Abstract

Objectives

The identification of causes of stillbirth (SB) can be a challenge due to several different classification systems of SB causes. In the scientific literature there is a continuous emergence of SB classification systems, not allowing uniform data collection and comparisons between populations from different geographical areas. For these reasons, this study compared two of the most used SB classifications, aiming to identify which of them should be preferable.

Methods

A total of 191 SBs were retrospectively classified by a panel composed by three experienced-physicians throughout the ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems to evaluate which classification minimizes unclassified/unspecified cases. In addition, intra and inter-rater agreements were calculated.

Results

ReCoDe defined: the 23.6% of cases as unexplained, placental insufficiency in the 14.1%, lethal congenital anomalies in the 12%, infection in the 9.4%, abruptio in the 7.3%, and chorioamnionitis in the 7.3%. ICD-PM defined: the 20.9% of cases as unspecified, antepartum hypoxia in the 44%, congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities in the 11.5%, and infection in the 11.5%. For ReCoDe, inter-rater was agreement of 0.58; intra-rater agreements were 0.78 and 0.79. For ICD-PM, inter-rater agreement was 0.54; intra-rater agreements were of 0.76 and 0.71.

Conclusions

There is no significant difference between ReCoDe and ICD-PM classifications in minimizing unexplained/unspecified cases. Inter and intra-rater agreements were largely suboptimal for both ReCoDe and ICD-PM due to their lack of specific guidelines which can facilitate the interpretation. Thus, the authors suggest correctives strategies: the implementation of specific guidelines and illustrative case reports to easily solve interpretation issues.

Introduction

According to a recent report called A Neglected Tragedy: The Global Burden of Stillbirths, the first-ever stillbirth report by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN-IGME) [1], every 16 s one stillbirth (SB) occurs: about two million SBs per year. These losses are responsible for social, psychological, economic, and medical negative consequences [1], [2], [3]. SBs can also determine misunderstandings between parents and healthcare operators, causing medical malpractice claims [4]. For these reasons, SBs represent a significant burden for all societies because they can generate unpredictable negative impact on families [1], [2], [3, 5], [6], [7], [8], [9].

The high number of SBs is a growing public health issue: “in 2000, the ratio of the number of stillbirths to the number of under-five deaths was 0.30; by 2019, it had increased to 0.38” [1]. According to the United Nation Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (2020), this can be due to “absence of or poor quality of care during pregnancy and birth; lack of investment in preventative interventions and the health workforce; inadequate social recognition of stillbirths as a burden on families; measurement challenges and major data gaps; absence of global and national leadership; and no established global targets” [1].

Knowledge of the cause of stillbirth is important for two reasons. Firstly, it is important to provide the most accurate information for continued care of the families and secondly, it is crucial to know accurate causes to inform healthcare prevention strategies. Thus, healthcare professionals (especially obstetricians, clinicians, and pathologists) should be able to correctly classify the causes of SBs. In clinical and pathology routines, the identification of SBs’ causes can be a challenge because of the intrinsic complexity of fetal/maternal pathophysiology. It can be difficult to reach a definite cause of death. This challenge is complicated due to several different classification systems of SB causes used by the world’s medical professionals. In the scientific literature there is a continuous emergence of SB classification systems, not allowing uniform data collection and comparisons between populations from different geographical areas [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18].

In the light of the above, this study compared two of the most used SB classifications (ReCoDe and ICD-PM), aiming to identify which of them should be preferable. In order to reach this goal, unexplained/unspecified cases of each classification were compared. Intra and inter-rater agreements were compared and discussed.

Materials and methods

In this study, the authors adhered to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki regarding ethical conduct of research.

Population and data analysis

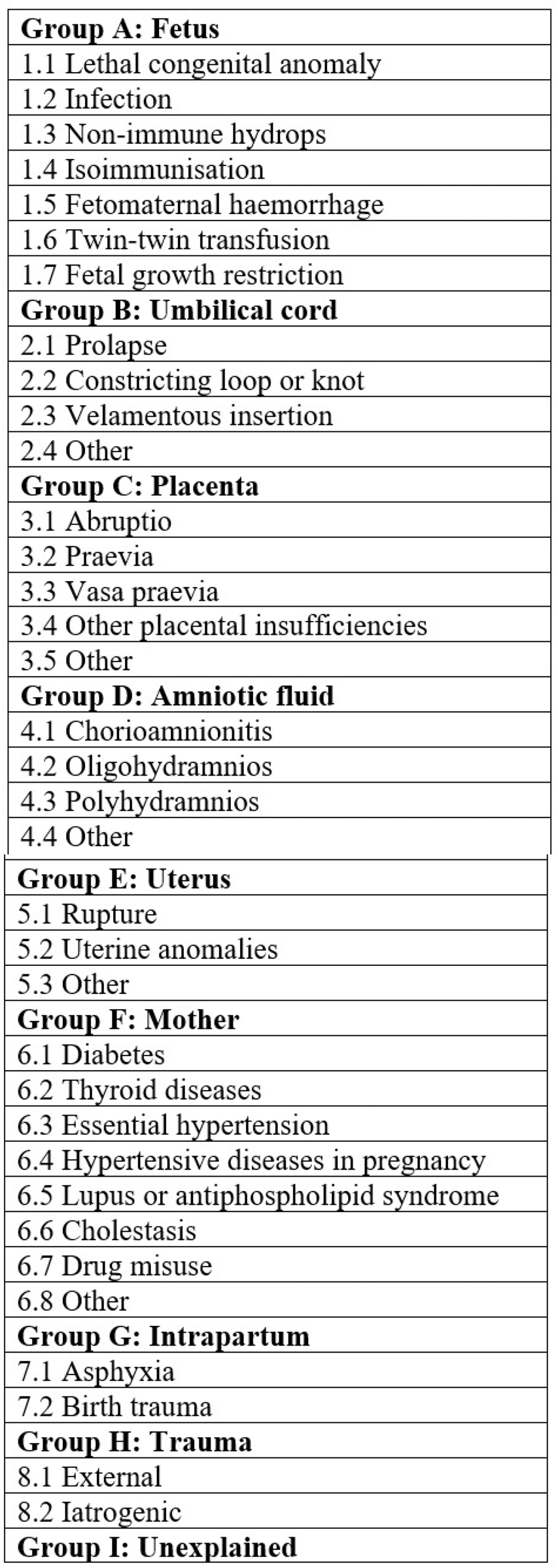

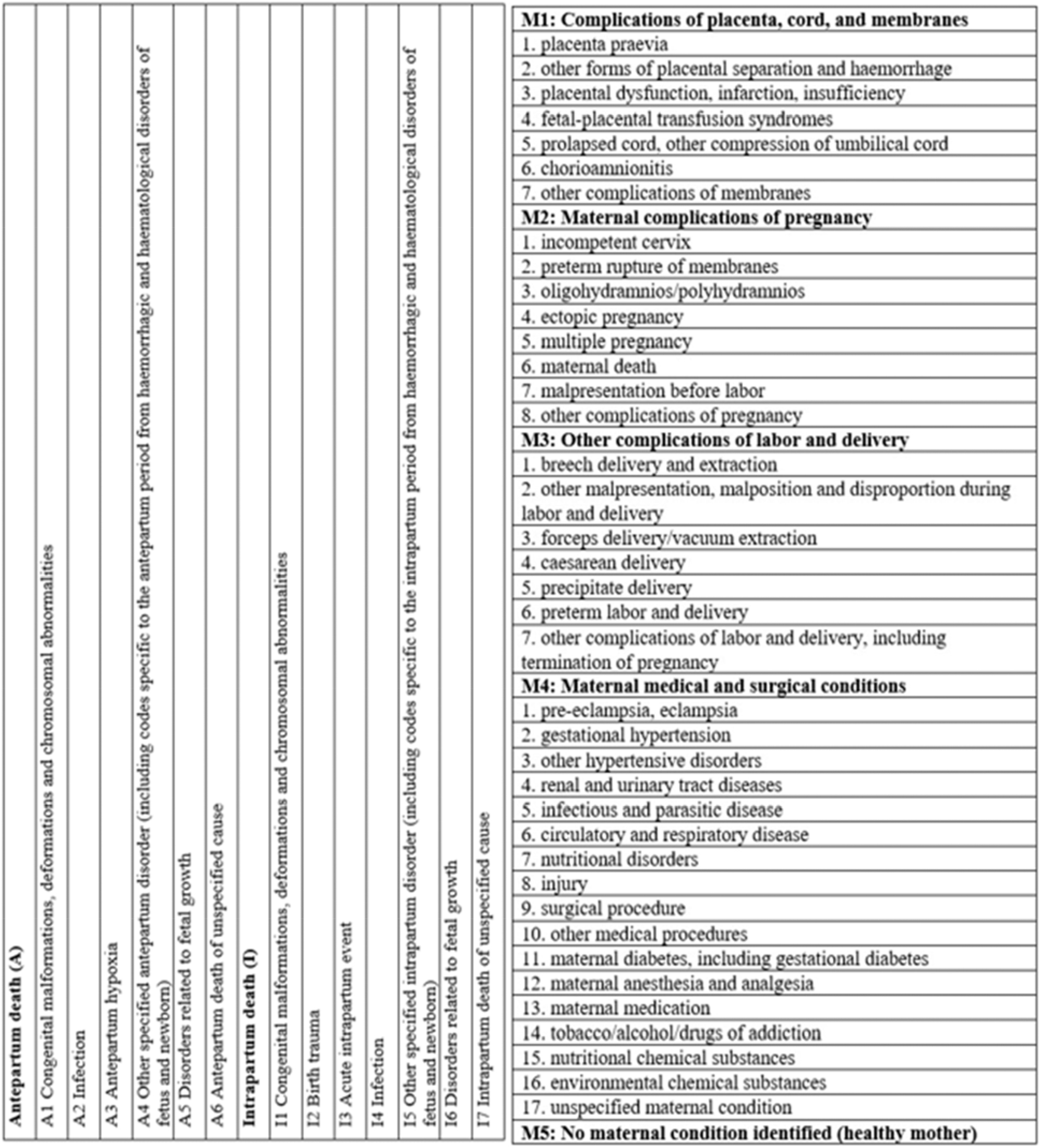

The authors conducted a retrospective analysis of all cases of SBs – characterized by gestational ages equal or higher than 22 weeks – which occurred in the gynecologic and obstetric hospital (called Sant’Anna; referral hospital for high-risk pregnancies; all cases came from pregnancies managed by the above-mentioned hospital) of Turin (Italy) from January 2015 to December 2019. During this period there were 34,417 deliveries (SB rate: 6.1 per 1,000). The study included twin-pregnancies. Each case was collected in an Excel sheet containing the following data: parents’ medical history, date of delivery, maternal age, gestational age, fetal sex, birth weight, maternal laboratory tests, pregnancy/delivery details, autopsy and histological (fetus, placenta, and umbilical cord) data. In all cases, fetal autopsy/histology and placental/umbilical cord gross and microscopic examinations were conducted. These data were also collected in the Excel sheet. In order to allow the comparison between present study’s results and literature’s data, after analyzing the abovementioned information, a panel of three physicians (experienced in SB diagnosis), classified all SBs with ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems. Then, the abovementioned cases were divided in two groups for both ReCoDe and ICD-PM data: group 1 – unclassified/unspecified (ReCoDe Group I and ICD-PM A6/I7 categories) cases [10] (Figures 1 and 2); group 2 – classified/specified cases [19].

ReCoDe classification.

ICD-PM classification for fetal and maternal conditions.

Intra/inter-rater agreements

The second part of this study consisted of intra and inter-rater agreements’ calculation. In order to accomplish this aim, two experienced physicians – different from the ones who had been part of the aforementioned expert panel – (operator #1 – OP#1 and operator #2 – OP#2) separately classified the SBs according to the ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems (Figures 1 and 2). Inter-rater agreements between the two OPs for both classifications were calculated throughout the weighted kappa coefficient–K [20], [21], [22]. After 1 month from the first scoring round, each operator was called to rescore – throughout ReCoDe and ICD-PM classifications – the SBs considering the same available data. Intra-rater agreement (weighted kappa coefficient for >2 ordered categories–K) was calculated for OP#1 and OP#2 for both classification systems [20], [21], [22].

Agreements were evaluated in the light of the following classification: poor if K<0.00; slight if 0.00≤K≤0.20; fair if 0.21≤K≤0.40; moderate if 0.41≤K≤0.60; substantial if 0.61≤K≤0.80; almost perfect if K>0.80 [20], [21], [22]. Statistical analyzes were performed throughout the IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software.

Results

A summary of the most significant data is available in Tables 1 –3. Data on 191 SBs were collected. Maternal ages were characterized by a mean of 34.1 years (SD ± 5.5 years; median 34 years; mode 32 years). Gestational ages’ mean was 204.2 days (SD ± 43.4 days; median 194 days; mode 154 days).

Results of the application of ReCoDe classification.

| Group A Fetus | n |

|---|---|

| 1.1 Lethal congenital anomaly | 23 (12%) |

| 1.2 Infection | 18 (9.4%) |

| 1.5 Fetomaternal haemorrhage | 2 (1%) |

| 1.6 Twin-twin transfusion | 3 (1.6%) |

| 1.7 Fetal growth restriction | 7 (3.7%) |

|

|

|

| Group B Umbilical cord | n |

|

|

|

| 2.2 Constricting loop or knot | 7 (3.7%) |

| 2.4 Other | 17 (8.9%) |

|

|

|

| Group C Placenta | n |

|

|

|

| 3.1 Abruptio | 14 (7.3%) |

| 3.2 Praevia | 1 (0.5) |

| 3.4 Other placental insufficiencies | 27 (14.1%) |

| 3.5 Other | 9 (4.7%) |

|

|

|

| Group D Amniotic fluid | n |

|

|

|

| 4.1 Chorioamnionitis | 14 (7.3%) |

| 4.2 Oligohydramnios | 1 (0.5%) |

|

|

|

| Group F Mother | n |

|

|

|

| 6.1 Diabetes | 2 (1%) |

| 6.8 Other | 1 (0.5%) |

|

|

|

| Group I Unexplained | n |

|

|

|

| 9.1 | 45 (23.6%) |

-

n, number of cases.

Results of the application of ICD-PM classification to fetal conditions.

| ICD-PM fetal categories | |

|---|---|

| A Antepartum death | n |

| A1 Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities | 22 (11.5%) |

| A2 Infection | 22 (11.5%) |

| A3 Antepartum hypoxia | 84 (44%) |

| A4 Other specified antepartum disorder | 5 (2.6%) |

| A5 Disorders related to fetal growth | 8 (4.2%) |

| A6 Antepartum death of unspecified cause | 39 (20.4%) |

|

|

|

| I Intrapartum death | n |

|

|

|

| I3 Acute intrapartum event | 10 (5.2%) |

| I7 Intrapartum death of unspecified cause | 1 (0.5%) |

-

n, number of cases.

Results of the application of ICD-PM classification to maternal conditions.

| ICDM-PM maternal categories | |

|---|---|

| M1 Complications of placenta, cord, and membranes | n |

| M1.2 Other forms of placental separation and haemorrhage | 13 (6.8%) |

| M1.3 Placental dysfunction, infarction, insufficiency | 44 (23%) |

| M1.4 Fetal-placental transfusion syndromes | 3 (1.6%) |

| M1.5 Prolapsed cord, other compression of umbilical cord | 29 (15.2%) |

| M1.6 Chorioamnionitis | 32 (16.8) |

| M1.7 Other complications of membranes | 20 (10.5%) |

|

|

|

| M2 Maternal complications of pregnancy | n |

|

|

|

| M2.1 Incompetent cervix | 1 (0.5%) |

| M2.2 Preterm rupture of membranes | 1 (0.5%) |

| M2.3 Oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios | 6 (3.1%) |

| M2.5 Multiple pregnancy | 5 (2.6%) |

|

|

|

| M4 Maternal medical and surgical conditions | n |

|

|

|

| M4.1 Pre-eclampsia, eclampsia | 3 (1.6%) |

| M4.5 Infectious and parasitic disease | 1 (0.5%) |

| M4.6 Circulatory and respiratory disease | 1 (0.5%) |

| M5 No maternal condition identified | 32 (16.7%) |

-

n, number of cases.

Results of the panel

Considering ReCoDe system (Table 1), the most frequent SB’s causes were classified as C3.4 (placental insufficiency, 14.1%), followed by A1.1 (lethal congenital anomalies, 12%), A1.2 (infection, 9.4%), C3.1 (abruptio, 7.3%), and D4.1 (chorioamnionitis, 7.3%). ReCoDe defined as unexplained (Group I) 45/191 cases (23.6%) [10].

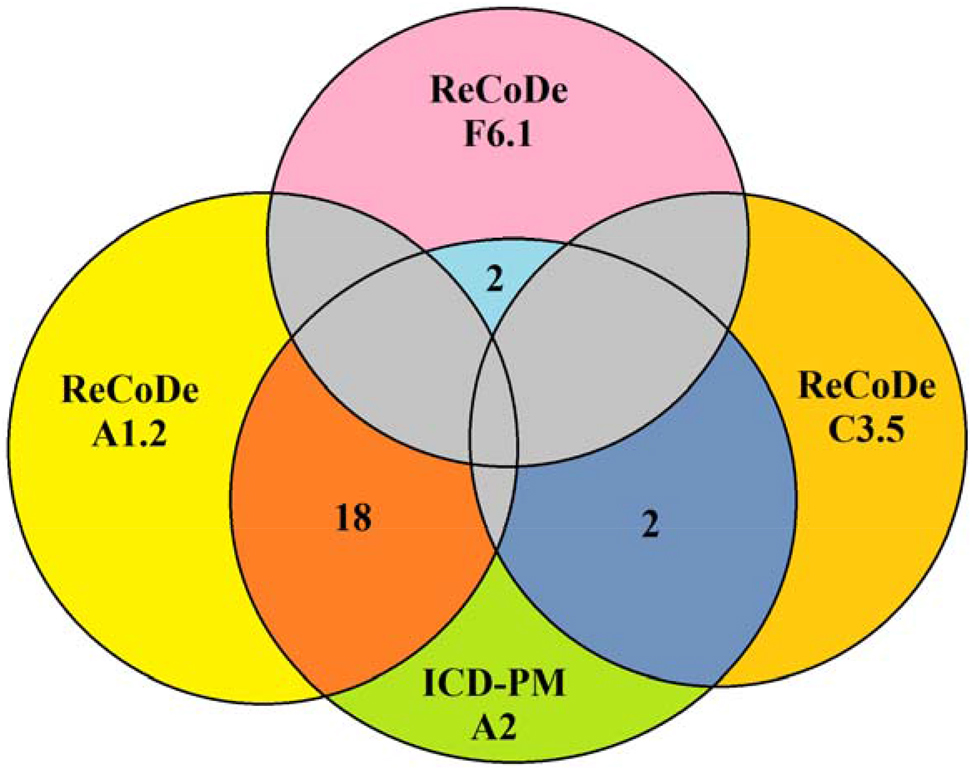

According to ICD-PM (Tables 2 and 3), the most frequent causes were classified as A3 (antepartum hypoxia, 44%), followed by A1 (congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities, 11.5%), and A2 (infection, 11.5%). Intrapartum deaths (I category) were 11/191 (5.7%). ICD-PM identified as unspecified (categories A6 or I7) 40/191 cases (20.9%). Figures 3 –5 show how the abovementioned main causes of SB were differently recorded by the two classification systems.

Graphical representation of cases’ distribution between ICD-PM A2 (infections), ReCoDe A1.2 (fetus, infections), ReCoDe C3.5 (placenta, other), and ReCoDe F6.1 (mother, diabetes).

Graphical representation of cases’ distribution between ReCoDe A1.1 (fetus, lethal congenital anomaly), ICD-PM A1 (congenital malformations), and ICD-PMA3 (antepartum hypoxia).

Graphical representation of cases’ distribution between ICD-PM A5 (disorders related to fetal growth), ReCoDe A1.7 (fetus, fetal growth restriction), and ReCoDe B2.4 (umbilical cord, other).

The most common maternal conditions (M) were: M1.3 (placental dysfunction, infarction, insufficiency, 23%); M1.6 (chorioamnionitis, 16.8%); M1.5 (prolapsed cord, other compression of umbilical cord, 15.2%). In 32/191 cases (16.7%), relevant maternal conditions (M5) were not identified. Among all 191 cases, 8 (4.2%) were simultaneously defined by ICD-PM as A6/I7 (antepartum/intrapartum of unspecified cause) and M5 (no maternal condition identified) [19].

Inter/intra-rater agreement evaluated between and on OP#1 and OP#2

For ReCoDe classification, the inter-rater agreement was 0.58 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.47 to 0.68); OB#1 intra-rater agreement was 0.78 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.69 to 0.87); OB#2 intra-rater agreement was 0.79 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.66 to 0.85). For ICD-PM classification, the inter-rater agreement was 0.54 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.44 to 0.67); OB#1 intra-rater agreement was 0.76 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.61 to 0.88); OB#2 intra-rater agreement was 0.71 (weighted K, 95% confidence interval, 0.65 to 0.81).

Discussion

General considerations

The abovementioned results highlighted significant differences between ReCoDe and ICD-PM classifications. These differences are manifest comparing similar categories of the two methods: (1) infections, 18 cases for ReCoDe and 22 for ICD-PM; (2) fetal growth restriction, 7 for ReCoDe and 8 for ICD-PM. As depicted in Figures 3 and 5, this happened because ReCoDe classification is characterized by Group B (umbilical cord), Group C (placenta), and Group F (mother). These categories are not provided by ICD-PM in which umbilical cord, placenta, and maternal pathologies are listed in the so-called maternal conditions. Thus, using ReCoDe system some cases can be classified directly as caused by the above-mentioned conditions. On the contrary, using ICD-PM, maternal conditions are defined as “a condition that would reasonably be considered to be part of the pathway leading to perinatal death” but not the leading one [19]. This justifies the aforementioned discrepancies between the two classifications for infection and fetal growth restriction categories. Similar considerations can be suggested for the only case that was assigned by ICD-PM to A3 (antepartum hypoxia) and by ReCoDe to A1.1 (lethal congenital anomaly) (see Figure 4). Antepartum hypoxia is not provided as leading cause by ReCoDe system causing a different interpretation and classification of this case by observers.

As suggested by the scientific literature and by the abovementioned results, direct comparation between two or more different SB classifications is particularly difficult because of their intrinsic differences [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. For this reason, the present manuscript focused on the evaluation of unexplained/unspecified cases and on inter and intra-rater agreements, as follows.

Considerations on unexplained and unspecified cases

Recently, Wojcieszek et al. pointed out that the strength of SBs’ classification systems should be based on consensus on the fundamental characteristics of such systems [16], highlighting limits and strengths of several existing methods. One of the methods used to evaluate two or more SB classifications relies on the comparison of their limits and strengths establishing which of them minimizes the number of unexplained/unspecified cases [12, 13]. In the scientific literature, there are few indications about this subject, especially for ICD-PM classification. There is a major number of articles in which methods – other than ICD-PM – are compared. In 2009 Flenady et al. identified percentages of unexplained SBs for the following classification systems (Amended-Aberdeen 44.3%; Extended Wigglesworth 50.2%; PSANZ-PDC 15.4%; ReCoDe 13.8%; Tulip 10.2%; CODAC 9.5%) [23]. In 2016, Nappi et al. registered unexplained SBs in the 14% for ReCoDe, in the 16% Galan-Roosen, and in the 18% for Tulip [24]. In 2008, Vergani et al. described unexplained SB in the 14.3% of cases [18]. However, these three articles did not report intra and/or inter-rater agreement.

In 2019 Dapoto et al. study yielded unexplained/unspecified causes in the 16.7% of cases for ReCoDe and in the 9.3% for ICD-PM [13]. They identified a clear difference between the two classification which they did not ascribe “to a better performance of the classification [ICD-PM], but simply of the lack of recognition of a primary vs. associated condition” [13]. In the present study, the panel of experienced physicians defined different percentages, especially for ICD-PM.

The percentage of ReCoDe’s unexplained cases (23.4%) of the present manuscript is slightly higher than the one available in other manuscripts [10, 18, 23]. This can be justified by differences in populations from whom studies’ samples come from and the quality/quantity of information available for each SB [10, 18, 23].

ICD-PM classification yielded 40/191 cases (20.9%) as unspecified. If compared with the manuscript by Dapoto et al. [13], at first sight this could appear as a meaningful difference of percentages. Their results appear to be affected by a different interpretation of the definition of what unspecified means for ICD-PM classification. In Dapoto et al. manuscript, the percentage of 9.3% was referred to the cases classified both A6/I7 and M5. For these authors the causes of SBs can be defined as unspecified only when both fetal and maternal data are unremarkable [13]. This interpretation seems to contrast with the World Health Organization (WHO) application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period [19]. In 2016 the WHO published its indications about how ICD-PM classification should be used, specifying as A1–A6 (antepartum) and I1–I7 (intrapartum) categories express fetal “disease or condition that initiated the morbid chain of events leading to death” [19]. According to the WHO, the cause expressed by A and I categories “is the single identified cause of death and it should as specific as possible” [19]. Maternal conditions – expressed with M1–5 categories – is defined as “a condition that would reasonably be considered to be part of the pathway leading to perinatal death” [19]. In the light of WHO indications, it can be stated that for ICD-PM system, the definition of unspecified SBs should be expressed only with A6 or I7 categories. Maternal conditions (M1–M5) should not influence this definition [19]. In contrast with WHO statements, Dapoto et al. defined as unspecified only the cases in which fetal ad maternal conditions were both unremarkable [13]. Their unspecified cases (9.3%) come from a different application of ICD-PM. If we consider only the cases in which they identified A6 or I7 categories (as prescribed by the WHO), the percentage of their unspecified cases (22%) is similar to the one yielded by the present study (20.9%).

In 2018, Maducolil et al. reported the 11.6% of unexplained cases and the 7.5% of unspecified ones respectively for ReCoDe and ICD-PM [25]. In Maducolil’s manuscript it is not specified if the authors classified SBs as unspecified when A6 or I7 categories are assigned (as suggested by the WHO) or when fetal and maternal conditions are both unremarkable (A6/I7 and M5) [25]. For this reason, it is difficult to compare the present results with Maducolil et al. However, Maducolil et al. studied a different SB sample than our present study: only 9.1% of their cases had autopsy information; they considered SBs with a gestational age ≥24 weeks [25]. In the present manuscript: the cases were characterized by gestational ages ≥22 weeks; all cases underwent full autopsy and microscopic examination of fetus, placenta, and umbilical cord.

For ICD-PM classification in the scientific literature different percentages of unspecified SBs are available: they vary from 4.14% to 37.89% [11, 13, 26]. As already stated, this variability can be referred to the differences in populations from whom studies’ samples come from and in quality/quantity of information available for each SB. Even if several authors pointed out meaningful considerations about SB unspecified/unexplained cases, it is important to know that there is an intrinsic difficulty to compare results and considerations of different studies. These differences constitute a significant limitation in this field because they limit the applicability of studies’ considerations to other populations and the comparison of results. In addition, it is important to note that current SB classification systems do not provide twin-specific categories. This can cause the loss of information regarding the cause of death, affecting the number of unexplained/unspecified SBs of the studies in which – as for the present one – twin pregnancies are included [27].

Considerations on intra/inter-rater agreements

In the absence of common methodologies to study differences in unexplained/unspecified cases between classifications, the determination of intra and inter-rater agreements can be fundamental requirement to understand which method can be used more consistently. This was highlighted by the Delphi paper by Wojcieszek et al. who reported high inter- and intra-rater reliability among the functional characteristics which a global classification system should have [16].

In the scientific literature, the only available data about the two classifications used in the present manuscript are related the article by Flenady et al. in which ReCoDe inter-rater agreement is moderate (K 0.51) [20], [21], [22], [23]. ReCoDe intra-rater agreement and ICD-PM intra and inter-rater agreements are not reported by other authors. For ReCoDe system, the present study yielded an inter-rater agreement of 0.58 allowing to sustain the same considerations of the abovementioned article.

ReCoDe intra-rater agreements for OB#1 and OB#2 were respectively 0.78 and 0.79, demonstrating a slightly higher agreement which can be defined as substantial [20], [21], [22].

Considering ICD-PM classification, the results of the present study represent the only available in the scientific literature. The use of ICD-PM yielded K 0.54, K 0.76, and K 0.71 respectively for intra-rater agreement, OB#1 inter-rater agreement, and OB#2 inter-rater agreements. These data are similar with the ones obtained using ReCoDe system. Since it appears that ReCoDe does not perform better than ICD-PM (and vice versa), it can be stated that intra and inter-rater agreement results do not seem to be meaningful tools which can justify the use of one of these methods instead of the other one.

Causes of poor agreement and corrective proposals

In the scientific literature, some authors reported inter-rater agreements for major categories evaluated by different SB classifications [23]. Their agreements ranged from excellent to good (high variability) [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. The study of Flenady et al. identified suboptimal Ks suggesting that the reasons can be the following: “the majority of classification systems failed to provide sufficient instructions on use” [23]. According to the authors of the present manuscript, the absence of specific instructions is the main cause of low statistical agreements. This negatively affects especially inter-rater agreement that is calculated between two different observers who – due to the abovementioned absence – do not have specific indications that can guide their activity. Intra-rater agreement yielded higher values of K because the two observations were performed by one observer who had the same knowledge of how applying the two classifications. For these reasons, the authors suggest that all classifications should have specific guidelines to reduce errors caused by personal interpretations. The guidelines should also provide a legend for all terms and definitions used.

Poor agreement can be also caused by the lack of practical indications. Indeed, SB classifications methods do not systematically provide exemplificative cases which can facilitate understanding. According to the authors of this manuscript, all classifications should include an exemplificative case report for each main group/category. This can easily solve interpretation issues.

Moreover, in each center which deals with SB diagnosis, all healthcare operators should be continuously trained to increase their knowledge on SB and align diagnoses. It could be also useful to program weekly meetings in which all operators revise some cases blindly extracted from the internal database. This approach could improve inter- and intra-reliability.

The scientific literature describes that “a recent systematic review of perinatal death classification systems reported that 81 new or modified classification systems were used between 2009 and 2014 across 40 countries” [16]. This trend is not changed in the last years. For this reason, consensus studies – as the one proposed by Wojcieszek et al. – should be undertaken in order to make stricter the approach to SB diagnosis, reducing the diffusion of classifications that are not object of extensive scientific review.

Limitation and future perspectives

Limitations of the present study are related to its retrospective nature. In addition, the results reflected the specific characteristics of the population from whom the sample came from. This can limit the applicability of studies’ considerations to other populations and the comparison of results. These limitations suggest the need for a uniform approach to this field. International agencies and/or organizations should propose and organize supranational studies in order to clarify which and when specific SB classification systems should be used. This approach can solve the numerous contradictions among the different articles available in the scientific literature.

Conclusions

The present study supports that there is not a significant difference between ReCoDe and ICD-PM classifications in minimizing unexplained/unspecified cases. Comparison of this data with other studies was difficult as: there are few studies in which ReCoDe and ICD-PM were compared; there are differences in populations from whom studies’ samples come from; quality/quantity of information available for each SB are different for each study.

Inter- and intra-rater agreements were low for both ReCoDe and ICD-PM. For this reason, the authors proposed some suggestions such as the implementation of specific guidelines and illustrative case reports to easily solve interpretation issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Marta Proietto and Dr. Barbara Abenante.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

References

1. UNICEF. A Neglected Tragedy The global burden of stillbirths [Online] 2020. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/a-neglected-tragedy-stillbirth-estimates-report/ [Accessed 4 May 2022].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Heazell, AEP, Siassakos, D, Blencowe, H, Burden, C, Bhutta, ZA, Cacciatore, J, et al.. Stillbirths: economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet 2016;387:604–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00836-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Bernis, LD, Kinney, MV, Stones, W, Hoope-Bender, PT, Vivio, D, Leisher, SH, et al.. Stillbirths: ending preventable deaths by 2030. Lancet 2016;387:703–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00954-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Lupariello, F, Nuzzolese, E, Vella, GD. Causes of death shortly after delivery and medical malpractice claims in congenital high airway obstruction syndrome: review of the literature. Leg Med 2019;40:61–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2019.07.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Vogel, JP, Souza, JP, Mori, R, Morisaki, N, Lumbiganon, P, Laopaiboon, M, et al.. Maternal complications and perinatal mortality: findings of the world health organization multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health. BJOG 2014;121:76–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12633.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Stenberg, K, Axelson, H, Sheehan, P, Anderson, I, Gülmezoglu, AM, Temmerman, M, et al.. Advancing social and economic development by investing in women’s and children’s health: a new global investment framework. Lancet 2014;383:1333–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62231-X.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Smith, LK, Morisaki, N, Morken, NH, Gissler, M, Deb-Rinker, P, Rouleau, J, et al.. An international comparison of death classification at 22 to 25 weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20173324. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3324.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Smith, LK, Hindori-Mohangoo, AD, Delnord, M, Durox, M, Szamotulska, K, Macfarlane, A, et al.. Quantifying the burden of stillbirths before 28 weeks of completed gestational age in high-income countries: a population-based study of 19 European countries. Lancet 2018;392:1639–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31651-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Reinebrant, HE, Leisher, SH, Coory, M, Henry, S, Wojcieszek, AM, Gardener, G, et al.. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth. BJOG 2018;125:212–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14971.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Gardosi, J, Kady, SM, McGeown, P, Francis, A, Tonks, A. Classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe): population based cohort study. BMJ 2005;331:1113–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38629.587639.7C.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Sharma, B, Siwatch, S, Kakkar, N, Suri, V, Raina, A, Aggarwal, N. Classifying stillbirths in a tertiary care hospital of India: international classification of disease-perinatal mortality (ICD-PM) versus cause of death-associated condition (CODAC) system. J Obstet Gynaecol 2021;41:229–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2020.1736016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Reis, AP, Rocha, A, Lebre, A, Ramos, U, Cunha, A. Perinatal mortality classification: an analysis of 112 cases of stillbirth. J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;37:835–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2017.1323854.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Dapoto, F, Facchinetti, F, Monari, F, Pò, G. A comparison of three classification systems for stillbirth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;13:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1839749.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Leisher, SH, Teoh, Z, Reinebrant, H, Allanson, E, Blencowe, H, Erwich, JJ, et al.. Seeking order amidst chaos: a systematic review of classification systems for causes of stillbirth and neonatal death, 2009–2014. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1071-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Leisher, SH, Teoh, Z, Reinebrant, H, Allanson, E, Blencowe, H, Erwich, JJ, et al.. Classification systems for causes of stillbirth and neonatal death, 2009–2014: an assessment of alignment with characteristics for an effective global system. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:269. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1040-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Wojcieszek, AM, Reinebrant, HE, Leisher, SH, Allanson, E, Coory, M, Erwich, JJ, et al.. Characteristics of a global classification system for perinatal deaths: a Delphi consensus study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0993-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Reinebrant, HE, Leisher, SH, Coory, M, Henry, S, Wojcieszek, AM, Gardener, G, et al.. Making stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported causes of stillbirth. BJOG 2018;125:212–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14971.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Vergani, P, Cozzolino, S, Pozzi, E, Cuttin, MS, Greco, M, Ornaghi, S, et al.. Identifying the causes of stillbirth: a comparison of four classification systems. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:319.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.098.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. WHO. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period: ICD-PM [Online] 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249515/9789241549752-eng.pdf [Accessed 4 May 2022].Suche in Google Scholar

20. Watson, PF, Petrie, A. Method agreement analysis: a review of correct methodology. Theriogenology 2010;73:1167–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.01.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Ranganathan, P, Pramesh, CS, Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: measures of agreement. Perspect Clin Res 2017;8:187–91. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_123_17.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Viera, AJ, Garrett, JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Flenady, V, Frøen, JF, Pinar, H, Torabi, R, Saastad, E, Guyon, G, et al.. An evaluation of classification systems for stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-24.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Nappi, L, Trezza, F, Bufo, P, Riezzo, I, Turillazzi, E, Borghi, C, et al.. Classification of stillbirths is an ongoing dilemma. J Perinat Med 2016;44:837–43. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2015-0318.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Maducolil, MK, Abid, H, Lobo, RM, Chughtai, AQ, Afzal, AM, Saleh, HAH, et al.. Risk factors and classification of stillbirth in a Middle Eastern population: a retrospective study. J Perinat Med 2018;46:1022–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2017-0274.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Dase, E, Wariri, O, Onuwabuchi, E, Alhassan, JAK, Jalo, I, Muhajarine, N, et al.. Applying the WHO ICD-PM classification system to stillbirths in a major referral centre in Northeast Nigeria: a retrospective analysis from 2010 to 2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:383. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03059-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Gulati, N, Mackie, FL, Cox, P, Marton, T, Heazell, A, Morris, RK, et al.. Cause of intrauterine and neonatal death in twin pregnancies (CoDiT): development of a novel classification system. BJOG 2020;127:1507–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16291.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Settatree, RS, Watkinson, M. Classifying perinatal death: experience from a regional survey. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;100:110–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15204.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Galan-Roosen, AED, Kuijpers, JC, Straaten, PJVD, Merkus, JM. Fundamental classification of perinatal death. Validation of a new classification system of perinatal death. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002;103:30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00023-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Holt, J, Vold, IN, Odland, JO, Førde, OH. Perinatal deaths in a Norwegian county 1986–96 classified by the Nordic-Baltic perinatal classification: geographical contrasts as a basis for quality assessment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:107–12. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079002107.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Korteweg, FJ, Gordijn, SJ, Timmer, A, Erwich, JJ, Bergman, KA, Bouman, K, et al.. The Tulip classification of perinatal mortality: introduction and multidisciplinary inter-rater agreement. BJOG 2006;113:393–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00881.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Chan, A, King, JF, Flenady, V, Haslam, RH, Tudehope, DI. Classification of perinatal deaths: development of the Australian and New Zealand classifications. J Paediatr Child Health 2004;40:340–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00398.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Francesco Lupariello et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Preventing stillbirth: risk factors, case reviews, care pathways

- Managing stillbirth: taking care to investigate the cause and provide care for bereaved families

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Spatial dynamics of fetal mortality and the relationship with social vulnerability

- Stillbirth occurrence during COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based prospective study

- The effect of the Covid pandemic and lockdown on stillbirth rates in a South Indian perinatal centre

- Stillbirths preceded by reduced fetal movements are more frequently associated with placental insufficiency: a retrospective cohort study

- The prevalence of and risk factors for stillbirths in women with severe preeclampsia in a high-burden setting at Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

- Surveillance and Prevention

- Perinatal mortality audits and reporting of perinatal deaths: systematic review of outcomes and barriers

- Stillbirth diagnosis and classification: comparison of ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems

- Facility-based stillbirth surveillance review and response: an initiative towards reducing stillbirths in a tertiary care hospital of India

- Impact of introduction of the growth assessment protocol in a South Indian tertiary hospital on SGA detection, stillbirth rate and neonatal outcome

- Evaluating the Growth Assessment Protocol for stillbirth prevention: progress and challenges

- Prospective risk of stillbirth according to fetal size at term

- Understanding the Pathology of Stillbirth

- Placental findings in singleton stillbirths: a case-control study from a tertiary-care center in India

- Abnormal placental villous maturity and dysregulated glucose metabolism: implications for stillbirth prevention

- Comparison of prenatal central nervous system abnormalities with postmortem findings in fetuses following termination of pregnancy and clinical utility of postmortem examination

- Cardiac ion channels associated with unexplained stillbirth – an immunohistochemical study

- Viral infections in stillbirth: a contribution underestimated in Mexico?

- Audit and Bereavement Care

- Investigation and management of stillbirth: a descriptive review of major guidelines

- Delivery characteristics in pregnancies with stillbirth: a retrospective case-control study from a tertiary teaching hospital

- Perinatal bereavement care during COVID-19 in Australian maternity settings

- Beyond emotional support: predictors of satisfaction and perceived care quality following the death of a baby during pregnancy

- Stillbirth aftercare in a tertiary obstetric center – parents’ experiences

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorials

- Preventing stillbirth: risk factors, case reviews, care pathways

- Managing stillbirth: taking care to investigate the cause and provide care for bereaved families

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Spatial dynamics of fetal mortality and the relationship with social vulnerability

- Stillbirth occurrence during COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based prospective study

- The effect of the Covid pandemic and lockdown on stillbirth rates in a South Indian perinatal centre

- Stillbirths preceded by reduced fetal movements are more frequently associated with placental insufficiency: a retrospective cohort study

- The prevalence of and risk factors for stillbirths in women with severe preeclampsia in a high-burden setting at Mpilo Central Hospital, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

- Surveillance and Prevention

- Perinatal mortality audits and reporting of perinatal deaths: systematic review of outcomes and barriers

- Stillbirth diagnosis and classification: comparison of ReCoDe and ICD-PM systems

- Facility-based stillbirth surveillance review and response: an initiative towards reducing stillbirths in a tertiary care hospital of India

- Impact of introduction of the growth assessment protocol in a South Indian tertiary hospital on SGA detection, stillbirth rate and neonatal outcome

- Evaluating the Growth Assessment Protocol for stillbirth prevention: progress and challenges

- Prospective risk of stillbirth according to fetal size at term

- Understanding the Pathology of Stillbirth

- Placental findings in singleton stillbirths: a case-control study from a tertiary-care center in India

- Abnormal placental villous maturity and dysregulated glucose metabolism: implications for stillbirth prevention

- Comparison of prenatal central nervous system abnormalities with postmortem findings in fetuses following termination of pregnancy and clinical utility of postmortem examination

- Cardiac ion channels associated with unexplained stillbirth – an immunohistochemical study

- Viral infections in stillbirth: a contribution underestimated in Mexico?

- Audit and Bereavement Care

- Investigation and management of stillbirth: a descriptive review of major guidelines

- Delivery characteristics in pregnancies with stillbirth: a retrospective case-control study from a tertiary teaching hospital

- Perinatal bereavement care during COVID-19 in Australian maternity settings

- Beyond emotional support: predictors of satisfaction and perceived care quality following the death of a baby during pregnancy

- Stillbirth aftercare in a tertiary obstetric center – parents’ experiences