Abstract

Objectives

Unidentified SARS-CoV-2 infections among hospital staff can become a major burden for healthcare systems worldwide. We hypothesized that the number of previous SARS-CoV-2 infections among hospital employees is substantially higher than known on the basis of direct testing strategies. A serological study was thus performed among staff of Marburg University Hospital, Germany, in May and June 2020.

Methods

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers were measured by spike protein (S1)-specific IgG ELISA (Euroimmun) and by nucleoprotein-(NCP) specific total antibody CLIA (Roche). Selected sera were analyzed by SARS-CoV-2 neutralization test. Participants provided questionnaires regarding occupational, medical, and clinical items. Data for 3,623 individuals (74.7% of all employees) were collected.

Results

Individuals reactive to both S1 and NCP were defined as seropositive; all of those were confirmed by neutralization test (n=13). Eighty-nine samples were reactive in only one assay, and 3,521 were seronegative. The seroprevalence among hospital employees at Marburg University Hospital was 0.36% (13/3,623). Only five of the 13 seropositive employees had reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test result.

Conclusions

Usage of a single S1-specific assay highly overestimated seroprevalence. The data provided no evidence for an increased risk for a SARS-CoV-2 infection for staff involved in patient care compared to staff not involved in patient care.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic imposes a major burden on health care systems worldwide. There are major concerns among healthcare professionals, who are critical in pandemic management, that their exposure to SARS-CoV-2 positive patients is associated with an increased risk for a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Wards and even hospitals can be placed under quarantine when a large proportion of staff becomes infected. Also, it is not known if the testing strategies in place identify all SARS-CoV-2 infections in hospitals. Since many professions with variable contact to COVID-19 patients interact in hospitals and use different personal protection, both professional and non-professional transmissions may constitute major risks for local outbreaks of COVID-19 in hospitals. It is therefore important to study risk factors for a SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare professionals.

This prevalence study was performed at Marburg University Hospital, Germany, which is located in a semi-rural area of the state of Hesse, 100 km north of Frankfurt/Main. The study was conducted from May 28 to June 19 2020, at a time when the first SARS-CoV-2 infection wave was just over and results were not yet confounded by vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Until the study start on May 28 2020, the district (Landkreis Marburg-Biedenkopf with about 246,000 inhabitants) had registered a total number of 211 SARS-CoV-2 infections (source: https://www.marburg-biedenkopf.de/soziales_und_gesundheit/corona/Aktuelle-Corona-Zahlen.php, accessed on Nov 5th, 2020) resulting in a prevalence of reported SARS-CoV-2 cases of about 0.09%. Thirty-two patients had been treated at Marburg University Hospital, 13 of them had received invasive or non-invasive ventilation under intensive care conditions, and six patients died until June 19 2020.

Most available seroprevalence studies in healthcare professionals have analyzed several hundred participants, including studies from Germany, e.g. from Munich [1], Hannover [2] or Essen [3]. Only few studies with more than 2,000 participants are available, some of them spanning several hospitals, e.g. from central Denmark [4], Northern Italy [5] or the New York City area [6]. The reported overall sero-prevalence among healthcare professionals assessed towards the end of the first COVID-19 wave (April 2020) ranged between 1.6% in Germany [3] and 24.4% in the UK [7].

Inhouse [8] and commercial tests in ELISA [3], chemiluminescence [5] and immunochromatographic [9] formats, with specificity for the spike (S) or the nucleoprotein (NCP) proteins, have been utilized to assess seroprevalence among health care workers. Many cross-sectional studies on SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence have relied on one single immunoassay, e.g. S1 IgG ELISA [3], with some exceptions [5, 8]. To avoid overestimations, especially when the prevalence is low, usage of sero-assays with limited specificity thus require a longitudinal approach to demonstrate seroconversion in the same individual [1] or confirmatory assays. For the present study, we chose a two-assay strategy. To our knowledge, this is the first sero-prevalence study in Germany using this approach.

While the occupational exposure to COVID-19 patients is one of the obvious potential sources of infection spread in a hospital environment, the infection may alternatively be introduced after non-occupational transmission of SARS-CoV-2, or transmitted in between employees. If unrecognized, nosocomial transmission to colleagues and non-immune patients becomes a relevant risk. Until the performance of this survey, the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI’s) in place included wearing face masks and keeping distance at work. Outside the hospital, in the private sector, wearing face masks in stores and public transport were mandatory.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Philipps University Marburg, Germany (vote 64/20). The study complies with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki regarding ethical conduct of research involving human subjects.

Sample collection and processing

Before the study start, 6,000 random ID codes (8-digit combinations of four letters and four numbers) were generated. All staff of Marburg University Hospital registered at the human resource department were informed about the upcoming study concomitantly with the monthly salary letter at the end of April 2020. Envelopes containing (1) a questionnaire, (2) the informed consent form, (3) an information sheet and (4) an empty 9 mL serum vial (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). All documents and materials were individualized with the random ID code. After obtaining written informed consent, blood samples were taken by department or Emergency Room staff between May 28 and June 19 2020. Central Laboratory staff recorded the completeness of documentation upon return of samples. Samples arriving with incomplete documentation were excluded and discarded. Blood samples from included participants received a system barcode and were further processed for centrifugation, short-term storage at 2–8 °C and immunoassays (Central Laboratory and Center for in vitro diagnostics/ZIVD). The questionnaires were scanned and processed by the Biostatistics Department. Informed consent sheets were filed by the Central Laboratory.

Immunoassays

The microtitration protocols for the anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgG ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) was established on a Siemens BEP® III plate processor (Siemens Healthcare, Eschborn, Germany). Samples were diluted manually according to the manucfacturer’s instruction, followed by automated washing, conjugate dispensing and reading on Siemens BEP® III. Results were interpreted with a slight modification of the manufacturer’s recommendation (ratio ≤0.8: negative; >0.8, <1.1: equivocal; ≥1.1: positive). Equivocal and positive results were reported as “reactive” in the present study. Total antibodies against the nucleoprotein (NCP) of SARS-CoV-2 were measured using the Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 reagent on a Roche cobas e602 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). As recommended by the manufacturer, numerical values with a cutoff index (COI)<1.0 were regarded as negative, COI≥1.0 as positive (“reactive”).

As confirmatory immunoassay, the receptor-binding domain (RBD)-specific total antibody Wantai test (Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Ent.) was run on the Siemens BEP® III. Specimens with a result of A/C.O.≥1 were regarded as positive, and with A/C.O.<1 as negative, as suggested by the manufacturer. Selected samples were tested by virus neutralization test (NT). The values of the 102 reactive sera are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

SARS-CoV-2 neutralization tests (NT)

SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity of human sera was investigated based on a previously published protocol [10, 11]. Briefly, samples were heat-inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C and serially diluted in 96-well plates starting from a dilution of 1:8. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C together with 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective doses) SARS-CoV-2 (BavPat1/2020 isolate, European Virus Archive Global # 026V-03883). Cytopathic effect (CPE) on VeroE6 cells (Vero C1008, ATCC, Cat#CRL-1586, RRID: CVCL_0574) was analyzed four days post-infection. Neutralization was defined as absence of CPE compared to virus controls. For each test, a positive control (neutralizing COVID-19 patient plasma) was used in duplicates as an inter-assay neutralization standard.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaires

We obtained scanned copies of the questionnaires from 3,626 employees. The answers of the employees were entered into a data base (Microsoft ACCESS) by two persons. In case of inconsistencies or missing answers the datum was marked as “missing”. For each questionnaire the two inputs were compared. In case of discrepancies the questionnaire was reviewed again and a consensus was reached by the two persons who entered the data. Data are summarized in Table 1.

Study population.

| Characteristics | All | Double positive | Single positive | Double negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, years, median (IQR; n) | 42 (29–53; 3604) | 42 (29–51; 13) | 37 (27–55; 89) | 42 (29–53; 3502) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 2,624 (73.15%) | 8 (61.54%) | 56 (62.92%) | 2,560 (73.46%) |

| Male, n (%) | 963 (26.85%) | 5 (38.46%) | 33 (37.08%) | 925 (26.54%) |

| Occupational social history | ||||

| Direct patient care with body contact, n (%) | 2,311 (64.37%) | 8 (61.54%) | 59 (66.29%) | 2,244(64.33%) |

| No direct patient care with body contact, n (%) | 1,279 (35.63%) | 5 (38.46%) | 30 (33.71%) | 1,244 (35.67%) |

| COVID-19-related history | ||||

| Travel since Jan. 2020 to COVID-19 risk country, n (%) | 500 (13.91%) | 2 (15.38%) | 10 (11.24%) | 488 (13.97%) |

| Contact to confirmed COVID-19 cases, n (%) | 595 (16.61%) | 6 (50.00%) | 14 (15.91%) | 575 (16.51%) |

| Contact to suspected COVID-19 cases, n (%) | 1,113 (31.38%) | 5 (50.00%) | 23 (26.74%) | 1085 (31.44%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR pos. test result, n (%) | 12 (0.34%) | 5 (38.46%) | 0 (0.00%) | 7 (0.21%) |

| Antibody test results | ||||

| S1 IgG pos., n (%) | 95 (2.62%) | 13 (100%) | 82 (92.13%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| NCP total ab pos., n (%) | 20 (0.55%) | 13 (100%) | 7 (7.87%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Double pos., n (%) | 13 (0.36%) | 13 (100%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

Linking questionnaires to antibody test results

Each employee obtained a pseudonym, which was used as a code for both the questionnaire and the antibody test results. In very few cases there were non-unique pseudonyms, which were resolved manually. Of the 3,626 pseudonyms in the questionnaires 3,623 matched the pseudonyms in the antibody test results.

We defined employees, who had both a spike protein (S1)-subunit-specific ELISA- and nucleoprotein (NCP)-specific CLIA-positive test result as sero-positive. Employees, who had only one positive test result, were labeled as “reactive”. Employees with two negative test results were labeled seronegative. For one additional comparison, we sub-grouped the seropositive employees into employees who specified that they had a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR result and employees that answered that they had no positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR result (these may include tested employees that had a negative result and participants that were not tested at all). The sero-negative/reactive employees were sub-grouped in the same manner.

Statistical methods

All analyses were conducted in R (version 3.6.3). For each question of the questionnaire we tested for an association between the answers and the seropositives vs. seronegatives or reactives vs. seronegatives using Fisher’s Exact Test implemented in the R package exact2x2 (version 1.6.5). We performed multiple testing corrections using the method from Benjamini and Hochberg (1995).

Results

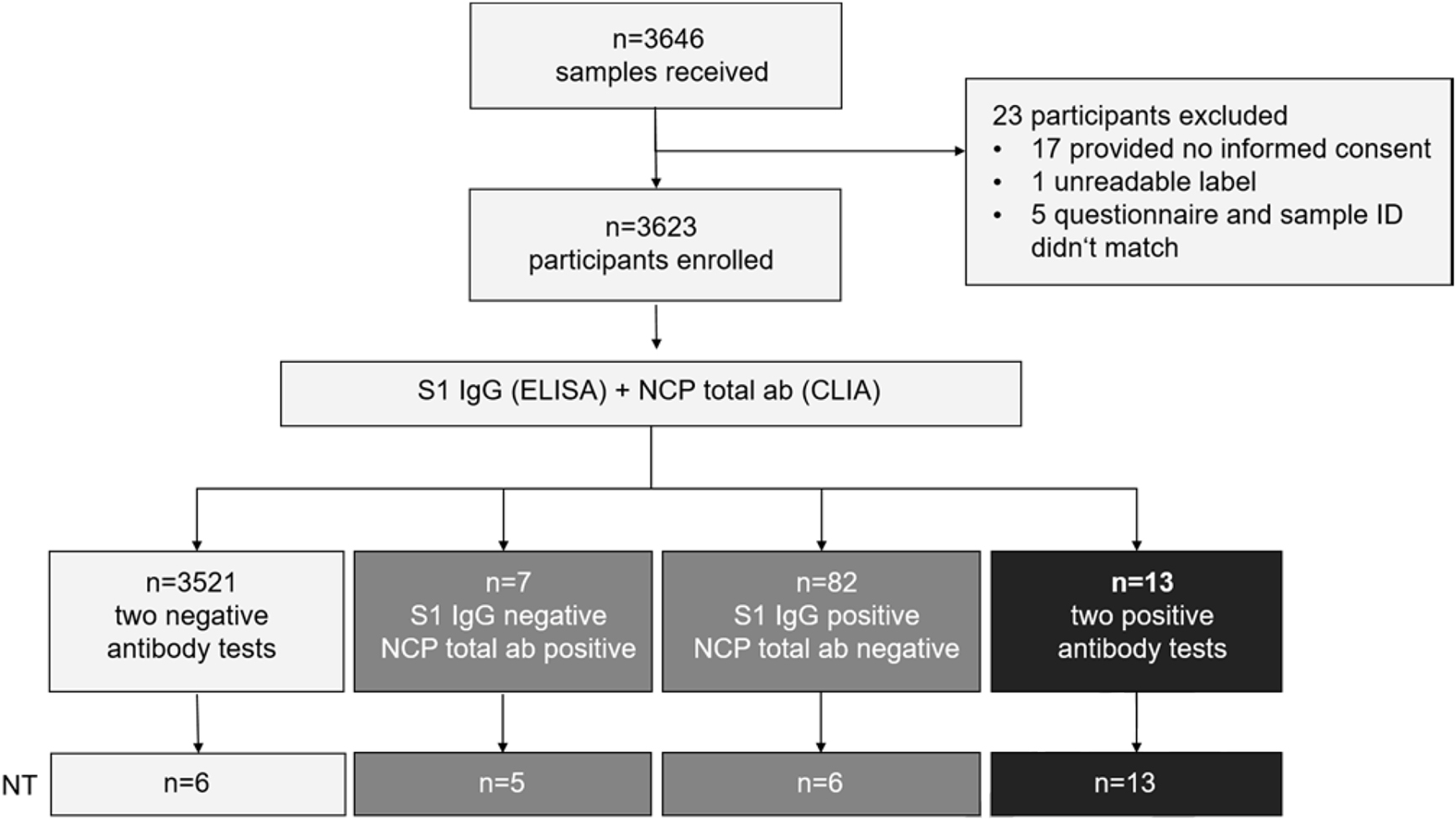

Serum samples were obtained from 3,646 employees. Of those, 17 were excluded from sample processing due a lack of written informed consent, one sample had an unreadable label, and five subjects provided no questionnaire (Figure 1). In total, 3,623 samples were tested in two different immunoassays in order to determine presence of serum antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, a spike protein (S1)-subunit-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Euroimmun) and a nucleoprotein (NCP)-specific chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA, Roche), respectively (Figure 1).

Study design.

From 3,646 subjects submitting samples for the study, 23 were excluded (17 without informed consent, one unreadable sample label, five had no questionnaire). In total, 3,623 participants were enrolled. All samples were tested for spike protein subunit S1-specific IgG by Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S1 IgG ELISA (Euroimmun) and for nucleoprotein (NCP)-specific total antibodies by Anti-SARS-CoV-2 CLIA (Roche). The indicated number of samples from each group was furthermore tested for anti-SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies in VeroE6 cell culture.

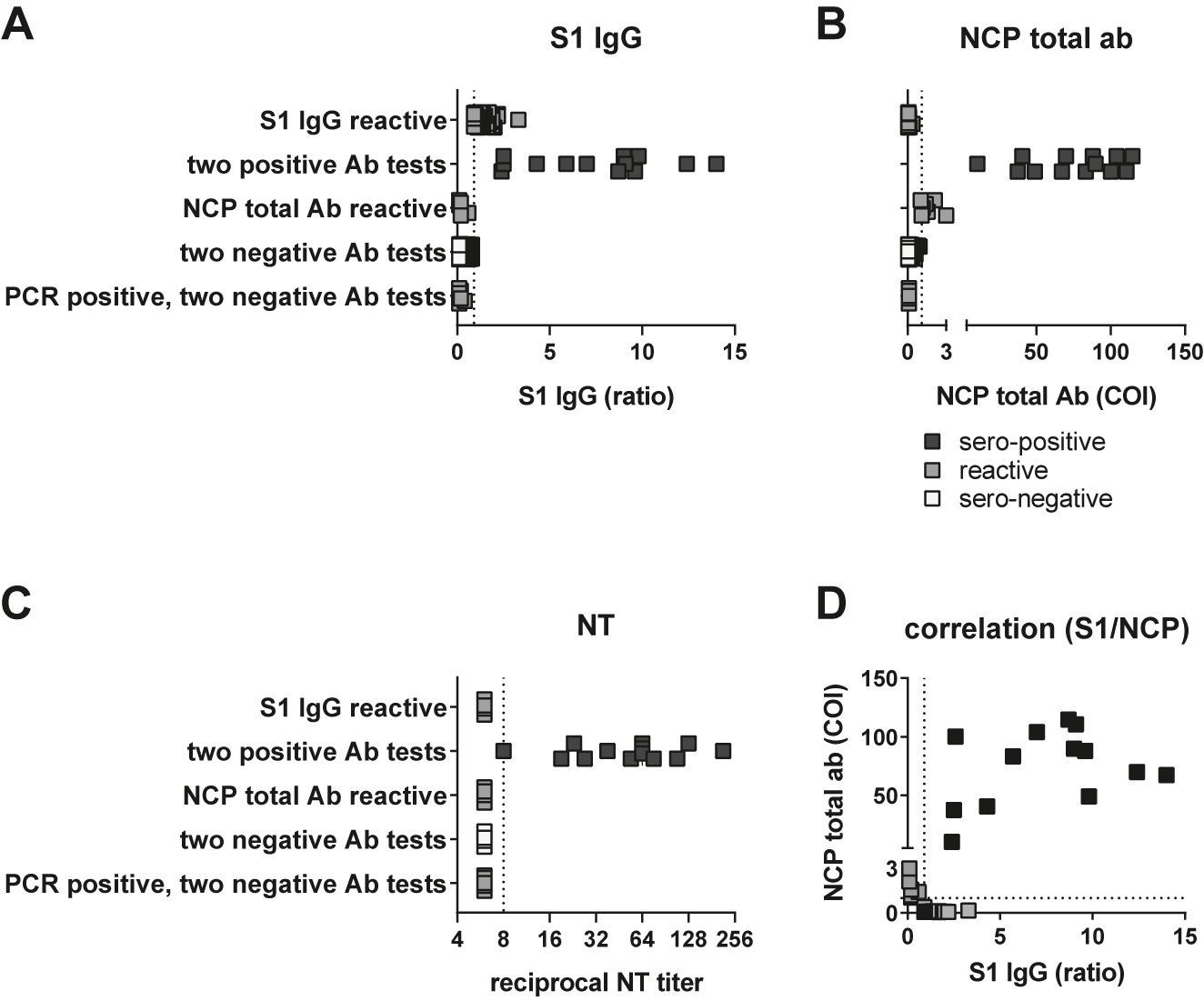

Among the 3,623 tested samples, 95 were reactive in the Euroimmun S1 IgG ELISA (2.62%), and 20 were reactive in the Roche NCP total ab assay (0.55%). 13 sera were positive in both immunoassays (0.36%). Eighty two samples were only reactive in the Euroimmun S1 IgG ELISA, while seven were only reactive in Roche NCP assay, and 3,521 were non-reactive in both antibody tests (Table 1; Figure 2A and B). The ability to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture was confirmed for the 13 double-positive sera with geometric mean titers between 1:8 and 1:215, but neither for the six S1-only reactive sera with the highest S1 IgG ratios in, nor for randomly selected sera from the three other groups (Figure 2C). Our approach thus identified 3,534 (97.5%) concordant and 89 (2.5%) discrepant samples; the concordance between reactive samples is shown in Figure 2D. Of note, seven sera from employees who had reported positive PCR swab results were negative in both immunoassays and by neutralization, suggesting the absence of seroconversion or a decline of the antibody response below the cut-off of both tests (Figure 2A–C). Moreover, only sera from the 13 double-positive participants, but none of the 89 sera reactive only in the S1/NCP assays yielded positive results in the RBD-specific Wantai antibody test. Based on these findings, seroconversion was defined by positivity in both antibody tests, which corresponds to 0.36% of our study population.

Identification of sero-positive participants. (A) Test results in Euroimmun S1 IgG ELISA and (B) Roche NCP total Ab CLIA from 82 sera reactive in S1 ELISA only, 13 sera with two positive Ab tests, seven sera only reactive for NCP total Ab CLIA, 3,524 sera with two negative test results and seven sera from PCR-positive but antibody-negative participants. (C) Reciprocal geometric mean neutralization titers against SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture from six sera reactive in S1 ELISA only, 13 sera with two positive Ab tests, five sera only reactive for NCP total Ab CLIA, six representative sera with two negative test results and seven sera from PCR-positive but antibody-negative participants. (D) Correlation between S1 IgG and NCP total ab results from 82 sera reactive in S1 ELISA only, 13 sera with two positive Ab tests and seven sera only reactive for NCP total Ab CLIA. For each test, dashed lines denote the respective cut-offs.

To check for differences in the sero-conversion rate between employees, who specified an occupation with direct patient contact vs. employees without patient contact (i.e. without any contact to hospitalized patients), we stratified the employees into two groups: 2,311 employees who specified an occupation with direct patient contact (referred to as “patient care group”), and 1,279 employees who specified an occupation without direct patient contact (referred to as “non-patient care group”, Table 1). The sero-prevalence was 0.35% (8 out of 2,311) for the “patient care group” and 0.39% (5 out of 1,279) for the “non-patient care group” (Table 1). The difference of −0.04% is not statistically significant (p-value 0.78; Fisher’s Exact Test). This result remained unchanged even if the 13 double-positive plus the 89 single-positive participants were considered as sero-converters with only one positive Ab test. With this designation, the sero-prevalence reached 2.90% (67 out of 2,311) for the “patient care group” and 2.74% (35 out of 1,279) for the “non-patient care group”. The difference of +0.16% is not statistically significant (p-value 0.83; Fisher’s Exact Test). Finally, if the seven participants, who reported a positive RT-PCR test result, but were sero-negative, were added to the 13 double positive participants to form a group of confirmed subsided SARS-CoV-2 infections, the rate of subsided SARS-CoV-2 infections in the “patient care group” was 0.39% (9 out of 2,311) and 0.86% (11 out of 1,279). Again, the difference of 0.47% is not statistically significant (p-value 0.10; Fisher’s Exact Test). Thus, there is no evidence for a difference in the sero-conversion rate or the rate of subsided SARS-CoV-2 infections between hospital staff involved in patient care vs. staff not involved in patient care. Thus, it remains unclear whether the occupational exposure to hospitalized patients increases the risk for sero-conversion.

When analyzing the age distribution, we could not detect a significant age difference between employees with different antibody status. There was no significant age difference between double-positive and either S1 IgG positive only (p=0.74; Wilcoxon rank sum test), NCP total Ab positive only (p=0.30; Wilcoxon rank sum test), or sero-negative employees (p=0.52; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

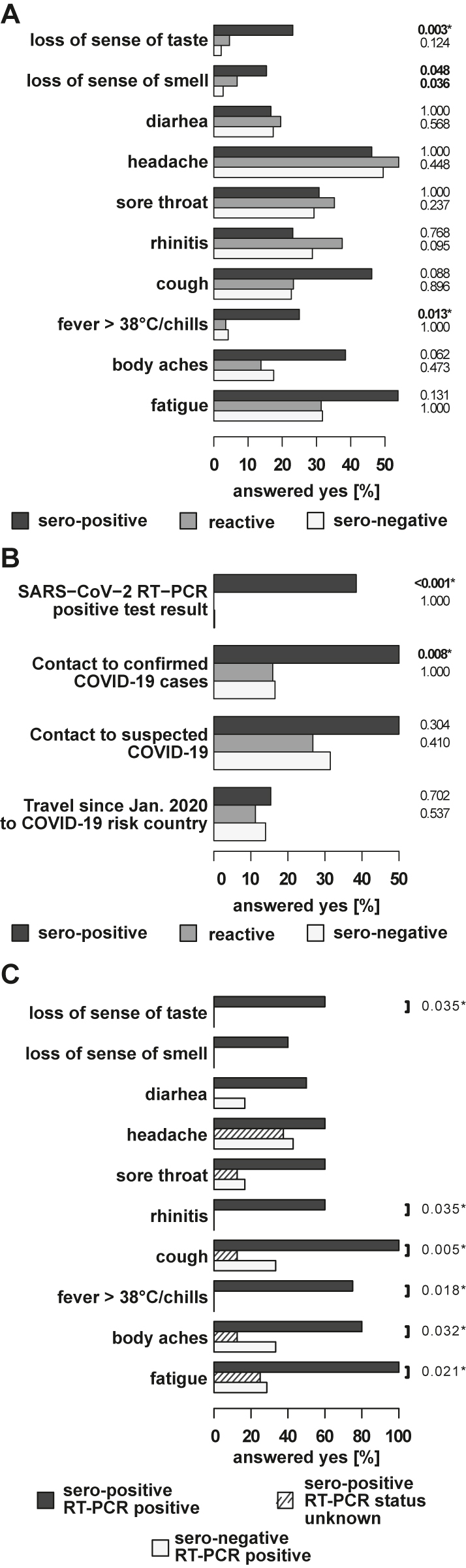

Dividing the participants into three groups (i) sero-negative, both antibody tests negative; (ii) reactive, one of the two antibody tests positive; and (iii) sero-positive, both antibody tests positive) allowed comparing participants with respect to symptoms in the past two months, co-existing disorders and possible risk factors for a SARS-CoV-2 infection (questionnaire items). Sero-positive employees specified significantly more often that they had “fever>38 °C/chills”, “loss of sense of smell”, and a “loss of sense of taste” than the two other groups (Figure 3A). Reactive employees only specified significantly more often that they had a “loss of sense of smell” than sero-negative participants (Figure 3A).

Comparison of reported symptoms and COVID-19 related history items in sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees.

(A) The horizontal bars on the left indicate the percentage of the answer “yes” to the indicated items among the sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees. p-values set in bold indicate a significant difference at a significance level of 5%. p-values additionally marked with an asterisk remain significant after multiple testing correction at a false discovery rate of 10%. Comparison of reported symptoms in sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees. (B) Comparison of COVID-19 related history items in sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees. (C) Comparison of reported symptoms in sero-positive employees with previously positive RT-PCR, sero-positive employees with unknown status and sero-negative RT-PCR positive employees. The horizontal bars indicate the percentage of the answer “yes” to the indicated items. Significant differences between sero-positive employees that specified a positive RT-PCR test result and those that did not specify a positive RT-PCR test result are indicated by the p-values of the Fisher’s Exact Test. p-Values additionally marked with an asterisk remain significant after multiple testing correction at a false discovery rate of 1.

Four risk factors for acquisition of a SARS-CoV-2 infection were assessed in our study (Figure 3B). Sero-positive employees reported with significantly higher frequency previous contacts to confirmed COVID-19 cases or a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test (Figure 3B), but not contact to suspected cases or travel to COVID-19 risk countries, compared to sero-negative employees. None of the investigated risk factors was significantly elevated in the reactive vs. the sero-negative group.

Of the 13 seropositive participants, five reported a positive RT-PCR result, while seven had no knowledge of a previous COVID-19 infection. Among the 13 sero-positive employees, those five with positive SARS CoV-2 RT-PCR results reported significantly more often the symptoms “fatigue”, “body aches”, “fever>38 °C/chills”, “cough”, “rhinitis”, and a “loss of sense of taste” than the eight sero-positive employees with unknown SARS-CoV-2 status (Figure 3C). It thus appears that the latter eight participants had milder forms of the disease that did not prompt confirmation by PCR diagnosis. Taking into account the seven RT-PCR-positive participants without sero-conversion, the ratio between unreported and reported SARS-CoV-2 infections was 1:1.5, i.e. the reported incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections was underestimated by at least 40%.

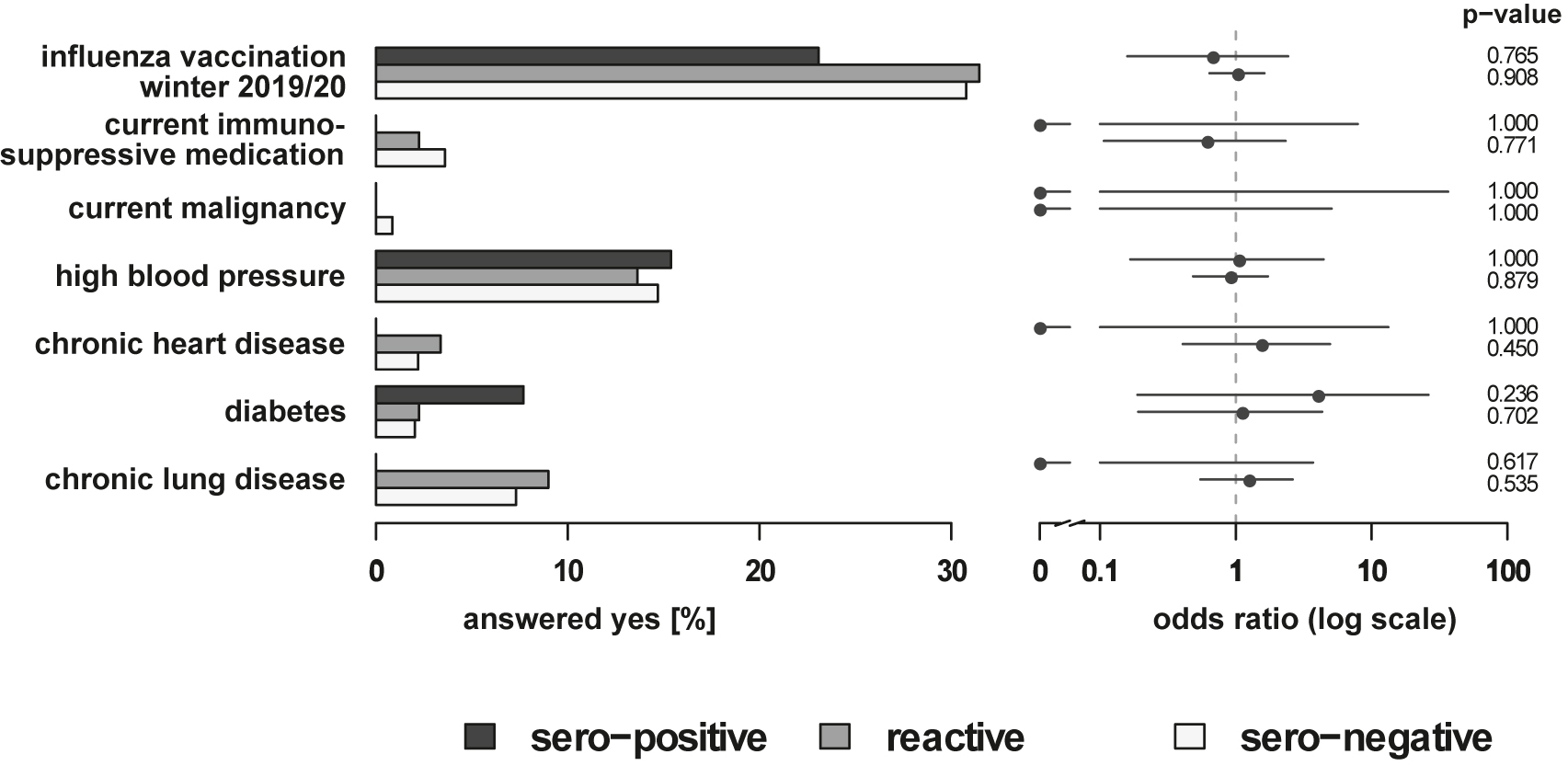

The comparison with respect to co-existing disorders revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups (Figure 4). The frequency of influenza vaccines in the sero-positive group was with 23.1% slightly lower compared to 34.2 and 30.7% in the reactive and sero-negative groups, respectively. Despite a slight tendency, a protective effect of previous influenza vaccination as recently reported [12] could not be confirmed in the present study.

Comparison of preexisting disorder and medical history items in sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees. The horizontal bars on the left indicate the percentage of the answer “yes” to the indicated items among the sero-positive, reactive, and sero-negative employees. The dots on the right indicate the estimated odds ratio between the sero-positive and the sero-negative, and between the reactive and sero-negative employees. The horizontal lines correspond to the respective 95% confidence interval. On the far right the p-values of the Fisher’s Exact Test are given.

Discussion

We report the results of a large cross-sectional seroprevalence study in hospital employees at the end of the first COVID-19 wave in Germany (June 2020). The study was done to identify the rate of SARS-CoV-2 sero-converters that had no knowledge of their previous infection. By using two independent immunoassays, we identified SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies in 13/3,623 participants, corresponding to a seroprevalence of 0.36% in our study population. Eight of these seropositive participants had been unaware of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. This seroprevalence is lower than reported by other comparable studies among healthcare workers from the first COVID-19 wave in Germany [3] (1.6%), Greece [13] (2.2%) or Belgium [14] (11–12%). One important reason for this difference is of methodological nature: several prior studies used only a single immunoassay, often a S1-specific IgG assay [3, 13, 14]. We showed here, by using a two-assay approach, that utilization of the Euroimmun S1 IgG assay as a single test overestimates seroprevalence about sevenfold (2.62% in our population), while the Roche NCP total ab test would have overestimated the seroprevalence by only about 1.5-fold (0.55% in our population). We also demonstrated that S1 single-reactive sera were not confirmed by the more specific Wantai test that detects antibodies against the RBD, and some S1 single-reactive sera that were tested by NT showed no neutralization activity. Using only a single immunoassay, these would have been interpreted as true positives. It is thus likely that previous studies, in the absence of confirmatory tests, have substantially overestimated SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence.

It is questionable whether a potentially low sensitivity of tests could have contributed to this seemingly low sero-prevalence found in our study. The sensitivity is highest >14 days of infection [15]. After 2–4 weeks post infection, sensitivity was reported to range between 89.6 and 96.6% for the Euroimmun S1 IgG ELISA and 95.8–100% for the Roche NCP assay [15, 16]. Serological results depend on the course of COVID-19 infection, since it was observed that 40% of asymptomatic and 12.9% of symptomatic patients become sero-negative within 8 weeks post infection using a combined spike/NCP immunoassay [17]. The sero-negativity of seven patients with previously positive PCR results in our study, potentially related to mild infection with lower viral loads, would constitute 35% (7/20) of all people identified by history or serology, which is consistent with these previous observations. Negative S1 IgG serology does not necessarily indicate an absence of memory responses, since it was shown that 16% of PCR-positive individuals have detectable SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses at 4 months post infection [18]. Given that the survey was conducted within about 3 months of the first wave, it is unlikely that a substantial proportion of positive individuals were overlooked.

We observed no increased risk for a SARS-CoV-2 infection due to direct patient contact. However, our results do not imply that there is no difference in the sero-conversion rate between the “patient care group” and the “non-patient care group”, but rather that a significance difference could not be detected. Most likely, this relates to the relatively small case numbers during the first COVID-19 wave at Marburg University Hospital and the

Small group of sero-positive employees, which reduces the statistical power. Internationally, some reports have demonstrated an increased risk for staff with direct patient contact, e.g. from the UK [19, 20]. Contrarily, several US studies recently showed that community factors may be more important determinants of sero-positivity among healthcare workers than workplace factors [21, 22]. Since we confirmed contact to COVID-19 cases as a risk factor for sero-positivity, these encounters are more likely private or community contacts rather than patient contacts. Of note, some hospitals have even reported a lower rate of sero-positivity in employees working in intensive care [7].

While we found no systematic influence of age on sero-positivity, several studies from the UK and the US showed that healthcare workers younger than 30 years may have a higher risk for sero-conversion [20], [21], [22]. Again, the small number of seropositive staff in our study may reduce statistical power required to find a significant correlation with age.

Female study participants were highly overrepresented in our study. In hospital setting, many employees are nurses, midwives etc., the majority of which are female. This has led to a similar female bias also in other hospital seroprevalence studies [2, 3, 22].

As another limitation, we cannot rule out that the single reactive group contained true-positive sero-converters, e.g. after decline of NCP-specific IgG while spike-specific responses were still detectable. It is, however, unlikely that a potentially rapid decline has influenced the study result: Recently, a study from Wuhan suggested a rather stable IgG response against NCP, with 90% of COVID-19 patients having detectable NCP-specific IgG after 6–9 months post infection [23]. Other studies have suggested a more accelerated decline of NCP-specific compared to spike-specific IgG, but over a time span of several months: Dan et al. calculated the half-life of IgG against spike to be 103 vs. 69 days for IgG against RBD and 68 days for NCP-specific IgG [24]. Another study found a half-life of 283 days for NCP-specific IgG and 725 days for RBD-specific IgG [25]. Our study was conducted not more than three months after the beginning of the first wave, making a substantial NCP-specific decline unlikely. Moreover, all S1-reactive sera were tested in the highly sensitive and specific Wantai assay that detects antibodies against the RBD of the S1 subunit [26]. Of the 89 samples sera reactive in only one test, none were positive in this RBD assay, while all 13 S1-/NCP-reactive sera were confirmed. Finally, the specificity of the Euroimmun S1 IgG test in larger panels is only 86.3–96.4% [15], which is lower than initially reported [27]. Assuming a specificity of 96.4%, the expected number of false-positives among 3,623 participants would be n=126, so the 82 S1-reactive samples are within the expected range of false positives of the S1 IgG test. In sum, it is therefore likely that the 82 S1-reactive, NCP-negative samples are really cross-reactive sera rather than missed COVID-19 patients.

With an amino acid identity among human common cold coronaviruses of only 21–25%, the immunological basis for S1 cross-reactivity in non-COVID-19 patients remains elusive: In some cases, sera from patients diagnosed with e.g. hCoV OC43 may be reactive in SARS-CoV-2 S1 immunoassays [27]. Within the S protein, the majority of cross-reactive epitopes are located in the S2 subunit, some contributing to neutralizing function, but some are found within S1. Given the high prevalence of anti-hCoV antibodies in humans, it was suggested that the rarity of cross-reactive S-specific antibodies has additional requirements such as random B cell repertoire focusing of frequency of infections [28].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this is one of the largest seroprevalence studies among healthcare professionals in hospitals carried out so far. The use of two antibody tests dramatically increased the precision of the designation as seropositive as demonstrated by the validation by the SARS-CoV-2 neutralization test. The sero-prevalence among employees of Marburg University Hospital was about 0.36% in June 2020. The results highlight that the usage of singular, especially S1-directed assays with low specificity, such as in some previous reports, may overestimate the seroprevalence. The data provide no evidence for a difference in the seroconversion rate or the rate of subsided SARS-CoV-2 infections between participants with frequent patient contact vs. those without patient contact. Thus, it remains unclear whether the frequent contact to SARS-CoV-2 infected patients represents a risk factor. The low seroprevalence among the employees of Marburg University Hospital indicates that it had been spared from a local outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infections. This may be attributable to the hygiene measures in action at the hospital. However, since our study emphasizes that non-occupational transmission occurs among all professional groups within the hospital, future hygiene concepts need to encompass also areas not directly related to patient care. Finally, the data suggests that the ratio between unreported and reported SARS-CoV-2 infection may be around 1:1.5 implying that the true prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections may be underestimated by at least 40%.

Funding source: German Center for Lung Research (DZL) doi:10.13039/501100010564

Award Identifier / Grant number: 82DZL00502

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Petra Fischer, Tillman Görg and especially Karin Zamzow for their support in inputting the questionnaires into a database. We also thank Kirsten Volland and Alexandra Fischer for excellent technical assistance. We are very grateful to all 3,646 participants in this study.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Universities Giessen Marburg Lung Center and the German Center for Lung Disease (DZL German Lung Center, No. 82DZL00502) for UGMLC.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Dr. Keller reports membership in the Robert Koch Institute Expert Panel on Pandemic Respiratory Infections and a lecture honorarium from Roche, unrelated to the present work.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The local Institutional Review Board approved this study under vote #64/20.

References

1. Weinberger, T, Steffen, J, Osterman, A, Mueller, TT, Muenchhoff, M, Wratil, PR, et al.. Prospective longitudinal serosurvey of health care workers in the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in a quaternary care hospital in Munich, Germany. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e3055–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1935.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Behrens, GMN, Cossmann, A, Stankov, MV, Witte, T, Ernst, D, Happle, C, et al.. Perceived versus proven SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses in health-care professionals. Infection 2020;48:631–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01461-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Korth, J, Wilde, B, Dolff, S, Anastasiou, OE, Krawczyk, A, Jahn, M, et al.. SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody detection in healthcare workers in Germany with direct contact to COVID-19 patients. J Clin Virol 2020;128:104437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104437.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Jespersen, S, Mikkelsen, S, Greve, T, Kaspersen, KA, Tolstrup, M, Boldsen, JK, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence survey among 17,971 healthcare and administrative personnel at hospitals, pre-hospital services, and specialist practitioners in the Central Denmark Region. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e2853–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1471.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Plebani, M, Padoan, A, Fedeli, U, Schievano, E, Vecchiato, E, Lippi, G, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey in health care workers of the Veneto Region. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:2107–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-1236.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Moscola, J, Sembajwe, G, Jarrett, M, Farber, B, Chang, T, McGinn, T, et al.. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in health care personnel in the New York City area. J Am Med Assoc 2020;324:893–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.14765.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Shields, A, Faustini, SE, Perez-Toledo, M, Jossi, S, Aldera, E, Allen, JD, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and asymptomatic viral carriage in healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Thorax 2020;75:1089–94. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215414.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Rudberg, A-S, Havervall, S, Månberg, A, Jernbom Falk, A, Aguilera, K, Ng, H, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 exposure, symptoms and seroprevalence in healthcare workers in Sweden. Nat Commun 2020;11:5064. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18848-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Dacosta-Urbieta, A, Rivero-Calle, I, Pardo-Seco, J, Redondo-Collazo, L, Salas, A, Gómez-Rial, J, et al.. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among pediatric healthcare workers in Spain. Front Pediatr 2020;8:547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.00547.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Kreer, C, Zehner, M, Weber, T, Ercanoglu, MS, Gieselmann, L, Rohde, C, et al.. Longitudinal isolation of potent Near-germline SARS-CoV-2-neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients. Cell 2020;182:843–54e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Folegatti, PM, Ewer, KJ, Aley, PK, Angus, B, Becker, S, Belij-Rammerstorfer, S, et al.. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020;396:467–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31604-4.Search in Google Scholar

12. Debisarun, PA, Gössling, KL, Bulut, O, Kilic, G, Zoodsma, M, Liu, Z, et al.. Induction of trained immunity by influenza vaccination - impact on COVID-19. PLoS Pathog 2021;17:e1009928. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009928.Search in Google Scholar

13. Vlachoyiannopoulos, P, Alexopoulos, H, Apostolidi, I, Bitzogli, K, Barba, C, Athanasopoulou, E, et al.. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection in healthcare workers of two tertiary hospitals in Athens, Greece. Clin Immunol 2020;221:108619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108619.Search in Google Scholar

14. Martin, C, Montesinos, I, Dauby, N, Gilles, C, Dahma, H, van den Wijngaert, S, et al.. Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR positivity and seroprevalence among high-risk healthcare workers and hospital staff. J Hosp Infect 2020;106:102–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.06.028.Search in Google Scholar

15. Manthei, DM, Whalen, JF, Schroeder, LF, Sinay, AM, Li, S-H, Valdez, R, et al.. Differences in performance Characteristics among four high-throughput assays for the detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using a common set of patient samples. Am J Clin Pathol 2021;155:267–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa200.Search in Google Scholar

16. Schnurra, C, Reiners, N, Biemann, R, Kaiser, T, Trawinski, H, Jassoy, C. Comparison of the diagnostic sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein and glycoprotein-based antibody tests. J Clin Virol 2020;129:104544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104544.Search in Google Scholar

17. Long, Q-X, Liu, B-Z, Deng, H-J, Wu, G-C, Deng, K, Chen, Y-K, et al.. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:845–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1.Search in Google Scholar

18. Reynolds, CJ, Swadling, L, Gibbons, JM, Pade, C, Jensen, MP, Diniz, MO, et al.. Discordant neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in asymptomatic and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol 2020;5:eabf3698. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abf3698.Search in Google Scholar

19. Nguyen, LH, Drew, DA, Graham, MS, Joshi, AD, Guo, C-G, Ma, W, et al.. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e475–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X.Search in Google Scholar

20. Houlihan, CF, Vora, N, Byrne, T, Lewer, D, Kelly, G, Heaney, J, et al.. Pandemic peak SARS-CoV-2 infection and seroconversion rates in London frontline health-care workers. Lancet 2020;396:e6–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31484-7.Search in Google Scholar

21. Damluji, AA, Wei, S, Bruce, SA, Haymond, A, Petricoin, EF, Liotta, L, et al.. Seropositivity of COVID-19 among asymptomatic healthcare workers: a multi-site prospective cohort study from Northern Virginia, United States. Lancet Reg Health Am 2021;2:100030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2021.100030.Search in Google Scholar

22. Jacob, JT, Baker, JM, Fridkin, SK, Lopman, BA, Steinberg, JP, Christenson, RH, et al.. Risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among US health care personnel. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e211283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1283.Search in Google Scholar

23. He, Z, Ren, L, Yang, J, Guo, L, Feng, L, Ma, C, et al.. Seroprevalence and humoral immune durability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal, population-level, cross-sectional study. Lancet 2021;397:1075–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00238-5.Search in Google Scholar

24. Dan, JM, Mateus, J, Kato, Y, Hastie, KM, Yu, ED, Faliti, CE, et al.. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021;371:eabf4063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf4063.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Gallais, F, Gantner, P, Bruel, T, Velay, A, Planas, D, Wendling, M-J, et al.. Evolution of antibody responses up to 13 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of reinfection. EBioMedicine 2021;71:103561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103561.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Lassaunière, R, Frische, A, Harboe, ZB, Nielsen, ACY, Fomsgaard, A, Krogfelt, KA, et al.. Evaluation of nine commercial SARS-CoV-2 immunoassays. MedRxiv 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325.10.1101/2020.04.09.20056325Search in Google Scholar

27. Okba, NM, Müller, MA, Li, W, Wang, C, GeurtsvanKessel, CH, Corman, VM, et al.. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2−specific antibody responses in Coronavirus disease patients. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:1478–88. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200841.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Ng, KW, Faulkner, N, Cornish, GH, Rosa, A, Harvey, R, Hussain, S, et al.. Preexisting and de novo humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Science 2020;370:1339–43. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe1107.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/labmed-2021-0107).

© 2021 Christian Keller et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary

- In Memoriam of Beniam Ghebremedhin

- Review

- New and emerging technologies for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections

- Original Articles

- Blood indices and circulating tumor cells for predicting metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation

- Comparison of APACHE II scores and mortality with CRP/albumin, neutrophil/lymphocyte and thrombocyte/lymphocyte ratios in patients admitted to internal medicine and anesthesia reanimation intensive care unit

- The correlation between the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal age in Southern China

- The investigation of serum protein profiles in anal fistula for potential biomarkers

- Evaluation of antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of ethanolic extracts of Polygonum senticosum in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages

- Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in hospital employees, Central Germany

- Fast forward evolution in real time: the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern lineage B.1.1.7 in Saxony-Anhalt over a period of 5 months

- Letters to the Editor

- It did not stop there: rapid substitution of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern B.1.1.7 (Alpha) by variant of concern B.1.617.2 (Delta) and further evolution of different Delta sublineages in Southern Saxony-Anhalt in late summer 2021

- In reply to a review article “Review of potentials and limitations of indirect approaches for estimating reference limits/intervals of quantitative procedures in laboratory medicine”

- Reply to the letter of Katayev and Fleming

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary

- In Memoriam of Beniam Ghebremedhin

- Review

- New and emerging technologies for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections

- Original Articles

- Blood indices and circulating tumor cells for predicting metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation

- Comparison of APACHE II scores and mortality with CRP/albumin, neutrophil/lymphocyte and thrombocyte/lymphocyte ratios in patients admitted to internal medicine and anesthesia reanimation intensive care unit

- The correlation between the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal age in Southern China

- The investigation of serum protein profiles in anal fistula for potential biomarkers

- Evaluation of antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of ethanolic extracts of Polygonum senticosum in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages

- Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in hospital employees, Central Germany

- Fast forward evolution in real time: the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern lineage B.1.1.7 in Saxony-Anhalt over a period of 5 months

- Letters to the Editor

- It did not stop there: rapid substitution of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern B.1.1.7 (Alpha) by variant of concern B.1.617.2 (Delta) and further evolution of different Delta sublineages in Southern Saxony-Anhalt in late summer 2021

- In reply to a review article “Review of potentials and limitations of indirect approaches for estimating reference limits/intervals of quantitative procedures in laboratory medicine”

- Reply to the letter of Katayev and Fleming