Abstract

David Miall was, for many scholars, the person welcoming them into the field of empirical literary studies. The research he conducted together with Don Kuiken on the effects of stylistic features on reading, with a central role for (self-modifying) feeling (cf. Miall, David S. & Don Kuiken. 1994. Foregrounding, defamiliarization, and affect: Response to literary stories. Poetics 22(5). 389–407) has been the inspirational foundation for much of the research conducted in this and other fields, such as cognitive poetics. By combining methods from traditional literary reading (such as close reading), with methods more commonly used in psychology (such as experimental designs and self-report questionnaires), he gave new depth to the concept of reader response research (Whiteley, Sara & Patricia Canning. 2017. Reader response research in stylistics. Language and Literature 26(2). 71–87), concerning himself with actual readers’ testimonials. In honour of David, this paper will present a close reading, not of a literary text, but of a particular reader testimonial, namely an online book review. By applying a close reading informed by Text World Theory, I attempt to show how the social context in which this review was written influenced the expression of narrative absorption the reader experienced during reading. Consequently, I argue for an expansion not just of the methodological toolbox we use to investigate absorption in online social reading, but for an expansion of the concept of story world absorption itself.

1 Introduction

When I was a student of literary studies, I grew dissatisfied with the way we discussed literary texts in our classes. Rather than talking about how these texts affected us, and brought about memories or intense emotions – the main reasons that attracted me to reading books and studying literature – we talked about how different theoretical frameworks could be applied to interpret a text in a certain way. When I went in search for a different type of literary studies to satisfy my curiosity, I came in contact with David Miall, who quickly and quite generously, invited me to conduct my Master’s thesis research in his lab in Edmonton at the University of Alberta. David introduced me to a variety of different approaches to literature that focused on the effects of texts on readers, through his courses on empirical literary studies (cf. Miall 2006) and cognitive poetics (cf. Stockwell 2019), thereby expanding my understanding of literature reception tremendously. As my supervisor he also familiarized me with a different, more collaborative way of working, whereby we would collect reader response data from students as participants in our experiments, which we would subsequently discuss in lab meetings with the whole research group. It was an experience that would shape my entire academic career; in fact, I think I can go so far as to argue that David is the reason why I got excited to pursue a career in empirical literary studies in the first place.

My latest project investigates the experience of narrative absorption – a line of research I originally started during my time in Edmonton – in online reader reviews (Rebora et al. 2020a). Such reviews are a new source of reader response data, and when grappling with how to analyse this data, I was forced to acknowledge the limitations of the methodological framework I have worked with over the years. For the last two decades, researchers of narrative absorption have been developing methods to capture engaging reading experiences that rely heavily on embodied metaphors (Miall 2015), the most prominent of which is the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor. My project has focused on annotating corpora of reviews for mentions of absorption, categorized as such by semantic similarity with statements on the Story World Absorption Scale (SWAS, Kuijpers et al. 2014), an instrument originally developed to capture absorption (Lendvai et al. 2019). As the present study will show, however, some reviews cannot be categorized using a framework built on the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor, even when they seem to display high levels of absorption on the part of the reader.

In this paper, I will first describe the evolution of the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor in empirical literary studies and cognitive poetics. I will then give an overview of the study of online social reading in general and the study of absorption within this domain in particular. After introducing the case study, I will argue that, to account for absorption in online reader reviews, we need to broaden our methodological scope by incorporating close reading methodologies. By applying a Text World Theory approach to the case study review, I hope to show the importance such a method affords to the social context in which these reviews were created. In doing so, I will address the question of how these types of online interactions transform reading experiences and evaluations, making them difficult to capture with methods originally developed to capture solitary reading experiences.

2 The role of READING IS TRANSPORTATION in empirical research on absorption

READING IS TRANSPORTATION has been a prominent metaphor in literary theory for quite some time. The idea that the act of reading is like traveling, and the text is a world or place one can travel to, seemed to gain real traction in the nineties. It fuelled an abundance of theories, such as ‘possible worlds theory’ (Ryan 1991), ‘mental space theory’ (Fauconnier 1997), ‘Text World Theory’ (Werth 1999), ‘deictic shift theory’ (Segal 1995), and ‘transportation theory’ (Gerrig 1993). What these theories have in common is a reliance on spatial and embodied metaphors to describe what happens during text processing (Miall 2006, 2015). It has been argued that “the use of these embodied metaphors is just an indicator of the difficulty in explaining what narrative involvement amounts to” (Martínez 2014, p. 111). This is, perhaps, partly the reason why these theories have found their way into the empirical study of literature, where they were operationalized into measurable concepts, such as Transportation (Green and Brock 2000), or Story World Absorption (Kuijpers et al. 2014). Operationalization of theoretical concepts involves finding the right terminology that resonates with participants of studies. Most of these instruments (see Kuijpers et al. 2021 for an overview) feature a set of similar dimensions, namely: focused attention, emotional engagement, vivid mental imagery and deictic shift (Busselle and Bilandzic 2009; Green and Brock 2000; Kuijpers et al. 2014). In most studies, items are included that explicitly refer to the absorption metaphor, such as “I felt absorbed in the story” (Kuijpers et al. 2014). This item on the SWAS is specifically designed to capture depth of attention, whereas others fall under the ‘transportation’ dimension and pertain to the deictic shift that is at the core of the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor. Examples of such items are “When I was reading the story it sometimes felt like I was in the story world too” or “When I was finished with reading the story it felt like I had taken a trip to the world of the story”. The other dimensions on the SWAS – emotional engagement and mental imagery – do not make use of the same metaphor directly, but the items included do show an embodied sense of understanding, or allude to the text as a place. With that I mean that they pertain to psychological projection (Gavins 2007; Stockwell 2020), which is an extension of deictic projection (shifting your deictic anchorage) (Whiteley 2011) to include mental and emotional aspects, such as identification with a character. Examples of such items are “When I read the story I could imagine what it felt like to be in the shoes of the main character” (emotional engagement) or “When I was reading the story I could see the situations happening in the story being played out before my eyes” (mental imagery). In essence the SWAS focuses on text-oriented reader responses, rather than self-oriented reader responses (Cupchik et al. 1998), meaning that the emotions measured by the SWAS correspond to what happens in the story, whereas self-oriented reader responses correspond more to personal emotional memories evoked by the text.

3 Online social reading

Social media platforms like Goodreads (www.goodreads.com) are online environments where millions of people come to share their love of books. They recommend books to one another, write reviews and some even try their hand at writing ‘fan fiction’ (cf. Kuijpers 2018). Thus, in the digital age, reading is not always a solitary act, but can involve an immersive, social component that goes far beyond that of a real-life book club or a public poetry reading (Cordón-García et al. 2013; Merga 2015). The website Goodreads has collected about 3.5 billion book reviews written by 125 million members from all over the world (Goodreads 2022). As such, this online social reading platform holds a wealth of potentially valuable qualitative data on certain types of reading experiences, on how people interact about reading, or on the kind of criteria people use to evaluate the books they read. As Nuttall (2017) explains: “By minimizing the intervention of the researcher in data collection, the sampling of online reader reviews can be seen to mitigate the observer’s paradox.” (p. 156) Hence the data found on Goodreads more likely reflect the concerns of readers themselves (Swann and Allington 2009), in the language they use naturally to describe these experiences. Do readers, when unprompted by researchers, use similar embodied and spatial metaphors for reading? Do they even talk about feeling absorption, when not prompted by researchers?

This emphasis on spontaneous reader response gives online reader reviews an air of ecological validity (Nakamura 2013). Such assessment would have to be made with care, however, as the reader response data we encounter on online social reading platforms are very much considered and polished. Of course, people tend to write reviews after they have finished reading a book, so we are dealing with retrospective accounts of their reading experiences. But, in contrast to the typical retroactive accounts of reader response we gather within experiments, where participants read a text and immediately write about their experience, we have no way of knowing how long after reading people have written and posted their reviews on Goodreads. More importantly, as the reviews are part of a social discourse which takes place over time, reviewers may take a long time to think through and draft their responses (Peplow et al. 2015). Additionally, reviewers can decide whether they want to stay anonymous, use their own name, or craft a persona – performing a reader identity (Peplow et al. 2015, p. 150) – that is specific to the social interactions they partake in this environment (Vlieghe et al. 2016). As Thomas (2020) points out, the creation of these personae is governed in large part by “a sense in which users want to impress others in terms of the nature and sheer mass of reading they put on display, and in their ability to curate that material” (2020, p. 77).

Engaging in activities on a website like Goodreads has the potential to transform not only the subjective experience of reading, expanding it to include writing, commenting, distributing, criticizing and adapting (Vlieghe et al. 2016), but also the social life of readers participating in such an affinity space (Gee 2005), transforming reading – in the broadest sense of the word – in a uniquely shared activity. Vlieghe and colleagues describe online social reading platforms as “spaces where people exhibit shared affinity”, where “expertise is shown through a person’s responses in a given situation, rather than relying on affiliations and titles” and that such environments” appeal to people because they recognize and provide proper support for interest-driven endeavors where most local or mainstream institutions fail to do so” (2016, p. 28). The question for literary studies at this point is: taking these social contexts into account, how do these online interactions transform reading experiences and evaluations in ways that differ from those reading experiences we capture during experiments in labs? How do we access these new forms of reader response; what are the appropriate measures to capture information about these specific reading experiences?

3.1 Empirical research on online social reading

There have been a series of theoretical papers highlighting the relevance of studying online social reading practices for literary studies (e.g., Boot 2011; Nakamura 2013), and for reception studies (e.g., Murray 2018; Rehfeldt 2017; for a more complete literature review on the topic, see Rebora et al. 2021). The empirical research done so far touches – not surprisingly, considering the enormous amount and variation of data available – on a range of disconnected topics, such as manual analysis of text evaluations (Milota 2014), the metaphors reviewers use to describe the act of reading (Nuttall and Harrison 2020), the moral positions readers take when processing controversial books (Nuttall 2017), and the ethical position of the researcher in conducting research on online reader testimonials (Page 2017; Spilioti and Tagg 2017). Researchers generally seem to agree, though, that online reader reviews have made the intimate experience of reading – which has always been quite elusive to empirical investigation – visible to some extent (cf. Driscoll and Rehberg Sedo 2019; Peplow et al. 2015). These studies either use bottom-up data-driven approaches (e.g., Nuttall 2017; Nuttall and Harrison 2020), or a top-down quantitative approach (Milota 2014) to answer research questions about the reception of one particular text. But what if we want to know more about a specific type of reading experience and whether it can be found in reader reviews across a variety of books or even whole genres?

I am interested, and have been for years, in the specific reading experience that is narrative absorption – the feeling of getting lost in a good book (Nell 1988). Empirical studies on narrative absorption so far have only looked at this experience as purely solitary, part of the experience being that it renders readers unaware of their surroundings and their own body (Miall 2015, p. 187). However, the experience is investigated by asking readers explicitly about whether or not they felt absorbed during reading, effectively disrupting the very experience of interest. Not only is the data readily available on a platform like Goodreads unprompted by researchers, it also allows researchers to scale up their investigation, studying the experience of thousands or millions of readers across genres, authors or even oeuvres. Nevertheless, we have to ask ourselves, how far can online reviews convey truly natural absorption experiences. Does the social context in which people post their reviews change their expression of absorption? Is the experience of absorption broadened by the conversations about what is being read, which in themselves can also be absorbing? Is absorption during social reading practices experienced less intensely, due to a higher potential for distraction from the text, or is it perhaps experienced more intensely, because it is shared with others, rather like films or concerts are experienced in communal ways? In order to answer such questions, we will have to develop methods to investigate absorption in the specific context of online social reading activities.

3.2 The study of absorption in online reader response

To date, there have only been two distinct studies focusing on the experience of absorption and how it is expressed in online reader reviews, each taking an approach informed by the disciplinary background of its authors. Nuttall and Harrison (2020) aimed “to uncover some of the affordances of this new media environment for cognitive stylistic understandings of immersion and resistance (2020, p. 37)”. In their exploration of the immersive accounts of the novel Twilight they use a data-driven approach, coding a set of hundred 1-star and 5-star reviews, with the purpose of identifying the most used metaphors to describe immersive reading. The READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor was one of the most popular ones, but still only accounted for a quarter of the total metaphorical expressions (Nuttall and Harrison 2020, p. 43). A particular form of this metaphor was DIVING (intentionally) or FALLING (unintentionally) into the book, in which the reader seems to be the driving force of their movement into the book. In contrast, a reversal of the agency or directionality of this metaphor was also found, whereby the book seemed to exert a PULLING force over the reader. These metaphors are closely related to READING IS CONTROL (or even READING IS ADDICTION), which was one of the other most used metaphors to describe immersive reading. Nuttall and Harrison (2020) argue that the selection of metaphors used on Goodreads will likely not just reflect “the embodied experiences which underpin [reading], but also the topic (the specific book in question), the setting (the online forum), and the personal interests and motivations of the reviewers themselves” (2020, p. 39), which was evidenced by the reviewers of Twilight, falling back on additional metaphors such as READING IS EATING (i.e. “this book was addictive, I couldn’t get enough of it, like pizza” or “it’s addictive to many and yet lacks any kind of substance/nutritional value besides empty calories”). Their study shows that reviewers use an extensive array of metaphorical expressions to describe absorbing reading experiences, and display “a degree of awareness of the passivity or resistance with which they accept [a novels’] invitation for engagement” (Nuttall and Harrison 2020, p. 55).

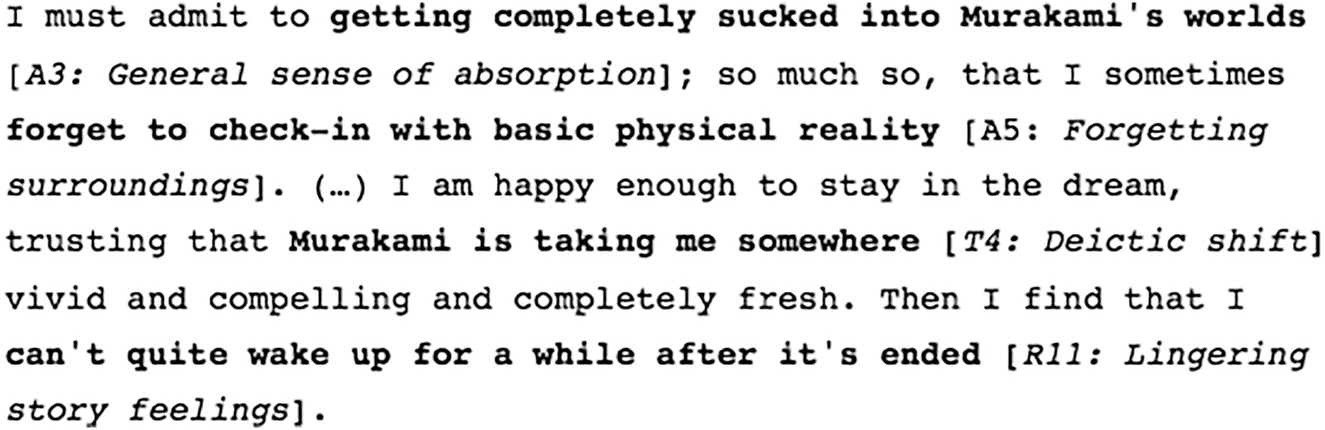

The other study, by Rebora et al. (2020a) combined computational methods such as machine learning with measures developed within empirical literary studies to investigate whether readers in their online evaluations of books talk about absorption in the same way researchers do when they investigate this experience in experimental settings. An annotation scheme based on the research on story world absorption (Kuijpers et al. 2014) was used as a guideline to manually annotate a corpus of 1,025 reader reviews. This corpus was then used to train a machine-learning algorithm to automatically detect instances of absorption in large quantities of online reader reviews posted on Goodreads (Lendvai et al. 2019; Rebora et al. 2020b). A group of five annotators manually annotated the reviews for the occurrence of absorption, matching segments of the reviews to statements on the Story World Absorption Scale (SWAS; Kuijpers et al. 2014). Figure 1 shows an excerpt of a review on Haruki Murakami’s novel The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles in which segments that showed semantic or conceptual similarity with the annotation categories are highlighted.

Excerpt from a review posted on Goodreads about Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-up Bird Chronicles. In between square brackets, the annotation categories that are matched to the segments in the review are stated.

The main criterion for annotating a text segment was semantic or conceptual similarity between the statements in the annotation scheme and a text segment in a review (for the complete list of annotation categories, and more information about the annotation process see Rebora et al. 2020a, 2020b). Even though absorption is clearly an experience and a term that a lot of reviewers are familiar with, in some respects there are important differences between the language used on Goodreads and the language used in the statements on the SWAS. For example, some of these statements are hard to match to sentences in reader reviews, even after adapting them to simpler language. This might indicate that the original SWAS encompasses experiences that are not very common in daily life absorption, or that people do not tend to talk about them in their reviews (e.g. T3: “The story world felt close to me” and A1: “When reading time moved differently”). Of course, context might affect what people talk about. Statements such as “My attention was focused on the book” or “I was not distracted during reading” are important in the lab as evidence that absorption took place; however, in reviews people do not tend to talk about concentration and (lack of) distractions, perhaps because these are a given in their real-life book reading situations. Rebora et al. (2020a) also found instances of absorption in reviews that simply could not be annotated using the SWAS. These instances involved reviews in which readers were talking directly to characters in their reviews, expressing their feelings for or about them. These forms of narrative play seem to indicate a high level of absorption, even when no semantic or conceptual matches with any of the SWAS statements could be found.

4 Case study

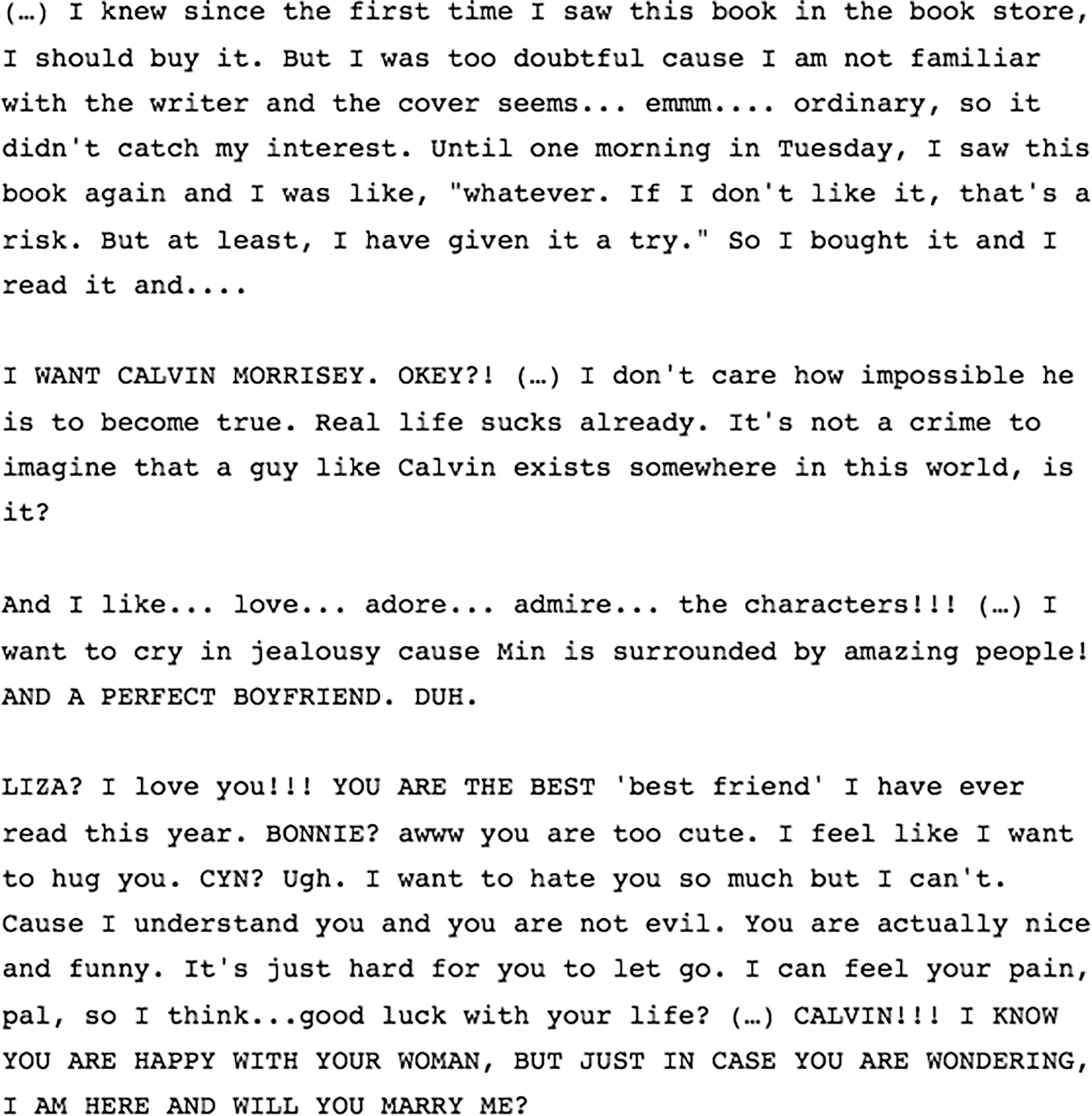

The case study central to this paper is a review of the book Bet me by Jennifer Crusie, a bestselling romance author. I have copied the case study review of this book – in Figure 2 – without specific authorship attribution.

Case study: Online review of the book Bet me.

As it is unclear whether this reviewer is under age and therefore may be unaware of the public nature of their posts, I decided to leave out their name and the first few sentences, as well as some later excerpts of the review, to protect the privacy of the original author (see Pihlaja (2017) for a discussion about anonymization in research on social media contexts, and Thomas (2020) on additional ethical issues when dealing with freely available online discourse). The review is broken up in four paragraphs, which were not originally in the review, but were added by me to make the subsequent analysis easier to follow.

This review seems to express deep levels of engagement with the book, when you understand that the names that are being used are the names of the characters in the book. The reviewer chose to show how emotionally involved they were with these characters, rather than tell us directly by explicitly using metaphors we have come to associate with absorption experiences, such as the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor.

It is clear that this review is intended for a specific sub-audience of members on Goodreads, namely those readers who have a passion for the romance or ‘chick-lit’ genres. This is clear from specific shared language use, such as the use of specific abbreviations (e.g. HEA = happily ever after), the reliance on gifs, and the generally informal way of speaking to each other and (about) the authors of the books that are reviewed. The informality of the language coincides with the sharing of personal details about their own lives (as readers). The general experiential effects that are created are tied to strong emotional feelings of admiration for the authors and for characters portrayed in the reviewed books.

5 Towards a discourse analysis approach to capture absorption in online social reader response

I will argue that this case study, without explicitly using the READING IS TRANSPORTATION metaphor, is still showing a spatially embodied understanding of the reading process by the reviewer. By applying an adapted form of Text World Theory – developed by Peplow and colleagues (2015) – which accounts for sociocultural perspectives, as well as cognitive perspectives, I will show that the progression of the review mimics the ’movement’ of the reviewer during reading. I have chosen to use Text World Theory, as it “systematically combines close stylistic analysis with wider contextual concerns, and offers a holistic approach to discourse which is particularly valuable in the examination of complex emotional and experiential issues” (Whiteley 2011, p. 25).

5.1 Text World Theory and the discourse world

Text World Theory is a discourse analysis framework that was originally developed to account for the cognitive processes involved in the production and interpretation of any linguistic communication (Gavins 2007; Werth 1999), but that has been used mostly within the field of cognitive linguistics to analyse individual readers’ interpretations of literary texts. Peplow et al. (2015) expanded on the framework to make it suitable to analyse social and interactive interpretations of literary texts within reading groups. The approach revolves around the notion of ‘text-worlds’ which are “conceptual spaces which discourse participants form to comprehend linguistic communication (…) constructed through the interaction between linguistic cues and a discourse participant’s existing knowledge (Peplow et al. 2015, p. 33)”. The context in which a text world is constructed is of great importance, as it determines which stores of background knowledge a discourse participant will need to rely on; this context is referred to as the ‘discourse world’.

When applying Text World Theory to a socially motivated text such as an online reader review, it is important to discuss the split nature of the discourse world (Peplow et al. 2015). The discourse world is inhabited both by the writer of the review, as well as the reader(s) of the review. These discourse participants are necessarily in different spatio-temporal locations, as this text is found on an online social reading platform, making the discourse world split (Gavins 2007). This means that we have to rely on the written text as our sole source of communication for analysis. However, the fact that this text is found on Goodreads does establish a common affinity space (Gee 2005) between writer and readers of the text; and this shared affinity informs what specific (shared) background knowledge is called upon. I, as a researcher (and an irregular user of Goodreads) am part of this discourse world as well, but I do not share the full extent of the background knowledge, which “determines whether [the reader] feels like an intended participant or eavesdropper in the conversations they mentally represent” (Nuttall 2017, p. 160). In the following it should be clear that I am attempting to construe what an intended participant of this communication would be able to pick up on, even though I am more of an eavesdropper.

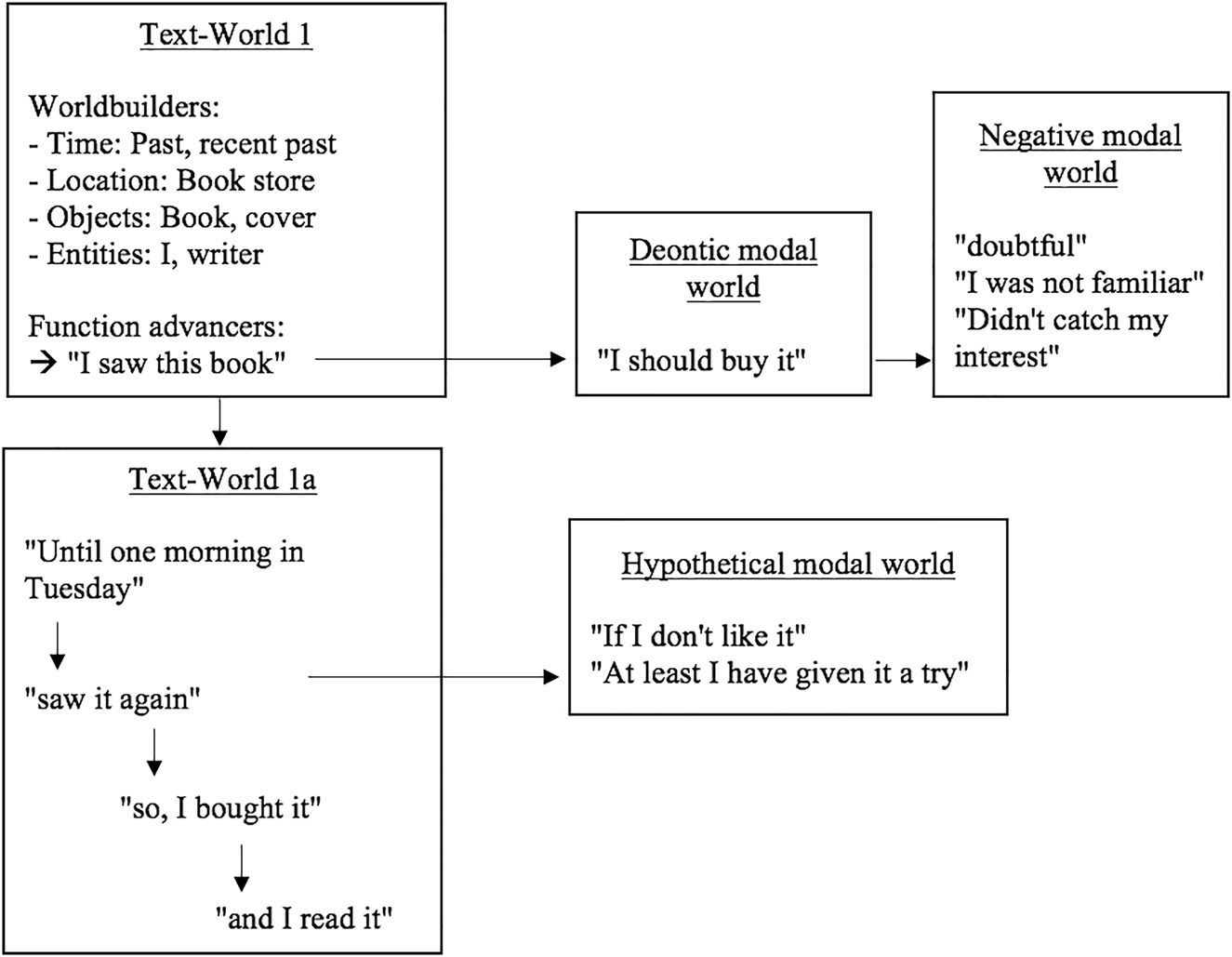

5.2 Paragraph 1: Resemblance

The first paragraph of the review establishes the usual text-world of online reviews: it reminds the reader of the shared readerly context and addresses questions about where and when the book was found, what the initial expectations were and why the reviewer decided to read it (Nakamura 2013). Figure 3 shows a schematic overview of the first text-world created in the review, which corresponds to the first section of the review. First, a couple of modal worlds are established and then a temporal world-switch – from the first to the second time the book was encountered by the reviewer – takes place, with which the reviewer is trying to convey their reluctance when first encountering the book. This reluctance may be used as a device to create impact in the review, by first distancing themselves and the reader from the narrative world, which is then contrasted with the strong emotional engagement shown in the subsequent paragraphs of the review. With this stylistic choice, the reviewer arguably attempts to recreate and convey the strong degree of impact the book had on them originally.

Text World Theory model of the first paragraph (and the first text-world) of the case study review.

It has been argued that “the closer the resemblance between the life of the text-world enactor and the life of the real-world reader, the more likely it is that the reader will be comfortable inhabiting the new projected text-world persona” (Gavins 2007, p. 86). The informal language, interspersed with punctuation to indicate pauses, serves to create the feeling of a conversation between friends, thus creating familiarity (resemblance) between reviewer and reader, making the reader feel more “comfortable” or invited, which subsequently can lead to the reader feeling immersed in the text-world created by the reviewer, or even in the story-world of the book that is reviewed. This is particularly likely if the reader of the review has also read the book that is reviewed.

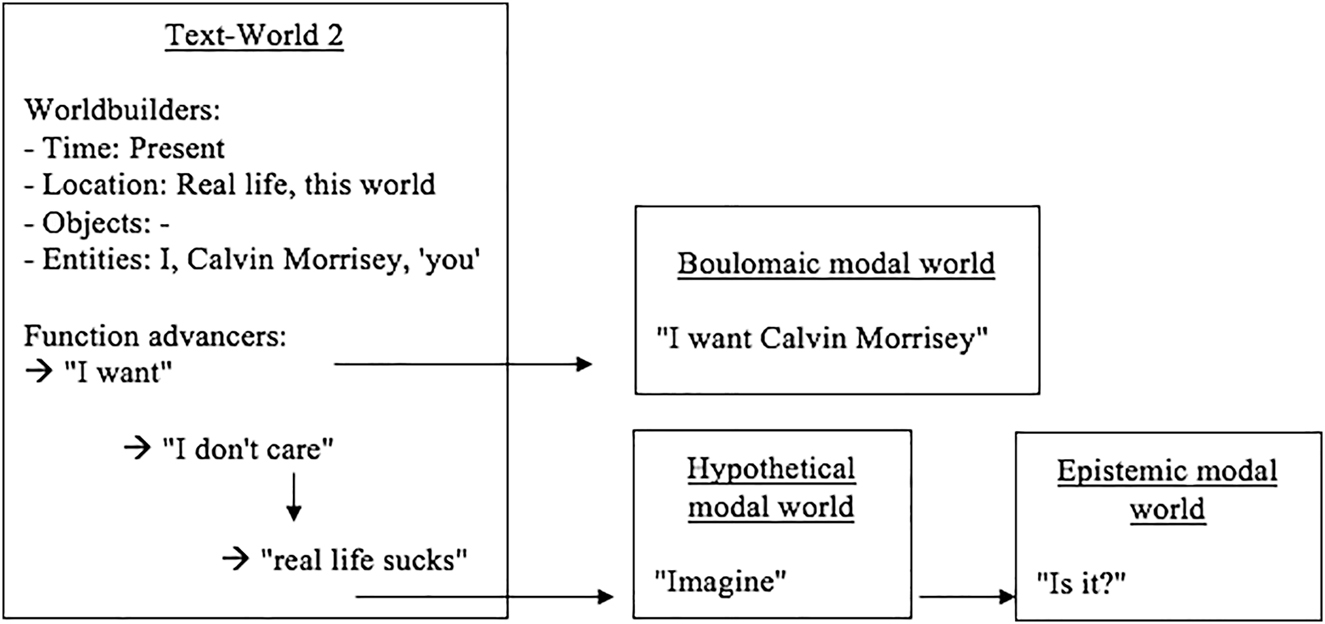

5.3 Paragraphs 2 & 3: Wishful identification and para-social responses

After the first paragraph, a world switch takes place. The clearest indicator of this is that the reviewer switches from speaking in the past tense (when they found the book) to the present tense (when they are discussing the book). Figure 4 shows a schematic overview of paragraph two of the review. In terms of location we are no longer in the bookstore, but get pulled into the reviewer’s new text-world which is marked by worldbuilders such as “real life” and “this world”. The use of these terms, juxtaposed with the name of one of the main characters “Calvin Morrisey”, signifies a distinction between story-world and real world.

Text World Theory model of the second paragraph (and the second text-world).

Here the reader is explicitly and directly addressed – “it is not a crime to imagine that a guy like Calvin exists somewhere in the real world, is it?” – reinforcing the feeling of immersion in the text-world, as started in the first paragraph by the informal language used. The reviewer uses deictic alignment (Nuttall 2017) to place themselves and the reader in the same text-world and to allow psychological projection (Gavins 2007) on the part of the reader. More interesting even is that there seems to be psychological projection on two levels simultaneously. First, the reader of the review is invited to psychologically project themselves in the same text-world as the reviewer, having a conversation about the story-world – or particular entities in that story-world. Second, the reviewer brings the character Calvin Morrisey – from the story-world of the book – into that same text-world. This leads me to believe that they had projected themselves into a text-world inhabited by Calvin while they were reading Bet me.

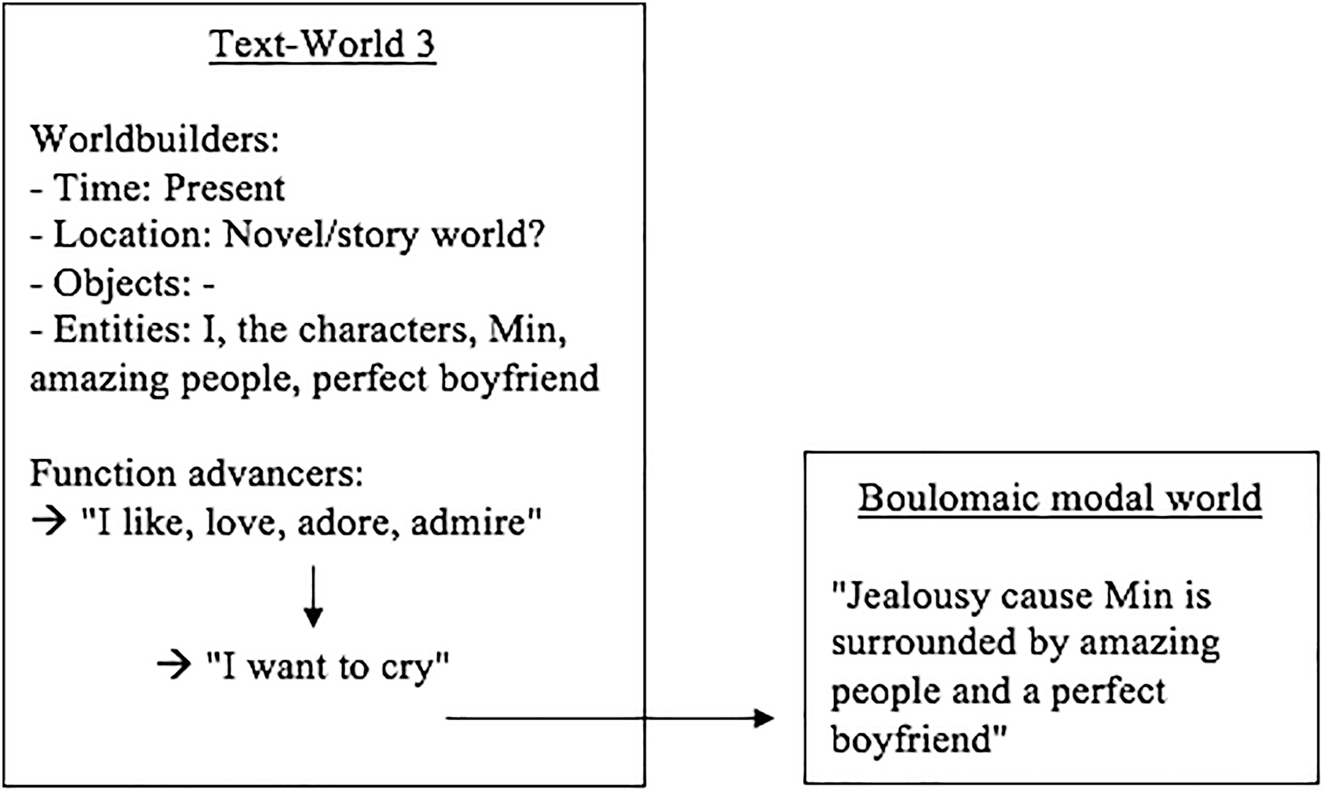

This sense of psychological projection on the part of the reviewer becomes stronger still in the third paragraph, as shown in Figure 5, where the lines between the story-world of the novel and text-world three of the review become more blurred.

Text World Theory model of the third paragraph (and the third text-world).

Here, the reviewer first expresses adoration and admiration for the characters, followed by a shift to talking about the specific character of Min, as if Min was more than just a character in a book, but rather a person with whom they shared a text-world. While the typical reader of the review and the reviewer may share some resemblance, making it easier for the reader to immerse themselves in the text-world created by the reviewer, the reviewer does not seem to be “comfortably inhabiting the text-world persona” (Gavins 2007) of Min. They instead express jealousy of Min’s relationships, which can be understood as an expression of wishful identification (Hoffner 1996) or of a desired possible self (Martínez 2014).

5.4 Paragraph 4: Proximity or presence?

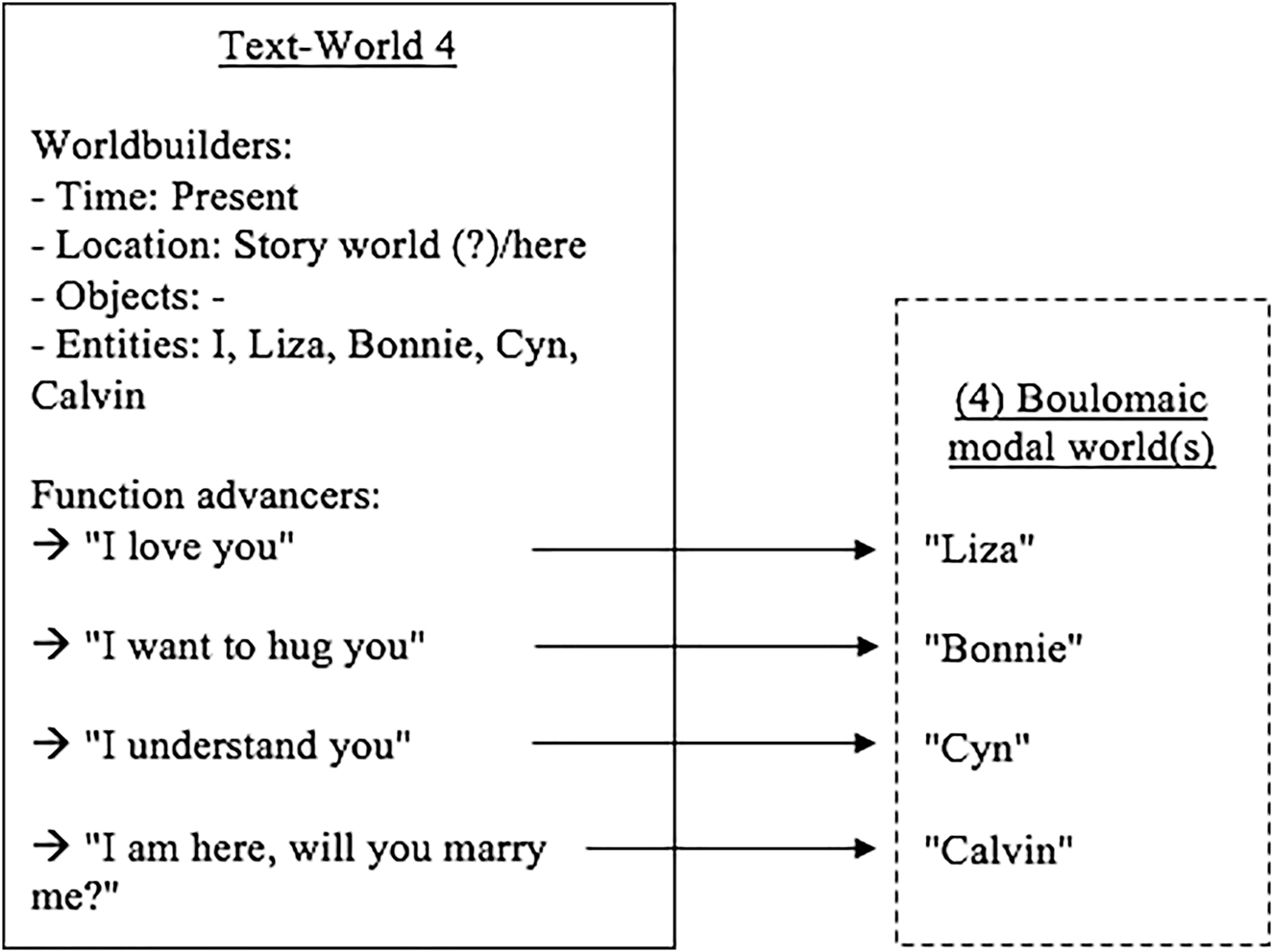

This wishful identification transforms into para-social response – “coming to know and imaginatively interact with characters” (Hoffner 1996, p. 391) – in the last paragraph of the review, shown in Figure 6. Another world-switch takes place, and it is unsure where this new text-world is situated. In the third paragraph, we could argue that the location was somewhere in the novel, as the reviewer was specifically talking about events happening in the novel. In the fourth paragraph, however, the reviewer is now addressing the characters directly by name. Other readers of the book will recognize the names of the characters, thus understanding the level of involvement on the part of the reviewer immediately. But where is this new text-world? Did the reviewer deictically project themselves into the story-world alongside the characters? This would be the perspective of narrative absorption research, where questions to participants are always formulated so as to account for the movement of the reader into the story-world and back. Using a Text World Theory approach, however, we could argue that the reviewer builds a new text-world separate from the story world in which they placed the characters of the story-world and themselves (and the readers of their review). Taking it one step further, we could argue that the reviewer made four distinct boulomaic text-worlds (i.e. modal worlds expressing desire), one for each of the four characters they are imaginatively interacting with outside of the confines of the story-world presented in the original novel. This interpretation would open up the concept of deictic shift during absorbed reading, to include not just movements from the reader into the story world, but of the reader and the characters into secondary, imaginative locations playing out narratives beyond those of the book that was read.

Text World Theory model of the fourth paragraph (and the fourth text-world).

6 Discussion

In our 2011 paper on bodily involvement in literary reading, David and I found that people who scored higher on trait absorption were more likely to report bodily feelings during reading (Kuijpers and Miall 2011). The bodily feelings that were reported by our participants were largely feelings experienced by the characters in the short story we asked participants to read. We argued that this was due to the fact that more engaged readers exchange their own feelings and bodily awareness for those of the characters they read about, implying a deictic alignment or projection on the part of the reader. The present paper added to this line of research by arguing that a reader, unprompted by a researcher, can explicitly refer to feelings of deictic shift by using embodied metaphors, or they can show their movement from one text-world to another during reading. This second manner of conveying an embodied understanding of reading, was, in the case of this review, facilitated by the social context in which it was written.

In social reading situations, such as reading groups or on social reading websites, the literary text itself is no longer “the instrument through which text-worlds are created, the literary text is instead referenced and reconstituted by the interaction” (Peplow et al. 2015, p. 37). This, according to Whiteley (2011) means that the text-worlds presented in online reader reviews cannot provide us with direct access to the text-worlds that were created during solitary reading. I have argued here that in the specific socially informed activity of writing online reviews, readers may use specific language or order their review in such a way as to mimic the progression of their reading experience. The text-worlds of solitary reading and of the review do perhaps not overlap completely, but they do intersect, as do the text-worlds of reading and reviewing, and the story-world.

I believe that this specific intersecting of text-worlds and story world is a direct result of the social context in which this reader response can be found. Because this review is part of a social discourse with other people who have read the book, this reviewer was able to express their levels of absorption by addressing the characters in the book directly. Being an avid reader, talking to other avid readers of the same genre, they were able to play with certain text features and conventions particular to this genre, to convey what their reading experience was like. This “showing rather than telling”-type of review is seen more commonly within the romance community of Goodreads, which could be an interesting avenue for further research on the topic.

Furthermore, what this case study, and the application of Text World Theory to it, has shown is that the notion of story world absorption could be extended to also include more self-oriented reader response, such as self-implication (Kuiken et al. 2004), para-social responses (Hoffner 1996) and desired possible selves (Martínez 2014). For all of these phenomena, the notion of proximity, of the reader to the story world, seems of crucial importance. However, this study has also shown that proximity can take many forms, and does not necessarily need to refer to deictic proximity (i.e. to the reader feeling transported into the story-world). Readers can feel proximity to characters in stories, by psychologically projecting themselves into a text-world alongside the characters, but separate from the story-world per se.

Of course, this paper presented only one case study and thus we should be careful in extrapolating the results and the conclusions I drew here. Nevertheless, I think that applying Text World Theory to online reader reviews provides an interesting and fruitful avenue for further research. In general, I think that what this project taught me, which I was hopefully able to demonstrate, is that it is worthwhile to keep an open mind to the application of different approaches to the same data, even during a project.

Funding source: Swiss National Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 10DL15_183194

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this paper was made possible through a Digital Lives grant (10DL15_183194 “Mining Goodreads”), from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

Boot, Peter. 2011. Towards a genre analysis of online book discussion: Socializing, participation and publication in the Dutch booksphere. In AoIR selected Papers of internet research.10.5210/spir.v1i0.9076Suche in Google Scholar

Busselle, Rick & Helena Bilandzic. 2009. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychology 12(4). 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260903287259.Suche in Google Scholar

Cordón-García, José-Antonio, Julio Alonso-Arévalo, Raquel Gómez-Díaz & Daniel Linder. 2013. Social reading: Platforms, applications, clouds and tags. Oxford: Elsevier.10.1533/9781780633923Suche in Google Scholar

Cupchik, Gerald C., Keith Oatley & Peter Vorderer. 1998. Emotional effects of reading excerpts from short stories by James Joyce. Poetics 25(6). 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-422x(98)90007-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Driscoll, Beth & DeNel Rehberg Sedo. 2019. Faraway, so close: Seeing the intimacy in Goodreads reviews. Qualitative Inquiry 25(3). 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418801375.Suche in Google Scholar

Fauconnier, Gilles. 1997. Mappings in thought and language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139174220Suche in Google Scholar

Gavins, Joanna. 2007. Text World Theory: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748629909Suche in Google Scholar

Gee, James Paul. 2005. Semiotic social spaces and affinity spaces: From the age of mythology to today’s schools. In David Barton & Karin Tusting (eds.), Beyond Communities of practice, 214–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511610554.012Suche in Google Scholar

Gerrig, Richard J. 1993. Experiencing narrative worlds: On the psychological activities of reading. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.10.12987/9780300159240Suche in Google Scholar

Goodreads. 2022. www.goodreads.com (accessed 28 March 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Green, Melanie C. & Timothy C. Brock. 2000. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79(5). 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffner, Cynthia. 1996. Children’s wishful identification and parasocial interaction with favorite television characters. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 40(3). 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159609364360.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuijpers, Moniek M. 2018. Bibliotherapy in the age of digitization. First Monday 23(10). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i10.9429.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuijpers, Moniek M., & David, Miall. 2011. Bodily involvement in literary reading: An experimental study of readers’ bodily experiences during reading. In Frank Hakemulder (ed.), De Stralende Lezer: Wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar de invloed van het lezen, 160–182. Delft: Eburon (Stichting Lezen Reeks).Suche in Google Scholar

Kuijpers, Moniek M., Frank Hakemulder, Ed S. Tan & Miruna M. Doicaru. 2014. Exploring absorbing reading experiences: Developing and validating a self-report measure of story world absorption. Scientific Study of Literature 4(1). 89–122. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.4.1.05kui.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuijpers, Moniek M., Shawn Douglas & Katalin Bálint. 2021. Narrative absorption: An overview. In Don Kuiken & Arthur M. Jacobs (eds.), Handbook of empirical literary studies, De Gruyter Reference, 279–304. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110645958-012Suche in Google Scholar

Kuiken, Don, David S. Miall & Shelley Sikora. 2004. Forms of self-implication in literary reading. Poetics Today 25(2). 171–203. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-25-2-171.Suche in Google Scholar

Lendvai, Piroska, Simone Rebora & Moniek Kuijpers. 2019. Identification of reading absorption in user-generated book reviews. In Proceedings of the 15th conference on Natural Language Processing (KONVENS 2019), 271–272.Suche in Google Scholar

Martínez, M. Angeles. 2014. Storyworld possible selves and the phenomenon of narrative immersion: Testing a new theoretical construct. Narrative 22(1). 110–131.10.1353/nar.2014.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Merga, Margaret K. 2015. Are avid adolescent readers social networking about books? New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship 21(1). 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2015.976073.Suche in Google Scholar

Miall, David S. 2006. Literary reading: Empirical and theoretical studies. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Miall, David S. 2015. The experience of literariness: Affective and narrative aspects. In Alfonsina Scarinzi (ed.), Aesthetics and the embodied mind: Beyond art theory and the Cartesian mind-body dichotomy, 175–189. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.10.1007/978-94-017-9379-7_11Suche in Google Scholar

Miall, David S. & Don Kuiken. 1994. Foregrounding, defamiliarization, and affect: Response to literary stories. Poetics 22(5). 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-422X(94)00011-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Milota, Megan. 2014. From ‘compelling and mystical’ to ‘makes you want to commit suicide’: Quantifying the spectrum of online reader responses. Scientific Study of Literature 4(2). 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1075/ssol.4.2.03mil.Suche in Google Scholar

Murray, Simone. 2018. Reading online: Updating the state of the discipline. Book History 21(1). 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2018.0012.Suche in Google Scholar

Nakamura, Lisa. 2013. ‘Words with friends’: Socially networked reading on goodreads. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 128(1). 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2013.128.1.238.Suche in Google Scholar

Nell, Victor 1988. Lost in a book: The psychology of reading for pleasure. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.10.2307/j.ctt1ww3vk3Suche in Google Scholar

Nuttall, Louise & Chloe Harrison. 2020. Wolfing down the Twilight series: Metaphors for reading in online reviews. In Helen Ringrow & Stephen Pihlaja (eds.), Contemporary media stylistics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9781350064119.0007Suche in Google Scholar

Nuttall, Louise. 2017. Online readers between the camps: A Text World Theory analysis of ethical positioning in we need to talk about Kevin. Language and Literature 26(2). 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947017704730.Suche in Google Scholar

Page, Ruth. 2017. Ethics revisited: Rights, responsibilities and relationships in online research. Applied Linguistics Review 8(2–3). 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-1043.Suche in Google Scholar

Peplow, David, Joan Swann, Paola Trimarco & Sara Whiteley. 2015. The discourse of reading groups: Integrating cognitive and sociocultural perspectives. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315850900Suche in Google Scholar

Pihlaja, Stephen. 2017. More than fifty shades of grey: Copyright on social network sites. Applied Linguistics Review 8(2–3). 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-1036.Suche in Google Scholar

Rebora, Simone, Moniek M. Kuijpers & Piroska Lendvai. 2020a. Mining Goodreads. A digital humanities project for the study of reading absorption. In Sharing the experience: Workflows for the digital humanities. Proceedings of the DARIAH-CH Workshop 2019. Neuchâtel: DARIAH-CAMPUS.Suche in Google Scholar

Rebora, Simone, Piroska Lendvai & Moniek M. Kuijpers. 2020b. Annotating reader absorption. In DH2020 book of abstracts. Ottawa: ADHO.Suche in Google Scholar

Rebora, Simone, Peter Boot, Federico Pianzola, Brigitte Gasser, J. Berenike Herrmann, Maria Kraxenberger, Moniek M. Kuijpers, Gerhard Lauer, Piroska Lendvai, Thomas Messerli & Pasqualina Sorrentino. 2021. Digital humanities and digital social reading. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36(2). 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab020.Suche in Google Scholar

Rehfeldt, Martin. 2017. Leserrezensionen als Rezeptionsdokumente. Zum Nutzen nicht-professioneller Literaturkritiken für die Literaturwissenschaft. In Andrea Bartl & Markus Behmer (eds.), Die Rezension: Aktuelle Tendenzen der Literaturkritik. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.Suche in Google Scholar

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 1991. Possible worlds and accessibility relations: A semantic typology of fiction. Poetics Today 12(3). 553–576. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772651.Suche in Google Scholar

Segal, Erwin M. 1995. Narrative comprehension and the role of deictic shift theory. In Deixis in narrative: A cognitive science perspective, 3–17. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Suche in Google Scholar

Spilioti, Tereza & Caroline Tagg. 2017. The ethics of online research methods in applied linguistics: Challenges, opportunities, and directions in ethical decision-making. Applied Linguistics Review 8(2–3). 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-1033.Suche in Google Scholar

Stockwell, Peter. 2019. Cognitive Poetics: An Introduction. New York: Taylor and Francis.10.4324/9780367854546Suche in Google Scholar

Stockwell, Peter. 2020. Texture – A cognitive aesthetics of reading. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Swann, Joan & Daniel Allington. 2009. Reading groups and the language of literary texts: A case study in social reading. Language and Literature 18(3). 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947009105852.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomas, Bronwen. 2020. Literature and social media. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315207025Suche in Google Scholar

Vlieghe, Joachim, Jaël Muls & Kris Rutten. 2016. Everybody reads: Reader engagement with literature in social media environments. Poetics 54(February). 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2015.09.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Werth, Paul. 1999. Text worlds: Representing conceptual space in discourse. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Whiteley, Sara & Patricia Canning. 2017. Reader response research in stylistics. Language and Literature 26(2). 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947017704724.Suche in Google Scholar

Whiteley, Sara. 2011. Text World Theory, real readers and emotional responses to the remains of the day. Language and Literature 20(1). 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947010377950.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: the art of sweet persuasion. David Miall’s life and work

- Articles

- The affective allure – a phenomenological dialogue with David Miall’s studies of foregrounding and feeling

- Frame shifting and fictive motion in Shelley’s poetic sublime

- Bodily involvement in readers’ online book reviews: applying Text World Theory to examine absorption in unprompted reader response

- Mind-modelling literary personas

- Operationalizing perpetrator studies. Focusing readers’ reactions to The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell

- Book Review

- Virdis, Daniela Francesca, Elisabetta Zurru & Ernestine Lahey,Language in place: stylistic perspectives on landscape, place and environment

- Postscript

- Postscript Mark J. Bruhn

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: the art of sweet persuasion. David Miall’s life and work

- Articles

- The affective allure – a phenomenological dialogue with David Miall’s studies of foregrounding and feeling

- Frame shifting and fictive motion in Shelley’s poetic sublime

- Bodily involvement in readers’ online book reviews: applying Text World Theory to examine absorption in unprompted reader response

- Mind-modelling literary personas

- Operationalizing perpetrator studies. Focusing readers’ reactions to The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell

- Book Review

- Virdis, Daniela Francesca, Elisabetta Zurru & Ernestine Lahey,Language in place: stylistic perspectives on landscape, place and environment

- Postscript

- Postscript Mark J. Bruhn