Abstract

This paper describes the principles and applications of a teaching/learning/research method of a “Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy” (VTUP) based on the conditions for prejudice reduction and the principles of Team Learning and Exploratory Practice. The pedagogy was implemented in a Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) project involving Japanese, Malaysian, and Chinese students enrolled in an online graduate seminar course conducted via Zoom at a leading research university in Japan. This seminar aimed to achieve a transcultural understanding of key emic cultural concepts through online interviews and collaborative writing using English as a lingua franca. Reflections on the exchanges that provide evidence for transcultural understanding are presented, thereby supporting the VTUP method. The contributions of the unique teaching/learning/research methodology to transcultural understanding and suggestions for implementing this pedagogy are discussed.

1 Introduction

Virtual contact has become pervasive due to innovations in telecommunication applications (e.g., Zoom) for computers, tablets, and smartphones. In addition, the closure of public institutions during the COVID-19 global pandemic led to an increased reliance on online teaching and distance learning (UNESCO et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022).

The current approaches to intercultural communication teaching generally strongly emphasize the “inter” aspect of communication, underscoring the interaction between distinct cultures. However, it can be challenging to pinpoint precisely which cultures’ participants find themselves between since named languages and cultures may no longer be taken for granted as static entities (Baker & Sangiamchit, 2019). Besides, this can lead to overlooking individual variations within cultural groups and perpetuating biases. The intricate and transformative nature of languages and cultures raises questions about the adequacy of traditional intercultural communication frameworks, which tend to rely on neat distinctions between cultures and languages. In light of this, we propose a novel pedagogy in a Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) project called “Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy” (VTUP), which aims to promote mutual transcultural understanding through online interactions of students, teachers/facilitators from various cultural regions of the world.

The goal of the VTUP is to enrich transcultural understanding. Transculturality rather than interculturality or multiculturality is the focus because transculturality could be considered the most suitable description of the global society in which people live today, characterized by entanglement, intermixing and commonness (Welsch, 1999). Transculturality refers to blending and transcending different cultures on the macro level and creating hybrid identities on the micro level. Indeed, traditional concepts of interculturality and multiculturality based on the assumption of internal differences across cultures are challenged by the notion of transculturality. Scholars have argued that cultural variety emerges from different transcultural identity networks (i.e., identity configurations of elements) rather than differences in monolithic identities provided by single cultures (Skrefsrud, 2021; Welsch, 1999, 2009). This notion discourages conceptions of the self and other cultures as fixed ontological categories. Perhaps Welsch (1999) articulates it best:

Criticism of the traditional conception of single cultures, as well as of the more recent concepts of interculturality and multiculturality can be summarized as follows. If cultures were in fact still – as these concepts suggest – constituted in the form of islands or spheres, then one could neither rid oneself of nor solve the problem of their coexistence and cooperation. However, the description of today’s cultures as islands or spheres is factually incorrect and normatively deceptive. Cultures de facto no longer have the insinuated form of homogeneity and separateness. They have instead assumed a new form, which is to be called transcultural in so far as it passes through classical cultural boundaries. Cultural conditions today are largely characterized by mixes and permeation (p. 197).

This paper presents the VTUP, a framework based on transculturality/transculturation (Epstein, 2009; Zhang & Guo, 2015; Loynes & Gurholt, 2017) and transcultural development (Meyer, 1991; Slimbach, 2005). Transculturality enables us to understand students as having multiple and dynamic cultural identities and their native cultures as evolving processes. Rather than fixed knowledge of “other” cultures, we adopt diverse interpretations of cultural symbols and meanings across boundaries in an online “borderless” setting (Schachtner, 2015).

1.1 Theoretical Foundation of the Pedagogy

The current pedagogy aims for transcultural development through virtual interaction. During a transcultural journey, one needs to suspend prejudicial thinking that is cultivated through childhood socialization, at least long enough for transcultural understanding to happen (Slimbach, 2005). Prejudice reduction refers to the process of actively and intentionally decreasing negative attitudes, stereotypes, and biases towards individuals or groups based on their race, ethnicity, gender, or other social identities. It can be accomplished through intergroup contact under certain conditions (Allport, 1954), and this hypothesis has been tested over the years. Thus, intergroup contact, face-to-face or virtual, is essential for transcultural development.

Slimbach (2005) proposes six competencies for transcultural development that can inform a curriculum: perspective consciousness, ethnographic skill, global awareness, world learning, foreign language proficiency, and affective development. Virtual interaction limits world learning through direct experience and immersion in cultures, but fieldwork does not guarantee deep communication either. It demands learners to reach out to locals, stay for long periods, and establish trust. This entails not only high language proficiency and communication skills but also resilience to communication failures in unfamiliar settings.

For participants who are just starting to engage in intercultural communication, the separation between everyday life scenarios and intercultural communication scenarios can avoid such problems to some extent. Through the assistance and guidance of educators, learners can engage in open and meaningful in-depth communication in a linguistically supported and safe environment, even when communicating online. In-depth communication here is on two levels: one level refers to the richness of information about the cultural experience (e.g., lifestyles, values, etc.), and the other level is the depth of self-disclosure of emotions (e.g., empathy and inquisitiveness), which Slimbach (2005) refers to as affective development (i.e., “the capacity to demonstrate personal qualities and standards’ of the heart”).

To achieve a deeper exchange of both information and emotions, we chose emic cultural concepts as focal points in the pedagogy, assuming they can lead to authentic cultural experiences. These concepts, specific to a particular culture or group and applied to one language or culture at a time (Pike, 1967), are usually related to personal experiences in daily life (see Bruner, 1990), so that participants are more likely to express their emotions when sharing events in their lives, even if they do not share the same experiences. In the case of having the experiences, they are still likely to be emotionally connected and have a greater chance of developing empathy. Our pedagogy incorporates Team Learning (TL: Stewart et al., 2019; Tajino & Tajino, 2000), which promotes a non-hierarchical environment where learners can comfortably share their personal experiences. It ensures equal participation and fosters openness among members, facilitating the formation of friendships.

Another important transcultural competence mentioned in Slimbach (2005) is perspective consciousness, which is “the ability to question constantly the source of one’s cultural assumptions and ethical judgments.” This requires learners to detach themselves from their own culture and view their culture from a relatively objective perspective. Thus, this pedagogy further incorporates the research-practitioner philosophy of Exploratory Practice (Allwright, 2003) by giving participants a new identity beyond cultural insiders or outsiders: “researcher.” With a researcherʼs identity, participants are encouraged to generate and explore puzzles, and any questions about their own culture are allowed.

This section will explain the theoretical foundations in-depth and how the pedagogy can orient learners in a “transcultural journey” in terms of emic cultural concepts, the contact hypothesis, Team Learning (TL), and Exploratory Practice (EP).

1.2 Emic Cultural Concepts

Emic cultural concepts involve the description of behavioural events from the perspective of the actors, using their categories and relationships (Harris, 1976). To create a virtual field for transcultural learning, we choose emic (Pike, 1967) cultural concepts in their original language and translations in other languages as discussion subjects for classroom activities (see Dalsky et al., 2022; Dalsky & Mattig, 2023). Language has been thought of as not only a “cultural activity” but also an “instrument for organizing other cultural domains” (Palmer & Sharifian, 2007, p. 1). Moreover, entire cultural domains are presumed to be organized around emic cultural keywords (Wierzbicka, 1997) that have the potential to unlock significant insights into a particular culture (Dalsky & Su, 2020), thereby increasing transcultural understanding when the concepts are discussed between people of different nationalities.

Our pedagogy involves comparing and contrasting emic cultural concepts across cultures in terms of definitions, functions, cases, and relations (if any) between concepts and expressions. Emic cultural concepts reveal shared meanings across cultures through intercultural contact. Recognizing similarities is the first step to transcultural identity, where the boundary between “self” and “other” is blurred and adaptable – we elaborate on this in the latter part of this paper.

Another benefit of using emic cultural concepts is that it fosters awareness and analytical competencies when interacting with other cultures. A person unfamiliar with the target culture may attempt to understand a concept through the lens of their own culture, often by finding the translation in their first language. However, this may result in “lost in translation” through cultural nuances and background information (see Hamamoto, 2023). Therefore, in our pedagogy, based on the success of our previous work (Su et al., 2021), we encourage students to share their life experiences illustrating the emic concepts, which enriches the definitions and functions of a specific cultural concept with contextual knowledge (e.g., behaviours, reactions, perceptions, and interpretations).

The list of emic cultural concepts used in this project was generated by previous interviews with native residents and psychologists of each community based on their folk psychologies or “commonsense” understandings of them (see Bruner, 1990) featured on a website (https://interculturalwordsensei.org). The students were free to choose the ones they wanted to investigate. The investigation activities included presenting, interviewing, discussing, and collaborative writing related to the concepts. The reason for incorporating intercultural interaction (i.e., students from different cultural backgrounds) and emphasizing cooperation in the design of activities is explained below.

1.3 Contact Hypothesis

Prejudices, provincialism, ethnocentrism, and exclusion are, to some extent, regarded as a part of human nature, and one has to question their biases in the transcultural journey (Slimbach, 2005). Prejudice reduction is considered to be a prerequisite for transcultural competence development and should be taken into account when designing intercultural exchange projects. Since Allport’s (1954) seminal publication of The Nature of Prejudice, the Contact Hypothesis (reformulated by Pettigrew, 1998) has become one of the most prominent theories in social psychology for its effectiveness in reducing prejudice between groups of people with different characteristics. It is essential for participants to engage in intergroup contact to reduce prejudice, and such an authentic experience of engaging in the community rather than only learning knowledge in the traditional classroom is necessary to foster transcultural competence (Slimbach, 2005).

Allport’s (1954) four conditions for prejudice reduction (i.e., equal status, cooperation, common goals, and support by authorities) can guide designing intercultural exchanges. It should be noted that the four conditions should be conceptualized as facilitating rather than essential (Everett, 2013). A meta-analysis (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006) suggests that unstructured contact has the potential to reduce prejudice and a more recent meta-analysis reported that online international contact when cooperation was involved – not the presence of an authority figure or common goals – has a significant impact, positively affecting prejudice reduction (Imperato et al., 2021). Additionally, in another meta-analysis, Pettigrew et al. (2011) found that empathy and reduced anxiety play the most significant role in intergroup contact, which echoes the holistic dimensions of transcultural learning proposed by Jurkova (2021).

Based on the implications of the Contact Hypothesis, we integrate two basic theoretical/pedagogical approaches to foster mutual understanding and prejudice reduction: Team Learning (TL) (Stewart et al., 2019; Tajino & Tajino, 2000; Tajino & Smith, 2015) and Exploratory Practice (EP) (Allwright, 2003; Hanks, 2017, 2019). TL and EP aim to build an equitable, inclusive, and comfortable environment for transcultural learning. In accordance with the principles of TL and EP, we designed activities promoting cooperation and unstructured interaction in intercultural contacts, such as interviewing and collaborative writing.

1.4 Team Learning

In particular, we followed the value-centered version of TL (Tajino & Smith, 2015) by positioning all participants, including the teachers, to collaborate with the core value of learning about emic cultural concepts. Specifically, in this study:

The facilitators (i.e., the American teacher and the teaching assistant from China) learned from each other, regarding English and Mandarin languages and cultural values.

The facilitators also learned emic cultural concepts from the students.

The students were learning from the teacher and the TA as they facilitated the understanding of the academic material presentations and gave brief lectures along the way.

The students were learning from other students from different cultural backgrounds.

1.5 Exploratory Practice

The students were also empowered as “inclusive practitioner researchers” in terms of EP (Hanks, 2017, 2019). This means that the students were responsible for their learning and posing research questions (“puzzles” in the parlance of EP) about the emic concepts. We followed the (EP) principles initially proposed by Allwright (2003) and then updated by Allwright and Hanks (2009, p. 260), namely:

The “ what ” issues

Focus on quality of life as the fundamental issue.

Work to understand it, before thinking about solving problems.

The “ who ” issues

Involve everybody as practitioners developing their own understandings.

Work to bring people together in a common enterprise.

Work cooperatively for mutual development.

The “ how ” issues

Make it a continuous enterprise.

Minimise the burden by integrating the work for understanding into normal pedagogic practice.

A commonality between the principles of TL and EP is the guarantee of equal statuses among students and instructors. All participants cooperate rather than compete, valuing empathy, respect, and support. In such an inclusive environment, the participants can freely speak about their experiences, express feelings, and transform their frame of reference (Dirkx, 2001, 2008; Mezirow, 2012; Taylor, 2009).

Besides equal status, EP prioritizes working for understanding rather than solving (Allwright, 2003; Hanks, 2017, 2019) since solving assumes the existence of a problem, and such an assumption might hinder our understanding. Instead, we adopt the notion of “puzzle” rather than “problem” in the exploration activities. Moreover, the projects implementing the pedagogy should be “a continuous enterprise.” In this case, the project outcomes will serve as references for the next project. For example, students’ reflections will improve the classroom design.

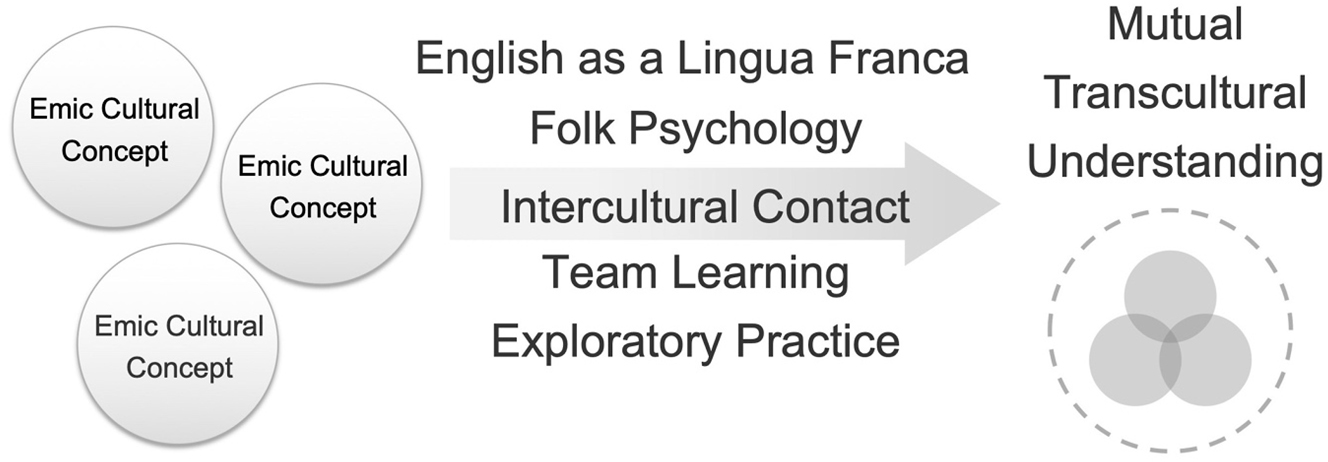

1.6 Research Question

Thus, the process of the VTUP may be conceptualized as depicted in Figure 1. Emic cultural concepts (shown as separate circles) pass through TL, EP, and folk psychology, via intercultural contact using English as a lingua franca. This process results in mutual transcultural understanding, as depicted by the Venn diagram. We set out to explore the process of the VTUP in an authentic intercultural/multilingual setting, in which TL and EP were practiced. The main research question was: What drives the aforementioned process in terms of transcultural communication as an underlying mechanism for mutual transcultural understanding? We set out to answer this question by applying it to an authentic intercultural situation, thereby testing its effectiveness in enhancing transcultural understanding.

Conceptualization of the Virtual Intercultural Understanding Pedagogy.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Seven graduate students (one Japanese female, one Japanese male, one Malaysian female, and four students from China: one male and three females) in a large leading Japanese research university participated in the virtual exchange project. They were enrolled in a graduate seminar course called Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy. The instructor (the first author) was an associate professor of social/cultural psychology from the US. A doctoral student from China (the second author), proficient in English, Mandarin, and Japanese helped facilitate the discussion and the online exchanges as a TA.

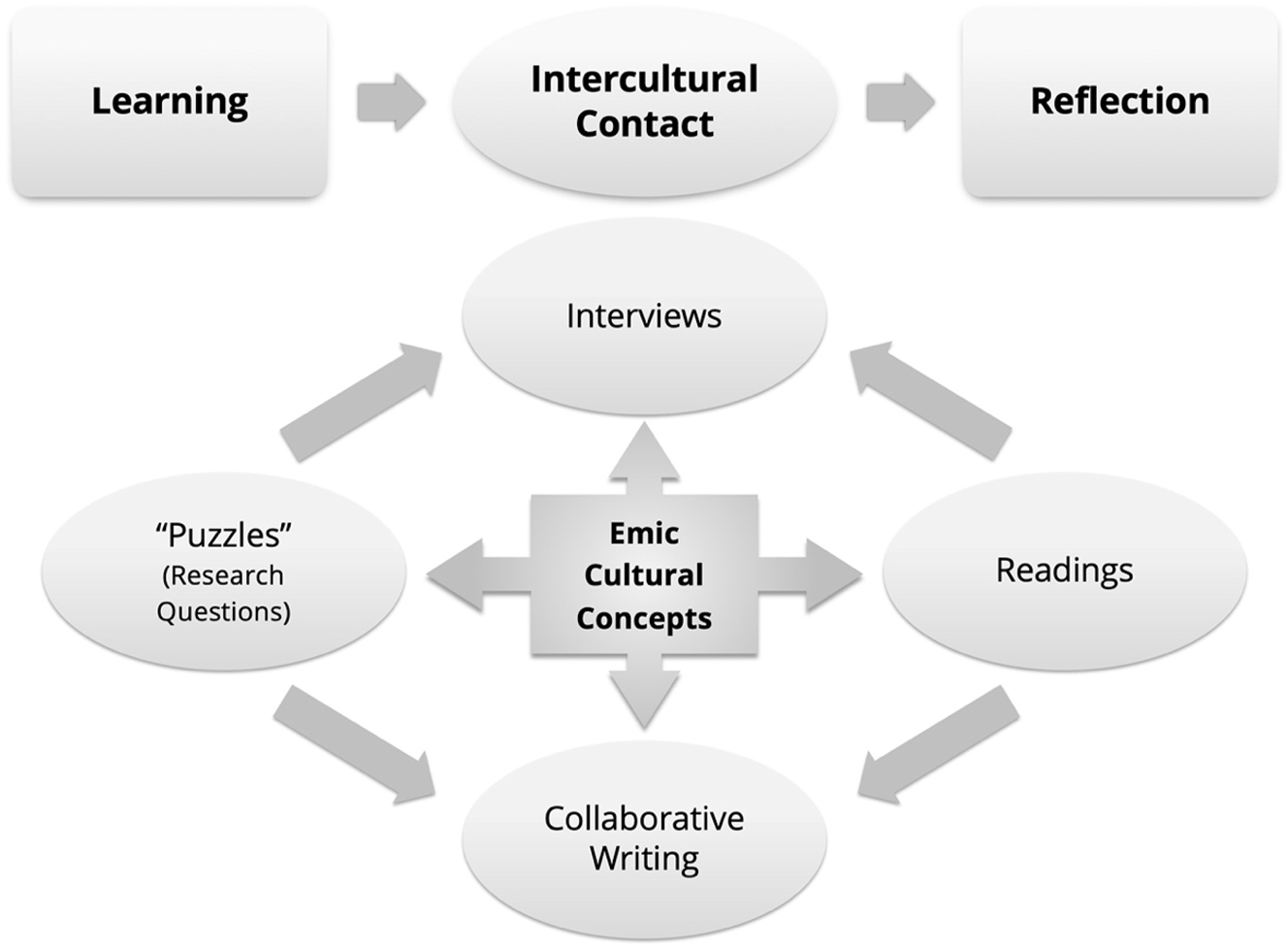

2.2 Procedure

The design of the VTUP follows a path from learning, intercultural contact, and reflection. Readings and research questions (“puzzles”) led to interviews and collaborative writing. The procedure details (depicted in Figure 2) are explained below.

The Virtual Transcultural Understanding method.

Learning. All the class meetings in this project were held on Zoom because of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions at the university. With the facilitation of the instructor and TA, and brief lectures, the students read, presented, and discussed educational materials regarding 1) online intercultural exchange (Lewis & O’Dowd, 2016; Dalsky & Garant, 2016); 2) indigenous and cultural psychology (Kim et al., 2006); 3) cultural linguistics (Sharifian, 2017); and 4) two emic cultural concepts: sajiao in Mandarin (撒娇; “spoiled rotten;” Sundararajan, 2015) and amae in Japanese (甘え; “presumed indulgence;” Niiya et al. 2006; Yamaguchi, 2004).

One student would make a PowerPoint presentation of the material during the 90-minute class period and lead the discussion. The other students who were not presenting were assigned to read the material before each class and type two discussion questions on a shared Google Doc. The instructor and TA facilitated the weekly discussions of the academic materials and gave brief lectures introducing the weekly topics for the first nine weeks of the course.

Intercultural Contact. After the assigned readings, the instructor formed three heterogeneous international teams in Week 9. Two teams were all-female: a triad (one Malaysian and two Chinese) and a dyad (one Japanese and one Chinese). The other team was a male dyad (one Japanese and one Chinese). The teams chose the key emic cultural concepts they wanted to explore, based on the readings, discussions, and personal experiences (i.e., folk psychologies; Bruner, 1990) on Zoom in Weeks 11–12.

In Weeks 13–14, the team members interviewed each other about the cultural equivalence of emic cultural concepts on Zoom (for 90 min. each week). They filled out the worksheet (i.e., Interview Guidelines) on the Google Docs shared by their team. They first did structured interviews by asking existing questions in the Interview Guidelines (see Table 1) based on previous virtual transcultural learning projects (Dalsky et al., 2022; Su et al., 2021) and then did an unstructured interview after a short presentation, where they could ask more specific questions from the process. The instructions for the latter activity were:

Completed interview guidelines (an example of one team).

| Concept 1: Keqi (Chinese) | Concept 2: Enryo (Japanese) |

|---|---|

| 1. Definitions | |

| Q1: How can you translate the concept into English? | |

| A: You are welcome or polite. | A: Do not hesitate (help yourself); Do not put yourself back; Please refrain from ∼. |

| Q2: Do you think the English translation means exactly the same as the concept? Please explain. | |

| A: There are many ways to use it. | A: One English expression cannot cover the all meaning contained in “enryo”. |

| Q3: How would you define the concept in English? | |

| A: It’s made up of a series of actions. Different groups are used to different degrees of the word. | A: An expression showing the behaviour that you prioritize other people or other things than yourself. |

|

|

|

| 2. Cases | |

| The cases could be your own experience or what you’ve heard. They could be interactive/within self, in family/school/company, romantic relationships/friends/acquaintances… And please describe them in detail with who, when, where, what, why, and how. | |

| Q1: Could you give me some examples that can represent the concept? | |

| A: Ritual refusals; symbol of relationship; In-group & out-group; Keqi (Gao & Ting-Toomey, 1998). | A: 1. When your friend’s family invites you for a meal. 2. When you visit your partner with the presence of his/her parents 3. When you have “nomikai” (business drinking party) with your boss and/or senior colleagues. |

| Q2: Which case(s) above cannot represent the concept in your culture? | |

| A: Express reject. | A: Response to compliment. |

| Q3: Do you often use the word in your daily conversation? Please explain. | |

| A: To reply “Thank you.” with “不客气 (bu ke qi; don’t be polite)”. Build relationship quickly with “不用那么客气 (there is no need to be so polite)”. | A: We say “遠慮しないで (enryo shinaide)” to make the person relax and feel comfortable. In formal/business scene: ask people not to do something “ご遠慮ください (goenryo kudasai)”. |

| Q4: Is the word often used on the internet? (In social media for example.) | |

| A: In text messaging. | A: Not often in texting. Mostly said directly to the person when the event is in process. |

| Q5: Does the word often appear in literature/movies/songs…? | |

| A: Conversation in movies/literature/songs (such as 不客气 | A: Conversation in movies, literature. |

| “不客气”, “太客气 (too polite)”). | But in song, it is used to encourage people to pursuit their ambition “遠慮はいらない (no need to hesitate)”. |

|

|

|

| 3. Functions | |

| Q1: What purposes can the concept serve at a micro level (individual)? | |

| A: Separate ingroup & out-group: “insist on observing keqi with an ingroup member to show exclusion”; “not to apply the ritual of keqi with an out-group member to show inclusion”; Being keqi to show oneself as well-mannered. | A: Separate ingroup & out-group. |

| Out-group: More enryo. | |

| Ingroup: Less enryo. | |

| Proper demonstration of enryo = well-mannered. | |

| Q2: What purposes can the concept serve at a macro level (society)? | |

| A: It’s tools to reflect and reinforce relationship; Reflect social status, power, social distance. | A: Same as left. Show politeness: “遠慮しておきます (refusal)”; “ご遠慮ください (ask people not to do it)”. |

|

|

|

| 4. Relations | |

| Q1: Do the two concepts share the same origin? Please explain. | |

| A: Keqi means a humble, pay attention to etiquette. | A: Holding back ourselves; Putting others in priority. |

|

|

|

| 5. Related Expressions | |

| Q1: Does the concept have other forms? (noun/adjective/verb, full expression…) | |

| A: 不客气. | A: (N/A) |

| Q2: Are there any synonyms or antonyms? | |

| A: 不用谢; 见外. | A: 控える; ご遠慮ください=お控えください; 遠慮いたします=控えさせていただきます; 気軽にどうぞ=遠慮しないで. |

Let’s investigate the concepts further!

In this activity, you and your partner will be able to generate more specific puzzles regarding the concepts and have a more comprehensive understanding of the concepts.

Please find academic articles/books and materials (literature, movies, songs, etc.) related to the concept of your culture.

Make a presentation (10–15 min.) based on the academic articles/books and materials to introduce the concept to your partner.

Add the shared link of the presentation slides below on the shared Google Doc.

While listening to your partner’s presentation, please type your puzzles regarding the concept on a Google Doc.

Also, during these weeks, each team was assigned to write a comparison/contrast research paper about the emic cultural concepts collaboratively using Google Docs and communicating via Zoom, following the structure as follows:

Introduction

Concept 1: definition, functions, and cases

Concept 2: definition, functions, and cases

Conclusion

References

Discussion questions

Further investigation of the concepts (an example of one team).

| Investigation of Keq i *P = your puzzle; A = your partner’s answer |

|---|

| P: Self-denial in “keqi” behavior sounded like “kenson” in Japanese. In Japanese, “enryo” and “kenson” are used differently, I think. In Chinese “keqi”, are these concepts are combined together? |

| A: Keqi is not the same as kenson (谦逊). In China, these two words express different degrees of politeness. The level of kenson is higher. It is commonly seen in the communication between younger and older people. |

| Investigation of Enryo *P = your puzzle; A = your partner’s answer |

|---|

| P: Why be enryo to strangers (yosomono), but they will look down on the person? |

| A: For example, when your friend asks you to lend her some money and you don’t really want to, but still you don’t want to hurt her feeling, you use indirect denial such as “I think it is a little difficult for me”. On the other hand, when a stranger comes to you to ask for some money, you don’t usually express enryo. If you say “It’s difficult” in enryo manner, the stranger will not take it as denial, but they will take advantage of you cannot say “no” directly and expect to get money from you if you are kept asked. |

| P: According to some news, the term “遠慮の塊” varies from region to region. In Kanto, for example, they would say “関東のひとつ残し”; in Kyushu, they would say “肥後のいっちょ残し”. Do you think “遠慮” has different names in different places? Is there a unique name for “遠慮” in Kansai? |

| A: I do not know. |

Reflection. During the final class meeting (Week 15), each group delivered a PowerPoint presentation of a draft of their collaborative paper contents, which was submitted by email attachment to the instructor two weeks later. The best papers were eventually posted on a website (https://interculturalwordsensei.org) for public dissemination, with the students’ consent. Students were also given a Reflection Guide via a link on the shared Google Doc, which was to be completed individually and submitted by email to the instructor with the collaborative paper.

2.3 Evaluation of the Pedagogy

Our evaluation will be based on qualitative data collected during student group activities, specifically the interview forms and student reflections. We will examine how students’ attitudes and behaviours evolve throughout the pedagogy to determine if mutual transcultural understanding is achieved and to identify areas that may require refinement.

The interview forms represent a vital resource for evaluating the pedagogy’s effectiveness. They offer a detailed record of students’ active engagement during the exchange. Our analysis will delve into the depth of their questions, the completeness of their responses, and their ability to refine their understanding of emic cultural concepts as they progress through the project.

The reflections submitted by individual students at the end of the project will provide a holistic view of the pedagogy’s impact on their transcultural learning journey. These reflections will be analysed to identify changes in students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours concerning transcultural understanding. We will explore whether students report a more nuanced understanding of cultural differences and similarities, and improved transcultural communication skills. Additionally, we will assess their ability to reflect critically on their own cultural biases and the extent to which they have embraced a transcultural mindset.

3 Results

3.1 Interviews

Each team recorded responses to the Interview Guidelines on Google Docs, which were shared with all the project members. The members of each team asked each other questions and typed in the answers during online exchanges. All of the class participants gave their consent to have the contest of their interviews shared anonymously. Table 1 presents the results of the interviews conducted by one of the teams, in which a Japanese student and a Chinese student investigated the emic cultural concepts of keqi (客气; Mandarin) and enryo (遠慮; Japanese).

After completing the Interview Guidelines, the students were required to investigate the concepts further by asking questions freely. Table 2 presents an example of the findings of the same team (reported in Table 1).

3.2 Reflections

The last activity in the course was for students to complete a Reflection Guide that consisted of open-ended blank spaces for writing comments about 1) overall experience with the project, 2) transcultural understandings related to TL and EP, 3) English skills, 4) research skills, and 5) prejudice reduction. At the end of the Reflection Guide, the students could freely write about how to improve the project. In the following, we share portions of studentsʼ reflections in the open-ended part of the survey that relate to transcultural understandings. The students emailed this Reflection Guide in an MS Word file to the teacher, and all of the students consented to share their reflections anonymously.

The following are reflections from the students related to their responses to items 1–5 in the reflection guide above. We present the most informative answers that relate to prejudice reduction, TL, EP, and transcultural understandings and comment on each response:

I improved transcultural understanding by listening to other students talk about their cultural emic concepts. Moreover, it’s quite fascinating listening to students’ thoughts under similar cultural backgrounds as me, as we had different perspectives on the same issues. That promotes me to think broadly in multiple viewpoints and consider others’ feelings when proposing and arguing. (Chinese student A)

There were two Japanese students in the class this semester, so we could hear different opinions (sometimes related to regional differences) in the discussion, and I think it’s very interesting. The discussion with the Malay student was also very fruitful. I learned about Malay’s values in the assignment topic, we also discussed something more, like nationality, masculinity/femininity, lifestyles, which made me feel that we knew each other better. (Chinese student B)

These students reflected on the “interesting” and “fascinating” exchange, demonstrating that they experienced a fine “quality of life” – the first principle of EP – and aimed for a meaningful and enjoyable experience to bridge the classroom, in and out. The participants with similar backgrounds freely shared their viewpoints, indicating the successful implementation of one of the key principles of TL: mutual learning.

The principles of EP and TL facilitated genuine dialogues in transcultural communication. We contend that this process implies prejudice reduction. The students demonstrated interest in others’ opinions and worked to consider others’ feelings. The reflections interpreted as demonstrating open-mindedness and empathy are necessary qualities for a transculturally competent person (Epstein, 2009; Jurkova, 2021).

Comparing emic cultural concepts requires a deep understanding of both home and other cultures and therefore creates a chance for learning not only different cultures but also their home culture. The mutual development orientation of EP and TL does not assume omniscience of one’s home culture. Thus, the students could admit their cultural knowledge limitations in comfort, an essential affective aspect of transcultural learning (Jurkova, 2021). This was evident from the following students’ reflections:

A comparison of cultures is a lot of fun and I feel understood better about my partner’s culture. Also, the project made me focus on what I have never thought about or not aware of because I had to explain the concept to my classmates. (Japanese student A)

It was interesting to get to know the culture of my country a little better, to find concepts that exist in my country, and to try and find something similar in someone else’s culture. I enjoyed conversations with my team members about their lives and perspectives on certain issues like governance and social behaviour. (Malaysian student)

More student reflections relate to the “mutual development” feature of EP and TL and implications for transcultural understanding:

This project is meaningful and interesting to me. This course taught me some transcultural exchange knowledge, such as what Indigenous psychology is. In particular, through the discussion of “Sajiao” and “Amae” in one class, I realized that the two concepts are quite different. I always thought they meant the same thing. Also, through that course, I realized that the United States had similar Amae behaviours. It made me interested in whether those unique cultural concepts have the same practices in other countries. (Chinese student D)

I learned something new about Japanese culture. For example, through our group’s research, I learned the concept of enryo no katamari. I also realized that amae had negative and positive meanings, somewhat similar to sajiao. Chinese culture and Japanese culture do share many similarities. For example, under the influence of Confucianism, they attach more importance to the collective meaning. (Chinese student D)

Short-term classroom projects cannot afford immediate immersion in other cultures, but investigating emic cultural concepts related to daily life fosters transcultural understandings by providing an opportunity for dense self-disclosure of real-life experiences. Such mutual self-disclosure usually requires intimate familiarity with other cultural community members developed over an extended period. However, by exploring emic concepts with the guidance of TL and EP, the students could recognize cultural nuances. The Chinese student also acknowledged that similarities exist and common humanity is shared across cultures (e.g., “similar amae behaviour also can be found in the United States” with reference to Niiya et al., 2006). These reflection excerpts demonstrate the development of transcultural competencies, as stated in Slimbach (2005).

4 Discussion

4.1 Pedagogical Implications

The experiences of the students in the exchange project shed light on the potential benefits of the Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy. According to the reflections of the students involved, they were able to acknowledge similarities between their own and other cultures, and the differences within other cultures, which indicate transcultural understanding, as the boundaries between self and other became blurred. Though “self” and “other” are inevitable in verbalizing the students’ experiences in reflections, communication initiated by the mindset of transculturality could be constructed through this pedagogy. To be sure, one Malaysian student in the project reflected that “I learned how to communicate transculturally better: communicate in an attitude that respects the other cultures, which means not judging different cultures by your values.” In this sense, communication in intercultural contact is transformed gradually into transcultural communication where neutral attitudes serve as the basis of boundary diminishing. The pedagogy promoted a shift in attitude towards transculturality, likely arising from what could be argued to be critical cultural awareness (Byram, 2012).

Critical cultural awareness is usually considered relevant to intercultural communication paradigms rather than transcultural ones. As discussed in the introduction, a significant conceptual difference between the two involves cultures’ blending and dynamic nature. The paradigm of transcultural understanding proposed and demonstrated in this paper suggests that this critical cultural awareness could be reconceptualized based on the notion of transculturality (e.g., Welsch, 1999). Further applications of the VTUP could pay attention to the possible role of transcultural communication between students from various cultural backgrounds, especially over time, based on research that suggests the other can be included in the self (see Dalsky et al., 2008), as well as in-group members (Tropp & Wright, 2001).

In addition to stimulating self-disclosure, emic cultural concepts catalysed transcultural communication in this pedagogy. Students were able to engage in conversations that transcended surface-level intercultural interactions as the emic cultural concepts are closely related to observable daily experiences and behavioural patterns, which made it easier to discuss and compare. For example, as shown in Table 1, related expressions of keqi (Mandarin) and enryo (Japanese) can both be used to show hospitality and inclusiveness to a guest or someone you want to build a relationship with, which indicates the transcultural aspect of Chinese and Japanese culture. As they explored these concepts, students discovered common threads that linked cultures. This approach allowed them to appreciate both the uniqueness of each culture and the universal aspects of the human experience, contributing to a more holistic view of transculturality.

4.2 Pedagogical Applications

Several issues should be addressed in future applications of the VTUP model. In this project, students could choose the concepts they were interested in; however, some group members confessed to the TA that they were confused about what could be called a “concept” and an “untranslatable word.” Therefore, it is recommended that facilitators discuss this issue in-depth with plenty of examples, learning from each other through TL. One way is to introduce the readings on our website that result from intercultural exchanges (https://interculturalwordsensei.org).

Moreover, some concepts were challenging to investigate because they were too technical; for example, the ones deeply related to philosophy or religion. This would take specialist knowledge on the part of the facilitator, which in this case was limited to psychology. Hence, published academic works on the emic psychological concepts of amae (Japanese) and sajiao (Mandarin) were read, presented, and discussed in the first several weeks of the semester.

Another issue concerns the number of cultural/national backgrounds involved in the group or classroom discussion. In the case study presented here, there were only two (Japanese and Chinese or Malaysian and Chinese). More diversity in cultural/national backgrounds would lead to more opportunities for prejudice reduction, mutual transcultural understandings, and fresh perspectives. However, one should pay attention to the following scenarios. Suppose only one student from a specific cultural/national background is in the class. In that case, she might feel out of place or more responsible and possibly anxious as the sole representative of her nation. Furthermore, as English was used as a lingua franca in the exchanges, varying levels of English competence might also play a significant role in breakdowns in communication unrelated to cultural/national differences, leading to frustration and anxiety.

Finally, the students suggested many ways to improve the VTUP. What follows are some excerpts from the Reflection Guide:

More discussion with classmates from other groups:

I think we can have conversations in groups with different students in each class (not necessarily the assignment) to have a more comprehensive understanding of other cultures. However, since we need to work on the collaborative paper and don’t have much class time to spare, I am unsure whether this proposal is feasible. (Chinese student C)

Online versus in-person and hybrid classroom:

Maybe it is the effect of Zoom lecture, it is better for everyone to speak freely but not turn-taking. Anyway, I prefer taking class in the real classroom, and that makes me feel more relaxed. (Chinese student B)

I felt that there was still something missing from the online discussion. Perhaps the combination of offline and online can help us better understand cultural differences. (Chinese student D).

As shown in the students’ reflections, modes of interaction and collaboration should be carefully designed or adjusted during the process to create a more inclusive and effective transcultural learning environment. It also implies challenges for applying the pedagogy in larger classrooms as students may have different expectations and needs and instructors may find it hard to manage and track each teamʼs process, particularly in an international classroom context. A necessary approach is to incorporate online collaboration platforms for real-time and asynchronous communication and group activities. Another approach to address the difficulties is to enlist teaching assistants proficient in the native languages of the participants as done in this project.

5 Conclusions

This practitioner-research study involved virtual intergroup contact in small, nationally heterogeneous groups. The participants communicated via English as a lingua franca and followed a pedagogical process (Figure 1) to achieve transcultural understanding. The students’ written products and reflections suggest mutual transcultural understanding and prejudice reduction with minimal facilitation by authority figures (i.e., the teacher and TA). Some students benefited more from the project in terms of TL and EP than others, but the evidence revealed some degree of learning or understanding among the students. This marks only our third attempt at such an endeavour with this pedagogy/training method, and our research team is refining the methodological and outcome measures.

It is important to note that this is only an introduction to our attempt at designing and applying a “virtual transcultural understanding pedagogy.” Teachers/partitioners should feel free to alter or tweak the methods to suit their circumstances if they choose to employ them. For example, for an undergraduate classroom with a larger number of students, the teachers/partitioners (and teaching assistants) may have to take the lead more often and add checkpoint reviews to monitor the pace of each team’s progress. The most crucial principle for this pedagogy is to have an open mind that allows for the dynamic and interminable conceptualization of culture as languages and meanings are being negotiated, and therefore critical to reduce prejudice and lead to mutual transcultural understandings. The improvement of the pedagogy could benefit from a more refined observation of the participantsʼ interaction, such as analysing moments of transcultural communication in video recordings of the exchanges. Additionally, assessing the adaptability of this pedagogy to various educational contexts and cultural backgrounds is necessary.

Funding source: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: 20K00773

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.Suche in Google Scholar

Allwright, D. (2003). Exploratory practice: Rethinking practitioner research in language teaching. Language Teaching Research, 71, 113–141. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168803lr118oa Suche in Google Scholar

Allwright, D., & Hanks, J. (2009). The developing language learner: An introduction to exploratory practice. Palgrave Macmillan London.10.1057/9780230233690Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, W., & Sangiamchit, C. (2019). Transcultural communication: Language, communication and culture through English as a lingua franca in a social network community. Language and Intercultural Communication, 19(6), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2019.1606230 Suche in Google Scholar

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Byram, M. (2012). Language awareness and (critical) cultural awareness – relationships, comparisons, and contrasts. Language Awareness, 21(1-2), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2011.639887 Suche in Google Scholar

Dalsky, D., & Garant, M. (2016). A 5,000-mile virtual collaboration of team teaching and team learning. In A. Tajino, T. Stewart & D. Dalsky (Eds.), Team teaching and team learning in the language classroom: Collaboration for innovation in ELT (pp. 164–178). Routledge..10.4324/9781315718507-14Suche in Google Scholar

Dalsky, D., Gohm, C. L., Noguchi, K., & Shiomura, K. (2008). Mutual self-enhancement in Japan and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(2), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107313863 Suche in Google Scholar

Dalsky, D., Harimurti, A., Widiyanto, C., & Su, J. (2022). A Virtual intercultural training method: Exchanges of Javanese, Mandarin Chinese, and Japanese emic concepts. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 25, 121–134.Suche in Google Scholar

Dalsky, D., & Mattig, R. (2023).Intercultural learning about cultural concepts using English as a lingua franca: Online exchanges between German and Japanese University Students. Kyoto University Institute for Liberal Arts and Sciences Bulletin, 6, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.14989/ILAS_6_1 Suche in Google Scholar

Dalsky, D., & Su, J. Y. (2020). Japanese psychology and intercultural training: Presenting wa in a nomological network. In D. Landis & D. Bhawuk (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of intercultural training (4th ed., pp. 584–597). Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108854184.024Suche in Google Scholar

Dirkx, J. M. (2001). The power of feelings: Emotion, imagination, and the construction of meaning in adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(89), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.9 Suche in Google Scholar

Dirkx, J. M. (2008). The meaning and role of emotions in adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2008(120), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.311 Suche in Google Scholar

Epstein, M. (2009). 12. Transculture: A broad way between globalism and multiculturalism. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 68(1), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.2008.00626.x Suche in Google Scholar

Everett, J. A. C. (2013). Intergroup contact theory: Past, present, and future. The Inquisitive Mind. https://www.in-mind.org/article/intergroup-contact-theory-past-present-and-future Suche in Google Scholar

Gao, G., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1998). Communicating effectively with the Chinese. SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781452220659Suche in Google Scholar

Hamamoto, H. (2023). How to obtain translation equivalence of culturally specific concepts in a target language. Translation and Translanguaging in Multilingual Contexts, 9(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1075/ttmc.00099.ham Suche in Google Scholar

Hanks, J. (2017). Exploratory practice in language teaching: Puzzling about principles and practices. Palgrave Macmillan UK.10.1057/978-1-137-45344-0Suche in Google Scholar

Hanks, J. (2019). From research-as-practice to exploratory practice-as-research in language teaching and beyond. Language Teaching, 52(2), 143–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000016 Suche in Google Scholar

Harris, M. (1976). History and significance of the EMIC/ETIC distinction. Annual Review of Anthropology, 5(1), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.05.100176.001553 Suche in Google Scholar

Imperato, C., Schneider, B. H., Caricati, L., Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Mancini, T. (2021). Allport meets internet: A meta-analytical investigation of online intergroup contact and prejudice reduction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 81, 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.01.006 Suche in Google Scholar

Jurkova, S. (2021). Transcultural competence model: An inclusive path for communication and interaction. Journal of Transcultural Communication, 1(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtc-2021-2008 Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, U., Yang, K.-S., & Hwang, K.-K. (2006). Contributions to indigenous and cultural psychology. In U. Kim, K.-S. Yang & K.-K. Hwang (Eds.), Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context (pp. 3–25). Springer.10.1007/0-387-28662-4_1Suche in Google Scholar

Lewis, T., & O’Dowd, R. (2016). Introduction to online intercultural exchange and this volume. In R. O’Dowd & T. Lewis (Eds.), Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice (pp. 17–34). Routledge.10.4324/9781315678931Suche in Google Scholar

Loynes, C., & Gurholt, K. (2017). The journey as a transcultural experience for international students. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1337734 Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, M. (1991). Developing transcultural competence: Case studies of advanced foreign language learners. In D. Buttjes & M. Byram (Eds.), Mediating languages and cultures: Towards an intercultural theory of foreign language education (pp. 136–158). Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781800418189-014Suche in Google Scholar

Mezirow, J. (2012). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In E. W. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), The handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 73–94). John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Niiya, Y., Ellsworth, P. C., & Yamaguchi, S. (2006). Amae in Japan and the United States: An exploration of a “culturally unique” emotion. Emotion, 6(2), 279. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.279 Suche in Google Scholar

Palmer, G. B., & Sharifian, F. (2007). Applied cultural linguistics: An emerging paradigm. In Applied cultural linguistics: Implications for second language learning and intercultural communication (pp. 1–14). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/celcr.7.02palSuche in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, T. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65 Suche in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, T., & Tropp, L. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751 Suche in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, T., Tropp, L., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001 Suche in Google Scholar

Pike, K. L. (1967). Etic and emic standpoints for the description of behaviour. In K. L. Pike (Ed.), Language in relation to a unified theory of the structure of human behaviour (pp. 37–72). De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783111657158.37Suche in Google Scholar

Schachtner, C. (2015). Transculturality in the internet: Culture flows and virtual publics. Current Sociology, 63(2), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114556585 Suche in Google Scholar

Sharifian, F. (2017). Cultural linguistics: Cultural conceptualisations and language. John Benjamins.10.1075/clscc.8Suche in Google Scholar

Skrefsrud, T.-A. (2021). A transcultural approach to cross-cultural studies: Towards an alternative to a national culture model. The Journal of Transcultural Studies, 12(1). Article 1.https://doi.org/10.17885/heiup.jts.2021.1.24153 Suche in Google Scholar

Slimbach, R. (2005). The transcultural journey. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 11, 205–230. https://doi.org/10.36366/frontiers.v11i1.159 Suche in Google Scholar

Stewart, T., Dalsky, D., & Tajino, A. (2019). Team learning potential in TESOL practice. TESOL Journal, 10(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.426 Suche in Google Scholar

Su, J., Aryanata, T., Shih, Y., & Dalsky, D. (2021). English as an international language in practice: Virtual intercultural fieldwork between Balinese and Chinese EFL learners. Changing English, 28(4), 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2021.1915748 Suche in Google Scholar

Sundararajan, L. (2015). Being spoiled rotten (Sajiao 撒嬌): Lessons in gratitude. In L. Sundararajan (Ed.), Understanding emotion in Chinese culture: Thinking through psychology (pp. 125–140). Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-18221-6_8Suche in Google Scholar

Tajino, A., & Smith, C. (2015). Beyond team teaching: An introduction to team learning in language education. In A. Tajino, T. Stewart & D. Dalsky (Eds.), Team teaching and team learning in the language classroom: Collaboration for innovation in ELT (pp. 31–48). Routledge.10.4324/9781315718507Suche in Google Scholar

Tajino, A., & Tajino, Y. (2000). Native and non-native: What can they offer? Lessons from team-teaching in Japan. ELT Journal, 54(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/54.1.3 Suche in Google Scholar

Taylor, E. W. (2009). Fostering transformative learning. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 3–17). Jossey-Bass.Suche in Google Scholar

Tropp, L. R., & Wright, S. C. (2001). Ingroup identification as the inclusion of ingroup in the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(5), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201275007 Suche in Google Scholar

UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, & OECD. (2021). What’s next? Lessons on education recovery: Findings from a survey of ministries of education amid the COVID-19 pandemic. UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/697bc36e-en.pdf 10.1596/36393Suche in Google Scholar

Welsch, W. (1999). Transculturality: The puzzling form of cultures today. In M. Featherstone & S. Lash (Eds.), Spaces of culture: City, nation, world (pp. 195–213). Sage.10.4135/9781446218723.n11Suche in Google Scholar

Welsch, W. (2009). On the acquisition and possession of commonalities. In F. Schulze-Engler & S. Helff (Eds.), Transcultural English studies: Theories, fictions, realities (pp. 1–36). Rodopi.10.1163/9789042028845_002Suche in Google Scholar

Wierzbicka, A. (1997). Understanding cultures through their key words: English, Russian, Polish, German, and Japanese. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195088359.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Yamaguchi, S. (2004). Further clarifications of the concept of amae in relation to dependence and attachment. Human Development, 47(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000075367 Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y., & Guo, Y. (2015). Becoming transnational: Exploring multiple identities of students in a Mandarin–English bilingual programme in Canada. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 13(2), 210–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2014.934071 Suche in Google Scholar

Zhou, M., Dzingirai, C., Hove, K., Chitata, T., & Mugandani, R. (2022). Adoption, use and enhancement of virtual learning during COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 8939–8959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10985-x Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts