Abstract

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is often erroneously received as a diagnostic procedure due to its high discriminatory power in the field of fetal trisomy 21 diagnosis (wording: “NIPT replaces amniocentesis”). Already a look at the methodology of NIPT (statistical gene dose comparison of a primarily maternofetal DNA mixture information at selected sites of the genome) easily reveals that NIPT cannot match the gold standard offered by cytogenetic and molecular genetic analysis procedures from the matrix of the entire human genome (origin: vital fetal cells), neither in diagnostic breadth nor in diagnostic depth. In fact, NIPT in fetal medicine in its current stage of development is a selective genetic search procedure, which can be applied in primary (without indication) or secondary (indication-related) screening. Thus, NIPT competes with established search procedures for this field. Here, the combined nuchal translucency (NT) test according to Nicolaides has become the worldwide standard since 2000. The strength of this procedure is its broad predictive power: NT addresses not only the area of genetics, but also the statistically 10 times more frequent structural fetal defects. Thus, NIPT and NT have large overlaps with each other in the field of classical cytogenetics, with slightly different weighting in the fine consideration. However, NIPT without a systematic accompanying ultrasound examination would mean a step back to the prenatal care level of the 1980s. In this respect, additional fine ultrasound should always be required in the professional application of NIPT. NIPT can thus complement NT in wide areas, but not completely replace it.

Introduction

The introduction of Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) into clinical medicine from 2012 was greeted with great acclaim by physicians and patients. There was talk of breakthrough, NIPT replacing amniocentesis, diagnostic testing procedure and much more. However, clinical research over the past eight years has succeeded in painting a more realistic picture of what the NIPT method can actually do, where its opportunities lie, but also its methodological limitations. This also makes it possible to draw a comparison of the value of NIPT with the standard method “combined NT test”, which has been established at this point, that better reflects the real conditions in everyday life.

NIPT is an innovative, sophisticated genetic determination method: it thus stands at the interface between laboratory medicine, genetics, pediatrics, and prenatal medicine. The experience of the last eight years in dealing with NIPT has shown that not only the view of unborn life itself, but also the technical language and medical concepts of these disciplines vary slightly from each other at this point. Therefore, in order to understand each other well beyond our medical specialties, it is essential that we use unambiguous terminology across disciplines. We should also have an unambiguous, clear, common concept about which epidemiological key data characterize the field of prenatal medicine.

Epidemiology of congenital malformations

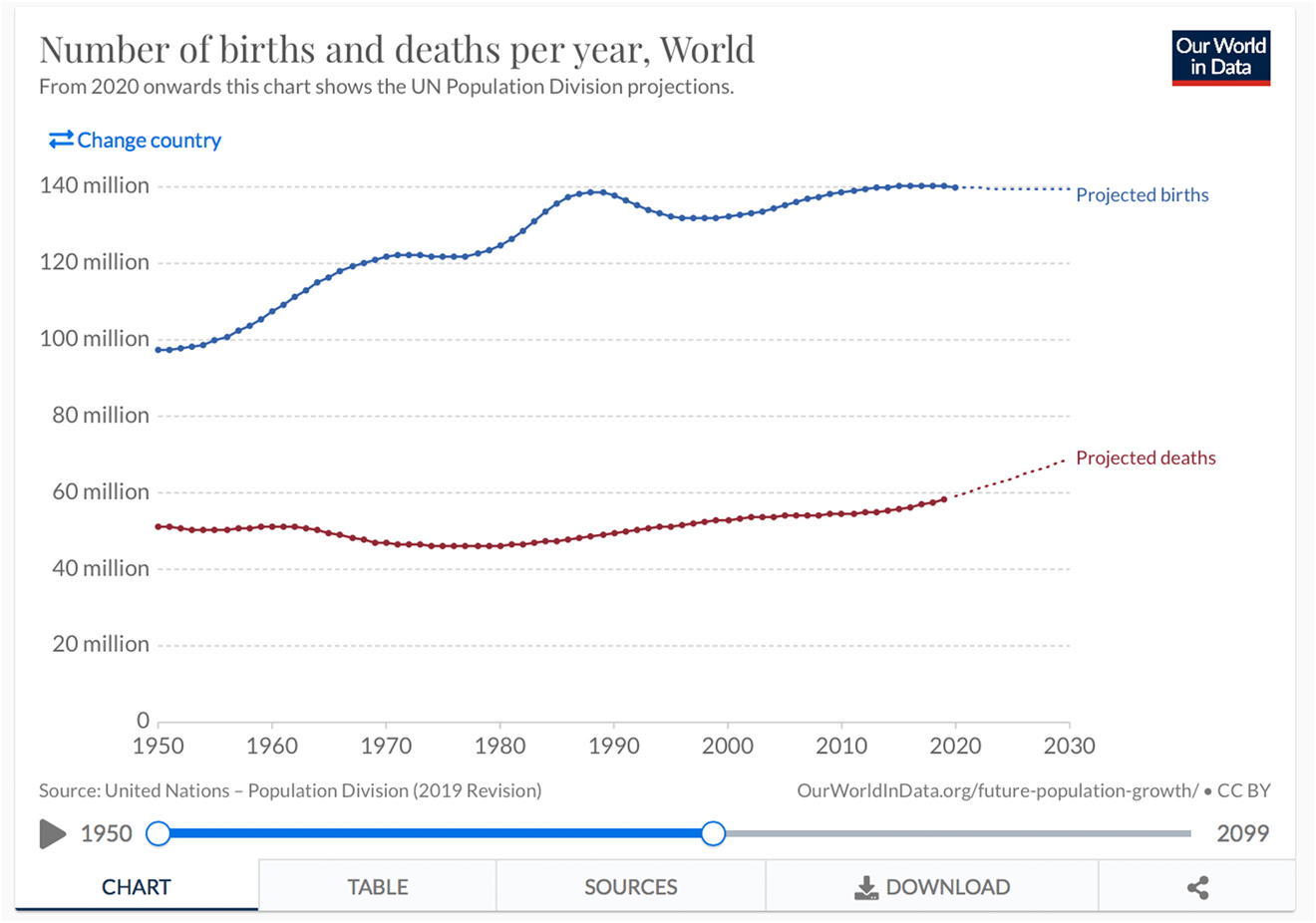

About 130 million children are born worldwide each year (Figure 1) [1]. The UN puts the proportion of children with birth defects at just under 8 million per year [2]. This corresponds to 6% of all births. Of these 8 million, 3.2 million are disabled for life [3]. Disabled children account for a large proportion of pediatric mortality [4]. Over 3.3 million children die annually from congenital defects before reaching the age of five [5]. Interestingly, the rate of congenital anomalies appears to be lower in developed countries: it is approximately 3% in the United States as well as in Germany [6].

Birth rate worldwide 1950–2030 (Source WHO, ourworldindata.org).

The causes of congenital anomalies can be divided etiologically into three groups: The first group is that of genetic causes. Here, it can be further roughly divided into chromosomal disorders and single gene disorders. The next group concerns exogenous teratogenic factors. These include infections, substance deficiencies, substance abuse-toxic factors, diabetes, and in the broadest sense, maternal age. The third group includes cases of unknown cause [7], [8]. This includes structural malformations in the embryonic phase and thus a large proportion of fetal malformations diagnosed prenatally. Quite a few malformations also result from the combination of the above causes: This is the model of multifactorial disease genesis.

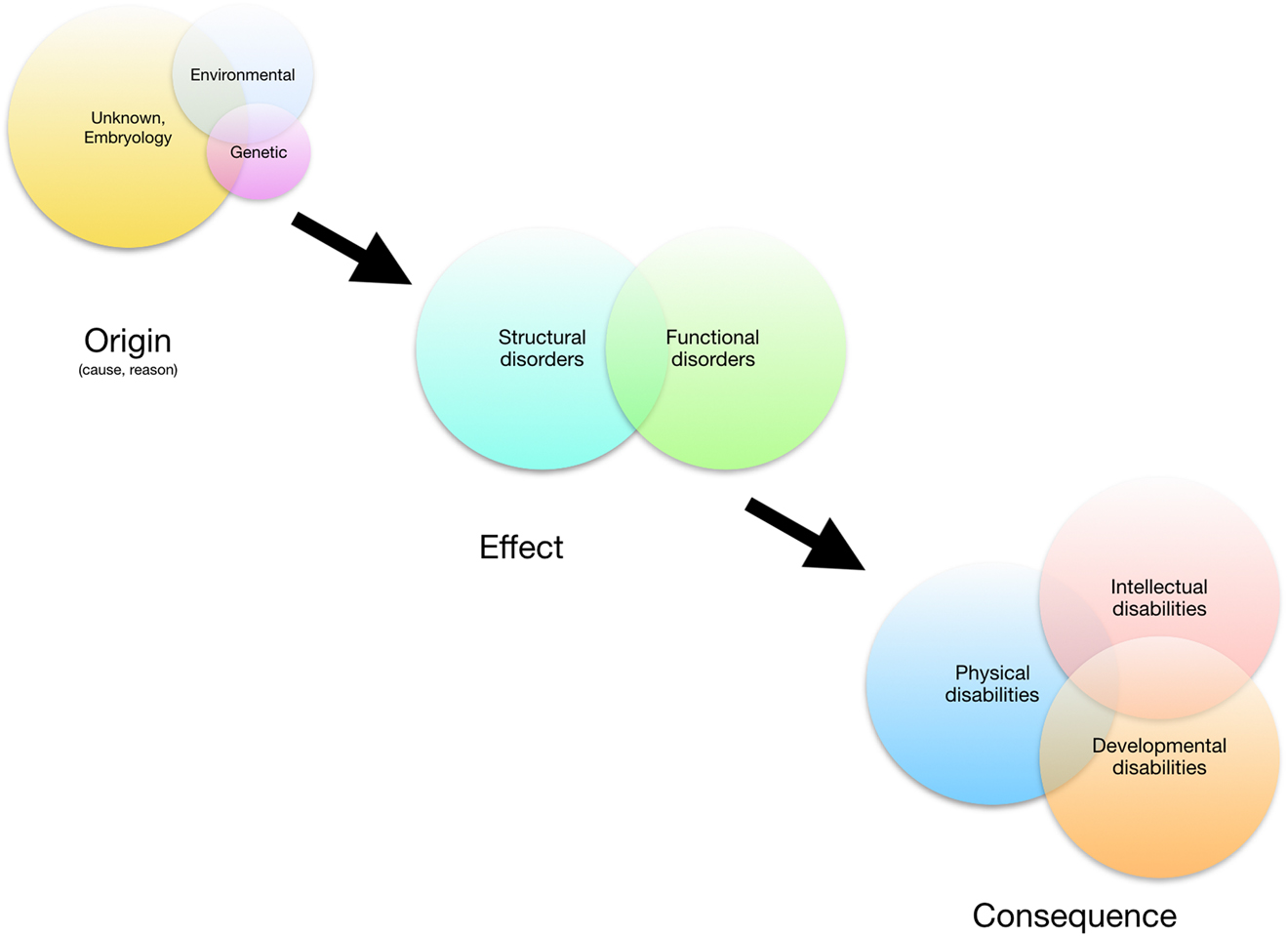

As a result of these acting factors, there may be a disturbance of the structure of the body or its function. Often one causes the other and we observe an overlapping of both forms. As a consequence, these disorders can lead to physical, intellectual and developmental impairments. Due to the mutual dependencies, such impairments are often combined (Figure 2).

Congenital disorders: origin, effect, consequence.

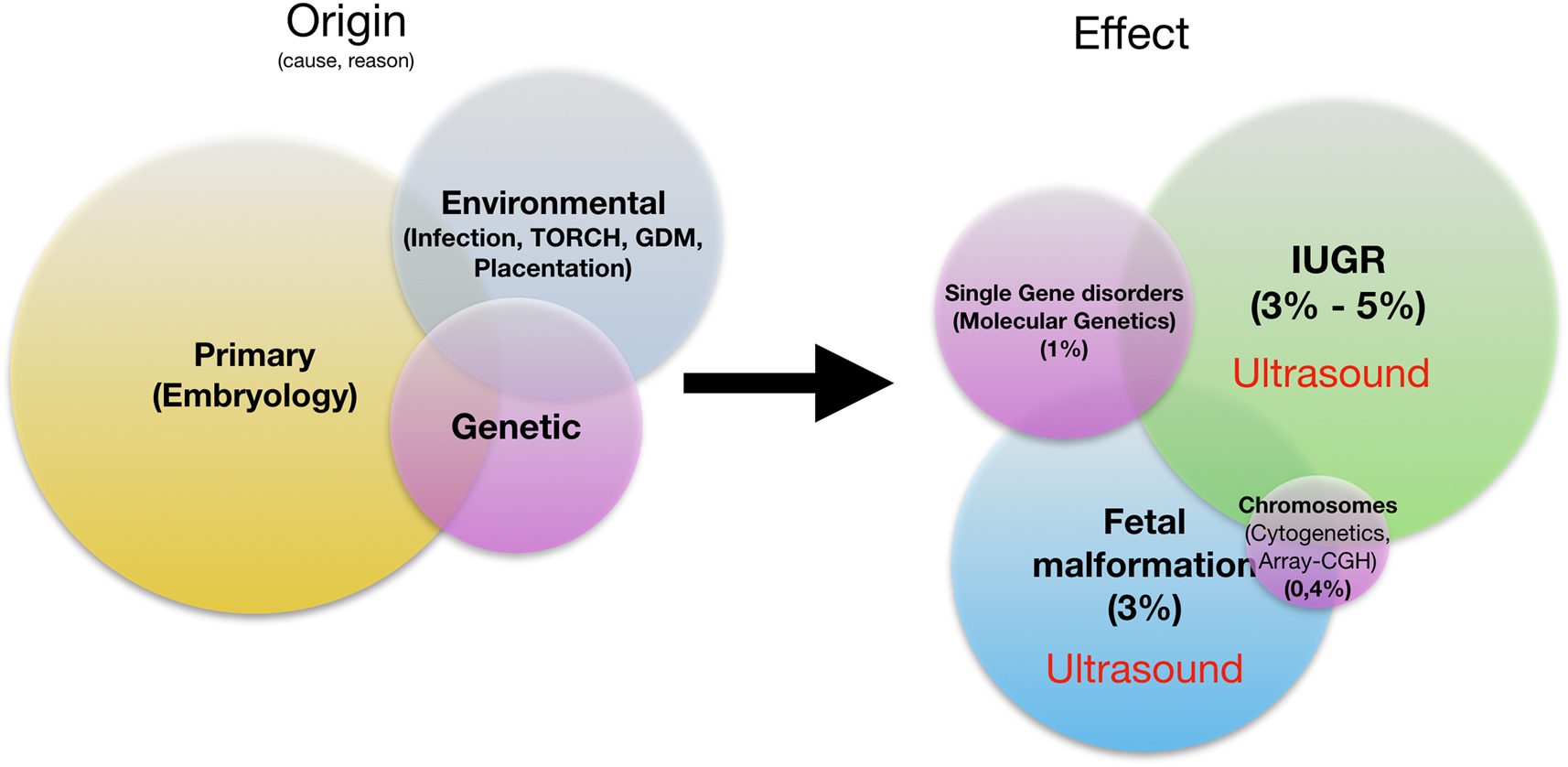

This etiological-taxonomic classification cannot be consistently applied to the prenatal situation: Prenatally, the possibilities are limited to assess the functional impairments that may result from a recognizable structural defect – the view ahead is clouded. Prenatal medicine recognizes three major groupings of fetal disorders: The group of disturbance of fetal structure, the group of genetic defects, and the group of disturbance of growth as an expression of the stability of the maternoplacental axis of supply (Figure 3). Biologically-practically, these three pathological conditions are closely intertwined. They are mutually dependent. Here is the classic example: A fetus with trisomy 21 has a structural heart defect in about 50%. At the same time, his risk of developing growth retardation or placental insufficiency is significantly increased.

Prenatal fetal pathologies: origin, effect. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Conversely, this means for the practical prenatal medical procedure: Whenever the fetus is diagnosed as belonging to one of the three groups of fetal pathologies, simultaneous involvement of the other group of fetal pathologies should be excluded with maximum possible certainty. The more pathology groups the fetus combines, the more probable is the causal presence of a common genetic cause.

Two of these three prenatal pathology groups can be diagnosed authochtonously only by sonography. Even genetic disorders can be detected with high sensitivity by fetal nuchal translucency (NT) measurement and fetal echocardiography.

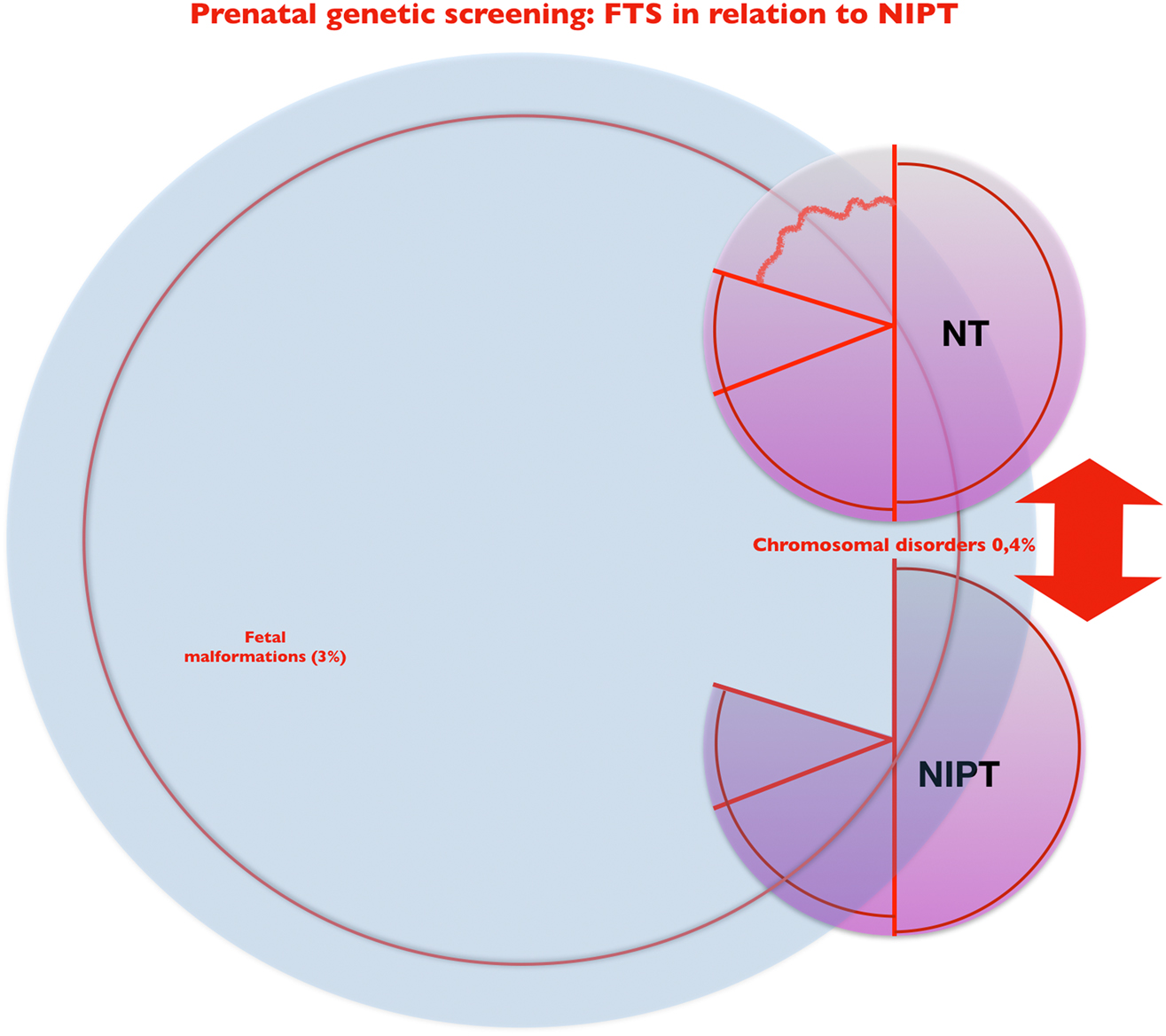

In a clinical weighting, it should be noted that clinically relevant, prognosis-determining structural defects of the fetus generally occur 10 times more frequently than chromosomal disorders. Therefore, the first commandment of prenatal medicine is: No genetics without fetal ultrasound examination!

From the year 2000: combined NT screening

The turn of the millennium saw the introduction of NT measurement [9], [10]. This was initially done as NT-stand alone, then as a combined NT test with pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (Papp-A) and free beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (free ßHCG). This test was initially intended to be genetic only: it yielded unprecedentedly high sensitivities of around 90% for the three classical trisomies [11]. It soon became apparent, moreover, that the combined NT test could also be predictive for rare chromosomal disorders and occasionally for other genetic diseases [12], [13], [14], [15]. Thus, NT already exceeded all expectations in this field. What was not foreseeable to this extent in the early 2000s was the increasingly clear realization that increased NT as a screening method in conjunction with early systematic ultrasound examination could also detect up to 80% of relevant structural malformations [16], [17], [18], [19]. Thus, NT was a door opener toward systematic early sonographic malformation diagnosis between 11 and 14 gestational weeks. It has now established itself as an integral part of a professional approach to the question of fetal health in prenatal centers worldwide [20].

The core of this concept is the application of early fetal echocardiography [21]. This represents the cornerstone of the diagnosis in a holistic health assessment. This is based on the following biological relationship: the heart anatomy is closely linked to the genetic constitution of the unborn child. Genetically healthy fetuses have structurally normal hearts in the vast majority. Genetically diseased fetuses have a high proportion of structural heart defects.

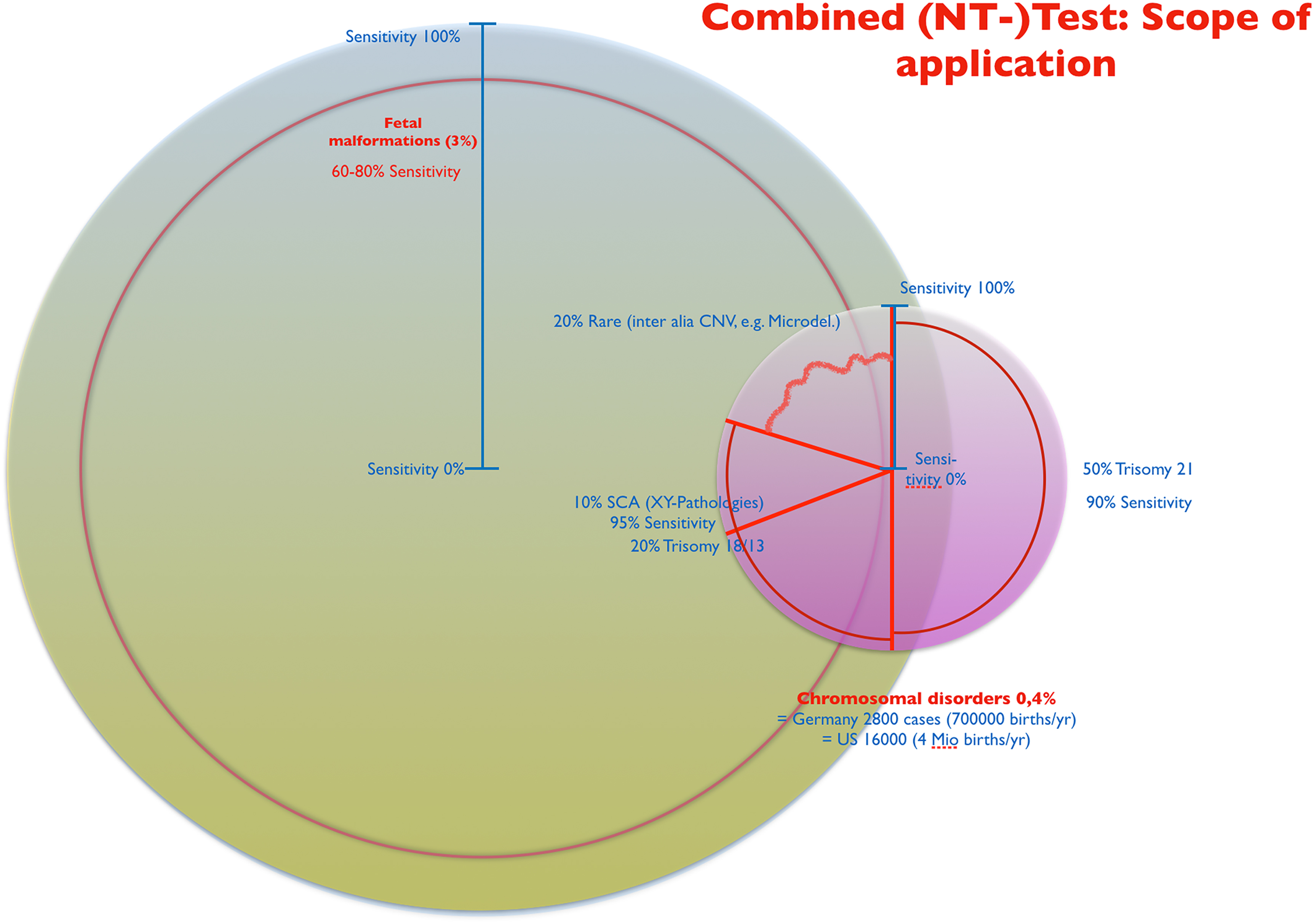

The combined NT test, in conjunction with early malformation exclusion, detects a large proportion of chromosomal defects and simultaneously a large proportion of structural malformations in fetuses at the biologically earliest possible time (completed embryonic phase) (Figure 4). Thus, in a holistic approach, this combined sonographic-biochemical screening procedure was and is the best, most applicable reasonable approach to the regularly recurring question of the mother: Is my child healthy? This question, too, is holistic in nature and goes far beyond considerations of fetal genetics alone.

Combined NT-test: scope of application.

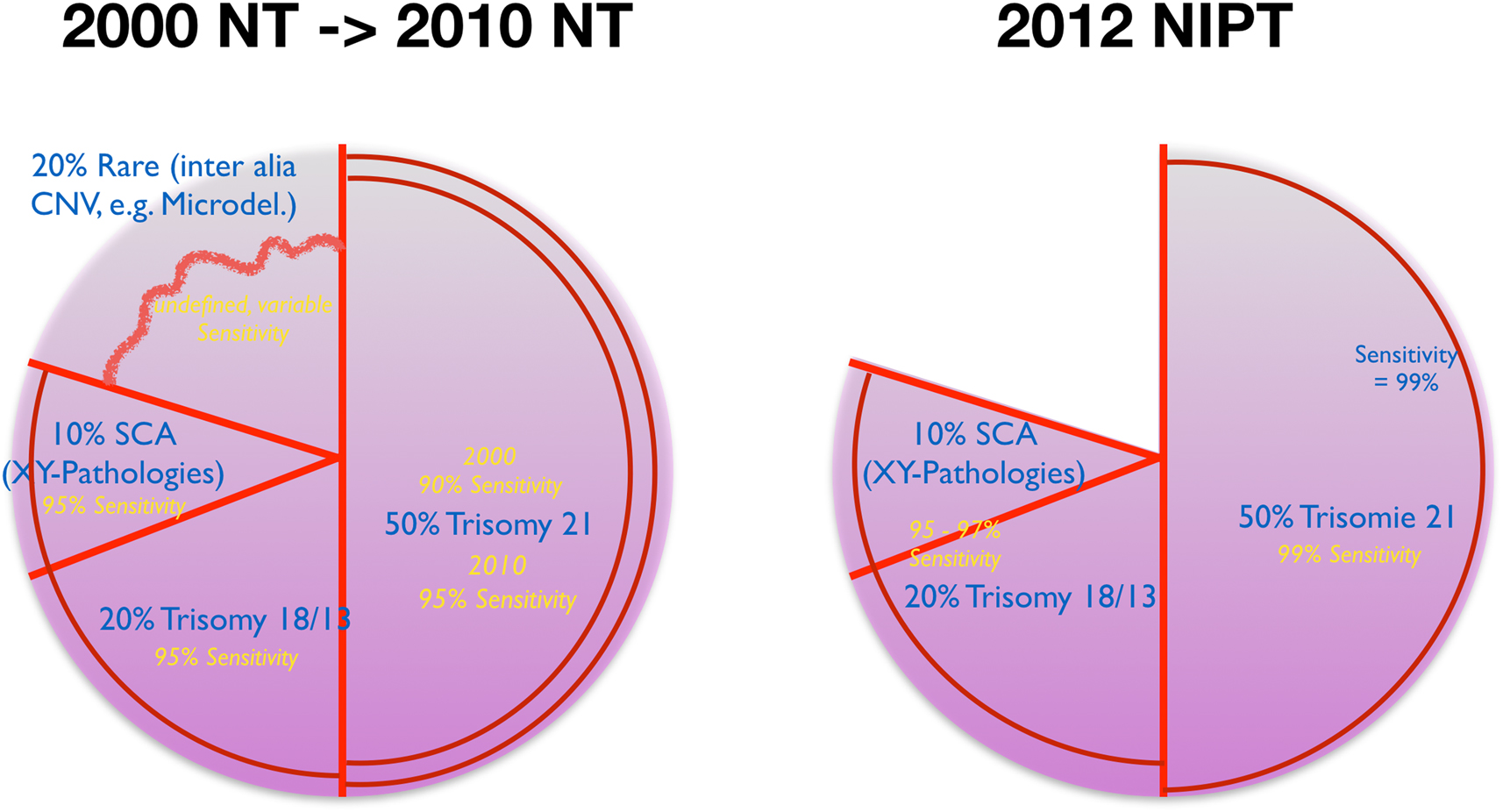

In the years between 2000 and 2012, a systematic, stepwise expansion of NT occurred: by introducing additional sonographic markers, the test sensitivity could be expanded to 95% for trisomy 21 [22], [23], [24].

From 2012: NIPT and combined NT screening

In 2012 NIPT was introduced into prenatal medicine. It has become firmly established worldwide in non-invasive prenatal genetic diagnostics as a robustly applicable search procedure for trisomy 21 [25], [26], [27]. Studies have shown a slight increase in sensitivity in trisomy 21–99% compared to NT at 95% [28], [29]. The detection rates of NIPT in trisomy 18 and 13 range between 90 and 97% and are thus comparable on the level of sensitivity with NT in experienced examiner’s hands [30], [31]. Rare chromosomal anomalies are not addressed by NIPT in its current standard configuration. Therefore, in comparison, the total number of genetic disorders considered, and thus the diagnostic breadth, is lower with NIPT than with the combined NT test. In a comparative outcome analysis of the detection (test sensitivity) of all fetal pathologies (structural malformations and genetic disorders), NIPT without simultaneous application of ultrasound is inferior to the combined NT test (sensitivity) when viewed in this way. The better detection of trisomy 21 with NIPT has slightly shifted the focus of consideration toward trisomy 21 compared with NT (Figure 5).

NIPT and NT: cytogenetic coverage and development.

The actual superiority of NIPT compared to NT [32] is found in the significantly higher discriminatory power of the procedure in trisomy 21 due to the impressive reduction of the false positive rate (type 1 error) and thus increase in specificity. But also the false negative rate (type 2 error) decreases by at least one power of 10 compared to NT. This significantly increases the positive predictive value (PPV) when considering test performance figures for trisomy 21 (Tables 1, 2). Thus, NIPT has the potential to replace NT on the genetic-chromosomal side of a combined sonographic-genetic search strategy between 11 and 14 gestational weeks. This does not affect the potential of NT on the morphological side of this holistic screening concept.

Test performance combined NT-test in T21 – low risk population.

| Test performance T21 combined NT-test | Reality - Outcome | Reality - Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany 800,000 births/year | ||||

| Calculation based upon observational study by Kagan 2008, projected on low risk population (PPV original paper 0.17 in high risk) | Affected by T21 | Not affected by T21 | Sum | |

| Prevalence 1:1,000 | Conspicuous (test-positive) | 739 | 23,976 | 24,715 |

| Unconspicuous (test-negative) | 61 | 775,224 | 775,285 | |

| Sum | 800 | 799,200 | 800,000 | |

|

|

||||

| Sens | 0.924 | |||

| Spec | 0.97 | |||

| PPV | 0.03 | |||

| NPV | 0.999 | |||

| FPR | 0.03 | |||

-

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; FPR, false positive rate; Sens, sensitivity; Spec; specificity.

Test performance NIPT in T21 – low risk population.

| Test performance T21 NIPT transformation calculation from study results w/o effect no call | Reality - Outcome | Reality - Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany 800,000 births/year | ||||

| Model calculation | Affected by T21 | Not affected by T21 | Sum | |

| Prevalence 1:1,000 | Conspicuous (test-positive) | 792 | 320 | 1,112 |

| Unconspicuous (test-negative) | 8 | 798,880 | 798,888 | |

| Sum | 800 | 799,200 | 800,000 | |

|

|

||||

| Sens | 0.99 | |||

| Spec | 0.999 | |||

| PPV | 0.712 | |||

| NPV | 0.999 | |||

| FPR | >0.001 | |||

-

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; FPR, false positive rate; Sens, sensitivity; Spec; specificity.

NIPT for microdeletions

Around 2015, there was an expansion of the spectrum of genetic disorders addressed by NIPT towards microdeletions in professional investigation kits. For the five most common microdeletions (DiGeorge, Cri-du-Chat, Wolf-Hirschhorn, 1p36, Prader-Willi/Angelman), in high-risk collectives, the sensitivity of NIPT is 75% [33] for DiGeorge and over 90% for the others. All disorders have a steeply decreasing disease prevalence starting from DiGeorge with 1:1,000–1:4,000. This has a statistical effect in search procedures such that the false positive rate is relatively high and the PPV is relatively low (5–10%). A high false positive rate means a high unnecessary puncture rate. Thus, NIPT for microdeletions is scientifically-statistically effective in detection, but not efficient in practical prenatal life (cost-benefit consideration). Thus, the efforts of the laboratories, which are quite successful on the marketing side, to give NIPT a broader profile by including microdeletions, come to a dead end medically. This is reflected in the current DEGUM recommendations: The use of NIPT in screening is currently not recommended [34].

NIPT - effect of test failure rate on real test performance in primary screening

One aspect that is often left out of the scientific analyses and marketing strategies of laboratory providers is the everyday reality of NIPT screening in a normal or low-risk population. This is envisaged as a model of care by statutory health insurers in Germany from 2021. Here, a factor comes into play that is usually primarily excluded in study collectives and thus leads to significantly better test performance figures than in prenatal everyday reality. This is the test failure (no-call) rate. Taken into account, this leads to a significant increase in the false positive rate of NIPT in trisomy 21, because a test that is not interpretable even when repeated often results in a puncture with good medical and psychological reasons [35]. Conversely, the increased false positive rate means a significant decrease in the positive predictive value of NIPT for trisomy 21. According to meta-analyses, these effects decrease the test sensitivity of NIPT for trisomy 21 in a normal population to 96%, for trisomy 18–87%, and for trisomy 13–77% [36]. Thus, NIPT screening for trisomy 13 and 18 in the normal population no longer meets the quality criteria that are internationally applied to a screening procedure.

Summary – conclusion

NIPT is a high-performing procedure at the trisomy 21 level for indicated screening in high-risk populations and is superior to the combined NT test, particularly at the level of specificity at this point. Due to the high NPV, an inconspicuous test result at T21 predicts a non-T21 fetus with an extremely high probability. However, non-T21 does not mean genetically healthy or even generally healthy. In this respect, the wording “NIPT replaces amniocentesis” is philosophically-epistemologically and medically-practically incorrect and misleading.

NIPT is thus, from a practical point of view, a highly selective search procedure for trisomy 21. In all other respects, it is at best equivalent to the combined NT test with systematic ultrasound examination in genetic terms. NIPT without systematic ultrasound examination of the fetus means a diagnostic relapse into the 1980s for practical prenatal medicine.

NIPT has thus expanded the spectrum of available diagnostic methods in the practical day-to-day work of prenatal medicine, but has not completely displaced NT: Depending on the individual counseling situation, the expectations of the pregnant women seeking advice, and their economic possibilities, NT and NIPT are currently two valuable search methods in prenatal medicine that differ slightly in their breadth and depth of information (Figure 6).

NIPT and NT – two versions of first-trimester genetic screening with systematic ultrasound: coverage and comparison.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

References

1. University of Oxford: our world in data [Online]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/births-and-deaths-projected-to-2100?tab=table&stackMode=absolute&time=1950.2030®ion=World.Search in Google Scholar

2. Christianson, A, Howson, CP, Modell, B. March of Dimes: Global Report on birth defects. The hidden toll of dying and disabled children. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, White Plains, New York [Online]; 2006. Available from: https://www.marchofdimes.org/global-report-on-birth-defects-the-hidden-toll-of-dying-and-disabled-children-full-report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

3. Lobo, I, Zhaurova, K. Birth defects: causes and statistics. Nat Educ 2008 [Online];1:18. https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/birth-defects-causes-and-statistics-863/.Search in Google Scholar

4. Almli, LM, Ely, DM, Ailes, EC, Abouk, R, Grosse, SD, Isenburg, JL, et al.. Infant mortality attributable to birth defects - United States, 2003–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:25–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6902a1.Search in Google Scholar

5. LJWorld Report: 8 million babies born with birth defects each year [Online]. Available from: https://www2.ljworld.com/news/2006/jan/31/report_8_million_babies_born_birth_defects_each_ye/.Search in Google Scholar

6. Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Update on overall prevalence of major birth defects - Atlanta, Georgia, 1978–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1–5.Search in Google Scholar

7. Tuan, RS. Birth defects: etiology, screening, and detection. Birth Defects Res 2017;109:723–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.1066.Search in Google Scholar

8. Healthychildren.org: congenital abnormalities [Online]. Available from: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/developmental-disabilities/Pages/Congenital-Abnormalities.aspx.Search in Google Scholar

9. Spencer, K, Souter, V, Tul, N, Snijders, R, Nicolaides, KH. A screening program for trisomy 21 at 10–14 weeks using fetal nuchal translucency, maternal serum free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999;13:231–7. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13040231.x.Search in Google Scholar

10. Snijders, RJ, Noble, P, Sebire, N, Souka, A, Nicolaides, KH. UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Fetal Medicine Foundation First Trimester Screening Group. Lancet 1998;352:343–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11280-6.Search in Google Scholar

11. Nicolaides, KH. Screening for fetal aneuploidies at 11 to 13 weeks. Prenat Diagn 2011;31:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.2637.Search in Google Scholar

12. Kagan, KO, Valencia, C, Livanos, P, Wright, D, Nicolaides, KH. Tricuspid regurgitation in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 and Turner syndrome at 11+0 to 13+6 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;33:18–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.6264.Search in Google Scholar

13. Chen, CP. Prenatal sonographic features of fetuses in trisomy 13 pregnancies. IV. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2010;49:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1028-4559(10)60002-2.Search in Google Scholar

14. Wiechec, M, Knafel, A, Nocun, A, Wiercinska, E, Ludwin, A, Ludwin, I. What are the most common first-trimester ultrasound findings in cases of Turner syndrome? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:1632–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1220525.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Sivanathan, J, Thilaganathan, B. Book: genetics for obstetricians and gynaecologists. Chapter: genetic markers on ultrasound scan. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2017;42:64–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.03.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Sonek, J. First trimester ultrasonography in screening and detection of fetal anomalies. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2007;145C:45–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Bromley, B, Shipp, TD, Lyons, J, Navathe, RS, Groszmann, Y, Benacerraf, BR. Detection of fetal structural anomalies in a basic first-trimester screening program for aneuploidy. J Ultrasound Med 2014;33:1737–45. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.33.10.1737.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Iliescu, D, Tudorache, S, Comanescu, A, Antsaklis, P, Cotarcea, S, Novac, L, et al.. Improved detection rate of structural abnormalities in the first trimester using an extended examination protocol. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;42:300–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12489.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Yu, D, Sui, L, Zhang, N. Performance of first-trimester fetal echocardiography in diagnosing fetal heart defects: meta-analysis and systematic review. J Ultrasound Med 2020;39:471–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15123.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Audibert, F, De Bie, I, Johnson, JA, Okun, N, Wilson, RD, Armour, C, et al.. No. 348-joint SOGC-CCMG guideline: update on prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, fetal anomalies, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2017;39:805–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.01.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Becker, R, Wegner, RD. Detailed screening for fetal anomalies and cardiac defects at the 11–13-week scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006;27:613–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.2709.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Matias, A, Gomes, C, Flack, N, Montenegro, N, Nicolaides, KH. Screening for chromosomal abnormalities at 10–14 weeks: the role of ductus venosus blood flow. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998;12:380–4. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12060380.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Maiz, N, Nicolaides, KH. Ductus venosus in the first trimester: contribution to screening of chromosomal, cardiac defects and monochorionic twin complications. Fetal Diagn Ther 2010;28:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1159/000314036.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Cicero, S, Sonek, JD, McKenna, DS, Croom, CS, Johnson, L, Nicolaides, KH. Nasal bone hypoplasia in trisomy 21 at 15–22 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003;21:15–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.19.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Minear, MA, Lewis, C, Pradhan, S, Chandrasekharan, S. Global perspectives on clinical adoption of NIPT. Prenat Diagn 2015;35:959–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4637.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Allyse, M, Minear, MA, Berson, E, Sridhar, S, Rote, M, Hung, A, et al.. Non-invasive prenatal testing: a review of international implementation and challenges. Int J Womens Health 2015;7:113–26. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijwh.s67124.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Benachi, A, Caffrey, J, Calda, P, Carreras, E, Jani, JC, Kilby, MD, et al.. Understanding attitudes and behaviors towards cell-free DNA-based noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT): a survey of European health-care providers. Eur J Med Genet 2020;63:103616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.01.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Palomaki, GE, Deciu, C, Kloza, EM, Lambert-Messerlian, GM, Haddow, JE, Neveux, LM, et al.. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: an international collaborative study. Genet Med 2012;14:296–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.73.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Ashoor, G, Syngelaki, A, Wagner, M, Birdir, C, Nicolaides, KH. Chromosome-selective sequencing of maternal plasma cell-free DNA for first-trimester detection of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:322 e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Kagan, KO, Wright, D, Maiz, N, Pandeva, I, Nicolaides, KH. Screening for trisomy 18 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency, free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:488–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.6123.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Rajs, B, Pasternok, M, Nocun, A, Matyszkiewicz, A, Zietek, D, Rozmus-Warcholinska, W, et al.. Clinical article: screening for trisomy 13 using traditional combined screening versus an ultrasound-based protocol. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021;34:1048–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1623779.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Kagan, KO, Wright, D, Baker, A, Sahota, D, Nicolaides, KH. Screening for trisomy 21 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency thickness, free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;31:618–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.5331.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Schmid, M, Wang, E, Bogard, PE, Bevilacqua, E, Hacker, C, Wang, S, et al.. Prenatal screening for 22q11.2 deletion using a targeted microarray-based cell-free DNA test. Fetal Diagn Ther 2018;44:299–304. https://doi.org/10.1159/000484317.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Kozlowski, P, Burkhardt, T, Gembruch, U, Gonser, M, Kahler, C, Kagan, KO, et al.. DEGUM, OGUM, SGUM and FMF Germany recommendations for the implementation of first-trimester screening, detailed ultrasound, cell-free DNA screening and diagnostic procedures. Ultraschall Med 2019;40:176–93. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0631-8898.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Yaron, Y. The implications of non-invasive prenatal testing failures: a review of an under-discussed phenomenon. Prenat Diagn 2016;36:391–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4804.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Taylor-Phillips, S, Freeman, K, Geppert, J, Agbebiyi, A, Uthman, OA, Madan, J, et al.. Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010002. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Some historical and general considerations on NIPT – great progress achieved, but we have to proceed with caution

- Articles

- The implementation of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in the Netherlands

- Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): does the practice discriminate against persons with disabilities?

- Moral ambivalence. A comment on non-invasive prenatal testing from an ethical perspective

- Should prenatal screening be seen as ‘selective reproduction’? Four reasons to reframe the ethical debate

- Making use of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): rethinking issues of routinization and pressure

- Do non-invasive prenatal tests promote discrimination against people with Down syndrome? What should be done?

- Non-invasive prenatal diagnostics (NIPD) in the system of medical care. Ethical and legal issues

- Awareness of maternal stress, consequences for the offspring and the need for early interventions to increase stress resilience

- First trimester screening with biochemical markers and ultrasound in relation to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

- Reproductive genetic screening for information: evolving paradigms?

- How genomics is changing the practice of prenatal testing

- Postnatal gene therapy for neuromuscular diseases – opportunities and limitations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Some historical and general considerations on NIPT – great progress achieved, but we have to proceed with caution

- Articles

- The implementation of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) in the Netherlands

- Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): does the practice discriminate against persons with disabilities?

- Moral ambivalence. A comment on non-invasive prenatal testing from an ethical perspective

- Should prenatal screening be seen as ‘selective reproduction’? Four reasons to reframe the ethical debate

- Making use of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): rethinking issues of routinization and pressure

- Do non-invasive prenatal tests promote discrimination against people with Down syndrome? What should be done?

- Non-invasive prenatal diagnostics (NIPD) in the system of medical care. Ethical and legal issues

- Awareness of maternal stress, consequences for the offspring and the need for early interventions to increase stress resilience

- First trimester screening with biochemical markers and ultrasound in relation to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

- Reproductive genetic screening for information: evolving paradigms?

- How genomics is changing the practice of prenatal testing

- Postnatal gene therapy for neuromuscular diseases – opportunities and limitations