Does the length of second stage of labour or second stage caesarean section in nulliparous women increase the risk of preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies?

Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the role of prolonged second stage of labour and second stage caesarean section on the risk of spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) in a subsequent pregnancy.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of nulliparous women with two consecutive singleton deliveries between 2014 and 2017 at a tertiary centre. In the vaginal delivery cohort, subsequent pregnancy outcomes for women with a prolonged second stage (>2 h) were compared with those with a normal second stage (≤2 h). In the caesarean delivery cohort, women with a first stage or a second stage were compared with the vaginal delivery cohort. The primary outcome was subsequent sPTB.

Results

A total of 821 women met inclusion criteria, of which 74.8% (614/821) delivered vaginally and 25.2% (207/821) delivered by caesarean section. There was no association between a prolonged second stage in the index pregnancy and subsequent sPTB (aOR 0.70, 95% CI 0.13–3.83, p=0.7). The risk of subsequent sPTB was threefold for those with a second stage caesarean section; however this did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

A prolonged second stage of labour in the index pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of subsequent sPTB. A second stage caesarean section in the index pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of subsequent sPTB, however there was no statistically significant difference. These findings are important for counseling and suggest that the effects of these factors are not clinically significant to justify additional interventions in the subsequent pregnancy.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is defined as any birth occurring before 37 completed weeks of gestation, and occurs at a rate of 8.7% in Australia [1]. Preterm birth complications comprise the major cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. Premature infants are at increased risk of immediate and delayed comorbidities, including respiratory distress, cardiovascular abnormalities, intraventricular haemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity and infection [2].

Maternal risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) include a history of preterm birth, extremes of age, cigarette smoking, low socio-economic status, high or low body mass index (BMI), cervical and uterine abnormalities and chronic medical conditions [3], [4], [5], [6]. Cervical abnormalities can be congenital, or more commonly iatrogenic following surgical procedures such as a large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or a cone biopsy. It has been shown that cervical procedures can lead to structural weakness in the cervix and may result in cervical insufficiency and preterm birth [7]. On this basis, it has been postulated that cervical trauma occurring during labour and delivery can also have this lasting effect on cervical structural integrity.

The second stage of labour is defined as the period from full dilatation of the cervix until the delivery of the baby [8]. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), in the first labour the second stage is usually completed within 3 h, with an upper 95th percentile of 1.1–2.3 h without epidural analgesia, and 2.3–3.6 h with epidural analgesia [8]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that arrest of labour in the second stage should be considered after 3 h in the nulliparous woman [9]. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) states that a normal second stage for a nulliparous woman is up to 2 h [10].

Recent studies have considered the role of intrapartum factors of a prolonged second stage and a second stage caesarean section on sPTB in subsequent pregnancies. During the second stage of labour, the fetal head is pressed against a dilated cervix, and it is hypothesised that prolonging this stage may result in permanent changes in cervical integrity and strength [11]. Others have postulated that a second stage caesarean section is associated with a greater risk of cervical laceration or extensions, which can result in cervical structural damage [12]. The effects of a prolonged second stage in labour have been investigated in retrospective cohort studies by Sciaky-Tamir et al. (2015), Levine et al. (2016) and Quinolones et al. (2018), with inconsistent findings [11], [13], [14]. The impact of a second stage caesarean section has been investigated in previous studies by Levine et al. (2015) and Wood et al. (2017), which demonstrated a higher rate of subsequent sPTB in women with an initial second stage caesarean section compared to the general population [12], [15].

Therefore, this study aimed to further investigate the effects of a prolonged second stage and a second stage caesarean section on subsequent sPTB in nulliparous women with two consecutive singleton deliveries at a single tertiary centre in Australia.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of nulliparous women with a singleton delivery at ≥37 weeks followed by a subsequent singleton delivery over a 4-year period between January 2014 and December 2017 at a single hospital. The Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital is a large tertiary maternity centre in Brisbane, Australia, with an average of 4,600 deliveries per annum [16]. The institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (Reference number: LNR/2020/QRBW/62589).

Deliveries were subsequently categorised into a vaginal delivery cohort and a caesarean section cohort in the index pregnancy. For the analysis of the duration of the second stage, a prolonged second stage was defined as second stage >2 h. For the analysis of stage at time of caesarean section, a first stage caesarean section was defined as <10 cm cervical dilatation and a second stage caesarean section was defined as at full cervical dilatation. These cohorts were compared with a vaginal delivery control cohort. Data was extracted from electronic charts and correlated with medical records for both the initial and subsequent delivery. The primary outcome for the study was subsequent sPTB which was defined as spontaneous delivery prior to completed 37 weeks of gestation. Exclusion criteria included initial preterm birth or initial stillbirth, initial or subsequent multiple pregnancy, and initial or subsequent known major fetal abnormality. Major fetal abnormality included any documented chromosomal or structural abnormality resulting in intrapartum intervention or feticide.

Demographic data analysed for the index pregnancy included age, interpregnancy interval, BMI, ethnicity, smoking, diabetes (including gestational, type 1 and type 2), hypertensive disorders (including chronic, gestational and pre-eclampsia), previous cervical surgery (including LLETZ and cone biopsy), epidural use, mode of delivery, duration of second stage, cervical dilation at time of caesarean section, induction of labour and gestational age at delivery. Obstetric outcomes analysed for the subsequent pregnancy included gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery and birth weight.

Statistical analysis

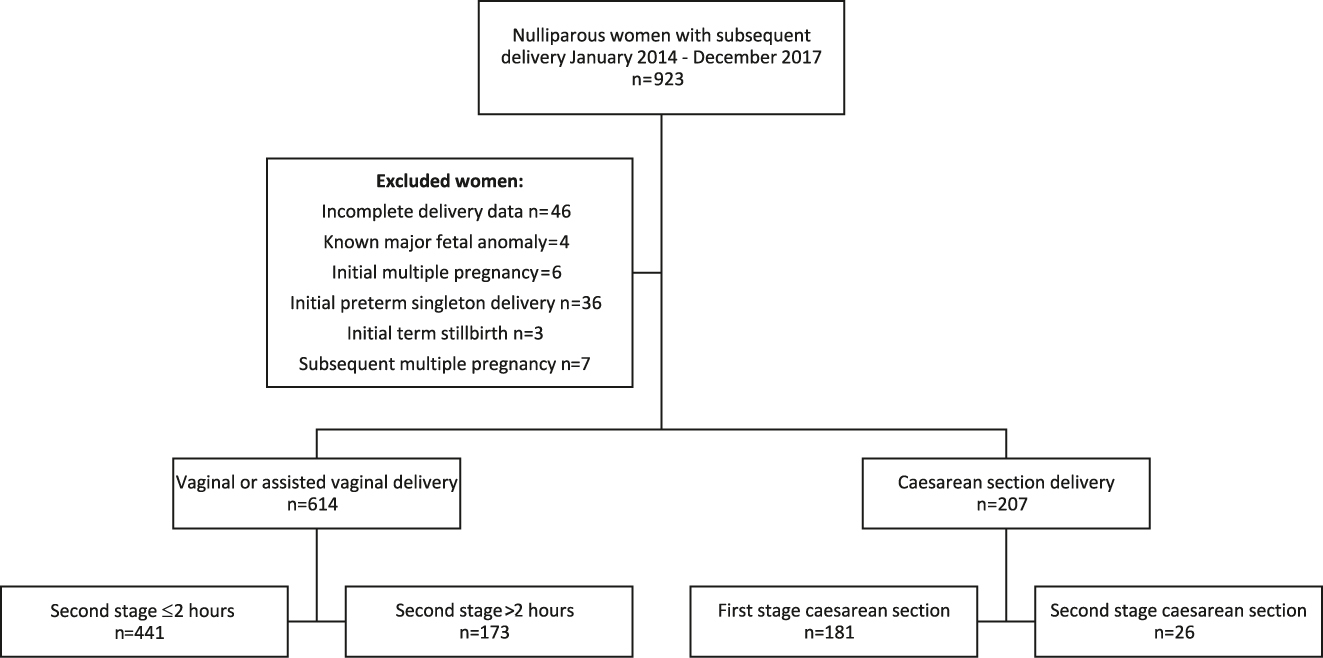

Data analysis involved analysis by descriptive Chi-square tests and Fisher extract test for categorical variables and Mann Whitney U-tests for nonparametric continuous variables. All continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk W-test and deemed to be nonparametric. Subsequently data are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD) or as the number of observations (n) with the percentage of total. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate analysis was adjusted for confounders of age, BMI, diabetes, cervical procedures and gestational age at delivery. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM. 2017. SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Figure 1

Flowchart of study participants in the index pregnancy.

Results

A total of 821 nulliparous women met the study inclusion criteria, with an initial singleton delivery at ≥37 weeks gestation followed by a subsequent singleton delivery within the four-year study period. In the index pregnancy, 74.8% (614/821) of women delivered vaginally by spontaneous vaginal delivery or assisted vaginal delivery, while 25.2% (207/821) of women delivered by caesarean section. Of the women who delivered vaginally, 71.8% (441/614) had a normal second stage ≤2 h, and 28.2% (173/614) had a prolonged second stage >2 h. Of the women who delivered by caesarean section, 87.4% (181/207) were in the first stage of labour, and 12.6% (26/207) were in the second stage of labour (Table 1).

Maternal demographics of index pregnancy.

| Delivery method in index pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal second stage (n=441) | Prolonged second stage (n=173) | First stage CS (n=181) | Second stage CS (n=26) | |

| Age, years | 29.05±5.12 | 30.39±4.78 b | 31.22±4.82 c | 32.15±4.82 a |

| Interpregnancy interval, days | 758.54±252.65 | 762.53±248.28 | 763.32±231.61 | 828.12±194.55 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.15±5.57 | 24.71±4.95 a | 24.80±5.55 | 26.18±7.64 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 62/412 (15.0%) | 23/162 (14.2%) | 27/181 (14.9%) | 2/23 (7.7%) |

| ATSI | 14/412 (3.4%) | 1/162 (0.6%) | 4/181 (2.2%) | 1/23 (3.8%) |

| Caucasian | 311/412 (74.5%) | 128/162 (79.0%) | 119/181 (65.7%) | 20/23 (76.9%) |

| Pacific Islander | 12/412 (2.9%) | 5/162 (3.1%) | 6/181 (3.3%) | 0/23 (0%) |

| Other | 13/412 (3.2%) | 4/162 (2.5%) | 9/181 (5.0%) | 0/23 (0%) |

| Smoking | 23/440 (5.2%) | 7/173 (4.0%) | 9/181 (5.0%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Maternal comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 34/441 (7.7%) | 11/173 (6.4%) | 23/181 (12.7%) a | 2/26 (7.7%) |

| Hypertensive disorders | 27/441 (6.1%) | 18/173 (10.4%) | 20/181 (11%) | 3/26 (11.5%) |

| Previous cervical surgery | 15/439 (3.4%) | 9/172 (5.2%) | 15/181 (8.3%) a | 3/26 (11.5%) |

| Epidural use | 148/439 (33.7%) | 133/173 (76.9%) c | – | – |

| Induction of labour | 105/441 (23.8%) | 43/173 (24.9%) | 57/118 (48.3%) c | 11/26 (42.3%) a |

| Gestation at delivery, weeks | 39.73±1.41 | 40.04±1.16 b | 39.43±2.15 | 40.25±0.97 |

Data presented as mean±standard deviation or n (percentage) unless stated otherwise. Prolonged second stage compared with normal second stage cohort. Both caesarean section cohorts compared against vaginal delivery cohort. aSignificant difference with p-value < 0.05. bSignificant difference with p-value < 0.01. cSignificant difference with p-value < 0.001. CS, caesarean section; ATSI, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; BMI, body mass index.

In the analysis of the duration of the second stage in the vaginal delivery cohort, women with a prolonged second stage of labour were compared to those who had a normal second stage. The mean length of the second stage was 1.5±1.0 h, ranging from 0 to 5.0 h. Women in the prolonged second stage cohort were older (29.1 vs. 30.4, p<0.01), had a higher BMI (24.2 vs. 24.8, p<0.05), had more likely to have used epidural analgesia (33.7 vs. 76.9%, p<0.001) and delivered at a later gestational age (39.7 vs. 40.0, p<0.01) when compared with the normal second stage cohort. There was no statistically significant difference in the interpregnancy interval, ethnicity, smoking status, diabetes, hypertensive disorders, or induction of labour between the two groups.

In the analysis of the stage of labour at time of caesarean section, women with a first stage caesarean section or a second stage caesarean section were compared with the vaginal delivery cohort. Women in the first stage of labour caesarean section cohort were older (29.4 vs. 31.2, p<0.001), more likely to have had diabetes (7.2 vs. 12.7, p<0.05), previous cervical surgery (3.9 vs. 8.3, p<0.05), and an induction of labour (24.2 vs. 48.3, p<0.001) when compared with vaginal delivery. There was no statistically significant difference in interpregnancy interval, BMI, ethnicity, smoking, hypertensive disorders, or gestational age at delivery for first stage caesarean section. Women in the second stage of labour caesarean section cohort were also older (29.4 vs. 32.1, p<0.05) and more likely to have had an induction of labour (24.2 vs. 42.3, p<0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in interpregnancy interval, BMI, ethnicity, smoking, diabetes, hypertensive disorders, cervical surgery or gestational age at delivery for the second stage of labour caesarean section cohort. Table 2

Obstetric outcomes in subsequent pregnancy.

| Delivery method in index pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal second stage (n=441) | Prolonged second stage (n=173) | First stage CS (n=181) | Second stage CS (n=26) | |

| Gestation at delivery, weeks | 39.28±1.66 | 39.44±1.58 | 38.62±1.59 c | 38.65±0.89 b |

| PTB | 21/441 (4.76%) | 6/173 (3.47%) | 14/181 (7.7%) | 1/26 (3.8%) |

| sPTB | 9/441 (2.0%) | 2/173 (1.2%) | 4/181 (2.2%) | 1/26 (3.8%) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| SVD | 386/441 (87.5%) | 144/173 (83.2%) | 14/181 (7.7%) c | 3/26 (11.5%) c |

| IVD | 11/441 (2.5%) | 12/173 (6.9%) a | 8.181 (4.4%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Emergency CS | 20/411 (4.5%) | 7/173 (4.0%) | 48/181 (26.5%) c | 3/26 (11.5%) |

| Elective CS | 24/441 (5.4%) | 10/173 (5.8%) | 111/181 (61.3%) c | 20/26 (76.9%) c |

| Birth weight, grams | 3444.02±509.28 | 3538.54±499.58 a | 3436.16±568.94 | 3473.19±3473.19 |

Data presented as mean±standard deviation or n (percentage) unless stated otherwise. Prolonged second stage compared with normal second stage cohort. Both caesarean section cohorts compared against vaginal delivery cohort. Spontaneous preterm birth defined as preterm birth <37 weeks excluding induction of labour, elective caesarean section and medically indicated emergency caesarean section. aSignificant difference with p-value <0.05. bSignificant difference with p-value <0.01. cSignificant difference with p-value <0.001. CS, caesarean section; PTB, preterm birth; sPTB, spontaneous preterm birth; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery; IVD, instrumental vaginal delivery.

In the subsequent pregnancy, the overall rate of sPTB was 1.9% (16/821) after excluding induction of labour, elective caesarean section and medically indicated emergency caesarean section. There was no association between a prolonged second stage of labour and subsequent sPTB when compared with a normal second stage, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.70 (95% CI 0.13–3.83, p=0.7). The odds ratio was adjusted for age, BMI, epidural use and gestational age at delivery. Women with a prolonged second stage of labour in the index pregnancy were more likely to have had an instrumental delivery (2.5 vs. 6.9, p<0.05), and a higher birth weight (3444 vs. 3539, p<0.05) in the subsequent pregnancy. There was no statistically significant difference in the subsequent gestation at delivery, spontaneous vaginal delivery rate and caesarean section rate between the two groups.

Similarly, there was no significant difference in subsequent sPTB for the second stage of labour caesarean section cohort when compared to the vaginal delivery cohort, however the adjusted odds ratio was 3.42 (95% CI 0.40–29.05, p=0.2), adjusted for age and induction of labour. There was also no significant difference in subsequent sPTB when the initial second stage of labour cohort was compared with the first stage cohort, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.30 (95% CI 0.19–27.74, p=0.5). This odds ratio was adjusted for age, diabetes, induction of labour and cervical surgery. Women who had a second stage of labour caesarean section in the index pregnancy, delivered earlier (39.3 vs. 38.7, p<0.01), were less likely to have a spontaneous vaginal delivery (86.4 vs. 11.5, p<0.001) and more likely to have an elective caesarean section (5.6 vs. 76.9, p<0.001) in the subsequent pregnancy. There was no statistically significant difference in instrumental delivery rate, emergency caesarean section rate, and the birth weight at delivery when compared to the vaginal delivery cohort.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of nulliparous women with two subsequent singleton pregnancies, we did not find a significant increase in the sPTB rate in the subsequent pregnancy in women with a prolonged second stage of labour or a second stage caesarean section in the index pregnancy. These two intrapartum factors were proposed based on the presumed potential for intrinsic cervical damage resulting in cervical insufficiency and sPTB. The overall subsequent sPTB rate in the study cohort was 1.9%.

Prolonged second stage

Women with prolonged second stage of labour >2 h had a lower overall subsequent sPTB rate of 1.2%, however there was no statistically significant association. Identified risk factors for a prolonged second stage of labour were older maternal age, higher body mass index and the use of epidural analgesia. These identified risk factors for a prolonged second stage are consistent with the literature [17].

Our findings are in support of two of three previous studies. A retrospective cohort study of a Canadian population by Sciaky-Tamir et al. (2015) similarly found no relationship between prolonged second stage of labour >3 h and subsequent sPTB [11]. This study investigated a cohort of nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies as the index pregnancy, however, did not specify the exclusion of multiple pregnancies in the subsequent pregnancy. Potential confounders such as ethnicity, BMI and history of cervical procedures were not examined in this cohort. Following this, Levine et al. (2016) also found that a prolonged second stage of labour >3 h did not confer an increased risk of sPTB in the subsequent pregnancy. This study included both nulliparous and multiparous women in the index pregnancy and did not specify the exclusion of multiple pregnancies. Conversely, in a recent large retrospective cohort study of an American population, Quinones et al. (2018) studied a population of nulliparous women with two consecutive singleton pregnancies and found that a prolonged second stage of labour ≥3 h was associated with a 1.8-fold risk of sPTB in the subsequent pregnancy [14]. Due to the use of a large administrative database, the authors were not able to examine for history of cervical procedures. Interestingly, both Levine et al. (2016) and Quinones et al. (2018) included deliveries after 16 weeks in the analysis of subsequent sPTB. While this captures more individuals with cervical insufficiency, the inclusion of second trimester pregnancy loss may introduce additional confounders, and the data from deliveries at this gestation may be limited and inconsistent. Furthermore, an earlier study of women with cervical insufficiency (n=49) by Vyas et al. (2006) found that a previous prolonged second stage was a predictor of cervical insufficiency, along with a prior precipitous delivery [7]. These outcomes were not seen in our study, although it is possible that an increased cut-off of 3 h and the inclusion of non-viable subsequent deliveries as early as 16 weeks is required to demonstrate this association.

Second stage caesarean section

The rate of subsequent sPTB in women with an initial second stage of labour caesarean section was 3.8%, with an adjusted odds ratio of 3.42, however this did not reach statistical significance in this cohort. Risk factors for a second stage caesarean section were older maternal age and having an induction of labour. Risk factors for a first stage of labour caesarean section were also older maternal age, maternal diabetes, previous cervical surgery and having an induction of labour. The risk factors of older maternal age and diabetes were in accordance with previous studies, while cervical surgery has not previously been elicited as a risk factor [15]. Furthermore, the relationship between induction of labour and emergency caesarean section has become a contentious area, a recent randomised control trial found induction of labour in low-risk nulliparous women at 39 weeks reduced the risk of caesarean delivery [18].

Our findings are supportive of previous studies however cannot make any inferences as it did not reach statistical significance. Levine et al. (2015) found a 6-fold increase in subsequent sPTB rate with an initial second stage of labour caesarean section, but also had large confidence intervals due to the small incidence of sPTB and second stage caesarean section (n=37). Wood et al. (2017) performed a large retrospective cohort study using the Canadian database, which found a 1.5-fold increase in subsequent sPTB <37 weeks for women with an initial second stage of labour caesarean section. There was a higher 2-fold increase for subsequent sPTB <32 weeks [12]. This study hypothesised that cervical injury may occur from unplanned cervical extension, but was unable to quantify the extent of this in their population due to the retrospective large-scale nature of the study [19]. Other maternal risk factors such as ethnicity, BMI or history of previous cervical procedures were not examined in this cohort.

The strengths of our study are the large number of women with two consecutive deliveries at a single tertiary centre. There were relatively consistent medical records and protocols over the 4-year study period. As this was a planned retrospective analysis with a large initial dataset, we were able to specify the inclusion of only nulliparous women in the index pregnancy to ensure greater homogeneity within the cohort and exclude additional confounders such as number of prior deliveries, mode of delivery, and complications. Similarly, our study inclusion criteria required two consecutive singleton pregnancies to ensure multiple pregnancy did not confound the subsequent PTB rate. Finally, the extraction of additional variables such as maternal demographics and history of cervical procedures were imperative to allow for consideration of potential confounders for changes in cervical integrity.

Despite the large number of deliveries meeting inclusion criteria, there was a relatively small number of second stage of labour caesarean sections (n=26). The interpregnancy interval was limited to less than 4 years due to the 4-year study period. Future studies with an extended study period and a larger number of women are required for a higher-powered analysis of the second stage of labour caesarean section. A higher-powered study could also allow for sub-analysis of the prolonged second stage at additional time points of 1, 2, 3 and 4 h. Another limitation relates to the retrospective nature of this study, which may result in inconsistencies in data entry. A prospective study could ensure additional risk factors for PTB, such as uterine malformations or uterine evacuation, are included accurately.

Conclusions

In our population of nulliparous women with two consecutive singleton pregnancies, there was no association between a prolonged second stage of labour >2 h and subsequent sPTB. These findings have implications for reassuring women during counselling in the subsequent pregnancy and suggest that effects of a prolonged second stage of labour of >2 h on cervical integrity are not clinically significant enough to provide routine additional screening or interventions in the subsequent pregnancy. In our population, there was also no significant association between a second stage of labour caesarean section and subsequent sPTB when compared with first stage caesarean sections and vaginal deliveries, however further studies are required to clarify this with consideration of additional information such as surgical technique and complications.

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Informed consent: The institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee approved of this low risk research project and granted a waiver of consent to enable access to confidential information for the purposes of research without consent.

Ethical approval: The institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (Reference number: LNR/2020/QRBW/62589).

References

1. AIHW. Australia’s health 2018. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018.10.21820/23987073.2018.2.80Search in Google Scholar

2. Stoll, BJ, Hansen, NI, Bell, EF, Shankaran, S, Laptook, AR, Walsh, MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010;126:443–56. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2959.Search in Google Scholar

3. Mercer, BM, Goldenberg, RL, Moawad, AH, Meis, PJ, Iams, JD, Das, AF, et al. The preterm prediction study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:1216–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70111-0.Search in Google Scholar

4. Beta, J, Akolekar, R, Ventura, W, Syngelaki, A, Nicolaides, KH. Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery from maternal factors, obstetric history and placental perfusion and function at 11-13 weeks. Prenat Diagn 2011;31:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.2662.Search in Google Scholar

5. Goldenberg, RL, Culhane, JF, Iams, JD, Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60074-4.Search in Google Scholar

6. Cnattingius, S, Villamor, E, Johansson, S, Edstedt Bonamy, AK, Persson, M, Wikstrom, AK, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. J Am Med Assoc 2013;309:2362–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6295.Search in Google Scholar

7. Vyas, NA, Vink, JS, Ghidini, A, Pezzullo, JC, Korker, V, Landy, HJ, et al. Risk factors for cervical insufficiency after term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:787–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.069.Search in Google Scholar

8. WHO. WHO recommendation on definition and duration of the second stage of labour. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

9. ACOG. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1. Washington: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

10. RANZCOG. Provision of routine intrapartum care in the absence of pregnancy complications Melbourne. Australia: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

11. Sciaky-Tamir, Y, Shrim, A, Brown, RN. Prolonged second stage of labour and the risk for subsequent preterm birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:324–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30282-6.Search in Google Scholar

12. Wood, SL, Tang, S, Crawford, S. Cesarean delivery in the second stage of labor and the risk of subsequent premature birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.006. e1- e10.Search in Google Scholar

13. Levine, LD, Srinivas, SK. Length of second stage of labor and preterm birth in a subsequent pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.919. e1- e4.Search in Google Scholar

14. Quinones, JN, Gomez, D, Hoffman, MK, Ananth, CV, Smulian, JC, Skupski, DW, et al. Length of the second stage of labor and preterm delivery risk in the subsequent pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.031. e1- e8.Search in Google Scholar

15. Levine, LD, Sammel, MD, Hirshberg, A, Elovitz, MA, Srinivas, SK. Does stage of labor at time of cesarean delivery affect risk of subsequent preterm birth?. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.035. e1-7.Search in Google Scholar

16. Queensland Government. Births by Hospital. Brisbane; 2019. 2019.Search in Google Scholar

17. O’Connell, MP, Hussain, J, Maclennan, FA, Lindow, SW. Factors associated with a prolonged second state of labour--a case-controlled study of 364 nulliparous labours. J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;23:255–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144361031000098361.Search in Google Scholar

18. Grobman, WA, Rice, MM, Reddy, UM, Tita, ATN, Silver, RM, Mallett, G, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. N Engl J Med 2018;379:513–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1800566.Search in Google Scholar

19. Berghella, V, Gimovsky, AC, Levine, LD, Vink, J. Cesarean in the second stage: a possible risk factor for subsequent spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.019.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Cathy Z. Liu et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Methods of detection and prevention of preterm labour and the PAMG-1 detection test: a review

- Corner of Academy

- Long term alterations of growth after antenatal steroids in preterm twin pregnancies

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy: maternal and perinatal outcome data of 34 pregnant women hospitalised between May and October 2020

- Comparison of hematological parameters and perinatal outcomes between COVID-19 pregnancies and healthy pregnancy cohort

- The effect of mask use on maternal oxygen saturation in term pregnancies during the COVID-19 process

- Risk factors for pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism in Singapore

- Does the length of second stage of labour or second stage caesarean section in nulliparous women increase the risk of preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies?

- Reference range for C1-esterase inhibitor (C1 INH) in the third trimester of pregnancy

- Termination of pregnancy following a Down Syndrome diagnosis: decision-making process and influential factors in a Muslim but secular country, Turkey

- High dose vs. low dose oxytocin for labor augmentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Extremely high levels of alkaline phosphatase and pregnancy outcome: case series and review of the literature

- Cervical elastography strain ratio and strain pattern for the prediction of a successful induction of labour

- Original Articles – Fetus

- CD34 immunostain increases sensitivity of the diagnosis of fetal vascular malperfusion in placentas from ex-utero intrapartum treatment

- The ability of various cerebroplacental ratio thresholds to predict adverse neonatal outcomes in term fetuses exhibiting late-onset fetal growth restriction

- Obstetric and pediatric growth charts for the detection of late-onset fetal growth restriction and neonatal adverse outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- Bacterial stability with freezer storage of human milk

- Protein and genetic expression of CDKN1C and IGF2 and clinical features related to human umbilical cord length

- Short Communication

- A considerable asymptomatic proportion and thromboembolism risk of pregnant women with COVID-19 infection in Wuhan, China

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Methods of detection and prevention of preterm labour and the PAMG-1 detection test: a review

- Corner of Academy

- Long term alterations of growth after antenatal steroids in preterm twin pregnancies

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy: maternal and perinatal outcome data of 34 pregnant women hospitalised between May and October 2020

- Comparison of hematological parameters and perinatal outcomes between COVID-19 pregnancies and healthy pregnancy cohort

- The effect of mask use on maternal oxygen saturation in term pregnancies during the COVID-19 process

- Risk factors for pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism in Singapore

- Does the length of second stage of labour or second stage caesarean section in nulliparous women increase the risk of preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies?

- Reference range for C1-esterase inhibitor (C1 INH) in the third trimester of pregnancy

- Termination of pregnancy following a Down Syndrome diagnosis: decision-making process and influential factors in a Muslim but secular country, Turkey

- High dose vs. low dose oxytocin for labor augmentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Extremely high levels of alkaline phosphatase and pregnancy outcome: case series and review of the literature

- Cervical elastography strain ratio and strain pattern for the prediction of a successful induction of labour

- Original Articles – Fetus

- CD34 immunostain increases sensitivity of the diagnosis of fetal vascular malperfusion in placentas from ex-utero intrapartum treatment

- The ability of various cerebroplacental ratio thresholds to predict adverse neonatal outcomes in term fetuses exhibiting late-onset fetal growth restriction

- Obstetric and pediatric growth charts for the detection of late-onset fetal growth restriction and neonatal adverse outcomes

- Original Articles – Neonates

- Bacterial stability with freezer storage of human milk

- Protein and genetic expression of CDKN1C and IGF2 and clinical features related to human umbilical cord length

- Short Communication

- A considerable asymptomatic proportion and thromboembolism risk of pregnant women with COVID-19 infection in Wuhan, China