Abstract

While approaches informed by Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) have been widely applied to the field of language education since the 1960s, the idea of the system embodying the meaning potential of language in context, represented as a system network, could be used to make a much more significant contribution to second language (L2) or foreign language education, where despite pioneering efforts the uptake of SFL has been less than in L1 education. In this paper, we will take stock of the ways system networks have been used in studies concerned with L2 education and at the same time we will highlight new opportunities to empower new studies and applications based on system networks as a way of engaging with the central notion of learning how to mean in a second/foreign language. We argue that system networks can make a very significant contribution to L2 education if they are given more attention and their deployment is highlighted. The uses considered in this paper include the following: Tracking language development systemically; diagnosing problems in L2 student texts; supporting sequencing in the curriculum of the learning of the L2 meaning potential; designing exercises based on options in system networks; guiding L2 learners by means of system networks as cartographic tools; contrasting L1 and L2 resources based on multilingual system networks; and supporting advanced L2 learners expanding their L2 uses by adding translation skills drawing on multilingual system networks. We will touch on these uses, highlighting those that have perhaps given the least attention in L2 education drawing on SFL, but which look very promising as we move ahead in the next couple of decades.

1 Introduction: the role of system networks in the study of language learning

In this paper, we are concerned with the power of system networks in L2 education – actual and potential uses within a spectrum of activities within this special field within language education. We will suggest and show that system networks can empower not only teachers but also students, and the processes that enable them to work towards the mastery by L2 students of more and more of their L2 – processes like curriculum design and materials development. For those not familiar with SFL, Sections 1 and 2 will serve as a general introduction to system networks. More ad hoc clarifications of specific system networks can be found in Section 3.

System networks were developed originally by M.A.K. Halliday, the originator of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), in the 1960s in order to represent language as a resource (rather than as a rule system; see e.g. Halliday 2003 [1977]) – more specifically, a resource for making meaning. This he theorized by interpreting language as a meaning potential (e.g. Halliday 1973): what users of a language can mean , the system behind their actual acts of meaning unfolding as texts in context. Halliday’s theory of language as meaning potential can be compared to Hymes’ (1966) notion of communicative competence; but while Hymes introduced his notion as a remedial expansion of Chomsky’s (1965) notion of competence, Halliday’s “meaning potential” has quite a different foundation from Chomsky’s competence, and, importantly, in the context of our discussion, it is based on the interpretation of the paradigmatic axis of language as the primary mode of linguistic order – precisely because it foregrounds the nature of language as a resource.

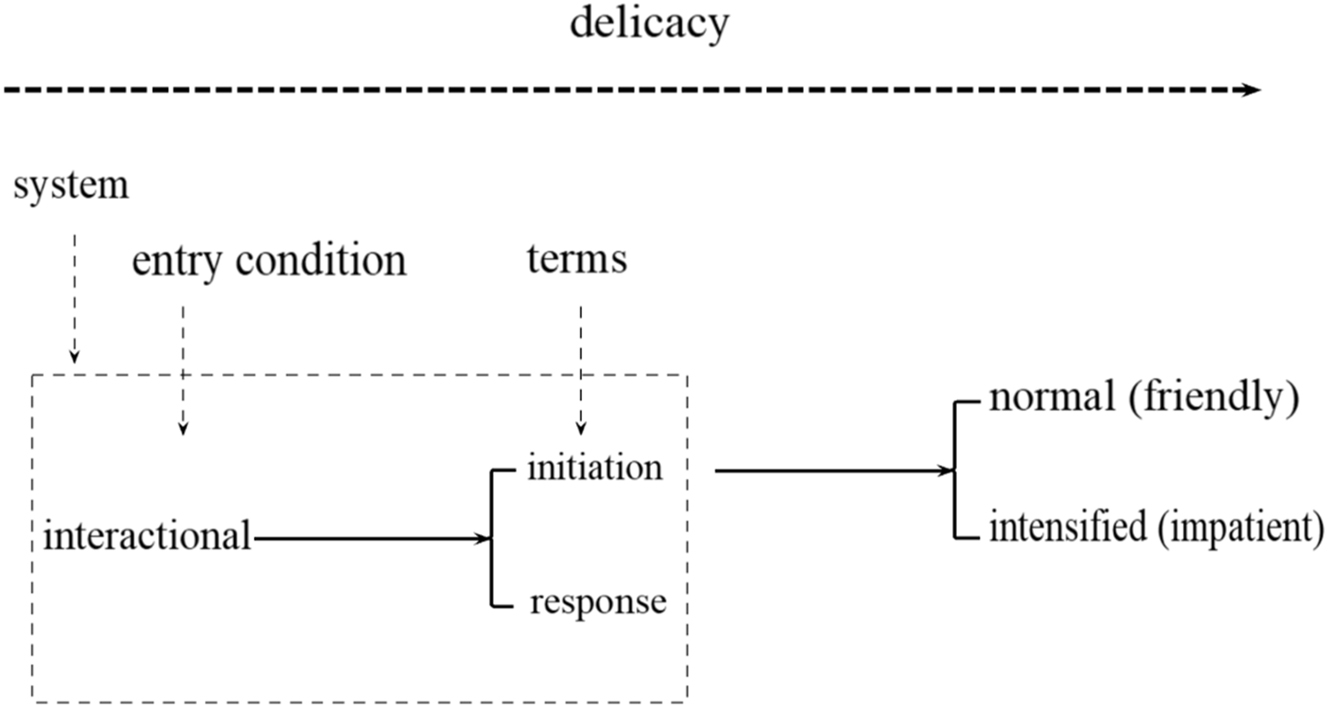

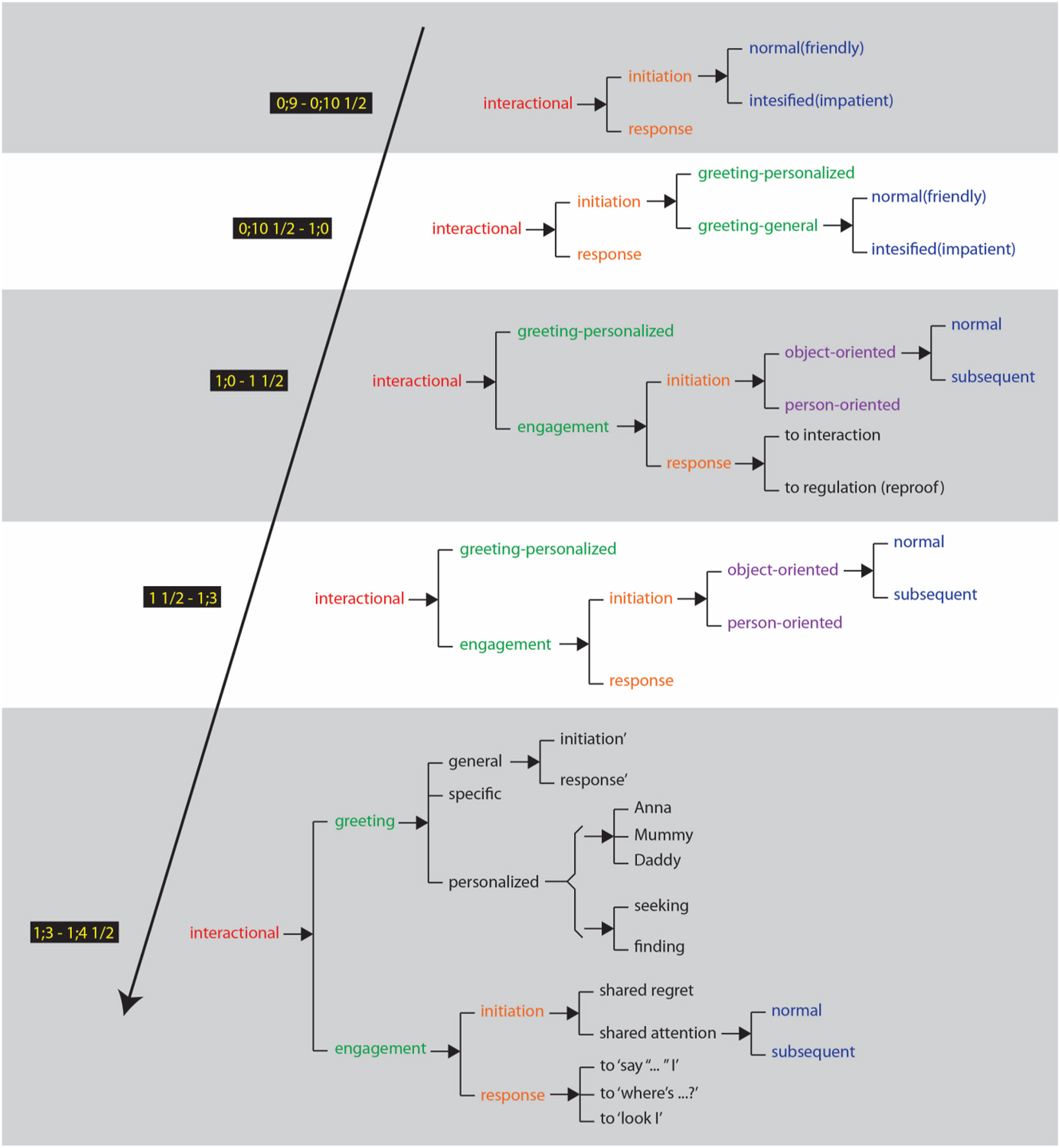

In a system network, the meaning potential of a language is represented by systems: two or more options (the terms of the system) that a language user chooses among under certain conditions (the entry condition of the system). In Figure 1, the system ‘initiation’ versus ‘response’ has the entry condition ‘interactional’. As illustrated here, through their entry conditions, systems may be ordered in delicacy: the term (option) ‘initiation’ is the entry condition to the more delicate system ‘normal (friendly)’ versus ‘intensified (impatient)’. This system network fragment can be interpreted declaratively as a statement of the meaning potential, but it can also be “read” as a process of choosing, e.g. ‘interactional’, then ‘initiation’, then ‘intensified (impatient)’. Systems may also be simultaneous, i.e. have the same entry conditions as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, which will be discussed below. Further, entry conditions may be complex combinations of systemic terms, conjunctive and/or disjunctive (Boolean combinations). Thus system networks are much more powerful and flexible than simple taxonomic trees. For a more detailed exploration of system networks, including other forms of display and complementary topological forms of representation, see Matthiessen (2023); and for a how-to approach, see Martin (2013).

Annotated example of a system, from Halliday’s (1975) description of the interactional microfunctional meaning potential of one child’s protolanguage.

The meaning potential of a language (semantics) is realized by its wording potential (lexicogrammar), which in turn is realized by its sounding potential (phonology) in spoken language, by its writing potential (graphology) in written language or its signing potential in sign languages.

While SFL-informed approaches to language have been widely applied to the field of language education since the 1960s – genre-based pedagogy being very popular, effective, and successful (e.g. Gardner 2017; Rose and Martin 2012), the idea of the system embodying the meaning potential of language in context, represented as a system network, has arguably not been sufficiently foregrounded and could be promoted to make a much more significant contribution to L2 education, where despite pioneering efforts (importantly, Byrnes et al. 2010) the uptake of SFL has been less than in L1 education (cf. McCabe 2017; Mickan 2019; and also McCabe 2021: Ch. 4). This does not mean that system networks are generally absent from SFL-informed studies in L2 educational contexts. On the contrary, it can be argued that a wealth of them draws on the concept of system networks in some way. What the present paper argues for is the potential benefits that the explicit use of system networks may bring to L2 teaching/learning. To that end, we revise some of the contributions to L2 education in existing studies and identify areas of interest that deserve further exploration (see Table 1 below).

Examples of systemic functional studies of language learning using system network.

| Use of system network | Domain | References | Section in our paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking language development | L1, longitudinal: learning how to mean (protolanguage), transition into mother tongue | Halliday (1975); Phillips (1986); Painter (1984, 1996, 2003 | Section 3.1 |

| L2, longitudinal: learning how write to mean in L2 | Xuan (2015) | Section 3.1 | |

| Diagnosing problems in student writing | L2: detecting over- and under-use of systemic options; error analysis | Gibbons and Markwick-Smith (1992); Zamorano-Mansilla (2004); Praxedes Filho (2013); Xuan (2015, 2018, 2022; Xuan and Matthiessen (Forthcoming) | Section 3.2 |

| Supporting sequencing in the curriculum | L2: determining curricular phases based on system networks (e.g. increase in delicacy, new regions) | cf. Gibbons and Markwick-Smith (1992) | Section 3.3 |

| Designing exercises based on options in system networks | L2 | Arús-Hita (2008, 2016, 2022 | Section 3.4 |

| Guiding L2 learners by means of system networks as cartographic tools | L2 | cf. Matthiessen (1995); Flores Calvo (2021) | Section 3.5 |

| Contrasting L1 and L2 resources based on multilingual system networks, representing shared potential and language specific potentials | L2 | cf. Bateman et al. (1999); Matthiessen (2015, 2018; Arús-Hita and Lavid (2001) | Section 3.6 |

| Supporting advanced L2 learners expanding their L2 uses by adding translation skills drawing on multilingual system networks | L2 | cf. Halliday (2013); Matthiessen (2014) | Section 3.7 |

Learning a L2 (second/foreign language) can be conceived of as learning how to mean in a new language (cf. Halliday 2007 [1978]). This involves learners gradually mastering the meaning potential of the new language , most likely against the background of their L1 meaning potential: in fact, they are very likely to create a multilingual meaning potential (e.g. Matthiessen 2018) involving both their L1 meaning potential and the L2 meaning potential they are gradually mastering – although the relationship between them will obviously depend on a number of factors, centrally including the L2 educational approach (e.g. monolingual vs. translanguaging; cf. Section 3.6).

In L2 education, system networks can be used in a variety of ways. For example, we can use them to profile L2 learners’ choices in their output in order to track their frontier in the expansion of their own meaning potentials, determining if there are parts of the systemic potential that they don’t access or areas that they over-use.

In this paper, we will take stock of the ways system networks have been used in studies concerned with L2 education and at the same time we will highlight new opportunities to empower new studies and applications based on system networks as a way of engaging with the central notion of learning how to mean in a second/foreign language. We argue that system networks can make a very significant contribution to L2 education if they are given more attention and their deployment is highlighted. There are quite a number of actual and potential uses of system networks in L2 education, including those set out in Table 1. Some L1 studies have been included which we consider represent good models on which to base applications to L2 contexts.

As said above, Table 1 does not cover all the uses of system networks which are found in the L2 educational literature; just those that will be expounded in this paper. There are other educational uses identified in the literature also worthy of attention in future research, and which, for reasons of focus and space, we cannot delve into on this occasion. One of those uses is, for instance, that of system networks as an assessment tool to evaluate students’ proficiency in a second language or foreign language. Liardet (2013, 2016 demonstrates that the use of system networks to highlight the different textual functions of grammatical metaphor in students’ writing – such as cohesion, reference, and coherence – can enable educators to better comprehend and differentiate students’ proficiency in a second or foreign language. System networks can in this way offer teachers the opportunity to assess students’ writing proficiency.

In the context of secondary education, Morton and Llinares (2018) illustrate the use of a system of appraisal to examine the development of attitudinal resources used by Spanish English L2 speakers in their history learning. This offers deeper insights into how different options from the appraisal system assist students in forming their views and interpreting the historical events they study. The same applies to the use of engagement systems in history classes in the US context (Bunch and Willett 2013).

Additionally, system networks complement traditional second language writing instruction by providing more metalinguistic knowledge for language teachers to support their students. Cheng and Chiu (2018) explore the application of genre-based pedagogy in teaching Chinese as a second language in Taiwan, China. Their study reveals that the use of system networks, particularly the lexicogrammar systems under the three meta functions in SFL, can effectively enhance the writing skills of students of Chinese as L2. This improvement was observed after explicitly scaffolding the learners on how to write in the Chinese genre.

All of the above shows that system networks do have great potential in the general context of education and the specific one of second/foreign language teaching and learning. Further revision of the existing literature on the use of system networks in L2 education is provided in the corresponding sections dealing with different areas of application of system networks.

We comment here on one of the uses identified in Table 1, and then explore the rest in more detail in Section 3. We will start with “designing exercises” because this will also provide us with an opportunity to introduce a few aspects of the system network fundamental to their use as a power tool in L2 education.

Designing exercises. It is possible to interpret traditional exercises designed to help learners master (word rank) paradigms such as noun declensions and verb conjugations as exercises based on system networks. However, they were less sophisticated in that they only involved the tabular intersection of certain features such as case and gender, person and number that can be described more powerfully by means of system network, and the focus was on teaching e.g. verb conjugations and noun declensions (as illustrated quite chillingly in the Latin lesson in Alf Sjöberg’s Swedish 1944 film Hets [translated into English as “Frenzy” or “Torment”] from a screenplay by Ingmar Bergman[1]) rather than on the mastery of the systems that underpin them.

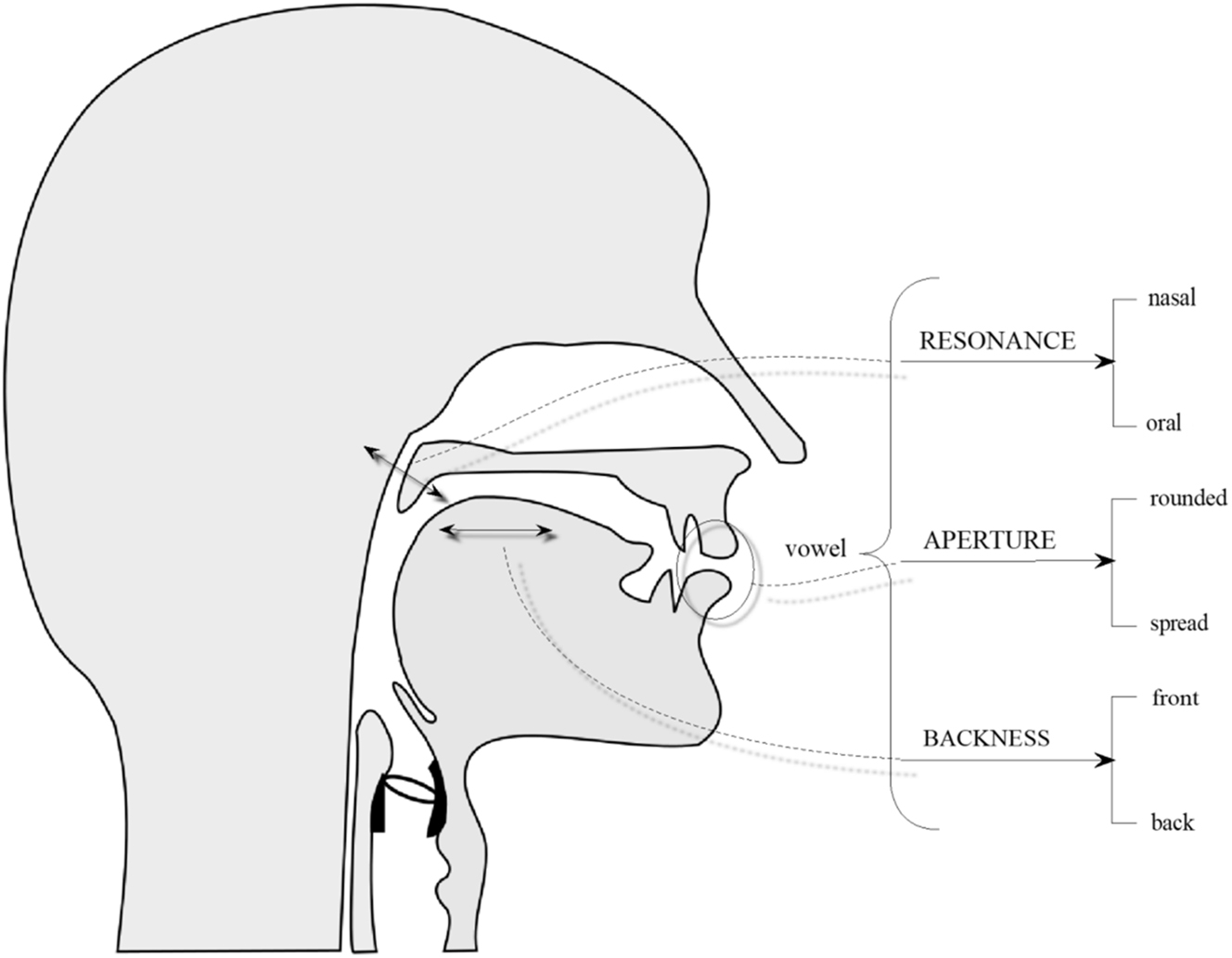

Simple exercises based on system networks include what we might call phonetic yoga (cf. Matthiessen 2015, 2022, 2023). One of the challenges L2 learners face is located at the expression plane of the language they are trying to learn; in the case of spoken language, this means the expression plane strata of phonology and phonetics: they have to master the sounding potential of the language they are engaged with.

At the rank of phoneme (if this rank is relevant in the language learners are working on; cf. Halliday 1992a; Matthiessen 2021), vowels in the learners’ L1 and L2 may involve the three articulatory systems of resonance, aperture, and backness. They can all be located in reference to our shared human articulatory potential (see Catford 1977), as shown in Figure 2. which gives us a basis for articulatory phonetic yoga, designed to help students become aware of the fact that speaking is a process of choosing among the options in sounding in the L2 they are learning and to help them explore possible options in our shared human sounding potential that may not be phonologized in their L1 but which have been in their L2. For instance, imagine that we are teaching French to a group of English-speaking students. In English, the systems of aperture and backness are not independently variable: ‘front’ vowels are ‘spread’ and ‘back’ vowels are ‘rounded’, but in French they are independently variable to some extent – specifically, ‘front’ vowels (if they are ‘high’, which is a value of a systemic parameter not shown in Figure 2), can be either ‘spread’ /i/ or ‘rounded’ /y/. So here exercises in phonetic yoga would help English L1 students vary aperture and backness independently of one another (And if for some odd reason, they were also trying to learn Swedish, their exercises would involve the same exercise as for French, but in addition they would also practice producing “over-rounded” back vowels as well as ‘rounded’ ones).

Three simultaneous vowel systems representing three sets of articulatory options (e.g. ‘nasal’ vs. ‘oral’) that can be explored by means of phonetic yoga.

Naturally, the range of systemic parameters involved in exercises in phonetic yoga will depend on the particular combination of L1 and L2 languages. For example, if speakers of English are trying to learn Akan, we would introduce them to the systemic distinction between neutral and advanced tongue root position, helping them with exercises where they learn to shift the whole vowel system by advancing their tongue roots.

The very simple system network in Figure 2 says that for ‘vowel’, there are three simultaneous systems, viz. resonance, aperture, and backness. This is just a sketch of part of the human articulatory potential relevant to domain of vowels (for further systemic discussion, see Matthiessen 2021). As we have noted, in the phonology of any particular language, this general articulatory potential will be “phonologized” in some specific way. The systemic description of the language will bring this out, and the point of phonetic yoga is precisely for learners to explore their articulatory potential so that they can expand it to the point where they can master the sounding potential of their L2.

2 System networks: the representation of language as a meaning potential

As noted above, Halliday developed system networks in order to be able to represent language as a resource for making meaning – as a meaning potential. This move was necessary since he was the first linguist to the give primacy to the paradigmatic organization of language (cf. Halliday 2002 [1966]; Matthiessen 2023). Since he introduced them in the 1960s, system networks have been used extensively to represent the semantic, lexicogrammatical, and phonological resources of a fairly wide range of languages (see e.g. Kashyap 2019; Matthiessen and Teruya 2023; Mwinlaaru and Xuan 2016; Teruya and Matthiessen 2015).

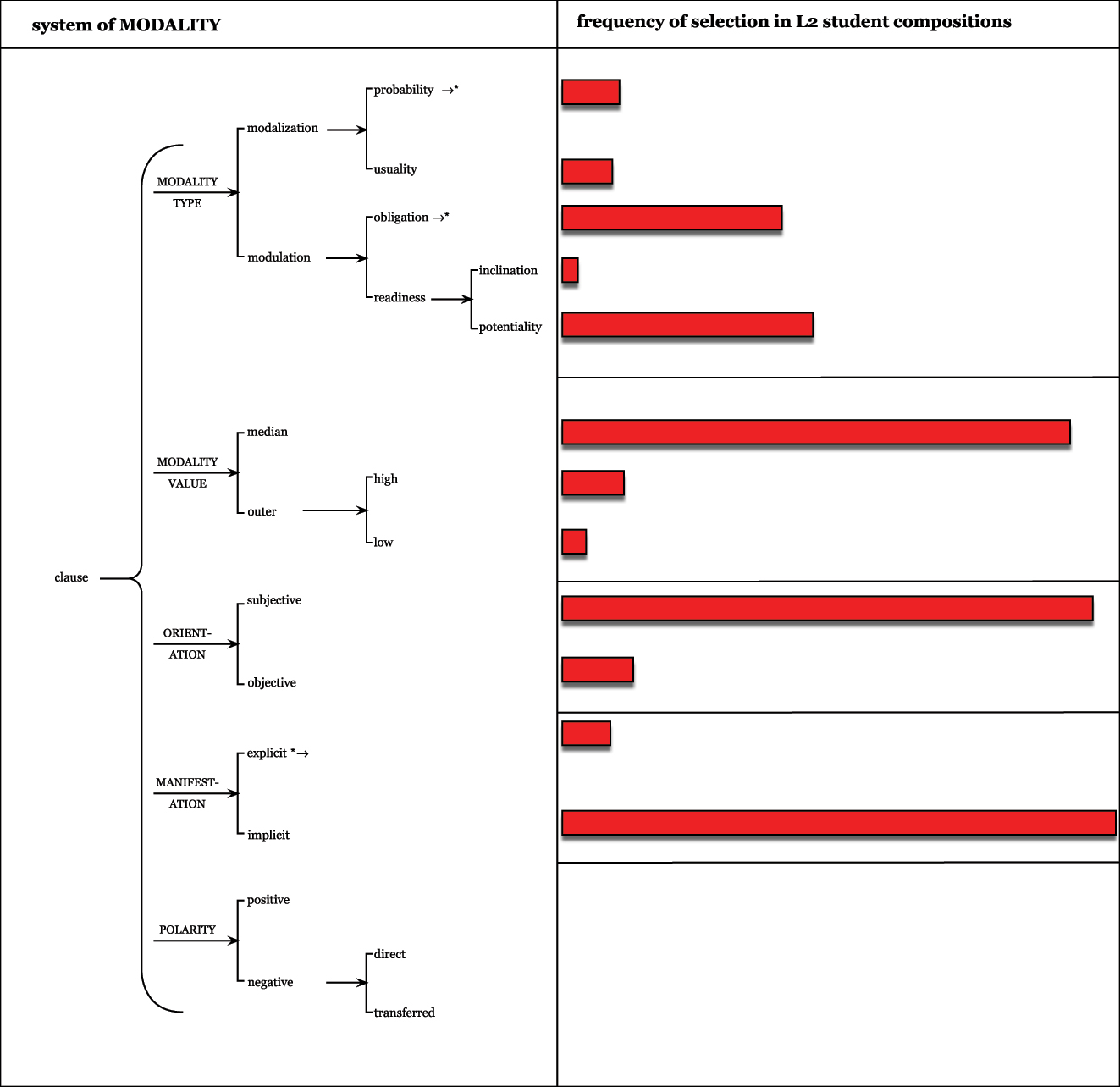

To give an initial indication of the power of system networks in L2 education beyond the simple example above of supporting phonetic yoga (Figure 2), we will briefly review one “classic” study where the system network plays the central role – a resource teachers can use in analysing their students’ output to diagnose problems[2] (see further below, Section 3.2). This is Gibbons and Markwick-Smith’s (1992) demonstration of the value of Halliday’s systemic description of modality in English (first presented in Halliday 2005 [1970], and then in revised form in the editions of Halliday’s IFG, Chapters 4 and 10).

Their contribution can be seen against the background of Wilkins’ (1976) proposal for a notional syllabus (cf. the much earlier contribution by Hornby 1954: Part 5 “Various concepts and how to express them”). Gibbons and Markwick-Smith’s (1992: 39) emphasize the value of the systemic organization of the resources of modality,[3] in comparison with a list such as Wilkin’s taxonomy:

To illustrate the nature and use of a Systemic semantic description, the area of modality in English will be used. This area traditionally causes considerable problems for second-language learners, particularly the meaning and use of modal verbs themselves. For comparison one must look at Wilkins (1976: 40–41). It can be seen that Wilkins’ taxonomy is in essence a list, although the numbering indicates more organisation than Brumfit allows. Formal realisations are numerous and are examples only, and no semantic or stylistic differentiation is made among them. Some of the semantic contrasts are embedded in running text. All of this makes it difficult to base teaching on this taxonomy and renders the semantic analysis of error almost impossible. (Gibbons and Markwick-Smith 1992: 39)

They then present Halliday’s (1985) description of the system of modality, and include his system network, which we have presented here in an adapted version together with a paradigm of examples: Figure 3. They comment on the advantage of the systemic description of modality, or any system of language, over a list of notions – even if it embodies some further organization; they write:

It can be seen that this is a system rather than a list, meeting one of Brumfit’s strongest objections [to Wilkins’s notional syllabus, JA-H, CMIMM & WX]. It presents a clear picture of the major choices available in the English modality system. An important difference from Wilkins’ model is that several semantic choices must be made simultaneously in order to arrive at a possible formal exponent [i.e. realization, JA-H, CMIMM & WX]. The left-to-right axis is one of increasing semantic delicacy. In as far as the language system itself can predict acquisition order (this must always be balanced against external demands and psychological factors such a processing constraints), it would predict the acquisition of the left-hand grosser distinctions before the right-hand more delicate semantic distinctions. (Halliday 1985: 39)

Based on these and other comments in their article, we can see the value of the system network as a cartographic tool (see further Section 3.5); it gives us a very clear and explicit map of the resources in the language – resources that second/foreign language learners must gradually master. However, they then go on to demonstrate additional value of the system network: they show that it can be used as a diagnostic tool in the analysis of learner output – to “analyse error and absence” as they put it (see further Section 3.2). Using system networks like that of modality, it is possible to analyse written (and of course also) spoken output by learners in order to profile their selections (their choices of systemic options such as ‘modalization’ vs. ‘modulation’) – making possible a comparison with the output by native speakers addressing the same tasks.

Part of the system network of modality in English (adapted from Halliday and Matthiessen 2014).

In their article, Gibbons and Markwick-Smith (1992: 43) report on the findings of their analysis of two compositions:

In the two compositions by the Hong Kong learner, there is a noticeable and sometimes inappropriate under-use of modality. Some areas of the modality system are reasonably represented however – she does not appear to have problems with adverbial exponents of ‘usuality’ – she uses often, never, always and seldom. Similarly, there are a number of correct uses of explicit markers of modality, both objective e.g. it is possible that and subjective e.g. I think that, I find that. It is in the implicit area – in practice this usually means modal verbs – that the problem is found. Notice, incidentally, the utility of the network display in detecting both developed and underdeveloped areas. Although the learner is of intermediate standard and has an extensive vocabulary, the only modal verb used correctly is can […]. (Gibbons and Markwick-Smith 1992: 43)

Once problems in learner output have been diagnosed systemically, one can move on to a consideration of treatment, or “remedies”; Gibbons and Markwick-Smith (1992: 44) comment: “Using the system network, then, we are able to show that remedial treatment is required in the ‘subjective implicit’ expression of various types of modality.” They then go on to suggest four stages in an “instructional cycle” (Gibbons 1989): Stage 1 – Focussing > Stage 2 – Recognition > Stage 3 – Guided practice > Stage 4 – Application. Throughout this staged process, the system network can serve as a point of reference – a map of the resources to be taught and learnt.

Having reviewed key characteristics of system networks as representations of language as a resource for making meaning, a meaning potential, and briefly illustrated applications in L2 education, we will now examine seven areas of application in some more detail.

3 Areas of application of system networks in L2 education

There are quite a number of actual and potential uses of system networks in L2 education, as indicated in Table 1 above. We will touch on these uses, highlighting those that have perhaps given the least attention in L2 education drawing on SFL, but which look very promising as we move ahead in the next couple of decades – including the helical return to contrastive linguistics (e.g. Lado 1957) in the service of L2 education but now empowered by current SFL rather than American structuralist linguistics of the 1950s: the conception of language as a resource for making meaning in context (a meaning potential), the understanding of L2 learning as learning how to mean in a the second language, the interpretation of learning how to mean in a second language supported by the theory of the multilingual meaning potential.

3.1 Tracking language development systemically

System networks were first used in tracking L1 language development in longitudinal case studies of young children “learning how to mean”, to use Halliday’s theoretically informed formulation. They enabled researchers to track young children’s meaning potential starting with the protolinguistic potential around the age of 5–8 months, showing how they gradually expanded it and also how they re-arranged it before making the transition into the mother tongue spoken around them sometime in their second year of life. The application of system networks to tracking L2 language development is still almost uncharted territory. Xuan’s (2015) longitudinal study is an isolated example of how to track learners’ writing systemically. Because we believe that there is great potential for further studies in this area, let us in this Section show how this has been done in L1 contexts so it may serve as a source of inspiration for potential application to L2 contexts.

In a pioneering longitudinal case study, Halliday (1975) initiated a systemic analysis of one child’s, his son Nigel’s, language development from birth, making this project a seminal work in the application of systemic theories to track language learning progress. Halliday began his systematic examination of Nigel’s language when Nigel was 9 months old, and it continued until he reached the age of 3.5 years.

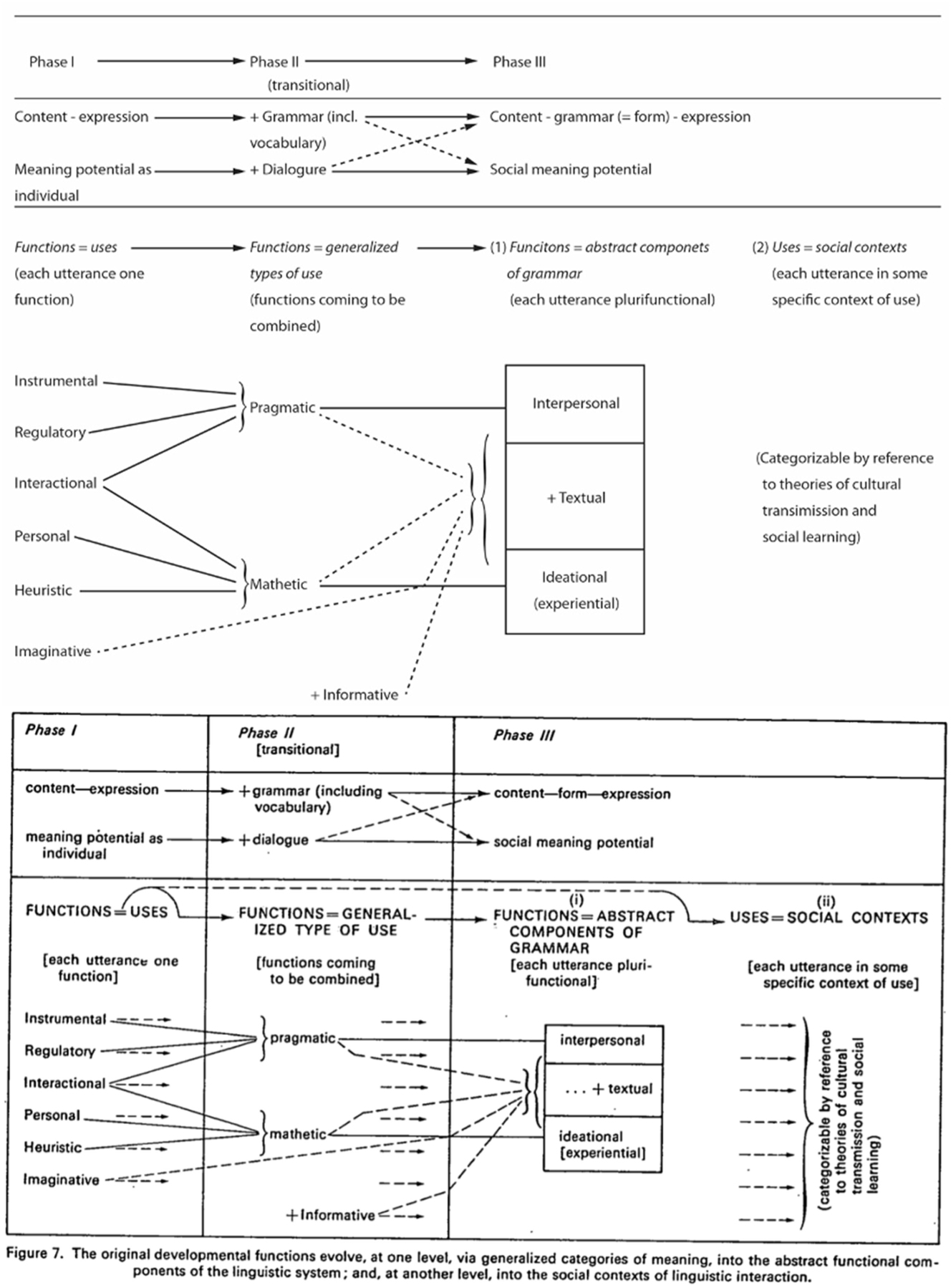

Halliday collected 2.5 years of longitudinal data on Nigel’s language development, documenting his transition from an infant to a fluent English speaker. He examined various language functions and captured Nigel’s facial expressions, vocalizations (both articulatory and prosodic), and gestural aspects of his body language. Halliday identified three phases of language development – Phase I (protolanguage) > Phase II (transition from protolanguage to the mother tongue) > Phase III (learning the mother tongue). They are summarized in Figure 4 below, together with critical “architectural” properties having to do with stratification and functional organization.

Summary of functional development (Halliday 1975: Figure 7).

As shown in Figure 4, in Phase I, protolanguage, Halliday identified six functions in the first phase of his son’s language development. These functions, derived from children’s protolanguage use, are microfunctions. That is, they are separate meaning potentials tied to particular contexts of use; they are mutually exclusive in that Nigel selected options within one microfunction in its context or another – at this stage, he was not able to mean more than one thing at the same time (in other words, language was not plurifunctional; each utterance instantiated one microfunction).

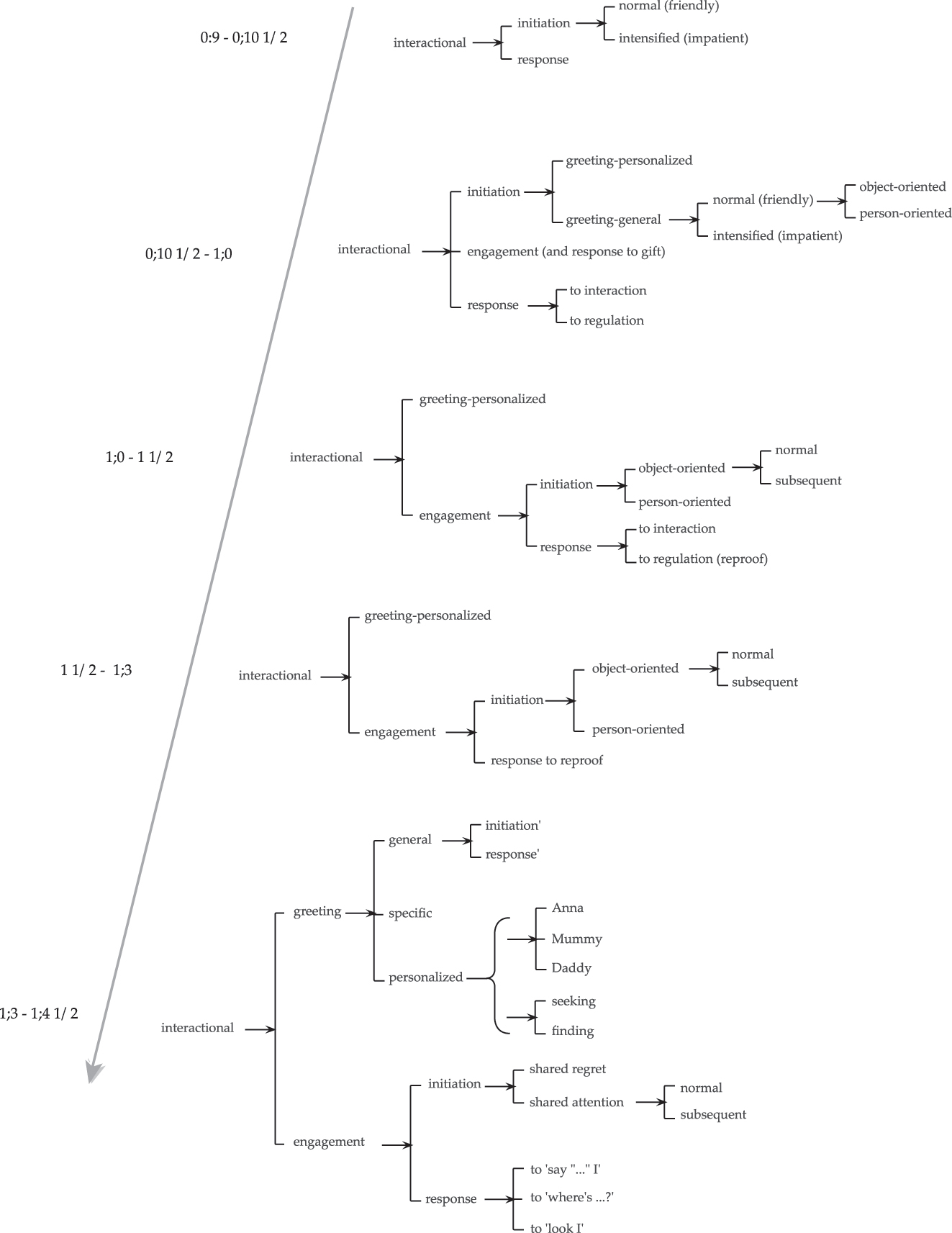

During Phase I, Nigel expanded his microfunctional meaning potentials, and Halliday represented systemic snapshots of them at six-week intervals. We have illustrated this for the interactional microfunctional meaning potential in Figure 5, showing successive versions of this growing potential. As can be seen from the successive versions, Nigel gradually elaborates the original options of ‘initiation’ and ‘response’, splicing in a less delicate distinction in the third version (1;0 – 1 1/2), viz. ‘greeting-personalized’ versus ‘engagement’. In the final version (1;3 – 1;4 1/2), there is an entirely new development: for ‘personalized’, Nigel introduces a distinction in content between naming the person greeted (‘Anna’/‘Mummy’/‘Daddy’) and the orientation (‘seeking’/‘finding’). These are the first simultaneous systems in his protolanguage – a preview of the later metafunctional simultaneity of experiential and interpersonal systems, and he creates this possibility by teasing apart articulation (naming the person) and prosody (orientation) within the expression plane. Thanks to the nature of representational power of system networks, it is possible to bring out this very significant semogenic development. It is also the nature of system networks as representations of paradigmatic organization – the organization of language as resource – that makes it possible to capture the continuity throughout the three phases of language development.

Successive versions of Nigel’s interactional microfunctional meaning potential (based on Halliday 1975).

During Phase II, the transition from protolanguage into the mother tongue (16.5–18 months), Halliday discovered that the six microfunctions observed in the first phase were transformed into two general macrofunctions: mathetic and pragmatic. These still constituted distinct meaning potentials; i.e. Nigel either chose options in the mathetic system network or in the pragmatic one, but this functional generalization from the more specialized microfunctions paved the way for the next phase, where the generalized macrofunctions were transformed into more abstract, simultaneous, metafunctions. They can now be represented as simultaneous systems in the units of language. During Phase II, Nigel developed an expanded vocabulary and emergent grammatical structure, and improved language mastery, enabling him to control his surroundings through language.

Phase III (18 months onwards) marks the child’s language development transitioning to adult language. Based on his longitudinal case study of Nigel, Halliday was able to show that the abstract metafunctions of post-infancy, adult language actually emerged from earlier phases of functions, first microfunctions and then macrofunctions.

From protolanguage to one-word utterances, short clauses, and ultimately fluent language use, Halliday’s study of Nigel’s language development has been groundbreaking in the field of systemic functional linguistics. The wealth of evidence and empirical data gathered has laid the foundation for the theory of systemic functional linguistics and established this study as seminal in utilizing system networks to analyse language development.

In addition to Halliday’s work, the idea of system networks has been applied to the study of other young children learning how to mean, initially by Clare Painter and Jane Torr (e.g. Torr 1997). Painter (1984, 1996, 2003 continued Halliday’s research first in Painter (1984) and then in Painter (1996, 1999, where she followed her two sons’ language development from 9 months to 4 years old showing how they learnt through language as they were learning language. In Painter (2003), she examined the development of the resources of appraisal. This study differs from Halliday’s in a couple of respects. Firstly, she focuses solely on her sons’ interpersonal meaning-making, narrowing down the research scope – more specifically, attitudinal resources. Secondly, her study involves her two sons at different developmental stages, ranging from 2 to 6 years old.

Painter’s study has successfully outlined her sons’ interpersonal meaning-making development and contributed additional insights to Halliday’s original work. For instance, children employ various semiotic resources to express their attitudes at an early stage, even using their protolanguage to convey emotions. Starting at the age of 2, children begin using judgement and appreciation to evaluate their surroundings. After 2.5 years old, they employ a more nuanced set of adjectives to express attitudinal meanings. Painter’s project systematically maps out the attitudinal resources children develop during infancy and demonstrates the effectiveness and intricacy of system networks for tracking language development.

System networks have been proven useful for tracking language functions and interpersonal meaning-making, such as the use of appraisal resources. At the same time, they have been employed to track children’s development of ideational grammatical metaphor. Thus, Derewianka (1995, 2003 continued this line of research by investigating the metaphorical language development of her son, Nick. She collected his writing samples from the ages of 8 to 13, focussing on the ontogenetic perspective of children’s language development. Derewianka discovered that children only begin using metaphorical language in their writing once they enter secondary school and start learning content courses, such as history.

Derewianka successfully summarized the development of ideational grammatical metaphor in her son’s written language development. She applied the systemic idea to categorize the grammatical metaphors collected in her study and compiled a list of findings within the system of grammatical metaphor. This research supports Halliday’s hypothesis that (ideational) grammatical metaphor emerges at a later stage in children’s lives when they begin constructing knowledge during their learning journey.

3.2 Diagnosing problems in L2 student texts

As we have seen, when we use system networks to track language development during Phase I of learning how to mean, we represent successive versions of a particular microfunctional meaning potential at certain intervals (Figure 4). Consequently, the system networks change in the course of tracking the development in order to represent successive states of the meaning potential. In contrast, when we use system networks to diagnose problems in language learning – in L2 learning in particular – we are likely to use a single system network as a reference description of some area of the language such as speech function, modality, transitivity or intonation, and use it to analyse learner output, either spoken or written. We thus use the system network as a reference description of the L2 “target”. Against this reference network, we can profile selections made by learners, bringing out patterns of usage in their output. Naturally, we can interpret their patterns of selections as transitional states of their own personalized learner potentials, representing their path towards the L2 system they are trying to learn (This will very likely also include variation in the relevant realization statements, as when L2 learners of English overuse do or be as Finite).

Using system networks to diagnose problems in L2 student texts is not a new topic, and it has garnered increasing research attention in foreign/L2 language education. Various findings from different contexts have deepened our understanding of the system network’s application in language education. For example, in Section 2, we reviewed Gibbons and Markwick-Smith’s study (1992) based on the system of modality as a reference description of the resources in English.

Similarly, Xuan and Matthiessen (Forthcoming) analysed EFL learners’ use of modal resources in a Chinese context. They applied the system of modality to study writing tasks completed by two groups of Chinese EFL (English as a Foreign Language) learners attending an elite high school in China. The term “elite” refers to the school’s reputation for outstanding academic performance. The two groups of students, representing different proficiency levels in their local system (secondary 3, aged 14–15, and secondary 6, aged 16–18), were given the same writing prompt. The authors hypothesized that secondary 6 students would demonstrate better mastery of the system of modality in their writing and, therefore, mature and proficient use of modal resources. However, the findings showed no significant differences in the use of modal resources between the two groups. The frequencies of choices for the first group are shown in Figure 6.

Frequency of choices of options in the system of modality in English L2 writing by Chinese high school students (based on Xuan 2015).

In other studies, Xuan (2015, 2018, 2022 employed the system of transitivity, specifically process type and circumstantiation, to examine Chinese EFL learners’ use of process types and circumstances in their EFL writing from a longitudinal perspective. This study concentrated on the natural written output produced by EFL students in China, with no interventions related to SFL made during the course of the research. The study found that the use of process types exhibited registerial differences in these learners’ writing, although no significant progress was observed over the one-year study period. Furthermore, the use of process types indicated students’ English proficiency levels, as the majority of processes employed in their writing consisted of simple, concrete, and less delicate verbs. These findings offer valuable insights for curriculum and material developers, emphasizing the importance of incorporating system networks in their work.

Additionally, system networks have been utilized to evaluate the repertoire of L2 learners’ interlanguage and target language. Praxedes Filho (2013) examined the use of academic English by non-native English speakers in a Brazilian context to understand how system networks can be employed to study the system of interlanguage, particularly in relation to their fossilization patterns. By comparing the patterns of the L2 learners’ interlanguage with the target language repertoire, they discovered that L2 learners’ interlanguage fossilization follows certain patterns. This finding can be used to enhance the teaching and learning of L2 development.

These studies demonstrate that system networks can serve as diagnostic tools to track and identify students’ learning outcomes and their meaning-making repertoire regarding specific language resource systems. This research highlights the potential of system networks in informing targeted instruction and promoting L2 learners’ language development.

3.3 Supporting sequencing in the curriculum of the learning of the L2 meaning potential

So far, we have shown how system networks can be used to “monitor” learners as they progressively learn how to mean, either by tracking successive stages or by diagnosing potential problems at some particular stage of learning, typically in order to intervene with remedial materials. However, system networks have also turned out to be a significant guide to L2 educators as they develop learning materials and even curricula. This is because system networks constitute maps of the L2 resources students need to master to become proficient users.

System networks offer the possibility of organizing learning materials in a sequential manner, progressing from simplicity to complexity. One example from the literature is the German as a foreign/heritage language program at Georgetown University. Byrnes and her team adopted the Sydney School’s[4] genre classification system into their curriculum, arranging texts and related lexicogrammatical resources to support student learning (Byrnes 2009a, 2009b). This gradual complexity-building pedagogic strategy was implemented effectively thanks to the comprehensive description represented by the system network (Ryshina-Pankova 2015; Ryshina-Pankova and Byrnes 2017). As a result, various lexicogrammatical resources from different systems were taught systematically and incrementally, enhancing the teaching and learning of German in the program. In contrast, the notional syllabus, a well-known approach for organizing lexicogrammatical resources in foreign/L2 programs based on communicative functions and conveyed notions, lacks systematicity, as it fails to integrate system networks into the curriculum design (cf. the remarks by Gibbons and Markwick-Smith 1992, cited as part of their work in Section 2 above).

System networks enable the contextual arrangement of linguistic resources. For instance, Silvia Pessoa and her team at CMU (Carnegie Mellon University) Qatar identified challenging linguistic resources from different systems based on the curriculum and L2 students’ linguistic challenges (Miller and Pessoa 2018). They combined these resources with a genre-based pedagogy in their program, mapping out the linguistic resources that proved difficult for students when composing case analyses and argumentative essays. For example, they utilized the system of engagement (e.g. Martin and White 2005) in historical texts and the system of macro/hyper theme (e.g. Martin and Rose 2007) in argumentative writing (Miller and Pessoa 2016; Miller et al. 2014). These applications have advanced the teaching of language across the curriculum in the Middle Eastern context and underscore the importance of using system networks to sequence linguistic resources in various contexts.

A curriculum sequenced with the system network approach can provide learner-centred instruction. This method allows educators to tailor the curriculum to address individual learners’ unique needs and challenges. As an example, Tong and her team in a Hong Kong community college diagnosed linguistic challenges faced by students and developed a series of specific writing courses (Tong et al. 2019). They identified linguistic challenges in student writing and interviewed content teachers who taught these students. Based on their empirical findings, they discussed possible solutions with language instructors and eventually mapped out the challenges, developing out-of-class workshops to support these EFL learners in becoming better writers in their profession.

In conclusion, the use of system networks in addressing language teaching issues is not a new concept, but it has gained increasing popularity in the field. Curriculum designers can benefit from integrating system network ideas into their designs, as supported by numerous empirical findings.

3.4 Designing exercises based on options in system networks

As we have shown, when descriptions of languages are represented by means of system networks, these networks can guide educators as they develop learning materials and even curricula. Here they thus serve as maps of linguistic resources that inform educational processes in the classroom, but as in the case of diagnostic uses of system networks, they may remain entirely implicit for learners. However, system networks can also serve as a direct powerful learning resource for L2 teachers and learners in the classroom.

Since, as we have seen, system networks include the linguistic options available to speakers, we can expect contextualized L2 teaching to benefit from the consideration of such options at the time of, not only designing activities, but also selecting the texts, whether written or spoken, articulating a given lesson. Of course, as is widely held, L2 teaching texts are best when made up of authentic material (see, for instance, Akbari and Razavi 2015). However, finding original texts which include different options from a given system may not always be possible. In such cases, following accepted practice in proficiency oriented L2 teaching methods (see Liu 2016), the best solution would be to adapt authentic materials so as to include in them realizations of the desired systemic options.

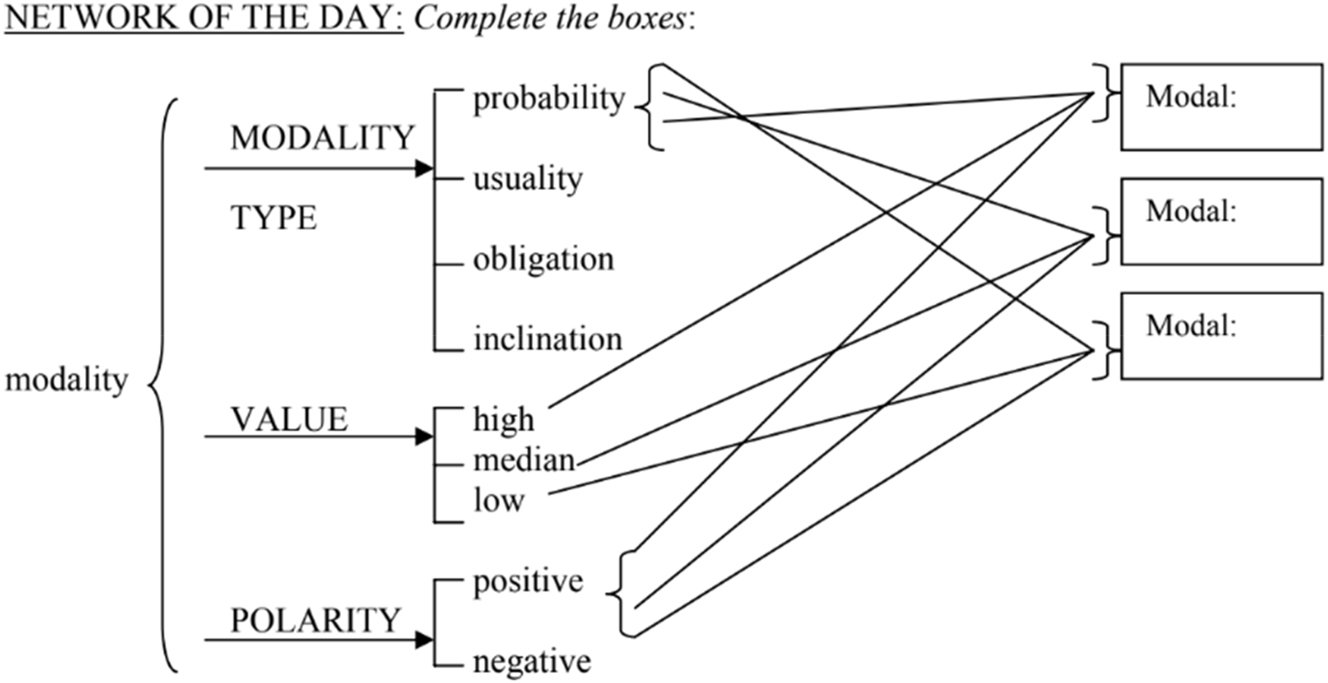

An alternative would be to create texts from scratch, provided one has the necessary resources and/or narrative acumen (French in Action, a French as L2 method, is a nice example of this [Capretz et al. 2012]). In Arús-Hita (2016), an example is provided of one such EFL lesson, together with the results from a satisfaction survey carried out among 32 university students working with the lesson. In the survey, students rated their learning experience 4 out 5, which is a good starting point. Since SFL is the theoretical framework underpinning the design of that learning unit, which addresses the system of mental transitivity, it can be expected to lend itself quite readily to the inclusion of system networks. Arús-Hita (2008) makes a first foray into the pedagogical use of system networks, in this case for the teaching of modality. One example given there is the one shown in Figure 7, where a system network is used for a review of the lexical realizations resulting from choices in the system network of English modality (see Figure 3).

Use of a system network for reviewing English modality (Arús-Hita 2008: 374).

In the same paper (i.e. Arús-Hita 2008), the following reasoning is given to support the pedagogical use of system networks in FLT (Foreign Language Teaching):

system networks reflect choices that we actually make when we speak and L2 learners are, unlike native speakers, aware of those choices. Native speakers make their linguistic choices in an intentional yet automatic or unconscious way, which contrasts with the more or less conscious way – depending on their proficiency level – in which foreign language speakers make their choices. Therefore, provided that they avoid complex terminology, e.g. by using probability instead of epistemic, system networks give learners the opportunity both to relate the lexicogrammar to semantics and to recreate the mechanics of actual speech production. (Arús-Hita 2008: 374)

Bringing students’ attention to the concept of choice in language can be an eye-opener. Making them aware that they are constantly making choices in their own mother tongue – sometimes rather consciously, as, e.g. when writing a term paper or speaking in public – can foster an appreciation for the visual representation of language as choice, i.e. system networks. At this point, it is important to stress that we are not proposing the use of system networks as the main means of instruction. The modality choices shown above, for instance, are best taught in the context of real reading and writing, system networks arguably providing useful practice or revision.

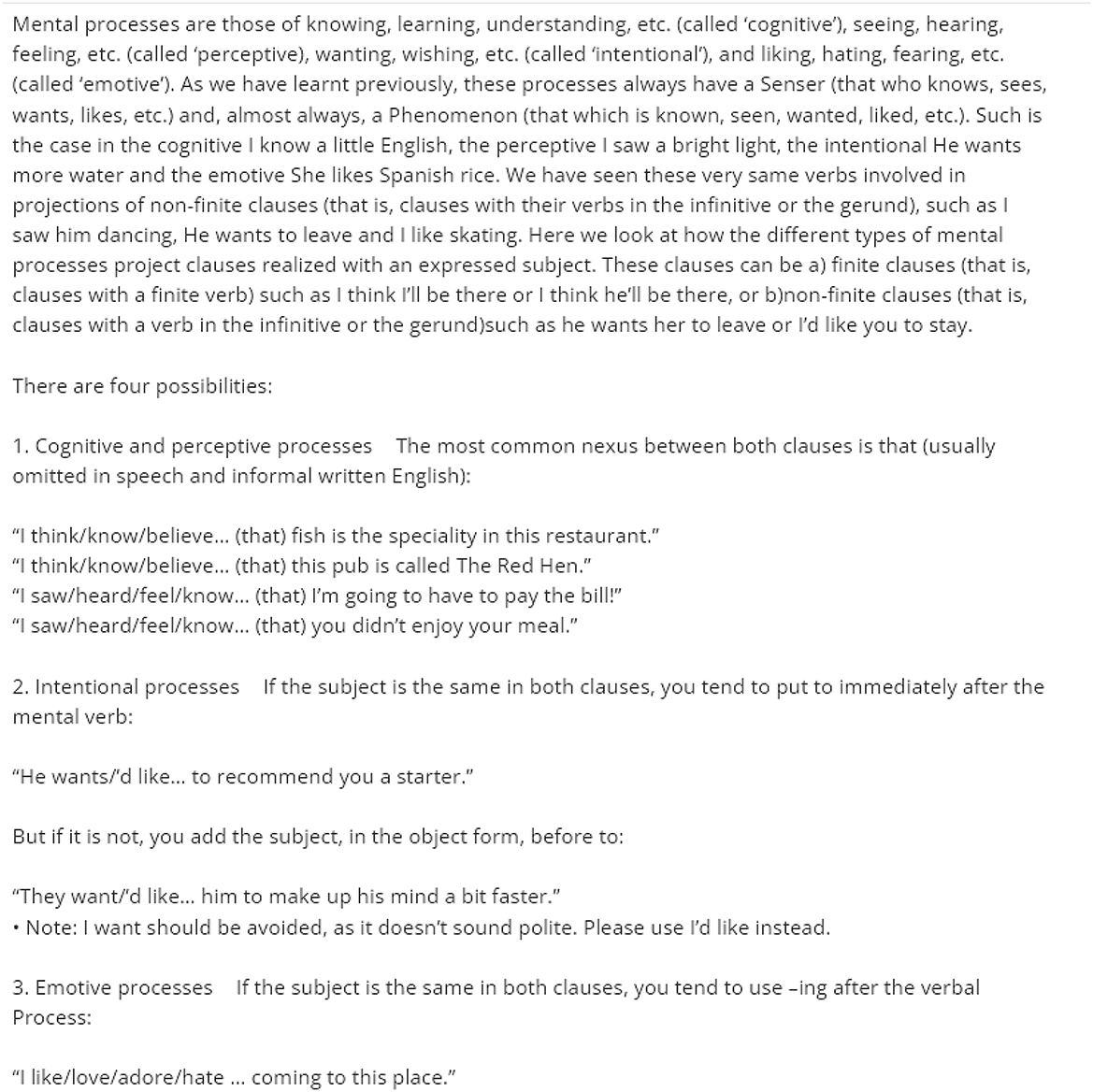

The example illustrated by Arús-Hita (2008) for the system of modality can be easily applied to other areas of the lexicogrammar. Arús-Hita (in preparation) gives a detailed account of the use of system networks for the teaching of English mental transitivity, not just for reviewing purposes but also for the actual teaching of that area of the lexicogrammar. It goes without saying that system networks are best exploited when integrated into a functionally motivated teaching unit, starting with an adapted text in the way hinted at above.

Even if one may not feel comfortable using them explicitly when teaching a foreign or second language, system networks can still be helpful. Thus, when speaking of the use of system networks in L2 teaching, one does not necessarily have to think of making learners work directly with them (see, however, the following sections for the explicit use of system networks with learners). Rather, system networks may be used as the driving force behind the design of certain activities, as previously mentioned. For instance, a system network for modality such as the one seen in Figures 3 and 7, above, or one for mental transitivity like the one in Figure 8, below, may be used by instructors and/or teaching material developers as a guide to the different lexicogrammatical points to be covered in a given lesson.

![Figure 8:

English mental transitivity system network (after Matthiessen 1995: 256).

Learners do not need to be exposed to the arguably complex terminology of the system network in Figure 8, as can be seen in the exploitation illustrated in Figures 9 and 10. However, and to facilitate the correct understanding of the system network to those readers not familiar with SFL, the following clarifications may be helpful. Middle processes are those not having an Agent (e.g. [Senser/Medium:] I [Process:] like [Phenomenon/Range:] chocolate), while effective processes have an Agent (e.g. [Phenomenon/Agent:] chocolate [Process:] pleases [Senser/Medium:] me). The Senser, usually human, senses (i.e. feels, likes, hears, knows, etc.) Phenomena, which can be realized by noun groups, as in the

kid wants

a new toy

, in which case the feature ‘phenomenal’ is chosen in the system, or by different kinds of clauses, in which case the feature chosen is ‘hyperphenomenal’, as in I saw the kid

playing with her new toy

(macrophenomenal) or the

kid thinks

that she deserves a new toy

(metaphenomenal). For a more detailed account of mental transitivity, see Halliday and Matthiessen (2014: §5.3).](/document/doi/10.1515/jwl-2023-0056/asset/graphic/j_jwl-2023-0056_fig_008.jpg)

English mental transitivity system network (after Matthiessen 1995: 256).[5]

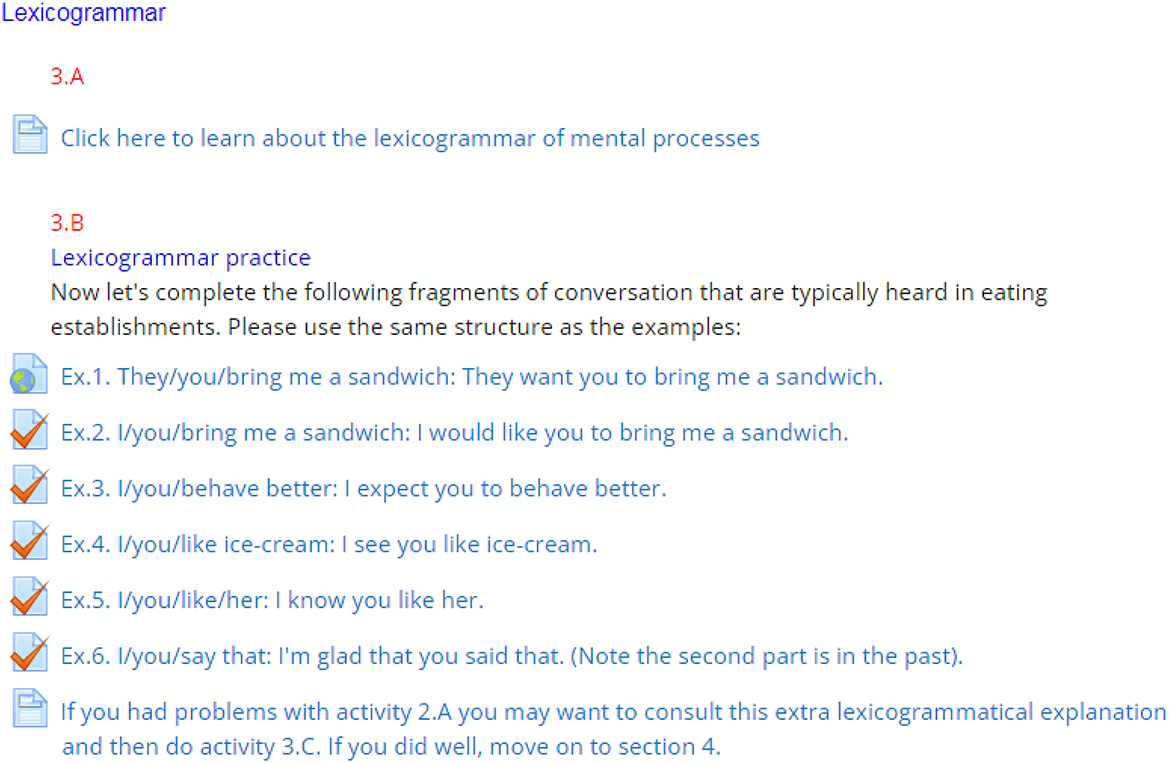

Figures 9 and 10 show examples of an activity which draws on the options available in the system network in Figure 8. In Figure 9, we can see that the activity starts by offering access to an explanation of the lexicogrammar of mental processes (notice the use of systemic terminology). That explanation is shown in Figure 10, which tries to capture, among other things, the distinction among different mental process types, as well as realizational specifications, from the system network above. Coming back to Figure 9, the activities which learners are requested to carry out, are intended for the practice of that very same lexicogrammar (see Arús-Hita [in preparation] for a more detailed account).

Lexicogrammatical activity based on the English mental transitivity system network.

Lexicogrammatical explanation based on the English mental transitivity system network.

3.5 Guiding L2 learners by means of system networks as cartographic tools

We now turn to the more explicit uses of system networks in teaching-learning processes. One such obvious use is their exploitation as cartographic tools for guiding L2 learners. Yet before zeroing in on the use of system networks to guide learners in their learning process, we can point out that SFL in general, and system networks in particular, have been recognized as useful guiding tools in L2 instruction. There is a wealth of research on the use of SFL to train or assist language instructors (e.g. Chappell 2020; Coffin et al. 2009; Gebhard 2010; Gebhard and Accurso 2023; McCabe 2025), some of it even using system networks to that purpose. A good example of the latter is Flores Calvo (2021), where system networks of pedagogic speech functions and pedagogic intermediations are provided, which may ultimately be of great help for ESL (English as a Second Language)/EFL instructors to teach more effectively. Flores Calvo’s network of pedagogical speech functions – based on the combination of Halliday’s description of the semantic system of speech function (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014) and Halliday’s (1993) three modes of language learning (i.e. learning language, learning through language and learning about language) in his notes towards a language-based theory of learning – allows us to capture the different realizations unfolding in the ESL classroom dialogue (hence ‘pedagogical’) in the speech functions of both teachers and students (Flores Calvo 2021: 67–69). The network of pedagogical intermediations, in turn, seeks to capture the different ways of scaffolding instructors’ knowledge so as to better help their students in the learning process (Flores Calvo 2021: 369).

As seen, the research just mentioned focuses mainly on L2 instructor guidance. There is, therefore, an important gap here, as no research exists specifically addressing the use of system networks to guide students in their learning process. It may be that there is a certain apprehension in the use of what might arguably be considered not very transparent terminology and/or conventions associated with SFL in general and system networks in particular. To address the former, scholars have attempted to debunk the myth that SFL is too difficult a framework to be used in educational contexts – see Playfair (2022); Raynor (2022); Monbec (2022). Monbec, for instance, draws on work by the Sydney School (e.g. Martin 1998) to defend the importance of recontextualizing the SFL discourse to adapt it to the teaching environment. To address system network (convention) complexity, scholars have not yet published specific proposals, but some SFL practitioners have tried to cope with this issue in their classes by, for instance, using (simplified) fragments of system networks, not whole networks. One such case is Mick O’Donnell, who uses simple networks as road maps at the end of a topic representing the different kinds of things which learners have covered over the module, as a way for the students to see quickly how the things they have learnt fit together, thus providing them with a mental framework to organize their ideas (O’Donnell, personal communication).[6]

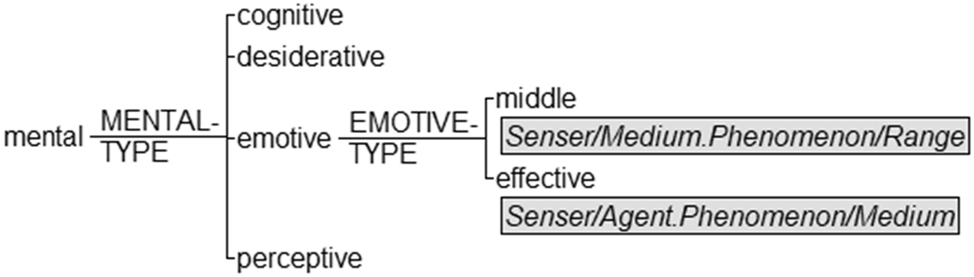

Picking up on the idea of using systems or simple networks rather than complex comprehensive system networks, we can see how a system such as the one for mental transitivity in Figure 6 above could be further simplified to guide students in the process of learning the basic aspects of that area of the lexicogrammar enabling them to carry out the activities detailed in Section 3.4. Figure 11, below, provides an example of one such possible simplified version of a system network of mental transitivity. This network foregrounds the bidirectionality of emotive processes (i.e. like-type vs. please-type, see Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: 258), and may be used, for instance, to ask students to explain the emotive-type system, giving examples of each of the two types in the system. Different versions of this system network could be used to focus on the lexicogrammar of the different mental types, thus providing easy guidance in the learning process.

A simplified system network of mental transitivity foregrounding emotive lexicogrammar.

Reference works such as Matthiessen’s (1995) Lexicogrammatical Cartography can be used by L2 instructors to find plenty of system networks to use either as they are or adapted and simplified in the manner just shown. An easy way to create simplified versions of system networks could be to use O’Donnell’s (2021) UAM Corpus Tool, which provides a user-friendly interface for designing such systems, including their realization statements seen in the boxes under middle and effective in Figure 9 (these could have even been made more self-explanatory by using the labels like-type and please-type, see Table 2 below). For those instructors not really wishing to go into the trouble of creating system networks, an alternative option could be presenting systems in tabular form, something often done in the SFL literature (for instance, in Halliday and Matthiessen 2014 or in Matthiessen 1995). The tabular representation of the system network in Figure 11 is shown in Table 2.

Tabular representation of a simplifies system network of mental transitivity.

| mental type | mental sub-type |

|---|---|

| Cognitive | |

| Desiderative | |

| Emotive | like-type (Senser/Medium; Phenomenon/Range) |

| please-type (Phenomenon/Agent; Senser/Medium) | |

| Intentional |

As a last idea before moving on to the next Section, system networks as learning guiding tools may be used both synchronously and asynchronously. That is, they may be used during face-to-face lessons or as part of a course’s autonomous workload. For instance, once students have become accustomed to working with them, system networks may be used in a blended-learning environment where different areas of the lexicogrammar could be presented systemically for the interpretation of students before the face-to-face session, where they would then apply the newly learnt concepts to a number of tasks designed by the instructor.

3.6 Contrasting L1 and L2 resources based on multilingual system networks

L2 teaching methods from mid-20th century onwards, when the grammar-translation method started its decline, have for the most part discouraged the use of the L1 in the teaching/learning process. It has been generally assumed, and rightfully so, that (excessive) reliance on the L1 as the medium of instruction can create a dependency on translation and thus hinder the development of fluency (Larsen-Freeman and Anderson 2013). This has led L2 methodologists and researchers to advocate the use of L2 as the primary means of communication, so as to foster the ability to think and interact directly in the target language (see Lightbown and Spada 2013).

While it is easy to agree that excessive reliance on the L1 is not the ideal way to learn a L2, since the lexicogrammatical patterns of the former are bound to impinge onto those of the second, it is still possible to see how the contrast of L1 and L2 resources may be beneficial to learners when used as a complement, not as the basis of teaching. System networks may be used to raise awareness in learners of those areas of the lexicogrammar where languages show sharp contrasts as well as, and perhaps most interestingly, those areas where the potential is largely shared but there are some minor differences that, unless heeded, are likely to result in negative language transfer, i.e. “when differences between the two languages structures lead to systematic errors in the learning of the second language and to transfer native language into the second language” (Sam 2013).

The affordances of system-network-based multilingual approaches have been explored in other areas of linguistic research. Bateman et al. (1999), for instance, propose the reuse of linguistic description in the context of automatic multilingual generation. The authors claim that “The effort involved in constructing particular language descriptions is very high, and such reusability offers considerable potential savings” (Bateman et al. 1999: 636). Although automatic language generation and L2 teaching/learning may be regarded as two very distant fields, we do not need to overstretch our imagination to see that the same savings may be achieved if, by comparing system networks of specific areas, learners become aware of all the reusable potential and focus on those aspects that require maximum learning effort. Supporting this multidisciplinary view of the affordances of multilingual approaches, Matthiessen (2018: 108) writes: “The notion of multilingual meaning potential is needed to describe how speakers learn additional languages, how they switch between languages in the exchange of meanings or even mix them, or how they reconstrue meanings as they translate or interpret text”.

Matthiessen (2015) provides the following explanation of multilingual system networks, before moving on to producing some nice examples for English and Chinese as well as for English, Korean and Chinese, reflecting commonalities and specificities in different areas of the lexicogrammar:

The notion of a multilingual meaning potential combines Halliday’s (e.g. 1973) conception of a language as a meaning potential – what a speaker can mean, his or her resources for making meaning – with multilingualism: what a speaker can mean in two or more languages, or, by another step, what members of a multilingual community can mean collectively in two or more languages. Such a multilingual meaning potential can be represented by means of a multilingual system network. In a multilingual system network, the systems of the languages being represented are unified, but they are unified in such a way that the internal integrity of each language is preserved. (Matthiessen 2015: 5)

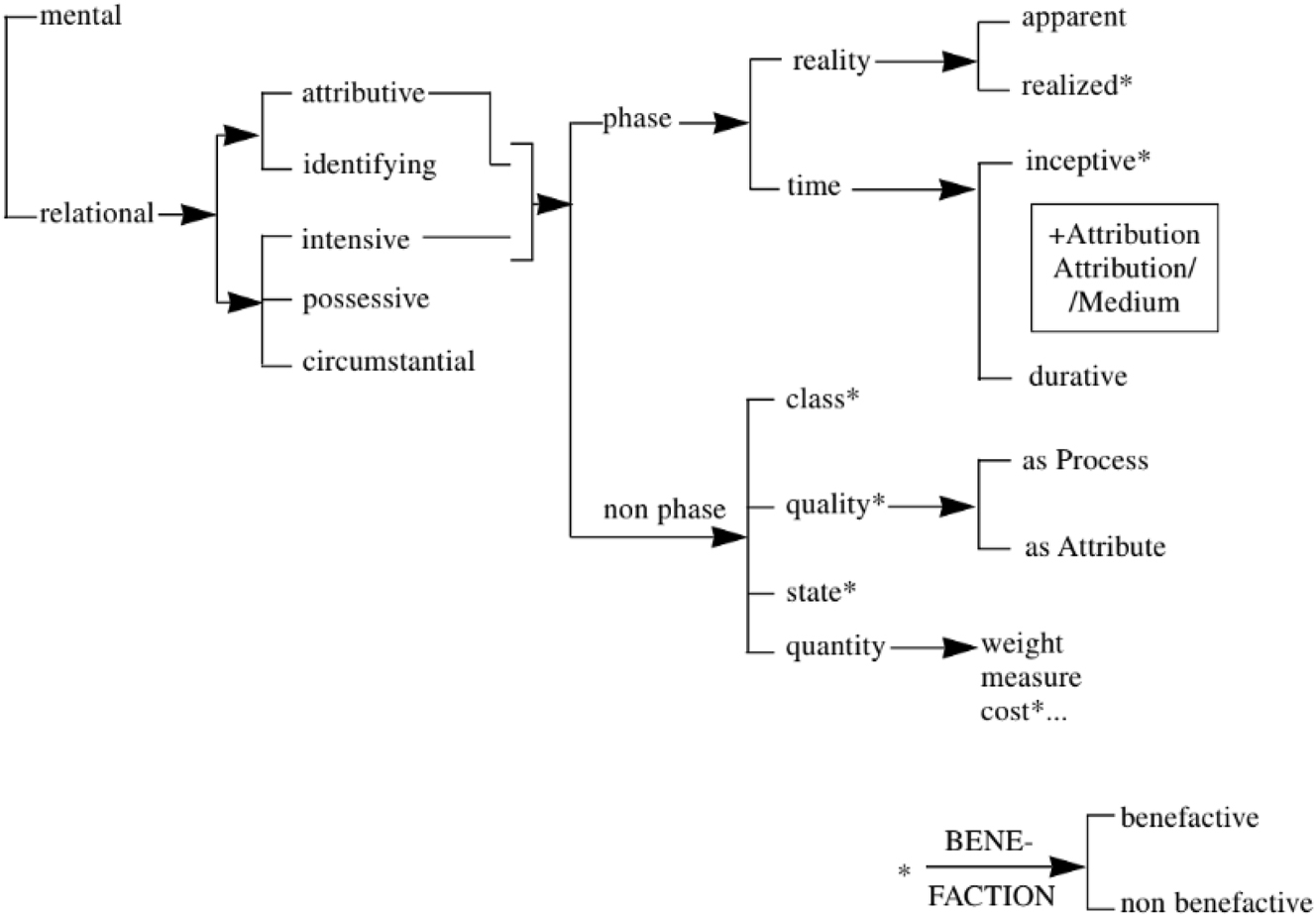

Let us see an example of how multilingual system networks may help raise learners’ awareness of specific L1–L2 contrasts in a way that may be beneficial to their learning. Arús-Hita and Lavid (2001), in a contrastive description of relational transitivity in English and Spanish, provide the general system network in Figure 12, valid for both languages.

![Figure 12:

Relational transitivity network for English and Spanish (Arús-Hita and Lavid 2001: 70).

Readers unfamiliar with SFL will find a detailed explanation in Arús-Hita and Lavid (2001). Let us, however, provide some very basic notes here: intensive processes are non-reversible, e.g. [Carrier/Medium:] Peter [Process:] is [Attribute/Range:] tired, whereas identifying processes are reversible, thus [Token/Identified/Agent:] Peter [Process:] is [Value/Identifier/Medium:] the best player or [Token/Identifier/Medium:] The best player [Process:] is [Value/Identified/Agent:] Peter. Both attributive and identifying process may be intensive (processes of being), possessive (processes of having) or circumstantial (processes of being at, about, etc.). Distinctions such as transitive versus ergative or the addition of a pseudo-effective category are made and justified by Arús-Hita and Lavid (2001) but are not essential for this very sketchy explanation of the system network. For a more detailed account of relational transitivity, see Halliday and Matthiessen (2014: §5.4)](/document/doi/10.1515/jwl-2023-0056/asset/graphic/j_jwl-2023-0056_fig_012.jpg)

Relational transitivity network for English and Spanish (Arús-Hita and Lavid 2001: 70).[7]

While this system network may be argued to be too complex to work with in an L2 teaching context, one could simplify it to adjust it to the needs of learners. Or the instructor may draw their attention to specific paths within the network so as to show relevant aspects. Let us say that the instructor takes his/her learners through the following path (from Arús-Hita and Lavid 2001: 71): (relational: expanding: attributive & intensive & transitive & pseudo-effective), which would explain both English (1) and Spanish (2):

| The grass is green |

| La hierba está verde |

The instructor would of course have to explain the different selections as they navigate across the network – which incidentally may make learners reflect upon all the choices they make while speaking. Now this would raise the inescapable issue of ser versus estar in Spanish, from the perspective of English-speaking learners of that language. And this is where comparing multilingual (bilingual, in this case) system networks can be very informative. Understanding the use of estar in (2), above, is not very complicated if a slightly more delicate system is used, such as the one in Figure 13 (also from Arús-Hita and Lavid 2001: 74), which includes the features ‘class’ and ‘state’ ultimately responsible for the lexical realizations ser and estar, respectively.

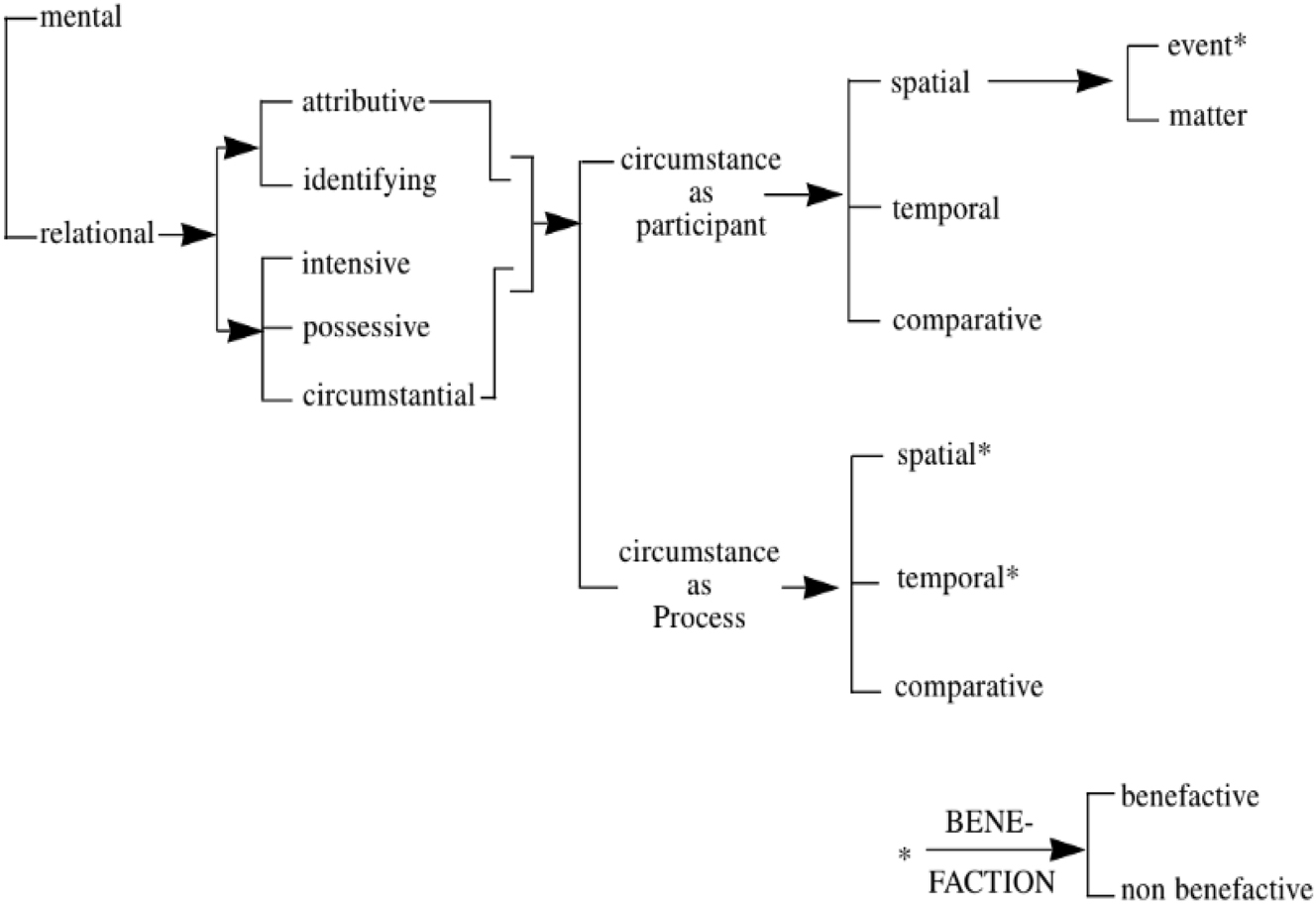

Delicate system network of relational transitivity, with a focus on attributive intensive potential to foreground specificities of Spanish.

What the system in Figure 13 shows is actually quite close to the commonsense explanation typically given for differentiating ser and estar in Spanish, i.e. the former expresses pertaining to a certain class whereas the latter indicates a given state. Not so easy, however, to understand by learners of Spanish as a L2, or to explain by their instructors or textbooks, are the uses of these lexical realizations in the case of attributive circumstantial clauses. While these clauses are typically identified with estar, one of whose uses is typically associated with indicating location, there are realizations such as (3) which can prove a challenge to explain and/or understand, given that they express location but use ser, not estar. System networks can again be of great help here. The one in Figure 14 shows the delicate system network of Spanish attributive circumstantial transitivity, with specification of the options ‘event’ (e.g. a party, a movie, a sports match […]) and ‘matter’ (a house, a person, a cinema, a stadium […]), as part of ‘spatial’. If the former is selected, i.e. if the path (relational: expanding: attrib. & circumst. & transitive & pseudo-effective: circumstance as participant: spatial: event) is followed, the Process is realized as ser, as in (3). If the path chosen is (relational: expanding: attributive & circumstantial & transitive & pseudo-effective: circumstance as participant: spatial: matter), the clause will have estar as a Process (4).

Delicate system network of relational transitivity, with a focus on attributive circumstantial potential foreground specificities of Spanish.

| La fiesta es en casa de Luis (‘The party is at Luis’ place’) |

| ¿Y dónde está la casa de Luis? (‘And where is Luis’ place’) |

It should be noticed that, for the explanation of how multilingual system networks and the more delicate language-specific one can help L2 instruction, no system networks have been created ad hoc. These have rather been recycled, so to speak, from an existing publication (i.e. Arús-Hita and Lavid 2001). This has been done intentionally, to show that L2 instructors do not need to learn how to design system networks (although it might always help). It is often possible to reuse already existing networks in the literature. There are several descriptive works of different languages which can serve as resources for the retrieval of system networks. EFL instructors, for instance, can find plenty of them in Matthiessen (1995), which can be compared with system networks retrievable from descriptions of other languages such as Spanish (Lavid et al. 2010), French (Caffarel-Cayron 2006), or Japanese (Teruya 2007), to mention but a few of the wide array of language descriptions existing in the SFL literature, several of which can be found in Caffarel et al. (2004).

As a last note, it is also worth mentioning the possibility of using multilingual system networks for the identification of cross-linguistic differences whose motivation is found beyond the lexicogrammar. We will not delve into this important topic here, but will simply bring up the example given by Matthiessen (2018: 106) in relation to one of the uses of the English imperative, and the heed that should be paid by English speakers when learning other languages: “Thus, in English, the ‘imperative’ is perfectly fine in the appeal segment of advertisements (realizing an ‘exhortative command’), as in For a free brochure, simply fill in the coupon or phone IBM Direct on 008 622 437, but in Chinese and Japanese, this would be a very marked option or even an impossible one”. In this case, multilingual system networks would have to reflect not only the lexicogrammatical potential but also choices available within a given register (functional variety of the language) within a certain setting of the contextual parameters of field, tenor and mode. A first step would be, as explained above, to find the relevant systems in the existing literature – in this case on English and Chinese or Japanese – for the illustration of choices at both levels and how they co-select, and, if everything not found, create basic system networks reflecting the key features involved in the desired contrast. As said above, this can be done by means of user-friendly software such as O’Donnell’s (2021) UAM Corpus Tool.

3.7 Supporting advanced L2 learners expanding their L2 uses by adding translation skills drawing on multilingual system networks

In the previous subsection, we dealt with the use of system networks for contrastive purposes in L2 instruction, and we will now be looking at something along similar lines yet with a focus on more advanced levels of proficiency.[8] It is at this level that translation may arguably be claimed to no longer pose a threat to effective communication in L2 (compare Section 3.5, above) but, in contrast, actually be of assistance to learners in the comprehension of cross-linguistic nuances and in the mastery of new linguistic skills (see Cook 2010; Korošec 2013; Leonardi 2010, about the benefits of translation as a language learning tool at an advanced level). As befits the topic of this paper, the L2-learning-oriented translation practices here discussed will be based on system networks.

Translation studies have a long tradition in SFL (see Wang and Ma 2021), from early works by Halliday (1962, 1992b), Catford (1965), or Ventola (1995, 1996 to more recent work by Manfredi (2014), Kunz et al. (2014), or Hansen-Schirra et al. (2012), to name but a few. This includes research on the role of system networks in translation. Matthiessen (2014: 317), for instance, looks at the system networks of modality of the source English and the target German in a translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to show the modal choices made in each language to express the same meanings. This allows Matthiessen to claim “that certain selections are retained in the target language […] whereas other selections are shifted”. We can imagine L2 instructors showing intermediate-to-advanced learners translation extracts reflecting lexicogrammatical contrasts known to be problematic even at high levels of proficiency and then providing the system networks involved (in the source and the target language) so learners can see the potential available for each language and the actual choices made in that particular instantiation. The class could then discuss other potential choices that have not been activated but could have, and the implications with respect to other choices. Alternatively, if it is not easy for the instructor to get hold of the system networks needed, ad hoc networks could be collaboratively created based on the textual instances discussed.

As an example, let us take the English clause (5) and its German translation (6), which learners at around B1 may be expected to be able to produce. This pair illustrates the different order of circumstantial elements in English and German, where the former usually has place.time, i.e. [circumstance: place] at the restaurant [circumstance: time] late in the evening, and the latter time.place, i.e. [circumstance: time] spät am Abend [circumstance: place] im Restaurant. The mere comparison of (5) and (6) will no doubt serve to raise the point, and some students may keep this contrast in mind. However, it could be argued that a visual representation of the different potentials of each language may leave a longer-lasting impression in the learners – if only because more time and cognitive effort will be devoted to the issue. The instructor could then draw a very basic network with a system of circumstantial transitivity as well as one for recursivity (see Figure 15) and have the learners go through the paths associated with each of the two realizations. This would require them to first choose ‘place’ for English and ‘time’ for German, then go through the ‘go to’ feature in recursivity, and finally do the reverse selection, i.e. ‘time’ for English and ‘place’ for German. They could also be asked to provide the realization statements corresponding to the selections made, i.e. [circumstance: place]. [circumstance: time] for English and [circumstance: time]. [circumstance: place] for German. The practice would of course be more meaningful if then completed with the use of a more general system network of transitivity with all the choices necessary for the generation of each clause.

![Figure 15:

System network for the practice of the generation of circumstantial transitivity in English and German (drawn with UAM Corpus Tool [O’Donnell 2021]).](/document/doi/10.1515/jwl-2023-0056/asset/graphic/j_jwl-2023-0056_fig_015.jpg)

System network for the practice of the generation of circumstantial transitivity in English and German (drawn with UAM Corpus Tool [O’Donnell 2021]).

| The group arrived at the restaurant late in the evening. |

| Die Gruppe kam spät am Abend im Restaurant an. |

One can only but imagine the endless possibilities of the kind of activity just suggested. Any conflictive cross-linguistic issue may be discussed and systematized in the L2 classroom – including the virtual classroom in blended models. And there are also possible variations to the procedure explained here. Halliday (2013: 149), for instance, suggests looking at wrong – or, at least, questionable – translations to identify the moment in the system network when the arguably infelicitous choice was made – this he calls “pinpointing the choice”. Asking L2 learners to pinpoint the choice(s) motivating questionable translations and suggest alternative choices for more felicitous versions in the target language may provide effective linguistic practice for the development of L2 proficiency. In a way, as we have seen throughout the whole of Section 3, the limits in the use of system networks in L2 teaching are to a large extent set by the imagination of the instructors or methodologists resorting to them.

4 Conclusions

Fundamental to all L2 education informed by SFL is the nature of language as resource (rather than as rule) – a resource for making meaning, or a meaning potential in systemic functional terms. The nature of language as a meaning making resource is brought out most clearly and explicitly when we represent it by means of system networks, showing the options in meaning, wording and sounding that L2 learners have at their disposal as they learn how to mean in the new language, and gradually master its immense resources. Thus system networks enable us to highlight all the different facets and phases of learning how to mean in a new language, and to support the development of pedagogy for L2 education by grounding it in the nature of language itself as a huge network of options in meaning, thus taking into account the unique properties of learning language (as opposed to learning subject or disciplinary knowledge through language).

In light of the above, this paper set out with an agenda to demonstrate the power of system networks in L2 education. To that end, we first presented system networks as they are conceived of within the SFL framework, their value in the representation of language as a meaning potential and a first foray into their role in the study of language learning. Once the main characteristics of system networks had been reviewed and their potential appliability to L2 education had been established, we moved on to show specific areas of application. We thus have seen that system networks may be helpful for tracking language development, diagnosing problems in L2 texts, developing L2 learning materials and curricula, designing exercises, guiding L2 learning in the manner of cartographic tools and contrasting L1 and L2 resources, including the possibility of resorting to translation skills.

The description of all the possible applications of system networks to L2 education represents an arguably important novelty in the fields of SFL and L2 education as well as opening up a wide range of opportunities for future research and implementation. Each of the uses described in this paper is applicable to different areas of the lexicogrammar, whether ideational, or interpersonal, or textual, or combinations of these, not to mention the affordances that the use of system networks representing extra-linguistic potential – e.g. choices available within field, tenor and mode at the level of the context of situation – may bring to contextualized L2 teaching (see, e.g. Derewianka and Jones [2016]; Omaggio [2001], to mention but two among the plurality of references stressing the importance of teaching L2 in context). And all of this extensible to any L2 object of study – and eventually to a myriad of possible L1/L2 combinations: a truly vast repertoire of gaps to be filled.

With the exception of the short introductory illustration showing how phonetic/phonological system networks can be used to help students engage in phonetic yoga as they try to master the sounds of their L2, all examples in the paper have been taken from areas of lexicogrammar, in particular the systems of modality and transitivity. However, system networks within the other strata of language – semantics and phonology (or graphology) – can be used in very similar ways, as can system networks located within the context in which the students’ L2 is “embedded”, as said above. In addition, there is one interesting possible use of semantic system networks that is unique to them since semantics serves as the interface between language and what lies outside language. This has been explored in systemic functional research for particular situation types within contexts: Halliday (e.g. 2003 [1972]) and other systemic functional linguists (e.g. Patten 1988) have described the semantics system networks tailored to particular situation types, e.g. the semantics of maternal control of young children; and they have included explicit lexicogrammatical realization statements, thus showing what areas of lexicogrammar need to be accessed.

Semantic system networks represent specific uses of the overall semantic systems, and they bring out the strategic nature of semantics – the strategies of meaning for solving some specific contextual problem like controlling a young child’s behaviour. Such strategic semantic system networks could be used in L2 education. For example, it would be possible to develop semantic system networks characterising the strategies L2 learners need to accomplish contextually defined tasks such as introducing themselves, evaluating a product such as a movie, complimenting a fellow student, describing their home, citing academic work in a research paper. Such register-specific semantic System networks could also help bridge the gap between contextual approaches, i.e. approaches based on communicative needs, tasks or genres, and the lexicogrammatical resources that they need.

In conclusion, this paper has attempted to build a bridge between the existing literature on system networks, including the limited amount of work relating these to L2 education, and the exciting future that may be brought about by the integration of these networks into L2 teaching practices. We hope that the ideas and examples given in the previous pages have succeeded in demonstrating the synergies that this integration may achieve. Future, ideally near-future, research and/or reports on teaching practices will reveal whether the L2 education community picks up the gauntlet that we are hereby throwing down.

References

Akbari, Omid & Azam Razavi. 2015. Using authentic materials in the foreign language classrooms: Teachers’ perspectives in EFL classes. International Journal of Research Studies in Education 5(2). 105–116. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2015.1189.Suche in Google Scholar

Arús-Hita, Jorge. 2008. Teaching modality in context: A sample lesson. Odense Working Papers in Language and Communication 29. 365–380.Suche in Google Scholar

Arús-Hita, Jorge. 2016. Virtual learning environments on the go: CALL meets MALL. In Antonio Pareja-Lora, Cristina Calle-Martínez & Pilar Rodríguez-Arancón (eds.), New perspectives on teaching and working with languages in the digital era, 1–10. Dublin: Research-Publishing.net. (accessed 6 June 2023).10.14705/rpnet.2016.tislid2014.435Suche in Google Scholar

Arús-Hita, Jorge. 2022. Teaching mental transitivity to EFL learners: A blended-learning proposal. Paper presented at the 47th International Systemic Functional Congress (ISFC 47) as part of a colloquium, System networks as a resource in language education organized by Winfred Xuan & Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen, Shenzhen University, July 25–27.Suche in Google Scholar

Arús-Hita, Jorge. In preparation. Teaching mental transitivity to EFL learners: A blended-learning proposal. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching.Suche in Google Scholar

Arús-Hita, Jorge & Julia Lavid. 2001. The grammar of relational processes in English and Spanish: Implications for machine-aided translation and multilingual generation. Estudios Ingleses de la Universidad Complutense 9. 61–79.Suche in Google Scholar