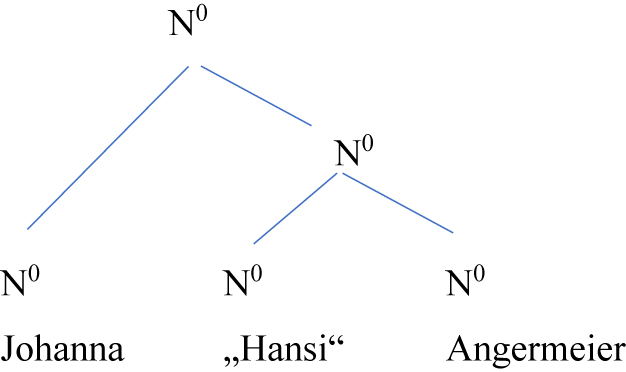

A standard personal-name construction in German is a combination of two or more proper nouns (Np) used to refer to a person or to address this person. Most syntactic accounts of personal names in German take it that personal names are apposition-like syntagms. According to Karnowski and Pafel (2004: 184), a personal name such as Johann Sebastian Bach is syntactically a complex N0, consisting of several N0 categories: a head noun (Bach) and several left-adjoint enlargement nouns (Johann Sebastian), cf. (18).[12]

|

While the adjunction analysis (18) seems to capture the main properties of the standard personal-name construction in German, the question is whether it is also apt for the nickname construction. Applying (18) to our construction would result in (19), in which the quoted expression is treated as a first left-adjoint N0.

|

However, (19) would make the wrong predictions as to the nickname construction. First, it would predict that the quoted expression is more closely related to the surname than to the given name. If this were the case, we would not expect different linearization options to be equally acceptable. However, the different options in (20) – some of them also attested in my corpus – are all equally acceptable.

| Johanna Maria „Hansi“ Angermeier [13] |

| Johanna „Hansi“ Maria Angermeier |

| „Hansi“ Johanna Maria Angermeier [14] |

| Johanna Maria Angermeier „Hansi“ [15] |

Second, an analysis parallel to (18) would predict that the quoted expression is a proper noun. After all, standard personal name constructions consist exclusively of proper nouns.[16] However, as shown in Section 3, the quoted expression may be of various syntactic categories, including not only common nouns but even DPs.[17] In order to save the analysis, especially with respect to phrasal categories, one would have to assume some kind of conversion process that converts arbitrary syntactic categories into nouns (Gallmann 1990; Wiese 1996). I cannot go into this debate here (cf. Meibauer 2003, 2007 for discussion); for the purposes of this article, it may suffice to say that the exact restrictions of an alleged conversion process are still unclear.

Third, under the analysis in (19), one would expect that either of the two given names would be combined equally with the surname to form an expression by which a speaker can refer to the person in question. This is clearly the case for (21b)–(21c), and it seems also to be acceptable for (22b)–(22c), with the quoted material being a nickname. However, it is not acceptable if the quoted expression contains a noun denoting a family relation, cf. (23c), or if it is a DP, cf. (24c).

| Johanna Maria Angermeier |

| Johanna Angermeier |

| Maria Angermeier |

| Johanna „Hansi“ Angermeier |

| Johanna Angermeier |

| „Hansi“ Angermeier |

| Johanna „Tante Hansi“ Angermeier |

| Johanna Angermeier |

| ?? „Tante Hansi“ Angermeier |

| Johanna „die Chefin“ Angermeier |

| Johanna Angermeier |

| ?? „Die Chefin“ Angermeier |

The unacceptability of (23c) and (24c) indicates that the quoted expression is not in a linear syntagmatic relation with the given name and/or the surname, but rather alternates as a whole with the given name-surname combination. Therefore, while it is not acceptable to refer to the person in question by (23c) or (24c), it is always acceptable to refer to them by using the quoted expression alone. An alternation analysis is also supported by the typographic facts observed above for non-inserted cases such as (14)–(17) (cf. Section 3).[18] Their typographic two-line representation can be taken as a reflex of the fact that the two expressions are perceived to be interchangeable at one and the same syntactic position, rather than being in a linear syntagmatic relation.

Together, our observations lend support to the assumption that the quoted expression in the nickname construction does not have the same syntactic status as the adjoint given name in the standard personal-name construction (18),[19] advocating an analysis under which the quoted expression does not fill a regular syntactic slot, but intrudes into the structure. It may thus be regarded as a case of parenthetical. Generally speaking, in a parenthetical, a sentence or phrase is inserted into another sentence or phrase, with the borders between a parenthetical and the receiving structure being marked graphically by en dashes or parentheses (or prosodically in spoken language) (Zifonun et al. 1997: 2363–2364), cf. (25).

| Peter – ich kenne ihn kaum – kommt morgen zu Besuch. |

| ‘Peter – I barely know him – is coming to see me tomorrow.’ |

| Peter (ich kenne ihn kaum) kommt morgen zu Besuch. |

| ‘Peter (I barely know him) is coming to see me tomorrow.’ |

Functionally, the parenthetical can be characterized as providing a comment on what is said in the receiving sentence (Zifonun et al. 1997: 2363). According to Fortmann (2021: 234), parentheticals are integrated into the linear structure of the receiving sentence, but display, at the same time, typical properties of syntactic disintegration. Rather than being computed linearly, the inserted expression in a parenthetical must be computed simultaneously with the rest of the syntactic chain (Bredel 2008: 146; Fortmann 2021).[20]

To summarize, the nickname construction is syntactically marked compared to the standard personal-name construction in German. As will be pointed out in more detail below, I assume that the marked structure triggers an inference such that the inserted expression is not the standard, or stereotypical, name of the person in question. On this account, the non-standard interpretation of the inserted expression, i.e., the ‘also called X’-interpretation, is conceived as being primarily syntactically induced. This analysis provides us with an answer to the puzzle of why the same meaning effect arises in both constructional variants, despite the fact that in standard contexts, parentheses and quotation marks are not interchangeable and do not induce the same kinds of interpretations. This is because the meaning effect is triggered by a syntactic process independently of the occurrence of certain graphematic means. We can demonstrate this by removing the parentheses or quotes from our constructions, as in (26)–(28).

| Ursula Uschi Vollmuth (originally in parentheses) |

| Dirk Würmchen Fuchs (originally in quotes) |

| Ralf möfpf Meyer (originally in quotes) |

On the one hand, the deletion results in a violation of the grammar of parentheticals, which requires that the borders between parenthetical and receiving structure are marked graphically (cf. Zifonun et al. 1997: 2363). Therefore, (26)–(28) can be regarded as orthographically deviant. On the other hand, the fact that we still are able to interpret these structures as being cases of the nickname construction, despite the lack of punctuation marks, indicates that the nickname interpretation is not primarily induced by the punctuation marks, but rather by the syntactic insertion of an element that can be interpreted as a nickname. If these considerations are on the right track, the question arises why quotation marks and parentheses occur in the construction, in the first place.

5 Functions of punctuation marks in the nickname construction

A possible, more general explanation for this question can be found in Gallmann’s (1985: 24) basic idea that punctuation marks are Grenzsignale ‘boundary signals’ whose function is in guiding the reader in the segmentation of textual units (cf. Section 2). Taking this as a starting point, we may assume that quotation marks and parentheses facilitate the computation of the inserted expression in the nickname construction, just as en dashes (or parentheses) facilitate the computation of a parenthetical within a sentence. This function will be of particular relevance in cases that are ambiguous between a standard reading and an ‘also called X’-reading. For example, in (29), without parentheses or quotes, we could not be sure whether Joe is a nickname (‘also called Joe’) or just a second given name of the person.

| Brunhilde Joe Wendt (originally in quotes) |

But even in cases that are not ambiguous, e.g., (26)–(28),[21] it is very likely that the computation of the inserted expression as a nickname is facilitated if parentheses or quotation marks are inserted.

However, the question is whether facilitating the computation of an (unusual) syntactic structure really is the prime contribution of both parentheses and quotation marks. According to Gallmann (1985), different kinds of boundary signals can relate to different kinds of textual units, which may be either syntactically or semantically defined. Both Gallmann (1985: 24, 32) and Bredel (2008: 139) regard parentheses (as well as en dashes) as being related to syntactic units, while they regard quotation marks as being related to semantic units. If this is true, then it should be the prime function of parentheses, but not of quotes, to mark the (unusual) syntactic structure of the nickname construction. Taking a look at parentheses, first, it seems that there is indeed evidence for this assumption.

Firstly, if the parentheses in the nickname construction are markers of parenthetical syntax, we would expect that they are blind with regard to what they enclose. The only thing that should matter is that something is inserted which can be interpreted as a comment on the rest of the structure. This may explain why parentheses in the nickname construction can enclose any alternative names, regardless of their status as nicknames, cf. (12)–(13).

Secondly, we would expect that parentheses may be replaced by other established parenthetical markers, in particular, by en dashes. In fact, we find the variant [10] in the corpus, with the attestation (30).

| Wilhemine – Helma – Daxenberger | [10-1] |

Thirdly, we would expect the expression in parentheses to occur construction internally, as parentheticals do, and not preposed, as this is no position for parentheticals. This is exactly what we find, cf., again, (12)–(13). Preposed expressions in parentheses, as in (31), would, in fact, be ungrammatical (cf. Bredel 2008: 145).[22]

| *(Tante Tinni) Hubertine Jansen 22 |

Postponed expressions in parentheses (cf. (16)), which cannot count as parentheticals, as far as they are not inserted into a sentence,[23] can be regarded as supplements in the right periphery, another domain of parentheses (cf. Bredel 2008: 146).

Finally, under this assumption, also the contrast between (32) and (33) is expected.

| Traurig nehmen wir Abschied von unserer // „Oma Hilde“. | [8-1] |

| ‘Sadly, we say farewell to our // “Granny Hilde”.’ | |

| Cuxhavener Nachrichten, 11 February 2020 | |

| *Traurig nehmen wir Abschied von unserer // (Oma Hilde). |

| ‘Sadly, we say farewell to our // (Granny Hilde).’ |

While there is one attestation of variant [8] in which a quoted expression is used autonomously in my corpus, cf. (32), there are no such attestations for any bracketed variant, cf. (33). An autonomously used bracketed expression would be treated as if it were not syntactically permeable, i.e., not a proper part of the sentence. This renders (33) ungrammatical.

If we now turn to quotation marks, it seems that from a purely syntactic point of view, quotation marks are not to be expected in the construction. Quotation marks do not (as contrasted with, e.g., en dashes) compete with parentheses when it comes to the marking of parentheticals, cf. the contrast between (6) and (34)–(35).

| Die Erde (wir wissen alle, dass sie keine Scheibe ist) dreht sich um die Sonne. |

| ‘Earth (we all know it is not a disk) revolves around the sun.’ |

| Die Erde – wir wissen alle, dass sie keine Scheibe ist – dreht sich um die Sonne. |

| ‘Earth – we all know it is not a disk – revolves around the sun.’ |

What is it then that licenses quotation marks in the nickname construction, and how can we account for their distribution in the nickname construction? Starting from the basic assumption that quotation marks are boundary signals related to the meaning of textual units, and utilizing Gutzmann and Stei’s (2011) pragmatic account of quotes, I will put forward the hypothesis that quotation marks in the construction are pragmatically licensed. They are used in order to indicate that further conversational implicatures need to be reconstructed by the reader. As a consequence, the use of quotation marks, compared to the use of parentheses, comes with additional meaning effects that go beyond the basic ‘also called X’-effect. I will further develop this view in Section 5.

Before, a cautious remark is in order. I do not claim that quotation marks cannot fulfill a function in facilitating syntactic processing as well. As argued above, comprehension of the nickname construction very likely will be easier in the b-variants of (36)–(37), i.e., if the inserted expression is graphematically marked, no matter whether by parentheses or by quotation marks.

| Ursula Uschi Vollmuth |

| Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth | [2-15] |

| Dirk Würmchen Fuchs |

| Dirk „Würmchen“ Fuchs | [1-4] |

However, instead of saying that facilitating syntactic processing is a genuine function of quotation marks, I would like to propose that this effect comes about due to functional overlap. In graphematics, it is a well-known phenomenon that punctuation marks may be deleted, governed by specific absorption rules, in text positions in which they are combined with other punctuation marks (Gallmann 1985; Nunberg 1990). For example, if a sentence ends with an ellipsis, the final full stop is deleted. However, this does not mean that the full stop simply disappears. Rather, the ellipsis may secondarily take over the function of the full stop, and thus become multifunctional. Similarly, we may assume that quotation marks in the nickname construction can take over the function of parentheses, i.e., the syntactic marking function, in addition to their primary pragmatic function. This fits with the observation of Gallmann (1985: 34) that it is primarily syntactic boundary signals that are deleted in favor of semantic boundary signals, with the latter taking over the function of the former.

Along these lines, we may analyze the constructional variant [6], which is instantiated once in my sample (cf. (38a)), as representing the “full” form, and the constructional variant [1], cf. (38b), as representing the “elliptic” form to which the absorption rule applies.[24]

| Christa („Nonna“) Hunger | [6-1] |

| Christa „Nonna“ Hunger | (corresponds to [1])24 |

The full form exhibits parentheses to mark the parenthetical structure and quotation marks to indicate further pragmatic effects. The elliptic form contains quotation marks in which two functions overlap: They (primarily) signal additional pragmatic effects and (secondarily) mark the parenthetical structure. I would thus like to propose that overtly quoted instances of the construction may be regarded as covertly bracketed and quoted instances. Evidence for this analysis comes from the fact that in all instances of the quoted nickname construction, one might add parentheses without changing the meaning.

On this account, it also makes perfect sense that an ordering of punctuation marks reverse to the one in (38a) does not exist in my sample (cf. also Bredel 2008: 139). This is because the parentheses, as syntactic markers, cannot take over the pragmatic function of the quotes.

| *Christa „(Nonna)“ Hunger |

| Christa (Nonna) Hunger |

While cases like (39) are not attested, cases like (40) can only have the ‘also called X’-effect, but cannot signal additional pragmatic effects. By contrast, (38b) can signal both kinds of effects.

6 Quotation marks in the nickname construction as minimal pragmatic indicators

In this section, I will sketch a pragmatic account of the quotation marks in the nickname construction along the lines of Gutzmann and Stei (2011), who propose a unified account of quotation marks as minimal pragmatic indicators. The hypothesis I will put forward is that quotation marks in the nickname construction indicate that further (generalized and particularized) conversational implicatures need to be reconstructed by the reader, leading to additional meaning effects that go beyond the basic ‘also called X’-effect.

In a nutshell, on my account, the (more general) additional meaning effect evoked by the quotes is a context-shift effect, that is, the quotation marks trigger a (generalized) conversational implicature such that the writer intended to allude to an original utterance situation (or a set of such situations) in which the quoted name was used to refer to or address the person in question. Depending on the particular context in which the nickname construction is used – e.g., a death notice or a news report –, additional particularized conversational implicatures may arise as to a certain emotional state of the writer. In this section, I go into more detail with the ‘also called X’-effect and the context shift effect and their pragmatic derivation. In Section 8, I will discuss the more particularized affective implicatures that may arise with the usage of the nickname construction.

Before I develop the pragmatic account in more detail, let me establish first the fact that there is, indeed, a context-shift effect in the construction with quotes, as compared to the construction with parentheses. As a test case, I will use the scenario in (41).

| Scenario: A popular music star named Udo Jürgens dies. Many years after his death, previously unknown documents are found indicating that his real name was not Udo, but Fritz. Later, a journalist writes an article about Udo Jürgens and refers to him as: |

| Udo (Fritz) Jürgens |

| Fritz (Udo) Jürgens |

| ?? Udo „Fritz“ Jürgens |

| Fritz „Udo“ Jürgens |

In this situation, the expressions (41a), (41b) and (41d) are perfectly fine, but (41c) is odd. This is exactly what my hypothesis predicts. (41a)–(41b) are equally fine because there is no additional context-shift effect in the bracketed variant. (41d) is fine because there are many original utterance situations in which Fritz was actually called Udo. But (41c) is odd, because the scenario is designed such that there are no utterance situations in which Udo was called Fritz; after all, nobody even knew, in his lifetime, that this was his name. By and large, this is also what the corpus data indicate. As shown in Section 3, we find parentheses both with nicknames and official names, but quotation marks only with nicknames (with one exception).[25] Under the context-shift analysis, this is exactly what we would expect: Given a competition between official name and nickname as to which one was actually used to address or refer to the person in question, it is the nickname that is predestined to take this role.

This context-shift effect can be accounted for by a model that takes quotation marks to be minimal pragmatic indicators. Gutzmann and Stei (2011) develop a unified pragmatic analysis of quotation, starting from the assumption that quotation is “everything between a pair of quotation marks” (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2651). The core idea of the account is to view quotation marks as minimal pragmatic indicators, defined as expressions that “do not have a proper semantic meaning” (minimal) and “indicate something regarding the utterance or the context of utterance” (indicator), “which has to be worked out by means of further pragmatic inferences” (pragmatic) (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2652). Under this view, what quotation marks do, from a reader’s perspective, is to “block the stereotypical interpretation of an expression, and thereby indicate that some alternative meaning ought to be inferred” (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2651). From a writer’s perspective, quotation marks “are used to convey that a non-standard interpretation of the quoted expression is required” (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2653). Given a Gricean cooperative principle and Horn’s (1984) “division of pragmatic labor”, which relies on an interaction between Q-principle and R-principle,[26] Gutzmann and Stei assume that

… a competent writer would not write “x” in case she wanted to convey only the standard interpretation of x. Analogously, a competent reader would not expect “x” to convey only the standard interpretation of x. (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2653)

Starting from there, Gutzmann and Stei sketch a two-staged derivational process triggered by the quotation marks. In the first stage, the quotation marks block the standard interpretation of the quoted expression. For example, for an utterance such as Peter’s “theory” is difficult to understand, the quotation marks indicate to the reader that the expression enclosed by quotation marks, “theory”, is to be interpreted in a non-standard way (i.e., not in the same way as theory). This inference is rather independent of the particular context of utterance. In the second stage, the specific context of utterance comes into play. This stage is modeled, by Gutzmann and Stei (2011: 2654), as a conversational implicature by which the reader may infer the specific contextual meaning of the utterance in a particular context. For instance, the utterance Peter’s “theory” is difficult to understand may receive the (context-specific) interpretation that Peter’s proposal, which Peter himself called a theory, in fact, is not a theory.

For our case, the derivational process can be modeled in much the same vein. However, what makes our case special, compared to the Peter’s “theory” example, is that the quoted expression in the nickname construction occurs at a syntactically unusual position. This makes things somewhat more complicated, and I will try to resolve the intricacies below (cf. Section 7). For the time being, I will assume that the blocking of the standard interpretation (Gutzmann and Stei’s first stage) comes about by the syntactic disintegration, in the first place, and is enhanced by the quotes. Depending on the syntactic category of the expression the syntactic insertion will be more or less obvious, and accordingly, the quotation marks will be more or less crucial as markers of the non-stereotypical interpretation. The enhancing analysis of quotes is in line with previous research showing that double marking in quotational contexts – e.g., in the X ist gut construction (Finkbeiner 2015) or in the sogenannt construction (Härtl 2018) – is not unusual (see also Predelli 2003).

We may then sketch the relevant processes, for the utterance (42), for instance, as follows.

| Wir trauern um Brunhilde „Joe“ Wendt. | [1-2] |

| ‘We mourn the loss of Brunhilde “Joe” Wendt.’ | |

| (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14/15 December 2019) | |

At the syntactic level, the disintegration of the expression Joe indicates to the reader that this expression must be computed in a different way, i.e., not linearly, but simultaneously with the rest of the chain. This promotes an interpretation according to which Joe has a status different from the rest of the chain, amounting to the ‘also called X’-effect, which emerges both in the quoted and the bracketed variants of the construction.

At this stage, quotation marks come into play. Following Gutzmann and Stei, we may take as a first step the blocking inference (which enhances the syntactically induced ‘also called X’-effect), i.e., that the reader infers from the fact that the writer marked the term Joe by enclosing it in quotation marks, and given the R-principle, that the writer wanted to convey something more or other than that Joe was the standard/stereotypical name of the deceased person. As a second step, the reader may infer, given the Q-principle, that there must be more to the name Joe than that it is some kind of alternative name because in this case, it would have sufficed to put the name into parentheses. Given that one of the most prominent usages of quotes is in indicating a context shift, and given that names are expressions that can be used to refer to people or to directly address people, the reader may infer that the writer intended to allude to an actual, original usage situation in which someone called the person by the name Joe. This amounts to the context shift effect, which emerges, as argued above, only in the variants with quotes.

While the ‘also called X’-effect, triggered by the blocking inference, is rather context-independent, this does not mean that one has to assume that it is encoded semantically. As Gutzmann and Stei (2011: 2654) point out, for a process labeled Gricean it is sufficient “that it is, in principle, possible to describe the inference by means of the CP [principle of cooperation, Author], the conversational maxims, and assumptions about the contextual settings”. It is not required to assume that the inference is drawn anew with every confrontation with quotation marks. However, if we want to maintain that this inference is not coded semantically, we should also be able to show that the expression with quotes expresses the same semantic content as its quotation mark-free counterpart. I will show that this is indeed the case in Section 7 below.

Furthermore, if we are dealing with pragmatically derived interpretations, these should be cancelable. However, this is not without problems, as Gutzmann and Stei point out. As they show with respect to the blocking inference in the Peter’s “theory” example, this inference cannot be canceled without “giving rise to the suspicion that the writer has stopped being cooperative” (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2655). This is because if the application of quotation marks indicates that a marked interpretation of the quoted expression is to be derived, it is odd to then try to cancel just that indication. Therefore, Gutzmann and Stei (2011: 2655) model this inference as a use-conditional (cf. Gutzmann 2015) meaning aspect. For our case, the same “suspicion” arises if we try to cancel the inference to the ‘also called X’-effect, cf. (43c).

| Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

| +> The writer wanted to convey something more or other than that Hansi was the standard/stereotypical name of the person referred to. |

| ??Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle, but I do not want to convey anything more or other than that Hansi was the standard/stereotypical name of the person referred to. |

Likewise, it seems that the context shift effect cannot be canceled straight away, cf. (44c).

| Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

| +> There is at least one original utterance situation in which Johanna Angermeier actually was called Hansi. |

| ??Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle, but I do not want to say that there was at least one original utterance situation in which Johanna Angermeier actually was called Hansi. |

However, at closer inspection, the apparent impossibility to cancel the implicature, cf. (44c), turns out to be mainly an effect of the type of expression that is quoted. If a proper noun (or a derivative of a proper noun) is quoted, as in Johanna „Hansi“ Angermeier, there is virtually no other interpretation possible than the interpretation that someone used this name to refer to (or address) the person in question, because proper nouns are, at least according to the standard Millian view, directly referential expressions. However, if a common noun is quoted, which allows for other, ‘intensional’ interpretations as well, the implicature may be canceled, cf. (45c).

| Plötzlich und unerwartet, für uns alle unfassbar, verstarb Dirk „ Würmchen” Fuchs. |

| ‘Suddenly and unexpectedly, unfathomable for all of us, Dirk “Würmchen” Fuchs passed away.’ |

| (Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 25 February 2020) |

| +> There is at least one original utterance situation in which Dirk Fuchs actually was called Würmchen. |

| Suddenly and unexpectedly, unfathomable for all of us, Dirk “Würmchen” Fuchs passed away, but I do not want to say that there was at least one original utterance situation in which Dirk Fuchs actually was called Würmchen. I just wanted you to know that he really loved wine gum worms. |

This does not appear to be odd because, in contrast to (45c), there is no doubt about the writer being cooperative. We may take this as evidence that the context shift effect is, in fact, a conversational implicature. I propose to model it as a generalized conversational implicature (cf. Levinson 2000: 16–17) because it seems to emerge rather standardly across contexts. By contrast, the ‘also called X’-effect seems to be a conventional use-conditional effect bound to the quotation marks, which in the case of our construction overlaps with an effect induced by syntactic insertion. The context-shift effect may, in addition, give rise to further, more particularized conversational implicatures that differ from context to context (Levinson 2000). These amount to specific emotional states of the writer that are to be inferred from the quotational use. I will go into more detail with these affective implicatures in Section 8 below.

7 Some refinements

So far, I have sketched an interface account that models the meaning constitution of the nickname construction as a result of the interplay between syntax, punctuation, and pragmatics. On this account, syntactically, a linguistic expression – of indeterminate category – is inserted, but not integrated into a personal-name construction, resulting in a parenthetical structure. Graphematically, the parenthetical structure is made visible by parentheses, which mark the syntactic boundaries of the parenthetical. The parentheses guide the reader in computation, indicating that the inserted expression is to be processed not linearly, but simultaneously with the rest of the chain. Eventually, this will result in the ‘also called X’-effect. Quite independently of these processes, the expression may, additionally, be enclosed in quotes. This will lead to a double marking of the expression, by quotes and by parentheses. Following a more general graphematic absorption rule, the parentheses may be absorbed in favor of the quotes, which take over the structural marking function of the parentheses, in addition to their prime, pragmatic function. The prime, pragmatic function of the quotes is in indicating that a non-stereotypical interpretation of the quoted expression is to be inferred by the reader. This is congruent, in part, with the ‘also called X’-effect triggered by syntax, but goes beyond it in inviting further conversational implicatures, in particular, a context shift effect. As I have shown in the previous sections, this picture can account for most of the distributional properties of the data.

However, two questions are still open: A first question concerns the semantic status of the quoted expression; a second question concerns the kind of quotation at hand. I will pursue both questions in due order, thus providing some refinements to the account.

The first question is directly related to the minimal pragmatic indicator account of quotation marks (Gutzmann and Stei 2011). This account predicts that an expression enclosed in quotation marks does not differ semantically from its quotation mark-free counterpart. That is, if quotation marks have use-conditional meaning (and, additionally, trigger further implicatures), which is what this account assumes, then they must not affect truth conditions. For examples such as (46), this seems to hold. Descriptively, (46a) expresses no more than (46b); additional effects arising in (46a) (‘I don’t think it is a theory’) do not affect the truth-conditional layer, but operate on the level of the utterance (cf. Gutzmann 2015; Potts 2007).

| Peter’s “theory” is difficult to understand. |

| Peter’s theory is difficult to understand. |

We can demonstrate this by a negation test. As a semantic operator, negation only affects truth-conditional, but not use-conditional content, cf. the contrast between (47a)–(47b).

| Peter’s “theory” is not difficult to understand. (It is easy to understand.) |

| Peter’s “theory” is not difficult to understand. (#It is just a hypothesis.) |

A parallel case is (48): We may argue that (48a) is descriptively equivalent to (48b); additional effects that arise in (48a) (‘I dislike Germans’) are to be modeled at utterance level.

| Nietzsche was a Kraut. |

| Nietzsche was a German. |

However, if we take a look at the nickname construction, things seem to be more complicated. It is problematic, e.g., to say that (49a) descriptively (referentially) expresses the same as (49b).

| Suddenly and unexpectedly, unfathomable for all of us, Dirk “Würmchen” Fuchs passed away. |

| Suddenly and unexpectedly, unfathomable for all of us, Dirk Würmchen Fuchs passed away. |

This is because, as pointed out above, if the quotation marks are deleted, the parenthetical syntax of the nickname construction is not marked anymore; even if we still may interpret (49b) as an instance of the nickname construction, it clearly violates orthographic rules, which makes it difficult to ascribe it a truth-value.

The difficulties in comparing the semantic contents of the quoted expression with its non-quoted counterpart in (49) obviously have to do with the unusual syntactic position of the quoted expression. In order to resolve this problem, I would like to propose that what is realized here as one sentence containing a parenthetical construction corresponds, on the level of semantics, to two, simultaneously realized propositions. I will take, again, the introductory example (1), here repeated as (50), to illustrate this. (50) may be analyzed as entailing the two propositions (51a)–(51b).

| Johanna “Hansi” Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

| Johanna Angermeier has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

| “Hansi” has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

If we split the nickname construction into its two propositions, and then apply the deletion test, the test works. The relevant sentence for the test is (51b). With regard to (51b), the assumption holds that the expression with quotation marks is descriptively equivalent to its quotation mark-free counterpart, cf. (52a)–(52b).

| “Hansi” has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

| Hansi has passed away after a short, hard struggle. |

At this point, it is interesting to compare the quoted variant, again, to the bracketed variant. As becomes clear from the introductory example (2), here repeated as (53), the bracketed variant does not allow for an analysis corresponding to the one in (51)–(52). While (53) entails (54a), it does not entail (54b) (which is ungrammatical).

| Suddenly and unexpectedly to all of us, Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth left for good after a short, severe illness. |

| Suddenly and unexpectedly to all of us, Ursula Vollmuth left for good after a short, severe illness. |

| *Suddenly and unexpectedly to all of us, (Uschi) left for good after a short, severe illness. |

If we want to analyze (53) into two propositions, we must remove the parentheses, cf. (54b′). It is correct to say that (53) entails (54a) and (54b′).

| Suddenly and unexpectedly to all of us, Uschi left for good after a short, severe illness. |

This is a strong argument for the assumption that parentheses are structural boundary signals, while quotation marks are boundary signals operating on the meaning of the expression. The only function of parentheses is to mark the parenthetical. As soon as the parenthetical is resolved, the parentheses must disappear. By contrast, the quotation marks remain in place even if the parenthetical is resolved. This indicates that quotation marks are independent of the parenthetical.

I will turn to the second question that is still open, namely, the question of what kind of quotation we are dealing with, and, closely related to it, whether the quoted expression in the nickname construction is used or mentioned. As to the latter aspect, I have already argued that (52a) is descriptively equivalent to (52b). This indicates that the quoted expression must contribute to the denotation of the sentence in which it is embedded, and therefore cannot be only mentioned. Arguably, this fact is obscured in the “unsplit” nickname construction (50), which makes it appear as if the quoted expression would be merely mentioned. After all, it might appear as if in (50), the reference is accomplished solely by Johanna Angermeier, while “Hansi” operates on a different layer of meaning. However, this is an effect of the unusual syntax of the construction which requires parallel processing. If one resolves the structure into the two propositions included, this effect vanishes.

Current approaches to quotation distinguish five varieties of quotation with quotation marks (for an overview, cf. Brendel et al. 2011), cf. (55)–(59).[27]

| “Cats” is a noun. (pure quotation) |

| “I don’t like your attitude”, John said. (direct quotation) |

| Miranda said that Joan’s new boyfriend was “not as dull as expected”. (mixed quotation) |

| Peter’s “theory” is difficult to understand. (scare quotation) |

| We sell “fresh” pastry. (emphatic quotation) |

| (Gutzmann and Stei 2011: 2651) |

Usually, for pure and direct quotation – subsumed in Recanati’s (2001) class of “closed quotations” – it is assumed that the quoted expression is not used, i.e., is not contributing its semantic content to the sentence in which it is used. For mixed, scare, and emphatic quotation – subsumed in Recanati’s (2001) class of “open quotations” –, it is usually assumed that the quoted expression is used, i.e., contributes its semantic content to the sentence in which it is used. To exemplify this, while (55) does not inform us about cats, (58) informs us about Peter’s theory.

If we assume that the quoted expression in the nickname construction is used, the question is whether it is an instance of a mixed, a scare, or an emphatic quotation. The three varieties basically differ in whether the quoted expression refers to an original utterance or not. Emphatic quotation comes with an effect of emphasizing the expression, e.g., in (59), it is emphasized that the pastry is really fresh. No reference is made here to an original utterance. By contrast, in a mixed quotation, there is reference to an original utterance, while in a scare quotation, reference to an original utterance is one of several options. For example, while one would infer from the quotes in (57) that the speaker wanted to signal that not as dull as expected was part of Miranda’s original utterance, (58) may lead to a number of distinct interpretations, among them the interpretation that Peter (or someone else) had previously called the proposal a theory, or the interpretation that the writer – nobody having actually called the proposal a theory before – simply wanted to express their reservation regarding the appropriateness of this term.

For the quotes in the nickname construction, I argued above that they evoke a context shift-interpretation, i.e., that readers may infer that the writer by using quotes intended to allude to an original utterance situation in which the nickname was used to refer to or address the person in question. If this is correct, we may exclude emphatic quotes as an option. The question then is whether we are dealing with mixed or scare quotation. For mixed quotation, normally the requirement must be fulfilled that there is some indication of the utterance being a speech report and that there is a source to which the quoted expression may be attributed. For example, in (57), there is a verb of saying, indicating that we are dealing with a speech report, and it is quite clear that Miranda is the source of the quoted expression. Neither of those requirements is fulfilled by the quotation in the nickname construction. Therefore, it seems that scare quotation is the best fit. While scare quotation allows for an interpretation evoking an original utterance situation, it does not require a determinate source of the original utterance, or a linguistic indicator of a speech report (cf. Predelli 2003).

8 Particularized conversational implicatures: death notices versus news reports

In this section, I will further develop the assumption that from utterances containing the quotational nickname construction, a reader may draw additional, more particularized conversational implicatures. To this end, I will discuss different contexts in which the nickname construction may be used and point to more specific meaning aspects that may arise within the different contexts.

If we take it that the quoted expression triggers a generalized implicature such that the writer intended to allude to an original utterance situation in which this expression was actually used, it is suggestive for the reader to draw further inferences as to who used this name in which situations. In other words, if the basic intention of a writer is to allude to a particular naming practice by inserting a nickname into the personal-name construction, the question remains (to be inferred by the reader) who the performers of this naming practice are. This question may be answered differently in different contexts.

I have so far focused on a particular genre, namely, death notices in German daily newspapers. While originally, death notices were published to announce the death of a person, present-day death notices primarily have the main function to make public the grief of the surviving members of the family, friends, or colleagues (cf. Linke 2001). Typically, death notices are commissioned by those whose grief is being announced. While they are not writers in a narrow sense, as they are typically assisted by a funeral home and an editor at the newspaper, we may speak of them as senders. Now, crucially, in the context of a death notice, it is highly plausible for a reader to identify the sender(s) of the death notice with the (former) users of the nickname. For example, in the context of the death notice (60), it is highly plausible to assume that the surviving family members, who are also mentioned by name in the lower part of the notice, are those who used to call the deceased person by the name “Ursel”.[28]

|

| (Frankfurter Rundschau, 18/19 January 2020)28 |

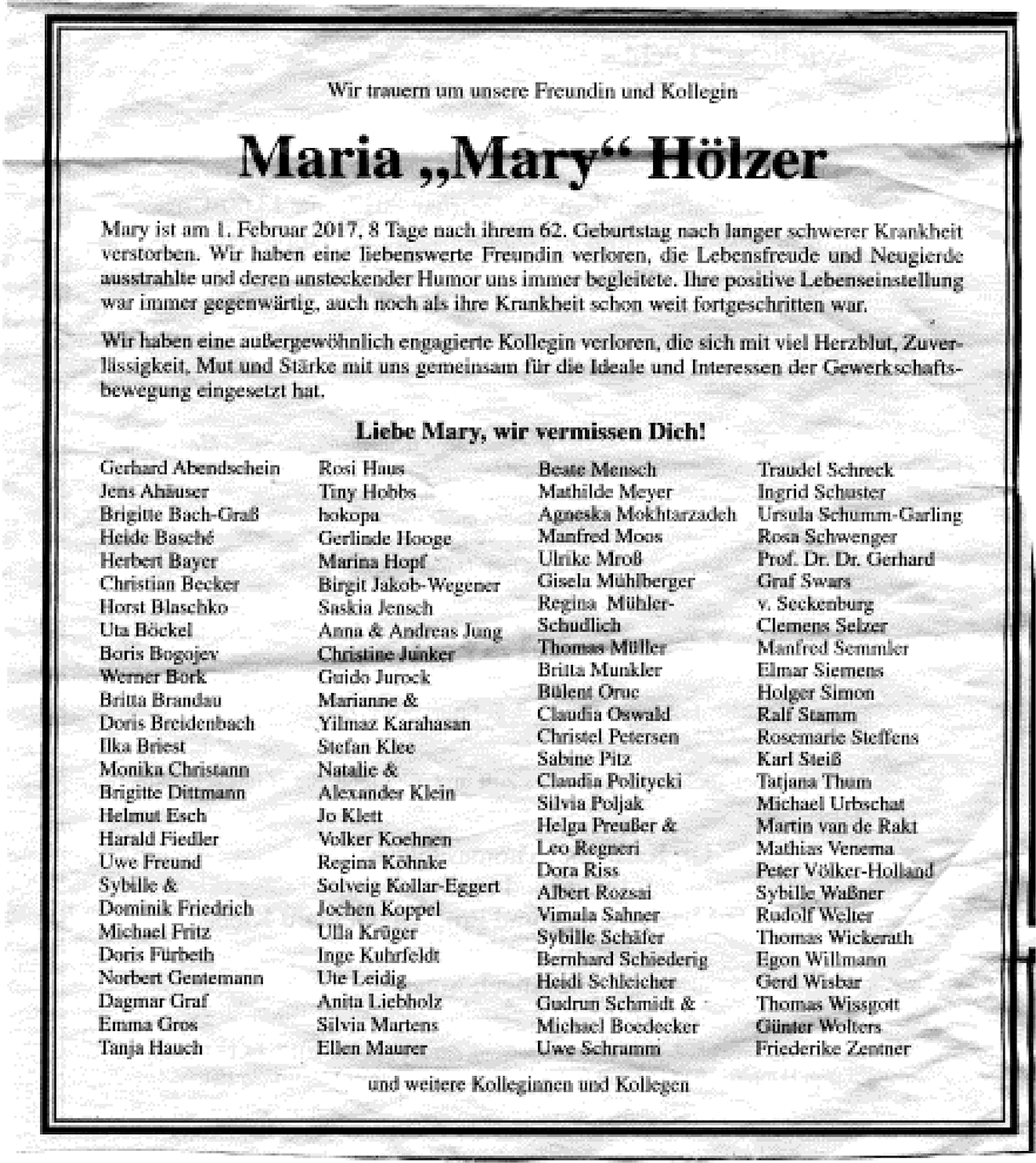

This implicature is even more strongly indicated in the death notice (61), in which we find the constructional nickname Mary also used, in a personal letter-like style, as an address term above the list of friends and colleagues (Liebe Mary, wir vermissen Dich!, ‘Dear Mary, we miss you!’).[29]

|

| (Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 February 2017)29 |

In cases where the quoted expression is a close apposition of a term denoting a family relation and a nickname (Tante Otti, ‘aunt Otti’), as in (62), it is highly suggestive for a reader to draw the inference that the senders of the death notice, who must be nieces or nephews, or grandnieces or grandnephews of the deceased, are those who used to call her Tante Otti.

Against this backdrop, the identification of the sender(s) of the death notice with the (former) users of the nickname will be very likely to give rise to a particularized conversational implicature such that the senders of the death notice were in a close emotional relationship with the deceased. This is because the practice of calling someone by a nickname, which is, as it were, echoed in the death notice, is an expression of a rather intimate relationship between the user and the bearer of the nickname. To evoke the impression in the reader that the sender was emotionally close to the deceased is thus a prime effect of the use of quotation marks in death notices, which also distinguishes it markedly from the use of parentheses.

|

| (Frankfurter Rundschau, 18/19 January 2020)[30] |

This becomes clear if we compare (61) with (63). While the use of “Mary” in (61) is affective, the use of (Ria) in (63) is not; it is rather neutral.[31] This is exactly what my account would predict. The use of (Ria) is not affective, because a bracketed expression does not give rise to a context shift implicature. Therefore, there is no allusion to an original usage situation, and therefore, no further inferences need to be drawn regarding the bearer of the nickname.[32]

|

| (Frankfurter Rundschau, 14/15 January 2017)32 |

Having come so far, the question is still open why the affective implicature that may arise in usages of the quotational nickname construction should be modeled as a particularized conversational implicature. A particularized conversational implicature is a conversational implicature that is highly context dependent, as compared to a generalized conversational implicature, which is relatively context independent (Levinson 2000: 16–17). In order to demonstrate that it is highly context dependent what kind of affective implicature a reader will draw from the usage of a quoted nickname, let us have a comparative look at a different genre in which the quotational nickname construction may be used, namely, in news reports.

|

| (Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 1 December 2016)33 |

Whereas death notices are usually about “ordinary people”, [33]and commissioned by family members, news reports are usually about people of public interest and written by journalists. In the context of a news report, different implicatures may be drawn from the usage of the quotational nickname construction. For example, from the caption (64), taken from a short article about the somewhat eccentric Austrian building contractor Richard Lugner, called Mörtel ‘morter’, who had recently divorced his fifth wife, readers will probably not infer that the journalist who wrote the caption was in a close emotional relationship with Richard Lugner (nor that she was with Lugners fifth wife, “Spatzi”).

Rather, this use of Richard “Mörtel” Lugner will be interpreted such that the writer intended to echo a naming practice of a group of speakers that does not (necessarily) include herself. This may either yield an interpretation by which the writer wanted to distance herself from the naming practice echoed in the construction, or an interpretation by which the writer wanted to affiliate herself with this naming practice. Which attitude the reader will infer depends on various aspects of the context, for example, whether it is a positively or negatively evaluating context. In any case, the crucial difference between the news reports genre, as exemplified in (64), and the death notice genre, as exemplified in (60)–(63), is that quotation marks in the nickname construction in death notices suggest an inference to the identification of the performer of the naming practice and the sender of the utterance, triggering an emotional closeness implicature, while quotation marks in the nickname construction in news reports do not suggest an inference to the identification of the performer of the naming practice and the sender of the utterance, giving rise to different kinds of (distancing or affiliating) affective interpretations.

9 Summary

In this paper, I have examined the broader issue of how quotational meanings emerge with respect to a particular nickname construction in German. I started from the observation that while there is variation between quotation marks and parentheses in the construction, the basic ‘also called X’-effect seems to remain constant, which raises the question of what exactly the meaning of the (variants of the) nickname construction is and what quotation marks and parentheses, respectively, contribute to this meaning. The aim of the paper was to provide a comprehensive account of this variation by unfolding the complex interplay between syntax, graphematics (punctuation), and pragmatics in the meaning constitution of the construction.

Based on a close examination of an example corpus from death notices, I developed the view that the choice of quotation marks or parentheses is governed by two different, independent processes that partly overlap in the construction. While the parentheses in the nickname construction are graphematic means marking a parenthetical structure in syntax in order to guide the reader in the computational process, quotation marks are graphematic means marking the need of reconstructing specific conversational implicatures. Accordingly, the two variants of the construction are not functionally equivalent. While both quotation marks and parentheses play a role in indicating marked syntax, leading to the ‘also called X’-effect, the quotation marks are richer in meaning, triggering an additional context shift-effect, as well as further, particularized conversational implicatures as to a particular affective state of the writer. The analysis lends support to the view developed by Gallmann (1985) and Bredel (2008) that parentheses are boundary signals operating on syntactic structure, while quotation marks are boundary signals operating on the meaning of linguistic expressions.

Taken together, I hope to have shown that a close linguistic examination of quotation as occurring within a particular syntactic construction may provide valuable new insights into how quotational meanings emerge. At the same time, the analysis as carried out in this paper may further promote interface theories of quotation that take into account its complex interrelations with syntax, graphematics, and pragmatics.

Appendix 1: Overview of constructional variants

| Constructional variant | Number of attestations | |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | N1 „X“ N2 | 19 |

| [2] | N1 (X) N2 | 16 |

| [3] | N1 N2 (X) | 2 |

| [4] | N1 N2 „X“ | 4 |

| [5] | „X” N1 N2 | 4 |

| [6] | N1 („X”) N2 | 1 |

| [7] | N1 N2 X | 1 |

| [8] | „X” | 1 |

| [9] | X (N1 N2) | 1 |

| [10] | N1 – X – N2 | 1 |

| Total | 50 |

Appendix 2: Example corpus

| Constructional variant [1]: N1 „X“ N2 | |||

| [1-1] | Barbara „Bertchen“ Schmitz | Super Sonntag, 19 January 2020 | |

| [1-2] | Brunhilde „Joe“ Wendt | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14/15 December 2019 | |

| [1-3] | Burkhard „Flax“ Flachmann | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 19/20 December 2020 | |

| [1-4] | Dirk „Würmchen“ Fuchs | Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 25 February 2020 | |

| [1-5] | Elisabeth „Liesel“ Berg | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 24 December 2021 | |

| [1-6] | Georg „Schorsch“ Diehl | Frankfurter Rundschau, 14/15 January 2017 | |

| [1-7] | Gertrud „Trudy“ Zink | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 16 April 2018 | |

| [1-8] | Günter „Stopei“ Roß | Darmstädter Echo, 2 October 2021 | |

| [1-9] | Harry „der Chef“ Engelke | Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 January 2020 | |

| [1-10] | Johanna „Hansi“ Angermeier | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 19 April 2018 | |

| [1-11] | Karl „Charly“ Petri | Frankfurter Rundschau, 4/5 March 2017 | |

| [1-12] | Klaus „Maggi“ Marglowski | Rheinische Post, 23 January 2021 | |

| [1-13] | Maria „Annemarie“ Wellnhammer | Nürnberger Nachrichten, 24 May 2017 | |

| [1-14] | Maria „Floh“ Lindermaier-Färbinger | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 21/22 April 2018 | |

| [1-15] | Maria „Mary“ Hölzer | Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 February 2017 | |

| [1-16] | Ralf „möfpf“ Meyer | Frankfurter Rundschau, 22 February 2017 | |

| [1-17] | Ulrich „Lobj“ Lobjinski | Frankfurter Rundschau, 14/15 January 2017 | |

| [1-18] | Ursula „Ursel“ Eigelsheimer | Frankfurter Rundschau, 18/19 January 2020 | |

| [1-19] | Ursula „Uschi“ Blaha | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 30/31 January 2021 | |

| Total number of attestations | 19 | ||

| Constructional variant [2]: N1 (X) N2 | |||

| [2-1] | Adolf (Adi) Siegel | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 24 December 2021 | |

| [2-2] | Ankica (Anna) Popke | Super Sonntag, 16 February 2020 | |

| [2-3] | Bubel (Max) Schubert | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 23 September 2017 | |

| [2-4] | Cornelia (Conny) Meister | Frankfurter Rundschau, 14/15 January 2017 | |

| [2-5] | Dr. Josef (Pepi) Rosenfelder | Frankfurter Rundschau, 16 January 2020 | |

| [2-6] | Günter (Utz) Ullrich | Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 January 2020 | |

| [2-7] | Joachim (Jochen) Wilke | Darmstädter Echo, 9 October 2021 | |

| [2-8] | Johann (Hans) Salz | Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 January 2020 | |

| [2-9] | Johanna (Hanni) Steinbrenner | Frankfurter Rundschau, 17 February 2017 | |

| [2-10] | Käthi (Katharina) Schwinn | Frankfurter Rundschau, 11/12 January 2020 | |

| [2-11] | Lorenz (Lori) Hölzl | Frankfurter Rundschau, 13 January 2017 | |

| [2-12] | Margarete (Margot) Nikolaus | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 4 December2021 | |

| [2-13] | Marie (Ria) Fischer | Frankfurter Rundschau, 14/15 January 2017 | |

| [2-14] | Otti (Ottilie) Dietz | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 23 September 2017 | |

| [2-15] | Ursula (Uschi) Vollmuth | Frankfurter Rundschau, 17 February 2017 | |

| [2-16] | Wilhelm Philipp (Willi) Menges | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 14 December 2021 | |

| Total number of attestations | 16 | ||

| Constructional variant [3]: N1 N2 (X) | |||

| [3-1] | Gerda Pfeiffer //34 (Schwester Gerda) | Darmstädter Echo, 13 November 2021 | |

| [3-2] | Hubertine Jansen // (Tante Tinni) | Super Sonntag, 25 November 2018 | |

| Total number of attestations | 2 | ||

| Constructional variant [4]: N1 N2 „X” | |||

| [4-1] | Katharina Fuhr „Tante Käthe“ | Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, 15 July 2019 | |

| [4-2] | Margarete Luise Beck // „Gretel“ | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 26 April 2017 | |

| [4-3] | Marie Nold // „die Glocke Marie“ | Darmstädter Echo, 13 November 2021 | |

| [4-4] | Vincenzo Lania // „Enzo“ | Allgemeine Zeitung Mainz, 24 December 2021 | |

| Total number of attestations | 4 | ||

| Constructional variant [5]: „X” N1 N2 | |||

| [5-1] | „Kako“ // Ulla Kalbfleisch-Kottsieper | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 5/6 December 2020 | |

| [5-2] | „Oma Lene“ // Maria Magdalena Stephan | Darmstädter Echo, 28 September 2021 | |

| [5-3] | „Schote“ // Brita Gromöller | Darmstädter Echo, 30 October 2021 | |

| [5-4] | „Tante Otti“ // Ottilie Schumacher | Frankfurter Rundschau, 18/19 January 2020 | |

| Total number of attestations | 4 | ||

| Constructional variant [6]: N1 („X”) N2 | |||

| [6-1] | Christa („Nonna“) Hunger | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 25/26 January 2020 | |

| Total number of attestations | 1 | ||

| Constructional variant [7]: N1 N2 X | |||

| [7-1] | Christine Biedermann-Tautfest // Krickel | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 23/24 January 2021 | |

| Total number of attestations | 1 | ||

| Constructional variant [8]: „X” | |||

| [8-1] | „Oma Hilde“ | Cuxhavener Nachrichten, 11 February 2020 | |

| Total number of attestations | 1 | ||

| Constructional variant [9]: X (N1 N2) | |||

| [9-1] | Weigi (Michael Weig) | Frankfurter Rundschau, 18/19 January 2020 | |

| Total number of attestations | 1 | ||

| Constructional variant [10]: N1 – X – N2 | |||

| [10-1] | Wilhelmine – Helma – Daxenberger | Süddeutsche Zeitung, 20/21 February 2021 | |

| Total number of attestations | 1 | ||

| Total | 50 | ||

References[34]

Ashley, Leonard R. N. 1996. Middle names. In Ernst Eichler (ed.), Namenforschung. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Onomastik, vol. 2, 1218–1221. Berlin & New York: De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Bredel, Ursula. 2008. Die Interpunktion des Deutschen. Ein kompositionelles System zur Online-Steuerung des Lesens. Tübingen: Niemeyer.Search in Google Scholar

Bredel, Ursula. 2011. Interpunktion. Heidelberg: Winter.Search in Google Scholar

Brendel, Elke, Jörg Meibauer & Markus Steinbach. 2011. Exploring the meaning of quotation. In Elke Brendel, Jörg Meibauer & Markus Steinbach (eds.), Understanding quotation (Mouton Series in Pragmatics 7), 1–34. Berlin & Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110240085.1Search in Google Scholar

Cappelen, Herman & Ernest Lepore. 1997. Varieties of quotation. Mind 106(423). 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/106.423.429.Search in Google Scholar

Cappelen, Herman & Ernest Lepore. 2007. Language turned on itself: The semantics and pragmatics of metalinguistic discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199231195.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Davidson, Donald. 1979. Quotation. Theory and Decision 11(1). 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00126690.Search in Google Scholar

De Brabanter, Philippe. 2013. A pragmaticist feels the tug of semantics: Recanati’s “Open quotation revisited”. Teorema 32(2). 129–147.Search in Google Scholar

Finkbeiner, Rita. 2015. “Ich kenne da so einen Jungen … kennen ist gut, wir waren halt mal zusammen weg.” On the pragmatics and metapragmatics of X ist gut in German. In Jenny Arendholz, Wolfram Bublitz & Monika Kirner-Ludwig (eds.), The pragmatics of quoting now and then, 147–176. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110427561-008Search in Google Scholar

Finkbeiner, Rita. 2021. Sprechakttheoretische Überlegungen zur Typographie – am Beispiel von Presseüberschriften. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 49(2). 244–291. https://doi.org/10.1515/zgl-2021-2029.Search in Google Scholar

Finkbeiner, Rita & Jörg Meibauer. 2016. Boris “Ich bin drin“ Becker (‘Boris I am in Becker‘). Syntax, semantics and pragmatics of a special naming construction. Lingua 181. 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2016.04.006.Search in Google Scholar

Fortmann, Christian. 2021. Non-Syntax in der Satzsyntax – nicht-integrierte Parenthesen als ein Phänomen der Sprachverarbeitung. In Robert Külpmann & Rita Finkbeiner (eds.), Neues zur Selbstständigkeit von Sätzen, 233–256. Hamburg: Buske.Search in Google Scholar

Gallmann, Peter. 1985. Graphische Elemente der geschriebenen Sprache. Grundlagen für eine Reform der Orthographie. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783111630380Search in Google Scholar

Gallmann, Peter. 1990. Kategoriell komplexe Wortformen: das Zusammenwirken von Morphologie und Syntax bei der Flexion von Nomen und Adjektiv. Tübingen: Niemeyer.10.1515/9783111376332Search in Google Scholar

Grice, Herbert Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Peter Cole & Jerry Morgan (eds.), Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts, 41–58. New York: Academic Press.10.1163/9789004368811_003Search in Google Scholar

Gutzmann, Daniel. 2015. Use-conditional meaning. Studies in multidimensional semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198723820.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Gutzmann, Daniel & Erik Stei. 2011. How quotation marks what people do with words. Journal of Pragmatics 43. 2650–2663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.03.010.Search in Google Scholar

Härtl, Holden. 2018. Name-informing and distancing sogenannt ‘so-called’: Name-mentioning and the lexicon-pragmatics interface. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 37(2). 139–169. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfs-2018-0008.Search in Google Scholar

Horn, Laurence R. 1984. Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inferencing: Q-based and R-based implicature. In Deborah Schiffrin (ed.), Meaning, form, and use in context: Lingusitic applications, 11–42. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.Search in Google Scholar