Abstract

A 57-year-old man who had recurrent respiratory infections due to tobacco use and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was evaluated as an outpatient to discern the etiology. He was followed with a chest X-ray and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan that displayed a left upper lobe cavitary lung abnormality. The lesion was further evaluated with a CT-guided biopsy, and it was identified as a lung abscess. A tissue culture isolated Propionibacterium acnes. We present a rare case of a common skin commensal, P. acnes, that infected the left upper lobe of the lung. We presume that the patient was predisposed to infection secondary to degradation of pulmonary parenchyma by severe bullous emphysema. This destruction created an inflammatory and colonizing space for organisms, even uncommon forms, to flourish. Initially this presentation prompted a differential of pulmonary tuberculosis; however, with further workup, the diagnosis was excluded. This case highlights the potential of P. acnes, an uncommon lung microbe, to lead to a lung abscess in a patient who was otherwise immunocompetent. This case will allow osteopathic clinicians to detect an uncommon microorganism that can potentially cause a pulmonary abscess in a patient with a medical history of severe bullous emphysematous COPD.

Propionibacterium acnes, following the current nomenclature of Cutibacterium acnes, is a gram-positive, non–spore-forming, anaerobic bacillus [1]. It commonly colonizes sebaceous glands and is notable to be a skin commensal [1]. P. acnes is thought to play a role in acne primarily when sebaceous glands are increasing in size during the beginning of puberty [1]. It is a slow-growing bacteria known to grow in culture over 14 days [2, 3]. The organism can survive in vivo and in vitro [3]. P. acnes infects immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals with no preference [1]. It is not typical for a gram-positive anaerobic bacillus, such as P. acnes, to colonize the pulmonary parenchyma. This microbe can also take form as an opportunistic pathogen, when related to infected implants [2], and can cause empyema following invasive chest interventions such as thoracoscopy [3], although this is not common. We conducted a literature review and observed no reported cases of a patient who developed a P. acnes abscess secondary to severe emphysematous chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), accompanied by bullous lung disease. This case exhibits uncommon colonization and infection of bullous lung by P. acnes in an otherwise immunocompetent adult.

Case description

A 57-year-old white man with a past medical history of severe emphysematous COPD with bullous lung disease and a history of smoking 40 packs of cigarettes per year presented to his local county health department with recurrent respiratory infections and was worked up for an etiology of his symptoms in April 2019. The initial chest X-ray showed cavitary and inflammatory changes involving the left upper lobe of the lungs with biapical bullous emphysema. His local county health department tested three consecutive sputums for acid fast bacilli (AFB) and also performed a skin PPD test. All of the tests were negative; however, the patient persisted with abnormal presentation on the chest X-ray. The patient denies fever, night sweats, hemoptysis, and weight loss.

The patient was referred to pulmonology for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed bronchial breath sounds and intermittent rales in the left upper lobe on chest auscultation. Diffuse expiratory rhonchi were also noted. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and a CT-guided needle core biopsy with a fine needle aspiration were ordered to further investigate the abnormal chest X-ray. The lung biopsy was analyzed by pathology and microbiology. Histopathology revealed mixed chronic inflammation. All tissue cultures were negative for AFB and other infectious granulomatous pathologies as well as fungal etiologies. Only an anaerobic culture of P. acnes was identified. The patient was subsequently prescribed an antibiotic course of doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 21 days. All of his symptoms resolved after receiving treatment. Two months following his treatment, mildly diffuse expiratory rhonchi from his COPD were noted. To confirm abscess resolution, a follow-up chest X-ray was performed, which did not show any residual loculated abscess in the left upper lung.

Investigation and treatment

Initial imaging (chest X-ray) at the patient’s local county health department showed an inflammatory, cavitary lesion in the upper left lobe of the lung. A primary chest CT (Figure 1) revealed a multiloculated abscess in the left apical region of the lung.

Primary CT of the chest displaying a multiloculated abscess in the left apical region of the lung.

Five CT-guided needle core biopsies (Figure 2) were performed, yielding four touch preparation slides that were Papanicolaou-stained. One tissue fragment was submitted for microbiological testing. The remaining tissue fragments from the core sample were preserved in 10% formalin and submitted for embedding in a single cassette. Two fine needle aspirations were obtained under CT guidance, a portion of which was sent to microbiology. The remainder of the needle rinse fluid was concentrated and submitted for embedding in a single cell block. One ThinPrep slide was prepared and Papanicolaou-stained.

CT-guided needle core biopsy.

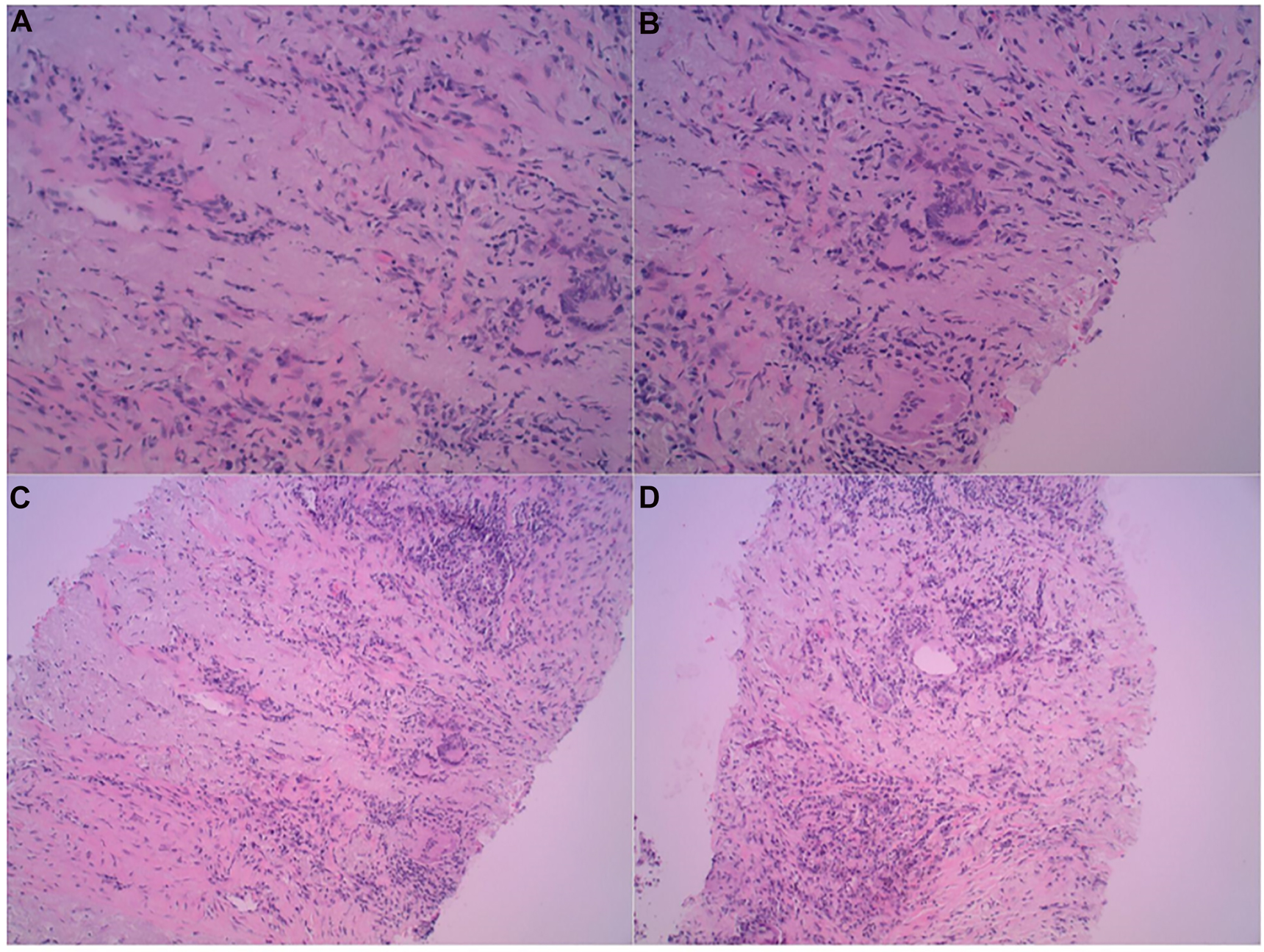

Pathology of the core biopsy identified fibrosis and scarring accompanied by mixed chronic inflammation and focal noncaseating and necrotic sites of granulomatous inflammation. Special stains were negative for AFB and Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver (GMS). Cell block confirmed no evidence of malignancies. Fine needle aspiration confirmed mixed chronic inflammation accompanied by epithelioid histiocytes (Figure 3).

(A–D) Histology slides of needle core biopsies. The slides demonstrate fibrosis and scarring accompanied by mixed chronic inflammation and focal noncaseating and necrotic sites of granulomatous inflammation.

Microbiology reports were negative for all organisms including staphylococcus and streptococcus species, gram negative bacilli, AFB, fungus, fusobacterium, and bacteroides. Anaerobic cultures were positive for P. acnes two weeks later. No other organisms were isolated.

The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 21 days. He was also advised to continue his daily maintenance therapy, which included inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting bronchodilators for his COPD. He was strongly counseled for smoking cessation. The patient provided oral consent to his pulmonologist at the private pulmonary clinic prior to formulating our case study for educational purposes.

Follow-up and outcome

The patient was followed up after treatment was completed. A subsequent chest X-ray (Figure 4) on July 2019 showed resolution of the left upper lobe abscess. A repeat physical examination was remarkable only for mild diffuse expiratory rhonchi secondary to underlying COPD. The patient remained well overall.

X-ray shows resolution of P. acnes lung abscess after completing antibiotic course treatment.

Discussion

P. acnes commonly infiltrates the sebaceous glands, mucosa, and gastrointestinal tract [2]. Because this organism is noted to affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, a patient with advanced pulmonary tissue damage can likely be colonized by P. acnes [1]. Bullous emphysema associated with COPD causes significant parenchymal damage of the lung, so we postulate that the degradation of pulmonary tissue allows a number of pathogens to colonize and infect the lung tissue, and it was P. acnes in our case.

The patient also takes inhaled corticosteroids and has a history of tobacco use. Both of these debilitating factors, along with pulmonary tissue damage from bullous emphysema associated with COPD, may have also increased the chances of infection. Commonly, lung abscesses are caused by aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions with organisms such as gram-negative Bacteroides fragilis, Fusobacterium capsulatum and necrophorum, gram-positive anaerobic Peptostreptococcus, and microaerophilic streptococci [4]. The patient underwent CT-guided needle core biopsies, and the results showed no signs of the microorganisms mentioned. Even the cell block was indicated to be negative for malignancies.

We found only a few cases of P. acnes localized and infecting the pleuro-pulmonary tissue. One case revealed P. acnes leading to an abscess within the pulmonary parenchyma, following a cardiac transplant [1]. The other pulmonary cases involving P. acnes were associated with infected empyemas [3, 5, 6]. The infected empyemas were hypothesized to be likely caused by penetration of the skin postthoracoscopy [3], postthoracentesis [5], and postpneumonectomy [6].

Lawrence et al. [3] described a case of a 75-year-old man with chronic pleural exudative effusions who had undergone a thoracoscopy and had a chest tube for three days. Three weeks later, the patient was infected and diagnosed with a P. acnes empyema and deteriorated quickly. The patient required a decortication. Other cases showed P. acnes colonizing and infecting various extrapulmonary regions such as biofilms on prosthetic joint implants [2], prosthetic cardiac valves postendocarditis [7], and splenic parenchyma [8].

The case study by Veitch et al. [1] presented similar factors such as the microorganism, affected body system, biological sex, and treatment. We chose to compare the two studies (Table 1) due to these similarities. Our case study included a patient with a competent immunity, lung damage caused by COPD, and recurrent respiratory infections; however, the case study by Veitch et al. [1] presented a younger male who was immunocompromised because he was on immunosuppressive medications such as mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine. He had risk factors including restrictive cardiomyopathy, cardiac transplant, and myofibrillar myopathy. The younger male also had no clear clinical symptoms. Both cases presented with pulmonary abscesses that resolved after treatment. The patient in our case was treated with doxycycline 100 mg bid for 21 days, and the patient in Veitch’s case was treated with Co-amoxiclav 625 mg tid for six weeks [1].

Comparison of the patient mentioned within this case study to the next most similar case study found within existing publications.

| Our case | Veitch et al. [1] | |

|---|---|---|

| Location of lung | Upper lobe | Middle lobe/oblique fissure |

| Age (years), sex | 57, man | 26, man |

| Risk factors | COPD/bullous emphysema |

|

|

||

|

||

| Underlying immunocompetence | Competent (not on oral corticosteroids) | Compromised: |

|

||

|

||

| Underlying lung structure | Lung damage from COPD/bullae | |

| Clinical presentation | Recurrent respiratory infections; | Pulmonary symptoms were unremarkable |

| no fevers, night sweats, or weight loss | ||

| Diagnosis | P. acnes pulmonary abscess | P. acnes pulmonary abscess |

| Treatment | Doxycycline | Co-amoxiclav |

| 100 mg bid, 21 days | 625 mg tid, six weeks | |

| Follow-up/prognosis | Patient was free of infection after abscess resolved. No further complications. | Radiological resolution of the abscess. Patient remained well. |

Conclusions

After a literature review, no cases were detected regarding patients developing a pulmonary abscess infected by P. acnes due to parenchymal damage from chronic bullous and emphysematous COPD. We hypothesize that the entry for P. acnes was possible by inhalation after having contact with his own skin, leading to colonization and subsequent infection of the bullous region of the lung. This case should allow clinicians to broaden their differential and avoid the pitfalls of swiftly diagnosing apical cavitary lesions as pulmonary tuberculosis. A broad differential and proper testing will rule out diseases that would otherwise unnecessarily need empiric treatment and provide the patient with an appropriate diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

-

Research funding: None reported.

-

Author contributions: Both authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; both authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; A.A. gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and both authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None reported.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was acquired from the patient.

References

1. Veitch, D, Abioye, A, Morris-Jones, S, McGregor, A. Propionibacterium acnes as a cause of lung abscess in a cardiac transplant recipient. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:bcr2015212431. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-212431.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Achermann, Y, Goldstein, EJ, Coenye, T, Shirtliff, ME. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014;27:419–40. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00092-13.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Lawrence, H, Moore, T, Webb, K, Lim, WS. Propionibacterium acnes pleural empyema following medical thoracoscopy. Respirol Case Rep 2017;5:e00249. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.249.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Kuhajda, I, Zarogoulidis, K, Tsirgogianni, K, Tsavlis, D, Kioumis, I, Kosmidis, C, et al.. Lung abscess-etiology, diagnostic and treatment options. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:183. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.07.08.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. de Prost, N, Lavolé, A, Taillade, L, Wislez, M, Cadranel, J. Gefitinib-associated Propionibacterium acnes pleural empyema. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:556–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e31816e2417.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Durand, M, Godbert, B, Anne, V, Grosdidier, G. Large thoracomyoplasty and negative pressure therapy for late postpneumonectomy empyema with a retrosternal abscess: a modern version of the Clagett procedure. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:888–9. https://doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2010.262220.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Kurz, M, Kaufmann, BA, Baddour, LM, Widmer, AF. Propionibacterium acnes prosthetic valve endocarditis with abscess formation: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:105. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-105.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Gekowski, KM, Lopes, R, LiCalzi, L, Bia, FJ. Splenic abscess caused by Propionibacterium acnes. Yale J Biol Med 1982;55:65–9.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Case Report

- Propionibacterium acnes: an uncommon cause of lung abscess in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with bullous emphysema

- General

- Case Report

- Reactivation of minimal change disease after Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19

- Innovations

- Original Article

- At-home ECG monitoring with a real-time outpatient cardiac telemetry system during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Multisite assessment of emergency medicine resident knowledge of evidence-based medicine as measured by the Fresno Test of Evidence-Based Medicine

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Osteopathic manipulative treatment use among family medicine residents in a teaching clinic

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of an osteopathic peer recovery coaching model on treatment outcomes in high-risk men entering residential treatment for substance use disorders

- Clinical Images

- Recurrent bronchiolitis and stridor in an infant

- Bilateral idiopathic superior ophthalmic vein dilation

- Letters to the Editor

- Comments on “Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020”

- Response to “Comments on ‘Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020’”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Case Report

- Propionibacterium acnes: an uncommon cause of lung abscess in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with bullous emphysema

- General

- Case Report

- Reactivation of minimal change disease after Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19

- Innovations

- Original Article

- At-home ECG monitoring with a real-time outpatient cardiac telemetry system during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Multisite assessment of emergency medicine resident knowledge of evidence-based medicine as measured by the Fresno Test of Evidence-Based Medicine

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Osteopathic manipulative treatment use among family medicine residents in a teaching clinic

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of an osteopathic peer recovery coaching model on treatment outcomes in high-risk men entering residential treatment for substance use disorders

- Clinical Images

- Recurrent bronchiolitis and stridor in an infant

- Bilateral idiopathic superior ophthalmic vein dilation

- Letters to the Editor

- Comments on “Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020”

- Response to “Comments on ‘Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020’”