Abstract

Guided by the cultural game theory, WGTICC and cultural analysis model, this study has found such game intentions and communication strategies as shaming the invited counterpart versus correcting the host calmly, turning a debate into a Q&A versus using the Q&A as a meaningful presentation, and getting ready to listen versus demonstrating courage, sincerity, and cogency have been adopted during the 3 rounds of debate, thus illustrating and expanding the third assumption in the water and game theory from a win-loss to a win-loss-win result. In terms of cultural roots, Fox Business News, as an example of Western media, has been shifting from objective, accurate, and fair journalism ethics to unilateralism, catalyzed by prioritizing the US interests. In contrast, the Chinese media, like CGTN, have been reshaping themselves for survival and performance employing and developing multiple online platforms while converging with social media.

1 Introduction

According to Ang (2020) from “Mothership,” a Singapore-supported online news agency, the anchor debate between Trish Regan from Fox News Business and Liu Xin from China Global Television Network (CGTN) took place during a full-swing trade war in-between the US and China. To implement its National Security Strategy issued on December 12, 2017, which designated China as a “long-term strategic competitor,” the Trump Administration decided to increase the import duties on goods and services for imports from China to 25 % since January 2018, imposing tariffs worth $50 billion worth from China since March 22, and continued with 3 more rounds of tariffs worth $250 billion. In response, China gave tit for tat by levying tariffs on US goods worth $50 billion first and then $110 billion (Bown & Kolb, 2021). The US–China trade war was going on non-stop though both sides suffered a reduction of 0.6 and 0.9 % in their respective GDP (International Monetary Fund, 2018, p. xvi).

Since the dust is down, scholars (e.g., Kissinger, 2011; Nye, 2015; Overhaus et al., 2020; Zaidi & Saud, 2020) began making serious reflections by contributing fruitful achievements concerning the US–China issues from politics, diplomacy, economics, trade war, and international relations, etc. Nevertheless, there have been few studies on US–China relations regarding the recurrent trade war as reflected in mass media by examining the Chinese flexible communication strategies in correspondence with various US game intentions while exploring the cultural roots herein. To fill this void, the present paper looks into the cultural roots of the communication strategies and gaming intentions in an unprecedented US–China TV anchor debate through the theoretical lenses of the cultural game theory, water and game theory for intercultural communication (WGTICC), and the cultural analysis model. Below are our two research questions (RQ):

RQ1:

What are the gaming intentions and communication strategies that illustrate the relevant assumptions in WGTICC?

RQ2:

What are the cultural roots for the adopted gaming intentions and communication strategies in the US–China TV anchor debate case?

The rationale of the present study is twofold: first, the research findings may inject insight to the relevant readers in their reflections upon the unprecedented, epoch-making, and far-reaching intercultural phenomenon of the Internet debate, admire the bravery of the two TV anchors, and cherish the once-in-a-hundred-year press heritage of holding a lively online debate for the benefits of the general public while putting their future at risk. Second, the findings may also shed light on seeking solutions to the increasingly intense US–China conflicts in both mass media and the overall US–China bilateral relations, which involve the stake of all.

2 Literature Review

For the present paper, our review of the literature covers the following two aspects:

2.1 Media Features in the West and China

Western media mean the mainstream media in the highly industrialized, Euro-American countries. This paper focuses on mass media, which refer to channels, media, utilities, devices, or instruments used in the mass communication process (Wahab et al. 2017). Mass media have already experienced the printed, electronic, and cyber stages with the developmental trajectory of the mainstream media merging with the new or social media. For quite some time, it is the Western media that predominate the international milieu of the mass media. Since the U.S. overtook Britain in the 1870s and began taking the lead in the world economy, it is now “facing an economic rival that is as large, and by some measures, larger than it is,” because “China has already surpassed the United States to become the biggest economy in the world based on purchasing power parity” (Allison et al., 2022, p. 2). Moreover, as of June 2023, among the 5.18 billion global Internet users, or 64.6 % of the world population, 4.8 billion, or 59.9 % of the people in the world, were social media prosumers. Specifically, China has already become the world leading market in terms of the number of Internet users, followed by India and the US (Petrosyan, 2023, para. 2). Thus, we can see the dramatically decreasing gaps between the US and China in terms of both overall economic volume and the media hardware or infrastructure.

However, the Western media are still superior in that, first, they generate the majority of the news content which then flows to non-Western countries. Even if periphery locations may also produce some eye-catching news items, they can hardly bring about substantial changes. Second, in the liberal system with the US and Britain as leaders, “the global media system shows a trend of homogenization, and the ‘autonomy’ of the media is widely regarded as the cornerstone of political democracy and the legitimacy of journalism” (Ji, 2021, p. 2). Finally, the discourse power of international public opinions is mostly dominated by the institutionalized media institutions originating from Western countries and delivering to the world market. Nonetheless, some changes are arousing concerns and raising alarms. Spencer (2022) noticed that as social media continues to grow, China’s 650 million Internet users are enjoying their social platforms and networks, “boasting user bases exceeding half a billion accounts” (para. 1).

Huang and McAdams (2000) noted that China and other non-Western countries have been reported in apparently biased, negative, and crisis-filled styles by some Western reporters who may oversee their professional standards. They are likely to dramatize problems and overplay controversy in non-Western countries to catch readers’ eye with headline-making news. It is found that certain Western media tend to discriminate against developing countries while prioritizing Western supremacism. Western media’s overall focus on wars, conflicts, and catastrophes in developing countries has been psychologically detrimental to the image of these countries. Regardless of its dramatic changes in all social sectors, China has been represented in Western media as the “other” vis-à-vis “us” based on ideological differences and conventional stereotypes (Zhang, 2018).

As time goes by, due to political, economic, and technological factors, the US press has to face the challenges of “embracing the roles of reporting things as they are, educating the audience, and providing information for decision-making at various levels” (Vos & Craft, 2017, p. 2). Consequently, more and more US press began using online search engines for information and relying on social media to promote their work. This means that the conventionally institutionalized Fourth Estate has been affected by the social trends shifting from multilateralism to unilateralism and from globalization back to isolation. This is why Tanaka (2019) sharply claimed that “the US currently has no binding narrative to anchor it in time and place” (para. 9). Thus, it is easy to understand why war journalism got the upper hand in the US, which tends to flare up the conflict by concentrating on crime and violence while taking sides of the elites and facilitating the governments to “achieve a ‘victory’ for the home country” (Ha et al., 2020, p. 1).

As for the Chinese media, for thousands of years, influenced by the Confucian beliefs that “a just cause should be undertaken for the commonwealth” or for “the harmony, unity and shared community for states” (Zengzi, 2006–2023), the Chinese culture has put priority on the common interests of the community over the unrestrained rights of the individual. Meanwhile, it has become the national initiative of present-day China to seek mutual benefits in a shared community via its “One Belt, One Road” initiative rather than striving for one’s national interests at any cost.

[Post online publication correction added 11 April 2025: the citation (Brady, 2015) was removed.]

As a result, peace journalism has become prevalent in China, which emphasizes the representation all sides, “exposing the lies and untruths, with a focus on peace and benefits for the common people” (Ha et al., 2020, p. 1). Thus, it is ironic that the traditional media roles of the Fourth Estate in the West and the governmental mouthpiece in China seem to be exchanging places.

2.2 The Cultural Roots of the US–China Conflicts

Katz and McNulty (1994) defined conflict as a negative situation involving at least two interdependent parties due to “perceived differences” (p. 1). Upon coming to office in 2001, the Bush administration began treating China as a “military competitor with a formidable resource base” (Yuan, 2003, p. 39). Therefore, containment of China has been adopted “as an alternative to engagement” (Layne & Thayer, 2007, p. 72), by making it its manifest destiny to protect American interests “regardless of overriding international concerns, and to maintain world stability even if it has to go against international consensus” (Snow, 2007, p. 42). The very nature of the Bush Doctrine requires that the US “act in ways that others cannot and must not,” which is “not a double standard, but what the world order requires” (Jervis, 2003, p. 376). To follow up, the Trump Administration began treating China as a “long-term strategic competitor” as part of its National Security Strategy issued on December 12, 2017, to “make America great again” and the Biden Administration followed suit by emphasizing the rules-based international order, the US–China conflicts have become multi-dimensional—from trade to “security-related, economic, technological and ideological dimensions” (Perthes, 2020, pp. 5–6). To China, President Trump’s call to “make America great again” runs contrary to China’s call to seek win-win results in its bilateral and multi-lateral relations. Meanwhile, the “rules” as uttered by the US politicians and mainstream media refer to the US-established rules instead of those under the UN Charter. Thus, no matter who is the president of the US, it is the American strategic objective to maintain its supremacy and to be on guard against any threats from both allies and potential rivals in the globalized world (Amin, 2006, p. 10).

Researchers (e.g., Chu, 2011; Geftner, 2008; Jia & Ji, 2018; Shi, 2012) found that it is characteristic of the Western culture to inherit individualism and adventurous spirit from the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. First, while pursuing equality, freedom, science, and reason based on individualism and pragmatism, Westerners tend to impose their preferences on other nations and cultures with the assumption that language is meant for personal goals. Second, due to the influence of Descartes’ dualism, people in the West try to locate a mechanical causal relationship between two variables. Finally, due to the impacts of Derrida’s postmodernism and Saussure’s structuralism, Western scholars hold the belief that a language is the carrier of meaning, thus laying more emphasis on the form and content of language while neglecting the roles of language users and the context.

In contrast, developed from mainly an agricultural civilization, China since ancient times has nurtured a culture of sharing and good neighborly relationships. This is why China’s four ancient inventions of paper, printing, compass, and powder have been circulated worldwide throughout human history for so long and for free with few people from the Western world appreciatively associating them with intellectual property. To prevent invasions from outsiders, China has completed the construction of the Great Wall from generation to generation. To display its national power, Zheng He’s ocean-going voyages (1405–1433) occurred 7 times with a crew member of over 20,000 for each voyage without colonizing an inch of foreign land.

Today, China is engaged in implementing its dream of economic prosperity, national renewal, and people’s well-being as a grand pursuit. To this end, China has been associating the Chinese Dream with the American Dream by establishing a new type of bilateral relationship of “no conflict and no confrontation” between China and the US (Economy, 2021, p. 1). Nonetheless, to the US side, China has become a regional power in the Indo-Pacific region by prioritizing its economic, security, technological, and political preferences. Determined to confront China as a strategic competitor in a long-term, life-and-death game, the US has been engaged in a series of wars in trade, human rights, intellectual property rights, territorial disputes, and defense of its world supremacy.

In terms of the roots, the traditional culture of China is featuring a combination of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism by seeking balance and unity between heaven and man. Externally, it seeks a peaceful and harmonious relationship between mankind and nature. Internally, it pursues self-improvement through “cultivating one’s own character, regulating the family, ruling the state, and bringing peace to the whole world” (Zengzi, 2006–2023, para. 2). Meanwhile, it is characteristic of the contemporary Chinese culture to adopt Marxism, Leninism, and socialism with Chinese characteristics at the core, maintain the Chinese ways of life as they are and bring Western science and technology into full swing for practical advancements (Jia & Ji, 2018). Clearly, present-day China is practicing Chinese-style modernization, with its “Belt and Road” initiative since 2013. Insightfully, Jacques (2019) remarked that China’s successful transformation results from its earnest learning and creative absorption from both the West and its Asian neighbors by exploring its native sources so dynamically that the West needs to learn from the East” (p. 394).

As a result, Chinese interactions tend to be forbearing, flexible, and leisurely in order to establish and maintain harmony through morality. Regarding the US–China conflicts, no matter whether it is a specific trade war or the possible war between an established power and a rising one, negotiations on equal footing and collaboration for mutual benefits may be the only and ultimate alternatives. Just as Mahbubani (2021) remarked, so long as the decision-makers prioritize the genuine happiness of their respective peoples as the top agenda, even “opposing forces between the US and China may also coexist peacefully” (p. 19).

3 Theoretical Frameworks

In the study, the cultural game theory, WGTICC, and cultural analysis model have been applied to understand the nature of the game conflict between the US and China, identify the game intentions and corresponding communication strategies, and explore the cultural roots for the adopted intentions and strategies.

3.1 The Cultural Game Theory

A game is an activity of making choices to achieve equilibrium for maximum benefit (Chu, 2011). A game theory refers to “a study on the rational behaviors of rational participants and their realization of participation equilibrium when the behaviors of multiple participants interact with each other in the case of risk uncertainty” (Wang, 2005, p. 101). In other words, a game theory concerns two or more than two parties aiming at their respective maximum gains based on full awareness of the rivals in the contexts of competition, cooperation, and conflicts. It is Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern who are two American mathematicians that increased the number of the game participants from two to more than two, extended game as a formal discipline and, ultimately applied a systematic game theory into the field of economics. With further contributions by John Forbes Nash, Jr., John Harsanyi, Reinhard Seltern and James Morris, etc., the game theory became increasingly popular in politics, economics, management, military affairs and cultural studies.

According to Wang (2005), a cultural game means the “symbiosis between communication and collision, dialogue and confrontation that emerges in cultural exchanges” (p. 101). Gong and Zhao (2015) applied the cultural game theory in cultural security between China and the Western world. Based on their research findings, the two scholars have identified three features in the games between China and Western countries: first, the game participants are personified sovereign states; second, the games may start before the players completely understand each other in terms of their characteristics, strategy space or expected benefits; and, finally, the participating countries usually have no intention to cooperate and just make decisions based on their interests. The game characteristics will facilitate the clarification of the participants, types or nature, and possible results of the games.

3.2 WGTICC

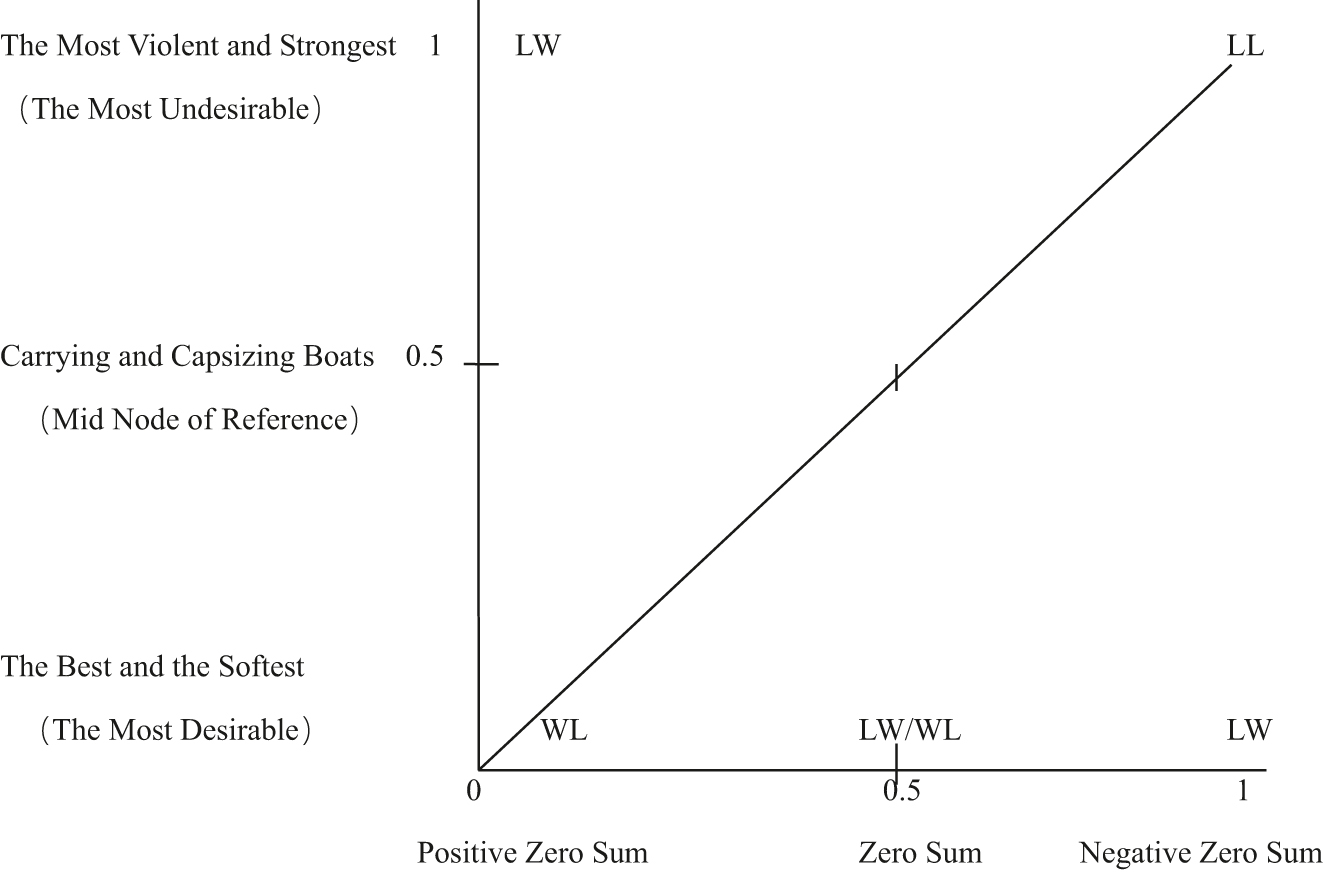

Tian’s (2021) WGTICC deals with making choices of communication strategies between the range of the “best and the softest” through “carrying boats and capsizing boats” and “the most violent and the strongest.” The choices are made in correspondence with the positive zero-sum, zero-sum, and negative zero-sum game intentions in the case of cooperative or non-cooperative, static or dynamic, or conventional or unconventional situations. The applicability of the theory lies in the fact that water image metaphors “convey a significant Chinese philosophical proposition and political doctrine, which functions as the primary source of understanding modern Chinese ideas” (Chen & Holt, 2002, p. 155).

To demonstrate the dual functions of the theory of adopting the best possible communication strategies and achieving optimal game results, a diagram has been constructed as can be seen in Figure 1. Along the vertical line, the nodes from “the best and the softest” through “carrying boats and capsizing boats” to “the most violent and the strongest” communication strategies are marked from the bottom (0) to the top (1). First, the most desirable and most undesirable are two relative and dynamic concepts rather than absolute and static concepts. Second, between the most desirable and the most undesirable or the range between 0 and 1, there are countless choices of communication strategies, and the final decision on a certain point along this continuum is determined by the rival player’s flexible intentions. Finally, the midpoint on the vertical axis is a point of reference, with the choices above it likely to move toward the “most undesirable” while those below towards the “most desirable”. This means that this mid-point itself does not participate in the representation of the hypothetical relationship between the two axes.

WGTICC (after Tian, 2021, p. 679).

At the same time, this theory uses the game as an analogy, indicating that, in general, the three options of the positive zero sum (win-win, WW), zero-sum (win-lose, WL) and negative zero sum (lose-lose, LL) are in correspondence with the most favorable to the most unfavorable outcomes along the horizontal line. Usually, each player is expected to achieve either a win-win or a win-lose outcome. However, on some occasions, a player may purposely choose the zero-sum or even negative zero-sum outcome. Thus, the decision to adopt which communication strategy within the range must be flexible and creative.

Specifically, WGTICC contains 6 assumptions, the third of which reads:

(3) If the rival player shows a clear zero-sum intention, and the host player makes decisions likely to move towards the best and the softest communication strategy, then the game is likely to end with a winning host and a losing rival (Tian, 2021, p. 679).

In the above figure, WW stands for win-win, LL lose-lose, WL win-lose and LW lose-win. Since the present study discusses the complicated games with unexpected outcomes between China and the US, all kinds of game intentions and corresponding communication strategies are possible, which are, fortunately, within the overall structure of the theory.

3.3 The Cultural Analysis Model

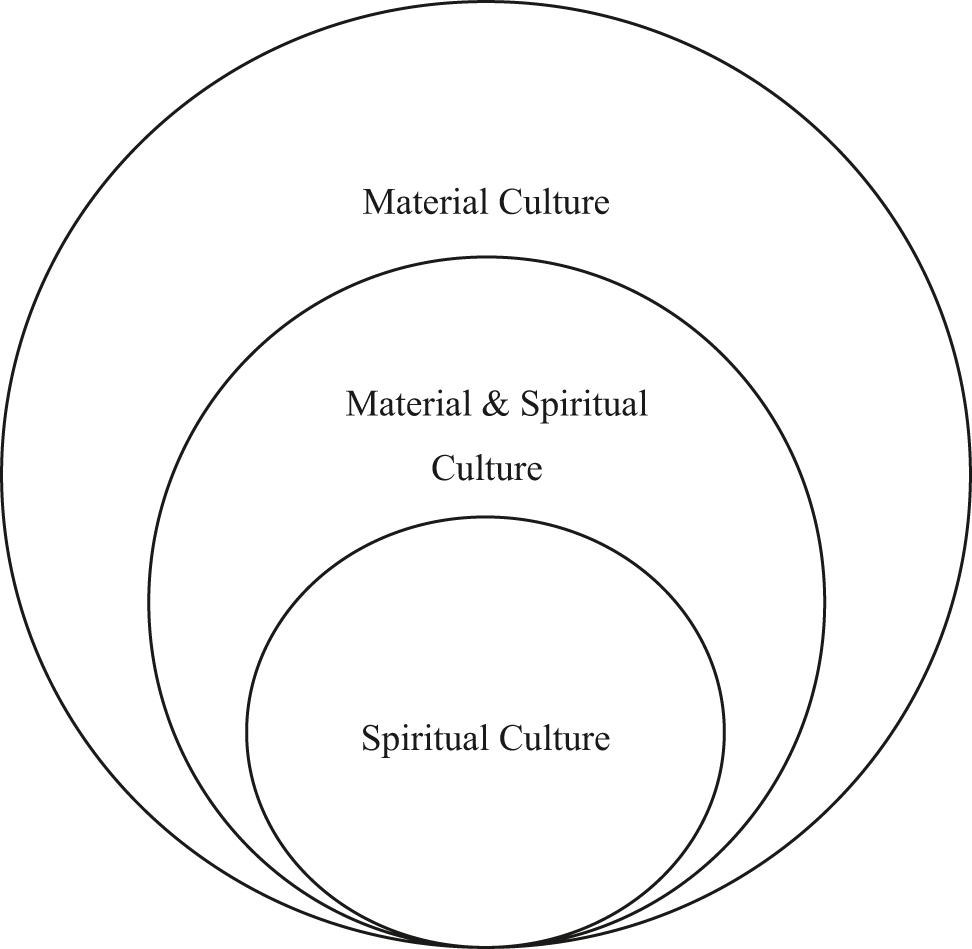

Culture is defined as “a description of a particular way of life,” which convey the meanings and values in art, learning, institutions and ordinary behaviors (Williams, 1961, p. 43). Culture is also defined as “the total way of life and all the objects created to meet the needs of the way of life,” which comprises the “material level of processed nature or products of human labor, institutional level of scientific assumptions, political organizations, and social systems, and the conceptual level of value systems, thinking patterns, and national character” (Pang, 1986, p. 84). Combining the two scholars’ definitions of culture, we operationalize our understanding of culture as a total way of life, with all the cultural elements categorized at the material, institutional, and conceptual levels (see Figure 2).

A cultural analysis model (after Williams, 1961; Pang, 1986).

It was in 1934 that Ruth Benedict, an anthropologist, first proposed the concept of cultural pattern, which she defined as “a whole of thought and behavior with internal consistency and interrelated parts” (p. 48). Since all cultures have their unique characteristics, there are quite several cultural patterns. As for which cultural pattern to apply, it depends on the specific nature of the cross-cultural game and the dynamic situation the gaming participants find themselves in. The cultural analysis model described above can help explore the cultural roots for the adopted gaming intentions and communication strategies at the material, institutional, and conceptual levels. As Huntington (1996) noted, in the global politics today, “alignments defined by ideology and superpower relations” are gradually replaced by those “defined by culture and civilization” (p. 125). Thus, the three theories have been integrated into the theoretical frameworks that guide this study.

4 Research Methods

This paper has adopted the research method of case study for both data collection and data analysis. A case study can be defined as “the exploration of an individual, group, or phenomenon” (Sturman, 1997, p. 61). In a case study, one or more cases can be investigated either qualitatively, quantitatively, or in a mixed manner depending on the availability of the cases and purposes of the research. In this paper, we adopted the qualitative case study within the interpretive research paradigm, featuring a type of subjective understanding of the world with explanations from the perspective of the participant (Ponelis, 2015, p. 538) by “making an in-depth exploration” of our chosen case in “real-life contexts” (Zainal, 2007, p. 3).

Rowley (2002) noted that a properly designed case study comprises the following 5 major components. The first is the study’s research questions, which should be of general interest and which can be explored in the context of the proposed case study. In this paper, we raised three research questions concerning the identities and roles of the gaming participants, the gaming intentions and communication strategies, and the relevant cultural roots. The second concerns the study’s propositions, which are the researchers’ speculations or expectations of the research findings based on the literature review and other personal experiences and knowledge. In the present paper, apart from the six propositions in the adopted water and game theory for ICC, we proposed that, based on the nature of the US–China games, both the game intentions and communication strategies were culturally bound.

The third component is the study’s unit of analysis, which is formed by a person, an organization, or an event, and which determines the formulation of the research questions and collection of evidence. In this paper, we selected the TV anchor debate between Trish Regan and Liu Xin, so the two TV anchors and the back-and-forth interactions during the three rounds of their debate became the units of analysis. The fourth refers to the logical link between the data and the propositions, with the case selection based on the criterion of relevance so that the selected case is information-rich or “interesting, unusual, and striking” (Thomas, 2011, p. 514). The TV anchor debate was the first-ever live debate between two nationally-famous hosts respectively from Fox Business News and CGTN English News. The event caused a worldwide sensation and global attention from all walks of life, thus meeting the above standards as set by Thomas.

The fifth or last component is the process for analyzing and interpreting the collected data involving 6 specific steps according to Creswell (2009). The first step is to organize and prepare the data for analysis. With a thorough online observation and extensive search in the existing literature, we have collected our first-hand data including the 15-min Fox News video clip of the debate, the CGTN transcript, behind-the-scene interviews, personal writings of the two debaters, and relevant posts and comments of viewers and scholars. The second step is to read through the data, which the two authors did independently to get an overall understanding of the general information in the data. The third step is to make a detailed analysis of the data with a coding plan. Each of the two authors categorized and coded the data into meaningful levels of segments with labels aided by the qualitative data analysis software Nvivo. The fourth step is to continue with the coding process until patterned themes emerge, and the fifth step is to finalize and narrate the patterned themes. We compared and checked our patterned themes and narrations with each other by the theoretical framework as well as the reviewed literature to get ready for the last step of meaningful and insightful interpretations.

5 Findings and Discussion

For this research, we raised two RQs: RQ1: What are the gaming intentions and communication strategies that illustrate the relevant assumptions in WGTICC? RQ2: What are the cultural roots for the adopted gaming intentions and communication strategies in the US–China TV anchor debate case? Below are the research findings in terms of the answers to the two RQs with necessary comments based on the theoretical frameworks.

5.1 Gaming Intentions and Communication Strategies

To identify the involved game intentions and communication strategies and analyze them as illustrations of the relevant assumptions in WGTICC, we categorize the TV anchor debate between Trish Regan and Liu Xin into the following three rounds.

5.1.1 Round 1: Shaming the Invited Counterpart Versus Correcting the Host Calmly

Although both were nationally famous TV program hosts, Liu Xin from CGTN of P.R. China was invited to the “Trish Regan Primetime” show by the Fox Business News host Trish Regan as a rival instead of a guest. In brief, Regan felt that she had been provoked and attacked, so she decided to revenge her attacker face to face. Assuming that Liu Xin was unable to present her image, let alone the image of China, in real person to the audience of the US and the rest of the world. Regan began the debate by saying:

Tonight, I have a special guest joining me all the way from Beijing, China to discuss the challenges of trade between the U.S. and her home country. She’s the host of a primetime English-language television program overseen by the Communist Party of China. (CGTN, 2019a)

When arranging the debate via Twitter earlier, Regan told Liu to name a time and place, and she promised that she would just “sling FACTS” (Regan @trish_regan, May 24, 2019). Then, she continued clarifying that she only speaks for herself while emphasizing that her guest is a CPC member. She did so either out of her inertia of categorizing people like Liu as members of CPC or on purpose to label Liu Xin as a Red Guard of China to alienate a group of audience from Liu Xin and CGTN” because their Cold War mentality had been aroused (Shi & Dai, 2020, paras. 25–26). Regan’s successful shot led to two-thirds of the subsequent tweets frequently tangling with one another in the core issues related to CPC (para. 25) though the debate was originally meant to “discuss US–China challenges” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 1).

In response to Regan’s opening remarks, Liu corrected Regan by saying she is not a CPC member, which is on the record. She emphasized that she was just speaking for myself while Liu Xin was representing CGTN (CGTN, 2019a, para. 6). Besides, Regan was informed that her accusation of China for annually stealing about $600 billion IP from the US is inaccurate because it was based on the “estimated figures of about $225–600 billion annually, which the US enterprises might lose due to the assumed theft in the Chinese market” (Kalsie & Arora, 2019, p. 6). Therefore, the so-called “FACTS” (Regan @trish_regan, May 24, 2019) were simply hypothetical figures collected from worried American IP owners stationed abroad instead of real cases of trade disputes from reliable agencies like the World Trade Organization (WTO).

In the first round of the debate as a game, Regan was found incorrect first in her Red Guard labeling of Liu Xin as a CPC member and second in the IP theft statistics of her accusation against China. As for the labeling, she might have done so on purpose to achieve the expected effects of alienating her rival, and she realized that she should have made better use of her team. As for the topics of trade war and IP protection, she has simply copied those statistics without cross-referencing. In brief, Regan had not done her homework carefully enough, and her arrogance brought her a heavy blow. In contrast, Liu Xin’s calm and sincere attitude, confident and assertive behavior plus the cogency in her answers might have impressed Trish Regan, who gradually behaved less and less aggressively.

5.1.2 Round 2: Turning a Debate into a Q&A Versus Using the Q&A as a Meaningful Presentation

During the 15 min debate, Regan turned a previously-announced debate into a de facto interview or Q&A with one question after another pouring onto Liu who “had not been communicated prior to the show,” not to mention any information concerning the nature of the debate and when and where it would be held (CGTN, 2019b, para. 11). During the interview, Regan not only deprived her guest from thousands of miles away of any opportunity to raise a question of her own but also “interrupted Liu at least three times in less than 30 s” (Cai, 2019, para. 5). One of the audiences, Sarina L from the UK commented that during the debate, “Trish kept asking Liu Xin plenty of questions and ended the debate with not even a chance for Liu to ask a single question, which is unfair to Liu” (Chinadaily.com.cn, 2019, para. 6).

After the courtesy introduction, Regan asked Liu to comment on the trade talks between the US and China. Hearing Liu’s emphasis that the US side needs to respect its counterpart by holding talks on equal footing; otherwise, “there will be a prolonged period of problems for both countries” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 9), Regan replied by saying that “trade wars are never good … for anyone” (para. 10), so she advised to get something done, and Liu Xin agreed with her there. This is the first question that Liu Xin’s answer led to a “yes” from Regan. Since Regan had tried to justify the US trade wars against China earlier, her “yes” indicates “a change of heart” (Chinadaily.com.cn, 2019, para. 10).

Then, when Regan asked Liu to define “state capitalism” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 27). Liu defined it as socialism with Chinese characteristics, which makes China quite dynamic and open with mixed systems implemented simultaneously. For instance:

80 % of Chinese employees were employed by private enterprises, 80 % of Chinese exports were done by private companies, and 65 % of technological innovation were achieved and carried out by private enterprises. (para. 28).

As a journalist, Regan knows the efficacy of clear and logical clarification. She understands the power of a series of specific and reliable statistics. Liu’s clear accounts of the mixed, dynamic, and open nature of China’s economy or socialism with Chinese characteristics must have left a very different impression upon not only Regan but other viewers worldwide. Regardless of her condescending attitude during the first half of the debate, Regan softened her tone, and, for the first time, agreed with Liu’s comments on technology transfer “through cooperation” and “payment” in Liu’s words and “playing by the rules” for the “trust between each other” in her own words (CGTN, 2019a, para. 17–18).

On the surface, Regan took charge of the Q&A, but in reality, the Q&A proceeded based on the convincing content in Liu’s answers. As a result, Regan was impressed and gradually made changes in her attitude towards Liu Xin and China. Just as a study shows that Trish has changed her attitude toward China dramatically—“from completely negative to partially positive” (Wang & Zhang, 2020, p. 174). Most importantly, just because Regan turned a debate or a discussion as she had promised into a Q&A, Liu Xin got more time and made full use of every minute presenting her carefully prepared answers to all the important and sensitive topics in Regan’s questions to the audiences in the US and elsewhere in the world, whose “mainstream media rarely broadcast such topics from China’s perspective” (Chinadaily.com.cn, 2019, para. 10).

5.1.3 Round 3: Getting Ready to Listen versus Demonstrating Courage, Sincerity, and Cogency

As the debate continued, Regan raised more challenging questions containing such words as American businesses have been facing the challenges of “getting their property, their ideas, their hard work stolen” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 11) and “China, grow up” (para. 19)! Nonetheless, Liu Xin’s answers gradually calmed her down, and she was willing to listen.

Regarding the issue of China’s IP theft, Liu responded:

… I do not deny that there are IP infringements, and there are copyright issues or there are piracy or even theft of commercial secrets … There are companies in the United States who sue each other all the time over infringement on IP rights. You can’t say, simply because these cases are happening, that America is stealing, or China is stealing, or the Chinese people are stealing. (CGTN, 2019a, paras. 12–14)

Liu’s answer above is persuasive in at least two aspects. On the one hand, although the Trump administration called on US businesses to leave foreign lands and get relocated back home, many American businesses would rather stay and explore the Chinese market simply because they are making profits. On the other hand, IP infringement is a common phenomenon that happens both in the US and China. Within the US, there are cases in which people or companies accuse one another of copyright piracy or trademark violations. From a historical perspective, the US itself did not have copyright laws for more than a century from 1790 to 1891. In other words, for over 100 years, the US publishers could reprint “whatever foreign texts they thought they would sell” (Anderson, 2007, p. 14). Regan may be unaware of the relevant US history, but she must be well-informed of frequent lawsuits over IP infringement inside the US.

Regarding when China can grow up, Liu addressed Regan’s concern with two points. First, although China’s overall economic volume is only next to that of the US. However, taking its 1.4 billion people into consideration, China’s per capita GDP is no more than 1/6 of that of the US. Second, while making donations to humanitarian aid in many parts of the world, China has been making the biggest contributions to UN peacekeeping missions” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 19–20). Although Regan did not respond to Liu’s elaborate answer and quickly changed the topic to tariffs, she might be touched and begin reflecting upon her usual perceptions of China. She may start her reflections when hearing that China’s per capita GDP is less than one-sixth of that of the US, but it is the biggest contributor to the UN peacekeeping missions while the US has been one of the biggest debtors to the NN for years. Regan could not but compromise and start seeing China’s social structure more objectively and rationally.

According to Heng (2019), the US–China TV anchor debate between Trish Regan and Liu Xin has attracted extensive interests in China, with over 150 million hashtags posted on Weibo, and millions of viewers elsewhere in the world anticipating a cross-fire, face-off debate. However, Liu Xin’s careful preparation and outstanding performances during the Q&A debate gradually won over Regan and most of the international audiences. Certainly, there were some verbal traps like the Red Guard labeling and unpleasant nonverbal gestures like frequent interruptions during the entire debate, Liu Xin has, generally speaking, been successful in turning a possible cross-fire debate into a productive conversation.

For the convenience of discussion, we have divided the US–China TV anchor debate into three rounds. The gaming intentions and communication strategies during the three rounds can be summarized as (1) shaming the invited rival versus correcting the host calmly; (2) turning a debate into a Q&A versus using the Q&A as a meaningful presentation; and (3) getting ready to listen versus demonstrating courage, sincerity, and cogency. It should be pointed out that the above three pairs are the major ones, which are by no means 100 % representative.

5.2 Illustrations of the Assumption in WGTICC

Upon close examinations of the three rounds of gaming intentions and communication strategies concerning the assumptions in WGTICC, we found that the selected case has illustrated and expanded the third assumption of the said theory. This assumption reads: “If the rival player shows a clear zero-sum intention, and the host player makes decisions likely to move towards the best and the softest communication strategy, then the game is likely to end with a winning host and losing rival” (Tian, 2021, p. 679). Our arrival at this conclusion results from the following reasoning process.

During the process of the debate, Regan was, in form, the host and she did play the dominant role as a question master during the whole process of the 15 min debate. In reality, it was Liu’s extraordinary performances in terms of both her external character and internal content that shifted her role as a guest into a genuine host because Regan compromised in the process of the debate, gradually changed her attitude towards Liu and China, and eventually followed Liu’s train of thought in the hope of achieving a mutually prosperous US–China trade relation. This means that the assumption of a winning host and losing rival has been illustrated. Considering Regan’s compromise halfway and positive change of attitude towards the end of the debate, especially her apparent expectations of mutual prosperity for both countries, we’d like to expand the assumption from a win-loss to a win-loss-win result, thus expanding the adopted theory of its third assumption. It is worth mentioning here that Trish Regan should be commended for inviting Liu Xin and “welcoming different views on this show” (CGTN, 2019a, para. 2). Otherwise, there would be no such unprecedented, epoch-making, and far-reaching intercultural phenomenon.

5.3 Cultural Roots for the Adopted Gaming Intentions and Communication Strategies

We explored the cultural roots of the gaming intentions and the communication strategies in the adopted case at the material, institutional, and conceptual levels.

At the material level, we found that Fox Business Network and CGTN are not only two media outlets but also two representatives of the US and Chinese mainstream media. While sharing the similarity of being mainstream mass media outlets, they are substantially different in some significant aspects. According to Vigna and Kaplan (2007), it was Rupert Murdock who introduced the 24-h Fox Business News in the US in October 1996. With its headquarters in Delaware, Fox Corporation is a company focusing on news, sports, and entertainment, whose reports and management cover cable network programming, TV, and other corporate eliminations. With a leaner management structure, Fox Corporation keeps growing with financial support from the most recognized and influential US media brands and the establishment of customer relationships based on trust with tech-savvy Fox brands. As of 2021, FOX News and FOX Business are offering their services to “approximately 75 million U.S. households, with the FOX Network available to nearly all U.S. households” (Fox Corporation, 2021, p. 3).

However, mass media in the West have long been brought into the track of marketization and industrialization. Being media and business entities simultaneously, Western media are subject to certain economic consortia. With their private property rights, full economic freedom of choice, and production and consumption information of the market, they have one thing, i.e. the audience, to take to heart. In other words, the life of the Western media is in the hands of the audience. As a result, “meeting the needs of the audience has become the principle of maximizing the interests of the media and the basis and guarantee for them to obtain readers, markets, and profits” (Guo, 2011, p. 19). Trish Regan held a very strong and predominant position in the beginning part of the debate, and her illocutionary acts have been nurtured in the atmosphere of her job place, baked by the US superpower and Western hegemony (Liu & Diao, 2020, p. 151).

As for CGTN, it is a component of CCTV’s foreign-language news services. To expand and strengthen its international broadcasting services for external publicity, CCTV-9 was established in 2000, which was meant to broadcast on a 24-h cycle to target international audiences. To build its own CNN, China expanded the mission of CCTV-9 from “a window to understand China” to “windows to understand both China and the world” with multilingual broadcasting services in Mandarin, English, French, Spanish, Arabic and Russian. Since 2016, CCTV-News services were further expanded with a new name CGTN. The dual objectives of CGTN are “to re-brand its media products to the overseas markets and to keep up with the contemporary trends in global media convergence” (Zhang, 2018, p. 61).

As part of CCTV, CGTN is overseen by the central government which provides mostly ideological guidelines and thought directives. CGTN is supervised by the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT). However, it is characteristic of CGTN to recruit world-known reporters from foreign broadcasting giants in addition to new generations of journalists who have received further training abroad focused on media professionalism. CGTN like its other components of CCTV used to be funded by the government, but it began to raise funding from advertising revenues as well. By following successful Western models like CNN and BBC and by relying on using the latest technology such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Weibo, and apps for hand-held devices, CGTN began offering services in English in as many as 20 world capitals to about “120 nations with a population of 120 million people” (Maina, 2018, p. 33). In brief, CGTN can hardly become a genuine global news channel with its present control. Given its rapid expansion, CGTN as part of “the contra-flow is still short of the power to reverse the dominant flow in global cultural industries” (Lu, 2013, p. 53). While Trish Regan is no longer working for Fox Business News, Liu Xin is still the host of “The Point with Liu Xin” with CGTN, as of August 22, 2023.

At the institutional level, the US media have been undergoing a dramatic transition. Traditionally, as the Fourth Estate enjoys the Constitutionally-authorized full freedom, the US press has been upholding the ideals of nonpartisan, objective, accurate, and fair journalism ethics while playing the watchdog functions of monitoring and scrutinizing political leaders and businesses and keeping the ordinary citizens informed in a detached manner. During conflicts between countries, journalists are expected to play important roles of “contributing to the retention or creation of peace and stability in conflict-affected and threatened areas” (Puddephatt, 2006, p. 4). However, the conventionally institutionalized Fourth Estate has been affected by the social trends shifting from multilateralism to unilateralism and from globalization back to isolation. Coupled with the above, the institution of the US media has also been catalyzed by reinforcing a national identity based on heavy sensationalism and prioritizing the US interests rooted in the largely profit-driven media industry (McChesney, 2003).

Accordingly, Trish Regan supported then President Trump’s trade war against China by calling the American people to act on China on her show in a simple-minded way instead of a critical manner. As time passed by, President Trump stepped down, and President Biden is now the host of the Oval Office in the US. While the US–China trade war has been going on endlessly, the pandemic of COVID-19 broke out in January 2020. The Fox Business Network “parted ways with Trish Regan when she ignited controversy by dismissing the coronavirus pandemic as a conspiracy” to make President Trump step down (Darcy, 2020, para. 1).

Similarly, China’s mainstream and social media have been institutionally reshaping themselves in the past decades. According to Ha et al. (2020), the US media was conventionally hailed as a responsible watchdog of libertarianism, but journalism in China has been usually likened to a “state machine” or “mouthpiece” by following the footprints of the former Soviet communist practice. As a result, many people in the West tend to think that China’s media have been under complete control and got its funding totally from the government. Consequently, they have been the only “sources to obtain information about the outside world” (p. 5). Dramatic changes, however, have been witnessed in the Chinese media as a whole in the past decades.

Since its economic reform and opening up to the outside world policy in 1979, China’s mainstream media have been divided into the Party press and the market-oriented press. The market-oriented press is increasingly commercialized by taking the market and consumers into consideration to attract clients and advertising for its survival and performance. As a result, there has been a new form of professionalism meant to observe such main principles as (1) exercising oversight over the work and conduct of public officials, (2) informing the public of important events, and (3) reflecting public debates on important issues by professionally trained journalists many of whom had been trained even in the West. Since 2014, it has been China’s national mission to develop and construct positive images on myriads of platforms such as online news sites, mobile news apps, Weibo, and WeChat for media convergence. In addition, social media also provide new online platforms where people and organizations produce various news and information to a huge number of audiences (Ha et al., 2020, p. 5). Such changes and developments in the institution of China’s media have made it possible for CGTN program presenter Liu Xin to outshine Trish Regan and attract millions of viewers to follow the debate.

Conceptually, according to Williamson et al. (2011), it is the Republican business elites that injected a new identity to the conservative activists during the 2008 presidential campaign. Such conservative media as the Fox News began mobilizing conservatives for reinforced identity and revitalized conservatism by “pulling the national Republican Party toward the far right” (p. 25). Although conservatism is marked with division instead of unity around the world including the US, anti-Communism has been a uniting force in the conservative movement, and President Trump voiced his support “to a dedicated core of generally right-wing supporters like an ‘authoritarian’” (Ball et al., 2020, para. 5). Thus, it is easy to understand why journalists like Trish Regan in the US and other Western countries are likely to feel frozen in time and turn to “attack” as the only action in times of a crisis, instead of “standing on firm ground and forming a cogent, unified response” (Tanaka, 2019, para. 9).

As for China, with the prevailing Confucian beliefs that a just cause should be pursued for the commonwealth of all and the whole world ought to be one harmonious community, priority has been placed on the common good of the society over the unrestrained rights of the individual. Meanwhile, it has become the national initiative of present-day China to seek a shared community of the common destiny of mankind via its “Belt and Road” initiative rather than striving for one’s own national interests at any cost.

[Post online publication correction added 11 April 2025: the sentence “To this end, President Xi Jinping set it a task for the state media to “portray China as a civilized country featuring a rich history, ethnic unity, and cultural diversity, and as an Eastern power with a good government, a developed economy … and beautiful scenery” (Brady, 2015, p. 55).” was removed.]

Domestically, the Chinese media landscape has evolved by leaps and bounds thanks to the advances in satellite and cable TV, digitized Internet, and social media. To strengthen its international discourse power, China has been taking full advantage of the popular video-sharing platforms like YouTube in the US. Meanwhile, China has made substantial investments to globalize its state-run media such as the creation of CGTN in 2016, whose aims are to serve the global audiences with accurate and timely news coverage and to “enhance mutual trust between China and other countries through cultural exchanges” (CGTN, 2020).

It is clear that, to enhance its international discourse power by disseminating its intended messages to the targeted audiences, CGTN as a representative of China’s mainstream media outlets, has imbedded its mission within the national initiative. Its objectives of disseminating “accurate and timely news” for cultural exchange and intercultural communication are also in line with the task goal of the nation’s top leadership. Thus, it is easy to understand Liu Xin’s careful preparation, impressive performance, and modest self-appraisal throughout the debate with her US counterpart.

6 Conclusions

This study was aimed to identify the involved game intentions and communication strategies as the illustrations of the relevant assumptions in WGTICC and explore the cultural roots for the adopted game intentions and communication strategies. To this end, two RQs have been raised. Below are the research findings in the form of answers to the RQs.

As the answer to RQ1: What are the gaming intentions and communication strategies that illustrate the relevant assumptions in WGTICC? There have been three rounds in the debate, and the gaming intentions and communication strategies can be summarized as shaming the invited rival versus correcting the host calmly in Round 1, turning a debate into a Q&A versus using the Q&A as a meaningful presentation in Round 2 and getting ready to listen versus demonstrating courage, sincerity, and quality in Round 3. Specifically, the selected case has illustrated and expanded the third assumption of WGTICC. It was Liu’s extraordinary performances in terms of external character and internal content that shifted her role as a guest into a genuine host, leading her rival to gradually change her attitude towards and eventually following her train of thought in the hope of achieving a mutually prosperous US–China trade relation. Therefore, it was not only a win-loss but a win-loss-win result, thus supporting and enriching the third assumption of the adopted theory.

As the answer to RQ2: What are the cultural roots for the adopted gaming intentions and communication strategies in the US–China TV anchor debate case? The mainstream Western media are still predominant in the flow of news and power of discourse. However, US media outlets like Fox Business News have been shifting from the Fourth Estate upholding the ideals of nonpartisan, objective, accurate, and fair journalism ethics to unilateralism and isolation, catalyzed by reinforcing the US national identity and prioritizing the US interests based on war journalism. In contrast, the Chinese mainstream media have been developing multiple online platforms while converging with social media, including online news sites, mobile news apps, Weibo and WeChat, and even the US social media of Youtube, Facebook, and Twitter based on peace journalism.

As implications, we have achieved the above research findings under the theoretical frameworks of the cultural game theory, WGTICC, and the cultural analysis model at the material, institutional, and conceptual levels. On the one hand, the adopted theories have provided us with insight into the complete understanding and profound analyses of the selected case, which has been illustrated and expanded from a win-loss to a win-loss-win result. This suggests that even confrontational rivals can make compromises and seek common ground through contacts and talks. On the other hand, the cultural analyses of the selected case have revealed the pattern of compromises and understanding based on unbiased and sincere talks, which may shed light on some seemingly unresolvable conflicts.

The limitations of this study are twofold: first, only one case has been selected and analyzed and, second, the two authors are both from China. Thus, there might be some issues with the representativeness and objectivity of our research findings. For future research, a bigger number of cases can be targeted and the triangulation of authors from the US side or other cultural backgrounds should be taken into consideration.

Funding source: Jiangsu Provincial Research Institute

Award Identifier / Grant number: kycx21_ 3172

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to the editors and peer reviewers for their great help with the publication of this paper.

-

Research funding: The authors acknowledge the research funding of the 2021 Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of the Jiangsu Provincial Research Institute titled “A Comparative Study on the Efficacy of Cross Cultural Grassroots of Social Media: A Case Study of Chinese and Foreign Reviews of Online Red Video Clips” (No. kycx21_ 3172).

References

Allison, G., Kiersznowski, N., & Fitzek, C. (2022). The great economic rivalry: China vs the U.S. https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/GreatEconomicRivalry_Final.pdf Suche in Google Scholar

Amin, S. (2006). Beyond U.S. hegemony? Assessing the prospects for a multipolar world. Trans. World Book Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, E. (2007). Pimps and ferrets: Copyright and culture in the United States, 1831–1891 [Doctoral dissertation]. Bowling Green State University.Suche in Google Scholar

Ang, M. (2020). Debate between US Fox News & China CGTN on US-China trade war, explained. Mothership. https://mothership.sg/2019/05/fox-news-cgtn-debate/ Suche in Google Scholar

Ball, T., Dagger, R., Minogue, K., & Viereck, P. (2020). Conservatism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/conservatism 10.4324/9780429286551-4Suche in Google Scholar

Bown, P. C., & Kolb, M. (2021). Trump’s trade war timeline: An up-to-date guide. https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-investment-policy-watch/trump-trade-war-china-date-guide Suche in Google Scholar

Cai, X. J. (2019). China reacts to Fox, CGTN anchor’s trade war debate. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1004070/china-reacts-to-fox%2C-cgtn-anchors-trade-war-debate360seURL/Shell/Open/Command Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, G. M., & Holt, G. R. (2002). Persuasion through the water metaphor in Dao De Jing. Intercultural Communication Studies, 11, 153–171.Suche in Google Scholar

China Global Television Network (CGTN). (2019a). Full transcript of Liu Xin’s live discussion on Fox. https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d3d774d3245444d35457a6333566d54/index.html Suche in Google Scholar

China Global Television Network (CGTN). (2020). About us China Global. Television Network. https://www.cgtn.com/about-us Suche in Google Scholar

Chinadaily.com.cn. (2019). How do you view the debate between Trish Regan and Liu Xin? https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201906/01/WS5cf1c12ca3104842260bef69_1.html Suche in Google Scholar

Chu, T. (2011). 以博弈论视角探析中西文化碰撞及文化全球化趋势 [An analysis of the Chinese and Western cultural collision and cultural globalization trend from the perspective of game theory]. Cultural Academic Journal, 4, 75–79.Suche in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Darcy, O. (2020). Fox business parts ways with Trish Regan, host who dismissed coronavirus as “impeachment scam”. CNN Business. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/27/media/trish-regan-fox-news/index.html Suche in Google Scholar

Economy, E. (2021). Advancing effective U.S. policy for strategic competition with China in the twenty-first century. https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/031721_Economy_Testimony2.pdf Suche in Google Scholar

Fox Corporation. (2021). Fox annual report 2021. https://media.foxcorporation.com/wp-content/uploads/prod/2021/09/17193711/FOX-2021-Annual-Report_Final_Web.pdf Suche in Google Scholar

Geftner, A. (2008). Creationists declare war over the brain. New Scientist, 2679, 46–47.10.1016/S0262-4079(08)62714-1Suche in Google Scholar

Global Television Network (CGTN). (2019b). Behind the scenes: How does Liu Xin see the unprecedented debate on fox? http://chinaplus.cri.cn/news/china/9/20190530/296154.html Suche in Google Scholar

Gong, J. C., & Zhao, D. (2015). 全球化背景下中西方文化安全博弈分析——基于不完全信息动态博弈模型 [A game analysis of Chinese and Western culture security under the background of globalization—based on the incomplete information dynamic game model]. Journal of Hubei Economics Institute, 12, 28–30.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, D. R. (2011). 中西新闻传播理念的若干差异 [Some differences between Chinese and Western news communication ideas]. Journalism Lover, 1, 18–19.Suche in Google Scholar

Ha, L., Yang, Y., Ray, R., Matanji, F., & Chen, P. Q. (2020). How US and Chinese media cover the US-China trade conflict: A case study of war and peace journalism practice and the foreign policy equilibrium hypothesis. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 1, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12186 Suche in Google Scholar

Heng, W. L. (2019). A great debate set over tariffs, technology. China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201905/29/WS5cedf646a3104842260be73d.html Suche in Google Scholar

Huang, L. N., & McAdams, K. C. (2000). Ideological manipulation via newspaper accounts of political conflict. In A. Malek & A. P. Kavoori (Eds.), The global dynamics of news: Studies in international news coverage and news agenda (pp. 57–74). Ablex.Suche in Google Scholar

Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. Simon & Schuster.Suche in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund. (2018). World economic outlook, October 2018: Challenges to steady growth. International Monetary Fund.Suche in Google Scholar

Jacques, M. (2019). When China rules the world: The rise of the Middle Kingdom and the end of the Western World. Penguin Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Jervis, R. (2003). Understanding the Bush doctrine. Political Science Quarterly, 118(3), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165x.2003.tb00398.x Suche in Google Scholar

Ji, D. Q. (2021). 超越西方化:中国国际传播的困境与出路 [Beyond westernization: The way out of China’s communication dilemma and internationalization]. https://icsf.cuc.edu.cn/2021/0720/c5607a184701/page.htm Suche in Google Scholar

Jia, W. S., & Ji, Z. W. (2018). 人类命运共同体与全球传播 [Community of human destiny and global communication]. Global Media Journal, 5(3), 27–37.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalsie, A., & Arora, A. (2019). US-China trade war: The tale of clash between the biggest developed and developing economics of the world. Management and Economics Research Journal, 5(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.18639/merj.2019.956433 Suche in Google Scholar

Katz, N., & McNulty, K. (1994). Conflict resolution. https://www.centriguida.it/conflict_resolutions.pdf Suche in Google Scholar

Kissinger, H. (2011). On China. Easton Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Layne, C., & Thayer, B. A. (2007). American empire: A debate. Routledge.10.4324/9780203961506Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Z. C., & Diao, H. Y. (2020). The analysis of the illocutionary acts and the effects in the debate on trade friction between the hosts of China Global Television Network and Fox Business Channel. Academy Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 3(7), 143–153.Suche in Google Scholar

Lu, Y. (2013). The relationship, tension and interaction between cultural imperialism and contra-flow in contemporary media culture. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 1(4), 50–53.10.4236/ajc.2013.14006Suche in Google Scholar

Mahbubani, K. (2021). Has China won? The Chinese challenge to American primacy. CITIC Publishing Group.Suche in Google Scholar

Maina, M. J. (2018). The role of China Global Television network in fostering Chinese public diplomacy in Kenya [Unpublished MA thesis]. University of Nairobi.Suche in Google Scholar

McChesney, R. W. (2003). The problem of journalism: A political economic contribution to an explanation of the crisis in contemporary US journalism. Journalism Studies, 4(3), 299–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700306492 Suche in Google Scholar

Nye, S. J. (2015). The future of U.S.-China relations. https://www.chinausfocus.com/foreign-policy/the-future-of-us-china-relations Suche in Google Scholar

Overhaus, M., Rudolf, P., & Daniels, L. V. (2020). American perceptions of China. In B. Lippert & V. Perthes (Eds.), Strategic rivalry between United States and China: Causes, trajectories, and implications for Europe. German Institute for International and Security Affairs. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/research_papers/2020RP04_China_USA.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Pang, P. (1986). 文化结构与近代中国 [Culture structure and contemporary China]. China Social Science, 5, 81–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Perthes, V. (2020). Dimensions of strategic rivalry: China, the United States and Europe’s place. In B. Lippert & V. Perthes (Eds.), Strategic rivalry between United States and China: Causes, trajectories, and implications for Europe. https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2020RP04_China_USA.pdf Suche in Google Scholar

Petrosyan, A. (2023). Internet usage worldwide—Statistics & Facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/1145/internet-usage-worldwide/#editorsPicks Suche in Google Scholar

Ponelis, S. R. (2015). Using interpretive qualitative case studies for exploratory research in doctoral studies: A case of information systems research in small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10, 535–550. https://doi.org/10.28945/2339 Suche in Google Scholar

Puddephatt, A. (2006). Voices of war: Conflict and the role of the media. International Media Support. https://www.mediasupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ims-voices-of-war-2006.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Regan, T. (2019). Trish Regan: China plays by its own set of rules. https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/trish-regan-china-plays-by-its-own-set-of-rules Suche in Google Scholar

Rowley, J. (2002). Using case studies in research. Management Research News, 25(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170210782990 Suche in Google Scholar

Shi, X. (2012). 话语研究方法的中国模式 [The Chinese mode of discourse research methods]. Journal of Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, 23(6), 5–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Shi, A. B., & Dai, R. T. (2020). Mapping discursive communities and branding “global China”: The case of Sino-US TV anchors’ debate. French Journal for Media Research, 13. https://doi.org/10.21637/gt.2020.1.01. https://frenchjournalformediaresearch.com/lodel-1.0/main/index.php?id=1956 Suche in Google Scholar

Snow, D. M. (2007). National security for a new era: Globalization and geopolitics (2nd ed.). Pearson Education, Inc.Suche in Google Scholar

Spencer, J. (2022). Chinese social media statistics and trends infographic. https://makeawebsitehub.com/chinese-social-media-statistics/ Suche in Google Scholar

Sturman, A. (1997). Case study methods. In J. P. Keeves (Ed.), Educational research, methodology and measurement: An international handbook (2nd ed., pp. 61–66). Pergamon.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanaka, K. G. (2019). How can US Fox News reporting improve? http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201906/03/WS5cf4bbeda310519142700bb9.html Suche in Google Scholar

Thomas, G. (2011). A typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse and structure. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(6), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411409884 Suche in Google Scholar

Tian, D. X. (2021). Construction of a water and game theory for intercultural communication. International Communication Gazette, 83(7), 662–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520921109 Suche in Google Scholar

Vigna, S. D., & Kaplan, E. (2007). The Fox news effect: Media bias and voting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1187–1234. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1187 Suche in Google Scholar

Vos, T., & Craft, S. (2017). The discursive construction of journalistic transparency. Journalism Studies, 18(12), 1505–1522.10.1080/1461670X.2015.1135754Suche in Google Scholar

Wahab, N. A., Otherman, M. S., & Muhammad, N. (2017). The influence of the mass media in the behavior students: A literature study. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(8), 166–174.10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, K. Q. (2005). 文化博弈与文化整合 [Cultural games and cultural integration]. Changbai Journal, 5, 101–104.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, W. C., & Zhang, X. F. (2020). From confrontation to collaboration: Attitudinal changes of Trish Regan on US-China trade war in commentaries and debate. English Literature and Language Review, 6(8), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.32861/ellr.68.174.181 Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, R. (1961). The long revolution. Broadview Press.10.7312/will93760Suche in Google Scholar

Williamson, V., Skocpol, T., & Coggin, J. (2011). The Tea Party and the remaking of republican conservatism. Perspectives on Politics, 9(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/s153759271000407x Suche in Google Scholar

Yuan, J. D. (2003). Friend or foe? The Bush administration and U.S. China policy in transition. East Asian Review, 15(3), 39–64.Suche in Google Scholar

Zaidi, S. M. S., & Saud, A. (2020). Future of US-China relations: Conflict, competition or cooperation? Asian Social Science, 7, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v16n7p1 Suche in Google Scholar

Zainal, Z. (2007). Case study as a research method. Journal Kemanusiaan, 9, 1–6.Suche in Google Scholar

Zengzi. (2006–2023). 礼记·大学 [Liji·The great learning]. Retrieved from https://ctext.org/liji/da-xue Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Y. (2018). China Global Television Network’s international communication: Between the national and the global [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Calgary.Suche in Google Scholar

[Post online publication correction added 11 April 2025: the reference “Brady, A. (2015). China’s foreign propaganda machine. Journal of Democracy, 26(4), 51–59.” was removed.]Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Interview

- Roundtable Discussion of Emerging Technology Companies and Transcultural Challenges

- Research Articles

- Regulating Dominant Platforms: Challenges and Opportunities of Content Moderation on Jio Platforms

- A Transcultural Interpretation of Key Concepts in China-US Relations: Hegemony, Democracy, Individualism and Collectivism

- Postcolonial Analysis of Transcultural News Frames: A Case Study of Facebook Rebranding

- Win-Loss-Win in the US–China Game: A Cross-cultural Analysis of a TV Anchor Debate Between Trish Regan and Liu Xin

- I am in the Homeless Home or I Am Always on the Way Home: Formatting Identity and Transcultural Adaptation Through Ethnic and Host Communication

- The Multi-discourse Fight of COVID-19 Vaccine in the World of Digital Platforms: Rethinking Popularity of Anti-intellectualism

- A Virtual Transcultural Understanding Pedagogy: Online Exchanges of Emic Asian Cultural Concepts