Abstract

Objectives

ddPCR is a tool improving the detection and clinical management of critical infections. This prospective study verified ddPCR’s application value in pathogen detection for abdominal sepsis.

Methods

It was conducted in the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from January 2021 to December 2022. And 164 patients with abdominal sepsis were enrolled. Strengths and weaknesses of abdominal sepsis pathogen detection via drainage fluid culture versus ddPCR were analyzed.

Results

In abdominal sepsis patients, 86 % of them detected pathogens using ddPCR, compared with 71.3 % using traditional methods. 208 bacterial strains were found by ddPCR, including 58.7 % (122/208) Gram-negative and 41.3 % (86/208) Gram-positive bacteria. 182 strains of bacteria (56.6 % Gram-negative, 43.4 % Gram-positive) and 15 strains of fungi were detected by the conventional method. Notably, 67.7 % of the patients were positive for both ddPCR and culture, and 10.4 % were negative. Using culture as the gold standard, for infections with two or more pathogens, ddPCR demonstrated 95.31 % sensitivity and 98 % specificity. Reporting time of the drainage fluid culture (40.85 ± 1.61 h) was significantly longer than ddPCR (6.86 ± 0.12 h) (p<0.001). A total of 52 patients were identified as carriers of drug-resistant genes through ddPCR analysis, of which 39 had their anti-infection treatment plans modified during the course of therapy.

Conclusions

ddPCR is a rapid and sensitive tool for the etiological detection of abdominal sepsis. However, it currently detects only specific pathogens and cannot differentiate between viable microorganisms and those that have already undergone apoptosis.

Introduction

In intraabdominal infection, pathogens enter the abdominal cavity through various ways [1]. Severe intraabdominal infection often leads to sepsis and septic shock, which eventually results in multiple organ dysfunction and high mortality [2]. One of the key factors in the management and treatment of complex intraabdominal infection is the early use of appropriate antibiotics [3]. In patients with intraabdominal infection, the rapid identification of pathogens is conducive to the implementation of effective pathogen-targeted therapy. Conventional pathogen detection in patients with abdominal sepsis is performed by bacterial culture, which has obvious disadvantages. It is low-sensitive (especially for slow-growing or finicky microorganisms and fungi) and time-consuming [1]. Thus, a rapid and sensitive diagnostic method for clinical pathogen identification in abdominal sepsis is urgently needed.

Multiplex droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is a recently developed molecular technique for the precise quantification of target nucleic acids in samples by counting nucleic acid molecules encapsulated in discrete, specific volume droplets [4]. ddPCR has the characteristics of high sensitivity, high specificity, and wide analytical range, which has been used in many fields such as non-invasive prenatal testing. In critical care, ddPCR is considered a tool that can improve the diagnosis and clinical management of severe infections [5]. However, there is still a lack of studies that have verified the diagnostic value of ddPCR for the detection of pathogens in abdominal sepsis in clinical practice.

This prospective study investigated the microbiological diagnostic ability of ddPCR in patients with abdominal sepsis. We evaluated and compared strengths and weaknesses of drainage fluid culture and ddPCR.

Materials and methods

Patient enrollment

In this prospective study, we conducted an initial sample size calculation with a statistical power of 0.8 and a significance level (α) of 0.05. Subsequently, we enrolled patients diagnosed with abdominal sepsis in the Department of Intensive Care Medicine at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from January 2021 to December 2022. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (N0.2022-K132).

Abdominal sepsis was defined as infection with a source in the abdominal cavity meeting the Sepsis-3 diagnostic criteria published jointly by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society for Intensive Care Medicine [6].

The following exclusion criteria were applied: patients without appropriate abdominal effusion for bacterial culture and ddPCR; patients<18 years old or>95 years old; patients expected to die within 24 h; patients in hospital for more than seven days due to abdominal infection prior to their ICU admission; patients diagnosed with hospital-acquired infection prior to their ICU admission; and patients without a signed informed consent form.

Data collection

The clinical data of the enrolled participants included demographic data such as gender and age, as well as previous medical history, APACHE II score, and SOFA score based on laboratory tests performed in ICU. Abdominal fluid was collected via abdominal a drainage tube, and sampling was performed for bacterial Gram staining, bacterial isolation by plate streaking, culture in serum-agar plate medium at 37 °C, drug sensitivity detection, and ddPCR. We employed 28-day survival as the endpoint of this study, data of the ICU stay of the patients were also collected.

DNA extraction and ddPCR testing

The following procedures were implemented for sample preparation. The abdominal fluid was shaken for proper mixing. Then, a 5 mL sample was collected into a 10/15 mL centrifuge tube, followed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Further, the supernatant was discarded to the remaining 1 mL, and the remaining supernatant and precipitates were transferred into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube for voracious mixing. Next, 200 μL samples were collected and transferred into 1.5 mL tubes. Then, 800 μL of digestive fluid was added, and the samples were incubated at 56° for 10 min. Following incubation, centrifuge at 1,000 rpm for 5 min to collect the supernatant. After collecting the supernatant, add an appropriate amount of Auto-Pure 32A automated magnetic bead nucleic acid extraction solution (Hangzhou Ao Sheng, Hangzhou, China), shake thoroughly, and incubate at 37 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, place the mixture on the magnetic stand of the Auto-Pure 32A, add 300 μL of washing solution, and perform two washes. Finally, add 50 μL of TE buffer for elution. Retain 2 mL of the DNA supernatant and store it in a −20 °C freezer for subsequent ddPCR analysis.

According to the study by Wu et al. [5], the 2019 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Intra-abdominal Infections, along with the results of our hospital’s previous pathogen surveillance and antibiotic susceptibility testing, led to the design of a specific multiplex ddPCR identification panel. This panel is intended to identify five Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii complex), four Gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus), one fungus (Candidiins), and four resistance genes (blaKPC, VanA + VanM, mecA, Oxa-48). Subsequently, the Pilot Gene Droplet Digital PCR System, a five-channel fluorescent ddPCR system (Pilot Gene Technology Company, Hangzhou, China), was employed to detect pathogens and resistance genes according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai). In accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations, a ddPCR reaction mixture with a final volume of 20 μL was prepared, consisting of 2.0 μL DNA, 1 × ddPCR probe supermix (BioRad, City, USA), 800 nM specific primers, 250 nM probes, and DNase-free water. The mixture was then transferred to a droplet generator (AD16, Pilot Gene Tech.) to produce approximately 20,000 water-in-oil emulsion droplets within the chip. These droplets were subsequently loaded into a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) for amplification, which involved an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing/extension at 62 °C for 1 min, and enzyme inactivation at 98 °C for 10 min, concluding with a stabilization step at 12 °C for 30 min. After amplification, the droplets were measured using a reader, and the data were analyzed with Bio-Rad Quanta Soft Analysis Pro software. Based on previous test data from our institution, a copy number greater than 45 copies/mL is defined as positive.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software. Figures were created by RStudio 2022-09-06 and Excel 2019. Continuous variables were tested by S-W test for data distribution. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and continuous variables without normal distribution were expressed as median and inter-quartile range. Categorical variables were represented as count and percentage. Student’s t-test was applied for comparison of continuous variables with normal distribution, and Mann-Whitney U-test was implemented for comparison of continuous variables without normal distribution. Chi-square test was employed for comparison of categorical variables. A 2 × 2 contingency table was established to determine the positive percent agreement (PPA), negative percent agreement (NPA), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). All statistical analyses were performed at an absolute value of 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test were used for the PPA comparison as unpaired between-group samples.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the included 164 patients

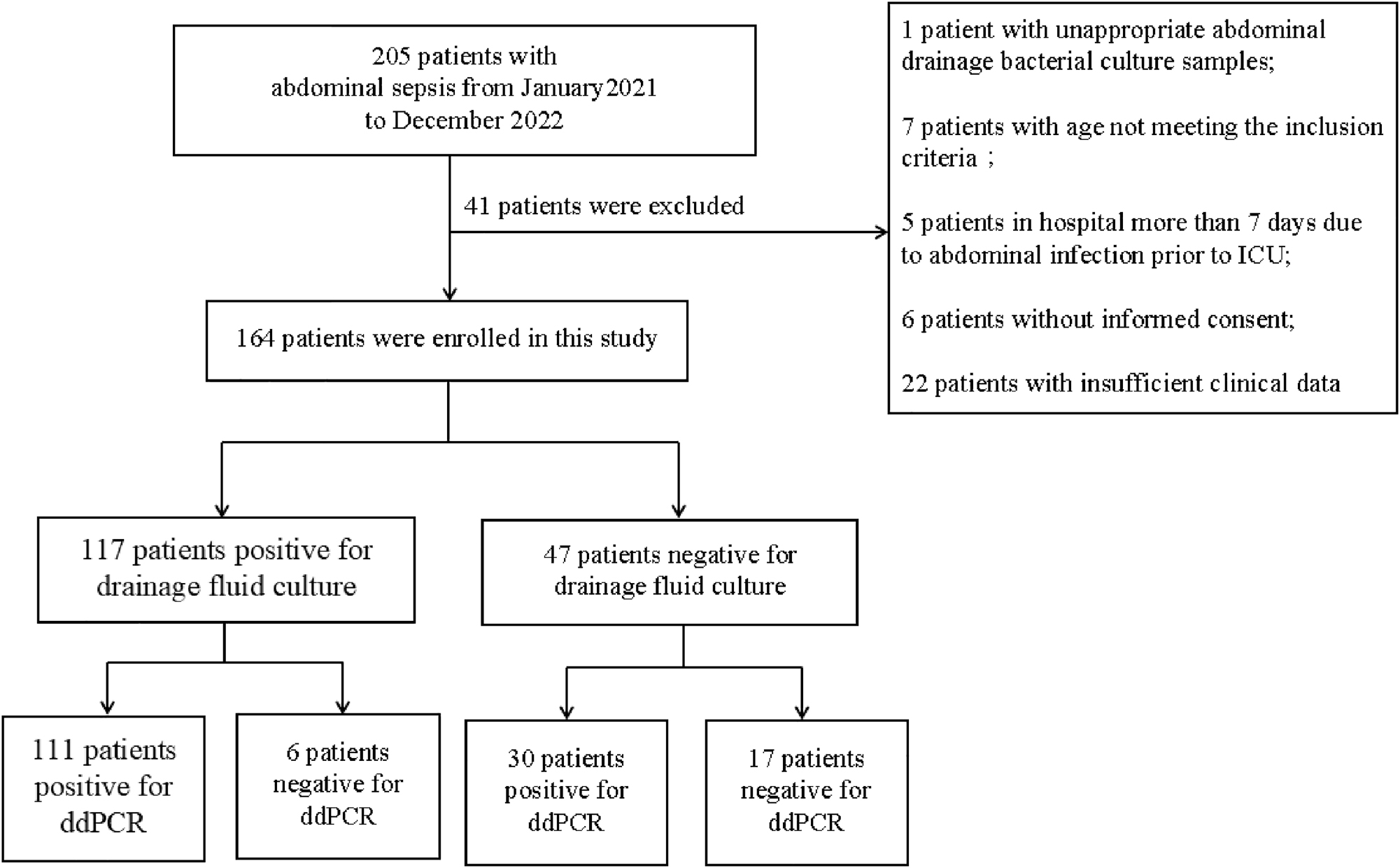

A total number of 205 patients with abdominal sepsis were admitted during the study, including one patient with inappropriate abdominal drainage bacterial culture samples, seven patients with age not meeting the inclusion criteria, five patients in hospital more than seven days due to abdominal infection prior to ICU, six patients without informed consent, and 22 patients with insufficient clinical data (19 patients with incomplete laboratory data and three patients with unknown clinical outcomes). Eventually, 164 patients were enrolled in this study (Figure 1). A total number of 164 ddPCR samples, 228 drainage smear samples, and 490 (245*2) drainage culture samples were collected from these patients.

Patient selection flowchart.

The mean age of the 164 patients, 82 males (50 %) and 82 females (50 %), with abdominal septic shock was 69.7 (24.091.0) years. Of them, 69 (42.1 %) patients were with history of cardiovascular disease, 27 (16.5 %) with diabetes, and 19 (11.6 %) with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Gastrointestinal perforation, cholangitis, and abdominal infection after surgery were the main causes of septic shock accounting for 18.3 % (30), 34.8 % (57), and 47.0 % (77) cases, respectively. Fifty-one (31.1 %) patients developed shock and received vasopressors during ICU, and 26 (15.9 %) patients died within 28 days (Table 1).

General information of the enrolled 164 patients.

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

| Age, year | 69.7 (24.091.0) |

| Male | 82 (50.0 %) |

| SOFA score | 9.73 (3,12) |

|

|

|

| Pathogen | |

|

|

|

| Biliary tract disease | 57 (34.8 %) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 30 (18.3 %) |

| Abdominal infection after surgery | 77 (47.0 %) |

|

|

|

| Past medical history | |

|

|

|

| Cardiovascular disease Diabetes |

69 (42.1 %) 27 (16.5 %) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 19 (11.6 %) |

| Cirrhosis | 15 (9.2 %) |

| Malignancy | 14 (8.5 %) |

| Neurological disorders | 9 (5.5 %) |

| Chronic renal failure | 6 (3.7 %) |

|

|

|

| Outcomes | |

|

|

|

| Shock | 51 (31.1 %) |

| Death within 28 days | 26 (15.9 %) |

Distribution of pathogens and the infection types in the patients

Pathogen detection results in ddPCR

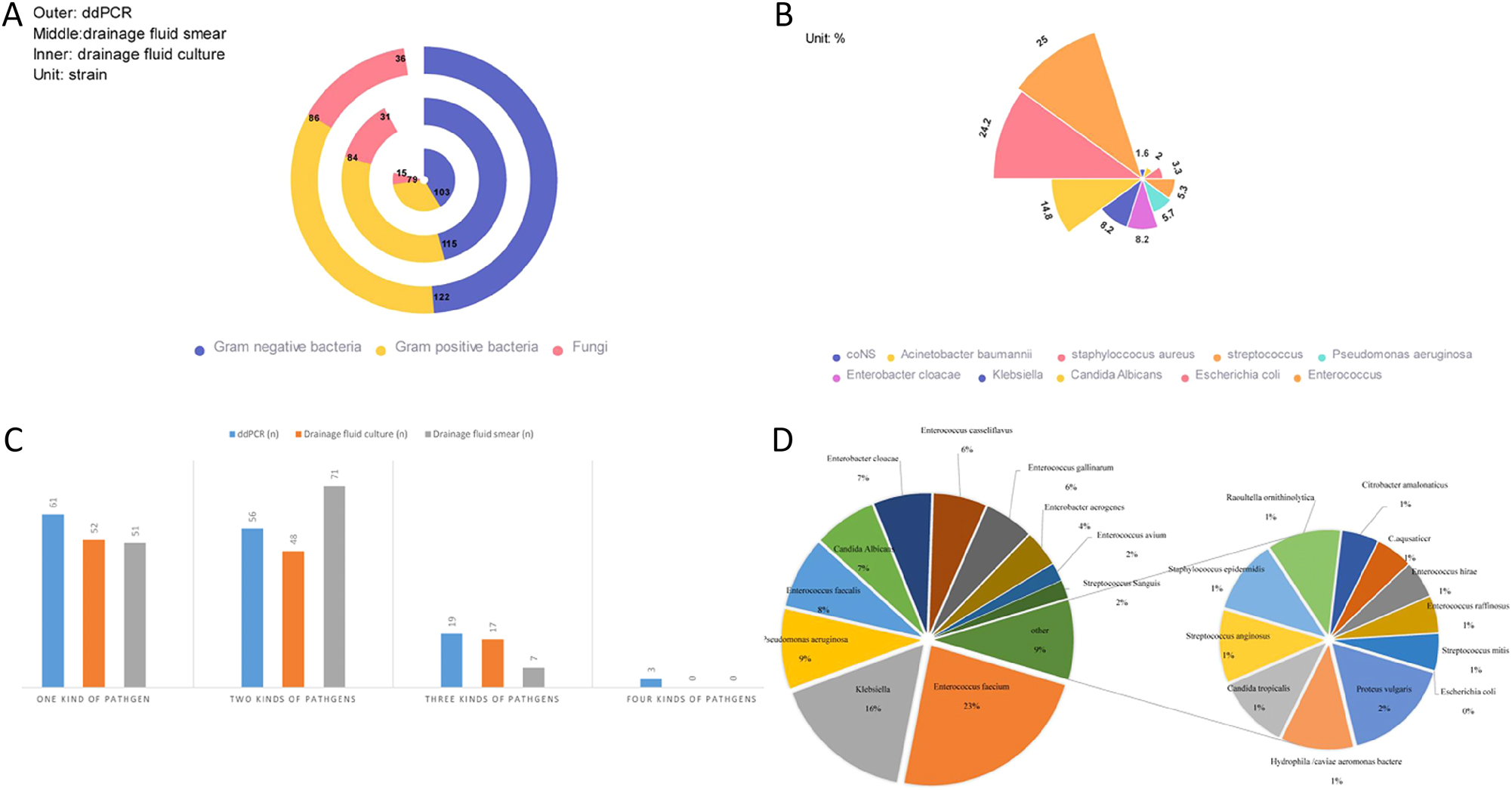

ddPCR was performed using drainage fluid from 164 patients with abdominal sepsis. Of them, 141 patients were ddPCR-positive, with a positive detection rate of 86 % (141/164, 95% CI of 79.70–90.9 %). Bacteria, including 58.7 % (122/208) Gram-negative bacteria and 41.3 % (86/208) Gram-positive bacteria, were detected in 208 samples collected from the 164 patients (Figure 2A). Most samples with Gram-negative bacteria contained Escherichia coli (n=59), followed by Enterobacter cloacae (n=20), Klebsiella (n=20), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=18), and Acinetobacter baumannii complex (n=5). The predominant part of the Gram-positive bacteria was constituted by Enterococcus (n=61), Streptococcus (n=13), Staphylococcus aureus (n=8), and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (coNS) (n=4). Candidinoid fungi were found in 36 cases (Figure 2B). We found that the samples from 55.3 % (78/141) of the patients had multiple bacterial genera, including 56 patients with two bacterial genera (n=56), 19 patients with three bacterial genera (n=19), and three patients with four bacterial genera (Figure 2C).

Distribution of pathogens and the infection types in the patients.

Pathogen detection results in abdominal drainage fluid culture

A number of 164 patients with abdominal septic shock underwent routine drainage fluid culture. 117 patients had positive culture results, with a positive detection rate of 71.3 % (117/164, 95 % CI 63.8%–78.1 %). A total number of 182 strains of bacteria and 15 strains of fungi were detected in 117 patients, including 56.6 % (103/182) Gram-negative bacteria and 43.4 % (79/182) Gram-positive bacteria (Figure 2A). Based on the culture of these patients’ drainage fluids, 55.56 % (65/117) had multiple microbial infections, 48 patients were infected with two pathogens and 17 cases with three pathogens (Figure 2C). And the specific pathogen distribution of drainage fluid culture is showed in Figure 2D, Gram-negative bacteria were represented mainly by Escherichia coli (n=46), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=17), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=16), and Enterobacter cloacae (n=12). Gram-positive bacteria were represented by Enterococcus faecium (n=32), Enterococcus faecalis (n=14), and Enterococcus plumboflavus (n=11). Out of the 15 case samples with fungi detected, 13 were with Candida albicans and two with Candida tropicalis.

For routine drainage fluid culture, Enterobacter aerogenes (n=4), Proteus (n=2), Hydrophila/caviae aeromonas bacteremia (n=2), Comamonas aquatica (n=1), Raoultella ornithinolytica (n=1), and Citrobacter amalonaticus (n=1) of the Gram-negative bacteria were not included in ddPCR in our hospital. But all of the Gram-positive bacteria, Enterococcus casseliflavus (n=11), Enterococcus gallinarum (n=8), Enterococcus avium (n=4) Enterococcus hirae (n=1), and Enterococcus raffinosus (n=1) were included in the Enterococcus genus of ddPCR, while Streptococcus sanguis (n=3) and Streptococcus anginosus (n=2) were all included in the Streptococcus genus.

Pathogen detection results in drainage fluid smear results

A total number of 228 drainage fluid smear samples were collected from the 164 patients with abdominal septic shock. 115 samples were infected with Gram-negative bacteria, 84 samples with Gram-positive bacteria, and 31 samples with fungi (Figure 2A). The abdominal drainage samples were smear-positive in 129 cases, with a positive detection rate of 78.7 % (129/164, 95 % CI of 71.6–84.7 %). We also found that 55.3 % (78/164) of the patients had mixed infection with multiple pathogens (mixed infection refers to infection with at least two Gram-negative bacilli, Gram-positive cocci, and fungi). Of these 78 patients, 91.0 % had two types of pathogens (71/78), of which Gram-positive bacteria + Gram-negative bacteria was the most common combination (n=47, 47/71). The number of patients with Gram-negative bacteria + fungi was almost equal to that of Gram-positive bacteria + fungi (n=15, 15/71 vs. n=16, 16/71). 9 % (7/78) patients had three types pathogens (Gram-positive bacteria + Gram-negative bacteria + fungi). Fifty-one patients were infected with one type of pathogens (Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, or fungi), among which 29 cases were infected with Gram-negative bacteria, 20 cases were infected with Gram-positive bacteria, and only two cases were infected with fungi. Gram-negative bacteria were found in 115 smear samples (56.6 %) of the positive patients, Gram positive bacteria were detected in 84 smear samples (43.4 %), and fungi were observed in 31 smear samples (13.6 %) (Figure 2C).

Comparison of ddPCR and routine detection

Comparison of ddPCR and routine drainage fluid culture

A number of 111 cases (111/164=67.7 %) were positive for both ddPCR and routine drainage fluid culture, and 17 cases (17/164=10.4 %) were negative for both ddPCR and routine drainage fluid culture. Additionally, 30 cases (30/164=18.3 %) were positive for pathogens detected only by ddPCR and 6 cases (6/164=3.7 %) were positive for pathogens detected only by routine drainage fluid culture (Table 2A).

Consistency between ddPCR and routine tests (A: consistency between ddPCR and drainage fluid culture, B: consistency between ddPCR and drainage fluid smear).

| 2A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | ddPCR (+)/culture (−) | ddPCR (+)/culture (+) | ddPCR (−)/culture (+) | ddPCR (−)/culture (−) | PPA, % | NPA, % | PPV, % | PPV, % |

| All pathogens | 30 | 111 | 6 | 17 | 94.87 | 36.17 | 78.72 | 73.91 |

| Bacteria | 8 | 109 | 30 | 17 | 93.16 | 36.17 | 78.42 | 68.00 |

| Gram negative bacteria | 25 | 97 | 6 | 36 | 94.17 | 59.02 | 79.51 | 85.71 |

| Escherichia colie | 16 | 43 | 3 | 102 | 93.48 | 86.44 | 72.88 | 97.14 |

| Gram positive bacteria | 19 | 67 | 12 | 66 | 84.81 | 77.65 | 77 91 | 84.62 |

| Enterococcus | 18 | 41 | 5 | 100 | 89.13 | 84.75 | 69.49 | 95.24 |

| Fungi | 22 | 14 | 1 | 127 | 93.33 | 85.23 | 38.80 | 99.22 |

| A pathogen Multiple | 4 | 59 | 5 | 96 | 92.19 | 96.00 | 93.65 | 95.05 |

| pathogens | 2 | 61 | 3 | 98 | 95.31 | 98.00 | 96.83 | 97.03 |

|

|

||||||||

| 2B | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Pathogens | ddPCR (+)/smear (−) | ddPCR (+)/smear (+) | ddPCR (−)/smear (+) | ddPCR (−)/smear (−) | PPA, % | NPA, % | PPV, % | NPV, % |

|

|

||||||||

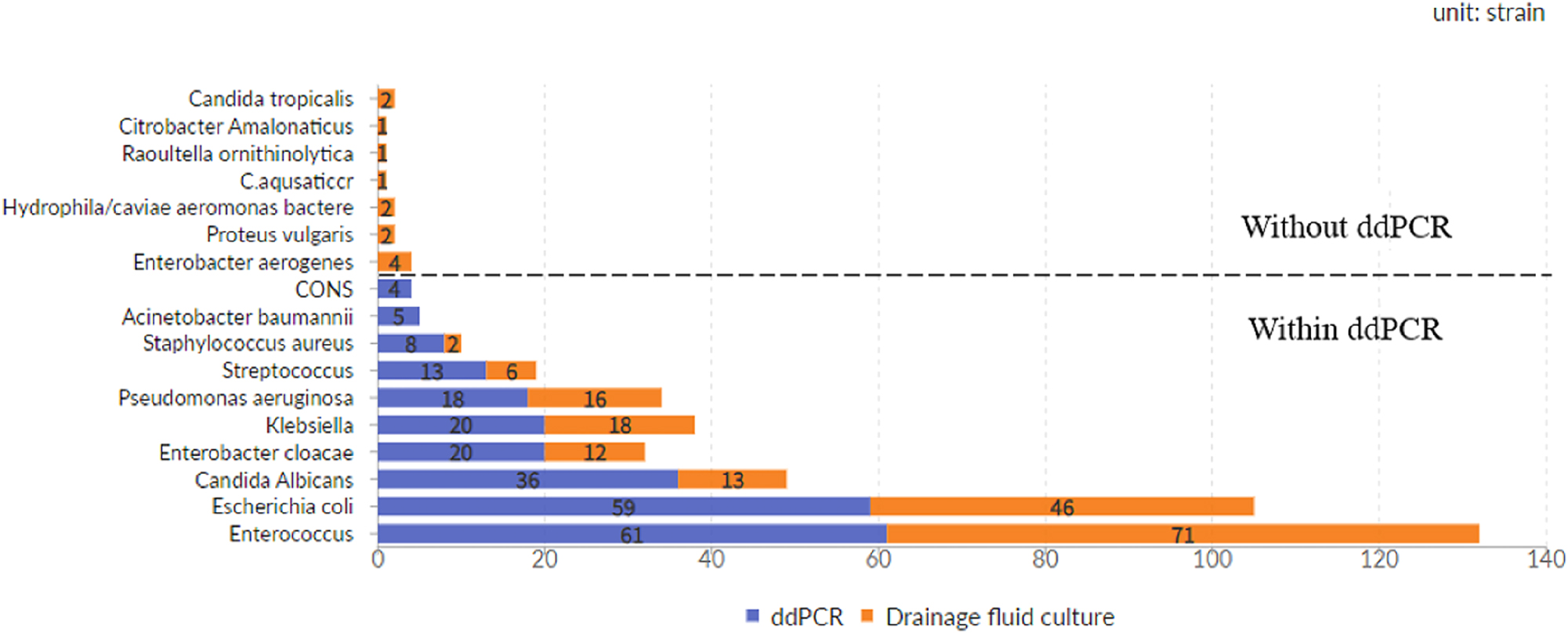

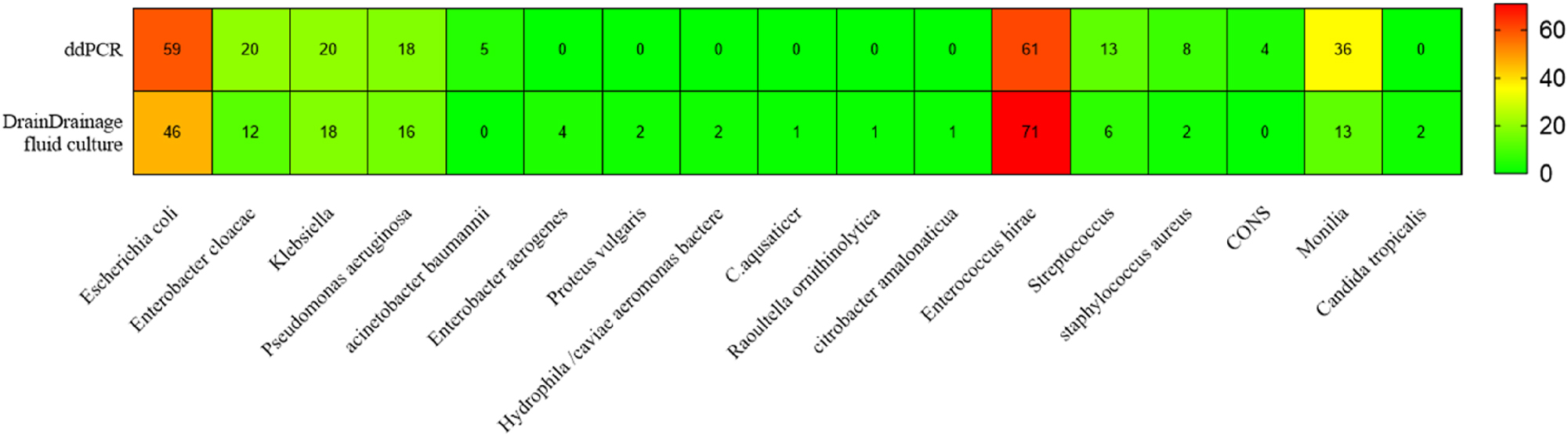

| All pathogens | 20 | 121 | 8 | 35 | 93.80 | 42.86 | 85.82 | 65.22 |

Of the 111 double-positive patients, ddPCR matched routine drainage fluid culture perfectly in 75 cases (strains by ddPCR matched strains by routine drainage fluid culture perfectly). Partially matching was observed in 25 cases (at least one pathogen overlapped between ddPCR and drainage fluid culture), and complete mismatching was found in 11 cases. Of the 25 perfectly matched cases, only seven had mixed infection, whereas the other 18 cases had single-pathogen infection. Out of the total 164 cases, ddPCR identified nine cases with two pathogens (5 cases of Acinetobacter baumannii complex and 4 cases of coNS) that were not positive in the routine drainage fluid culture (Figures 3 and 4).

Distribution of pathogens.

Consistent distribution of pathogens.

In the detection of specific pathogens, the specificity of ddPCR technology for fungal is significantly higher than bacteria. Furthermore, ddPCR exhibits greater sensitivity in detecting Gram-negative bacteria, albeit with relatively lower specificity. Notably, ddPCR demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity in detecting Escherichia coli compared to Enterococcus (Table 2A).

Comparison of ddPCR and abdominal drainage smear

The positive detection rate of ddPCR was higher than that of abdominal drainage smear (141/164 vs.129/164), and the positive rate of abdominal drainage fluid smear was slightly higher than that of abdominal drainage fluid culture (129/164 vs. 117/164). Twelve patients had positive results of the drainage fluid smear but negative results of the drainage fluid culture. Both ddPCR and smear were positive in 121 cases (121/164=73.8 %) and negative in 15 cases (15/164=9.1 %). Only 20 cases (12.2=43.6 %) were for single ddPCR and 8 cases (8/164=4.9 %) were for smear-positive (Table 2B).

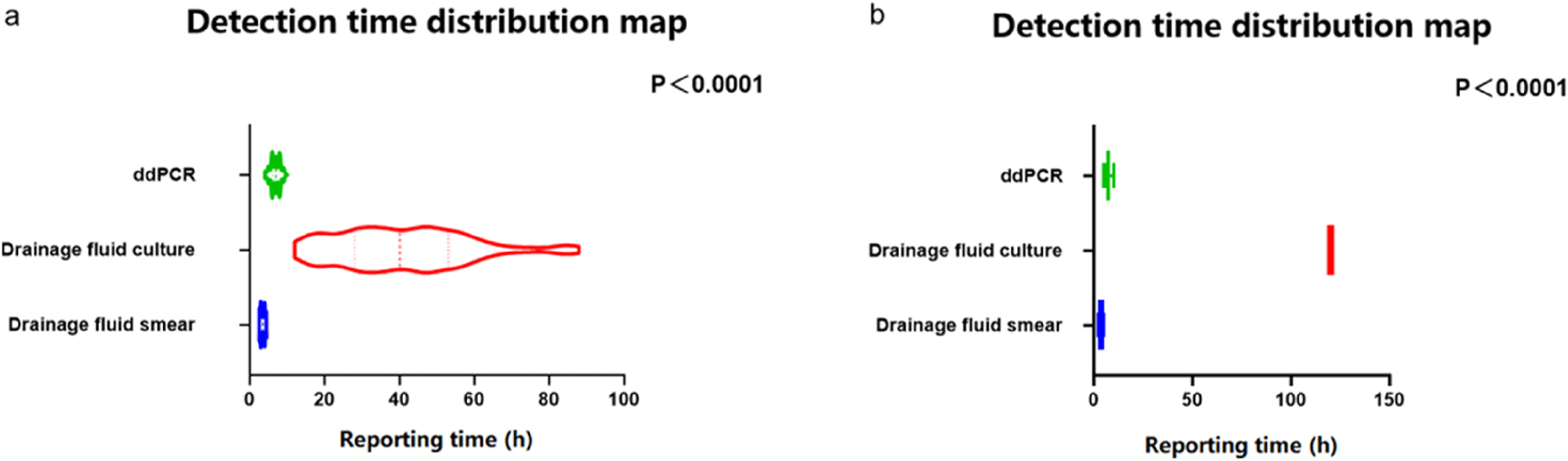

Comparison of the reporting time among ddPCR, abdominal drainage smear, and abdominal drainage fluid culture

Rapid pathogen diagnosis is critically important for optimizing anti-infection strategies in cases of abdominal sepsis. It not only enhances treatment efficacy but also reduces the development of antibiotic resistance, ultimately improving patient prognosis [7]. To this end, we compared the reporting times (RT) of different pathogen detection methods across 164 patients (Figure 5). For the positive results, the reporting time of abdominal drainage fluid culture (40.85 ± 1.61 h) was significantly longer than those of ddPCR (6.86 ± 0.12 h) and drainage smear (3.47 ± 0.06 h) (p<0.001). Moreover, the reporting time of ddPCR was significantly longer than that of drainage smear (6.86 ± 0.12 h vs.) 3.47 ± 0.06 h, p<0.001). For the negative results, the reporting time of abdominal drainage fluid culture (120 ± 0 h) was significantly longer than those of ddPCR (6.89 ± 1.22 h) and drainage smear (3.42 ± 0.68 h) (p<0.001). Furthermore, the reporting time of ddPCR was significantly longer than that of drainage smear (6.89 ± 1.22 h vs. 3.42 ± 0.68 h; p<0.001).

Comparison of the detection time (6a: Positive by abdominal drainage fluid culture; 6b: Negative by abdominal drainage fluid culture).

Evaluation of the drug resistance genes found by ddPCR

In this study, we also analyzed the results consistency of ddPCR antibiotic resistance gene assay with those of antimicrobial susceptibility assay (AST). Of the enrolled 141 positive patients, ddPCR showed that drug resistance genes were positive in 52 (36.9 %) patients, including 14 carbapenem-resistant patients (9 blaKPC gene-positive cases and 5 VanA + VanM-positive cases). Thirty-three patients had multiple drug resistance (21 MECA-positive and 12 Oxa-48-positive cases). AST showed that 117 patients with positive culture results were further tested for drug sensitivity. Of them, 47 patients were drug-resistant with a resistance rate of nearly 40 %. Eleven patients showed drug resistance (three cases were partial drug resistant). Two patients were carbapenem-resistant, nine patients were penicillin-resistant, and 25 patients were multiple drug-resistant (Table 3).

Evaluation table of drug resistance genes.

| Types of drug resistance | Resistance gene | Culture, n (%) | ddPCR, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-sensitivity | None | 70 (60) | 89 (63.1) |

| Drug resistance | – | 47 (40) | 52 (36.9) |

| Single-drug resistance | Single-drug resistance | 22 (18.8) | 19 (13.5) |

| Penicillin resistance | – | 9 (7.7) | – |

| Resistance to carbapenem | blaKPC | 2 (1.7) | 9 (6.4) |

| VanA + VanM | None | 5 (3.5) | |

| Others | – | 11 (9.4) | – |

| Multi-drug resistance | – | 25 (21.4) | 33 (23.4) |

| mecA | – | 21 (14.9) | |

| Oxa 48 | – | 12 (8.5) |

The comparison between ddPCR and AST showed that the positive rate of ddPCR was slightly lower than that of the routine culture (52/141 vs. 47/117), but the positive rates of ddPCR for carbapenem resistance (14/52 vs. 2/47) and multiple antibiotic resistance (33/52 vs. 25/47) were significantly higher than that of the routine culture. Antibiotics were adjusted in 39 patients (39/52, 75 %) after the drug resistance gene test.

Discussion

As shown in Table S1, this study showed that the positive rate of ddPCR for abdominal sepsis was 86 %, higher than that of the routine methods examined. Notably, 67.7 % of the patients were found positive by both ddPCR and routine methods, whereas 10.4 % were negative. The etiological results of ddPCR and routine methods were consistent, but the reporting time of ddPCR was significantly shorter than that of the routine culture. In addition, ddPCR also allowed for a timely change in the decisions for antibiotics administration based on the drug resistance gene test results.

Sepsis, a condition of organ dysfunction due to an improper response to infection, primarily affects the lungs (64 %) and abdominal cavity (20 %). Rapid diagnosis and early administration of suitable antibiotics are crucial for improving sepsis outcomes and reducing overall mortality [8]. International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021 recommends the immediate use of antibiotics within 1 h of diagnosis [9]. However, due to the increasing global burden of antibiotics resistance and the inappropriate use of antibiotics, accurate selection of antibiotics is difficult [5]. The inflammatory response of sepsis caused by abdominal infection is severe, and usually multiple-pathogen infections occur. The signs and symptoms of patients are usually non-specific, which increases the difficulty of antibiotic selection [10]. Currently, traditional drainage culture is still the gold standard for determining the etiological diagnosis of sepsis caused by abdominal infection, but a study indicates that the reporting time for such cultures is approximately 68.9 h [11]. In our study, even within the subgroup that exhibited positive microbiological findings, obtaining microbiological results necessitated approximately 40.85 h. It means the routine method is time-consuming. Furthermore, dominant bacteria can inhibit the growth of other bacteria, affecting the accuracy of culture results. These shortcomings lead to the failure of the routine culture method to meet the clinical needs of sepsis management [12]. Therefore, exploring rapid, sensitive and accurate etiological detection methods remains one of the keys to improving the prognosis of sepsis.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), which integrates high-throughput sequencing with bioinformatics analysis, enables the rapid and simultaneous detection of DNA or RNA from multiple pathogens. It is considered one of the promising methods for swift pathogen identification in patients with sepsis [13]. Li et al. indicates that in patients with abdominal sepsis, plasma mNGS can identify pathogens in just 27.1 ± 4.0 h, which is significantly shorter than the traditional culture method [11]. Recent studies further suggest that mNGS has the potential to optimize anti-infection treatment strategies for patients suffering from severe abdominal infections [14]. However, despite its capacity to detect all pathogens as a whole-genome high-throughput sequencing technology, mNGS entails considerable time and financial costs. Given the relatively low likelihood of atypical pathogens in abdominal infections, this may restrict the practical application of mNGS in such cases.

As an emerging rapid detection technology for targeted pathogens, extensive research has demonstrated that ddPCR can detect different bacterial pathogens in patients with sepsis or suspected BSI [15]. An expert statement showed that ddPCR has diagnostic advantages over blood culture for ICU patients with suspected blood infection, with sensitivity of 58.8–86.7 % and specificity of 73.5–92.2 % [5]. Zhou et al. [16] used ddPCR to detect bacteria and fungi in pleural and peritoneal fluids in critically ill patients and compared the results with those obtained by the routine culture method. Compared with the gold standard of pleural and peritoneal effusion culture, ddPCR had a sensitivity of 96 %, specificity of 87 and 60 %, positive predictive values of 92 and 87 %, and negative predictive values of 93 and 75 %, respectively. The results of this study are similar to previous studies, showing that the sensitivity and specificity of ddPCR for mixed bacteria in abdominal sepsis were 95.31 and 98 %, correspondingly. Furthermore, compared to mNGS, ddPCR can detect specific pathogens in a shorter amount of time. In this study, the reporting time for ddPCR was only 6.86 h, significantly less than the previously reported 27.1 h for mNGS. In addition, the rapid detection of drug-resistant genes by ddPCR in this study led to changes in the antibiotic selection in 75 % of the ddPCR pathogen-positive patients, which supports the conclusion that ddPCR is a rapid and sensitive etiological test for abdominal sepsis.

Despite its advantages, ddPCR has some disadvantages in the diagnosis of etiology. ddPCR has high sensitivity, is not affected by antibiotic use, and can be used for drug resistance genes testing with high reproducibility, which provides absolute quantification without standard curves [17]. In this study, ddPCR required only (6.86 ± 0.12) h to for pathogen identification, which was a reporting time advantage over the traditional culture. Although ddPCR excels in detecting specific pathogens due to its rapidity and high sensitivity, its detection range is limited [18]. In contrast, mNGS, as a whole-genome sequencing technology, offers broader coverage of pathogens and has significant advantages in diagnosing rare and atypical pathogens [13]. Additionally, ddPCR needs specific primers. Compared with blood cultures or mNGS, ddPCR can detect only pathogens contained in the ddPCR plate, which limits the detection of other potential microorganisms. The ddPCR designed in this study failed to detect all the pathogens in the bacterial culture. Then, ddPCR identifies pathogen information by detecting cell-free DNA (mcfDNA). Given that mcfDNA may originate from either active cells or cells that have undergone apoptosis, ddPCR can only quantify mcfDNA but is unable to determine its cellular origin. ddPCR has good potential to identify and exclude common pathogens, whereas mNGS is more suitable for diagnosing rare infections and refractory diseases [11]. Thus, it is necessary to design bacteria detection ddPCR profiles based on common pathogens in abdominal infection-induced sepsis.

In conclusion, the results showed that for sepsis associated with abdominal infections, ddPCR represents a promising method for the rapid detection of specific pathogens. However, it can only detect specific pathogens, and it is necessary to combine other rapid pathogen detection methods to further improve the precision of patient treatment.

Funding source: the Chongqing Science and Health Joint Medical Research Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021MSXM015

-

Research ethics: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University and all procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from individual participants or legal guardians included in the study.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Xiaoying Chen and Yan Peng carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Linlin Xiao performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Yan Peng participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Chongqing Science and Health Joint Medical Research Project (Project Number 2021MSXM015).

-

Data availability: Readers can email the corresponding author to obtain raw data.

References

1. Sartelli, M, Tascini, C, Coccolini, F, Dellai, F, Ansaloni, L, Antonelli, M, et al.. Management of intra-abdominal infections: recommendations by the Italian council for the optimization of antimicrobial use. World J Emerg Surg 2024;19:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-024-00551-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Hecker, A, Reichert, M, Reuß, CJ, Schmoch, T, Riedel, JG, Schneck, E, et al.. Intra-abdominal sepsis: new definitions and current clinical standards. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2019;404:257–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-019-01752-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Sartelli, M, Barie, P, Agnoletti, V, Al-Hasan, MN, Ansaloni, L, Biffl, W, et al.. Intra-abdominal infections survival guide: a position statement by the Global Alliance for Infections in Surgery. World J Emerg Surg 2024;19:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-024-00552-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Pinheiro, LB, Coleman, VA, Hindson, CM, Herrmann, J, Hindson, BJ, Bhat, S, et al.. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Anal Chem 2012;84:1003–11. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac202578x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Wu, J, Tang, B, Qiu, Y, Tan, R, Liu, J, Xia, J, et al.. Clinical validation of a multiplex droplet digital PCR for diagnosing suspected bloodstream infections in ICU practice: a promising diagnostic tool. Crit Care 2022;26:243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04116-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Rhodes, A, Evans, LE, Alhazzani, W, Levy, MM, Antonelli, M, Ferrer, R, et al.. Surviving sepsis campaign: International Guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Bova, R, Griggio, G, Vallicelli, C, Santandrea, G, Coccolini, F, Ansaloni, L, et al.. Source control and antibiotics in intra-abdominal infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024;13:776. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13080776.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Timsit, JF, Ruppé, E, Barbier, F, Tabah, A, Bassetti, M. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: an expert statement. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:266–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05950-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Evans, L, Rhodes, A, Alhazzani, W, Antonelli, M, Coopersmith, CM, French, C, et al.. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med 2021;49:e1063–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000005337.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Chaves, AA, Ferraro, JW, Yu, J, Moye, MJ, Yee, KL, Li, F, et al.. Characterization of ascending dose canine telemetry model supports its use in E14/S7B QT integrated risk assessments. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 2024;128:107525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vascn.2024.107525.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Li, D, Gai, W, Zhang, J, Cheng, W, Cui, N, Wang, H. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the microbiological diagnosis of abdominal sepsis patients. Front Microbiol 2022;13:816631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.816631.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Hu, B, Tao, Y, Shao, Z, Zheng, Y, Zhang, R, Yang, X, et al.. A comparison of blood pathogen detection among droplet digital PCR, metagenomic next-generation sequencing, and blood culture in critically ill patients with suspected bloodstream infections. Front Microbiol 2021;12:641202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.641202.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Liu, C, Song, X, Liu, J, Zong, L, Xu, T, Han, X, et al.. Consistency between metagenomic next-generation sequencing versus traditional microbiological tests for infective disease: systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2025;29:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-025-05288-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Mao, JY, Li, DK, Zhang, D, Yang, QW, Long, Y, Cui, N. Utility of paired plasma and drainage fluid mNGS in diagnosing acute intra-abdominal infections with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis 2024;24:409. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09320-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Merino, I, de la Fuente, A, Domínguez-Gil, M, Eiros, JM, Tedim, AP, Bermejo-Martín, JF. Digital PCR applications for the diagnosis and management of infection in critical care medicine. Crit Care 2022;26:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03948-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Zhou, F, Sun, S, Sun, X, Chen, Y, Yang, X. Rapid and sensitive identification of pleural and peritoneal infections by droplet digital PCR. Folia Microbiol 2021;66:213–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12223-020-00834-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Mirabile, A, Sangiorgio, G, Bonacci, PG, Bivona, D, Nicitra, E, Bonomo, C, et al.. Advancing pathogen identification: the role of digital PCR in enhancing diagnostic power in different settings. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024;14:1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14151598.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Lei, S, Chen, S, Zhong, Q. Digital PCR for accurate quantification of pathogens: principles, applications, challenges and future prospects. Int J Biol Macromol 2021;184:750–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Mini Review

- Current status and future perspectives on standardized training for laboratory medicine resident physicians in China

- Original Articles

- Comprehensive utilization of NMR spectra–evaluation of NMR-based quantification of amino acids for research and patient care

- Establishing serum zinc reference intervals with two different photometric assays and evaluating their impact on zinc deficiency prevalence

- Diagnostic validation of the GAAD algorithm for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Vietnam

- Effect of DNA input on analytical and clinical parameters of a circulating tumor DNA assay for comprehensive genomic profiling

- Application value of ddPCR in rapid detection of pathogens in abdominal sepsis

- Congress Abstracts

- German Congress of Laboratory Medicine: 20th Annual Congress of the DGKL and 7th Symposium of the Biomedical Analytics of the DVTA e. V.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Mini Review

- Current status and future perspectives on standardized training for laboratory medicine resident physicians in China

- Original Articles

- Comprehensive utilization of NMR spectra–evaluation of NMR-based quantification of amino acids for research and patient care

- Establishing serum zinc reference intervals with two different photometric assays and evaluating their impact on zinc deficiency prevalence

- Diagnostic validation of the GAAD algorithm for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Vietnam

- Effect of DNA input on analytical and clinical parameters of a circulating tumor DNA assay for comprehensive genomic profiling

- Application value of ddPCR in rapid detection of pathogens in abdominal sepsis

- Congress Abstracts

- German Congress of Laboratory Medicine: 20th Annual Congress of the DGKL and 7th Symposium of the Biomedical Analytics of the DVTA e. V.