Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the ovarian reserve (OR) in women with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), especially SLE-associated APS, and to determine the association between OR and clinical and laboratory parameters.

Methods

We compared the antral follicle count (AFC), anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B (INHB), antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), progesterone (P), testosterone (T), and estradiol (E2) among patients with primary APS (PAPS), SLE-APS, and SLE who were treated at Jinhua Central Hospital between 2017 and 2020. We conducted correlations and logistic regression analyses to identify the risk factors of OR failure in women with APS.

Results

Serum AMH were positively correlated with AFC and INHB in APS patients, and low AMH was independent risk factor for OR decline in APS patients. The ROC curve showed a high accuracy for AMH in the prediction of OR failure. Compared to healthy subjects (HS), patients with PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE exhibited lower serum AMH, AFC, INHB, and E2 levels and higher FSH and levels (p<0.05). Of all the patients, those with SLE-APS manifested the lowest serum AMH, AFC, INHB, and E2 levels and the highest FSH levels (p<0.05).

Conclusions

APS and SLE patients showed lower indications of OR, including AFC and AMH, compared to HS. SLE-APS patients also appeared to have a lower OR than either SLE or PAPS patients.

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody, is an autoimmune disease characterized by thrombosis, pregnancy complications [1], and is significantly associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is an autoimmune disease that involves an attack by the immune system on its own tissues, causing widespread inflammation and tissue damage in the affected organs. APS can occur as a primary condition or in the setting of SLE or another systemic autoimmune disease, and APS and SLE are closely related autoimmune diseases with overlapping clinical and biological characteristics [2]. Cervera et al. conducted a 10-year follow-up study of 1,000 patients with APS from 13 European countries and reported that 36.2 % of APS patients possessed associated SLE [3].

Secondary APS (SAPS) is observed in the context of a coexisting connective tissue disease such as SLE or rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and a majority of SAPS cases occur in conjunction with SLE. The 2006 International Consensus Statement on updating the classification criteria for APS did not recommend the use of the term SAPS. The statement instead recommended the documentation of the presence or absence of SLE which is more advantageous for disease classification rather than categorizing patients into primary and secondary APS [4]. Many experts now prefer the term SLE-APS, and SLE-APS patients are more likely to manifest thrombocytopenia than those with primary APS [5].

Although autoimmunity correlates with pregnancy complications [6], the use of therapeutic immunomodulators makes pregnancy relatively safe [7]. APS is more common in young women of reproductive age [8], and while the relationship between APS and female fertility is questioned [6, 7], adverse pregnancy outcomes constitute a major clinical manifestation of APS. Female patients of reproductive age with APS show a high risk of recurrent early pregnancy loss and late fetal loss [9]. Yamakami et al. [10] reported lower antral follicle count (AFC) and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in individuals with primary APS, suggesting reduced ovarian reserve (OR). Franco et al. [11] demonstrated that of 35 patients with SLE-APS, 51.4 % revealed a prior thromboembolic event, 40 % had a previous pregnancy loss and 8.5 % exhibited both. Ünlü et al. [12] reported that compared to SLE patients without aPL, those with aPL showed a higher prevalence of thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity. There may, however, be some differences in ovarian function among women with PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE.

We herein determined OR using traditional indicators such as AFC, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and AMH [13, 14]. Both AMH and INHB are members of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family that are secreted by ovarian granulosa cells [15, 16]. AMH mediates follicular development via an FSH-independent mechanism [10], while INHB suppresses FSH release [17]. Serum AMH also reflects a strong positive correlation with AFC in the general population [18, 19]. We compared differences in ovarian function in women with PAPS, SLE-APS and SLE, which could potentially explain pregnancy complications in these women.

Materials and methods

Study participants

For the present study we recruited women of childbearing age (19–44 years) with APS, SLE-APS, or SLE and who were admitted between 2017 and 2020 to the Department of Infertility, Jinhua Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinhua Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University.

APS was diagnosed using the 2006 Sapporo criteria [4], APS is present if at least one of the clinical criteria and one of the laboratory criteria that follow are met. Clinical criteria: vascular thrombosis; pregnancy morbidity (one or more unexplained deaths of a morphologically normal fetus at or beyond the 10th week of gestation, one or more premature births of a morphologically normal neonate before the 34th week, three or more unexplained consecutive spontaneous abortions before the 10th week of gestation); laboratory criteria: lupus anticoagulant (LA) present in plasma; anticardiolipin (aCL) antibody in serum, present in medium or high titer, anti-b2 glycoprotein-I antibody in serum (in titer>the 99th percentile), the above three indicators must present on two or more occasions, at least 12 weeks apart. SLE was diagnosed using the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria [20]. Fulfillment of at least four criteria, with at least one clinical criterion and one immunologic criterion. Clinical criteria: acute cutaneous lupus, chronic cutaneous lupus, oral ulcers nonscarring alopecia, synovitis involving two or more joints, serositis, renal involvement, neurologic involvement, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia. Laboratory criteria: low complement; positive of ANA, Anti-dsDNA (twice above laboratory), Anti-Sm and antiphospholipid antibody. SLE-APS was diagnosed based on both the 2006 Sapporo criteria and 2012 SLICC classification criteria. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, malignant tumors were excluded from the study.

We recruited a total of 106 patients with PAPS or SLE-APS and 52 patients with SLE, and data were collected on their initial hospital visits, including blood markers and ultrasound findings. In addition, we collected 48 healthy subjects (HS) without any of the aforementioned diseases or obstetric morbidity. Not every participant exhibited a regular menstrual cycle and none used oral contraceptives or sex hormone-containing medications prior to providing a blood sample. Informed written consent was provided by all participants. We evaluated serum AMH, INHB, aCL antibody, and β2-GPI levels, and measured sex hormones that included FSH, progesterone (P), testosterone (T), and estradiol (E2). Total AFCs for the left and right ovaries were determined adopting a sonographic device. In this cross-sectional study we compared antral follicle count (AFC) and blood levels of several markers associated with ovarian reserve in patients with APS (±SLE) or SLE and healthy subjects.

Blood specimen collection and measurements

Venous blood samples were collected from women between 08:00 am and 09:00 am on days 2–4 of the early follicular phase of their menstrual cycles. The serum concentrations of AMH, INHB, β2-GPI, and aCL antibodies were analyzed using a chemiluminescence analyzer (iFlash Yahuilong Company Shenzhen). The aCL, aβ2GPI were detected by chemiluminescence with cut-off of positivity as defined at levels of aCL IgG/IgM antibodies >10 PLU/mL and aβ2GPI IgG/IgM antibodies >20 AU/mL, following manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma samples were tested for the presence of LA according to the recommended criteria from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Phospholipid-Dependent Antibodies [21]. The levels of FSH, P, T, and E2 were assessed using a chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer (UniCel DxI 600 Beckman Coulter U.S.). The total numbers of follicles within the left and right ovaries were determined using ultrasonography. All experimental assays were conducted in strict accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 software. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as medians and confidence intervals (CIs). We analyzed differences between groups by applying the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test [22], and differences across three or four groups were determined using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H test [23]. Multivariate logistic regression analysis [24] was executed to determine whether AMH levels were related to OR decline in APS patients after adjusting for other variables. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was measured to evaluate the accuracy and threshold for predicting OR decline among APS patients. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Clinical and serologic characteristics of PAPS, SLE-APS and SLE patients

When diagnosing PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients through clinical and serologic characteristics (Table 1), we discerned diagnostic differences between PAPS, SLE-APS and SLE. We collected relevant data from 37 patients with PAPS, 69 patients with SLE-APS and 52 patients with SLE. The median ages of these three groups were similar, at 28, 30, and 29 years respectively. In terms of clinical characteristics: there was little difference in the probability of miscarriage among the three groups, with rates of 21.6 %, 28.9 %, and 23 % respectively, however, SLE-APS patients had the highest probability; regarding joint involvement, skin involvement, renal involvement, and neurologic involvement, both SLE patients and SLE-APS patients had higher occurrence rates compared to APS patients which had a much lower probability rate. In terms of blood indicators such as ANA, Anti-dsDNA, Anti-Ro/SSA, Anti-La/SSB; both SLE patients and SLE-APS patients showed higher positive rates especially for ANA while APS patients almost always tested negative; for altered coagulation parameters, LA, β2-GPI, aCL levels; APS patients as well as SLE-APS patients had higher positive rates whereas the likelihood of SLE patients was much lower. In terms of subsequent medication treatment, the likelihood of using low-dose aspirin, LMWH, and warfarin is higher in APS patients and SLE-APS patients compared to SLE patients. On the other hand, SLE patients and SLE-APS patients have a higher probability of using hydroxychloroquine, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressives, and NSAIDs than APS patients.

Clinical and serologic characteristics of PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE groups.

| PAPS (n=37) | SLE-APS (n=69) | SLE (n=52) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years | 28 | 30 | 29 |

| Altered coagulation parameters, % | 84.5 | 78.6 | 19.2 |

| Pregnancy losses, % | 21.6 | 28.9 | 23.0 |

| Joint involvement, % | 5.4 | 79.7 | 86.5 |

| Skin involvement, % | 0 | 65.2 | 69.2 |

| Renal involvement, % | 0 | 21.7 | 38.5 |

| Neurologic involvement, % | 0 | 13.0 | 17.3 |

| ANA positivity, % | 2.7 | 91.3 | 92.3 |

| Anti-dsDNA positivity, % | 0 | 44.9 | 44.2 |

| Anti-Ro/SSA positivity, % | 0 | 23.2 | 23.1 |

| Anti-La/SSB positivity, % | 0 | 14.5 | 15.3 |

| LA, % | 79.5 | 77.8 | 0 |

| β2-GPI, % | 27.9 | 26.3 | 3.6 |

| aCL, % | 58.5 | 60.5 | 4.5 |

| Low-dose aspirin, % | 26.2 | 29.1 | 3.8 |

| LMWH, % | 25.3 | 27.6 | 1.5 |

| Warfarin, % | 48.9 | 40.3 | 5.7 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, % | 0 | 81.5 | 89.1 |

| Glucocorticoids, % | 15.5 | 75.5 | 58.8 |

| Immunosuppressives, % | 0 | 49.1 | 58.1 |

| NSAIDs | 8.4 | 84.7 | 89.5 |

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of ovarian reserve

In univariable analysis, age, AMH, INHB, FSH, E2 were all significantly associated with the occurrence of ovarian reserve in 106 APS patients (p<0.001). These six parameters which were significantly different between APS and HS groups were utilized to analyze the association with ovarian reserve decline using multivariable logistic regression, the results (Table 2) showed that AMH (OR 0.014, 95 % CI 0.001–0.0193) was the independent risk factor for ovarian reserve decline in APS patients (defined as an AFC<10 [25]) with the number of follicles reflecting follicle diameters of 2–9 mm in both ovaries (Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis of the association of variables with ovarian reserve decline.

| Variables | Univariate | p-Value | Multivariate | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | 95 % CI | β | OR | 95 % CI | |||

| Age, years | 0.363 | 1.438 | 1.244–1.662 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 1.081 | 0.920–1.269 | 0.344 |

| AMH, ng/mL | −5.34 | 0.005 | 0.001–0.040 | 0.000 | −4.265 | 0.014 | 0.001–0.0193 | 0.001 |

| INHB, pg/mL | −0.148 | 0.862 | 0.817–0.910 | 0.000 | −0.007 | 0.993 | 0.914–1.079 | 0.877 |

| FSH, IU/L | 0.528 | 1.695 | 1.351–2.125 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 1.030 | 0.712–1.489 | 0.877 |

| E2, pmol/L | −0.034 | 0.967 | 0.953–0.981 | 0.000 | −0.015 | 0.985 | 0.966–1.003 | 0.109 |

| aCL, RU/mL | 0.011 | 1.011 | 0.997–1.025 | 0.055 | – | – | – | – |

| β2-GPI, AU/mL | 0.001 | 1.001 | 0.964–1.040 | 0.994 | – | – | – | – |

| P, nmol/L | −0.486 | 0.615 | 0.235–1.610 | 0.322 | – | – | – | – |

| T, nmol/L | −0.001 | 1.083 | 0.983–1.015 | 0.912 | – | – | – | – |

-

Ovarian reserve decline is indicated by antral follicle count <10.

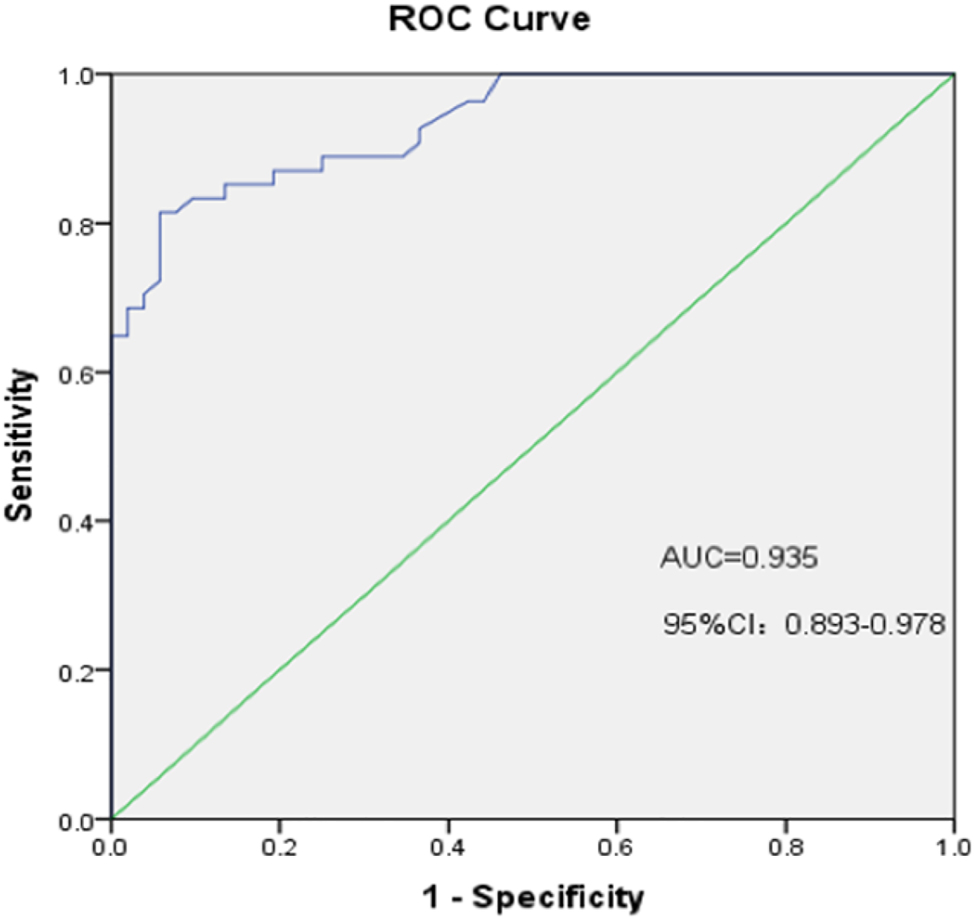

ROC curves of AMH to predict ovarian reserve decline of APS patients

The ROC curve reflects the relationship between sensitivity and specificity. Our analysis of the ROC curve indicated that AMH level was highly accurate in predicting ovarian reserve decline (AUC=0.935; 95 % CI, 0.893–0.978; p<0.001; Figure 1). Based on the ROC curve, we identified an AMH value of 0.67 ng/mL as the threshold for predicting ovarian reserve decline in APS patients.

ROC curves of AMH to predict ovarian reserve decline. AUC of AMH of APS patients in ovarian reserve decline is 0.935 (95 % CI: 0.893–0.978; p<0.001).

AMH correlates with INHB, age, and AFC in APS patients

In order to understand the correlation between INHB, age, AFC, and aCL antibody data with AMH. We took Spearman correlation analysis [26] of APS patients, which showed that AMH correlates with INHB, age, and AFC in APS patients, among AMH was positively correlated with INHB and total AFC, negatively correlated with age, and not correlated with aCL antibody.

AMH, INHB, AFC, E2, and P differ among PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients

We compared the immune-related blood tests and total (Figure 2) AFCs among HS, PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE groups (Table 3), and demonstrated that AMH and AFC levels were lower in APS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients compared with HS, and that FSH levels in the disease groups were higher than in the HS group, but that E2 was reduced.

Correlation analysis of AMH with INHB, aCL antibody, age, and AFC in APS patients.

Comparison of blood indices and antral follicle count of HS, PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE groups before treatment.

| HS (n=48) | PAPS (n=37) | SLE-APS (n=69) | SLE (n=52) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 28 (26–33) | 28 (26.5–30) | 30 (28–31) | 29 (26–31.75) | 0.274 |

| AMHa, ng/mL | 2.61 (1.50–3.35) | 1.69 (1.06–2.02) | 0.45 (0.13–0.78) | 0.89 (0.33–1.32) | 0.000 |

| INHBb, pg/mL | 56.55 (34.28–66.53) | 36.6 (32.8–45.2) | 20.2 (15.3–29.5) | 36.75 (22.08–56.23) | 0.000 |

| AFCb, N | 15 (10–17) | 11 (10–13) | 7 (5–10) | 9.5 (7–12) | 0.000 |

| FSHb, IU/L | 6.02 (4.44–8.18) | 7.88 (5.66–8.94) | 9.97 (8.44–11.3) | 8.35 (5.46–9.87) | 0.000 |

| E2b, pmol/L | 182 (117–321.3) | 95 (76.5–115) | 56 (34–87.5) | 87 (65.5–121.8) | 0.000 |

| Pc, nmol/L | 2 (1.64–2.22) | 1.7 (1.4–1.99) | 1.66 (1.36–1.88) | 1.86 (1.48–2.0) | 0.000 |

| T, nmol/L | 1.68 (1.47–1.99) | 1.45 (1.22–1.89) | 1.48 (1.26–1.86) | 1.91 (1.45–2.35) | 0.309 |

| β2-GPI, AU/mL | 5.35 (4.93–6.5) | 5.8 (5–10.3) | 6.15 (5.1–10.35) | 5.45 (5–8.85) | 0.261 |

| aCLc, PLU/mL | 6.35 (5–8.38) | 12.2 (6.3–37.6) | 20.1 (6.3–97.85) | 7.5 (5–19.8) | 0.000 |

-

Data are expressed as median (Q25–Q75); HS, healthy subjects; ap <0.05, the four groups were compared in pairs; bp <0.05, the four groups were compared in pairs except for PAPS and SLE groups; cp <0.05, PAPS and SLE-APS groups were compared with healthy controls.

Discussion

APS is an autoantibody-mediated disorder that primarily affects the platelets, resulting in recurrent thrombosis and its sequelae, including pregnancy loss. APS is principally diagnosed between 20 and 50 years of age and affects 3–5 times more women than men. APS is considered to be a systemic autoimmune disease and may coexist with other autoimmune diseases, with SLE being the most frequently reported. A decline in OR is frequently uncovered in patients with autoimmune diseases such as SLE [27]. A meta-analysis by Wahl et al. [28] reported that patients with SLE and APS were at an approximately six-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism compared to women without APS. We now appreciate that AMH is a reliable marker of OR that can predict early ovarian follicle loss and menopausal onset in the general population [29]. For example, Yamakami et al. [10] reported reduced AFC and AMH levels in individuals with primary APS, suggesting an OR decline, and Luo et al. [30] also demonstrated that SLE was associated with low AMH levels. In our study, we classified the three diseases by clinical and serologic characteristics (Table 1), and determined that the OR decline in APS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients differed in terms of blood indices.

Serum AMH is a cost-effective and reliable marker of OR that is highly and positively correlated with AFC. In our study, we depicted serum AMH levels as positively correlated with AFC and INHB levels in APS patients (Figure 2). Therefore, serum INHB levels during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle directly reflect AFC. We also found that APS patients manifested an AMH level <0.5 ng/mL, which accounted for a high proportion of the total (40.17 %). The mean AMH level and AFC were lower in the PAPS, SLE-APS, and SLE groups relative to the HS group (p<0.05) (Table 3), congruent with the findings of Yamakami et al., who reported reduced AFC and AMH levels with primary APS [10]. Martins et al. [31] showed lower AMH levels in the majority of patients with SLE compared to HS. In our study, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that low AMH levels constituted independent risk factor for the decline in OR in APS patients (Table 2), and our ROC curve showed that AMH was highly accurate in predicting OR failure (Figure 1). We posit that AMH may be used to evaluate OR in APS patients, we identified an AMH value of 0.67 ng/mL as the appropriate threshold for predicting OR failure in APS patients.

Autoimmunity is one of the factors involved in premature ovarian failure (POF) [32]. Morel et al. [33] found that AMH levels are low in SLE patients and decrease significantly with age and cyclophosphamide (CYC) exposure. CYC is an alkylating agent which is widely used to treat SLE, using CYC often results in a lower cumulative dose, particularly with oral CYC, may ultimately reach cumulative doses associated with significant, long-term toxicity. Clowse et al. [34] think administration to a female patient of several pulse CYC regimens over the course of SLE poses a risk of premature ovarian insufficiency particularly for women in their 30 and 40 s, even if the risk from a single treatment is relatively small. Our patients did not receive CYC before diagnosed, and this therefore did not contribute to the reduced OR. POF primarily presents with a decline in OR, and is characterized by a reduction in AFC, AMH, and INHB levels, and in augmented FSH levels [35]. We observed similar results for APS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients compared to the HS group. In addition, E2 and P levels also decreased in each group (Table 3). FSH is required for the production and maturation of ovarian oocytes, and FSH levels drop on approximately day three of the menstrual cycle. FSH testing on day 3 may therefore be useful for evaluating OR, and in the present study we evaluated the FSH level on days 2–4. In addition to FSH, E2 levels should also be measured. E2 maintains the reproductive system, but high E2 levels suppress FSH. Furthermore, AMH decreases the activities of FSH-induced aromatase in granulosa cells [36]; in turn, high FSH levels is provoked by a reduction in AMH. In our study we found that among the disease groups, lower AMH and INHB levels correlated with higher FSH and low and steady E2 levels. The elevated FSH levels may be principally due to the lack of inhibition by AMH and INHB.

E2 plays a negative role in autoimmune diseases and SLE exhibits a significant female bias, particularly when E2 is at its peak [37]. In one study entailing a mouse model, the authors found that estrogen worsened the outcomes of autoimmune disease treatment [38]. However, at the beginning of menstruation (i.e., days 2–5), we discerned that the E2 level was significantly lower in the three disease groups than in the HS group, and SLE-APS manifested a particularly lower, while the E2 levels did not increase during this period and remained at low levels. In an article published in 2003, McMurray et al. found that the E2 levels in female SLE patients were different from those of their HS group; compared to the latter, the E2 level of SLE patients was either low, high, or showed no difference [39]. However, due to the lack of uniform collection strategies for blood testing in terms of the day of the menstrual cycle and detection methods used at the time of these disparate studies, there may be variations in these results. The difference in the collection times of blood samples for E2 measurements during the menstrual cycle appears to constitute the principal reason for the difference in E2 levels. In addition, the selection of assay methods and patient population may also be responsible for the observed differences. Further research is therefore required to determine the reasons for the particularly low E2 level in our SLE-APS patients on days 2–5 of the menstrual cycle.

P is the upstream precursor of T and E2, is necessary to maintain pregnancy, and a decline in P levels stimulates uterine contractions to initiate labor in humans, resulting in delivery [40]. In agreement with our study, Verthelyi et al. [41] found that the P concentration was not different in SLE patients compared to HS; however, we did show that the P level was reduced in patients with APS and SLE-APS. Velayuthaprabhu et al. [42] found that serum E2 and P levels were significantly reduced in studies in mice, suggesting that human β2-GPI may be involved in APS pregnancy failure through its effects on serum hormones. Therefore, the observed drop in P levels may be due to the presence of related antibodies in APS patients, leading to the decline in ovarian function.

APS is an autoimmune disease with detectable lupus anticoagulant (LA), aβ2GPI antibody or aCL antibody in serum, and approximately 20–40 % of SLE patients are aPL positive [12]. There is evidence showing that the presence of aPL is associated with attenuated AMH levels, while some studies show no relationship between them [43]. The AMH levels in our disease groups were lower than in the HS, with AMH reduced in the SLE group relative to the PAPS group, and lower in the SLE-APS group compared to the other two groups. The aCL level was higher in the disease groups relative to HS group: it was higher in the PAPS group compared to the SLE group, and the SLE-APS group had a higher aCL level than the other two groups (Table 3). While serum anti-B2-GPI antibody in APS patients may significantly improve the predictive rate and diagnostic value of thrombotic complications, it also possesses a high diagnostic value. However, the sensitivity of our B2-GPI antibody was not high and there was little difference in the levels among groups. Pekonen et al. [44] found circulating antibodies against ovarian tissue in the serum of lupus patients, suggesting the existence of autoimmune ovarian lesions in SLE patients [45]. Chen et al. [46] determined that antibodies were directed against pre-ovulatory follicle cells but not to corpus luteum-specific antigens, and this may impact OR in PAPS patients. We postulate that aPL antibodies reduce AMH, and that the reduction in AMH levels is more significant in cases of superimposed antibodies. Furthermore, reduced serum AMH levels may be due to insults against the ovarian microvasculature such as a thrombotic event. Likewise, the AFC of the SLE-APS group was the lowest among the groups, implying that growth of the primordial follicle cohort was impaired within an aPL milieu, and that the ovarian blood supply predisposed the primordial follicle cohorts to ischemic microvascular events.

There were some limitations to the present study. We collected as the total sample size all related cases from Jinhua Central Hospital over the past four years, and analyzed the blood indicators of patients who had been diagnosed but not yet treated with drugs. However, some SLE-APS patients were enrolled on the basis of their SLE disease, and these patients generally underwent drug treatment for SLE; therefore, several SLE-APS blood indicators likely contained some drug interference. The number of collected specimens was also limited and the changes in various indicators of the menstrual cycle were not monitored. Therefore, the dynamic changes in indices occurring over the menstrual cycle could not be compared. For example, the E2 level in the disease group (particularly in the SLE-APS group) was lower at approximately day 3, but the E2 levels for subsequent periods were not determined. Median AMH of the healthy subjects which is lower than typically observed in healthy women of the same age. The inconsistent data regarding AMH were also likely related to the differences in the phase of the menstrual cycle during which our testing was conducted.

Conclusions

In this study we ascertained that the AMH and AFC levels were lower in APS, SLE-APS, and SLE patients compared with HS patients, low AMH levels and high LH constituted independent risk factor for the decline in OR in APS patients, and that AMH and AFC levels were lower in SLE-APS patients relative to other groups. FSH and LH levels in the disease groups were also higher than in HS women, but the E2 level was reduced and exhibited no inhibitory effect on the gonadotropins, which was potentially caused by characteristically low AMH levels. The low levels of AMH may have been provoked by aCL or other related antibodies acting on the ovarian microvasculature, and this may have produced the lowest OR in SLE-APS patients.

Funding source: the public welfare science and technology fund project of Jinhua

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2017-4-063

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-4-041

Acknowledgments

We thank LetPub, LLC (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

-

Research ethics: All experiments were performed in accordance with the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2017-59).

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

-

Author contributions: Conception and design of the research: Junqi Wu. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: Junqi Wu, Xiaoping Xu. Statistical analysis: Xiaoping Xu and Huabin Wang. Drafting the manuscript: Xiaoping Xu, Shuqian Cai. Manuscript revision for important intellectual content: Junqi Wu, Xiaoping Xu, Huabin Wang, Shuqian Cai. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest, and that they alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by the Public Welfare Science and Technology Fund Project of Jinhua Hospital (2017-4-063; 2021-4-041).

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital upon reasonable request of the authors and with the permission of Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital. However, restrictions apply as to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this specific study.

References

1. Ruiz-Irastorza, G, Crowther, M, Branch, W, Khamashta, MA. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Lancet 2010;376:1498–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60709-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Belizna, C, Stojanovich, L, Cohen-Tervaert, JW, Fassot, C, Henrion, D, Loufrani, L, et al.. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome and antiphospholipid syndrome associated to systemic lupus: are they different entities? Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:739–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Cervera, R, Serrano, R, Pons-Estel, GJ, Ceberio-Hualde, L, Shoenfeld, Y, de Ramon, E, et al.. Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 10-year period: a multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1011–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204838.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Miyakis, S, Lockshin, MD, Atsumi, T, Branch, DW, Brey, RL, Cervera, R, et al.. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemostasis 2006;4:295–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Unlu, O, Erkan, D, Barbhaiya, M, Andrade, D, Nascimento, I, Rosa, R, et al.. The impact of systemic lupus erythematosus on the clinical phenotype of antiphospholipid antibody-positive patients: results from the antiphospholipid syndrome alliance for clinical trials and international clinical database and repository. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:134–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23584.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Chighizola, CB, Raimondo, MG, Meroni, PL. Does aps impact women’s fertility? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0663-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Deroux, A, Dumestre-Perard, C, Dunand-Faure, C, Bouillet, L, Hoffmann, P. Female infertility and serum auto-antibodies: a systematic review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2017;53:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-016-8586-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Warren, JB, Silver, RM. Autoimmune disease in pregnancy: systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 2004;31:345–72, vi-vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2004.03.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Salafia, CM, Starzyk, K, Lopez-Zeno, J, Parke, A. Fetal losses and other obstetric manifestations in the antiphospholipid syndrome. In: The antiphospholipid syndromes. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1996:117–31 pp.10.1201/9781351077125-10Suche in Google Scholar

10. Yamakami, L, Serafini, P, de Araujo, D, Bonfa, E, Leon, EP, Baracat, EC, et al.. OR in women with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2014;23:862–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203314529468.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Franco, JS, Molano-González, N, Rodríguez-Jiménez, M, Acosta-Ampudia, Y, Mantilla, RD, Amaya-Amaya, J, et al.. The coexistence of antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus in Colombians. PLoS One 2014;9:e110242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110242.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Ünlü, O, Zuily, S, Erkan, D. The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol 2016;3:75. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0085.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Randolph, JFJr, Harlow, SD, Helmuth, ME, Zheng, H, McConnell, DS. Updated assays for inhibin B and AMH provide evidence for regular episodic secretion of inhibin B but not AMH in the follicular phase of the normal menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod 2013;29:592–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det447.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. La Marca, A, Sighinolfi, G, Radi, D, Argento, C, Baraldi, E, Artenisio, AC, et al.. Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Hum Reprod Update 2009;16:113–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmp036.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Jamil, Z, Fatima, SS, Ahmed, K, Malik, R. Anti-Mullerian hormone: above and beyond conventional OR markers. Dis Markers 2016;2016:5246217. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5246217.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Fiçicioǧlu, C, Kutlu, T, Baglam, E, Bakacak, Z. Early follicular anti-müllerian hormone as an indicator of OR. Fertil Steril 2006;85:592–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Du, Y-Y, Guo, N, Wang, Y-X, Hua, X, Deng, TR, Teng, XM, et al.. Urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to serum anti-Müllerian hormone and inhibin B levels among women from a fertility center: a retrospective analysis. Reprod Health 2018;15:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0469-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Ireland, J, Mossa, F. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH): a biomarker for the or, ovarian function and fertility in dairy cows. J Anim Sci 2018;96:343. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/sky404.756.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Stelcla, M, Belaskova, S, Machac, S, Fiserova, E, Hubinka, V. Antimüllerian hormone (Amh) levels and antral follicle count (Afc) as predictors of the ovarian reaction in young healthy women. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of Palacky University in Olomouc; 2017:161 p.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Petri, M, Orbai, A-M, Alarcón, GS, Gordon, C, Merrill, JT, Fortin, PR, et al.. Derivation and validation of the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34473.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Devreese, KMJ, de Groot, PG, de Laat, B, Erkan, D, Favaloro, EJ, Mackie, I, et al.. Guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection and interpretation. J Thromb Haemostasis 2020;18:2828–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Karadimitriou, SM, Marshall, E, Knox, C. Mann-Whitney U test. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University; 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Ostertagova, E, Ostertag, O, Kováč, J. Methodology and application of the Kruskal-Wallis test[C]//applied mechanics and materials. Slovakia: Trans Tech Publications Ltd; 2014, 611:115–20 pp.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.611.115Suche in Google Scholar

24. Sperandei, S. Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochem Med 2014;24:12–8. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2014.003.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Penzias, A, Azziz, R, Bendikson, K, Falcone, T, Hansen, K, Hill, M, et al.. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2020;114:1151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.134.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. De Winter, JCF, Gosling, SD, Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: a tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol Methods 2016;21:273. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000079.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Pacucci, V, Ceccarelli, F, D’Ambrosio, V, Colasanti, T, Aliberti, C, Spinelli, FR, et al.. Fri0390 impaired ovarian reserve in patients affected by systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:728.10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.4936Suche in Google Scholar

28. Wahl, DG, Guillemin, F, de Maistre, E, Perret, C, Lecompte, T, Thibaut, G. Risk for venous thrombosis related to antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus – a meta-analysis. Lupus 1997;6:467–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/096120339700600510.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Victoria, M, Labrosse, J, Krief, F, Cedrin-Durnerin, I, Comtet, M, Grynberg, M. Anti Müllerian hormone: more than a biomarker of female reproductive function. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2018;48:19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.10.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Luo, W, Mao, P, Zhang, L, Chen, X, Yang, Z. Assessment of OR by serum anti-Müllerian hormone in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med 2020;9:207–15. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2020.02.11.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Martins, NFE, Seixas, MI, Pereira, JP, Costa, MM, Fonseca, JE. Anti-Müllerian hormone and OR in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2853–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3797-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Vega, M, Barad, DH, Yu, Y, Darmon, SK, Weghofer, A, Kushnir, VA, et al.. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels decline with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016;76:333–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12551.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Morel, N, Bachelot, A, Chakhtoura, Z, Ghillani-Dalbin, P, Amoura, Z, Galicier, L, et al.. Study of anti-Müllerian hormone and its relation to the subsequent probability of pregnancy in 112 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, exposed or not to cyclophosphamide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3785–92. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-1235.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Clowse, MB, McCune, WJ. General toxicity of cyclophosphamide in rheumatic disease[J]. UpToDate [Internet]. Walthan (MA): UpToDate Inc, 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Committee CMDARMS. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of infertility in advanced age women (revised edition). Reprod Develop Med 2017;1:145. https://doi.org/10.4103/2096-2924.224215.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Cook, CL, Siow, Y, Taylor, S, Fallat, ME. Serum Müllerian-inhibiting substance levels during normal menstrual cycles. Fertil Steril 2000;73:859–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00639-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Pham, GS, Mathis, KW. Autoimmunity, estrogen, and lupus. In: LaMarca, B, Alexander, BT, editors. Sex differences in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. United States: Elsevier; 2019:219–37 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-813197-8.00014-2Suche in Google Scholar

38. Verthelyi, D, Ansar Ahmed, S. Characterization of estrogen induced autoantibodies to cardiolipin in non-autoimmune mice. J Autoimmun 1997;10:115–25. https://doi.org/10.1006/jaut.1996.0121.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. McMurray, RW, May, W. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus: review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2100–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.11105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Doria, A, Cutolo, M, Ghirardello, A, Zampieri, S, Vescovi, F, Sulli, A, et al.. Steroid hormones and disease activity during pregnancy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum;47:202–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10248.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Verthelyi, D, Petri, M, Ylamus, M, Klinman, DM. Disassociation of sex hormone levels and cytokine production in SLE patients. Lupus 2001;10:352–8. https://doi.org/10.1191/096120301674365881.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Velayuthaprabhu, S, Chinnathambi, A, Alharbi, SA, Matsubayashi, H, Archunan, G. Relationship between fetal loss and serum gonadal hormones level in experimental antiphospholipid syndrome mouse. Indian J Clin Biochem 2017;32:347–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-016-0618-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Gasparin, A, Souza, L, Siebert, M, Xavier, RM, Chakr, RM, Palominos, PE, et al.. Assessment of anti-Müllerian hormone levels in premenopausal patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2016;25:227–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315598246.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Pekonen, F, Siegberg, R, Makinen, T, Miettinen, A, Yli-Korkala, O. Immunological disturbances in patients with premature ovarian failure. Clin Endocrinol 1986;25:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.1986.tb03589.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Samaritano, LR. Menopause in patients with autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:A430–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Chen, HH, Lin, CH, Chao, WC. Risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with anti-phospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Front Med 2021;8:559. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.654791.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Adequate cefazolin therapy for critically ill patients: can we predict active concentrations from given protein-binding data?

- Fully automated chemiluminescence microarray immunoassay for detection of antinuclear antibodies in systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases

- Evaluation of a Treponema IgG ELISA alone and in combination with an IgM ELISA as substitutes for Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) as confirmatory tests in a two-tier diagnostic algorithm for diagnosis of syphilis infection

- Research on the stability changes in expert consensus of the ACTH detection preprocessing scheme

- Female patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)-associated antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) have a lower ovarian reserve than either primary APS or SLE patients

- Short Communication

- Clinical usefulness of the “GeneSoC® SARS-CoV-2 N2 Detection Kit”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Adequate cefazolin therapy for critically ill patients: can we predict active concentrations from given protein-binding data?

- Fully automated chemiluminescence microarray immunoassay for detection of antinuclear antibodies in systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases

- Evaluation of a Treponema IgG ELISA alone and in combination with an IgM ELISA as substitutes for Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) as confirmatory tests in a two-tier diagnostic algorithm for diagnosis of syphilis infection

- Research on the stability changes in expert consensus of the ACTH detection preprocessing scheme

- Female patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)-associated antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) have a lower ovarian reserve than either primary APS or SLE patients

- Short Communication

- Clinical usefulness of the “GeneSoC® SARS-CoV-2 N2 Detection Kit”