Abstract

As emergency management evolved to encompass a focus on supporting safe growth and development for communities, the role and responsibilities of government became increasingly complex with aspects of emergency management becoming quintessential. Issues with communication uncovered the need to understand how managers collect, disseminate, and adapt critical information through understanding crisis type and local community needs. This paper examines the use of crisis communication strategies in emergency management practice and how these strategies have been impacted by Situational Crisis Communication Theory. This theory’s prescriptive approach connects leaders’ response to strategies emphasizing adaptation to local community needs and crisis type. Utilizing structural equation modeling and qualitative analysis, results from a nationwide survey of county, and county-equivalent, emergency managers in the United States is included. The survey focused on the relationship between crisis communication strategies, local community needs, crisis type, and perceived resilience. The paper concludes with a discussion of the significant indicators impacting use of crisis communication strategies by emergency managers along with critical importance of adaptation to local community needs and crisis type. In addition, the paper unveils practical recommendations for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers in the field of emergency management and its counterparts.

1 Introduction

Moving from a reactionary management style to unified command and control, the emergency manager has become an essential member of their community. Crises related to emergency management frequently uncovered issues related to its role and responsibilities, as well as interaction between local, state, and national actors. Communities rely on leaders to effectively communicate before, during, and after a crisis while coordinating resources to prevent or reduce negative impact (Birkland 2006; Liu, Iles, and Herovic 2020; Sylves 2014). The challenges faced by communities and invested stakeholders have spurred numerous studies focused on preparation, mitigation, response, and recovery activities. More specific studies focused on how diverse crises influence communication capacity, processes, and strategies. Essentially, results indicated effective communication hinges on the ability to learn and assess a community’s needs followed by adaptation and practically applying these lessons (Boin and McConnell 2007; Comfort 2007; Coombs 2014; Cutter et al. 2008; Cutter, Burton, and Emrich 2010; McEntire 2007; Sylves 2014; Waugh and Streib 2006).

In the arena of communication, a crisis incorporates perceiving an unpredictable event and how it can threaten stakeholder expectations, impact organizational performance and result in negative outcomes (Coombs 2014). Building upon Coombs’ definition, this researcher views crisis as not only having the potential for negative outcomes but learning opportunities that can lead to positive growth. These learning opportunities can revolve around the arena of communication and then intentionality behind this activity that incorporates intent, message creation, transmission and information processing. The term crisis also encompasses a diverse range of situations and viewing emergency management through the lens of a crisis approach incorporates the act of seeking to answer questions related to the immediate situation, understanding the unexpected event, and finding opportunities within the chaos (Boin and McConnell 2007; Liu, Iles, and Herovic 2020; Rosenthal, Boin, and Comfort 2001).

Focusing on emergency managers is pivotal to understanding crisis communication strategies as they are responsible for the majority of preparation, mitigation, response and recovery activities and are considered the experts of their communities (Cutter et al. 2008; McGuire and Silva 2010; Okechukwu Okoli, Weller, and Watt 2014; Ross 2016; Waugh and Streib 2006). Although some question their role in crisis communication and their decision-making authority in local-level communities, their expertise is critical to understanding the use of crisis communication strategies and the integration of knowledge of local community needs and adaption based on crisis types. Moreover, emergency managers are encouraged to operate in such a way that information collection, organization, and dissemination leads to open, honest, accurate, tailored, two-way, and knowledgeable information. Although they may not be the final decision-maker, they are expected to provide guidance and assist with instructing, sharing and adjusting (Coombs 2014; Coombs and Holladay 1996; Frandsen and Johansen 2016; Liu, Austin, and Jin 2011; Liu, Iles, and Herovic 2020; Seeger 2006).

This paper will discuss the evolution of crisis communication, integration into emergency management practice, and results from a survey of county-level emergency managers concerning their use of crisis communication strategies. In addition, this paper discusses significant results from a structural equation modeling analysis of survey results and the resulting practical recommendations for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers in the field of emergency management and its counterparts.

2 Evolution of Crisis Communication

The singular event sparking the beginning of crisis communication and management is the 1980s tampering incident of the Johnson and Johnson Tylenol product that poisoned seven individuals. Businesses began to realize how negative consequences of improper management have a resounding impact on their bottom line. Crisis Management became a field where individuals and organizations seek to mitigate or diminish negative impacts of a crisis and protect stakeholders (Coombs 2014; Frandsen and Johansen 2016). The crisis communication component consists of “the ongoing process of creating shared meaning among and between groups, communities, individuals and agencies, within the ecological context of a crisis, for the purpose of preparing for and reducing, limiting and responding to threats and harm” (Sellnow and Seeger 2013, 13). Although crisis management began in the early 1980s, research did not start surfacing until later in the decade and was characterized by a focus on organizational reputation and personal experiences of those who managed the incident.

With the Tylenol case being considered a catalyst, the permanence for the field was a result of the Challenger explosion in 1986. Researchers shifted their focus to decision-making and emphasizing rhetorical analysis focusing on what managers said and did to address crises and lack of acknowledgment for stakeholders (Coombs 2014). Within the 1990s, crisis communication exploded due to research driven by the field of public relations. Publications and case studies focused on corporate apologia, image restoration theory, and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) (Benoit 1995; Coombs 2014; Frandsen and Johansen 2016; Hearit 1994; Ice 1991). Interest in crisis communication and theoretical application expanded, but arenas of public relations and organizational management are the main strongholds for research with limited integration into emergency management. With the expansion of research, distinctions surfaced surrounding macro versus micro conceptualizations of crisis communication, the influence on practice, and generation of linear and cyclical phases of communication (Coombs and Holladay 2002; Ulmer, Seeger, and Sellnow 2017).

2.1 Connection of Crisis Communication to Emergency Management Practice

Communities rely on leaders to effectively communicate before, during, and after a crisis while coordinating resources to prevent or reduce negative impact (Birkland 2006; Sylves 2014). Effective communication hinges on the ability to learn and assess a community’s needs followed by adaptation and practically applying these lessons (Boin and McConnell 2007; Comfort 2007; Coombs 2014; Cutter et al. 2008; Cutter, Burton, and Emrich 2010; McEntire 2007; Sylves 2014; Waugh and Streib 2006). General emergency management communication strategies incorporate a timeline focus of before, during and after an identified disaster or hazard (Chandler 2010). The linear format, although widely used, is superficially detailed and leaves the majority of decision making to those initiating the communication (see Figure 1). Best practices generated by researchers and practitioners to aid in timely and comprehensible messages for impacted individuals revolve around message transference, dissemination time, included components, comprehension, and anticipated response (Drabek 1985; Liu, Iles, and Herovic 2020; Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger 2017; Walker 2012; Waugh and Streib 2006).

Visualization of emergency management information collection, organizing, and dissemination in linear timeline.

Communication studies discuss a critical aspect of effective communication being recognition of intended audience and potential communication barriers, recipient needs, and awareness of how plans and procedures require adaptation (Chandler 2010; Seeger 2006). Researchers and practitioners discuss how the end goal is community capacity building and enhanced resilience. This goal of capacity building and enhanced resilience is a promoted ideal in emergency management practice and integrated into guiding frameworks and documents; however, without an explicit design, communication processes became continuously constrained due to uncertainty of risk and translating the when, where, what, how, and why (Comfort and Haase 2006; Coombs 2014).

In order to stabilize the practice of emergency management communication, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) (2014) became responsible for creating and administering policies and protecting existing infrastructure. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 also established an Office of Emergency Communications responsible for establishing a national planning, implementation, and training of communications equipment for relevant state, tribal, and local governments and emergency response providers (Department of Homeland Security [DHS] 2014). Moreover, the whole community approach generated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) focused on strengthening the capacity of a community so the impacted individuals can prepare more effectively, better handle the impact of a crisis, recover quicker, and adapt to the point of enhancing their resilience (FEMA 2011). The National Emergency Communications Plan (NECP) assisted local, state, and tribal emergency management practitioners to strategically plan and promote formal decision-making structures, leader designations for coordinating communication, enhance collaboration, planning and operational protocols, technological integration, creation of shared vision, and advancing emergency communication within and between all levels (DHS 2014).

The ability of practitioners to understand all the needs of their community and generate a stable system for delivering critical information is time intensive and complex. Challenges arise surrounding sources of information, channels or communication tools utilized, and the content of messages released. Additional issues include:

Not anticipating community needs,

Lack of adaptation for crisis type,

Timeliness of information released,

Lack of initiative to communicate,

Inadequate or incompatible communication technology,

Variations in values and norms,

High levels of stress and pressure on individuals and teams,

Rapid event shifts and changing information,

Tension with media and the public,

Poor information-gathering capacities,

Inability to convey accurate information and its meaning, and

Cognition and collaboration (Benson 1988; Bharosa, Lee, and Janssen 2010; Chandler 2010; Coombs 2014; Perry and Nigg 1985; Walker 2012; Wexler and Smith 2015).

Although the intent of communication streams may be well-intentioned, the impact varies due to how messages are sent, received, applied, and reacted to (Benson 1988; Ozanne, Ballantine, and Mitchell 2020; Phillips and Morrow 2007).

Every communication situation during a crisis must be approached with consideration of many dynamics. Therefore, communicated messages are complex and ambiguous at the same time. Successful public communication seeks to balance the needs and expectations of all of these diverse audiences and speak to each of them while not miscommunicating to the remainder (Chandler 2010, 58).

To support communication efforts, emergency managers are encouraged to operate in such a way that information collection, organization, and dissemination leads to open, honest, accurate, tailored, two-way, and knowledgeable information. This can be accomplished through identified best practices of: promoting effective communication regarding process approaches and policy development; pre-event planning; partnerships with the public; listening to the public’s concerns and understanding the audience; collaboration and coordination with credible sources; meeting the needs of the media and remaining accessible; communicating with empathy and concern; accepting uncertainty and ambiguity; and promoting self-efficacy (Ozanne, Ballantine, and Mitchell 2020; Seeger 2006). Essentially, the more attention given to crisis communication strategies and adaptations for local community needs, then the better off a community will be.

3 Crisis Communication Strategies

Although research and practice developed general emergency management communication strategies, the relationship between communication and its impact is not a linear relationship. Practitioners must understand the complex phenomena of communication, identify and implement strategies incorporating information transmission, comprehension and impact, and then adapt based on community needs. Emergency management communication research also discussed the impact of communication, but more emphasis is placed on information collection, organization, and dissemination (Chandler 2010; Kapucu and Özerdem 2011; McEntire 2007; Sylves 2014; Waugh and Streib 2006). In terms of strategies for generating timely and comprehensible messages that meet the diverse needs of its audiences, general recommendations include: (1) how to transfer the message; (2) when to send the message; (3) will the recipient see, read, or hear the message; (4) is the message comprehensible; and (5) what will be the response (Seeger, Sellnow, and Ulmer 2003; Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger 2017; Walker 2012).

Within previous research, emergency managers and public administrators were deemed the wisest or most successful when they integrated awareness of cultural differences within their communities into practice (Drabek 2016; Ozanne, Ballantine, and Mitchell 2020). These administrators and managers provide an understanding and respect of their communities that assist in command efforts during crisis response.

“It is not just what you say and how you say it, although those aspects are important- but it is the attention, perception, needs, and cognitive abilities of people in the midst of a crisis and how they will understand and react to your messages that ultimately determine how effective will be your emergency communication” (Chandler 2010, 58).

The challenge then lies in identifying these populations and incorporating their unique needs in preparation, mitigation, response, and recovery activities as well as not viewing these groups as impaired or weak (Kailes and Enders 2007). Crisis communication strategies build upon these generalized strategies and provide more guidance related to adaptation for local community needs, event type, involved stakeholders, and favors a cyclical format where the communication process is constantly evolving based on adaptation, instruction, and sharing (Coombs 2014; Coombs and Holladay 1996; Liu, Austin, and Jin 2011; Seeger 2006). These strategies rely on making connections between demographics and abilities to cope with a crisis hinge on effective policies and implementation.

In terms of basic crisis communication strategies, a three-stage approach has been promoted occurring before, during, and after the crisis similar to general emergency management communication practice (see Figure 2). However, there is a distinction between the two as crisis communication focuses on more than just managing information by emphasizing the management of meaning (Coombs 2014). The precrisis stage is critical for responsible officials to focus on planning and preparation. Competent individuals are knowledgeable about policies and procedures and participate in training and exercises to proactively identify potential challenges. The crisis response stage focuses on implementation of policies and procedures and differentiating how officials will react and adapt communication strategies. The postcrisis stage concentrates on following up with stakeholders and returning to a sense of normalcy before preparing for the next event. Within each of these stages is an emphasis on what it means to the intended audience.

Visualization of crisis communication strategies in linear timeline.

For local community needs, if due attention is given to the why and how populations receive and interpret disaster information, then negative impacts can be effectively mitigated. For instance, individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing require closed captions (Phillips and Morrow 2007). The homeless population lacks stable connections to electronic resources affecting the ability to receive electronically disseminated crisis related information and effectively prepare and respond (Wexler and Smith 2015). Moreover, the needs of each audience affect whether the community will accept or reject crisis-related information (Coombs 2014). The emphasis on adaptation comes from the psychological nature of relating emergency management activities for crises to previously experienced events and anticipation for future action.

3.1 Integration of Situational Crisis Communication Theory

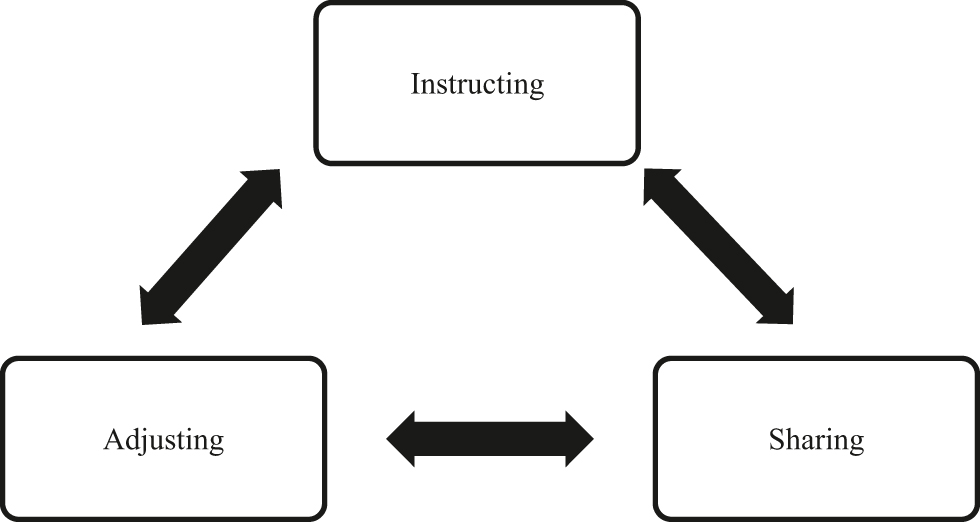

In terms of theoretical perspectives, crises can be viewed through the sociological disaster perspective, actions and decision-making within organization theory, political science perspective of structure and function, or business management focus of reputation and business continuity (Allison and Zelikow 1971; Almond, Flanagan, and Mundt 1973; Boin and McConnell 2007; Coombs 2014; Flin 1996; Gamage 2016; Hermann 1972; Klein 1999; Lebow 1984; Mitroff and Pauchant 1990; Ozanne, Ballantine, and Mitchell 2020; Rosenthal, Boin, and Comfort 2001; Seeger, Sellnow, and Ulmer 2003). Yet, the most applicable theory supporting crisis communication strategies is Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), which provides a prescriptive system to connect response strategies to the crisis situation with integrated adaptations for local community needs and crisis typology (Coombs and Holladay 2002; Gamage 2016). This is incorporated through instructing (informing stakeholders of response practices), adjusting (integrating information related to the who, what, when, where, why, and how), and sharing (disseminating at the onset of a crisis).

Linking outcomes related to all these diverse fields, Coombs (2014) developed SCCT to understand reputational threat brought on by crises and resulting response strategies. Crisis response strategies came as a result of Apologia, impression management, and Image Repair Theory. Coombs’ incorporation of attribution theory applies to crisis management situations by taking an audience-centered approach and considering stakeholder reaction (Coombs 2014). Attribution theory focuses on how an individual cognitively processes cause and effect within their environment and where responsibility is credited (Kelley 1967; Weiner 1985). SCCT expands the concept from individuals to a group and how they infer cause related to the actions of emergency management organizations (Sellnow and Seeger 2013; Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger 2017; Walker 2012).

It is important to note the major differentiation between strategies are the time-dependent, linear format of basic emergency management versus the cyclical, always evolving structure of crisis communication with integrated SCCT (see Figure 3 for visualization).

Visualization of crisis communication strategies connected to Situational Crisis Communication Theory.

At the heart of SCCT is an emphasis on recovering from the crisis. It attempts to balance proactive and reactive measures in a way to intentionally respond and recover. With one of the overarching goals being the maintenance of a positive reputation within crisis response, SCCT is predominantly utilized in public relations research and acknowledges how the public will assign responsibility to response organizations (Gamage 2016; Sellnow and Seeger 2013; Walker 2012). More specifically, SCCT is focused on the degree to which individuals or a stakeholder will hold an organization responsible for a crisis. A threat to effective communication consists of any negative reputation held by an administrator or organization. This theory proposed four groups of response strategies (see Table 1).

Situational Crisis Communication Theory response strategies (adapted from Coombs 2014).

| Strategies | Definition |

|---|---|

| Denial strategies | These strategies seek to remove any connection between an organization and a crisis and includes flat out denial, attacking accusers, and transferring blame. |

| Diminish strategies | These strategies focus on reducing perceived responsibility and incorporates some level of justification or excuses. |

| Rebuilding strategies | These strategies focus on improving reputation through compensation and apologies. |

| Bolstering strategies | These strategies turn attention to existing goodwill and is meant to be a secondary strategy to the previous three groups. |

SCCT also holds strategies must be adapted to meet the needs resulting from attribution given to an organization. An emergency manager can initiate the response process with a threat assessment spanning crisis type, history, and prior reputation. Crisis type includes natural disasters to workplace violence to organization misdeeds (see Table 2 for all definitions). Depending on type, managers and communities will relate current activities to previous situations and gauge predilection for future events. Prior connections determine whether the community holds a negative or positive reputation for resilience capacity (Coombs 2014; Sherrieb, Norris, and Galea 2010).

Definitions of crisis typologies (Coombs 2014).

| Crisis type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Natural disasters | When an organization is damaged as a result of the weather or “acts of God” such as earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and bad storms. |

| Workplace violence | When an employee or former employee commits violence against other employees on the organization’s grounds. |

| Rumors | When false or misleading information is purposefully circulated about an organization or its products in order to harm the organization. |

| Malevolence | When some outside actor or opponent employs extreme tactics to attack the organization, such as product tampering, kidnapping, terrorism, or computer hacking. |

| Challenges | When the organization is confronted by discontented stakeholders with claims that it is operating in an inappropriate manner. |

| Technical-error accidents | When the technology utilized or supplied by the organization fails and causes an industrial accident. |

| Technical-error product harm | When the technology utilized or supplied by the organization fails and results in a defect or potentially harmful product. |

| Human-error accidents | When human error causes an accident. |

| Human-error product harm | When human error results in a defect or potentially harmful product. |

| Organizational misdeeds | When management takes actions, it knows may place stakeholders at risk or knowingly violates the law. |

This study focused on three crisis types: natural disasters, health epidemics, and community violence. Natural disasters were selected due to their prevalence in the United States (Disaster Survival Resources 2017; FEMA 2017). Community violence is an adaptation of workplace violence and organizational misdeeds where the act of violence is transferred from a workplace environment to a community, which is an increasing crisis in the United States, and incorporates actions of management, or community leaders, that may increase the risk for community members and potentially violate current laws (Coombs 2014). In the United States, civil unrest is arguably on the rise giving grounds to community related violence that incorporates violent crime, hate crimes, protests and riots (Buchanen, Bui, and Patel 2020; Bureau of Justice Statistics 2013; Cook 2017; Marable 2016; Sackett 2016). Health epidemic was included as an adaptation to human-error product harm as the United States has experienced health-related crises due to product tampering or biologically driven terrorism caused by individuals versus technology (Coombs 2014). Health epidemic was chosen due to the connection to public health concerns and risk communication. This has increased due to the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

Although the focus is on organizational reputation, SCCT is applicable to emergency management as crisis type affects preparation, mitigation, response, and recovery. If an emergency manager is aware of how they will respond to the crisis then they are more apt to pick a strategy that will positively impact their reputation, tailor messages to local community needs, and instruct specific stakeholders to circumvent negative consequences. Furthermore, knowing these strategies assists information recipients to better understand how the manager is viewing the incident and the guidance they will receive.

In conjunction with the manager’s response, crises impact communication needs and previous history, or experiences, affect how practitioners and communities will respond (Coombs 2014; Liu, Austin, and Jin 2011; Sherrieb, Norris, and Galea 2010; Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger 2017; Walker 2012). SCCT takes into consideration crisis clusters formed by integrating crisis type with attributions of crisis responsibility (Coombs 2014; Coombs and Holladay 2002). The Victim Cluster occurs when weak attributions occur for crisis responsibility and the organization is considered a victim. Accidental Cluster incorporates minimal attributions of crisis responsibility and the event is considered uncontrollable or unintentional by the organization. Intentional/Preventable Cluster incorporates strong attributions of crisis responsibility and the event is considered purposeful (see Table 3 for cluster and crisis type connections). Once this information is taken into account, an emergency manager can utilize SCCT to organize information into the components of instructing, sharing and adjusting and connect response strategies to the crisis situation (Coombs and Holladay 2002; Ulmer, Sellnow, and Seeger 2017).

Crisis type and strategy matching (adapted from Coombs 2014).

| Crisis response strategies | Crisis types |

|---|---|

| Victim cluster | Natural disaster |

| Rumor | |

| Workplace violence | |

| Product tampering/malevolence | |

| Accidental cluster | Challenges |

| Technical-error accidents | |

| Technical-error product harm | |

| Preventable cluster | Human-error accidents |

| Human-error product harm | |

| Organizational misdeed with no injuries or with injuries or management misconduct | |

| Deny strategies | Attack the accuser |

| Denial | |

| Scapegoat | |

| Diminish strategies | Excuse |

| Justification | |

| Rebuild strategies | Compensation |

| Apology |

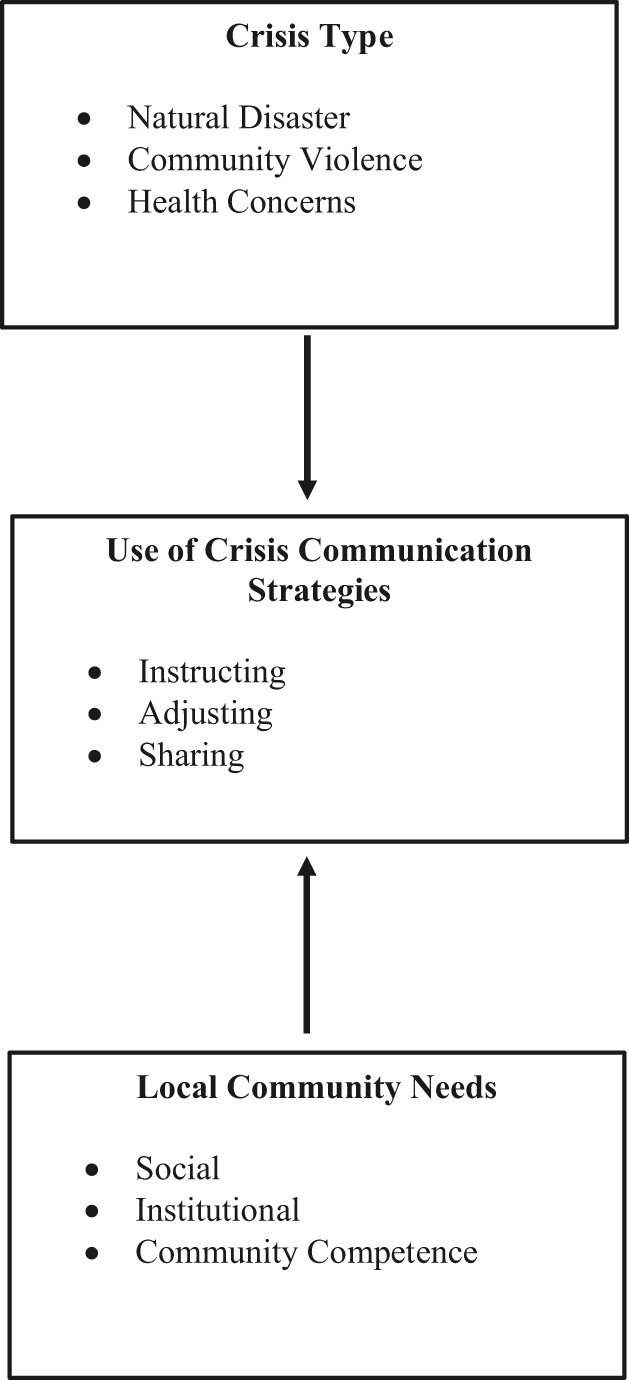

The following conceptual framework highlights the relationship between crisis communication strategies, crisis typology, and local community needs (see Figure 4). Within the visualization, the definitive lines represent direct effect from one variable onto another.

Conceptual framework.

4 Methodology

This paper utilizes results from a nation-wide study that examined the relationship between crisis communication strategies, local community needs, and perceived impact on resilience and is also theoretically based on SCCT emphasizing adaptability and importance of individuals within a community. The county level was selected as it is the lowest, most formalized level in the United States emergency management organizational structure (Cutter et al. 2008; FEMA 2015a, 2015b, 2016; Kapucu, Garayev, and Wang 2013). The survey of emergency managers was pivotal as they initiate preparation, mitigation, response and recovery activities and are considered the experts of their communities (Cutter et al. 2008; McGuire and Silva 2010; Okechukwu Okoli, Weller, and Watt 2014; Ross 2016; Waugh and Streib 2006). As discovered by Okechukwu Okoli, Weller, and Watt (2014), eliciting expert knowledge provides insight into information filtering, knowledge base and mental models, pattern matching, leverage points, and mental simulation. Information filtering calls to the ability of an expert to systematically review information for relevance and increase their cognitive capacity. Knowledge base and mental model speak to the ability to translate the information into a meaningful representation. Pattern matching alludes to the expert’s ability to relate a current situation to previous experiences and integrate into their actions. Leverage points speak to the ability to improvise and adapt to each new situation. Mental simulation is the ability of an expert to project their current situation to future events and plan accordingly.

4.1 Survey Distribution and Collection Period

The survey period occurred between July and August 2017. The survey was distributed to 2073 county level emergency managers and contained closed- and open-ended questions to understand practitioners’ perceptions of crisis communication and its strategies, local community needs, and community resilience. Hundred and ninety eight individuals opened the invitation and completed the survey and 191 responses were usable for analysis.

4.2 Survey Formulation

The survey instrument was a 68-item questionnaire, containing 5-point Likert style and open-ended questions, as well as demographic information. Also included was the option for follow-up interviews. Table 4 shows relevant questions and their connection to crisis communication strategies.

Survey questions and connections to crisis communication strategies and conceptual framework.

| Identifier | Question | Crisis communication strategy connection | Conceptual framework connectionb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2a | Which state are you located in? Please name your county. | LCN | ||

| Q3 | Which best describes your community? [ ] Urban [ ] Rural [ ] Other (please specify) | LCN | ||

| Q4 | Please note how recently your community has experienced the following crisis types: Natural disaster (earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, hurricanes) [ ] 1–3 years [ ] 4–6 years [ ] 7–10 years [ ] 11 or more years | Victim cluster | CT | |

| Q5 | Please note how recently your community has experienced the following crisis types: Health epidemic [ ] 1–3 years [ ] 4–6 years [ ] 7–10 years [ ] 11 or more years | Preventable cluster | CT | |

| Q6 |

Please note how recently your community has experienced the following crisis types: Community violence [ ] 1–3 years [ ] 4–6 years [ ] 7–10 years [ ] 11 or more years |

Victim cluster |

CT |

|

|

The following questions on Crisis Communication Strategies asked participants to state their agreement or disagreement with statements utilizing the scale: 5 – Strongly Agree; 4 – Agree; 3 – Neither Agree nor Disagree; 2 – Disagree; 1 – Strongly Disagree

|

||||

| Q7 | My department is mainly responsible for creating crisis communication plans and strategies | Instructing, adjusting, and sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q8 | My department exercises crisis communication strategies regularly | Instructing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q9 | My department exercises crisis communication strategies with community partners | Instructing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q10 | My department adapts information for natural disasters | Adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q11 | My department adapts information for health concerns | Adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q12 | My department adapts information for community violence | Adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q13 | My department focuses on information sharing between different community departments | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q14 | My department markets our plans on our websites | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q15 | My department markets our plans on other community partner’s websites | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q16 | My department markets our plans on flyers and posters | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q17 | My department markets our plans via social media | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q18 | My department provides updated information at least every hour during the event | Adjusting and sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q19 | My department provides updated information at least once every 3 h during the event | Adjusting and sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q20 | My department assesses our crisis communication plan at least once a year | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q21 | My department assesses our crisis communication plan with community partners | Instructing, adjusting and sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q22 | My department assesses our crisis communication plan with different community departments | Instructing, adjusting and sharing | LCN and CCS | |

|

|

||||

|

This following questions on Communication Avenues asked participants about the importance level for specific avenues to disseminate information about crises utilizing the scale: 5 – Very Important; 4 – Important; 3 – Don’t Know/Can’t Say; 2 – Unimportant; 1 – Not Applicable.

|

||||

| Q23 | Telephone notification | Instructing | CCS | |

| Q24 | National oceanic and atmospheric association radios | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q25 | Instructing and sharing | CCS | ||

| Q26 | Social networking | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q27 | Text messaging system | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q28 | Commercial radio stations | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q29 | Local television stations | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q30 | Outdoor warning sirens | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q31 | Distributing flyers where/when needed | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q32 | Community website (e.g. surge zone, evacuation route maps, shelters) | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q33 | Daily situation reports made available online and through mass emails | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q34 | Press conferences | Instructing and sharing | CCS | |

| Q35 |

Electronic signage |

Instructing and sharing |

CCS |

|

|

The following questions on Local Community Needs asked participants to state their agreement or disagreement with statements utilizing the scale: 5 – Strongly Agree; 4 – Agree; 3 – Neither Agree nor Disagree; 2 – Disagree; 1 – Strongly Disagree

|

||||

| Q36 | My department has a positive relationship with the community | Sharing | LCN and CCS | |

| Q37 | My department identifies what is most important for the community to know | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q38 | My department provides tailored messages for different cultures within the community | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q39 | My department provides communications in different languages for the community | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q40 | My department provides community outreach campaigns for vulnerable populations | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q41 | My department uses (easy-to-understand) language to explain what is going on | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q42 | My department uses visual images such as maps to help explain what is going on | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q43 | My department identifies the most important topics and highlights these in communication | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q44 | My department uses a spokesperson with whom the community is familiar | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

| Q45 | My department includes specific action to be taken by the community in each warning message | Instructing and adjusting | LCN and CCS | |

|

|

||||

|

This following questions on Community Resilience asked participants about the importance level for specific avenues to disseminate information about crises utilizing the scale: 5 – Very Important; 4 – Important; 3 – Don’t Know/Can’t Say; 2 – Unimportant; 1 – Not Applicable.

|

||||

| Q46 | Leadership support from the state emergency management practitioner(s) | CCS | ||

| Q47 | Leadership support from surrounding local emergency management practitioner(s) | CCS | ||

| Q48 | Trust with the community | CCS | ||

| Q49 | Providing emergency management training and certification opportunities for administrators | Instructing | CCS | |

| Q50 | Conducting routine assessments to update plans and procedures | Adjusting | CCS | |

| Q51 | Conducting routine needs assessments | Adjusting | CCS | |

| Q52 | Conducting comprehensive vulnerability assessments | Adjusting | CCS | |

| Q53 | Collaborating with community partners for support, expertise, etc. | Sharing | CCS | |

| Q54 | Personally participating in training and certification opportunities focused on emergency management | Instructing | CCS | |

| Q55 | In the absence of a crisis, sustaining relationships with other organizations | CCS | ||

| Q56 | In the absence of a crisis, being involved in collaborative strategies (such as exercises, and meetings) with organizations you collaborate with during a crisis | Instructing | CCS | |

-

aQuestion 1 consisted of asking the participant if they were the emergency manager. bFor Conceptual Framework Connections: CT, Crisis Type; LCN, Local Community Needs; CCS, Crisis Communication Strategies. cQuestions 57–60 were open ended questions asking for the participant’s level of expertise, anything they wanted to add that is critical for crisis communication, anything they wanted to add that is critical to community resilience, and if they had any documents or reports related to crisis communication and community resilience that they would like to share. dQuestions 61–69 concerned demographic information related to years worked in their position, jurisdiction, and public administration along with number of employees, gender, age, highest degree, field of highest degree, and if they were interested in a follow-up conversation. The follow-up interviews asked about the participant’s role and county they serve, aspects that support or hinder their crisis communication efforts, what positively or negatively impacts their county’s resilience, and anything else they wanted to add when thinking of communication and their county.

5 Results

The researcher utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine relationships between variables and focus on the strength of these relationships as well as their significance through tests of model fit and individual parameter estimates (Kaplan 2001; Kline 2015). In addition, open-ended questions were coded to identify patterns and themes. Results of the survey included demographic information of which 114 (67%) of the respondents were male, 41 (24%) were female, and 16 (9%) did not respond. As for age, the largest group was 56 or older with 73 (43%) followed by those 46–55 at 49 (29%), 36–45 at 21 (12%), 35 or Younger at 11 (6%), and did not answer at 17 (10%). In terms of highest degree earned by the respondent, 47 (28%) hold a Bachelor’s degree, 32 (19%) have trade/vocational/technical training, 31 (18%) hold a Master’s degree, 25 (15%) hold an Associate degree, 14 (8%) hold a high school diploma or equivalent, 5 (3%) hold a Doctorate, and 17 (10%) did not answer. For those who denoted the field of their highest degree, 71 (42%) selected other, 36 (21%) for Emergency Management, 15 (9%) Business Administration, 13 (8%) Public Administration, five (3%) Political Science, four (2%) Engineering, one for Sociology and 26 (15%) did not answer.

After validating the SEM model, parameter estimates were reviewed to determine the importance of each predictor in relation to its latent variable and the standardized regression weights were examined. What this tells us is indicate the nature and size of the relationship between variables in the study. Within Table 5 below, the parameter estimates for all survey components to showcase the strength of the effect of each individual independent variable to the dependent variable followed by Table 6 showcasing the most significant indicators.

Standardized regression weights for parameters.

| Parameters | Estimates | |

|---|---|---|

| Covariance structure model | Crisis communication strategies <-> Crisis type | 0.517 |

| Crisis communication strategies <-> Local community needs | 0.435 | |

| Community resilience <-> Crisis communication strategies | –0.451 | |

| Community resilience | Q26 – Leadership support from the state emergency management practitioner(s) | 0.309 |

| Q27 – Leadership support from surrounding local emergency management practitioner(s) | 0.550 | |

| Q28 – Trust with the community | 0.775 | |

| Q31 – Conducting routine needs assessments | 0.737 | |

| Q32 – Conducting comprehensive vulnerability assessments | 0.676 | |

| Q33 – Collaborating with community partners for support, expertise, etc. | 0.778 | |

| Q34 – Personally, participating in training and certification opportunities focused on emergency management | 0.758 | |

| Q35 – In the absence of a crisis, sustaining relationships with other organizations | 0.810 | |

| Crisis communication strategies | Q1 – My department is mainly responsible for creating crisis communication plans and strategies | 0.463 |

| Q2 – My department exercises crisis communication strategies regularly | 0.558 | |

| Q3 – My department exercises crisis communication strategies with community partners | 0.600 | |

| Q5 – My department markets our plans on our websites | 0.367 | |

| Q8 – My department markets our plans via social media | 0.290 | |

| Q10 – My department provides updated information at least once every 3 h during the event | 0.569 | |

| Q11 – My department assesses our crisis communication plan at least once a year | 0.659 | |

| Local community needs | Q14 – My department identifies what is most important for the community to know | 0.544 |

| Q17 – My department provides community outreach campaigns for vulnerable populations | 0.512 | |

| Q18 – My department uses (easy-to-understand) language to explain what is going on | 0.840 | |

| Q19 – My department uses visual images such as maps to help explain what is going on | 0.629 | |

| Q20 – My department identifies the most important topics and highlights these in communication | 0.794 | |

| Q21 – My department uses a spokesperson with whom the community is familiar | 0.545 | |

| Crisis type | Q23 – My department adapts information for natural disasters | 0.677 |

| Q24 – My department adapts information for health concerns | 0.737 | |

| Q25 – My department adapts information for community violence | 0.734 | |

Significant predictors of structural equation modeling analysis.

| Section | Significant indicators |

|---|---|

| Crisis communication strategies | My department assesses our crisis communication plan at least once a year (Q11) at 0.659 |

| My department exercises crisis communication strategies with community partners (Q3) at 0.600 | |

| My department exercises crisis communication strategies regularly (Q2) at 0.558 | |

| Local community needs | My department uses (easy-to-understand) language to explain what is going on (Q18) with 0.840 |

| My department identifies the most important topics and highlights these in communication (Q20) with 0.737 | |

| My department uses visual images such as maps to help explain what is going on (Q19) with 0.629 | |

| Crisis type | My department adapts information for health concerns (Q24) at 0.737 |

| My department adapts information for community violence (Q25) at 0.734 | |

| My department adapts information for natural disasters (Q23) at 0.677 |

With the interaction of crisis communication strategies, local community needs, and crisis types, participants were asked about their perception of their community’s resilience and the significant indicators leading to resilience. These indicators included sustaining relationships in an absence of a crisis, collaborating with community partners, trust with the community, personally participating in training and certification opportunities, and conducting routine assessments. In terms of mediating impact to Crisis Communication Strategies, Crisis Type was higher in significance at 0.517 with Local Community Needs at 0.435.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

This study focused on the use of crisis communication strategies in emergency management from the viewpoint of emergency managers. Crisis Communication is an evolving discipline with connections to public relations, business management and organizational psychology, and limited connection to emergency management despite its usefulness and practicality. The results of the study highlighted the pivotal role of emergency managers, the complex phenomena of communication and imperative nature of understanding local community needs and adaptation based on crisis type. SCCT’s prescriptive approach connects leaders’ response to communication strategies emphasizing adaptation to local community needs and crisis type. In theory, these strategies easily transfer and translate into practice, but not all the concepts are well-known. This is due to the fact that crisis communication plans are not created or fully implemented by emergency managers nor connected to their role. Instead, the responsibility is in departments like public relations or 9-1-1 operations. Therefore, the difficulty lies in disseminating the knowledge of these strategies to the emergency management and related practitioners.

Regarding open-ended questions, respondents were asked whether they wanted to share anything else that is critical for crisis communication and four themes emerged: relationships, adaptation, capacity, and crisis communication. In terms of relationships, respondents spoke to the necessity for collaboration, stakeholder buy-in, training and exercises, teamwork, sustaining relationships even after an event, and having connections with a variety of public, private, and individual entities. There was also an emphasis on understanding the role and responsibility of the emergency manager position in general. The negative result is also due to the complexity of emergency management roles and responsibilities, as many individuals surveyed are not decision-makers and do not contribute to plans of crisis communication on a deep level. Moreover, many county, and county-equivalents, in the United States do not have a full-time, dedicated emergency manager.

The theme of adaptation related to the necessity for integrating old and new communication technology, incorporating multiple communication avenues, and utilizing social media. Other responses consisted of making messages clear, dissemination to appropriate individuals, audience comprehension, timely distribution, and the need to address rumors. Regarding capacity, respondents spoke about the need to understand the county’s abilities during an event and the ones they work with. Moreover, an element of capacity linked to the emergency manager’s knowledge of their community and its history, the incident command structure, and the technology at their disposal. Essentially, it falls onto the emergency manager to place responsibility onto community and dictate actions to take.

The last theme was on crisis communication as a concept as well as the need for its growth in the field. This became evident when respondents asked for clarity of terminology and interactions between crisis communication strategies and emergency management practices. There were some terminological disconnects that surfaced in the open-ended questions. For example, some respondents answered that they utilized crisis communication strategies like adjusting information based on crisis type or sharing with leaders the community knows, yet their answers to open ended questions showed they did not realize these were actual strategies. This is not surprising as crisis communication strategies in emergency management work is not fully known.

In terms of characteristics and traits of an effective emergency manager, consistent responses of trust, transparency, consistency, perseverance, honesty, and competence were highlighted along with the importance of networking and sustaining/generating relationships with impacted stakeholders. Communication was discussed with a focus on the whole community approach and the requirement of stakeholder buy-in in conjunction with sustaining relationships. Moreover, respondents listed a number of obstacles, such as economics, disconnects between emergency managers and their leadership, designation or understanding of responsibility, accountability, traditional ideals of the emergency management role and attitude towards response, planning disconnects, and overcoming apathy.

Another issue is apathy within communities and practitioners. During interviews with several respondents, it was made clear that some of their counterparts do not give their full focus to the position as they are retiring, or these responsibilities are part of an ‘other duties as assigned’ classification. The apathy impacts crisis communication as the strategies hinge on the practitioner’s view and conceptual knowledge along with how they adapt information, share with stakeholders, and provide action plans. If they are apathetic then they may provide insufficient guidance and negative impact capacity building for their county. Moreover, the respondents felt undervalued as they are not invited to the policymaking table. Crisis communication strategies must include emergency managers in strategy development, exercises, and assessment processes.

6.1 Recommendations

Community leaders and policymakers need to understand the value and importance of emergency managers and for emergency managers to do the same. It should not fall to times of crises for these knowledgeable, skillful, and able individuals to be sought out. It must occur during the absence of crisis and be supported not only by voice but through resource attainment as well (i.e. budget, staff, materials, etc.). More importantly, these individuals need to be involved in decision-making and policy creation especially when it comes to creating and implementing crisis communication plans. They should not be responsible for a component of the process but should have a hand in all phases of information collection, organization, dissemination, instructing, adjusting, and sharing.

We must also acknowledge the importance of exercising crisis communication strategies regularly and with community partners. These partners not only include emergency managers and first responder agencies, but incorporates nonprofits, community leaders, advocates for vulnerable populations, and volunteer organizations. Enhancing the resilience capacity of our communities relies on the relationships sustained when a crisis is not occurring as well as collaboration with partners, maintaining trust with the community, continuing to participate in training and certification programs and continuous assessment of local community needs. These may seem like simple endeavors, but if an emergency manager is going to maintain the reputation of being an expert who effectively communicates with their community to prepare, mitigate, respond and recover from crises, then they must continue to develop their knowledge, skills, and abilities. The reality is, planning frameworks and training materials are only a part of the job. The true challenge lies in receiving buy-in from their communities and decision-makers to help generate more effective policies and procedures. When it comes to leadership and practice, it falls to all stakeholders to advocate for a seat at the table. To continue seeing a disconnect between practitioners, researchers and policymakers means continued barriers and challenges to the end goal of creating a resilient nation.

In terms of significant contributions to the field, this study was one of, if not, the first to incorporate Situational Crisis Communication Theory within a survey focused on emergency manager’s perception of crisis communication strategies, local community needs, and crisis type. The results also provide critical implications for emergency managers, policymakers, and related organizations. Furthermore, this study provides a foundation for future research to understanding how to integrate crisis communication strategies and Situational Crisis Communication Theory more fully into emergency and crisis management practice and to generate more comprehensive understanding of how local community needs and crisis type lead to necessary adaptations for crisis communication strategies. An additional future research area is to understand the role and value of emergency managers once more. Although they are theorized to be the experts, in practice the decision-making falls to public administrators or policy makers and does not always include the voice and knowledge of the emergency management practitioners. Lastly, a survey of public administrators and policymakers with the responsibility of decision-making in times of crises needs to be explored in terms of their inclusion of emergency manager voices and recommendations.

References

Allison, G. T., and P. Zelikow. 1971. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vol. 327, No. 729.1. Boston: Little, Brown.Suche in Google Scholar

Almond, G. A., S. C. Flanagan, and R. John Mundt. 1973. Crisis, Choice, and Change: Historical Studies of Political Development. Boston: Little, Brown.Suche in Google Scholar

Benoit, W. L. 1995. Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: A Theory of Image Restoration Strategies. New York, NY.: SUNY Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Benson, J. A. 1988. “Crisis Revisited: An Analysis of Strategies Used by Tylenol in the Second Tampering Episode.” Communication Studies 39 (1): 49–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/10510978809363234.Suche in Google Scholar

Bharosa, N., J. Lee, and M. Janssen. 2010. “Challenges and Obstacles in Sharing and Coordinating Information during Multi-Agency Disaster Response: Propositions from Field Exercises.” Information Systems Frontiers 12 (1): 49–65, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-009-9174-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Birkland, T. A. 2006. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change after Catastrophic Events. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.10.1353/book13054Suche in Google Scholar

Boin, A., and A. McConnell. 2007. “Preparing for Critical Infrastructure Breakdowns: the Limits of Crisis Management and the Need for Resilience.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 15 (1): 50–9, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2007.00504.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Buchanen, L., Q. Bui, and J. Patel. 2020. Black Lives Matter May be the Largest Movement in History. New York Times. July 10, 2020. Also available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2013. Violent Crime. March 28, 3018. Also available at https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=31.Suche in Google Scholar

Chandler, R. 2010. Emergency Notification. Santa Barbara, CA.: ABC-CLIO.10.5040/9798400644986Suche in Google Scholar

Comfort, L. K. 2007. “Crisis Management in Hindsight: Cognition, Communication, Coordination, and Control.” Public Administration Review 67: 189–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00827.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Comfort, L. K., and T. W. Haase. 2006. “Communication, Coherence, and Collective Action: The Impact of Hurricane Katrina on Communications Infrastructure.” Public Works Management & Policy 10 (4): 328–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724x06289052.Suche in Google Scholar

Cook, P. J. 2017. “Deadly Force.” Science 355 (6327): 803, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam5966.Suche in Google Scholar

Coombs, T. 2014. Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. Newbury Park, CA.: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Coombs, W. T., and S. J. Holladay. 1996. “Communication and Attributions in a Crisis: An Experimental Study in Crisis Communication.” Journal of Public Relations Research 8 (4): 279–95, https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr0804_04.Suche in Google Scholar

Coombs, W. T., and S. J. Holladay. 2002. “Helping Crisis Managers Protect Reputational Assets: Initial Tests of the Situational Crisis Communication Theory.” Management Communication Quarterly 16 (2): 165–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237233.Suche in Google Scholar

Cutter, S. L., C. G. Burton, and C. T. Emrich. 2010. “Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 7 (1): 1–24, doi:https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1732.Suche in Google Scholar

Cutter, S. L., L. Barnes, M. Berry, C. Burton, E. Evans, E. Tate, and J. Webb. 2008. “A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters.” Global Environmental Change 18 (4): 598–606, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013.Suche in Google Scholar

Department of Homeland Security. 2014. National Emergency Communications Plan. March 20, 2018. Also available at http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/2014%20National%20Emergency%20Communications%20Plan_October%2029%202014.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Disaster Survival Resources. 2017. US Disaster Statistics. March 30, 2018. Also available at http://www.disaster-survival-resources.com/us-disaster-statistics.html#.Suche in Google Scholar

Drabek, T. E. 1985. “Managing the Emergency Response.” Public Administration Review 45: 85–92, https://doi.org/10.2307/3135002.Suche in Google Scholar

Drabek, T. E. 2016. The Human Side of Disaster. Boca Raton, FL.: CRC Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Communications Commission. 2014. Emergency Communications Guide. March 30, 2018. Also available at http://www.fcc.gov/public-safetybanks.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2011. A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management: Principles, Themes, and Pathways for Action. March 30, 2018. Also available at http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1813-25045-0649/whole_community_dec2011__2_.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2015a. National Preparedness System. March 30, 2018. Also available at https://www.fema.gov/national-preparedness.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2015b. National Incident Command System. March 30, 2018. Also available at https://www.fema.gov/incident-command-system-resources.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2016. National Response Framework. March 30, 2018. Also available at https://www.fema.gov/national-response-framework.Suche in Google Scholar

Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2017. “Data Visualization: Summary of Disaster Declarations and Grants.” https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization-summary-disaster-declarations-and-grants (accessed December 3, 2017).Suche in Google Scholar

Flin, R. 1996. Sitting in the Hot Seat: Leaders and Teams for Critical Incident Management: Leadership for Critical Incidents. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Frandsen, F., and W. Johansen. 2016. Organizational Crisis Communication: A Multivocal Approach. Newbury Park, CA.: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Gamage, D. 2016. “Using Image Restoration and Situational Crisis Communication Theories for Effective Crisis Communication.” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 6 (5): 465–70.Suche in Google Scholar

Hearit, K. M. 1994. “Apologies and Public Relations Crises at Chrysler, Toshiba, and Volvo.” Public Relations Review 20 (2): 113–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/0363-8111(94)90053-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Hermann, C. F., ed. 1972. International Crises: Insights from Behavioral Research. New York, NY.: Free Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ice, R. 1991. “Corporate Publics and Rhetorical Strategies: The Case of Union Carbide’s Bhopal Crisis.” Management Communication Quarterly 4 (3): 341–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318991004003004.Suche in Google Scholar

Kailes, J. I., and A. Enders. 2007. “Moving beyond “Special Needs” A Function-Based Framework for Emergency Management and Planning.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 17 (4): 230–7, https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073070170040601.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaplan, D. 2001. Structural Equation Modeling. Oxford, England: Oxford University. Also available at www.stats.ox.ac.uk/∼snijders/Encyclopedia_SEM_Kaplan.pdf.10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/00776-2Suche in Google Scholar

Kapucu, N., and A. Özerdem. 2011. Managing Emergencies and Crises. Burlington, MA.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Kapucu, N., V. Garayev, and X. Wang. 2013. “Sustaining Networks in Emergency Management: a Study of Counties in the United States.” Public Performance and Management Review 37 (1): 104–33, https://doi.org/10.2753/pmr1530-9576370105.Suche in Google Scholar

Kelley, H. H. 1967. “Attribution Theory in Social Psychology.” In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln, NE.: University of Nebraska Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Klein, G. A. 1999. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA.: MIT press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kline, R. B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY.: Guilford Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Lebow, R. N. 1984. Between Peace and War: The Nature of International Crisis. Baltimore, MD.: Johns Hopkins University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, B. F., I. A. Iles, and E. Herovic. 2020. “Leadership under Fire: How Governments Manage Crisis Communication.” Communication Studies 71 (1): 128–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2019.1683593.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, B. F., L. Austin, and Y. Jin. 2011. “How Publics Respond to Crisis Communication Strategies: The Interplay of Information Form and Source.” Public Relations Review 37 (4): 345–53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.08.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Marable, M. 2016. Beyond Black and White: From Civil Rights to Barack Obama. Brooklyn, NY.: Verso Books.Suche in Google Scholar

McEntire, D. A. 2007. Disaster Response and Recovery: Strategies and Tactics for Resilience. Hoboken, NJ.: Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

McGuire, M., and C. Silvia. 2010. “The Effect of Problem Severity, Managerial and Organizational Capacity, and Agency Structure on Intergovernmental Collaboration: Evidence from Local Emergency Management.” Public Administration Review 70 (2): 279–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02134.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Mitroff, I. I., and T. C. Pauchant. 1990. We’re So Big and Powerful Nothing Bad Can Happen to Us: An investigation of America’s Crisis Prone Corporations. New York, NY.: Birch Lane Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Okechukwu Okoli, J., G. Weller, and J. Watt. 2014. “Eliciting Experts’ Knowledge in Emergency Response Organizations.” International Journal of Emergency Services 3 (2): 118–30.10.1108/IJES-06-2014-0009Suche in Google Scholar

Ozanne, L. K., P. W. Ballantine, and T. Mitchell. 2020. “Investigating the Methods and Effectiveness of Crisis Communication.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 32 (4): 379–405, https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2020.1798856.Suche in Google Scholar

Perry, R. W., and J. M. Nigg. 1985. “Emergency Management Strategies for Communicating Hazard Information.” Public Administration Review 45: 72–7, https://doi.org/10.2307/3135000.Suche in Google Scholar

Phillips, B. D., and B. H. Morrow. 2007. “Social Science Research Needs: Focus on Vulnerable Populations, Forecasting, and Warnings.” Natural Hazards Review 8 (3): 61–8, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)1527-6988(2007)8:3(61).10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2007)8:3(61)Suche in Google Scholar

Rosenthal, U., A. Boin, and L. K. Comfort. 2001. Managing Crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities. Springfield, IL.: Charles C Thomas Publisher.Suche in Google Scholar

Ross, A. D. 2016. “Perceptions of Resilience Among Coastal Emergency Managers.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 7 (1): 4–24, https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12092.Suche in Google Scholar

Sackett, C. 2016. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime. Washington, D.C.: Office of Policy Development and Research: US Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/summer16/highlight2.html (accessed March 30, 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Seeger, M. W. 2006. “Best Practices in Crisis Communication: An Expert Panel Process.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 34 (3): 232–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880600769944.Suche in Google Scholar

Seeger, M. W., T. L. Sellnow, and R. R. Ulmer. 2003. Communication and Organizational Crisis. Greenwood Publishing Group.Suche in Google Scholar

Sellnow, T. L., and M. W. Seeger. 2013. Theorizing Crisis Communication, 4. Hoboken, NJ.: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Sherrieb, K., F. H. Norris, and S. Galea. 2010. “Measuring Capacities for Community Resilience.” Social Indicators Research 99 (2): 227–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9576-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Sylves, R. 2014. Disaster Policy and Politics: Emergency Management and Homeland Security. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ulmer, R. R., T. L. Sellnow, and M. W. Seeger. 2017. Effective Crisis Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity. Newbury Park, CA.: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Walker, D. C. 2012. Mass Notification and Crisis Communications: Planning, Preparedness, and Systems. Boca Raton, FL.: CRC Press.10.1201/b11693Suche in Google Scholar

Waugh, W. L.Jr, and G. Streib. 2006. “Collaboration and Leadership for Effective Emergency Management.” Public Administration Review 66: 131–40, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00673.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Weiner, B. 1985. “An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion.” Psychological Review 92 (4): 548, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.92.4.548.Suche in Google Scholar

Wexler, B., and M-E. Smith. 2015. “Disaster Response and People Experiencing Homelessness: Addressing Challenges of a Population with Limited Resources.” Journal of Emergency Management (Weston, Mass.) 13 (3): 195–200, https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2015.0233.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Brittany Haupt, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Use of Crisis Communication Strategies in Emergency Management

- Stress Testing to Assess Recovery from Extreme Events

- Understanding Job Placement of Recent Emergency Management Graduates: An Initial Test of a Theoretical Framework

- Opinion

- COVID-19 Highlights Best Emergency Preparedness Approach: Lead by Example

- Book Review

- Claire Connolly Knox and Brittany “Brie” Haupt: Cultural Competency for Emergency and Crisis Management: Concepts, Theories, and Case Studies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Use of Crisis Communication Strategies in Emergency Management

- Stress Testing to Assess Recovery from Extreme Events

- Understanding Job Placement of Recent Emergency Management Graduates: An Initial Test of a Theoretical Framework

- Opinion

- COVID-19 Highlights Best Emergency Preparedness Approach: Lead by Example

- Book Review

- Claire Connolly Knox and Brittany “Brie” Haupt: Cultural Competency for Emergency and Crisis Management: Concepts, Theories, and Case Studies