Abstract

We argue that lived spaces play a crucial role in influencing how people can or cannot enact their agency. Based on an interpretive ethnographic study of work in a large Sri Lankan tea plantation and drawing on the conceptual lenses of relational agency and social ecology, we explore how workers experience their ability to act agentically in relation to their social circumstances and examine the personal and social consequences. In doing so, we extend conceptualizations of relational agency as a dialectic of belonging and not belonging within a social ecology – an ongoing flow of intertwined activities and ways of being and relating to each other that create and reproduce social orders and forms of accountability.

1 Introduction

The ability to enact individual agency is complex, particularly in non-industrialised, non-professionalised societies where there is a nexus of social and work relationships; historical and political traditions; and little separation between work and personal life. Based on an interpretive ethnographic study of Sri Lankan tea plantation workers, where opportunities to enact agency are rare and fraught with difficulty, we argue that attempting to act agentically was experienced in relational ways. Our contribution lies in building on sociological conceptualizations of relational agency as a dialectic of belonging/not belonging within a social ecology – an ongoing flow of intertwined activities and ways of being and relating to each other that create and reproduce social orders and forms of accountability. This reconceptualization challenges mainstream theorizations of agency that assume agentic action is unproblematic and that individuals can act reflexively and strategically to contest and creatively change their circumstances to varying degrees (e.g. Tomlinson et al. 2013), even when marginalised or vulnerable (Creed et al. 2010; de Holan, Willi, and Fernández 2019; Gupta 2004; Raman 2020).

Little empirical work exists in Organization and Management Studies (OMS) in relation to agency in non-Western organizations, contexts and cultures (see Broadfoot, Munshi, and Cruz 2017; de Holan, Willi, and Fernández 2019; Tobias, Mair, and Barbosa-Leiker 2013 for exceptions). Western scholarship relies on western conceptions of agency and non-western institutions are benchmarked and theorised against ethnocentric contexts and ideals (Bothello, Nason, and Schnyder 2019). To counter this ‘conceptual imperialism’ (p. 7), they argue for greater teleological diversity and an appreciation of alternative social orders. We embrace this call by examining how relational agency plays out within the social ecology of a Sri-Lankan tea plantation through a hermeneutic lens, exploring how people account for their agency and actions from within their experience, in “the fluid back and forth flow of living interdependent activity” (Shotter 2008, vi). A hermeneutic focus on agency foregrounds how relationality – a sense of belonging/not belonging and of accountability to each other – impacts our ability to act agentically as we engage in practical activities, intertwined interactions, relationships and ways of communicating in everyday life that seem appropriate or inappropriate to others and to ourselves, i.e. a social order enacted in the social ecology in which we are embedded. We argue that agency is therefore relational in that it occurs in the intertwined activities in which people reproduce or change accepted ways of being, relating, and living their lives.

While the plantation context is not representative of most organizations today, parallels may be drawn with other contemporary forms of work where people live in their workplace: domestic work, au pairs, farm workers, and indigenous populations across the world who live in tourist places. As we discuss later, our study also has implications for migrant communities and migrant workers in contemporary ‘westernised’ organizations. Tea is a key part of the global supply chain and we draw attention to the importance of considering not just economic issues but also social issues, the relationship between “plants, profits and people” (van Hille et al. 2021, 175).

Our primary research question is therefore: how do plantation workers experience agency on a daily basis in their work and family life? Our approach contrasts to many postcolonial and subaltern studies, where agency is conceived of in terms of a generalized political subject, one of subordination and resistance, and where issues such as power, caste, and gender are dealt with in objectivist and structuralist ways, or through the lens of institutional practices. In attempting to address conceptual imperialism and the privileging of theoretical abstractions, and academic representation and categorization, we respond to Chatterjee’s (2012) call for Subaltern Studies to address the embodied activities carried out by people in local circumstances, i.e. to theorise in more human ways (Cunliffe 2022). This is not an objectivist structural critique addressing structural inequalities, caste dynamics, or forms of resistance, but a hermeneutic study that aims to understand the “significance of everyday life in all its richness and complexity” (Kumar 2012, 72), give voice to people by bringing to the fore how they experience and give meaning to their everyday lives, relationships, and to their ability to change their circumstances. Thus, we focus on the social bonds that tie or separate us, in and across time, because as we live our lives and talk about ourselves – this is what occupies us.

We begin with a brief overview of relational agency as a basis for elaborating our theoretical positioning. This is followed by a contextualization of the study, the methodology, and the findings and their implications. Finally, we discuss how a study of relational agency in an alternative social ecology develops theory and has implications for contemporary work issues.

2 Relational Agency

Agency lies at the heart of being human, and of social and institutional relationships, because it is concerned with our ways of being in the world and our freedom to act intentionally. As a fundamental ontological issue, it encompasses a number of questions, including: Who am I? What is my ability to act and how? and Who am I/we in relation to our world? These questions address how we understand and experience the world in which we live and, as such, have epistemological consequences because our assumptions about agency implicitly or explicitly impact the ways in which we study and theorize people and their activities.

Historically, the agency dilemma (Abrams 1982) centres around the dualistic formulation of social/structural determinism versus free choice, i.e. we are a product of the social world and its institutions, processes, norms and systems, learning to perform pre-determined roles (e.g. DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Vandenberghe, Bentein, and Panaccio 2017), or we are sovereign agents, purposeful, atomistic, self-conscious and autonomous responsible for our own actions and shaping our identities and surroundings by reflexively monitoring our actions in relation to our social life (e.g. Descartes 1786/1968; Grove 2014; Mead 1934).

As one aspect of the agency literature, relational agency is a sociological concept that foregrounds a relational ontology, where emphasis is placed on the social embeddedness of people and their relationships with others and their social context. This contrasts to studies of agency that draw upon different ontological and epistemological positionings (Cunliffe 2011), where agentic relationships are construed as between actors and social structures, with the relationship being a recursive, generative, or dominant one (e.g. Abdelnour, Hasselbladh and Kallinikos 2017; Archer 2007; Giddens 1986; Gorringe and Rafanell 2007; de Holan, Willi, and Fernández 2019; Seo and Creed 2002) or between human and material actants (e.g. Barad 1998; Cooren 2018; Latour 2005), a self in relational contexts of culture, institutions, politics, history, etc (e.g. Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Gergen 2009). In their notable article on relational agency, Emirbayer and Mische (1998, 963) argued that in the structure-agency debate many theorists fail to acknowledge the complex, interrelated and “different ways in which the dimensions of agency interpenetrate with diverse forms of structure” and conceptualise agency as a self-engaging in an internal conversation.

In caste-based societies, the agency dilemma is more complex and requires a temporal understanding. Castes have “deep pockets of ideological inheritance” that influence contemporary life in complex ways (Gupta 2004, vii). Studies of caste also indicate that generalizations are difficult because of contextual differences: in some societies the caste system is rigid, restricting economic, education, and social access (Bapuji and Chrispal 2020; Chakravarti 1993; Dumont 1980; Mosse 2018). In others, caste demarcations are more fluid or are actively resisted (Basnet and Ratnakar 2019; Chaudhry 2018; Folmar 2007; Gupta 2004; Prasad 2012; Raman 2020). Subaltern and Dalit studies of caste and agency draw attention to histories of oppression (e.g. Bhabha 1994; Broadfoot, Munshi, and Cruz 2017; Spivak 1988), and to the struggles and forms of resistance enacted by excluded, exploited, and marginalized voices “at the intersection of local culture and structure” (Pal 2016, 423). We suggest that in these contexts, the agency dilemma is writ large in both practical and philosophical terms through the question of how “human agency becomes human bondage because of the very nature of human agency?” (Dawe 1979, 398). This question is important because it refocuses the issue from whether structure or agents are more influential – and from academic representations of power – to how we, as human beings, create, enact, and (re)produce forms of oppression individually and collectively in our lived experience. This is the issue we address.

We are interested in the everyday, ordinary and ongoing lives of plantation workers and how they experience and struggle with work and personal relationships. From our hermeneutic-phenomenologically inspired relational perspective, which acknowledges that we are intersubjective human beings in the world, agency is about relationships between people, not objects, and how we enact (intentionally or unintentionally) our ways of being with others in a relational context (Burkitt 2016). We suggest that relational agency involves the quotidian details of everyday life: who we can or cannot talk to, eat with, marry, get familial support from, and socialize with.

Thus, in contrast to institutional, subaltern and relational studies of agency that address structural constraints, institutional practices, identity politics, and processes of domination and resistance from a position of generalized theoretical constructs, our focus lies on how people together make meaning/sense, develop understanding/knowledge, and reproduce or change their circumstances within those social circumstances as they talk and interact. From this perspective, it therefore makes more sense to speak of a social ecology rather than ‘structures’ because structures are not just physical, they are created, sustained and become seemingly real in people’s interactions and relationships (Shotter 2008, 2015).

3 Social Ecology as a Backcloth for Relational Agency: A Hermeneutic Perspective

In his concern to illuminate the details of our everyday lives and foreground what happens in our relationships with each other, Shotter (2008) draws attention to what he called an ongoing social ecology – intertwined activities and ways of relating and communicating that are simultaneously invisible and visible to us. Invisible in the sense that we do not notice “our own ways of being ordinary” (p. 37) because we are immersed in them as we speak and act in taken-for-granted ways, and visible in the sense that there are experiences that we can articulate, discuss and account for. Both are agentic in the sense that they manifest themselves in our ways of being ‘ordinary’ and of relating with each other in our encounters and events. And in these ways of relating, we create and maintain social order (e.g. institutions, routine behaviours), ways of being, and forms of accountability that become accepted but may also be open to change. In these ways of relating, human agency may become human bondage (Dawe 1979) because they are often unquestioned. Because we are interested in how people experience everyday work and social life, our study embraces the onto-epistemological commitments of hermeneutic-phenomenology and relational agency, along with Shotter’s (2008) notion of social ecology – a practical hermeneutics concerned with the unfolding of social relationships and activities in everyday plantation life.

Social ecology foregrounds the practical circumstances of people’s lives together within a shared context, in which people are accountable to each other in terms of acting and communicating in acceptable ways that (re)produce social order. They are also embedded in inherited narratives around how to act, be, and relate with each other, which are (in)visible. We argue that it is in the relationships and interactions between people that agency is enacted and/or resisted. Because people live and work on the tea plantation, social ecology is a particularly relevant lens from which to view agency because work and personal life, history, tradition, religion, and culture are embedded in everyday contemporary life.

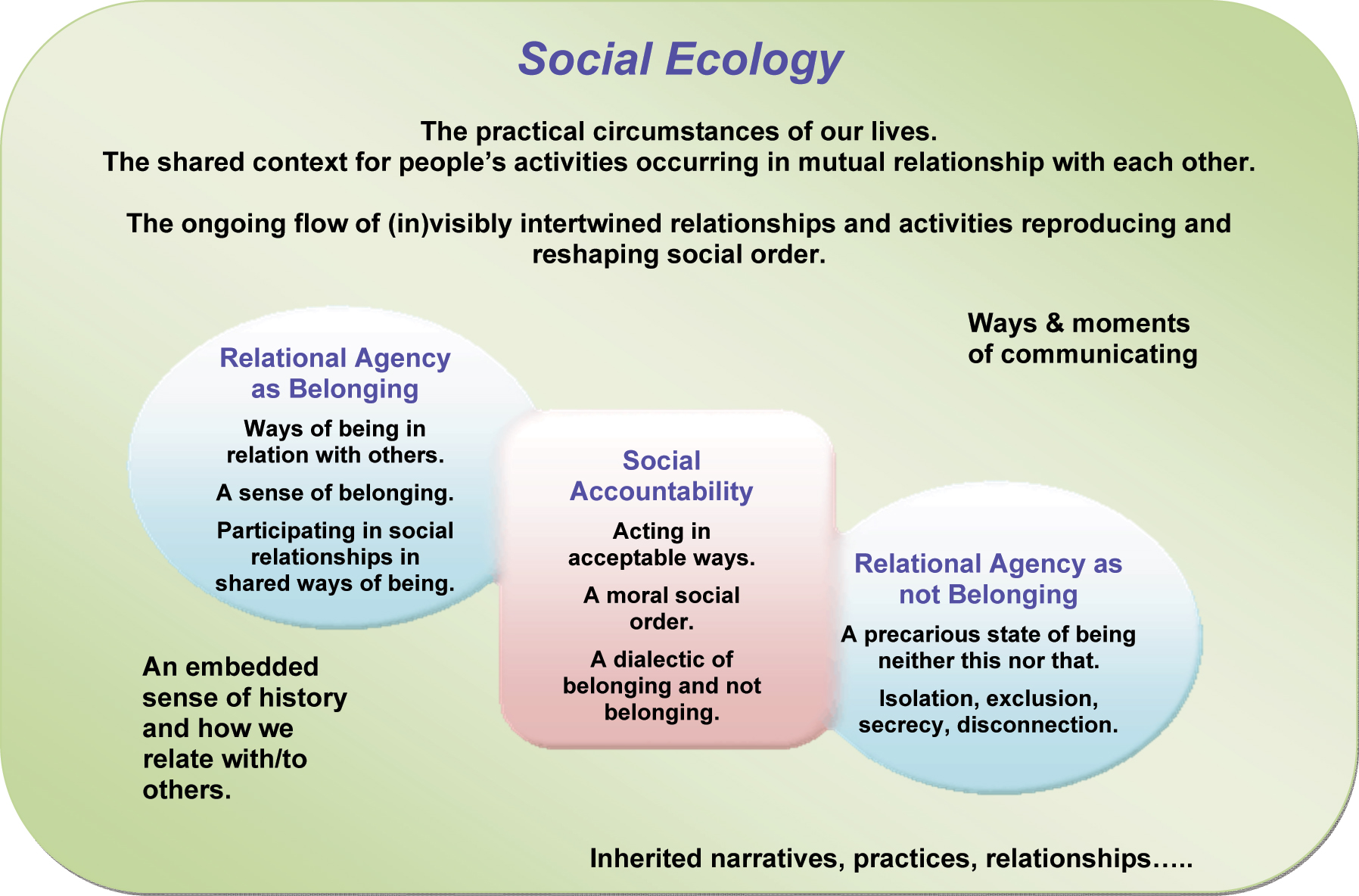

We visualize relational agency within social ecology in Figure 1, which we developed as we sought to find ways of explaining how workers spoke of their experience while remaining as close as possible to that experienc e.

The Social Ecology of Plantation Life.

As we propose and illustrate in Figure 1, relational agency encompasses everyday shared ways of being and acting in relation with others, where one has both an invisible (taken-for-granted implicit ordinary ways of being) and visible (able to be articulated and accounted for) understanding of what it means to be a person within a social ecology – a lived space. In this way, a moral social order is enacted through people’s sense of place, history, and how they should/could relate to each other. As we will show, this was evident in the interactions and accounts of plantation workers around work/family caste issues. A sense of belonging/not belonging is implicated in how we experience and enact our agency within a social ecology because it involves a consideration of relationality, agency and community: a social, historical and physical connection (Miller 2006) with others and our surroundings. In other words, it is “fundamental to who and what we are” (Miller 2003, 217). Relational agency as belonging encompasses the right to participate in social relationships and activities, to have a sense of place and community, and to be able to account for one’s actions in ways acceptable to others. But, as we will argue later, dialectically embedded in a sense of belonging is also a sense of not belonging.

In the following sections we give a brief history of tea plantations as a background to the study, explain the methodology, and then present and interpret the data through the lens we present in Figure 1.

4 The Social Ecology of Tea Plantations in Sri Lanka

Human beings seem to accumulate within themselves, not just a history, but a sense of their ‘position’ in their world in relation to all the others with whom they share it.

(Shotter 2015, 209)

As a backcloth for examining how relational agency plays out within the social ecology of contemporary plantation life, we now offer a brief genealogy of tea plantations for, as Shotter (above) and Emirbayer and Mische (1998) state, we accumulate a sense of history that is implicated in our activities, i.e. temporality and relationality are important. In Sri Lanka, historically-formed religious, colonial socio-cultural, economic and political ideologies operated side by side influencing the formation and differentiation of class, caste, religion and ethnicity in general and also within plantations that still play through life today (see Jayawardena 2001; Wesumperuma 1986).

The majority of Sri Lankan population are Sinhalese, with a minority ethnic composition of Tamils, Moors, Burgher, and others. The Tamils consist of two distinct groups namely Sri Lankan Tamils who migrated to Sri Lanka from India, and the Plantation Tamils/Indian Tamils a distinct group from South India who were brought specifically to work in the plantations as cheap labour by the British during the colonial period (1796–1948). This study focuses on Plantation Tamils, who still live and work in the plantations, which are largely situated in upcountry in Sri Lanka. Tea plantations require year-round plucking, and political and social disadvantages in South India pushed low caste South Indian Tamils to migrate en masse to Sri Lanka in search of better lives (Tinker 1974). As Stenson (1980, 17) notes:

Recruited largely from the untouchable (or adi-dravida) castes of South Indian society, the Tamil and Telugu labourers were probably the most obedient, indeed, servile labourers then available in the colonial world.

British planters employed ‘Kangany’, elite from the South Indian higher sub castes, to build a community infrastructure and to manage the labour supply. This shaped a distinct hierarchical community in the tea plantations. The Head Kangany received interest free loans from the planters and advanced loans to workers desperate to settle their dues in India and cover their passage expenses.

Each worker was issued a Tin Ticket (Thundu system), a permit to travel that was kept by the Kangany. Under the Thundu system, the Kangany recorded a labourer’s indebtedness and no planter employed a labourer without the Thundu from the previous employer (Elliott and Whitehead 1926). Kangany therefore became key figures: planters paid them ‘head money’ for each worker; only Kanganies were allowed to acquire and cultivate land; and all daily rations for workers were supplied through the Kangany-run estate shop (Alawattage and Wickramasinghe 2009). At the research site, a low caste retired worker recalled:

Those days the Kanganies were like police. They used to hit workers. Workers had to do what they said. They said not to send our fathers to school but to keep them like fools with no education. They thought that if workers got educated, they would also become equal to Kanganies. They did not allow the workers to tie their heads with the Talappawa,[1] thinking that workers also would look like Periya Kangany.[2] Periya Kanganies only wore Wëttiya[3] and the Coat and were like Kings. That was how the Kanganies were.

Thus, the Kangany were like ‘police’ and ‘Kings’, controlling class, caste, and status differentiation in plantation organization. This practice was reinforced when the Dutch (who governed the country from 1656 to 1797) passed a law:

All persons of the lower caste shall show to all persons of the higher caste such marks of respect as they are by ancient customs entitled to receive… (Quoted in Pfaffenberger 1982, 90)

Caste differences therefore became manifest in plantation management hierarchy, in the appropriation of resources, and work allocation – differences that prevail today. Management is still largely in the hands of Sinhalese, first level supervision by Kangany (high caste), and work done by Tamils. Over the years, the intervention of government and trade unions has led to changes, but plantation communities, where the workers live in line houses and are dependent on estate management for social welfare (Ramasamy 2018).

This brief history indicates how caste is (in)visibly embedded in the contemporary social ecology of the plantation, implicated in the ways in which plantation workers experience their relationships, customs, and their ability to act within and across caste and religious traditions.

5 Methodology

The paper is based on a larger study exploring how tea plantation workers experience identities in their everyday activities. The tea plantation, situated in the Nuwara Eliya district in Sri Lanka, is split into five divisions, one of which was selected for the study. The selected division has a resident population of 847 (ethnic composition was 835 Tamil, 12 Sinhala) and employs 112 women and 138 men. We take a hermeneutic perspective, which focuses on understanding “the ‘experience’ of ‘experiencing”’ (Szakolczai 2009, 148) how people live and account for their lives. Geetha therefore conducted an ethnographic study, living and working in the tea plantation for three months, observing and participating in the daily lives of the workers, interacting with them, listening to what was said, and asking questions as a means of gathering rich thick descriptions (Geertz 1973). Ethnography can illuminate the complexities of social life, the meanings people give to their lived experience, as well as sensitise researchers to cultural nuances (Atkinson 2015; Cunliffe and Karunanyake 2013).

Within the larger study, data collection methods included participant observation, interviews (recorded and transcribed), informal conversations and analysis of document such as published material, archive information, and policy documents. This formed the basis of question in formal interviews, which were based on purposive sampling in order to obtain different perspectives. Interviews were carried out with 38 workers (male and female high and low caste Tamils), the Senior Plantation Manager (Superintendent), Deputy Manager, Assistant Manager (all Sinhalese), supervisors (all high caste Tamils), the plantation’s midwife (Sinhalese), apothecary, religious leader, school principal, two teachers (all high caste Tamils), and the Secretary to the Plantation Ministry (Sinhalese), (see Appendix 1). All interviews were recorded, except those with the Secretary, Senior Manager and Apothecary who asked not to do so. Interviews varied from 20 min to 2 h.

Because the methodology was ethnographic, opportunistic and less formal (unrecorded) conversations arose. They offered views on their day-to-day experience as Geetha worked in the field with them, spoke with them in the plantation shop, was invited into their homes, and observed ceremonies. In these conversations, workers talked about what they do at work and home, including: daily life experiences; childhood experiences; with whom they associated; domestic activities; social, cultural, political, and religious values, beliefs and practices; how they felt about work and plantation life; the role of trade unions; worker-management interactions, etc. Some of the informal conversations occurred in workers’ homes, where Geetha observed living standards (often 6/7 members of two families live under one roof), how limited space was utilised (family members sleeping on the floor, firewood used for night heating stored in the loft), and displays of photographs of deceased parents, family members, and gods. Living on the plantation she also experienced various aspects of plantation life:

I rented one floor of the building with electricity and hot water facility. Lack of transport, no access to internet, no TV but a radio, only one shop to buy everything and having to stay with an elderly couple used to their own way of living made my life somewhat difficult. (Fieldnotes)

As a participant observer, she took fieldnotes of work practices and interactions and experienced the hardships female workers undergo in climbing the hilly mountains on a cold rainy day. She also took photographs of ceremonies, work practices, the physical surroundings of private and public spaces, and other activities.

Geetha was born, grew up, and received her pre-Ph.D. education in Sri Lanka. She speaks Sinhalese and is therefore attuned to cultural norms and practices, history, religion and traditions. She obtained ethical approval from the University, but had to be sensitive to ethical considerations in the field. Many workers cannot read or write and therefore Geetha assured confidentiality and anonymity and obtained verbal consent. Given the site and nature of the ethnography, personal sensitive issues arose in formal interviews and informal conversations. She therefore carefully considered the politically sensitive nature of relationships between plantation management, workers, trade unions and caste and gave assurances that she would maintain confidentiality and anonymity. Participants could refrain from answering questions if they wished. Although she had never worked in a plantation, her gender and some similarities between Sinhala and Tamil cultures helped to embed her in the field and gave her a lens through which to interpret and understand the data. Her position as both insider and outsider and as same and different (reference to be inserted later) helped her connect with the workers and over time she was invited into workers homes and they confided in her, one stating, “Had you been a person from here, I would not have said these things to you” (fieldnotes).

Consistent with our hermeneutic approach, data were analysed thematically, which enabled thick rich descriptions to be generated. Geetha worked first within and then across transcripts to identify individual and social meanings. An initial list of themes in relation to self and social identities formed the basis for a second stage inductive identification of sub-themes using both a content and latent thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). Sub-themes related to common ways of talking about social and self-identities and activities and were identified across the transcripts. This provided a means of identifying and defining broader themes in relation to the larger study’s primary research question of how tea plantation workers encounter situations in their day-to-day interactions that contribute to producing, reproducing and modifying their identities. Examples of these themes include: caste enactment within public spaces, conformity and resistance in work and personal life, and gender-related issues. Both similarities and differences were noted and checked across the transcripts using a comparative table.

For the purpose of this paper, we are focussing on one theme from the larger research project and on data gathered in the formal interviews, informal conversations arising as Geetha was hanging around in the shop, plucking tea in the field, and visiting homes, taking fieldnotes and photographs. The theme – how agency is enacted within work and social life – emerged because participant comments led us to question the nature of agency. These comments suggested to us that when plantation workers attempted to change their personal or work situation the outcome was unpredictable and often devastating in terms of family and work life relationships. This highlighted the need to examine how people experience their ability to act in relation to others in their social ecology, i.e. relational agency. Consistent with our hermeneutic-phenomenological underpinnings, our aim is to offer a more human way of theorizing that is embedded in human experience and explores “what it means to be human […] from within our ongoing living experience” (Cunliffe 2022, 13): an interpretive strategy for rethinking agency – one that may resonate in other contexts. We visualize our account in Figure 1.

6 Relational Agency in the Social Ecology of Plantation Life

We now begin to explore our research question: how do plantation workers experience agency on a daily basis in their work and family life? We will show in the empirical data how workers reproduce their social circumstances and a social order intelligibly in their everyday actions, by ‘acting accountably’ in terms of conforming to accepted ways of being and relating (Shotter 2015). We suggest that agency occurs relationally when two or more people interact, and is evident in rituals, ceremonies (public and private), work practices, personal and work relationships. We begin by offering experiences from low and high caste workers and illustrate how the six historical/cultural traits of caste (Hollup 1994) – endogamy (marrying within one’s caste), pollution and purity, occupational specialization, hierarchical ranking, commensality, and hereditary membership-play through life as a ‘moral’ and social ecology reproduced in everyday relationships around work and personal life.

Within the social ecology of the plantation, caste differences are temporally embedded and influence how workers relate with each other daily. The Bhagavadgita (which clarifies the religious philosophy of Hinduism) speaks of the evils of caste intermingling:

We know what fate falls on families broken:

The rights are forgotten, voice rots the remnant,

Defiling the woman, and from this corruption,

Came mixing of caste, the curse of confusion

Degrades the victims, and damns the destroyers (in Thiruchandran 1997, 18)

The book of Hindu law, Manusmriti, also addresses the cardinal issue of purity and impurity, which is central to the caste system in Tamil society in a number of ways. A high caste female has to behave with ‘proper conduct’ as she can be polluted easily by touching, eating offered food, or having sexual relationships with lower caste people (Kurian 1998). Among Plantation Tamils, Aghamudiyan, Kudian, and Vellalan/Vellalar are generally accepted as good ‘pure’ castes, while Paraiyar, Pallar, and Chakkiliyan are low castes with whom interaction should be avoided (Baak 1999). High castes maintain their purity and physical cleanliness through daily baths. These self-reproducing activities and ways of being are sustained relationally in everyday life and embedded in caste relationships as a form of social accountability.

6.1 Relational Agency as Belonging

Belonging/not belonging has been a long-term interest of sociologists and has been studied from various perspectives including belonging as an emotional attachment to and/or a fear of exclusion from collectivities and places (see Guibernau 2013 for one overview). A sense of belonging/not belonging played through plantation workers lives in many ways. They spoke frequently about hierarchical differences in work and personal relationships that are based on caste and temporally embedded. In the plantation, social ceremonies and rituals (weddings, funerals, a girl’s attaining puberty, house warming) are celebrated with great enthusiasm and devotion and influence ordinary agentic ways of being in (in)visible symbolic and relational ways. Belonging/not belonging is maintained symbolically and relationally as high caste employees stand at the front in plantation work meetings, in ceremonies can touch and lift the carriage of the god’s statues, enter religious places, and parade in the front line (Figure 2).

Not/Belonging to One’s Caste.

Low caste employees stand at the back of meetings, and in ceremonies beat the drums and walk behind the parade. They also stay outside religious places:

There are a lot of issues and we do not go to Kovil normally as they do not allow us to offer Pujawa (Low caste female worker).

A high caste male worker explained how caste differences affect work life in (in)visible ways:

Can a person who sweeps the road in NuweraElliya work in a bank or in an office? It is not possible. He sweeps, he drinks and shouts on the road. Does a gentleman in the bank do the same? That is the difference between the two castes… That cannot be changed. It is coming from generations…

This illustrates how agency is temporally embedded in expectations and inherited narratives about accepted ways of acting and being that are situated in and across time. Implicated in these ways of relating is a sense of social order – how things should or shouldn’t be done – that in many cases is accepted and remains unquestioned. As May (2011, 370) observes, “one of the ways in which a sense of belonging can emerge is if we can go about our everyday lives without having to pay much attention to how we do it”. As one low caste female worker noted:

If there is a festival, a wedding or a girl attaining puberty, everybody goes. However, the high caste people do not eat at lower caste people’s houses. If there is an occasion at high caste peoples’ houses, then the lower caste people should stay outside and eat.

Managers (Sinhalese) are invited to attend employee ceremonies but are never offered any meals to consume, nor invited inside employees’ houses. We suggest this social order is characterised by a sense of belonging as workers interact and relate only with their caste.

From a relational perspective, belonging occurs when one participates in conversations and interactions and is taken seriously, i.e. where one feels “one has a right, unconditionally, to ‘belong”’ (Shotter 2008, 70). Embedded in this sense of belonging is our ability and willingness to account for our actions, relationships and for events in ways that are acceptable to ourselves and others. This is evident in the daily work of plucking the leaves, which involves both high and low caste female workers, yet each worker relates only to others within her caste:

The managers appoint us to the field. We work with everybody. But we mind our business and they [high caste workers] mind theirs. We do not go to them. We should not. We work very hard. We do not need their help. (Low caste female worker).

Implicit in this comment is a sense of belonging, of relating to one’s caste, while also maintaining difference (not belonging) by not interacting with others. In this way, social order in the social ecology of plantation life is enacted as people act in ways that are acceptable and accountable to others. As we note in Figure 1, these ways of being are rooted in inherited narratives and an embedded sense of history.

A way of being in-relation-to-others is therefore temporally and hierarchically embedded, not just in these daily interactions but also in the visible practice of assigning people work positions based on caste. Senior field supervisors, Kangany (ground level supervision who are historically ‘Kings’, p. 9) and trade union representatives (grass-root representatives of political parties) are high caste positions, and:

Low caste people promoted as Kangany won’t work. Nobody will listen to him or obey his rules…Nobody will like to work under a field supervisor from a low caste. […] If I employ a low caste person as my personal ‘appu’ (cook), it will have a big impact on me. I will get some sort of pressure from the workers. (Deputy Manager).

Transgressions can lead to problematic relationships because hereditary occupational specialization and hierarchical ranking (superior/inferior castes), two of the historical/cultural traits of caste (Hollup 1994), are still embedded in a social order maintained in relationships around work practices and social interactions. However, this social order does not always coincide with organizational hierarchy because caste differences and longevity intervene:

Managers cannot appoint [low caste] workers as field officers. Managers have to listen to us. We are the people who live here, managers come and go. So, they cannot do what they want. (Kangany)

Kanganies (always high caste and living on the plantation) therefore enact agency in the workplace by influencing the daily relationships of both managers and workers through job allocation. Trade Union representatives are also able to exercise their agency by influencing politicians, whereas managers cannot, and therefore the agency of Kangany and TU representatives transgresses organizational hierarchy.

Social differences and opportunities for agentic action, i.e. to do something differently, are therefore embedded in the social ecology of daily interactions: intertwined relationships around religious ceremonies and work that give one a sense of belonging – of ontological security. Food habits at home and work are also based on caste distinctions. High caste employees are vegetarians and teetotal, but there are no such restrictions for lower caste employees who consume beef,[4] drink alcohol and are considered as ‘polluted’ people:

People from different castes eat different food. I do not know how it came to exist. It is coming from generations. The one’s who lift God eat only vegetables. (High caste male worker).

Our religion has three categories of people. We are the best category out of the three. We are ‘Kudianakkal’…The bad people are ‘Sakkili’…and ‘Parayi. They drink ‘arrack’ [alcohol] and eat beef. They are not good people. If you eat beef, you commit a sin. (High caste female worker).

Social order – and differences – are therefore maintained in the ‘practical circumstances of peoples’ lives – especially when living in close proximity in line houses:

You do not understand how difficult it is to live here. My mother told me not to talk to others. They want to know what we eat, what we do, and all. That is the way here when living in line. I wish we have houses not in line but in another place (Low caste female worker).

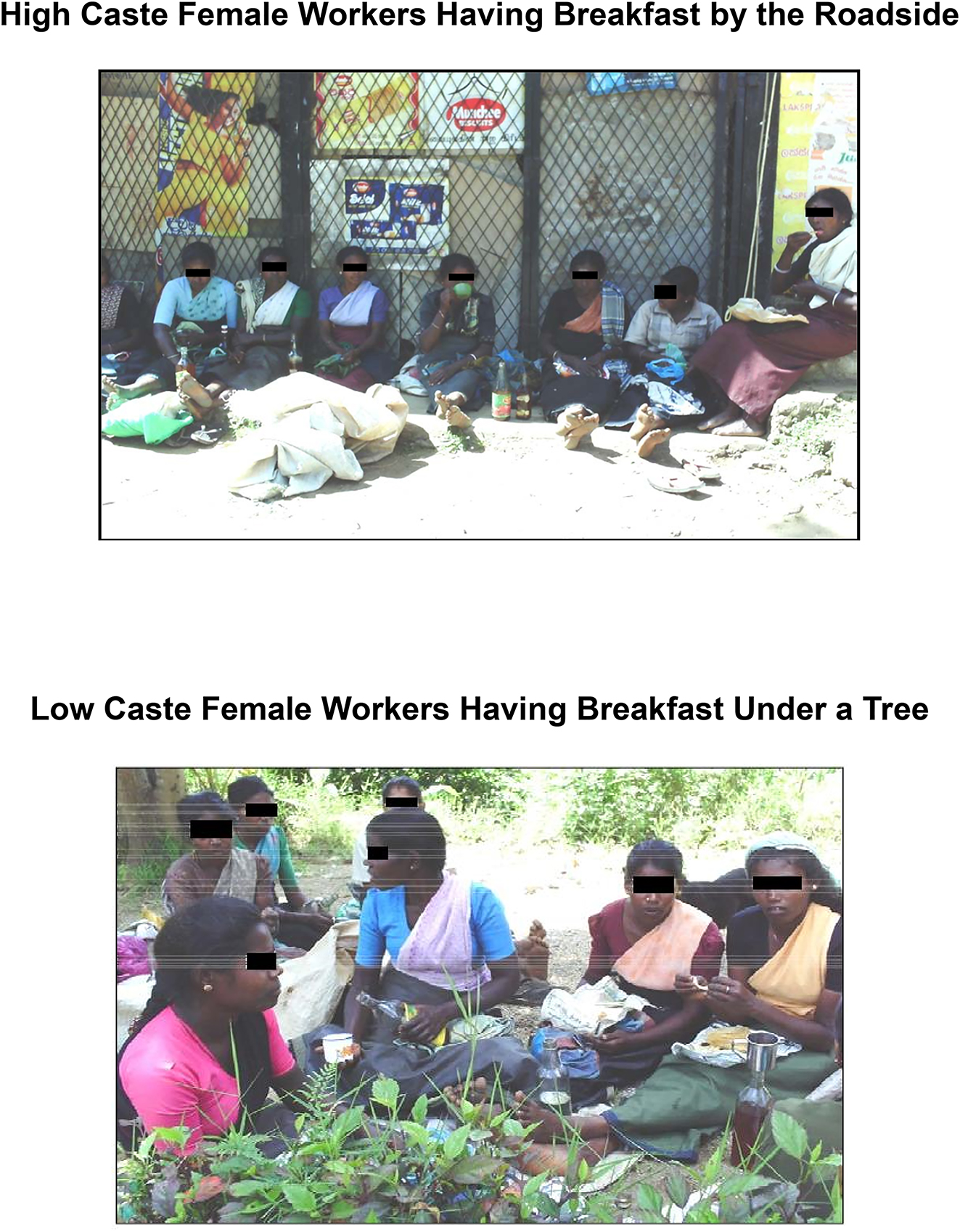

Although low castes can receive food from high castes, the opposite is not acceptable because the food is deemed to be polluted. Additionally, each castes prepares, serves and consumes food in a particular way, which reinforces a sense of belonging to a particular group. Appadurai (1981) argued food can either homogenize or heterogenize people. We suggest it does both simultaneously, for while common food habits create connection (belonging), they also create a sense of social difference (not belonging), which are observable in interactions around lunchtime workspaces:

The good people [high caste] and those who are low caste do not sit together and eat in the field…There are groups who sit together and eat every day… some low caste people go to a corner and eat on their own. They do not share food. (Deputy Manager).

We associate with our own people. […] We do not like to associate with others when having meals as they are different from us and they eat all sorts of things, but we do not. (High caste female worker).

High caste female workers maintain their social differentiation relationally by sitting along the roadside and sharing food (see Figure 3). In this example, space is symbolically significant because the roadside is visible to anyone passing-by, whereas low caste workers sit in a remote location, hidden by a hedge and invisible to others.

Not/Belonging in Space.

The photographs and interview excerpts above and below illustrate clearly ways in which social order is maintained through demarcated relationships of belonging/not belonging, of inclusion and exclusion. Agency, in terms of ordinary ways of being, is experienced in mundane daily work and family activities and relationships which (in)visibly reproduce a social order created over time, with forms of accountability that influence shared ways of being-in-the-world (Shotter 2015). As such, these shared and unquestioned understandings are temporally embedded inherited narratives that helps give meaning to what it means to be a person in this social ecology – in taken-for-granted ordinary (in)visible ways of being and relating with others. While the plantation’s social ecology of daily activities, relationships, rituals, ceremonies, and habits make it difficult for individuals to resist because they form a background in which present activities, ways of talking, and social relationships are rooted, as we will see in the next section, some people do try to engage in collective and individual acts of agency.

To summarise, we argue that relational agency is experienced as ordinary ways of being and belonging in the plantation’s social ecology, plantation workers reproduce a social order in their everyday entwined relationships through their sense of what is socially appropriate. In other words, both high and low caste workers situate and account for themselves as belonging within their caste (the accepted social order). But, we argue, implicated in relational ways of belonging are ways of not belonging to the other, and this is what we now address.

6.2 Relational Agency as Not Belonging

We now explore what happens when people act agentically to try to change their circumstances – to challenge or step out of the existing social order. Agency is not just about ways of being, but also whether we have freedom to act and change our circumstances, i.e. it involves a degree of intentionality to change the existing social order, inherited narratives, practices, and/or relationships. Plantation workers have few options to agentically disrupt a social order enacted in their everyday communal ways of relating. Those trying to cross inherited caste relationships and activities often found themselves held captive to a state where they were “always-this-and-never-that” (Bamber, Allen-Collinson, and McCormack 2017, 1514). This is exemplified in the following excerpt where personal acts of agency occur that challenge caste boundaries:

We do not cook meat often but when my husband goes away from the plantation, he brings cooked meat. Others keep an eye on what we cook and eat. Do you know how the people here are? They too eat meat but they spy on others (High caste female worker).

Tensions between the accepted social order and personal actions result in secrecy and spying as a way of maintaining distinctions between belonging and not belonging.

Consequences for those trying to change their circumstances in more overt ways within the existing social ecology of plantation life can result in a state of not belonging – being neither this not that – with no foreseeable opportunity for change. For example, marriage with a person from a different caste brings shame and disgrace to the whole family as it is considered as being ‘polluted’: endogamy is a way of preserving caste differences (Chowdhry 2004). Geetha observed how marriage is ‘sacred’ and preserved through a strict code of conduct as a means of protecting the caste hierarchy (Kurian 1998). Inter-caste marriages do take place, albeit with the objection of the elders, but social and work relationships are affected resulting in both high and low caste employees experiencing a precarious state of exclusion and not-belonging, being neither one caste nor the other, sometimes hiding what they do and who they are.

One high caste worker, who returned to the plantation after working at a Doctor’s house in Colombo, married a low caste woman and talked of being ‘an orphan’:

I came to the estate thinking that I could live the way I want… I had to face many problems when I got friendly with [my wife] because of her caste. My relations are from a good caste… They scolded my mother, telling her not to allow my marriage […] Before going to the Kovil to get married I wanted to go and pay my respect to my mother… She wanted to come to the wedding but she was afraid that others would scold her. Therefore, she did not come. I held my mother and cried. I said, ‘I have four brothers, but I am going to get married like an orphan child without anybody’. (High caste male worker)

In Tamil society, marrying a lower caste person is viewed as mixing with impure blood, hence the mother’s fear and decision not to attend her son’s marriage. He underwent isolation and humiliation for some time after his marriage – a consequence of acting in an unacceptable way to both high and low caste relatives. However, relationships did improve very slowly as he obtained a job in the plantation Dispensary and supported his parents. A low caste worker also talked about problems when he married a high caste woman:

Nobody gave permission for our marriage. My parents did not like it as we are from a lower caste and my father said that we cannot associate with them in any way. Their family too did not agree as they are from a high caste and thought that their daughter will become a lower caste by marrying me. I faced a lot of problems. (Low caste male worker)

In Tamil society, marrying a low caste male meant the high caste female’s family would face issues in terms of being isolated from others and not being able to exchange food as their daughter had become polluted and low caste, resulting in conflicts amongst two families. These are examples of the relational nature of agency – of how caste differences are deeply embedded in everyday life, reflected in whether one is deemed to belong or not belong.

A similar experience was shared by a low caste female worker, who came to the plantation after marrying a high caste male. She was unusual in the plantation, being one of a few women educated up to Ordinary Level. She recalled how starting a ‘new life’ meant being afraid to be alone and being careful about relationships:

When I married and came to this plantation my husband told me to keep my caste a secret as he is from a high caste. I started a new life here but it was not easy […] When I first moved here, I did not move with others. I was afraid when my husband went abroad. […] he spoke to the manager and got me a job in the Crèche [normally a high caste position]. Now I teach small children. I have been living here for nearly 12 years and I am alright now, but I try to avoid deep conversations with others. (Low caste female worker)

These examples illustrate that endogamy is still embedded in plantation life and that inter-caste marriages seem to be an ongoing emotional and practical sense of not belonging: experienced as a social void, a space where, as a consequence of trying to change one’s circumstances one becomes an orphan, doesn’t get into deep conversation, or is spied upon.

Challenging relationships within the moral social order can therefore be devastating, resulting in workers committing suicide, being distanced by family members, eloping, or moving away as they find themselves neither belonging to their own nor a different caste. One incident involved a mother and daughter committing suicide by jumping from a waterfall because the daughter was pregnant after a relationship with a low caste boy (fieldnotes). Attempts by plantation workers to agentically change themselves and their circumstances – exercising their agency – affects their very way of being and relating with others, bringing tension to the lives of individuals and the community because they are embedded in a social ecology of explicit and implicit ways of being.

We argue that from a hermeneutic perspective this is not about challenging or resisting intractable structures and systems, rather it is about how we relate with and are accountable to others in the social ecology of our intertwined activities. In the plantation’s social ecology, agency cannot be exercised to create new ways of being or relating because a person’s freedom and ability to change their circumstances is embedded in an (in)visible social order (re)produced in everyday relationships and activities of workers and their families in which history and a sense of their position and belonging or not belonging is implicate. Attempts to enact agency as we have shown, can alter “the very core of one’s being” (Szakolczai 2009, 148) in devastating ways. Belonging is a human (Bryer 2019), emotional and relational experience – in contrast, not belonging is a precarious state where one’s relationships are limited, one hides one’s true self, and there is little potential to strategically change one’s circumstances

7 Acting Agentically: A Changing Social Ecology?

Despite the seemingly intractable social ecology we note above, workers do try to change their work and personal circumstances and challenge the existing social order. Such changes occur slowly in personal and sometimes collective ways. One example related to generational differences. Younger people, especially those who had worked outside the plantation, challenged inherited caste-related narratives and relationships because their experience led them to question the (in)visible social orders in the plantation and rethink the possibilities of their work and personal life:

In those days, customs were practised as they were…but nowadays our children do not listen to us. They always question what we do here saying that they do not make sense. (High caste female worker).

There is also a degree of emerging collective agency apparent as lower caste workers challenge the symbolic and relational differences embedded in religious ceremonies. Geetha found examples of tension when plantation management had to call for police:

We say that we do not mind others coming and touching the God as we are all human […] but when we say this, others also from high caste do not like, they come and fight with us. There are a lot of fights during this time and some people get arrested… Low caste people question high caste and they say that high caste do not deserve privileges as they drink arrack (alcohol) (High caste male worker).

In this enactment of agency, public and private tensions arose as lower caste workers question the privileges of high caste workers.

Tensions around the temporal embeddedness of agency are seen in the comment below, where the older generation maintain caste differences – which can be framed as inherited power relationships – by relating only with their own caste. But the younger generation are challenging this:

Here there are four major castes and they are dominating. We cannot do anything with them. Older people let us down as we are not in the good caste. They do not take bad caste people to their houses. We have to stay outside. They used to give us coconut shells to drink water. But now things have changed somewhat. We go to their houses and drink, they come to our houses and drink. Only the older people still have these ideas. (Low caste female worker)

Differences between castes are therefore being eroded slowly in the everyday relational activities of workers.

There were also examples of generational differences when past and present collide and small changes seemingly occur as plantation managers juggle social tensions with organizational requirements. Cleaning toilets and gullies and sweeping line corridors are necessary to maintaining common employee facilities and managers assign these tasks based on kinship:

They call the line sweepers Wasakutti, who clean the toilet. When we assign the work, the youths do not like it. From the beginning, from their caste they were called Wasakutti…their fathers too, they are also toilet cleaners. Now we give them some respect and call them line sweepers, when actually, their work is to clean the toilets and bungalows and keep them clean. (Deputy Manager)

Line sweeping is a low caste task assigned to relatives or the sons of retiring employees, who recognise that this limits their prospects for a good job. They have no option but to accept the practices of their elders unless they find employment elsewhere, which has risks. However, in order to maintain the existing social order while avoiding resistance from the youths, managers reconfigured the job title to one with fewer connotations and paid them a daily wage, although essentially the job remained the same, their original caste relationships and status at work did not change. This is one example of how managers make subtle and artful symbolic adjustments in response to resistance: the youths were satisfied, the job was still done, and the accepted social order maintained. These adjustments reflect that one may always be “this-and-never-that” (Bamber, Allen-Collinson, and McCormack 2017), an observation reinforced by the Deputy Manager who stated that he is always mindful of the status and influence of high caste workers which ‘comes from the beginning’.

In contrast, one example of a major change based on organizational expediency occurred when one low caste youth with a good education who could speak English fluently (which most high caste workers could not) was placed in charge of the plantation teashop (often crowded with tourists) and paid more than the rest of the workers. However, tensions may arise as high and low caste field workers clash amongst themselves and with first-line supervisors, and relationships are disrupted:

The Kangany should supervise everybody equally. Sometimes the Kangany favours his people, he doesn’t let others say anything to high caste people. Therefore, we scold them. This leads to fights. Sometimes he supports us when he is upset with his own people. We tell him to supervise everybody’s work equally without favouring his own people (Low caste female worker).

Workers take advantage of situational opportunities to try to change relationships and activities. In response, the Kangany might allow the low caste workers to go home early that day, but nothing changes and arguments continue.

Agentic action in terms of changing (in)visible social relationships was also evident in home life. One such example relates to Kotahalu unahama, when a girl attains puberty. At this time, she is kept home for 3 months as she is considered unclean – a convention now being questioned by some. One mother commented on the difficulties her eldest daughter faced:

When she attained puberty, she did not go to school for three months. She was not promoted to the next grade as she could not attend the class for three months. Then she had to repeat year 9. Other children laughed and made fun of her for repeating the same grade. Then she refused to go to school. (High caste female worker).

In response to the practicalities and the relational difficulties of the situation, she emphasized that she would not do the same with her second daughter but would send the girl to school after just a month. Another such example arose when a number of workers expressed their willingness to change the practice of selecting a partner for their children. Adults made practical judgements when finding themselves blamed for choosing the wrong partner for their son or daughter and thus ruining their life:

I would prefer it if my children would find their own partners […] If we find someone, we do not know what will happen or whether they will be happy or not. When they find the partner and if they face problems, they will not blame us. When I have a problem or have an argument, I always think that this is my choice. I have to live with him and I have to solve my problems. My parents cannot be held responsible. (High caste female worker)

As we have noted, endogamy is seen as a defining characteristic of caste (Dumont 1980) but inter-caste marriages do sometimes occur. One low caste male worker had married a woman from a high caste. He expressed his concerns:

Normally the woman’s side gives a dowry, but when we got married, they did not give us anything as they did not like the marriage. […] Suddenly my in-laws had financial problems. They came and asked for money. I did not say, ‘I do not have money’. I wanted to become friendly with them. So, I helped them… Now all are happy, we associate with each other. We go and eat there; they too come to our house. (Low caste male worker)

His ability to help his in-laws when they encountered hardship brought considerable change to his life. Individual acts of agency and change in the social order of plantation life are therefore often relational and responsive to situations and to others, rather than strategic.

To summarise, much of the literature around agency emphasizes the “imaginative generation by actors of possible future trajectories of action” (Emirbayer and Mische 1998, 971, italics in original). In the social ecology of the plantation, opportunities for acting imaginatively, strategically and generatively to change one’s circumstances are rare. Rather, workers enact and reproduce their temporally embedded (in)visible social order on a daily basis, although small adjustments in relationships and activities sometimes occur in response to practical difficulties or as workers begin to invite each other into their homes or mothers respond to the practicalities of Kotahalu unahama. At work, practical issues related to organizational expediency may offer opportunities to individuals to improve their situation e.g. low caste individuals given a higher position because of education or language ability, but such opportunities are rare.

Subaltern, Dalit, and Critical Management Studies address identity politics and forms of resistance in caste-based societies in India and South East Asia. In these studies, urbanization, education and social and political movements are impacting social change and caste boundaries are becoming more fluid (e.g. Basnet and Ratnakar 2019; Folmar 2007; Raman 2020). However, in the social ecology of the plantation community, caste differences still persist in the daily work, everyday relationships, and social activities of people and change is slow. Overt collective acts of resistance are uncommon, related to rituals and ceremonies, and occasionally to work, but these resulted in incremental and token changes, as in the new job title for young line workers. This is perhaps because many of these plantation communities are privately owned, workers live on the plantation and therefore their work and personal lives are subject to estate management (Ramasamy 2018). Also, relationships and interactions around caste are so ingrained in the way plantation work is done that it is difficult for individuals to proactively change their circumstances. This contrasts with ethnocentric theorisations, which often afford a degree of creativity and self-determination.

8 Discussion

What emerged from the data is an understanding that agency in the plantation is enacted within the everyday lived experience and the practical circumstances of people’s lives. We began to see the importance of relationships, of moments of interaction, activity and communication that are both visible (articulated) and invisible (taken-for-granted) ways, i.e. within a social ecology. In our iterative reading of the data and the literature, we came to the notion of relational agency as a way of explaining our findings. Figure 1 offers an alternative and ‘plausible’ (Crane et al. 2016, 86) way of understanding how people experience agency. We believe that relational agency and social ecology have not been elaborated nor discussed in an empirical setting in this way in Organization and Management Studies.

We now build on theories of relational agency, which often focus on relational dynamics, relationships between academically-imposed constructs, entities, and/or materialities, by highlighting instead human, everyday relationships between people as they go about living their lives. From a hermeneutic perspective, relational agency can be understood as: temporally and relationally situated, and a dialectic of belonging/not belonging within a social ecology. These characteristics differentiate our conceptualization of relational agency from others.

8.1 Agency as Relationally and Temporally Situated

Our contribution lies in elaborating theories of relational agency, an insight that emerged inductively from the data. In interviews and informal conversations, plantation workers spoke frequently of relationships at work and home: who can interact with whom, how they orient themselves to others and engage with them, and whether inherited narratives and practices may be challenged and welcomed by individuals, families or work groups. We argue that ordinary agentic ways of being are situated in the bonds of sociality that exist between us in our everyday relationships, in our ability to account for our actions to others, and their acceptability, i.e. relational agency. In contrast to other theories, relational agency is situated in our everyday human living experience and is about the quotidian detail of lives: our feelings; actions; who we eat, work, socialise with; how we view and treat others; and whether we are accepted by them.

Ethnocentric studies of relational agency, especially in management and organization studies, often focus on agency as one’s ability to change one’s circumstances: people are wilful actors who make a difference (e.g. Abdelnour, Hasselbladh, and Kallinikos 2017; Cooren 2015; Välikangas and Carlsen 2020), or agency is distributed between materialities, actions, ways of communicating, and situated in dynamics of power and resistance (e.g. Cooren 2018). In the plantation, caste is temporally embedded and embodied in relationships, and as we have shown, the ability of workers to change their work and personal circumstances are few. In this context, we suggest that relational agency is not about change, but is also lived in everyday ways of being, in the social bonds that connect people, tie them down, or free them – in the small daily actions, interactions and decisions we make about what to do or not do. We argue that relational agency encompasses our ways of being, relating and interacting with others, i.e. agency is intersubjectively created in relationships between us. As Pham (2013) notes:

Action is rarely one’s own and rarely for one’s own sake only, for it is pulled, pushed, harmonized, agitated, coaxed, pleaded … by multiple bonds. (p. 37).

We see this in the excerpts from plantation workers, which are all about relationships with others: workers, partners, parents, children, and so on.

Our conceptualization of relational agency also differs from Emirbayer and Mische (1998), who position the self as a dialogical structure and that different modes of agency are influenced by social-psychological, structural, and cultural contexts, i.e. a degree of determinism. We humanize agency by foregrounding peoples’ lives and argue from our subjectivist, hermeneutic perspective that ‘structures’ are created and maintained by people, a position also taken by Pandey and Varkkey (2020) who, in their study of how religion-based caste impacts trade unions in India, talk of caste as a social construction, embedded in social interactions. Therefore, instead of talking ‘structures’, we argue that agency in the form of relational ways of being and acting is embedded within a social ecology, a shared context or lived space in which relationships, activities, and interactions (re)produce a social order that is taken-for-granted (invisible), articulated (visible), and accepted and maybe resisted. Social ecologies, intertwined relationships and activities, are also temporally situated in historical relations that are inherited (in)visible ways of being, relating speaking and acting in and across time: a number of workers spoke of how something has been the same for generations.

Embeddedness in a social ecology inevitably involves power relationships of some form (Sikka 2012), but an academic discussion of power as an abstract concept is not our concern. While structural and institutional studies of agency and power focus on relational dynamics and processes, we embrace Pham’s (2013) call to avoid categories such as ‘the subjugated’ and explore different modes of agency in “thick webs of sociality” (p. 29). We argue that power relationships play out in the social and relational bonds that tie people to each other and differentiate them from others. It is in these relationships that ways of being and one’s ability to act agentically in changing one’s circumstances may or may not occur. We now go on to examine the dialectics of relational agency and how ‘power’ is relationally embedded in belonging/not belonging.

8.2 Relational Agency as a Dialectic of Belonging and not Belonging

Within Organization and Management Studies, a dialectic is generally conceptualized as a contradiction and the dynamic interplay of opposites (Clegg and Cunha 2017; Putnam, Fairhurst, and Banghart 2016), which, in relation to agency, is seen as an impetus for managing change at a personal or institutional level (e.g. Hargrave and Van de Ven 2017; Seo and Creed 2002). Dialectics can also be expressed as difference and as both tension and connection between opposites.

We contribute to existing theories of relationality by arguing that agency is embedded experientially and conceptually around a dialectic of belonging and not-belonging. In our discussion of the data, we show examples of workers talking about relating and interacting with people in their own caste, eating specific food, and standing in particular places, which we have argued lies in ties of belonging. However, both high and low caste workers also talked about their actions, ways of relating, and who they are in comparison to other castes. Therefore, we argue that embedded in these ties of belonging are dialectical tensions of difference. Caste denotes difference (Chaudhry 2018) and we argue that in these differences lie an interplay of connection/unity (belonging) and tension/difference (not belonging): an interplay of opposites that appear to be (re)produced iteratively and in (in)visible ways, daily, in familial relationships, social rituals, and work practices as a social order. When workers try to act agentically and step out of accepted ways of relating and being to try to shape new relationships and practices, personal devastation may occur, experienced as a lonely, disconnected, liminal world of being neither-this-nor-that – a relational void lived outside the social order.

We suggest that power is embedded in the dialectic of belonging/not belonging, not as a structural or dynamic construct, but in the lived relationships between people. By reframing agency as embedded within a social ecology of everyday life, ordinary articulated and taken-for-granted ways of being and relating are manifest in a moral social order – moral because we account for ourselves and our actions in ways acceptable to others, e.g. we are the ‘good’ caste because we don’t drink alcohol, you stand at the back of meetings because you are low caste. From our perspective, power is not about position in a structure or self-assertion, but is embedded in complex relationships between people within a social ecology – in the sense that one is accepted or not accepted by others, included or excluded in activities, can or cannot talk with, work with, eat with, or marry another person. Relational power is manifest in some of the examples we have offered, collectively in terms of where one can sit and eat lunch or negotiating a short-term change with a Kangany, and individual in terms of finding oneself living in a relational void.

9 Conclusions

Our contribution lies in theorizing relational agency as a dialectic of belonging/not belonging within a social ecology – an ongoing flow of intertwined activities and ways of being and relating to each other that create and reproduce social orders and forms of accountability. We suggest this dialectic of belonging and not belonging works contemporaneously as people act in shared socially accountable ways of being, which both connect them to a social order but also sets them apart from others. In acting accountably, we reproduce and make sense of ourselves, our lives, relationships, and our ability to act in the social order in which we live – even though this may be limiting. By thinking about agency from this relational perspective, we begin to understand how “human agency becomes human bondage because of the very nature of human agency” (Dawe 1979, 398) and the subtle yet sometimes profound struggle people face every day as they live their lives: a struggle also associated with caste, class, race and gender. As our data shows, plantation employees spoke not about structures or systems, but how they experienced relationships and how relationships were influenced by theirs and others actions.

This way of thinking about relational agency is contrary to many conceptualizations within OMS of agency as an objectivised phenomenon with internal psychological schemas, individual capacities, agentic strategies, discourses or institutional logics, and to Critical, Postcolonial and Subaltern studies that often address agency through subject positions or intersectional categories. Our practical hermeneutic perspective illustrates human agency through the eyes of those living in a community – a social ecology is experienced as a ‘real presence’ (Steiner 1989) by those within it because taken-for-granted (in)visible ways of acting and relating with each other are embedded and reproduced in everyday life as social order.

We address Bothello, Nason, and Schnyder’s (2019) call for greater teleological and contextual diversity by examining agency within a non-westernised, non-professionalised/industrialised social ecology. In-situ interpretive studies such as ours can help further understanding of how agency is experienced in alternative social ecologies and social orders. Our findings highlight the importance of place and culture, suggesting that further research is required in non-professionalised and developing contexts as a means of offering alternative ways of understanding how people experience their ability to enact agency. We suggest that one fruitful area of study is how individual and collective agency play out from a relational perspective in contemporary alternative organizations and forms of work such as these. Understanding relational agency within a social ecology may supplement an institutional focus, for example by connecting with the work around international development in developing countries, as in Vestergaard et al.’s (2019) study of the social impact of NGOs in Ghana, where people developed their competencies but were unable to act agentically because of institutional constraints.

Our study also has implications for migrant communities and migrant workers in contemporary ‘westernised’ organizations. While a number of studies on the agency of ethnic minorities in the workplace indicate that although experienced as struggle, people can and do resist and construct new forms of agency (e.g. Essers and Benschop 2009; Van Laer and Janssens 2017; Pio and Essers 2014). However, we suggest that more studies of the lived experience of ‘not belonging’ at work and home – of how people experience their agency in circumstances of poverty (de Holan, Willi, and Fernández 2019) are important in addressing a number of society’s ‘grand challenges’, including social inequality and injustice. The notion of relational agency as belonging/not belonging may also be relevant to the experience of transnational professionals who work in different countries and encounter issues of not belonging (Skovgaard-Smith and Poulfelt 2018). Managers need to be sensitized to how different and marginalized communities in the workplace experience their ability to enact their agency, their sense of belonging/not belonging, as well as the implications of enforcing particular forms of agency for personal wellbeing and ethical and responsible organizational life.

Finally, we argue that to generate alternative ways of understanding and theorizing agency, we need an ‘epistemology of variation’ that focuses on contextual and experienced differences, rather than an ‘epistemology of generalisation’ focussing only on the objectification of experience and development of general theories. In generalizing, “the knowing subject maps the world and its problems, classifies people and projects into what is good for them” (Mignolo 2009, 2). We have attempted to embrace an epistemology of variation, which requires in-depth studies that give voice to people in different cultural contexts as a means of enriching theorizing and our practical understanding of agency. Given contemporary globalization and the movement of populations, studying relational agency within lived social ecologies is worthy of further investigation.

Appendix 1: Age and Gender Composition of Interviewees

| Age | Number of interviewees | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–20 | 1 | Male | 0 |

| Female | 1 | ||

| 21–30 | 17 | Male | 3 |

| Female | 14 | ||

| 31–40 | 21 | Male | 14 |

| Female | 7 | ||

| 41–50 | 15 | Male | 11 |

| Female | 4 | ||

| 51–60 | 3 | Male | 2 |

| Female | 1 | ||

| 61–70 | 1 | Male | 1 |

| Female | 0 | ||

| Total | 58 | Male | 31 |

| Female | 27 | ||

The following respondents age and gender is incorporated in Appendix 1.

| Senior Manager (Male 42) Deputy Manager (Male 25) Assistant Manager (Male 23) Senior Field Officer (Male 38) Chief Store Keeper (Male 37) 2 Field Officers (Males 37 and 30) 3 Kanganies (Males 38, 42, 53) |

Midwife (Female 30) Apothecary (Male 32) Religious leader (Male 50) School Principal (Male 47) Two teachers (Females of 30 and 32) Secretary (Female 44) |

References

Abdelnour, S., H. Hasselbladh, and J. Kallinikos. 2017. “Agency and Institutions in Organization Studies.” Organization Studies 38 (12): 1775–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617708007.Suche in Google Scholar

Abrams, P. 1982. Historical Sociology. New York: Cornell University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Alawattage, C., and D. Wickramasinghe. 2009. “Institutionalisation of Control and Accounting for Bonded Labour in Colonial Plantations: A Historical Analysis.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 20 (6): 701–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2009.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Appadurai, A. 1981. “Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia.” American Ethnologist 8 (3): 494–511.10.1525/ae.1981.8.3.02a00050Suche in Google Scholar

Archer, M. S. 2007. Making Our Way through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511618932Suche in Google Scholar

Atkinson, P. A. 2015. For Ethnography. London: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Baak, P. E. 1999. “About Enslaved Ex-Slaves, Uncaptured Contract Coolies and Unfreed Freedmen: Some Notes about ‘Free’ and ‘Unfree’ Labour in the Context of Plantation Development in Southwest India, Early Sixteenth Century–Mid 1990s.” Modern Asian Studies 33 (1): 121–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X99003108.10.1017/S0026749X99003108Suche in Google Scholar

Bamber, M., J. Allen-Collinson, and J. McCormack. 2017. “Occupational Limbo, Transitional Liminality and Permanent Liminality: New Conceptual Distinctions.” Human Relations 70 (12): 1514–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717706535.Suche in Google Scholar

Bapuji, H., and S. Chrispal. 2020. “Understanding Economic Inequality through the Lens of Caste.” Journal of Business Ethics 162 (3): 533–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3998-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Barad, K. 1998. “Getting Real: Technoscientific Practices and the Materialization of Reality.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 10 (2): 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-10-2-87.Suche in Google Scholar

Basnet, C., and J. Ratnakar. 2019. “Crossing the Caste and Ethnic Boundaries: Love and Intermarriage between Madhesi Men and Pahadi Women in Southern Nepal.” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.5802.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Bothello, J., R. S. Nason, and G. Schnyder. 2019. “Institutional Voids and Organization Studies: Towards an Epistemological Rupture.” Organization Studies 40 (10): 1499–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618819037.Suche in Google Scholar

Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Suche in Google Scholar

Broadfoot, K., D. Munshi, and J. Cruz. 2017. “Releasing/Translating Agency: A Postcolonial Disruption of the Master’s Voice Among Liberian Market Women.” In The Agency of Organizing: Perspectives and Case Studies, edited by B. Brummans, 123–41. New York: Taylor and Francis.10.4324/9781315622514-6Suche in Google Scholar

Bryer, A. 2019. “Making Organizations More Inclusive: The Work of Belonging.” Organization Studies 41 (5): 641–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618814576.Suche in Google Scholar

Burkitt, I. 2016. “Relational Agency: Relational Sociology, Agency and Interaction.” European Journal of Social Theory 19 (3): 322–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431015591426.Suche in Google Scholar

Chakravarti, U. 1993. “Conceptualising Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early India: Gender, Caste, Class and State.” Economic and Political Weekly 28 (14): 579–85.Suche in Google Scholar

Chatterjee, P. 2012. “After Subaltern Studies.” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (35): 44–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Chaudhry, S. 2018. “‘Flexible’ Caste Boundaries: Cross-Regional Marriage as Mixed Marriage in Rural North India.” Contemporary South Asia 27 (2): 214–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2018.1536694.Suche in Google Scholar

Chowdhry, P. 2004. “Caste Panchayats and the Policing of Marriage in Haryana: Enforcing Kinship and Territorial Exogamy.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 38 (1–2): 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670403800102.Suche in Google Scholar

Clegg, S. R., and M. P. Cunha. 2017. “Organizational Dialectics.” In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Paradox, edited by W. K. Smith, M. W. Lewis, P. Jarzabkowski and A. Langley, 105–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198754428.013.5Suche in Google Scholar

Cooren, F. 2015. “Studying Agency from a Ventriloqual Perspective.” Management Communication Quarterly 29 (3): 475–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318915584825.Suche in Google Scholar

Cooren, F. 2018. “Acting for, with, and through: A Relational Perspective on Agency in MSF’s Organizing.” In The Agency of Organizing: Perspectives and Case Studies, edited by B. H. J. M. Brumans, 142–69. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315622514-7Suche in Google Scholar

Crane, A., I. Henriques, B. W. Husted, and D. Matten. 2016. “What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution in the Business and Society Field?” Business & Society 55 (6): 783–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316651343.Suche in Google Scholar

Creed, W. E. D., R. DeJordy, and J. Lok. 2010. “Being the Change: Resolving Institutional Contradiction through Identity Work.” Academy of Management Journal 53: 1336–64. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2010.57318357.Suche in Google Scholar

Cunliffe, A. L. 2011. “Crafting Qualitative Research: Morgan and Smircich 30 Years on.” Organizational Research Methods 14 (4): 647–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110373658.Suche in Google Scholar

Cunliffe, A. L. 2022. “Must I Grow a Pair of Balls to Theorize about Theory in Organization and Management Studies?” Organization Theory 3 (3): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877221109277.Suche in Google Scholar