Abstract

Every language has at least two demonstratives or deictic terms, a proximal one and a distal one, and some languages in addition have a medial (or some other additional) demonstrative. Demonstratives exhibit a variety of grammatical and pragmatic functions, and they also serve as major sources for the development of various important grammatical devices, such as copulas, relativizers, definite articles, and complementizers. However, lexical sources for demonstratives remain largely unknown, as do the mechanisms leading to their emergence. Based on a database of more than 1000 subdialects of Chinese, this article demonstrates that the distal demonstratives in these subdialects are phonologically derived from their corresponding proximal demonstratives, which were themselves grammaticalized from classifiers in Late Medieval Chinese. This finding identifies a new type of mechanism leading to the emergence of grammatical items: within a pair of two closely related grammatical elements, the basic and unmarked member originates from a lexical source, and gives rise to the other member through certain phonological principles. The domain of demonstratives thus illustrates how processes of grammaticalization and phonological derivation can interact giving rise to the emergence of new grammatical forms.

1 Introduction

The importance of research on demonstratives cannot be overemphasized for the following three reasons (Diessel 1999: 8–9). First, demonstratives are the sources for various grammatical markers, such as copulas, relativizers, definite articles, complementizers, and third person pronouns. These grammaticalization paths are widely attested in languages across the world (Harris and Campbell 1995: 284; Heine and Reh 1984: 271; Heine et al. 1991: 221; Hopper and Traugott 2003: 4; Lehmann 1995: 137–143). Second, demonstratives are usually considered grammatical devices because they exhibit multiple grammatical and pragmatic functions, but no evidence has been found in any language that they developed from lexical sources, or any other sources (Himmelmann 1997: 20). The two questions raised by Greenberg (1978) thus remain unresolved: How do demonstratives arise in the first place? What are the mechanisms governing their emergence?[1] Diessel (1999: 115–155) even claims that demonstratives may represent a particular source from which grammatical markers may emerge. Third, demonstratives are regarded as ‘conventional signs’ and are by nature symbolic, i.e. they are not onomatopoeias or instances of sound symbolism (Van Langendonck 2007). However, they are among the very few grammatical items that exhibit a non-arbitrary relationship between phonological form and meaning, as in the case of onomatopoeias and sound symbolism (Johansson and Zlatev 2013; Johansson et al. 2020a, 2020b; Joo 2020). Examining 26 geographically unrelated languages, for instance, Woodworth (1991) finds that there is a strong correlation between proximal and distal demonstratives and their phonological make-up: proximal demonstratives tend to use the high front vowel [i], while distal ones mostly use the low back vowel [a].

Although they share semantic and syntactic commonalities, proximal and distal demonstratives developed through completely different mechanisms in Chinese. The proximal demonstratives were typically first grammaticalized from classifiers, and then gave rise to the corresponding distal demonstratives by means of certain phonological principles involving iconicity between speech sounds and distance. This is a new type of mechanism for the emergence of grammatical items that stands in contrast to grammaticalization processes, and that can explain the non-arbitrary relationship between the phonological forms and the meanings of the two demonstratives in numerous languages.

Compared to other functional categories, demonstratives display some peculiar properties. Proximal, distal, and medial demonstratives[2] must be phonologically spelled out; in other words, they cannot exhibit a markedness contrast as observed in singular vs. plural forms, such as one book vs. two books. It is difficult to imagine that the proximal and distal demonstratives in a given language could have developed from two independent lexical sources at exactly the same time, because daily communication requires both of them to be ready for use. Therefore, processes of both grammaticalization and phonological derivation are necessary for the emergence of grammatical items such as demonstratives.

In order to see this, let us review different grammatical categories and their marked and unmarked forms.

Type I: Grammatical categories that are isolated and independent, such as the future marker be gonna in English and the disposal morpheme bǎ in Chinese. Their emergence does not involve any other grammatical changes. They are generally grammaticalized from lexical sources.

Type II: Grammatical categories with two contrasting grammatical items. For instance, in almost all languages with a singular-plural distinction, the plural nouns are marked while the singular nouns are unmarked, e.g., one book vs. two book s in English (Corbett 2004: 19). Thus, only the marked member of the opposition has to be grammaticalized from a lexical source, e.g., the plural marker.

Type III: Grammatical categories with two or more loosely related grammatical items. For instance, the English definite article the originated from the demonstrative that, and its indefinite article a/an originated from the numeral one (Heine and Kuteva 2002: 109; Hopper and Traugott 2003: 119). However, they are not semantically or syntactically parallel; specifically, the can modify singular as well as plural nouns, while a/an can precede singular nouns only. In addition, they are not found in all languages. Many languages have a definite article only (Diessel 2006), and some languages only have indefinite articles (see for instance Dryer 2013). For this type of functional domain, the two grammatical items may develop from more than one lexical domain, as the English case shows.

Type IV: Grammatical categories with two intrinsically contrasting grammatical items. A typical example of this type is gender. A language cannot have a single gender category (e.g., feminine) without having a contrasting category (e.g., masculine). Since genders often derive from sex distinctions in human beings and animals, they can have two lexical sources. For instance, the feminine gender may originate from the word ‘women’, as in Kilivila vivina ‘woman’ > na (Senft 1996: 22), and the masculine gender from the word ‘man’, as in Zande ko ‘man’ > kɔ́ (Claudi 1985: 127–137; Heine and Reh 1984: 223). However, one language may acquire one of its two genders through phonological derivation only. In Somali, for example, gender is marked on nouns by means of tonal morphemes. Masculine forms exhibit a high tone on the penultimate vocalic mora, while feminine forms exhibit a high tone on the final vocal mora, e.g., ínan ‘boy’ and inán ‘girl’ (Saeed 1987: 21).

At first glance, demonstratives could be taken to belong to the type that gender belongs to, but demonstratives and gender show rather different crosslinguistic distributions. Only a limited number of languages have markers for gender, while all languages have demonstratives. In addition, feminine and masculine genders often mirror concrete categories in reality (i.e., sex), while demonstratives do not do so. Consequently, unlike gender markers, proximal and distal demonstratives are unlikely to develop from two independent lexical sources. It is unlikely, for instance, that each of the proximal and distal demonstratives has its own independent source, resulting from separate processes of grammaticalization. The Chinese case shows that the classifiers first developed into proximal demonstratives, and then provided the basis for the emergence of the corresponding distal demonstratives via a rigid phonological rule.

Having examined a sample of 26 languages, Woodworth (1991) concludes that crosslinguistically, there is an element of sound symbolism distinguishing proximal and distal demonstratives: the proximal category tends to use the high front vowel [i], while the distal category favors the low back vowel [a]. Following Woodworth, Traunmüller (1996) investigated a wider range of languages and found that 71% of languages fall into the pattern shown here, as illustrated in Table 1.

Phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives.

| Languages | Proximal | Distal | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | this | that | Singular |

| French | celui-ci | celui-là | Singular, masculine |

| Guugu Yimithirr | yii | nhaa | Pronoun |

| Ambulas | kéni | wani | Determiner |

| Lezgian | i | a | Root |

| Vietnamese | đây | đãy | Adverbial |

Traunmüller correctly notes that if there is any sound symbolism in proximal and distal demonstratives, the relationship between sound and meaning would have to be rather abstract since there are no sounds to imitate in the first place. As we will see in the subsequent section, among the vowels, [a] has the highest degree of sonority and [i] has the lowest degree. This article will demonstrate that the sonority of sounds is a key factor in the derivational process from proximal to distal demonstratives in Chinese. There are hundreds of phonological forms for each of the demonstratives, but they originated from two major lexical sources. These numerous phonological forms are generated by a phonological principle. In Standard Chinese, for instance, it is possible that the distal demonstrative nà [na51][3] is phonologically derived from the proximal demonstrative zhè [tʂɤ51], and the latter was grammaticalized from a general classifier. The focus of the present study is on the phonological derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives of this type.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces some background on demonstratives as a basis for the analysis presented in the later sections. Section 3 describes the phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives in Chinese. Section 4 identifies the phonological principle governing the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives. Section 5 addresses the iconicity between acoustic property and distance. Section 6 contains the conclusions.

2 Some background on demonstratives

This section provides some background for an understanding of the present analysis, including (a) the coverage of the database used, and (b) the lexical sources of demonstratives. According to the relevant the literature, the sources of demonstratives remain unknown, which has led some researchers to claim that demonstratives, a deictic category, belong to the basic vocabulary of every language (Traugott 1982) and thus cannot be traced back to lexical sources (Bühler 1934; Ehlich 1979; Peirce 1955). As mentioned previously, Diessel (1999) even argues that demonstratives might present a second source domain from which grammatical markers may emerge, in addition to lexical items. If this were true, it would undermine one of the central assumptions of grammaticalization theory, i.e. that all grammatical morphemes are ultimately derived from lexical sources. Addressing the grammaticalization process from classifiers to demonstratives is beyond the scope of this study; here, I simply point out what the lexical sources for demonstratives are.

2.1 The database for the present analysis

It is difficult to determine how many dialects Chinese has, because they are remarkably different in terms of phonology, lexicon, and grammar. Even within a dialect family, such as the Wu dialect, people from different areas often cannot communicate using their own dialects. Consequently, there are different views about the divisions of Chinese dialects (Li 2001: 29).[4] For the purpose of the present study, I adopt the so-called eight major dialects as follows:

the Northern dialect,[5] the Jin dialect, the Xiang dialect, the Gan dialect, the Wu dialect, the Min dialect,[6] the Hakka dialect, and the Yue dialect[7]

I reserve the term ‘dialect’ for each of the eight dialectal families and use ‘subdialect’ for smaller dialectal areas.[8] In reality, the Chinese language comprises more than 1000 subdialects with remarkable differences in terms of phonology, lexicon, and grammar. This article does not make any further differentiations among them and simply uses the term ‘subdialect’ for them.

To guarantee the accuracy and complete coverage of the present study, I have established a database on the basis of the following investigations.

Cao (2008). A well-balanced investigation of all eight dialects, covering 930 subdialects.

Huang (1996). A collection of papers and monographs, covering 37 subdialects of the eight dialects.

Wu (2000). An investigation of 53 subdialects spoken in Hunan Province, mainly belonging to the Xiang dialect but including the Hakka dialect and the Northern dialect as well.

Qiao (2000). An investigation of 21 subdialects of the Jin dialect.

Beida (1995).[9] An investigation of 20 representative subdialects of all eight dialects.

Li (2001) and Yuan (2001). Two general surveys of Chinese dialects, covering all eight dialects.

The present analysis is based on the demonstratives of more than 1000 subdialects. Although there is some overlap between the works mentioned above, the details of their descriptions vary greatly, and hence, they are all valuable for my study. Cao (2008) and Beida (1995) are dictionaries that provide only partial forms of demonstratives.

2.2 Lexical sources for chinese demonstratives and their distributions in dialects

A replacement of systems of demonstratives took place in late Medieval Chinese, used from the seventh century to the tenth century. This period gave birth to all the demonstratives that are still used in Contemporary Chinese, that is, zhè, gè and dǐ.[10] The origin of these demonstratives has long been debated in the field of Chinese linguistics, especially the origins of the proximal and distal demonstratives zhè and nà[11] (for details, see Jiang and Cao 2005; Lü 1985; Ohta 1987; Wang 1989). Here, I mention only the most convincing analyses without going into any detail. Jiang (1999) postulates that the demonstrative dǐ originated from a locative word meaning ‘bottom’; I would like to leave this issue open. Zhang (2001) employs solid phonological evidence to argue that the demonstrative zhè in the Northern dialects and gè in many southern dialects originated from two general classifiers in Medieval Chinese. It is less debatable that the demonstrative gè was grammaticalized from its classifier usage because the two words have the same phonological form in many dialects (for details, see Lin 2018; Qian 1997, 2014), but it is problematic to claim that the demonstrative zhè was also derived from the classifier zhī, because the two phonological forms are different in Standard Chinese. However, this issue is successfully resolved by Zhang (2001), who provides the following two pieces of phonological evidence.

In Qie Yun (edited in 601 AD, a phonological dictionary) and Piao Tong Shi Yan Jie (edited in 1515 AD, a textbook to teach Koreans Chinese) the demonstrative zhè and the classifier zhī have exactly the same phonological form.

In at least nine present-day subdialects, the demonstrative zhè and the classifier zhī have the same phonological form. For instance, in the Fuqing subdialect (belonging to the southern Min dialect), both are realized as tsia 21 .[12]

According to Cao (2008), 131 subdialects have the same phonological forms for the proximal demonstrative zhè and the general classifier zhī. The classifier gè was grammaticalized from the noun ‘bamboo’ and the classifier zhī was grammaticalized from the noun ‘bird’ in Medieval Chinese, both of which were among the few earliest classifiers (Wang 1989: 18–41). The earliest examples of the demonstratives gè, zhè (zhī), and dǐ are illustrated in the following examples (Lü 1985: 183–245).

| Gè | rén | huì | dǐ?[13] |

| CL | person | avoid-as-taboo | what |

| ‘What does this person avoid as a taboo?’ | |||

| (Bei Qi Shu, the 7th century) | |||

| Zhī | yán | zhī-le | jìn | bēishāng. |

| CL/this | word | know-PFV | all | sad |

| ‘They all understood these words and became sad.’ | ||||

| (Dun Huang Bian Wen, the 8th century) | ||||

| Zhú-lí | máo-shě, | dǐ | shì | cáng | chūn | chù. |

| Bamboo-fence t | hatched-cottage, | this | be | restore | Spring | place |

| ‘The bamboo fences and thatched cottages, these are the places to restore the Spring.’ | ||||||

| (Mo Shan Xi Ci, the 10th century) | ||||||

Due to diachronic change and cross-dialectal variations, every demonstrative above has contemporary reflexes with a variety of phonological forms. The consonants in the onsets are the most important clues indicating demonstratives with the same origin. Table 2 shows the diachronic changes and cross-dialectal variations of the three demonstratives with different origins.

The diachronic changes and dialectal variations of three demonstratives.

| Times/dialects | Variations of zhī (zhè) | Variations of gè | Variations of dǐ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval Chinese | tɕǐɛk | kɑ | tiei |

| Modern Chinese | tʂi | kɔ | ti |

| Contemporary Chinese | tʂi | kɤ | ti |

| Wu dialect | tsɤh | kəu | ti |

| Xiang dialect | tsɪ | kɑ | ti |

| Gan dialect | tsak | ko | ti |

| Hakka dialect | tsak | kɛ | ti |

| Cantonese | tʃɛk | kɔ | tɐi |

| Eastern Min | tsieh | kɔ | ti |

| Southern Min | tsik | ko | te |

-

The reconstruction of the phonological forms is based on Li and Zhou (1999). The tone values of the demonstratives are not provided when irrelevant to the analysis.

The onsets of these three demonstratives are [k], [tʂ] or [t], and their dialectal variations are listed as follows:

If the onset consonants of the demonstratives are [tʂ], [ts], [tɕ] or [tʃ], they originated from the general classifier zhī.

If the onset consonants of the demonstratives are either [k] or [ɡ], they originated from the general classifier gè.

If the onset consonants of the demonstratives are either [t] or [d], they originated from the locative word dǐ.

As for the 930 subdialects in Cao (2008), the distribution of the three demonstratives with different origins is shown in Table 3.

The dialect distribution of the three demonstratives.

| Originated from zhī | Originated from gè | Originated from dǐ | Unidentified sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| 418 subdialects | 273 subdialects | 60 dialects | 179 |

-

aThe proximal demonstratives of this group of dialects may originate from the three demonstratives, but due to diachronic changes, it is difficult to identify the exact historical developments.

The distinction between the investigated subdialects of the southern dialects, such as the Wu dialect and the Xiang dialect, is much more fine-grained than in the Northern dialects, probably because of different complexities in the relationship between them. In the other 179 subdialects, most of the phonological forms are derived via the same principle, as I will discuss in the subsequent sections.

3 Phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives

A vast body of empirical evidence suggests that there must be some kind of phonological derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives. Unlike other grammatical markers, the phonological forms of demonstratives in Chinese dialects are highly variable, and many of them have two or more forms which show clear phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives. The correlations fall into the following five types:

Type I. The same phonological forms for proximal and distal demonstratives are found. Subdialects of this type are rare, and only the Suzhou subdialect is reported to be of this type in the literature. In the Suzhou subdialect, both proximal and distal demonstratives share exactly the same form, including the onset, nucleus, coda, and tone. Yuan (2001: 97) indicates that gɤʔ 23 in this subdialect is a neutral demonstrative, and that kɛ 44 can be either a proximal or a distal demonstrative.[14] In other cases, however, a glide [u] is added to the distal demonstrative, producing the form [kuɛ]. This case shows that the proximal and distal demonstratives share a root and are later differentiated phonologically.

Type II. Within a subdialect, the proximal and distal demonstratives contain the same sound segments (syllabic form) but are differentiated by tones. Hakka is of this type. The proximal demonstrative is ke 31 , and the distal demonstrative is ke 52 (Yuan 2001: 171). As in the Suzhou subdialect the proximal and distal demonstratives likely originate only from a single source and came to be differentiated by tones later at a later time.

Type III. The rhymes and tones are identical but the consonants at the onset positions are different, distinguishing proximal from distal demonstratives. According to Yuan (2001: 268), the southern Min dialect has seven phonological forms for each proximal and distal demonstrative that either express different meanings or occur in different contexts as independent pronouns or locatives or with ‘Dem + CL’ classifiers, plurals, or temporals. With the rhyme and the tones held constant, [ts] in the onset position indicates a proximal demonstrative, and [h] in the onset position indicates a distal demonstrative, as shown in Table 4. Yuan (2001: 284) claims that the Min dialect actually employs an inflectional strategy to distinguish proximal from distal demonstratives.

Type IV. In Standard Chinese, including Pekingese and the Northern dialect, the proximal and distal demonstratives have different onsets and rhymes, sharing only the same tone, cf. Table 5.

Type V. In some subdialects, the proximal and distal demonstratives share no phonological commonality, differing in the onset, nucleus, coda, and tone. The two subdialects shown in Table 6, Hanshou and Lixian, belong to the Xiang dialect.

The proximal and distal demonstratives in the southern Min dialect.

| Dialect | Proximal | Distal | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Min dialect | tsi 51 | hi 51 | Independent use |

| tse 51 | he 51 | Independent use | |

| tsit 32 | hit 32 | Preceding classifier e 34 | |

| tsia 24 | hia 24 | Locative | |

| tsia 51 | hia 51 | Preceding plural e 34 | |

| tsit 32 | hit 32 | Preceding temporal tsun 33 |

The proximal and distal demonstratives in Standard Chinese.

| Dialect | Proximal | Distal | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Chinese | tʂɤ 51 | na 51 | Pronoun |

| tʂei 51 | na 51 | Fusion with a classifier |

The proximal and distal demonstratives in Hanshou and Lixian (Wu 2000).

| Dialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Hanshou | tiɛ 24 | no 55 |

| Lixian | tiɛ 13 | la 33 |

For the first three types listed above, we can see that the phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives are so strong that they can be taken to have originated from the same sources, having been differentiated by a certain phonological rule (where they differ). As we will see in subsequent sections, even the last two types of proximal and distal demonstratives are derived from a phonological principle. Superficially, the overall picture of cross-dialectal demonstratives in Chinese is extremely complicated. In terms of phonological forms, there are at least 76 proximal demonstratives and 97 distal demonstratives, according to Cao (2008). Moreover, within a single subdialect, a demonstrative, either proximal or distal, can have as many as six different phonological forms,[15] a phenomenon that has not been observed in any other grammatical category in Chinese. In what follows I will demonstrate that all these phenomena are related to a phonological principle determining the relationship between contrastive demonstratives, and are highly uniform and regular from this perspective.

4 Phonological principle for the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives

This section is the core of the present analysis, addressing the following issues:

the asymmetry between proximal and distal demonstratives (Section 4.1),

phonological forms of twin-syllables and cognate words in Chinese (Section 4.2),

the phonological rule of the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives (Section 4.3),

the sonorous asymmetry between the segments of proximal and distal demonstratives (Section 4.4),

the reversal of the derivational process between proximal and distal demonstratives (Section 4.5),

the glottals at the onset of the distal demonstrative (Section 4.6),

the different specification between onset and nucleus (Section 4.7), and

the cliticization of demonstratives (Section 4.8).

4.1 The Asymmetry between proximal and distal demonstratives

Within a grammatical opposition such as the one between singular vs. plural, as mentioned above, the singular is more basic and remains unmarked, while the plural is less basic and marked (Corbett 2004: 17). For demonstratives, the proximal ones are more basic and unmarked (default), and the distal ones are derivative and marked (Ariel 1990). This distinction is confirmed by observations concerning human cognition and the frequency of occurrence. Proximal demonstratives indicate a smaller distance between the speaker and the referent, while distal demonstratives indicate a farther distance. The orientation of human cognition is typically from the decitic center to a farther location. Langacker (1991: 242–246) relates the proximal-distal contrast in demonstratives to the present—past distinction in the tense system, where proximal corresponds to present and distal correspond to past. Likewise, Ariel (1990) argues that proximal demonstratives are less marked than distal demonstratives. These assumptions are supported by the different frequencies of the proximal zhè and distal nà throughout the history of Chinese, cf. Table 7.

The frequency of the proximal zhè and the distal nà in vernacular texts.

| Texts | Eras | Sizea | Proximal zhè | Distal nà |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhuzi Yulei | 12th century | 1,975,900 | 6381 | 2,926 |

| Yuan Zaju | 13th century | 365,700 | 1361 | 1,015 |

| Hong Lou Meng | 18th century | 860,700 | 7748 | 4,876 |

| Dangdai Xiangsheng | contemporary | 478,300 | 6919 | 3,019 |

-

aThe size of the texts refers to the number of Chinese characters.

Clearly, the frequency of the proximal zhè is always higher than that of the distal nà, which shows that the former is more basic than the latter.

There are some exceptions to the derivational direction between proximal and distal demonstratives. In 33 of the 930 subdialects mentioned by Cao (2008) (accounting for 3.5% of the total), the demonstratives that were grammaticalized from the classifier gè were first realized as distal demonstratives, and then gave rise to the corresponding proximal demonstratives through a phonological principle, as illustrated in Table 8. This irregular realization causes interesting derivations, which will be discussed in the subsequent sections.

Distal demonstratives from the classifier gè in subdialects.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou | li/lia | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Guangning | ni/ne | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Yongxin | kə/ki | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Yunan | i/ia | kɔ/ko/ku |

Some subdialects even have more than one proximal demonstrative, each originating from a different source. For instance, the Shanghai subdialect has two proximal demonstratives, diəʔ 12 and geʔ 12 ; the former is the traditional demonstrative, and the latter is the newly emerging one (Huang 1996: 487). Obviously, the proximal demonstrative diəʔ 12 was grammaticalized from the locative word dǐ, and the proximal geʔ 12 was grammaticalized from the classifier gè.

Thus far, I have mainly discussed proximal demonstratives without mentioning the corresponding distal demonstratives. As mentioned previously, it has been convincingly argued that two general classifiers plus one possible locative word first developed into proximal demonstratives, but no sources for the distal demonstratives have been found.[16] The main focus of this article is on where the corresponding distal demonstratives come from and how they emerged. This question is addressed in the following section.

4.2 Phonological forms of twin-syllables and cognate words in chinese

Chinese is a tonal language, and tonal contours function to distinguish meanings. Additionally, Chinese is basically a monosyllabic language, and approximately 90 percent of its morphemes, defined as minimal pairings of meaning and form (usually [smaller than] words), are monosyllabic (Lü 1963). In all dialects, basic demonstratives in Chinese are monosyllabic, regardless of whether they are proximal or distal. Chinese does not allow any consonant clusters, and hence, only a single consonant can occur at the onset or coda position. The glides, [j], [w], and [y] may occur in the initial position of the rhyme. The maximal syllable of Chinese can be represented as follows[17]:

When the onset position is empty, the glides (or semivowels) are raised to occupy this position. In this case, the glides may function to distinguish medial from distal demonstratives, as we will see in the next section.

In terms of auditory phonetics, the concept of ‘sonority’, which is central to this analysis, can be defined from two closely related perspectives: energy and openness. First, it refers to the carrying power of a sound; the more sonorous a sound is, the more articulatory effort is required to produce it (Clark and Yallop 1992: 61). Second, it refers to relative openness of the vocal tract, which directly determines the relative loudness of a sound. The wider open the mouth is, the more sonorous the sound is. For example, among vowels, the low vowels exhibit the highest degree of sonority and the high vowels have the lowest degree of sonority (Zsiga 2013: 333–334). Syllables are structured in accordance with certain principles relating to the sonority of sounds. It has been known for over a century that the construction of syllables is guided by the following principle (Kenstowicz 1994: 254):

Sonority Sequencing Principle: onsets must rise in sonority toward the nucleus and codas must fall in sonority from the nucleus.

Interestingly, crosslinguistic regularity in constructing a syllable is widely found in the phonological derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives in many Chinese dialects. While the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP) works in a linear fashion when constructing a syllable across languages, it behaves in a non-linear fashion in the derivation of distal demonstratives from proximal demonstratives in Chinese. Overall, the sonority of vowels is higher than that of consonants, but vowels differ in sonority, too. According to Kiparsky (1979) and Kenstowizc (1994: 254–255), the vowels are ordered in terms of sonority as follows:

| Low vowels [a, ɑ, ɒ, æ] > Middle vowels [ɛ, ɔ, e, ɤ, o] > |

| High vowels [ɯ, u, i, ɪ] > Schwa [ǝ] |

Notice that among all vowels, schwa [ǝ] has the lowest sonority and the low vowel [a] has the highest sonority; the other vowels are located in between these extremes. The sonority scales of sounds at the onset positions are as follows (Selkirk 1984: 112):

| Glides [j, w] > Liquids [l] > Nasals [m, n, ŋ] > Fricatives [s, f] |

| > Voiced affricatives [v] > Affricatives [tʂ, ts] > stops [t, p] |

When no consonant occurs in the onset position, the high vowels [i] and [u], originally the initials of the rhyme, automatically take the onset position and are pronounced as glides (semivowels) [j] and [w].

The SSP operates within syllables in all languages. For example, English has monosyllabic words such as plain [plein] and plant [plænt], but the syllables cannot be structured as plani or plnat. In Chinese, however, this phonological principle is not only found inside a syllable but also within a group of semantically related words in a cross-syllabic fashion. As mentioned above, Chinese is basically a monosyllabic language, which means that a syllable usually stands for a meaningful morpheme that corresponds to a Chinese character. Due to a historical disyllabification tendency, nearly 80% of words in contemporary Chinese are dissyllabic, and their phonological forms are determined by the two meaningful morphemes. For instance, in ɕiao51 ʂi55 (teach + master) ‘teacher’, there is no phonological constraint between the two syllables. Many nouns become disyllabic through the addition of nominal suffixes such as -zi, -er or -tou, whose syllables are also independent. However, there is always a portion of disyllabic words whose two syllables are phonologically constrained. In these cases, neither of the two syllables conveys any semantic content, and they cannot be separated and used independently. These words are called ‘twin-syllable’ words, as illustrated in (8) (Shi 1995).

| Nouns: | hu 55 tiɛ 55 ‘butterfly’ | ha 35 ma ‘frog’ | tʂaŋ 55 laŋ 35 ‘cockroach’ |

| Verbs: | ku 213 tiao ‘tinker’ | pa 55 la ‘remove’ | hu 55 you ‘trick’ |

| Adjectives: | p h iao 51 liaŋ ‘pretty’ | ɕi55 liŋ ‘clever’ | mɘŋ 35 loŋ 35 ‘dim’ |

| Onomatopoeias: | p h u 55 toŋ 55 ‘pit-a-pat’ | p h iŋ 55 p h aŋ 55 ‘rattle’ | huŋ 55 loŋ 55 ‘rumble’ |

Between the two syllables of a twin-syllable word, even the tones are closely related to each other. For instance, nearly 100% of Chinese onomatopoeias have a high tone, e.g., p h u 55 toŋ 55 , p h iŋ 55 p h aŋ 55 , and huŋ 55 loŋ 55 .

On the basis of the sonority scales of sounds and the SSP, we can immediately recognize that the construction of twin-syllables in Chinese obeys a principle similar to what is found cross-linguistically within a single syllable. In the following formula, S stands for syllable, O stands for onset, N stands for nucleus, and C stands for coda; the subscripts indicate whether the segments in question belong to the first syllable or the second syllable. The function f s is defined as returning the sonority value of a segment.

| f s (S2) ≥ f s (S1); | f s (O2) ≥ f s (O1); | f s (N2) ≥ f s (N1); | f s (C2) ≥ f s (C1) |

For example, according to the definition of sonority degree, in the onomatopoeia huŋ 55 loŋ 55 , the onset of the second syllable [l] is more sonorous than that of the first syllable [h], the nucleus of the second syllable [o] is more sonorous than that of the first syllable [u]. The codas of the two syllables are equally sonorous.

Before using the sonority principle to explain the derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives, it should be emphasized that there is a language-specific way of coining new words in Chinese. Phonemes within a syllable are linearly adjacent to each other, so it is not surprising that there are certain phonological constraints between them. However, proximal and distal demonstratives are independent of each other and rarely occur adjacently. How can they show a phonological correlation? The answer lies in the way in which speakers of Chinese create phonological forms for new words. In his pioneering study, Wang (1978[2000]) discovered that a pair of antonyms or a group of semantically related words can be assigned a new phonological form by changing the tones, consonants at onset, or vowels at the nucleus of certain etymological roots. There are thousands of words whose phonological forms have been created in this way (for details, see Wang 1997). Some of them are illustrated in (10).

| Tone shifts, e.g., mai 213 ‘buy’, mai 51 ‘sell’. |

| Consonant and tone shifts, e.g., tʂaŋ 35 ‘long’, tʂaŋ 213 ‘grow’. |

| Nucleus and tone shifts, e.g., pei55 ‘low-rank’, pi51 ‘servant girl’. |

| Consonant, nucleus, and tone shifts, e.g., ʂi 35 ‘eat’, sɪ 51 ‘feed’. |

While the English verbs buy and sell bear no phonological similarity, their corresponding verbs in Chinese share the same syllable and are differentiated by tone only. The special process of creating phonological forms in Chinese mentioned above is crucial for understanding the phonological derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives.

In short, phonological correlations and constraints work in a cross-syllabic fashion in Chinese, including in the creation of phonological formations for words that are semantically related. Since proximal and distal demonstratives are deictically contrastive, the phonological correlations between them are perfectly natural in Chinese.

4.3 Phonological rule for the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives

The phonological rule governing the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives is similar to the SSP for constructing syllables. Proximal and distal demonstratives are semantically contrastive and thus can be viewed as pairs of antonyms or semantically related words. As noted previously, classifiers and locative words were the first elements to be grammaticalized into proximal demonstratives.[18] Instead of recruiting another lexical source for their corresponding distal demonstrative, almost all dialects employ a phonological rule to derive the corresponding distal demonstratives. Specifically, the sonority values of sounds at the onset, nucleus, and coda are remarkably contrastive between the phonological forms of proximal and distal demonstratives. In the following formulas, f s is defined as a function returning a degree of sonority; Od, Nd and Cd stand for the onset, nucleus and coda of distal demonstratives; and Op, Np and Cp stand for the onset, nucleus and coda of proximal demonstratives.

| f s (Od) ≥ f s (Op) |

| f s (Nd) ≥ f s (Np) |

| f s (Cd) ≥ f s (Cp) |

These three formulas do not operate in the same fashion in differentiating proximal and distal demonstratives in different subdialects. Another phonological principle for constructing a syllable, namely, the Sonority Dispersion Principle (SDP), states that every language prefers to maximize the sonority slope from onset to nucleus and to minimize this value from nucleus to coda (Clements 1990: 291). Similarly, the sonority slopes between the two onsets of proximal and distal demonstratives tend to be maximized and are rarely equal to each other; the sonority slopes between the two nuclei and codas of the two demonstratives tend to be minimized and are often equal to each other, a point that I will discuss in Section 4.4.

According to the database consisting of more than 1000 subdialects, 97% of subdialects can be explained by means of formula (11). First, let us use the demonstratives of Standard Chinese (Mandarin) to test the principle.

| Standard Chinese | |

| proximal | distal |

| tʂɤ 51 | na 51 |

According to the sonority scale, f s ([n]) ≥ f s ([tʂ]) and f s ([ɑ]) ≥ f s ([ɤ]), and both demonstratives share the falling tone. As mentioned previously, this pair of demonstratives in Standard Chinese emerged in late Medieval Chinese. In the literature, the source of the distal demonstrative nà remains unknown, though there are some speculations about its origin. For instance, Ohta (1987: 118) and Wang (1989: 65) speculate that nà might have originated from the two demonstratives of Archaic Chinese, ruò or ěr. This view is problematic for three reasons. First, these two demonstratives ceased to be used around the first century, but nà did not arise until the eighth century. When nà emerged, the dominating distal demonstrative was bǐ, whose corresponding proximal demonstrative was cǐ. Second, their phonological forms were remarkably different, as shown in shown in Table 9.[19]

The historical phonological forms of the three distal demonstratives.

| Middle Chinese | Modern Chinese | Contemporary Chinese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ruò | ɽǐak 4 | ɽiɔ 4 | ʐuo 4 |

| ěr | ɽǐe 2 | ɽï 3 | ɚ 3 |

| nà | na 3 | na 4 | na 4 |

-

The single numbers on the right top of syllables indicate the tonal types rather than tonal contours.

Clearly, it is unlikely that the two archaic demonstratives developed into nà according to the evolution of the phonological system of Chinese.

Third, and more importantly, the functions of the demonstratives differ remarkably. For instance, ruò and ér always behaved like adjectival demonstratives; in other words, they could never be used without a nominal head. By contrast, the syntactic use of nà is entirely parallel to that of its corresponding proximal zhè. For instance, both demonstratives are often combined with a classifier to substitute an entire NP, omitting the noun heads. Additionally, both zhè and nà can be used as genitive markers, preceded by a possessor, as illustrated in (13) and (14).

| Nǐ | zhīdào | wǒ | zhè | bìng. |

| you | know | I | this | disease |

| ‘You know my disease.’ | ||||

| (Hong Lou Meng, Chapter 62, the 18th century) | ||||

| Xīhǎn | chī | nǐ | nà | gāo? |

| like | eat | you | that | cake |

| ‘Who likes to eat your cake?’ | ||||

| (Hong Lou Meng, Chapter 60, the 18th century) | ||||

Clearly, the distal nà could not have developed out of any other distal demonstratives in Archaic Chinese. The present analysis suggests that this distal demonstrative might be derived from the proximal demonstrative zhè via a phonological rule. There may be other possibilities of the emergence of the distal demonstratives, however, so I would leave this issue open for future research.

The phonological forms of demonstratives in Standard Chinese are based on Pekingese.[20] Indeed, there are many phonological variants of the distal demonstratives in the Northern dialects that are used by approximately 70% of the population. The proximal demonstratives that originated from the classifier zhī are realized as [tʂɤ], [tsɤ], [tʂi], [tsɪ], [tʂei], [ʦei], [ʦit], and [tɕiaʔ] in different subdialects. For the sake of simplicity, Table 10 shows only the distal demonstratives whose corresponding proximal demonstratives are [tʂɤ].

The onsets of distal demonstratives of the proximal demonstrative [tʂɤ].

| Onsets of distal demonstratives | Number of subdialects | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal | ||

| [n] | 148 | Libo | tʂɤ/tsɤ | na/ne/nɤ |

| [l] | 31 | Jishou | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | la/le |

| [m] | 3 | Yingcheng | tʂɤ/tsɤ | mo/mə/mei |

| [u] | 7 | Jiujiang | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | ua/uei |

| [ŋ] | 6 | Yuexia | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | n/ŋ |

| [h]b | 5 | Lufeng | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | hi/hia/hiɔ |

| [k] | 3 | Jingzhou | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | kɔ/ko/ku |

| [a] | 2 | Huaning | tʂɤ/tsɤ | a/e/ei |

-

aIts distal n/ŋ results from cliticization, a point that I will return to in the subsequent section. bIn Cao (2008), this [h] is transcribed as [x], but in Yuan (2001) it is transcribed as [h].

There are 21 different phonological forms of the distal demonstratives that correspond to the proximal demonstrative [tʂɤ]. Even within a given subdialect, there are typically two or more phonological forms for distal demonstratives. These facts show that it is likely that these distal demonstratives did not originate from any independent lexical sources. Of the 205 subdialects summarized in Table 10, only five seem to be exceptions to the phonological principle (the onset consonants are [k] and zero). In other words, with respect to the emergence of their distal demonstratives, the phonological rule can account for 97% of the subdialects. In phonological theory, [k] is regarded as the least sonorous plosive and has a lower degree of sonority than the affricative [tʂ]. There are possible explanations for this. The phonological properties of the distal and proximal demonstratives suggest that this group of subdialects might have developed the classifier gè into their distal demonstratives, and the classifier zhī into their proximal demonstratives. Indeed, some subdialects obtained their distal demonstratives from the classifier gè, which in turn caused a reversal of the derivation process between the two demonstratives. The Huanning subdialect chose the low vowel [a] with the highest sonority as its distal demonstrative, which shows that it is not a real exception because there is still a remarkable increase in the sonority of the nucleus.

4.4 The sonority asymmetry between the segments of proximal and distal demonstratives

According to the phonological principle in (11), the degrees of sonority of the onsets and nuclei of distal demonstratives must be either higher than or equal to the corresponding segments of proximal demonstratives.[21] However, this requirement varies from one segment to another, as stated in the following.

For the segments at the onset, the sonority of distal demonstratives is usually higher than but rarely equal to that of proximal demonstratives.

For the segments at the nucleus or coda, it is equally possible that the sonority of distal demonstratives is either higher than or equal to that of proximal demonstratives. This pattern differs across dialects.

The above asymmetry is manifested by the SDP, which says that a syllable tends to maximize the sonority slope from onset to nucleus, and to minimize the slope from nucleus to coda (Clements 1990: 291), as mentioned above. This principle can be revised to maximize the sonority slope from the onset of the proximal demonstratives to that of the distal demonstratives, and to minimize this value from the nucleus/coda of proximal demonstratives to those of distal demonstratives.

Within the 320 subdialects of the Northern dialect,[22] 311 subdialects (97%) have increased the sonority values from the onsets of proximal demonstratives to those of distal demonstratives. Since the proximal demonstratives mostly originated from the classifier zhī, the onsets of these subdialects are [tʂ] or [ts]. The onsets of the distal demonstratives are mostly [n] and sometimes [m], [l] or [w], see Table 11.

Patterns of the two onsets with sonority increase.

| Patterns | Proximal | Distal | Subdialects, Provinces |

|---|---|---|---|

| tʂ → n | tʂɤ/tʂei | na/nei | Pekingese |

| tʂ/ts → l | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | la/le | Yanzhou, Shandong |

| tʂ/ts → w | tʂi/ʦɪ | wa/wei | Longde, Ningxia |

| tʂ/ts → m | tʂɤ/tsɤ | mo/mə/mei | Yingcheng, Hubei |

For the nine subdialects exhibiting equal degrees of sonority in the two onsets, the consonants of the onsets of their proximal demonstratives are either nasals or liquids, which have the highest sonority values among all consonants, cf. Table 12. Thus, it is impossible to increase the sonority from the first onset to the second.

Patterns of the two onsets with equal sonority.

| Patterns | Proximal | Distal | Subdialects, Provinces |

|---|---|---|---|

| n → n | ni/ne | na/ne/nɤ | Chongqing |

| l → l | li/lia | la/le | Enshi, Hubei |

| k → k | kə/ki | kuɛ | Baoji, Shanxi |

The Baoji subdialect deserves special attention. It is the only subdialect in which the onset of the proximal demonstratives is [k]. This indicates that it originated from the classifier gè, which is typically found in the Southern dialects, making this the only exception in the Northern dialect.

Within this group of 320 subdialects, 59 exhibit a sonority increase from the first nucleus to the second, as shown in Table 13. The vowels of the first nucleus are either [i] or its variant [ɪ].

Patterns of the two nuclei with a sonority increase.

| Patterns | Proximal | Distal | Subdialects, Provinces |

|---|---|---|---|

| High vowels → middle/low vowels | tʂi/ʦɪ | na/ne/nɤ | Wenshan, Yunnan |

| tʂi/ʦɪ | la/le | Anlong, Guizhou | |

| tʂi/ʦɪ | a/e/ei | Dafanga, Huizhou |

-

aIn the Dafang subdialect, the onset of the proximal demonstrative is empty due to cliticization, which I will discuss later.

In the remaining 261 subdialects, the distal demonstratives always have an alternative form with the same vowel as that of the corresponding proximal demonstratives. This means that the sonority scales of the two nuclei can be equal, cf. Table 14. Standard Chinese has two pairs of phonological forms for its proximal and distal demonstratives: [tʂɤ]/[na] and [tʂei]/[nei]. The first pair shows a sonority increase between the two nuclei, but the second pair exhibits equal sonority values in the two nuclei.

Patterns of the two nuclei with equal sonority.

| Patterns | Proximal | Distal | Subdialects, Provinces |

|---|---|---|---|

| əʔ → əʔ | tʂəʔ/ʦeʔ | naʔ/nəʔ | Taipusi, Neimenggu |

| ei → ei | tʂei/ʦei | nai/nei | Haerbin, Heilongjiang |

| ɤ → ɤ | tʂɤ/ʦɤ | na/ne/nɤ | Yangyuan, Hebei |

| i → i | ʦi/ʦia | ni/niɛ | Wuzhong, Ningxia |

As mentioned in Section 3, in the Min dialect, with the rhymes (i.e., nucleus and coda) remaining the same, the shift between [ts] and [h] refers to the proximal and distal demonstratives, respectively. Similarly, in the Jin dialect, some subdialects can have as many as six phonological forms for each of the proximal and distal demonstratives, and the rhymes remain unchanged; different consonants in the onset thus identify different demonstratives, cf. Table 15.

Demonstratives in the Jin dialect with different onsets and the same rhymes.

| Proximal | Distal | Subdialects |

|---|---|---|

| tʂã 213 tʂəʔ 45 tʂəu 213 tʂəu 53 | nã 213 nəʔ 45 nəu 213 nəu 53 | Shanyin |

| tʂǝʔ 32 tʂar 54 tʂǝu 54 | nǝʔ 32 nar 54 nǝu 54 | Datong |

| tiᴀ 53 tiɛ 33 ti 11 tiə 11 tə̃r 33 tɐr 33 | niᴀ 53 niɛ 33 ni 11 niə 11 nə̃r 33 nɐr 33 | Jincheng |

In short, in distinguishing proximal from distal demonstratives, the sonority scales are maximized from the first onset to the second onset and minimized from the first nucleus to the second nucleus.

4.5 The reversal of the derivational process between proximal and distal demonstratives

Approximately 30 of the 930 subdialects documented in Cao (2008) (accounting for 3% of the total) first developed the classifiers into distal demonstratives and then derived the corresponding proximal demonstratives by means of the same phonological rule. In other words, the derivational process proceeded in reverse, from distal to proximal demonstratives, showing some very interesting properties. The reverse derivation is mainly found in Cantonese (the Yue dialect), cf. Table 16. A successful explanation for this phenomenon will lend further support to the hypothesis that there is a phonological rule guiding the derivation between distal and proximal demonstratives.

The classifier gè realized as distal demonstratives in the Yue dialect.

| Proximal | Distal | Subdialects |

|---|---|---|

| ni/ne | kɔ/ko/ku | Hong Kong |

| li/lia | kɔ/ko/ku | Zhongshan |

| li/lia | kai/kei | Boluo |

| ti | keʔ/kəʔ | Liannan |

| tə/tei | kɔ/ko/ku | Fogang |

| i/ia | kɔ/ko/ku | Conghua |

| i/ia | kai/kei | Longmen |

First, let us focus on the consonants at the onsets. The classifier gè has the onset consonant [k], which has the lowest degree of sonority among all sounds. Once it is realized as the distal demonstrative in a particular subdialect, there are only two strategies left to satisfy the formula f s (Od) ≥ f s (Op): (a) Find another plosive consonant for the onset of the proximal demonstrative, e.g., [t] in Liannan and Fogang; in this case, the formula becomes f s (Od) = f s (Op); (b) evacuate the onset of the proximal demonstratives, as in Conghua and Longmen; in this case, the formula becomes f s (Od) > f s (Op).

However, quite a few subdialects, such as those spoken in Hong Kong, Zhongshan and Boluo, violate the formula by reversing the sonority increase from the onset of the distal demonstratives to that of the proximal demonstratives. An appropriate explanation is that these subdialects have different rankings of the rules: the optimal rule is that there must be a sonority increase between the two onsets of proximal and distal demonstratives, regardless of the direction. As a result, nasals and liquids are used as the onsets of proximal demonstratives in Hong Kong, Zhongshan and Boluo.

In the Yue dialect, the phonological form of the classifier gè is [kɔ], with a central vowel as its nucleus. According to the sonority hierarchy, [ɔ] is more sonorous than the high vowels [i] and [ǝ]. Thus, to satisfy the formula f s (Nd) ≥ f s (Np), it is possible to increase the sonority value of the nucleus of a proximal demonstrative to that of a distal demonstrative. All vowels of the proximal demonstratives are either [i] or [ǝ], as shown in Table 16, which satisfies the phonological principle.

The generalization made above can perfectly explain the group of subdialects illustrated in Table 17. The demonstrative gè is realized as both proximal and distal, differentiated by the sonority of the vowels. The nuclei of the proximal demonstratives are either [i] or [ǝ], which are the least sonorous vowels.

Reverse derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives in Cantonese and Hakka.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Dianbai | kə/ki | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Gaozhou | kə/ki | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Lianzhou | kə/ki | koŋ/gã |

| Lianping | kə/ki | kai/kei |

| Meizhou | kə/ki | ka/ke/kə |

Furthermore, in the Xiang family, there are three ways to derive proximal demonstratives where the classifier gè is first realized as a distal demonstrative instead, as shown in Table 18.

Reverse derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives in the Xiang dialect.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Pingjiang | li 35 | ko 35 |

| Yizhang | ti 21 | kai 41 |

| Miluo | i 24 | ko 24 |

| Yanling | i 31 | kai 31 |

First, like the Hong Kong subdialect in the Yue family, the Pingjiang subdialect shows that there must be a sonority increase between the two onsets of proximal and distal demonstratives, regardless of the direction. As a result, the liquid [l] occupies the onset position of the proximal demonstrative. Second, like the Liannan subdialect in the Yue family, the Yizhang subdialect finds another plosive consonant [t] for the onset of its proximal demonstrative; in this case, the formula becomes f s (Od) = f s (Op). Third, like the Conghua subdialect in the Yue family, the Miluo and Yanling subdialects evacuate the onset of proximal demonstratives; in this case, the formula becomes f s (Od) > f s (Op).

In summary, the phonological principle works in reverse when the classifier gè is first realized as a distal demonstrative in those subdialects. Once again, this phenomenon reveals that the derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives is consistently governed by the phonological rule.

4.6 The glottal sounds at the onset of the distal demonstrative

The crosslinguistic distribution of glottal sounds lends further support to the phonological principle proposed in this article, guiding the derivation from proximal to distal demonstratives in Chinese. In the literature, there are two opposite views on the sonority value of glottals. One view is that glottals are highly sonorous (Chomsky and Halle 1968: 301; Levin 1985; Pike 1954). By contrast, other researchers have argued that glottals have the lowest degree of sonority, basically identical to that of obstruents (Heffner 1950; Lass 1976; Lombardi 1999: 3.2; Zec 1988). Clements (1990: 322) claims that glottals behave arbitrarily in terms of their position on the sonority scale, effectively having no sonority value.

Empirical evidence suggests that in sonority distance restrictions, glottals usually behave like highly sonorous elements. For example, Gujarati allows only glides, liquids, and [h] as the second members of onset clusters: [kjal] ‘opinion’, [krupa] ‘kindness’, [kleʃ] ‘fatigue’, and [khǝrǝc] ‘cost’ (Cardona 1965: 31). In contrast, it is rare for [h] to have the same distribution as other fricatives, as is evident, for example, in a comparison of the English words [slɪt] ‘slit’, [flɪt] ‘flit’, and *[hlɪt]. Likewise, in Chinese dialects, the two glottals [ʔ] and [h] behave like nasals and liquids, which are highly sonorous. In the Jin dialect, for instance, only [ʔ], [n], [m], and [ŋ] can occur in the coda position. In the derivation process from proximal to distal demonstratives, the glottal [h] behaves like a nasal or liquid in the Min dialect, as discussed below.

The consonants in the onset position of distal demonstratives are mainly nasals ([n], [m], and [ŋ]) and the liquid [l]. According to Cao (2008), however, 111 subdialects use the uvular [x] as the onset for their distal demonstratives. In this work, no onsets are transcribed as glottal [h]. Both [x] and [h] are fricatives. Distal demonstratives of this type are mainly found in the subdialects of the Min family. However, according to Beida (1995: 557) and Yuan (2001: 97), in the phonological system of the Xiamen subdialect (i.e. the representative area of the Min dialect), only [h] exists, and [x] is absent. Among the 20 representative subdialects in Beida (1995), there are four subdialects with [h] as the onset of the distal demonstrative and only one with [x] as the onset.

As Table 19 shows, [h] is used as the onset of the distal demonstrative more frequently than [x]. In addition, the sound [x] of demonstratives is recorded as [h] in Yuan (2001: 235–283). I therefore believe that the transcriptions of Cao (2008) are inaccurate and that most instances of [x] in the onset are actually instances of the glottal fricative [h]. Consequently, a majority of the 111 subdialects should have [h] onsets in their distal demonstratives. Accordingly, in the Min dialect, [h] has a sonority value comparable to that of a nasal or liquid, which implies an increase in sonority from the onset of the proximal demonstratives to that of the distal demonstratives. This can explain why a shift between [ts] and [h] is used to distinguish proximal from distal demonstratives in the Min dialect, which Yuan (2001) regards as a kind of inflection.

The [h] and [x] onsets of distal demonstratives in Beida (1995).

| Subdialects | Dialectal family | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wenzhou | Wu | ki 213 | he 45 |

| Nanchang | Gan | kɔ 213 | hɛ 213 |

| Xiamen | Min | ʦit 32 | hit 32 |

| Chaozhou | Min | ʦi 53 | hɯ 53 |

| Fuzhou | Min | ʦi 21 | xi 21 |

4.7 The different specifications between onset and nucleus

A remarkable feature of demonstratives is that their phonological forms are variable in almost all Chinese dialects. In Cao (2008), only one of the 930 subdialects has a single form for its proximal and distal demonstratives. The other subdialects have two or more phonological forms for each of their demonstratives. Such variability is not found in any other grammatical morphemes. For instance, the associative marker de, the most frequently used morpheme, has only a single phonological form within specific subdialects, e.g., [tǝ] in Standard Chinese, [kɤʔ] in Suzhou, and [kɔ] in Yangjiang (see Beida 1995 for details).

In Standard Chinese, the proximal demonstrative zhè has two phonological forms, [tʂɤ51] and [tʂei51],[23] and the distal demonstrative also has two corresponding forms, [nɤ51] and [nei51]. The situation in dialects is much more complex. Some subdialects have as many as six different forms for each of their proximal and distal demonstratives. This means that a single subdialect can have more than 10 distinctive forms for its demonstratives, as shown in Table 20 (Qiao 2000: 127).

Phonological variations of demonstratives in subdialects.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Jincheng | tiᴀ 53 | niᴀ 53 |

| tiɛ 33 | niɛ 33 | |

| ti 22 | ni 22 | |

| tiəʔ 22 | niəʔ 22 | |

|

tə̃r

33

tɐr 33 tsɔ 21 |

nə̃r 33 | |

|

nɐr

33

uɔ 21 |

||

| Shouyang | ʦə̃ 21 | uə̃ 21 |

| ʦəʔ 22 | uəʔ 22 | |

| ʦei 21 | uei 21 | |

| æ 22 | æ 22 |

Clearly, the consonants in the onset positions are fixed for proximal and distal demonstratives, but the rhymes are variable. In this case, there is a rigorous correspondence between the rhymes of proximal and distal demonstratives, including medial demonstratives if there are any.

In many other subdialects, the consonants at the onset position are the same, and in these cases, the vowels in the nucleus must be distinctive, distinguishing proximal from distal demonstratives; typically, the sonority increases from the proximal nucleus to the distal nucleus, see Table 21.

Same onsets but different nuclei in distinguishing proximal from distal pronouns.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Longyan | xi | xɛn |

| xia | xaŋ | |

| xɔ̃ | ||

| Maoming | kə | kɔ |

| ki | ko | |

| ku | ||

| Nanhai | li | lɔ |

| lia | lu | |

| ləu |

If the onsets remain the same, the vowels must be different. In either case, the consonants at the onset position are specified.

4.8 Cliticization of demonstratives

In some dialects, only one phoneme is used to express demonstratives. These phonemes, typically [a], [i], [u], [n], and [ŋ], all have a high degree of sonority, carrying the potential to be syllabic, as shown in Table 22.

Cliticization of demonstratives.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Yunan | a | u/ɔ |

| Heshan | a | a/e/ei |

| Loudi | n | n/ŋ |

| Liuyang | i/ia | kɔ/ko/ku |

| Xinhua | i/ia | n/ŋ |

| Hengyang | kɔ/ko/ku | a/e/ei |

| Chaling | ɤ/ɯ/u | mɛ̃ 52 |

| Wuyishan | i/ia | u/ɔ |

| Jianshui | tʂi/ʦɪ | a/e/ei |

| Huangmei | tə/tei | i/iɛ |

| Yiwu | n | dɔŋ |

| Linyi | tʂuo/tʃou | u/ɔ |

Since the focus of this article is on the phonological derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives, I have not discussed their syntax. The derivation process may be obscured by phonological reduction from cliticization or fusion with other adjacent elements, which is related to syntax. In this section, I will address the phonological reduction of demonstratives and several special cases for which the derivation processes cannot be identified at present.

In many dialects, demonstratives cannot immediately precede a noun and must be connected by a classifier (for details, see Huang 1996). To replace an entire NP, a demonstrative has to combine with a classifier. In addition, demonstratives are often combined with locative words to indicate places or adverbial suffixes to modify a VP. These factors may cause demonstratives to cliticize to, or fuse with, the following elements. Their high frequency of occurrence with classifiers may trigger the fusion of demonstratives with the following classifiers or locatives. Ariel (1990) proposed an Accessibility Marking Scale, a cline showing the tendency toward phonological reduction:

| Distal demonstrative > proximal demonstrative > clitic > zero |

It is cross-linguistically common that pronominal elements cliticize to an element in their environment. Likewise, demonstratives are often phonologically reduced to a single phoneme. For instance, Lezgian has two demonstrative roots, i ‘proximal’ and a ‘distal’, which must be combined with other elements to be used (Haspelmath 1993: 259).

Since they are frequently combined with other elements, demonstratives are subject to cliticization, which in turn causes their phonological reduction. This reduction may occur in the onset or nucleus. In the Liuyang subdialect (Li 2001), for instance, the distal demonstrative n cannot be used alone and must co-occur with the classifier ke, as illustrated in (16):

| N 44 -ke | ʂi 11 | t h ua 44 | lie | tsia 24 -tsi | ke. |

| that-CL | be | he | Gen | sister | PRT |

| ‘That is his sister’s.’ | |||||

| (The Liuyang subdialect, Wu 2000: 32) | |||||

When used as an adverb to modify APs or VPs, the distal demonstratives in Liuyang have two forms – koŋ and n – indicating that the reduced form n should be phonologically reduced from koŋ.

Likewise, in the Jin dialect, the distal demonstrative u is a reduced form and is usually combined with other elements. For instance, u 213 .ɛ in the Yangqu subdialect is a fusion between a distal demonstrative and a classifier. The full form in the Yuanping subdialect, its neighboring subdialect, is uai 54 (Qiao 2000: 126–127).

Of the 24 subdialects of the Jin family (Qiao 2000), six subdialects use [u] or [ɔ] to encode distal demonstratives only, including Pinglu, Wanrong, Linyi, Xiangfen, Huozhou, and Pinyao. Within this dialectal family, many subdialects use u alone as the onset of their distal demonstratives. There is robust evidence that this u is a reduced form, as shown in Table 23.

[u] used as a distal demonstrative in the Jin dialect family.

| Subdialects | The Linfen subdialect | The Yuanping subdialect |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal | tʂei tʂǝŋ tʂaŋ | tʂæɛ tʂi tʂər |

| distal | uei uǝŋ uaŋ | uæɛ u uǝr |

Here, let us focus on the single phoneme [u] in the Yuanping subdialect in Table 23, which constitutes a distal demonstrative. There is a neat correspondence between each form of the proximal and distal demonstratives in the two subdialects. With the same rhymes, the shift between [tʂ] and [u] at the onset distinguishes proximal from distal demonstratives. Apparently, the distal [u] in the Yuanping subdialect is actually a reduction of [ui].

Of the 93 subdialects of the Xiang family, 13 use one of the following phonemes to encode their proximal demonstratives.

| [i]: Xiangyang, Yanling, Miluo, Pingjiang, Liuyang, Xinhua. |

| [a]: Ningyuan, Jiangyong, Guzhang, Fenghuang, Mayang. |

| [n]: Loudi. |

| [ɤ]: Chaling. |

These single-phoneme demonstratives are also the result of phonological reduction due to cliticization. Within the same dialectal family, these vowels often occur at the nucleus of demonstratives, as shown in Table 24.

Single Nasals and vowels encoding demonstratives in the Xiang Family.

| Subdialects | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|

| Guiyang | ki 41 | kai 41 |

| Guzhang | ai 33 | oŋ 33 |

| Shuangpai | ʦɤ 25 | la 25 |

Among the 930 subdialects of Cao (2008), there are three exceptions to the phonological rule. All of them have [pi44] as their distal demonstratives, where the onset is [p], the consonants with the lowest degree of sonority, and the nucleus is [i], the vowel with the lowest sonority value. Their corresponding sounds in proximal syllables are more sonorous, cf. Table 25.

Three exceptions to the phonological principle.

| Subdialects | Provinces | Dialectal family | Proximal | Distal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanshan | Hunan | Xiang | ɔi/uai | pi 44 |

| Xinfeng | Jiangxi | Gan | ɡia | pi 44 |

| Tongshan | Hubei | Northern dialect | kʰɑ | pi 44 |

These distal demonstratives have a similar phonological form as bǐ [pi213], which emerged in Archaic Chinese and was replaced around the tenth century. It is likely that these three subdialects still retain the relics of the old distal demonstratives.

It thus seems that the phonological rule posited in this article worked even in Archaic Chinese. The old pair of demonstratives cǐ [tsi213] and bǐ [pi213] has been reconstructed as [tshǐe2] and [pǐai2] (Li and Zhou 1999: 56), with an increase in sonority from the first nucleus [i] to the second [a].

5 Iconicity between acoustic property and distance

The correspondences between the phonological forms of demonstratives and their functions represent a specific type of iconicity.[24] Iconicity is regarded as being in contrast to arbitrariness, and it is the opposite of a symbolic relation according to Peirce (1974). Traditionally, the study of iconicity has mainly been restricted to onomatopoeia and sound symbolism, a marginal phenomenon in the lexicon of any language (Van Langendonck 2007). In the past two or three decades, the perspective has been broadened to the correspondences between linguistic forms and their functions, e.g., with respect to adjacency and isomorphism (e.g., Hudson 1984: 98; Kleiber 1993: 105). Haiman (1985) maintains that iconicity should be looked for in the system of grammatical rules for combining words to express complex concepts. It is generally agreed upon that there is iconicity if something in the form of a sign reflects something in the world, normally through some mental process. This means that something in the form of a linguistic sign, through its function, reflects something in its referent (Mayerthaler 1980, 1988). In this broad sense, demonstratives can be regarded as instantiating a kind of iconicity.

The phonology and semantics of demonstratives are a puzzle of linguistic theory. Langendonck (2007) claims that demonstratives such as this and that are ‘conventional signs’ and are by nature symbolic, which stands in opposition to onomatopoeia or sound symbolism, as mentioned above. However, conventionality does not necessarily entail arbitrariness. In fact, the present analysis shows that iconicity can definitely function within and together with the conventionalized part of a linguistic system. As mentioned earlier, Woodworth (1991), having examined 26 geographically unrelated languages, found a strong correlation between the form and function of proximal and distal demonstratives: proximal ones tend to use [i], the least sonorous vowel, and distal ones typically use [a], the most sonorous vowels. She concluded that this observation forms the basis of a relation between the vowel sonority of proximal and distal forms and their meanings, from a cross-linguistic point of view. In line with Woodworth, Traunmüller (1996) investigated a wider range of languages and found that 71% of the languages fall into this pattern. Nevertheless, Traunmüller correctly notes that if there is in fact sound symbolism in proximal and distal demonstratives, the relationship between sound and meaning would have to be relatively abstract, since there are no sounds to imitate in reality, as pointed out previously.

Therefore, we are dealing with a puzzle: on the one hand, demonstratives are semantically abstract like grammatical morphemes, on the other hand, they reflect a correlation between phonological form and meaning similar to that observed in onomatopoeia or sound symbolism. How to explain this peculiar phenomenon is a challenge. Thus far, all the types of iconicity that have been identified in the literature are projections from reality into language, but in the case of demonstratives that projection seems to take the opposite direction, i.e., from language to reality, specifically through human cognition regarding the acoustic property of sounds. Consider the definition of ‘sonority’ in Crystal (2008):

A term in auditory phonetics for the overall loudness of a sound relative to others of the same pitch, stress and duration. Sounds are said to have an ‘inherent sonority’, which accounts for the impression of a sound’s ‘carrying further’, e.g., [s] carries further than [ʃ], [a] further than[i]. (Crystal 2008: 442)

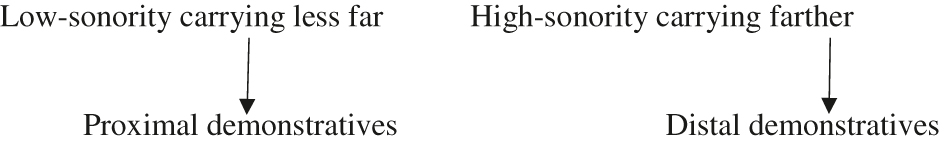

Thus, the most important phonological devices distinguishing proximal and distal demonstratives, namely, the sonority values of sounds, actually reflect iconicity between the loudness of sounds and the distance that a demonstrative indicates. This can be summarized as shown in (18):

The principle of iconicity can explain why there is a non-arbitrary relationship between the phonological form and meaning of demonstratives in many languages of the world. English still employs a similar phonological strategy to distinguish its proximal from distal demonstratives: this [ðis] and that [ðæt] share the same consonants at the onset, but the former uses the high vowel [i] as the nucleus and the latter uses the open vowel [æ]. As noted early, the sonority of [æ] is higher than that of [i]. As was also mentioned earlier, the same device is used by many other languages to distinguish their proximal from distal demonstratives (Traunmüller 1996). Thus, the present analysis may be applicable to the derivation between proximal and distal demonstratives in many other languages.

In short, the formula in (11) actually reflects iconicity between the acoustic properties of sounds and the referents of demonstratives.

6 Conclusions

The phonological rule that has been identified in this study can explain nearly 99% of the phonological forms of proximal and distal demonstratives within a database consisting of more than 1000 subdialects that comprehensively cover all the major dialectal families of Chinese. The present analysis has not only proposed a new solution to the great puzzle regarding the origins of demonstratives, it has also identified a new type of mechanism for the emergence of grammatical morphemes. Both processes of grammaticalization and instances of phonological derivation were shown to responsible for producing new grammatical items.

The phonological rule proposed in this article can also explain why there is a considerable number of phonological forms for demonstratives in Chinese dialects. The formula “f s (Odistal) ≥ f s (Oproximal)” requires that the sonority value of the consonant at the onset of distal demonstratives must be equal to or greater than that of the corresponding proximal demonstrative pronouns. The onsets of the three lexical sources are [k], [tʂ], and [d]. There are thus many options for consonants at the onset of distal demonstratives. As a result, nasals, liquids, glottals, and glides account for approximately 75% of the onsets of the distal demonstratives in the more than 1000 subdialects. Within a subdialect, the onset must be specified by a fixed consonant, but the nucleus may contain a range of vowels, resulting in numerous forms of demonstratives. In all subdialects, proximal as well as distal demonstratives have two to six distinctive phonological forms.

This comparative study of demonstratives shows that there are clear phonological correlations between proximal and distal demonstratives across more than 1000 dialects in Chinese. This suggests that there may also be certain phonological rules that are responsible for the derivation between them. Future studies in this direction will definitely provide new insights into the mechanism of the design principles underlying human languages.

References

Ariel, Mira. 1990. Accessing noun-phrase antecedents. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Beida [Linguistics program, Department of Chinese language and literature, Peking University]. 1995. Hanyu fangyan cihui [The dialectal lexicon of Chinese]. Beijing: Yuwen Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bühler, Karl. 1934. Sprachtheorie: Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Jena: Fischer.Search in Google Scholar

Cao, Zhiyun (ed.). 2008. Hanyu fangyan dituji (yufa juan) [Linguistic atlas of Chinese dialects (Volume of grammar)]. Beijing: Shangwu yinshuguan.Search in Google Scholar

Cardona, George. 1965. Gujarati reference grammar. Philadelphia, PA: University of Philadelphia Press.10.9783/9781512801224Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam & Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, John & Colin Yallop. 1992. An introduction to phonetics and phonology. Oxford: Blackwell.10.2307/416373Search in Google Scholar

Claudi, Ulrike. 1985. Zur Entstehung von Genussystemen: Überlegungen zu einigen theoretischen Aspekten, verbunden mit einer Fallstudie des Zande. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.Search in Google Scholar

Clements, George N. 1990. The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabification. In John Kingston & Mary Beckman (eds.), Papers in laboratory phonology 1: Between the grammar and physics of speech, 283–333. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511627736.017Search in Google Scholar

Corbett, Greville G. 2004. Number. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Crystal, David. 2008. A Dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 6th edn. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9781444302776Search in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives: Form, function, and grammaticalization. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.42Search in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 2006. Demonstratives. In Keith Brown (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, 430–435. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/04299-1Search in Google Scholar

D’Onofrio, Annette. 2014. Phonetic detail and dimensionality in sound-shape correspondences: Refining the Bouba-Kiki Paradigm. Language and Speech 57(3). 367–393.10.1177/0023830913507694Search in Google Scholar

Dryer, Matthew S. 2013. Indefinite articles. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.Search in Google Scholar

Duanmu, San. 2007. The phonology of standard Chinese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199215782.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Ehlich, Konrad. 1979. Verwendungen der Deixis beim sprachlichen Handeln. Lang: Bern.Search in Google Scholar

Greenberg, Joseph. 1978. How does a language acquire gender markers? In Joseph H. Greenberg, Charles A. Ferguson & Edith A. Moravcsik (eds.), Universals of human language: Word structure, Vol. 3, 47–82. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.Search in Google Scholar

Haiman, John. 1985. Natural syntax: Iconicity and erosion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1075/tsl.6Search in Google Scholar

Harris, Alice C. & Lyle Campbell. 1995. Historical syntax in cross-linguistics perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620553Search in Google Scholar

Haspelmath, Martin. 1993. A grammar of Lezgian. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110884210Search in Google Scholar

Heffner, Roe-Merrill S. 1950. General phonetics. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.Search in Google Scholar

Heine, Bernd, Ulrike Claudi & Friederike Hünnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization: A conceptual framework. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar