Nationwide implementation of a decision aid on vaginal birth after cesarean: a before and after cohort study

-

Dorothea M. Koppes

, Merel S. F. van Hees

, Vivienne M. Koenders

Abstract

Objectives

Woman with a history of a previous cesarean section (CS) can choose between an elective repeat CS (ERCS) and a trial of labor (TOL), which can end in a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) or an unplanned CS. Guidelines describe women’s rights to make an informed decision between an ERCS or a TOL. However, the rates of TOL and vaginal birth after CS varies greatly between and within countries. The objective of this study is to asses nation-wide implementation of counselling with a decision aid (DA) including a prediction model, on intended delivery compared to care as usual. We hypothesize that this may result in a reduction in practice variation without an increase in cesarean rates or complications.

Methods

In a multicenter controlled before and after cohort study we evaluate the effect of nation-wide implementation of a DA. Practice variation was defined as the standard deviation (SD) of TOL percentages.

Results

A total of 27 hospitals and 1,364 women were included. A significant decrease was found in practice variation (SD TOL rates: 0.17 control group vs. 0.10 intervention group following decision aid implementation, p=0.011). There was no significant difference in the ERCS rate or overall CS rates. A 21% reduction in the combined maternal and perinatal adverse outcomes was seen.

Conclusions

Nationwide implementation of the DA showed a significant reduction in practice variation without an increase in the rate of cesarean section or complications, suggesting an improvement in equality of care.

Introduction

The worldwide rate of cesarean section (CS) is high and the cohort of women with one previous CS is one of the largest contributors. The rate of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) may be as low as 8% [1]. A successful VBAC is associated with the lowest rate of complications; however, an unsuccessful VBAC, resulting in unplanned CS, carries the greatest risk of adverse outcomes [2]. Careful consideration should therefore be given to the probability of success or failure for each woman [3]. Although in the Netherlands the overall percentage of women selecting to undergo a trial of labor (TOL) is quite high (67%), the rate varies from 48–93% between centers [4], suggesting practice variation. Practice variation is a euphemism for a deviation from normal standards of care. Although some variation in clinical practice is justified, unwarranted variation–“variation that is not explained on the basis of illness, patient risk factors or patient preferences” is common [5]. This can lead to underuse of effective care, overuse of non-beneficial services, and emphasis on physician opinions rather than patient preferences. Unwarranted variation has been linked to suboptimal outcomes and to increased cost for the same outcome (i.e., inefficient care) [5]. The SIMPLE (Sectio IMPLEmentatie) study group has identified barriers and facilitators for optimal cesarean care [6], identifying that most women are not adequately informed of their choices prior to labor due to caregivers’ fear of an increase in CS rates [7]. In response to that finding a decision aid (DA) was developed, containing evidence-based information, including a prediction model [8], [9]. A prospective cohort study showed that implementation of the DA with a prediction model for risk selection reduced unplanned CS rates by 40% and improved the involvement in decision-making, without reducing the VBAC rates [10]. In the current controlled before and after cohort study, we aimed to evaluate the effect of the DA, including a prediction model, on practice variation after nationwide implementation in the Netherlands. We hypothesized that use of this tool would reduce practice variation without resulting in an increase in CS or complication rates.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study involved an analysis of retrospective and prospective data collection to evaluate the effect of nationwide DA use. This study is a continuation of the SIMPLE study, in which the DA, further explained under ‘Intervention’, was developed and tested [8], [9], [10], [11]. Through a nationwide research network, all Dutch hospitals were asked to participate until the intended 30 hospitals were included.

For this study we compared two groups of women: a prospective cohort, further mentioned as the intervention group, that consisted of women who met the inclusion criteria and received the DA, including an individual probability of successful vaginal birth after CS calculation, and a retrospective cohort, further mentioned as the control group, consisting of women from the same hospital who met the inclusion criteria but who delivered their babies at least two years prior to the prospective group. Data collection occurred from 2017 to 2018, the control group originated from 2013.

Ethical approval

The study aimed to evaluate the effect of DA use on practice variation at a hospital level. Therefore, the Medical Ethical Committee of the MUMC+ (Maastricht University Medical Centre) agreed on 11-07-2016 that no individual patient informed consent was required beyond that provided for the previous studies (METC 16-4-110).

Study population

Women with one previous CS and without contraindications for TOL and who were pregnant with a singleton in a cephalic position were eligible for inclusion. Contraindications for TOL were previous CS with classical vertical incision, a history of uterus rupture, suspicion of abruptio placentae, mechanical obstruction (such as cervical myoma or placenta/vasa previa), HIV or primary infection with genital herpes simplex.

Intervention

The decision aid was developed and previously published [9]. The DA contains seven steps to support women in their decision-making process regarding the mode of delivery: preferences for mode of delivery before reading the decision aid (1); previous birth experiences (2); risks and benefits of TOL and elective repeat cesarean section (ERCS) (including the prediction model) (3); a worksheet to weigh up the options (4); a birth plan where women can write down their preferences (5); preliminary choice (6); and follow-up to re-evaluate the decision (7) (as can be found in the Supplemental Material 1 (Decision AidVBAC-English version)).

The individual probability of a successful VBAC was calculated using a previously developed prediction model [8]. This model was developed for a Western European population and includes non-progressing labor as the indication for the previous CS, body mass index (BMI), need for induction of labor, ethnicity, estimated fetal weight in the current pregnancy and a previous vaginal delivery.

The DA was available in four languages (Dutch, English, Turkish and Arabic). Women received the DA (including their personalized change of a VBAC, according to the prediction model) somewhere between the intake, at AD ±10 and AD 36 weeks. Depending on the hospital protocol. During consultation at 30–36 weeks, the DA was used as guidance for shared decision-making regarding the mode of delivery. In case the DA was already received early in the pregnancy the calculation of individual probability of a successful VBAC was repeated to adapt to the current situation of the woman.

Instructions and training on how to use the DA in daily practice was provided at quarterly meetings of the nationwide research network. This training was provided to research nurses in the participating hospitals who subsequently trained the medical staff in their hospital. In addition, a website with instructions on the use of the DA was available, which included frequently asked questions.

Outcome measures

In this study, the effects of implementation in every day practice was studied. The primary outcome was practice variation for start and mode of delivery. Although some variation in clinical practice is justified, unwarranted variation is common [5]. This can be caused by decision making using caregivers opinions and experience rather than the patient preferences. This can lead to underuse of effective care, overuse of non-beneficial services, and has been linked to suboptimal outcomes [5]. We quantified practice variation as the standard deviation of the proportion of caesarean sections between hospitals.

Secondary outcomes were combined maternal and neonatal adverse outcome. Maternal adverse outcomes included uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage (defined as ≥1,000 mL blood loss), requirement for blood transfusion, thrombosis, maternal death and admission to the intensive care unit. Neonatal adverse outcomes included perinatal death, neonatal asphyxia defined as pH<7.10 or BE −12.5 or Apgar<7 after 5 min and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Sample size

Prior to implementation of the DA, an average of 67% of women started TOL; 33% (standard deviation [SD] ± 11%) of women opted for an ERCS. To demonstrate a reduction of the SD to 9% with an alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.20, 750 women per study arm were required. Therefore, 30 hospitals with 2 × 25 women were aimed to participate.

Data collection

Data were collected from medical records by research nurses from the participating hospitals. Special case report forms were used to retrieve the desired information. Each case report form contained information on inclusion criteria, maternal age, ethnicity, height, weight, pregnancy duration, obstetric history, current pregnancy, mode of delivery and any complications among the mothers or their babies. The data were provided anonymously to the research team. With this patient information we calculated the probability of a successful VBAC, with the following equation, 1/(1 + EXP(−(1.647 + (0.371 × Ethnicity) − (0.032 × BMI) − (0.537 × Previous CS due to failure to progress) + (1.045 × VG_VB) − (0.515 × Induction) − (0.487 × EFW)))) [8].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS 25. All eligible women were included in the statistical analysis, irrespective of their actual exposure to the DA. The data were entered in the study database by a medical student who was part of the research team. If any inconsistencies were observed, the data were checked with the concerning hospital. Missing data that were important for the analysis were imputed using multiple imputation with fully conditional specification. As omission of incomplete cases can result in loss of precision and may bias the results [12]. The number of imputations was 5.

The independent samples t-test was used for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test was used for binary variables to determine whether the women from both cohorts were comparable.

To calculate the primary outcome the database was aggregated at hospital level. Practice variation was expressed as the standard deviation (SD) of the TOL percentage at the hospital level. As the SD measures the dispersion of a dataset relative to its mean, TOL percentages are further from the mean in case of a high SD and hence, there is more practice variation. Through a F-test the SD before and after nationwide implementation of the DA were compared.

We used the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to calculate the secondary outcomes. In case of a statistically significant difference in baseline characteristics, this was corrected using logistic regression analysis. Therefore, an adjusted p-value for coefficients is presented, further mentioned as adjusted p-value.

Results

Study population

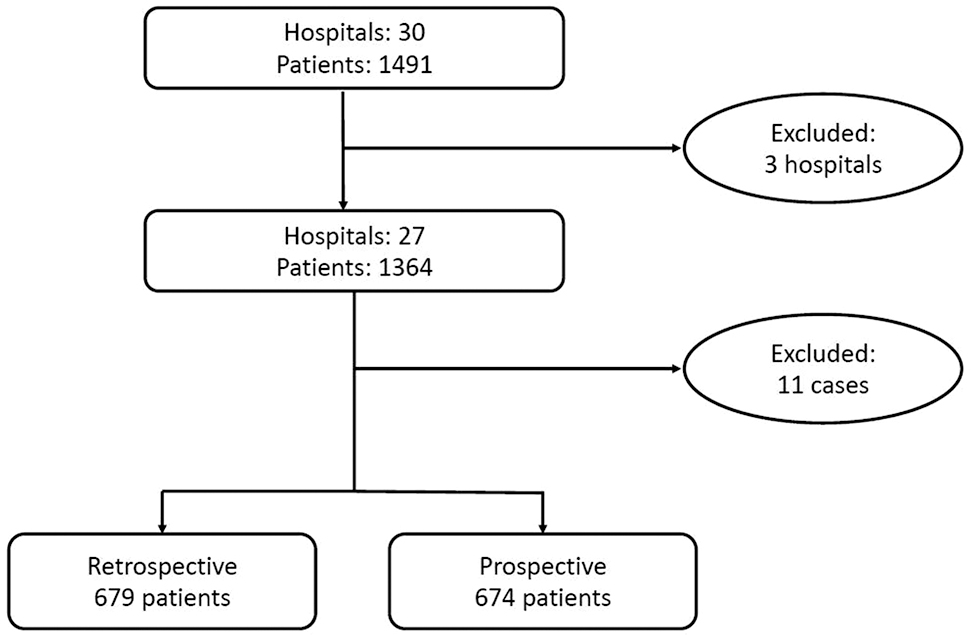

A total of 30 hospitals and 1,491 women were included. All types of hospitals in the Netherlands were included i.e. academic centers, non-academic teaching centers and non-academic non-teaching hospitals. After checking all data, 27 hospitals and a total of 1,364 women were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). Three hospitals were excluded because incomplete data were supplied. Only the data of the women who delivered by planned CS were provided and all data from the women who choose TOL were missing. Four cases did not meet the criteria of a caesarean section in the history. In five of the cases there was no cephalic position of the foetus. The last two cases were excluded cause no outcome of the trial of labour was registered. All 11 women were excluded from analysis. Of the 1,364 women included, 679 belonged to the control group. The intervention group contained 674 women.

Patient flow diagram.

The baseline characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. Both groups were largely comparable, with the exception of previous vaginal delivery and hypertensive disease in the current pregnancy.

Baseline characteristics.

| Demographic characteristics | Control n=679 | Intervention n=674 | p-Value (test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or mean | % or SD | Missing n, % | n or mean | % or SD | Missing n, % | ||

| Maternal age, years | 33.18 | ±4.72 | 151 (22.2) | 32.94 | ±4.41 | 45 (6.7) | 0.37 (t-test) |

| Caucasian (Dutch/European) | 459 | 67.6 | 78 (11.6) | 491 | 72.8 | 36 (5.3) | 0.81 (Chis) |

| BMI | 25.79 | ±5.14 | 127 (18.7) | 25.87 | ±5.23 | 42 (6.2) | 0.786 (t-test) |

| Current pregnancy | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 | 6.0 | 3 (0.4) | 48 | 8.5 | 4 (0.6) | 0.417 (Chis) |

| Hypertensive diseases | 32 | 4.7 | 4 (0.6) | 57 | 8.5 | 6 (0.9) | 0.005 (Chis) |

| EFW > p90 | 74 | 10.9 | 62 (9.1) | 56 | 8.3 | 72 (10.7) | 0.128 (Chis) |

| Gestational age, days | 276 | ±11 | 10 (1.5) | 276 | ±10 | 4 (0.6) | 0.102 (t-test) |

| Obstetric medical history | |||||||

| CS due to failure to progress | 290 | 42.7 | 11 (1.6) | 324 | 48.1 | 1 (0.1) | 0.082 (Chis) |

| Previous vaginal delivery | 144 | 21.2 | 3 (0.4) | 98 | 14.5 | 0 (0) | 0.001 (Chis) |

| Chances of successful VBACa | 0.70 | ±0.12 | 239 (35.2) | 0.69 | ±0.12 | 128 (19.0) | 0.041 (t-test) |

| 0.006b | |||||||

-

BMI, body mass index; Chis, chi-square; CS, cesarean section; EFW, estimated fetal weight; SD, standard deviation.

a1/(1 + EXP(−(1.647 + (0.371 × Ethnicity) − (0.032 × BMI) − (0.537 × Previous CS due to failure to progress) + (1.045 × VG_VB) − (0.515 × Induction) − (0.487 × EFW)))) (8). bAfter imputation.

A statistically significant difference was seen for the probability of a successful VBAC (calculated by the prediction model) in the control group compared to the intervention group (mean 0.7 vs. 0.69; p=0.006). Our main outcome was practice variation on mode and start of delivery. The choice of women might be influenced by their probability of a successful VBAC. Therefore, although the numbers did not differ much, we adjusted for their probability nonetheless.

Practice variation

Practice variation is quantified as the standard deviation of the proportion of caesarean sections between hospitals. Our results show that the standard deviation considerably drops from 0.17 to 0.10, and the null-hypothesis that the standard deviations are equal can be rejected, according to a p-value of 0.010. The practice variation in successful VBAC rate did not change statistically significantly (0.19 SD vs. 0.13 SD, p=0.061).

Mode of delivery

The start of the labor and mode of delivery is shown in Table 2. After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics, we observed no statistically differences in the parameters evaluated.

Start labor and model of delivery.

| Control n=679, % | Intervention n=674, % | OR (CI 95%)a | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start labor | ||||

| Trial of labor | 431 (63.5) | 410 (60.8) | 0.912 (0.730–1.138) | 0.413 |

| Spontaneous | 313 (46.1) | 279 (41.4) | 0.928 (0.739–1.166) | 0.523 |

| Induction of labora | 118 (17.4) | 131 (19.4) | 0.972 (0.724–1.305) | 0.849 |

| Elective repeat CS | 248 (36.5) | 264 (39.2) | 1.097 (0.879–1.369) | 0.413 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal (VBAC) | 313 (46.1) | 270 (40.1) | 0.833 (0.666–1.042) | 0.109 |

| Spontaneous | 267 (39.3) | 232 (34.5) | 0.80 (0.691–1.094) | 0.233 |

| Vaginal instrumental delivery | 46 (6.8) | 38 (5.6) | 0.824 (0.528–1.287) | 0.395 |

| Unplanned CS | 118 (17.4) | 140 (20.7) | 1.164 (0.880–1.540) | 0.287 |

-

aBalloon/prostaglandins/amniotomy. CS, cesarean section; VBAC, vaginal birth after cesarean.

Complications

Maternal and neonatal morbidity is summarized in Table 3. Combined outcome was defined as one or more of the individual adverse outcomes, showing a proportional reduction of 21%, based on 89 complications in the control group and 70 in the intervention group (p=0.071). An analysis for the influence of pre-term deliveries inclusions on the rate of complications was performed but showed no statistically significant change. Therefore, these results are not shown separately.

Complications.

| Control n=679 (%) | Intervention n=674 (%) | OR (CI 95%)a | p-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined outcome | ||||

| Maternal and fetal | 89 (13.1) | 70 (10.4) | 0.73 (0.52–1.027) | 0.071 |

| Maternal | 54 (8.0) | 44 (6.5) | 0.772 (0.509–1.171) | 0.224 |

| Fetal | 40 (5.9) | 33 (4.9) | 0.784 (0.486–1.264) | 0.318 |

| Maternal complications | ||||

| Uterine rupture | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1.0) | 1.630 (0.476–5.577) | 0.442 |

| Blood loss>1,000 mL | 47 (6.9) | 35 (5.2) | 0.718 (0.456–1.130) | 0.152 |

| Blood transfusion | 12 (1.8) | 6 (0.9) | 0.441 (0.162–1.199) | 0.109 |

| Thrombosis | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 (0.000–0.000) | 1.0 |

| Admitted to ICU | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 (0.000–0.000) | 1.0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Fetal complications | ||||

| Death | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 1.122 (0.179–7.043) | 0.902 |

| Signs of asphyxiaa | 22 (3.3) | 19 (2.8) | 0.829 (0.443–1.553) | 0.558 |

| NICU admittance | 23 (3.4) | 16 (2.4) | 0.686 (0.358–1.311) | 0.255 |

-

ICU, intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. apH<7.10 or BE −12.5 or Apgar<7 after 5 min.

Discussion

Principal findings

The nationwide implementation of counselling using the decision aid went along with reduced practice variation, with no accompanying increase in the rate of cesarean section or complications.

Clinical implications and results

There is a large practice variation in VBAC between and within countries [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Variation in healthcare is generally inevitable as it is a complex system and it is impossible to control all of the variables. Some clinical variation may be explained by the characteristics of individual women or by differences in the capability of clinicians, and is therefore unavoidable. However, unwarranted clinical variation is care that is not consistent with women’s preferences or to their current situation.

Previous research by our group showed the positive effect on women’s satisfaction achieved through the use of a DA in a research setting [10]. The current study is the first to evaluate everyday practice after nationwide implementation and has shown a significant reduction in practice variation. This suggests that use of the DA reduces the influence of caregiver’s own opinions and culture on women’s choices. Resulting in more equality of care without increase in cesarean section rates or complications.

One of the barriers identified in previous research for CS care, is the concern among caregivers regarding an increased ERCS rate when women are involved in the decision-making process [6]. In line with this barrier an increase in ERCS rate was seen in a previous prospective cohort study in the intervention group [10]. However, this was in combination with an unchanged VBAC rate and a 40% reduction in unplanned CS. This findings suggest improved risk selection due to the use of the DA rather than a thoughtless rise in ERCS [10]. In the current study, we show a small and non-significant decrease in both the total VBAC rates (p=0.109) and adverse outcomes (p=0.071). Changes over time will always influence before and after cohort studies and, in comparison with our previous study, ERCS was already higher in the control group in our current study, probably due to a higher level of awareness regarding informed decision-making in women with a previous CS [10]. Unlike the TOL rates, the current study is likely to be underpowered for adverse outcomes. Nevertheless, based on 89 complications in the control group and 70 in the intervention group, a clinically relevant reduction of 21% overall complication rate is seen.

Several other studies have investigated differences in preferred and actual delivery mode after the use of a DA or a prediction model, and support the findings of the current study, showing no differences in the delivery mode [18], [19], [20]. Data on adverse outcomes are lacking and the results of an ongoing Canadian trial are eagerly awaited [21].

Research implications

We performed a nation-wide introduction of a DA with a prediction model. Both, the DA and the prediction model were developed and tested in the Netherlands. Although our decision aid is available in Dutch, English, Turkish and Arabic, it has not been spread and evaluated in other countries. Further research is needed to find out if our DA and prediction model give the same results in other countries.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the current study is the usability of the results. We evaluated the use of a DA, including a prediction model for the mode of delivery after CS, after national implementation. Thereby, the DA has been proven to be effective in a prospective cohort [10]. Several other prediction models have been developed in different countries, although none of these have been tested in practice as part of the counselling process, nor have these studies evaluated the effects of these models after implementation [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33].

A complementary strength is the study population and generalizability, as a total of 1,353 women were included from all regions of the Netherlands and from all hospital types, i.e., academic, non-academic teaching and non-academic, non-teaching hospitals.

Although we did not reach the intended sample size, we did have more than sufficient statistical power to detect a clinically meaningful difference between groups, exemplified by the fact that the difference in variance between groups, in this case presented as standard deviations of 0.17 and 0.10, was statistically significant. A larger sample size would likely only have resulted in an even lower p-value, as the standard error of our estimates would have decreased as a function of the sample size.

It is questionable whether the data can be generalized to populations with low VBAC rates as this study was conducted in the Netherlands where the VBAC rate is usually high. In countries with a low a priori VBAC rate, women may have other preferences. The cultural background and the preference of the healthcare providers may also play a role. Finally, the women in this study were primarily of Dutch or other European ethnicity, who are known to be more likely to deliver vaginally compared with other ethnicities. However, it is not unlikely that in countries with a lower VBAC rate, the use of the DA may lead to an increase in VBAC.

Conclusions

Nationwide implementation of the DA showed a significant reduction in practice variation without increase in the rate of cesarean section or complications, suggesting an improvement in equality of care.

Funding source: ZonMw

Award Identifier / Grant number: 1710030061

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participation hospitals, medical doctors and research nurses of the following hospitals for their help in completing the SIMPLE 2 implementation study: Amsterdam University Medical Centre, location AMC and location VUMC; Amstelland Hospital Amsterdam; Antonius Hospital Sneek; Beatrix Hospital Gorinchem; Bethesda Hospital Hoogeveen; Canisius Hospital Nijmegen; Deventer Hospital Deventer; Diakonessenhuis Utrecht; Dijklander Hospital location Purmerend (former Waterland Hospital); Elisabeth TweeSteden Hospital Tilburg; Flevohospital Almere; Franciscus gasthuis location Rotterdam; Gelre Hospital Zutphen; Haga Hospital Den Haag; Jeroen Bosch Hospital Den Bosch; LangeLand Hospital Zoetermeer; Laurentius Hospital Roermond; Meander Hospital Utrecht; Medical Centre Haaglanden Den Haag; Medical spectrum Twente; Onze Lieve Vrouwen Gasthuis location East Amsterdam; Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen; Reinier de Graaf Hospital Delft; Spaarne Gasthuis Haarlem/Hoofddorp; Tergooi Blaricum; University Medical Centre Groningen; University Medical Centre Utrecht; VieCuri Venlo; Hospital Group Twente Almelo/Hengelo (ZGT).

-

Research funding: The Dutch organization for healthcare research and innovation (ZonMW) provided a grant to conduct this research. For the provided grand no external peer review was needed. The grant is used as a reimbursement. ZonMW had no interference in the publication process. Participating hospitals received a, predefined amount of money, per patient with a maximum amount of patients per hospital. Reference number: 1710030061.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: None of the authors have a conflict of interest to report.

-

Informed consent & Ethical approval: The study aimed to evaluate the effect of DA use on practice variation at a hospital level. Therefore, the Medical Ethical Committee of the MUMC+ (Maastricht University Medical Centre) agreed on 11-07-2016 that no individual patient informed consent was required beyond that provided for the previous studies (METC 16-4-110).

References

1. Knight, HE, Gurol-Urganci, I, van der Meulen, JH, Mahmood, TA, Richmond, DH, Dougall, A, et al.. Vaginal birth after caesarean section: a cohort study investigating factors associated with its uptake and success. BJOG 2014;121:183–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12508.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. McMahon, MJ, Luther, ER, Bowes, WAJr, Olshan, AF. Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med 1996;335:689–95. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199609053351001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Ryan, GA, Nicholson, SM, Morrison, JJ. Vaginal birth after caesarean section: current status and where to from here? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;224:52–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.02.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Vankan, E, Schoorel, EN, van Kuijk, SM, Mol, BJ, Nijhuis, JG, Aardenburg, R, et al.. Practice variation of vaginal birth after cesarean and the influence of risk factors at patient level: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:158–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13059.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Cook, DA, Pencille, LJ, Dupras, DM, Linderbaum, JA, Pankratz, VS, Wilkinson, JM. Practice variation and practice guidelines: attitudes of generalist and specialist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. PloS One 2018;13:e0191943. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191943.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Melman, S, Schreurs, RHP, Dirksen, CD, Kwee, A, Nijhuis, JG, Smeets, NAC, et al.. Identification of barriers and facilitators for optimal cesarean section care: perspective of professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1416-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Melman, S, Schoorel, ECN, de Boer, K, Burggraaf, H, Derks, JB, van Dijk, D, et al.. Development and measurement of guidelines-based quality indicators of caesarean section care in The Netherlands: a RAND-modified delphi procedure and retrospective medical chart review. PloS One 2016;11:e0145771-e. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145771.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Schoorel, EN, van Kuijk, SM, Melman, S, Nijhuis, JG, Smits, LJ, Aardenburg, R, et al.. Vaginal birth after a caesarean section: the development of a Western European population-based prediction model for deliveries at term. BJOG 2014;121:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12539.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Schoorel, EN, Vankan, E, Scheepers, HC, Augustijn, BCC, Dirksen, CD, de Koning, M, et al.. Involving women in personalised decision-making on mode of delivery after caesarean section: the development and pilot testing of a patient decision aid. BJOG 2014;121:202–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12516.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Vankan, E, Schoorel, E, van Kuijk, S, Augustijn, BC, Dirksen, CD, de Koning, M, et al.. The effect of the use of a decision aid with individual risk estimation on the mode of delivery after a caesarean section: a prospective cohort study. PloS One 2019;14:e0222499. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222499.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Schoorel, EN, Melman, S, van Kuijk, SM, Grobman, WA, Kwee, A, Mol, BW, et al.. Predicting successful intended vaginal delivery after previous caesarean section: external validation of two predictive models in a Dutch nationwide registration-based cohort with a high intended vaginal delivery rate. BJOG 2014;121:840–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12605.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Donders, AR, van der Heijden, GJ, Stijnen, T, Moons, KG. Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1087–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Colais, P, Bontempi, K, Pinnarelli, L, Piscicelli, C, Mappa, I, Fusco, D, et al.. Vaginal birth after caesarean birth in Italy: variations among areas of residence and hospitals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:383. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2018-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Gregory, KD, Fridman, M, Korst, L. Trends and patterns of vaginal birth after cesarean availability in the United States. Semin Perinatol 2010;34:237–43. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2010.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. MacDorman, MF, Menacker, F, Declercq, E. Cesarean birth in the United States: epidemiology, trends, and outcomes. Clin Perinatol 2008;35:293–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2008.03.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. DeFranco, EA, Rampersad, R, Atkins, KL, Odibo, AO, Stevens, EJ, Peipert, JF, et al.. Do vaginal birth after cesarean outcomes differ based on hospital setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Bailit, JL, Dooley, SL, Peaceman, AN. Risk adjustment for interhospital comparison of primary cesarean rates. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:1025–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-199906000-00026.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Montgomery, AA, Emmett, CL, Fahey, T, Jones, C, Ricketts, I, Patel, RR, et al.. Two decision aids for mode of delivery among women with previous caesarean section: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2007;334:1305. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39217.671019.55.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Horey, D, Kealy, M, Davey, MA, Small, R, Crowther, CA. Interventions for supporting pregnant women’s decision-making about mode of birth after a caesarean. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:Cd010041. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010041.pub2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Shorten, A, Shorten, B, Keogh, J, West, S, Morris, J. Making choices for childbirth: a randomized controlled trial of a decision-aid for informed birth after cesarean. Birth 2005;32:252–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00383.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Chaillet, N, Bujold, E, Masse, B, Grobman, WA, Rozenberg, P, Pasquier, JC, et al.. A cluster-randomized trial to reduce major perinatal morbidity among women with one prior cesarean delivery in Quebec (PRISMA trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:434. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2150-x.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Gonen, R, Tamir, A, Degani, S, Ohel, G. Variables associated with successful vaginal birth after one cesarean section: a proposed vaginal birth after cesarean section score. Am J Perinatol 2004;21:447–53. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-835961.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Grobman, WA, Lai, Y, Landon, MB, Spong, CY, Leveno, KJ, Rouse, DJ, et al.. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:806–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000259312.36053.02.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Grobman, WA, Lai, Y, Landon, MB, Spong, CY, Leveno, KJ, Rouse, DJ, et al.. Does information available at admission for delivery improve prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean? Am J Perinatol 2009;26:693–701. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1239494.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Jakobi, P, Weissman, A, Peretz, BA, Hocherman, I. Evaluation of prognostic factors for vaginal delivery after cesarean section. J Reprod Med 1993;38:729–33.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Macones, GA, Hausman, N, Edelstein, R, Stamilio, DM, Marder, SJ. Predicting outcomes of trials of labor in women attempting vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: a comparison of multivariate methods with neural networks. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:409–13. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.109386.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Metz, TD, Stoddard, GJ, Henry, E, Jackson, M, Holmgren, C, Esplin, S. Simple, validated vaginal birth after cesarean delivery prediction model for use at the time of admission. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:571–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31829f8ced.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Naji, O, Wynants, L, Smith, A, Abdallah, Y, Stalder, C, Sayasneh, A, et al.. Predicting successful vaginal birth after cesarean section using a model based on cesarean scar features examined by transvaginal sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:672–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12423.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Pickhardt, MG, Martin, JN, Meydrech, EF, Blake, PG, Martin, RW, Perry, KG, et al.. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: are there useful and valid predictors of success or failure? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1811–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(92)91572-r.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Smith, GC, White, IR, Pell, JP, Dobbie, R. Predicting cesarean section and uterine rupture among women attempting vaginal birth after prior cesarean section. PLoS Med 2005;2:e252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020252.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Srinivas, SK, Stamilio, DM, Stevens, EJ, Odibo, AO, Peipert, JF, Macones, GA. Predicting failure of a vaginal birth attempt after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:800–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000259313.46842.71.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Tessmer-Tuck, JA, El-Nashar, SA, Racek, AR, Lohse, CM, Famuyide, AO, Wick, MJ. Predicting vaginal birth after cesarean section: a cohort study. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2014;77:121–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000357757.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Weinstein, D, Benshushan, A, Tanos, V, Zilberstein, R, Rojansky, N. Predictive score for vaginal birth after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:192–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70393-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2021-0007).

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction to the cesarean section articles

- Highlight Section: Cesarean Section

- Three kinds of caesarean sections: the foetal/neonatal perspective

- The neonatal respiratory morbidity associated with early term caesarean section – an emerging pandemic

- Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC): fear it or dare it? An evaluation of potential risk factors

- Nationwide implementation of a decision aid on vaginal birth after cesarean: a before and after cohort study

- Induction of labor at 39 weeks and risk of cesarean delivery among obese women: a retrospective propensity score matched study

- Cervical ripening after cesarean section: a prospective dual center study comparing a mechanical osmotic dilator vs. prostaglandin E2

- An evidence-based cesarean section suggested for universal use

- Online survey on uterotomy closure techniques in caesarean section

- Analysis of cesarean section rates in two German hospitals applying the 10-Group Classification System

- Reviews

- Pregnancy in incarcerated women: need for national legislation to standardize care

- Imaging diagnosis and legal implications of brain injury in survivors following single intrauterine fetal demise from monochorionic twins – a review of the literature

- Mini Review

- Professionally responsible management of the ethical and social challenges of antenatal screening and diagnosis of β-thalassemia in a high-risk population

- Opinion Paper

- Teaching and training the total percutaneous fetoscopic myelomeningocele repair

- Corner of Academy

- Chronic hypertension in pregnancy: synthesis of influential guidelines

- Original Articles

- The effects of pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain on maternal lipid profiles, fatty acids and insulin resistance

- Determination of organic pollutants in meconium and its relationship with fetal growth. Case control study in Northwestern Spain

- Betamethasone as a potential treatment for preterm birth associated with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation: a murine study

- Diagnostic accuracy of modified Hadlock formula for fetal macrosomia in women with gestational diabetes and pregnancy weight gain above recommended

- Vasa previa: when antenatal diagnosis can change fetal prognosis

- Mode of delivery and adverse short- and long-term outcomes in vertex-presenting very preterm born infants: a European population-based prospective cohort study

- Short Communication

- Reference ranges for sphingosine-1-phosphate in neonates

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction to the cesarean section articles

- Highlight Section: Cesarean Section

- Three kinds of caesarean sections: the foetal/neonatal perspective

- The neonatal respiratory morbidity associated with early term caesarean section – an emerging pandemic

- Vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC): fear it or dare it? An evaluation of potential risk factors

- Nationwide implementation of a decision aid on vaginal birth after cesarean: a before and after cohort study

- Induction of labor at 39 weeks and risk of cesarean delivery among obese women: a retrospective propensity score matched study

- Cervical ripening after cesarean section: a prospective dual center study comparing a mechanical osmotic dilator vs. prostaglandin E2

- An evidence-based cesarean section suggested for universal use

- Online survey on uterotomy closure techniques in caesarean section

- Analysis of cesarean section rates in two German hospitals applying the 10-Group Classification System

- Reviews

- Pregnancy in incarcerated women: need for national legislation to standardize care

- Imaging diagnosis and legal implications of brain injury in survivors following single intrauterine fetal demise from monochorionic twins – a review of the literature

- Mini Review

- Professionally responsible management of the ethical and social challenges of antenatal screening and diagnosis of β-thalassemia in a high-risk population

- Opinion Paper

- Teaching and training the total percutaneous fetoscopic myelomeningocele repair

- Corner of Academy

- Chronic hypertension in pregnancy: synthesis of influential guidelines

- Original Articles

- The effects of pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain on maternal lipid profiles, fatty acids and insulin resistance

- Determination of organic pollutants in meconium and its relationship with fetal growth. Case control study in Northwestern Spain

- Betamethasone as a potential treatment for preterm birth associated with sterile intra-amniotic inflammation: a murine study

- Diagnostic accuracy of modified Hadlock formula for fetal macrosomia in women with gestational diabetes and pregnancy weight gain above recommended

- Vasa previa: when antenatal diagnosis can change fetal prognosis

- Mode of delivery and adverse short- and long-term outcomes in vertex-presenting very preterm born infants: a European population-based prospective cohort study

- Short Communication

- Reference ranges for sphingosine-1-phosphate in neonates