Abstract

This paper aims to show how concepts and analytical methods of systemic functional linguistics can work congruently with other human practices to improve outcomes for those undergoing the suffering around loss of meaning and the absence of purposeful, self-directed experience. Based on a two-decade collaboration between linguists and psychotherapists in Sydney, Australia, and using the tools of text linguistics as developed by Michael A. K. Halliday and Ruqaiya Hasan in systemic functional theory, the paper presents an indicative selection of intense exchanges between traumatized persons and therapists (centrally the experience of ‘Ruth’). The level by level linguistic descriptions of these exchanges offer opportunities for understanding how progress in the clinical interaction might be achieved. The descriptions can also be evaluated against the theoretical claims of psychotherapy in psychiatry – in particular, the emphasis of the Conversational Model of Psychotherapy developed in England and Australia by Robert Hobson and Russell Meares, whose characterization of disorders involves an emphasis on ‘co-ordination’ and ‘cohesion’ within frontal lobe activity of traumatized patients. In this way the paper also explores conceptual parallels and intellectual antecedents shared between the Conversational Model and Systemic Functional Linguistics, contributing to the broader intellectual history of the human sciences.

“Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone, all just supply, and all relation”. “An Anatomy of the World” by John Donne (1572–1631).

The aim of the therapist is “to find, in the bits and pieces of the other’s experience, as it is selected and recounted, a shape, an analogical resemblance, which gives it coherence” (Meares et al. 2012: 28).

1 Introduction

The aim of this paper is to offer generalizable illustrations of the way concepts and analytical methods of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) have worked congruently with other human practices to improve outcomes for those undergoing the suffering around loss of meanings, and the absence of purposeful, self-directed experience. In other writing, we have been able to illustrate similar practical applications in technical settings – for instance, in genetic counselling; in the clinical trials pertaining to cancer treatments; in surgical teamwork – each of which is a techne (τέχνη, ‘art, skill’) that needs to be developed with mentoring; through insight (θεωρεῖν [theorein], ‘to look at’ → a way of looking); and ‘first-hand’ experience (a concept at the centre of the debate between Socrates and the rhetorician Gorgias: Roochnik [1996]).

Ultimately, we need to ask what Halliday meant by “appliable linguistics” (especially Chs. 2, 7, and 8 in Webster [2013]): how and why might linguistic analysis be efficacious in an increasingly complex world, a world of proliferating and contested subjectivities? The terms that Halliday invokes are conventional to functional and even traditional theories of language. Still, in the context of SFL theory, some terms take on an instrumental value and relational definition which means there is a shift in their place in a language theory (a shift in their “address” within a theory). This follows from the need for the terms to work in the descriptions of languages quite different from Greek, Sanskrit, or Latin. Still, the different levels or strata of the system are easily construed by linguists and terms like transitivity and mood, theme/rheme, or modality serve as useful ways of setting off into a paradigmatic network of the semantic consequences of speaker options: namely, the alternatives to meaning through the lexis and grammar. The paradigmatic options of Halliday’s version of networks productively align with what Bateson (1979) emphasizes as “news of difference” in evolution (see also Halliday 2003 [1995]), and are also in concord with Saussure’s emphasis on reciprocally defining relations or “valeurs” (1959 [1916]) (see Section 4 below).

In psychotherapeutic care, linguistics can contribute to the therapist’s work of establishing, with the patient, a coherence or balance in the well-being of a human core, our need to value and be valued in the flow of experience. The therapist addresses trauma (here in relation to the extreme cases classified under Borderline Personality Disorder) amid the process character of the “stream of consciousness” (James 1890: Ch. IX). Interaction is itself one more current in the “flow of things” emphasised from Heraclitus (Chargaff 1978) to Alfred N. Whitehead (1978 [1928]) and Waddington (1977), see also Butt (2008). Coherence is a term widely applied to existential value in relation to the human psyche. It is a term shared by many disciplines of enquiry, from psychiatry to physics (paradoxically in ‘decoherence’, Whitaker [2006: 300–315]). In literary analysis, the term may be applied both to thematic content and plot, and also to the way a text is built in its wording). Coherence is the antonym, the antithesis, of chaos or disorder. Physicists tell us that we live in a realm of entropy – lives develop but on the way to general dissolution. So “things fall apart […] the centre will not hold”, as the poet, W. B. Yeats, apprehended in signs of the imminent storms of fascist Europe in his “The Second Coming”. It is a cry of those living through an era in which beliefs lose their unifying status – as evident for Shakespeare’s contemporary, John Donne, in his declaration in his “An Anatomy of the World”: “Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone, all just supply, and all relation”. Or 300 years later, when T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound use a patch work of European linguistic and religious vignettes, a collage structure, to represent a new technological era of human alienation and disenchantment in “The Wasteland”. It may be a motif of every era – our “rage for order” especially in the post-Nietzschean context of change and with the sense that the ‘roof of history has been torn away’ (viz. as Dr. Zhivago opines to Lara in Boris Pasternak’s celebrated novel).

Metaphors and motifs of fragmentation were a feature of symbolic representation in the period when psychiatry and psychoanalysis were taking form through the works of Janet and Freud, along with the psychological program enunciated in the works of William James in his later career (1884–1910); see James (1890, 1892, 1904. We can study the self-portraiture of contemporary painters like Francis Bacon (1909–1992) and Brett Whiteley (1939–1992). But they were preceded by the many tortured self-portraits of Egon Schiele and the philosophies of Existentialism (e.g. of Heidegger and Sartre: Kaufmann [1975]), all of which foregrounded intense examination of being, or of becoming and self-identity.

What is less evident and under-appreciated is that, from the 19th century, Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911) in England began to theorize disorders of the mind as conditions of a failure of the “self”, that is, as illnesses that demanded a medical context. Jackson influenced researchers in France – Ribot (1839–1916), Charcot (1825–1893), and Janet (1859–1947). Jackson’s characterization of the disorders involved a novel vision of organic problems of the self not in terms of a locus of disease, but in terms of a relational brain, in particular in terms of dysregulation of what needs to be a ‘co-ordination’ and ‘cohesion’ within frontal lobe activity of traumatized patients (Meares 1999). Jackson captured his own theory with “le moi est une co-ordination”.

The polysemy of the terms coherence and cohesion is important in this article as it is an entry to the congruence between the techniques of SFL and the Conversational Model (CM) of psychotherapy in psychiatry as developed by Robert Hobson and Russell Meares at the Maudsley Hospital in London, and developed by Meares at Westmead Hospital in Western Sydney. For two decades, and in funded research (National Health and Medical Research Council award to Butt, Moore, and Meares for research based at the Centre for Language in Social Life at Macquarie), functional linguists contributed to an ongoing enquiry into Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) – an extreme and persistent form of personality disorder (see Meares [2012] for a report on his whole career of thinking about BPD; Meares et al. [2012] for reports from a team of collaborators in this work; see Butt et al. [2007, 2012, 2014, 2015]; Butt and Khoo [2014, 2015]; Henderson-Brooks [2006, 2008, 2010]; Khoo [2013, 2015a, 2015b, 2016, 2017]; Khoo and Butt [2014] for accounts from the linguistic point of view).

With his vision of language at the centre of a healing practice, Meares developed his own linguistic model (Meares 2004, 2005; Meares et al. 2005). At the level of text or genre, he distinguished three passages of discourse – chronicles: the often desultory recounting of daily events from which some element may become topical as a ‘thread’; the script – the often recursive account of the constrictions of living that cannot be penetrated by the patient (perhaps resonant with the poet William Blake’s reference to “mind forg’d manacles”); and narrative – the flashes of valued memories, the sparkle of a time when the patient could really feel inclined to the moment and the possibilities of a future. The Jacksonian view was evolutionary in its claims – the loss of cohesion in a patient would lead to the loss of the most recently evolved functional co-ordinations of brain development. Jackson and later Janet argued for a hierarchy of evolved brain states which could undergo loss of organization in psychoses and in other afflictions manifested in body and mind (see Meares 1999; Meares and Barral 2019: Chs. 8 and 9).

The core self then was a co-ordination of activity which produced “coherence” of relations across brain states – a conception in surprising concord with dominant themes in contemporary neuroscience: for instance, theories which appear more emphatic of the role of global states, with dynamic patterns of activation and inhibition, much like a rolling plebiscite of neurons or neuronal electorates. Some extended neurons may have a predominantly “broadcasting” function, reconciling top-down and bottom-up claims or weightings for responses. This idiom in discussing neuronal activity is also in concord with the theory of “global neuronal workspace” by Baars and most recently elaborated by Dehaene (2014: Chs. 4 and 5). The global, relational emphasis also appears to align with (i) the internally oriented “re-entrant neurons” and dynamic core theory of Edelman (1992, 2006; (ii) the emphasis of Damasio on the role of consciousness as mapping and monitoring of values to maintain homeostasis (with such values derived from culture, not just organic imperatives (Damasio 2012: 49, 2018); and the Feldman Barrett (2017) view of the origins of emotions, namely, through contexts that we each carry as our experiential history in language and culture. Influential in the theory of mammalian social relations and human relatedness is also the theory of Porges concerning the vagus nerve – the polyvagal theory. Porges argues for an empathic effect (vagal tone) derived from two levels of vagal nerve: the lower unmyelinated and the upper, cranial, myelinated system which is a basis for our affective feeling for others (Porges 2011). The research of Solms (2021) on the 3 regions of the brain stem extends the work of Panksepp on animal and biological systems and Panksepp’s proposal of 7 fundamental feeling states of humans, the first being the motivator of “seeking” (Panksepp and Biven 2012). From what many regard as the other pole of psychiatry, Solms also emphasizes how Freud’s theories captured many important issues in a nascent version. Among a number of SFL contributors, Thibault (2004) offers an integration of the brain and mind in the signifying body. Naturally, all work has also to be seen against a background of evolutionary thinking on the development of human transactions with experience; for this we cite Feinberg and Mallatt (2016) but see also Halliday (2003 [1995], 2003).

Coherence in psychotherapy is a mercurial concept which includes the implicate order of consciousness over and beyond the linguistic wording which provides evidence of just how a text ‘hangs together’. Nevertheless, both psychotherapy and linguistics can contribute to the evaluation of discourse and the many modes of human expression (including those implicit, or bodily, or indexical after the theory of C. S. Peirce [1958]). We may find further into our discussion that knowledge of linguistic techniques, especially of cohesion/coherence, confirms and refines the pursuit of coherence in therapeutic practice, even offering a useful form of measurement (as in Hasan’s [1984] notion of cohesive harmony; Khoo [2013, 2015a] and various listed presentations which characterize the quantum and variety of modes of the collaboration behind the research).

Coherence in psychotherapy may also open up for linguists a more adequate account of the inter-subjectivity that is so central to stability and to variation in theories of language. There is in these different uses of cohesion and coherence a deep association, a coherence of process which directs us to the less discussed ideas of the linguistics of B. L. Whorf (configurational rapport: 1956: 71–82) and of Halliday’s teacher, J. R. Firth (mutual expectation, prehension; colligation – Firth 1957a; Mitchell 1957). For instance, there is the power of the unconsciously experienced “expectational field” of psychotherapeutic contexts (Meares 2005: 114, 2012: 307, supported by experimental evidence viz. Williams [2005], cited in Meares [2005: 116–119]). Experiments demonstrate how subtle and controlling the unconscious alignments in a relationship can be, especially around trauma. Then there is the potential of noticing and interpreting ‘marked’ choices of meaning through examining alternatives in the grammar. A marked choice in language can be a spike of interest for the therapist, providing an opportunity to investigate what motivated the contrastive (marked) value when sorting the “pieces” of autobiographical memory (Butt et al. 2012, 2014).

2 The therapeutic interaction: from the dynamism of agonists to integrated effort

The examples cited in this paper illustrate a role for functional linguistics in the interpretations made by clinicians, and in describing the semiotic strategies that the experienced therapist creates with those undergoing suffering. The predecessors to the efforts reported here need to be indicated and taken up by readers keen to elaborate this domain of research. The work of Fine (2006: 127) presents an overview of the linguistic knowledge that can be put to work in psychiatry in particular how it offers “shape” to both sides of the clinical dyad. Fine’s work from 1995 qualifies the ways in which cohesion in linguistics needs to be placed in its own theoretical context in order to be appropriately applied in the psychiatric contexts. In an earlier study, Rochester and Martin (1979) drew attention to the relevance of cohesion analysis to work in schizophrenia. The focus in this paper, however, is on psychotherapy and trauma related conditions in patients.

We could begin at the social context – a patient entering a room for private exchanges. Previously we have used paradigmatic networks to demonstrate the parameters of field, tenor, and mode that bring out the relational differences that are semiotically formative (Butt 2003, following the leading ideas of Hasan over decades). An example which addresses one only dimension of the tenor of interpersonal relations – namely the social distance between senior neurosurgeons working in Ukraine (see Butt et al. 2021) – demonstrates how complex and consequential contextual variables can be, even when we expect similarities. We cannot reproduce even a fraction of those networks (Butt 2003) here. The emphasis following is on the agonistic, but ultimately mutual efforts which characterize the therapeutic sessions in addressing trauma and related illness. For a clear case study of how the context and relationship are significant, see Haliburn (2009); to consider a thread of related research, see the work of Emmott and Alexander (2015), and in their references.

A context becomes semiotically charged when we consider: (i) the crucial parameters of privacy; (ii) the expectation of process sharing (both have rights and pressures to speak); (iii) the distinct roles set by professional guidelines, if not by societal laws; (iv) the transactions at a number of levels (including money); and (v) the assumptions about care and measures of progress. The social context also carries the weight of personal history: specifically here, the topic that the interlude between sessions might be Ruth’s last (due to previous suicidal ideation). There is the tension of “Will she or won’t she be here?”. As Russell Meares emphasizes, the intonation in the following simple initial exchange resonates, even couples with, a warmth of positivity that realizes a fellow feeling, a recognition of something that has already been achieved. The therapist has already offered back to the patient an instance of the “reciprocal shaping” (Meares 2012: 307) that will be the work of the ensuing session, albeit later in an elaborated form of “analogical relatedness” (see Table 1):

The opening exchange between Ruth and her therapist.

| T: | Come on through Ruth |

| P: | Here I am (rising intonation) |

| T: | Here you are (rising intonation) |

-

Note: “T” denotes “therapist”; “P” denotes “patient”; bold denotes tonic prominence (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014).

The prosodic pattern of the first exchange exemplifies in its detail the importance of “minute particulars” as urged by psychiatrist Robert Hobson in “Forms of Feeling” (1985), the co-founder with Meares of the Conversational Model. It is also notable that the “Here I am” carries that history of previous and current struggles with survival that give Ruth’s attendance an impact which can be gauged by an ebullience (laughter) that is communicated by the deep meaning of “I am/ You are”. The verb BE always conveys an existential dimension (see Kahn [2003] on Classical Greek forms and Kappagoda [2004]). The existential foundation is often overlooked due to the polysemy of simultaneous functions (see later sections on the lexicogrammar of identifying clauses). There is also a reprise of the significance of ‘being there’ in the feeling and laughter at the close of the session: P: “Thank you” Th: “See you next time” [shared laughter].

Meares (2005: 20) emphasizes that

These small movements may be indicated by the appearance in the conversation of, for example, discrepancies, strange intrusions, unexpected memories and apparent condensations, perhaps expressed as a metaphor or an unusual word. It is hard to describe exactly what has happened at these points, just as it is difficult to depict in the language of prose the experience of a poem. In simple terms, however, we might say non-linearity is breaking into the linear speech of social discourse. (Meares 2005: 20)

Readers of Russian literary theories (viz. of Jakobson [1973, 1978, 1987]; Tynjanov [1978] and in Steiner [1984]; Shklovsky in O’Toole and Shukman [1977], and in O’Toole [2001]) will see in Meares’s quotation an overlap in relation to strangeness and marked and unconscious, but “motivated” selections (Butt and Lukin 2009).

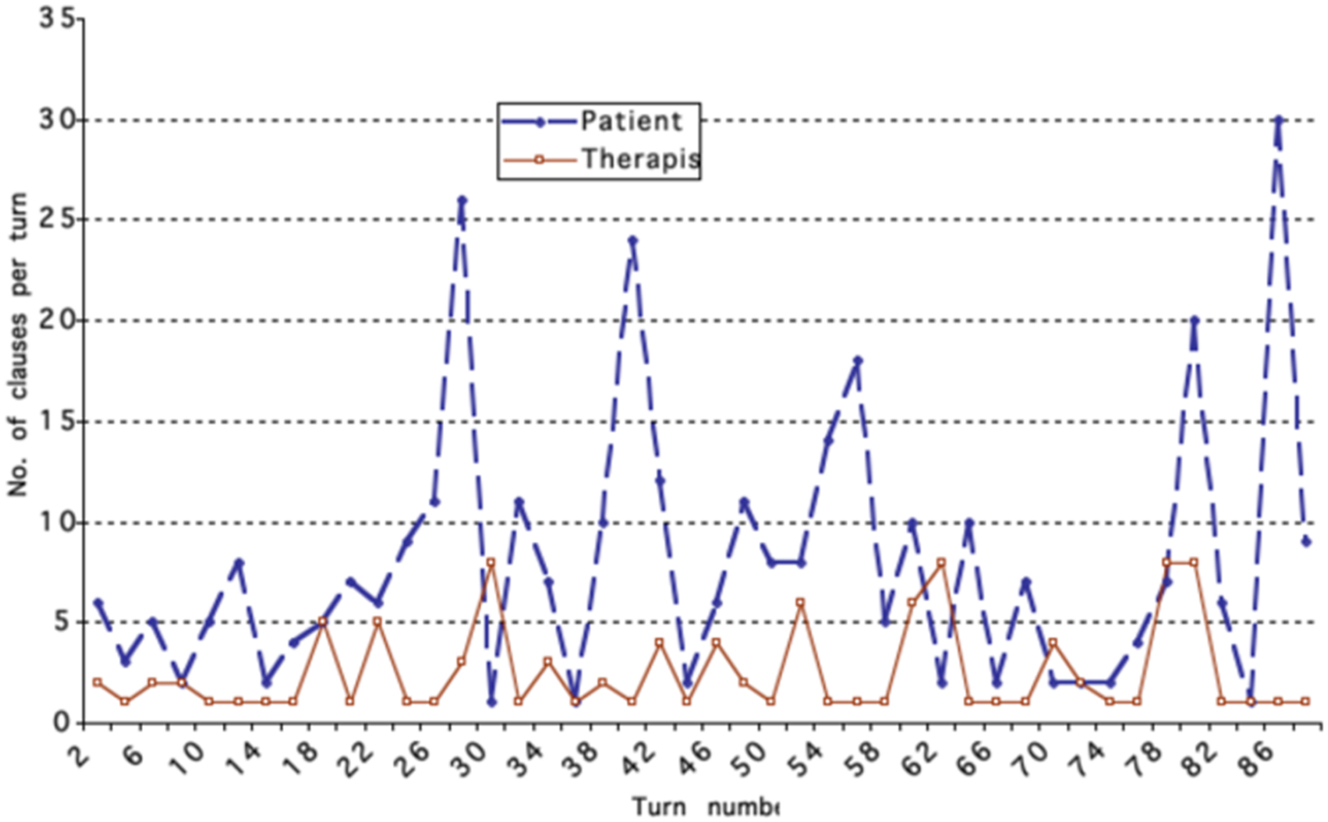

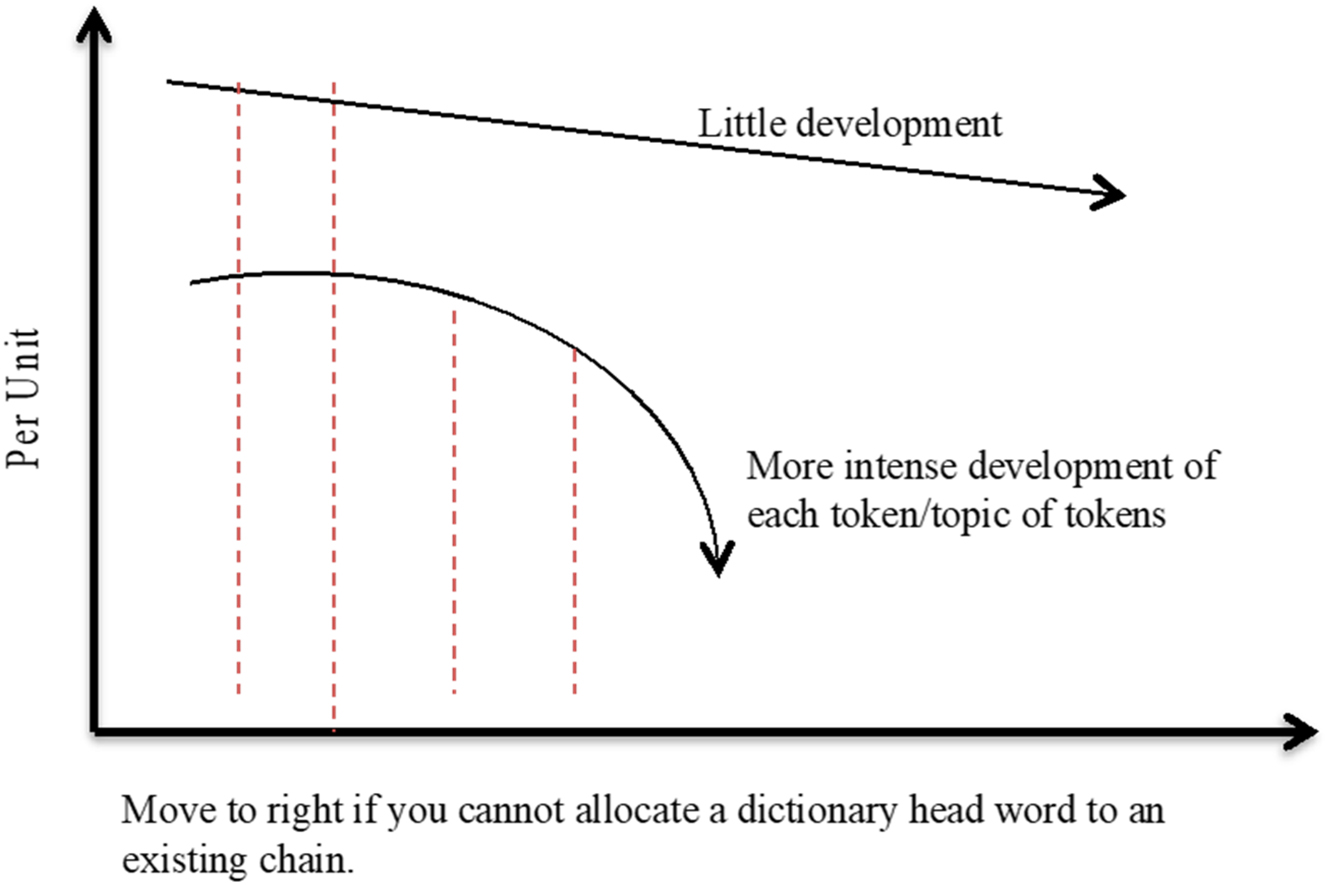

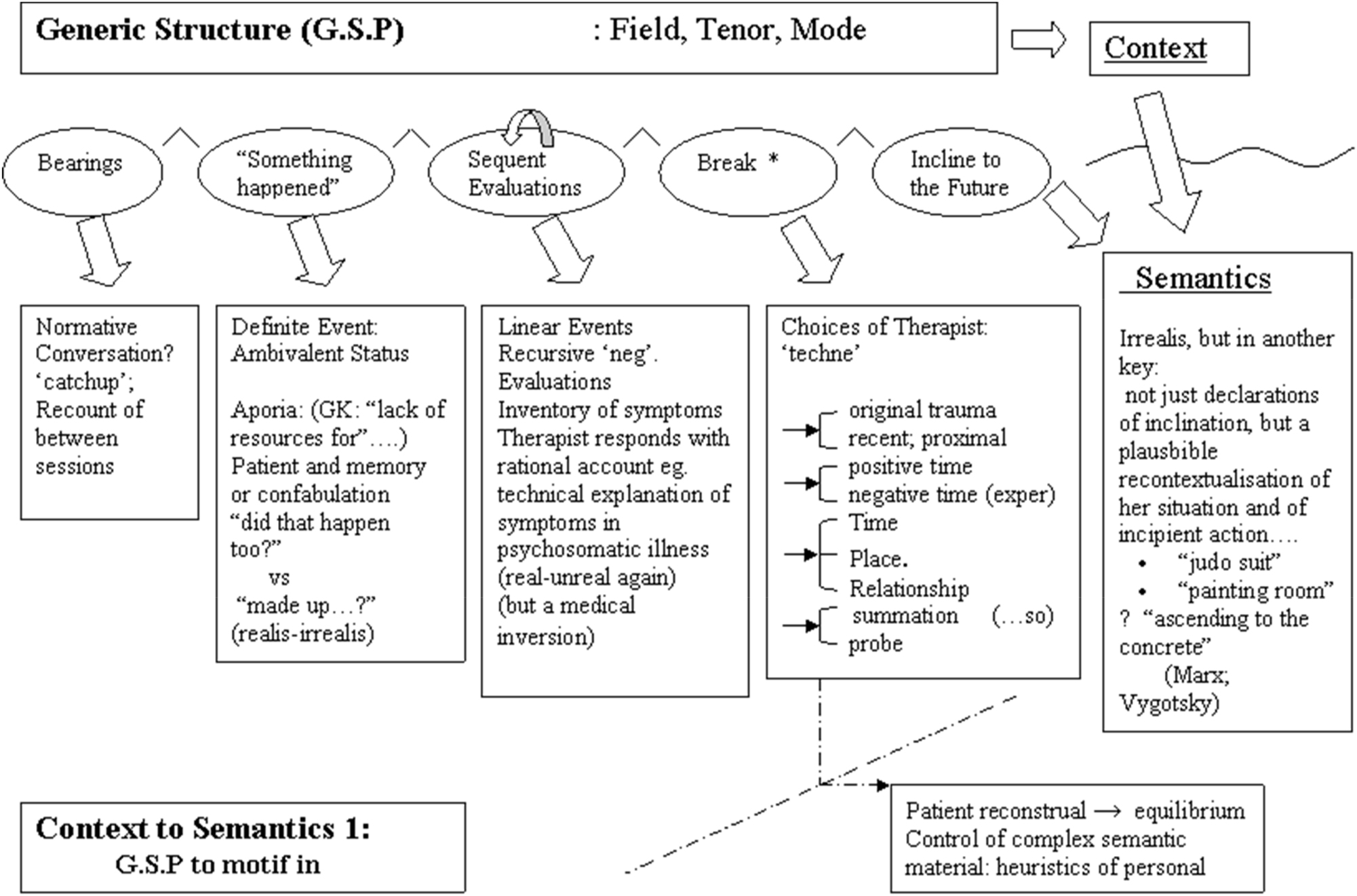

In the case under discussion, the linguistic approach seeks an empirical basis for evaluating the expressive bond between the two women which, we can see in the session, is tested; strained; re-negotiated; and then ultimately brought into a new order of complementarity, of intricacy, of intimacy, through just 55 minutes of inter-subjectivity. In Figure 1 below we can first consider a more typical pattern of conversational development in therapy, namely one that begins in minor checks of medication or recent events and then ‘finds’ a thread to follow. In Figure 2, Ruth’s tirade comes like a storm into the session.

Number of clauses per turn over consultation time: a typical cumulative pattern (see contrast with Figure 2 and the Ruth to therapist).

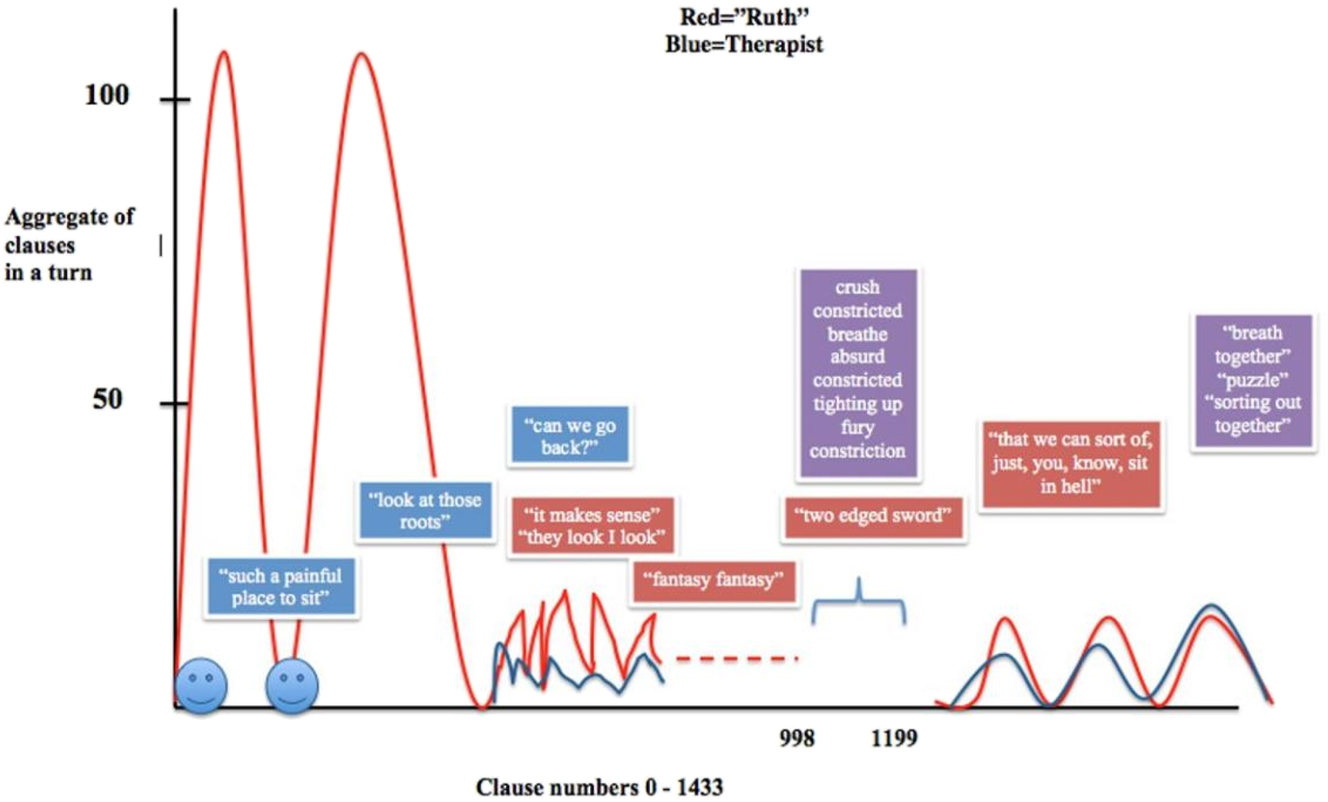

Shifts in topical and interpersonal resonance over consultation time between Ruth and her therapist (figurative diagram).

A tracking of turn taking can be a necessary setting off point for interpreting how the patient takes up the opportunity to divulge and elaborate upon her feelings. The generic shape of a session can be gleaned by a “y” axis which represents the number of turns or clauses of different speakers (Patient to Therapist); and an “x” axis that represents time. Procedural openings and appointment settings can signal their own interpretive values, or sometimes work as resonators of the motifs and themes that are latent in the discourse overall.

Figure 2 is only a “figurative”, global “picturing” of the 1433 clauses/turns/text ‘pieces’ expressed in the 55 minutes session. They are set out against a “y” axis of the approximate number of clauses uttered in turns by patient and by therapist, and can be coded by colour or lines. The “x” axis represents progress (order) in temporal sequence but not in absolute minutes. The “picture that emerges” has three or four phases. These can be regarded as generic elements, much like the linguist would map through a combination of evidence about turn taking (Figure 1), and markers of generic or text structure. There is also congruence with the narratologist’s arc of a stasis disturbed and then restored. When equilibrium is restored, there is a new wisdom as well (see reference to the “roller coaster” passage below). In the figurative diagram, what is notable are the dramatic shifts between an initial oppositional pattern – a tirade from the patient (tirade: in Latin drama, the word for a long declamatory speech) – and a final extraordinary co-ordination of purpose in addressing a “puzzle” that both persons share as the heuristic device. To the latter, they orient “side by side” in an allied cause, a shared challenge to resolve a problem (as if there were a shape extracted from “process” onto the work bench).

Between these two phases there is a bridge of metaphors (what the therapist characterizes as “a narrow ledge”) which brings the patient and therapist into an alignment of affect, and then of interpretation. This bridging could be regarded as forming two stages – one in which the metaphors of suffering are proffered from both sides, first from the therapist, and then the patient (the evidence for this priority is set out below in relation to the level of semantics/rhetoric). The alignment is secured by a moment of significant reconstrual of the suffering: the potent, potentially devastating topic of “beauty” is re-semanticized away from issues of hair and weight (albeit 1 kg over a year) to the patient’s capacity to “tolerate” the suffering: beauty is revealed in a novel, strange but plausible formulation. It has become a moment of meaning discovered – of kairos (kαιρος, ‘a time when conditions are right for the accomplishment of a crucial action’: Merriam Webster [2024]) (see Table 2).

Developing the motif of ‘toleration’ in Ruth’s session with her therapist.

| P: | So she (the last therapist) knew That I would just tolerate and tolerate and tolerate. |

| T: | So there’s something beautiful and agonizing about that. |

| P: | Mm. |

| T: | Isn’t there? |

| P: | That I have to live that way. I … just have to tolerate my life. |

| T: | That that you have to keep living that way. … (11 seconds pause) How breathtakingly painful. |

| P: | Mm. |

| T: | … (12 seconds and then tissues pulled from box) … (13 seconds pause) Th: The tolerating itself is … But how you survive. Yet it’s so tight in its constriction. |

| P | Mm |

| T: | It’s a narrow ledge. |

| P: | Yeah [soft] … (14 seconds pause) |

| T: | There’s a great shame in [[in seeing someone (who) like that]]. |

| P: | Tolerating. |

| T: | It’s as though [[that’s [[what you’re good at]] ]] |

| P: | Yes … I am [[good at tolerating]] … (36 seconds pause) |

The critical motifs provoked by the patient’s repetitions of “tolerate” include the convergence of opposites or marked collocations and previous metaphors of constriction all of which are reworked in the reconstrual by the therapist: beautiful and agonizing; breathtakingly painful; tolerate → living; survive → narrow ledge; great shame → [[what you’re good at]].

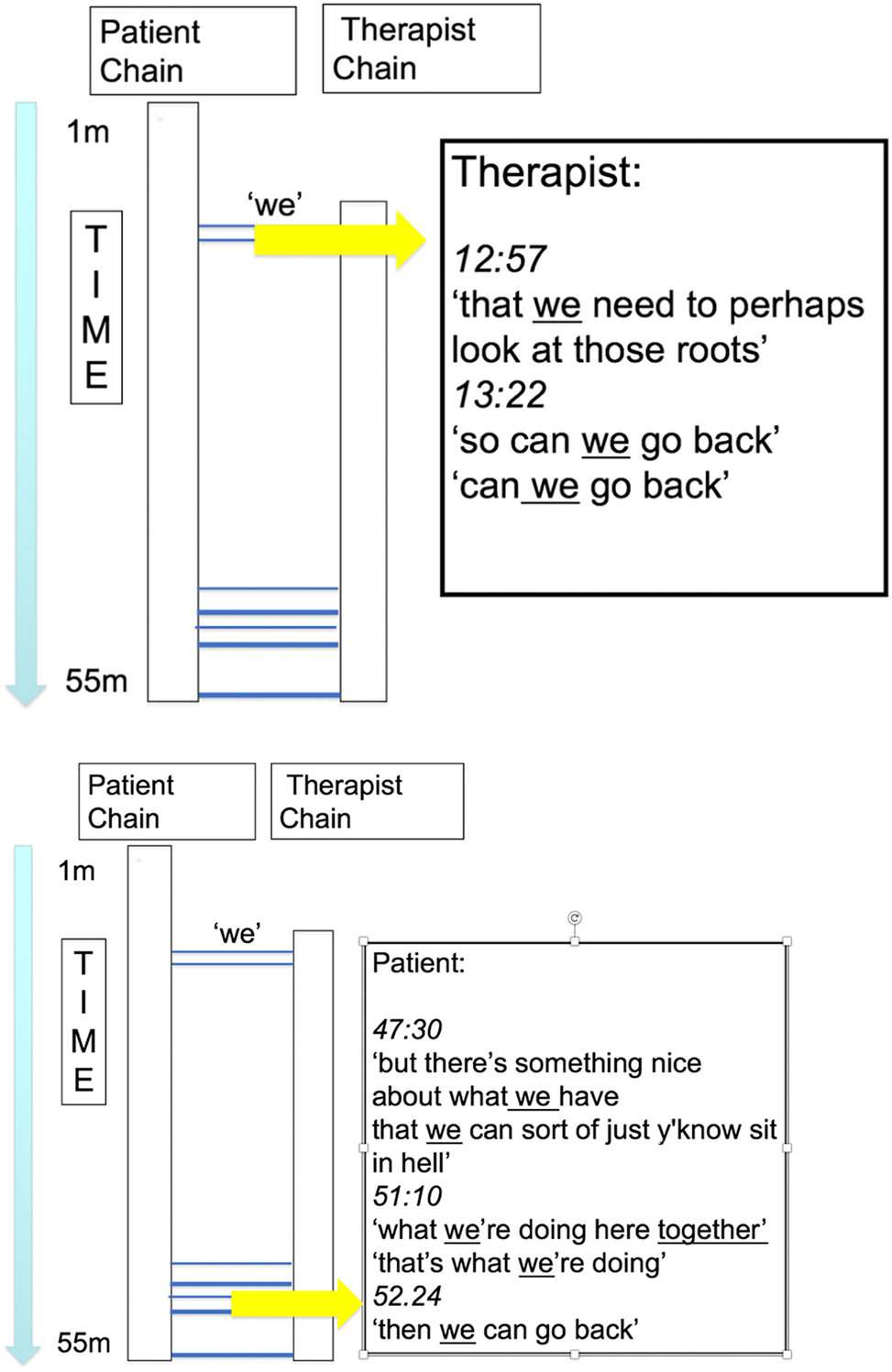

This discourse becomes an ensemble (a reassembling) of the patient’s sadness into 2 forms of positive achievement: beauty (agony/ecstasy) and personal strength (tolerating/endurance). For, an important aspect that differentiates the CM from other forms of therapy is the focus on the value available in the pieces offered to the therapist in the immediate ‘now’. An aim is to capture the flashes of personal narrative that are catalytic of positive feeling, of hedonic tone. This involves isolating what has provoked the immediate state of mind that brought the patient into the session. When the therapist suggests that they “look back” (at 12 minutes 47 seconds), it turns out not to be a question of life history (ontogenesis), but one to establish the local, recent cause of the urgent flow that brought Ruth to this appointment (see Figure 3). This suggests a contrast with the analytical, potentially inquisitorial, effects of the root probing of certain therapeutic theories in psychoanalysis (see Meares and Hobson [1977] on the “persecutory therapist”).

Introducing and returning to plural first person, Ruth and her therapist.

3 Semantic and rhetorical patterning: metaphor in medias res, or “What to say next?”

The preceding extract exemplifies decision making in ‘stormy weather’: how to respond when in the middle of the affective turmoil of a session: will an utterance ameliorate or inflame the difficulties? will the absence of a rejoinder make the patient seem more isolated? In the session with Ruth, the therapist is only able to punctuate the first 125 clauses of declared suffering with the single word “Raw”. In the second “squall” of over 100 clauses, a number of enquiries and supporting statements are worked into the waves of chronicle and script recounted by Ruth. This is to say that by recounting the events of recent days – its messages with her male friends. With Ruth’s actions of escape to restaurants and the harbour; and the meeting with acquaintances who thrive on schadenfreude (“smug satisfaction”: clause 639), that is seeing Ruth’s family in strife – there is a mixing of the diary of events (chronicle) with the cyclic self-misperception that keeps Ruth in its thrall (script). In seeking clarifications, and in coupling with the affectual outburst, the therapist gradually achieves rights to navigate the discourse away from the waves of ‘high-dudgeon’ over to a forensic checking of details. Ruth has presented the account of her sobbing alone in a high dining restaurant; at another point of loss, she highlights the strengths of a male whom she has lost to his overseas work: he is associated with the strength of a harbour bridge. This may be a motif that the therapist revisits in the metaphors of crossing and “a narrow ledge” at the point of a volte face in the session i.e. when the pain and strength undergo reinterpretation.

If we change the metaphor from waves to weave, we can say that by reiteration for the purpose of seeking a more complete cloth (account), the therapist gradually is ceded the selection of threads in the weave. But she selects from what has been on offer: the motifs of sitting alone; of comforting toast; of being spunky of a tickle of fun; a prize; the persistence which becomes being “good at it” or the “keeping on going back there” referring to the more abstract “repeating the same behaviours”; of the crushing, constriction of her authentic being; and of a vice pertaining to crush. The therapist achieves a response of absolute agreement from Ruth, and “yeah it makes sense” (clauses 340 and 357) when she argues Ruth round to examining the incident of acquaintances gloating over her disarray […] the way Ruth is “seen”. Ruth agrees: “really that I’m a void” (clause 370). The therapist arrives at the crucial strand (see Table 3).

Therapist’s arrival at a crucial strand of meaning in conversation with Ruth.

| T: | “So it’s it’s kind of [[ they hold the knowledge of the madness of your mother, of you]]. |

| P: | Yes … me My family. The house. … The way [[they look]]. The way [[they look]]. |

Then, in continuation of a forensic separation of strands of the first 225 clauses (divisions in the reasoning), Ruth’s consciousness of the role of beauty becomes quasi-syllogistic, or even a form of abduction (in which a case permits a leap to a generalization or rule) albeit based on emotion rather than the divisions of logic (see Table 4).

Example of quasi syllogism patient discourse (Ruth).

| P: | And this is my shield. This is my guard. If I let this go It’s unimaginable. … So that so I guess that’s [[what I was thinking Friday]]. |

The therapist has separated out the centre of distress from the contextual epicycles of: e.g. males who do not reply to messages; the restaurant; feeling fat over 1 kilo of weight gain; and even the need to “keep the fantasy going” (clauses 484 and 495) with a male supporter. In a summative subsection, the therapist even adopts Ruth’s voice “Yeah, will somebody please tell me!” (i.e. that “this is OK”) – an early instance of one finishing the wording of the other as the therapist begins to enact Ruth’s voice. In all these motifs and tonal couplings of voice, we may see the incipient intersubjectivity of the final segment of the session, that is when the two sit and complete messages that they then hold as a unified effort against the presence of a now delineated puzzle, an emotional conundrum that they have narrowed down by exchanging motifs. The therapist has proceeded by steps of interpersonal reasoning, trying out her ‘hypotheses’ of emotional value from the first single word: “Raw” (clause 115). Crucial in the texture of meanings that carries Ruth from devastation over to an enlivened inclination to the future (at least for this session), is the motif of the toleration, or endurance, of pain mentioned in relation to a previous male friend (clauses 509–514; incorporating the dynamic image of a bridge and the therapist’s later use of being on “a narrow ledge”).

Approaching the half way stages of interaction (c. clause 700) and on to the reconstrual of “beauty” (clauses 988 and ff.) as “what you’re good at” – namely enduring the pain – the therapist contributes more and more by what we might call: rationales, persuasion by reasoning, but by moves which are linear, but not syllogistic, but akin to a run of hypothetical suggestions which, first of all, ensure Ruth has seen her situation represented back to her – that there is what Meares (2005) and Korner (2021: 33–37) emphasise as “analogical fit”. Ruth has to be convinced of an interpersonal authenticity about the therapy as process, and that the flashes of hypothesis building make sense (to which she expresses assent: “That makes sense […] absolutely”). But crucially, through therapeutic insight (from integrating the verbal seeds of Ruth’s reported suffering), Ruth encounters an unexpected revaluation, a “de-familiarization”: namely, the paradox that there’s beauty in the tolerating.

When Ruth first proffers the ideas of persistence (clause 261), repeating the same behaviours (clause 293), doing the same things over and over (clause 305), and the Einstein quote (that [[repeating the same behaviours over and over again || ‘n expecting a different result]] is the very definition of madness clause 309), a number of deep dimensions of the whole meaningful exchange are on display. These include Ruth’s articulation of “I’m so good at it” (i.e. being foolish about males clause 310) provides the kernel of the therapist’s inversion of the notion of tolerating applied to the solitary endurance of living. This kernel has been amid the scattering of seed over more than 700 clauses or numbered clause complexes. The beauty of her tribulation becomes a “knight’s move”: the therapist is drawing on potential ‘in play’, but full of the counter expectancy of opportunity not envisaged by either persons, but ‘co-created’ (clause 1026: Th: It’s as though [[that’s [[what you’re good at.]]). The therapist had already (in clause 1011) drawn on a cultural collocation (the ‘agony and the ecstasy’ – clauses 1011–1015). This leads on to that union of expressions that are not typically associated, hence rhetorically like oxymorons: “[…] breathtakingly painful” (clause 1016).

Ruth’s characterization of the various reasons for which she is suddenly in disarray is an interesting choice of terms (clauses 709–711, see Table 5):

Example of how patients characterise their reasons for disarray (‘Ruth’).

| P: | Have you ever heard anything. It’s it’s almost absurd. It’s just absurd. |

The literary critic, R. P. Blackmur (1904–1965) captured this idea of unique semantic destination through the metaphor of “surds of feeling” (Blackmur 1932). A surd in mathematics cannot be resolved or reduced to another version. As an Arabic notion, it also captured the meaning of “voiceless” (phonetically). Managing a “surd of feeling” can be a helpful metaphor in numerous contexts, in particular when the value of the total human response is not likely to be retained in atomisms or reduced versions that interrupt the flow. It is as if, in the storm of feeling, a deep oratorical candor renders the utterances with illuminating precision and hence, with power.

Ruth’s complex embedded clause structures typically identify herself and/or define the plausible reasons which account for her trauma in the ‘here and now’ of this session (viz. clause 620 on dis-inclination to the future, and 661–664 on a dramatic triplet of definitions of the fear she lives with). Around this stage in 1433 messages, there is the clear division of discourse into the two themes that the therapist will later integrate or reconstrue: that of pain, and of beauty/ugliness (an imagined future without the “shield” of beauty). These will be treated for their structural or their grammatical meaning in the specific subsection below. It has been the aim here, however, to show how the formulations between patient and therapist exemplify the dramatic rhetorical patterns that have been the concern of world cultures since the writing down of oratorical traditions in religious myth and belief, in law, and in medicine. Semantics is among the earliest of sciences of human classifications or cladistics. Greek or Roman terms were the staple of learning in Europe up to their critique around the career of Charles Dickens (viz. his character Mr. Gradgrind in the novel Hard Times).

The intensity of the exchanges in therapeutic discourse in the CM suggests an unconscious patterning of meanings in that patient and therapist must meet the unscripted challenges of the moment and the responsibility of their “role”, whether as patient/sufferer or as interpreter/guide. It may not be a surprise to experienced therapists, therefore, that the discourse resonates with the oratorical forms discussed in drama and in persuasive texts of politics and law. The building of an argument through a chain of logical divisions or enthymemes (commanding two step generalizations) will be exemplified again through the grammar. Let us offer the following illustrations (see Table 6):

Example of parallelism in patient discourse (‘Ruth’).

| P: | (cl: 661) Y’know And that is the sort of fear [[that I live in]]. (cl: 662) That’s the fear [[that I live in || when I come to city A or parts of city B ]]. (cl: 664) That’s the fear [[that I live in || when I walk into a bar || and think || << if I am on my own >> is … male/name … going to be there with his friends ]] |

Parallelism can be an ‘impact’ factor in the language situation, in the rhetorical arrangement of messages (as we can see here); it can be evident in the wording (here again); in the sounds – the syllabic rhythm (as in the metre of poetry or verse) or in the intonation. In the above, we are presented with a definition of the fear Ruth experiences in a formulaic opening clause and a following embedded clause, then by two clause complexes. The building of impact in this way can be thought of as clinamen/climax: the Greek notion of a ‘ladder’. It also contributes to the enthymeme – the sense of progressive, if sweeping, argument. The following is an example of argumentative closure (in agreement) from a sexual abuse victim and her therapist. These simple exchanges are drawn from a session we will see again under the sub-section on cohesion and cohesive harmony.

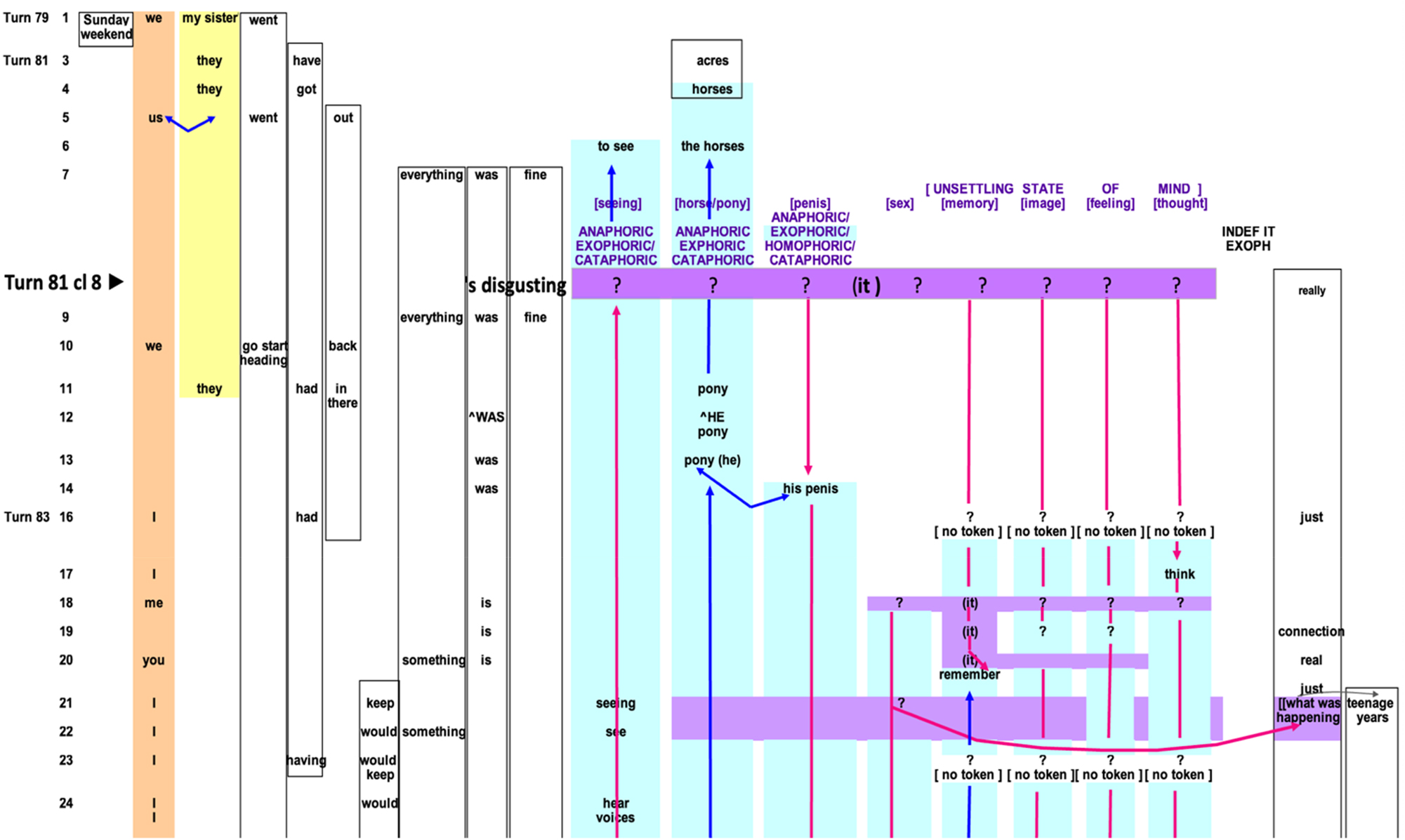

The extract of “J.” and Therapist (below) shows them stepping methodically through associations that can overtake J in daily events. In the session, these have disoriented “J.” (perhaps with dissociation). She has been encouraged to present a recent episode of trauma which was expressed violently in her body and mind (see Table 7). The dyad sorts these reflections and arrives at solid agreement.

Joint navigation of possible patient dissociation to patient/therapist clarity (patient ‘J.’).

| P: | [Is it ] something [[I am making up]] or is just my humanness [[doing that]] or … |

| T: | It is very confusing, but then from the past there were always images [[associated with anything sexual]]. Mmmm |

| P: | (silence) |

| T: | It seems to me like you are associating with the sexual images, the sexual connotations with just something of [[what the image is]], [[what you see now]]. You see the pony’s penis; well for that matter one can see, you know, pictures, and one can see naked bodies in reality. |

| P: | Mmm. Yes. |

| T: | But does that mean something sexual? But it seems like the association … |

| P: | It doesn’t it shouldn’t but with me it does. |

| T: | Yes. |

Notable amid the many aspects of this session is the shared formulation of fact from misleading bodily and psychological signs around the profound challenge that the patient has experienced: her chest pains are real but not a heart attack; there are fusions as well as fissions in the fragments that come into her memory or imagination after teenage years (of sexual abuse). The dilemma is like an aporia: an impasse, a situation for which one does not have the resources. She formulates it with clarity after a vortex of confusing reports to the therapist: she does not want to “delve” into the disturbing visions; but equally, she does not want to begin a period of happiness only for “it” to come back and hit her.

A subtle dramatic effect of zeugma can be exemplified from the earlier transcript by repetition of phrases concerning the restaurant. The lines have similar wording but an oddness due to a difference of grammatical roles (see Table 8):

Example of patient use of zeugma (‘Ruth’).

| P: | Everyone’s there with someone … (117) and I’m sitting there ||with tears running down my face|| (119) |

The “with […]” expressions seem to be in parallel as wording but they are not parallel in phrasing or grammatical role. First of all, clause 117 is a relational process (here an “is”) and the “with” is for personal accompaniment. In clause complex 119 on the other hand, sitting is a material process with a hypotactic clause which is not about accompaniment. There are odd effects – Ruth is doing something, though static “sitting”, and then the tears are given the status of doing something active (they are “running down [her] face”). The effect is of a personal attribute over which she has no control. She is the locus or affected […] quite different from the alternative of saying ‘I was crying’ (in which she would be cast as an actor).

It is possible to see in these examples how the discourse becomes poetic, what the poet Yeats called “ordinary language somewhat heightened”. Consider Ruth’s use of zeugma and the transitivity of being under the control of other forces: “fear I live in” (clause 662); “I couldn’t stop crying” (clause 99); and the enthymemes behind the tropes of protection and entrapment: “This is my shield; this is my guard; if I let this go, it’s unimaginable” (clause 416–419); “sometimes I don’t realize|| how trapped [[I am]] || until I run into these people” (clause 433).

The transforming argument about beauty in agony and that Ruth will persist (“I’ll just […] do [[what I do]] (clause 1036) is itself a construction of semantic intricacy: it utilizes the cultural value that great beauty or genius is experienced in suffering (“what you are good at” clause 1026) and integrates a spectrum of specific issues, including the attitude of the previous therapist. This interpersonal progression – a renewed inclination to a positive future – is made explicit as a bodily gesture (“I want to reach out to you Ruth” clause 1029). These steps up a ladder of dispositions (clinamen) towards the final section of coherence – “sitting together in hell,” committed to resolving the “puzzle” – sometimes taking the shape of an abstract defining statement – i.e. a complex verbal equation. This seemingly straightforward structure is followed by a kind of ‘unpacking’. Such semantic patterns sometimes even work like a chiasmus: the series of steps is then reversed to arrive back at the initial general statement, subject however to the information drawn from its expansion (again, arriving at a familiar semantic locus but seeing it as if it were for the first time; an established trope, for example, used by the poet, T.S. Eliot: see Little Gidding in Four Quartets).

4 Grammar and the preoccupation with acts of definition or identification

The rhetorical structure of Ruth’s interactions varies markedly, as indicated by the figurative graph in Figure 2 above. There is the recount of her suffering in the first 200–300 clauses or messages; there is the struggle of establishing the authenticity and relevance of therapy in her circumstances; and finally, after 1100 clauses, clause complexes/messages, Ruth and her therapist share the inquiry into a “third” presence in the discourse, a palpable “it” which they will un-cover while sitting alongside each other. The “third” allows for a common perspective on something separate from themselves. This “it” has been under construction across the dramatic variations in the “forms of feeling” in the 55 minutes of the session. The presence is indicated by a grammatical syndrome of verbal equations (X is Y) which define crucial reports of self states. The equational nature of many of these clauses is not obvious due to the way the acts of definition (the X is Y structure of the overall or matrix clause) are made complex by embedded clauses in the X and Y roles. A straightforward example is seen in Table 9.

Example of patient use of equative constructions (‘Ruth’).

| P: | And X [[ all it does ]] is = Y [[harm me]]. (265) |

Another, closer to the kernel of her self enquiry can be seen in Table 10.

A second example of patient use of equative constructions (‘Ruth’).

| P: | [[What he does to me]] is = politeness [in the weakest way possible]. (601) That ‘s = [[ what he does]] (602) |

These reversible clause patterns can give the impression that a great deal is ‘happening’; and that is an accurate impression. But their semantic contribution is recoding, not material action. They change the symbolic address: something manifest (e.g. [politeness in the weakest possible way]) is allocated a value or role [[what he does (to me)]]. The two roles in the equation can be gauged by what Halliday regarded as the “represents” test: substitute the verb represents for the verb is and check on whether the passive form (is represented by) is more ‘natural’. When represents (active) is natural, then the manifesting/token is the subject of the clause. If is represented by (passive) is the more natural, then the subject of the clause is the role/value being introduced into the discourse. This shows how new material is defined and brought into the semiotic refinement of the meanings being exchanged, see Table 11.

Transitivity analysis of patient’s equative constructions (‘Ruth’).

| P: | [[What he does to me]] | is | = politeness [in the weakest way possible]. (601) |

| Role/Value | Process | Token | |

| P: | That | ’s | = [[ what he does]] (602) |

| Token | Process | Role/Value |

These clauses do seem unremarkable. But they are the “engine room” of semantic diversification in that they enable speech to move to new ways of seeing: a manifest aspect of experience is allocated the status of a token of a more general role in the scheme of personal and community interpretation […] it is endowed with a value. The verb in such relational clauses appears to be one of a relatively ‘neutral’ set of non-agentive, ubiquitous grammatical forms: is, means, equals, has, represents, becomes […] (see a full discussion in Halliday 2004 [1998], and Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: Ch. 5). William James, in a revealing discussion of represents (1904 Section III) focusses on the identifying relations concerning the crucial duplex self – the double of ME/I discourse (1892: Ch. 3). Across world languages, the token to value relationship might even be realized by nothing morphological other than the adjacent positioning of two elements (see Verhaar 1967–1972).

The silent legislation of thought behind this core but minimal domain of the grammar in English can be seen in the simple injunction that: “God is love”. Consider which is the token and which the value. In the unmarked case, subject in the clause is token (i.e. the clause is active). Hence god represents/is (a manifestation of) Love. Theologically, most religions would reverse this so that love is (a manifestation of) the broader principle of God (so, value to token: i.e. God is represented by love i.e. Love is [in reality, a manifestation of] god). [For a discussion of the 8 ways in which this clause can mean differently, especially in relation to context and James’s “duplex self”, see Butt 2023]. Through the identifying function of a clause, the culture – its notions and measures in science; its judgements in art; and the defining forces of one’s psyche – can be included in the “re-evaluation of all values” (to echo Nietzsche). These developments are the theme of the major study by Halliday and Matthiessen (1999): “Construing experience through meaning”. They are central in the thesis on the experience of the plague of Athens, as represented in the language of Thucydides (Kappagoda 2004). Verbal equations in the role of identifying clauses are also the semiotic portal to the subject/object, duplex construction of self in William James and in the Conversational Model (Butt 2023).

In the short opening segment below (see Table 12), a patient (C.) unloads an account of her last three weeks to the psychiatrist (R.). The strategy of response by the psychiatrist reflects the function of grammatical acuity in the formulations of a therapist. The patient imparts her experience of the out-of- control period, and concludes with: ||I can’t help || but blame myself|| for what happened||. This is a hypotactic clause complex (or hypotaxis with an embedded element): 1) α, 2) αβα, 3) αββ. It appears in its wording to accept responsibility (blame). But the “meaning of the grammar” suggests that the clauses, following the “roller coaster” metaphor, are beckoning for an alternative evaluation: the αββ clause is down 2 depths (or embedded [[…]]), and the transitivity of the clause itself is akin to an ‘accident’ or ‘weather’ report: a “happening”. The therapist recognizes the beckoning by responding with modalizing the certainty with a self-projection: “I imagine […]”. The projection – “there was a conflict” is an existential clause which accepts the absence of responsibility as if “an act of god”.

Opening exchange in therapy (patient ‘C.’) showing effect of taxis choices.

| Th: | Sorry for the interrupting at the beginning |

| P: | It’s been a roller-coaster for about three weeks. Panic full blown … |

| Th: | It really seems that you did something that wasn’t your fault, ups and downs |

| P: | It just really hard to … take my self … I have to take responsibility, I saw it coming. When I can here I was really pepped up, but I still had enough incentive to understand the situation, but I kind of let it roll, I didn’t put the brakes on or anything and didn’t do any of the things that could have helped it from going where it went, you know? I just … I can’t help but blame myself for what happened. |

| Th: | I imagine there was a conflict |

In the following series of exchanges between a psychiatrist (trained in the CM over decades) and a young patient (after more than a year of therapy), we can see how the sequence of principles of the CM exemplified in the session with Ruth is activated, despite the very different initial tenor and the considerable social distance between the middle-aged professional male and the anxious female tertiary student. The session is c. 11 pages of transcript, and the opening page is gentle banter over the technology paid for by the university (for research recording) and the therapist’s use of old technology (see Korner 2021: 151–162). There is a tone of permission to exchange humorous observations and self-deprecations. Yet this is transformed by the patient’s concession about her own behaviour (see Table 13):

Banter as a bridge to ‘real’ therapeutic work (patient ‘P’ and her therapist).

| T | … up for me. |

| P | Nah! Nah! … ? |

| T | Oh I hope … |

| P | [Laugh] I take it all back. Tell you what, it’s like dressing, dressing like you actually, have to present. It’s hard work. |

To this the therapist leads with a cautiously modalized, scrupulously framed challenge. Work has begun in earnest as a simple remark becomes a spike of strangeness that needs understanding! (Table 14)

Real work begun (patient ‘C.’ and her therapist).

| T: | 1||You have never, sort of- 2||I always get the sense, 3||but I’m not sure 3.1[[if I’m right]],|| 4but I always get the sense 4.1[[that you never really enjoy the girlie things]] ||? |

This gentle (but personalizing) hypothesis is immediately contradicted by the patient, to which the therapist in turn leads with paradox: being glad to have got the issue out and done with […] But from that denial comes an extended unravelling of sadness, loss of intimacy with a mother who has “shut down”, and a pattern of constricted experience that has blighted the young woman’s ability to put her self out “on the line” in life, with other people and with her exams. There emerges a series of connected vignettes which travel deeper into the texture of the patient’s own memory of disparate observations, by others, and by her own insight (see Table 15):

Patient contradicts therapist (patient ‘C.’ and her therapist).

| P: | No, that’s not true. |

| T: | OK. Well I’m glad that I raised it. |

| P: | Sorry? |

| T: | Hm-mm. |

Concerning a friend, the patient recalls (see Table 16):

Contradiction of therapist leads to deeper insight (patient ‘C.’ and her therapist).

| P: | And, after much prompting, ‘cause she really didn’t want to be saying anything hurtful or could be interpreted the wrong way. She, she said that she felt that it was as if I’d missed out on the feminine input. |

| T: | Right, so she was approaching it from a- |

| P: | Which is interesting, because it was, it was my mother, as you know, was totally neurotic. |

| T: | But I’m not sure that I understand what that means in the. |

| P: | The feminine input? |

| T: | Well yeah, in terms of the context that we are talking about! |

| P: | Well I think, well, oh sorry you mean girlie? |

| T: | Girlie, feminine. |

| P: | I think she was still talking about a sort of softness- |

| T: | Mm. |

| P: | - or something. |

| T: | Do you feel any twinge of sadness as you’re saying, as you’re saying that? |

| P: | Yeah, it’s very sad. |

| T: | Yeah I was going to say I think it’s more than girlishness … or girliness I should say it’s almost like you missed out on a whole lot of stuff. |

| P: | That’s what my friend said when that I missed out on the feminine input. |

| T: | I’m just trying to imagine that’s got to be a terrible experience |

| P: | For her? |

| T: | No for you! To be you know, in a relationship with a mother who is chronically shut down. |

| P: | Yeah it was awful. |

| T: | You know when you say that it’s almost like you become slightly detached from yourself. |

The therapist accepts no partial explanations, and his requests prove productive. This is a deeper observation into the patient’s own experience of the self: a form of detachment from the natural flow of never experiencing an intimate relationship (see Table 17):

Apparent banter helps reveal latent self-understanding (patient ‘C.’ and her therapist).

| T | Well that’s interesting to speculate. Because my sense is you know in terms of when - |

| P | Open a door … go on. |

This continues the banter in recognition, however, that the therapist has reached into an insight that may have been incipient to herself, but which was latent and needed to be revealed, or un-covered (see Table 18).

Latent self-understanding explored further (patient ‘C.’ and her therapist).

| T | My sense is that you do get it now and that saddens you. |

| P | It’s the lack of - |

| T | The intimate relationship. |

Therapeutic discourse moves in the direction of identifying the mysterious “It” at the centre of a traumatized sensibility. Here we see the defining move. This “It” is also taken up in the illuminating psychological poem by John Wain “The Bad Thing”. Usefully for the present topic, of coherence and cohesion, in their Cohesion in English, Halliday and Hasan (1976: 344–345) analyse the cohesive devices in this dramatization of mental illness.

The preoccupation with identifying or equative clauses can also be reviewed by returning to the is/’s/was/am forms of the Ruth text (see Table 19):

Further critical examples of equative clauses from patient ‘Ruth’.

| P: | That’s [[what I was doing with [the] … thing]] (61) |

| P: | I mean (120) that’s really the reality I think That’s no fabrication. That’s my life. That’s it. |

| P: | He’s so good [[ at making [[me feel bad for [[who I am]] ]] (215) |

| P: | but what my essential being is. (217) |

The therapist replies by trialling defining clauses which couple or amplify the patient’s material; but she also introduces existential clauses (viz. There is […]) which lend a certain objectification in that they move the discussion out towards something that ‘is the case’ separate from mentioning the person involved. In this move the therapist has begun the semiotic construction of a “Third” presence into what was a face to face dyad (see Table 20):

Therapist’s critical use of equatives (with patient ‘Ruth’).

| T: | There is a real sense || that your spunky alive you || you reach out to somebody [[who can’t receive it]] (299) |

| P: | [[ who can’t receive it]] |

| T: | Um and so there is something [[ so deeply shamefully and then angry making and devastating.]] |

This phase does return to the person to whom Ruth reaches out – “he’s the one || he’s the prize”, But “That’s the agony of this” is being narrowed down to the root system, not the person but “[…] you keep wanting him to want it”. Ruth arrives at the crux of persistence and an Einstein quote she has cited with its equative conclusion: Clause 265 (see Table 21):

Ruth’s equative conclusion.

| P: | And | [[all it does]] | is | [[harm me]] |

| - | Value | Process | Token |

Ruth and her therapist move towards three achievements. Ruth (i) secures evidence that the depth of her suffering has been validated; (ii) her situation has been reconstrued as a context of agonizing beauty; and (iii) the root of her problems is not just in the gaze or evaluations of others, but in the “madness” of repetition – a puzzle that they can sit and examine as a “Third” element that they share. There is progress in the reification of a problem, even if that involves a battery of definitions/equative clauses at the peripheries of a problem, and a nominalizing with “IT” at its core. The technique of the therapist and the trust of the patient have externalized the difficulty, at least for the session and for the sustained memory the session establishes.

Discriminations, then, in grammar and cohesion assist the therapist: they focus the analyst’s sorting of what is or is not sustained in the choices of the patient’s language; they assist in the professional examination of evidence; and they assist psychotherapeutic theory in describing the dialogic tools that separate professional interactants from those with empathy but without necessary training.

5 Reflections and the “knight’s move”

The meanings that a speaker makes in language can be probed as the “news of difference” between the choices or alternatives available in the language system, whether or not one regards the choices as conscious or an unguarded, unconscious response (see Bateson [1979: 68ff] on “news of difference”; and Halliday [1973] on choice in semantic contexts). As Whorf emphasized, and his teacher Sapir before him, it is the “unconscious patterning” that carries the deepest information (e.g. Sapir 1951) about value and social positioning: The efforts of Bernstein and Hasan on semantic variation carry the concept of “niches” of local communicative experience to a necessary extension of human evolution, the crucial niches of human ‘being’. Hasan’s “semantic variation” deals in the expectations of continuity through how one makes meaning and how one demonstrates social solidarity (see Hasan and Cloran 1990). But we seek an account of how insight can bring about a creative extension or break with the patterning that is, ultimately, efficacious in living: how does a counter expectation work like a “knight’s move” in chess?

The creative and even poetic dimension of therapeutic exchanges are much cited, and even assumed (e.g. Meares 2016). In the sessions touched upon above, we can draw some observations with the respect to what drew Halliday and many other luminaries to, for instance, a theory of creative insight, and (coincidentally) to a related enthusiasm for the ‘great detective’ genre. Others who have attested to this interest include A.R. Luria; Umberto Eco; Oliver Sacks; Ludwig Wittgenstein; Michael Cole; and Jerome Bruner. Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose is celebrated; but there is also his “Guessing: From Aristotle to Sherlock Holmes” (Eco 1981). The creative constructions of cultural complexity are relevantly argued in various influential studies of scientific evolution – for example by Snell (1953); Gregory (1981); Lloyd (2002); and, most directly with respect to the role of right brain functioning, by McGilchrist (2009).

The rhetorically intensified moments of Ruth’s discourse, and the drive to define “what my essential being is” (in equative and attributive relational clauses), offer the therapist a highly enhanced range of wordings to which one can respond in two ways: one can note the lexis and its recounts of men and of back biting neighbours etc.; but additionally, one can read the structure of the formulations, their syntagmatic organization – the ways in which they communicate Ruth’s deeper priorities (her anger at herself and at her obsessions; her regrets about her mother’s mental illness; her fear of a future without value).

6 Appliable linguistics

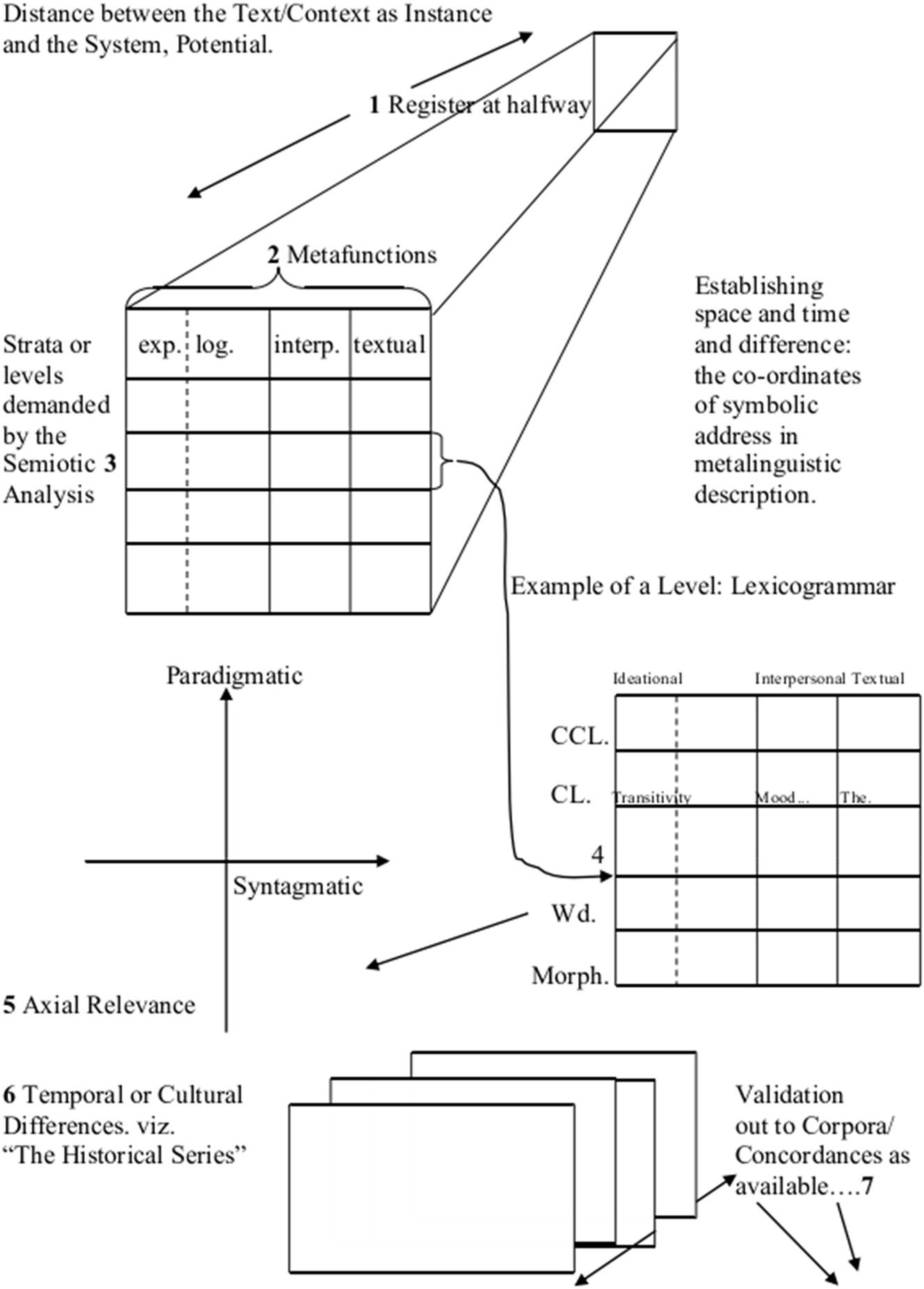

The global architecture of Halliday’s theory of language is organized around the distinctions one needs to make in order to produce useful statements about meanings and the way meanings are both motivated by a context and at the same time responsible for directing the shape of that emerging social event. It is a proposal for managing the internal relations of a language system as well as for capturing the vector character of action in social process. To be applicable to the problems which communities experience with language, Halliday proposes that we remain clear about:

the distance between an emphasis on the instance or uniqueness of a given text; the distance between it and the systemic choices that language offers; and the stages along the distance (a cline of instantiation) along which one might choose to group texts as relevant types, registers, or genres.

the pattern of subsystems which ‘wire’ together, that is that most closely influence choices in each other. These interdependencies are the basis for metafunctions: tendencies of meaning towards interpersonal; experiential/logical; and textual, text building resources (the latter being especially involved when evaluating the sustained coherence and cohesion of human interactions).

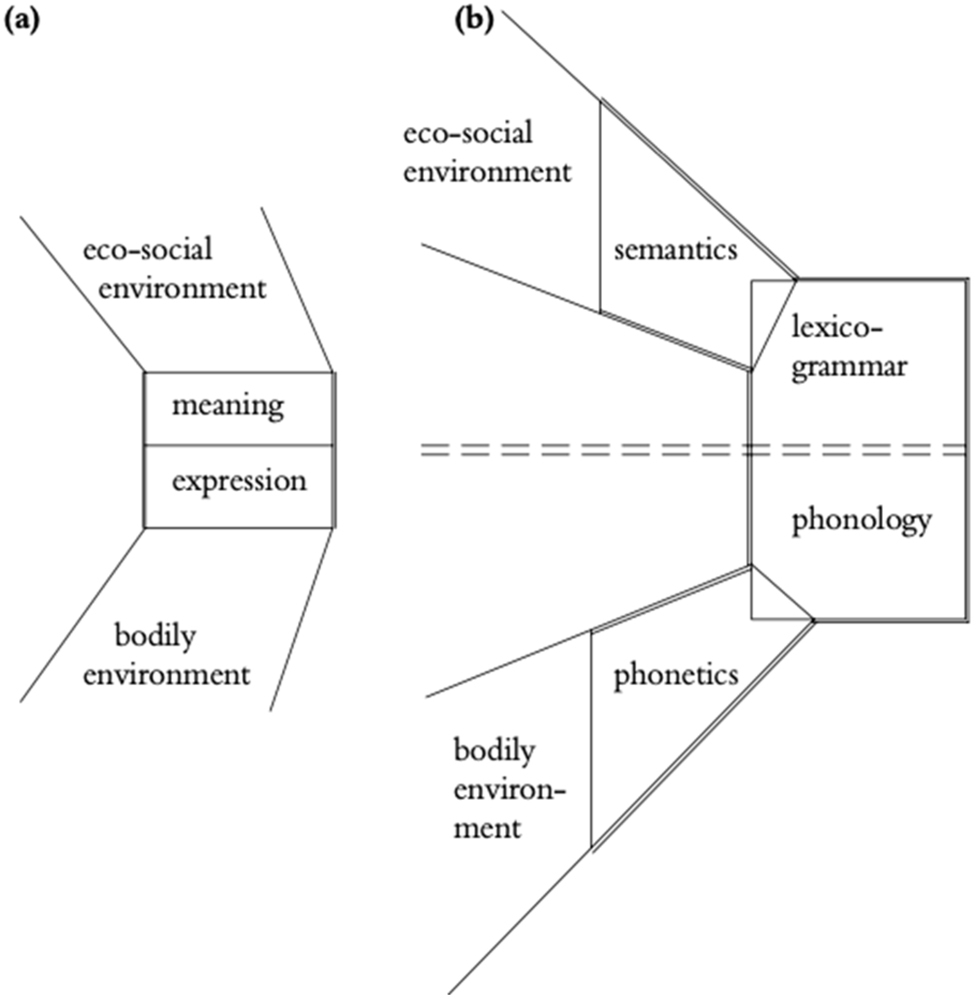

the stratum (or level) at which a relationship is evident – namely, in the social configuration; in semantics; in form (lexicogrammar); phonology; and in the material substance of phonetics or graphology. We can see here that all the traditional levels of relevance are plainly invoked, but with the important observation that a material order in society (the context) is re-re-represented by patterns before the exponents of the patterning return to the material of sound (phonetics) or graphic substance. Language organization deploys meaning potential by patterns of patterns interceding between two orders of matter – human actions and acoustic substance (or other material options as in the languages of the deaf and in some semiotic patterns which Peircean semiotics would describe as indexical).

the word rank, in a rank scale, which is used to distinguish componential relations at each level, with the componential being totally distinct from level or stratal relations, which are abstracted patterns of realization.

the ‘three times of text’: the phylogenetic time of the history of the culture; the ontogenetic point of view of change in the life-span of individuals; and logogenetic time – the duration and sequencing of the text under discussion. The logogenesis changes the range of options open to the interactants in a dynamic unfolding, for example, a nominalization of an event is available after one has a report of an event: “FIFA sponsored the event, so the sponsorship was well above what was expected. The expectations were too low”).

A helpful way of summarising much of the above visually is given in Appendix, which shows what we might call the “symbolic address” of various systems according to metafunction and strata, and with the ranks of the lexicogrammar projected out into a sub-component table.

In Figure 4, the re-re-re-representation of the adult language is evident between the two levels of material order; that is, between the ecosocial environment (including the contextual configuration) and the bodily environment (including the patterning of sound and gesture).

Protolanguage (a) and language (b) in relation to their eco-social and bodily environments (after Halliday 2003).

While linguists have been misunderstood due to popular caricatures – with studies of accent, rules of correct speech or writing, and eccentric lexicographers – it is reasonable to argue that many theories in modern linguistics have been overly preoccupied with atomistic units of language, that is with breaking up language into words, groups, phrases, clauses and syllables and tone groups, and with the way in which such units can be ordered in a syntagm which is autonomous or formal. Yet the relevance of textual coherence, particularly after Cohesion in English (Halliday and Hasan 1976), has become a topic which brings together the linguistic analysis of whole texts with congruent work in literature; narratology; the teaching of academic writing; training in professional registers; and a strong interest in communication in critical contexts of medicine and law. A wide discussion has ensued as to what constitutes coherence of text and whether this quality could be recognized, defined, and even measured (i.e. as degrees of coherence).

The various linking devices explored and tabulated in Cohesion in English (Halliday and Hasan 1976) were criticized by linguists and teachers as “epiphenomenal” (e.g. Morgan and Sellner 1980) – namely, not criterial for textual coherence, but only supporting such cohesion. Without the full Hallidayan model of language in context, a limited understanding emerged, especially in America, even as a new era of ‘pragmatics’ was being espoused, an era of reaction against the ideological grip of Chomskyan abstractions concerning “the sentence” and an autonomous syntax (e.g. Levinson 1983: xiii).

The work of Hasan (1984, 1985b) clarified many of the central concepts of cohesion with her exposition of “cohesive harmony”, along with later network models of options in a paradigmatic treatment of semantic variation. Hasan’s work was based on social class variation in semantics, and in the ways in which projections of the self are framed by parental and social authority: how is the child’s identity and angle on experience constructed through talk with parents and teachers? how is it that explicit or positional authority is made oblique, more implicit, and even internalized by a child across social contexts and their enactments of semantic roles? (Hasan 2009).

7 Cohesive harmony

Although not available in published form until 1984, since the 1970s Ruqaiya Hasan had been developing a straightforward but ingenious method for demonstrating degrees of coherence across the wording of texts. The method also offered a useful, plausible measurement. Beginning with Halliday’s experiential metafunction, Hasan made chains of similar lexical items – i.e. similar on the basis of sense relations: synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, meronymy, and collocational evidence (i.e. only items established through close proximity in a thesaurus). Such columns of similarity chains added to the emerging of referential chains – the items like pronouns or definite articles that signalled sameness of identity. These chains (aligned against line numbers down a page or screen) provided the first iconic version of the topics that emerged and their participants in a text.

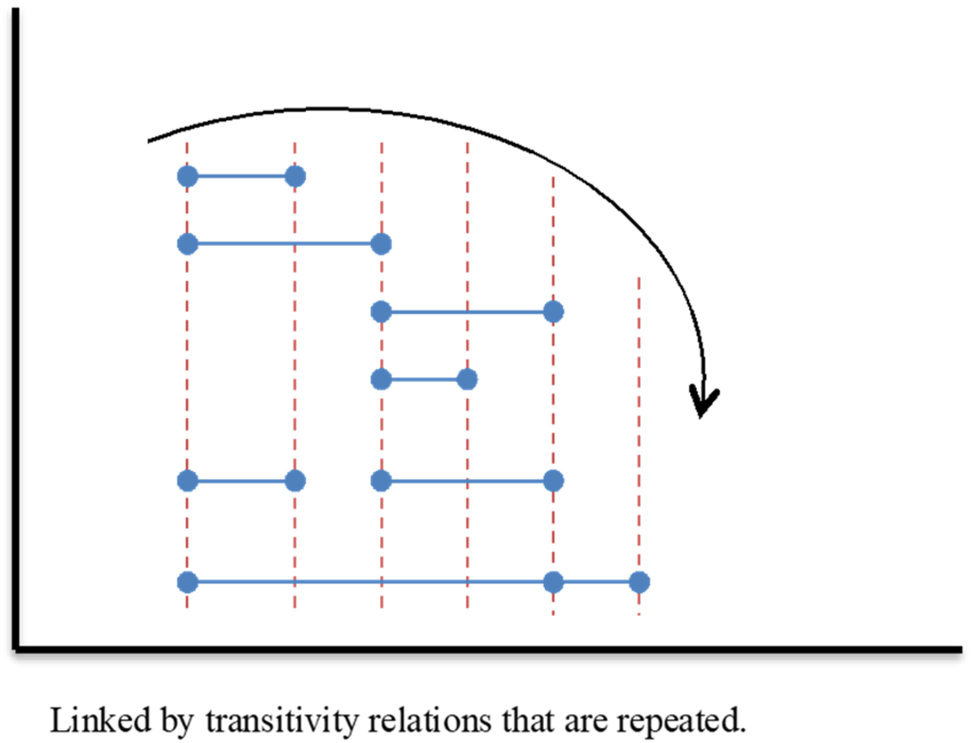

With these in place, one can begin to read off the topicality and its densities, interludes, switches, and even clusterings of words (Hasan refers to tokens). These could also function as indices of an element – e.g. a finale/conclusion – in the generic structure if they appeared to collocate in converging connections (see Figures 5 and 6). We can regard this columnar chaining as the first of 8 steps which produce greater and greater iconicity, and ultimately some useful measurements of texture.

Are you ‘seeing’ topical development? Is there a rapid pick up of new chains of tokens?

How sustained is a lexical domain (is it text exhaustive and/or only a brief segment)?

How dense and regular are the relevant tokens? (a closer look at distribution).

What is the quantity of items/tokens in the semantic ‘field’ of the chain?

What of referential chains (Identity Chains), based on pronouns and definite articles which signal the continuity of a thing or participant, when these are also placed alongside the similarity chains?

What appears early in the text? What late? Is there a ‘sense of an ending’?

What of chain interactions? These are the reiterations of the grammar of transitivity. [At this stage, Hasan introduces the grammar as a cross stitching: i.e. when two (lexical) tokens in one chain are in a syntagmatic connection with at least two tokens in another chain, they are “echoed”. The echoing across chains allows us to designate the interacting tokens as central tokens (CTs).

Measures of coherence can be derived by a straightforward counting of proportions of different tokens: e.g. peripheral tokens (PTs) – all those that did not qualify by sense relations as relevant to chain building, can be simply expressed as a percentage of all the relevant tokens (RTs); so too peripheral tokens can be gauged as a percentage of central tokens (CTs); then central tokens are crucially expressed as a percentage of relevant tokens (RTs). This last comparison of CTs to RTs is the best guide to a measure of interconnectivity, of cohesive harmony.

A key principle for allocating tokens in a rendered text into cohesive chains and its implications for interpreting topic development (after Halliday and Hasan 1976).

Abstract representation of the interaction between cohesive chains that can be measured as cohesive harmony and interpreted as texture (after Hasan 1985b).

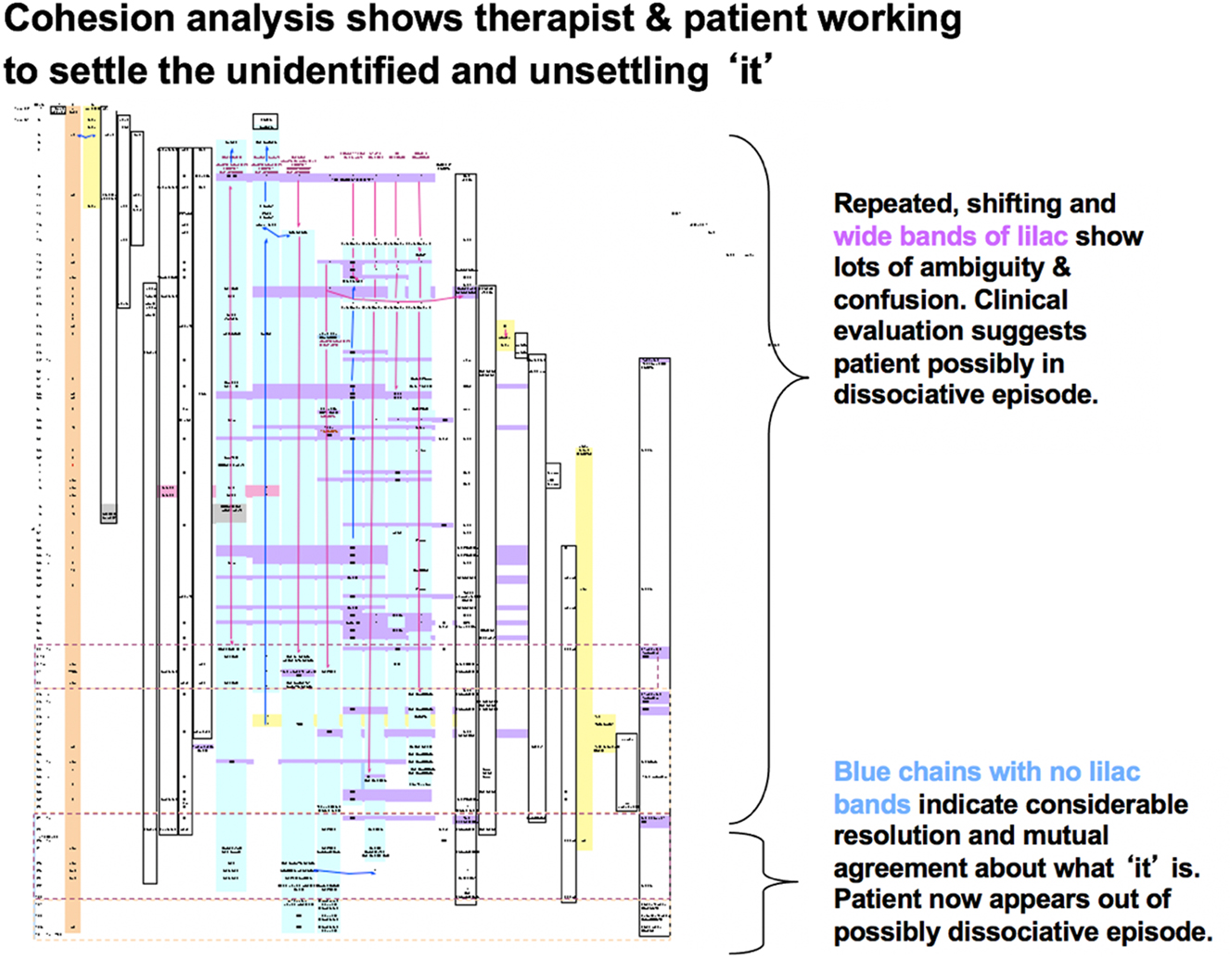

Figures 7 and 8 are limited to displaying how the question of what is being talked about – for example, what’s disgusting – must be jointly established and how important strands of meaning in therapy can remain unclear or unconfirmed (sometimes in a productive way of course). As outlined above, an important further step can be for the analyst to bring out not just what those strands are or could be, but how different strands interact. To illustrate the metrics of this approach we give some example figures from Khoo (2013) who estimated the degree of ‘cohesive harmony’ of the psychotherapeutic interaction she was investigating as follows:

Relevant Tokens (RTs) – 505

Central Tokens (CTs) – 396

Peripheral Tokens (PTs) – 22

Total Tokens (TTs) – 527

Ratio of Central to Peripheral – 18:1

Central as a % of Relevant – 78.4 %

Central as a % of Total Tokens – 75.1%

An overview of the cohesive chains in the potentially dissociative episode in the consultation between patient ‘J.’ and her therapist, showing topic clarification and development (after Butt et al. 2007).

Cohesive chains in patient’s possibly dissociative episode, displaying ambiguity regarding potential referents for ‘it’ in her evaluation “It’s disgusting” (after Butt et al. 2007).

As Hasan (1985b: 94) notes: A text is more likely to be coherent if:

the ratio of relevant to peripheral tokens is high;

the ratio of central to non-central tokens is high;

there are no or few breaks in the chain of interaction (viz. all chains are conjoined at some point).

Hasan found that the “the best-oiled texts” seemed to be those whose Central Token/Relevant Token percentage was c. 70–75 %. At that relation there appeared to be an optimum balance between new topicality (building a text) and the reiteration of the threads of meanings in play. That is to say that the configuration of new as to established items indicated not just a table of cohesive devices but a degree of “cohesive harmony”.

Such a measure proved illuminating when we witnessed psychiatrists debating whether or not the patient had ‘fallen apart’ into a dissociative state. The often short periods in a transcript over which there was debate could be measured for ‘making sense’, and also whether the segment might be a harbinger of positive change. An additional factor of iconicity was whether or not the cross linkages of central token left any of the similarity and identity chains isolated (i.e. without the cross connections). This would indicate a lack of cohesion which needed investigation. In some cases it was just that: disconnection. Of deeper interest, however, was that the ‘gap’ could also signal an implicit relation – the speaker (or author) may be citing a parable, a coda, or analogue which is left to the hearer to construe (to make a leap of insight as to the parallel of meaning). There can be semantic parallelism without any repetition of wording.

It is useful to recall Firth’s injunction of meaning being made at all levels, hence “semantic meaning”. Such analogical leaps and tropes (redirections of meaning) are crucial to the views of Meares in the therapist’s ability to make sense of disparate “pieces”. There is also a connection with Halliday’s concept of the “knight’s move” in discourse (see Section 5).

8 Halliday and Hasan, and the influence of Firthian thought

Having mentioned a number of the linguistic notions which show how Halliday and Hasan developed and refined traditions of linguistic practice, it is best to list a number of concepts which need to be appreciated as differences in SFL, in particular certain aspects of a Firthian approach to process, analysis, and the ensemble contributions of language patterning. The ideas of J.R. Firth actually worked as a background of principles that directed thinking in SFL more deeply than understood by even some of those who worked with Halliday in the U.K. and since, in Australia (see Butt 2001).

With the focus of this paper on a cross disciplinary exploration of “coherence”, the following list (I–XIII) begins with the terms text, texture, and contextual ‘fit’. The terms are the foundation for an evidence-based approach to language and the social order including, for instance, semantic indices of class, gender, social activity, and the role of persons in an activity (e.g. parenting; hospital based surgery; technical repairs; teaching at different levels). Hasan’s more than a decade of research projects in Sydney exemplify the pursuit of connection between ways of meaning and social variables – differences of class and gender (Hasan 2009).

In SFL, describing the text of a language is an attempt to account for a coherence between social context and meaningful expressions. To this purpose, form is a word applicable to all the devices that extended text to itself and to the social outcome – the semantic consequences in the interaction. These devices encompass many of the concerns of the linguistic pragmatics as it re-emerged in 1980 after the syntactic absolutism of two decades.

Meaning is made (shaped) by choices on all levels; so there is, for instance, phonetic meaning, and so too semantic meaning;

The grammar and the semantics are levels of “content” (after the terms of Hjelmslev); Saussure’s (1959 [1916]) line of arbitrariness runs between grammar (lexicogrammar) and phonology, not between meaning/semantics and sound;

The names of systems in the grammar (like transitivity) indicate a domain of grammatical meaning, so that questions like “Is transitivity in the grammar or in the semantics?” miss the point of what Halliday regards (again, following the term of his supervisor, J.R. Firth) as the “ineffability” of grammatical categories (Halliday 2002 [1988]. This word is merely reminding us that all paradigms in a language are totally relational – i.e. uniquely defined by all the “valeurs” specific to that community practice at a given period in historical and phylogenetic time. The fact that linguists need to use similar terms over and over (mood; tense; modality) to approximate to the functions of choices across different languages does not absolve us of the responsibility to defend the relativity of systemic descriptions. For example, we use all levels of language to create conditions for referential reliability in the specific context of culture. Languages do not then ‘refer’ directly to reality: they provide resources so that individuals can achieve a working approximation of reference, from indexicality to the hypothetical existents within a cumulative structure of cultural meanings (consider how terms like strings, empathy, enthusiasm, charity, war; all need a framework of culture and theory to be understood).

Halliday’s use of the unit “phoneme”, for instance, needs to be seen according to the phonological demands of the particular language. He noted that it made no sense to go beyond the syllable in the case of the depiction of Mandarin. Consequently, in his process/prosodic oriented analysis of the syllable in Mandarin (see Studies in Chinese Language: Vol. 8 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday [Webster 2006]; and reprinted in LaPolla 2018), Halliday shows how there is a limit to the atomism of analysis – the system produces a number of contrasts based on an initial, a trajectory, and a final. The prosodic contour arrests atomism in a challenge to componentialism of sound;

The many recent pragmatists (from e.g. Austin, Grice, Searle, Leech, Levinson) do not figure as centrally in SFL as in some literatures, mainly because the anthropological orientation of Firth and the School of Oriental and African Studies (S.O.A.S.) was always committed to “contextual parameters” and relatively localized notions of what to describe – for instance see Mitchell’s (1957) study of purchasing horses in Cyrenaica. Firth (1957b) called such studies of the “typical actual” (rather than the general/ideal) as the analysis of “restricted languages”. Halliday’s own doctoral study. The Language of the Chinese Secret History of the Mongols (Halliday 1959), was, according to Firth, an example of a such a restricted language. Firth thought that global descriptions of English or Chinese were misleading in that they were too distant from actualities. Halliday’s theory takes “registers” over from Ure (1969), and Ure and Ellis (1977).