Abstract

Laboratory findings provide essential information for assessing the state of health. Two concepts for the classification and evaluation of the findings are central: reference intervals (RI) and clinical decision limits (CDL), which also include therapeutic target limits. The IFCC (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine) with the Committee for Reference Intervals (C-RIDL) and the working group on the Global Reference Interval Database (TF-GRID) presented concepts and their sustainability with a focus on reference limits at EuroMedLab Brussels 2025. Sustainability for RIs and CDLs represents a new concept that has prerequisites like a data infrastructure and a quality and information framework. Not all of these prerequisites have been fully characterized yet, but the essential aspects are addressed in this article. Standardization with metrological traceability or, where not otherwise possible, harmonization forms the basis for sustainability of RIs and CDLs. Sustainable RIs and CDLs enhance the use and value of electronic patient records and help to establish cumulative reports.

Introduction

The interpretation of laboratory test results is fundamental to clinical decision-making, yet it faces significant challenges due to the lack of standardized reference intervals (RIs) and clinical decision limits (CDLs). Traditionally, different laboratories have employed different RIs even for identical test procedures. This inconsistency hampers comparability across institutions and complicates longitudinal patient care in systems reliant on electronic health records. Recently, advancements in statistical methodologies, such as indirect methods utilizing large datasets from mixed populations, have enabled laboratories to estimate more consistent RIs. This document explores the concept of sustainable RIs and CDLs frameworks designed to enhance reliability, comparability, and clinical utility through standardization, harmonization, and continuous quality assurance. By integrating data from multicenter studies and applying robust analytical methods, sustainable RIs and CDLs aim to support evidence-based medical practices and improve patient outcomes.

Sustainable reference intervals

One of the drivers in the further development of reference intervals (RIs) is the increasing use of electronic patient records, especially when patients’ data are to be compared across different laboratories or even presented cumulatively in the patient file, the problem arises that neither RIs nor decision limits are established with sufficient standardization. Thus, laboratories often use different RIs even for the same test procedures and analysis systems. In addition, for many years the dogma was that different analysis systems make it impossible to use common RIs. Ultimately, it was precisely this dogma that led to the development of statistical methods that allow each laboratory to establish its own RIs. These so-called “indirect methods” use the measurement results of a mixed population (healthy and diseased), which can be obtained, for example, from laboratory information systems, to estimate RIs. The spread of these methods indicated that estimates across different sites produced sufficiently similar RIs for several analytes. At this point, it should be noted that the RIs discussed here are “classic” RIs (based on population data) and should not be mixed up with personalized reference intervals [1] or multivariate reference intervals [2].

These findings have resulted in various studies: In Germany, the PEDREF [3] network, together with the DGKL section on RIs (German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine), has summarized data from various university hospitals and tested them with regard to the differences between the laboratories, emphasizing that only one analysis system (manufacturer) was used. The agreement of the results was impressive and allowed a joint evaluation of the data [4], 5]. The newly estimated reference limits, like those from other working groups, were referred to as so-called “common reference limits” and can already be used practically in the clinical routine on the pedref.org website [3]. However, it should be noted that “common RIs” are not readily transferable even when using the same measurement methodology and instruments, as RIs are dependent on pre- or extraanalytical conditions [6] leading to the necessity to validate them and control these conditions. For instance, the reference intervals for GGT collected in Germany and Greece differ, despite the use of the same Abbott systems [7]. Variations in dietary habits are suggested as a potential cause. Another study, utilizing Nigeria as a case study, demonstrated that the reference intervals for hemoglobin collected in North America and Europe are not applicable to African conditions [8], indicating ethnic disparities. Nevertheless, even within a sufficient well-defined population, such as Germany, numerous known extra-analytical factors can influence the results, including the body position (lying or sitting) during blood collection.

The work on the estimation of common RIs using indirect methods was promoted by the CALIPER group of the CSCC (Canadian Society for Clinical Chemistry), which had previously concentrated on direct studies on RI estimation. The CALIPER Group had conducted comprehensive direct studies on RIs in children in Canada and published them. Based on samples from more than 15,000 healthy children and adolescents, CALIPER was able to determine age- and gender-specific pediatric RIs for over 200 biochemical markers [7]. Based on the results of the direct studies, which are still considered the gold standard today [8], the working group collected additional data from laboratories for analysis using indirect methods. The first evaluations were carried out with the TML (Truncated Minimum Likelihood) algorithm [9], which was then replaced by the refineR algorithm [10]. In parallel with the efforts to improve the pediatric RIs, the CSCC has focused on the harmonization of RIs for adults by using the indirect methods of benchmark estimation in a “big data analysis approach”. In a study published in 2023 in Clinical Chemistry, this method for derivation of common RIs for 16 analytes for adults was presented [11]. This approach integrated data from nine laboratories across Canada with different analysis platforms using the refineR algorithm. As part of the study, harmonized RIs were successfully established for analytes such as AP, albumin, chloride, LDH, magnesium, phosphate, potassium and total protein, which met the verification criteria of the various laboratories and manufacturers. However, some analytes also revealed the limits of the approach and required further investigations due to discrepancies in verification or excessively wide reference ranges (particularly for methods based on immunoassays). At the IFCC Symposium in Brussels [12], the CALIPER group presented the importance of integrating pediatric RIs with the newly derived harmonized RIs for adults as a crucial step toward creating a uniform and evidence-based framework for interpreting laboratory analyses in Canada [12].

With appropriate standardization or a method-related approach, cross-laboratory RI (common RIs) can be established. Naturally, this approach has its limitations; therefore, in the absence of standardization, several working groups pursued harmonization. A prominent example is the work of the Committee for Common Reference Intervals in Australia (AACB CCRI), which identified the electronic health record (eHMR) and the need to integrate results from a single patient across different pathology providers irrespective of method, units, or RIs as key drivers of harmonization. To achieve harmonized laboratory reporting and reduce confusion for both physicians and patients, the Australian government launched the Pathology Units and Terminology Standardization (PUTS) project in 2011. This initiative successfully harmonized RIs for more than 18 analytes, with ongoing developments accessible via the RCPA website [13].

These various studies led to the question of whether sustainable RIs can be established. Sustainable RIs refer to the estimation of RIs that incorporate comprehensive, clinically relevant stratification and are supplemented with information such as the analytical method, with the ultimate aim of promoting long-term reliability and consistency in the interpretation of laboratory test results and the diagnoses derived from them. Concretely, this requires that, in addition to the type of specimen analyzed, the measurement method must also be reported in order to allow comparability or to explicitly highlight non-comparability. The concept further requires sufficient consideration of factors such as age, sex, where needed ethnic background, and geographical region. Moreover, uniform terminology is indispensable within this framework. Sustainable RIs account for these variables and may include the definition of highly specific intervals for distinct patient groups. It must be emphasized that if two instruments or methods in different laboratories are not standardized or harmonized, then their RIs should not be considered interchangeable. As mentioned above, extra-analytical variables could affect RIs; thus, a clear definition and comprehensive control of these variables is a mandatory prerequisite. Therefore, harmonization or standardization should not be limited to the analytical phase but should also extend to the pre- or extra-analytical phase. The establishment of sustainable RIs must therefore rely on multicenter studies, employing either direct or indirect methods, and subsequently be subjected to independent external validation.

Sustainable decision limits

The concept and the definition of RIs should be clearly kept separate from clinical decision limits (CDLs) which are limits or cut-off values that are determined by clinical studies to be associated with a specific clinical risk or outcome [14]. As RIs are derived from the unaffected (general) population and based on the 95 % central interval of the reference distribution, CDLs are derived from affected patient groups and typically based on clinical outcome studies. The statistical methods (e.g. ROC) thus try to identify clinical subgroups with the best sensitivity and specificity. Sustainable CDLs should be therefore based upon clinically relevant risk stratification with respect to the clinical question and need to explicitly reflect the analytical method. Compared to RIs it seems to be more complicated to establish sustainability for CDLs since treatment options (new pharmaceuticals) usually change faster than the characteristics of a reference population. In addition, clinical studies might identify new risk classes leading to new decision limits. A prominent example where the CDLs changed over time is LDL-cholesterol [15]: In 1988, if individuals continued to have LDL-cholesterol ≥ 130 mg/dL, pharmacologic intervention was recommended. In 1993 the LDL-cholesterol treatment target was decreased from<130 mg/dL to<100 mg/dL. In 2004 an optimal treatment goal of LDL-cholesterol < 70 mg/dL set the decision limit for patients with coronary heart disease and further risk factors like diabetes. The decision limit and the target of <70 mg/dL remained the clinical standard for over a decade, but were lowered to<55 mg/dL respectively<40 mg/dL (optimal) in 2019 and 2022 (ESC/EAS and ACC consensus guidelines) [15].

A general problem that occurs in the sustainability of CDLs is the transferability and is well known from RIs. Different clinical populations, the lack of information about the methods and their quality used in clinical studies might hinder direct transference. This has been shown for cardiac troponins where the 99th percentile upper reference limit of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) from a healthy reference population is used as a decision limit for diagnosing acute myocardial infarction. Current thresholds of hs-cTnT (Roche) and hs-cTnI (Abbott) are 14 and 26 ng/L, respectively. In an independent direct study with a healthy reference population the upper limit of hs-cTnT and hs-cTnI were 15 and 13 ng/L, respectively [16] showing that transferability is highly dependent on the population studied and the measurement method used. Quite often decision limits are used as universal limits without addressing the problems of transferability. In addition, the age dependency, which has already led to continuous intervals in the case of RIs, is often ignored in the case of CDLs.

Since the electronic health record is one of the key drivers for sustainable reference intervals and decision limits, the zlog concept was developed by the DGKL, offering a solution for standardizing results with respect to their reference limits [17]. This concept relies on method-specific, high-quality RIs but can then help to present results between laboratories with different measurement technologies in a comparable way, even in a cumulative report. In the context of the standardization of guide limits discussed herein, the zlog transformation may be applied not only to individual measurements in patients but also to decision limits to facilitate comparability across different laboratories.

Conclusions

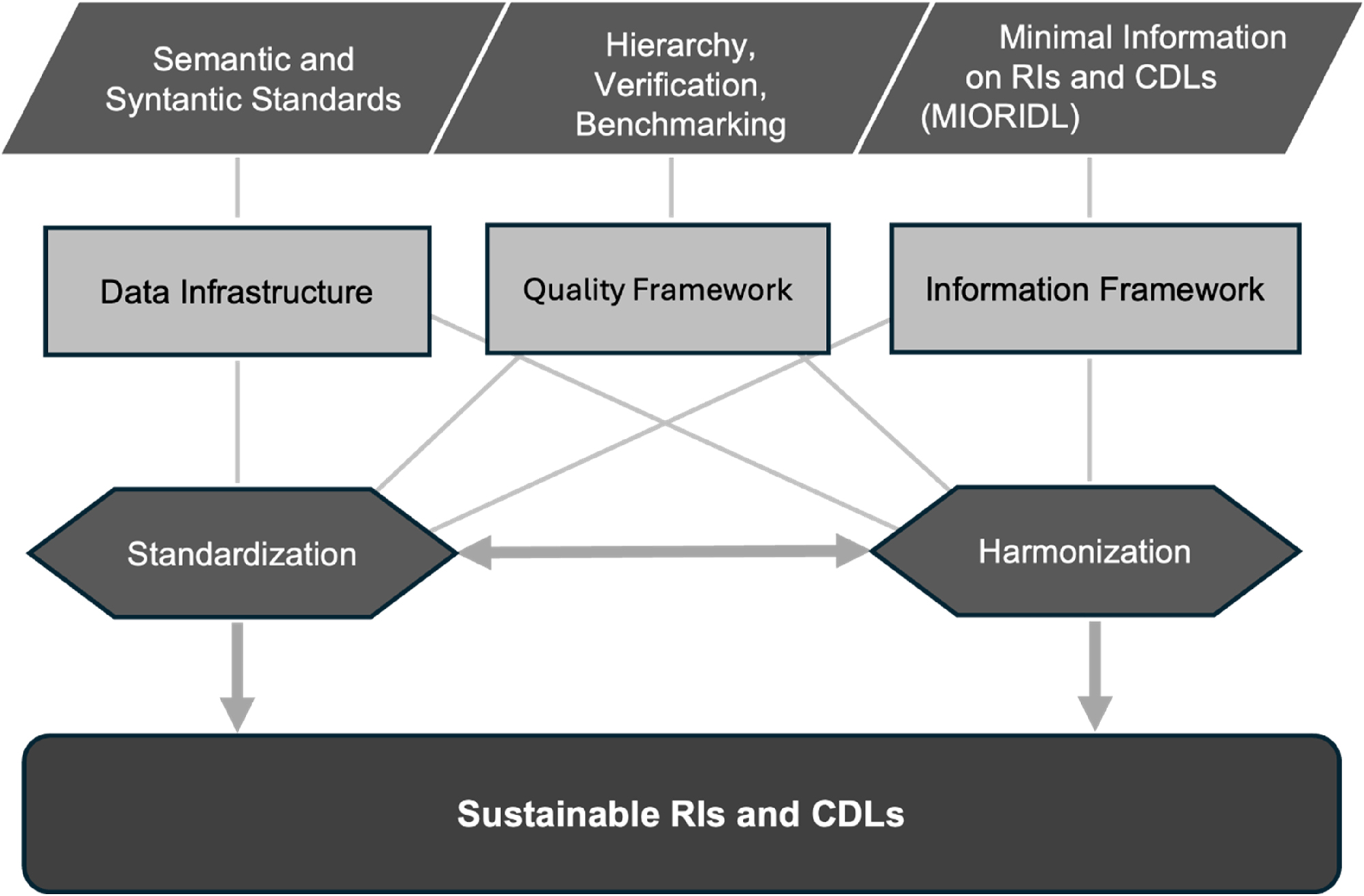

Taken together, the concept of sustainable RIs or CDLs requires basic prerequisites illustrated in Figure 1:

Comparable and reliable measurement results across different laboratories and over time. This goal should primarily be achieved through standardization and, where this is not possible, through harmonization. Whereas standardization ensures traceability to the SI, harmonization ensures traceability to a reference system agreed upon by convention [17].

Relevant information on the reference limits must be defined. The concept of minimum information on RIs (MIORIDL) needs to be established.

Data infrastructure with syntactic and semantic standards for reports (e.g. SNOMED CT, LOINC and UCUM in HL7/FHIR [18]).

A quality framework is needed that classifies the different types of RIs in terms of their significance for the patient. A hierarchy for RIs and in the second step for decision limits needs to be developed.

Key pillars and supporting structures enabling sustainable RIs and CDLs.

If these requirements are met, they will result in sustainable and transferable RIs and CDLs. Standardization is certainly the most important requirement, but also the most difficult to implement. So far, metrological traceability is achieved for a number of relevant analytes, in the JCTLM database are listed more than 160 measurands [19], but this does not necessarily mean that all laboratories and all manufacturers make use of the corresponding reference materials or reference measurement procedures. Besides that, large laboratories offer a substantially broader spectrum of measurands for which metrological traceability has not yet been achieved. Since relevant decisions are made on the basis of reference or decision limits, it is also important for clinicians to know whether the limit is a reference limit or a clinical decision limit and whether these are sustainable and therefore transferable. This information should therefore be included in the reports and clearly identifiable.

Ultimately, sustainable RIs or CDLs are a consequence of standardization and harmonization under constant quality assurance.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: LLM was used to improve language (Apple Intelligence).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors (Streichert, Coskun, Özçürümez) state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Coskun, A, Sandberg, S, Unsal, I, Cavusoglu, C, Serteser, M, Kilercik, M, et al.. Personalized reference intervals in laboratory medicine: a new model based on within-subject biological variation. Clin Chem 2021;67:374–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa233.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Coskun, A, Weninger, J, Canbay, A, Özçürümez, MK. From metabolic profiles to clinical interpretation: multivariate approaches to population-based and personalized reference intervals and reference change values. Clin Chem Lab Med 2025;63:2397–405. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2025-0786.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Zierk, J. PEDREF; a collaborative pediatric reference intervals initiative of the department of pediatrics, university hospital erlangen and our collaborators supported by the DGKL’s division on decision limits/reference data. [cited 2025 14.09.2025]; Available from: https://www.pedref.org/index.html.Search in Google Scholar

4. Zierk, J, Arzideh, F, Rechenauer, T, Haeckel, R, Rascher, W, Metzler, M, et al.. Age- and sex-specific dynamics in 22 hematologic and biochemical analytes from birth to adolescence. Clin Chem 2015;61:964–73. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.239731.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Zierk, J, Arzideh, F, Haeckel, R, Cario, H, Frühwald, MC, Groß, H-J, et al.. Pediatric reference intervals for alkaline phosphatase. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:102–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0318.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Haeckel, R, Wosniok, W, Arzideh, F. A plea for intra-laboratory reference limits. Part 1. General considerations and concepts for determination. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007;45:1033–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2007.249.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Adeli, K. CALIPER – canadian laboratory initiative on pediatric reference intervals. [cited 2025 14.09.2025]; Available from: https://caliperproject.ca.Search in Google Scholar

8. CLSI, defining, establishing, and verifying reference intervals in the clinical laboratory; approved guideline –third edition. CLSI document EP28-A3c. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

9. Arzideh, F, Wosniok, W, Gurr, E, Hinsch, W, Schumann, G, Weinstock, N, et al.. A plea for intra-laboratory reference limits. Part 2. A bimodal retrospective concept for determining reference limits from intra-laboratory databases demonstrated by catalytic activity concentrations of enzymes. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007;45:1043–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2007.250.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ammer, T, Schützenmeister, A, Prokosch, HU, Rauh, M, Rank, CM, Zierk, J, et al.. refineR: a novel algorithm for reference interval estimation from real-world data. Sci Rep 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95301-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Bohn, MK, Schneider, R, Jung, B, Adeli, K. Pediatric reference interval verification for 16 biochemical markers on the alinity ci system in the CALIPER cohort of healthy children and adolescents. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:2033–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0256.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Zierk, J, Adeli, K, Sheldon, J, Streichert, T. SYMPOSIUM 5 - Sustainable Reference intervals and Clinical Decision Limits: Towards Standardization & Harmonization. Clin Chem Lab Meds 2025;63:s48–50.10.1515/cclm-2025-8021Search in Google Scholar

13. Australia R-RCo.Pi. Harmonised reference intervals for chemical pathology. [cited 2025 15.9.2025]; Available from: https://www.rcpa.edu.au/Manuals/RCPA-Manual/General-Information/IG/Table-6-Harmonised-reference-intervals-for-chem.Search in Google Scholar

14. Ozarda, Y, Sikaris, K, Streichert, T, Macri, J. Distinguishing reference intervals and clinical decision limits – a review by the IFCC committee on reference intervals and decision limits. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2018;55:420–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2018.1482256.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Jones, JE, Tang, KS, Barseghian, A, Wong, ND. Evolution of more aggressive LDL-cholesterol targets and therapies for cardiovascular disease prevention. J Clin Med 2023;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12237432.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Kimenai, DM, Henry, RM, van der Kallen, CJ, Dagnelie, PC, Schram, MT, Stehouwer, CD, et al.. Direct comparison of clinical decision limits for cardiac troponin T and I. Heart 2016;102:610–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308917.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Vesper, HW, Myers, GL, Miller, WG. Current practices and challenges in the standardization and harmonization of clinical laboratory tests. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:907S–12S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.110387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Bietenbeck, A, Streichert, T. Preparing laboratories for interconnected health care. Diagnostics 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081487.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Jones, G, Delatour, V, Badrick, T. Successes and challenges delivering higher order references for laboratory medicine. Database newsletter 2025. [cited 2025 18.09.2025]; Available from: https://jctlm.org.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Entering a new era of laboratory data processing and interpretation

- Articles

- Sustainable reference intervals and decision limits

- An update to reflimR: strengthening transparent reference interval verification

- Intuitive web tools for reference interval estimation: goCrunch and ReferenceRangeR

- Automated age and sex partitioning of reference intervals based on routine laboratory data

- Using zlog in spider charts for fast diagnosis recognition

- Using large language models for therapeutic drug monitoring reporting – a proof-of-concept

- EU AI Act: what could AI literacy mean for medical laboratories? – Opinion Paper on behalf of the Section Digital Competence and AI of the German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (DGKL)

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Entering a new era of laboratory data processing and interpretation

- Articles

- Sustainable reference intervals and decision limits

- An update to reflimR: strengthening transparent reference interval verification

- Intuitive web tools for reference interval estimation: goCrunch and ReferenceRangeR

- Automated age and sex partitioning of reference intervals based on routine laboratory data

- Using zlog in spider charts for fast diagnosis recognition

- Using large language models for therapeutic drug monitoring reporting – a proof-of-concept

- EU AI Act: what could AI literacy mean for medical laboratories? – Opinion Paper on behalf of the Section Digital Competence and AI of the German Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (DGKL)

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment