Abstract

During the last decade a number of innovative treatments including gene therapies have been approved for the treatment of monogenic inherited diseases. For some neuromuscular diseases these approaches have dramatically changed the course of the disease. For others relevant challenges still remain and require disease specific approaches to overcome difficulties related to the immune response and the efficient transduction of target cells. This review provides an overview of the current development status of mutation specific treatments for neuromuscular diseases and concludes with on outlook on future developments and perspectives.

Introduction

During the last decade several mutation specific treatments for monogenetic neuromuscular diseases have been approved or are in advanced stages of clinical development. These treatments include approaches that modify the splicing or translation of mRNA or introduce additional genetic material. Somatic gene therapy is defined as the addition, removal, or modification of genetic information in a patient’s somatic cells for the purpose of treating or preventing disease. For the treatment of neuromuscular diseases, gene augmentation or gene addition is currently the most advanced modality. This therapy adds a functional copy of the defective gene to facilitate production of the target protein. Beyond these first-generation gene therapies, gene editing technologies are enabling an entirely new modality for treatments based on precise modification of human genome sequences. These technologies are only currently beginning to be tested clinically [1].

Viral vectors are the most frequently used agents for gene therapy owing their capabilities to deliver many copies of the therapeutic gene to the target cells. Among the most commonly used types are adenoviral vectors, retroviral vectors, lentiviral vectors and adeno-associated vectors. Lentiviral vectors have the capability to integrate their genetic information into the genome of the target cell, while adeno-associated vectors do no integrate into the genome of the target cells. Instead, the genetic information remains in the nucleus as an episome. These vectors can thus express therapeutic genes without changing the genome in host cells, but their use is mainly limited to non-dividing cells.

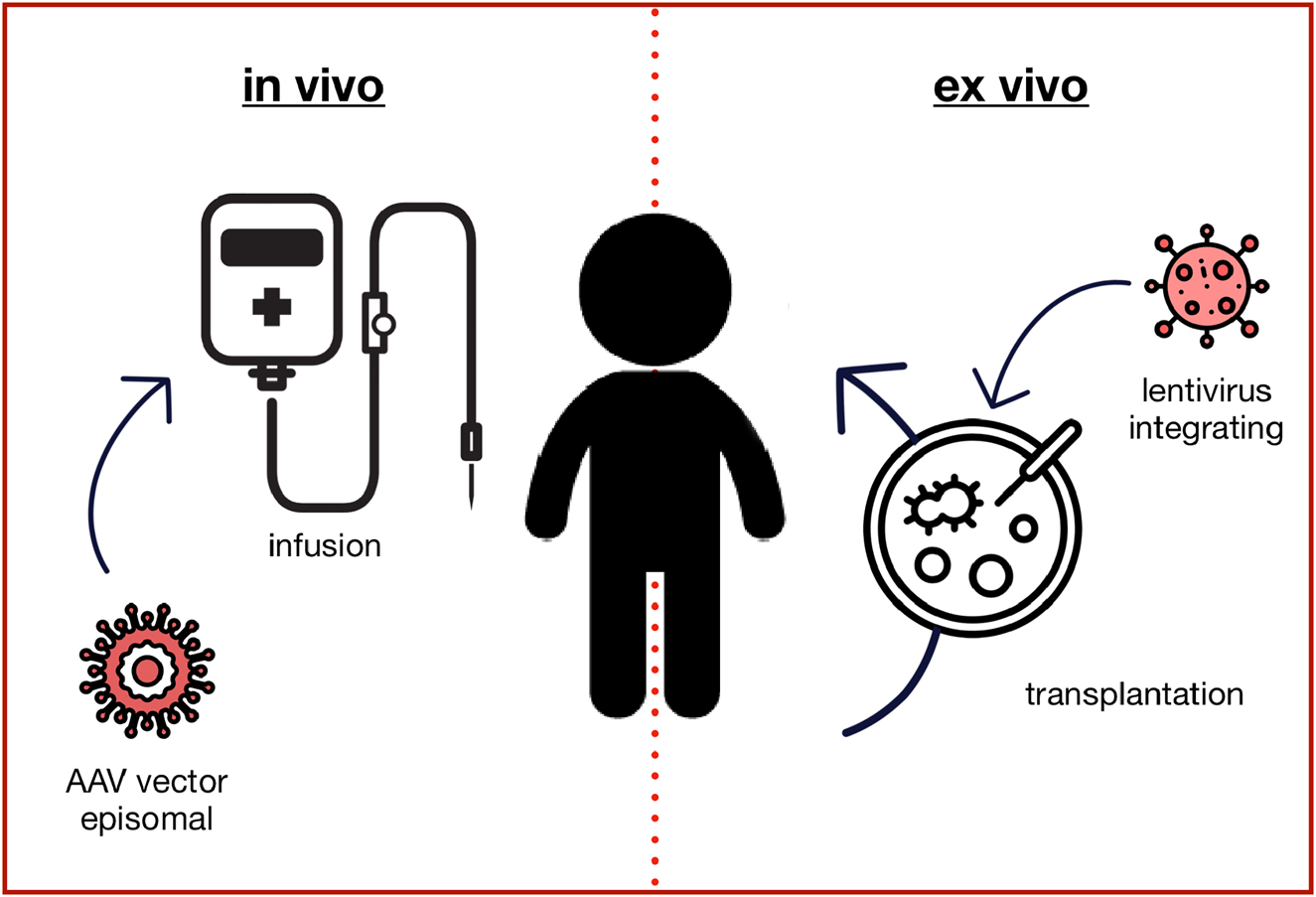

Gene transfer can be performed ex vivo or in vivo (Figure 1). The most advanced use of ex vivo gene therapy is the modification of hematopoietic stem cells to treat inherited diseases such as thalassemia using lentiviral vectors. The in vivo approach, mostly based on adeno associated vectors (AAV), is currently used for the treatment of neuromuscular diseases, retinopathies or haemophilia [2].

Gene augmentation therapy. The in vivo approach typically uses adeno-associated virus (AAV) based vectors to transduce the target cells with a fully functional copy of the mutated gene, which is not integrated into the genome but remains in the nucleus as an episome. Ex vivo gene augmentation therapy refers to the process of removing specific cells from the body (e.g. hematopoietic stem cells), which are genetically altered outside the body and then transplanted back into the patient. Lentiviral vectors typically integrate the genetic information into the genome, so that it is passed to all daughter cells.

Key limitations of AAV-based gene therapies include the immune response to gene delivery vectors and to products of the foreign transgene. These reactions often require a prophylactic or reactive immunomodulatory treatment. Some patients are currently excluded from AAV-based gene therapies due to pre-existing antibodies to the vector capsid.

This paper will review the current development status of innovative and mutation specific treatments for neuromuscular diseases and discuss the implications for diagnosis and counselling of affected patients and their families.

Therapeutic approaches for neuromuscular diseases

Spinal muscular atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by biallelic mutations of the SMN1 gene. The resulting reduction of survival motor neuron (SMN) protein production mainly affects spinal motoneurons and leads to a progressive loss of muscle strengths. The clinical phenotype associated with SMA covers a broad spectrum of disease severity from SMA type 1 with onset during the first six months of life to cases with onset during later childhood or adolescence (SMA types 2, 3 and 4). The main reason for the differences in disease severity between patients is the number of SMN2 gene copies. SMN2 is a nearly identical gene located next to SMN1, which also produces SMN protein. However, due to a single nucleotide exchange that affects the splicing, the production of functional protein is reduced to about 10% compared to SMN1. While SMN2 has no relevance in healthy humans, it serves as a back-up gene in patients with SMA and can partially rescue the phenotype. Higher SMN2 gene copy numbers are thus associated with a milder phenotype. Two SMN2 copies are most prevalent in the population and are typically associated with the severe phenotype of SMA type 1. Without treatment patients with SMA type 1 die within the first two years of life or require permanent ventilation due to severe muscle weakness [3, 4].

Nusinersen was the first drug that has been approved for the treatment of all types of SMA. It is an antisense oligonucleotide that specifically modifies the splicing of SMN2 and leads to an increase of SMN protein production. As nusinersen does not cross the blood-brain barrier it requires repeated lumbar punctures every four months for intrathecal administration. Double-blind, sham-controlled trials have shown a clear benefit compared to the control group in infants with SMA type 1 and children with SMA type 2, respectively [5, 6]. Very recently, risdiplam has been approved as the second splicing modifier for the treatment of SMA. In contrast to nusinersen, risdiplam is a small molecule that crosses the blood-brain barrier and can be administered orally. In Europe it has been approved for the treatment of SMA patients aged two months and older [7].

The gene therapy approach for the treatment of SMA makes use of an adeno-associated viral vector type 9 (AAV9) to introduce a functional copy of the SMN1 gene. Onasemnogene abeparvovec is administered through a single intravenous infusion. Based on open-label clinical trials in infants the drug has received FDA approval for the treatment of patients with SMA up to the age of two years. For Europe, EMA has approved onasemnogene abeparvovec for the treatment of patients with up to three SMN2 copies without defining a clear age or weight limit. As the total dose used is proportional to the body weight and clinical trial experience is limited to infants, there are ongoing discussions about the potential use of the treatment in older children [8]. According to the product information it is recommended to use an immunosuppressive treatment with prednisolone starting on the day before administration for at least four weeks. Most commonly observed side effects include increase of transaminases and thrombocytopenia.

There are no randomized trials comparing the different treatments for SMA and cross-study comparison is difficult due to distinct inclusion criteria and baseline characteristics. However, all studies have shown that early initiation of treatment is most relevant to achieve best outcome. As most patients with SMA do not show any symptoms during the first weeks of life, some studies have explored the pre-symptomatic initiation of treatment and shown that this can facilitate almost normal motor development for many patients [9]. As a consequence newborn screening for SMA has been explored in several pilot projects and is introduced in an increasing number of countries [10, 11].

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common neuromuscular disease during childhood. DMD is caused by mutations of the dystrophin gene on the X-chromosome. Due to the X-linked inheritance, DMD mainly affects boys and leads to a progressive loss of muscle strength. First symptoms, such as difficulties with climbing stairs or standing up from the floor, are typically noticed between two and four years of age. The progressive course of the disease leads to loss of ambulation between 10 and 14 years of age and respiratory failure during adolescence or early adulthood. In addition, most patients develop a dilative cardiomyopathy, which contributes to early mortality. In DMD the lack of the dystrophin protein causes disintegration of a membrane associated protein complex, which leads to cell death and replacement of muscle tissue by fat and fibrous tissue. Creatine kinase in serum, a marker of muscle necrosis, is invariably markedly increased from birth and serves a convenient screening marker for the disease. Underlying mutations include deletions or duplications of one or several exons of the dystrophin gene in about two thirds of cases and smaller mutations affecting only one or a few nucleotides in the remaining cases [12].

One treatment approach is the use of antisense oligonucleotides which bind to the splicing site of a specific exon and thus lead to so-called “exon-skipping”. If used in appropriate patients the skipping of an additional exon can help to restore the reading frame and thus allow for the production of partially functional dystrophin protein. Some of the exon skipping products have been approved by the FDA based on increased production of dystrophin observed in clinical trials. However, as clinical efficacy has not been proven convincingly, these drugs are currently not approved in Europe [13].

Ataluren is a specific treatment for premature termination codon (nonsense) mutations, which account for about of 10% of the DMD cases. Although the primary endpoint was not met in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, subgroup analysis showed lesser decline in the treatment group compared to the placebo group [14]. Ataluren has been approved in Europe for the treatment of ambulant patients with nonsense mediated DMD, who are at least two years old.

A major limitation for the use of gene therapy for the treatment of DMD is the size of the dystrophin gene which exceeds by far the packaging capacity of AAV-based vectors. One possible solution is the construction of truncated forms of the dystrophin gene, which contain the minimal functional regions of the protein. Several of these micro- or mini-dystrophins a currently in clinical development using AAV-vector based gene therapy [15]. Due to the limitations of this traditional gene augmentation therapy, genome editing is also explored for the treatment of DMD. In most cases these strategies are designed to change a DMD out-of-frame mutation into an in-frame mutation, which is associated with the milder phenotype of Becker muscular dystrophy. Currently, genome editing technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 are studied in DMD animal models [16].

Myotubular myopathy

X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM) is caused by mutations of the myotubularin 1 gene (MTM1) located on the X-chromosome. The severe form of XLMTM, which is also the most common form, is characterized by severe muscle weakness, ophthalmoplegia and respiratory insufficiency from birth. Reduced fetal movement and polyhydramnios often indicate prenatal onset. Nearly all patients require respiratory support at birth and the mortality is about 50% during the first years of life. Most patients who survive require tracheostomy [17].

An open label treatment study in 12 patients described improvements in motor and respiratory function after AAV8 based gene therapy including weaning from artificial ventilation in a significant number of patients [18]. However, later three children who had received a higher dose of this gene therapy died from fatal hepatic dysfunction and sepsis [19]. It is assumed that this might have been related to pre-existing hepatobiliary disease, which had been reported in XLMTM. The use of the therapy has therefore been temporarily stopped.

Clinical implications and future developments

Mutation specific treatments and gene therapy have reached clinical development and clinical practice for a number of neuromuscular diseases. However, treatment strategies, clinical efficacy and safety profiles can be very different from disease to disease and might even be mutation specific. While treatment of SMA with splicing modifiers or gene therapy has already shown remarkable benefit, treatment of other neuromuscular diseases might be more complex and still requires additional research.

Treatment of SMA is particularly effective when initiated in the pre-symptomatic phase and the disease should ideally be diagnosed through newborn screening or even prenatally. However, if diagnosed in this stage, counselling is still challenging. The prognosis for SMA type 1 has changed from an almost inevitably lethal disease to long term survival without respiratory support and close to normal motor development. Nevertheless, the use of splicing modifiers requires lifelong treatment either orally or by regular intrathecal injection and AAV-based gene therapy is a one-time treatment, but it is not yet known if the efficacy might decline after several years. Thus, prognosis is potentially very positive for the first years of life but cannot always be guaranteed into adulthood.

For other neuromuscular diseases the future impact of innovative treatments is even more difficult to predict. The modification of vectors and gene constructs might help to reduce immune response and increase transduction of target cells. For some diseases gene augmentation therapy might not be sufficient and gene editing technologies like CRISPR might be needed to correct or modify existing genetic information. In some pathologies post-natal treatment might already be too late due to irreversible prenatal damage. In these cases, in utero gene therapy can be discussed. However, this is associated with new challenges such as potential transduction of maternal cells or immune response of the mother.

In conclusion, it is very likely that gene therapies will be used for an increasing number of diseases during the coming years. However, due to the complexities of individual diseases and the associated host responses, it is not possible to predict future breakthroughs or setbacks. Nevertheless, these new developments will not only be of interest for a small number of experts, but will be of increasing relevance for the whole medical field.

Funding source: EU

Award Identifier / Grant number: 101034427

Acknowledgments

JK is member of the executive committee of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases (EURO-NMD).

-

Research funding: JK receives support from the EU for the SCREEN4CARE project (2021–2026, EU-project # 101034427).

-

Author contributions: Single author contribution.

-

Competing interests: JK has received compensations from Biogen, Novartis, Pfizer, PTC, and Roche for consultation/educational activities and/or research projects.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

References

1. Bulaklak, K, Gersbach, CA. The once and future gene therapy. Nat Commun 2020;11:5820. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19505-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Kirschner, J, Cathomen, T. Gentherapien bei monogenen Erbkrankheiten: Chancen und Herausforderungen. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020;117:878–85.Search in Google Scholar

3. Schorling, DC, Pechmann, A, Kirschner, J. Advances in treatment of spinal muscular atrophy – new phenotypes, new challenges, new implications for care. J Neuromuscul Dis 2020;7:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-190424.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Wirth, B. Spinal muscular atrophy: in the challenge lies a solution. Trends Neurosci 2021;44:306–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.11.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Finkel, RS, Mercuri, E, Darras, BT, Connolly, AM, Kuntz, NL, Kirschner, J, et al.. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1723–32. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1702752.Search in Google Scholar

6. Mercuri, E, Darras, BT, Chiriboga, CA, Day, JW, Campbell, C, Connolly, AM, et al.. Nusinersen versus sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med 2018;378:625–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1710504.Search in Google Scholar

7. Dhillon, S. Risdiplam: first approval. Drugs 2020;80:1853–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01410-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Kirschner, J, Butoianu, N, Goemans, N, Haberlova, J, Kostera-Pruszczyk, A, Mercuri, E, et al.. European ad-hoc consensus statement on gene replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020;28:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.07.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. De Vivo, DC, Bertini, E, Swoboda, KJ, Hwu, WL, Crawford, TO, Finkel, RS, et al.. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord 2019;29:842–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2019.09.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Dangouloff, T, Vrscaj, E, Servais, L, Osredkar, D, Group, SNWS. Newborn screening programs for spinal muscular atrophy worldwide: where we stand and where to go. Neuromuscul Disord 2021;31:574–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2021.03.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Vill, K, Schwartz, O, Blaschek, A, Glaser, D, Nennstiel, U, Wirth, B, et al.. Newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy in Germany: clinical results after 2 years. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021;16:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01783-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Birnkrant, DJ, Bushby, K, Bann, CM, Apkon, SD, Blackwell, A, Brumbaugh, D, et al.. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular, rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal and nutritional management. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:251–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30024-3.Search in Google Scholar

13. Dzierlega, K, Yokota, T. Optimization of antisense-mediated exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Gene Ther 2020;27:407–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-020-0156-6.Search in Google Scholar

14. McDonald, CM, Campbell, C, Torricelli, RE, Finkel, RS, Flanigan, KM, Goemans, N, et al.. Ataluren in patients with nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy (ACT DMD): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31611-2.Search in Google Scholar

15. Mendell, JR, Al-Zaidy, SA, Rodino-Klapac, LR, Goodspeed, K, Gray, SJ, Kay, CN, et al.. Current clinical applications of in vivo gene therapy with AAVs. Mol Ther 2021;29:464–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Chemello, F, Bassel-Duby, R, Olson, EN. Correction of muscular dystrophies by CRISPR gene editing. J Clin Invest 2020;130:2766–76. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci136873.Search in Google Scholar

17. Graham, RJ, Muntoni, F, Hughes, I, Yum, SW, Kuntz, NL, Yang, ML, et al.. Mortality and respiratory support in X-linked myotubular myopathy: a RECENSUS retrospective analysis. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:332–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-317910.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Audentes, A. Therapeutics presents new positive data from ASPIRO, the clinical trial evaluating AT132 in patients with X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM). In: The 24th International annual congress of the World Muscle Society San Francisco: Business Wire; 2019. Available from: https://www.audentestx.com/press_release/audentes-therapeutics-presents-new-positive-data-aspiro-clinical/.Search in Google Scholar

19. Paulk, N. Gene therapy: it’s time to talk about high-dose AAV 2020. Available from: https://www.genengnews.com/topics/genome-editing/gene-therapy-its-time-to-talk-about-high-dose-aav/.10.1089/gen.40.09.04Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Some historical and general considerations on NIPT – great progress achieved, but we have to proceed with caution

- Articles

- The implementation of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in the Netherlands

- Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): does the practice discriminate against persons with disabilities?

- Moral ambivalence. A comment on non-invasive prenatal testing from an ethical perspective

- Should prenatal screening be seen as ‘selective reproduction’? Four reasons to reframe the ethical debate

- Making use of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): rethinking issues of routinization and pressure

- Do non-invasive prenatal tests promote discrimination against people with Down syndrome? What should be done?

- Non-invasive prenatal diagnostics (NIPD) in the system of medical care. Ethical and legal issues

- Awareness of maternal stress, consequences for the offspring and the need for early interventions to increase stress resilience

- First trimester screening with biochemical markers and ultrasound in relation to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

- Reproductive genetic screening for information: evolving paradigms?

- How genomics is changing the practice of prenatal testing

- Postnatal gene therapy for neuromuscular diseases – opportunities and limitations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Some historical and general considerations on NIPT – great progress achieved, but we have to proceed with caution

- Articles

- The implementation of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in the Netherlands

- Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): does the practice discriminate against persons with disabilities?

- Moral ambivalence. A comment on non-invasive prenatal testing from an ethical perspective

- Should prenatal screening be seen as ‘selective reproduction’? Four reasons to reframe the ethical debate

- Making use of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): rethinking issues of routinization and pressure

- Do non-invasive prenatal tests promote discrimination against people with Down syndrome? What should be done?

- Non-invasive prenatal diagnostics (NIPD) in the system of medical care. Ethical and legal issues

- Awareness of maternal stress, consequences for the offspring and the need for early interventions to increase stress resilience

- First trimester screening with biochemical markers and ultrasound in relation to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

- Reproductive genetic screening for information: evolving paradigms?

- How genomics is changing the practice of prenatal testing

- Postnatal gene therapy for neuromuscular diseases – opportunities and limitations