Abstract

This paper analyses the alternation between complement clauses with and without complementizer (syndetic and asyndetic), in historical Spanish (15th–18th century). While previous studies have shown that this syntactic alternation was regulated by the degree of integration of the clauses, its stylistic distribution is understudied. In this paper we investigate whether the syndetic/asyndetic alternation is governed by socio-stylistic factors (discourse traditions, audience and speaker design). The analysis of the data from the corpus CODEA+2015, is carried out by using regression models. Our results indicate that the selection of asyndetic complements was predicted by the type of audience (reactive style-shift), employed especially when addressing superiors. Also, asyndetic complements were favored by the use of deferential request verbs such as suplicar (‘to beg’) that represents the petitioner as an inferior (proactive style-shift). Furthermore, the stylistic choice for an asyndetic complement was determined at the sentential level (“micro” discourse traditions), when the writer is also the performer of the speech-act. Thus, we show that in choosing alternative variants, writers are concerned with expressing grammatical meanings but also social identity. Additionally, the diachronic analysis indicates that while the proactive style-shift effect grows stronger over time, the relevance of the reactive style-shift declines, showing that socio-stylistic predictors, similarly to linguistic predictors, can be affected diachronic fluctuations. Our paper evinces the relevance of a multidimensional and diachronic approach to the study of syntactic variation, demonstrating how a monolithic view of the textual dimension can hide fine-grained socio-stylistic effects.

1 Introduction

Finite complementation in Spanish is usually introduced with an explicit complementizer que ‘that’, as in (1a), which can be called syndetic complementation. Alternatively, a complement clause can be introduced asyndetically, i.e., without the complementizer que ‘that’, as shown in (1b).

| Le-s | rog-amos V1 | que | disculp-en V2 | la-s |

| dat-pl | beg-prs.1pl | comp | pardon-sbjv.prs.3pl | det.f-pl |

| molestia-s. | ||||

| inconvenience-pl | ||||

| Le-s | rog-amos V1 | Ø | disculp-en V2 | la-s |

| dat-pl | beg-prs.1pl | pardon-sbjv.prs.3pl | det.f-pl | |

| molestia-s. | ||||

| inconvenience-pl | ||||

| ‘We kindly beg you to forgive the inconveniences.’ | ||||

In present-day Spanish, asyndetic complementation is restricted to verbs of volition and request. Moreover, this variant is highly marked from a stylistic point of view, as it appears mainly in written formal registers (Espinosa Elorza 2014; Girón Alconchel 2005; Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga 2014; Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española 2009). Historically speaking, asyndetic complementation was one of the most salient syntactic features of classical Spanish (16th–17th century). In contrast with today’s language, asyndetic complementation used to occur both with subjunctive and with indicative complement clauses, and with a wider range of complement-taking predicates. Thus, examples such as (2) are uncommon in modern Spanish.

| […] | don Francisco Gris | dij-o V1 | a-l | testigo |

| Mr. Francisco Gris | say.pst.pfv-3sg | to-det.m.sg | witness |

| Ø | ten-ía V2 | que | delat-ar | al |

| have- ind .pst.ipfv.3sg | that | denounce-inf | acc-det.m.sg |

| reo | por | cosa-s | de molinista. | |

| defendant | for | thing-pl | of molinist | |

| ‘Mr. Francisco Gris said to the witness he had to denounce the defendant for molinist issues.’ (CODEA-2140, Cuenca, 1729) | ||||

The alternation between clauses with and without the introducing element que does not appear to produce any difference in meaning. Consequently, syndetic and asyndetic complementation are “alternate ways of saying ‘the same’ thing” (Labov 1972: 188). In Mazzola et al. (2022), the selection of these competing variants between the 15th and 18th century was shown to be regulated by language-internal factors related to the degree of integration of main and subordinate clauses (Givón 2001): usage of asyndetic complements, in particular, was strongly favored by a high degree of integration between the main clause and the subordinate clause. However, previous accounts fail to explain the relationship between those language-internal constraints and socio-stylistic motivations in the selection of one or the other variant. It is unclear whether these probabilistic constraints can be said to result from the same underlying principle or represent fundamentally different types of constraints.

In this paper we investigate the question to which degree the alternation between the syndetic and asyndetic clauses is also governed by social and stylistic factors, such as textual genre, document setting, discourse traditionality or audience/speaker design. We present a real-time and a diachronic study of the alternation between syndetic and asyndetic complementation in a corpus of documents written between the 15th and 18th century (GITHE 2015). Using mixed-effect logistic regression models, we examine the interactions between semantic, pragmatic, social and stylistic factors in a sample of n = 3,706 complement clauses, and we analyze whether their effect changes over time.

Our results indicate that, while the alternation between syndetic and asyndetic complementation can be described in terms of probabilistic language-internal constraints, these constraints are mediated by pragmatic, social and stylistic motivations. In doing so, we demonstrate that existing textual classifications (such as textual typology and formality) are insufficient to fully capture the stylistic motivations behind the selection of these alternative syntactic options. Rather, we advocate for an approach that considers the social motivations for the writers to use a certain style and the internal heterogeneity of each document studied, inspired by the concepts of Audience Design (Bell 1984, 2001) and “macro” and “micro” Discourse Traditions (Kabatek 2013; Mazzola et al. 2022).

Application of these concepts shows that the syntactic alternation under study has social meaning. In choosing between syndetic and asyndetic complementation, writers are concerned not only with expressing lexical and grammatical meanings, but also with expressing their social identity which is highly influenced by the situational context and by the relationship between speakers and their audience. While the use of asyndetic complementation is favored in requests, we find that writers favor the usage of this variant even more when this request is addressed to a prestigious audience, which has more social power than the petitioner. However, the relevance of the request speech acts grows in diachrony, while the importance of the social power as a predictor first increases and then declines.

Finally, our results indicate that the stylistic constraints that regulate the alternation are mostly relevant at the level of “micro” Discourse Traditions: asyndetic complements are not selected on the basis of the audience of the document as a whole, but are rather promoted at the sentential level when the writer is the performer of the speech act. This is why, macro-textual approaches so far have failed to reach convincing conclusions. Our paper thus evinces the relevance of a multidimensional approach to the study of syntactic variation, demonstrating how a monolithic view of the textual dimension can hide more fine-grained stylistic and social effects.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 summarizes previous research on the syndetic/asyndetic alternation in Spanish from the linguistic and stylistic point of view. Section 3 presents the limitations of traditional textual classifications and categories, and introduces the theoretical frameworks of Audience/Speaker Design and Discourse Traditions, as well as the hypothesis and research questions investigated in this paper. Section 4 describes our corpus, the method and the operationalization of variables. The results of the corpus study are presented in Section 5 and discussed in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 closes the paper with the conclusions of the present study.

2 Linguistic and stylistic predictors of asyndetic complementation

2.1 Linguistic predictors

Previous historical accounts of Spanish complementation patterns maintain that asyndetic complementation started spreading in the 15th century and became particularly frequent in the 16th and 17th century (Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2016; Pountain 2015). Mazzola et al. (2022) show that, until the end of the 18th century, the construction is still very popular and closely competing with the syndetic variant, which is in line with other studies that document the phenomenon as late as the beginning of the 19th century (Girón Alconchel 2005; Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga 2014). García Aguiar (2020), who studies a corpus of municipal documents, even registers an increase of the asyndetic variant between the second half of the 18th and at the beginning of the 19th century.

To date, several studies suggest that the alternation between syndetic and asyndetic clauses is regulated by a number of language-internal factors, such as the semantics of the main verb, the mood of the complement clause, the distance between the verbs, and the subordination of the main verb in a relative clause (cf. i.a. Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2018; Delbecque and Lamiroy 1999; Folgar Fariña 1997; García Aguiar 2020; Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga 2014; Pountain 2015; Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española 2009).

In Mazzola et al. (2022), we used Szmrecsanyi’s (2013) diachronic probabilistic grammar to investigate the syntactic alternation on the basis of documents produced between the 15th and 18th century. Our study largely confirmed previous claims in the literature, but also highlighted new aspects of the alternation between these complement types. On the basis of an analysis of a dataset containing five verbs from different semantic classes (fitted as random effects), we identified a number of language-internal constraints relevant to the alternation between syndetic and asyndetic clauses. Asyndetic clauses are more likely predicted by complex sentences like (3), where: (i) the indirect object of the main clause (nos ‘to us’) is coreferential with the subject of the subordinate clause (tornemos ‘we return’); (ii) the complement subject is implicit (i.e., morphologically coded by the first person plural inflection of the verb, but not expressed by an explicit NP or pronoun); (iii) the complement verb is inflected in subjunctive mood. These morphosyntactic characteristics largely coincide with the syntactic schema of what Givón (2001: 44) called “non-implicative manipulation verbs”, typically instantiated by verbs of request and order. The non-implicative manipulation schema is characterized by a high semantic and syntactic integration between main and subordinate clause. We therefore concluded that asyndetic clauses signal an advanced syntactic integration of finite clauses.

| […] | en | cumplimiento | de | la | comisión | de | vuestr-a |

| in | compliance | of | det.f.sg | order | of | poss.2sg |

| señoría | en | que | se | nos | mand-a V1 | Ø | |

| lordship | in | rel | imprs | dat.1pl | order-prs.3sg |

| torn-emos V2 | a rebe-r | est-a-s | ordenanza-s | de los | |||

| return-sbjv.prs.1pl | to review-inf | dem-f-pl | ordinance-pl | of det.m.sg | |||

| pastelero-s | […] | ||||||

| baker-pl | |||||||

| ‘In compliances with Your Lordship order in which it has been ordered to us to review the ordinances regarding the bakers.’ (CODEA-1390, Granada, 1625) | |||||||

Additionally, our paper evinces that usage of the asyndeton is strongly favored by the presence of an impersonal se-construction, the adjacency between the predicates and when the main clause is embedded in a relative clause. According to our (2022) study, an example such as (3), that contains all the mentioned features, is prototypical for asyndetic complementation in the classical period.

More importantly, our study showed that the relevance of some of these constraints increase diachronically. Asyndeton became more strongly associated with some specific schemas (coreferentiality of the indirect object, se-constructions and proximity of verbs), which indicates that, in spite of the fact that we did not find a demise of the construction until the end of the 18th century, the construction started to be used in more restricted and specific contextual environments, which might have eventually led to the less productive and more marked use of the asyndeton in Present-day Spanish.

2.2 Stylistic distribution of asyndetic complementation

It is often claimed that the asyndetic pattern developed in Spanish around the 15th century as a syntactic calque, triggered by the prestige of Classical Latin and mediated through the model of Italian, where the conjunction che was omitted not only from complement clauses, but also from relative clauses and comparative constructions (Meszler and Samu 2009; Wanner 1981). This hypothesis is corroborated by Pountain (2015: 79), who notices that, already from the start, the Spanish asyndeton appeared in more contexts than in Classical Latin, where it typically occurred with some specific volitional predicates (4), and some impersonal verbs (5) (cf. Del Rey Quesada 2017; Schulte 2007).

| Ill-ud | vōl-o | fac-iās | |||||

| that-acc.sg | want-ind.prs.1sg | do-sbjv.prs.2sg | |||||

| ‘I want you to do that.’ | |||||||

| (apud Schulte 2007: 76, from Augustinus Hipponensis: Verbum Dei mandatum Patris 6: Aequalitas Filii cum Patre.) | |||||||

| Animum | quoque | relax-ēs | oport-et |

| soul.acc.sg | also | relax- sbjv.prs.2sg | be.proper-ind.prs.3sg |

| ‘It is also proper for you to relax.’ | |||

| (apud Schulte 2007: 75, from Cicero, De Re Publica I, 14) | |||

In line with the idea that the asyndetic construction in Spanish is a learned calque, it has been described as a stylistic marker of formal register, e.g., typical of juridical and administrative genres, as well as literary genres (Barraza Carbajal 2014; Benot 1991; Espinosa Elorza 2014; Girón Alconchel 2005). Yet, some other scholars argue that asyndetic complementation originated as a feature of the language of communicative immediacy, typical of colloquial and private epistolary communications (Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2016; Fernández Alcaide 2009; Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga 2005; Keniston 1937a). According to Pountain (2015), asyndetic complements with the verb rogar ‘to beg/pray’ appear more often in dialogues and religious works. Furthermore, it has also been considered an idiolectal stylistic feature of some authors (Folgar Fariña 1997; Keniston 1937b; Octavio de Toledo y Huerta 2011; Pountain 2015).

It is worth mentioning that most of the literature reviewed here shows methodological limitations on several levels. Most studies address the topic by adopting a merely descriptive approach (Barraza Carbajal 2014; Espinosa Elorza 2014; Pountain 2015), or do not provide any statistics at all (Girón Alconchel 2005; Herrero Ruiz de Loizaga 2005). Other analyses only look at one textual genre (e.g., Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2016; Fernández Alcaide 2009; García Aguiar 2020) or are based on only one main predicate (rogar ‘to pray’ in Pountain 2015; creer ‘to believe’ in Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2016).

In terms of methodology, Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles’s (2016, 2018 present a convincing multidimensional approach to the study of complementation, combining language-internal and -external factors. Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles (2016) is the only study that takes into account sociolinguistic variables, such as the solidarity between sender and recipient of the letter, and the social rank of the writers. Their results show that the rise of asyndetic complements can be considered a “change from below”, which spread from the lower ranks of the society towards the higher social groups. Moreover, they examine the type of audience of the letters, showing that asyndetic constructions with creer are mainly used in epistolary exchanges between equals. These results are in sharp contrast with the idea that asyndetic complements are a “learned” syntactic calque due to the influence of Latin and Italian. Probably, the conclusions of Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles (2016) are imputable to the composition of their dataset, which, as mentioned, includes only private letters and complement clauses dependent from the epistemic verb creer ‘to believe’.

In this paper, we maintain that in order to study this syntactic alternation and to clarify the role of sociolinguistic variables we need to analyze a broader dataset, which includes different classes of main verbs and a wider range of textual types.

3 Socio-stylistic variables and the alternation of syntactic variants

3.1 The limitations of a traditional approach to textual variation

Many corpus-based studies of linguistic (especially grammatical) alternations have shown that the selection of alternative grammatical variants is determined by probabilistic language-internal constraints (e.g., Cuyckens et al. 2014; Mazzola et al. 2022; Rosemeyer 2014; Shank et al. 2016), but it has also been demonstrated that “language users do indeed adjust their choice-making processes to the situational context” (Szmrecsanyi 2019: 15–16), i.e., grammatical variants are often selected due to the influence of language-external factors, such as register, genre and style.

A classical textual approach to grammatical alternations such as the syndetic/asyndetic alternation is to extract a sample of the relevant variable contexts (finite complement clauses with or without complementizer) and to analyze their distribution according to textual categories. With this approach, one would measure the proportional selection of one or the other variant within each textual type. For our case study, such an approach would yield the percentages of syndetic and asyndetic complements, calculated from the total of the complements in each textual type, similarly to the analyses proposed, for instance, in Pountain (2015) and Yoon (2015).

One of the first problems that the analyst encounters in such a study, however, is how to define the different textual categories. Typically, variationist studies make use of the concepts of register, genre and style (RGS), but very often the distinction between the three concepts is blurred (cf. discussion in Rosemeyer in press; Szmrecsanyi 2019). In the end, regardless of terms and definitions, most corpus-based studies analyze RGS variation by relying on the categories offered by the existing corpora. For instance, consider a corpus frequently employed in the study of Spanish historical linguistics such as the CODEA+2015 (GITHE 2015). In this corpus the documents are classified according to three parameters:

Setting (ámbito) in which the document was produced: Diplomatic, Juridical, Municipal, Ecclesiastic and Private.

Textual typology, established by the CHARTA research group (Corpus Hispánico y Americano en la Red: Textos Antiguos), which consists of Deeds and Declarations, Trade Letters and Contracts, Private Letters, Certificates, Charters, Reports, Notes and Briefs,[1] Wills and Inventories, and Laws.

Diplomatic typology: the traditional philological classification of historical documents (cartas plomadas, cartas de poder, notas de abandon, privilegios rodados, etc. …).

The variable of setting is considered by the developers of CODEA+2015 to be a proxy of formality (thus corresponding roughly to the concept of register), where the highest degree of formality is represented by the diplomatic setting and the lowest by the private setting, as illustrated in (6).

| Diplomatic > | Juridical > | Municipal > | Ecclesiastic > | Private |

| Formal_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Informal | ||||

The variable of textual typology represents the concept of genre, i.e., “the conventional structures used to construct a complete text” (Biber and Conrad 2009: 2). The third variable, diplomatic typology, is a finer and more descriptive classification of the genre of the documents, compared to the textual typology, with many categories and subcategories, which is useful to have a more precise idea of the nature of the documents, but it lacks internal homogeneity and it is too fragmented to be used to measure proportions meaningfully.

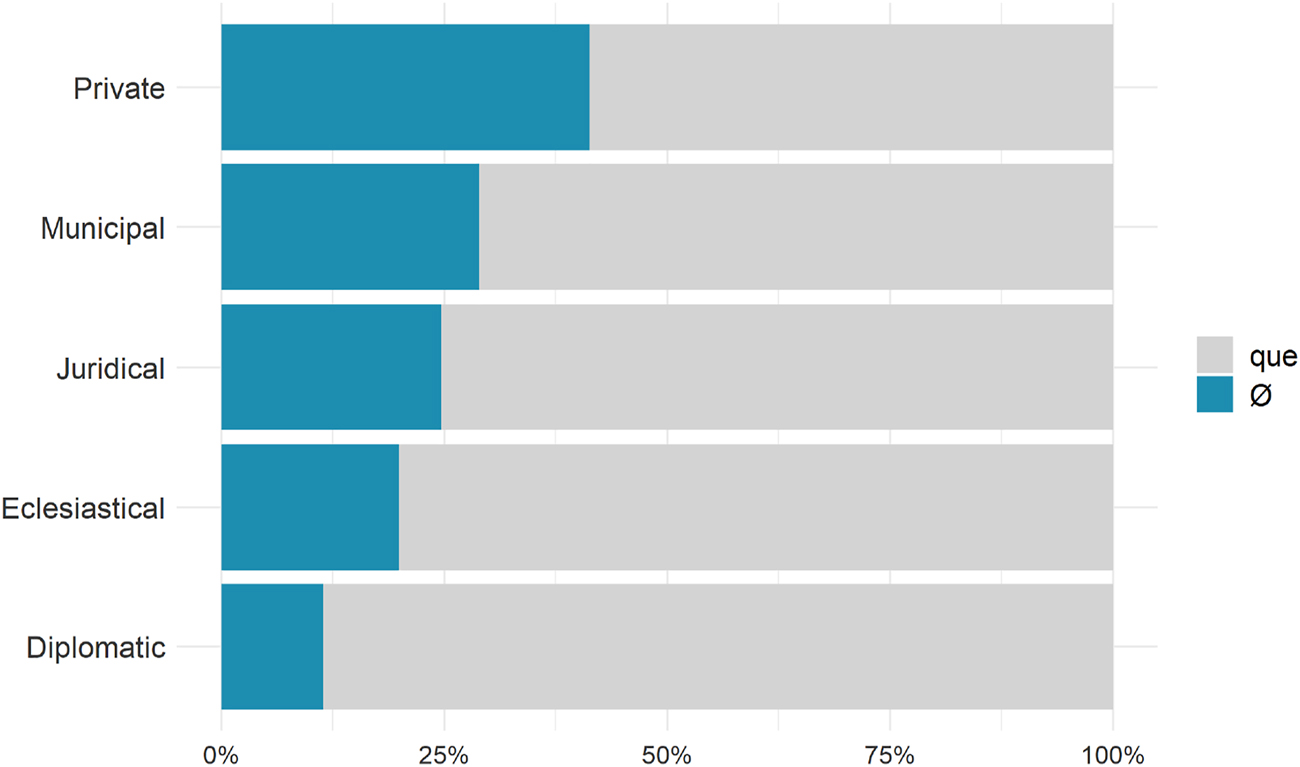

The relative distribution of the syndetic/asyndetic alternation in terms of setting suggests that asyndetic complements are selected more often in informal settings (Figure 1).[2] In line with the formality scale presented in (6), and the assumption that the syndetic-asyndetic alternation is governed by formality, we would expect the Ecclesiastical setting to be more similar to the Private setting. In contrast, asyndetic frequencies in this setting are found to approximate the Diplomatic setting. In other words, while the distribution of these complementation types is quite clear and easily interpretable for the two opposite poles of the formality proxy (i.e., Private and Diplomatic), intermediate levels show mixed results, which are less easily explained. In addition, the formality scale as such can be criticized. One might wonder why the documents produced in the Ecclesiastical setting are necessarily less or more formal than the ones produced, for instance, in the Municipal setting, given that the formality does not only depend on the setting of production (register), but also on the content and the purpose of the communication, as well as on the relationship between the writer and the addressee (genre and style).[3]

Percentages of que versus Ø according to the variable of setting. 3

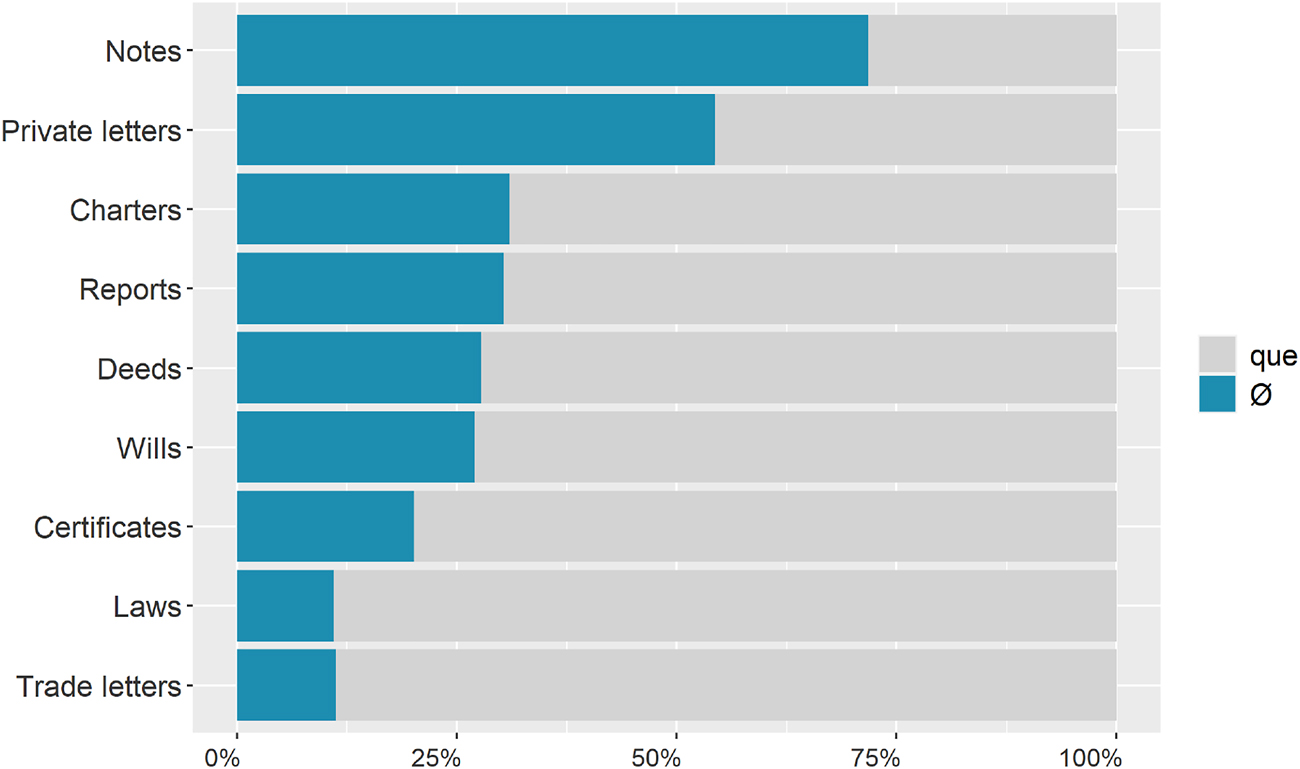

The variable textual typology presents a similar problem (see Figure 2). In Notes and Private letters, asyndetic complements outnumber syndetic ones. In contrast, asyndetic complements only occur in 10% of the cases in Laws and Trade letters. The rest of the textual types exhibit an in-between pattern of selection, where usage of asyndetic complement clauses averages 25.6%. These textual types are mostly administrative documents, which are used to regulate relationships between private individuals (e.g., Wills), or between individuals and institutions.

Percentages of que versus Ø according to the variable of textual typology. 4

On the basis of these descriptive results, we are in a position to claim that the use of asyndetic complements is favored by private communications and especially epistolary texts (in line with the conclusions Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles 2016). However, such an analysis would fail to account for all those textual categories and document settings which show a relevant, but less prominent, amount of asyndetic complements, such as administrative documents or texts associated with the Municipal and Juridical setting.

The problems regarding the interpretation of these results highlight the need for the analysis of explanatory variables that can account for the distribution of the two complementation patterns, as well as a more fine-grained methodological approach towards the description of the influence of these variables. Thus, we expect that the unclear or insufficient results found in the literature (and in this paragraph) are due to the use of macro-textual categories, which are too generic to capture the essential factors that determine variation. Crucially, in this paper we will present other relevant variables that are “diluted” in these macro-textual categories, and measure their effects on the syntactic alternation from a panchronic and a diachronic perspective. We will focus particularly on stylistic and social factors and their interactions, under the light of the Audience/Speaker Design framework, and the concept of Discourse Traditions.[4]

3.2 Syndetic/asyndetic alternation and audience design

Having shown the limitations of traditional textual classifications, in this section we formulate the hypothesis that the type of audience of the text is a better stylistic variable for the syndetic/asyndetic alternation.

Our analysis starts from the assumption that asyndetic complements are a marked variant, and probably an innovation “from above”, a Latinate calque perceived as a prestigious variant (cf. Section 2.2). Octavio de Toledo y Huerta (2011) demonstrates that this is the case in Santa Teresa de Ávila’s Camino de perfección (of which the first autograph text was written around 1562).[5] Santa Teresa edited a second version of the text in 1569, in order to address it to a broader, more prestigious and less familiar audience. In this attempt of intensive linguistic elaboration, she made some linguistic modifications to the manuscript. Among these, she eliminated many instances of the complementizer que. Octavio de Toledo y Huerta’s results lead us to expect asyndetic complements to typically appear in texts characterized by an elegant and prestigious language style. This expectation contrasts with Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles’s (2016) claim that the construction came about as a change “from below”, and that it was mainly used in communications among equals about private issues, as mentioned earlier (Section 2.2). In spite of their conflicting claims, both works suggest that the type of audience might be a relevant explanatory variable for the selection of a specific complement type.[6] This is what we will further explore in this article.

Building on this idea, we assume that the selection of alternative grammatical options is a strategy that language users employ to fine-tune the style of their communication, in order to adapt the components of linguistic production to the conditions of communication (cf. Koch and Oesterreicher 2012). In this view, by virtue of their selection of different grammatical and lexical variants, speakers and writers are “potential agent[s] of choice” (Johnstone 2000: 417), who select linguistic variants and varieties in order to convey a particular type of identity or social meaning through a linguistic performance. This approach to speaker’s agentivity and stylistic variation is tightly bound to recent accounts of the concept of style in sociolinguistics, especially in the framework of Audience and Speaker Design.

Audience Design (Bell 1984, 2001), a concept inspired by Speech Accommodation Theory (Giles and St. Clair 1979), defines style as what an individual does in relation to other people (Bell 2001: 141). Style marks interpersonal and intergroup relations, in so far as style-shifting is mainly designed in response to an audience (i.e., it is “reactive”). Bell’s work highlights that audience-driven style-shift affects grammatical, lexical and pragmatic options, and even language and dialect shifts. Moreover, audience design effects can be observed through a quantitative style-shift: “a speaker’s style will be amenable to counting the relative frequency of certain variants” (Bell 2001: 166).

The model of Speaker Design builds on this idea and expands the theory of stylistic variation by conceiving style as a multidimensional phenomenon. In this view, stylistic variation and style-shifting include a wide range of co-occurring internal (purpose, key, frame, etc.) and external (audience, topic, setting, age, familiarity, etc.) parameters which customize people’s speech (cf. Coupland 2007; Hernández-Campoy 2019; Johnstone 2000; Schilling-Estes 2013). This framework does not exclude the validity of the Audience design approach, but insists on the importance of speakers’ identity construction by means of their linguistic choices. Thus, style-shifting is not only about reacting to an audience: it is a “proactive” rather than a merely reactive phenomenon, which considers speech as performance, as a way for the speaker to project different roles and identities according to the circumstances (cf. Hernández-Campoy 2019: 11).

In line with these frameworks, and similarly to what has been observed by Octavio de Toledo y Huerta (2011) about Santa Teresa’s work, we can formulate the hypothesis that the choice of a marked stylistic variant (such as the asyndetic complement clauses) is due to the type of audience addressed, and the type of role and social identity that writers want to represent. In particular, we will focus on the role played by the mutual relationship between writer and addressee in terms of social power (addressee status, explained in detail in Section 4.3),[7] and the communicative goals of the writer.

3.3 Macro and micro discourse traditions

As mentioned earlier, the models of Audience and Speaker Design suggest that style is multidimensional, and that each of the individual factors of variation is highly intertwined with other factors (e.g., purpose, frame, topic …). With the purpose of capturing this complexity, this paper examines the stylistic distribution of the asyndetic complement clauses in 15th–18th century Spanish by considering the concept of Discourse Traditions (Kabatek 2005; Koch 1997; Schlieben-Lange 1983).

The central idea behind the concept of Discourse Traditions (henceforth DTs) is that language is not a monolithic homogenous object, but an aggregate of subsystems, i.e., the texts with their organizations and their traditions. As stated in Kabatek (2018: Ch. 7), it is virtually impossible to say anything about the “state of a language X” in a given period. Rather, what an analyst should do is to account for the wide spectrum of textual possibilities of that language in that period. In this view, to investigate language variation and language change, the discourse-textual dimension must be considered, as language change takes place and spreads through DTs (Kabatek 2013, 2018: Ch. 7).

Additionally, Kabatek (2018: 158) notes that even the textual dimension itself is not monolithic, as each text can contain multiple DTs internally at various levels (so-called “horizontal heterogeneity”). The fact that texts can allow for multiple global or internal classifications (Kabatek 2018: 156) explains why global a priori classifications, such as textual types and genre, are very often not sufficiently powerful to explain language variation (as demonstrated in Section 3.1). Rosemeyer (in press) approaches to the idea of the multi-layered nature of DTs, arguing that most of the current studies only deal with “macro” DTs (which roughly correspond to the notion of RGS), while largely neglecting the importance of “micro” DTs, because of the difficult operationalization of multi-layered textual categorization. Here, we would like to account for DTs by taking into account both the macro and the micro level.

The selection of alternative grammatical options by the speaker/writer is obviously a matter of choice-making. In fact, according to the DTs framework: “[…] speakers will make their choices of grammatical variants according to the textual tradition they wish to represent” (Kabatek et al. 2010: 7). This view of speaker’s agentivity is, hence, compatible with the above-mentioned framework of Audience and Speaker Design.

Moreover, the complementation variants analyzed here are particularly interesting to study variation across DTs, as clause linkage techniques are known to be indicators of the position of a text along a continuum between the poles of Communicative Immediacy and Distance[8] (Kabatek et al. 2010; Raible 2001). Thus, we investigate the hypothesis of whether the selection of syndetic versus asyndetic complementation is influenced by the characteristics of different DTs.

What is more, we will distinguish between macro and micro DTs, in order to investigate whether stylistic effects are active at the global textual level or rather at the sentential level. One possibility is that the use of an asyndetic clause can be explained by stylistic constraints at the textual level, e.g., it is frequently found in any type of sentence within documents that were addressed to a superior addressee. Another possibility is that the presence of an asyndetic clause is not strictly predicted by the audience of the document as a whole, but rather by the audience of a specific sentence, for instance if it is only found in sentences where the issuer is directly addressing the recipient. The former scenario would represent an effect at the level of macro DTs, while the latter would mean that stylistic constraints that regulate the syndetic/asyndetic alternation are active at the level of micro DTs. With this aim in mind, we will introduce the variables of Main Verb (see Section 4.5 ) and its morphological Person (see Section 4.4 ), to analyze DTs also at the sentential level.

4 Analytical approach

4.1 Data

The data used for this study are drawn from a dataset originally extracted in a pilot study by Cornillie and Rosemeyer (2018), from the corpus CODEA+2015 (GITHE 2015). This corpus contains archival documents, from a wide range of geographical areas, and it is a particularly trustful source from a philological point of view, as it is a “primary” corpus, which means that the same research group (GITHE) is responsible for the edition of the documents and for building the corpus.

The dataset encompasses a time range stretching from the 15th to the end of the 18th century and includes n = 1,090 documents produced in Spain. The texts belong to the document types and settings indicated in Section 3.1. We extracted 46 Complement-taking Predicates (CTPs) identified as amenable to asyndetic complementation in Pountain (2015) by means of regular expression. The dataset was manually cleaned to reduce the sample to the variable context: CTPs + (que/Ø) + finite complement clause. The resulting sample was manually coded at the sentential level so as to detect semantic and morphosyntactic characteristics of the complex clause (cf. Mazzola et al. 2022).

For the present study, we included all observations with a main verb occurring at least 40 times in the sample, followed by an object complement clause. These elimination procedures yielded a final sample of n = 3,706 complement clauses, n = 2,715 syndetic and n = 991 asyndetic. As shown in Table 1, the final dataset used for this study contains n = 967 documents belonging to nine textual types (seen in Figure 2), which adds up to a total of n = 723,779 words. Each of the documents was coded in order to annotate the relationship between writer and speakers (see Section 4.3).

Number of documents and words by textual type.

| Textual Typology | N. documents | N. words |

|---|---|---|

| Deeds | 227 | 172,426 |

| Certificates | 69 | 51,780 |

| Charters | 6 | 11,453 |

| Laws | 135 | 168,615 |

| Notes | 39 | 2,289 |

| Private letters | 249 | 76,233 |

| Reports | 60 | 35,120 |

| Trade letters | 122 | 134,088 |

| Wills | 60 | 71,775 |

| Tot. | 967 | 723,779 |

4.2 Mixed-effect logistic regression

Given that we were interested in the alternation between two grammatical variants, we employed mixed-effect logistic regression,[9] which models the relationship between the binary dependent variable asyndetic (que vs. Ø) and multiple explanatory variables (or predictors). In particular, these models predict the probability for an asyndetic complement (Ø) to be chosen instead of a syndetic complement (que), depending on the value of the predictor variables, addressee status, person and main verb (see Sections 4.3–4.5). Additionally, mixed-effect models allow fitting random effects, which are used to model varying intercepts for a variable, while evaluating the fixed effects of the predictor variables. The random effect in our models is textual typology, [10] and inclusion of this random effect thus enabled us to control for variation due to this parameter.

We fitted two mix-effect logistic regression models, a panchronic and a diachronic one. As described in the next two subsections, the panchronic model considers all data together, without taking into account real-time, but calculating the mutual interactions among predictor variables; the diachronic model calculates the interaction of each of the predictors with time.

4.2.1 Panchronic model

In order to select the most parsimonious panchronic model, we first fitted all variables (addressee status, person and main verb) as well as their interactions, and we ran an automatic backward selection with function pdredge from the R package MuMIn (Barton 2019). This technique did not exclude any of the fixed effects or interactions, indicating that they were all relevant. Therefore, the ideal model selected by the backward selection, as in (7), includes also a triple interaction between the three explanatory variables.

| (a-)syndetic ∼ person + addressee status + main verb + (1 | textual typology) + person*addressee status + person*verb + addressee status*verb + person*addressee status*verb |

Unfortunately, the presence of this interaction on the dataset produces very high standard errors, indicating overfitting due to data sparseness (i.e., the model is too complex for the amount of observations). Consequently, the triple interaction had to be excluded, and the final model used for the analysis is the one represented in (8).

| (a-)syndetic ∼ person + addressee status + main verb + (1 | textual typology) + person*addressee status + person*verb + addressee status*verb |

4.2.2 Diachronic model

As mentioned in Section 2.1, the linguistic predictors showed diachronic variation, therefore we also expect diachronic changes in how stylistic predictors influences the selection of complementation patterns. The diachronic regression model was fitted by including three predictors (addressee status, verb and person) and their interaction with time, a continuous variable expressed in years (ranging from 1400 to 1799). These interactions reveal whether the direction and size of the effect of the predictors changed over time. Pretesting revealed that time was best modelled as a four-degree polynomial (i.e., a curve with three break points),[11] reflecting the historical changes in the usage frequency of asyndetic and syndetic complementation (see Mazzola et al. 2022: 16–19).

We performed a backward selection (see 4.2.1) in order to find the most parsimonious model with the best fit to the data. This selection process led to the exclusion of the interaction effect between time and person, which was not found to significantly increase model fit. This indicates that the effect of person remains the same for the whole period studied, whereas the effects of addressee status and verb exhibit diachronic changes (as discussed in Section 5.1 and 5.2). The final model included all predictors except person, as well the interaction effects between time, addressee status and verb (see 9).

| (a-)syndetic ∼ person + addressee status + main verb + poly(time, 4) +(1 | textual typology) + poly(time, 4)*addressee status + poly(time, 4)*verb |

4.3 Addressee status

The audience of each of the texts contained in our dataset was annotated by applying the concept of power semantics, introduced in the seminal work by Brown and Gilman (1960). Power semantics is based on the idea that in static societies, in which social power is distributed by birth right, one person can be said to have power over another, in as much as s/he can control the behavior of the other.

The textual sources we use in our study are particularly suitable to be studied from the point of view of social power, because we often can infer the mutual relationship between the issuer and the addressee, thanks to the use of names and titles, and the information provided by the regesto (a short summary of the document) integrated in the metadata of the corpus CODEA+2015 (GITHE 2015).[12] Alongside the information of the regesto, the content of the document itself was perused for indicators of the social hierarchy between writer and addressee (profession, role in the communicative exchange, direct mentions to the mutual relationship, etc.).

If these criteria of inspection did not lead to a definitive decision, information provided by the types of forms of address used in the text was considered as a last resource. In this case, the forms of address and the titles (e.g., tú ‘you’, vos ‘you’, Vuestra Merced ‘Your Grace’, Vuestra Señoría ‘Your Lordship’, Vuestra excelencia ‘Your Excelence’, Ilustríssimo Señor ‘Illustrious Lord’, etc.) could give us a hint about the relation of the issuer with the addressee. However, we are aware that forms of address should be used with great caution, because their paradigm in Golden Age Spanish was unstable: as shown by Moreno (2002), the address system of Spanish was changing in the period under study. Moreover, the lack of evidence for reciprocal and non-reciprocal usages makes it hard to use address terms and pronouns as a reliable criterion to ascertain social power relationships.

Ultimately, the documents in the sample where coded according to the addressee status in comparison to the issuer of the document, by indicating whether or not the addressee had the power to control his/her behavior. The coding resulted in the following categories:

Superior: the addressee has a higher social power than the issuer (citizen to an institution, nun to aristocrat, children to parents, subjects to monarch, etc.)

Equal: addressee and issuer have the same status (siblings, cousins, nun to nun, friends, mayor to another mayor, etc.)

Inferior: the addressee has a lower social power than the issuer (king to citizens, bishop to monks, judge to defendant, husband to wife, parents to children, etc.)

No addressee: in some documents, especially certificates, charters and reports, we found no explicit reference to an addressee. Of course, also these documents imply an intended audience, the “referees” according to Bell’s (2001) terminology, which still influence the style even though they are not directly addressed.

According to the current literature (as discussed in Sections 2.1 and 3.2), we could expect the asyndetic variant to be predicted by superior addressees, following the results of Octavio de Toledo y Huerta (2011).[13] On the other hand, in line with Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles (2016), we might find that asyndetic complements are preferred when writer and addressee are equal.

4.4 Person

As anticipated in Section 3.3, the annotation at the textual level proposed for the addressee status can only be used to investigate global textual effects related to the type of audience. But analyzing audience design only at the textual level might produce misleading results, which is why we propose to focus on the interaction between the person of the main verb and addressee status.

In fact, within a document, a speech act can be directly addressed to the audience of the document, as in (10). However, it can also refer to reported speech, as in (11), where the indirect object and the addressee of the document do not coincide.

| […] pid-o V1 | e | suplic-o V1 | a | vuestr-a | magestad |

| ask-prs.1sg | and | beg-prs.1sg | to | poss.2pl-f | majesty |

| Ø | mand-e V2 | revoc-ar | e | revoq-ue | la | |

| order-sbjv.prs.3sg | revoke-inf | and | revoke-sbjv.prs.3sg | det.f.sg | ||

| dich-a | ordenança | |||||

| say.pst.ptcp-f.sg | regulation | |||||

| ‘I ask and beg Your Majesty to order to lift the mentioned order.’ (CODEA-1162, Toledo, 1526) | ||||||

| En | ella | me | mand-a V1 | vuestr-a | alteza | |

| In | pro.3sg.f | dat.1sg | order.prs-3sg | poss-f.sg | Highness |

| Ø | buelb-a V2 | a | inform-ar | por | doña | Ana María d’Espejo. |

| return-sbjv.prs.1sg | to | inform-inf | about | Ms. | Ana María d’Espejo | |

| ‘In that (letter) Your Highness orders me to inform you again about Ms. Ana María d’Espejo.’ (CODEA-1258, Salamanca, 1655) | ||||||

Example (10) belongs to a document in which the governor of a town asks the king to cancel an order that prevented grazing in certain territories. This document was coded as being addressed to a superior. In this case, the actual addressee of the sentence and the addressee of the document coincide. In contrast, example (11) was found in a document from a Mother Superior to the Royal Council, therefore also coded as being addressed to a superior. Yet, this sentence is a report of an order that she received from the addressee. Hence, on the sentential level, the Mother Superior is the addressee of the order in the sentence, and therefore ‘inferior’, but, on a textual level, this occurrence would be marked as ‘superior’, as the document in general is a communication addressed to the Royal Council.

Examples (10) and (11) demonstrate the need to distinguish between the textual and the sentential dimension (i.e., between macro and micro DTs). In order to capture this distinction, we created the variable Person by annotating the morphological person of the main verb.[14]

First, in terms of general effects, according to what was previously observed in the literature, absence of a complementizer should be correlated with first-person morphology. In English, this correlation has been observed multiple times: for instance, according to Torres Cacoullos and Walker (2009), the combination of first-person singular morphology with a verb of cognition produces a near-categorical absence of that, to the point that these combinations can be considered as discourse formulas (cf. also Tagliamonte and Smith 2005). As for Spanish, the claim for a more frequent association of asyndetic complements with first-person morphology is also found in Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles’s (2018) study on asyndetic complements with the verb creer ‘to believe’.

More importantly, we are interested in distinguishing between main verbs with first person and verbs with second/third person morphology, in order to set apart sentences, in which the author of the text is the performer of the speech act (first-person morphology), from all the other sentences (second/third-person morphology) which lack this author-relevant performative dimension.[15]

Given that our hypothesis is that asyndeton should be favored by superior addresses (as mentioned in Section 3.2), we are interested in whether such a stylistic constraint would be active at the textual or at the sentential level. If asyndetic complements are favored by the textual dimension (macro DTs), they are expected to be used in any type of complex sentence within documents addressed to superior addressees, i.e., as a generic marker of style. If they are favored by the sentential dimension (micro DTs), asyndeton should be more likely when the issuer is directly addressing someone superior, i.e., when the main verb has a first-person morphology. In the latter case then, the effect is due to the pragmatic nature of the speech act, rather than to the general stylistic features of the document as a whole.

4.5 Main verb

This variable is a bridge between the language-internal and the language-external dimension, which is useful to follow-up on the results of the previous study (Mazzola et al. 2022), by making a pragmatic distinction within the category of manipulation verbs (order vs. request). The analysis of the interactions of the main verb types with the other variables (addressee status and person), further allows for a more in-depth understanding of the selection of the syntactic variant depending on the type of speech-act.

Table 2 describes the sample of main verbs included in this study. We categorized these main verbs into five semantic classes: communication verbs, orders, requests, volition and cognition/perception. The distinction between pure verbs of request and verbs of order was motivated by the fact that order verbs entail a high degree of imposition on the hearer, whereas the imposition of verbs of request is milder, or at least mitigated (cf. Iglesias Recuero 2016). Therefore, we expect this fundamental pragmatic meaning to affect the selection of a stylistically marked syntactic variant.

Verbs and semantic classes.

| Semantic class | Verb | Translation | Tot. occurrences | N. of ø |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | 871 | 108 | ||

| Decir | To say | 871 | 108 | |

| Order | 1,297 | 239 | ||

| Decir | To tell | 100 | 30 | |

| Ordenar | To order | 76 | 13 | |

| Mandar | To order | 1,121 | 193 | |

| Request | 927 | 565 | ||

| Pedir | To ask | 362 | 199 | |

| Rogar | To pray | 165 | 67 | |

| Suplicar | To beg | 400 | 296 | |

| Volition | 281 | 39 | ||

| Querer | To want | 281 | 39 | |

| Cognition/perception | 330 | 83 | ||

| Creer | To believe | 72 | 21 | |

| Entender | To understand | 58 | 2 | |

| Saber | To know | 140 | 16 | |

| Ver | To see | 60 | 7 | |

Note that the verb decir can have two meanings: we distinguished its communicative uses (‘to say’) from its uses with the subjunctive in the subclause, as in the latter case it conveys a command reading (‘to tell someone to do something’), as illustrated in example (12) in which both instances of the verb decir express commands.

| Dic-e | Juliana que | le | dig-as | a Fermina | que | |

| say.prs-3sg | Juliana comp | dat.3sg | say- sbjv .prs.2sg | to Fermina | comp |

| procur-e | trat-ar | a | la | vieja | y | a |

| try- sbjv .prs.3sg | treat-inf | acc | det.f.sg | old.lady | and | acc |

| la | chica | como | antes. | |||

| det.f.sg | girl | as | before. | |||

| ‘Juliana says that you should tell Fermina to make sure that she treats the old lady and the girls as she used to.’ (CODEA-2419, Vizcaya, 1795) | ||||||

5 Results

The panchronic logistic regression model, described in Section 4.2.1, proved to be robust by predicting correctly 80.8% of asyndetic complements, with an index of concordance C = 0.83, which indicates an excellent discrimination (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000: 162). The diachronic logistic regression model (see Section 4.2.2) is even more robust than the panchronic one: it correctly predicts 84.2% of asyndetic complements, with an index of concordance C = 0.88. For both models, the computation of VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) did not indicate any sign of multicollinearity (Levshina 2015: 159).[16]

Tables 3 and 4 summarize the results of the panchronic and diachronic model respectively, including the coefficients expressed in Odd Ratios (OR) or Log-Odds,[17] the Standard Errors (SE), the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and the Significance of the effect.

Results of the Panchonic Model: (a-)syndetic ∼ person + addressee status + main verb + (1 | textual typology) + person*addressee status + person*verb + addressee status*verb.

| MODEL INFO: | Link function: logit |

| Observations: 3,706 | MODEL FIT: |

| Dependent variable: syndetic (rl) versus asyndetic | AIC = 3,220.67, BIC = 3,400.99 |

| Type: mixed effects generalized linear regression | Pseudo-R 2 (fixed effects) = 0.28 |

| Error distribution: binomial | Pseudo-R 2 (total) = 0.37 |

| Variable | Level | OR | SE | 95% CI | Significancea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept)b | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.02, 0.25 | *** | |

| Addressee Status | Inferior | rl c | |||

| Superior | 2.54 | 0.62 | 0.75, 8.63 | ||

| No addressee | 5.61 | 0.64 | 1.60, 19.7 | ** | |

| Equal | 1.82 | 0.71 | 0.46, 7.25 | ||

| Person | First person | rl | |||

| Second/third person | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.35, 2.15 | ||

| Main Verb | Cognition/perception | rl | |||

| Communication | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.03, 0.78 | * | |

| Order | 1.18 | 0.61 | 0.36, 3.90 | ||

| Request | 11.0 | 0.61 | 3.35, 36.0 | *** | |

| Volition | 1.27 | 0.77 | 0.28, 5.74 | ||

| Person * Addressee Status | Second/third person*superior | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.18, 0.65 | ** |

| Second/third person*no addressee | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.22, 0.75 | ** | |

| Second/third person*equal | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.28, 1.14 | ||

| Person*Main Verb | Second/third person*communication | 12.3 | 0.57 | 4.05, 37.5 | *** |

| Second/third person*order | 3.74 | 0.46 | 1.52, 9.24 | ** | |

| Second/third person*request | 2.16 | 0.44 | 0.92, 5.10 | . | |

| Second/third person*volition | 5.61 | 0.59 | 1.76, 17.9 | ** | |

| Status*Main Verb | Superior*communication | 1.92 | 0.81 | 0.39, 9.46 | |

| No addressee*communication | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.08, 1.82 | ||

| Equal*communication | 1.34 | 0.91 | 0.22, 8.03 | ||

| Superior*order | 1.70 | 0.68 | 0.45, 6.37 | ||

| No addressee*order | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.21, 2.67 | ||

| Equal*order | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.20, 3.65 | ||

| Superior*request | 1.22 | 0.64 | 0.35, 4.27 | ||

| No addressee*request | 0.26 | 0.64 | 0.08, 0.93 | * | |

| Equal*request | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.15, 2.77 | ||

| Superior*volition | 0.26 | 0.86 | 0.05, 1.41 | ||

| No addressee*volition | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.03, 0.88 | * | |

| Equal*volition | 1.03 | 0.88 | 0.18, 5.74 | ||

| Random effect | |||||

| Textual Typology | N | 7 | |||

| ICC | 0.13 | ||||

| Standard deviation | 0.70 |

-

aSignificance codes represents the p-value (with the customary significance threshold of p < 0.05.): ‘***’ p = 0.001; ‘**’ p = 0.01; ‘*’ p = 0.05; ‘.’p = 0.1; ‘ ’ p = 1. bThe estimated outcome of the dependent variable when all predictors are at their Reference Level (see Footnote 22). cReference Level: the regression model evaluates the effect of each level on the dependent variable compared to the reference level.

Results of the Diachronic Model: (a-)syndetic ∼ person + addressee status + main verb + poly(time, 4) + (1 | textual typology) + poly(time, 4)*addressee status + poly(time, 4)*verb.

| MODEL INFO: | Link function: logit |

| Observations: 3,706 | MODEL FIT: |

| Dependent variable: syndetic (rl) versus asyndetic | AIC = 2,839.83, BIC = 3,094.75 |

| Type: mixed effects generalized linear regression | Pseudo-R 2 (fixed effects) = 0.55 |

| Error distribution: binomial | Pseudo-R 2 (total) = 0.55 |

| Variable | Level | Log-odds | SE | CI | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −2.74 | 0.34 | −3.41, −2.07 | *** | |

| Time | Poly(year, 4)1 | 38.88 | 26.06 | −12.21, 89.97 | |

| Poly(year, 4)2 | −16.84 | 27.75 | −71.24, 37.57 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3 | −11.76 | 21.74 | −54.39, 30.87 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4 | −44.88 | 17.28 | −78.75, −11.01 | ** | |

| Addressee Status | Inferior | rl | |||

| Superior | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.3, 1.35 | ** | |

| No addressee | −0.22 | 0.35 | −0.92, 0.47 | ||

| Equal | 0.21 | 0.28 | −0.35, 0.77 | ||

| Main Verb | Cognition/perception | rl | |||

| Communication | −0.14 | 0.33 | −0.8, 0.52 | ||

| Order | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.07, 1.23 | * | |

| Request | 2.42 | 0.30 | 1.82, 3.01 | *** | |

| Volition | 0.38 | 0.36 | −0.33, 1.1 | ||

| Time*Addressee Status | Poly(year, 4)1:superior | 12.62 | 21.78 | −30.07, 55.3 | |

| Poly(year, 4)2:superior | 16.61 | 21.41 | −25.36, 58.57 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:superior | −8.19 | 15.93 | −39.43, 23.04 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:superior | 25.15 | 13.38 | −1.08, 51.38 | . | |

| Poly(year, 4)1:no addressee | 50.87 | 29.39 | −6.74, 108.48 | . | |

| Poly(year, 4)2:no addressee | −27.76 | 30.86 | −88.25, 32.73 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:no addressee | −0.78 | 21.22 | −42.38, 40.82 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:no addressee | 24.47 | 15.34 | −5.6, 54.54 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)1:equal | 43.89 | 21.89 | 0.98, 86.8 | * | |

| Poly(year, 4)2:equal | 6.8 | 21.73 | −35.79, 49.39 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:equal | 9.42 | 16.65 | −23.22, 42.06 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:equal | 13.76 | 14.75 | −15.16, 42.68 | ||

| Time*Main Verb | Poly(year, 4)1:communication | −18.51 | 24.24 | −66.02, 29 | |

| Poly(year, 4)2:communication | 24.39 | 27.04 | −28.62, 77.39 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:communication | −5.09 | 22.19 | −48.59, 38.41 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:communication | 22.17 | 16.31 | −9.81, 54.15 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)1:order | 22.32 | 21.99 | −20.78, 65.42 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)2:order | −6.85 | 24.70 | −55.28, 41.57 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:order | −20.02 | 20.21 | −59.65, 19.61 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:order | 43.22 | 15.19 | 13.43, 73.01 | ** | |

| Poly(year, 4)1:request | 36.13 | 23.46 | −9.87, 82.12 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)2:request | −64.7 | 26.22 | −116.11, −13.29 | * | |

| Poly(year, 4)3:request | 29.12 | 21.05 | −12.15, 70.38 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:request | 24.56 | 15.53 | −5.9, 55.02 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)1:volition | −24.47 | 27.42 | −78.21, 29.27 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)2:volition | −47.6 | 30.45 | −107.2, 12.1 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)3:volition | 28.96 | 24.54 | −19.15, 77.07 | ||

| Poly(year, 4)4:volition | −16.51 | 21.88 | −59.41, 26.39 | ||

| Random effect | |||||

| Textual typology | N | 7 | |||

| ICC | 0.01 | ||||

| Standard deviation | 0.21 |

A detailed interpretation of the results is presented in the following paragraphs by means of plots that help visualize the strength and the directions of the effects considered, by plotting the predicted probabilities of asyndetic complements versus syndetic complements.

5.1 The social power of the addressee

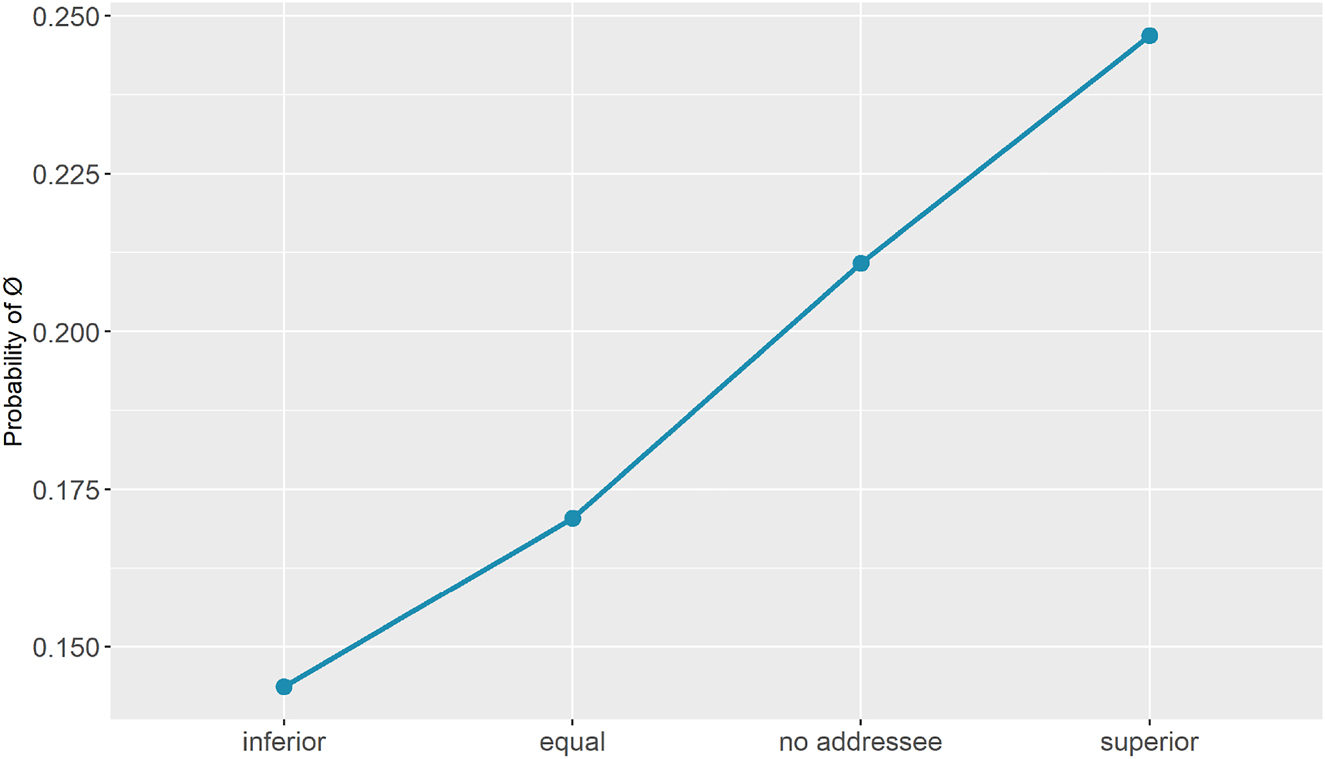

The results concerning the variable addressee status ( Figure 3 ) illustrate that the likelihood of use of an asyndetic clause is higher in documents addressed to a superior addressee, i.e., someone with more social power than the issuer of the document. To a smaller extent, documents with no explicit addressee and documents addressed to equals also favor absence of the complementizer. In contrast, asyndetic complementation is least likely to be used in documents addressed to recipients with less social power than the writer (inferior).

Main effect of addressee status – Panchronic Model.

This result points to the relevance of the social power distinction established in Section 4.3. The effect of Addressee Status follows a cline of ascending/descending social power: the probability of asyndetic complementation increases as the social power of the addressee increases.

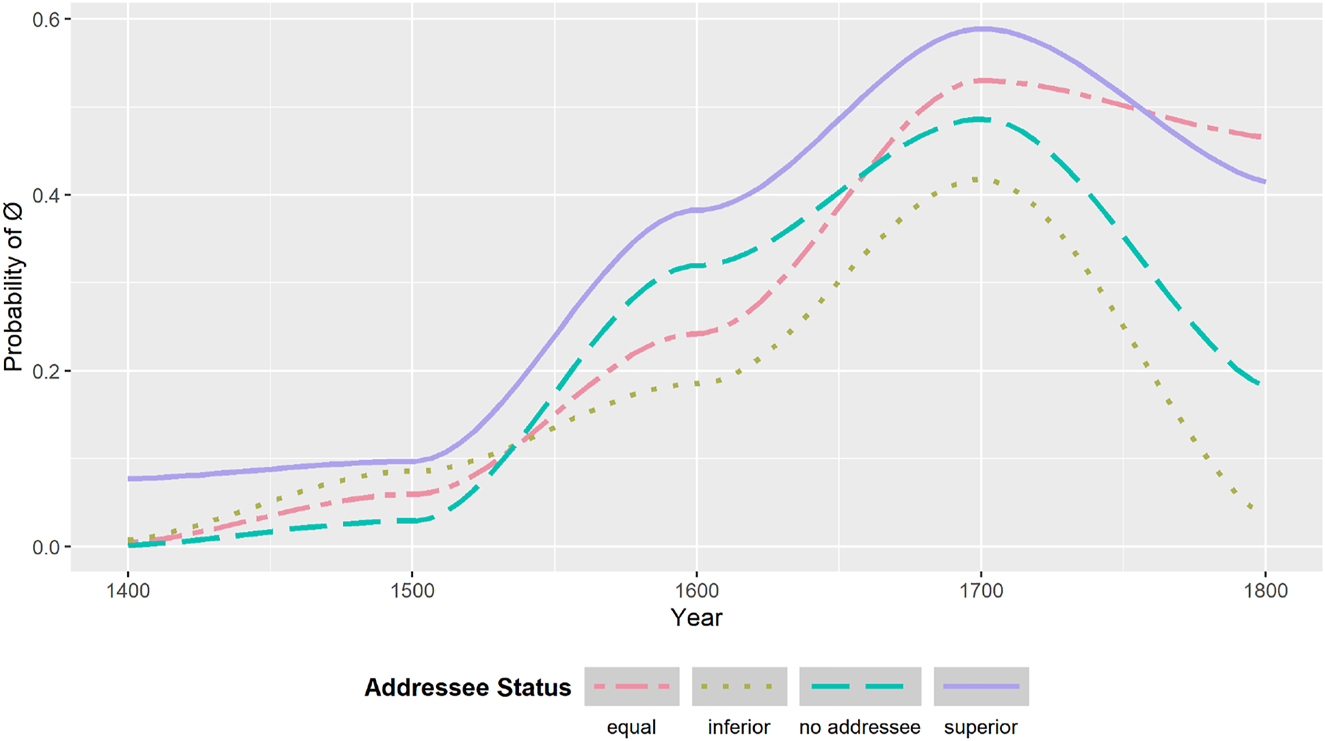

Figure 4 visualizes the effect of the variable addressee status from a diachronic perspective. First of all, we can observe a general sharp increase of the likelihood of use of the asyndetic variant between the 16th and 17th century, followed by a mild decrease in the course of the 18th century. In the first stage, between 1400 and 1500, the likelihood of asyndetic complements is very low, and seems to be only weakly affected by the social power cline (even though asyndetic complements are mostly associated with superior addressees already in this initial phase). The probabilistic effect of social status increases after the second half of the 16th century, where the different lines referring the addressee status diverge. In this time period, the relative impact of the different categories of social status on selection of complementation patterns follow the trend found in the panchronic model (see Figure 3). However, this picture changes after the beginning of the 17th century. In particular, we document a marked increase of the likelihood of use of asyndetic complements with addressees that have the same social status as the writer. According to our model, likelihood of use of asyndetic complementation is highest in these usage contexts after 1750, even surpassing texts directed to an addressee of superior social status. This is due to the fact that texts addressed to equals partake to much lesser degree in the general decrease in the likelihood of asyndetic complementation after 1750.

Interaction between time and addressee status – Diachronic Model.

5.2 The main verb semantics

Figure 5 illustrates the interaction effect between main verb and addressee status. Focusing on the main verb first, we observe that selection of asyndetic complements is particularly likely with verbs of request (pedir ‘to ask’, rogar and suplicar ‘to beg’), in line with the results of Mazzola et al.’s (2022) analysis. However, in contrast with the previous study, we can observe a large difference between verbs of request and order, which have a very similar syntactic configuration, both being manipulation verbs (Givón 2001: 41). Thus, asyndetic complementation is more likely with verbs of request than with verbs of order.

Interaction between Main Verb and Addressee Status – Panchronic Model.

Moving to the interaction between main verb and addressee status, Figure 5 illustrates that the use of asyndetic complements is strongly associated with verbs of request within documents addressed to a superior person/institution. Orders show a similar effect, but the chances of an asyndetic complement after a verb of order are also quite high in documents without an identified addressee. Chances of asyndetic complements are a bit higher with verbs of volition when the document is addressed to an equal, with cognition/perception verbs when the documents has no identified addressee, while for communication verbs the chances of asyndeton are low regardless of the type of addressee.

With respect to the diachronic changes of the main verb effect, Figure 6 shows that asyndetic complements are mainly predicted by verbs of request already in the second half of the 15th century, and that the size of this effect increases dramatically over time. In texts dated around 1700, our model predicts a usage frequency of 80% for asyndetic complements in such contexts. Until about 1550, next to request, the only other verb class found substantially with asyndetic complements is volition verbs. However, after 1500, we document a strong increase in the likelihood of use of asyndetic complements with verbs of order grows, followed by cognition, perception and communication verbs in the 17th century. After the beginning of the 18th century, we find a general decrease in the likelihood of use of asyndetic complements with all verb classes. Interestingly, communication verbs seem to be less affected by this trend than the other verb classes.

Interaction between time and main verb – Diachronic Model.

5.3 The role of morphological person

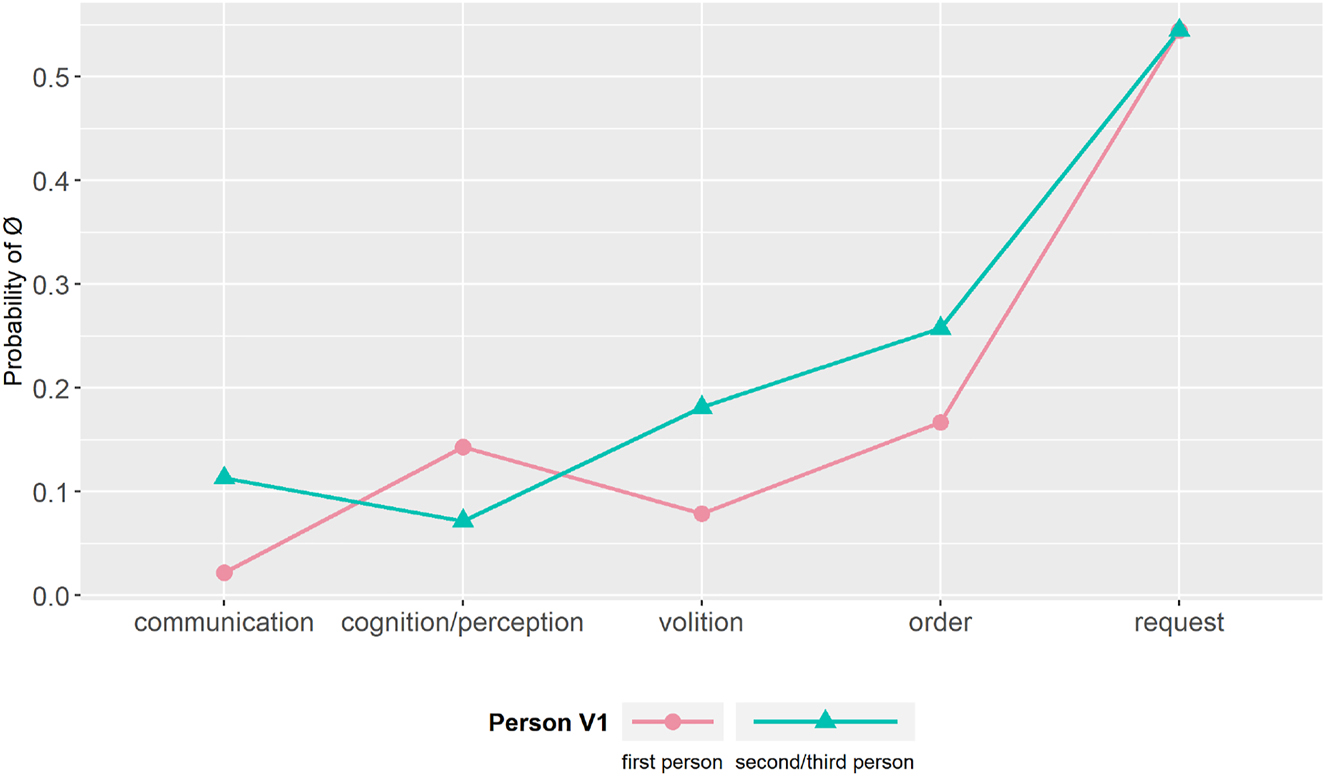

Concerning the variable person and in contrast with our expectations, Figure 7 reports that the predicted probabilities of asyndetic complements are much higher with second- or third-person morphology than with first-person morphology in the main verb. This aspect will be further discussed in Section 6.

Interaction between person and addressee status – Panchronic Model.

Crucially for our purpose, Figure 7 demonstrates that the effect of social power is particularly strong when the main verb is inflected for first person. In spite of the fact that even with second- and third-person main verbs, asyndetic complements are more probable with superior addressees, the difference between inferior, equal and superior is much more evident in cases in which the main verb is inflected in first person.[18]

As explained in Section 4.4, we use the interaction of the addressee status and the variable of person of the main verb in order to set apart textual from sentential effects (macro and micro DTs). The results indicate that the social-power cline observed in Figure 3 is more relevant when the main verb is inflected for first person, i.e., when the issuer is directly involved in the speech act and feels the need to conform to social power conditionings. Consequently, we can conclude that social power effects are mainly relevant at the sentential level.[19]

Finally, the interaction between person and main verb visualized in Figure 8 suggests that verbs of request are the best predictors of asyndetic complements regardless of their morphology. Most other verb types display a tendency for asyndetic complements to occur with second/third-person morphology, with the notable exception of cognition/perception verbs, which show a slight preference of asyndetic complementation when the verb is inflected in first-person morphology. The latter point suggests that the findings of Blas Arroyo and Porcar Miralles (2018) concerning the main verb morphology are clearly linked to the semantics of verb analyzed in that study (creer ‘to believe’), and to the discourse traditions and environments of private letters, which favor the expression of personal views and opinions.

Interactions between person and main verb – Panchronic Model.

6 Syntactic alternations and the benefits of a multidimensional approach

The results presented above evince the existence of complex interactions between variables of a different nature, and confirm that semantic, pragmatic, social and stylistic variables are tightly intertwined in the process of selection of syndetic and asyndetic complementation patterns, and are affected by diachronic fluctuations. Consequently, we argue that the insufficient and inconsistent stylistic characterization of the asyndetic construction in the existing literature is due to the lack of a broad and multidimensional view of the alternation in these studies.

First, our analysis demonstrates the relevance of social power for the alternation between syndetic and asyndetic complements. The use of an Audience design approach shows that asyndetic complements were a marked stylistic option, employed especially when addressing superiors. This finding further confirms Octavio de Toledo y Huerta’s (2011) claim about the style-shifting of Santa Teresa in the two versions of her Camino de Perfección: asyndetic complements were markers of an elegant style, suitable to address a prestigious audience.

In the same fashion, the high likelihood of asyndetic complements in documents with no explicit addressee (see Figure 3) is motivated by the same stylistic effects as the ones observed for superior addressees. Arguably, the choice for a marker of an elegant and sophisticated style, such as the asyndetic variant, could be motivated by “referee design” (Bell 2001). As defined in Bell (2001: 147) “[r]eferees are third persons not usually present at an interaction but possessing such salience for a speaker that they influence style even in their absence”. Since most of the documents with no addressee are administrative documents (such as deeds, certificates and wills), writers acknowledge the possibility that they might be received by unknown superiors or at least by public authorities, adjusting their style accordingly. The effects of the social power highlighted here empirically demonstrate the relevance of the Audience Design framework, which causes style-shifting in reaction to an audience.

Second, our analysis highlights the prominence of some pragmatic implications related to the verbs. In the previous study (Mazzola et al. 2022), we showed that asyndetic complements are favored by the syntactic schemas of non-implicative manipulation verbs (order and request verbs, cf. Givón 2001). While in the present paper this result is reproduced, our findings demonstrate that asyndetic complements are mainly predicted by verbs of request, much more than by verbs of order (Figure 5). In spite of their semantic and syntactic similarity, the two types of verbs differ on the pragmatic level. As shown by Iglesias Recuero (2016: 979), verbs like rogar and suplicar (‘to beg/pray’) entail the submission to the willingness of the recipient to realize the content of the petition. These two verbs also have a deferential feature, as they put the speaker in a position of inferiority compared to the addressee (Iglesias Recuero 2016: 979).[20] This pragmatic implication is reversed in verbs of order: an order implies a strong imposition of the speaker on the recipient. It is this crucial pragmatic distinction that explains the difference of effects size in the predicted probabilities of the two classes of verbs. The diachronic model also showed that over time asyndetic complements become increasingly more entrenched with the deferential verbs of request. This means, that in turn, the whole construction (a verb of request followed by an asyndetic complement) becomes a marker of deferential style. In this sense, the use of this “deferential construction” is an indication of a proactive style-shift, driven by Speaker Design, i.e., by the need of the speaker/writer to project a specific social image, as a humble individual that performs a polite request with the due respect for the addressee.

Third, this paper demonstrates the importance of implementing the distinction between micro and macro Discourse Traditions when investigating stylistic variation. In fact, by modelling the interaction between the morphological person of the main verb and the addressee status, we were able to identify textual and sentential effects, showing that the alternation at stake is influenced by socio-stylistic effects which are active at level of micro Discourse Traditions (see Section 3.3). More specifically, we observed that the effect of social power is especially strong when the issuer is personally performing a directive speech act (signaled by the first-person morphology). In this case, style-shifting is achieved through the selection of an asyndetic complement which indicates that the writer is evoking a micro Discourse Tradition. In particular, the writer wishes to evoke a Discourse Tradition which, as we have seen above, is suitable, on the one hand, to address a prestigious audience and, on the other hand, to build his/her own social identity as an inferior politely asking something to a superior. In our view, this finding highlights the need for an approach to socio-stylistic variation that integrates a reactive as well as a proactive view of the speaker’s motivations for style-shifting (thus, a unified view of Audience and Speaker Design). In fact, if a writer wants to perform a request in order to obtain something from a superior addressee, she or he will try to choose a suitable linguistic style that acknowledges the deference that the addressee deserves, and that highlights her or his social inferiority.

Fourth, as shown by the diachronic changes of the addressee status effect (Figure 4), towards the end of the 18th century, the effect of the social power cline seems to wane. The effect of documents with no addressee becomes much weaker, while the effect of documents addressed to equals rises and becomes even stronger than the one of documents addressed to superiors. This might indicate a diachronic decline of the effect of the social power on complementation patterns, and consequently a weakening of reactive style-shifting (see Section 3.2): in the 18th century, the probabilities of an asyndetic complement are almost the same, regardless of whether the addressee is superior or equal, therefore the selection of complementation patterns is no longer driven by the social power of the addressee. Rather, as shown by the diachronic results of the main verb variable, the alternation becomes increasingly more governed by proactive style-shifting, i.e., the intention of performing a request by means of a style that projects deference and represents the speaker/writer as an inferior.

Finally, with respect to the variable person, the model shows that asyndetic complements are highly probable when the main verb is inflected in second/third person (Figures 7 and 8). This contrasts with our expectation to find more asyndetic clauses with first-person main verb, formulated on the basis of the existing literature on Spanish and English (Section 4.4). This surprising effect might be due to the correlation between asyndetic complements and se-constructions might explain this unexpected result. According to Mazzola et al. (2022) results a context like the one seen in example (3), with the se-impersonal construction in the main verb, not only greatly improves the chances of an asyndetic complement, but its effect becomes even stronger over time. Most likely many of those third-person main verbs are actually due to the abundance of impersonal constructions (morphologically coded with third-person verbs), which in turn is associated with a high rate of asyndetic complements.

7 Conclusions

This paper has shown how the motivations for the syndetic/asyndetic alternation can be explained by adopting a multidimensional approach, which is intended as a broader view of the possible factors influencing the choice-making of the speakers. We reconsidered previous accounts of the topic both from a theoretical and from a methodological standpoint. We attributed the lack of a clear stylistic characterization of these complements in previous studies to their reliance on traditional textual typologies and descriptive analyses. Macro categorization of texts according to genre or register overlook some more fine-grained stylistic effects that are diluted in these variables. In this study, we have demonstrated that the writer’s choice of alternative grammatical constructions is not strictly motivated by the representation of the language of a textual genre or register, but is more importantly triggered by social motivations affecting the writer’s face and their social identity and it is more accurately explained by the concept of (micro) Discourse Traditions.

Considering the premises of the Discourse Traditions and the Audience/Speaker Design frameworks, we analyzed syndetic and asyndetic clauses in a corpus of historical Spanish data (15th–18th century) by using mixed-effect logistic regression modelling. Our results show that the stylistic choice for an asyndetic complement in (pre-)classical Spanish is determined by discourse environments at the sentential level (micro Discourse Traditions, Rosemeyer in press), rather than at the textual level. In particular, usage of asyndetic complements is strongly favored by environments of deferential requests addressed to a person or institution with a higher social power, and more in general by environments in which the writer wants to presents itself as a humble inferior individual. Additionally, we showed the importance of a diachronic approach: similarly to what has been observed about linguistic predictors (cf. Mazzola et al. 2022), also the strength of social and stylistic predictors can exhibit fluctuations and changes in the course of time.

In addition, the analysis developed in this paper has demonstrated how effects at the syntactic level can be examined by adopting a socio-stylistic approach to variation. In particular, the finding that usage of asyndetic complements is favored by high semantic-syntactic integration of the complex clause (manipulation schemas) is a result of pragmatic implications involved in this syntactic alternation (use of asyndetic complements with deferential verbs of request), which are the products of a conventionalization of social effects. This latter finding is in line with an emergentist view of language (cf. Hopper 1988, 2015), which entails that grammatical patterns and constraints emerge in use and interaction and that they are indissolubly fused with social factors.

Funding source: KU Leuven Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: C14/18/034

-

Research funding: This work was supported by KU Leuven Research Council (C14/18/034).

Primary sources

Augustinus Hipponensis: Verbum Dei mandatum Patris 6: Aequalitas Filii cum Patre. https://www.augustinus.it/latino/discorsi/discorso_181_testo.htm (accessed 12 July 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Cicero, De Re Publica, Liber I, 14. https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cicero/repub1.shtml#14 (accessed 12 July 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

CHARTA. Corpus Hispánico y Americano en la Red: Textos Antiguos. www.corpuscharta.es (accessed 29 March 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

GITHE. 2015. Codea+ 2015. Corpus de documentos españoles anteriores a 1800. http://www.corpuscodea.es/ (accessed 10 January 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Patrimonio Actual – Press Note. https://patrimonioactual.com/page/el-manuscrito-autografo-camino-de-perfeccion-ya-puede-verse-en-la-exposicion-teresa-de-jesus-en-la-bne/ (accessed 12 July 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

References

Barraza Carbajal, Georgina. 2014. Oraciones subordinadas sustantivas de objeto directo. In Concepción Company Company (ed.), Sintaxis histórica de la lengua española (Lengua y estudios literarios), 2971–3106. Mexico City: Universidad nacional autónoma de México: Fondo de cultura económica.Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, Kamil. 2019. MuMIn: Multi-model inference. R package version 1.10.0.1. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/MuMIn.pdf (accessed 22 January 2020).Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Bolker Ben & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48.10.18637/jss.v067.i01Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, Allan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13(2). 145–204.10.1017/S004740450001037XSuche in Google Scholar

Bell, Allan. 2001. Back in style: Reworking audience design. In Penelope Eckert & John R. Rickford (eds.), Style and sociolinguistic variation, 139–169. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511613258.010Suche in Google Scholar

Benot, Eduardo. 1991. El arte de hablar: Gramática filosófica de la lengua castellana (reproducción facsímil). (Autores, Textos y Temas 4). Barcelona: Anthropos.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas & Susan Conrad. 2009. Register, genre, and style (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511814358Suche in Google Scholar

Blas Arroyo, José Luis & Margarita Porcar Miralles. 2016. Un marcador sociolingüístico en la sintaxis del Siglo de Oro: Patrones de variación y cambio lingüístico en completivas dependientes de predicados doxásticos. Revista internacional de lingüística iberoamericana 14(28). 157–185.10.31819/rili-2016-142809Suche in Google Scholar

Blas Arroyo, José Luis & Margarita Porcar Miralles. 2018. “Tiene tanto temor a la mar que creo no lo hará”: Variación en la sintaxis de las completivas en los Siglos de Oro. In María Luisa Arnal Purroy, Rosa María Castañer Martín, José María Enguita Utrilla, Vicente Lagüéns Gracia & María Antonia Martín Zorraquino (eds.), Actas del X Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Española: Zaragoza, 7–11 de septiembre de 2015, vol. 1, 531–548. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico.Suche in Google Scholar