Seroprevalence and geographical distribution of hepatitis C virus in Iranian patients with thalassemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

-

Amir Shamshirian

, Reza Alizadeh-Navaei

Abstract

Background

Thalassemia as a hereditary hemoglobinopathy is the most common monogenic disease worldwide. Patients with thalassemia require regular blood transfusion, which provides the risk for the transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) as the most common post-transfusion infection in such patients, and this rate is very diverse in different parts of the world. We aimed to determine the prevalence of HCV among patients with thalassemia in Iran.

Methods

In this study, we searched for articles on the prevalence of HCV among Iranian thalassemia patients in English and Persian databases up to 2017. Heterogeneities were assessed by using an I-square (I2) test. Prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using the random effects model.

Results

In total, 37 studies with 9185 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The prevalence of HCV among Iranian thalassemia patients was 17.0% (95% CI: 14.5–19.8). The rate of prevalence among male and female subjects was 17.4% (95% CI: 13.8–21.9) and 16.8% (95% CI: 13.2–21.1), respectively.

Conclusions

We found that the prevalence of HCV among Iranian thalassemia patients declined over time and the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization has had a reasonable performance in HCV screening.

Reviewed Publication:

Ahmad-Nejad Parviz Ghebremedhin Beniam Edited by:

Background

Thalassemia, the most common human monogenic disease worldwide is caused by mutations in globin genes related to the lack or reduced production of α- or β-globin chains [1]. Thalassemia patients have various degrees of anemia from mild to intrauterine death that requires different plans for blood transfusion [2]. Moreover, it is interesting to note that, β-thalassemia being homozygous causes the main clinical problems [3], [4], [5]. The prevalence of thalassemia in populations of the Mediterranean region and the Middle East, is significantly high. Annually worldwide, about 56,000 β-thalassemia major cases are identified or born, of which, more than 50,000 are the newborns and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 30,000 of whom need the regular blood transfusions [1], [2], [6].

Thalassemia is one of the most important health problems in Iran, because it is located in the central part of the region that is called “The Thalassemia Belt”. Studies indicate that there are more than 25,000 cases of thalassemia major in Iran [7], [8].

Given that the majority of patients with severe thalassemia need regular blood transfusions, the risk of transmission of viral infections is greater than in healthy individuals. The most common post-transfusion infection is hepatitis C virus (HCV), a single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family that may cause chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. According to the WHO, about 3% (170 million people) of the population in the world are infected with this infection [9], [10], [11]. Studies on the prevalance of this infection in patients with β-thalassemia revealed an occurrence from 3% to 67.3% [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

The prevalence of HCV infection in thalassemia patients is reported from 2 to 32% in Iran. However, it is somewhat interesting to note that these screening studies do not give us a clear picture and they do not provide comprehensive information that can be generalized to society. Moreover, the different indicators in various studies have different effects. The reasons for these differences are unknown; probably, regional differences, sampling, time and duration of screening, and factors involved in data analysis play a major role in these research gaps. Besides, most studies were performed on a small number of patients that can indicate the reasons for differences in the studies. The objective of this study is to use meta-analysis for the regularization of numerical data reported in previous studies on the prevalence of HCV in patients with thalassemia to overcome the limitations of these studies.

Methods

Search strategy

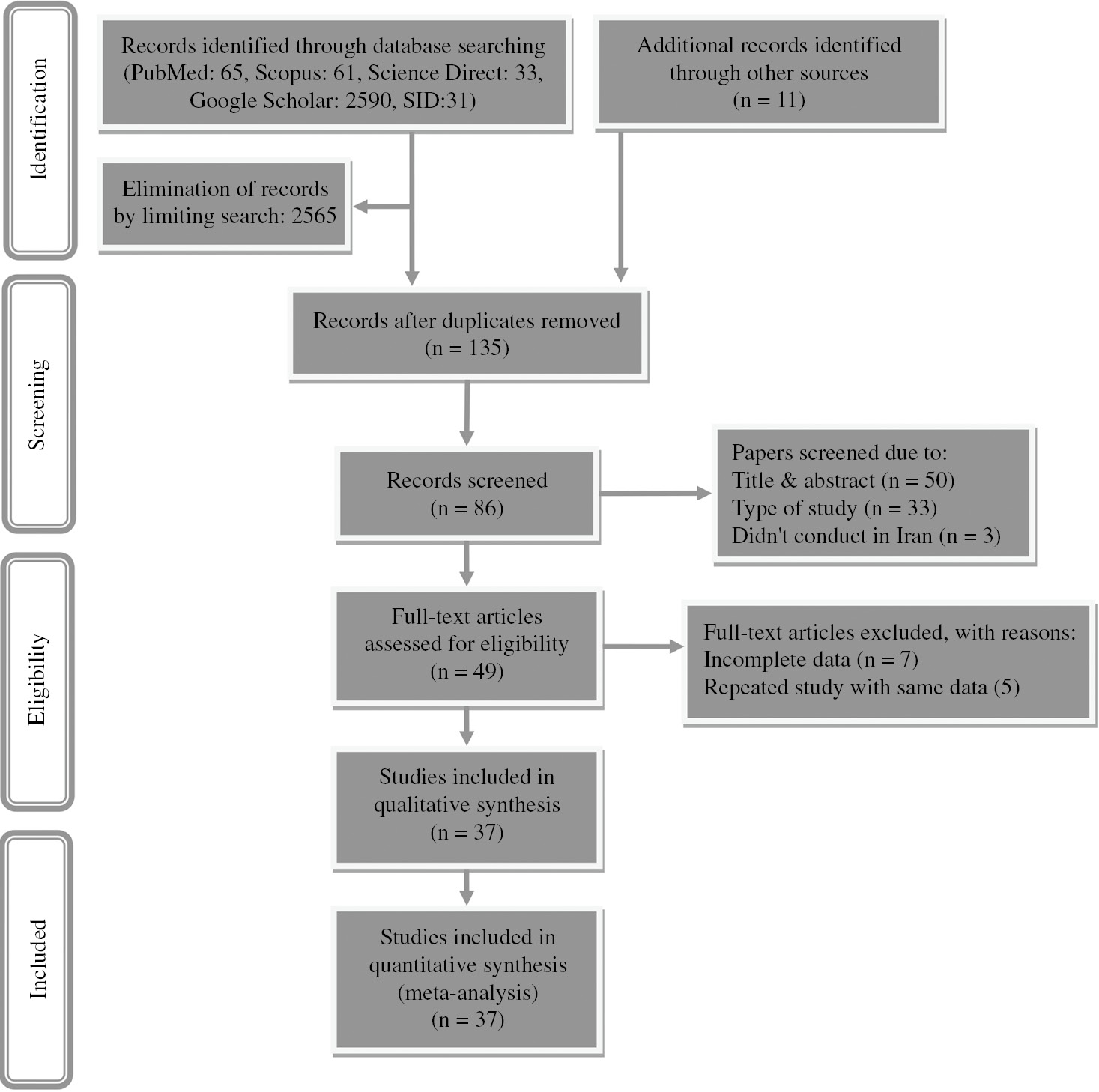

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was used to design, analyze and report the obtained data. We conducted a systematic search for the relevant articles from March 21 to April 9, 2017 using the databases of PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar (searched in title) and Scientific Information Database (SID) (all fields) and the Science Direct website, which together cover all medical journals and other publications related to the topic.

The search process was done by two researchers using the following keywords: intervention (“HCV” OR “Hepatitis C Virus”) AND (“Anti-HCV” OR “Anti-HCV Antibodies” OR “Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Antibodies”) AND “Thalassemia” AND “Prevalence” AND “Iran”. The search strategy included both English and Persian articles. Moreover, we used the references of collected studies to find data that may not have been found in our search.

Criteria for including studies

All papers, which included the mentioned keywords were screened by two researchers and selected papers were scanned by checking the title and abstract for inclusion or exclusion from the study. Inclusion criteria of our study were all observational research published in English or Persian that reported the prevalence of HCV based on HCV antibody immunoassay among patients with thalassemia in different parts of Iran. Exclusion criteria included papers that were not conducted in Iran, were not done on patients with thalassemia, and did not report the prevalence of HCV and studies that had incomplete data for any reason.

To extract data from the papers, we designed a checklist including author names, study region, date, the number of patients, the number and percentage of males and females, the mean age of cases the prevalence of positive anti-HCV.

At the end of the search, 215 papers were obtained. Of them, 50 papers were irrelevant to the topic, 80 studies were duplicated by checking titles and abstracts, three papers were not conducted in Iran, 33 papers were not original studies, the data from seven studies were incomplete, and in five studies the same data were repeated. Finally, 37 papers were included into current meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Two members of our team independently valued the selected articles using the standard 22-item Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist in relation to various aspects of methodology and study process [17]. The supervisor of the study solved any disagreements. A score between 0 and 7 was considered low quality (C), 8 and 14 as moderate (B), and 15 and 22 as high quality (A).

Data analysis

In this study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of HCV among Iranian patients with thalassemia. All statistical analyses were done using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2.2.064 (CMA) [18]. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Heterogeneities were evaluated using an I-square (I2) test [19]. Because of significant heterogeneity calculated for results, the random effects model, which takes the diversity of the studies into account was used [20].

Results

Information from studies included into the meta-analysis

In this systematic review, 215 papers were identified and retrieved from the databases and after the final evaluation, 37 papers passed through the checklist, and the full text of the papers was assessed. The PRISMA Flow Diagram of search strategy is shown in Figure 1. The final studies were published during the years 2000–2017, and a total of 9185 individuals participated in these studies. A summary of the information provided by the studies is presented in Table 1.

PRISMA flowchart for search strategy and study selection.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis after complete evaluation.

| Study | Reference | Publication year | Study period | Region | NP | Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Age, mean, years | Anti-HCV+ n, (%) | STROBE score (classification)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vahidi et al. | [21] | 2000 | 1996 | Kerman | 107 | 59 (54.90) | 48 (44.80) | 9.24 | 24 (22.40) | 17(A) |

| Najafi et al. | [22] | 2001 | 1998 | Mazandaran | 100 | 49 (49.00) | 51 (51.00) | 11.96 | 18 (18.00) | 12(B) |

| Basirat nia | [23] | 2001 | 1999 | Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 113 | 63 (55.70) | 50 (44.30) | NR | 26 (23.00) | 12(B) |

| Karimi and Ghavanini | [24] | 2001 | 1999–2000 | Fars | 466 | 243 (52.10) | 223 (47.90) | 11.70 | 73 (15.70) | 15(A) |

| Nakhaie and Talachian | [25] | 2003 | 1999–2000 | Tehran | 507 | NR | NR | NR | 122 (24.00) | 13(B) |

| Sanei Moghaddam et al. | [26] | 2004 | 2002 | Sistan and Baluchestan | 364 | 206 (56.60) | 158 (43.40) | 9.7 | 49 (13.46) | 13(B) |

| Alavi et al. | [27] | 2005 | 2002 | Tehran | 110 | 55 (50.00) | 55 (50.00) | 11.50 | 13 (11.80) | 12(B) |

| Faranoush et al. | [28] | 2005 | 2002 | Semnan | 63 | 40 (60.40) | 23 (39.60) | 11.80 | 25 (39.60) | 13(B) |

| Torabi et al. | [29] | 2005 | 2003 | East Azerbaijan | 84 | 50 (59.50) | 34 (40.50) | 11.50 | 6 (7.10) | 12(B) |

| Javadzadeh et al. | [30] | 2006 | 2003 | Yazd | 85 | 41 (48.20) | 44 (51.80) | 12.60 | 8 (9.40) | 15(A) |

| Mirmomen et al. | [31] | 2006 | 2002 | Multicenterb | 732 | 413 (56.40) | 319 (43.60) | 17.90 | 141 (19.20) | 13(B) |

| Ghafourian et al. | [32] | 2006 | 1999–2004 | Khuzestan | 122 | 73 (59.80) | 49 (40.20) | 14.96 | 32 (26.20) | 16(A) |

| Ansari et al. | [33] | 2007 | 2005–2006 | Fars | 806 | 406 (50.40) | 400 (49.60) | 15.3 | 116 (14.40) | 15(A) |

| Company et al. | [34] | 2007 | 2005–2006 | Khuzestan | 195 | 98 (50.25) | 197 (49.75) | 14.97 | 40 (20.50) | 16(A) |

| Ahmad et al. | [35] | 2007 | 2003–2004 | Fars | 200 | 100 (50.00) | 100 (50.00) | NR | 50 (25.00) | 15(A) |

| Samimi-Rad and Shahbaz | [36] | 2007 | 2004 | Markazi | 98 | 50 (51.00) | 48 (49.00) | 13.1 | 5 (5.10) | 12(B) |

| Kashef et al. | [37] | 2008 | 2008 | Fars | 131 | 63 (48.10) | 68 (51.90) | 14.6 | 24 (18.32) | 12(B) |

| Arababadi et al. | [38] | 2008 | 2006–2007 | Kerman | 60 | NR | NR | 12.1 | 27 (45.00) | 12(B) |

| Ameli et al. | [39] | 2008 | 2006 | Mazandaran | 65 | NR | NR | 19.51 | 11 (16.90) | 16(A) |

| Mahdaviani et al. | [40] | 2008 | 2004 | Markazi | 97 | 50 (51.50) | 47 (48.50) | 13.1 | 7 (7.20) | 14(B) |

| Bozorgi et al. | [41] | 2008 | 2004 | Qazvin | 207 | 99 (48.30) | 104 (51.70) | 14.29 | 52 (25.10) | 12(B) |

| Hassanshahi et al. | [42] | 2009 | 2006–2007 | Kerman | 181 | 81 (45.10) | 100 (54.90) | 14.5 | 81 (44.80) | 18(A) |

| Azarkar et al. | [43] | 2009 | 2007 | South Khorasan | 38 | 21 (54.10) | 17 (45.90) | 9.2 | 0 (0.00) | 10(B) |

| Ghafourian et al. | [44] | 2009 | 2006–2007 | Khuzestan | 206 | 97 (47.10) | 109 (52.90) | 18.98 | 58 (28.15) | 12(B) |

| Sammak et al. | [45] | 2010 | 2007 | Qom | 142 | 76 (53.50) | 66 (46.50) | 14.3 | 19 (13.40) | 11(B) |

| Raeisi et al. | [46] | 2011 | 2005 | Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 91 | 41 (45.00) | 50 (55.00) | 13.2 | 19 (21.00) | 10(B) |

| Ghane et al. | [47] | 2011 | 2011 | Multicenterc | 245 | 125 (51.00) | 120 (49.00) | 18.38 | 28 (11.40) | 15(A) |

| Kashanchi et al. | [48] | 2011 | 2009–2010 | Alborz | 206 | 90 (43.70) | 116 (56.30) | 19.64 | 31 (15.00) | 13(B) |

| Kalantari et al. | [49] | 2011 | 2008–2010 | Isfahan | 545 | 312 (57.20) | 233 (42.80) | 18 | 50 (9.10) | 18(B) |

| Azarkeivan et al. | [50] | 2012 | 1996–2009 | Tehran | 395 | 229 (58.00) | 166 (42.00) | 27.5 | 109 (27.60) | 11(B) |

| Alavi et al. | [51] | 2012 | 2011 | Tehran | 90 | 46 (51.10) | 44 (48.90) | 14.1 | 12 (13.30) | 14(B) |

| Ataei et al. | [52] | 2012 | 1996–2011 | Isfahan | 463 | 270 (58.30) | 193 (41.70) | 17.46 | 37 (7.90) | 14(B) |

| Sarkari et al. | [53] | 2012 | 2009–2010 | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | 49 | NR | NR | NR | 3 (6.10) | 16(A) |

| Jafroodi et al. | [8] | 2015 | 2002–2012 | Gilan Province | 1113 | 535 (48.10) | 578 (51.90) | 22.93 | 152 (13.60) | 18(A) |

| Valizadeh et al. | [7] | 2015 | 2014 | West Azerbaijan | 32 | 18 (56.25) | 14 (43.75) | 11.41 | 0 (0.00) | 10(B) |

| Bazi et al. | [54] | 2016 | 2014 | Sistan and Baluchestan | 90 | 46 (51.10) | 44 (48.90) | 14.8 | 9 (10.00) | 11.(B) |

| Aminianfar et al. | [55] | 2017 | 2014–2015 | Hormozgan | 587 | 280 (47.70) | 307 (52.30) | 31 | 60 (10.22) | 15(A) |

NP, number of patient; NR, not reported. aClassification: 0–7(C), 8–14(B), 15–22(A). bTehran, Kerman, Qazvin, Semnan, and Zanjan. cGilan and Mazandaran.

Meta-analysis results

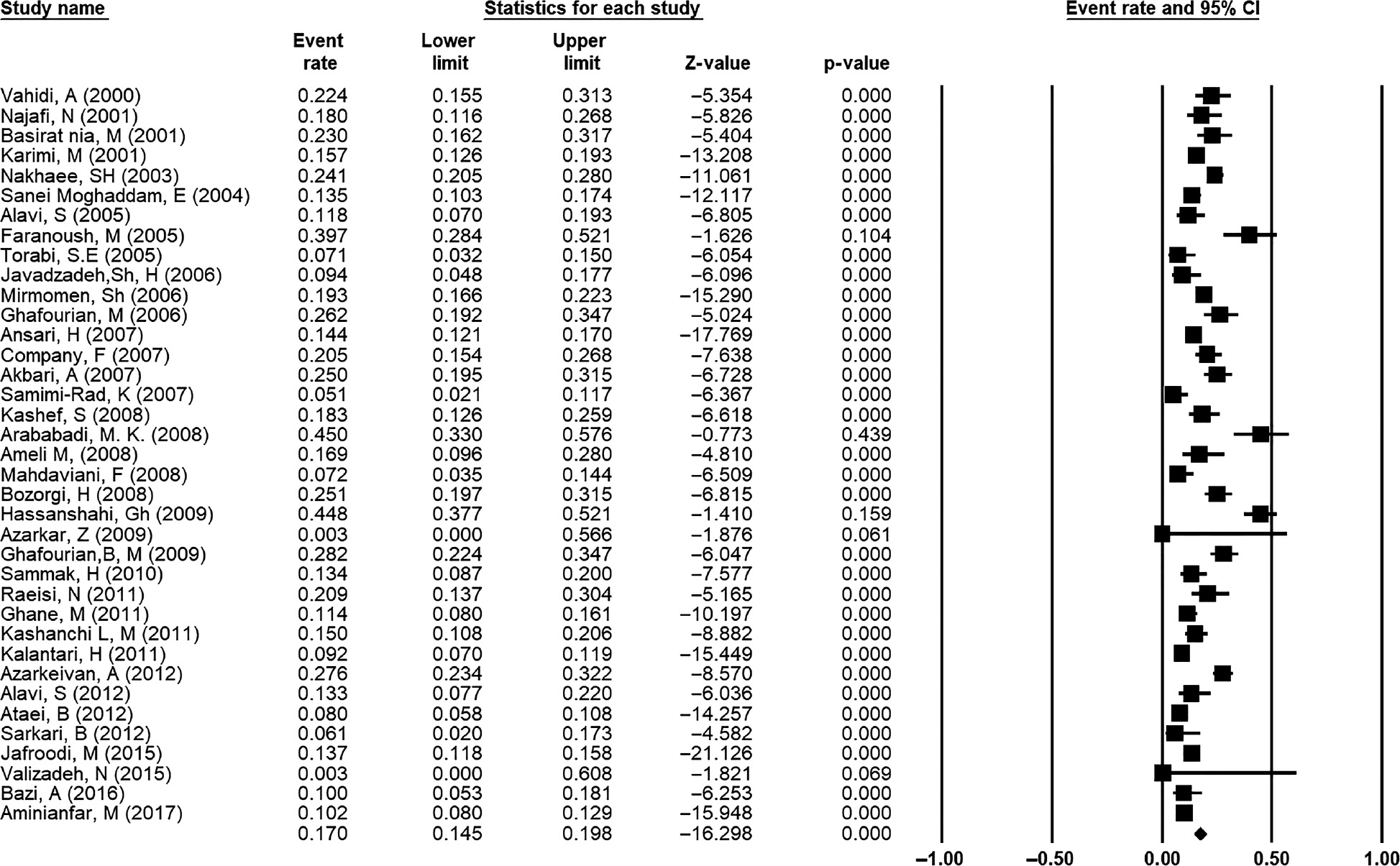

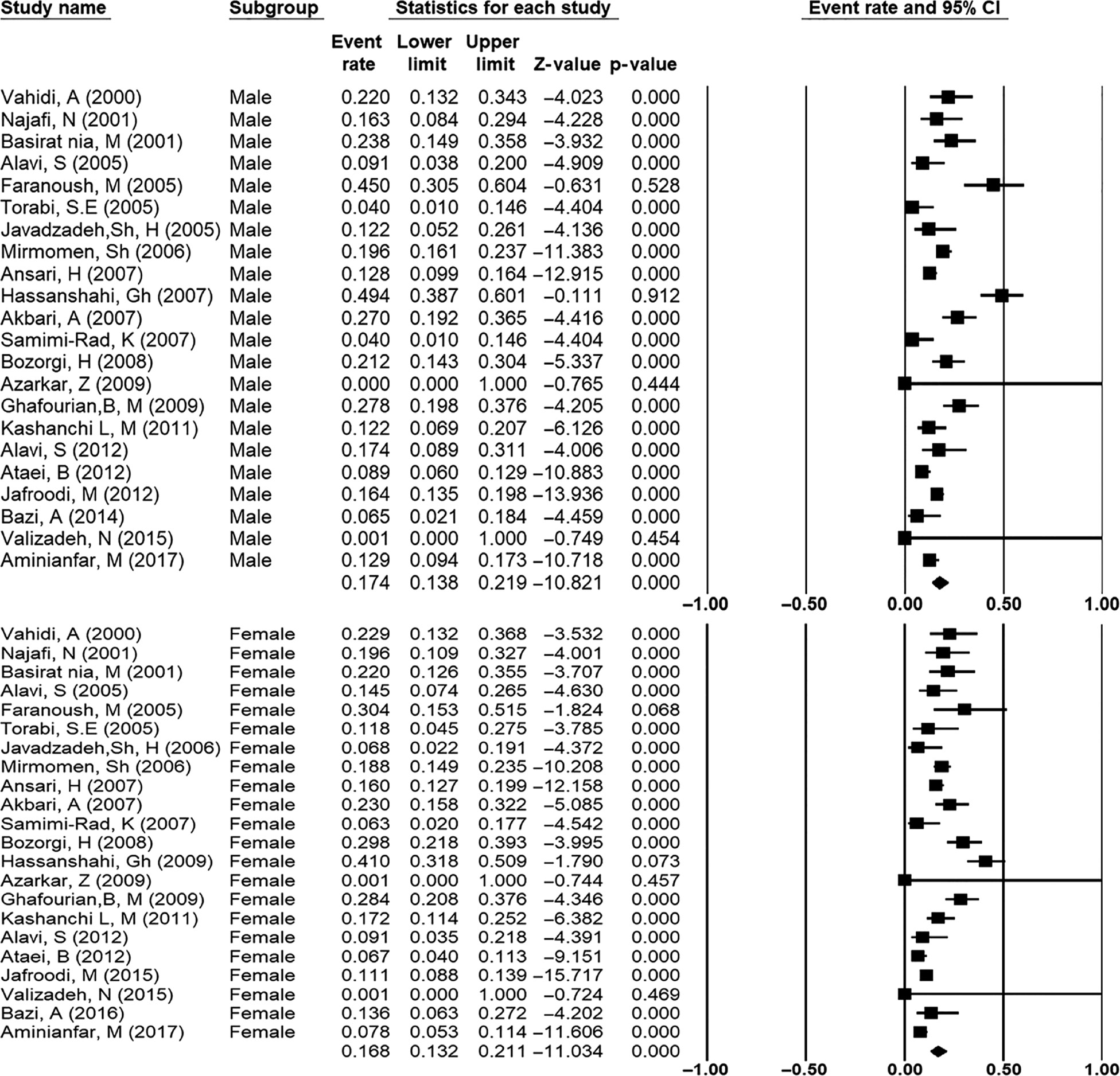

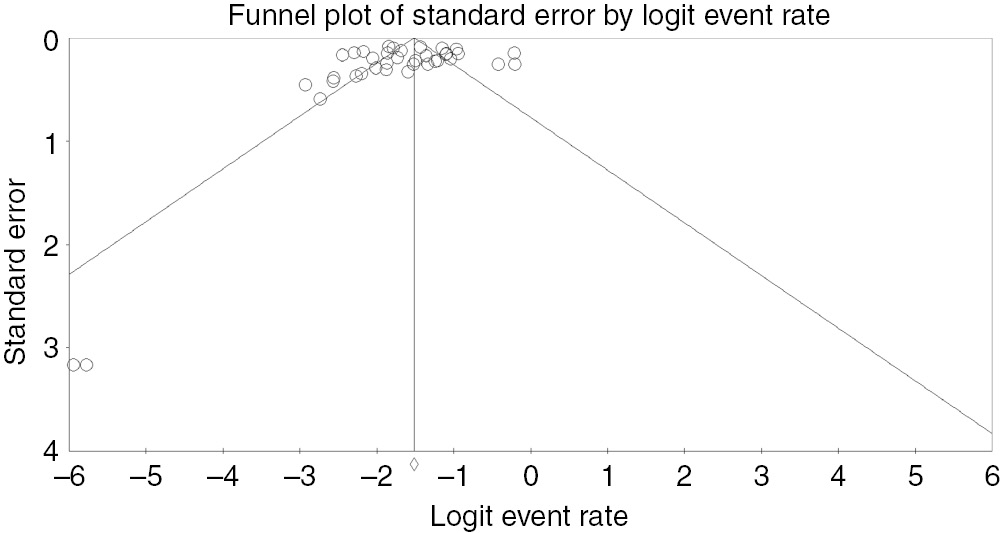

Based on these articles, the mean prevalence of hepatitis C infection in patients with thalassemia was 17.0% [95% confidence interval (CI): 14.5–19.8, I2=89.874%, p=0.000] (Figure 2). The prevalence of HCV in thalassemia male patients was 17.4% (95% CI: 13.8–21.9, I2=83.275%, p=0.000) and in females was 16.8% (95% CI: 13.2–21.1, I2=82.600%, p=0.000). Separate information on male and female patients is presented in Table 1 and Figure 3. In addition, Egger’s test results indicated no significant publication bias (p=0.185) (Figure 4).

Forest plot of meta-analysis on the prevalence of hepatitis C infection in patients with thalassemia in Iran with 95% CI.

Each horizontal bar shows the length of the CI. The diamond shape at the end of the figure shows the pooled prevalence based on random-effects models.

Forest plot of meta-analysis on the prevalence of hepatitis C infection among female and male patients with thalassemia in Iran with 95% CI.

Each horizontal bar shows the length of the confidence interval. The diamond at the end of the figure shows the pooled prevalence based on random-effects models.

Funnel plot for publication bias.

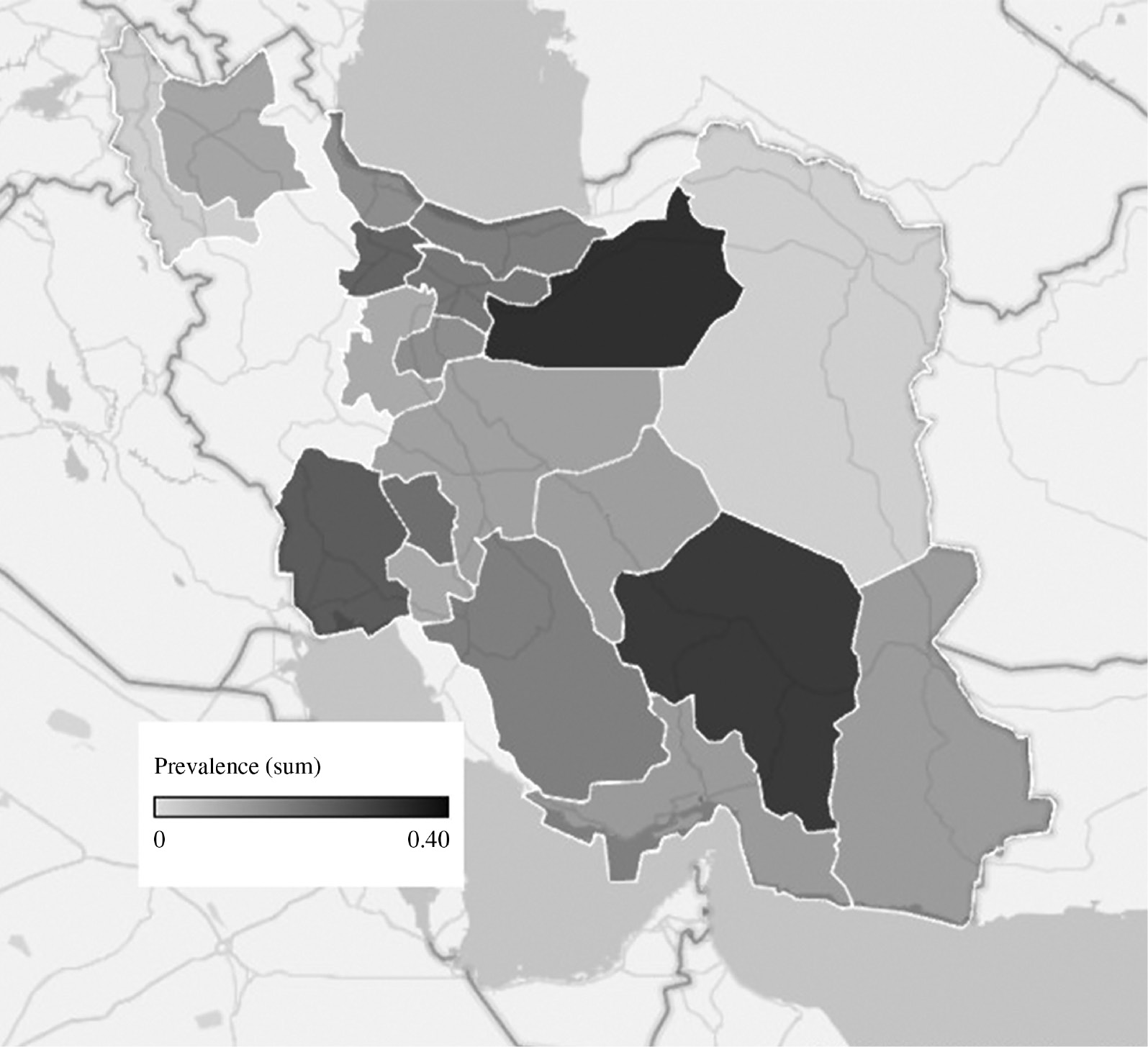

Distribution map

To illustrate the distribution of HCV prevalence in patients with thalassemia in different provinces of Iran, Excel 2016 software was used to design the map of Iran. A meta-analysis was conducted on the provincial prevalence that had been studied several times. Two multicenter studies in which the details of the prevalence were not reported by region were not included in the design of this map. No reports were found in the parts of the map that are colorless including Ardabil, Bushehr, Golestan, Hamadan, Kermanshah, Kurdistan, Lorestan, North-Khorasan, Razavi-Khorasan and Ilam. Details are presented in Figure 5.

Distribution of HCV prevalence among patients with thalassemia in different regions of Iran.

Discussion

The importance of HCV prevalence in patients with thalassemia and various reports of this prevalence in Iran followed by a mismatch between different studies made us perform this systematic review and meta-analysis to overcome the limitations of previous studies. This study was accomplished to estimate the prevalence and distribution of HCV among patients with thalassemia in Iranian population based on the available data extracted from all studies conducted in different parts of Iran for the first time.

The results of the meta-analysis on a combination of data from 37 studies showed the prevalence of HCV among patients with thalassemia in Iran is approximately 17.0% (95% CI: 14.5–19.8), which is nearly consistent with another review published by Alavian et al. in 2010 [56]. A comparison of the prevalence of HCV between these two studies shows that there has not been an increasing trend, implying that blood transfusion organization has had an reasonable performance regarding the management of HCV.

There are also contraindicating reports on the rate of prevalence in studies conducted in different parts of the world, for example, the prevalence of HCV among Egyptian, Taiwanese, Thai, Italian, Jordanian, Pakistan and eastern India thalassemia patients was reported 45.50%, 37.30%, 20.20%, 56.30%, 40.5%, 49% and 24.6%, respectively [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63]. Although our overall prevalence is lower than these reports, most of the studies we have reviewed is consistent with the mentioned studies from the other countries. To the best of our knowledge, there are no comprehensive studies on this topic worldwide. Moreover, the other remarkable thing is that most of these studies, regardless of the location of the research, have been conducted on a small sample size and are completely out of date. Hence, the gap of comprehensive local, national and global epidemiological studies is completely obvious.

The prevalence of HCV in male and female thalassemia patients was 17.4% (95% CI: 13.8–21.9) and 16.8% (95% CI: 13.2–21.1), respectively. This can be due to the weakness of the men’s immune system in comparison to the women in relation to HCV, which has not been confirmed specifically or properly. Although thalassemia is an autosomal inherited disease and has no relationship with gender some studies have pointed to the relationship between gender and the incidence of the disorder, which may occur due to thalassemia and HCV, suggesting that being male gender increases the risk of developing the disease. Moreover, there are also some unconfirmed reports about the relationship between age and the rate of infection [64], [65], [66].

Studies conducted in Iran indicate a significant difference on the prevalence rate of HCV among thalassemia patients. So that the highest prevalence of 45.10% (95% CI; 33.0–57.6) was observed in the study of Arababadi et al. [38] in the Kerman Province and the study of Samimi-Rad and Shahbaz [36] in the Markazi Province with 5.1% prevalence being the lowest frequency (95% CI; 2.1–11.7). According to the meta-analysis carried out separately on different provinces with multiple studies HCV prevalence in the Kerman Province was 36.70% and in the Markazi Province was 6.20%. It seems that Kerman is one of the most prevalent provinces for thalassemia in Iran.

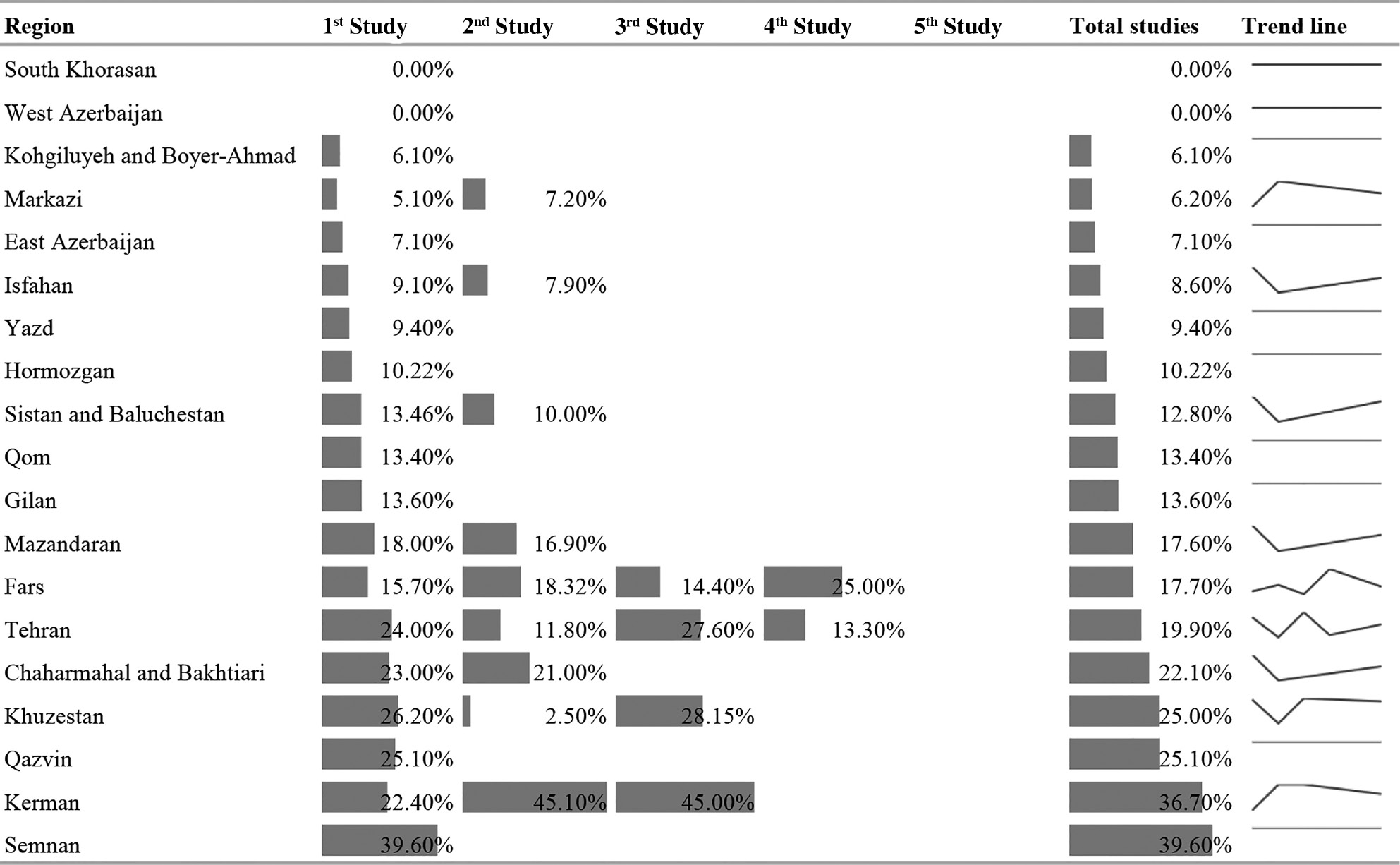

Figure 6 shows that most provinces face a lack of comprehensive studies regarding the subject. Studies in 20 provinces on the prevalence of HCV among thalassemia patients was as follow: half of them have only one study, in 25% of the provinces, only two studies have been conducted and only in 25% of them, more than two studies were available. The trend line indicates the reduction of the prevalence from the first study to subsequent studies in most of the provinces with multiple studies. However, there are no regular changes in this trend. Certainly, this can be due to various reasons, such as sample size, year and duration of the study, the area of study and even the age and clinical features of patients under investigation. Indeed, the difference in the prevalence of HCV and risk factors in the general population and blood donors may be the reason for the difference of heterogeneity in the geographical distribution of HCV in thalassemia patients [56].

Study trends in different provinces.

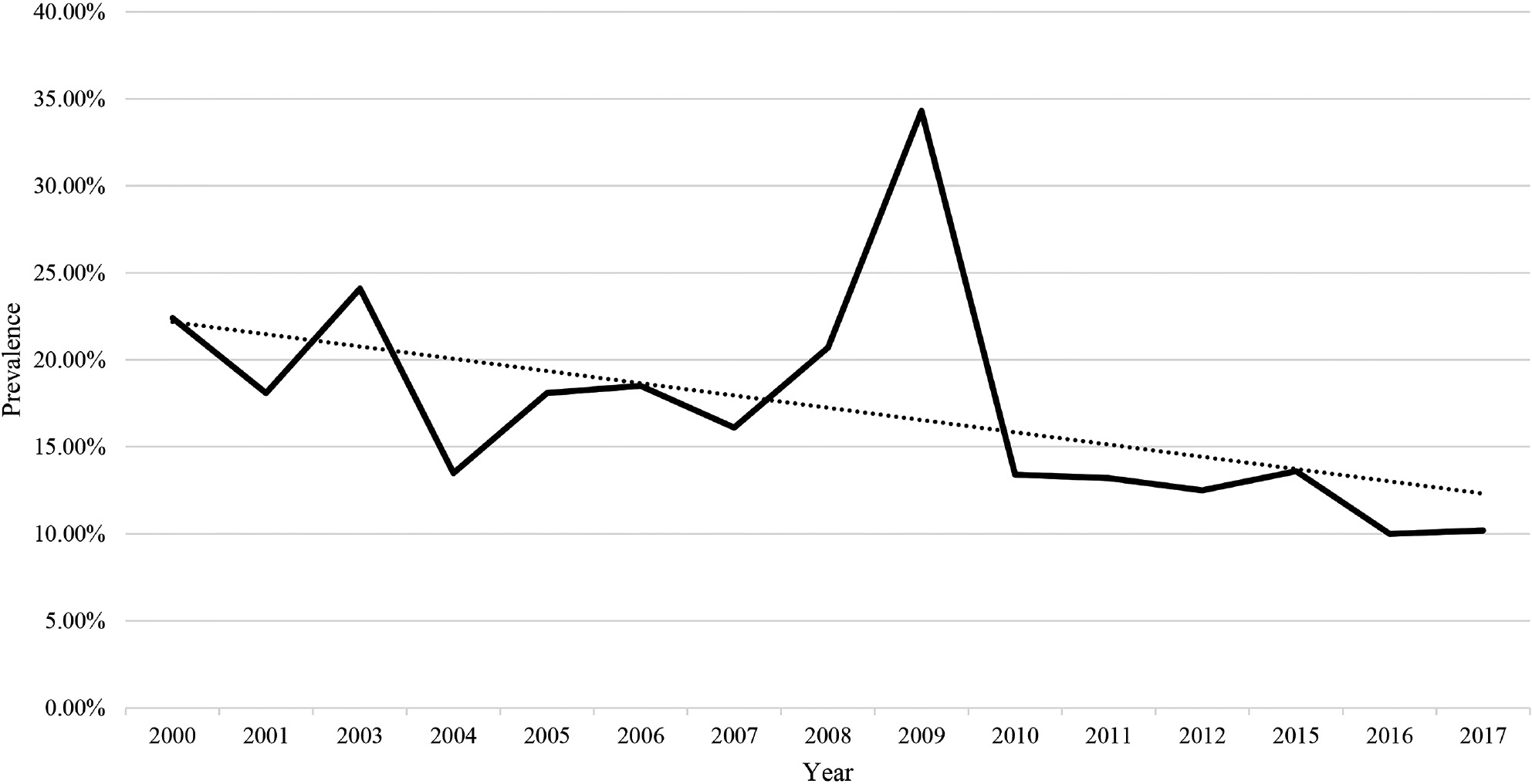

By referring to the Figure 7, it is clear that the trend of HCV prevalence among patients with thalassemia has decreased over time. This decline certainly demonstrates the good performance of diagnostic and therapeutic centers as well as timely screening programs of the blood transfusion organization of Iran that has prevented the disease from occurring.

Trend of HCV prevalence among patients with thalassemia over time.

As the purpose of this type of study is the regular and systematic review of available documents, the quantitative summarization, combination of the results of various studies, and providing a comprehensive interpretation of the results, therefore, present a general result from studies across Iran and is one of the remarkable points of present study, because there has been no recent comprehensive studies on this topic.

Limitations

This meta-analysis included several limitations, such as the failure to review abstracts of unpublished papers, papers presented at congresses, as well as the organizational reports, due to the inaccessibility and/or the lack of credibility. Besides, many epidemiological and scientific studies in Iran are conducted as dissertations and unfortunately, there is no comprehensive and coherent database at the national level for the systematic coverage and registration of these dissertations. In addition, it was not possible to evaluate the HCV trend in all the provinces of Iran. Moreover, this study cannot be completely generalized to the whole society of Iran, because in some parts (e.g. Ardabil, Bushehr, Golestan, etc.) there were no reports on the subject and in some provinces, only one study was conducted.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis has demonstrated the national prevalence of HCV among patients with thalassemia. Regarding the fact that, the prevalence rate declined over time, we can conclude that Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization has done a reasonably good job in screening blood donors for HCV infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their thanks to the student research committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study project with the code 23 approved on May 25, 2018.

Author contributions: AS: study design, search strategy, data collection, data analysis, wrote and revised the primary and ending drafts of the full text. RA-N: The data analysis, reviewing of the manuscript. AAP: helped in the preparation and revising of the manuscript. RA: contributed to the writing of the primary draft and reviewed the manuscript. ARM: contributed to the writing of the primary draft, reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Srivastava A, Shaji RV. Cure for thalassemia major–from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to gene therapy. Haematologica 2017;102:214–23.10.3324/haematol.2015.141200Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Dede A, Trovas G, Chronopoulos E, Triantafyllopoulos I, Dontas I, Papaioannou N, et al. Thalassemia-associated osteoporosis: a systematic review on treatment and brief overview of the disease. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:3409–25.10.1007/s00198-016-3719-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Alizadeh S, Bavarsad MS, Dorgalaleh A, Khatib ZK, Dargahi H, Nassiri N, et al. Frequency of betathalassemia or beta-hemoglobinopathy carriers simultaneously affected with alpha-thalassemia in Iran. Clin Lab 2014;60:941–9.10.7754/Clin.Lab.2013.130306Suche in Google Scholar

4. Saliba AN, El Rassi F, Taher AT. Clinical monitoring and management of complications related to chelation therapy in patients with beta-thalassemia. Expert Rev Hematol 2016;9:151–68.10.1586/17474086.2016.1126176Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Sayani FA, Kwiatkowski JL. Increasing prevalence of thalassemia in America: implications for primary care. Ann Med 2015;47:592–604.10.3109/07853890.2015.1091942Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Chawla S, Singh RK, Lakkakula BV, Vadlamudi RR. Attitudes and beliefs among high- and low-risk population groups towards beta-thalassemia prevention: a cross-sectional descriptive study from India. J Community Genet 2017;8:159–66.10.1007/s12687-017-0298-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Valizadeh N, Noroozi M, Hejazi S, Nateghi S, Hashemi A. seroprevalence of Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses among thalassemia patients in West North of Iran. Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol 2015;5:145–8.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Jafroodi M, Davoudi-Kiakalayeh A, Mohtasham-Amiri Z, Pourfathollah AA, Haghbin A. Trend in Prevalence of Hepatitis C virus infection among beta-thalassemia major patients: 10 years of experience in Iran. Int J Prev Med 2015;6:89.10.4103/2008-7802.164832Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Kim CW, Chang K-M. Hepatitis C virus: virology and life cycle. Clin Mol Hepatol 2013;19:17–25.10.3350/cmh.2013.19.1.17Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Lai ME, Origa R, Danjou F, Leoni GB, Vacquer S, Anni F, et al. Natural history of hepatitis C in thalassemia major: a long-term prospective study. Eur J Haematol 2013;90:501–7.10.1111/ejh.12086Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Sharma SD. Hepatitis C virus: molecular biology and current therapeutic options. Indian J Med Res 2010;131:17–34.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Alavian S-M, Adibi P, Zali M-R. Hepatitis C virus in Iran: epidemiology of an emerging infection. Arch Iranian Med 2005;8:84–90.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Ali I, Siddique L, Rehman LU, Khan NU, Iqbal A, Munir I, et al. Prevalence of HCV among the high risk groups in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Virol J 2011;8:296.10.1186/1743-422X-8-296Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Bastani MN, Bokharaei-Salim F, Keyvani H, Esghaei M, Monavari SH, Ebrahimi M, et al. Prevalence of occult hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian patients with beta thalassemia major. Arch Virol 2016;161:1899–906.10.1007/s00705-016-2862-3Suche in Google Scholar

15. López L, López P, Arago A, Rodríguez I, López J, Lima E, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis B and C in multi-transfused patients in Uruguay. J Clin Virol 2005;34:S69–74.10.1016/S1386-6532(05)80037-XSuche in Google Scholar

16. Vidja PJ, Vachhani J, Sheikh S, Santwani P. Blood transfusion transmitted infections in multiple blood transfused patients of beta thalassaemia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2011;27:65–9.10.1007/s12288-011-0057-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495–9.10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Pierce CA. Software Review: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein, HR. (2006). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Version 2.2.027) [Computer software]. Englewood, NJ: Biostat. Organizational Research Methods 2008;11:188–91.10.1177/1094428106296641Suche in Google Scholar

19. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J 2003;327:557.10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ades A, Lu G, Higgins J. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making 2005;25:646–54.10.1177/0272989X05282643Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Vahidi A, Taheri A, Nikan Y. Prevalence of hepatitis C in thalassemic patients referring to hospital No. 1 in Kerman University of Medical Sciences in 1996 [Persian]. 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Najafi N, Babamahmoudi F, Azizi S. A study on the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C in HCV-Ab positive patients referring to Gaemshahr Razi Hospital clinics in 1998. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci 2001;11:38–43.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Basirat nia M. Hepatitis C among families of thalassemic patients suffering from Hepatitis C in Shahrekord, 1999. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci 2001;3:33–6.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Karimi M, Ghavanini AA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies among multitransfused thalassaemic children in Shiraz, Iran. Paediatr Child Health 2001;37:564–6.10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00709.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Nakhaie S, Talachian E. Prevalence and characteristic of liver involvement in thalassemia patients with HCV in Ali-Asghar children hospital, Tehran, Iran (Farsi). J Iran Univ Med Sci 2003;37:799–806.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Sanei Moghaddam E, Savadkoohi S, Rakhshani F. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C in patients with major Beta-thalassaemia referred to Ali-Asghar hospital in Zahedan, 1381. Scient J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2004;1:19–26.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Alavi S, Arzanian M, Hatami K, Shirani A. Frequency of hepatitis C in thalassemic patients and its association with liver enzyme, Mofid Hospital, Iran, 2002. Pejouhesh dar Pezeshki (Research in Medicine) 2005;29:213–7.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Faranoush M, Ghorbani R, AminBidokhti ME, Parvaneh V, Malek M, Yazdiha MS. Prevalence of hepatitis C in patients with major thalassemia in Semnan, Damghan and Garmsar cities, 2002 [Persian]. 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Torabi SE, Abed Ashtiani K, Dehkhoda R, Moghadam AN, Sorkhabi R, Bahram MK, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C in thalassemic patients of East Azarbaijan in 2003. Scientific J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2005;2:115–22.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Javadzadeh Shahshahani H, Atar M, Yavari MT, Savabieh S. Study of the prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in hemophilia and thalassemia population of Yazd. Scientific J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2006;2:315–22.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Mirmomen S, Alavian SM, Hajarizadeh B, Kafaee J, Yektaparast B, Zahedi MJ, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infecions in patients with beta-thalassemia in Iran: a multicenter study. Arch Iran Med 2006;9:319–23.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Ghafourian Brujerdnia M, Osarehzadegahn Ma, Zandian K. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in thalassemic patients referring to Ahvaz Shafa Hospital (1999–2003) [Persian]. Jundishapur Scient Med J 2006;5:523–9.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Ansari H, Kamani H, Arbabi Sarjo A. Prevalence of hepatitis C and related factors among beta-thalassemia major patients in Southern Iran in 2005–2006. J Med Sci 2007;7:997–1002.10.3923/jms.2007.997.1002Suche in Google Scholar

34. Company F, Rezaei N. Study of prevalence of hepatitis C and its relationship with impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus in beta-thalassemic patients. J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci2008;12:45–52.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Ahmad A, MohammadHadi I, Mehran K, HamidReza T. Hepatitis C virus antibody positive cases in multitransfused thalassemic patients in South of Iran. Hepat Mon 2007;2007:63–6.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Samimi-Rad K, Shahbaz B. Hepatitis C virus genotypes among patients with thalassemia and inherited bleeding disorders in Markazi province, Iran. Haemophilia 2007;13:156–63.10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01415.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Kashef S, Karimi M, Amirghofran Z, Ayatollahi M, Pasalar M, Ghaedian MM, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and hepatitis C virus infection in Iranian thalassemia major patients. Int J Lab Hematol 2008;30:11–6.10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00916.xSuche in Google Scholar

38. Arababadi MK, Hassanshahi G, Yousefi H, Zarandi ER, Moradi M, Mahmoodi M. No detected hepatitis B virus-DNA in thalassemic patients infected by hepatitis C virus in Kerman province of Iran. Pak J Biol Sci 2008;11:1738–41.10.3923/pjbs.2008.1738.1741Suche in Google Scholar

39. Ameli M, Besharati S, Nemati K, Zamani F. Relationship between elevated liver enzyme with iron overload and viral hepatitis in thalassemia major patients in Northern Iran. Saudi Med J 2008;29:1611–5.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Mahdaviani F, Saremi S, Rafiee M. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in thalassemic and hemophilic patients of Markazi province in 2004. Scient J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2008;4:313–22.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Bozorgi H, Ramezani H, Vahid T, Mstajeri A, Kargarfard H, Rezaii M, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection among thalassemic patients of Qazvin (2005). J Qazvin Univ Med Sci 2008;11:54–9.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Hassanshahi G, Kazemi Arababadi M, Zarandi E, Moradi M, Vazirinegad R, Yousefi Darehdor H, et al. Prevalence of HCV infection in thalassemic and hemodialysis patients in Kerman Province – Iran. Iranian J Epidemiol 2009;5:41–6.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Azarkar Z, Sharifzadeh G, Chahkandi T, Mahmoudi Rad A, Sandoughi M, Rezaiee N. Survey of HBV and HCV markers in haemodialysis and thalassemia, South Khorasan, Birjand 2007. Scient J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2009;6:233–7.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Boroujerdnia MG, Zadegan MA, Zandian KM, Rodan MH. Prevalence of hepatitis-C virus (HCV) among thalassemia patients in Khuzestan Province, Southwest Iran. Pak J Med Sci Q 2009;25:113–7.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Sammak H, Azadegan Qomi H, Bitarafan M. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in patients with major ß thalassaemia in Qom, 2007. Qom Univ Med Sci J 2010;4:17–20.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Raeisi N, Raeisi P. Molecular evaluation of HCV infection by RT-PCR test in major beta thalassemia patients, Hajar Hospital of Shahrekord. Scient J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2011;8:74–8.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Ghane M, Eghbali M, Abdolahpour M. Prevalence of hepatitis C amongst beta-thalassemia patients in Gilan and Mazandaran Provinces, 2011. Govaresh 2011;16:22–7.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Kashanchi Langarodi M, Abdolrahim Poorheravi H. Prevalence of HCV among thalassemia patients in Shahid Bahonar Hospital, Karaj. Scient J Iran Blood Transfus Organ 2011;8:137–42.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Kalantari H, Mirzabaghi A, Akbari M, Kalantari M, Shahshahan Z. Hepatits C and B in blood transfusion recipients indentified at Isfahan province. J Isfahan Med Sch 2011;29:615–20.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Azarkeivan A, Toosi MN, Maghsudlu M, Kafiabad SA, Hajibeigi B, Hadizadeh M. The incidence of hepatitis C in patients with thalassemia after screening in blood transfusion centers: a fourteen-year study. Transfusion 2012;52:1814–8.10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03652.xSuche in Google Scholar

51. Alavi S, Valeshabad AK, Sharifi Z, Nourbakhsh K, Arzanian MT, Navidinia M, et al. Torque Teno virus and hepatitis C virus co-infection in Iranian pediatric thalassemia patients. Turk J Haematol 2012;29:156–61.10.5505/tjh.2012.20280Suche in Google Scholar

52. Ataei B, Hashemipour M, Kassaian N, Hassannejad R, Nokhodian Z, Adibi P. Prevalence of anti HCV infection in patients with beta-thalassemia in Isfahan – Iran. Int J Prev Med 2012;3(Suppl 1): S118–23.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Sarkari B, Eilami O, Khosravani A, Sharifi A, Tabatabaee M, Fararouei M. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection among high risk groups in Kohgiloyeh and Boyerahmad Province, Southwest Iran. Arch Iran Med 2012;15:271–4.10.1016/S1201-9712(11)60285-3Suche in Google Scholar

54. Bazi A, Mirimoghaddam E, Rostami D, Dabirzadeh M. Characteristics of Seropositive Hepatitis B and C Thalassemia Major Patients in South-East of Iran. Biotechnol Health Sci 2016;3:e35687.10.17795/bhs-35687Suche in Google Scholar

55. Aminianfar M, Khani F, Ghasemzadeh I. Evaluation of hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV virus serology pandemic in thalassemia patients of Shahid Mohammadi Hospital of Bandar Abbas, Iran. Electron Physician 2017;9:4014.10.19082/4014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Alavian S, Tabatabaei S, Lankarani K. Epidemiology of HCV infection among thalassemia patients in Eastern Mediterranean countries: a quantitative review of literature. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2010;2010:365–76.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Al-Sheyyab M, Batieha A, El-Khateeb M. The prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immune deficiency virus markers in multi-transfused patients. J Trop Pediatr 2001;47:239–42.10.1093/tropej/47.4.239Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Jang TY, Lin PC, Huang CI, Liao YM, Yeh ML, Zeng YS, et al. Seroprevalence and clinical characteristics of viral hepatitis in transfusion-dependent thalassemia and hemophilia patients. PloS One 2017;12:e0178883.10.1371/journal.pone.0178883Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Mansour AK, Aly RM, Abdelrazek SY, Elghannam DM, Abdelaziz SM, Shahine DA, et al. Prevalence of HBV and HCV infection among multi-transfused Egyptian thalassemic patients. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2012;5:54–9.10.5144/1658-3876.2012.54Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Rebulla P, Mozzi F, Contino G, Locatelli E, Sirchia G. Antibody to hepatitis C virus in 1,305 Italian multiply transfused thalassaemics: a comparison of first and second generation tests. Cooleycare Group. Transfus Med 1992;2:69–70.10.1111/j.1365-3148.1992.tb00138.xSuche in Google Scholar

61. Wanachiwanawin W, Luengrojanakul P, Sirangkapracha P, Leowattana W, Fucharoen S. Prevalence and clinical significance of hepatitis C virus infection in Thai patients with thalassemia. Int J Hematol 2003;78:374–8.10.1007/BF02983565Suche in Google Scholar

62. Din G, Malik S, Ali I, Ahmed S, Dasti JI. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among thalassemia patients: a perspective from a multi-ethnic population of Pakistan. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2014;7:S127–33.10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60218-2Suche in Google Scholar

63. Mukherjee K, Bhattacharjee D, Chakraborti G. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in repeatedly transfused thalassemics in a tertiary care hospital in eastern India. Internat J Res Med Sci 2017;5:4558–62.10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20174596Suche in Google Scholar

64. Al-Khabori MK, Al Busaifi S, Hassan M, Al Dhuhli H, Al Ajmi U, Al Rahbi S, et al. Male gender increases the risk of liver fibrosis in patients with thalassemia major independent of iron overload. Am Soc Hematol; 2016;128:3630.10.1182/blood.V128.22.3630.3630Suche in Google Scholar

65. Kyriakou A, Savva SC, Savvides I, Pangalou E, Ioannou YS, Christou S, et al. Gender differences in the prevalence and severity of bone disease in thalassaemia. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2008;6:116–22.Suche in Google Scholar

66. Niu Z, Zhang P, Tong Y. Age and gender distribution of hepatitis C virus prevalence and genotypes of individuals of physical examination in WuHan, Central China. SpringerPlus 2016;5:1557.10.1186/s40064-016-3224-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Infectiology and Microbiology

- Seroprevalence and geographical distribution of hepatitis C virus in Iranian patients with thalassemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Geriatric Laboratory

- White blood cell counts, CRP, GGT and LDH in the elderly German population

- Laboratory Management

- Pre-analytical quality control in hemostasis laboratories: visual evaluation of hemolysis index alone may cause unnecessary sample rejection

- Endocrinology

- Direct laboratory evidence that pregnancy-induced hypertension might be associated with increased catecholamines and decreased renalase concentrations in the umbilical cord and mother’s blood

- Allergy and Autoimmunity

- Investigating the presence of human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA) in the blood of laboratory animal care workers

- Original Articles

- Lipid indexes and parameters of lipid peroxidation during physiological pregnancy

- Biomarkers of oxidative stress in pregnant women with recurrent miscarriages

- Effects of sleeve gastrectomy on liver enzymes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related fibrosis and steatosis scores in morbidly obese patients: first year follow-up

- Laboratory Case Report

- Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostatic adenocarcinoma – an important cause for castration-resistant disease recurrence

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Infectiology and Microbiology

- Seroprevalence and geographical distribution of hepatitis C virus in Iranian patients with thalassemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Geriatric Laboratory

- White blood cell counts, CRP, GGT and LDH in the elderly German population

- Laboratory Management

- Pre-analytical quality control in hemostasis laboratories: visual evaluation of hemolysis index alone may cause unnecessary sample rejection

- Endocrinology

- Direct laboratory evidence that pregnancy-induced hypertension might be associated with increased catecholamines and decreased renalase concentrations in the umbilical cord and mother’s blood

- Allergy and Autoimmunity

- Investigating the presence of human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA) in the blood of laboratory animal care workers

- Original Articles

- Lipid indexes and parameters of lipid peroxidation during physiological pregnancy

- Biomarkers of oxidative stress in pregnant women with recurrent miscarriages

- Effects of sleeve gastrectomy on liver enzymes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related fibrosis and steatosis scores in morbidly obese patients: first year follow-up

- Laboratory Case Report

- Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostatic adenocarcinoma – an important cause for castration-resistant disease recurrence