Abstract

This study examines the relationship between the onset and progression of a chronic disease and subsequent income and employment trajectories using SHARE-RV, a longitudinal dataset that links survey data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) with German Pension Insurance administrative records (RV). This data linkage enables an assessment of the long-term consequences of chronic illness on labour market participation and income development, with observation periods exceeding 20 years. The empirical findings indicate that a chronic disease exhibit negative correlations with employment outcomes and earned income. These adverse effects differ in magnitude depending on the indicator used to define chronic disease and are most pronounced when restricting analyses to severe chronic conditions. Further, notable gender differences are observed. The spectrum of income losses ranges from moderate decreases in earnings points to the complete loss of earned income as a result of unemployment, labour market exit, or transition to disability pension receipt. The analysis also explores the extent to which chronic illness acts to intensify pre-existing labour market inequalities. The results indicate that the employment and income trajectories of highly qualified individuals are substantially less adversely affected by the onset and progression of chronic disease compared to those of individuals with low or medium levels of qualification. Indeed, highly qualified individuals may continue to accrue additional earnings points even following a chronic disease diagnosis. Consequently, chronic illness contributes to the amplification of social inequality within the labor market.

1 Introduction: Chronic Illness as a Risk to Employment and Income

In view of population ageing, the question of extending working lives will be of decisive importance in the coming decades in Germany. However, the debate is not only about whether employees will have to work until the ages of 67, 68, or even 70, but also whether they will be able to do so. Health is a crucial factor in this regard, as numerous studies show that it is among the most critical determinants for maintaining employment at older ages (Andersen et al. 2020; Blundell et al. 2023; Hasselhorn and Rauch 2013). Or in other words: poor health is one of the leading drivers of premature withdrawal from the labour market in Germany – predominantly, though not exclusively, among individuals with lower educational qualifications. Health-induced labour market exits are largely attributable to limited statutory pathways for early retirement. When individuals are ineligible for full or partial disability pensions, declining health often corresponds with periods of unemployment, economic inactivity, or marginal employment (Hagen and Himmelreicher 2020; Hofäcker et al. 2016; Rohrbacher and Hasselhorn 2022).

However, if health shocks, such as heart attacks, treatable cancers, or strokes are excluded, illness does not typically lead to an immediate and potentially permanent withdrawal from employment. On the contrary: non-communicable chronic diseases – such as arthritis, hypertension, or diabetes – are conditions with which individuals often live and work for many years (Dettmann and Hasselhorn 2020; OECD/EU 2016). To make matters worse, the incidence of chronic diseases among people of working-age is not a marginal phenomenon in Germany but affects a considerable proportion of workers. According to Dettmann and Hasselhorn (2020), approximately 49 % of employed men and 53 % of employed women report having at least one chronic illness, with prevalence increasing notably among older age groups (Schmidt et al. 2020). Unlike acute diseases, chronic conditions are rarely curable in a biomedical sense and are therefore characterised by long-term persistence and gradual progression.

Although chronic illness does not usually lead to an immediate withdrawal from employment, it often necessitates adjustments in working life, as the mere knowledge about its existence confronts those affected with the challenge of coping with both the chronic illness and working life, with its usually unchanged or even increasing work demands (Bartel 2018; OECD/EU 2016; Schaeffer and Haslbeck 2016). In this context, evidence from countries beyond Germany indicates that workers with chronic illnesses are more likely to reduce their working hours, change to another, possibly less stressful job or exit the labor market well before reaching statutory retirement age. In sum, chronically ill people not only show a lower employment rate, but also a lower average number of working hours than non-chronically ill (Oude-Hengel et al. 2019). However, the labour market problems of the chronically ill are not limited to people in employment. Rather, chronically ill people have considerable problems returning to work from unemployment or after a longer period of illness (OECD/EU 2016, 17–34; Van de Ven et al. 2023). Depending on the adjustment strategy, the occurrence of a chronic illness can have a negative impact on earned income and accompanying, on the individually acquired pension entitlements.[1] However, adjustment strategies do not have to be limited to the affected individuals and their self-selection processes in working life. In fact, employers can also select their sick employees out of the company or into another, possibly lower-paid (part-time) job.

Because of the long-term character of chronic diseases and the subsequent phenomenon of working with illness, it makes sense to look at as long a part of the employment biography as possible to obtain a differentiated picture of the effects of a successively deteriorating state of health on income. Such long-term effects of a chronic disease on earned income have not yet been systematically analysed for Germany. Instead, the focus is strongly on the factors promoting an early exit from the labour market or prolonging working life because of or rather despite a chronic disease (Hagen et al. 2017; Söhn and Mika 2015). The non-consideration of employment biographies was long mainly due to a considerable lack of suitable longitudinal data allowing analysing most of or at least a large part of the employment histories of the chronically ill people. This shortage situation has changed with the introduction of the SHARE-RV dataset, a record linkage between the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and administrative data from the German pension insurance (RV) making it possible to analyse the long-term effects of a chronic disease on employment and income trajectories taking into account the entire employment history. Given these new analytic possibilities, the paper adds to the research gap outlined above by firstly examining how onset and course of a chronic disease affect the employment and income history of the people affected in Germany (research question 1). Secondly, it is of interest whether the effects of a chronic disease on employment and income differ between qualification levels (research question 2). In general, there is no evidence – both internationally and nationally – regarding the question, if the kind of chronic disease makes a difference in terms of the labour market participation of chronically ill individuals.[2] The following analysis aims to contribute to closing this research gap by thirdly examining whether the labour market effects differ depending on the type of chronic diseases (research question 3). However, due to the low number of cases, it is not possible to consider single chronic diseases. Rather, two different sets of chronic diseases are considered.

The study contributes to the general literature on the correlation between health and labour market outcomes, and in this regard on the competing hypotheses of social causation and social selection (Kröger et al. 2015; Hoffmann et al. 2019). From a social policy perspective, evidence on the impact of chronic diseases on labour market trajectories is important for the discussion about suitable social protection as well as suitable support measures for chronically ill to remain in employment until reaching standard retirement age. Potential differences in the impact of ill health on income by qualification can partly explain the social gradient in health. Hence, the results will also provide evidence for the debate on health inequalities.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 describes the data, the operationalisation of health and illness, and the methods employed. Sections 4 and 5 report the empirical findings, with Section 4 presenting descriptive results and Section 5 fixed-effects regression estimates. The paper concludes with Section 6.

2 Literature and Hypotheses

In the literature about the labour market effects of deteriorating health, the interplay between health and work-related factors plays a decisive role (García-Gómez et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2020; Lenhart 2019; Lundborg et al. 2015; Siegrist and Dragano 2020; Vaalavuo 2021). However, the interrelation can be conceptualised from two different theoretical perspectives, the social causation and the social selection hypotheses (Hoffmann et al. 2019; Warren 2009). Following social causation, risks of morbidity and mortality depend largely on the socio-economic group or, more precisely, on the working conditions associated with socio-economic status. In this regard, a first strand of research examines the influence of certain characteristics of the employment relationship as receiving a low wage, having physically demanding working conditions, occupying a low hierarchical position and, related to this, having low autonomy of agency and decision-making to organise its own work. From this perspective, a change or deterioration in health is the phenomenon to be explained (Hoffmann et al. 2019; Siegrist and Dragano 2020). The second theoretical perspective, which is more decisive for answering the research questions posed in the introductory section, takes the selection hypothesis as a starting point, postulating that the individual’s state of health forms the basis for (work-related) self-selection processes. From this perspective, health is understood as explanatory variable for employment outcomes like a reduction of working hours, a change to a less demanding job or a permanent labour market exit. The present analysis is based on this theoretical perspective.

2.1 Deteriorating Health, Employment and Income

Regarding the effects of deteriorating health, literature for other European countries shows that onset and course of an illness has a negative impact on earned income of those affected (García-Gómez et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2020; Lenhart 2019; Lundborg et al. 2015; Vaalavuo 2021). Besides leaving employment permanently, further important adaptations are the reduction of weekly or monthly working hours or the change to a less demanding job. Following the selection hypothesis, the worker can initiate a reduction in working hours or a job change by itself in consequence of the chronical disease. From this perspective, adjustments are primarily due to self-perceived health-related restrictions making it difficult to continue working at the previous level or rather the previous job. Most of the respective research in this field confirms this theoretical perspective (Flüter-Hoffmann et al. 2017; García-Gómez et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2020; Vaalavuo 2021). However, a reduction in working time is not only be seen as a health necessity, but moreover as the result of individual preference shifts from working to leisure time – again in line with the selection hypothesis (Vaalavuo 2021). Furthermore, a health-related decrease in productivity and more frequent absences from work may result in the fact, that the employee in question being less considered for promotions (Lenhart 2019; OECD/EU 2016; Vaalavuo 2021). More frequent absence can, in extreme cases, also lead to dismissal, (long-term) unemployment or, only in the case of severe health limitations, to the receipt of a disability pension (De Boer et al. 2018; García-Gómez et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2020). However, to the best of my knowledge, there are no studies in Germany that examine the long-term effects of chronic illness on the employment and income trajectories of those affected. The following analysis contributes to this existing gap. In addition, the evidence from other European countries is often based on limited time series of 10 years or less and focuses on health shocks such as cancer, heart attacks, and strokes, which are significantly more likely to have short-term effects on the labour market (e.g., García-Gómez et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2020; Lenhart 2019; Vaalavuo 2021). From this perspective, too, an analysis of the long-term effects of chronic diseases represents an added value to the existing literature.

2.2 The Importance of Socioeconomic Status and Qualification

Regarding the importance of socioeconomic status in mitigating the employment-related consequences of deteriorating health, the literature primarily points to the moderating effect of educational and vocational qualifications as well as the occupational position (García-Gómez et al. 2013; Lundborg et al. 2015). Besides access to better medical care (Rosvall et al. 2008), differences in health literacy (Nutbeam and Lloyd 2021) and a more disciplined and correct adherence to medical treatment recommendations (Goldman and Smith 2002), differences in working conditions are a further explanation for the stronger impact of a disease on the employment and income trajectories of low-skilled workers. In this respect, a large part of the occupational activities performed by high-skilled workers is less physically demanding and more adaptable to individual needs (Islam et al. 2024). With regard to the probability of returning to work after cancer, a Meta study by Mehnert (2011) shows that factors associated with a greater likelihood of being employed after treatment, such as flexible working arrangements as well as the use of counselling, training, and rehabilitation services, are likely to vary by socioeconomic status and are much more common for high-skilled workers. Moreover, occupational activities requiring higher or even high qualifications have greater autonomy regarding the planning and organisation of work in general. Women with low socioeconomic status, for example, more often bear physically demanding tasks and are thus more impaired by their health condition than women with a high socioeconomic status who are more likely to be in a position to adjust their working conditions if necessary (Vaalavuo 2021). Both aspects contribute to the fact that activities requiring a high level of qualification are more likely to be performed in case of a deteriorating health than it is the case with manual activities (Dragano et al. 2016; García-Gómez et al. 2013; Lundborg et al. 2015). In addition, higher- or even high-skilled employees have better opportunities than lower-/low-skilled workers to change jobs or to reduce the workload (Lundborg et al. 2015). The empirical studies referred to here also focus primarily on recovery from cancer and thus on the consequences of a health shock (Garcia-Gómez et al. 2013; Lundborg et al. 2015; Mehnert 2011; Vaalavuo 2021). Other studies argue primarily from a social causation perspective without having reliable empirical longitudinal results ((Dragano et al. 2016); Nutbeam and Lloyd 2021). Studies that examine the long-term consequences of chronic illness depending on the qualifications of those affected are rare and, as already mentioned, limited in terms of the period under investigation. Accordingly, the analysis also contributes to the existing literature from this perspective.

2.3 Cumulative Disadvantages

From a social-inequality perspective, literature points to the fact that both differences in health and employment outcomes result from the cumulation of social disadvantages over the life course already starting in early childhood (Ferraro et al. 2016; Seabrock and Avison 2012). The idea underlying the concept of cumulative disadvantages “is that socioeconomic-based health inequalities will increase across the life course, mostly because of differential exposure to risk factors (e.g., smoking, diet) as well as access to protective resources (e.g., health care)” (Seabrock and Avison 2012, 52). Thus, people with a low socioeconomic status not only have a higher risk to get chronically ill but also exhibit a higher risk that health impairments worsen over time (Hoven et al. 2020). Thus, since poor and deteriorating health adversely affect the ability of individuals to engage fully in the labour market, it becomes increasingly difficult for health-impaired workers with a low socioeconomic status to remain in employment or re-enter the labour market (Hoven et al. 2020).

2.4 Hypotheses

Following the literature review it is assumed that onset und course of a chronic disease is negatively correlated with employment and, subsequent, earned income (hypothesis 1). However, the effects do not appear immediately after diagnosis, but over the course of the disease and with increasing age (hypothesis 2). Regarding the influence of socio-economic status, it is assumed that the higher the formal qualifications of affected individuals, the less pronounced the impact of chronic disease on employment and earned income (Siegrist and Möller-Leimkühler 2020). According to this reading, a chronic illness can be understood as an amplifier of social inequality in the labour market (hypothesis 3). Last, it is assumed that the effects of chronic diseases vary and that the exclusion of certain chronic diseases (high blood pressure, cholesterol, stomach ulcers) has a more significant impact on employment and income trends than the broader set of chronic diseases (hypothesis 4).

3 Data Set, Operationalisation and Methods

3.1 SHARE-RV

SHARE-RV is a dataset linking the survey data of the German subsample of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) with longitudinal data of the German Pension Insurance. Linkage is done using the national insurance number (Mika and Czaplicki 2010). The potential of SHARE for this study arises not only from the fact that it obtains detailed survey data on the individual health status of people aged 50 and older. Rather, in the third and seventh survey waves (2009 and 2017) retrospective data on employment and health biographies were collected (SHARE-Life), making it possible to identify the first occurrence of a chronic disease in the life course. Since the type of disease is also asked about, chronic diseases can not only be identified but also characterised. SHARE and the SHARE-Life module also contain a range of additional information on individual health, such as the health status in early childhood or information about the subjective perception of health.

The retrospective data on diagnosed diseases obtained in SHARE can be linked to administrative data from the German Pension Insurance containing almost complete employment histories. The administrative data is a sample of all persons between 14 and 65 years insured in the statutory pension insurance. The data also contains information on employment status and income for each year of the employment history. The inclusion of such biographical data allows to analyse income trends over the entire employment history aiming to trace interrelations between the onset and course of an illness and the subsequent employment and income history.

3.2 Operationalising Health and Illness

In accordance with the biopsychosocial model, health and illness should not be operationalised solely on the basis of objective criteria derived from medical assessment. It is instead crucial to also consider the subjective perceptions reported by individuals. In accordance with this understanding of health and illness, both objectively measurable health changes in the form of diagnosed diseases and subjectively perceived limitations resulting from health problems are included in the analysis. The objective state of health is operationalised by the diagnosis of a chronic disease (time of the first diagnosis). Within the retrospective module of SHARE-Life, participants are requested to report whether they have received a diagnosis for specific diseases and to specify the age at which the initial diagnosis occurred. Due to the use of retrospective data, the possibilities of including subjective health indicators in the analyses are limited since there are no corresponding retrospective questions on the subjective state of health. In order to be nonetheless able to depict the subjective dimension, an item is used asking about currently existing health problems due to (diagnosed) long-term diseases or other health problems.

Accordingly, the analysis is limited to individuals who report having been diagnosed with at least one chronic condition by age 50 and who additionally indicate the presence of persistent chronic or long-term health problems at the time of the survey. To exclude individuals who have never been employed or have only a limited employment history, a minimum of 15 years of work experience is required for inclusion in the analysis. Finally, it should be noted that only individuals born in 1948 or later are considered, as the institutional context for these cohorts aligns most closely with current retirement legislation.

Because the number of cases for specific chronic diseases resulting from this operationalisation is insufficient to permit separate analyses, the various chronic conditions are aggregated into a single composite indicator.(Table 1). It is important to note that the number of cases in the final indicator is smaller than the number of cases obtained by taking the sum of cases for the single chronic diseases due to multimorbidity. The control group consists of individuals not diagnosed with a chronic illness before reaching the age of 50. Based on the assumption that chronic illnesses primarily have a long-term impact on employment and income, it seems reasonable to include individuals being diagnosed with a chronic illness after the age of 50. In contrast, individuals diagnosed with a health shock (heart attack, cancer, stroke) before the age of 64 are excluded from both treatment and control group. As mentioned, two different indicators were considered to analyse the impact of chronic illness on employment and income of those affected. First, all chronic illnesses listed in Table 1 are summarized to a broader indicator (Chronic 1). For the construction of the second indicator (Chronic 2), high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol are excluded from the analysis. Stomach ulcers are also excluded, as these are often caused by a bacterial infection and often heal without treatment (Chronic 2).

Chronical diseases considered/excluded in the analyses.

| Number of cases | Relative importance in summarised indicator | |

|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | 627 | 30.5 |

| High cholesterol | 296 | 14.4 |

| Osteoarthritis | 204 | 9.9 |

| Diabetes | 160 | 7.8 |

| Chronic lung diseases | 147 | 7.1 |

| Emotional and affective disorders | 140 | 6.8 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 129 | 6.3 |

| Stomach ulcers | 99 | 4.8 |

| Arthritis | 77 | 3.7 |

| Chronic back pain | 49 | 2.4 |

| Chronic eye disease | 42 | 2.0 |

| Asthma | 26 | 1.3 |

| Mental illnesses | 22 | 1.1 |

| Fatigue | 18 | 0.9 |

| Osteoporosis | 9 | 0.4 |

| Chronic heart diseases | 8 | 0.5 |

| Morbus Parkinson | 4 | 0.2 |

| Chr. kidney disease | 1 | 0.1 |

| Total indicator | 2.058 | 100 |

| Reduced total indicators due to multimorbidity | ||

| Chronic 1 (sample of all chronic diseases) | 1.264 cases | |

| Chronic 2 (sample without high blood pressure, high cholesterol and stomach ulcers) | 750 cases | |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018.

3.3 The Income Indicator: Introduction to Earnings Points

For the income analyses, earnings points are used. The earnings points accumulated in the course of a working life are an important factor influencing the amount of the later old-age pension. To calculate earnings points, the individual’s earned income is set in relation to the average earnings in the respective year in Germany. Thus, earnings points are a relational value which, in addition to the information on the amount of the actual gross earned income (= earnings points in the respective year × average earnings), also reflects the relative earnings position of the respective worker in the German income hierarchy. Since 1 July 2024, the value of an earnings point has been €39.32 (Overview 1).

Overview 1: The calculation of earnings points (ep)

| Example for the calculation of earnings points: |

| Individual yearly income in 2024: 45.000 € |

| Average yearly income in Germany in 2024: 45.358 €1 |

| Individual earnings points in 2024: 45.000 €/45.358 € = 0.99 earnings points (ep) |

| Value of 1 earnings point in 2024: 39.32 € |

| Individual pension entitlement in 2024: 0.99 × 39.32 € = 38.93 € |

| Source: Own illustration; 1Value provisional |

Especially with longitudinal data covering the whole employment history, as is the case with SHARE-RV, the use of earnings points as indicator for the individual earned income offers analytical advantages since inflation is eliminated by referencing the average wage in each respective year. Thus, the incomes are comparable over time. However, the use of earnings points also has disadvantages. Firstly, income is only converted into earnings points up to a yearly adjusted income threshold. In 2024, the income threshold was an annual income of €89,400 in eastern and €90,600 in western Germany. The existence of an income ceiling implies that earnings exceeding this threshold are not accounted for in the calculation of earnings points. Consequently, potential income effects associated with chronic illness are likely to be underestimated among higher-income groups. However, this limitation only affects a relatively small proportion of employees. According to the Federal Statistical Office in Germany, the 90th percentile of gross annual earnings for full-time employees in 2024 was €97,680. If part-time employees are also taken into account, more than 90 % of all employees in Germany earn an income below the income threshold. A second limitation is that it is not possible to represent income from self-employment because of the earnings points, as this is not subject to social insurance. A change to civil servant status cannot be traced using the available data either. Overall, this problem appears to be less problematic, as such changes of occupation are not common in Germany.

3.4 Methods

3.4.1 Coarsened Exact Matching

Coarsened exact matching (CEM) is used to control for heterogeneity in the data, which can arise because neither the probability of disease nor the effects of disease on income and employment are randomly distributed, but are influenced by a variety of individual and societal factors (Iacus et al. 2011). In addition to the already outlined work-related factors, health-related variables such as childhood health status, health behaviour or in short cumulative disadvantage also plays an important role. Thus, the phenomenon of cumulative disadvantage is addressed by coarsened exact matching. Matched data is used in the descriptive analysis when comparing the development of earnings points between chronically ill and non-chronically people as well as when discussing reasons for the observable divergence in the development of earnings points. CEM adjusts for all covariates explicitly included in the matching process. Table 2 provides an overview of the variables incorporated in the coarsened exact matching procedure, as well as key sample distribution parameters. The analysis reveals that chronically ill individuals are disproportionately female, possess lower qualifications, have spent most of their working lives in Eastern Germany, and more frequently report childhood health problems. Furthermore, higher rates of smoking are observed among the chronically ill and especially among the severely chronical ill. Thus, several established risk factors identified in the literature are also evident within the present sample.

Items considered in coarsened exact matching; descriptives; within-group distribution.

| Chronically ill (chronic 1) (chronic 2) |

Non-chronically ill | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 54.4 %; 687 cases (58.9 %; 442 cases) |

52.7 %; 1.613 cases |

| Men | 45.7 %; 577 cases (41.1 %; 308 cases) |

47.3 %; 1.449 cases |

| Low qualification | 12.2 %; 154 cases (13.4 %; 100 cases) |

11.5 %; 349 cases |

| Average qualification | 58.8 %; 745 cases (59.6 %; 446 cases) |

58.7 %; 1.783 cases |

| High qualification | 29.6 %; 364 cases (27.1 %; 203 cases) |

29.9 %; 908 cases |

| Poor health in childhood | 15.7 %; 198 cases (17.5 %; 131 cases) |

8.8 %; 269 cases |

| Long-term illness in childhood | 19.5 %; 246 cases (20.9 %; 157 cases) |

14.1 %; 433 cases |

| Ever smoked (yes) | 52.8 %; 667 cases (55.5 %; 416 cases) |

48.6 %; 1.476 cases |

| Still smoker (yes) | 22.8 %; 288 cases (25.5 %; 191 cases) |

20.4 %; 624 cases |

| Working life in East Germany | 26.2 %; 331 cases (23.5 %; 176 cases) |

21.6 %; 661 cases |

| Average earnings points at the age of 35 | 11.0 EP; 1.264 cases (10.7 EP; 750 cases) |

11.3 EP; 3.062 cases |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018.

3.4.2 Fixed Effects Regression

Besides descriptive analyses, fixed-effects regression is used to analyse the interplay between the onset (and later the course) of a chronic illness on the one hand, and the realised individual earned income on the other hand. Fixed-effects estimators are used in panel data analysis to control for all unobserved, time-invariant characteristics of individuals. The approach focuses on within-individual variation over time by examining how changes in time-varying variables are associated with changes in the outcome, effectively holding constant all time-invariant individual factors. Accordingly, the fixed-effects regression approach is highly appropriate for examining the central research question, namely whether chronic illness exerts an adverse influence on the trajectory of income development. Nonetheless, the fixed-effects approach exhibits methodological limitations when the focus lies on time-invariant variables, such as qualifications in the present study, since these factors cannot be directly estimated within the model. However, by interacting a time-invariant variable with a time-varying variable (such as chronic illness), it becomes possible to estimate the differential impact of the time-varying variable across levels of the time-invariant characteristic. This methodological strategy allows to analyse whether the effect of a chronic illness differs by qualification level, even when qualification itself does not change over time (Giesselmann and Schmidt-Catran 2022).

4 Results: The Long-Term Impact of Chronic Illnesses on Income and Employment Histories

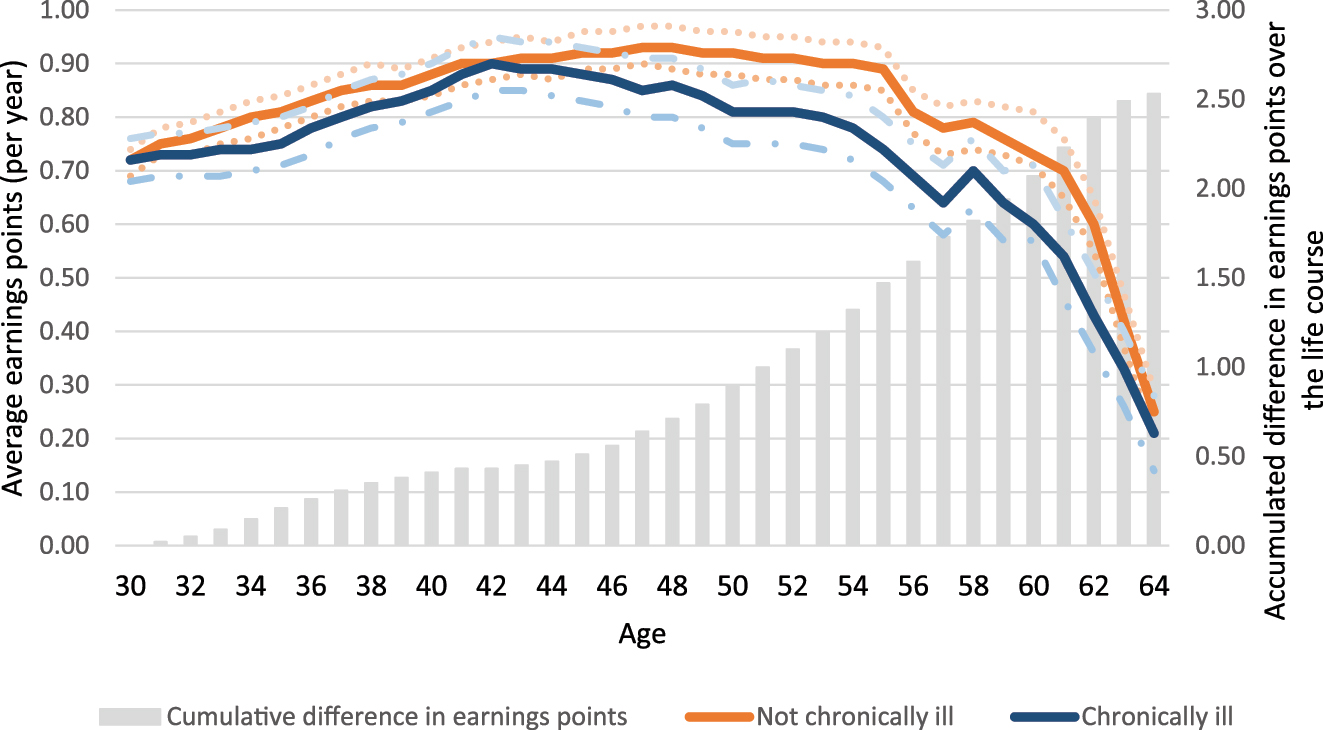

The following section shows the results on the long-term effects of chronic illnesses on income and employment trajectories. Figure 1 thereby compares the income development of chronically ill (all chronical diseases; chronic 1) with that of people not diagnosed as chronically ill up to the age of 50. In addition to the average number of earnings points, the cumulative difference in earnings points between the chronically ill and non-chronically ill is considered, serving as an indicator for the long-term economic consequences of the disease while the former indicates the consequences in each year of the observational period. Regarding the results, Figure 1 shows that after a largely similar development of earnings points during the first 10–12 years, differences between the chronically ill and non-chronically ill begin to widen from the mid-40s onward. In addition to the expected more severe effects of chronic diseases, this development can be explained by the fact that more and more people become chronically ill as they age.

The development of individual earning points for chronically ill and not chronically ill individuals; diagnosis up to the age of 50; all chronic diseases (chronic 1). Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.1; data from 2018; employed for at least 15 years; no health shock up to the age of 65; matched data is used; dotted lines: confidence bands.

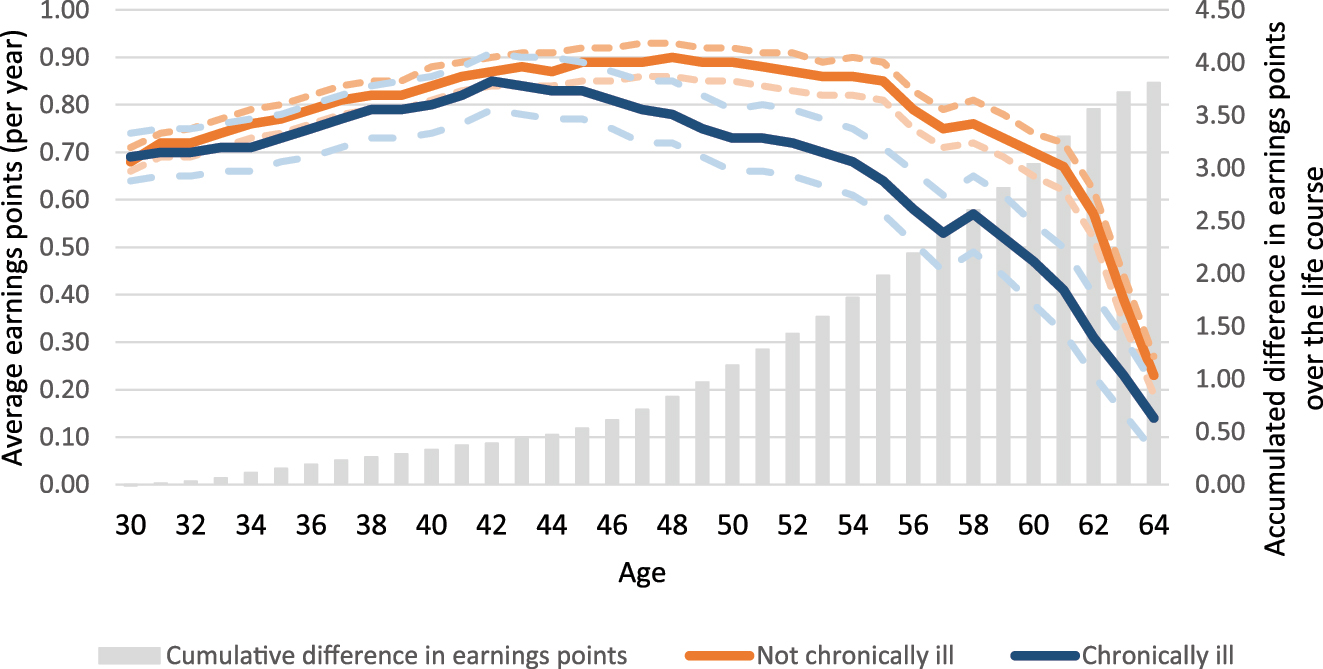

The development of individual earning points for men diagnosed as chronically ill and men not diagnosed as chronically ill up to the age of 50; selected chronic diseases (chronic 2). Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.1; data from 2018; employed for at least 15 years; no health shock up to the age of 65; matched data is used; dotted lines: confidence bands.

The reason for this growing divergence is a stronger decline in earnings points for the chronically ill becoming more pronounced with age and resulting in a cumulative difference of 1.94 earnings points up to the age of 59. After age 60, both curves gradually align due to the rising entry into (early) retirement among both ill and healthy individuals. Given the average national income in Germany for 2024 (Overview 1), 1.94 earnings points correspond to an inflation-adjusted reduction in income of around 88,000 € since the onset of the chronic illness. With more severe chronic illness (chronic 2; Figure 2), earnings points drop more sharply, leading to a cumulative difference of 2.81 by age 59, which translates to an inflation-adjusted income loss of about 127,500 €.

4.1 Reasons for the Growing Divergence of Earnings Points

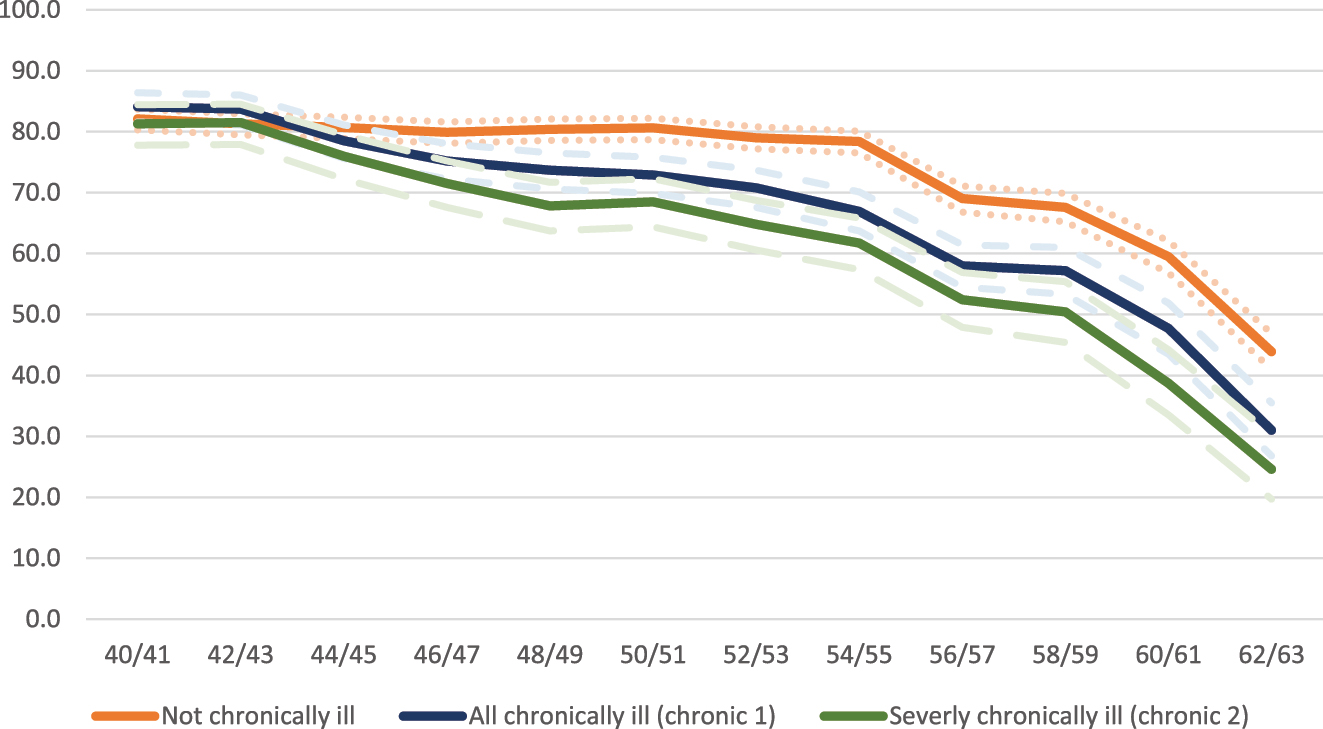

Figure 3 illustrates that a decline in employment among the group of the chronically ill is decisive for the growing divergence of earnings points. This is evident in both chronic 1 and chronic 2. However, the decline is more pronounced in more severely chronic illnesses. Starting from almost identical levels of employment at the age of 40/41, the employment rate of both groups of chronically ill decreases considerably stronger than it is the case in the group of the non-chronically ill.

Proportion of individuals in insured employment by chronic illness status (in percent). Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; employed for at least 15 years; no health shock up to the age of 65; age range 40/41 to 62/63 years; dotted lines: confidence bands.

Regarding alternatives to employment, Table 3 shows an increase in unemployment over time. At the age of 40/41, 5.8 % of the chronically ill (chronic 1) and 6.6 % of the more severely chronical ill are registered as unemployed. Up to the age of 50/51, the proportion increased by about 5 percentage points in both groups up to 10.2 % (chronic 1) and 11.2 % (more severely chronically ill; chronic 2). In contrast, the unemployment rate of the non-chronically ill only increased by 1.5 percentage points. The proportion of unemployment in both groups of the chronically ill, however, slightly declines in the 50s and is 9.3 % (chronic 1) and 10.8 % (chronic 2) at the age of 58/59. However, the reason for this decline is not a higher employment rate (this decreases continuously to 57.2 % (chronic 1) and 50.4 % (chronic 2) up to the age of 58/59). Rather, the decline in unemployment is accompanied by a rising number of chronically ill individuals receiving a disability pension. Between the ages of 50/51 and 58/59, the proportion of disability pensioners among the chronically ill increases from 2.1 % (chronic 1)/4.2 % (chronic 2) at the age of 50/51 to 13.2 % (chronic 1) and 15.3 % (chronic 2) among 58/59-year-olds.

Comparative employment status of chronically ill and non-chronically ill individuals by age; birth cohorts from 1948 onwards (percentages).

| Employment status | Employment status of chronically ill (CI, chronic 1), severely chronically ill (SCI, chronic 2), and non-chronically ill (NCI) people at the age of … | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40/41 years | 50/51 year | 58/59 years | |||||||

| CI | SCI | NCI | CI | SCI | NCI | CI | SCI | NCI | |

| Employment | 84.1 | 81.3 | 82.1 | 72.9 | 68.5 | 80.7 | 57.2 | 50.4 | 67.8 |

| Marginal employment | / | / | / | 3.5 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 2.9 |

| Unemployment | 5.8 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 10.8 | 8.9 |

| Disability pension | / | / | / | 2.8 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 13.2 | 15.3 | 8.8 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018, employed for at least 15 years; no health shock up to the age of 65; age range 40/41 to 62/63 years. It should be noted that Table 2 presents only those statuses with a sufficiently large number of cases; as a result, the proportions do not sum to 100 %.

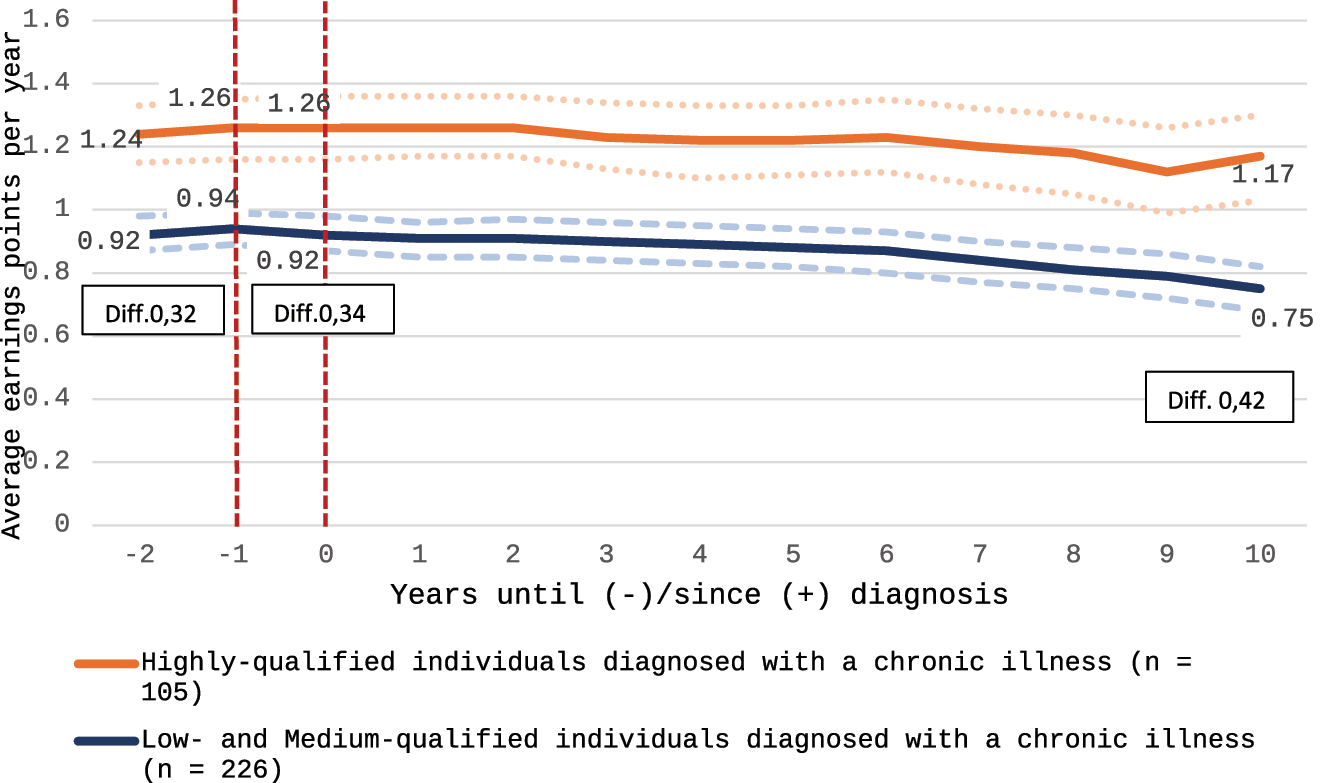

4.2 Significance of the Qualification

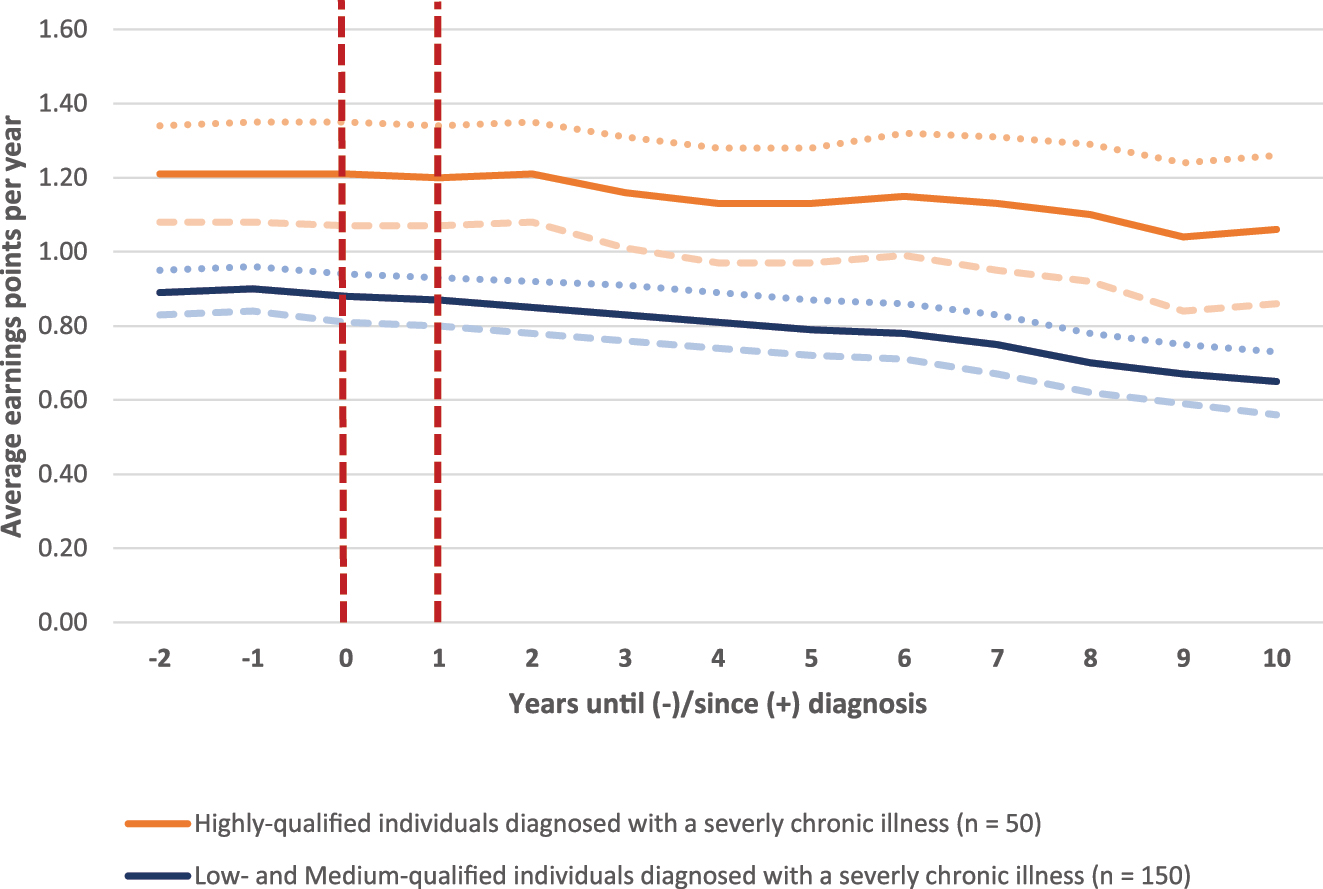

To better understand the role of educational qualifications in moderating the effects of chronic illness, the following analysis examines the development of earnings points among individuals with chronic conditions, stratified by qualification level. Respondents’ qualifications are classified according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).[3] The sample includes only individuals employed and subject to social insurance contributions in the two years preceding illness onset. Figure 4 reveals that the onset and progression of a chronic condition (chronic 1) differentially affect qualification groups. For individuals with high qualifications, earnings points are stable at 1.26 prior to diagnosis but decrease gradually to 1.17 over the subsequent ten years – a total reduction of 0.09 earnings points. In contrast, those with low or medium qualifications experience a more substantial and steady decline, with earnings points falling from 0.92 to 0.75, thus widening the qualifications gap from 0.34 to 0.42 earnings points since illness diagnosis. Accordingly, among highly qualified individuals, the chronic 1 indicator is associated with only a modest diminution in average earnings points subsequent to illness onset. In contrast, the indicator capturing more severe chronic conditions (chronic 2) indicates that both onset and course of these illnesses are associated with a distinctly greater and more persistent reduction in earnings points.[4] Starting from an average of 1.21 earnings points one year before diagnosis, mean earnings points decrease to 1.06 over the subsequent ten-year period, indicating a reduction of 0.15 points.

Effects of diagnosed chronic illnesses on earning points depending on qualification; average EP before and after diagnosis of chronic disease; 2 years of insured employment before diagnosis mandatory; no health shock up to the age of 65; birth cohorts from 1948 upwards; indicator is chronic 1. Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; dotted lines: confidence bands.

In contrast, the corresponding decline among individuals with any chronic condition (chronic 1) is only 0.09 earnings points. However, the decline is even steeper among low- and medium-qualified individuals (from 0.88 to 0.65 earnings points). Although earnings points also exhibit a more persistent decline among highly qualified individuals under chronic 2 relative to chronic 1, the qualification gap widens over time, increasing from 0.31 earnings points prior to diagnosis to 0.41 after 10 years.

Overall, the results suggest that the ability to compensate illness-related limitations diminishes markedly in the case of more severe chronic diseases for both highly qualified and low- and medium-qualified individuals. However, the decline is notably more pronounced among individuals with low and medium qualifications. This leads not only to a widening wage gap between the two comparison groups but also indicates that the most pronounced employment effects of severe chronic illness (chronic 2) occur among low- and medium-qualified individuals. This pattern likely reflects reduced opportunities within these qualification groups to adjust occupational tasks or workloads to the constraints imposed by illness. Consequently, maintaining employment while managing a severe chronic condition appears comparatively less feasible for these individuals than for those with higher qualifications. However, this indicator does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding a potential increase in income inequality, as it remains uncertain how earnings disparities between qualification groups would have developed in the absence of a diagnosis. It is, for example, conceivable that the faster wage progression typically observed among highly qualified individuals could have produced an even larger gap in earnings points. Therefore, whether chronic illness actually amplifies social inequality requires verification through a fixed-effects regression model. Nonetheless, the findings offer at least partial descriptive support for the hypothesis that chronic illness functions as a driver of social inequality. Furthermore, it should be noted that the confidence intervals for the earnings trajectories of highly qualified individuals shown in Figure 5 are comparatively wide due to the limited sample size, implying that these results should be interpreted with caution.

Effects of diagnosed chronic illnesses on earning points depending on qualification; average EP before and after diagnosis of chronic disease; 2 years of insured employment before diagnosis mandatory; no health shock; birth cohorts from 1945 upwards; indicator is chronic 2. Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; dotted lines: confidence bands.

4.3 Business as Usual, Career Brake or Career Killer

The preceding descriptive analysis has shown that the onset and progression of chronic illness can influence both employment participation and income trajectories among the individuals concerned. However, the exact proportion of chronically ill individuals experiencing income declines after diagnosis remains uncertain. Table 4 sheds light on this issue by showing that individuals with higher qualifications and chronic illness are less likely to incur significant income losses than those with low or medium qualifications. This disparity is particularly pronounced among individuals afflicted with severe chronic conditions, which serves to strengthen previous findings. For example, over one quarter (25.7 %) of low- and medium-qualified individuals with any chronic illness experience reductions in average earnings points exceeding 20 % compared to the five years prior to diagnosis, a proportion that rises to 32.7 % among those facing severe illness. In contrast, analogous declines are observed in only 16.6 % of highly qualified individuals with chronic illness and 23.8 % among those with severe conditions. Despite these qualifications-specific vulnerabilities, a notable share of people with chronic illness do not incur any income loss, indicating that for this group, continued employment constitutes a relatively stable situation, or “business as usual”.

The extent of income loss following the diagnosis of a chronic illness.

| Reduction/Increase of average earnings points (ep) compared to the 5 years before diagnosis | All chronic illnesses (chronic 1) | More severely chronical illnesses (chronic 2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low- and average qualification | High qualification | Low- and average qualification | High qualification | |

| Reduction of more than 20 % | 25.7 | 16.6 | 32.7 | 23.8 |

| Reduction up to 20 % | 23.7 | 24.8 | 21.1 | 24.6 |

| Stagnation (0–9 % increase) | 18.3 | 22.1 | 15.8 | 20.5 |

| Increase between 10 and 24 % | 12.9 | 15.4 | 13.3 | 10.7 |

| Increase of 25 % and more | 19.4 | 21.3 | 17.2 | 20.5 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018.

It should be noted, however, that a deceleration in income dynamics, as indicated by the analyses for highly qualified workers in the preceding section, likewise approximates a negative income effect and may thus be regarded as a brake on career progression. Moreover, it is important to recognise that a substantial share of chronically ill individuals experience income losses within 10 years following diagnosis. Among those with low and medium qualifications, 49.4 % (chronic 1) and 53.8 % (chronic 2) are affected, while the corresponding proportions among highly qualified individuals are 41 % (chronic 1) and 48 % (chronic 2). For these individuals, chronic illness functions as a ‘career brake,’ and over the long term, it constitutes a premature ‘career end’ for a significant subset of those affected.

5 The Long-Term Effects of Diagnosed Chronic Diseases on Income Trajectories

The following section assesses whether the patterns identified in the descriptive analysis remain evident within a multivariate framework. Annual earned income, operationalised as earnings points, serves as the dependent variable. The principal research objective is to determine whether a chronic disease negatively affects earnings points. Control variables are introduced sequentially across Models 1 to 3, as detailed in Table 5.[5]

Controls in the different fixed-effects regression models.

| Coding | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| Health shock | 0/1 | 1 = Phases after diagnosis of a health shock |

| Chronic illness | 0/1 | 1 = Phases after diagnosis of a chronic illness |

| Age | Metric | 2 Indicators: age (mean centred); age (squared) |

| Time since diagnosis (chronic illness) | Metric | Considers that a chronic illness can onset at different ages |

| Second chronic illness | 0/1 | 1 = Phases after diagnosis of a second chronic illness |

| Duration of the chronic illness | Metric | Time since onset of the chronic illnesses |

| Duration of health shock | Metric | Time since onset of health shock |

| Qualification | 0/1 | 1 = High skilled people; via interaction term |

| Year | 0/1 | Dummy variable for the respective calendar year |

| Model 2 (in addition) | ||

| Married | 0/1 | 1 = Phases in which person is married |

| Children | 0/1 | 1 = Phases with children up to the age of 14 in the household |

| Divorced | 0/1 | 1 = Phases in which person was divorced |

| Partner’s earnings points | Metric | Difference between household and individual earning points |

| Model 3 (in addition) | ||

| Job change | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of job change |

| Full-time employment | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of full-time employment |

| Part-time employment | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of part-time employment |

| School | 0/1 | |

| Vocational training | 0/1 | |

| Other status | 0/1 | |

| Unemployment | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of unemployment |

| No information | 0/1 | 1 = Phases without employment or status information |

| Periods of illness | 0/1 | 1 = periods of receipt of statutory sickness benefits |

| Marginal employment | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of marginal employment |

| Family work | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of family work (childcare, care of relatives) |

| Disability pension | 0/1 | 1 = Phases of drawing a disability pension |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018.

Table 6 presents estimation results for chronic 1, while Table 7 contains the corresponding findings for chronic 2. The analysis is conducted separately for women and men in order to account for potential gender differences. Three distinct models are estimated throughout this analysis. Model 1 includes only individual-level control variables, as detailed in Table 4. Model 2 extends the specification by incorporating household-related factors. In the final model, employment-related variables are introduced to evaluate whether the observed effect of chronic illness attenuates when periods of unemployment or receipt of disability pension are accounted for. A reduction in the effect would suggest that alternative employment pathways, such as diminished working hours, may substantially contribute to explaining the observed income losses. The coefficients of control variables are not reported here but can be found in Appendix Tables A1 and A2. The regressions use a composite indicator of chronic diseases (Table 1).

Effects of health changes on earning points; all chronic illnesses (chronic 1).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Chronic disease | −0.050* | −0.085** | −0.056** | −0.107*** | −0.032** | −0.066*** |

| Health shock | −0.125*** | −0.124** | −0.118** | −0.110** | −0.004 | −0.013 |

| Age (mean centred) | 0.002*** | 0.015*** | 0.000 | 0.010*** | 0.000 | 0.009*** |

| Age (mean centred) × chronic disease | −0.007*** | −0.017*** | −0.008*** | −0.012*** | 0.000 | −0.002 |

| Chronic illness × high qualification | 0.196*** | 0.357*** | 0.187*** | 0.354*** | 0.091** | 0.178*** |

|

|

||||||

| Specifications | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 |

| Cases | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 |

| R 2 (within) | 0.076 | 0.25 | 0.093 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; separate calculations for women and men; Men: at least 15 years of insured employment; Women: at least 10 years of insured employment; Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; for a table presenting all coefficients, see Appendix Table A1.

Effects of health changes on earning points; more severe chronic illnesses (chronic 2).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| More serious chronic illness | −0.083** | −0.081* | −0.089*** | −0.105** | −0.058*** | −0.041 |

| Health shock | −0.125*** | −0.145*** | −0.119** | −0.128** | −0.004 | −0.077 |

| Age (mean centred) | 0.001*** | 0.015*** | −0.001 | 0.010*** | 0.001 | 0.009*** |

| Age (mean centred) × chronic disease | −0.007** | −0.019*** | −0.008** | −0.013*** | −0.001 | −0.003 |

| Chronic illness × high qualification | 0.255*** | 0.239** | 0.249*** | 0.250** | 0.133*** | 0.077 |

|

|

||||||

| Specifications | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,716 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 |

| Cases | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 |

| R 2 (within) | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; separate calculations for women and men; Men: at least 15 years of insured employment; Women: at least 10 years of insured employment; Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; for a table presenting all coefficients, see Appendix Table A2.

In a first step, the effect of deteriorating health on earnings points is estimated, including interactions with qualification and with age, as the health-related gap in earnings points widens over the life course. Men are included with at least 15 years of employment, women with at least 10 years, reflecting gender differences in labour market participation in Germany. All models employ robust standard errors.

The estimation results indicate a significant negative association between both the onset and progression of chronic illness and subsequent earnings points trajectories among women and men, consistently evident across all model specifications and measures of chronic illness. Accordingly, the regression findings substantiate the patterns observed in the descriptive analysis. The most notable finding is the markedly stronger negative effect among women when comparing results for all chronic illnesses (chronic 1) with those for more severe chronic illness, with the latter showing a substantially greater adverse impact on earnings points in all three models. In contrast, among men, the magnitude of the effect shows little variation by illness severity.

For individuals experiencing a health shock (control), a significant association is observed for both women and men in Models 1 and 2, but this effect dissipates in the final model. Since Model 3 accounts for the receipt of a disability pension, marginal employment, and unemployment, it appears that most of the income variation following a health shock is attributable to transitions from employment to alternative social statuses rather than continued employment. Consistent with prior literature, chronic diseases differ in that they typically do not compel affected individuals to leave employment outright; if employment is relinquished, it tends to occur later in the individual’s work history. Notably, severe chronic illness among men represents an exception and, in this regard, constitutes a relatively new contribution to the existing body of research.

The significantly positive coefficient for the interaction between qualification and chronic illness among both women and men clearly underscores the hypothesized selective effect of chronic illness on income. Specifically, this positive interaction indicates that the otherwise negative impact of chronic illness on income is offset for individuals with high qualifications. Explanation: by implementing the interaction effects between high qualification and chronic illness as well as between age and chronic illness, the indicator “chronic illness” only shows the effect for average-aged women and men with low or medium qualification. The effect for highly skilled people is obtained by summing the effects “chronic disease” and “chronic disease*high qualification” turning the coefficient for the highly skilled people in each of the models positive. For example: The moderating effect of a high qualification in Model 3 for women is calculated as follows: −0.057 + 0.132 = 0.075. Thus, a chronic disease can clearly be seen as an amplifier of social inequality on the labour market since no negative income effects due to the onset of a chronic illness can be identified for highly qualified people. On the contrary: the corresponding coefficients remain positive. Hence, chronic illness cannot be characterised as a “career killer” among the highly qualified, although it does partly slow income progression. For this group, chronic illness appears to function more as a career brake – or, in some cases, as business as usual – rather than a career-ending event. This is different for people with low or medium qualifications showing a clearly negative income effect after the onset of a chronic disease. However, the compensatory effect associated with a high level of qualifications is observed to be significantly diminished in cases involving severe chronic illnesses compared to analyses including all chronic conditions. Consequently, negative income effects are more likely to manifest when the chronic illness is classified as severe, since variation according to disease progression remains relevant.

This suggests that, for men, labour market exit plays a more pivotal role in explaining income losses following a severe chronic illness, whereas continued employment with reduced hours or workload appears to be less influential than it is the case when all chronic illnesses are taken into account. In contrast, the third model also identifies a significant negative effect of severe chronic illness among women. The ability to remain in employment, and thus to adapt to and cope with more serious chronic conditions, appears to constitute a potentially viable strategy for women in managing the challenges associated with such illnesses.

It should be noted that annual earnings points are calculated only up to the contribution assessment ceiling for social insurance in Germany, which in 2025 is set at €96,600 per year. Variations in income above this threshold are not captured with this indicator. This means that income losses occurring exclusively above the ceiling for highly qualified individuals may not be reflected in the results. Consequently, the observed positive interaction effect between qualification and chronic illness should be interpreted with some caution. Nevertheless, the significant positive interaction effect between qualification and chronic illness remains robust for those individuals whose incomes vary within the contributory range. For this group, the observed association – that highly qualified individuals are less affected by negative income effects following the onset of chronic disease – can be considered a reliable finding. It should simply be kept in mind that the results pertain to the portion of income that is subject to social security contributions.

6 Conclusions: Chronic Illness is a Serious Employment and Income Risk

In summary, the analysis yields robust evidence in favour of the first hypothesis, indicating that both the onset and progression of chronic illness are negatively associated with employment and, consequently, earned income. These results corroborate recent findings reported by Islam et al. (2024) for Norway, thereby extending their applicability to the German context. The corresponding income losses range from minor reductions in annual earnings points to a complete loss of earned income due to unemployment, withdrawal from the labour force, or receipt of a disability pension. As is typical for chronic diseases, these adverse income effects generally do not manifest immediately, but only in the longer course of illness, confirming the second hypothesis as well. In this respect, chronic disease acts first as a brake on career development. Evidence for such mechanisms is documented in the literature for contexts such as Finland and the United Kingdom, showing that individuals suffering a health shock are less frequently considered for promotion than their healthy counterparts and are more likely to reduce weekly working hours (Islam et al. 2024; Lenhart 2019; Vaalavuo 2021).

The type and severity of chronic illness prove decisive for the magnitude of effects: both women and men experience considerably stronger negative effects on income when an indicator for severe chronic illnesses is used in the analysis rather than one encompassing all chronic conditions. The results therefore also confirm the fourth hypothesis. One explanation for the negative impact of the onset and progression of a chronic disease on average earnings points is that chronically ill people have a higher risk of becoming unemployed, working in marginal employment or drawing a partial or full disability pension in the aftermath of the diagnosis. This was confirmed in the descriptive analysis. In this reading, the chronic disease is thus to be seen as a “career killer”. Beyond these changes in employment status, the results, however, also point to adjustments in existing employment relationships. Compensation strategies commonly adopted include reducing weekly working hours or transitioning to a less demanding, albeit typically lower-paid, position (Flüter-Hoffmann et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2020; Vaalavuo 2021). While the income losses resulting from such adaptations tend to be less severe than those associated with complete withdrawal from employment, they nevertheless exert a significant impact on the total earnings points accumulated by an individual and on the level of their eventual old-age pension.

On the other hand, a large proportion of those affected had no income losses, at least in the first 10 years after diagnosis. Instead, the number of average earnings points remains at the pre-diagnosis level or even continues to rise. For these groups the consequences of the chronic disease are limited and vary between “career brake” and “business as usual”.

Last, the income and employment history of highly qualified persons is significantly less affected by the occurrence of a chronic disease than is the case with persons with low and medium qualifications. On the contrary: The fixed-effects regression clearly showed that the earnings points of the highly qualified develop positively even after the onset of the chronic disease. This positive income trend among highly skilled workers is also evident in the study by Islam et al. (2024), which shows that a high level of education seems to “shield” against negative labour market consequences:

To sum up, our results point in the direction that the highly educated chronically ill are more ‘shielded’ both in relative and absolute terms against unfortunate consequences of their illness compared to the other two groups. (Islam et al. 2024, 10)

An exception, however, is observed for men with severe chronic illnesses when alternative social statuses such as unemployment or disability pension are considered. In these cases, the compensatory effect associated with higher qualifications is substantially reduced and does not reach statistical significance. This finding suggests that withdrawal from the labour market – potentially at an early stage – and the resulting change in social status may constitute a relevant coping strategy even for highly qualified men affected by severe chronic illness. No analogous effect has been identified among women. As a side note: The adverse effects of a health shock on the progression of earnings points are substantially reduced and lose statistical significance for both women and men when alternative social status is controlled for. Accordingly, health shocks may be considered critical turning points for the career trajectories of both genders.

It should be noted that, as a consequence of the contribution assessment ceiling for social insurance in Germany, income losses occurring exclusively above this threshold for highly qualified individuals may not be captured in the results. This constitutes a methodological shortcoming, and it is important to be aware of the potential for slightly biased estimations as a result. On the other hand, the strong and significant effects observed among highly qualified individuals with chronic illness indicate meaningful variation in earnings points below the contribution assessment ceiling. Consequently, estimates for individuals with incomes up to this threshold can be regarded as robust. In sum, the analysis provides clear evidence for the validity of hypothesis 3 assuming that a chronic disease does not weaken existing income inequalities between socio-economic groups, but tends to increase them. In this sense, a chronic disease can be characterised as an amplifier of social inequality on the labour market.

Overall, the analysis indicates that chronic illness constitutes a significant risk to both employment and income, particularly among individuals with low to medium levels of educational qualification. In addition to the adverse effects on current employment and future pension entitlements, the associated income losses reduce contributions to the statutory pension system while simultaneously increasing expenditures for social security programs, such as higher rates of disability pension or unemployment benefit claims. Moreover, the objective of extending working life is undermined by the early labor market exit of individuals with chronic illnesses.

Mitigating these risks requires a targeted focus on the working conditions of affected individuals. Relevant workplace adaptations may include height-adjustable desks for those with musculoskeletal disorders or technical aids such as speech recognition software for employees with impaired vision. Additional measures – such as enhancing spatial and temporal flexibility, adjusting daily working hours, modifying weekly/monthly schedules, or enabling remote work – may further support sustained participation, predominately among office workers and those in larger firms.

By contrast, preventive strategies and the promotion of health literacy are especially important for chronically ill semi-skilled and unskilled workers as well as for workers in small companies, for whom workplace adaptations are less feasible. However, the responsibility for fostering health-promoting behaviours cannot rest with employers alone; active engagement of affected individuals is essential. Policy should therefore prioritise raising awareness and educational efforts regarding healthy behaviours, for example, through targeted workplace information sessions or statutory health insurance initiatives, and when possible, incorporating these themes into early education at schools.

Funding source: Forschungsnetzwerk Alterssicherung (FNA); Research Network on Pensions

Funding source: Deutsche Rentenversicherung

Effects of health changes on earning points; all chronic illnesses (chronic 1).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Chronic disease | −0.050** | −0.085*** | −0.056*** | −0.107*** | −0.032** | −0.066*** |

| Health shock | −0.125*** | −0.124*** | −0.118*** | −0.110*** | −0.004 | −0.013 |

| Age (mean centred) | 0.002*** | 0.015*** | 0.000 | 0.010*** | 0.000 | 0.009*** |

| Age (mean centred) × chronic disease | −0.007*** | −0.017*** | −0.008*** | −0.012*** | 0.000 | −0.002 |

| Chronic illness × high qualification | 0.196*** | 0.357*** | 0.187*** | 0.354*** | 0.091*** | 0.178*** |

| 2nd chronic illness | −0.011 | −0.056 | −0.016 | 0.060 | 0.019 | −0.006 |

| Duration of the chronic illness | 0.002 | 0.007* | 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Duration of health shock | 0.001 | −0.008* | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| Married | 0.174*** | 0.260*** | 0.041*** | 0.082*** | ||

| Children | −0.008 | 0.161*** | −0.066*** | 0.051*** | ||

| Married × children | −0.098*** | −0.042*** | ||||

| Divorced | 0.253*** | 0.181*** | 0.075*** | 0.038 | ||

| Partner’s earnings points | −0.003*** | 0.004** | −0.000 | 0.003** | ||

| Job change | 0.023** | 0.026** | ||||

| Full-time employment | 0.126*** | 0.132*** | ||||

| Part-time employment | −0.090*** | −0.123* | ||||

| School | −0.760*** | −0.954*** | ||||

| Vocational training | −0.451*** | −0.612*** | ||||

| Other status | −0.459*** | −0.457*** | ||||

| Periods of illness | −0.354*** | −0.397*** | ||||

| Unemployment | −0.377*** | −0.556*** | ||||

| No information | −0.658*** | −0.869*** | ||||

| Marginal employment | −0.641*** | −0.988*** | ||||

| Family work | −0.250*** | −0.472*** | ||||

| Employment | Reference | |||||

| Disability pension | −0.676 | −1.009*** | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Specifications | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 |

| Cases | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 |

| R 2 (within) | 0.076 | 0.25 | 0.093 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; separate calculations for women and men; Men: at least 15 years of insured employment; Women: at least 10 years of insured employment; Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Effects of health changes on earning points; more severe chronic illnesses (chronic 2).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Chronic disease | −0.083** | −0.081* | −0.089*** | −0.105** | −0.058*** | −0.041 |

| Health shock | −0.125*** | −0.145*** | −0.119** | −0.128** | −0.004 | −0.020 |

| Age (mean centred) | 0.001*** | 0.015*** | 0.001 | 0.010*** | 0.001 | 0.009*** |

| Age (mean centred) × chronic disease | −0.007** | −0.019*** | −0.008** | −0.013** | −0.001 | −0.003 |

| Chronic illness × high qualification | 0.255*** | 0.238*** | 0.249*** | 0.250** | 0.133*** | 0.077 |

| 2nd chronic illness | −0.012 | −0.028 | −0.016 | −0.033 | 0.036 | −0.010 |

| Duration of the chronic illness | 0.003 | 0.008* | 0.004 | 0.005 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Duration of health shock | 0.001 | −0.008* | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.001 | −0.000 |

| Married | 0.177*** | 0.262*** | 0.042*** | 0.081*** | ||

| Children | −0.005 | 0.164*** | −0.066*** | 0.051*** | ||

| Married × children | / | −0.099*** | / | −0.043*** | / | |

| Divorced | 0.256*** | 0.182*** | 0.076*** | 0.037 | ||

| Partner’s earnings points | −0.003*** | 0.004** | −0.000 | 0.003** | ||

| Job change | 0.023** | 0.027* | ||||

| Full-time employment | 0.126*** | 0.133*** | ||||

| Part-time employment | −0.090*** | −0.126* | ||||

| School | −0.760*** | −0.962*** | ||||

| Vocational training | −0.451*** | −0.610*** | ||||

| Other status | −0.458*** | −0.456*** | ||||

| Periods of illness | −0.354*** | −0.396*** | ||||

| Unemployment | −0.376*** | −0.557*** | ||||

| No information | −0.658*** | −0.870*** | ||||

| Marginal employment | −0.641*** | −0.988*** | ||||

| Family work | −0.250*** | −0.470*** | ||||

| Employment | Reference | |||||

| Disability pension | −0.674 | −1.012*** | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Specifications | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 | 78,266 | 75,322 |

| Cases | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1,684 | 1,764 | 1.692 |

| R 2 (within) | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.66 |

-

Source: Own calculations based on SHARE-RV Version 7.10; data from 2018; separate calculations for women and men; Men: at least 15 years of insured employment; Women: at least 10 years of insured employment; Significance levels: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

References

Andersen, Lars L., Per H. Jensen, and Emil Sandsturm. 2020. “Barriers and Opportunities for Prolonging Working Life Across Different Occupational Groups: The SeniorWorkingLife Study.” The European Journal of Public Health 30 (2): 241–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz146.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartel, Susanne. 2018. “Exit from Work. Gesundheitsbedingte Ausstiegs- und Neuorientierungsprozesse im Erwerbsleben.” PhD diss. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.Suche in Google Scholar

Blundell, R., J. Britton, M. Costa-Dias, and E. French. 2023. “The Impact of Health on Labor Supply Near Retirement.” The Journal of Human Resources 58 (1). https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.58.3.1217-9240R4.Suche in Google Scholar

De Boer, Angela, Goedele Geuskens, Ute Bültmann, Cecile Boot, Haije Wind, Lando Koppes, et al.. 2018. “Employment Status Transitions in Employees with and Without Chronic Disease in The Netherlands.” International Journal of Public Health 63 (6): 713–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1120-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Deming, Sarah M. 2022. “Beyond Measurement of the Motherhood Penalty: How Social Locations Shape Mothers’ Work Decisions and Stratify Outcomes.” Sociology Compass 16 (6): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1120-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Dettmann, Marieke-Marie, and Hans Martin Hasselhorn. 2020. “Stay at Work – Erhalt von und Wunsch nach betrieblichen Maßnahmen beim älteren Beschäftigten mit gesundheitlichen Einschränkungen in Deutschland.” Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz und Ergonomie 70: 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40664-019-00378-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Dragano, Nico, Morten Wahrendorf, Kathrin Müller, and Thorsten Lunau. 2016. „Arbeit und gesundheitliche Ungleichheit: Die ungleiche Verteilung von Arbeitsbelastungen in Deutschland und Europa.” Bundesgesundheitsblatt 59 (2): 217–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-015-2281-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Ferraro, Kenneth F., Markus H. Schafer, and Lindsay R. Wilkinson. 2016. “Childhood Disadvantage and Health Problems in Middle and Later Life: Early Imprints on Physical Health?” American Sociological Revue 81 (1): 107–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415619617.Suche in Google Scholar

Flüter-Hoffmann, Christiane, Oliver Stettes, and Patricia Traub. 2017. “Motiviert und produktiv trotz schwerer Krankheit: Rehadat-Studie „Mit Multipler Sklerose im Job“.” IW-Report 25. Cologne. https://www.iwkoeln.de/fileadmin/publikationen/2017/360177/IW-Report_2017_25_Rehadat_Studie_Multiple_Sklerose.pdf (accessed October 16, 2025)Suche in Google Scholar

Garcia-Gómez, Pilar, Hans van Kippersluis, Owen O’Donnell, and Eddy van Doorslaer. 2013. “Long-Term and Spillover Effects of Health Shocks on Employment and Income.” The Journal of Human Resources 48 (4): 873–909. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2013.0031.Suche in Google Scholar

Giesselmann, Marco, and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. 2022. “Interactions in Fixed Effects Regression Models.” Sociological Methods & Research 51 (3): 1100–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124120914934.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldman, Dana P, and James P. Smith. 2002. “Can Patient Self-Management Help Explain the SES Health Gradient?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (16): 10929–34, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.162086599.Suche in Google Scholar

Hagen, Christine, and Ralf K. Himmelreicher. 2020. “Erwerbsminderungsrente der erwerbsfähigen Bevölkerung in Deutschland – ein unterschätztes Risiko?” In Fehlzeiten Report 2020. Gerechtigkeit und Gesundheit, edited by B. Badura, A. Ducki, and H. Schröder, 729–40. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-662-61524-9_29Suche in Google Scholar

Hagen, Christine, Ralf K. Himmelreicher, Daniel Kemptner, and Thomas Lampert. 2017. “Soziale Ungleichheit und Risiken der Erwerbsminderung.” WSI-Mitteilungen 7/2011: 336–44. https://doi.org/10.5771/0342-300x-2011-7-336.Suche in Google Scholar

Hasselhorn, Hans Martin, and Angela Rauch. 2013. “Perspektiven von Arbeit, Alter, Gesundheit und Erwerbsteilhabe in Deutschland.” Bundesgesundheitsblatt 56: 339–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1614-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Hofäcker, Dirk, H. Heike Schröder, Yuxin Li, and Matthew Flynn. 2016. “Trends and Determinants of Work-Retirement Transitions Under Changing Institutional Conditions: Germany, England and Japan Compared.” Journal of Social Policy 45 (1): 39–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941500046X.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, Rasmus, Hannes Kröger, and Siegfried Geyer. 2019. “Social Causation Versus Health Selection in the Life Course: Does their Relative Importance Differ by Dimension of SES?” Social Indicators Research 141: 1314–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1871-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoven, Hanno, Morten Wahrendorf, Marcel Goldberg, Marie Zins, and Johannes Siegrist. 2020. “Cumulative Disadvantage During Employment Careers – The Link Between Employment Histories and Stressful Working Conditions.” Advances in Life Course Research 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100358.Suche in Google Scholar

Iacus, Stefano M., Gary King, and Giuseppe Porro. 2011. “Causal Inference Without Balance Checking: Coarsened Exact Matching.” Political Analysis 20 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr013.Suche in Google Scholar

Islam, M. Kamrul, Egil Kjerstad, and Havard Thorsen Rydland. 2024. “The Chronically Ill in the Labour Market – Are they Hierarchically Sorted by Education?” International Journal for Equity in Health 23 (66): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02148-w.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Andrew M., Nigel Rice, and Francesca Zantomio. 2020. “Acute Health Shocks and Labour Market Outcomes: Evidence from the Post Crash Era.” Economics and Human Biology 36: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100811.Suche in Google Scholar

Kröger, Hannes, Eduwin Pakpahan, and Rasmus Hoffmann. 2015. “What Causes Health Inequality? A Systematic Review on the Relative Importance of Social Causation and Health Selection.” European Journal of Public Health 25 (6): 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx238.Suche in Google Scholar

Laaksonen, Mikko, and Jenni Blomgren. 2020. “The Level and Development of Unemployment Before Disability Retirement: A Retrospective Study of Finnish Disability Retirees and their Controls.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (5): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051756.Suche in Google Scholar

Leijten, Fenna R. M., Astrid de Wind, Swenne van den Heuvel, Jan Fekke Ybema, Allard J. van der Beek, Suzan J. W. Robroek, et al.. 2015. “The Influence of Chronic Health Problems and Work-Related Factors on Loss of Paid Employment Among Older Workers.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 69: 1058–65. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-205719.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenhart, Otto. 2019. “The Effects of Health Shocks on Labour Market Outcomes.” The European Journal of Health Economics 20: 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0985-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Lundborg, Petter, Martin Nilsson, and Johan Vikström. 2015. “Heterogeneity in the Impact of Health Shocks on Labour Outcomes: Evidence from Swedish Workers.” Oxford Economic Papers 67 (3): 715–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpv034.Suche in Google Scholar

Mehnert, Anja. 2011. “Employment and Work-Related Issues in Cancer Survivors.” Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 77 (2): 109–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Mika, Tatjana, and Christin Czaplicki. 2010. Share-RV: Eine Datengrundlage für Analyse zu Alterssicherung, Gesundheit und Familie auf der Basis des Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe und der Daten der Deutschen Rentenversicherung. RV aktuell 12/2010: 396-400. https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Zeitschriften/RVaktuell/2010/Artikel/heft_12_mika_czaplicki.html (accessed October 16, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Nutbeam, Don, and Jane E. Lloyd. 2021. “Understanding and Responding to Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health.” Annual Reviews 42: 159–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529.Suche in Google Scholar

OECD/EU. 2016. Health at a Glance: Europe 2016 – State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Oude-Hengel, Karen, Suzan Robroek, Iris Eekhout, Allard J. van der Beek, and Alex Burdorf. 2019. “Educational Inequalities in the Impact of Chronic Diseases on Exit from Paid Employment Among Older Workers: A 7-Year Prospective Study in The Netherlands.” Occupational Environmental Medicine 76 (10): 718–25. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2019-105788.Suche in Google Scholar