Impact of an osteopathic peer recovery coaching model on treatment outcomes in high-risk men entering residential treatment for substance use disorders

-

Raymond A. Crowthers

Abstract

Context

The United States has witnessed a disproportionate rise in substance use disorders (SUD) and co-occurring mental health disorders, paired with housing instability, especially among racially minoritized communities. Traditional in-patient residential treatment programs for SUD have proven inconsistent in their effectiveness in preventing relapse and maintaining attrition among these patient populations. There is evidence showing that peer recovery programs led by individuals who have lived experience with SUD can increase social support and foster intrinsic motivation within participants to bolster their recovery. These peer recovery programs, when coupled with a standardized training program for peer recovery coaches, may be very efficacious at improving patient health outcomes, boosting performance on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) national outcome measures (NOMs), and helping participants build an overall better quality of life.

Objectives

The goal of this study is to highlight the efficacy of a peer recovery program, the Minority Aids Initiative, in improving health outcomes and associated NOMs in men with SUD and/or co-occurring mental health disorder.

Methods

Participants received six months of peer recovery coaching from trained staff. Sessions were guided by the Manual for Recovery Coaching and focused on 10 different domains of recovery. Participants and coaches set long-term goals and created weekly action plans to work toward them. Standardized assessments (SAMHSA’s Government Performance and Results Act [GPRA] tool, Addiction Severity Index [ASI]) were administered by recovery coaches at intake and at the 6-month time point to evaluate participant progress. Analyses of participant recovery were carried out according to SAMHSA’s six NOMs and assessed the outcomes of the intervention and their significance.

Results

A total of 115 participants enrolled in the program over a 2-year period. Among them, 53 were eligible for 6-month follow-up interviews. In total, 321 sessions were held, with an average of three sessions per participant. Participants showed marked improvement across five of the six NOMs at the end of the 6-month course and across all ASI outcomes, with the exception of three in which participants reported an absence or few symptoms at intake.

Conclusions

Our study shows that participants receive benefits across nearly all NOM categories when paired with recovery coaches who are well trained in medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) over a 6-month period. We see the following: a higher rate of abstinence; increased housing stability; lower health, behavioral, and social consequences; lower depression and anxiety; longer participant-recovery coach exposure time; and higher follow-up rates. We hope that our results can contribute to advancements and greater acceptance in the implementation of peer recovery coaching as well as an improvement in the lives of the communities affected by substance use.

The United States is facing a crisis of rising substance use disorders (SUD) and co-occurring mental health disorders [1]. In 2019, 20.4 million people in the United States were diagnosed with an SUD, yet only 10.3% of these people received SUD treatment [2]. These issues are exacerbated by various socioeconomic barriers, particularly housing instability, which has been shown to increase the risk of substance use among US adults [3, 4]. Almost 50% of all individuals who experience an SUD will also experience a co-occurring mental health disorder, such as anxiety and depression [5, 6]. Mortality from SUD has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has made access to treatment more difficult [7] and has disproportionately impacted racially minoritized communities [8], [9], [10]. This points to the need for a comprehensive SUD treatment program that promotes long-term drug abstinence and provides linkage to stable housing and mental health services [11], [12], [13], [14].

Many traditional in-patient residential treatment programs have shown to be inconsistent in long-term sobriety, positive mental health outcomes, and housing stability. A systematic review analyzing the effectiveness of residential treatment for SUD only showed moderate quality evidence that treatment reduced substance use and improved mental health [15]. Many studies suffer from methodological flaws and high attrition at follow-up. In one such study, only 34% of participants completed the 3-month follow-up after discharge [16]. The field overall lacks a single standard for SUD treatment, with little integration of mental health treatment and continuity of care postdischarge [13, 15, 17, 18]. A major contributing factor as to why some residential treatment programs for SUD have not worked is due to a lack of emphasis on developing the intrinsic motivation of the participants [19, 20]. One option to address this is a peer recovery coaching model that more directly taps into participant motivations during SUD treatment.

Peer recovery programs are led by “peer recovery coaches,” who are individuals that have lived experience with SUDs and thus can lend their experience and empathy to others facing similar issues [21]. A systematic review on peer recovery models indicates that they have been effective [22] at increasing social supports and reducing relapse rates after discharge [23, 24]. For example, a study by Hansen et al. [21] assessing a standardized peer recovery program in Texas for 180 clients with SUDs reported a 17.0% decrease in prescription opioid drug misuse, a 22.0% increase in stable housing, a 14.5% decrease in depression symptoms, and a 21.8% decrease in anxiety symptoms for the participants at the 6-month follow-up. These benefits may be attributed to peer recovery coaching that provides a higher level of relatedness between the participant and peer recovery coach, fostering more supportive relationships that encourage continuation of care [25]. Hansen et al. [21] also demonstrates that providing a standardized training program for peer recovery services can bolster the skills of the peer recovery coaches and enhance their participants’ outcomes. This can include operationalizing elements of the participant interview to allow for accurate measuring of outcomes like drug abstinence and mental health improvement [26, 27]. This paper will focus on a peer recovery coaching model implemented at several addiction treatment centers in New Jersey that aims to address this gap through a standardized training process for all peer recovery coaches. This study will illustrate the methodology behind our peer recovery program and examine whether this initiative has influenced changes in substance use outcomes for participants.

Methods

The team at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine received approval from the Rowan University IRB committee (Pro. no. 2020001111). The data evaluation team at Rutgers University School of Social Work’s Center for Prevention Science (hereafter “Rutgers CPS,” New Brunswick, NJ) received approval from the Rutgers Arts and Sciences IRB committee (Pro. no. 2019002500). This study was funded by a discretionary grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, #6H79TI082453). Participants were read a consent script that included the risks, requirements, and compensation, and asked the participant for verbal consent prior to intake interviews. Rutgers personnel provided reminder calls and texts to participants in advance of 6-month follow-up interview dates. Participants received a $30 gift card for completion of the follow-up interview. A waiver of informed consent was granted for completion of follow-up Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) interviews over the phone.

Study setting, population, and design

Research coordinators at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine (Stratford, NJ) engaged and recruited participants in partnership with staff at Maryville Addiction Treatment Centers across New Jersey beginning in September 2019. Participants had to meet the following criteria: 1) report being a man; 2) be over the age of 18; 3) be diagnosed with an SUD; 4) live with or be at high risk for HIV; and 5) live in the Newark, Atlantic City, or Camden metropolitan areas. Due to the disproportionate impact of the opioid crisis on racially minoritized populations, patients were also given the choice to self-report race and ethnicity as part of the intake questionnaire. There were 28 recruitment goals for the first and second years of the program, with racially diverse samples of 45 and 70 participants respectively, with the goal of recruiting 300 men over a 5-year period. Many participants were already enrolled in a treatment program at a Maryville center. This observational cohort study collected data at intake and 6-month time points. All men who enrolled in the Minority Aids Initiative study during the first two fiscal years of the grant (9/30/2019–9/29/2021) were included in the overall sample (n=115). Similarly, analyses that required intake and 6-month data only included men who had completed their 6-month interview OR were beyond the 6-month data collection window (i.e., 8 months postintake) at the end of Year 2 (i.e., 9/29/2021).

Clinical staff at Maryville assessed participants’ SUD at enrollment. Participants presenting with co-occurring substance use/mental health disorders were referred to a psychiatric nurse practitioner to determine severity, establish stability, and prescribe psychotherapeutic medication if necessary.

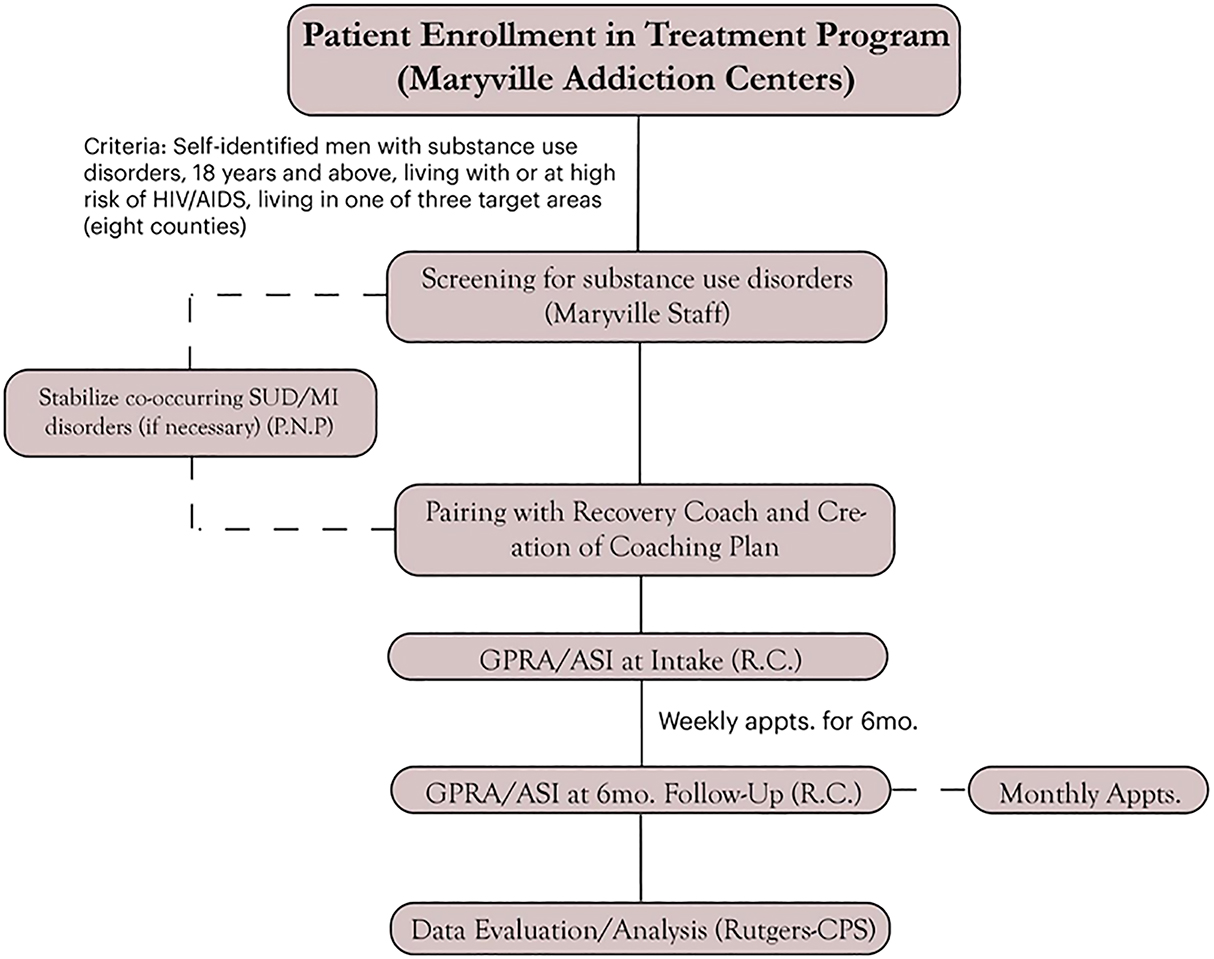

Participants were assigned a peer recovery coach at Maryville at enrollment. Coaches had received prior training in medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). The meeting goals were for coaches to meet with participants at least once a week during the first 6 months of the program and at least once a month thereafter. Coaches administered SAMHSA’s GPRA tool, including items from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), at intake. Sessions were guided utilizing the Manual for Recovery Coaching, and coaches worked with participants to develop weekly action plans containing steps to address their long-term goals. see Figure 1 for an illustrated patient pathway.

Participant flowchart.

Assessments and metrics

The GPRA forms, including items from the ASI, were utilized to assess participants at intake and 6-month time points. The GPRA is a performance measure tool created by SAMHSA that utilizes a structured interview to measure outcomes including substance use, mental and physical health, and family and living conditions. Patients are also able to opt-in to self-reporting demographic information including gender, race, and ethnicity via multiple-choice or write-in [28]. The ASI is part of the GPRA and is a validated structured interview that assists with diagnosis of substance use and mental health disorders, treatment planning, and outcome evaluation [29]. Patients reported one or more SUD (e.g., opioid use and/or alcohol use) via the ASI. The two teams at Rowan and Rutgers worked together to train recovery coaches to administer the tool and provided oversight to account for missing data and/or errors

The Manual for Recovery Coaching was utilized to guide coaching sessions and develop a recovery plan [30]. Plans focused on 10 domains: recovery from opioid use disorders; living and financial independence; employment and education; relationships and social support; physical health; leisure and recreation; independence from legal problems and institutions; mental wellness; spirituality; and HIV/hepatitis risk reduction. Coaches reported weekly on the domains on which the participants focused, and frequencies of each domain were observed.

SAMHSA’s client-level national outcome measures (NOMs) guided the analysis of participant outcomes [31]. The NOMs, which were assessed at intake and 6-month interviews, assessed the following measures: abstinence (no days utilizing alcohol or illegal drugs during the past 30 days); crime and criminal justice (no arrests during the past 30 days); employment/education (either currently employed, full-time, or part-time, or enrolled in a school or job training program, full-time or part-time); health/behavioral/social consequences (past-30 day absence of stress, functional impairment, or emotional problems directly related to substance use); social connectedness (past 30-day attendance in self-help groups for recovery and/or interaction with family/friends supportive of recovery); and housing stability (past 30-day ownership or rental of apartment, room, or house). Due to GPRA intake administration occurring shortly after treatment began for some participants, the evaluation team utilized a parallel metric that assessed abstinence during the 30 days prior to intake for the current treatment episode. For complete information on the response sets and raw data utilized to construct the NOMs, please see the Supplemental Table.

ASI items were also included to address changes in addiction and mental health symptoms over the 6-month period. Coaches asked participants how many days they experienced symptoms over the past 30 days. Responses were coded to binary yes–no as to whether someone had one or more days of experiencing symptoms. Suicidality and psychosis were not included because no participants reported them at either time point.

Data management and analyses

Recovery coaches uploaded de-identified participant forms to a secure, HIPAA-compliant Box drive overseen by Rutgers CPS personnel, who were responsible for managing, evaluating, verifying, and entering project data to SAMHSA’s Performance Accountability and Reporting System (SPARS) with oversight from Rowan staff. The Rutgers CPS evaluation team performed data analyses off-server utilizing Microsoft Excel, SPSS 28 [32], and Stata 16 [33]. Analyses included descriptive statistics of central tendency and distribution, and single-group paired-sample tests of symmetry to examine whether ASI and NOM outcome measures changed significantly from intake to 6 months. Nonparametric tests (McNemar’s x 2) and a significance threshold of p<0.05 were utilized. Cohen’s rules of thumb for power required to detect significance (at a threshold of p<0.05) in x 2 tests indicate that 785, 87, and 26 cases are needed to detect small, medium, and large effects, respectively [34]. To detect changes utilizing the same test and threshold when including one confounding factor in analyses increases these same respective minimum case counts to 964, 107, and 39, respectively. Thus, our a priori data analytic plan was to conduct analyses in subsequent years when smaller yet meaningful effects could be detected with and without confounding factors. However, the funding sponsor requested inferential data analyses after seeing drastic improvements in GPRA outcomes (utilizing descriptive information alone) compared to other grantee programs. Although conducting analyses with small sample sizes can increase the likelihood to misinterpret nonsignificant findings (i.e., false negatives), there is less concern about the risk for false positives. Therefore, exploratory analyses were conducted on all outcome measures.

Results

As of the end of the second year of the Minority Aids Initiative (9/29/21), 117 men were engaged in the recovery coaching treatment program. Among them, 115 opted to enroll in the study and completed GPRA intake interviews. Demographic breakdowns are displayed in Table 1. A total of 114 (99.1%) men identified as cisgender and 1 (0.9%) as transgender. Sixty (52.2%) identified as White, 34 (29.6%) as Black or African American, 4 (3.5%) as Multiracial, and 14 (14.8%) as None of the Above. Of the 28 participants who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic, 22 (78.5%) identified as Puerto Rican, two (7.1%) as Dominican, one (3.6%) as Cuban, and four (14.3%) as Other. The mean participant age was 35.4 years old (range, 19–62 years), and the most represented age group were men aged 25–34 (40.9%).

Demographics and substance use disordersa (intake).

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Cisgender man | 99.1% (114) |

| Transgender man | 0.9% (1) |

| Race | |

| White | 52.2% (60) |

| Black or African American | 29.6% (34) |

| Multiracial | 3.5% (4) |

| None of the above | 14.8% (17) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 24.8% (28) |

| Not Hispanic | 75.2% (85) |

| Age group, years | |

| 18–24 | 13.89% (16) |

| 25–34 | 40.9% (47) |

| 35–44 | 26.1% (30) |

| 45–54 | 13.9% (16) |

| 55–64 | 5.2% (6) |

| Substance use diagnosis | |

| Opioid use | 80.0% (92) |

| Alcohol use | 13.9% (16) |

| Stimulant use | 3.5% (4) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/anxiolytic use | 1.7% (2) |

| Hallucinogen use | 0.8% (1) |

-

aRace and ethnicity were considered in the analysis and collection of this data due to the health disparities that disproportionately impact minoritized communities affected by the opioid crisis.

Substance use breakdowns are displayed in Table 1. Among all participants, opioid use disorders were the most common substance use diagnosis, with 80.0% (n=92) of participants presenting. Following were alcohol use disorders (13.9%, n=16), stimulant use disorders (3.5%, n=4), sedative-hypnotic/anxiolytic use disorders (1.7%, n=2), and hallucinogen use disorders (0.8%, n=1).

For participants who completed recovery coaching sessions (n=109), coaches spent a total of 391.7 h across 321 sessions providing evidence-based coaching and strengths-based case management through motivational interviewing techniques. A multitude of services were discussed, referred to, or linked during these sessions (Table 2).

Recovery coaching session services, referrals, and linkage.

| Service type | Service discussed % (n) | Referral made % (n) | Linkage completed % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery planning | 96.33 (105) | 35.78 (39) | 28.44 (31) |

| Building recovery capital | 54.13 (59) | 7.34 (8) | 3.67 (4) |

| Transition from treatment to community | 39.45 (43) | 10.09 (11) | 9.17 (10) |

| Mutual support meetings | 35.78 (39) | 34.86 (38) | 28.44 (31) |

| Transportation services | 18.35 (20) | 12.84 (14) | 8.26 (9) |

| Legal services | 18.35 (20) | 4.59 (5) | 2.75 (3) |

| Educational services | 18.35 (20) | 4.59 (5) | 0.92 (1) |

| Relationships | 16.51 (18) | 5.50 (6) | 4.59 (5) |

| Relapse | 9.17 (10) | 5.50 (6) | 2.75 (3) |

| Employment services | 7.34 (8) | 4.59 (5) | 1.83 (2) |

| Re-engagement in treatment | 6.42 (7) | 4.59 (5) | 1.83 (2) |

| MAT services | 5.50 (6) | 1.83 (2) | 2.75 (3) |

| Housing services | 5.50 (6) | 1.83 (2) | 1.83 (2) |

| Community resources development | 3.67 (4) | 0.92 (1) | 0.92 (1) |

| Medical services | 2.75 (3) | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) |

| Spirituality services | 2.75 (3) | 1.83 (2) | 0.00 (0) |

| Sexual health | 2.75 (3) | 1.83 (2) | 0.92 (1) |

| Employment/first paycheck | 2.75 (3) | 0.92 (1) | 1.83 (2) |

| Family services | 1.83 (2) | 3.67 (4) | 0.92 (1) |

| Informational resource other | 1.83 (2) | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) |

| Recovery support during transitions that increase risk other | 1.83 (2) | 0.92 (1) | 0.92 (1) |

| Medical insurance services | 0.92 (1) | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) |

| Building recovery capital other | 0.92 (1) | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) |

| Death in family | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

| Recovery support during crisis other | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

| Recovery support during transitions that increase risk | 0.92 (1) | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) |

| Physical illness | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

| HIV/Hepatitis education | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

| Loss of housing | 0.92 (1) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

-

Frequencies are displayed for the 109 participants with recovery coaching data available in time for the Year 2 evaluation report. The frequency is at the participant level (i.e., the rate of discussion for a participant across their recovery coaching sessions). The following services were not discussed in any sessions: Hepatitis services, HIV services, HIV case management, COVID-19 services, recovery support during crisis, reengagement in HIV/hepatitis care, functional analysis, informational resources, and supporting your recovery for life.

-

MAT, medication-assisted treatment.

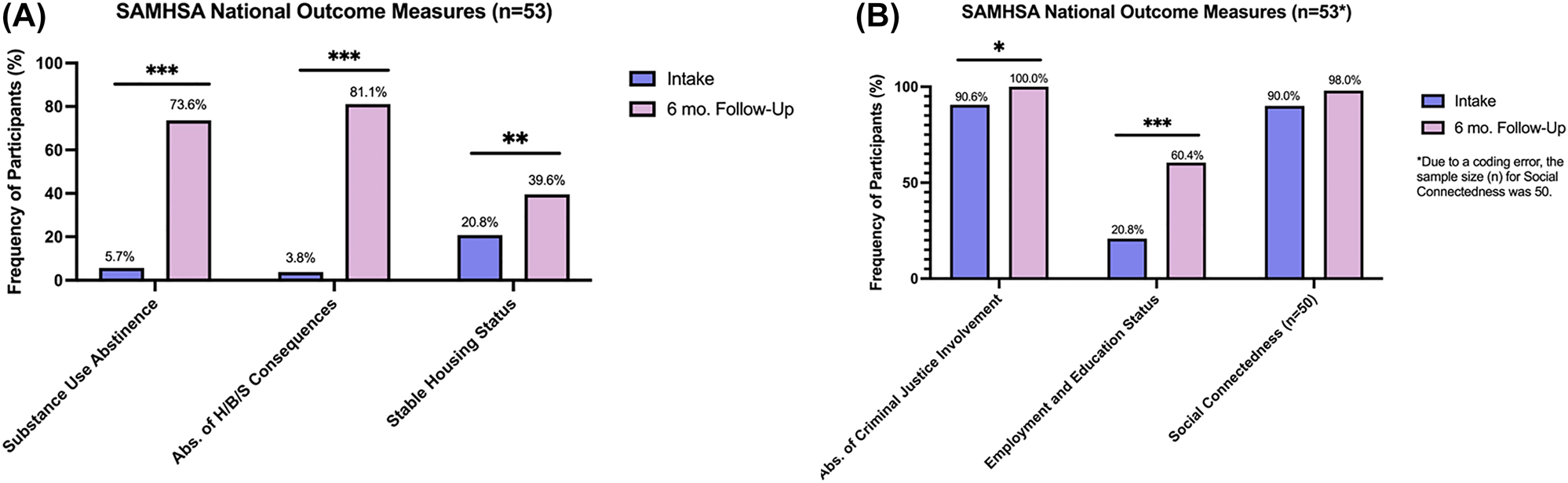

By the end of year two, 65 participants had either completed 6-month interviews or were beyond the sponsor’s end of the data collection window (i.e., 8 months postintake) determined by the funding sponsor. Of those 65 participants, 53 completed the appointment and respective GPRA interviews (follow-up rate of 81.5%). There was a significant improvement on five of the six NOMs from intake to 6-month time points among these participants (Figure 2). Substance use abstinence increased (x 2=20.00, p<0.001), as did the likelihood for participants to report no health-related, behavioral, or social consequences of drug use (x 2=41.00, p<0.001). Housing stability increased (x 2=7.14, p=0.008), as well as the likelihood for participants to report an absence of criminal involvement (x 2=5.00, p=0.025). Employment and education status, defined as being employed or in an educational program, also increased (x 2=19.17, p<0.001). The change in feeling socially connected increased (i.e., from 90.0% to 98.0%), albeit to a nonsignificant degree (x 2=2.67, p=0.103).

SAMHSA’s national outcome measures. p<0.001***, p<0.01**, p<0.05*.

With regard to mental health outcomes, participants displayed significant improvements on all measures that were powered for analyses. There was a significant reduction in the likelihood of both depression and anxiety (Ps<0.001) and trouble understanding, concentrating, or remembering (p<0.01), and improvement for being prescribed psychotherapeutic medication (p<0.001). Two ASI measures demonstrated floor effects (0 cases at intake) and one had few cases (<5 at both timepoints), necessitating interpretation of a different test statistic (Fisher’s Exact Test). For these reasons, it was not possible or appropriate to test for symmetry across time points. Full statistics are displayed in Table 3.

Mental health metrics at intake and 6 months.

| Mental health metrics | No. of cases at intake | % Of total participants at intake | No. of cases at 6-month follow-up | % Of total participants at 6-month follow-up | Test statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 34 | 64.5% | 13 | 24.5% | x 2=19.17 | <0.001c |

| Anxiety | 41 | 77.4% | 18 | 33.9% | x 2=23.00 | <0.001c |

| Hallucination | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not conducted due to absolute floor effects | Not conducted due to absolute floor effects |

| Trouble understanding, concentrating, or remembering | 18 | 34.0% | 3 | 5.7% | x 2=15.00 | 0.001b |

| Trouble controlling violent behavior | 3 | 5.7% | 0 | 0 | Not conducted due to floor effects and different test required | Not conducted due to floor effects and different test required |

| Attempted suicide | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not conducted due to absolute floor effects | Not conducted due to absolute floor effects |

| Prescribed psychotherapeutic medication | 6 | 11.3% | 9 | 17.0% | x 2=20.00 | <0.001c |

-

The above frequencies displayed are for the 53 cases with complete data at intake and 6-month follow-up interviews. Tests of symmetry utilize McNemar’s chi-square (x 2) tests. Because the cells contained 0 cases for both time points in the “hallucination” and “attempted suicide” outcomes, tests were not possible to conduct due to absolute floor effects (0 cases pre-intervention). For the “trouble controlling violent behavior” outcome, there were fewer than 5 cases at intake and 0 cases at 6 months, necessitating interpretation of a different test (Fisher’s Exact) designed for small cell sizes. Given the small sample size at both time points and the different test required from other ASI outcomes, it was determined that conducting tests on this variable would be more appropriate once five or more cases were present in the intake data (i.e., ostensibly when analyzing data in subsequent years of the program). cp<0.001, bp<001, ap<0.05.

Discussion

There is little evidence to evaluate the extent of the efficacy of peer recovery coaching as a method of improving outcomes for those with SUD. The goal of this study was to elucidate the effects that peer recovery coaching has on follow-up rates, NOMs (e.g., drug abstinence, housing stability), and mental health outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression). We believe that positive changes in these areas would lend themselves to improvements in a participant’s recovery.

Among the current studies, we find a higher rate of substance use abstinence among our cohort (73.6% vs 66.8%) and a meaningful difference in the rate of change (final stable housing/initial stable housing) in housing stability (90.4% vs 21.1%) [35]. In Linton et al. [36], homelessness was associated with relapse and experienced by 38% of their participants. Therefore, a decrease in substance misuse coupled with an increase in housing stability is encouraging support for our peer recovery model. Furthermore, we find a large difference in health, behavioral, and social consequences compared to a report compiling these data from other SAMHSA grants (2134.2% vs 23.7%) [37]. The percentage of participants who deny health, behavioral, or social consequences at the 6-month follow up is less than the average found on other discretionary grants (81.1% vs 84.7%) [37]. Therefore, the vast majority of the difference lies in the percentage of those who deny consequences at intake (3.80% vs 68.2% for other grants). Through our grant, participants’ consequences diminished from nearly universal (96.2%) to around the national level (19.9%). We also observe appreciable rates of change for depression and anxiety (−62.0% and −56.2%), which is higher than what McLellan et al. has shown to improve [29] for these same mental health conditions (−14.5% and −21.8%, respectively)

Our follow-up rate of 81.5% exceeds that of a similar project [4], and overall, our 6-month follow-up rate is above the national rate for other SAMHSA Center for Substance Abuse Treatment discretionary grants [37]. Continued exposure to the recovery coach might foster intrinsic motivation of the participant, thereby allowing maximal therapeutic value and a higher chance of long-term sobriety. During sessions, the four services discussed most often were recovery planning (96.33%), building recovery capital (54.13%), transition from treatment to community (39.45%), and mutual support meetings (35.78%). These all focus on important skills and social connections helpful for maintaining sobriety, demonstrating what the participants needed the most help managing. Recovery planning and mutual support meetings were also the most common topics that led to referrals and linkages. Less often discussed, but still common topics during sessions, were transportation (18.35%), legal services (18.35%), and educational services (18.35%). We believe that several of these topics demonstrate the ability recovery coaches have to tailor sessions to the participants’ particular needs, struggles, and aspirations beyond their SUD.

Because the Minority Aids Initiative is interested in engaging racially minoritized men, we aimed to recruit a sample that is predominantly Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men. Enrollment of men reporting Black/African American or mixed race and/or Hispanic ethnicity has been as follows across the project: Year 1–40.0% (n=18 of 45); Year 2–66.7% (n=46 of 69); Year 3–73.7% (n=14 of 19); and across the project to date (9/30/2019 to 3/31/2022)−58.7% (n=78 of 133). Although we started with a smaller proportion of Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men, we have been successful with engaging a higher proportion of minority men in subsequent years. We hope to continue this trend to better understand how to address the health inequities and lack of efficacy in substance use treatment for racially and ethnically minoritized communities.

One limitation of this paper is the reliance on self-reporting from the participants. Given the relationship of trust between the coach and participant, this was intentional. However, this could have led to biased answers. Next, we recognize that the designations “Black” and “African American,” and “Hispanic” and “Latino,” are not synonymous with each other [28]. This is a limitation in the design of our self-reporting, and we hope to rectify this in future iterations of our client intake surveys. Furthermore, we believe that the definition of stable housing could be more insightful if it expanded the criteria for what is considered to be ‘stable housing’ and factored in the duration of time spent in one residence. The GPRA currently only recognizes ‘stable housing’ as “own/rent apartment, room, or house” based on SAMHSA’s definition of stable housing. This may exclude participants who are living with someone else but are otherwise in ‘stable’ housing. If a participant has moved to 10 different houses in the past 30 days but is renting an apartment at the time of the interview, the GPRA would not be able to reflect this as ‘unstable’ housing. Although our use of NOMs followed established definitions for each outcome, it is important to note that some response options contributed more than others. For example, participants were less likely to report abstinence for drugs compared to alcohol, although both are required for the abstinence NOM. Although changes in employment/education were significant, the changes were exclusively related to employment, because no participants reported education (school or job training) activities at intake or 6-month time points. Similarly, the social connectedness outcome was primarily influenced by participants endorsing interactions with family and/or friends who were supportive of their recovery. Finally, we realize that having a control group to which we could directly compare our data would be beneficial in establishing the direct impact that recovery coaching specifically has on participants’ outcomes.

Future iterations of this research could include disparity analyses between groups to see if the NOMs change with Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino men differently compared to White men. We also recommend more robust evaluations of recovery coaching engagement and quality. Although we were able to find significance in a smaller sample size (n=53), we were only powered to detect large effects (26 cases required). Thus, analyzing these relationships with a larger sample is optimal for exploratory analyses (e.g., to account for potential confounding factors) or the detection of medium effect sizes (87 cases required, 107 required when including one control/confounding factor in McNemar’s tests) (see Cohen, 1992). Future research should examine whether other factors (e.g., comorbid psychiatric disorders and infectious diseases, treatment status for those comorbidities) confound the relationships we tested as the sample size grows. Furthermore, the interpretation of ASI outcome changes that were not plausible to analyze (due to an absence of men or few men with symptoms at intake) will benefit from analysis in the future if more men endorse symptoms at intake. Similarly, the analysis of the social connectedness NOM showed a directional but nonsignificant improvement, and future analyses with a larger sample size may identify changes like this achieving statistical significance. We hope to continue recruiting a higher proportion of racially minoritized men for the Minority Aids Initiative in subsequent years to better meet the goals of the grant. To elucidate whether the peer recovery coaching program has a different relationship to outcomes based on participant characteristics, we could examine whether clinical characteristics and outcomes differ by demographic characteristics in future analyses.

We believe that this research has the potential to demonstrate the power behind an essential pillar of osteopathic medicine: the idea that we all are comprised of mind, body, and spirit. When one of these mainstays is ignored, it can be quite difficult for an individual to heal. We strongly feel that this project, in addressing all three of these pillars, will help attenuate the potency of the opioid crisis and bring the philosophy of osteopathic medicine to the forefront of recovery coaching.

Conclusions

In the last few years, we have seen a spike in the number of SUD, especially among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino communities [31]. Peer recovery coaching is a method of treatment that can be implemented in addiction and drug abstinence, yet it has not been extensively studied. We found that: a participant paired with a recovery coach extensively trained in MOUD can achieve a higher drug abstinence percentage. In addition, we found: a significant increase in the rate of change of housing stability; lower health, behavioral, and social consequences; lower depression and anxiety evaluations; longer participant-recovery coach exposure time; and higher follow-up rates of participants in the community by their 6-month follow up.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lara Fougnies for assistance with entry and management of evaluation data, as well as N. Andrew Peterson and Kristen Gilmore Powell for their input on evaluation activities at the Rutgers University School of Social Work Center for Prevention Science.

-

Research funding: The current study was supported by a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (grant no. 6H79TI082453).

-

Author contributions: R.C., M.A., A.V., J.L., S.C., M.E., S.S., E.B., and R.J. provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; R.C., M.A., A.V., and J.L. drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; K.S. and R.J. gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None reported.

-

Ethical approval: The team at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine received approval from the Rowan University IRB committee (Pro. no. 2020001111). The data evaluation team at Rutgers University School of Social Work’s Center for Prevention Science received approval from the Rutgers Arts and Sciences IRB committee (Pro. no. 2019002500).

-

Informed consent: Verbal consent was obtained after researchers read a thorough consent script at intake. A waiver of informed consent was granted for completion of six-month follow-up interviews over the phone.

References

1. Corredor-Waldron, A, Currie, J. Tackling the substance use disorder crisis: the role of access to treatment facilities. J Health Econ 2022;81:102579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102579.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2020). 2019 National survey on drug use and health; 2019. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29392/Assistant-Secretary-nsduh2019_presentation/Assistant-Secretary-nsduh2019_presentation.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

3. Austin, AE, Shiue, KY, Naumann, RB, Figgatt, MC, Gest, C, Shanahan, ME. Associations of housing stress with later substance use outcomes: a systematic review. Addict Behav 2021;123:107076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Kleinman, MB, Doran, K, Felton, JW, Satinsky, EN, Dean, D, Bradley, V, et al.. Implementing a peer recovery coach model to reach low-income, minority individuals not engaged in substance use treatment. Subst Abuse 2021;42:726–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2020.1846663.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. National Institute of Mental Health. Substance use and co-occurring mental disorders. National Institute of Mental Health. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/substance-use-and-mental-health. Published March 2021. [Accessed 15 Mar 2022].Search in Google Scholar

6. Calarco, CA, Lobo, MK. Depression and substance use disorders: clinical comorbidity and shared neurobiology. Int Rev Neurobiol 2021;157:245–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2020.09.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Avena, NM, Simkus, J, Lewandowski, A, Gold, MS, Potenza, MN. Substance use disorders and behavioral addictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related restrictions. Front Psychiatr 2021;12:653674. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.653674.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Tai, DBG, Shah, A, Doubeni, CA, Sia, IG, Wieland, ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:703–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa815.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Saloner, B, Lê Cook, B. Blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to complete addiction treatment, largely due to socioeconomic factors. Health Aff 2013;32:135–45. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0983.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Samples, H, Williams, AR, Olfson, M, Crystal, S. Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;95:9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.09.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Eastwood, B, Peacock, A, Millar, T, Jones, A, Knight, J, Horgan, P, et al.. Effectiveness of inpatient withdrawal and residential rehabilitation interventions for alcohol use disorder: a national observational, cohort study in England. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;88:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Malivert, M, Fatséas, M, Denis, C, Langlois, E, Auriacombe, M. Effectiveness of therapeutic communities: a systematic review. Eur Addiction Res 2012;18:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Rome, AM, McCartney, D, Best, D, Rush, R. Changes in substance use and risk behaviors one year after treatment: outcomes associated with a quasi-residential rehabilitation service for alcohol and drug users in Edinburgh. J Groups Addict Recovery 2017;12:86–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/1556035x.2016.1261384.Search in Google Scholar

14. Vanderplasschen, W, Colpaert, K, Autrique, M, Rapp, RC, Pearce, S, Broekaert, E, et al.. Therapeutic communities for addictions: a review of their effectiveness from a recovery-oriented perspective. Sci World J 2013;2013:427817. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/427817.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. de Andrade, D, Elphinston, RA, Quinn, C, Allan, J, Hides, L. The effectiveness of residential treatment services for individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;201:227–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Turner, B, Deane, FP. Length of stay as a predictor of reliable change in psychological recovery and well being following residential substance abuse treatment. Ther Commun 2016;37:112–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/tc-09-2015-0022.Search in Google Scholar

17. Andersson, HW, Wenaas, M, Nordfjærn, T. Relapse after inpatient substance use treatment: a prospective cohort study among users of illicit substances. Addict Behav 2019;90:222–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Decker, KP, Peglow, SL, Samples, CR, Cunningham, TD. Long-term outcomes after residential substance use treatment: relapse, morbidity, and mortality. Mil Med 2017;182:e1589–95. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00560.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Andersson, HW, Steinsbekk, A, Walderhaug, E, Otterholt, E, Nordfjærn, T. Predictors of dropout from inpatient substance use treatment: a prospective cohort study. Subst Abuse 2018;12:1178221818760551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221818760551.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Cabral, RR, Smith, TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: a meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:537–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025266.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Hansen, MA, Modak, S, McMaster, S, Zoorob, R, Gonzalez, S. Implementing peer recovery coaching and improving outcomes for substance use disorders in underserved communitie. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2020;21:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2020.1824839.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Eddie, D, Hoffman, L, Vilsaint, C, Abry, A, Bergman, B, Hoeppner, B, et al.. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: a systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Front Psychol 2019;10:1052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Reif, S, Braude, L, Lyman, DR, Dougherty, RH, Daniels, AS, Ghose, SS, et al.. Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 2014;65:853–61. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Bassuk, EL, Hanson, J, Greene, RN, Richard, M, Laudet, A. Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016;63:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. O’Connell, MJ, Flanagan, EH, Delphin-Rittmon, ME, Davidson, L. Enhancing outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders through skills training and peer recovery support. J Ment Health 2020;29:6–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294733.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. McGuire, AB, Powell, KG, Treitler, PC, Wagner, KD, Smith, KP, Cooperman, N, et al.. Emergency department-based peer support for opioid use disorder: emergent functions and forms. J Subst Abuse Treat 2020;108:82–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Kropp, F, Wilder, C, Theobald, J, Lewis, D, Winhusen, TJ. The feasibility and safety of training patients in opioid treatment to serve as peer recovery support service interventionists. Subst Abuse 2022;43:527–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1949667.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Schmidt, M. The language of race and ethnicity in academic medical publishing. J Osteopath Med 2021;121:121–3. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2020-0330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. McLellan, AT, Luborsky, L, Woody, GE, O’Brien, CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Disord 1980;168:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Loveland, DL, Boyle, MA. Manual for recovery coaching and personal recovery plan development. Peoria, IL: Fayette Companies; 2005.Search in Google Scholar

31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Outcome Measures by Program. Retrieved from: https://spars-rpt.samhsa.gov/CSAT/Chart/OutcomeChange [Accessed 5 Apr 2022]. SPARS Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2022.Search in Google Scholar

32. Released, IBMC. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

33. StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

34. Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.15510.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.Search in Google Scholar

35. Cooper, S, Lister, JJ, Enich, M, Fougnies, L, Powell, KG, Peterson, NA. An evaluation of the minority AIDS initiative for high risk men of New Jersey: Year 2 report. Annual progress report submitted to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD. 2021.Search in Google Scholar

36. Linton, SL, Celentano, DD, Kirk, GD, Mehta, SH. The longitudinal association between homelessness, injection drug use, and injection-related risk behavior among persons with a history of injection drug use in Baltimore, MD. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132:457–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SPARS Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Follow-up rate [real-time data source]. Retrieved from: https://spars-rpt.samhsa.gov/CSAT/Chart/FollowUp [Accessed 5 Apr 2022].Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2022-0066).

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Case Report

- Propionibacterium acnes: an uncommon cause of lung abscess in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with bullous emphysema

- General

- Case Report

- Reactivation of minimal change disease after Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19

- Innovations

- Original Article

- At-home ECG monitoring with a real-time outpatient cardiac telemetry system during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Multisite assessment of emergency medicine resident knowledge of evidence-based medicine as measured by the Fresno Test of Evidence-Based Medicine

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Osteopathic manipulative treatment use among family medicine residents in a teaching clinic

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of an osteopathic peer recovery coaching model on treatment outcomes in high-risk men entering residential treatment for substance use disorders

- Clinical Images

- Recurrent bronchiolitis and stridor in an infant

- Bilateral idiopathic superior ophthalmic vein dilation

- Letters to the Editor

- Comments on “Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020”

- Response to “Comments on ‘Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020’”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Cardiopulmonary Medicine

- Case Report

- Propionibacterium acnes: an uncommon cause of lung abscess in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease complicated with bullous emphysema

- General

- Case Report

- Reactivation of minimal change disease after Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19

- Innovations

- Original Article

- At-home ECG monitoring with a real-time outpatient cardiac telemetry system during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Medical Education

- Original Article

- Multisite assessment of emergency medicine resident knowledge of evidence-based medicine as measured by the Fresno Test of Evidence-Based Medicine

- Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine (OMT)

- Brief Report

- Osteopathic manipulative treatment use among family medicine residents in a teaching clinic

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Original Article

- Impact of an osteopathic peer recovery coaching model on treatment outcomes in high-risk men entering residential treatment for substance use disorders

- Clinical Images

- Recurrent bronchiolitis and stridor in an infant

- Bilateral idiopathic superior ophthalmic vein dilation

- Letters to the Editor

- Comments on “Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020”

- Response to “Comments on ‘Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020’”