Abstract

The article analyzes the investigations conducted by the Berlin police into the subsequent perpetrator of the vehicle-ramming attack at a Berlin Christmas market on December 19, 2016. We explore why the police closed these investigations prematurely and thereby focus on an attempt to prevent lone actor terrorism. The analysis shows that the police closed its investigations owing to organizational dynamics driven by an increasing need to justify further resource investments in the face of absent conclusive evidence and scarce resources in relation to the organizational case ecology. We propose hypotheses for future research and formulate three contributions to existing research on the sociology of police, terrorism prevention, and lone actor research.

1 Introduction[1]

Terrorism is fundamentally an organized field of modern societies with organizations on both sides.[2] On the one hand, organizations are responsible for a substantial number of terrorist attacks while the field of terrorism prevention is dominated by formal and bureaucratic organizations, including the military, intelligence services, and the police (Silke 2019a). Despite their relevance, the intersection of terrorism and organizations is, in important regards, uncharted territory (see James 2011), with counterterrorism specifically “being […] nearly a terra incognita” (Brodeur 2010, 187).

A natural candidate for research on terrorism, organizational research views terrorism, with very few exceptions (Sutcliffe and Weick 2008), as an exogenous shock challenging corporate resilience (see Hepfer and Lawrence 2022). Terrorism research, on the other hand, focuses on terrorist organizations (Crenshaw 2014), studying their forms (Mayntz 2004), goal conflicts (Volders 2021), or mortality (Goldman and Bar 2020). This constitution of the research field leaves the organized actors who seek to prevent terrorism unexplored.

The present study addresses this research gap by analyzing the investigations conducted by the Berlin police into the subsequent perpetrator of a terrorist attack, Tunisian-born Anis Amri. On the evening of December 19, 2016, after having shot the driver, Amri drove a hijacked truck into the Christmas market next to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church on Breitscheidplatz in Berlin, killing 12 and injuring more than 170 people (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 165). The attack exemplifies a specific form of terrorism that we will focus on here, namely, attacks carried out by lone actors, that is, by individual perpetrators unattached to any formal organizations and not acting on direct orders (Lindekilde, Malthaner, and O’Connor 2019, 23).

The case of the Berlin truck attack is intriguing from an organizational perspective because it involves an empirical puzzle. Shortly after Amri entered Germany, the police became aware of him because he had contacts with radical groups, openly stated his intention to carry out a terrorist attack and was involved in criminal activity. Consequently, a Berlin court ordered the police to investigate Amri up until September 2016, granting them invasive means for this purpose. However, the police prematurely phased out its investigations in August 2016 instead of investigating Amri right up until September (see Deutscher Bundestag 2021).

The present study seeks to explain why the Berlin police, despite being aware of Amri’s intentions, prematurely closed its investigations. For this purpose, we conceive of the police as an organization handling a specific caseload, which we refer to as case ecology, operating with limited resources and an artificial structure (Luhmann 1995; Simon 1981) that impacts the perception of their environment (Joseph and Gaba 2020). Further, we theorize police investigations as bounded rational and resource-intense routines.

The findings show that the Berlin police prematurely closed their investigations as the result of a dynamic created by the investigation’s resource intensity and the organizational case ecology. As the bounded rational investigations fail to produce conclusive evidence for any actual planning of an attack, the investigators face a mounting burden to justify further investigations due to a high caseload. Eventually, this dynamic incentivizes disambiguating Amri, who is perceived through the organizational structure as a borderline case between political motivated and general crime, as a criminal case. To this end, the investigators make use of a heuristic operationalizing the differentiation of the police and, thereby, compensating for the uncertainty about Amri’s motives. Building upon these results, we formulate four theoretical propositions for future research.

This article offers three contributions. First, we contribute to current research on terrorism prevention by providing an in-depth case study of police terrorism prevention investigations which addresses a vital research gap. Second, we contribute to the sociology of the police by developing a theoretical model accounting for investigative dynamics unfolding between case ecology, bounded rational investigative routines, and differentiation. Third, we contribute to research on lone actor counterterrorism by elucidating the organizational side of preventing lone actor terrorism.

In the first step, we reconstruct the state of research (Section 2) before expounding our theoretical perspective (Section 3). Subsequently, we present our methodical approach (Section 4) and our analysis (Section 5). We then put forward our explanatory model and infer propositions from it (Section 6), before discussing our results (Section 7) and drawing a conclusion (Section 8).

2 Organizational Approaches to Terrorism

Terrorism is a marginal topic in organization studies, although research on (counter-)terrorism—mirroring the border research landscape (Silke 2019b)—gained prominence after 9/11. In the main, organizational research addresses terrorism in terms of organizational resilience, defined as “the ability of an organization to anticipate, respond to, recover from, and learn from adversity” (Hepfer and Lawrence 2022, 8). Following early research (Coutu 2002), Quinn and Worline (2008) prominently demonstrate the relevance of narratives for enabling and organizing resilience using the example of the passengers of Flight 93. Moving from operational to strategic resilience, Gittell et al. (2006) analyze readaptation of airlines after 9/11. In a similar vein, Sullivan-Taylor and Wilson (2009) show how perception of terrorist threats differ across the travel and leisure industry, leading to different modes of adoption. These and comparable works (Hepfer and Lawrence 2022) converge in viewing terrorism as an exogenous shock from the point of view of corporations.

Closely related to the resilience perspective are sensemaking studies. The study conducted by Kent (2019) examined the connection between individuals’ responses to terrorism and their workplace, and how various narratives either provide significance to their work or deprive it of meaning. Sutcliffe and Weick (2008) deviate from this corporate focus by examining the inquiry by the Federal Bureau of Investigation after the 2003 Madrid train attacks. They focus on why the investigators wrongfully arrested a lawyer from Oregon. The authors demonstrate that the investigators failed to adequately make sense of the existing information due to several factors, including stress and pressure to succeed. This study resembles the classic one by Roberta Wohlstetter researching why the US military failed to heed the warning of a pending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (1962). More recently, Cornelissen, Mantere, and Vaara (2014) also focus on the police in their account of a failed operation of the British police that led to the death of an innocent person, showing how stress and routines impaired sensemaking and reinforced premises for taking the wrong course of action. In an insightful study not specifically concerned with terrorism, Schakel, van Fenema, and Faraj (2016) analyze police investigations in response to the sudden killing of a suspect. Following the literature on fast-response organizations (Faraj and Xiao 2006), the authors demonstrate how different coordination challenges, including communication technology and team composition, impaired switching between different routines.

While organization studies, with few exceptions, focus on corporations, terrorism research with its strong emphasis on organizations (Crenshaw 2014; Torres-Soriano 2021, 1363–64) mostly concentrates on terrorist organizations. Following Simmel’s work on secret societies (1906), one research path addresses the goal conflicts of terrorist organizations rooted in the requirement to both ensure operational safety and efficiency (Kilberg 2019; Volders 2021). Another approach analyzes the organizational forms of terrorist organizations (Mayntz 2004) and how their structures impact their lethality (Asal and Rethemeyer 2008), for instance, regarding the organizational embeddedness of suicide bombers (Warner, Chapin, and Sorenson 2021). The theoretical link of these studies to organization theory is, with a few outliers (Mayntz 2004; Volders 2021), relatively weak despite some common areas of interest such as clandestine organizations (Grey 2014; Schoeneborn and Scherer 2012).

Despite the prominence of organizations in terrorism research, the literature on preventing terrorism is dominated by policy analyses (see Silke 2019b), concentrating on the effectiveness of specific policy measures (Crenshaw 2014, 559) to prevent the survival of terrorist organizations (Goldman and Bar 2020), such as targeted killings (Price 2012). As the latter implies, these studies focus on a military approach to terrorism (Boyle 2019). Police approaches to terrorism (Clutterbuck 2019), on the other hand, are often considered to suffer from a lack of data, leading to a situation whereby “very little is known about the nature and effectiveness of police counterterrorism responses and strategies” (Lum et al. 2011, 103).

One of the few organization-sensitive approaches to counterterrorism is a study by Bye et al. (2019) who analyze the Norwegian police response to the 2011 terror attacks in Oslo, arguing that a failure to recentralize was pivotal for the failed police response (Bye et al. 2019, 69). More representative of the literature on police and terrorism, Hewitt (2014) evaluates the effectiveness of various police tactics. He argues that “undercover agents and informants” are success factors (2014, 66) enabling the police to prevent acts of terrorism. Along the same lines, Bayley and Weisburd (2011) underscore the significance of the public for terrorism prevention, concluding that general duties police officers may harness a community policing approach for a more active role in terrorism prevention (Bayley and Weisburd 2011, 95–96; Randol 2012). However, the authors also point out the risk of the police losing community trust when engaging in this type of “high policing” (Brodeur 2010).

The literature review reveals that organizational research on terrorism primarily focuses on corporate resilience with only the study by Weick and Sutcliffe examining police investigations but without specifically addressing organizational dynamics. The dearth of studies of terrorism prevention is mirrored by the policy focus of terrorism research. The focal study addresses this research gap by analyzing the terrorism prevention investigations in the run-up to the Berlin Christmas market attack. In the next step, we elaborate on our theoretical perspective.

3 An Organizational Perspective on the Police

Police organizations are highly differentiated orders (Brodeur 2010; Jobard and de Maillard 2016), mostly combining spatial and functional differentiation principles. Spatially, the police are differentiated according to geographical responsibilities. In Germany, this means that besides a federal police agency operating at national level, each state has its own police (Frevel and Groß 2016).

The functional differentiation of the police, with some exceptions regarding cross-sectional tasks such as observations, follows a system of categorizing crime. In this categorical system, criminal acts considered to be terrorism are subsumed under the category of politically motivated crime which is distinguished from other superordinate categories such as general, corporate, and organized crime. Within the category of politically motivated crimes, the German police further distinguishes left-wing, right-wing, and religiously motivated crime. Structurally, these distinctions translate into specialized divisions for each of these categories under the umbrella of the department for politically motivated crimes.

Organizational structures affect how organizations perceive their environment (Joseph and Gaba 2020; Simon 1949). In the case of the police, the system of crime categories and the organizational differentiation resulting from this structure how the organization perceives its environment by demarcating jurisdictions, thereby channeling attention to areas of formal responsibility (see Monjardet 1996). For police investigations, this means that the way a criminal act is categorized is a decisive factor for which department is responsible for the case. If evidence is unearthed that a criminal act is wrongly categorized, for instance, because a background in organized crime is assumed when the act was motivated by an extremist right-wing ideology, case responsibility is transferred to a different department and the corresponding division. This migration of responsibility to specialized investigative departments underscores the bureaucratic nature of the police (Jobard and de Maillard 2016; Monjardet 1996).

The categorical structure of the police is an artificial structure (Simon 1981) within a complex (Luhmann 1995) and highly ambiguous environment (March and Olsen 1976). Consequently, the structure of the police presents a reduction in complexity compared to its environment (Luhmann 1995). The structure does not depict the organization’s environment phenomenologically accurately but serves to organize agency. Therefore, the underlying category system frequently creates borderline cases since it maps clearly delineated organizational jurisdictions onto criminal acts with properties fitting multiple categories. These borderline cases include, for instance, groups categorized as terrorist structures engaging in organized crime (Jamieson 2005) or organized crime actors using terrorist techniques (Puttonen and Romiti 2022).

Having elaborated the organizational structure, we then theorize the investigations themselves. By investigations, we refer to “proactive and suspect-centered” investigations (Brodeur 2010, 200) aimed at preventing future crimes. Investigations of this type are typical of terrorism prevention and in marked contrast to reactive investigations taking place after the commission of a crime. A hallmark of these proactive investigations is that they face fundamental uncertainty regarding the intentions and future actions of an individual suspect. To absorb this uncertainty, the police engage an array of surveillance techniques to determine whether a suspicion is warranted. Only when this is the case can the police take further steps. Consequently, the goal of investigations is not to prevent an attack per se, but, rather, to determine whether a suspicion is warranted.

We consider investigations as organizational routines which we understand to be a “repetitive, recognizable pattern of interdependent actions, involving multiple actors” (Feldman and Pentland 2003, 96). A routine understanding of investigations is helpful because it directs our attention to the concatenation and coordination (Schakel, van Fenema, and Faraj 2016) of patterned actions (Feldman et al. 2021) typical of investigations and interfaced by files due to the bureaucratic nature of the police (Kremser, Pentland, and Brunswicker 2019). This routine understanding emphasizes that police investigations are organizational in character and presuppose the existence of organizations.

Investigative routines are resource intensive and require various organizational assets, including investigators, observation teams, cars, officers evaluating audio and/or video files, or translators, to name just a few. As police organizations possess only limited resources, investigations are consequently impacted by the organizational case ecology which we define as the overall case load a police organization, or a specific unit, has to investigate. This case ecology restricts how many resources a police organization can dedicate to individual investigation routines (see Klinger 1997). Hence, it impacts both the depth and thoroughness of investigations and may eventually lead to the relegation of a case. The only investigations protected from these dynamics are those that are able to substantiate a suspicion and, by doing so, both legitimate and necessitate further resource investments, for example, by finding concrete evidence for the planning of an attack.

A final important characteristic of investigation routines is their bounded rationality (Simon 1979) resulting from investigations usually yielding only incomplete information about the entity under investigation. Making up for incomplete information, investigators, much like beat officers (Newburn 2022, 441), resort to compensatory heuristics, that is, frugal decision rules (see Gigerenzer, Reb, and Luan 2022) to deal with uncertainty. The focal case showcases that these heuristics may operationalize the reductive category system undergirding the organizational structure and are thus a testament to organizational self-reference (Luhmann 1995). Before we illustrate this empirically, we will first present our research design, data, and data analysis.

4 Methodology

Owing to the lack of relevant previous research, we designed our study as a qualitative case study (Yin 2018). Duration and complexity of our subject matter also necessitated such a research design as case studies are particularly well suited to creating an in-depth understanding of complex events (Flyvbjerg 2006). Posing the question why the Berlin police closed its investigations into Amri prematurely (cf. Yin 2018, 27), we delimit our case in three regards: Factually to police investigations, socially to the Berlin police, and temporally to the run-up to the attack (Luhmann 1995).

The investigations conducted by the Berlin police present a “revelatory case” (Yin 2018, 50) for several reasons. First, the case and its subsequent parliamentary examination, which we will address below, present us with a rare opportunity to examine police attempts to prevent terrorism. Second, the case is characterized by an empirical puzzle instructive for theory building, as the Berlin police had information that Amri was planning an attack and still closed its investigations prematurely. Third, the Berlin truck attack is typical of the recent wave of IS-inspired lone actor attacks in Europe and thus promises to provide theoretical clues that can be tested on a wider range of cases.

4.1 Data Collection

The main data source of our analysis is the 1800-page long report published by the inquiry commission of the German parliament on the Berlin Christmas market attack and its related investigations (Deutscher Bundestag 2021). The report gathered data on three interrelated aspects: It examined what information the German authorities had on the perpetrator regarding potential sponsors, accomplices, and supporters, sought to identify the reasons for the failed investigations in the run-up to the attack, and looked at the post-attack investigations (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 44).

The primary data source of the report contains verbatim quotes from hearings of a broad array of individuals. These can be grouped into persons concerned with the case, including investigators, judges, officials from different law enforcement and administrative bodies and experts from different professions, including lawyers, legal experts, or theologists. Additionally, the report reproduces case-related documents, such as database entries, asylum seeker registrations, investigation files, and videos.

The data in the inquiry report are well suited to our research endeavor for several reasons. To begin with, the data collected in the report fits our research question, as our interest aligns with the goals of the inquiry. Further, the result of interviewing 147 witnesses over 462 h (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 84), the report provides an exhaustive dataset that would have been virtually impossible to achieve by individual researchers (see Vaughan 2004, 333). This also applies to data depth and quality as the inquiry commission was entitled to subpoena members of law enforcement agencies, and to clear and inspect non-public files.

To cross-check our main data source, we also studied the inquiry reports issued both by the state of North Rhine-Westphalia (2022) and the Berlin senate (Jost 2017) as well as reports from the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (2016) and the Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesministerium des Inneren 2016). Additional sources were a legal case evaluation (Kretschmer 2017) and an official chronology of law enforcements agencies’ actions (BMI 2017). The following Table 1 gives an overview of these sources.

Data sources.

| Source of data | Nature of data | Number of pages |

|---|---|---|

| Primary data | ||

| Bundestag inquiry report (Deutscher Bundestag 2021) | Hearing transcripts, investigation files, official communication, email correspondences | 1820 |

| Inquiry report from the state of North Rhine Westphalia (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen 2022) | Hearing transcripts, investigation files, official communication, email correspondences | 826 |

| Berlin senate inquiry report (Jost 2017) | Investigation files, official communication, email correspondences | 80 |

| Legal case evaluation (Kretschmer 2017) | Criminal proceeding files, investigation files | 105 |

| Official chronology (BMI 2017) | Timeline of official actions | 20 |

| Secondary data | ||

| Federal intelligence reports 2016 (Bundesministerium des Inneren 2016) | Assessment of extremist movements in Germany | 317 |

| Migration report 2016 (BAMF 2016) | Statistical data and legal framework | 276 |

Inquiry reports constitute “a large body of valuable data on the powerful governmental […] organizations in our society […]” (Perrow 2014, 177). At the same time, they confront researchers with challenges upon which we next reflect.

A first challenge results from the political character of inquiry commissions, which tend to construct meaning in a way that resolves ambiguities and equivocality (Brown 2003). We addressed this challenge by focusing solely on the data points, ignoring all synthesizing conclusions drawn by the report. This approach was helped by the inquiry report resembling less an authoritative account than a data repository. Naturally, focusing on data points does not eliminate biased representation in the data. Consequently, when coding data, we ensured our categories were empirically saturated and hence firmly rooted in our data. To consider a category saturated, we did not only collect data until “no new information” emerged (Strauss and Corbin 1998, 136), but made it an additional requirement to include only data confirmed by multiple sources.

A second challenge is that police investigations involve classified data which are not made public in reports and are thus inaccessible to researchers. While we readily admit that this is a limiting factor, we strongly contest the argument that this makes analyzing existing data fruitless for several reasons. First, we build an explanatory model firmly anchored in data verified by multiple sources. Hence, we consider it not likely that our explanation is falsified by classified data, in particular as classified data usually pertains to the identity of informants, clandestine procedures, alleged whereabouts of individuals wanted for questioning, etc. – none of which has a strong bearing on our argument. Second, and closely related to this point, secrecy does not denote, as Simmel explains, something “essential and significant” (Simmel 1906, 465). As suggested above, the police classify information for different reasons, and it is by no means self-evident that what is classified for tactical or legal reasons is also sociologically relevant. In other words, the existence of classified data does not prove its sociological relevance; much less do clandestine data possess analytical superiority in comparison to a robust body of public data. On the contrary, emphasizing the secret nature of counterterrorism investigations risks falling prey to the rationality myth that extraordinary events such as failed investigations have equally extraordinary causes. After all, the police force is a bureaucratic organization (Jobard and de Maillard 2016) and investigations are decentralized routines interfaced by files and no arcane organizational activity. As such, police investigations are open to organizational analysis. This analysis is described below.

4.2 Data Analysis

Data analysis comprised a four-step process based upon the Gioia methodology (2021) because of this methodology’s suitability for analyzing revelatory cases (Langley and Abdallah 2011, 109).

Our analysis began with reading through our notes and discussing preliminary ideas. At this stage, we open coded our data to identify first-order categories, arriving at roughly 50 categories for which we could claim empirical saturation (Glaser and Strauss 2006). We worked independently of each other in this step and used contradictions to refine our codes. Additionally, we wrote a case history at this stage to bring our data into chronological order to aid our procedural understanding of the case.

In the next phase of the research process, we grouped our first-order categories into first-order concepts by identifying overarching themes in the material. We identified, inter alia, “politically motivated crime”, “general crime”, “drugs”, ”LKA 54”, and “dangerous persons” (‘Gefährder’) as relevant first-order concepts. To ensure intercoder reliability, we determined coding rules by creating anchor examples. This helped us prevent assigning data to multiple concepts, for instance, by distinguishing between consumption and trafficking for the concepts of “drugs” and “general crime”.

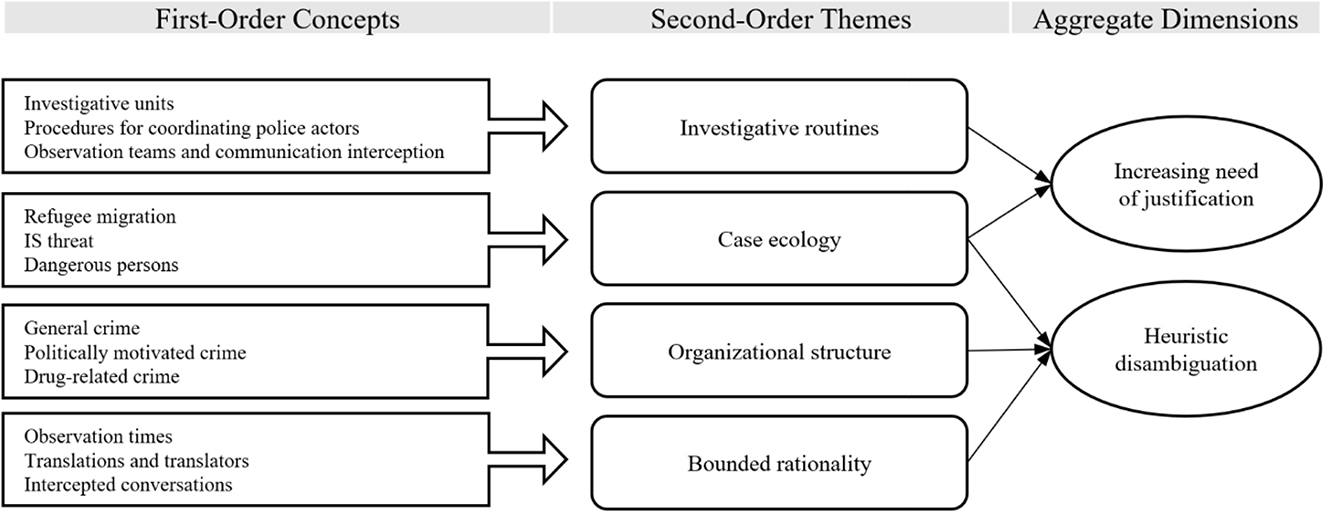

In the next step, we drew on our theoretical perspective to create second-order themes based on our first-order concepts (Strauss and Corbin 1998). To identify analytical themes in our material, we alternated between data and theory. We aggregated the categories “general crime”, “politically motivated crime”, and “drug-related crime” into the theme “organizational structure”, the categories “observation times”, “translations and translators”, and “intercepted conversations” into the theme “bounded rationality”, the categories “dangerous persons”, “IS threat”, and “refugee immigration” into “case ecology”, and “investigation units”, “observation teams and software for intercepting communication”, and “procedures for coordinating police actor” into “investigative routines”.

Since the objective of our study is to explain the outcome of a process, we deviated from the Gioia methodology in the last stage of our research. Instead of distilling our second-order themes further, we traced the dynamic unfolding between them over the course of the investigation. To trace this dynamic, we related our identified themes to each other and thereby distilled two aggregate dimensions. We found that the themes “investigative routine” and “case ecology” were connected through a process of an increasing need for justification, while the themes “bounded rationality”, “case ecology”, and “organizational structure” were linked by a process of heuristic disambiguation. Following this step, we wrote our explanatory model. Figure 1 below shows our data structure:

Data structure.

To add validity to our conclusions, each researcher developed an explanation individually for our research question. We used differences between our models to refine our explanatory model until it came to the point where it accommodated both perspectives. Although we could not contrast our model with alternative explanations due to a lack of research on the subject to date, we compared it to prevalent understandings of terrorism prevention and results from neighboring disciplines (see the discussion section). Finally, we sought feedback from high-ranking and long-serving police officers whom we had previously encountered during other research projects to review and critically evaluate our results (Yin 2018). This provided further clarification for our explanatory model.

5 Results

In this section, we present the results of our analysis. We integrate both empirical reconstruction and theoretical reflection in this presentation.

5.1 Case Ecology

The police are an organization with bounded resources. For this reason, the organizational case ecology has an impact on the resources that a police organization may allocate to investigations. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an understanding of the organizational case ecology at the time of the investigations against Amri.

In 2014, the number of people looking for asylum in Germany surged. While 34,000 people per year sought shelter in Germany between 2003 and 2012, there were 173,000 asylum seekers registered in 2014 (Herbert and Schönhagen 2020, 27). In 2015, the comparable figure increased to a historic peak of 441,900 (BAMF 2016, 8), primarily because of the Syrian civil war.

From 2014 onward and parallel to the refugee movement, lone actors inspired by the IS began to commit terror attacks in Europe. Motivated by a strategic change in response to mounting territorial losses (Piazza and Soules 2021), IS recommended its followers:

One should not complicate the attacks by involving other parties, purchasing complex materials, or communicating with weak-hearted individuals (Ellis 2016, 41).

The German Federal Intelligence Service evaluated the resulting situation as follows:

In the face of the continuing migratory movement toward Germany, it is expected that active and former members, supporters and people sympathizing with terror organizations are among the refugees (Bundesministerium des Inneren 2016, 164).[3]

A public prosecutor confirmed:

[…] my colleagues and I were confronted with a situation whereby within the influx of people there was a relatively small proportion of people relevant to us […]. In absolute numbers, however, their number was still in the three-digit range (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 634).

This development is evident in the number of “dangerous persons” (Gefährder), defined by the police as individuals for which “certain facts justify the assumption that these people will carry out politically motivated criminal acts of considerable significance” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 831f.). According to (Jost 2017, 28) their number rose “drastically […] from 330 in June 2015 […] to 690 in July 2017”:

Viewed objectively, there was a large reservoir of young people […] inspired by the relatively attractive propaganda of the IS on the Internet. The task for us was to identify those who actually wanted to commit an attack through a wide variety of investigations (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 634; emphasis added).

Emphasizing those “who actually wanted to commit an attack”, the cited prosecutor indicates that the police faced substantial uncertainty as not all individuals considered to be dangerous actually planned an attack. The statement also underscores the fact that police investigations were the means to reduce this uncertainty.

Reconstructing the social context of the investigations allows two observations relevant for the dynamics of the investigations. First, both the refugee movement and the IS threat increased the caseload for law enforcement agencies. Second, the police were tasked with ascertaining whether someone was actually planning an attack through investigations. As these investigations required a judgement about future behavior, they implied significant uncertainty.

5.2 Investigative Routines and Bounded Rationality

Upon arrival in Germany in June 2015, Amri attracted the attention of German state police on several occasions. After he had aggressively professed his sympathy for IS to a roommate (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 296f.), the police of North Rhine-Westphalia investigated him, and only weeks later the State Criminal Office of Berlin also took notice of him while working through a list of people brought to police attention after the Paris terror attacks of November 15 (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 587).

The Berlin police began its investigations in February 2016 when Amri started to spend most of his time in Berlin. These investigations built on the findings conveyed by the police of North Rhine-Westphalia:

Amri aggressively tried to recruit individuals as participants in Islamist-motivated attacks in Germany. He intended to arm himself with AK47 rapid fire rifles. Recently, Amri was planning to procure the necessary financial means through burglaries (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 591).

Based on this information, the district attorney (Generalstaatsanwaltschaft) of Berlin evaluated whether it was possible to prosecute Amri according to Section 89a of the Criminal Code for preparing to commit a serious act of violence against the state (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 630ff.):

Yes, Section 89a of the Criminal Code requires very specific acts. […] it requires at least rudimentary actions. That is, the successful procurement of a weapon, the procurement of explosives or the like. And it is precisely these details, concrete actions […] that were missing […] (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 631, emphasis added).

The above quote shows that the judge concluded that charging Amri with such a major offense was not possible due to a lack of concrete evidence (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 631). At the same time, an investigator explains, statements such as “I also want to do something” or “I can get weapons” were just as common as was searching online for instructions on how to build bombs (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 779). An official of the German Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt) reaffirms that “countless Islamists” frequently said these things (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 545). From this perspective, Amri was just one case “out of a great number of young people, overwhelmingly men” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 633).

The data reveal that Amri’s evaluation is genuinely organizational as the law enforcement agencies judge the case in the context of the organizational case ecology. In other words, when viewed in isolation, the information conveyed to the Berlin police led to the conclusion that Amri was a highly dangerous person, while a view through the lens of the organizational case ecology puts this apparently self-explanatory assessment in perspective. The statements also make clear that, to prioritize Amri over other cases, the police required concrete evidence.

Despite the decision not to prosecute Amri for planning a serious crime against the state, the available information was sufficient to open a case on suspicion of participating in a homicide (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 632). For the resulting investigations, the investigators could work with “big cutlery” or, to put it another way, “bring in the big guns,” (“großes Besteck”) (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 634, cf. 5.1) as “almost all […] legal surveillance measures” were at their disposal (Jost 2017, 47). The legal mandate was extended twice and remained valid until the end of September (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 646).

The Berlin police assigned the responsibility for the investigations against Amri to the division in charge of religiously motivated crime, LKA 54, which was one of several divisions in the department responsible for politically motivated crimes. In so doing, the police acted in accordance with their underlying categorical system.

The investigations conducted by LKA 54 present an organizational routine as they required coordinated action by numerous decentralized actors. This characteristic of the investigations is evident both in the observations of Amri and in the surveillance of his communication. Next, we examine the investigative routines in more depth to provide a clearer picture of their rationality and the informational basis they generated and upon which the investigators had to evaluate Amri.

Observations in the Berlin police were not carried out by investigators themselves but by a specialized unit organized in a separate division, LKA 6, upon which all investigative divisions from all departments can call. This meant that the department for politically motivated crime first had to determine how the observation needs of the various in-house divisions (left-wing, right-wing, and religiously motivated crime) were to be prioritized (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 623). Once an internal priority ranking was decided, the requests, in order of priority, were transferred to LKA 6. In addition, the LKA 6 also received requests from all other departments of the Berlin police, including those responsible for organized crime, homicides, and fraud. LKA 6

[…] then decided on the allocation of forces, the deferral of requests or their assignment to other observation forces. […] Finally, [LKA 6] reported back [to the respective investigative units, including LKA 54], which persons were likely to be observed by which forces on which days (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 623).

As of mid-April, LKA 54 put Amri either in the first or second position of its priority list (see Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 635f.) and LKA 6 decided to observe Amri for 30–35 days (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 635):

The periods [of observation] were always from Monday to Friday and lasted from late morning to 11:00 p.m. (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 636f.).

Both the times and dates indicate that the observations were selective and thus could only provide an incomplete picture of Amri’s behavior. The selectivity was due to the resource heaviness of more comprehensive observations and the consequences for other investigations. When pressed why Amri was not the subject of a 24/7 observation, one investigator explained:

In the event of 24/7 observation, there is barely an observation team left to do anything else intensively and in breadth (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 639).

To surveil Amri’s communication, the police relied on software that automatically recorded his conversations. Up until September 2016, a total of 7685 conversations were recorded, of which 2429 had actual content (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 646). For conversations in German, the police officer in charge created an overview of statements that seemed pivotal. For those in Arabic, the police had to rely on translators for German translations.

Well, […] the translator came to the police station and […] listened to it and then wrote it down […]. It was always dependent on the availability of the translator (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 647).

While the availability of translators added some arbitrariness to the time of the translations, the police did not peruse all recorded conversations but only those that “indicated an extremist view” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 647). This selectivity resulted in some pivotal information being lost, for example, a hint at a potentially still-existing passport that could have enabled the German authorities to enforce Amri’s extradition (Jost 2017, 19) as he was legally obliged since June 2016 to leave the country (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 856). Another problem was that some translations were shortened to the point of distorting the actual meaning of the conversation (Jost 2017, 44). An original transcript of a recorded conversation read:

Anis is on his way to Dortmund. He has a court date coming up. It’s about his asylum application (Jost 2017, 44).

The inquirer for the Berlin senate later had the same recording retranslated. The retranslation revealed a much more complex picture than the original translation. Instead of reducing the conversation to Amri being on his way to Dortmund for a court date, it noted:

During the interview at the BAMF [Federal Office for Migration and Refugees] today, Anis said that he was Egyptian and that he had gotten into trouble […] because he was a supporter of Mursi. The Moroccan interpreter […] saw through his alias but assured him that it would work out well "like this" and that he should continue (Jost 2017, 44).

Reconstructing both observation and surveillance routines allows us to formulate four pivotal insights. First, when viewed in the context of the organizational case ecology, Amri was just one of many cases if no evidence corroborated the actual planning of an attack. Second, as the investigative routines are resource intensive and not fully under the control of LKA 54, they needed to be justified in relation to other cases. Third, the investigative routines generate only selective information about Amri’s behavior despite him being a priority target of invasive measures and can thus be said to be bounded rational. Fourth, as a result, the investigators had to evaluate Amri under considerable uncertainty.

5.3 Increasing Need for Justification

In February 2016, the Berlin police confiscated Amri’s cell phone. The analysis of the phone shows Amri in contact with “various people [from] the Salafist/Islamist scene”:

That was already significant, but only underscored the image we already had of him anyway. […] In my eyes, he was highly dangerous (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 618).

In the following weeks, the picture noted by the investigator above began to change. While Amri seemed “in April […] still relatively […] concerned with the cause of Islam” and was “regularly attending mosques” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 652), the police also learned that Amri dealt and used recreational drugs (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen 2022, 110). Moreover, as far as the investigators were concerned, Amri began to neglect religious rituals and holidays and utilized his radical Islamist contacts solely for the purposes of finding places to stay and work (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 651ff.). After a brief episode in which Amri again “turned somewhat more toward Islam” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 839), “his radius of movement” was limited mainly to the “drug scene” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 652). He veered “again very strongly […] towards drug crime” and his “very unsteady lifestyle with his own drug use” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 839).

Overall, the investigators formed the following impression:

On the one hand, Islamist thinking, on the other hand, conversations about potential criminal activities like theft or fraud (BMI 2017, 11).

The above quote demonstrates that the investigators perceived Amri along the lines of the organizational differentiation between general and politically motivated crime. Observing Amri by means of this distinction enacted him as a borderline case between both categories. The uncertainty about his intentions, reflected in this borderline categorization, was not neutralized by the investigations:

[…] the accusation could not be corroborated in the course of the surveillance, i.e. either we did not hear everything, or we heard it incorrectly. At no point could it be established that he had prepared an act of violence against the state (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 656).

At the time of the inconclusive investigations and the investigators ambivalence towards the right categorization of Amri, the Berlin police was responsible for

[…] 74 dangerous persons [in 2016]. Of those, I would say half were still in Berlin, some were in custody, some were abroad. […] let’s leave it at 35 […] These people are all basically dangerous. […] In every meeting, every week, we have to ask: Who shall we prioritize and using what measures? […] I […] need to ask myself first: Who has priority now? (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 642).

In the face of the high case load, the head of the LKA 54 asked himself regarding Amri:

How long do you keep running after a dealer and don’t realize that you have a bunch of other dangerous people here? (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 642).

The statement demonstrates an increasing need to justify prioritizing Amri over other cases as no evidence was found that he was actually planning an attack. Additionally, it shows that the investigators were increasingly willing to perceive Amri’s involvement in general criminal acts, i.e. the sale and consumption of drugs, as a signal that he had given up any terrorist plots.

Consequently, the police concluded that due to his

‘unislamic’ lifestyle, his use of alcohol, cigarettes, pornography, and hard drugs [it appeared] that further observation was no longer reasonable (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 1091).

The quote shows that the dynamics reconstructed so far culminated in the usage of a heuristic presupposing that the commission of general and politically motivated crime were contradictory to each other. Operationalizing the categories of the organizational differentiation, the heuristic compensated for the lack of information about Amri’s actual plans, and thereby absorbed any residual uncertainty. Paradoxically, using this heuristic rested on conditions the organization itself created in enacting Amri as a borderline case.

While the resource intensive observations were ended completely, the surveillance of Amri’s communication remained in effect, albeit with reduced intensity (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 648f.). In August 2016, the district attorney ordered LKA 54 to refer the case to the drug department now considered to be in charge (Deutscher Bundestag 2021, 684), underscoring that disambiguating Amri as a general crime case was less motivated by phenomenological concerns but by resource considerations.

6 Organizational Dynamics of Terrorism Prevention

Terrorism prevention is a fundamentally organized phenomenon in modern societies; however, organizational analysis of the subject is rare. The investigations leading up to the Berlin Christmas market attack provide fertile ground for such an analytical endeavor. In what follows, we present our explanatory model.

The Berlin police investigated Amri amidst a high caseload caused by the coinciding of the refugee movement in 2014 with IS threatening terror attacks in Europe. As Amri was considered a potential terrorist, LKA 54 had invasive investigative means at its disposal, rendering the investigation resource intensive. The resource intensity of the investigation, coupled with the high number of cases, set in motion a dynamic in which the advancing investigations increased the need to justify their continuation unless evidence for Amri’s intensions was found. This dynamic was rooted in the organization itself and effectively functioned as a stopping rule because it created incentives to end the investigations and thereby to free up resources.

Despite their resource intensity, the investigative routines only generated selective information about Amri’s behavior due to their bounded rationality. Consequently, they did not absorb the uncertainty about his goals. Amri’s drug-related crimes added to the resulting uncertainty, as the investigators perceived them through the lens of the organizational differentiation between general and politically motivated crime. Thus, Amri became a borderline case to whom both categories might possibly apply. In the face of the inconclusive yet resource-heavy investigations, the investigators’ tolerance for Amri’s ambiguity decreased, while their willingness to disambiguate the case increased. This dynamic culminated in the investigators harnessing a heuristic operationalizing the organizational structure to neutralize their uncertainty about how to evaluate the case. This compensatory heuristic (Gigerenzer, Reb, and Luan 2022) assumed that planning a religiously motivated attack and drug-related criminal activities preclude each other. Its use was the result of increasing pressure to justify further resource investments the investigators were unable to offset with evidence of the planning of an attack. Hence, the heuristic disambiguation of Amri was not motivated by phenomenological considerations but was an expression of organizational self-reference (Luhmann 1995).

Case study results are generalizable to other cases if they can theorize their results to transferable propositions (Yin 2018). Our results allow us to formulate three such propositions.

Our first and most general proposition is that investigative routines to prevent terrorism generate a unique organizational dynamic, producing increasing burdens of justification due to their resource intensity. This dynamic is only stopped when concrete evidence for the planning of an attack is found, incentivizing closing the investigations when such evidence is lacking.

Our second proposition takes inspiration from Herbert Simon’s scissor analogy (1990) which posits that behavior “is shaped by a scissors whose two blades are the structure of task environments and the computational capabilities of the actor” (Simon 1990, 7). For our case, Simon’s scissor analogy is a reminder that to explain organizational actions, we have to account for both system and task environment. We take up this advice by questioning whether the organizational dynamic observed in our case is specific to a certain task environment, lone actors, or also applies to terrorist groups and organizations. We argue that this dynamic is particularly prevalent in the case of lone actors. While terrorist groups and organizations must make trade-offs between secrecy and operational security (Volders 2021), lone actors generate less opportunities for the police to find evidence corroborating concrete planning as they usually prepare their attacks in more seclusion (Lindekilde, Malthaner, and O’Connor 2019). As we argue below, the tendency of lone actors to leak their plans exacerbates the problem and creates another challenge. Furthermore, as police perception is structured by organizational differentiation and lone actors tend to engage in nonpolitical crimes (Kenyon, Baker-Beall, and Binder 2021), we assume that police typically perceive them as borderline cases. With this in mind, we hypothesize that under conditions of resource scarcity and lack of evidence, this further incentivizes stopping investigations.

Our third proposition derives from the observation that lone actors, like Amri, often show a time lag between announcing and committing an attack, while, unlike Amri, most individuals proclaiming plans for a terrorist attack never follow through. This leads us to suggest that police organizations face an exploration dilemma (March 1991) when investigating potential lone actors. By exploration dilemma, we refer to the dilemma in exploring new ideas that “what is good in the long run is not always good in the short run” (March 1991, 73). For that reason, organizations are structurally inclined to discard promising ideas too early. Similarly, as investigations into both individuals actually committing attacks and those just proclaiming intentions to do so will often initially produce negative feedback, police organizations are vulnerable to the identified dynamic incentivizing closing investigations too early. We further suggest that the longer the period between the announcement of an attack and its perpetration, the more probable it becomes that organizational self-reference (Luhmann 1995) in the gestalt of case-ecology driven resource pressure encourages stopping investigations in favor of other cases.

7 Discussion

This article aims to analyze organizational dynamics in terrorism prevention and presents the inner workings of police organizations as a crucial analytical level for understanding terrorism prevention. The results of our study enable us to make several contributions to the existing literature.

Our first contribution is to the sociology of the police. Heeding the call for more organizational analyses of terrorism (James 2011), we add to this literature by presenting an in-depth study of terrorism prevention investigations. By examining investigations from the perspective of organizational sociology, we provide a new angle to a literature mainly concerned with how stable factors such as the characteristics of a crime impact its clearance (Brodeur 2010) by demonstrating how organizational dynamics bear upon investigations.

Our second contribution is to have outlined a theoretical model accounting for the dynamics of police investigations, emphasizing interactions between case ecology, organizational structure, and bounded rational investigative routines as relevant factors. Thereby, we underscore the formal organization as a crucial level (see Du Gay 2020) for research on terrorism prevention. This line of reasoning challenges the common understanding that terrorism prevention primarily depends on legal restrictions and budgetary decisions. Regarding the former, we have shown that the investigations did not suffer from restrictions as the police had comprehensive legal means at their disposal. Regarding the latter, we argue that while more resources probably would have slowed down the process leading to closing the investigations, the general dynamic would have occurred anyway as police organizations are always systems with bounded resources. Further, as our analysis indicates, fully comprehensive investigations require resources to a degree unrealistic to ever be accorded to the police in democratic societies.

Our third contribution pertains to research on lone actors. The literature shows that lone actors care only a little for their operational safety, are known to divulge their intentions “months or even years ahead of the attack” (Schuurman et al. 2019, 772), remain in contact with radical milieus (Hewitt 2014; Schuurman et al. 2019), and often engage in criminal activity (Kenyon, Baker-Beall, and Binder 2021, 7). Reasonably, all of these factors are theorized to make them vulnerable to police detection and thus to prevention efforts (Kenyon, Baker-Beall, and Binder 2021, 20). Our findings add a vital organizational perspective to this theorizing by showing that even if these factors are present, which was the case for Amri, organizationally, lone actors may still present an ill-structured problem (Simon 1973) at the margins of reliability (Perrow 1984) because of the organizational dynamics identified above.

Some authors argue that the recent development of elaborate threat assessment tools has the potential to prevent lone actor attacks (Kenyon, Baker-Beall, and Binder 2021). Our perspective adds to this discussion as it allows us point out that the “large numbers of false positives” (Clemmow et al. 2022, 573) these tools produce, translate into a higher caseload, risking abetting the dynamic observed in the investigations against Amri. More pointedly, with regard to our case, detecting Amri’s intentions was not the issue for the police but, rather, it was deciding how to weigh his announcements against similar cases with no concrete evidence, an increasing need for justifications, and bounded resources. To put it succinctly, threat assessment is organizationally embedded and thus requires attention to be paid to organizations.

8 Conclusions

It is a cliché that not all terrorist attacks can be prevented. Yet, rarely do studies elaborate on the reasons why attacks are not prevented. The present study addressed this gap.

Our analysis yielded three theoretical propositions. We theorized that the organizational dynamics this case study has revealed also characterize other investigations. Further, we suggested that the dynamics prevalent in our case are particular to lone actors and proposed that investigations into lone actors are characterized by an exploration dilemma. Future research should test these arguments with other cases to broaden the empirical basis of organizational perspectives of terrorism prevention.

We remind readers that our study is not without limitations. Its main limitation is that we analyzed our case through the filter of data collected by an inquiry commission. While we are confident that our reasoning is thorough as it is based on robust and empirically saturated categories, we cannot preclude the possibility that the data at our disposal do not contain some relevant aspects due to classification or political bias. Nor can we exclude the possibility that the inquiry commission ignored data relevant for organizational research but unknown to us. On balance, despite our efforts to validate our data via multiple sources and field informants, we must acknowledge that we lacked control of the data collection process.

In conclusion, this study explained the dynamics underlying the premature closing of investigations into an individual threatening to perpetrate a terror attack. We reveal how investigative routines generate a self-referential temporal horizon of increasing urgency to either find corroborating evidence or free resources while we also indicated that this self-referential temporal horizon is decoupled from the attacker’s contingent timeline, which is most likely influenced by environmental opportunities (Marchment and Gill 2019). We hope our organizational perspective on terrorism prevention inspires further studies on the subject in the future.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. or The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Asal, V., and R. K. Rethemeyer. 2008. “The Nature of the Beast: Organizational Structures and the Lethality of Terrorist Attacks.” The Journal of Politics 70 (2): 437–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608080419.Search in Google Scholar

BAMF. 2016. Migrationsbericht 2015: Zentrale Ergebnisse. Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Forschung/Migrationsberichte/migrationsbericht-2015-zentrale-ergebnisse.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=17 (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Bayley, D. H., and D. Weisburd. 2011. “Cops and Spooks: The Role of Police in Counterterrorism.” In To Protect and to Serve: Policing in an Age of Terrorism, edited by D. Weisburd, T. Feucht, I. Hakimi, L. Mock, and S. Perry, 81–99. New York: Springer New York.10.1007/978-0-387-73685-3_4Search in Google Scholar

BMI. 2017. Behördenhandeln um die Person des Attentäters vom Breitscheidplatz Anis AMRI: Stand Februar 2017. Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/themen/sicherheit/chronologie-amri.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Boyle, M. J. 2019. “The Military Approach to Counterterrorism.” In Routledge Handbook of Terrorism and Counterterrorism, edited by A. Silke, 384–94. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315744636-33Search in Google Scholar

Brodeur, J.-P. 2010. The Policing Web. Studies in Crime and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199740598.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Brown, A. D. 2003. “Authoritative Sensemaking in a Public Inquiry Report.” Organization Studies 25 (1): 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604038182.Search in Google Scholar

Bundesministerium des Inneren. 2016. Verfassungsschutzbericht 2015. Bundesministerium des Inneren. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/themen/sicherheit/vsb-2015.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4 (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Bye, R. J., P. Almklov, S. Antonsen, O. M. Nyheim, A. L. Aalberg, and S. O. Johnsen. 2019. “The Institutional Context of Crisis: A Study of the Police Response During the 22 July Terror Attacks in Norway.” Safety Science 111: 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

Clemmow, C., P. Gill, N. Bouhana, J. Silver, and J. Horgan. 2022. “Disaggregating Lone-Actor Grievance-Fuelled Violence: Comparing Lone-Actor Terrorists and Mass Murderers.” Terrorism and Political Violence 34 (3): 558–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1718661.Search in Google Scholar

Clutterbuck, L. 2019. “Policing in Counterterrorism.” In Routledge Handbook of Terrorism and Counterterrorism, edited by A. Silke, 375–83. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315744636-32Search in Google Scholar

Cornelissen, J. P., S. Mantere, and E. Vaara. 2014. “The Contraction of Meaning: The Combined Effect of Communication, Emotions, and Materiality on Sensemaking in the Stockwell Shooting.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (5): 699–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12073.Search in Google Scholar

Coutu, D. 2002. “How Resilience Works.” Harvard Business Review 80 (5): 46–50.Search in Google Scholar

Crenshaw, M. 2014. “Terrorism Research: The Record.” International Interactions 40 (4): 556–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2014.902817.Search in Google Scholar

Deutscher Bundestag. 2021. Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des 1. Untersuchungsausschusses der 19. Wahlperiode gemäß Artikel 44 des Grundgesetzes: Drucksache 19/30800. Endgültige Fassung. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/308/1930800.pdf (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Du Gay, P. 2020. “Disappearing ‘Formal Organization’: How Organization Studies Dissolved its ‘Core Object’, and What Follows from This.” Current Sociology 68 (4): 459–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120907644.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, C. 2016. “With a Little Help from My Friends: An Exploration of the Tactical Use of Single-Actor Terrorism by the Islamic State.” Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6): 41–7.Search in Google Scholar

Faraj, S., and Y. Xiao. 2006. “Coordination in Fast-Response Organizations.” Management Science 52 (8): 1155–69. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0526.Search in Google Scholar

Feldman, M. S., and B. T. Pentland. 2003. “Reconceptualizing Organizational Routines as a Source of Flexibility and Change.” Administrative Science Quarterly 48 (1): 94–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/3556620.Search in Google Scholar

Feldman, M. S., B. T. Pentland, L. D’Adderio, K. Dittrich, C. Rerup, and D. Seidl, eds. 2021. Cambridge Handbook of Routine Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108993340Search in Google Scholar

Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–45, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363.Search in Google Scholar

Frevel, B., and H. Groß. 2016. “„Polizei ist Ländersache !“ – Polizeipolitik unter den Bedingungen des deutschen Föderalismus.” In Die Politik der Bundesländer, edited by A. Hildebrandt, and F. Wolf, 61–86. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.10.1007/978-3-658-08303-8_4Search in Google Scholar

Gigerenzer, G., J. Reb, and S. Luan. 2022. “Smart Heuristics for Individuals, Teams, and Organizations.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 9 (1): 171–98. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-090506.Search in Google Scholar

Gioia, D. 2021. “A Systematic Methodology for Doing Qualitative Research.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 57 (1): 20–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320982715.Search in Google Scholar

Gittell, J. H., K. S. Cameron, S. Lim, and V. Rivas. 2006. “Relationships, Layoffs, and Organizational Resilience.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 42 (3): 300–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886306286466.Search in Google Scholar

Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 2006. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (reprint). New Brunswick, London: Aldine.Search in Google Scholar

Goldman, S. O., and L. Bar. 2020. “The Global Law of Terror Organization Lifespan.” Terrorism and Political Violence 32 (8): 1636–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1498787.Search in Google Scholar

Grey, C. 2014. “An Organizational Culture of Secrecy: The Case of Bletchley Park.” Management & Organizational History 9 (1): 107–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2013.876317.Search in Google Scholar

Hepfer, M., and T. B. Lawrence. 2022. “The Heterogeneity of Organizational Resilience: Exploring Functional, Operational and Strategic Resilience.” Organization Theory 3 (1): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877221074701.Search in Google Scholar

Herbert, U., and J. Schönhagen. 2020. “Vor dem 5. September: Die „Flüchtlingskrise“ 2015 im historischen Kontext.” Aus Politik Und Zeitgeschichte 70 (30–32): 27–36.Search in Google Scholar

Hewitt, C. 2014. “Law Enforcement Tactics and Their Effectiveness in Dealing With American Terrorism: Organizations, Autonomous Cells, and Lone Wolves.” Terrorism and Political Violence 26 (1): 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.849913.Search in Google Scholar

James, K. 2011. “The Organizational Science of Disaster/Terrorism Prevention and Response: Theory-Building Toward the Future of the Field.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 32 (7): 1013–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.782.Search in Google Scholar

Jamieson, A. 2005. “The Use of Terrorism by Organized Crime.” In Root Causes of Terrorism: Myths, Reality, and Ways Forward, edited by T. Bjørgo, 164–77. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203337653_chapter_13Search in Google Scholar

Jobard, F., and J. de Maillard. 2016. Sociologie de la Police. Paris: Armand Colin.10.3917/arco.jobar.2015.01Search in Google Scholar

Joseph, J., and V. Gaba. 2020. “Organizational Structure, Information Processing, and Decision-Making: A Retrospective and Road Map for Research.” Academy of Management Annals 14 (1): 267–2. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0103.Search in Google Scholar

Jost, B. 2017. Abschlussbericht des Sonderbeauftragten des Senats für die Aufklärung des Handelns der Berliner Behörden im Fall AMRI. Der Sonderbeauftragte des Senats von Berlin. https://www.berlin.de/sen/inneres/presse/weitere-informationen/artikel.638875.php (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Kent, D. 2019. “Giving Meaning to Everyday Work After Terrorism.” Organization Studies 40 (7): 975–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618765582.Search in Google Scholar

Kenyon, J., C. Baker-Beall, and J. Binder. 2021. “Lone-Actor Terrorism – A Systematic Literature Review.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2021.1892635.Search in Google Scholar

Kilberg, J. 2019. “Terrorist Group Structures.” In Routledge Handbook of Terrorism and Counterterrorism, edited by A. Silke, 165–73. London, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315744636-14Search in Google Scholar

Klinger, D. A. 1997. “Negotiating Order in Patrol Work: An Ecological Theory of Police Response to Deviance.” Criminology 35 (2): 277–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1997.tb00877.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kremser, W., B. T. Pentland, and S. Brunswicker. 2019. “Interdependence in and Between Routines: A Performative Perspective.” In Research in the Sociology of Organizations: Volume 61. Routine Dynamics in Action: Replication and Transformation, edited by M. S. Feldman, L. D’Adderio, K. Dittrich, and P. Jarzabkowski, 79–98. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.10.1108/S0733-558X20190000061005Search in Google Scholar

Kretschmer, B. 2017. Wissenschaftliche Analyse und Bewertung im Fall Anis Amri. Land NRW. https://www.land.nrw/sites/default/files/asset/document/unabhaengige_wissenschaftliche_analyse_und_bewertung_im_fall_anis_amri_0.pdf (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen. 2022. Schlussbericht des Parlamentarischen Untersuchungsausschusses I („Fall Amri“): Drucksache 17/16890. Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/Dokumentenservice/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument/MMD17-16890.pdf (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Langley, A., and C. Abdallah. 2011. “Templates and Turns in Qualitative Studies of Strategy and Management.” In Research Methodology in Strategy and Management. Building Methodological Bridges, Vol. 6, edited by D. D. Bergh, and D. J. Ketchen, 106–40. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.10.1108/S1479-8387(2011)0000006007Search in Google Scholar

Lindekilde, L., S. Malthaner, and F. O’Connor. 2019. “Peripheral and Embedded: Relational Patterns of Lone-Actor Terrorist Radicalization.” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 12 (1): 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2018.1551557.Search in Google Scholar

Luhmann, N. 1995. Social Systems. Translated by John Bednarz Jr. with Dirk Baecker. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lum, C., M. Haberfeld, G. Fachner, and C. Lieberman. 2011. “Police Activities to Counter Terrorism: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” In To Protect and to Serve: Policing in an Age of Terrorism, edited by D. Weisburd, T. Feucht, I. Hakimi, L. Mock, and S. Perry, 101–41. New York: Springer New York.10.1007/978-0-387-73685-3_5Search in Google Scholar

March, J. G. 1991. ““Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning.” Special Issue: Organizational Learning: Papers in Honor of (and by) James G. March.” Organization Science 2 (1): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71.Search in Google Scholar

March, J. G., and J. P. Olsen, eds. 1976. Ambiguity and Choice in Organizations. Bergen: Universitetsforlaget.Search in Google Scholar

Marchment, Z., and P. Gill. 2019. “Terrorists are Just Another Type of Criminal.” In Routledge Handbook of Crime Science, edited by R. Wortley, A. Sidebottom, N. Tilley, and G. Laylock, 233–51. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203431405-18Search in Google Scholar

Mayntz, R. 2004. Organizational Forms of Terrorism: Hierarchy, Network, or a Type sui generis? MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 04/4. Cologne. https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_1234217_3/component/file_1234215/content (accessed May 10, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Monjardet, D. 1996. Ce que fait la police: Sociologie de la force publique. Paris: La Découverte.10.3917/dec.monja.1996.01Search in Google Scholar

Newburn, T. 2022. “The Inevitable Fallibility of Policing.” Policing and Society 32 (3): 434–50. https://doi.org/10.21428/cb6ab371.1bf31b04.Search in Google Scholar

Perrow, C. 1984. Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies. New York: Basic Books.Search in Google Scholar

Perrow, C. 2014. Complex Organizations: A Critical Essay, 3rd ed. Brattleboro: Echo Point Books & Media.Search in Google Scholar

Piazza, J. A., and M. J. Soules. 2021. “Terror After the Caliphate: The Effect of ISIS Loss of Control Over Population Centers on Patterns of Global Terrorism.” Security Studies 30 (1): 107–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885729.Search in Google Scholar

Price, B. C. 2012. “Targeting Top Terrorists: How Leadership Decapitation Contributes to Counterterrorism.” International Security 36 (4): 9–46. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00075.Search in Google Scholar

Puttonen, R., and F. Romiti. 2022. “The Linkages Between Organized Crime and Terrorism.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 45 (5–6): 331–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1678871.Search in Google Scholar

Quinn, R. W., and M. C. Worline. 2008. “Enabling Courageous Collective Action: Conversations from United Airlines Flight 93.” Organization Science 19 (4): 497–16. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0331.Search in Google Scholar

Randol, B. M. 2012. “The Organizational Correlates of Terrorism Response Preparedness in Local Police Departments.” Criminal Justice Policy Review 23 (3): 304–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403411400729.Search in Google Scholar

Schakel, J.-K., P. C. van Fenema, and S. Faraj. 2016. “Shots Fired! Switching Between Practices in Police Work.” Organization Science 27 (2): 391–10. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1048.Search in Google Scholar

Schoeneborn, D., and A. G. Scherer. 2012. “Clandestine Organizations, al Qaeda, and the Paradox of (In)Visibility: A Response to Stohl and Stohl.” Organization Studies 33 (7): 963–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612448031.Search in Google Scholar

Schuurman, B., L. Lindekilde, S. Malthaner, F. O’Connor, P. Gill, and N. Bouhana. 2019. “End of the Lone Wolf: The Typology that Should Not Have Been.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42 (8): 771–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2017.1419554.Search in Google Scholar

Silke, A., ed. 2019a. Routledge Handbook of Terrorism and Counterterrorism. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315744636-6Search in Google Scholar

Silke, A. 2019b. “The Study of Terrorism and Counterterrorism.” In Routledge Handbook of Terrorism and Counterterrorism, edited by A. Silke, 1–10. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315744636-1Search in Google Scholar

Simmel, G. 1906. “The Sociology of Secrets and of Secret Societies.” American Journal of Sociology 11 (4): 441–98. https://doi.org/10.1086/211418.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, H. A. 1949. Administrative Behavior. New York: The Macmillan Company.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, H. A. 1973. “The Structure of Ill Structured Problems.” Artificial Intelligence 4 (3–4): 181–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-3702(73)90011-8.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, H. A. 1979. “Rational Decision Making in Business Organizations.” The American Economic Review 69 (4): 493–13.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, H. A. 1981. The Sciences of the Artificial, 2nd ed. Cambridge: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Simon, H. A. 1990. “Invariants of Human Behavior.” Annual Review of Psychology 41: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.000245.Search in Google Scholar

Strauss, A. L., and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Sullivan-Taylor, B., and D. C. Wilson. 2009. “Managing the Threat of Terrorism in British Travel and Leisure Organizations.” Organization Studies 30 (2–3): 251–76, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840608101480.Search in Google Scholar

Sutcliffe, K. M., and K. E. Weick. 2008. “Information Overload Revisited.” In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Decision Making, edited by W. H. Starbuck, and C. P. Hodgkinson, 56–75. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199290468.003.0003Search in Google Scholar

Torres-Soriano, M. R. 2021. “How do Terrorists Choose Their Targets for an Attack? The View from Inside an Independent Cell.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33 (7): 1363–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1613983.Search in Google Scholar

Vaughan, D. 2004. “Theorizing Disaster.” Ethnography 315–47, https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138104045659.Search in Google Scholar

Volders, B. 2021. “Building the Bomb: A Further Exploration of an Organizational Approach to Nuclear Terrorism.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33 (5): 1012–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1598387.Search in Google Scholar

Warner, J., E. Chapin, and Q. Sorenson. 2021. “Bombing It: The Meaning and Sources of Suicide Bombing Failure.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2021.1956062.Search in Google Scholar

Wohlstetter, R. 1962. Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Stanford: Stanford University Press.10.1515/9781503620698Search in Google Scholar

Yin, R. K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- A Platform for Debating the Role of Organization in, for, and Throughout Society

- Research Articles

- Relational Agency as a Dialectic of Belonging and Not Belonging within the Social Ecology of Plantation Life in Sri Lanka

- Exploring Terrorism Prevention: An Organizational Perspective on Police Investigations

- Organizing Expertise During a Crisis. France and Sweden in the Fight Against Covid-19

- Beacon of Organizational Sociology

- Organisation as Reflexive Structuration

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- A Platform for Debating the Role of Organization in, for, and Throughout Society

- Research Articles

- Relational Agency as a Dialectic of Belonging and Not Belonging within the Social Ecology of Plantation Life in Sri Lanka

- Exploring Terrorism Prevention: An Organizational Perspective on Police Investigations

- Organizing Expertise During a Crisis. France and Sweden in the Fight Against Covid-19

- Beacon of Organizational Sociology

- Organisation as Reflexive Structuration