Abstract

This study investigates the strategies used by Iranians to express sympathy to the bereaved via social media. A total of 211 authentic condolence messages for the loss of a contemporary Iranian actor were selected from Instagram and Facebook. The researcher analyzed the data and identified six strategies, which were then evaluated by two external raters. Cohen’s κ result showed substantial agreement between the raters (κ = 0.855). The strategies were categorized into major and minor groups. Praising the deceased and expressing sorrow were major strategies, while poetic expressions, emoticons, prayers, and complaints about the current situation were minor strategies based on their frequency.

1 Introduction

One of the most challenging moments in life is coping with someone’s death and trying to comfort the bereaved experiencing deep sorrow. Many people are uncertain about the appropriate behavior in such situations and may hesitate to offer condolences (Farnia 2011). Additionally, circumstances might prevent individuals from directly addressing the deceased or expressing their feelings to alleviate sorrow. Samavarchi and Allami (2012) noted that silence is sometimes used as a strategy for offering condolences, although this may not always be a conscious choice. Various factors, including age, gender, ethnicity, education, and religious beliefs, influence how people express their sympathies. These factors lead to sociolinguistic and socio-pragmatic diversity in condolence strategies. Most studies (Al-Shboul and Maros 2013; Elwood 2004; Farnia 2011; Hwayed and Al-Ameedi 2022; Pishghadam and Moghaddam 2013; Samavarchi and Allami 2012; Weaver et al. 2019; Wiener et al. 2018) have focused on sociolinguistic strategies evident in written messages, but few frameworks address the strategies for expressing sympathy to the bereaved.

This study aims to investigate the condolence strategies used by Iranian native speakers. The focus on this speech act is due to the importance of analysing strategies used in social media condolences. While several studies examine condolence strategies for ordinary individuals, few focus on celebrities who are internationally recognized. Social networking sites introduce unique factors, such as formality and anonymity levels. This study analyses social media posts expressing condolences for Abbas Kiarostami’s death to identify the strategies used by Iranians. Abbas Kiarostami, a prominent figure in Iranian cinema, significantly influenced many people and shaped attitudes toward art and cinema. The findings could contribute to understanding how individuals in an Islamic community respond to the death of a non-religious person. Studying Iranian condolence messages on social media provides insights into sociolinguistic strategies for expressing sympathy and support during grief. By analyzing linguistic features, cultural norms, and social dynamics, researchers can understand how people navigate complex social relationships through language. This study also highlights the role of digital platforms in shaping how condolences are communicated and received today. Ultimately, examining condolence messages in the Iranian context can contribute to academic discussions on sociolinguistic strategies, empathy, and interpersonal communication across diverse cultural and linguistic settings.

2 Literature Review

2.1 The Speech Act Theory

The concept of speech act theory is significantly reinforced by its emphasis on the function of language. Function plays a crucial role in defining and describing various aspects of speech acts. As Flowerdew (2012, 79) articulated, speech acts pertain to “the functional, or communicative, value of utterances, with language used to perform actions – actions such as greeting, inviting, offering, ordering, promising, requesting, warning, and so forth.” Austin (1962) delineated three levels in the act of utterance: the “locutionary” act, which is the actual use of language with its components; the “illocutionary” act, which concerns the speaker’s intention; and the “perlocutionary” act, which involves the effect of the utterance on the hearer. These layers highlight that the function of an utterance can have multiple dimensions, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of speech acts. Searle (1976) expanded on Austin’s framework by categorizing speech acts into five types: representatives, directives, commissives, expressives, and declaratives. Mey (2001) provided detailed explanations of these categories:

Representative/assertive speech act: This occurs when the speaker aims to inform others of a view that is either true or false, thereby asserting, describing, explaining, or suggesting something.

Directive speech act: This occurs when the speaker wants the hearer to take a specific action in response to the utterance, such as requesting, ordering, or asking.

Commissive speech act: This occurs when the speaker conveys a decision or plan for the future, indicating that the action will be executed based on the utterance.

Expressive speech act: This occurs when the speaker expresses feelings or psychological states, for example, apologizing, thanking, condoling, or congratulating the hearer.

Declarative speech act: This occurs when the utterance itself brings about an immediate response or action, often involving the speaker’s authority to command or authorize.

2.2 Condolence Speech Act

People offer their condolences to the bereaved in various ways, either verbally or through messages, with social media significantly facilitating the ease of crafting these messages. Zunin and Zunin (2007) emphasized that condolence messages contain hidden values that vary across cultures, situating condolences within the expressive speech act category. According to Searle (1979, 15), “expressive speech acts have the function of expressing the speaker’s psychological attitude specified in the sincerity condition about a state of affairs specified in the propositional content.” Abdul-Majid and Salih (2019) identified two types of condolence speech acts: the first using direct expressions like “sorrow,” “sad,” “peace,” and the second employing indirect speech acts.

2.3 The Study of Grief

The study of death and the way individuals confront it is of paramount importance, as this phenomenon encompasses a wide range of emotions and feelings over an extended period. Research studies have delved into various aspects of grief. Dennis and Kunkel (2004) examined ritualistic communication patterns in orations and eulogies. Pennebaker (2012) focused on the personal aspect of grieving, analyzing how individuals narrate their traumatic experiences to understand their communicative behavior. Rimé et al. (1992; 1998) studied the role of sharing emotions in alleviating sadness among grievers. Consequently, research on bereavement has often centered on ritualistic, personal, and interpersonal aspects. Among these, the study of interpersonal relationships in addressing and supporting grievers has gained prominence due to their role in alleviating pain.

The strategies employed to support grievers are vital and have been the focus of several recent studies. Lehman, Ellard, and Wortman (1986) conducted a study involving individuals who had lost family members, identifying twenty-one helpful supportive strategies. Burleson (2009) compiled a list of grief management strategies and had respondents categorize and rate them based on sensitivity, helpfulness, and effectiveness. Marwit and Carusa (1998) identified 14 strategies used to support grievers, finding that those expressing concern about the deceased were most helpful, while those giving advice were least helpful. Despite these findings, the underlying reasons for the varying helpfulness of these strategies remained unclear. To address this gap, Servaty-Seib and Burleson (2007) designed a study to explore the underlying values of strategies and messages, focusing on the concept of person-centeredness. They found that messages and strategies lacking person-centeredness were less helpful (e.g., “you should let it go” or “take it easy”), whereas those with a high degree of person-centeredness had a positive impact on the bereaved. An example of a highly person-centered message could be, “I am really sorry to hear about your loss; I know you were very close, and I am here to listen to all your pain.” This sentence exemplifies the highest degree of person-centeredness, showing empathy and a willingness to listen.

The study of grief is not limited to overt expressions of agony. As O’Connor (2019) noted, absent grief, characterized by suppression or denial, is one of the least studied concepts. Although these may not be considered strategies to ease pain, they are significant issues in the grief process.

2.3.1 The Role of the Internet in the Grieving Process

Sofka (1997) coined the term Thana-technology to describe the study of the relationship between technology-oriented tools and the grieving process. In this context, computer programs and websites were venues for such activities. Goldschmidt (2013) highlighted the use of social media in the grieving process, emphasizing Facebook as a platform for commemorating events and memorializing the deceased. Social media networks have revolutionized online interactions, enabling people to express their feelings regardless of physical and psychological distances. Carroll and Landry (2010) pointed out that social media networks offer valuable opportunities for those who find traditional ways of expressing sympathy inadequate. However, despite their popularity, social networking sites have their drawbacks. Users may engage in bullying or send distressing content to the bereaved. As Pennington (2013) noted, social media users must be cautious, considering cultural and social aspects and maintaining person-centeredness in their posts. While online communication can be a valuable tool, its effectiveness can be undermined by insensitive or judgmental expressions. Some users may judge the deceased, causing additional pain for the bereaved. Varga and Paulus (2014) also emphasized the role of online environments in providing a safe, judgment-free space. Similarly, Hammond (2015) highlighted the importance of anonymity, although it can be a double-edged sword, offering both protection and potential for harm.

2.3.2 Studies on Condolences

The studies conducted by Williams (2006), Yahya (2010), and Farnia (2011) collectively shed light on the diverse approaches and cultural nuances involved in expressing condolences. Williams’s identification of three major strategies for expressing sympathy, within a framework of linguistic politeness, provides a foundational understanding of the dynamics of condolence communication. Yahya’s exploration of cultural norms and values in Iraq further emphasizes the wide range of semantic formulas used to convey sympathy, underscoring the importance of context and cultural sensitivity in such interactions. Farnia’s study on Iranian condolence messages adds another layer by examining specific strategies employed in response to a notable public figure’s death, showcasing the intricate ways in which individuals navigate expressions of grief within their cultural context. In Farnia’s study, five major strategies were categorized, as follows:

Expressions of condolences: Using specific words or expressions to convey sympathy

Expressions of regret and grief: Employing words to express sorrow or regret upon hearing the news

Praying for God’s mercy and forgiveness: Using phrases to pray for the deceased’s soul

Expressions of positive feelings and compliments about the deceased: Describing the good deeds, character, and legacy of the deceased

Using poems, sayings, and proverbs: Incorporating Persian poems, proverbs and sayings to express condolence (Farnia 2011, 318)

Lotfollahi and Eslami-Rasekh (2011) studied Iranian EFL learners’ performances in expressing condolences, involving 40 male and 40 female students and considering factors such as age, gender, and social status. Their study identified eight categories of strategies used by EFL learners for expressing condolences.

Pishghadam and Moghaddam (2013) compared the responses of English and Iranian native speakers to offering condolences, using movies as the instrument for study. He identified seven categories based on the responses in the movies, concluding that Iranian native speakers exhibited more collectivistic responses, whereas English native speakers were more individualistic (Table 1).

Cross-cultural classification of condolence responses.

| Token of appreciation | Persian Speakers: I’m so sorry. Please accept my sympathy. English Speakers: It’s so nice of you. |

| Expressing sorrow | Persian speakers: I am very sorry about the death of your father. English speakers: I am sorry for your father too. God bless him. |

| Sharing feeling | Persian speakers: God bless your father's soul. I wish he were here. English speakers: I have missed him so much. |

| Comments on the deceased | Persian speakers: He will be in our minds forever. God bless him. English speakers: He was a wonderful man. |

| Topic avoidance | Persian speakers: I came only to express my condolence. English speakers: Why don’t you come in and talk about yourself. |

| Self-blame statement | Persian speakers: I’m sorry to say that she must be dead now. English speakers: It was my fault. I decided not to go after her. |

| Divine comments | Persian speakers: I’m so very sorry for your loss. English speakers: God bless him/her. |

Samavarchi and Allami (2012) compared Iranian EFL learners and English native speakers using 15 Discourse Completion Tasks, given to 10 native English speakers and 50 Iranian EFL learners. The study revealed significant differences between the groups, with Iranian EFL learners using many expressions from Farsi and being more direct in offering condolences.

Al-Shboul and Maros (2013) conducted a study to identify strategies used by Jordanians on the occasion of an actor’s death, analyzing 678 condolence messages from Facebook. They identified seven major strategies: “praying for God’s mercy and forgiveness for the deceased, reciting Quranic verses, enumerating the virtues of the deceased, expressing shock and grief, offering condolences, recognizing death as a natural part of life, and using proverbs and sayings” (Al-Shboul and Maros 2013, 151). Their study also highlighted that most condolence messages in the Jordanian context were closely tied to the religious background of the people.

Studies by Abdul-Majid and Salih (2019) and Minoo, Niayesh, and Rezanejad (2021) focused on the pragmatic competence of EFL learners in expressing condolences. Abdul-Majid and Salih examined Iraqi EFL learners, while Minoo et al. studied Iranian EFL learners. Both studies found that cultural and religious values significantly influenced the strategies used by learners to express condolences. The transfer of L1 knowledge and religious beliefs was evident in the strategies employed. Additionally, these studies highlighted differences between native speakers and EFL learners, with a prominent focus on showing affection among Iranian speakers and learners. Bayo’s study (2021) further emphasized the impact of religious beliefs on condolence expressions, as seen in comments following the death of a political figure in Tanzania.

In the literature review, it is evident that the study of grief has evolved through various forms over time. A significant approach involves analyzing linguistic patterns, revealing hidden values and cultural norms. This study aims to uncover the linguistic strategies embedded within condolence speech acts. Examining several studies across different cultures highlights the similarities in these strategies. Additionally, the role of the internet in the grieving process and its impact on communication have been discussed, providing new insights into understanding and coping with grief.

3 Methods

3.1 Corpus

The corpus for our research study on condolence strategies on social media was meticulously selected through a systematic approach. We utilized various social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram to collect a diverse range of condolence messages. By selecting a wide range of sources and messages from different users, we were able to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the various strategies used to offer condolences on social media. This selection process ensured that our study captured a comprehensive overview of the condolence strategies employed in online interactions. To conduct the current study, 211 samples were collected from Instagram and Facebook. These samples were all condolence messages related to the death of the greatest director in Iran and were directed to the son of the deceased. The sample included messages from people from all walks of life. Since all messages were shown publicly, there was no need to ask for permission from the bereaved. No major factors such as gender, age, social distance, or power were considered to filter the sample. The writers of the condolence messages were mostly fans of the deceased. As the messages were all in Farsi, the nationality and ethnic background of the writers were homogeneous to a great extent. Factors such as age, gender, social distance, and educational background of the writers were excluded from the analysis to avoid filtering the messages. To narrow down the scope of the study, the researcher focused on the sociopragmatic aspects of the messages rather than their pragma-linguistic aspects.

3.2 Coding Scheme

In conducting our qualitative study to explore condolence strategies in social media expressions, coding was an essential method used to systematically analyze and categorize the data collected. Decisions regarding coding were made based on specific criteria such as relevance to the research question, recurring themes or patterns in the data, and the underlying sentiment or emotional tone of the expressions of condolences. Each piece of data, whether a comment, a message, or a post, was carefully examined and categorized according to its content and context. This process allowed us to identify common condolence strategies employed in social media expressions and gain a deeper understanding of how individuals communicate and express condolences in online environments. Several studies were reviewed to provide a classification scheme for the types of strategies used by Iranian native speakers. The classifications of condolences in Al-Shboul and Maros's (2013), Elwood's (2004), Farnia's (2011), Pishghadam and Moghaddam's (2013), Samavarchi and Allami's (2012), and Behnam, Akbari Hamed, and Fatemeh Goharkhani's (2013) studies were regarded as useful blueprints for evaluating the messages. Based on the aforementioned studies and the analysis of the content of the messages, six major categories were identified by the researcher of the current study:

Praising the deceased

Showing sorrow and agony

Poetic expressions

Using emoticons

Praying for his/her peace

Complaining about the current situation

3.3 Data Collection

In the study, social media was used to identify condolence strategies because it allowed researchers to easily connect with and learn from a diverse range of people who have experience with expressing condolences. By engaging with different communities on social media platforms, the researchers were able to gather insights on culturally appropriate ways to offer support and comfort to those who are grieving. Additionally, social media provides a platform for open discussion and shared experiences, enabling researchers to refine and expand their understanding of effective condolence strategies. Data for the present study were collected from the fans of Abbas Kiarostami, renowned for his documentary approach to narrative filming. The researcher collected 211 samples that consisted of original patterns. All these comments were posted on Instagram and Facebook to express condolences, focusing on these platforms due to their popularity and the possibility of anonymity for the writers of the comments. Anonymity on Instagram and Facebook was mainly due to the political atmosphere in the target context. Moreover, these platforms were chosen for their innovative, interactive features and extensive language coverage. The interactive features, such as the ability to like and reply to others’ comments, provided opportunities for interaction both with the bereaved and among the comment writers.

3.4 Data Analysis

The posts sent by fans were collected and translated by the researcher into English. Two experts in translation studies from Allameh Tabataba’i University were recruited to check the translated content. Except for some minor changes, the translated data were deemed suitable for further analysis.

The researcher analyzed the data to ensure the categories adequately covered all types of strategies. This analysis considered results from several related studies in the same context (Al-Shboul and Maros 2013; Elwood 2004; Farnia 2011; Pishghadam and Moghaddam 2013; Samavarchi and Allami 2012). After this analysis, the researcher enlisted two raters to verify the appropriateness of the classification. These independent raters, experts in Applied Linguistics within the Iranian context, collaborated with the researcher to analyze the suitability of the identified strategies. Differences in the coding schemes between the researcher and the two raters were thoroughly analyzed, and the inter-rater reliability confirmed the categories identified by the researcher. Content analysis on raw data was conducted using MAXQDA, a tool that helps researchers easily import various types of data, including social media content, and present major themes. The second stage of the analysis involved determining the frequency of the strategies used by the comment writers, dividing the strategies into major and minor categories.

4 Results

The inter-rater reliability was utilized to validate the categories identified by the researcher, based on previous studies and the analysis of condolence messages provided by commenters on Instagram and Facebook. Six major strategies were evaluated, and the reliability of these categories was assessed by two external raters who are experts in Applied Linguistics (Table 2).

The inter-rater reliability.

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of Agreement | Kappa | 0.855 | 0.045 | 2.449 |

| N of Valid Cases | 6 | |||

Cohen’s κ was calculated to determine the level of agreement between the two raters regarding the strategies extracted by the researcher based on the comments. The analysis indicated a substantial agreement regarding the major and minor strategies, with κ = 0.855, p < 0.05.

In the following section, the major themes extracted by MAXQDA are presented, along with explanations of the primary strategies used by Iranians to express condolences. To provide a clear understanding of these concepts, some examples were translated and rechecked by translation experts to complement the data (Figure 1).

Thematic representation of strategies.

Praising the deceased: The review of comments on Instagram and Facebook regarding Kiarostami’s death after an unsuccessful surgery revealed many instances emphasizing this strategy. Most messages highlighted his professional achievements and contributions, which made him famous. Praising the deceased was also identified as a major strategy in Pishghadam and Moghaddam (2013). Iranians on social media used various methods to express gratitude, often exaggerating the personality and contributions of the deceased. Expressions ranged from formal to informal, often incorporating academic language to show respect and admiration.

Dear Abbas Kiarostami: Yours films were the mirrors of the events and phenomena in the society and your attitude toward life affected me.

Showing sorrow and agony: Many commenters expressed their sadness and stated that Kiarostami’s death was an irreplaceable loss. This strategy focuses on direct expressions of sorrow rather than indirect ones. The manner of expressing sadness varied with the degree of familiarity with Kiarostami and his contributions. Although common phrases were prevalent, some non-religious condolences deviated from conventional expressions. Shock and pain emerged as subcategories of showing sorrow and agony, with initial expressions of shock followed by a deeper emphasis on the pain of the loss.

His absence is unbelievable. He was the world of values for me. I wish this pain could be eased. I cannot describe the pain I tolerate after this shock

Poetic expressions: Reflecting the cultural background of the commenters, numerous poetic expressions were observed. The use of poetry is common in Persian obituaries and condolences, especially on social media. Elements like immortality and the passage of time to alleviate pain were prominent in the poems. New forms of Persian poetry, such as “Azad,” were used, with similes and metaphors being key literary devices.

It is possible to live without others/ It is impossible to live without Abbas Kiarostami

Oh, the mournful heart, calm down/ oh the unknown feeling calm down

Using Emoticons and Emojis: This strategy is technology-oriented, with emoticons being widely used in chatrooms, emails, and social media. Platforms like Instagram and Facebook enable users to utilize various emoticons to express feelings. Emoticons like the ‘black heart,’ symbolizing sadness and death, were sometimes the sole means of expressing condolences, without accompanying text. GIFs, depicting innocence and simplicity, were also used to enhance emotional expression.

Praying for his/her peace: This strategy, deeply rooted in religious and cultural values, involves praying for the deceased’s salvation. Despite the deceased’s lack of a clear religious background, many users avoided direct religious expressions but still conveyed prayers for peace and eternal rest. The belief in eternality and limbo was evident in the expressions used.

May he rest in peace/he will be always with us

Oh, the unique: May your soul rest in peace

Complaining about the current situation: Specific to Kiarostami’s death, commenters criticized the medical care he received, blaming the hospital staff for his death. This strategy is unique to this context and may not apply to other condolence messages. Some users even called for public protests to express their anger and seek accountability.

Dr. Mir is the shame of medical community and empty of honor and humanity.

all should know who is guilty of This nobleman’s death

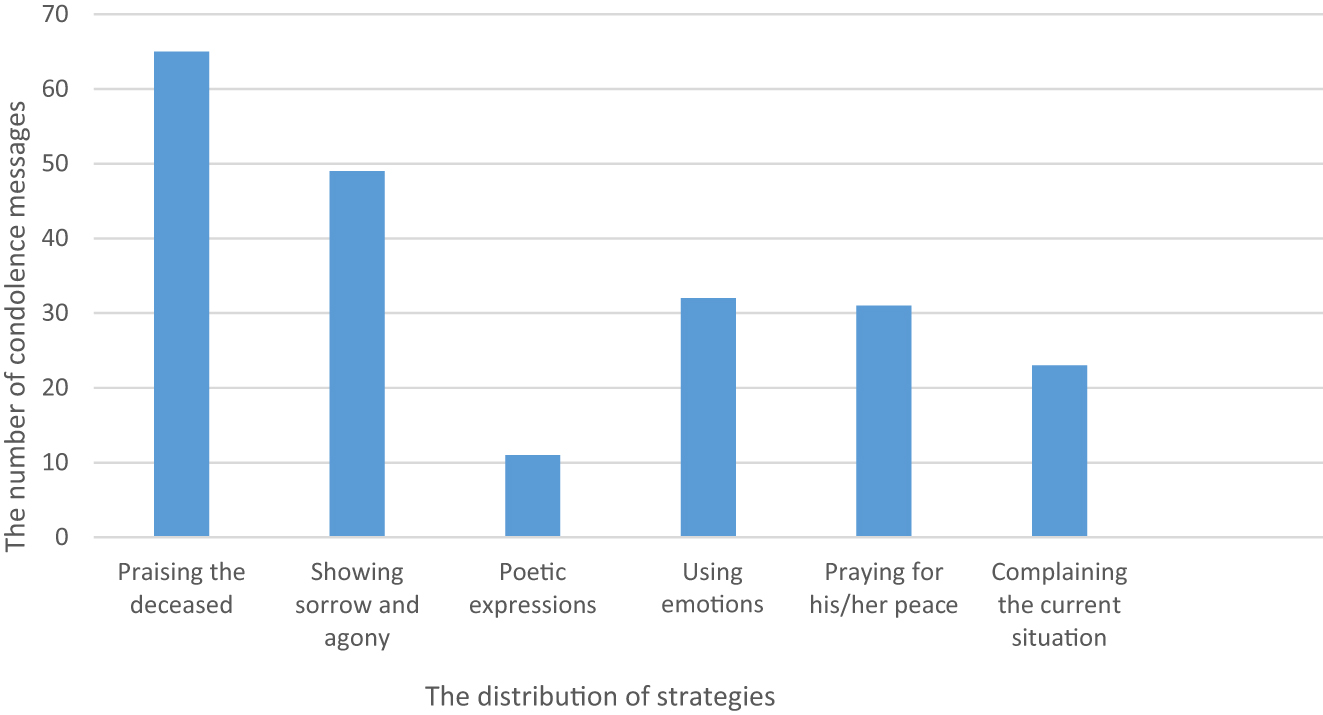

In the following graph, the frequency of the strategies used by the commenters on Instagram and Facebook was shown. In the following part, the frequency of major and minor strategies was explained (Figure 2).

The distribution of strategies.

Praising the deceased was the most frequent strategy (N = 65) among the 211 condolence messages analyzed, while poetic expressions were the least used (N = 11). Despite the widespread use of praise, showing sorrow and sadness was also a prominent strategy (N = 49), making these two the major strategies. The remaining strategies – poetic expressions (N = 11), using emoticons (N = 32), praying for peace (N = 31), and complaining about the current situation (N = 23) – were categorized as minor strategies.

5 Discussion

Investigating condolence messages reveals various forms and meanings underlying their linguistic manifestations. Condolences serve as a vehicle for individuals to express social values during a death event. As Mwihaki (2004) noted, condolence messages emphasize emotive over informative values, aiming to comfort the bereaved in times of distress. This study identifies several strategies, used both consciously and unconsciously, to convey sympathy. These strategies vary across languages and cultures, and the findings illustrate the strategies employed by Iranians in expressing condolences for deceased loved ones. While some strategies align with previous studies, social media introduces new ones absent in face-to-face interactions, highlighting its transformative impact as noted by scholars such as Carroll and Landry (2010), Goldschmidt (2013), Hammond (2015), and Varga and Paulus (2014).

Contrary to Williams (2006), “enquiry for information” was not a significant strategy in this study. Given that the deceased was a well-known figure, the reason for death was common knowledge, rendering such enquiries irrelevant. This study aligns with other Iranian research, such as Farnia’s (2011), where strategies like praising the deceased and using poetic expressions were prominent. However, praying for God’s mercy, a significant theme in Farnia’s research, was less prevalent here, likely due to the non-religious nature of the social media platforms examined – Instagram and Facebook. This divergence indicates a preference among users to avoid religious expressions in their condolences. Similarly, Al-Shboul and Maros (2013) identified “asking for God’s mercy” in Facebook condolences, but this study’s dissimilarity might stem from differing religious contexts. Unlike Pishghadam and Moghaddam's (2013) and Bayo’s (2021) studies, which found religious themes influential, this study observed minimal use of Islamic expressions, possibly due to the deceased’s ambiguous religious stance.

Furthermore, the absence of religious quotes in this study suggests users’ reluctance to use such phrases, despite their prevalence in Iranian culture. Even in funerals, people typically accept Quranic recitations, regardless of personal beliefs. However, in this case, the fans avoided Islamic expressions possibly due to the deceased’s perceived atheism. This aligns with Carroll and Landry (2010) assertion that social media can revolutionize expressions of sympathy, providing a platform for those diverging from traditional norms.

Additionally, while poetic expressions were highlighted in some studies, proverbs, as noted in Farnia’s research, were not observed here. This indicates a preference for direct emotional expression, a trend also noted by Samavarchi and Allami (2012). Despite being a distinct strategy, the relatively low use of poetic expressions suggests their limited appeal in this context. The study of Pishghadam and Moghaddam (2013) identified seven condolence strategies, with only one – commenting on the deceased – overlapping with this study’s findings. The researcher in this study preferred the term ‘praising the deceased’ to capture this concept, emphasizing its non-threatening nature compared to potentially intrusive enquiries about the death or urging the bereaved to move on.

The study classified strategies as major or minor based on their frequency. Praising the deceased and showing sorrow were the most frequent, reflecting their central role in expressing concern. Other strategies, such as poetic expressions and complaints about the current situation, appeared more overused and less person-centered, potentially making them more threatening, as suggested by Servaty-Seib and Burleson (2007). The divergence from Williams’ (2006) findings may relate to the specific context and social status of the deceased. Unlike ordinary individuals, a celebrity’s death disseminates widely, making further enquiries seem inappropriate or insensitive.

Surprisingly, poetic expressions and proverbs, prominent in Al-Shboul and Maros (2013) and Farnia (2011), were among the least used strategies. This may reflect the informal language dominant on social media, fostering intimacy between condolence message senders and receivers. One notable technological feature is the use of emoticons and emojis. Developed in the 1990s, these symbols have become integral to social media lexicon. Iranian fans of Kiarostami extensively used these icons to convey condolences, surpassing traditional strategies like poetic expressions and religious prayers.

Despite some cross-cultural similarities in expressing condolences, Minoo, Niayesh and Rezanejad (2021) suggested that Iranians use distinct patterns, influenced by the cultural significance of poetry. However, religious expressions were minimal in social media posts, contrary to expectations based on Islamic societal norms (Bayo 2021). Social media’s impact on condolence strategies allows individuals to express their thoughts uniquely, reshaping societal norms. Carroll and Landry (2010) highlighted how social media facilitates cross-cultural condolence expressions, fostering understanding and empathy. Concerns about internet etiquette, as noted by Pennington (2013), seem unwarranted as the study showed thoughtful and considerate expressions of sympathy on social media, indicating its potential as a positive tool for connection and support during loss.

6 Conclusion and Implications

This study identified several major strategies used by Iranians to express condolences and highlighted their frequencies. By analyzing these strategies, the study provides significant insights into how individuals in an Islamic community express condolences. This research sheds light on the cultural norms and traditions surrounding grief and mourning, emphasizing the importance of offering support and comfort during difficult times. Understanding these practices is crucial for fostering empathy and effective communication within and across cultures.

A key feature of this study was its focus on written condolence messages shared on social networking sites, which allow users to express their views informally and anonymously. Six strategies were identified by the researcher and evaluated by two external reviewers. The inter-rater reliability results indicated a moderate degree of agreement between the raters, indicating some disagreements on the type and terminology of strategies used. Despite these differences, the study successfully classified the strategies into major and minor categories based on their frequency in the sample, identifying two major and four minor strategies.

One of the most important aspects of this research was the use of two different platforms, Facebook and Instagram, for data collection. Extracting samples from these platforms enabled the researcher to access a more inclusive and diverse sample. Future studies in this field should consider using various platforms to ensure that the data's generalizability. Limiting the study to a single platform might introduce biases specific to that platform rather than capturing a general sense of social media practices.

While this study focused on identifying major and minor strategies, it did not delve deeply into the linguistic aspects of these strategies. Future research could explore both the sociopragmatic and sociolinguistic dimensions of condolence messages. Additionally, future studies could examine the effectiveness of these strategies by assessing the perceptions of the bereaved. Identifying the least effective yet commonly used strategies could provide valuable insights into improving the way condolences are expressed.

The implications of this study extend beyond academic understanding. By illuminating how condolences are communicated in an Islamic context, this research can inform the practices of individuals and organizations aiming to offer appropriate and culturally sensitive support. Social media platforms, as highlighted by Carroll and Landry (2010), can revolutionize expressions of sympathy, allowing for more personalized and thoughtful messages that resonate deeply with recipients. This study underscores the potential of social media to enhance communal bonds and provide meaningful support during times of loss.

References

Abdul-Majid, Mohammed Safwat, and Ahmed Mohammed Salih. 2019. “A Cross-Cultural Study Speech Act of Condolence in English and Arabic.” Journal of Al-Frahids Arts 11 (2): 544–68, https://doi.org/10.51990/2228-011-038-005.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Shboul, Yasser, and Marlyna Maros. 2013. “Condolences Strategies by Jordanians to an Obituary Status Update on Facebook.” GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies 13 (3): 151–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Austin, John Langshaw. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bayo, Phaustini B. 2021. “Analysis of Condolence Response to the Death of Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli on Facebook.” East African Journal of Education and Social sciences 2 (4): 111–8.10.46606/eajess2021v02i04.0134Suche in Google Scholar

Behnam, Biook, Leila Ali Akbari Hamed, and Asli Fatemeh Goharkhani. 2013. “An Investigation of Giving Condolences in English and Persian via Short Messages.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 70: 1679–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.245.Suche in Google Scholar

Burleson, Brant R. 2009. “Understanding the Outcomes of Supportive Communication: A Dual-Process Approach.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26 (1): 21–38.10.1177/0265407509105519Suche in Google Scholar

Carroll, Brian, and Katie Landry. 2010. “Logging on and Letting Out: Using Online Social Networks to Grieve and to Mourn.” Technology & Society 30 (5): 341–49, https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610380006.Suche in Google Scholar

Dennis, Michael Robert, and Adrianne Dennis Kunkel. 2004. “Fallen Heroes, Lifted Hearts: Consolation in Contemporary Presidential Eulogia.” Death Studies 28 (8): 703–31, https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180490483373.Suche in Google Scholar

Elwood, Kate. 2004. “I’m So Sorry: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Expression of Condolence.” The Cultural Review 24 (2): 49–74.Suche in Google Scholar

Farnia, Mariam. 2011. “May God Forgive His Sins: Iranian Strategies in Response to an Obituary Note.” Komunikacija i Kultura Online 2 (2): 315–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Flowerdew, John. 2012. Discourse in English Language Education. London/New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203080870Suche in Google Scholar

Goldschmidt, Karen. 2013. “Thanatechnology: Eternal Digital Life After Death.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 28 (3): 302–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2013.02.021.Suche in Google Scholar

Hammond, Heidi. 2015. “Social Interest, Empathy, and Online Support Groups.” Journal of Individual Psychology 71 (2): 174–84, https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2015.0008.Suche in Google Scholar

Hwayed, Muna Hasseb, and Riyadh Tariq Kadhim Al-Ameedi. 2022. “A Contrastive Analysis Study of Condolences between English and Arabic.” Res Militaris 12 (2): 3823–32.Suche in Google Scholar

Lehman, Darrin R, John H. Ellard, and Camille B. Wortman. 1986. “Social Support for the Bereaved: Recipients’ and Providers’ Perspectives on What Is Helpful.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54 (4): 438–46, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.438.Suche in Google Scholar

Lotfollahi, Bahareh, and Abbass Eslami-Rasekh. 2011. “Speech Act of Condolence in Persian and English.” Studies in Literature and Language 3 (3): 139–45.Suche in Google Scholar

Marwit, Samuel J., and Sarah S. Carusa. 1998. “Communicated Support Following Loss: Examining the Experiences of Parental Death and Parental Divorce in Adolescence.” Death Studies 22 (3): 237–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/074811898201579.Suche in Google Scholar

Mey, Jacob L. 2001. Pragmatics: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Minoo, Alemi, Pazoki Moakhar Niayesh, and Rezanejad, Atefeh. 2021. “A Cross-Cultural Study of Condolence Strategies in a Computer-Mediated Social Network.” Russian Journal of Linguistics 25 (2): 417–42, https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2021-25-2-417-442.Suche in Google Scholar

Mwihaki, Alice. 2004. “Meaning and Use: A Functional View of Semantics and Pragmatics.” Swahili Forum 11 (1): 127–39.Suche in Google Scholar

O’Connor, Mary-Frances. 2019. “Grief: A Brief History of Research on How Body, Mind, and Brain Adapt.” Psychosomatic Medicine 81 (8): 731–38, https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000717.Suche in Google Scholar

Pennebaker, James W. 2012. Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions. New York: Guilford Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Pennington, Natalie. 2013. “You Don’t De-Friend the Dead: An Analysis of Grief Communication by College Students Through Facebook Profiles.” Death Studies 37 (7): 617–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2012.673536.Suche in Google Scholar

Pishghadam, Reza, and Mostafa Morady Moghaddam. 2013. “Investigating Condolence Responses in English and Persian.” International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning 2 (1): 39–47, https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.102.Suche in Google Scholar

Rimé, Bernard, Pierre Philippot, Stefano Boca, and Batja Mesquita. 1992. “Long-Lasting Cognitive and Social Consequences of Emotion: Social Sharing and Rumination.” European Review of Social Psychology 3 (1): 225–58, https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779243000078.Suche in Google Scholar

Rimé, Bernard, Catherine Finkenauer, Olivier Luminet, Emmanuelle Zech, and Pierre Philippot. 1998. “Social Sharing of Emotion: New Evidence and New Questions.” European Review of Social Psychology 9 (1): 145–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779843000072.Suche in Google Scholar

Samavarchi, Laila, and Hamid Allami. 2012. “Giving Condolences by Persian EFL Learners: A Contrastive Sociopragmatic Study.” International Journal of English Linguistics 2 (1): 71–79, https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v2n1p71.Suche in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. 1976. “A Classification of Illocutionary Acts.” Language in Society 5 (1): 1–23.10.1017/S0047404500006837Suche in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. 1979. Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511609213Suche in Google Scholar

Servaty-Seib, Heather L., and Brant R. Burleson. 2007. “Bereaved Adolescents’ Evaluations of the Helpfulness of Support-Intended Statements: Associations with Person Centeredness and Demographic, Personality, and Contextual Factors.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 24 (2): 207–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507075411.Suche in Google Scholar

Sofka, Carla J. 1997. “Social Support ‘Internetworks,’ Caskets for Sale, and More: Thanatology and the Information Superhighway.” Death Studies 21 (6): 553–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/074811897201778.Suche in Google Scholar

Varga, Mary Alice, and Trena M. Paulus. 2014. “Grieving Online: Newcomers’ Constructions of Grief in an Online Support Group.” Death Studies 38 (7): 443–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2013.780112.Suche in Google Scholar

Weaver, Matthew, S., Wendy, G., Kelly Larson, and Lori, Wiener. 2019. “How I Approach Expressing Condolences and Longitudinal Remembering to a Family After the Death of a Child.” Pediatric Blood & Cancer 66 (2): e27489. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27489.Suche in Google Scholar

Wiener, Lori, Abby R. Rosenberg, Wendy G. Lichtenthal, Jennifer Tager, and Matthew S. Weaver. 2018. “Personalized and Yet Standardized: An Informed Approach to the Integration of Bereavement Care in Pediatric Oncology Settings.” Palliative & Supportive Care 16 (6): 706–11, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1478951517001249.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Tracy R. 2006. “Linguistic Politeness in Expressing Condolences: A Case Study.” RASK: International Journal of Languages and Linguistics 23: 45–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Yahya, Ebaa M. 2010. “A Study of Condolences in Iraqi Arabic with Reference to English.” Adab Al-Rafidayn 57: 47–70.Suche in Google Scholar

Zunin, Leonard M., and Hilary S. Zunin. 2007. The Art of Condolence. London: HarperCollins Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Uncertainty Avoidance, News Genres and Framing of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Content Analysis of News from Seven Countries

- Subsistence and Resistance in the Consumption of Counterfeits in South Africa

- Strategies in Expressing Condolences Via Social Networking Sites: The Case of Instagram and Facebook

- Cultural Bias in Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

- Exploring the Role of Social Media on International Students’ Adaptation in the Process of Transcultural Communication Within the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Mediology Study on the Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

- Interview

- Exploring the Intersection of Communication and Labor: A Dialogue with Dan Schiller

- Book Review

- McQuire, Scott, and Wei Sun: Communicative Cities and Urban Space

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Uncertainty Avoidance, News Genres and Framing of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Content Analysis of News from Seven Countries

- Subsistence and Resistance in the Consumption of Counterfeits in South Africa

- Strategies in Expressing Condolences Via Social Networking Sites: The Case of Instagram and Facebook

- Cultural Bias in Large Language Models: A Comprehensive Analysis and Mitigation Strategies

- Exploring the Role of Social Media on International Students’ Adaptation in the Process of Transcultural Communication Within the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative

- A Mediology Study on the Transcultural Communication of Chinese Animation

- Interview

- Exploring the Intersection of Communication and Labor: A Dialogue with Dan Schiller

- Book Review

- McQuire, Scott, and Wei Sun: Communicative Cities and Urban Space