Abstract

This study provides new data on the use of agent focus (AF) versus transitive constructions in Kaqchikel. This work follows up on a study done by Heaton et al. (Heaton, Raina, Kamil Deen & William O’Grady. 2016. An investigation of relativization in Kaqchikel Maya. Lingua 170. 35–46) which found that while questioning the subject of a transitive verb regularly requires the use of AF or an antipassive, relativizing the subject of a transitive verb does not. Present findings show that AF is only common in half of the six primary syntactic contexts that allow it, which is unexpected under the assumption that AF is a last resort strategy. I suggest that the differences between these syntactic contexts in Kaqchikel are related to the presence of a preverbal lexical NP element which is available to be interpreted as the agent. Comparative descriptive evidence is also compiled demonstrating that transitive verbs are possible in syntactic contexts that traditionally have been considered to require AF across Eastern Mayan languages.

1 Introduction

The present study uses experimental techniques to investigate the distribution of the agent focus (AF) construction in Kaqchikel (ISO 639-3: cak, Glottocode: kaqc1270), a Mayan language belonging to the K’ichean subgroup. The usual generalization is that in Eastern Mayan languages there are restrictions on the direct relativization, questioning, and/or focusing/clefting of ergative arguments (see e.g., Aissen 2017a; Campbell 2000; Dayley 1981; Larsen and Norman 1979; Stiebels 2006; Trechsel 1993) (for comments on Western Mayan see Section 5). To circumvent these restrictions, Mayan languages commonly use either antipassives or AF, a construction unique to Mayan (described below). In addition to using AF or antipassive constructions to relativize, question and focus/cleft ergative arguments, in Kaqchikel these constructions are also used in indefinite argument contexts (‘a girl hugged the boy’), existential indefinite contexts (‘someone hugged the boy’), and negative indefinite contexts (‘no one hugged the boy’), only when the relevant argument is the subject of a transitive verb (all six environments are henceforth discussed together as “focus contexts”).[1] Examples and a discussion of each of these focus contexts are provided in Section 3.

The AF construction in Kaqchikel, as in other Mayan languages, has been characterized as morphologically intransitive but syntactically transitive (see e.g., Aissen 1999: 452). AF in Kaqchikel has the following key characteristics:

The verb only cross-references one of its two core arguments, which can be either the agent or the patient depending on the respective person and number of the participants;

One of the arguments must be third person (AF is not available with two local person arguments);

The construction is indicated by a verbal suffix which is -o for root transitives and -n for derived transitives;[2]

It is used in focus contexts involving A (ergative) NPs, and cannot be used when focusing O or S (absolutive) NPs;

The patient NP is not oblique, and it can be overt or pro-dropped (syntactically present but unpronounced).

An example of AF in Kaqchikel is given in (1a), where the agent is focused, which contrasts with the transitive construction in (1b), where the patient is focused.

| xa xe | ri | xtän | n-Ø-u-q’ete-j | ri | ala’. |

| only | det | girl | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-hug-tr | det | boy |

| ‘The boy is hugging only the girl.’ | |||||

In addition to the AF construction, Kaqchikel has an antipassive construction which only appears in the same limited syntactic environments as AF constructions. This antipassive shares a marker with AF – -o for root transitive verbs, -n for derived transitive verbs – but unlike AF, the patient appears in an oblique phrase and the verb invariably cross-references the agent. It also can be used with two local persons.[5]

| xa xe | ri | ala’ | n-Ø-q’ete- n | r-ichin | ri | xtän. |

| only | det | boy | ncompl-3sg.abs-hug- antip | 3sg-obl | det | girl |

| ‘Only the boy is hugging the girl.’ | ||||||

AF and this antipassive construction both function the same way with respect to questioning, relativizing, etc., and speakers can use both constructions interchangeably in the tasks reported on here (although AF is approximately four times as frequent as the antipassive in these contexts in Kaqchikel; see this dataset and Stiebels [2006: 513] on other Mayan languages). As such, both structures will be discussed together here under the umbrella of “AF/AP”.

There is an extensive body of formal syntactic literature on AF which informs expectations about how AF operates in Mayan languages. To frame the discussion in generative terms, some Mayan languages have an extraction asymmetry wherein ergative arguments are unable to undergo A-bar extraction, which involves movement of the transitive subject from the postverbal subject argument position to the preverbal focus position (Mayan languages are verb-initial). Several analyses have derived this pattern from the way nominal arguments are case-licensed (see e.g., Coon et al. 2014). Such case-licensing explanations consider AF a necessary “last resort” (see e.g., Campana 1992; Coon et al. 2014: 219; Ordóñez 1995; see also Aissen [2017a] for a summary and comments), which precludes the possibility that it could be optional in those contexts where it appears.[6] Although she proposes a different analysis, Aissen (2011: 10) states with respect to K’iche’ that “It is a general property of [K’iche’] that the transitive form is possible (when A is extracted) only when the AF form is impossible”, which likewise indicates that AF and transitive verbs should be in complementary distribution. This same type of generalization is also found in the descriptive literature for Kaqchikel (García Matzar and Rodríguez Guaján 1997: 379).

Despite the above statements, Stiebels (2006: 510–511) mentions that AF/AP constructions are not always obligatory in at least three Mayan languages (Mam, Poqomam, Poqomchi’), such that the direct relativization, questioning, etc. of the ergative argument of a transitive verb is sometimes possible in some of these focus contexts. Additional evidence along these same lines comes from Heaton et al. (2016) who found that while questioning the subject of transitive verb in Kaqchikel almost always involves the use of an AF/AP construction, they rarely appear in picture elicitation contexts when relativizing transitive subjects.

The present study builds on the findings of Heaton et al. (2016) to provide a more complete picture of the use of AF/AP constructions in Kaqchikel by documenting the incidence of AF/AP versus transitive constructions in four additional focus contexts. This paper describes the results of four experimental tasks designed to elicit AF/AP clauses in contexts which permit them. The data presented here address the following questions:

With what frequency do Kaqchikel speakers use AF/AP constructions in focus contexts? Are there any contexts in addition to relativization in which a transitive construction is more frequent than AF/AP constructions?

Are there any other factors which influence the use/non-use of AF/AP constructions?

What generalizations can be made about contexts where AF/AP constructions appear less frequently?

How do the facts for Kaqchikel compare to descriptions of the distribution of AF/AP constructions in other Eastern Mayan languages?

An explanation of the design of all four tasks is presented in Section 2, and each task and their results are detailed in Section 3. Section 4 provides a summary of results across tasks and presents possible explanations for the observed patterns. Evidence of similar phenomena in other Mayan languages is given in Section 5, and Section 6 offers concluding remarks.

2 Task design

There are six primary focus contexts in which AF/AP constructions appear in Kaqchikel: wh questioning A arguments, relativizing A arguments, focusing/clefting A arguments, indefinite A, existential indefinite A (‘someone/something’), and negative indefinite A (‘no one/nothing’) contexts. The expectation based on the literature to date has been that AF/AP constructions are required in all of these contexts in Kaqchikel. To elicit subject and object wh questions and relative clauses, Heaton et al. (2016) used picture description tasks which carefully manipulated the context to make specific comparisons. The present study uses the same basic methodology to investigate which construction(s) are used in the remaining four contexts. The benefit of picture elicitation is that it allows the researcher to control contextual variables while avoiding translation, and allows the speaker to provide a more naturalistic response.

The stimuli for all four tasks were designed to invite single-sentence responses to each image. The question was, when presented with the opportunity to use an AF/AP construction, would speakers use one, or would they (and could they) use a fully transitive construction. The possible responses to a sample existential indefinite A subject item are given in (2).

| Expected: |

| k’o | n-Ø-k’aso- n | ri | xtän. |

| exist | ncompl-3sg.abs-wake- af | det | girl |

| ‘Someone is waking the girl.’ | |||

| Possible?: | |||

| k’o | n-Ø-u-k’aso- j | ri | xtän. |

| exist | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-wake- tr | det | girl |

| (*)‘Someone is waking the girl.’ (But acceptable as ‘The girl is waking someone.’) | |||

As suggested by the glosses for (2b), if it were possible to use a transitive verb to say ‘someone is waking the girl’, k’o nuk’asoj ri xtän could be interpreted as having either a focused agent or a focused patient. Some Mayanists have argued that the function of AF/AP is to disambiguate between an agent and a patient interpretation in just these sorts of situations (see Section 4.2 for more discussion). This cannot be the whole story, since AF/AP constructions are used with local persons in Kaqchikel. However, since the goal was to encourage the production of AF/AP clauses, all of the scenarios depicted in the picture elicitation tasks involved singular third persons acting on singular third persons. If the primary function of AF/AP constructions is to disambiguate between an agent and a patient interpretation, we would expect them to appear in 3 > 3 contexts like these.

All four tasks involved the same basic design which manipulated both the animacy of the patient (human vs. inanimate) and the focused argument (the agent vs. the patient). Each test consisted of 20 target items, five from each of the four conditions generated by the combination of these two variables, illustrated in Table 1.

Test conditions.

| Matched animacy | Mismatched animacy | |

|---|---|---|

| Focused agent | Human→human, focused agent | Human→inanimate, focused agent |

| Focused patient | Human→human, focused patient | Human→inanimate, focused patient |

The two conditions which targeted focused patients are essentially control items, where transitive verbs are expected and AF/AP verbs are ungrammatical. However, passives were also acceptable in focused patient conditions, and the rate of use for passives is discussed where relevant to the results. Animacy was included as a parameter because it is relevant to discussions of ambiguity (see Section 4.2), even though the animacy of the patient was found not to be a significant factor in Heaton et al. (2016).[7]

In all tests, one block of items with a focused agent was presented first in order to avoid priming effects from the expected use of transitive verbs in patient conditions. However, there were no discernable priming effects of this kind; responses in the initial block of focused agent items were not notably different from responses to those focused agent items which appeared after focused patient items. The four conditions in Table 1 were interspersed as blocks with respect to matched versus mismatched animacy. The five items in each of the four conditions were randomly interspersed within their condition. Each item was introduced by a prompt that where possible included neither a transitive verb nor an AF/AP construction, likewise to avoid any potential priming effects. The prompts for each task are described in the following subsections.

All tasks were conducted by the researcher in Kaqchikel. Interviews took place either in speakers’ homes or in their places of work, and speakers were invited to participate via existing social networks. Thirty native Kaqchikel speakers participated in all four tasks. Since Heaton et al. (2016) found age to be a significant factor, speakers were equally distributed across three different age categories: ten speakers between 20 and 30, ten speakers between 31 and 50, and ten speakers over the age of 51.[8] These categories broadly capture changes in the educational landscape of rural Guatemala, where older people were less exposed to compulsory Spanish-medium education.

In preparation for each task, speakers were asked to describe pictures in a single sentence in response to a prompt. Participants were trained on the format for each task using test items that involved intransitive scenarios. All four tasks were presented in the same session, but with small breaks between each task. Each individual task took speakers between five and 10 minutes to complete. The four tasks were presented in the following order: indefinite arguments (‘a(n)’), focus words (‘only’), negative indefinite items (‘no one/nothing’), then existential indefinite items (‘someone/something’). This order reflects a progression from simple to more complex tasks (see Section 3), while also separating the indefinite and existential indefinite tasks which used similar prompts and images. After all four tasks were completed, participants were asked several short follow-up questions: if they had predominantly used AF/AP constructions in focused agent conditions, could they also use a transitive verb (and vice-versa)? If so, is there any difference in meaning/use? Do they perceive one as being more common/acceptable than the other?

Responses were coded as either AF/AP (1) or transitive (0). Responses that were infelicitous, ungrammatical, or did not contain all the necessary elements (or were questionable on these points) were omitted from the count. See the accompanying documentation for more information.

3 Individual tasks and results

3.1 Focus word task (xa xe ‘only’)

Focus in Kaqchikel can be indicated in several ways, including focus particles (e.g., ja ‘foc’) and other focus words (e.g., xa xe ‘only’). This task used xa xe ‘only’, which avoided serious overlap with cleft-type focus constructions/relative clauses (‘this is the man that …’), which were already tested by Heaton et al. (2016). The focus word task involved sentence correction, where the prompt included an incorrect statement, and speakers were instructed to correct that statement by saying ‘No, only the [agent/patient] …’. A sample item is given in Figure 1.[9]

Focus word task: Human→human, focused agent.

| Prompt: |

| k ’o | jun | ala’, | jun | xtän, | chuqa | jun | achin. | Chupam | ri | achib’äl, |

| Exist | one | boy | one | girl | also | one | man | in | det | picture, |

| n-Ø-ki-jïk’ | ri | xtän | che | ka’i’. | ||||||

| ncompl-3sg.abs-3pl.erg-pull | det | girl | prep | two | ||||||

| ‘There’s a boy, a girl and a man. In the picture, the two of them are pulling the girl.’ | ||||||||||

| Target response: |

| manäq, | xa xe | ri | ala’ | n-Ø-jik- o | / (*)n-Ø-u-jïk |

| no | only | det | boy | ncompl-3sg.abs-pull- af | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-pull |

| ri | xtän. | ||||

| det | girl | ||||

| ‘No, only the boy is pulling the girl.’ | |||||

The expectation was that speakers would use an AF/AP construction in the focused agent conditions, and that a transitive verb would be ungrammatical, indicated by (*) in (4) and subsequent examples. Responses involving transitive verbs in focused agent conditions would be unexpected.

3.1.1 Results

The number of responses that involved the use of AF/AP constructions versus fully transitive constructions in agent conditions with xa xe ‘only’ by age group are given in Figure 2. Most notably, transitive verbs are used much more frequently than AF/AP constructions by members of all age groups.[10]

Frequency of AF/AP versus transitive verbs in agent conditions with xa xe ‘only’ by age.

Example (5a) provides a typical response to focused agent items which involved the use of a transitive verb (as in the majority of responses), while (5b) provides an example of the corresponding response involving the use of an AF construction (as in a minority of responses). This particular item depicted a woman pushing a boy on a swing set while a man stood nearby with his hands in his pockets.

| Typical transitive response: |

| xe | ri | te’ej | n-Ø-u-chokomi-j | ri | ala’. |

| only | det | mother | ncompl-3SG.ABS-3sg.erg-push- tr | det | boy |

| ‘Only the mother is pushing the boy.’ [associated audio-5a-Heaton.wav] | |||||

| Typical AF response: | |||||

| xa xe | ri | ixöq | n-Ø-chokomi- n | ri | ala’. |

| only | det | woman | ncompl-3sg.abs-push- af | det | boy |

| ‘Only the woman is pushing the boy.’ [associated audio-5b-Heaton.wav] | |||||

Recall that the focused patient conditions were essentially control items where AF/AP constructions are not possible and transitive verbs are expected. However, there were 38 instances of passives in patient conditions for the xa xe ‘only’ task, one of which is given in (6).

| xa xe | ri | xtän | n-Ø-q’et- ëx | r-uma | ri | xta | ala’. |

| only | det | girl | ncompl-3sg.abs-hug- pass | 3sg-obl | det | dim | boy |

| ‘Only the girl is being hugged by the boy.’ [associated audio-6-Heaton.wav] | |||||||

This use of passives in patient conditions suggests that transitive verbs are indeed commonly used to indicate that the preverbal NP is the agent in this context, since some speakers feel the need to disambiguate via passivization when the preverbal NP is the patient. This contrasts with few to no attestations of passives in other contexts where AF/AP constructions consistently appear; see for example the results of the existential indefinite task in Section 3.2.1.

3.2 Existential indefinite task (k’o ‘exist’)

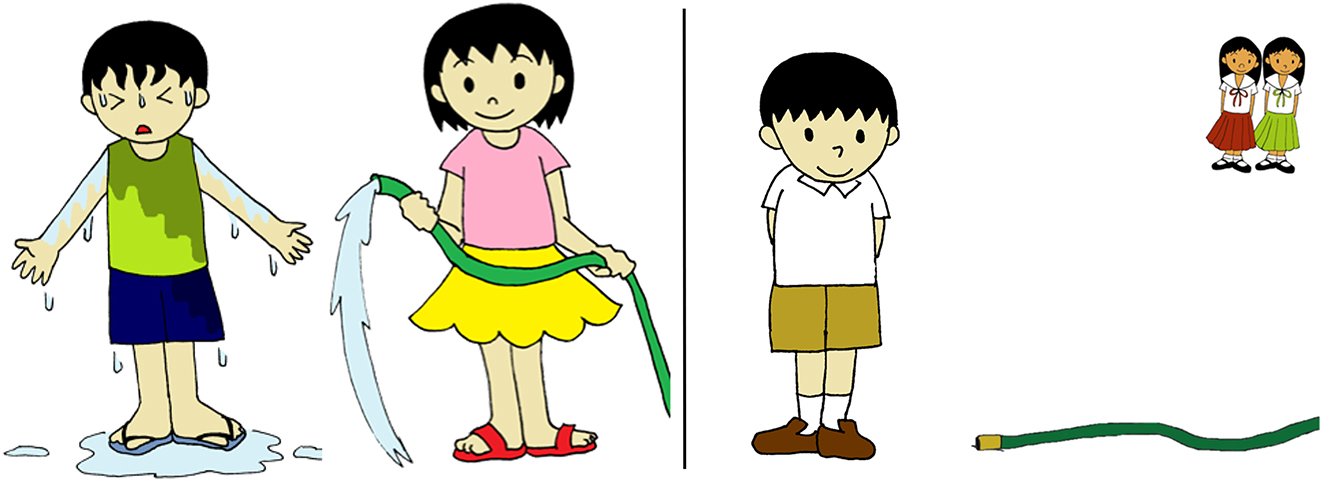

Although the English translation of this construction involves an indefinite pronoun ‘someone/something’, the corresponding target construction in Kaqchikel does not involve an overt pronoun. To express the meaning ‘someone/something’, Kaqchikel uses k’o ‘to exist’ followed by the main verb (as in [8]). To elicit an indefinite, non-specific referent, participants were shown pictures of transitive actions where one person or item was almost entirely obscured by a ‘wall’, as in Figure 3. Participants were trained to begin their statements with k’o as part of the format of the task.[11] The prompt for each item was simply ‘what is happening with ___?’, a statement which in Kaqchikel uses a passive verb.

Existential indefinite task: Human→human, focused agent.

| Prompt: |

| a chike | n-Ø-b’an-täj | r-ik’in | ri | ala’? |

| wh | ncompl-3sg.abs-do-pass | 3sg-with | det | boy |

| ‘What is happening with the boy?’ | ||||

| Target response: |

| k’o | n-Ø-chokomi- n | / (*)n-Ø-u-chokomi-j | ri | ala’. |

| exist | ncompl-3sg.abs-push- af | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-push-tr | det | boy |

| ‘Someone is pushing the boy.’ | ||||

3.2.1 Results

Results show that AF/AP constructions are by far the dominant strategy used with existential indefinite subjects for all age groups (Figure 4). Although transitive constructions were occasionally used in agent conditions by speakers in every age category, when asked about those responses afterward, most speakers rejected the grammaticality of such statements. As such, it seems AF/AP constructions are very common and perhaps mandatory for most speakers in this context. Additionally, passive constructions were unattested in patient conditions.

Frequency of AF/AP versus transitive verbs in agent conditions for the existential indefinite context by age.

An actual response typical of the use of AF in this context is given in (9a) (the most common strategy), while an actual response to the same item involving a transitive verb is given in (9b) (as in 20 responses). This particular item depicted an obscured figure picking a flower.

| Typical AF response: |

| k’o | n-Ø-k’uq- un | la | kotz’i’j. |

| exist | incompl-3sg.abs-pick- af | dem | flower |

| ‘Someone is picking the flower.’ [associated audio-9a-Heaton.wav] | |||

| Minority transitive response: | |||

| (*)k’o | n-Ø-u-k’üq | ri | kotz’i’j. |

| exist | incompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-pick | det | flower |

| ‘Someone is picking the flower.’ [associated audio-9b-Heaton.wav] | |||

3.3 Negative indefinite task (majun [achike ta] ‘no one/nothing’)

The Kaqchikel structure for ‘no one/nothing’ involves the negative ma(n) plus jun ‘one’, optionally followed by the wh word achike ‘who/what’ and the irrealis particle ta, literally something like ‘not one (who) X’. To elicit ‘no one/nothing’ statements, the negative indefinite task involved two contrasting pictures, one of which depicted a transitive action, the other of which depicted the same action but lacked either the agent (for focused agent items) or patient (for focused patient items). A sample item targeting the agent is provided in Figure 5, along with the prompt and target response.

Negative indefinite task: Human→human, focused agent.

| Prompt: |

| w awe’ | ri | ala’ | n-Ø-ch’eqeb’-äx | r-oma | ri | xtän. | Po | re |

| Here | det | boy | ncompl-3sg.abs-soak-pass | 3sg-obl | det | girl | but | this |

| ala’ | re’, | ma-jun | (achike | ta)… | ||||

| boy | this | neg-one | wh | irr | ||||

| ‘Here a boy is being soaked by a girl. But this boy, no one ….’ | ||||||||

| Target response: |

| ma-jun | (achike | ta) | n-Ø-ch’eqeb’a- n | ||

| neg-one | wh | irr | ncompl-3sg.abs-wet- af | ||

| / (*)n-Ø-u-ch’eqeb’a-j | (ri | ala’). | |||

| ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-wet-tr | det | boy | |||

| ‘No one is soaking the boy.’ | |||||

The prompt includes a passive verb in the first sentence to avoid priming a transitive or AF/AP construction. Participants were trained to expect their utterance to begin with majun (achike ta) ‘no one/nothing’, which was also provided at the end of the prompt to help dissuade speakers from providing a passive response. The figures in the background of the second image represent possible agents for the action, likewise to help retain a two-participant interpretation of the depicted scenario.

3.3.1 Results

All speakers who participated in the study used AF/AP forms exclusively in negative indefinite subject contexts across every age group.[12] The follow-up questions also corroborated that AF/AP constructions are mandatory in this context, and there were only six instances of passive verbs in patient conditions. The total numbers of responses by age and construction type are given in Figure 6.

Frequency of AF/AP versus transitive verbs in agent conditions for the negative indefinite context by age.

An actual response typical of the use of AF in this context is given in (12). In this particular item, the first picture showed a girl burying a boy in the sand at the beach. In the second picture, a boy was lying in the sand, unburied, with two other children in the background.

| ma-jun | achike | ta | n-Ø-muq- un . |

| neg-one | wh | irr | ncompl-3sg.abs-bury- af |

| ‘No one buried him [in the sand].’ [associated audio-12-Heaton.wav] | |||

3.4 Indefinite argument task (jun ‘one, a(n)’)

As noted by Broadwell (2000: 3–4), indefinite subjects of transitive verbs appear preverbally and trigger the use of AF (13a). Additionally, indefinite transitive subjects cannot appear post-verbally (13b).

| jun | tz’i’ | x-Ø-b’a’- o | ri | a | Juan. |

| one | dog | compl-3sg.abs-bite- af | det | clf | Juan |

| ‘A dog bit Juan.’ | |||||

| *n-Ø-u-tïj | ri | saq’ul | jun | ak’wal . |

| ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-eat | det | banana | one | child |

| Intended: ‘A child is eating the banana.’ | ||||

These facts were corroborated by the author with several Kaqchikel speakers in elicitation, and similar textual examples like (14) are not uncommon. In this context, the weaver is new to the discourse, and the listener does not know the woman.

| jun | ixöq | x-Ø-kem- o | pe | la | qa-po’t. |

| one | woman | compl-3sg.abs-weave- af | dir | dem | 1pl.poss-blouse |

| ‘A woman wove our blouses.’ [associated audio-14-Heaton.wav] | |||||

As such, indefinite A contexts merit investigation as focus contexts in Kaqchikel.

The task for indefinite As, like the existential indefinite A task, involved the description of a single picture in which a figure in an action was obscured (cf. Figure 7). However, the ‘wall’ that covered the figure was smaller in this task, which encouraged participants to use an NP like ‘a girl’ or ‘a man’, since they could identify some but not all of the features of the figure (although any indefinite NP was accepted). Participants were trained to consider obscured figures indefinite.

Indefinite task: Human→inanimate, focused agent.

| Prompt: |

| a chike | n-Ø-b’an-täj | chupam | ri | achib’äl? |

| wh | ncompl-3sg.abs-do-pass | in | det | picture |

| ‘What is happening in this picture?’ | ||||

| Target response: |

| jun | ala’ | n-Ø-tij- o | / (*)n-Ø-u-tïj | ri | |

| one | boy | ncompl-3sg.abs-eat- af | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-eat | det | |

| saq’ul. | |||||

| banana | |||||

| ‘A boy is eating the banana.’ | |||||

It is important to note that the indefinite A context differs in key ways from the other contexts discussed here. Unlike indefinite A NPs which must appear preverbally and which involve the use of AF/AP constructions (as in 13), indefinite Ps do not have to be preverbal; in fact, indefinite Ps are almost always postverbal, and preverbal indefinite Ps are sometimes judged ungrammatical. This is a point of departure from the other focus contexts discussed here, where questioned, relativized, clefted, etc. objects must be preverbal. Compare the grammatical postverbal indefinite patient in (17a) with the ungrammatical postverbal wh patient in (17b):

| n-Ø-u-tïj | jun | saq’ul | ri | ak’wal. |

| ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-eat | one | banana | det | child |

| ‘The child is eating a banana.’ | ||||

| *n-Ø-u-tïj | achike | ri | ak’wal? |

| ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-eat | wh | det | child |

| Intended: ‘What is the child eating?’ | |||

Additionally, it is possible in Kaqchikel for both arguments of a transitive verb to be indefinite, in which case the expectation is that the indefinite subject will appear preverbally, the verb will show AF/AP morphology, and the indefinite patient will be postverbal, as in (17c). This follows from the fact that an indefinite P NP need not appear in the preverbal focus position.

| jun | ak’wal | n-Ø-tij- o | jun | saq’ul. |

| one | child | incompl-3sg.abs-eat- af | one | banana |

| ‘A child ate a banana.’ | ||||

From the point of view of the other tasks, utterances like (17c) are akin to simultaneous agent and patient condition items, which was an impossibility in the other three tasks. Since definiteness of the patient was immaterial to the definiteness and syntactic position of the agent, responses in patient conditions were tallied according to the relevant variable, the definiteness of the agent.

3.4.1 Results

Despite speakers’ stated grammaticality judgments which favored AF/AP constructions, all speakers used transitive verbs in contexts with indefinite A arguments (Figure 8). In fact, the use of AF/AP clauses was rare for speakers of all ages, and non-existent for the youngest speakers (although all speakers agreed AF/AP constructions were also possible during post-test questioning).

Frequency of AF/AP versus transitive verbs in agent conditions for the indefinite argument context by age.

A sample response from this task involving a transitive verb (the majority strategy) is given in (18a), while one of the nine actual responses involving AF is given in (18b). This particular item depicted an obscured person holding scissors, with a cut-up sheet of paper to their right.

| Typical transitive response: |

| jun | ala’ | x-Ø-u-qupi-j | la | wuj. |

| one | boy | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erc-cut- tr | dem | paper |

| ‘A boy cut the paper.’ [associated audio-18a-Heaton.wav] | ||||

| Minority AF response: | ||||

| jun | ti | winäq | n-Ø-qupi- n | ri | wuj. |

| one | dim | person | incompl-3sg.abs-cut- af | det | paper |

| ‘A person (dim.) is cutting the paper.’ [associated audio-18b-Heaton.wav] | |||||

These data show that AF/AP constructions are clearly not obligatory when a transitive subject is indefinite; to the contrary, they are rarely used.

There were also eight instances of passives in the indefinite P conditions, an example of which is given in (19).

| jun | xta | ala’ | n-i-muq | pa | arena | roma | jun | ti | xtän. |

| one | dim | boy | incompl-3sg.abs-bury. pass | prep | sand | 3sg-obl | one | dim | girl |

| ‘A little boy is getting buried in sand by a little girl.’ [associated audio-19-Heaton.wav] | |||||||||

The proportion of passive responses in object conditions is smaller with indefinite patients than with focused patients in xa xe conditions (6 vs. 16 %, see Section 3.1.1). This is likely related to the fact that indefinite objects are rarely if ever preverbal.

4 Analysis

4.1 Summary of findings

AF/AP and transitive constructions in these additional four focused A contexts are clearly used to different extents. The results of the four tasks discussed here as well as the two tasks from Heaton et al. (2016), which now provide a more complete picture of the use of AF/AP constructions in these contexts in Kaqchikel, are summarized in Figure 9.

Summary of use of AF/AP versus transitive constructions with a focused preverbal agent, as percentages.13

In three of the six contexts examined here – A wh questions, negative indefinite A contexts, and existential indefinite A contexts – a majority of speakers consistently or exclusively used AF/AP constructions. Speakers (even those who sometimes produced responses with transitive verbs in agent conditions) also consistently judged transitive constructions to be ungrammatical in these contexts.

The results of the wh question, existential indefinite, and negative indefinite tasks contrast with the results for the other three contexts – relative clauses, focus word, and indefinite contexts – in which speakers of all ages frequently used transitive constructions in focused agent conditions, to the point where transitive constructions were the most common way of expressing those types of propositions. There is also evidence of differences between these three focus contexts, where AF/AP constructions are more common with focus words and relative clauses than with indefinite As.[13]

To identify meaningful differences between the test results for these different focus contexts, the data were fit to a Bayesian logistic regression model (estimated using six chains of 10,000 iterations and a warmup of 1,000) with weakly informative priors. Results show a meaningful difference between the pattern exhibited for A wh questions (intercept) and all other tests (0 % of the posterior distribution within the region of practical equivalence, with a range of [−0.18, 0.18] and a 95 % confidence interval) with the exception of existential indefinite As, which as shown in Figure 9 have very similar rates of AF/AP usage. There is also a strong negative effect for the patterns of use for AF/AP constructions in focus word, relative clause, and indefinite A contexts (in order of increasing strength) compared to the other three contexts. The magnitude of these differences is illustrated in Figure 10, where Type = 1 represents AF/AP and Type = 0 represents transitive constructions.

Conditional effects of the focus context on AF/AP use.

However, it is important to remember that although less frequent than transitive constructions, AF/AP constructions continue to be possible in A relative clause, A focus word, and indefinite A contexts. But the fact that none of these three contexts consistently involves AF/AP is surprising, given that the expectation from the literature was that AF/AP is always required in the contexts in which it appears (cf. Dayley 1981; García Matzar and Rodríguez Guaján 1997; Trechsel 1993).

4.2 Discussion

Before exploring possible explanations for the observed pattern in Kaqchikel, here is a quick review of the facts and the possibilities: First, A arguments in Kaqchikel are usually postverbal. If A arguments are to appear preverbally in the focus position for the purpose of relativization, questioning, etc. as reported here, the frequent claim in the literature is that an AF/AP construction is required (see citations above). However, given the results from the tasks described in Section 3, clearly the facts are more complicated, since both AF/AP and transitive constructions are used in some focused A contexts. Additionally, there is a clear divide between the three focus contexts for which AF/AP is dominant if not obligatory (wh questions, existential indefinites, and negative indefinites) and those where both transitive and AF/AP constructions are consistently possible (relative clauses, focus word contexts, and indefinites; see Figures 9 and 10). The goal of any analysis would be to explain why the latter three contexts allow both AF/AP and transitive constructions while the former three largely do not.

There are two general approaches one could take to explaining these results:

Questioning, relativizing, or otherwise focusing A arguments does not uniformly require the use of AF/AP, or

AF/AP constructions are required, but instances of transitive verbs in indefinite, relative clause, and focus word contexts actually involve different underlying syntactic structures than when AF/AP constructions appear in those contexts.

Only the latter explanation would be compatible with an analysis of AF as a “last resort”, since by such accounts AF morphology appears in order to allow the extraction of the agent of a transitive verb. This type of analysis readily accounts for the fact that AF is limited to ergative extraction contexts (cf. Coon 2016), but requires that AF consistently appear when transitive subjects undergo A-bar extraction from typical dyadic predicates with two DP arguments.[14] In order to support the hypothesis that AF exists to allow ergative arguments to undergo A-bar extraction, it would be necessary to argue that those instances where transitive verbs appear have distinct derivations from those where AF appears. These distinct derivations would need to produce variants for A relative clauses, focus word contexts, and indefinites which do not have the same sort of A-bar dependency as their counterparts in the same contexts that involve AF/AP. Additionally, there should be no similar derivations that produce transitive structures for A wh questions, existential indefinite, and negative indefinite A constructions, since AF/AP appears to be required for most speakers in those contexts in Kaqchikel.

There are several promising avenues for investigation along these lines. For example, the observed transitive structures could be biclausal constructions (cf. Henderson and Coon 2018; Larsen 1988; Polinsky 2017: 4345–4347; although note that Velleman [2014: 100–112] finds this unsuitable for K’iche’), could involve base-generated topics (Polinsky 2017: 4346), or could have base-generated subjects (e.g., Clemens 2013). Additionally, Coon et al. (2019, n. 22) note that language-specific differences in the feature structure of the A-bar probe could potentially account for the use of AF in some A-bar movement contexts but not others. However, since no analyses to date have been brought to bear on the type of data presented here, investigating these possibilities is left to those who hold this view of Mayan syntax.

Functional approaches to capturing the distribution of AF/AP constructions have often invoked ambiguity as a motivation for the presence of AF/AP in some contexts but not others (cf. Craig [1977: 211–230] on Popti’; Mondloch [1981: 187–190] on K’iche’; Stiebels 2006: 545–548). The general hypothesis outlined in Stiebels (2006) is that AF/AP originated as a means of disambiguation in 3 > 3 (animate > animate) contexts, then became grammaticalized and extended into other, unambiguous domains. Ambiguity has been invoked to account for the impossibility of AF in simple reflexives, V-initial clauses, and clauses with two local persons, which are unambiguous or are otherwise disambiguated, e.g., by basic word order. While ambiguity has also been used as a general explanation for why AF/AP constructions appear when ergative arguments are focused (there is no case marking or verbal cross-reference to differentiate a preverbal third person agent from a patient), this type of explanation has not been applied to the apparent optionality of AF/AP within or between any of the focus contexts under discussion here.

4.2.1 A (different) functional approach

The explanation I entertain here essentially takes the experimental data in Section 3 at face value and accepts that AF/AP constructions are not obligatory in Kaqchikel in some contexts in which they can appear. The goal is then to explain the availability of both transitive and AF/AP structures in A relative clauses, focus word contexts, and indefinite contexts to the exclusion of A wh questions, existential indefinite, and negative indefinite contexts. There are several interacting factors relating to information structure, processing pressures/competition, and diachronic change that are likely affecting the distribution of AF/AP constructions with respect to the six contexts investigated here; the following sections elaborate on each set of factors.

4.2.1.1 Information structure

There is long-standing work on the relevance of givenness (established vs. new information) in Mayan languages (Aissen 2017b; Du Bois 1987; England 1991; Hedberg 2010; Vázquez Álvarez and Zavala 2013; Zavala 1997; inter alia). The general observation has been that there is a dispreference for expressing new information in an A role, meaning that given information is often conveyed with ergative subjects, while absolutive (AF/AP) subjects are preferred for conveying or introducing new information.

There are two primary ways this has bearing on the current results. First, many kinds of focused information inherently involve given participants. Most obviously this applies to the strong contrastive focus environment “only/xa xe”, where a participant is highlighted from the set of already established discourse referents. Relative clauses likewise often (and given the structure of the prompts in the task here, always) involve providing additional information about a known entity already in the common ground. If transitive (ergative) subjects are commonly given, it is plausible that might lead commonly given focused subjects to be expressed in the same way. Conversely, ‘who’, ‘no one’, and ‘someone’ all necessarily refer to new participants. In these cases, the information-structural pressures reinforce the use of a special syntactic construction, and we see few to no transitive constructions being used.

Second, the fact that transitive subjects generally are not new information also has bearing on the indefinite subject data. While indefinite arguments are generally new information, they are not necessarily new to the discourse. Particularly in this task, it is possible that the agent being partially visible in the picture in the task was enough to consider it existing shared information (see also England and Martin [2003: 139–142] on difficulties identifying new mentions in Mayan). Although the generalization in the syntactic literature has been that indefinite A arguments trigger AF (cf. Aissen 2017b: 295; Broadwell 2000), the evidence here suggests that indefiniteness is not sufficient. Indeed, first mentions of new referents are by and large not ergative in Kaqchikel narrative texts (cf. Heaton 2017: 412), suggesting discourse newness is the more relevant factor.[15] It is also possible that not all dialects of Kaqchikel have the same restrictions on indefinite A arguments. For example, Kim (2011) presents examples of transitive sentences with indefinite pre- and postverbal subjects in Patzún Kaqchikel. This is also apparently not a common environment for AF across Mayan languages; of the 15 languages surveyed in Steibels (2006: 511), the only language for which she identified indefinite A arguments are a possible context for AF/AP is Poqomchi’.

That said, these are clearly tendencies; given information can be expressed using AF/AP constructions, and speakers produced both transitive and AF/AP structures in response to the same items with the same prompts in the tasks here. I leave more detailed investigations of how Kaqchikel speakers make real-time choices between transitive, AP, and AF constructions (as well as between AF vs. AP constructions in A wh questions, negative indefinite, and existential indefinite A contexts) for forthcoming research on Kaqchikel information structure.

4.2.1.2 Processing and competition

Many approaches to linguistic typology and explaining the diversity that we observe in the world’s languages invoke general motivating principles like iconicity, economy (Haiman 1983), analogy/uniformity (e.g., Wanner 2006), frequency (Du Bois 1985), and harmony (Smolensky 1986), among others, with the idea that these derive from language-independent cognitive factors (Hawkins 2014; MacDonald et al. 1994; O’Grady 2008). These motivations are often in competition with one another, which not only produces cross-linguistic variation and shapes individual grammars on a diachronic timescale, they also motivate (the often unconscious) choices speakers make synchronically between one construction or another, affect real-time sentence processing and production, and influence first and second language acquisition. The basic explanatory force of these motivations has been leveraged by different theories in different disciplines (e.g., Optimality Theory [Bresnan and Aissen 2002] and Natural Phonology [Donegan and Stampe 1979] in phonology; the Competition Model [Bates and MacWhinney 1982] and the Extended Argument Dependency Model [Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Schlesewsky 2009, 2014] in psycholinguistics; the Competing Motivations Model [Du Bois 1985] and Naturalness Theory [Dressler 2002] in morphology). Although I am not invoking any particular framework here, basic observations from the psycholinguistic and typological literature about competition and the motivations for the use of different linguistic structures are relevant to these data.

In Kaqchikel there are three types of syntactic structures available for expressing dyadic propositions (transitive, AF, AP). The basic thesis is that competition between these possibilities has partially grammaticalized in ways that align with what we know about general motivations in language use and comprehension. First, transitive constructions (including AVO transitive patterns) are hugely more frequent than AF or AP constructions in Kaqchikel, which demonstrates and perpetuates an economy asymmetry that favors transitive constructions (cf. e.g., Bybee 2010; Diessel 2007; Ellis 2002; Haspelmath 2021 on the effects of frequency). Second, there is evidence from multiple subdisciplines of a general actor bias in processing, including among other things for the first eligible NP in the sentence to be the agent (Bickel et al. 2015; Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Schlesewsky 2009, 2014; de Swart and van Bergen 2019; Lamers and de Hoop 2014; Riesberg et al. 2019; van Bergen 2011; inter alia), which applies even in the absence of any verbal information. This is relevant because Kaqchikel relative clauses, indefinites, and focus word constructions all involve preverbal lexical NPs. These are also the contexts where transitive constructions are common.

| xa xe | ri | ti | xtän | n-Ø-u-wüx | ri | xkoya’. |

| only | det | dim | girl | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-harvest | det | tomato |

| ‘Only the little girl is harvesting the tomatoes.’ [associated audio-20-Heaton.wav] | ||||||

| jun | ak’wal | x-Ø-u-tzaq | ri | k’ojlib’äl. |

| one | child | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-drop | det | container |

| ‘A child dropped the container.’ [associated audio-21-Heaton.wav] | ||||

| ri | retal | k’o | pa | ruwi’ | ri | achin | ri | n-Ø-u-tïj |

| det | sign | exist | prep | top | det | man | rel | ncompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-eat |

| ri | wotz’otz’. | |||||||

| det | pork.rind | |||||||

| ‘The arrow is above the man who is eating pork rinds.’ (Heaton et al. 2016: 39) | ||||||||

In contrast, wh questions, negative indefinites, and existential indefinites are introduced by invariant elements (achike ‘who/what’, k’o ‘someone/something’, or majun ‘no one/nothing’). These are the contexts in which speakers overwhelming prefer or require the use of AF/AP constructions:[16]

| ma-jun | chike | ta | n-i-qum-un | r-ichin. |

| neg-one | wh | irr | ncompl-3sg.abs-drink- ap | 3sg-obl |

| ‘No one is drinking it.’ [associated audio-23-Heaton.wav] | ||||

| k’o | n-i-ch’aj-on | ri | tzyaq. |

| exist | ncompl-3sg.abs-clean- af | det | clothes |

| ‘Someone is washing the clothes.’ [associated audio-24-Heaton.wav] | |||

| achike | n-Ø-nim-o | ri | ala’. |

| wh | ncompl-3sg.abs-push- af | det | boy |

| ‘Who is pushing the boy?’ (Heaton et al. 2016: 44) | |||

Given a general actor-first identification bias in language processing, the tendency would be to consider this initial lexical NP the agent, and the subsequent verbal morphology becomes less relevant to the successful interpretation of the utterance (semantic cues have been found to be at least on a par with, and in some cases supersede, syntactic cues [Hawkins 2004; MacWhinney et al. 1984]). In that case, the more economical choice would be to use the more frequent/accessible AVO construction over the less frequent/accessible AVO construction(s), i.e., a transitive rather than AF/AP constructions. The same cannot be said of focus contexts introduced by an invariant element, which do not have an initial lexical A argument and do not inherently provide any information about whether the referent is a possible agent. In these contexts, the form of the verb is the only way to identify who is doing what to whom, so there is more reason to maintain a stricter form-to-function mapping.

Additional data suggest that the presence of a preverbal lexical NP is indeed relevant not just to optional usage but also to the basic acceptability of transitive verbs in all six contexts (Supplementary Material). While transitive constructions in the post-test were often judged ungrammatical with clauses introduced only by k’o ‘someone’, majun ‘no one’, and achike ‘who’, if a lexical NP (a full NP, pronoun, determiner, or numeral) appears with it, the use of a transitive verb becomes more acceptable.[17] The following examples show the acceptability of transitive verbs when an overt lexical agent nominal is present in focus contexts where transitive verbs were not previously an option for most speakers. The fact that expressing a preverbal lexical NP removes the fairly strict requirement for using AF/AP constructions suggests that the information presented by the preverbal NP is influential to the constraints of the syntax.

| *k’o | n-Ø-u-wüx | ri | xkoya’. |

| exist | incompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-harvest | det | tomatoes |

| Intended: ‘Someone is harvesting the tomatoes.’ | |||

| k’o | jun | n-Ø-u-wüx | ri | xkoya’. |

| exist | one | incompl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-harvest | det | tomatoes |

| ‘Someone is harvesting the tomatoes (lit. there exists one [who] …).’ | ||||

| *achike | x-Ø-u-nïm | ri | ala’? |

| wh | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-push | det | boy |

| Intended: ‘Who pushed the boy?’ (grammatical as ‘Who did the boy push?’) | |||

| achike | winäq | x-Ø-u-nïm | ri | ala’? |

| wh | person | compl-3sg.ab-3sg.erg-push | det | boy |

| ‘Which person pushed the boy?’ (or ‘Which person did the boy push?’) | ||||

| *ma-jun | (achike | ta) | x-Ø-u-chojmi-j | ri | b’ey. |

| neg-one | wh | irr | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-fix-tr | det | road |

| Intended: ‘No one fixed the road.’ | |||||

| ma-jun | chi- ke | ( ri | winaq-i’ ) | x-Ø-u-chojmi-j |

| neg-one | prep-3pl | det | person-PL | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-fix-tr |

| ri | b’ey. | |||

| det | road | |||

| ‘None of the people fixed the road.’[18] | ||||

Speakers bring all their cognitive resources to bear when interpreting language (Bates et al. 1982; Clark 1978). From the examples in (26–28), it seems that the interpretation of the preverbal NP as a potential agent not only has to do with the presence of a lexical NP but also other features that make it prominent (cf. Alday et al. 2014). The relevant parameter here is specificity, which presupposes an individual or a set of individuals which may be definite or indefinite (see e.g., Alday et al. [2014: 145] where specificity is a relevant feature of actors). For Kaqchikel it appears that preverbal position and specificity alone are sufficient for the speaker to posit that the initial argument might be the subject, since utterances with preverbal determiners like jun ‘one, a’ and ri ‘the’ without a pronounced nominal (see e.g., [26b]) have the same effect as fully expressed NPs on the acceptability and use of transitive verbs. This is unsurprising from a processing perspective given that subjects are very often specific, both in Kaqchikel and cross-linguistically, since subjects are often grammaticalized discourse topics (Givón 2015; Li 1976) and topics are generally definite (cf. Aissen 1992).

Additional data also demonstrate that the generally attested tendency to interpret the first eligible argument as the agent is indeed present for Kaqchikel speakers. Native Kaqchikel speakers (ages 45–65) were presented with sentences with unambiguous patient focus, but where the patient was human and therefore could initially be misinterpreted as the agent before hearing the rest of the sentence (as in 29). Speakers were asked for their initial interpretation.

| ja | ri | winäq | x-Ø-u-ti’ | ri | wonon. |

| foc | det | person | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-sting | det | bee |

| ‘It is the person [whom] the bee stung.’ | |||||

The majority of speakers responded that their initial reaction was that the sentence was unacceptable, and it sounded as if the person was stinging the bee. As such, the tendency to initially read ‘person’ as the subject absent other context (and despite transitive constructions traditionally being for non-agent focus) suggests that the presence of preverbal lexical NPs which are likely to be agents begs a subject interpretation in Kaqchikel. England (1991: 472) additionally has reported that Kaqchikel speakers sometimes have difficulty interpreting V-initial sentences, despite that fact that VOA/VAO orders are considered more pragmatically neutral.

There is cross-linguistic evidence that this same tendency exists in other Mayan languages. There is a documented tendency for preverbal human lexical NPs to be interpreted as the agent, particularly in relative clauses, in Eastern as well as Western Mayan languages (cf. Can Pixabaj [2007: 510] on Uspantek; Clemens et al. [2015] on Ch’ol and Q’anjob’al). Clemens et al. (2015) note that these results would seem not to support a processing explanation for syntactic ergativity (at least with respect to relative clauses), since extracting ergative arguments does not appear to increase processing load. Based on the Kaqchikel data here, the argument would be that there could indeed be a processing explanation for syntactic ergativity, namely that the interactions of competing factors (like agent-first vs. absolutive biases) grammaticalize in different ways in different languages (and in different syntactic contexts).

4.2.1.3 Diachronic considerations

The external factors that influence grammatical patterns in language synchronically are also generally considered to shape grammar on a diachronic scale (cf. Du Bois 2014: 277; Malchukov 2014: 40). Grammatical rules and conventions arise from probabilistic form-to-function mappings (routines) that strengthen and rigidify over time (see e.g., MacWhinney et al. 1984; O’Grady 2005: 212). Additionally, Hawkins (1990: 246, 2004: 56) has suggested that the degree of grammaticalization of a particular pattern happens in proportion to and only in areas where there is a processing benefit.

While Kaqchikel speakers are actively making an online choice about which of several possible structures they will use, the primary issue I want to address here is more of a diachronic one, related to the grammaticalization of these structures such that transitive verbs are available along with AF/AP constructions in one set of contexts but not another set. The suggestion is that the processing and discourse pressures outlined in the previous two sections (primarily agent first, but also frequency/economy of transitives and preferences in the expression of given vs. new arguments) have over time caused there to be a grammaticality difference whereby focus contexts that involve a preverbal lexical NP can involve transitive verbs, while those without a preverbal lexical NP lack that pressure and more rigidly maintain special coding (AF/AP).

This analysis is compatible with historical views of K’ichean wherein ergative extraction restrictions were formerly more uniform across A-bar contexts, as well as views where AF has only ever been applied more narrowly. Under the first view, the use of transitive constructions in these six focus contexts is innovative: because of processing and discourse pressures, transitive verbs have gained broader acceptability in contexts which historically only permitted AF/AP constructions when a lexical A argument is focused. Alternately, if AF/AP constructions are special mechanisms that arose from a need to differentiate agent and patient focus (for processing and/or ambiguity-related reasons, possibly along the lines of Stiebels [2006]), then those mechanisms would have arisen in focus contexts involving an invariant initial element, since grammatical roles must be read off the verb. We might then posit that AF/AP constructions were optionally extended to the other focus contexts due to contextual similarities. Transitive verbs dominate in focus contexts with preverbal lexical A arguments because they are and have been the default strategy.

While early textual evidence is limited, England (1991: 473) provides an example of a transitive verb in a focus word context from 16th-century Kaqchikel. If the use of transitive verbs in contexts with preverbal lexical A arguments were an innovation, that innovation would have predated the colonial era. On the other hand, if the use of AF/AP constructions in K’ichean developed in focus contexts involving an invariant initial element and then spread, we might expect more uniformity in the use of AF/AP constructions in those contexts, and then probably a great deal of variability in AF/AP use in other focus contexts across K’ichean. A summary of descriptive reports from other Mayan languages is compiled in Section 5. While information on focus contexts beyond relative clauses, wh questions, and focus word contexts is limited, the data available suggest that this pattern holds generally, but not necessarily at an individual language level: transitive constructions are possible when relativizing A arguments in all K’ichean languages, but they are also acceptable in subject wh questions in at least two other K’ichean languages. The evidence found here of age-grading, wherein younger speakers are more likely to use and find transitive verbs acceptable in these contexts, might be suggestive of either a historical pattern of the generalization/extension of transitive verbs, or a new, additional shift in favor of generalizing AVO transitive constructions.

4.2.2 A note on ambiguity

This analysis of the distribution of Kaqchikel AF/AP constructions is similar in some ways to ambiguity-related explanations, since it suggests that contextual information rather than syntactic structure alone informs speakers’ use of AF/AP. Also, constructions involving a lexical NP are inherently less ambiguous than those that do not because the latter conveys less information (no animacy, definiteness, etc.). However, ambiguity (at least synchronically) is not a decisive factor in the present distribution of AF/AP constructions in Kaqchikel. For instance, if ambiguity were a factor, we would expect that the unambiguous human > inanimate conditions should not involve AF/AP as frequently as the ambiguous human > human conditions. However, in both Heaton et al. (2016) and the current study, there was no significant difference in the incidence of AF/AP constructions between human > human and human > inanimate conditions. This suggests that only the characteristics of the initial NP, not ambiguity in the semantic relationship between the two NPs, is relevant to the use of AF/AP versus transitive verbs in Kaqchikel.

5 Examples beyond Kaqchikel

As noted in Heaton et al. (2016: 45), comparative evidence suggests that this type of variability in the use of AF/AP constructions in different contexts appears elsewhere in Mayan. However, it is useful to say more about the specific nature of that variation and how it relates to the proposed analysis. For Mam, England (1983: 214–218) describes a pattern very similar to what we find here for Kaqchikel in that antipassivization is required for wh questions, but optional for argument focus and relative clauses. Relatedly, Ayres (1983: 31–33) notes for Ixil that while AF (referred to as TSI ‘transitive subject indexing’) is mandatory in wh questions and in contrastive focus situations, it is optional in relative clauses. As for other K’ichean languages, Mondloch (1981) includes examples such as the utterances in (30) which show that AF/AP constructions are possible but not mandatory in A wh questions.

| xačin | š-Ø-u-č’ay | ri: | ak’a:l? |

| wh | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-hit | det | child |

| ‘Who hit the child?’/‘Who did the child hit?’ | |||

| (Mondloch 1981: 244) | |||

| xačin | š-Ø-č’ay- ow | ri: | ak’a:l? |

| wh | compl-3sg.abs-hit- af | det | child |

| ‘Who hit the child?’ | |||

| (Mondloch 1981: 246) | |||

Mondloch (1981: 245) states that although AF and AP constructions are the more common strategies for forming A wh questions, at times transitive constructions are used and context must disambiguate. The same variation in the use of AF/AP constructions and transitive verbs in A wh questions in K’iche’ is recorded by Larsen (1987: 45). Mondloch also notes with respect to relativization that “sentences […] with relativized ergative subjects, even though they do occur, are often judged unacceptable by reflective [K’iche’] speakers” (1981: 228). He provides examples of transitive clauses with relativized ergative subjects like (31a) which contrast with the use of AF in relative clauses, as in (31b).

| š-Ø-pe: | le: | ačih | le: | š-Ø-u-kuna- x |

| compl-3sg.abs-come | det | man | rel | compl-3sg.abs-3sg.erg-cure- tr |

| w-ačaxi:l. | ||||

| 1sg.poss-husband | ||||

| ‘The man came who cured my husband.’/‘The man who my husband cured came.’ | ||||

| (Mondloch 1981: 189) | ||||

| š-Ø-q-il | le: | išoq | le: |

| compl-3sg.abs-1pl.erg-see | det | woman | rel |

| š-Ø-q’o?- w | le: | a-po?t. | |

| compl-3sg.abs-embroider-af | det | 2sg.poss-blouse | |

| ‘We saw the woman who embroidered your blouse.’ | |||

| (Mondloch 1981: 216) | |||

This suggests that K’iche’, like Kaqchikel, Ixil, and Mam, allows ergative arguments to be relativized, even if the AF/AP form is often considered the preferred (or only) form in elicitation.

Along these same lines, Du Bois (1981: 243, 252–253) describes AF/AP constructions as optional in A wh questions and relative clauses in Sakapultek, and Barrett (1999: 266–267) notes that AF/AP constructions are not obligatory when relativizing A arguments in Sipakapense. For Tz’utujil, Dayley (1985: 348) states that although AF/AP constructions are almost always used when relativizing A arguments, there are textual examples where transitive verbs also appear in that context. Can Pixabaj (2007) provides examples of relative clauses in Uspantek where an A argument can be relativized using a transitive verb, which she claims is because there is no ambiguity between which argument is the agent and which is the patient. She also describes both transitive and AF/AP constructions as being possible in focus word contexts, even when there is the possibility of ambiguity. She additionally notes that there is a tendency to interpret the first element in the sentence as the agent, which tracks with the data and explanation presented here for Kaqchikel.

The facts for the remaining Eastern Mayan languages are less well-documented. Smith-Stark (1978: 171) describes AF/AP constructions in Poqomam as obligatory in wh questions with third person patients, optional in the relative clause and focus word contexts in which they appear, and optional if the agent is a negative indefinite pronoun and the patient is a third person. Although I have not located any statements about the possibility of transitive verbs where we would otherwise expect AF/AP constructions in Poqomchi’, there are some transitive examples where Brown (1978: 147) claims the preverbal agent is focused (although they could be topics). I have found no mention to date that suggests the use of AF/AP constructions in Q’eqchi’, Achi, Tektitek, or Awakatek are not obligatory.

Given the above statements and examples, it seems that it is in fact common in K’ichean, and possibly Eastern Mayan in general, for there to be variability in the distribution and use of AF (and other specialized constructions) and transitive constructions, both between different syntactic contexts and within a particular context. Specifically, for the majority of the languages discussed above, both AF/AP and transitive verbs can be used to relativize A arguments. However, there are also significant differences between Kaqchikel and other closely related languages. For example, while AF is optional in Kaqchikel with focus words, it is purportedly mandatory in the same context in closely related Tz’utujil. Also, while the use of AF is obligatory in A wh questions in Kaqchikel and Tz’utujil, AF appears to be optional when questioning A arguments in K’iche’ and Sakapultek. Because patterns in the use of AF are not uniform across Eastern Mayan, the explanation proposed here for Kaqchikel with respect to the divide between constructions that are introduced by a lexical NP and those that are not cannot apply in the same way even to other closely related languages. This complicates the identification of the underlying motivations for AF, but it is worth noting that this is perhaps not unusual; information and argument structure differences between even closely related Mayan languages has been identified in other work (see England and Martin 2003), and competition approaches allow the same pressures to lead to different grammaticalized outcomes in different languages (cf. e.g., Bickel 2007: 241; Dryer 1998; Haspelmath 1999).

It is also relevant to provide a brief summary of the facts for Western Mayan languages as they pertain to the observations made here. Although many Western Mayan languages do not have syntactic restrictions on ergative arguments, some still have AF constructions. The most prominent example is Tsotsil, for which Aissen (1999) has suggested that AF serves an ‘inverse’ function. In Tsotsil, AF is used when the agent is focused and the patient is more animate, definite, or individuated than the agent. When that is not the case, transitive verbs tend to be used. Although the characteristics of AF in Tsotsil differ in significant ways from AF in Kaqchikel, it is notable that both languages are more likely to allow transitive verbs when the subject is a clear agent.

There is also a significant literature on the syntax of focus in Yucatec (Bricker 1978; Gutiérrez-Bravo 2017; Gutiérrez-Bravo and Monforte 2011; Norcliffe 2009; Norcliffe and Jaeger 2016; Tonhauser 2007; Verhoeven and Skopeteas 2015; inter alia). Yucatec has an AF-type construction that appears when questioning, relativizing, or focusing the agent of a transitive verb, but transitive constructions are also common when relativizing A arguments (cf. Bricker 1978). Gutiérrez-Bravo and Monforte (2011: 261) state that “there is no structural unity between the contexts and conditions where AF is observed” and that “it is problematic to instead assume that AF [in Yucatec] is triggered by a specific syntactic configuration shared by agent focusing, interrogative fronting, and relativization”. Rather, they argue that AF is used in relative clauses along with passivization to disambiguate subject and object interpretations. While I argue against any direct avoidance of ambiguity in Section 4.2.2 as a motivating factor for the Kaqchikel data, the relevant point is that there is evidence from elsewhere in the family that information structure and other contextual factors have bearing on the use of AF, beyond the structural constraints of A-bar movement.

In addition to these data from Mayan languages, Tsunoda (1988: 43–45, 48) provides some evidence that it is perhaps not uncommon for there to be exceptions to syntactic restrictions on ergative arguments. His data come primarily from Pama-Nyungan languages, namely textual studies of Dyirbal and Warrungu. In Warrungu, coreferential NP deletion involving an ergative argument requires an antipassive in the vast majority of cases. However, coreferential NP deletions involving an ergative argument involve transitive verbs rather than antipassives about 5–10 % of the time (1988: 43). There are also a handful of examples in Dyirbal coordination and what Tsunoda calls “sentence-sequence” which exhibit the same type of variability (1988: 44). Although examples in these languages of transitive verbs in contexts where they are not expected are not nearly as extensive as those documented here for Kaqchikel, they do constitute evidence outside of Mayan for the availability of multiple constructions in contexts commonly involving restrictions on ergative arguments.

6 Conclusions

The data presented here provide novel evidence regarding the distribution of AF/AP constructions in Kaqchikel in the primary syntactic contexts in which they appear. Findings show that AF/AP constructions are consistently used in wh questions, existential indefinite contexts, and negative indefinite contexts. While AF/AP constructions appear in relative clauses, focus word constructions, and indefinite A contexts, these contexts also involve the use of transitive verbs more than half the time.[19] There is also evidence of age-grading where younger speakers are more likely than older speakers to use transitive verbs.

An important observation about this distribution in Kaqchikel is that focus contexts which are introduced by a specific lexical NP, particularly one that has already been established in the discourse, are likely to permit the use of transitive verbs. I suggest that this is a grammatical manifestation of general, cross-linguistic preferences related to both (a) processing economy, which favors rapid identification of the actor/agent role as well as the use of more frequent constructions (here transitive AVO), as well as (b) discourse pressures related to reference tracking and information structure where given arguments are more likely to be encoded as ergative NPs. Preverbal lexical NPs provide information as to whether that argument is a possible agent, regardless of the form of the verb, a tendency which has also been observed in several other Mayan languages. This set of general functional principles could motivate the distribution of constructions we see here, both between and within particular syntactic contexts. A competition account is particularly suited to these data, since the interaction of these factors create probabilistic tendencies rather than rules (although the patterns they create may grammaticalize into rules), and we see variation not only in which constructions are available but which are preferred across the six focus contexts investigated. The claim is that these discourse-level and semantic cues have shaped the syntactic possibilities in this domain in Kaqchikel. This type of processing approach is compatible both with analyses of Mayan syntax that would view this as an innovation, where ergative extraction restrictions were historically more uniform, as well as with views where ergative extraction restrictions originated in a more restricted set of contexts and then spread to other, similar contexts in different ways in different languages.

Finally, comparative evidence was provided which suggests that this type of variation in the use of AF/AP constructions is not uncommon in Eastern Mayan, and perhaps elsewhere as well. While it may be possible to make a generalized account for the Kaqchikel data, it is important to our broader understanding of AF to note that these constructions have grammaticalized in different ways in different languages, and serve different information-structural purposes (cf. Zavala [1997] on Akatek). Investigating broader similarities and differences requires collecting more comparable descriptive facts across Mayan. However, a level of caution should be exercised in investigating this phenomenon, since there is a documented tendency in multiple languages for the judgments provided in standard elicitation to contrast with use in other modes of communication, and to pay attention to the information-structural factors as well as the syntactic ones. I also encourage researchers working in this area to use multiple genres and methods (e.g., texts, picture elicitation, experimental designs, historical documentation) and investigate the potential for dialectal, age, diachronic, etc. variation with a variety of speakers. Only once we have a larger base of comparable data can we work towards a more complete explanation for the distribution of AF/AP constructions in Eastern Mayan and beyond.

Funding source: Bilinski Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2016–2017

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank William O’Grady and Kamil Deen for their input on the experimental design, as well as Mark Norris and William O’Grady who provided comments on an earlier version of this paper. Thank you also Bradley Rentz and Volker Gast for their assistance with the Bayesian statistical analysis, and to everyone who provided comments on presentations of this material at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and SSILA 2017. Finally, thank you to everyone in Guatemala who shared their knowledge with me, as well as to Igor, Kari, Angela, and Ambrocia for their hospitality. All remaining errors are my own.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by the Bilinski Dissertation Fellowship, 2016–2017.

-

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12188434.

References

Aissen, Judith. 1992. Topic and focus in Mayan. Language 68(1). 43–80. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1992.0017.Search in Google Scholar

Aissen, Judith. 1999. Agent focus and inverse in Tzotzil. Language 75(3). 451–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/417057.Search in Google Scholar

Aissen, Judith. 2011. On the syntax of agent focus in K’iche’. In Kirill Shklovsky, Pedro Mateo Pedro & Jessica Coon (eds.), Proceedings of formal approaches to Mayan linguistics (FAMLi), 1–16. (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 63). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Aissen, Judith. 2017a. Correlates of ergativity in Mayan. In Jessica Coon, Diane Massam & Lisa Travis (eds.), The Oxford handbook of ergativity, 737–758. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198739371.013.30Search in Google Scholar

Aissen, Judith. 2017b. Information structure in Mayan. In Judith Aissen, Nora England & Roberto Zavala Maldonado (eds.), The Mayan languages, 293–324. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315192345-11Search in Google Scholar

Alday, Phillip, Matthias Schlesewsky & Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky. 2014. Towards a computational model of actor-based language comprehension. Neuroinformatics 12. 143–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12021-013-9198-x.Search in Google Scholar

Ayres, Glenn. 1983. The antipassive voice in Ixil. International Journal of American Linguistics 49(1). 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1086/465763.Search in Google Scholar

Barrett, Edward. 1999. A grammar of Sipakapense Maya. Austin: University of Texas Austin dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Elizabeth & Brian MacWhinney. 1982. A functionalist approach to grammar. In Eric Wanner & Lila Gleitman (eds.), Language acquisition: The state of the art, 173–218. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Elizabeth, Sandra McNew, Brian MacWhinney, Antonella Devescovi & Stan Smith. 1982. Functional constraints on sentence processing: A cross-linguistic study. Cognition 11. 245–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(82)90017-8.Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Balthasar. 2007. Typology in the 21st century: Major current developments. Linguistic Typology 11. 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1515/LINGTY.2007.018.Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Balthasar, Alena Witzlack-Makarevich, Kamal K. Choudhary, Matthias Schlesewsky & Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky. 2015. The neurophysiology of language processing shapes the evolution of grammar: Evidence from case marking. PLoS One 10(8). e0132819. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132819.Search in Google Scholar

Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, Ina & Matthias Schlesewsky. 2009. The role of prominence information in the real-time comprehension of transitive constructions: A cross-linguistic approach. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(1). 19–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00099.x.Search in Google Scholar

Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, Ina & Matthias Schlesewsky. 2014. Competition in argument interpretation: Evidence from the neurobiology of language. In Brian MacWhinney, Andrej Malchukov & Edith Moravcisk (eds.), Competing motivations in grammar and usage, 107–126. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198709848.003.0007Search in Google Scholar

Bresnan, Joan & Judith Aissen. 2002. Optimality and functionality: Objections and refutations. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 20. 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014222605182.10.1023/A:1014222605182Search in Google Scholar

Bricker, Victoria. 1978. Wh-questions, relativization and clefting in Yucatec Maya. In Laura Martin (ed.), Papers in Mayan linguistics, 109–139. Columbia, MI: Lucas Brothers.Search in Google Scholar

Broadwell, George Aaron. 2000. Word order and markedness in Kaqchikel. In Miriam Butt & Tracy Holloway King (eds.), Proceedings of the LFG00 conference, 1–19. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Linda Kay. 1978. Word formation in Pocomchi (Mayan). Stanford, CA: Stanford University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, usage and cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511750526Search in Google Scholar

Campana, Mark. 1992. A movement theory of ergativity. Montreal: McGill University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Lyle. 2000. Valency-changing derivations in K’iche’. In Robert M. W. Dixon & Alexandra Aikhenvald (eds.), Changing valency: Case studies in transitivity, 223–281. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511627750.008Search in Google Scholar

Can Pixabaj, Telma. 2007. Jkemiik yoloj li uspanteko [Uspantek grammar]. Guatemala: Cholsamaj. Oxlajuuj Keej Maya’ Ajtz’iib’.Search in Google Scholar

Clark, Eve. 1978. Strategies for communicating. Child Development 49(4). 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1978.tb04063.x.Search in Google Scholar

Clemens, Lauren Eby. 2013. Kaqchikel SVO: V2 in a V1 language. In Michael Kenstowicz (ed.), Studies in Kaqchikel grammar, 1–23. (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Clemens, Lauren Eby, Jessica Coon, Pedro Mateo Pedro, Adam Milton Morgan, Maria Polinsky, Gabrielle Tandet & Matthew Wagers. 2015. Ergativity and the complexity of extraction: A view from Mayan. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33(2). 417–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9260-x.Search in Google Scholar

Coon, Jessica. 2016. Mayan morphosyntax. Language and Linguistics Compass [special issue on Mayan linguistics] 10(10). 515–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12149.Search in Google Scholar

Coon, Jessica, Nico Baier & Theodore Levin. 2019. Mayan agent focus and the ergative extraction constraint: Facts and fictions revisited. Ms: McGill University.Search in Google Scholar

Coon, Jessica, Pedro Mateo Pedro & Omer Preminger. 2014. The role of case in A-bar extraction asymmetries: Evidence from Mayan. Linguistic Variation 14. 179–242. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.14.2.01coo.Search in Google Scholar

Craig, Collette Grinevald. 1977. The structure of Jacaltec. Austin: University of Texas Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dayley, Jon P. 1981. Voice and ergativity in Mayan languages. Journal of Mayan Linguistics 2. 3–82.Search in Google Scholar

Dayley, Jon P. 1985. Tzutujil grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar