Abstract

Objectives

Transcobalamin II (TC) is an essential plasma protein for the absorption, transportation, and cellular uptake of cobalamin. TC deficiency presents in the first year of life with failure to thrive, hypotonia, lethargy, diarrhea, pallor, mucosal ulceration, anemia, pancytopenia, and agammaglobulinemia. Herein, we present TC deficiency diagnosed in two cases (twin siblings) with a novel variant in the TCN2 gene.

Case presentation

4-month-old twins were admitted with fever, respiratory distress, vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive. Physical examination findings revealed developmental delay and hypotonia with no head control, and laboratory findings were severe anemia, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. Despite normal vitamin B12 and folate levels, homocysteine and urine methylmalonic acid levels were elevated in both patients. Bone marrow examinations revealed hypocellular bone marrow in both cases. The patients had novel pathogenic homozygous c.241C>T (p.Gln81Ter) variant in the TCN2 gene. In both cases, with intramuscular hydroxycobalamin therapy, laboratory parameters improved, and a successful clinical response was achieved.

Conclusions

In infants with pancytopenia, growth retardation, gastrointestinal manifestations, and immunodeficiency, the inborn error of cobalamin metabolism should be kept in mind. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for better clinical outcomes. What is new? In literature, to date, less than 50 cases with TC deficiency were identified. In this report, we presented twins with TCN2 gene mutation. Both patients emphasized that early and aggressive treatment is crucial for achieving optimal outcomes. In this report, we identified a novel variation in TCN2 gene.

Introduction

Cobalamin (vitamin B12, Cbl) plays a crucial role in the metabolism and DNA synthesis of proliferating cells [1]. When pancytopenia presents in young infants with normal vitamin B12 and folate levels, inherited disorders of cobalamin or folate metabolism should be kept in mind.

Transcobalamin II (TC) is an essential plasma protein for the absorption, transportation, and cellular uptake of cobalamin. TC deficiency was initially described in 1971. It is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the TCN2 gene and usually presents in the first year of life with failure to thrive, hypotonia, lethargy, diarrhea, pallor, mucosal ulceration, anemia, pancytopenia, and agammaglobulinemia. Besides, although rarely, the disease may resemble severe combined immunodeficiency disease and leukemia [2], [3].

The diagnosis of TC deficiency is suspected based on megaloblastic anemia and accumulation of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid, whereas vitamin B12 and folate levels are normal [3]. Treatment with parenteral cobalamin is highly effective in clinical and biological manifestations. Clinical manifestations are reversible if periodic cobalamin supplementation is initiated early [3], [4]. Delayed or inadequate treatment can all lead to neurological deficits, including developmental delay, neuropathy, myelopathy, and retinal degeneration [5], [6]. To date, almost 60 patients with TC deficiency have been reported from different countries. Twenty-five pathogenic mutations in TCN2 gene have been identified (Table 2) [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20].

Herein, we present the clinical and laboratory findings and the outcomes of two affected siblings with a novel variant in the TCN2 gene to emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Cases presentation

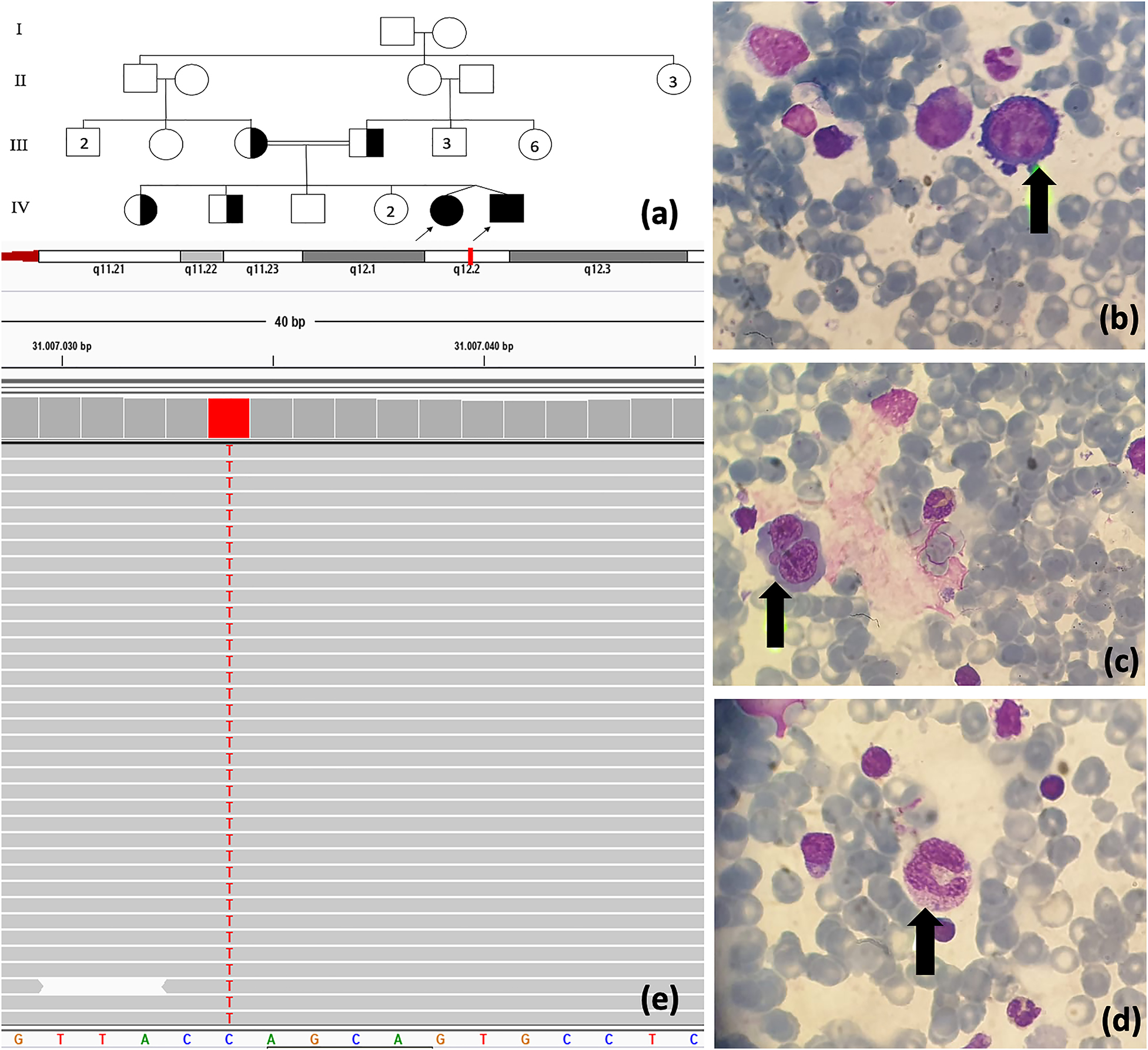

The twin siblings were born to consanguineous parents at 32 weeks’ gestation (Figure 1A). Pregnancy history was unremarkable. No complication during pregnancy was declared. They had been followed up in a newborn intensive care unit because of prematurity for 50 days.

(A) The pedigree of cases. Megaloblastic changes in bone marrow aspiration: (B) giant pronormoblast, (C) binucleated normoblast, (D) giant myeloid. (E) TCN2 gene mutation analysis.

Case 1

A 4-month-old (corrected age: 2 months) female was admitted to our hospital with fever, respiratory distress, vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive.

In medical history, birth weight, length, and head circumference were 1445 g (10–25th percentile) and 42 cm (10–25th percentile), respectively. She had been followed up in a newborn intensive care unit because of prematurity for 50 days. She was discharged from intensive care unit with 2.8 kg (10–25th percentile) weight and 47 cm (10th percentile) length.

In physical examination, pallor, tachycardia, and growth retardation (weight: 3.8 kg, <3 percentile; length: 53 cm, 3–10th percentile) were detected. The patient was hypotonic with no head control. No dysmorphic appearance noted. The other system examination findings were all normal.

In laboratory investigation, bicytopenia was revealed (white blood cell count, 6.3 × 109/L; absolute neutrophil count, 0.85 × 109/L; hemoglobin level, 7.2 g/dL; platelet count, 156 × 109/L). Mean corpuscular volume (97.1 fL) showed macrocytic anemia. C-reactive protein level was 14 mg/mL (range, 0–5 mg/mL). Lymphocyte subsets were within the normal range. Low IgG (33.1 mg/dL), IgA (<27.8 mg/dL), and IgM (19.4 mg/dL) levels were noted (Table 1). Serum electrolyte levels, renal and liver function tests were within the normal range. Urine and stool analyses were normal. Bone marrow aspiration was performed to evaluate the hematological findings. Bone marrow smear revealed megaloblastic changes which include giant pronormoblasts, nucleocytoplasmic dissociation, giant myeloid cells, binucleated normoblasts, nucleocytoplasmic dissociation in normoblasts (Figure 1B–D). Owing to hypotonia and development delay, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and pattern of retarded myelination in white matter due to prematurity was revealed.

Laboratory findings of patients before and after hydroxy-Cbl treatment.

| Findings | Case 1 | Case 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis age | 4 months (CA: 2 months) | 4 months (CA: 2 months) | ||||||

| Gender | Female | Male | ||||||

| Symptoms at presentation | Fever, respiratory distress, vomiting, diarrhea and failure to thrive, hypotonia | Vomiting, diarrhea and failure to thrive, hypotonia | ||||||

| Parameters | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | ||||

| 4 months age (CA: 2 months) | One week after treatment | 7 months age (CA: 5 months) | 9 months age (CA: 7 months) | 4 months age (CA: 2 months) | One week after treatment | 7 months age (CA: 5 months) | 9 months age (CA: 7 months) | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 7.2 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 7.0 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 10.9 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 2.44 | 4.03 | 3.77 | 3.98 | 2.27 | 3.63 | 4.02 | 3.89 |

| MCV (fL) | 97.1 | 87.3 | 82.1 | 84.9 | 94 | 85.7 | 86.1 | 87.4 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.3 | 10.1 | 11.7 | 12.96 | 4.8 | 8.54 | 11.1 | 12.1 |

| ANC (109/L) | 0.85 | 2.96 | 4.5 | 3.44 | 0.58 | 3.3 | 4.11 | 4.32 |

| Plt (109/L) | 156 | 227 | 345 | 385 | 12 | 426 | 346 | 278 |

| Ig A (mg/dL) (1–5 months: 5.8–58; 6–8 months: 5.8–85.8) | <27.8 | 53.7 | 24.0 | 34.8 | <27.8 | 79.4 | 84.1 | 46.7 |

| IgG (mg/dL) (1–5 months: 270–792; 6–8 months: 268–898) | 33.1 | 719 | 666 | 385 | 32.9 | 452.0 | 667 | 518 |

| IgM (mg/dL) (1–5 months: 18.4–145; 6–8 months: 26.4–146.0) | 19.4 | 28.9 | 35.9 | 44.6 | <17.3 | 34.0 | 44.1 | 56.5 |

| CD3 (50–77%) | 81.4% | - | - | - | 83.7% | - | - | - |

| CD4 (33–58%) | 55% | - | - | - | 57.9% | - | - | - |

| CD8 (13–26%) | 25.6% | - | - | - | 27.7% | - | - | - |

| CD19 (10–33%) | 12.7% | - | - | - | 10.7% | - | - | - |

| CD16+56 (2–13%) | 4.6% | - | - | - | 5.1% | - | - | - |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) (200–900) | 777 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 | 446 | >2000 | >2000 | >2000 |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) (5–15) | 44.8 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 42.6 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 7.2 |

| Urine methylmalonic acid (μmol/L) (<3.6) | 756.4 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 843.1 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 1.8 |

CA, corrected age; Hb: hemoglobulin; RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; plt, platelets.

In the clinical follow-up, antimicrobial therapy initiated for pneumonia. Owing to anemia and low IgG levels, red blood cell transfusion and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusion were administrated. The patient started feeding with an amino acid–based formula. However, vomiting, diarrhea, anemia, and neutropenia persisted.

Further biochemical investigations revealed elevated serum homocysteine levels (44.8 mmol/L [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]) and elevated urine methylmalonic acid levels (756.4 μmol/L [<3.6]). Plasma ammonia and lactate levels were within the normal range. Serum vitamin B12 and folate levels were 777 pmol/L (147–664) and 16.6 nmol/L (11.3–47.6), respectively (Table 1). With all these findings, the inborn error of cobalamin metabolism was suspected, and hydroxy-Cbl (1 mg intramuscular [i.m.] once daily) initiated.

After 1-week 1 mg i.m. once daily hydroxy-Cbl treatment, hematologic parameters and homocysteine levels (5.1 mmol/L) normalized. Urine methylmalonic acid level decreased to 2.1 μmol/L. Immunoglobulin levels were improved (Table 1). No transfusion required. On the last admission to the outpatient clinic, at nine months old (corrected age: 7 months), neurological examination findings were normal. In Denver developmental screening test II, personal-social, fine motor–adaptive, language and gross motor skills were compatible with 6, 7, 7, and 8 months age, respectively. Growth parameters were at the 10–25th percentile, and the hematological parameters were within the normal range.

Case 2

A 4-month-old (corrected age: 2 months) male infant was admitted to our hospital with vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive.

In medical history, birth weight, length, and head circumference were 1200 g (<3rd percentile) and 39 cm (3–10th percentile), respectively. He had been followed up in a newborn intensive care unit because of prematurity for 50 days. He was discharged from intensive care unit with 2800 g (3–10th percentile) weight and 47 cm (3–10th percentile) length.

The physical examination findings were pallor, tachycardia, and growth retardation (weight: 3.6 kg, <3rd percentile; length: 54 cm (3–10th percentile)). The patient was hypotonic with no head control, and feeding difficulty was present. No dysmorphic appearance noted. The other system examination findings were all normal.

In laboratory evaluation, pancytopenia was revealed (white blood cell count, 4.8 × 109/L; absolute neutrophil count, 0.58 × 109/L; hemoglobin level, 7.0 g/dL; platelet count, 12 × 109/L). Mean corpuscular volume (94 fL) showed macrocytic anemia. Low IgG (32.9 mg/dL), IgA (<27.8 mg/dL), and IgM (<17.3 mg/dL) levels were detected. Lymphocyte subsets were unremarkable (Table 1). Serum electrolyte levels and liver and kidney function test results were within the normal range. Urine and stool analyses were normal. Giant pronormoblasts, nucleocytoplasmic dissociation, giant myeloid cells, binucleated normoblasts, nucleocytoplasmic dissociation in normoblasts were detected in bone marrow smear (Figure 1B–D). These findings were compatible with megaloblastic changes. Brain MRI showed pattern of retarded myelination in white matter due to prematurity.

In the clinical follow-up, red blood cell and platelet transfusions, and IVIG infusion were repeatedly administrated. However, no hematological improvement observed. Despite feeding with an amino acid–based formula, vomiting, diarrhea, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia persisted.

Further biochemical investigations revealed elevated serum homocysteine levels (42.6 mmol/L [<15]) and elevated urine methylmalonic acid levels (843.1 μmol/L). Plasma ammonia and lactate levels were within the normal range. Serum vitamin B12 and folate levels were 446 pmol/L (147–664) and 15.7 nmol/L (11.3–47.6), respectively (Table 1). Hydroxy-Cbl therapy (1 mg, i.m., once daily) initiated.

Hematologic parameters and homocysteine levels (5.5 mmol/L) normalized with the 1 week treatment of 1 mg i.m. once daily hydroxy-Cbl. Vomiting and diarrhea regressed, and immunoglobulin levels improved. Urine methylmalonic acid level decreased to 3.2 μmol/L (Table 1). In the clinical follow-up, no transfusions required. On the last admission to the outpatient clinic, at nine months old (corrected age: 7 months), neurological examination revealed normal findings. In Denver developmental screening test II, personal-social, fine motor–adaptive, language and gross motor skills were compatible with 7, 6, 6, and 7 months age, respectively. Growth parameters were at the 10–25th percentile, and hematological parameters were within the normal range with weekly i.m. hydroxy-Cbl treatment.

Genetic analysis

TCN2 gene mutation analysis was performed by sequencing of the coding exons and the exon-intron boundaries of the genes. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood cells with QIAGEN DNA Blood Mini Kit in accordance with the protocol provided with the kit. Sequencing was performed with MiSeq V2 chemistry on MiSeq instrument (Illumina, CA, USA). A novel mutation presented here was predicted to be disease causing by in silico analysis NextGENe software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA).

In both cases, novel pathogenic homozygous c.241C>T (p.Gln81Ter) variant in exon two of the TCN2 gene was revealed (Figure 1D). These mutations are predicted to be disease causing by in silico analysis software. Therefore, this variant might possibly be a likely pathogenic variant. The variant has not been reported in any public database (Genome Aggregation Database and Exome Aggregation Consortium Database).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, these cases are the first twins with TC deficiency in literature. Moreover, a novel likely pathogenic variant was introduced with this report. Although, clinical findings of our cases are not unique compare with previous cases, this report emphasize that early and intensive treatment is crucial for better clinical outcome.

In infants with severe anemia and pancytopenia, TC deficiency should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Most of the previously reported TC deficiency patients present with pancytopenia and anemia [3], [12] (Table 2). Moreover, the most common clinical feature of the disease is hematological complications. Trakadis et al. reported that 87.5% of patients have hematological findings, including anemia or pancytopenia [3]. Although the hematological findings are compatible with macrocytic anemia, vitamin B12 levels are typically within the normal range [2]. In our twins, we determined bicytopenia and pancytopenia with normal B12 level. Although hematological findings were resistant to transfusions, rapid response to Cbl treatment was observed.

Clinical presentation, laboratory findings, genetic results, and long-term outcomes of previous patients diagnosed with TC deficiency [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20].

| Patient no (family) | Gender | Diagnosis age | Symptoms and clinical findings | Treatment age | Treatment | Age at last visit | Long-term clinical findings | TCN2 gene mutation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 3 months | Agammaglobulinemia, megaloblastic bone marrow | 5.5 months | CN-Cbl 2 mg p.o. daily switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. twice a week Switched to OH-Cbl 2 mg i.m. weekly | 40 years | Normal | Homozygous c.348_349delTG | [4], [7] |

| 2(a) | F | 1 year | Pancytopenia | 1 year | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and 1 mg p.o. daily switched to 2 mg i.m. weekly and CN-Cbl 5 mg p.o. daily | 20 years | Normal | Homozygous c.427+2T>G | [8], [9] |

| 3(a) | F | 2 weeks | Pancytopenia | 2 weeks | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and 1 mg p.o. daily switched to 2 mg i.m. weekly and CN-Cbl 5 mg p.o. daily | 16 years | Normal | Homozygous c.427+2T>G | |

| 4(a) | F | 3 weeks | Pancytopenia | 3 weeks | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and 1 mg p.o. daily switched to 2 mg i.m. weekly and CN-Cbl 5 mg p.o. daily | 11.5 years | Normal | Homozygous c.427+2T>G | |

| 5(b) | M | 4 months | Hypotonia, FTT, vomiting, glossitis, megaloblastic anemia | 4 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. twice a week (poor compliance) | 27 years | Poor academic performance, attention deficit disorder Dropped out of high school. Works as salesman and lives with wife and children. | Homozygous c.927-930delTCTG 22q12.2 del involving exons 1 to 7 of TCN2 gene | [10] |

| 6(b) | M | Birth | Normal | In utero/Birth | Mom had OH-Cbl twice a week 1 mg i.m. during pregnancy OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. twice a week switched CN-Cbl 5 times a month | 22 years | Normal | Homozygous c.927-930delTCTG 22q12.2 del | [11] |

| 7(c) | M | 6 months | FTT, pancytopenia, neutropenia colitis. | 6 months | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. twice a week for 10 months switched to CN-Cbl p.o. daily Switched to OH-Cbl 10 mg p.o. daily and OH-Cbl 3 mg i.m weekly | 12 years | Average Math and nonverbal IQ; above average reading; reduced Attention, variable Language skills | Homozygous c.1195C>T (p.R399X) | [12] |

| 8(c) | F | 1 week | Normal | 1 week | CN-Cbl p.o. switched to OH-Cbl 5 mg p.o. daily and OH-Cbl 2 mg i.m. weekly | 9 years | Formal neuropsychological testing: Average in most domains, weak in reading comprehension | Homozygous c.1195C>T (p.R399X) | |

| 9(c) | F | 1 week | Normal | 1 week | CN-Cbl p.o. switched to OH-Cbl 3 mg p.o. daily and OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | 2 years | Normal | Homozygous c.1195C>T (p.R399X) | |

| 10(d) | F | 3 months | Vomiting, diarrhea, pancytopenia, weight loss | 3 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.v. daily for a week, OH-Cbl i.m. 1 mg 3 times a week OH-Cbl i.m. 1 mg weekly | 8.5 years | Normal | Homozygous c.330dupC | [13] |

| 11(d) | F | 3 days | Normal | 1 week | OH-Cbl i.m. 1 mg i.m. weekly | 5.5 years | No | Homozygous c.330dupC | |

| 12(e) | M | 11 months | FTT and recurrent respiratory tract infections, pancytopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia | 11 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and CN-Cbl 1 mg p.o daily switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. every 2 weeks at 6 y i.m. switched to every 3 weeks | 7 years | Difficulties in social interactions | Homozygous c.1106+1G>A | [14] |

| 13(e) | F | Birth | Normal | Birth | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and CN-Cbl 1 mg p.o. daily switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. every 2 weeks and CN-Cbl 1 mg p.o. daily | 4.5 years | Normal | Homozygous c.1106+1G>A | |

| 14 | F | 4 months | Acute gastroenteritis, glossitis, pallor, pancytopenia, megaloblastic bone marrow | 4 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily for 1 week switched to 1 mg every 4 weeks, betaine 500 mg p.o. twice a day and l-methionine 25 mg p.o. twice a day Switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. every 2 week and betaine 500 mg p.o. twice a day | 4 years | Need for speech therapy | Homozygous c.580+1G>C | [6] |

| 15 | F | 10 months | FTT, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia | 5 weeks | OH-Cbl i.m. twice a week switched to intranasal twice a week Switched to weekly Switched to 2 mg OH-Cbl p.o. daily Switched to OH-Cbl i.m. weekly | 4.5 years | Normal | c.497_498delTC c.1139dupA | |

| 16 | F | 23 days | Vomiting, pancytopenia, Megaloblastic anemia | 23 days | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg p.o. daily Switched to OH-Cbl IM 1 mg i.m. monthly | 15 years | Retinopathy with partial blindness, intellectual Disability | Homozygous c.497_498delTC | |

| 17 | F | 7 months | Development delay, hypotonia, myoclonic like movements, pallor, purpura, anemia, thrombocytopenia, megaloblastic, aplastic bone marrow | 8 months | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. monthly folate p.o. switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. 3 times a week | 32 years | School difficulties; stopped studies after 4 year of high school, but completed Professional formation. At 6, 7, 8, and 13 year Wechsler scale full IQ:62 | c.501_503delCCA c.1115_1116CA | |

| 18 | F | 3 months | FTT, diarrhea, vomiting | 3 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. 3 time a week switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m weekly | 2 years | Normal | Homozygous c.1236_1237del | |

| 19 | F | 3 weeks | FTT, diarrhea, vomiting, hypotonia, pancytopenia | 3 weeks | Folinic acid 15 mg p.o. daily and OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. 3 times a week | 18 months | Motor deficits | Homozygous c.940+303_1106+746del2152insCTGG (r.941_1105del; p.fs326X) | [15] |

| 20(f) | F | 6 weeks | FTT, pancytopenia | 8 weeks | Folic acid p.o. and OH-Cbl 1 mg p.o. | 9 years | Normal | Homozygous c.580+624A>T | |

| 21(f) | F | 6 weeks | FTT, vomiting | Folic acid p.o. and OH-Cbl 1 mg p.o. | 11 years | Normal | Homozygous c.580+624A>T | ||

| 22 | F | 7 months | FTT, hypotonia, fever, diarrhea pancytopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia | 8 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. 3 times a week and folate 10 mg p.o. switched to OH-Cbl p.o. 1 mg daily Switched OH-Cbl i.m. 1 mg 3 times a week | 12 years | IQ by WISC-II identified mild delays | c.423delC c.937C>T | [3] |

| 23 | F | 3 months | FTT, vomiting, hypotonia, pallor, vomiting | 2 months | OH-Cbl 1.5 mg i.m. 3 times a week and folinic acid 15 mg p.o. daily switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and folinic acid 7.5 mg twice a day | 14 years | Delayed speech and need for speech therapy ADHD | Homozygous c.940+ 283_286delTGGA; c.940+303_1106 +764del2152insCTGG | |

| 24 | M | 2 months | FTT, megaloblastic anemia | 2 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg p.o daily Switched back to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily | 11 years | ADHD | Homozygous c.497_498delTC | |

| 25 | M | 1 month | Normal | 6 weeks | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly (transiently switched to every 2 weeks for 3 weeks) | 6 years | Normal | Homozygous c.497_498delTC | |

| 26(g) | M | 3 months | FTT, diarrhea, hypotonia, pancytopenia, hypotonia, low T and B cell counts, megaloblastic bone marrow | 3 months | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily and folate 5 mg p.o. daily switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. 3 times a week and folate 1 mg 3 times a week | 27 months | Language delay | Homozygous c.1013_1014 delinsTAA (p.S338IfsX27) | |

| 27(g) | M | In utero | Normal | 1 week | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily | 7 months | Normal | Homozygous c.1013_1014 delinsTAA (p.S338IfsX27) | |

| 28 | F | 3 months | Pallor, weakness, dyspnea, tachypnea, feeding difficulty | 3 months | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily switched to twice a week Switched to 1 mg weekly | 2 years | Developmental delay | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del5304 | |

| 29 | M | 4 months | Pallor, weakness, feeding difficulty, FTT, petechiae | 4 months | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily switched to 1 mg twice a week Switched to 1 mg weekly; at 5 months switched to 1 mg every 2 weeks; at 8 months switched to 1 mg weekly | 25 months | Speech/language delay. | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del5304 | |

| 30 | F | 2 months | Pallor, fever, vomiting FTT | 2 months | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily switched to twice a week Switched to 1 mg weekly | 18 months | Normal | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del5304 | |

| 31 | F | 2.5 months | Pallor, feeding difficulty, petechiae, tachycardia | 2.5 months | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily switched to 1 mg twice a week Switched to 1 mg weekly | 26 months | Speech/language | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del5304 | |

| 32 | F | 2 months | Glossitis, megaloblastic anemia, FTT | 2.5 months | Cbl (type is unknown) i.m. daily, now OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | 29 years | Normal | Homozygous c.744delG | |

| 33 | F | 2 months | FTT, irritability, diarrhea pallor, petechial rash, hypotonia | N/A | OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily switched to every week and folic acid 1 mg p.o. daily | 4 years | Normal | Homozygous c.1106+1516_122+1231del | [16] |

| 34 | M | 28 days | FTT, vomiting, poor feeding, pancytopenia | N/A | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly and folic acid 1 mg p.o. daily | 6.5 years | N/A | c.1107-347_1222+981delin 364; this complex mutation appears to be a 1444-bp deletion that includes exon 8 and a 364-bp insertion | |

| 35 | F | 2 months | Diarrhea, vomiting, fever, pancytopenia, FTT | 2.5 months | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily, switched to CN-Clb twice weekly and folic acid 1 mg oral | 5 years | Normal | Homozygous c.106C>T. (Q36X) | |

| 36 | M | 3 months | FTT, poor feeding, pancytopenia | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. weekly and oral folic acid 1 mg/day | N/A | N/A | Homozygous c.1106+1516-1222+1231del | |

| 37 | F | 6 weeks | Fever, vomiting, diarrhea, FTT | OH-Cbl 5 mg i.m. daily for 5 days switched to OH-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | N/A | Homozygous c.949+303_c.1106+746del2152insCTGG | [17] | |

| 38(h) | M | 3 months | Sepsis, fever | 3 months | OH-Cbl 10 mg p.o. daily | 33 months | SD | Homozygous c.64+4A>T | [18] |

| 39(h) | M | 6 weeks | Fever, diarrhea, vomiting, oral stomatitis, FTT | 5 months | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | 10 years | Normal | Homozygous c.64+4A>T | |

| 40(i) | M | 8 weeks | Vomiting, diarrhea, pancytopenia | N/A | CN-Cbl, 1 mg i.m. twice a week and carnitine 75 to 100 mg/kg p.o. daily switched to methyl-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | 12 years | Delayed language and speech skills, ASD | Homozygous p.R227X (c.679C>T) | |

| 41(i) | M | Birth | Normal | Birth | CN-Cbl, 1 mg i.m. weekly switched to CN-Cbl, 1 mg i.m. monthly Switched to CN-Cbl, 1 mg i.m. weekly | 8 years | ASD | Homozygous p.R227X (c.679C>T) | |

| 42 | M | 4 months | Pallor, weakness, FTT, poor feeding, petechiae | N/A | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily for a week switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | Walking at 30 mo, SD (4-5 words) | Homozygous c.1106 + 1516_1222 +1231del | [5] |

| 43 | F | 3 months | Pallor, weakness, dyspnea, tachypnea, poor feeding | N/A | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily for a week switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | Walking close by 3 years, SD | Homozygous c.1106 + 1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 44 | F | 2 months | Pallor, fever, vomiting, FTT | N/A | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily for a week switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | No walking, SD (no words) | Homozygous c.1106 + 1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 45 | F | 2.5 months | Pallor, poor feeding, petechiae | N/A | CN-Cbl 0.5 mg i.m. daily for a week switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | Walking about 36 months, SD (no words) | Homozygous c.1106 + 1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 46 | F | 2 months | Vomiting | N/A | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. daily for a week switched to CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly | N/A | Walking after 2 years, SD (no words) | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 47 | M | 2 months | Diarrhea, FTT | 2 months | CN-Cbl 1 mg i.m. weekly after an unknown period monthly im 1 mg CN-Cbl continued | 6 years | Normal | Homozygous c.1195C>T (p.R399X) | [19] |

| 48 | M | 2 months | Fever, diarrhea, respiratory distress | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | N/A | N/A | Homozygous c.940+283_286delTGGA; c.940+303_1106 +764del2152insCTGG | [20] |

| 49 | F | 6 months | FTT Diarrhea, vomiting, pancytopenia | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | 2 years | SD | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 50 | M | 7 months | Poor feeding, diarrhea, petechiae | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | 2 years | Delay in walking | Homozygous c.1106+1516_1222 +1231del | |

| 51 | F | 5 months | FTT, poor feeding, vomiting diarrhea | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | N/A | N/A | Homozygous deletion of TCN2 gene in exon 8 | |

| 52 | M | 1 month | Fever, irritability, poor feeding | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | N/A | N/A | Homozygous deletion of TCN2 gene in exon 8 | |

| 53 | M | 2 months | Irritability, oral aphthous ulcers, fever, diarrhea | N/A | CN-Cbl i.m. and oral folic acid (no information about dosage, interval) | N/A | N/A | Homozygous c.106C>T. (Q36X) |

N/A, not available; FTT, failure to thrive; CN-Cbl, cyanocobalamin; OH-Cbl, hydroxyl cobalamin; methyl-Cbl, methylcobalamin; i.m., intramuscular; p.o., per oral; M, male; F, female; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; SD, speech delay.

Another clinical manifestation of TC deficiency is gastrointestinal complications. A cohort study declared that 37.5% of patients have gastrointestinal findings [3] (Table 2). Gastrointestinal manifestations occur because of interruption of proliferation of epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract which causes atrophy of the epithelial cells of the luminal lining [8]. Patients usually complain of vomiting, diarrhea, failure to thrive, and rarely mucositis glossitis [22]. In our cases, vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive were the major clinical manifestations.

In gastrointestinal manifestations accompanied by neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia, clinicians should also evaluate immune deficiencies in the differential diagnosis [21], [22]. Therefore, similar to the cases we reviewed, IVIG administration has been reported in these patients [16]. Low T and B cell accounts were also reported in TC deficiency [3], [12]. The etiopathogenesis of immunological findings in TC deficiency is intracellular cobalamin depletion which causes defective DNA synthesis and leads to arrest at proliferation of lymphoid progenitors [23]. Quality and quantity deterioration of T and B cells lead to low T and B cell accounts and low immunoglobulin levels. All these situations prepare the ground for severe infections. In our cases, although lymphocyte subsets were unremarkable, low immunoglobulin levels were determined. Gastrointestinal symptoms and decreased immunoglobulin levels were resolved with i.m. hydroxy-Cbl treatment.

There is no consensus regarding the dosage, dose intervals, route of administration (i.m., oral), and the form of cobalamin (hydroxy-Cbl, cyano-Cbl) (Table 2). Aggressive treatment, which comprises parenteral or intramuscular high-dose (1 mg) injection (weekly at least), is recommended [3], [5]. Besides, compared with the cyano-Cbl treatment, better clinical results obtained with hydroxy-Cbl treatment. [3]. Furthermore, Nashabat et al. reported successful clinical outcome in two TC deficiency diagnosed patients with 1 mg i.m. weekly methylcobalamin (methyl-Cbl) [18]. Folic acid and betaine administrations were also reported in TC deficiency [6] (Table 2). In our patients, we administrated 1 mg/day, i.m. hydroxy-Cbl therapy for one week. Clinical improvement was observed. In the clinical follow-up, weekly 1 mg i.m. hydroxy-Cbl was adequate for maintaining the laboratory parameters within the normal range. We believe that, for determining the most appropriate treatment approach in TC deficiency, more reports about the clinical progress in patients, and prospective interventional studies are needed.

It is well known that early initiation of treatment is crucial for achieving optimal outcomes [3], [5]. Most studies showed that early treatment has better outcomes [3], [5], [6] (Table 2). Moreover, lifelong treatment is required for the prevention of complications. Neurological and hematological deterioration have been reported in patients who discontinued treatment [3], [5], [20]. In our cases, after one week of intensive treatment, significant improvements were achieved in hematological parameters, and homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels. In the short follow-up period, with weekly i.m. hydroxy-Cbl treatment, neurological examination findings were normal in both patients.

No genotype-phenotype correlation was reported in TC deficiency. Previously, insertions, deletions, splice-site, and nonsense mutations were reported [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20] (Table 2). In our patients, we revealed a novel nonsense premature stop codon variation in exon two of the TCN2 gene. More reports of novel variations may help to evaluate the genotype-phenotype relationship better.

As a consequence, in infants with pancytopenia, growth retardation, gastrointestinal manifestations, and immunodeficiency, the inborn error of cobalamin metabolism should be kept in mind. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for better clinical outcomes. Intramuscular hydroxy-Cbl administration at least once a week is sufficient for normalizing hematological parameters, homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the patient’s parents for their understanding and cooperation in this study.

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from parents of patients included in this study.

References

1. Hunt, A, Harrington, D, Robinson, S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ 2014;349:g5226. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5226.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Hakami, N, Neiman, PE, Canellos, GP, Lazerson, J. Neonatal megaloblastic anemia due to inherited transcobalamin II deficiency in two siblings. N Engl J Med 1971;285:1163–70. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197111182852103.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Trakadis, YJ, Alfares, A, Bodamer, OA, Buyukavci, M, Christodoulou, J, Connor, P, et al. Update on transcobalamin deficiency: clinical presentation, treatment and outcome. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014;37:461–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-013-9664-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Arlet, JB, Varet, B, Besson, C. Favorable long-term outcome of a patient with transcobalamin II deficiency. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:704–5. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Yildirim, ZK, Nexo, E, Rupar, T, Büyükavci, M. Seven patients with transcobalamin deficiency diagnosed between 2010 and 2014: a single-center experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017;39:38–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/mph.0000000000000685.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Schiff, M, Ogier de Baulny, H, Bard, G, Barlogis, V, Hamel, C, Moat, SJ, et al. Should transcobalamin deficiency be treated aggressively?. J Inherit Metab Dis 2010;33:223–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-010-9074-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hitzig, WH, Dohmann, U, Pluss, HJ, Vischer, D. Hereditary transcobalamin II deficiency: clinical findings in a new family. J Pediatr 1974;85:622–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80503-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Bibi, H, Gelman-Kohan, Z, Baumgartner, ER, Rosenblatt, DS. Transcobalamin II deficiency with methylmalonic aciduria in three sisters. J Inherit Metab Dis 1999;22:765–72. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005507204491.10.1023/A:1005507204491Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Namour, F, Helfer, AC, Quadros, EV, Alberto, J-M, Bibi, HM, Orning, L, et al. Transcobalamin deficiency due to activation of an intra exonic cryptic splice site. Br J Haematol 2003;123:915–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04685.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Li, N, Rosenblatt, DS, Kamen, BA, Seetharam, S, Seetharam, B. Identification of two mutant alleles of transcobalamin II in an affected family. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:1835–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/3.10.1835.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Li, N, Rosenblatt, DS, Seetharam, B. Nonsense mutations in human transcobalamin II deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994;204:1111–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1994.2577.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Prasad, C, Rosenblatt, DS, Corley, K, Cairney, AE, Rupar, CA. Transcobalamin (TC) deficiency--potential cause of bone marrow failure in childhood. J Inherit Metab Dis 2008;31:S287–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-008-0864-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Ratschmann, R, Minkov, M, Kis, A, Hung, C, Rupar, T, Mühl, A, et al. Transcobalamin II deficiency at birth. Mol Genet Metabol 2009;98:285–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Nissen, PH, Nordwall, M, Hoffmann-Lücke, E, Sorensen, BS, Nexo, E. Transcobalamin deficiency caused by compound heterozygosity for two novel mutations in the TCN2 gene: a study of two affected siblings, their brother, and their parents. J Inherit Metab Dis 2010;33:S269–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-010-9145-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Häberle, J, Pauli, S, Berning, C, Koch, HG, Linnebank, M. TC II deficiency: avoidance of false-negative molecular genetics by RNA-based investigations. J Hum Genet 2009;54:331–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.34.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Ünal, Ş, Rupar, T, Yetgin, S, Yarali, N, Dursun, A, Gürsel, T, et al. Transcobalamin II deficiency in four cases with novel mutations. Turk J Haematol 2015;32:317–22. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjh.2014.0154.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Chao, MM, Illsinger, S, Yoshimi, A, Das, AM, Kratz, CP. Congenital Transcobalamin II Deficiency: a rare entity with a broad differential. Transcobalamin-Mangel: eine seltene Erkrankung mit einem breiten Differenzialdiagnose Spektrum. Klin Pädiatr 2017;229:355–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-120266.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Nashabat, M, Maegawa, G, Nissen, PH, Nexo, E, Al-Shamrani, H, Al-Owain, M, et al. Long-term outcome of 4 patients with transcobalamin deficiency caused by 2 novel TCN2 mutations. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2017;39:e430–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/mph.0000000000000857.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Khera, S, Pramanik, SK, Patnaik, SK. Transcobalamin deficiency: vitamin B12 deficiency with normal serum B12 levels. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e232319. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-232319.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ünal, S, Karahan, F, Arıkoğlu, T, Akar, A, Kuyucu, S. Different presentations of patients with transcobalamin II deficiency: a single-center experience from Turkey. Turk J Haematol 2019;36:37–42. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjh.galenos.2018.2018.0230.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Briani, C, Dalla Torre, C, Citton, V, Manara, R, Pompanin, S, Binotto, G, et al. Cobalamin deficiency: clinical picture and radiological findings. Nutrients 2013;5:4521–39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5114521.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Herrmann, W, Obeid, R. Cobalamin deficiency. Subcell Biochem 2012;56:301–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2199-9_16.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Tamura, J, Kubota, K, Murakami, H, SawamuraM, MatsushimaT, TamuraT, et al. Immunomodulation by vitamin B12: augmentation of CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cell activity in vitamin B12 deficient patients by methyl-B12 treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 1999;116:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00870.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Engin Kose et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- The influence of growth hormone therapy on the cardiovascular system in Turner syndrome

- Original Articles

- Clinical utility of urinary gonadotrophins in hypergonadotrophic states as Turner syndrome

- Sclerostin and osteoprotegerin: new markers of chronic kidney disease mediated mineral and bone disease in children

- Monthly intravenous alendronate treatment can maintain bone strength in osteogenesis imperfecta patients following cyclical pamidronate treatment

- Mechanisms and early patterns of dyslipidemia in pediatric type 1 and type 2 diabetes

- Frequency of thyroid dysfunction in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease exposed to iodinated contrast media – a long-term observational study

- Effect of growth hormone therapy on thyroid function in isolated growth hormone deficient and short small for gestational age children: a two-year study, including on assessment of the usefulness of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation test

- Clinical relevance of T lymphocyte subsets in pediatric Graves’ disease

- Long-term follow-up of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents

- A quality improvement project for managing hypocalcemia after pediatric total thyroidectomy

- Pubertal development and adult height in patients with congenital hypothyroidism detected by neonatal screening in southern Brazil

- Clinical characteristics, surgical approach, BRAFV600E mutation and sodium iodine symporter expression in pediatric patients with thyroid carcinoma

- BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations in paediatric and young adult papillary thyroid cancer and clinicopathological correlation

- Case Reports

- Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1B (PHP1B), a rare disorder encountered in adolescence

- Impaired glucose homeostasis and a novel HLCS pathogenic variant in holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency: a report of two cases and brief review

- Transcobalamin II deficiency in twins with a novel variant in the TCN2 gene: case report and review of literature

- Aldosterone deficiency with a hormone profile mimicking pseudohypoaldosteronism

- Non-classical lipoid adrenal hyperplasia presenting as hypoglycemic seizures

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- The influence of growth hormone therapy on the cardiovascular system in Turner syndrome

- Original Articles

- Clinical utility of urinary gonadotrophins in hypergonadotrophic states as Turner syndrome

- Sclerostin and osteoprotegerin: new markers of chronic kidney disease mediated mineral and bone disease in children

- Monthly intravenous alendronate treatment can maintain bone strength in osteogenesis imperfecta patients following cyclical pamidronate treatment

- Mechanisms and early patterns of dyslipidemia in pediatric type 1 and type 2 diabetes

- Frequency of thyroid dysfunction in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease exposed to iodinated contrast media – a long-term observational study

- Effect of growth hormone therapy on thyroid function in isolated growth hormone deficient and short small for gestational age children: a two-year study, including on assessment of the usefulness of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation test

- Clinical relevance of T lymphocyte subsets in pediatric Graves’ disease

- Long-term follow-up of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents

- A quality improvement project for managing hypocalcemia after pediatric total thyroidectomy

- Pubertal development and adult height in patients with congenital hypothyroidism detected by neonatal screening in southern Brazil

- Clinical characteristics, surgical approach, BRAFV600E mutation and sodium iodine symporter expression in pediatric patients with thyroid carcinoma

- BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations in paediatric and young adult papillary thyroid cancer and clinicopathological correlation

- Case Reports

- Pseudohypoparathyroidism type 1B (PHP1B), a rare disorder encountered in adolescence

- Impaired glucose homeostasis and a novel HLCS pathogenic variant in holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency: a report of two cases and brief review

- Transcobalamin II deficiency in twins with a novel variant in the TCN2 gene: case report and review of literature

- Aldosterone deficiency with a hormone profile mimicking pseudohypoaldosteronism

- Non-classical lipoid adrenal hyperplasia presenting as hypoglycemic seizures