Abstract

Objectives

Few studies have investigated the effect of growth hormone (GH) therapy on bone health and body composition in children with idiopathic short stature (ISS). Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the short-term effects of GH treatment on bone mineral density (BMD) and prepubertal body composition in children with ISS.

Methods

The study included 53 prepubertal children with ISS (mean age, 6.3 ± 1.5 years). Their BMD was compared to that of 20 healthy prepubertal children matched for chronological age. Of the 53 children with ISS, 11 received GH therapy for 1 year. Anthropometric measurements and bone age assessments were conducted, and body composition was analyzed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at 6-month intervals.

Results

At baseline, lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD Z scores, adjusted for height, showed no significant differences between the ISS and control groups. However, bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) Z scores were significantly lower in children with ISS compared to controls. Over 12 months of GH therapy, no significant changes were observed in lumbar spine or femoral neck height-adjusted BMD Z scores. Nevertheless, GH treatment led to a significant reduction in percent body fat for chronological age and an increase in lean body mass after 1 year.

Conclusions

Prepubertal children with ISS exhibited lower BMAD at the lumbar spine compared to healthy controls. Although short-term GH therapy did not significantly alter bone density, it positively impacted body composition. These findings provide valuable clinical insights into bone health and body composition in children with ISS.

Introduction

Growth hormone (GH) therapy is widely recognized for its primary role in promoting linear growth in children with growth hormone deficiencies [1], 2]. However, beyond its effects on height, GH has significant metabolic effects, influencing body composition and bone metabolism [3], 4]. These effects include promoting bone formation, reducing fat mass, and enhancing lean body mass (LBM), which are crucial for pediatric growth and development [5], 6].

Previous studies have reported that GH therapy increases bone density in children with growth hormone deficiency (GHD) [7]. Children with GHD often exhibit reduced bone mineral density (BMD) due to the essential role of GH in bone remodeling and mineralization [7], 8]. However, the effects of GH treatment on bone density and body composition in children with idiopathic short stature (ISS) remain underexplored [9], [10], [11], [12]. Unlike GHD, ISS is a heterogeneous condition without an identifiable cause, and the metabolic effects of GH in this population are not well-documented. Some studies have suggested that children with ISS may have reduced bone mineral density (BMD), underscoring the need for thorough bone health assessment in this population [11], 12]. Given the established role of GH in bone metabolism, its potential impact on bone health in ISS warrants further investigation.

This study aimed to investigate the effects of GH therapy on BMD and body composition in prepubertal children with ISS. Specifically, it compared the BMD and body composition in children with ISS and healthy controls and evaluated changes after 1 year of GH treatment.

Subjects and methods

Participants and study design

Participants included prepubertal children aged ≥4 years diagnosed with ISS between January 2010 and December 2023 at Ajou University Hospital. For ISS diagnosis, all of the following widely accepted conditions were required to be met: (i) height ≤3rd percentile for age and sex; and (ii) peak GH levels >7 ng/mL in response to at least two GH stimulation tests (clonidine, insulin, or levodopa) [13], 14]. Children with GH deficiency or other organic causes of short stature, such as genetic syndromes and small for gestational age, were excluded. Patients exhibiting signs of puberty were also excluded. The control group consisted of 20 healthy prepubertal children matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). They had no growth-related diseases but voluntarily underwent growth evaluation, including DXA scanning, after receiving sufficient explanation and providing written informed consent.

Baseline data, including height, weight, bone age, insulin, serum glucose, lipid profile, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels, were collected from clinical charts. Height was measured using a Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain, Crosswell, Crymych, UK) and weight was measured using a digital scale. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. The standard deviation scores (SDS) for height, weight, and BMI were based on the 2017 Korean National Growth Charts [15]. Pubertal status was assessed using the Tanner and Marshall method for genital development in male children and breast development in female children [16]. Insulin resistance was assessed using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). HOMA-IR was calculated using the formula: fasting insulin (μU/mL) × fasting glucose (mmol/L)/22.5.

Of the 53 participants, 11 underwent GH treatment for 1 year and remained in the prepubertal stage after GH treatment. The mean GH dose was 0.23 mg/kg/week. Height, weight, bone age, IGF-1 levels, bone density, and body composition were assessed after 1 year of GH treatment. The process of participant selection, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion criteria in a retrospective study. DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; GH, growth hormone; BMI, body mass index; GHD, growth hormone deficiency; NS, Noonan syndrome; PWS, Prader–Willi syndrome; TS, Turner syndrome.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)

Overall body composition, including LBM, percent body fat, and fat mass, were assessed in all subjects using a Lunar Prodigy (General Electric, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA). DEXA scans were performed within one week of the initial diagnosis in patients with ISS. BMD (g/cm2) at the lumbar spine segments L1–L4 (LS) and the femoral neck (FN), as well as bone mineral content (BMC, g), were measured. To adjust for body size, bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) was calculated using the following formula: BMAD=BMD (LS) × 4/(π × width) [17]. The Z-scores of BMD for each site and body composition were calculated based on reference data from healthy Korean children and adolescents, adjusted for height-for-age [18], 19]. Scans were conducted by a single trained operator, with participants carefully repositioned for each scan to minimize errors caused by measurement geometry changes. The coefficient of variation for repeated measurements was less than 1 % for LS and FN.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). To assess differences between patients and healthy controls, independent t-test was performed. To evaluate within-group changes in bone density and body composition, a paired t-test was conducted. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless stated otherwise.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the ISS group and healthy controls are summarized in Table 1. At baseline, the ISS group exhibited significantly lower height and weight Z-scores than control group did (p<0.001). Sex distribution and the BMI SDS were not significantly different between the two groups.

Baseline auxological and metabolic parameters of idiopathic short stature and healthy control.

| Variable | ISS (n=53) | Controls (n=20) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 0.448 |

| Sex, n (male, %) | 26 (49 %) | 10 (50 %) | |

| Height SDS | −2.35 ± 0.42 | −0.76 ± 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Weight SDS | −2.09 ± 0.89 | −0.76 ± 1.05 | <0.001 |

| BMI SDS | −0.55 ± 0.98 | −0.40 ± 1.04 | 0.579 |

| Bone age, year | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| BA-CA, year | −1.4 ± 0.5 | −0.3 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| IGF-1, mg/mL | 194.2 ± 79.2 | 233.9 ± 73.6 | 0.056 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 166.2 ± 24.9 | 165.5 ± 27.9 | 0.921 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 57.4 ± 11.5 | 60.0 ± 10.7 | 0.387 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 94.3 ± 23.3 | 94.2 ± 24.3 | 0.984 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 72.7 ± 30.7 | 56.7 ± 22.2 | 0.037 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 89.4 ± 7.3 | 87.8 ± 4.6 | 0.366 |

| Fasting insulin, μU/mL | 4.0 ± 2.7 | 4.9 ± 2.9 | 0.241 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.90 ± 0.64 | 1.06 ± 0.63 | 0.340 |

-

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ISS, idiopathic short stature; SDS, standard deviation score; BMI, body mass index; BA, bone age; CA, chronological age; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

The BMAD Z-scores were significantly lower in the ISS group (p=0.004), with lower BMC and LBM (p<0.001 for both), compared with the control group (Table 2). However, the BMD Z-scores for LS and FN, adjusted for age, sex, height, and the BMI SDS, did not significantly differ between the patients and healthy controls.

Baseline bone mineral density and body composition of idiopathic short stature and healthy control.

| Variable | ISS (n=53) | Controls (n=20) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMDht Z-scoresa | |||

| Lumbar spine | −0.25 ± 1.00 | 0.12 ± 0.75 | 0.132 |

| Femur neck | 0.03 ± 1.30 | 0.07 ± 1.22 | 0.899 |

| BMAD Z scores | −0.44 ± 1.18 | 0.53 ± 1.37 | 0.004 |

| Bone mineral content, g | 561.2 ± 134.1 | 683.6 ± 94.8 | <0.001 |

| Lean body mass, kg | 13.0 ± 2.6 | 15.0 ± 1.7 | 0.003 |

| Fat mass, kg | 3.0 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 0.025 |

| Percent fat, % | 17.4 ± 5.8 | 20.9 ± 7.7 | 0.040 |

-

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). aThe Z-scores for BMD at each site were calculated using data on healthy Korean children and adolescents after adjusting for height-for-age. ISS, idiopathic short stature; BMDht, height-adjusted bone mineral density; BMAD, bone mineral apparent density.

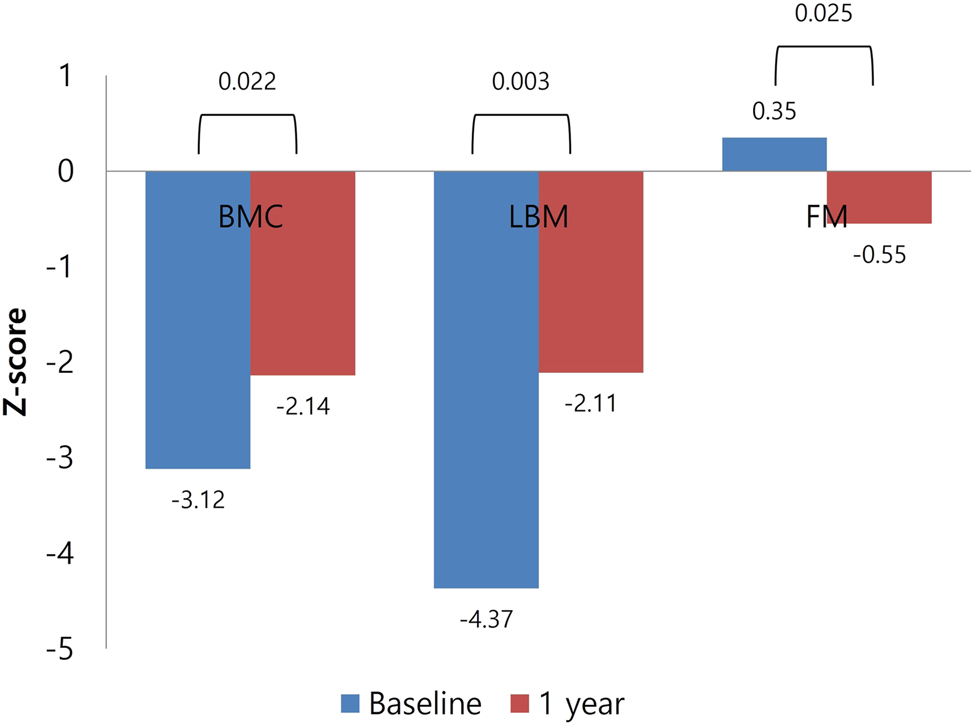

After 1 year of GH treatment, significant improvements in body composition were observed. No significant changes in the height-adjusted BMD (BMDht) Z-scores for LS or FN were observed after 1 year of GH treatment (p=0.664 and p=0.710, respectively) nor were significant improvements in the BMAD Z-scores detected (p=0.568) (Figure 2). However, LBM Z-scores increased significantly from −4.37 ± 0.6 to −2.11 ± 0.7 (p=0.003), whereas fat mass Z-scores showed a trend toward reduction (from 0.35 ± 0.2 to −0.55 ± 0.3 kg, p=0.025) (Figure 3). Body fat percentage also significantly decreased, from 18.4 ± 3.1 % to 14.7 ± 10.8 % (p=0.012). Additionally, insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) significantly increased after 1 year of GH treatment. Lipid profiles – including total cholesterol, low- and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides – did not differ significantly between baseline and 1 year after GH treatment (Table 3).

Changes in parameters of bone mineral density for chronological age. BMD, bone mineral density; BMAD, bone mineral apparent density; LS, lumbar spine; FN, femur neck.

Changes in parameters of body composition for chronological age. BMC, bone mineral content; LBM, lean body mass; FM, fat mass.

The change in metabolic parameters at baseline and after 1 year of growth hormone therapy (n=11).

| Variable | Baseline | 1 year treatment | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Height SDS | −2.26 ± 0.44 | −1.42 ± 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Weight SDS | −1.85 ± 0.8 | −1.25 ± 0.75 | <0.001 |

| BMI SDS | −0.35 ± 0.87 | −0.54 ± 0.90 | 0.013 |

| Bone age, year | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| BA-CA, year | −1.5 ± 0.4 | −1.5 ± 0.7 | 0.956 |

| IGF-1, mg/mL | 208.7 ± 79.0 | 400.9 ± 136.3 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 165.8 ± 28.0 | 164.0 ± 20.7 | 0.718 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 48.9 ± 7.7 | 49.6 ± 8.9 | 0.825 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 99.4 ± 25.2 | 100.4 ± 18.5 | 0.823 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 88.5 ± 33.7 | 69.9 ± 40.8 | 0.220 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 92.0 ± 8.0 | 93.5 ± 5.4 | 0.485 |

| Fasting insulin, μU/mL | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 7.3 ± 4.9 | 0.002 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.91 ± 0.77 | 1.74 ± 1.28 | 0.003 |

-

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). SDS, standard deviation score; BMI, body mass index; BA, bone age; CA, chronological age; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; HDL; high-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

Discussion

In this study, the BMAD of the LS in prepubertal children with ISS was significantly lower than that in healthy controls. Furthermore, body composition parameters, including BMC, LBM, and fat mass, were all reduced in the ISS group. After 1 year of GH therapy, body composition improved significantly, with increased LBM and reduced fat mass. However, no significant changes in the BMDht at the LS or FN or BMAD were detected.

To date, studies evaluating bone density or the outcomes of GH therapy in patients with ISS remain limited. Lanes et al. [11] reported that, in 16 patients with ISS who exhibited decreased LS BMD before GH therapy, the BMD improved to levels comparable to those in healthy controls after 3 years of treatment. However, Ogle et al. [20] demonstrated that the bone density measured at L2–L4 showed a non-significant increase after 6 months of GH treatment in patients with short stature without GH deficiency. Another study by Hogler et al. [10] reported reduced volumetric BMD at the LS in prepubertal children with ISS compared with healthy controls, with no significant change observed after 2 years of GH therapy, consistent with our findings. These results suggest that the effects of GH on skeletal mineralization during short-term treatment are limited. This may reflect the body’s prioritization of growth and muscle accretion over changes in bone density [5].

GH plays a crucial role in bone density by stimulating IGF-1 production, which enhances osteoblast proliferation, promotes collagen synthesis, facilitates bone matrix mineralization, and modulates bone resorption, thereby increasing bone mass and strength [21], 22]. GH also regulates calcium and phosphate metabolism, which are essential for bone mineralization [23]. Through these mechanisms, GH therapy is expected to improve bone density not only in patients with GHD but also in those with ISS. However, it is essential to consider that the effects of GH on bone density might become more evident with prolonged treatment durations.

Although the exact mechanism underlying reduced bone density in prepubertal children with ISS is not well understood, accumulating clinical reports suggest that these children may be at increased risk of low BMD [10]. One hypothesis is that, despite normal GH secretion, some ISS patients may exhibit subtle impairments in GH signaling or IGF-1 generation, raising the possibility of a partial GH resistance phenotype that could contribute to reduced bone formation by impairing IGF-1-mediated osteoblast activation and subsequent bone matrix synthesis [11], 24].

Another possible explanation is that short stature is commonly associated with smaller bone size, which may reduce mechanical loading on the skeleton and contribute to lower BMD [25]. However, smaller bone size can also lead to lower areal BMD measurements due to the two-dimensional nature of DEXA assessments, making it difficult to distinguish true reductions in bone density from size-related measurement artifacts. The BMAD and height-adjusted BMD partially mitigate the confounding effects of short stature; however, they are not consistently effective across all age ranges [26]. Consequently, interpreting bone density in children with short stature remains challenging.

Although children with ISS are not traditionally classified as high risk for pediatric osteoporosis, assessing BMD in this population has important clinical relevance. Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the acquisition of peak bone mass, a key predictor of long-term skeletal health. Inadequate bone accrual during this window has been associated with increased risks of osteoporosis and fractures in adulthood [27], 28]. Therefore, early assessment of BMD is important in patients with ISS to identify potential reductions in bone density and to support the maintenance of normal bone mineralization. In addition, decisions regarding GH therapy should not be based solely on linear growth potential but must also incorporate considerations of bone health.

In our study, body composition, including LBM, fat mass, and percent body fat, improved after 1 year of GH treatment in patients with ISS. Similar findings have been documented in other research. Hannon et al. [29] observed that short-term GH treatment in adolescents with ISS resulted in an increased LBM and fat reduction. Additionally, Decker et al. [9] demonstrated that, after 2 years of GH treatment, patients with ISS exhibited increased LBM and reduced fat mass. Among metabolic parameters, insulin resistance significantly increased after GH treatment, with higher insulin levels likely representing a physiological response to GH treatment [4]. Similar findings have been consistently reported in other large observational registries of GH treatment, such as the KIGS database and the NordiNet and ANSWER Program [2], [30], [31], [32].

This study has certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size was relatively small, potentially limiting the statistical power to detect subtle effects of GH treatment on bone density and body composition. Larger studies with more participants are necessary to draw more robust conclusions about the impact of GH on bone health in children with ISS. In addition, the small number of GH-treated participants in this study may reflect financial barriers to GH therapy for ISS. Since GH treatment for ISS is often not covered by insurance in Korea, financial constraints may have contributed to the limited number of treated patients.

Second, bone turnover markers were not assessed in this study. These markers could have provided additional insights into the mechanisms of the effects of GH on bone metabolism and clarified the lack of significant changes in bone density despite improvements in body composition. Including biochemical markers of bone turnover, such as osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, and type I collagen markers, could have offered a more comprehensive evaluation of bone remodeling during GH therapy. Lastly, the duration of GH treatment in this study was relatively short, lasting only 1 year. As changes in bone density are typically gradual, longer follow-up periods may be required to observe the full effects of GH on bone mineralization. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the effects of GH treatment on bone density and body composition in children with ISS. A notable strength of this research is its focus on ISS, a condition not extensively studied regarding bone health and body composition, particularly in the context of short-term GH therapy. Although numerous studies have investigated the effects of GH in GHD, research specifically addressing ISS is scarce. This study contributes to the understanding of ISS by offering clinical data on bone density and body composition in this patient population.

In conclusion, GH therapy in children with ISS improves body composition; however, its short-term effects on bone density are limited. Future studies, especially those with extended follow-up durations, are necessary to explore the role of GH in bone health further and clarify long-term skeletal outcomes in children with ISS.

-

Research ethics: The Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital approved the clinical and genetic studies (AJOUIRB-SMP-2012-054). All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

-

Informed consent: All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Our datasets were obtained from participants who consented to the use of their individual clinical and genetic data for biomedical research.

-

Author contributions: HS Lee, MH Cho, and JS Hwang designed the study. HS Lee was responsible for the pipeline construction. MH Cho and HS Lee drafted the manuscript. HS Lee, MH Cho, and JS Hwang refined the final version of the paper. HS Lee, YS Shim, and JS Hwang discussed the data and provided advice. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: All relevant data are included in the manuscript. However, the raw data analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, as the owners gave their written consent only to use the data for the current study after IRB approval. The datasets used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Danowitz, M, Grimberg, A. Clinical indications for growth hormone therapy. Adv Pediatr 2022;69:203–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yapd.2022.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Geffner, ME, Ranke, MB, Wajnrajch, MP. An overview of growth hormone therapy in pediatric cases documented in the Kabi International growth study (Pfizer International growth database). Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2024;29:3–11. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2346206.103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Lee, HS. The effects of growth hormone treatment on height in short children. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2022;27:1–2. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2221055edi01.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Dahlgren, J. Metabolic benefits of growth hormone therapy in idiopathic short stature. Horm Res Paediatr 2011;76:56–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000330165.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Tritos, NA, Klibanski, A. Effects of growth hormone on bone. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2016;138:193–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.10.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Mukherjee, A, Murray, RD, Shalet, SM. Impact of growth hormone status on body composition and the skeleton. Horm Res 2004;62:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000080497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Ferruzzi, A, Vrech, M, Pietrobelli, A, Cavarzere, P, Zerman, N, Guzzo, A, et al.. The influence of growth hormone on pediatric body composition: a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1093691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1093691.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Yakar, S, Rosen, CJ, Beamer, WG, Ackert-Bicknell, CL, Wu, Y, Liu, JL, et al.. Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. J Clin Investig 2002;110:771–81. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci0215463.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Decker, R, Albertsson-Wikland, K, Kristrom, B, Nierop, AF, Gustafsson, J, Bosaeus, I, et al.. Metabolic outcome of GH treatment in prepubertal short children with and without classical GH deficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73:346–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03812.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Hogler, W, Briody, J, Moore, B, Lu, PW, Cowell, CT. Effect of growth hormone therapy and puberty on bone and body composition in children with idiopathic short stature and growth hormone deficiency. Bone 2005;37:642–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2005.06.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Lanes, R, Gunczler, P, Esaa, S, Weisinger, JR. The effect of short- and long-term growth hormone treatment on bone mineral density and bone metabolism of prepubertal children with idiopathic short stature: a 3-year study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57:725–30. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01614.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Lanes, R, Gunczler, P, Weisinger, JR. Decreased trabecular bone mineral density in children with idiopathic short stature: normalization of bone density and increased bone turnover after 1 year of growth hormone treatment. J Pediatr 1999;135:177–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70019-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Collett-Solberg, PF, Ambler, G, Backeljauw, PF, Bidlingmaier, M, Biller, BMK, Boguszewski, MCS, et al.. Diagnosis, genetics, and therapy of short stature in children: a growth hormone research society international perspective. Horm Res Paediatr 2019;92:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502231.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Binder, G, Reinehr, T, Ibáñez, L, Thiele, S, Linglart, A, Woelfle, J, et al.. GHD diagnostics in Europe and the US: an audit of national guidelines and practice. Horm Res Paediatr 2019;92:150–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503783.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Kim, JH, Yun, S, Hwang, SS, Shim, JO, Chae, HW, Lee, YJ, et al.. The 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents: development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J Pediatr 2018;61:135–49. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2018.61.5.135.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Wheeler, MD. Physical changes of puberty. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 1991;20:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-8529(18)30279-2.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Kroger, H, Vainio, P, Nieminen, J, Kotaniemi, A. Comparison of different models for interpreting bone mineral density measurements using DXA and MRI technology. Bone 1995;17:157–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s8756-3282(95)00162-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Zemel, BS, Leonard, MB, Kelly, A, Lappe, JM, Gilsanz, V, Oberfield, S, et al.. Height adjustment in assessing dual energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements of bone mass and density in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1265–73. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2057.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Lim, JS, Hwang, JS, Lee, JA, Kim, DH, Park, KD, Cheon, GJ, et al.. Bone mineral density according to age, bone age, and pubertal stages in Korean children and adolescents. J Clin Densitom Off J Int Soc Clin Densitom 2010;13:68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2009.09.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Ogle, GD, Rosenberg, AR, Calligeros, D, Kainer, G. Effects of growth hormone treatment for short stature on calcium homeostasis, bone mineralisation, and body composition. Horm Res 1994;41:16–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000183871.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Amato, G, Izzo, G, La Montagna, G, Bellastella, A. Low dose recombinant human growth hormone normalizes bone metabolism and cortical bone density and improves trabecular bone density in growth hormone deficient adults without causing adverse effects. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:27–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.1996.tb02056.x.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Saggese, G, Baroncelli, GI, Bertelloni, S, Barsanti, S. The effect of long-term growth hormone (GH) treatment on bone mineral density in children with GH deficiency. Role of GH in the attainment of peak bone mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:3077–83. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.81.8.8768878.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Fatayerji, D, Mawer, EB, Eastell, R. The role of insulin-like growth factor I in age-related changes in calcium homeostasis in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4657–62. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.85.12.7031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Savage, MO, Storr, HL. GH resistance is a component of idiopathic short stature: implications for rhGH therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:781044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.781044.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Mullender, MG, Huiskes, R. Proposal for the regulatory mechanism of Wolff’s law. J Orthop Res 1995;13:503–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.1100130405.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Kindler, JM, Lappe, JM, Gilsanz, V, Oberfield, S, Shepherd, JA, Kelly, A, et al.. Lumbar spine bone mineral apparent density in children: results from the bone mineral density in childhood study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:1283–92. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-01693.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Weaver, CM, Gordon, CM, Janz, KF, Kalkwarf, HJ, Lappe, JM, Lewis, R, et al.. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:1281–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3440-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Ferjani, HL, Cherif, I, Nessib, DB, Kaffel, D, Maatallah, K, Hamdi, W. Pediatric and adult osteoporosis: a contrasting mirror. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2024;29:12–18. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2346114.057.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Hannon, TS, Danadian, K, Suprasongsin, C, Arslanian, SA. Growth hormone treatment in adolescent males with idiopathic short stature: changes in body composition, protein, fat, and glucose metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:3033–9. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0308.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Maghnie, M, Ranke, MB, Geffner, ME, Vlachopapadopoulou, E, Ibáñez, L, Carlsson, M, et al.. Safety and efficacy of pediatric growth hormone therapy: results from the full KIGS Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022;107:3287–301. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgac517.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Sävendahl, L, Polak, M, Backeljauw, P, Blair, JC, Miller, BS, Rohrer, TR, et al.. Long-term safety of growth hormone treatment in childhood: two large observational studies: NordiNet IOS and ANSWER. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021;106:1728–41. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab080.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Lee, PA, Sävendahl, L, Oliver, I, Tauber, M, Blankenstein, O, Ross, J, et al.. Comparison of response to 2-years’ growth hormone treatment in children with isolated growth hormone deficiency, born small for gestational age, idiopathic short stature, or multiple pituitary hormone deficiency: combined results from two large observational studies. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2012;2012:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2012-22.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Pubertal disorders in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systemic review

- Hormonal therapy for impaired growth due to pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis

- Mini Review

- Neonatal hypoglycaemia in the offsprings of parents with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)

- Original Articles

- Cord blood metabolomic profiling in high risk newborns born to diabetic, obese, and overweight mothers: preliminary report

- Impact of Covid-19 on children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: lifestyle, telecommunication service, and quality of life

- The diagnostic utility of bioelectrical impedance analysis in distinguishing precocious puberty from premature thelarche

- Infant gonadotropins predict spontaneous puberty in girls with Turner syndrome

- Bioinformatics analysis explores key pathways and hub genes in central precocious puberty

- Impact of growth hormone therapy on bone and body composition in prepubertal children with idiopathic short stature

- Presence of hyperandrogenemia in cases evaluated due to menstrual irregularity, the effect of clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenemia on polycystic ovary syndrome

- Cardiac function in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Short Communication

- Clinical and genetic insights into congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia: a case series from a tertiary care center in North India

- Case Reports

- Two families, two pathways: a case series of 46, XY DSD with 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and isolated 17,20-lyase deficiency due to novel CYB5A variant

- Coexistence of SRY, DHX37 and POR gene variants in a patient with 46,XY disorder of sex development

- Diabetes, macrocytosis, and skin changes in large-scale mtDNA deletion

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Pubertal disorders in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systemic review

- Hormonal therapy for impaired growth due to pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis

- Mini Review

- Neonatal hypoglycaemia in the offsprings of parents with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY)

- Original Articles

- Cord blood metabolomic profiling in high risk newborns born to diabetic, obese, and overweight mothers: preliminary report

- Impact of Covid-19 on children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: lifestyle, telecommunication service, and quality of life

- The diagnostic utility of bioelectrical impedance analysis in distinguishing precocious puberty from premature thelarche

- Infant gonadotropins predict spontaneous puberty in girls with Turner syndrome

- Bioinformatics analysis explores key pathways and hub genes in central precocious puberty

- Impact of growth hormone therapy on bone and body composition in prepubertal children with idiopathic short stature

- Presence of hyperandrogenemia in cases evaluated due to menstrual irregularity, the effect of clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenemia on polycystic ovary syndrome

- Cardiac function in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Short Communication

- Clinical and genetic insights into congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia: a case series from a tertiary care center in North India

- Case Reports

- Two families, two pathways: a case series of 46, XY DSD with 17α-hydroxylase deficiency and isolated 17,20-lyase deficiency due to novel CYB5A variant

- Coexistence of SRY, DHX37 and POR gene variants in a patient with 46,XY disorder of sex development

- Diabetes, macrocytosis, and skin changes in large-scale mtDNA deletion