Abstract

Context

Influenza-related hospitalization and mortality disproportionately affects the Hispanic population in the United States. Among other medical conditions in addition to influenza, Spanish-preferring Hispanics may be more affected than those who speak English.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to compare seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rates between Spanish-and English-preferring Hispanic US adults from 2017 to 2020.

Methods

For this cross-sectional study, we extracted data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) from the 2017 through 2020 cycles. We calculated the population prevalence of individuals getting influenza vaccines per year, and among subpopulations based on language spoken, age, and sex. We then utilized chi-squared tests of independence to discover possible associations between these subpopulations per year. An alpha level of 0.05 was utilized in this study. Respondents were included if they identified as Hispanic, responded to questions regarding influenza vaccine uptake, and were grouped by the language of the survey returned, age, and sex.

Results

Our results show that self-identified Hispanic individuals who were English-preferring had greater seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rates in the latter 2 years of our study for both sexes in the younger age group. Hispanic individuals over the age of 65 years (n=11,328) were much more likely to have received an influenza vaccine compared to younger individuals (n=34,109). In 2018, Spanish-preferring women over age 65 years (n=677) were more likely to have received a vaccine over English-preferring women (n=772).

Conclusions

Our findings showed that disparities exist between English- and Spanish-preferring Hispanic individuals and age groups. Language barriers may play a role in receiving influenza vaccines. The incorporation of medical translators may assist in reducing these disparities in influenza-related healthcare expenses, overall morbidity, and mortality.

Between 1999 and 2019, influenza and pneumonia was the ninth leading cause of death in the United States [1], with an estimated annual burden of $11.2 billion [2]. Further, individuals who are Black, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Hispanic experience disparate rates of hospitalization due to influenza among all age groups compared to individuals who are White [3]. As a result, influenza vaccine uptake rates among minority groups has been a focus point for many healthcare providers; however, there is a consistently lower influenza vaccine uptake among Black individuals who are 65+ years of age and Hispanic individuals who are 65+ years of age [4]. A previous study linked this disparity in vaccine uptake to differences in medical care [5].

Many sociological factors affect patient care, one being communication. Language barriers can be a routine challenge that healthcare workers face because sufficient translation services are typically not readily available. This further perpetuates a decline in empathy expressed by healthcare providers [6]. These limitations in discourse between patient and provider may result in less-than-optimal mental and physical health outcomes [7]. For example, language barriers may impact the likelihood of obtaining an accurate medical history from patients [8], which may affect a clinical diagnosis or sufficient examination. Link et al. [9] posited language barriers as a potential reasoning for the disparities in influenza vaccine uptake between individuals who identified as White (66.0%; n=12,096) and those who identified as Hispanic (52.5%; n=336) between 2004 and 2005.

Pearson et al. [5] found that Spanish-preferring Hispanics, aged 65 or older, were significantly less likely to have received the influenza vaccine (44.6–46.0%; n=5,854) compared to English-preferring Hispanics (55.8–63.4%; n=6,550) from 2005 to 2007. A study in 2011 demonstrated disparities among minorities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to care regarding the H1N1 strain of influenza [10]. Following this study, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prioritized increasing access to and uptake of the seasonal influenza vaccine among elderly and minority groups [11]. Given these initiatives, our primary objective was to reassess influenza vaccine uptake among English- and Spanish-preferring Hispanic US adults from 2017 to 2020 utilizing the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Our secondary objective was to assess vaccine trends by age and sex.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis utilizing data from the 2017 through 2020 BRFSS cycles. BRFSS is a nationally representative, telephone-based survey, administered annually by the CDC and state health departments in each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and select US territories. BRFSS extracts health behavior and disease conditions from all noninstitutionalized individuals. To estimate population estimates, BRFSS incorporates complex sampling design and utilizes ranking weights to account for survey noncoverage, nonresponse, and the probability of being sampled given geographic location, age, race, and sex [12].

Participants included in our study self-reported to be of Hispanic ethnicity and responded to the question “Are you Hispanic, Latino/a, or Spanish origin? ” as either “Yes” or “No.” Responses of “unsure” or “refused” were excluded from analysis. Individuals who answered “Yes” or “No” to receiving an influenza vaccine were included in our study, and those who refused to respond or answered “unsure” were excluded. Further, the participant’s language was determined by the version of the BRFSS survey administered—the English or Spanish version—as has been utilized in previous studies [13]. BRFSS provides a variable of sex (male or female) and a calculated age variable with categories of below 65 and equal to or greater than 65 years. Therefore, respondents met the inclusion criteria if they were Hispanic, aged 18 years or greater, and completed the survey in either English or Spanish.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the population prevalence of individuals getting influenza vaccines per year, and among subpopulations based on the language spoken, age, and sex. We then utilized chi-squared tests of independence to discover possible associations between these subpopulations per year. An alpha level of 0.05 was utilized in this study. Analyses were conducted utilizing Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). We submitted this for ethics review to an institutional review board, which deemed it nonhuman subjects research. All states, including the territories of Guam and Puerto Rico, were utilized in our analysis. No responses were provided for language preference in New Jersey in 2019; however, the data were available from this state for 2017, 2018, and 2020.

Results

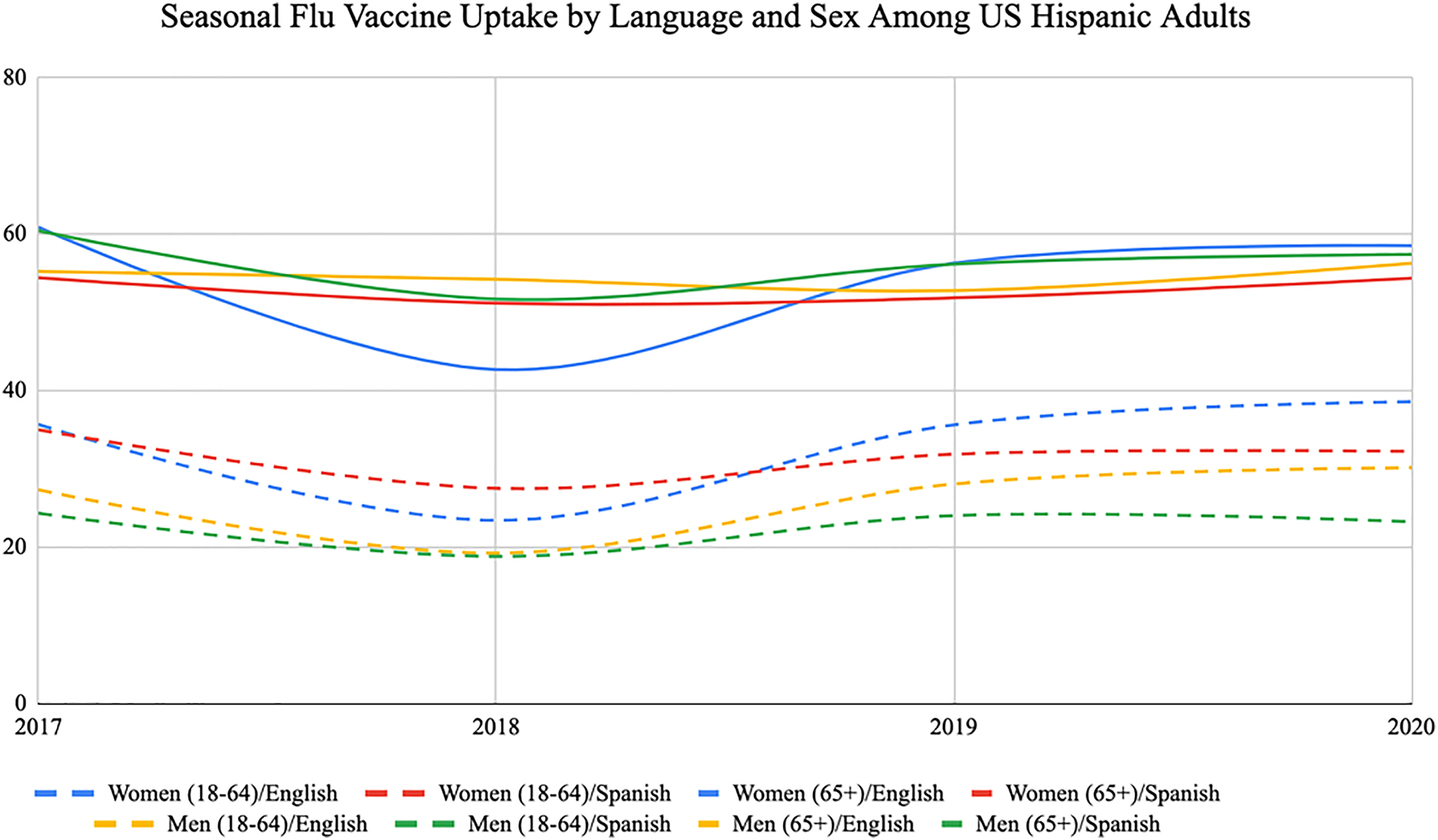

Annually, the Hispanic population included in the study was predominantly aged 18–64—between 88.4% (n=33,050) and 89.4% (n=32,625; Table 1). The lowest percentage of Hispanic US adults of all ages who received influenza shots was in 2018 (25.3%; n=10,036) and the highest was in 2020 at (34.8%; n=12,496). These years (2018 and 2020) also represent the lowest and highest rates of vaccine uptake among the younger age groups (Figure 1). Lastly, Hispanic US adults ages 65 years and over had the highest percentage of influenza shots received in 2017 (57.8%; n=2,865), while 2018 had the lowest (50.1%; n=2,546). Rates of seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among Hispanic US adults stratified by language, sex, and age are shown in Table 2. In 2018, 2019, and 2020, there was a statistically significant difference in uptake in English-preferring women when compared to Spanish-preferring women ages 18to 64 (p=0.002, p=0.011, and p<0.001, respectively). Higher influenza vaccine uptake of Spanish-preferring women ages 18 to 64 was seen only in 2018 (27.5%; n=1919) in comparison to English-preferring women (23.4%; n=2,401). On the contrary, English-preferring women ages 18 to 64 had higher percentages of influenza vaccine uptake in 2019 (35.6%; n=3,040) and 2020 (38.6%; n=3,810) than Spanish-preferring women in 2019 (31.9%; n=2094) and 2020 (32.2%; n=1819). English-preferring men aged 18 to 64 showed higher percentages of influenza vaccine uptake compared to Spanish-preferring men in 2017 (27.3%; n=2,292), 2019 (28.1%; n=2,249), and 2020 (30.2%; n=2,760), each of which were significantly different.

Sample size and population estimates of Hispanic US adults and the percent receiving influenza shots by age group from 2017 to 2020.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Hispanic sample size per year | ||||

|

|

||||

| Sample (n) | 32,625 | 34,727 | 33,050 | 33,509 |

| Population estimate (n) | 36,383,610 | 40,153,960 | 37,675,188 | 41,944,509 |

| % 18–64 | 89.39 | 88.91 | 88.43 | 88.58 |

| % 65+ | 10.61 | 11.09 | 11.57 | 11.42 |

|

|

||||

| All ages | ||||

|

|

||||

| Sample (n) | 11,617 | 10,036 | 11,662 | 12,496 |

| Population estimate (n) | 12,235,968 | 10,155,090 | 12,487,268 | 14,609,093 |

| Percent | 33.63 | 25.29 | 33.14 | 34.83 |

|

|

||||

| 18–64 | ||||

|

|

||||

| Sample (n) | 8,676 | 7,380 | 8,602 | 9,451 |

| Population estimate (n) | 9,968,049 | 7,827,017 | 10,025,403 | 11,804,976 |

| Percent | 30.81 | 22.12 | 30.31 | 32.05 |

|

|

||||

| 65+ | ||||

|

|

||||

| Sample (n) | 2,865 | 2,546 | 2,968 | 2,949 |

| Population estimate (n) | 2,218,539 | 2,211,556 | 2,349,094 | 2,686,785 |

| Percent | 57.75 | 50.11 | 54.27 | 56.6 |

-

Data were extracted from the 2017 to 2020 Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Trends in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake by language and sex among US Hispanic adults. The data were extracted from the 2017 to 2020 Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

Trends in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake by language and sex among Hispanic US adults (weighted percents) from 2017 to 2020.

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | n (%) | Chi-squared, p | n (%) | Chi-squared, p | n (%) | Chi-squared, p | n (%) | Chi-squared, p |

| Women (18–64)/English | 3,141 (35.68) | 0.20, 0.66 | 2,401 (23.44) | 9.98, 0.002 | 3,040 (35.63) | 6.33, 0.011 | 3,810 (38.59) | 10.51, 0.001 |

| Women (18–64)/Spanish | 2,041 (35.00) | 1,919 (27.52) | 2,094 (31.87) | 1,819 (32.23) | ||||

| Women (65+)/English | 956 (60.87) | 3.10, 0.08 | 772 (42.69) | 6.77, 0.009 | 924 (56.28) | 1.73, 0.19 | 1,093 (58.52) | 1.02, 0.31 |

| Women (65+)/Spanish | 804 (54.42) | 677 (51.17) | 834 (51.84) | 639 (54.36) | ||||

| Men (18–64)/English | 2,292 (27.33) | 4.12, 0.04 | 1921 (19.24) | 0.12, 0.73 | 2,249 (28.07) | 7.58, 0.006 | 2,760 (30.15) | 14.98, <0.001 |

| Men (18–64)/Spanish | 1,185 (24.34) | 1,120 (18.82) | 1,202 (24.03) | 1,062 (23.25) | ||||

| Men (65+)/English | 588 (55.23) | 1.31, 0.25 | 620 (54.22) | 0.41, 0.52 | 645 (52.78) | 0.67, 0.41 | 743 (56.27) | 0.04, 0.85 |

| Men (65+)/Spanish | 509 (60.41) | 468 (51.68) | 557 (56.16) | 474 (57.40) | ||||

| Sample size (sample; population estimate), for women <65 | 14,681; 16,149,057 | 15,308; 17,460,425 | 14,554; 16,584,528 | 15,052; 18,461,370 | ||||

| Sample size (sample; population estimate), for women 65+ | 3,409; 2,119,904 | 3,133; 2,384,175 | 3,394; 2,333,927 | 3,011; 2,550,912 | ||||

| Sample size (sample; population estimate), for men <65 | 12,233; 15,992,635 | 13,643; 17,868,182 | 12,530; 16,446,740 | 13,054;18,366,196 | ||||

| Sample size (sample; population estimate), for men 65+ | 2,016; 1,701,461 | 2,187; 2,009,908 | 2,271; 1,991,476 | 2,100;2,195,675 | ||||

-

Data were extracted from the 2017 to 2020 Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).

English- and Spanish-preferring women aged 65 and older showed a difference in influenza vaccine uptake only in 2018 (p=0.009), whereas Spanish-preferring women aged 65 years and older had a higher percentage of influenza vaccine uptake (51.2%; n=677) compared to English-preferring women (42.7%; n=772). There was no statistically significant difference for English-and Spanish-preferring men aged 65 and older (Table 2).

Discussion

Overall, we found that Hispanic individuals over the age of 65 were much more likely to have received an influenza vaccine between 2017 and 2020 compared to younger individuals. Our findings show a dip among all groups in 2018, which rebounded among all groups in 2019. In 2020, all groups, with the exception of younger Spanish-preferring Hispanic men, increased vaccine uptake or remained at 2019 levels. Notably, this increase in vaccine uptake corresponded with the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Further, our results show that Hispanic individuals who were English-preferring had greater seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rates in the latter 2 years of our study for both sexes in the younger age group. We also noted that in 2018, older Spanish-preferring women were more likely to be influenza-vaccinated over older English-preferring women. This finding was reversed for the younger age group of women, where Spanish-preferring women had less seasonal influenza vaccine uptake than their English-preferring counterparts.

The literature on seasonal influenza vaccine uptake rates for those who prefer to speak a different language than English is sparse. Compared to results from Link et al. [9], which found influenza vaccine uptake from 2001 through 2005 ranging from 52.7 to 58.3% among Hispanic US adults, we found that vaccine uptake remains similar nearly 15 years later. Conversely, Pearson et al. [5] found that influenza vaccine uptake among older Spanish-preferring Hispanics ranged from 44.5% (n=3,330) to 46.0% (n=5,125). Our more recent findings show that influenza vaccine uptake among Spanish-preferring men and women has increased in the past 15 years—ranging from 51 to 60% of these individuals receiving an influenza shot. Our findings show higher rates of influenza vaccine uptake compared to these earlier studies, which may be attributed to increased public health efforts within Spanish-speaking communities as well as an overall expanded acceptance of influenza vaccines within the American population [14]. Our findings also highlight outcomes based on sex and age, including a younger age group (18–64 years), whereas previous research has mainly focused only on individuals 65+ years without further categorization. Further, recommendations for future research would be to investigate whether certain regions face disproportionate disparity in regard to vaccine uptake, and to possibly compare vaccine uptake among Hispanic population densities.

Barriers related to vaccine uptake, such as the language barrier, have been shown to increase vaccine hesitancy particularly in the younger Hispanic population, and this may be partly due to marginal Hispanic representation in the medical field and studies [15]. Hernandez et al. [16] found that vaccine information was seen as more trustworthy by college-aged Hispanic women when the information was administered by a race-concordant medical professional. Increasing Hispanic representation and media coverage of Hispanic healthcare professionals disseminating research information and the experiences of Hispanic vaccine recipients may lead to greater vaccine trust in the Hispanic community [15], especially among Spanish-preferring younger men. Overcoming the language barrier is a necessary responsibility to promote vaccine uptake in order to help reduce morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.

Interventions to bridge the language gap would not only improve healthcare but also could help provide economic relief from influenza-associated costs. A study by Molinari et al. [17] found that an estimated 610,660 years’ worth of life was lost due to influenza in 2003, with an additional loss of $16.3 billion due to influenza-related expenses. Another study found that vaccinating children, the elderly, at-risk patients, and pregnant women could prevent hospitalizations and has proven to be a cost-saving strategy for influenza-related expenses [18]. This reveals the importance of increasing seasonal influenza vaccine uptake not only for decreasing mortality and improving healthcare, but also for mediating costs and alleviating economic expenditures. By reforming healthcare complications related to the language barrier, we believe that the rate of influenza vaccine uptake will improve, leading to an ultimate reduction in mortality and economic grief imposed by influenza annually.

Language barriers have been shown to impede access to care and result in suboptimal relationships between providers and clients [19]. Therefore, it is important to address the language barrier in order to promote seasonal influenza vaccine uptake by providing access to Spanish translated medical resources and medically trained translators or interpreters in healthcare settings [20]. The use of professionally trained medical interpreters increases patient satisfaction [21], quality of care, and patient compliance, while decreasing adverse events [22], hospital stays, and readmission rates [23]. Incorporating linguistic training in the education of medical and healthcare disciplines would likely reduce disparities in influenza vaccine uptake [20].

Strengths and limitations

Interpretation of these estimates gives a timely view of the most recent trends of influenza vaccine uptake amongst Spanish- and English-preferring Hispanic adults. As the Hispanic population continues to grow, this analysis contributes to informing the medical community on a large minority group living in the United States. However, several limitations produced by the BRFSS estimates should be noted. First, the weighting adjustments may not eliminate all potential bias for incomplete sample frames such as excluding households with no telephones due to the nature of the BRFSS survey data collection process, as well as survey response bias. Additionally, recall bias may present recall errors in influenza vaccination status among respondents. Finally, response and social desirability bias may have imputed error into our results.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that following a dip in 2018, influenza vaccine uptake among Hispanic individuals in the United States increased through 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic. However, disparities exist between English- and Spanish-preferring Hispanic individuals and age groups by influenza vaccine status. Given these differences, language barriers may play a role in whether specific groups received influenza vaccines. Thus, increased use of medical translators in healthcare settings, incorporation of linguistic medical education courses, and culture-concordant public health messaging are needed to reduce these disparities. In turn, these strategies may reduce influenza-related healthcare expenses, overall morbidity, and mortality.

-

Research funding: None reported.

-

Author contributions: All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; M.H. gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: Dr. Hartwell reports receiving funding from the National Institute for Justice and Health Resources and Services Administration for research unrelated to the current topic.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying cause of death 1999–2019 on CDC WONDER online database, released in 2020. In: Data are from the multiple cause of death files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the vital statistics cooperative program; 2020. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html [Accessed 20 Dec 2021].Search in Google Scholar

2. Putri, WCWS, Muscatello, DJ, Stockwell, MS, Newall, AT. Economic burden of seasonal influenza in the United States. Vaccine 2018;36:3960–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. O’Halloran, AC, Holstein, R, Cummings, C, Daily Kirley, P, Alden, NB, Yousey-Hindes, K, et al.. Rates of Influenza-associated hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital death by race and ethnicity in the United States from 2009 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2121880. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21880.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Okoli, GN, Abou-Setta, AM, Neilson, CJ, Chit, A, Thommes, E, Mahmud, SM. Determinants of seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among the elderly in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2019;5: 2333721419870345. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721419870345.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Pearson, WS, Zhao, G, Ford, ES. An analysis of language as a barrier to receiving influenza vaccinations among an elderly Hispanic population in the United States. Adv Prev Med 2011;2011:298787. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/298787.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Elayyan, M, Rankin, J, Chaarani, MW. Factors affecting empathetic patient care behaviour among medical doctors and nurses: an integrative literature review. East Mediterr Health J 2018;24:311–8. https://doi.org/10.26719/2018.24.3.311.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Diamond, L, Izquierdo, K, Canfield, D, Matsoukas, K, Gany, F. A systematic review of the impact of patient-physician non-English language concordance on quality of care and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1591–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Herbert, BM, Johnson, AE, Paasche-Orlow, MK, Brooks, MM, Magnani, JW. Disparities in reporting a history of cardiovascular disease among adults with limited English proficiency and angina. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2138780. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38780.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Link, MW, Ahluwalia, IB, Euler, GL, Bridges, CB, Chu, SY, Wortley, PM. Racial and ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among adults during the 2004–2005 season. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:571–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwj086.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Quinn, SC, Kumar, S, Freimuth, VS, Musa, D, Casteneda-Angarita, N, Kidwell, K. Racial disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to health care in the US H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Publ Health 2011;101:285–93. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.188029.Search in Google Scholar

11. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Racial and ethnic minority groups. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/disparities-racial-ethnic-minority-groups.html [Accessed 13 Jan 2022].Search in Google Scholar

12. 2019 BRFSS survey data and documentation; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2019.html [Accessed 15 Feb 2022].Search in Google Scholar

13. Suneja, G, Diaz, JA, Roberts, M, Rakowski, W. Reversal of associations between Spanish language use and mammography and pap smear testing. J Immigr Minority Health 2013;15:255–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9694-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Greiner, B, Hartwell, M. Influenza vaccination uptake trends by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States between 2017 and 2020. J Prim Care Community Health 2022;13: 21501319221104917. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319221104917.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Kricorian, K, Turner, K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and beliefs among black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256122. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Hernandez, ND, Daley, EM, Young, L, Kolar, SK, Wheldon, C, Vamos, CA, et al.. HPV vaccine recommendations: does a health care provider’s gender and ethnicity matter to unvaccinated Latina college women? Ethn Health 2019;24:645–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1367761.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Molinari, NAM, Ortega-Sanchez, IR, Messonnier, ML, Thompson, WW, Wortley, PM, Weintraub, E, et al.. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 2007;25:5086–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. D’Angiolella, LS, Lafranconi, A, Cortesi, PA, Rota, S, Cesana, G, Mantovani, LG. Costs and effectiveness of influenza vaccination: a systematic review. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2018;54:49–57.Search in Google Scholar

19. Pandey, M, Maina, RG, Amoyaw, J, Li, Y, Kamrul, R, Michaels, CR, et al.. Impacts of English language proficiency on healthcare access, use, and outcomes among immigrants: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:741. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06750-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Carlson, ES, Barriga, TM, Lobo, D, Garcia, G, Sanchez, D, Fitz, M. Overcoming the language barrier: a novel curriculum for training medical students as volunteer medical interpreters. BMC Med Educ 2022;22:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03081-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Bagchi, AD, Dale, S, Verbitsky-Savitz, N, Andrecheck, S, Zavotsky, K, Eisenstein, R. Examining effectiveness of medical interpreters in emergency departments for Spanish-speaking patients with limited english proficiency: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:248–56.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Flores, G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2005;62:255–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558705275416.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Lindholm, M, Hargraves, JL, Ferguson, WJ, Reed, G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1294–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2041-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Case Report

- Successful buprenorphine transition while overlapping with a full opioid agonist to treat chronic pain: a case report

- General

- Original Article

- How did the dietary habits of patients with chronic medical conditions change during COVID-19?

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Is cadaveric dissection essential in medical education? A qualitative survey comparing pre-and post-COVID-19 anatomy courses

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Commentary

- Advancing care and research for traumatic brain injury: a roadmap

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Concussion-related visual memory and reaction time impairment in college athletes improved after osteopathic manipulative medicine: a randomized clinical trial

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- A narrative review of nine commercial point of care influenza tests: an overview of methods, benefits, and drawbacks to rapid influenza diagnostic testing

- Original Article

- Disparities in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake and language preference among Hispanic US adults: an analysis of the 2017–2020 BRFSS

- Clinical Images

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Leukoderma with perifollicular sparing: a diagnostic clue of cutaneous onchocerciasis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Case Report

- Successful buprenorphine transition while overlapping with a full opioid agonist to treat chronic pain: a case report

- General

- Original Article

- How did the dietary habits of patients with chronic medical conditions change during COVID-19?

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Is cadaveric dissection essential in medical education? A qualitative survey comparing pre-and post-COVID-19 anatomy courses

- Musculoskeletal Medicine and Pain

- Commentary

- Advancing care and research for traumatic brain injury: a roadmap

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Original Article

- Concussion-related visual memory and reaction time impairment in college athletes improved after osteopathic manipulative medicine: a randomized clinical trial

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- A narrative review of nine commercial point of care influenza tests: an overview of methods, benefits, and drawbacks to rapid influenza diagnostic testing

- Original Article

- Disparities in seasonal influenza vaccine uptake and language preference among Hispanic US adults: an analysis of the 2017–2020 BRFSS

- Clinical Images

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Leukoderma with perifollicular sparing: a diagnostic clue of cutaneous onchocerciasis