Abstract

This article discusses the demarcation of contemporary ecolinguistics. It takes a starting point in different conceptualisations of the field, including (1) the claim that ecolinguistics is an umbrella term for work that attends to interconnections and dynamics in multiple contexts, (2) the claim that ecolinguistics comprises two traditions, a Haugenian tradition and a Hallidayan tradition, and (3) the claim that ecolinguistics consists of four strands that orient to the symbolic, sociocultural, natural, and cognitive ecology of language, respectively. Using bibliometric methods, the article concludes that there is currently no unity in ecolinguistics that warrants the first claim. Further, it concludes that there is no bibliometric or empirical evidence for the second claim, as there is virtually no connection between the two traditions, and hence they are two separate research areas, rather than two traditions within one field. Finally, it is shown that while there do indeed exist four ecological frameworks in linguistics, they are not subfields within ecolinguistics. It is concluded that contemporary ecolinguistics is defined by its preoccupation with natural ecologies. Based on this conclusion, it is suggested that the ecolinguistic preoccupation with natural ecologies presupposes treating language as integral to living and the ecology.

1 Introduction

Einar Haugen famously opened his 1972 chapter on The Ecology of Language with this critique of structural descriptions of languages:

Most language descriptions are prefaced by a brief and perfunctory statement concerning the number and location of its speakers and something of their history. Rarely does such a description really tell the reader what he ought to know about the social status and function of the language in question. Linguists have generally been too eager to get on with the phonology, grammar, and lexicon to pay more than superficial attention to what I would like to call the “ecology of language”. (Haugen 1972: 325)

Haugen points to two issues. One regards how linguists balance descriptions of structural properties of languages and their embeddedness in social and ecological processes. On this question, no ecolinguist has ever expressed disagreement with Haugen. The other issue pertains to the fallacy of “being too eager to get on with it”. This is a more sensitive question for ecolinguistics. On the one hand, we find ourselves in the most dire civilisational situation ever faced by humanity. We have realized that the industrialised mode of production, and its concomitant life forms, is not financed by past achievements of innovation and manufacture, but by withdrawing advance payments taken from the Earth’s resources, and hence also those resources that were supposed to feed our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. There are plenty of reasons to be eager to get on with it. On the other hand, a characteristic of the academia is to engage in self-reflexive evaluation and reevaluation of theoretical assumptions, methodological biases, and social and political implications of our work. Thus, a condition for academic work is to avoid the fallacy of “being too eager to get on with it” by, at times, taking a step back and consider the field to which one contributes, as well as one’s own work.

This article aspires to take such a reflexive, critical, and caring stance on the field of ecolinguistics anno 2024. By using bibliometric methods, it aspires to help ecolinguists reconsider many of the “brief and perfunctory statements” that are reproduced in ecolinguistics although they are no longer consistent with empirical facts about the field. These statements pertain to how the field is demarcated, that is, what is seen as constituting ecolinguistics, and by juxtaposing them to bibliometric evidence, it will be shown that they are no longer valid, even if they are still repeated in the field.

The article opens with a short Section 2 that provides a background for the current study. Section 3 gives a methodological overview of how the survey has been produced. Section 4 then turns to three models of ecolinguistics that have been used in the field since the mid-1990s: the ecolinguistics-as-one model, the ecolinguistics-as-two model, and the ecolinguistics-as-four model. Each of these models are discussed against the bibliometric evidence. Based on this empirical section, Section 5 discusses how the field oscillates between two competing definitions. One defines ecolinguistics in a broad sense that both comprises environmental and sociocultural issues (e.g. Fill and Penz 2018), whereas the other definition restricts ecolinguistics to the study of how language relates to environmental processes (e.g. Stibbe 2021). It is argued that the evidence unequivocally suggests that ecolinguistics anno 2024 is the study of the interconnections between language and the natural ecology. However, it is suggested that ecolinguistics is more than just the application of linguistic methods on data that relate to the environment and the ecological crisis. Finally, Section 6 concludes the article and bridges to another article that surveys ecolinguistics in accordance with the definition proposed here (Steffensen 2024).

2 Background

In the time of writing these words, it is ten years ago that Steffensen and Fill published their 2014 state of the art (Steffensen and Fill 2014), arguably still the most recent attempt at providing a full overview of the field, and still also the most cited journal article on ecolinguistics. A lot has happened in the past decade, including the establishment of the International Ecolinguistics Association (IEA; in 2017), the formation of the new Bloomsbury Advances in Ecolinguistics book series (edited by Arran Stibbe and Mariana Roccia), and the organisation of an annual/biennial conference series, the International Conferences of Ecolinguistics (ICE; organised by Huang Guowen and Sune Vork Steffensen). But most importantly, the scholarship that self-categorises as ecolinguistic has more than quadrupled in this period. Thus, according to a Scopus search performed on 4 April 2024 – searching in “all fields” for “ecolinguist*” (where the asterisk replaces 0 or more characters) – 281 publications associated with ecolinguistics were published in the period from 1987 to 2013, whereas the period from 2014 to 2023 gave rise to 1,175 publications.

A decade ago, the authors of a state of the art could reasonably claim to have a certain overview of a relatively limited field, but given these numbers, that would no longer be a credible claim. A survey of ecolinguistics can no longer rely on the method of authoritativeness, where the author simply “knows the field”. The field today is too large and too diverse for this type of survey. Accordingly, if one aspires to provide an updated state of the art, one needs to complement domain-specific expertise in ecolinguistics with additional survey methods.

This insight has guided recent work that seeks to survey ecolinguistics. For instance, Todd LeVasseur (2014) provides an emic overview of ecolinguistics which relies on a survey methodology where twenty-six members of the Language and Ecology Research Forum (the precursor to the International Ecolinguistics Association) responded to a questionnaire with such questions as “How would you define ecolinguistics?”, “What key topics are covered in ecolinguistics, and what key goals does ecolinguistics serve?”, etc. In a direct response to LeVasseur’s call for a more coherent definition of ecolinguistics, Chen (2016) makes use of a quantitative meta-analysis (or, content analysis) of those seventy-six peer-reviewed journal articles (from 1991 to 2015) that are deemed “most representative” of ecolinguistics. Chen’s focus is publication year and venue, topics addressed, and methods applied.

A third method is found in an extensive oeuvre, that sadly never had the impact on ecolinguistics that it deserved, as it is probably still the most ambitious attempt at providing a full overview of the field. This is the work of Nadège Lechevrel (2009, 2010 who turns to bibliometric methods in her comprehensive and critical evaluation of ecological approaches in the study of language. Faced with the challenge of nominalism (i.e. equating the concept and its name), Lechevrel relies on a broad strategy where she includes “cinq façons de désigner une approche écologique en linguistique” [“five ways to designate an ecological approach in linguistics”] (Lechevrel 2010: 47), namely linguistic ecology, ecological linguistics, the ecology of language/language ecology (Écologie du langage), the ecology of languages (Écologie des langues), and ecolinguistics (Lechevrel 2010: 48). Especially the second chapter of her 2010 monograph, but also her short English 2009 presentation at a symposium at the University of Southern Denmark (Lechevrel 2009), reports on her bibliometric results. With a starting point in the 139 documents on Web of Science that quotes Haugen’s 1972 book chapter, Lechevrel presents many important insights into the field, complemented by a comprehensive in-depth reading of the literature.

Finally, it is also worth mentioning Nur Asfar’s (2022) bibliometric study of major trends in ecolinguistics research. According to Asfar’s method description, she uses the search string “ecolinguistic*” OR “language and ecology” in Scopus’s “‘topic’ sections” which seems to cover “Article title, Abstract, Keywords” in Scopus. Unfortunately, Asfar does not justify her search terms, and using “language and ecology” rather than “language ecology” makes her miss 148 papers relevant for a bibliometric study of ecological approaches to language. Indeed, the five search terms established by Lechevrel would be a more useful basis for Asfar’s study. That said, Asfar’s study is still relevant to include here because it innovates by using VOSviewer (van Eck and Waltman 2010), a tool developed for viewing bibliometric relations in a single map. “VOS” is an abbreviation of “visualization of similarities” (van Eck and Waltman 2010: 524), and it combines two ways of mapping bibliometric relations: the use of distance between nodes and the use of graphs (lines) between nodes.

Summing up these methodological developments, this article aspires to integrate domain-specific expertise in ecolinguistics with a bibliometric analysis of the field. By adopting the latter approach, the present article aligns with the general ambitions of Chen, Lechevrel, and Asfar, but it attempts to provide a more solid bibliometric survey than these sources.

3 Methodology

This discussion of ecolinguistics is structured as a series of bibliometric visualisations created by using VOSviewer, complemented by close attention to the included publications in order to critically assess the field. The following three subsections of this section outlines the methodological considerations behind the use of bibliometric databases and VOSviewer.

3.1 Cautious nominalism

First of all, in the context of methods that rely on bibliographic databases, an overall cautious remark is warranted. Thus, using any search string to elicit an overview of a given field is blatantly nominalist, as it presupposes that the text string covaries with a real entity “out there”. Lechevrel was the first to rightly warn against a tendency to rely on historiographic nominalism in ecolinguistic historiographies, where inferences about properties of a given concept are drawn from the usage of a given word form. This is for instance the case for those ecolinguists who have spent much time on finding the earliest occurrences of the term ‘ecolinguistics’ (e.g. Couto 2014; Fill 2018) or the earliest collocation of language and ecology, even if these occurrences never made it into the discipline as we know it today. Thus, what does it matter that Claude Hagège (1985), Kurt Salzinger (1979), or Jean-Baptiste Marcellesi (1975) used the term “ecolinguistics” if it did not affect the current discipline? After all, many of these sources are only identified long after ecolinguistics became a field in its own right, so by definition their work did not contribute to ecolinguistics. It is hard to deny the veracity of Ludwig, Mühlhäusler, and Pagel’s (2019b: 9) observation that “these names are often introduced as a means of demonstrating the legitimate roots of ecolinguistics”. This is particularly the case since the term was developed in the tradition of French sociolinguistics, a line of thought that have had zero influence on contemporary ecolinguistics. Oddly, the only early (i.e. pre-1990) use of the term “ecolinguistics” as a reference to the study of language in human-nature relations has so far not been included in these overviews. This early instance is P.A. Stott’s (1978a) edited volume on Nature and Man in South East Asia. The second section of the volume is on “Ecology and language”, and in his own contribution to this section, Stott states that “this essay is first and foremost an attempt to encourage the development of what may be termed ‘ecolinguistics’ or ‘phytolinguistics’” (Stott 1978b: 172).

In what follows, I will circumvent this historiographic nominalism in two ways. First, I will adopt Lechevrel’s methodological attitude which says that nominalism cannot be wholesale rejected, as long as it is used with care: “methodological awareness is necessary when doing the history of the ecological paradigm in linguistics, i.e. regarding the benefits and drawbacks of a nominalist approach to identify trends and/or delimit a field of research” (Lechevrel 2009: 4). Lechevrel pursues this modus operandi by widening her search from ‘ecolinguistics’ in a narrow sense to ‘ecological approaches in linguistics’ more widely. She does so by operationalising ‘ecological approach’ in terms of the five search terms mentioned in the previous section, namely (in English): linguistic ecology, ecological linguistics, the ecology of language/language ecology, the ecology of languages, and ecolinguistics (cf. Lechevrel 2010: 48).

Second, I adopt Ian Hacking’s (2006) concept of “dynamic nominalism”. Dynamic nominalism implies that whenever a person adopts (or is attributed with) a concept that functions as a description of the person, they will accommodate to the concept by adjusting their behaviour. This mechanism is nominalist because it assumes the existence of a category that corresponds to the concept, and it is dynamic because the person changes its behaviour in accordance with the categorisation. Dynamic nominalism accounts for the fact that ecolinguists can adopt “ecolinguistics” as a self-classification of their work, and in doing so they orient to a wider field of other scholars who have also adopted the term “ecolinguistics”. Dynamic nominalism differs from historiographic nominalism, as the latter relies on a post hoc classification based on the superficial use of a term. When Salzinger (1979), for instance, used the term “ecolinguistics”, he did not dynamically adapt to any ecolinguistic scholarship, so inscribing him in a long ecolinguistic tradition is a nominalist fallacy.

3.2 Bibliometric databases

Visualisation methods rely on text files extracted from scientific databases. Accordingly, the quality of the visualisation depends on the source from which the text file is built. Academic databases vary in quality, coverage, and in output formats. Therefore, one can rarely rely on a single database that one-sizely fits all one’s needs, so deciding on a database is a matter of making trade-offs.

VOSviewer visualisations can be based on the direct import of data through an “application programming interface” that allows VOSviewer to extract relevant data directly from such applications as OpenAlex and Crossref, or it can be based on CSV files generated in bibliographic databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, Dimensions, Lens, or PubMed. The latter method has the advantage of securing that the included bibliographic data remain unaltered throughout the process of conducting and writing up the survey. Accordingly, the data underlying this survey is contained in CSV files extracted from the four databases listed in Table 1.[1]

Data sources and search strings underlying VOSviewer visualisations.

| Database | Search string | Date of search | Number of results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | Topic = ecolinguist* | 9 April 2024 | 220 items |

| Dimensions (extended) | Title/abstract = “ecolinguistics” OR “linguistic ecology” OR “ecological linguistics” OR “ecology of language” OR “language ecology” OR “ecology of languages” | 10 April 2024 | 1,525 items |

| Scopus (extended) | Title/abstract/keywords = “ecolinguistics” OR “linguistic ecology” OR “ecological linguistics” OR “ecology of language” OR “language ecology” OR “ecology of languages” | 11 April 2024 | 802 items |

| Scopus (narrow) | Title/abstract/keywords = ecolinguist* Language = English |

9 April 2024 | 292 items |

| Dimensions (narrow) | Title/abstract = ecolinguist* | 8 April 2024 | 734 items |

| Lens | Scholarly works = ecolinguist* | 10 April 2024 | 1,240 items |

-

Note: Across databases, the asterisk * is used as truncation.

Each of the four sources has different strengths and weaknesses. Web of Science has a conspicuously bad coverage of ecolinguistics. To exemplify, Arran Stibbe who is a key figure in the field only has three items in Web of Science, and the database excludes his three landmark monographs (Stibbe 2015, 2021, 2024).

Purely in terms of coverage, the two open access databases, Dimensions and Lens, perform significantly better than their profit-making competitors, Scopus and Web of Science. However, the data quality in the two open access databases are at times very low, for instance in terms of missing author information and the permutation of information across data fields. In general, Lens has more data points (and is as such “better”), but it requires a more narrow inclusion of data in the visualisation. In contrast, Dimensions has fewer data points, but for that very reason more data points can be included in the visualisation. Overall, the outcomes are quite similar, and Dimensions is used as the primary database for outlining the structures of the overall field of ecolinguistics. However, when it comes to a more fine-grained visualisation of the content of research in ecolinguistics, neither of the two open access databases do well. For this reason, Scopus is used to create fine-grained networks of keywords.

As mentioned in the introduction, there are two competing definitions of ecolinguistics. The broad definition is here equated with Lechevrel’s “ecological approaches in linguistics” (2010) which translates into the five search terms mentioned above. In Table 1, this appears as the extended Scopus and Dimensions databases. Conversely, the narrow definition is operationalised through the two narrow databases.

3.3 Visualisation parameters

This subsection will present VOSviewer as the bibliometric tool used in the article. VOSviewer is developed by Nees Jan van Eck and Ludo Waltman, affiliated with the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University. The tool allows for the visualisation of two kinds of maps: term co-occurrence maps (e.g. publication keywords) and maps of bibliographic data (e.g. authorships, affiliations, publication metadata, such as title, abstract, and outlet). In both cases, the maps contain three types of information:

information about the single items (represented by the size of the item)

information about the item’s similarity with other items (represented by distance to other items and by clustering using colours),

Information about the strength of inter-item connections (thickness of graphs/lines between items)

Consider Figure 1 as an illustration. This figure is based on the extended Scopus dataset (802 items), and it illustrates the largest co-authorship network in ecolinguistics, that is, those twelve authors that have co-authored ecolinguistic work with another author within the same network. The map depicts a number of relevant information that is coded in different ways:

Item size: in this map, item size indicates number of citations (the larger the circle, the more citations).

Graphs: in this map, graphs indicate co-authorship. Any two items connected with a graph has co-authored one or more publications; for instance, Mühlhäusler has co-authored with Nash, Ludwig, and Fill, but no other in the map.

Clusters: same colour indicates a cluster; for instance, Mühlhäusler, Nash, and Ludwig constitute one cluster. Exactly what constitutes this group cannot be read from the map.

Clusters and lines: Huang, Bao, Zhang, and Li are both clustered and interlinked, because they are thematically related (cluster) and have co-authored a number of articles (four, according to Scopus).

Distance: the Mühlhäusler cluster (green) and the Fill cluster (blue) are relatively more similar than the Fill cluster (blue) and the Huang cluster (red).

Inter-cluster connections: the three clusters are connected via inter-cluster connections between Mühlhäusler-Fill (who have published together) and Steffensen-Huang (who have published together). The two are linked because Steffensen and Fill are linked through their 2014 state of the art.

The largest co-authorship network in ecolinguistics. Minimum four publications.

For each map or visualisation being produced, one has to select a number of inclusion criteria. For instance, the map in Figure 1 includes authors that have authored four or more publications, whereas the alternative version in Figure 2 includes authors that have authored two or more publications.

Co-authorship network in ecolinguistics. Minimum two publications.

Obviously, the number of authors increase, as one lowers the criterion of numbers of publications. The figure is included because it illustrates some of the limitations of the visualisation. Thus, this figure includes Hermine Penz who branches out from Fill, as they have co-authored multiple pieces. However, Penz branches to yet another item called ‘Fill, Alwin F.’. This is obviously a database artefact, as Fill is both registered with and without his middle name (Frank). Unfortunately, VOSviewer allows for the removal of single items, but not the merging of two.

Adjusting the minimal cluster size is only one parameter that can be changed to affect the visualisation. To illustrate, Figure 3 is the same map as Figure 2, with the only difference that item size is not determined by number of citations, but by number of publications by an author. By comparing Figures 2 and 3, one can see that the visual appearance of the visualisations depends on which parameter the author selects. Any visualisation is as much a visualisation of author decisions as it is a visualisation of a given field.

Co-authorship network in ecolinguistics. Number of documents as weight.

VOSviewer allows for another layer of information which replaces clustering information. Thus, one can use ‘overlay visualization’ to depict the temporal development within a network. This visualisation setting allows to illustrate how a field develops in generations. Thus, if one considers Figure 4, one can see that Mühlhäusler and Fill belong to a first generation (purple colour), as their average publication years are 2011.30 and 2011.00, respectively. The second generation consists of Nash (2015.71), Ludwig (2015.50), Steffensen (2017.25), Pagel (2018.00), and Penz (2018.67). Cowley (2020.75) and Huang (2021.00) constitute a third generation, and within Chinese ecolinguistics, Huang has given rise to a new generation of scholars, including Zhou (2020.00), Bao (2021.25), Zhang (2022.33), and most recently Chen (2023.50). These authors may well have published several pieces in other fields, so the generational categorisation pertains to ecolinguistics only.

Co-authorship network in ecolinguistics. Overlaid with publication years.

Finally, to illustrate how different databases create very different results, Figure 5 is created using the exact same settings as Figure 2, with the only exception that the data file here is the extended Dimensions file rather than the extended Scopus file. Since Dimensions include many sources that are not indexed in Scopus, other author constellations come to the fore, and as one sees from the Figure, the largest co-authorship network in the Dimensions file is constituted by twenty-two Indonesian scholars. Ecolinguistics took off in Indonesia in 2017, and ninety-two out of the 1,525 items in the extended Dimensions file come out of Indonesia.

Co-authorship network in ecolinguistics. Extended Dimensions data file.

Some of the finer distinctions in VOSviewer, souch as the difference between the use of full counting and fractional counting (Perianes-Rodriguez et al. 2016), will be ignored here. Further information on this difference, as well as on VOSviewer in general can be found on the website of the tool (www.VOSviewer.com), as well as in the numerous publications of the creators of the tool (e.g. Lamers et al. 2021; van Eck and Waltman 2009; van Eck and Waltman 2010; van Eck and Waltman 2023; van Eck et al. 2010; Waltman and van Eck 2012; Waltman et al. 2010).

4 The demarcation of ecolinguistics

With these methodological considerations in place, we can now turn our attention to the key question pursued in this article: How is ecolinguistics demarcated? As mentioned in the introduction, this discussion targets the differences in the understanding of what ‘ecolinguistics’ means. In the literature, there are three different views on the demarcation of ecolinguistics: ecolinguistics as one, ecolinguistics as two, and ecolinguistics as four.

The ecolinguistics-as-one view insists that there is a single field of ecolinguistics, albeit this one field is the result of a unification of multiple complementary approaches. This unifying strategy was part of the ethos of the first monograph ever written on ecolinguistics, Alwin Fill’s Ökolinguistik: Eine Einführung [Ecolinguistics: An Introduction] (1993). Fill explicitly calls for a uniting (“Vereinigung”) of ecolinguistics (Fill 1993: 3): “Alle vorgestellten Ansätze einer ökologischen Sprachwissenschaft sollen zusammengeführt und zu einen neuen Zweig der Linguistik vereinigt werden” [“All presented approaches to ecological linguistics should be brought together and united into a new branch of linguistics”].This theme of unification also runs as an undercurrent in the second part of Steffensen and Fill’s 2014 state of the art, in which they “outline a unified framework of ecolinguistics” (Steffensen and Fill 2014: 8). Likewise, it appears in the introduction to a recent anthology on Language as an Ecological Phenomenon (Steffensen et al. 2024b). Symptomatically, the introduction features this discussion under the headline “Ecolinguistics: One or many?” (Steffensen et al. 2024a: 4–8).

The ecolinguistics-as-two view maintains that ecolinguistics consists of two traditions, one associated with Einar Haugen (1972), the other with Michael Halliday (1992). We also owe this distinction to the scholarship of Fill, as he was the first to argue that “dieser Verbindungen von Ökologie mit Sprache und Sprachwissenschaft scheint es aber grundsätzlich möglich, zwei ökolinguistische Richtungen zu unterscheiden” [“given these connections between ecology and language and linguistics, it seems fundamentally possible to distinguish between two ecolinguistic directions”] (Fill 1996: 3).

Finally, the ecolinguistics-as-four view appears in Steffensen and Fill’s 2014 state of the art (Steffensen and Fill 2014). Their literature review identifies four scholarly domains, depending on whether a given linguistic approach attends to the ecology from a symbolic, natural, sociocultural, or cognitive point of view. Recently, Steffensen et al. (2024a: 5) have argued that “the whole point of identifying the four discontinuous ecologies is to work for their elimination,” a point which was lost on many readers.

The purpose of the analyses in this section is to provide the bibliometric evidence that allows for a more nuanced understanding of these three views, and thus to provide a more empirically based demarcation of the field. To do so, the analysis attends to three crucial parameters:

the scientific keywords that describe the content of work in the field

the outlets (i.e. journals or sources) in which such work appears

the pattern of authors ordered along a gradient from more central (operationalised as more cited) to more peripheral

Figures 6–8 provide an overview along these three parameters.

Co-occurrence of keywords in the extended Scopus data file. The figure is based on all keywords that are used at least three times in the 802 publications. 166 keywords are included, and the figure shows the ‘item density’ of these 166 keywords. The more times a keyword co-occurs with other keywords, the ‘warmer’ it appears, and the more central it is placed within that group of keywords. Labels indicate keywords; size of labels indicate number of occurrences in the data set. Not all keywords appear in the map, as some are hidden under others. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as supplementary material.

An item density map of bibliographic coupling of sources (e.g. journals) in the extended Scopus data file. The figure shows the degree to which articles/chapters in given sources cite the same documents (van Eck and Waltman 2023: 27). The more citations two sources share, the closer they are to one another. Labels indicate sources; size of labels indicate number of citations to a given source. Not all source names appear in the map, as some are hidden under others. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as supplementary material.

An item density map of citation links between 785 authors in the extended Dimensions data file. The figure shows to which degree authors are interlinked via citations (from A to B or from B to A). The more publications an author has in the data, the ‘warmer’ they appear in the map. Labels indicate authors; size of labels indicate number of publications by the author. Not all author names appear in the map, as some are hidden under others. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as supplementary material.

4.1 The ecolinguistics-as-one view

Is the ecolinguistics-as-one view warranted? The three figures indicate a bipolar ordering of the field. Each of the three figures is organised around two red high-density areas with each their orange-yellow hinterland. Bear in mind that the three figures are based on the extended data files that included, in Lechevrel’s (2010) words, all “ecological approaches in linguistics”. Accordingly, a striking observation is that whether one attends to keywords, sources, or authors, the ecolinguistics-as-one view is unwarranted. There is not a single, coherent field of ecolinguistics that comprises ecolinguistics, linguistic ecology, ecological linguistics, ecology of language, language ecology, and ecology of languages (i.e., the ecological approaches as defined by Lechevrel’s search string).

The strong bipolarity in the maps suggest that ecolinguistics is not a single unified field. If one wants to pursue a unified definition of ecolinguistics, one is therefore forced to operate with a demarcation that excludes parts of what is mapped in Figures 6–8. Crucially, in the absence of empirical data that show an inherent unity, claims of unity are either observer-dependent projections (just as constellations in the night sky are projected by communities of earthly observers), or desiderata for a future development of the field.

The trend in contemporary ecolinguistics is to define ecolinguistics as the right pole in Figure 6. As a reviewer remarks in response to an earlier version of the article, this pole stands out as it attempts to overcome the anthropocentrism of mainstream linguistics by taking into consideration the natural ecology on which life depends. This contrasts with the left pole that explores sociolinguistic issues by taking an ecological perspective.

4.2 The ecolinguistics-as-two view

We can now turn to the question of what the two poles of the bipolar order in Figures 6–8 refer to. In doing so, one attends to the ecolinguistics-as-two view by raising the question whether the distinction between Haugenian and Hallidayan ecolinguistics is still a relevant model for contemporary ecolinguistics, or if indeed the development since it was first proposed by Fill (1996) suggests that it should be abandoned.

Let us first consider Figure 6 in detail. As mentioned, the model shows how the keywords within ecolinguistics in the extended sense (cf. Fill 1996; Fill and Penz 2018) are organised. We see that the two poles correspond to two networks of terms, one pivoting on ecolinguistics, and another on language ecology. The former is encircled by such terms as biodiversity, ecology, nature, sustainability, environment, environmental change, climate change – and also such linguistic terms as (critical) discourse analysis, and multimodal analysis. The latter, in contrast, links to terms like multilingualism, language policy, language planning, language maintenance, language shift, and linguistic diversity.

This picture is confirmed if one turns to journals/sources and authors, as shown in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. The split between the two poles is to a large degree coextensive with the organisation of sources. Thus, Figure 7 affiliates the ecolinguistic pole with such outlets as Language Sciences, The Ecolinguistics Reader, Journal of World Languages, The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics, Discourse and Communication, to name a few. Unsurprisingly, the other pole is associated with journals like Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, World Englishes, and Internal Journal of Bilingual Education.

Likewise, Figure 8 exhibits a similar bipolarity, where authors in the ecolinguistic pole includes Stibbe, Huang, Steffensen, Fill, Nash, and Umiyati, whereas the language ecology pole exhibits names like Mühlhäusler, Mufwene, Philipson, Hornberger, Blackledge, Kramsch, and Pennycook. A few authors do indeed cross the boundary between the two. Peter Mühlhäusler is arguably the most prominent one, and the collaboration between Kramsch and Steffensen also bridge the divide (Kramsch and Steffensen 2008; Steffensen and Kramsch 2017). However, it does not follow from that observation that the two poles are inherently linked, as authors can contribute to different fields.

In conclusion, the three bibliometric maps indicate that on all relevant parameters – keywords, sources, and authors – ecolinguistics in Fill’s original sense comes over as two distinct areas of research. Superficially, this may seem to confirm the ecolinguistics-as-two view, according to which ecolinguistics comprises a Haugenian tradition and a Hallidayan tradition. Yet, while the maps show that the field is indeed organised in two poles, the main insight from these maps is that the interconnections between the two poles are virtually non-existing. This is a crucial observation, because the lack of interconnections between the two poles undermines the claim that ecolinguistics is a field that consists of two complementary poles. Rather, the ecolinguistics-as-two model is the result of an observer-dependent claim about the parallels between two separate fields.

Judged from the bibliometric maps, there are no indications that the practitioners in the field engage with work from the other pole. In conclusion, the two-traditions view is thus only warranted by how collected works in the field are organised (Fill and Mühlhäusler 2001; Fill and Penz 2018), which is a quite shallow criterion. Accordingly, the conclusion of this bibliometric analysis is that there is no empirical evidence for the claim that ecolinguistics comprises a language ecology pole and a natural ecology pole.

4.3 The ecolinguistics-as-four view

We can now turn to the most recent model of the organisation of ecolinguistics, the ecolinguistics-as-four view presented by Steffensen and Fill (2014). To do so, we have to change perspective. The heatmap visualisations in the previous analyses provided a coarse-grained understanding of how the field is organised. These visualisations were relevant for discussing the adequacy of the ecolinguistics-as-one and ecolinguistics-as-two views. However, the heatmap visualisations are not adequate for providing a more detailed overview of work being carried out within the different poles. Thus, while it is tempting to conclude that the two poles correspond to a Haugenian and a Hallidayan pole, a more fine-grained view of the two poles will show that they are in fact composed by multiple smaller areas.

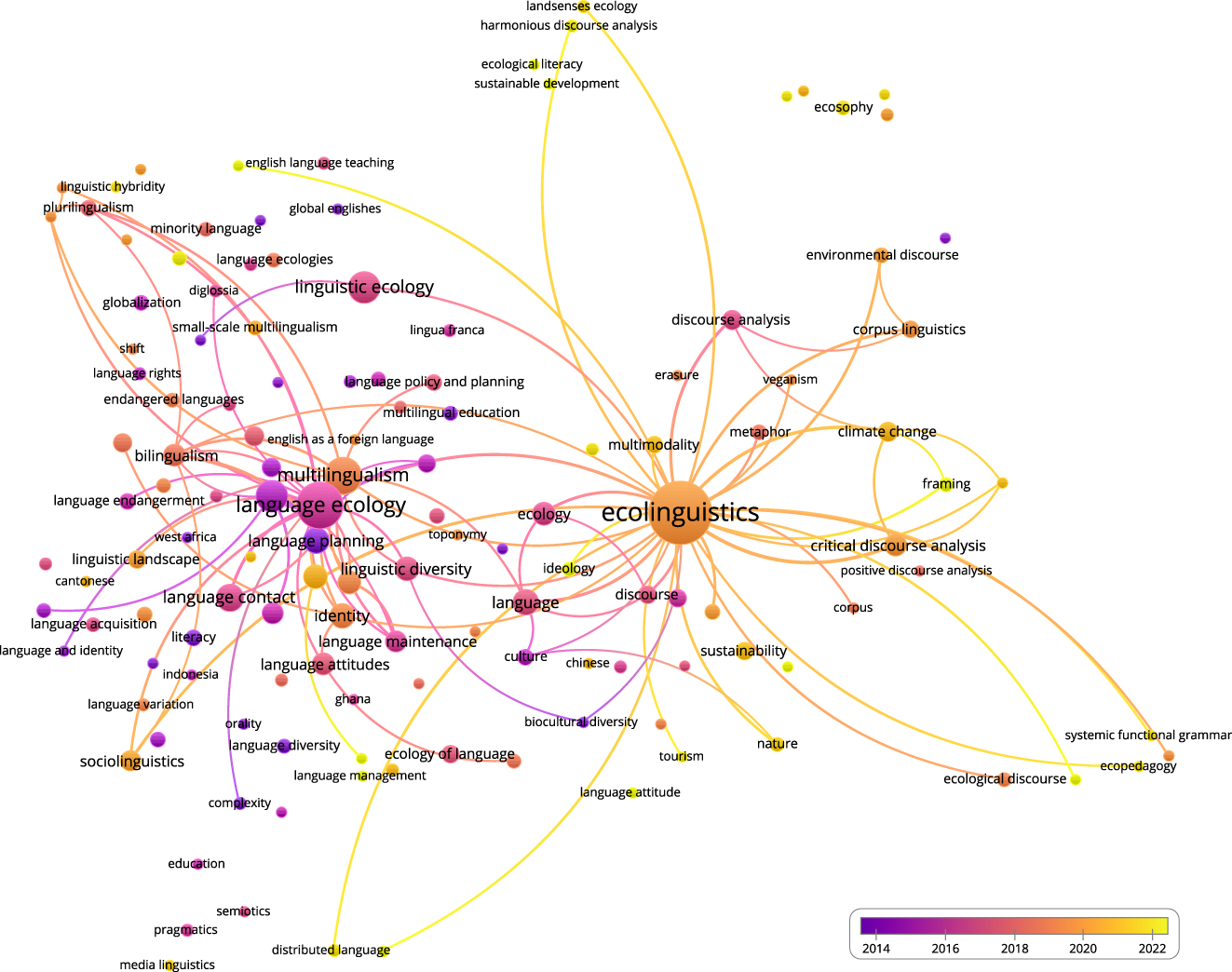

Accordingly, in order to get beyond the Haugen-Halliday duality, this section establishes how ecolinguistics is constituted by attending to the 135 author keywords that are use three or more times in the extended Scopus dataset. The co-occurrence of author keywords is exhibited in Figure 9, which shows the “cluster density” of author keywords, and Figure 10, which shows the co-occurrence, overlaid with information about publication year.

Co-occurrence of author keywords in the extended Scopus data file. Only keywords with three or more occurrences are included. Labels indicate keywords; size of labels indicate number of occurrences. Colours show the clustering of keywords, based on strength of co-occurrence. Not all keywords appear in the map, as some are hidden under others. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as supplementary material.

Co-occurrence of author keywords in the extended Scopus data file. Only keywords with three or more occurrences are included. Labels indicate keywords; size of labels and nodes indicate number of occurrences. Colours of the nodes indicate the average publication year for each keyword. Not all keywords appear in the map, as some are hidden under others. Files that allow for a zoomable map in VOSviewer are provided as supplementary material.

A first observation from Figures 9 and 10 is that the bipolar maps (Figures 6–8) do not give a full picture, as it gives the impression of a symmetry between the two poles. In contrast, Figures 9 and 10 are highly asymmetric. The language ecology pole (to the left) is both more varied and older than the ecolinguistics pole (to the right). The variability is shown in Figure 9 where more clusters inhabit the left half of the map than the right half. Likewise, Figure 10 shows that the average publication year is earlier at the left pole than at the right.[2] These observations support the conclusion that any description of ecolinguistics in terms of two subfields, two approaches, or two traditions is too superficial.

If we want a better understanding of the field, we need to pay closer attention to the configuration of the 135 author keywords, by considering the two measures in VOSviewer: the distance between nodes and the clustering of nodes.

Figure 11 depicts these keywords including their clustering (i.e. the colour of the nodes) and distance (i.e. the spatial distribution). In contrast to the ‘cluster density’ map in Figure 9, Figure 11 is technically a network map with inter-node links omitted, just as label names are omitted for clarity (the label names are identical to the names in Figures 9 and 10). This view allows for a manual bundling into four areas, based on three criteria:

Clusters can be only bundled if they occupy the same space, or when they occupy adjacent spaces

Clusters can be bundled if they exhibit thematic coherence

A single cluster is by default held together, unless it is discontinuous, that is, if a single cluster occupies two distinct spaces with one or more clusters occupying the space between these.[3]

Co-occurrence of author keywords in the extended Scopus data file. Size of nodes indicate number of occurrences. Colours show the clustering of keywords. Black lines indicate the superimposed bundling of keywords into four areas, depending on criteria of clustering and distance.

The four areas of bundled clusters cover a wide academic terrain. First, to the west on the map, one finds a bundle of brown, green, orange, yellow, and purple clusters. This is the sociolinguistic tradition of documenting the “language ecology” of languages that coexist in the same area. This is basically a continuation of Haugen’s project, and it has given rise to a rich tradition of studying language ecologies (or linguistic ecologies) characterised by language contact on multiple levels from individual speakers to speech communities. For a contemporary overview of this work, the reader is referred to the contributions in Ludwig, Mühlhäusler, and Pagel’s (2019a) excellent edited volume. Steffensen and Fill (2014: 8–9) referred to this line of work as the “symbolic ecology of language”.

The second area is in the middle of the figure, and it comprises the blue, indigo, light red, and light green clusters. It consists of scholars with an interest in language learning, socialisation, and acquisition. As Kramsch (2002a: 3) argues, they have sought to overcome the unhelpful juxtaposition between language acquisition and language socialisation by rallying around the ecology metaphor. By referring to social, cultural, institutional economical, and political forces as constituting an “ecology of language learning” (cf. Kramsch 2002b; Leather and Van Dam 2003), this tradition is the one which lies closest to the traditional preoccupations of applied linguistics (cf. Kramsch 2020; Steffensen and Kramsch 2017). In the 2014 state of the art, Steffensen and Fill referred to this body of work with the term “sociocultural ecology of language” (Steffensen and Fill 2014: 12–14).

The third area to the east (Red, light purple, light blue, and yellow clusters) is constituted by a large group of scholars who pursue Halliday’s question of how language relates to environmental and climatic processes, either by being shaped by these processes or by influencing them directly or indirectly. On the one hand, this tradition has taken up the baton from Sapir (1912: 229) who argued that languages depend on “fauna or topographical features,” depending on “the interest of the people in such environmental features.” Thus, through a filter of social relevance, languages are influenced by topographic and biological factors. On the other hand, under the influence of Halliday’s work, many scholars argue that the relationship is reciprocal, in the sense that meaning-making processes also shape our environmentally embedded behaviour. As such, language plays a role in the current ecological crisis (cf. Halliday 1992). This area correlates with Steffensen and Fill’s (2014: 9–12) “natural ecology of language”.

Finally, to the south one finds a single purple cluster of ecolinguists who focus on the cognitive aspects of the language-behaviour-environment nexus. Without explicitly evoking Salzinger’s (1979) behaviourism, they focus on how human agents engage with their sociomaterial environment, primarily by using methods from cognitive science, including ecological psychology (Steffensen and Baggs 2024), autopoietic biocognition (Kravchenko 2016), radical embodied cognitive science (Steffensen and Cowley 2021), and distributed cognition (Li et al. 2020). While this development is quite recent (cf. Steffensen et al. 2024b), it was foreshadowed by Lechevrel (2010: 69) who observed that “Étendues aux sciences cognitives, les approches écologiques concernent les domaines de la cognition située et distribuée, et on les retrouve dans le traitement des affordances, du pointage, et des interaction multimodale” [“Extended to cognitive sciences, ecological approaches concern the domains of situated and distributed cognition, and we find them in the treatment of affordances, pointing, and multimodal interactions”]. The first full attempt at establishing an ecological-cognitive version of ecolinguistics appeared in Steffensen (2008), and later in the second half of the Steffensen and Fill’s state of the art (2014: 16–22). Most readers of this work, however, have focused on the four strands model, and not on how the cognitive perspective in fact dissolves and unifies the four strands.

If one considers the boundaries between the language ecology (to the west) and the sociocultural ecology (in the middle), it meanders between three large keywords that are placed in great proximity to one another: ‘language ecology’ (blue), ‘multilingualism’ (green), and ‘language policy’ (brown). This proximity indicates that the boundary between these two areas is somewhat fluid. However, if one changes the lens from an author keyword map (as in Figure 11) to a citation map (Figure 12), the language ecology area and the sociocultural ecology area are indeed two distinct areas. A citation map structures publications within a given dataset according to the citation links between two publications (where the one cites the other or vice versa). Figure 12 maps the 245 publications which are part of the largest interconnected network of publications in the extended Scopus dataset.

The largest citation network in the extended Scopus dataset. Proximity indicates citation relations. Colours indicate VOSviewer’s clustering of publications, and size of labels indicate number of citations.

Crudely speaking, the map in Figure 12 has three sections:

In the middle, stretching toward the bottom left corner, there is a large area of many (albeit less cited) articles that would be categorised as the natural ecology of language and the cognitive ecology of language, or simply: ecolinguistics.

To the upper left, one finds a yellow area which corresponds to the symbolic ecology of language. It includes many publications on multilingualism and the linguistic ecology of select geographical areas.

To the right, the green area pertains to the sociocultural ecology, represented by work by such authors as Kramsch, van Lier, Creese, and Philipson.

Accordingly, this map documents that the symbolic ecology and the sociocultural ecology are in fact distinct. No single visualisation functions as the holy grail of bibliometrics, so it is no surprise that one has to draw on several figures to come up with an empirically based understanding of how a given field is organised.

In conclusion, the ecolinguistics-as-four view seems to find support in the bibliometric evidence. However, the premise of this conclusion is the broad Lechevrel-inspired search string, and the maps in this subsection suffer from the same limitations as the maps in the previous subsections, namely that the interconnections between the four areas are limited. While it is indeed warranted to claim that the overall category of “ecological approaches in linguistics” are organised in four different strands, it is not necessarily warranted to claim that all four areas contribute to a single, unified ecolinguistics. To do so is to merge this perspective with an ecolinguistics-as-one view, and as discussed in Section 4.1, this can either be an observer-dependent projection or a desideratum for the future. This conclusion leaves us with one important question that still needs to be considered: Faced with the bibliometric evidence, how do we demarcate ecolinguistics in a way that provides a sound basis for future work in the field? I will turn to this question in the next section.

5 The demarcation of ecolinguistics

The demarcation problem is found in all areas of academia, and hence also in ecolinguistics. The major tension in the field is whether ‘ecolinguistics’ should be used as an umbrella term for studies that take an ecological perspective on language teaching, language diversity, language contact, and language use in environmental contexts, or if the term should be restricted to the study of the entanglement of language and natural ecosystems?

When it comes to responding to this question, there are two dominant strategies in contemporary ecolinguistics. The first surfaces in Fill and Penz’s (2018) The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics, where Fill in the introduction states that “This handbook wishes to do justice to all the ideas that researchers have assembled under the umbrella term ‘ecolinguistics’” (Fill 2018: 3). This “Fillian Strategy” of interpreting ecolinguistics as an umbrella term is justified by appeal to these approaches being “complementary rather than mutually exclusive” (Fill 1998: 4), and by evoking such shared tenets as interdependence, process ontology, community, and the prioritisation of the small over the big (cf. Fill 1993: 1).

The second strategy is prominent in Arran Stibbe’s work. In contrast to Fill’s inclusive attitude, the “Stibbean Strategy” is to prioritise coherence and focus. Thus, in his monographs on ecolinguistics (Stibbe 2015, 2021), he links ecolinguistics to the broader movement of ecological humanities where “the object of study […] is viewed in the context of ecosystems and the physical environment” (Stibbe 2021: 8). By situating ecolinguistics in this tradition, Stibbe maintains that “ecolinguistics has increasingly converged with the broader ecological humanities, and primarily uses the term ‘ecology’ in its biological sense, i.e. the interaction of organisms with each other and their physical environment” (Stibbe 2021: 8). According to Stibbe’s strategy, work in the Haugenian tradition – which according to Fill (1998: 3) uses ‘ecology’ metaphorically – falls outside ecolinguistics because its focus is not on organismic interactions within an ecosystem, but rather on (vaguely defined) interactions between languages. Lechevrel (2010: 63) reports that Stibbe in a personal communication explicitly juxtaposes ecolinguistics and language ecology based on the Fillian criterion of whether ‘ecology’ is used metaphorically or literally.

The two criteria are mutually exclusive since Stibbe’s strategy will drive a wedge into the complementarity proposed by Fill. Interestingly, this dissociation has recently been mirrored by scholars who would be categorised under the Haugenian umbrella. Thus, Ludwig, Mühlhäusler, and Pagel write: “We prefer the term ecological linguistics over ecolinguistics. The latter term has been applied to a group of scientific studies particularly from the 1980s and 1990s, many (but not all) of which were motivated primarily by political, environmental, and social, but not always properly linguistic questions” (Ludwig et al. 2019b: 20). One would suspect that Ludwig, Mühlhäusler, and Pagel would place Stibbe in this category, and there is thus indications of a beginning schismogenesis (Bateson 2000) in ecolinguistics, as both camps now seek to define itself in mutually exclusive ways. If that is correct, the era of the umbrella is over. For three decades, it added to the ponderosity of the field, but the price turned out to be too high as it implied a fragmentation of ecolinguistics into parts that have little in common.

In the light of that conclusion, how should we then define ecolinguistics today? I suggest that the bibliometric evidence is unambiguous: Today, ecolinguistics is used to denote the study of how language impacts on the natural ecology in ways that change the conditions for life on Earth. The study of language contact, language learning, and similar phenomena constitutes an important research tradition, and it can be pursued by adopting an ecological perspective. However, it is not ecolinguistics, because the object of study is defined in terms of the anthropocentric categories of sociology and society.

Basically, this conclusion supports Stibbe’s strategy, but while I agree with Stibbe on what constitutes the object of study in ecolinguistics, I think there is an important caveat. Haugen never engaged with the more-than-human world, but he did something else that is equally important. He suggested that it is possible for the language sciences to develop and pursue an ecological perspective on language. As such, Haugen contributed to a reconsideration of the field’s language ontology (Demuro and Gurney 2021). This pioneering effort is crucial, and ecolinguists should be careful not to throw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. While Stibbe’s groundbreaking monograph builds on the assumption that “in this book, the ‘linguistics’ of ecolinguistics is simply the use of techniques of linguistic analysis to reveal the stories-we-live-by” (Stibbe 2015: 9), the first generation of ecolinguists in the early 1990s argued that the development of linguistic theories and methods was at the heart of the ecolinguistic endeavour. There is thus still a tension in the field between those who assume that ecolinguistics needs alternative linguistic ontologies, theories, and methods, and those who assume that it can merely apply extant methodologies to study language-ecology interactions. Interestingly, in the second edition of his monograph, Stibbe (2021: viii) makes “a shift to seeing language as part of ecosystems rather than just influencing how humans treat ecosystems”. As that position implies that new theories and methods for studying language is needed, ecolinguistics seems to converge on a shared appreciation of the need to pursue empirical work and theoretical development in tandem. Indeed, in a forthcoming handbook contribution, Stibbe argues that “ecolinguistics is a transdisciplinary movement rather than a discipline and its aim is to expand the discipline of linguistics to consider not just ‘language’ as mainstream linguistics does, not just ‘language in a social context’ as sociolinguistics does, but ‘language in its full social and ecological context’” (Stibbe forthcoming).

This theoretical concern guided the second half of Steffensen and Fill’s (2014) state of the art, and more recently, Steffensen, Döring, and Cowley’s (2024a) also argue in favour of basing ecolinguistics on an ecological perspective on language. This perspective, they argue, can be minimally defined by reference to what Haugen tried to achieve:

If ecolinguistics and ecolinguists are to work for life enhancing relations, this innovation must, as suggested in Haugen’s (1972) original vision, include seeing languages as part of a wider ecology. However, rather than to stick to a model of languages in ‘interaction’ with the ecology, in addressing what Cowley (2022) terms Haugen’s problem, we suggest treating languages as integral to living and the ecology. (Steffensen et al. 2024a: 5)

In this quote, the authors combine Haugen’s (minimal) ecological perspective and Stibbe’s strategy of understanding ecolinguistics as preoccupied with “the impact of language on the life-sustaining relationships among humans, other organisms and the physical environment” (Alexander and Stibbe 2014: 105). They thus effectively define ecolinguistics as a field that pursues an ecological concern (like Halliday did) by taking an ecological perspective on language (like in Haugen’s vision).

Today, it is clear that Haugen’s attempt was unsuccessful. However, the fact that he did not provide a sufficiently strong answer, does not invalidate the question: What is the theoretical and empirical value of adopting an ecological perspective on language? As discussed in Steffensen et al. (2024a), this question prompts us to consider language as an ecological phenomenon. Language is irreducible to a social construct, and it is not a reservoir of discourses and narratives. Rather, it is a way of living in and with ecologically salient environments. The importance of this point is that it contrasts with the portfolio of linguistic methodologies that was developed in a poststructural era of the second half of the 20th century. As such, it poses a challenge to those ecolinguists who have adopted methods and analytical strategies from this linguistic tradition.

6 Conclusions

This article has discussed some common and oft-repeated assumptions about ecolinguistics. By using bibliometric methods and VOSviewer, it has concluded that there is no empirical evidence for the claims that ecolinguistics is a unified research field and that it consists of a Haugenian and a Hallidayan tradition. The bibliometric evidence presented here has suggested that there is too little contact between these two research fields to warrant the claim that they constitute a single domain. Second, in line with the state of the art presented in Steffensen and Fill’s (2014), the article suggested that based on bibliometric criteria, there are four ecological approaches in linguistics today:

Language ecology attends to the symbolic ecology of languages

The sociocultural ecology of language attends to language planning and learning and other sociocultural processes in educational and societal contexts

Environmental ecolinguistics attends to the entanglement of language and the ecosystemic surroundings of speakers

Cognitive ecolinguistics attends to how language affects human agents in ways that have environmental implications, be they destructive or beneficial.

It was also concluded that one can no longer equate ecolinguistics with the broader domain of “ecological approaches in linguistics”. There is an ongoing schismogenesis in the field where ecolinguistics stand more and more apart as a field in its own right. After three decades of oscillating between questions of language contact etc., and questions pertaining to the ecological crisis, it seems that ecolinguistics is finally coming to terms with its object of study. On this view, only work that studies the natural ecology of language and the cognitive ecology of language, as defined in the list above, constitute ecolinguistics.

Finally, the article argued that ecolinguistics cannot be defined purely as work that uses linguistic techniques to investigate discursive and narrative constructs of the environment. Rather, it was suggested that ecolinguistics should continue the tradition from the first generation of ecolinguists that sought to develop an ecological perspective on language (as originally suggested by Haugen). Ecolinguistics can do so by turning to language ontologies that see “languages as integral to living and the ecology” (Steffensen et al. 2024a: 5).

Arguably, the most important result of this article is the conclusion that the definition of ecolinguistics in terms of a broad umbrella of Haugenian and Hallidayan approaches has had its time. Today, ecolinguistics is the study of how language plays a role in the interactions between human beings, non-human beings, and the physical environment. This conclusion raises a new question: What kind of work is pursued within this definition? This question is pursued in Steffensen (2024).

Funding source: Carlsbergfondet

Acknowledgments

I am immensely grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments that helped me focus the current article.

-

Research funding: This article is a by-product of a forthcoming monograph, the writing of which is supported by the Carlsberg Foundation (grant number CF22-1188).

References

Alexander, Richard J. & Arran Stibbe. 2014. From the analysis of ecological discourse to the ecological analysis of discourse. Language Sciences 41. 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2013.08.011.Search in Google Scholar

Asfar, Nur A. 2022. Major trends in ecolinguistic research: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Arts and Social Science 5(9). 43–50.Search in Google Scholar

Bateson, Gregory. 2000. Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago, Ill, London: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Sibo. 2016. Language and ecology: A content analysis of ecolinguistics as an emerging research field. Ampersand 3. 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2016.06.002.Search in Google Scholar

Couto, Hildo Honório do. 2014. Ecological approaches in linguistics: A historical overview. Language Sciences 41. 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2013.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

Cowley, Stephen J. 2022. Ecolinguistics reunited: Rewilding the territory. Journal of World Languages 7(3). 405–427. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2021-0025.Search in Google Scholar

Demuro, Eugenia & Laura Gurney. 2021. Languages/languaging as world-making: The ontological bases of language. Language Sciences 83. 101307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2020.101307.Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin. 1993. Ökolinguistik: Eine Einführung. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin. 1996. Ökologie der Linguistik – Linguistik der Ökologie. In Alwin Fill (ed.), Sprachökologie und Ökolinguistik: Referate des Symposions Sprachökologie und Ökolinguistik an der Universität Klagenfurt, 27–28. Oktober 1995, 3–16. Tübingen: Stuaffenburg Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin. 1998. Ecolinguistics – state of the art 1998. AAA: Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 23(1). 3–16.Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin. 2018. Introduction. In Alwin Fill & Hermine Penz (eds.), The Routledge handbook of ecolinguistics, 1–7. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315687391-1Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin & Peter Mühlhäusler (eds.). 2001. The ecolinguistics reader: Language, ecology, and environment. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Fill, Alwin & Hermine Penz (eds.). 2018. The Routledge handbook of ecolinguistics. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315687391Search in Google Scholar

Hacking, Ian. 2006. Making up people. London Review of Books 28(16). 23–26.Search in Google Scholar

Hagège, Claude. 1985. L’homme de Paroles contribution linguistique aux sciences humaines. Paris: Fayard.Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1992. New ways of meaning: The challenge to applied linguistics. In Martin Pütz (ed.), Thirty years of linguistic evolution, 59–95. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.61.09halSearch in Google Scholar

Haugen, Einar. 1972. In Anwar S. Dil (ed.), The ecology of language. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire. 2002a. Introduction: “How can we tell the dancer from the dance?”. In Claire Kramsch (ed.), Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives, 1–30. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire (ed.). 2002b. Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire. 2020. Educating the global citizen or the global consumer? Language Teaching 53(4). 462–476. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444819000363.Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire & Sune Vork Steffensen. 2008. Ecological perspectives on second language acquisition and socialization. In Nancy H. Hornberger (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education, 2nd edn., 17–28. New York: Springer.Search in Google Scholar

Kravchenko, Alexander V. 2016. Two views on language ecology and ecolinguistics. Language Sciences 54. 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2015.12.002.Search in Google Scholar

Lamers, Wout S., Kevin Boyack, Vincent Larivière, Cassidy R. Sugimoto, Nees Jan van Eck, Waltman Ludo & Dakota Murray. 2021. Meta-research: Investigating disagreement in the scientific literature. eLife 10. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.72737.Search in Google Scholar

Leather, Jonathan & Jet Van Dam (eds.). 2003. Ecology of language acquisition. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.10.1007/978-94-017-0341-3Search in Google Scholar

Lechevrel, Nadège. 2009. The intertwined histories of ecolinguistics and ecological approaches of language(s): Historical and theoretical aspects of a research paradigm. Paper presented at the Symposium on Ecolinguistics: The Ecology of Science, University of Southern Denmark (Odense, Denmark), June 11.Search in Google Scholar

Lechevrel, Nadège. 2010. Les approches écologiques en linguistique: enquête critique. Louvain-La-Neuve: Academia Bruylant.Search in Google Scholar

LeVasseur, Todd. 2014. Defining “ecolinguistics?”: Challenging emic issues in an evolving environmental discipline. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5(1). 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-014-0198-4.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Jia, Sune Vork Steffensen & Guowen Huang. 2020. Rethinking ecolinguistics from a distributed language perspective. Language Sciences 80. 101277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2020.101277.Search in Google Scholar

Ludwig, Ralph, Peter Mühlhäusler & Steve Pagel (eds.). 2019a. Linguistic ecology and language contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781139649568Search in Google Scholar

Ludwig, Ralph, Peter Mühlhäusler & Steve Pagel. 2019b. Linguistic ecology and language contact: Conceptual evolution, interrelatedness, and parameters. In Ralph Ludwig, Peter Mühlhäusler & Steve Pagel (eds.), Linguistic ecology and language contact, 3–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781139649568.002Search in Google Scholar

Marcellesi, Jean-Baptiste. 1975. Basque, breton, catalan, corse, flamand, germanique d’alsace, occitan: l’enseignement des «langues régionales». Langue Française 25. 3–11. https://doi.org/10.3406/lfr.1975.6052.Search in Google Scholar

Perianes-Rodriguez, Antonio, Ludo Waltman & Nees Jan van Eck. 2016. Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics 10(4). 1178–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2016.10.006.Search in Google Scholar

Salzinger, Kurt. 1979. Ecolinguistics: A radical behavior theory approach to language behavior. In Doris Aaronson & Robert W. Rieber (eds.), Psycholinguistic research: Implications and applications, 109–130. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Sapir, Edward. 1912. Language and environment. American Anthropologist 14(2). 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1912.14.2.02a00020.Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork. 2008. The ecology of grammar. Dialectical, holistic and autopoietic principles in ecolinguistics. In Martin Döring, Hermine Penz & Wilhelm Trampe (eds.), Language, signs and nature: Ecolinguistic dimensions of environmental discourse: Essays in honour of Alwin Fill, 89–106. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork. 2024. Surveying ecolinguistics. Journal of World Languages. https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2024-0044.Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork & Edward Baggs. 2024. Ecolinguistics and the cognitive ecology of global warming. In Sune Vork Steffensen, Martin Döring & Stephen Cowley (eds.), Language as an ecological phenomenon: Languaging and bioecologies in human-environment relationships, 55–81. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350304512.ch-003Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork & Stephen J. Cowley. 2021. Thinking on behalf of the world: Radical embodied ecolinguistics. In Xu Wen & John R. Taylor (eds.), The Routledge handbook of cognitive linguistics, 723–736. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351034708-47Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork, Martin Döring & Stephen J. Cowley. 2024a. Ecolinguistics: Living and languaging united. In Sune Vork Steffensen, Martin Döring & Stephen J. Cowley (eds.), Language as an ecological phenomenon: Languaging and bioecologies in human-environment relationships, 1–26. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350304512.ch-001Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork, Martin Döring & Stephen J. Cowley (eds.). 2024b. Language as an ecological phenomenon: Languaging and bioecologies in human-environment relationships. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350304512Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork & Alwin Fill. 2014. Ecolinguistics: The state of the art and future horizons. Language Sciences 41. 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2013.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

Steffensen, Sune Vork & Claire Kramsch. 2017. The ecology of second language acquisition and socialization. In Patricia A. Duff & Stephen May (eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Language socialization, 1–16. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-02327-4_2-1Search in Google Scholar

Stibbe, Arran. 2015. Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology and the stories we live by. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Stibbe, Arran. 2021. Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology and the stories we live by, 2nd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780367855512Search in Google Scholar

Stibbe, Arran. 2024. Econarrative: Ethics, ecology, and the search for new narratives to live by. London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781350263154Search in Google Scholar

Stibbe, Arran. forthcoming. Ecolinguistics and the rethinking of society: From grammar to narrative. In Rebekah Wegener, Lise Fontaine, Akila Sellami-Baklouti & Anne McCabe (eds.), The Routledge handbook of transdisciplinary systemic functional linguistics. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Stott, Philip A. (ed.). 1978a. Nature and man in South East Asia. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.Search in Google Scholar

Stott, Philip A. 1978b. The red forest of Thailand: A study in vernacular forest nomenclature. In Philip A. Stott (ed.), Nature and man in South East Asia, 165–176. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.Search in Google Scholar

van Eck, Nees J. & Ludo Waltman. 2009. VOSviewer: A computer program for bibliometric mapping. In 12th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, ISSI 2009. Available at: https://www.issi-society.org/proceedings/issi_2009/ISSI2009-proc-vol2_Aug2009_batch2-paper-15.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

van Eck, Nees J. & Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84(2). 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.Search in Google Scholar

van Eck, Nees J. & Ludo Waltman. 2023. VOSviewer manual: Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6.20. Leiden: Leiden University.Search in Google Scholar

van Eck, Nees J., Ludo Waltman, Rommert Dekker & Jan van den Berg. 2010. A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61(12). 2405–2416. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21421.Search in Google Scholar

Waltman, Ludo & Nees Jan van Eck. 2012. A new methodology for constructing a publication-level classification system of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 63(12). 2378–2392. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22748.Search in Google Scholar

Waltman, Ludo, Nees Jan van Eck & Ed C. M. Noyons. 2010. A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. Journal of Informetrics 4(4). 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2024-0043).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- On the demarcation of ecolinguistics

- A comparative corpus-based ecological discourse analysis of Chinese, Indian, and American news reports on the Belt and Road Initiative (2013–2022)

- Lexical niche and sustainability: an ecolinguistic perspective

- A typology of the Arabic system of mood

- Readability and adaptation of children’s literature: an interpersonal metaphor perspective

- A review of interpersonal metafunction studies in systemic functional linguistics (2012–2022)

- Transmigrant identities and attitudes: the case of a Pangasinan-American family

- Book Reviews

- Bingjun Yang: Non-finiteness: A process-relation perspective

- Anastazija Kirkova-Naskova, Alice Henderson & Jonás Fouz-González: English pronunciation instruction: Research-based insights

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- On the demarcation of ecolinguistics

- A comparative corpus-based ecological discourse analysis of Chinese, Indian, and American news reports on the Belt and Road Initiative (2013–2022)

- Lexical niche and sustainability: an ecolinguistic perspective

- A typology of the Arabic system of mood

- Readability and adaptation of children’s literature: an interpersonal metaphor perspective

- A review of interpersonal metafunction studies in systemic functional linguistics (2012–2022)

- Transmigrant identities and attitudes: the case of a Pangasinan-American family

- Book Reviews

- Bingjun Yang: Non-finiteness: A process-relation perspective

- Anastazija Kirkova-Naskova, Alice Henderson & Jonás Fouz-González: English pronunciation instruction: Research-based insights