Abstract

Prevention of juvenile sex trading in the US has risen to prominence in public policy discourse. We develop a generalized benefit-cost model to shed light on this policy issue and illustrate the framework with a case study from Minnesota. The model treats government-funded intervention as an investment project and calculates its net present value. Benefits are derived from harms avoided by reducing the extent of sex trading. The impacts of youth involvement in the market for sexual services are highly complex, and clear data on them are lacking. To account for empirical ambiguity we develop the model around a representative individual, approximate the effect of intervention on the sex market, and conduct sensitivity analysis with key model parameters. The case study evaluates seventeen distinct harms caused by sex trading based on conservative best estimates from scholarly literature. We find a large positive Net Present Value, suggesting it is in the best interest of Minnesota taxpayers to support intervention.

- 1

Also sometimes referred to as child sex trafficking, child prostitution, commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC), and more.

- 2

See President Obama’s speech at the Clinton Global Summit, September 25, 2012, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/09/25/remarks-president-clinton-global-initiative; According to the Polaris Project, thirty-nine states passed new laws on human trafficking in 2013, http://www.polarisproject.org/what-we-do/policy-advocacy/national-policy/state-ratings-on-human-trafficking-laws; The Federal Bureau of Investigations supports the development of taskforces to address child prostitution and trafficking, http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/vc_majorthefts/cac/innocencelost.

- 3

- 4

See for example, Shared Hope, http://sharedhope.org/learn/faqs/, estimate of at least 100,000 children; National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, http://www.missingkids.com/home; the Polaris Project, http://www.polarisproject.org/about-us/overview.

- 5

See Polaris Project website for a list of States and a description of the policy context, http://www.polarisproject.org/what-we-do/policy-advocacy/assisting-victims/safe-harbor.

- 6

It is important to be clear what “successful” means in this context. By program success we mean a potential sex trader is dissuaded from trading sex. But if she is replaced by another individual, total sex trading would not be diminished. By policy success we mean program success coupled with no, or perhaps partial, replacement. It is this latter sense that we intend here. This issue of replacement is treated fully in Section 3.

- 7

See Weitzer, 2009.

- 8

While there are connections between our narrow conception of sex trading and the broader range of sex markets, there are also critical distinctions relating to legality and the nature of social harms that the activities may inflict. In our view the distinctions are paramount and justify treating the different market segments with distinct analytical frameworks. Moreover, recent policy concerns in this area are predominantly directed toward the activities we engage rather than this broader range.

- 9

See Minnesota State Legislature, Special Session 1, 2011; SF0001, 2011 and HF0001, 2011.

- 10

See the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, Hubert Project eCase, “Ending Child Sex Trafficking in Minnesota and US, http://www.hubertproject.org/hubert-material/238/.

- 11

The program is the Runaway Intervention Project (RIP) currently operating in Ramsey County, Minnesota. Our case study relies on the program’s budget to support the “cost” side of our benefit-cost model as well as published evaluation to ground our assumption on program effectiveness. Although the majority of RIP clients have not already been involved in such sexual activities, approximately 10% of the clients come to the program after some history of sex trading or other sexual exploitation.

- 12

These several personal benefits from choosing not to engage in sex trading may also create substantial indirect benefit for the families of the dissuaded potential sex-trader. In some cases the youth are at risk for entering sex trading precisely because of a troubled family situation, so this indirect psychic benefit may not be relevant in all cases. But even in the context of a dysfunctional family setting there is potential for sympathy and concern.

- 13

Some studies take as a basic assumption that all involvement in commercial sex markets on the part of all sellers is not voluntary (see Farley, 2004). Others suggest that suppliers of sexual services in some market segments engage in the market by choice (see Weitzer, 2009).

- 14

See for example, Monto and Milrod, 2014.

- 15

Zerbe and Bellas define standing as: “The right to have one’s values counted in a benefit-cost analysis.” (2006, p. 8)

- 16

Sex trading is a criminal offense in all of the US, with the exception of certain counties in Nevada. In the Model Penal Code, a template on which many state criminal laws are based, most all activities related to commercial sex are identified as criminal offenses (American Law Institute, 1962).

- 17

In this context we maintain that a binary approach to standing is appropriate. Individuals have it, or they do not. This is often adopted in benefit-cost studies. But in a broader scope, say one that includes punishment of criminals, a more nuanced treatment of standing may be required. This must be tied to broader social concerns for justice in which even convicted criminals may have some rights guaranteed by law. The eighth amendment to the US Constitution provides an example. We are indebted to a reviewer for pointing out this nuance.

- 18

See Zelizer (2005) for an excellent analysis of intimacy in social interactions, including sexual relations.

- 19

Not only would this require estimates of likelihood of client infection, it would also require knowledge of clients’ sexual behavior in relation to the wider community and likelihood of infection there. This is extremely elusive information.

- 20

Although this negative effect on property value has an intuitive appeal and has been the basis zoning ordinances that restrict “adult” businesses, research by Paul, Linz, and Shafer (2001) strongly criticizes the scientific basis of this inference. “Those studies that are scientifically credible demonstrate either no negative secondary effects associated with adult businesses or a reversal of the presumed negative effect.” (p. 355)

- 21

It could be argued that there is no need to consider shelter costs because some kind of housing would be provided to homeless youth even without the intervention program. We include shelter costs that are paid by governmental agencies, because safe housing is a critical component to any effective intervention project. Given some ambiguity on this point, we find it prudent to include shelter costs in calculation of NPV for the intervention program. Results reported for the case study in Section 5 are presented both with and without shelter costs, but emphasis is on results that include these costs.

- 22

Several studies evaluate the share of homeless female adolescents engaged in sex trading, with estimates ranging from 10% to 50% (Greene et al., 1999). We recognize that an adolescent female need not be homeless to have significant potential to enter sex trading. But estimates of sex trading potential in the empirical literature seem to be limited to homeless adolescents. Any application of our framework needs to define its own YP and assess its characteristics. It need not be restricted to adolescents or females, but that is the focus of our case study in Section 5.

- 23

It is, of course, possible that some adolescents with sex trading potential who are referred to the intervention program do not become clients. But our analysis need not address this because these individuals would neither impose costs nor return any benefit. Analytically, we can treat them as outside YP.

- 24

By “earnings” we mean payments for sexual services. These may accrue to the sex trader, or they may be captured in part or even completely by a market facilitator. The non-replacement coefficient is a feature of the market largely independent of this interesting distributional question.

- 25

There are intuitive reasons to suppose this supply is relatively inelastic: social circumstances of female youth are not easily altered in a way that would induce them toward sex trading, natural population growth is slow, and inward migration may be difficult to accomplish due to both cultural and legal institutions related to youthful female populations. But ultimately this is an empirical matter and elasticities will depend on particular characteristics of the venue in which the supply reduction occurs. Is it urban or rural? Are there ethnic distinctions? Are sex traffickers extensively involved, or not? We thank a reviewer for pointing out these connections with the non-replacement coefficient, but we leave this interesting empirical issue for future research and rely on sensitivity analysis to address it in our model application.

- 26

Although best modeling practice would use population averages of the harms experienced by a representative individual, data limitations force us to use non-representative sample means to approximate this average.

- 27

The extent of harm may be be dependent on time through changes in behavior. If females learn through experience to avoid some of the harms, the time profile would fall. On the other hand, physical injury and psychological stress may cause some women to lose ability to avoid some of the harms due to cognitive impairment (caused by factors such as drug use and traumatic brain injury) and worsening economic situation. In this case Hjt may well rise through time for certain types of harm. Our model does not attempt to account for such changes.

- 28

There is no clear and definitive scholarly evidence of an average age of first sex trade. The research literature shows a wide range of age of first sex trade for juveniles, ranging from very young to age 17. Many studies find an average age of first sex trade for juveniles between 13 and 14 years old (see Martin et al., 2010). We did not want to overestimate the degree of cumulative harm in early adolescence, therefore for our model we selected age 14 as the onset of sex trading in line with our conservative approach. Further, we believe the early intervention and prevention program will likely focus on girls around this age.

- 29

This dependence of the time profile of harms on sex trading trajectories also suggests it may be important to compare the potential trajectory of a dissuaded sex trader against one followed by a potential market replacement. Significant and persistent differences between the two groups would have implications for analysis of harms avoided, i.e., benefits in our framework. Because we have no empirical information on these differences, we have chosen not to attempt to bring this matter under review. We leave it for future research and thank an anonymous reviewer for raising the issue.

- 30

Estimates of VSL have a large variability from study to study and even within the same study. Aldy and Viscusi (2008) provide eight different estimates, each based on a different year of data. These range from $0.95 to $6.45 (millions of 2000 dollars). The simple average of the estimates is $4.68 million ($5.98 million in 2011 dollars). Thus the VSL value we use to estimate the benefit of avoided homicide is in the low range.

- 31

Potterat et al. calculate a crude mortality rate for homicide during active sex trading at 229 per 100,000 person-years, and they also report a standardized mortality ratio for this cohort at 17.7. We used the ratio to adjust the mortality rate downward to 216 as a way to account for the probability of homicide in the general population. Thus the figure 216 per 100,000 represents the increased risk attributable to active sex trading.

- 32

One exception to this avoided expenditure approach to benefits is the increase in income tax revenue that would accrue when sex trading is prevented.

- 33

Public service organizations like this often rely on community volunteers and NGOs as resources to supplement government funding. While we recognize such contributions to cost, our perception is that they are relatively minor for youth intervention programs like RIP and we do not incorporate them into our cost estimate.

- 34

In addition to published sources we rely on personal communications with the following program staff: Laurel Edinburgh, Midwest Children’s Resource Center, Children’s Hospital, nurse practitioner and researcher with the Runway Intervention Project; Elizabeth Saewyc, program evaluator for RIP, University of British Columbia School of Nursing and Division of Adolescent Medicine, Vancouver, Canada; and Kathryn Richtman, Ramsey County Attorney’s Office. RIP documents provided on December 9, 2011.

- 35

Personal communication, evaluator Dr. Elizabeth Saewyc, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, April 6, 2012.

- 36

The precise concern of our research is sex trading, which is not exactly the same as sexual exploitation. Exploitation may involve rape, in which no trade occurs. More controversially, sex trading may or may not be exploitative, depending on circumstantial details and one’s ethical outlook on the exercise of free will among sex traders. The researcher who provided this effectiveness estimate treats sexual exploitation as analogous to sex trading (Saewyc, MacKay, Anderson, & Drozda 2008, p. 13). For our purposes we feel a precise distinction is not necessary because the point here is to get a quantitative estimate of the effectiveness of an intervention program to change sexual behaviors. Moreover, we conduct extensive sensitivity analysis on the basis of this parameter, which we believe is adequate consideration of conceptual distinctions between sex trading and sexual exploitation.

- 37

There are no specific characteristics required for members of the target population in order to qualify for assistance. The legislation focused on female adolescents living under socio-economic disadvantage, which may have a variety of causes, including homelessness and status as a runaway child.

- 38

Personal communication, Kathryn Richtman, Ramsey County Attorney, personal communication, Dec. 12, 2011.

- 39

Data from Beth Holger-Ambrose, Homeless Youth Services Coordinator, Minnesota Department of Human Services, personal communication, February 14 and 15, 2012. Figures are for 2011.

- 40

This expense was not included in our original report for MIWRC. We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this omission to our attention. Inclusion of this cost for intervention reduces NPV results somewhat, but it does not alter our basic conclusions.

- 41

IRS Data Book, Table 5. Accessed on 29 December 2013.http://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Gross-Collections,-by-Type-of-Tax-and-State,-Fiscal-Year-IRS-Data-Book-Table-5

- 42

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the lack of this particular harm in our original model. The probabilities used are the same as in the illustration of mortality risk in Section 2 above. For unit cost we relied on the professional opinions of retired police detectives to drive a rough estimate of $10,000. They cautioned us that the cost of a homicide investigation can vary widely. If we increase this unit cost to $40,000, it increases the aggregate benefit by only about 0.3%. Thus our conclusions are not very sensitive to this particular unit cost, which can be understood to also cover any public expense for burial or cremation.

- 43

We exclude consideration of sales tax revenue because a youth would pay roughly equivalent amounts whether she earned income from sex trading or legitimate employment. But only in the latter case would government collect income tax from her.

- 44

With the exception of homicide investigation, specific figures contained in Table 3 and used in our calculations were derived from a broad range of empirical literature, which is too extensive to review in the present paper. Interested readers are directed to our full report for complete information behind all the numbers. Available at: http://www.miwrc.org/about-us-section-benefit-cost-study.

- 45

In our review of the epidemiological literature specific to sex trading, we were unable to find reliable statistical evidence relating to other STIs, such as gonorrhea and syphilis. We accept this as a flaw in our empirical application, which, if addressed, would strengthen our overall conclusion that an intervention program returns a positive NPV. In a similar vein, we have excluded transmission of all STIs to the broader community, an externality discussed above. While the rate of transmission between sex traders and clients might be reasonably identified, subsequent transmission depends on sexual behavior between clients and other members of the community. Our judgment is that the necessary quantitative information to include this externality as a harm is too fraught with uncertainty.

- 46

The last harm in this table, forgone income tax revenue, is sensitive to assumptions regarding educational attainment. The annual harm value of $1118 reflects an assumption that earnings in the absence of sex trading would be for a female population with no higher education and of which 89% complete high school. We have considered lower values for high school completion of 80% and 60%. These imply annual forgone income tax revenues of $1059 and $928, respectively. When aggregated to the present value of the stream of benefits, these alternative assumptions reduce the total by about 0.2% and 0.6%, which is trivial in relation to our overall results. Our conclusions are robust to alternative assumptions regarding educational attainment.

- 47

We recognize that the data supporting this assumed value that is used in the model is suggestive rather than definitive. HIV infection may arise from other behaviors such as drug use; however, we believe that the epidemiological evidence supports an inference that, to some extent, sex trading is a causal factor in the prevalence of HIV infection. We use the only observations we have to derive a workable assumption on the probability of becoming infected as a result of trading sex.

- 48

Sloan et al. report annual cost at 20,170 in constant 2010 euros (p. 54). We converted this to dollars using the average 2010 dollar/euro exchange rate (1.326 $/euro) and then inflated the converted figure to $2011 using the U.S. GDP deflator. The exchange rate was calculated from daily rates reported by the European Central Bank. Accessed on 29 May 2012 from: http://www.ecb.int/stats/exchange/eurofxref/html/index.en.html.

- 49

This annual cost of HIV/AIDS therapy is quite close to an estimate by Schackman et al. (2006) based on the U.S. health care system using 2004 data (Schackman et al., 2006). Using the same simulation model, their base case estimate of annual treatment cost is $25,574 in 2004 dollars. Adjusting to 2011 dollars results in a cost of $29,933. We choose to rely on Sloan et al. because their research is more recent and the cost estimate is somewhat lower, which is part of our attempt to be conservative in the assessment of benefits in our model.

- 50

Rationale for this explained on page 18.

- 51

Although we argue in Section 2 that clients lack standing, to the extent that they would access publically financed medical treatment this harm is still relevant for benefit calculation.

- 52

We are indebted to Samuel Lee for solving this analytical puzzle.

Acknowledgments

The Nathan Cummings Foundation provided financial support for this research through the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center (MIWRC). The authors are grateful for that support and wish to thank several individuals for contributions to this paper. Suzanne Koepplinger, Executive Director of MIWRC, was a sounding board and supporter of this project from the beginning. Lauren Stark and Jon Luke Robertson provided research assistance. Many individuals helped us identify harms and uncover critical cost data for the Minnesota case study. These include: Julie Rud, Kathryn Ritchman, Laurel Edinburgh, Elizabeth Saewyc, Beth Holger-Ambrose, Sarah Gordon, Candy Hadsall, Artika Roller, and Nancy Dunlap. Debra Israel, Mark Cohen and Alexandra (Sandi) Pierce provided commentary on early drafts and made useful suggestions to extend the analysis in particular directions. Robert Guell provided expert advice on some computational issues, DeVere Woods advised us on criminal justice aspects, and Larry Gant checked our treatment of HIV/AIDS issues and guided us to the most recent empirical literature on costs and survival. Sam Lee provided an elegant solution to a particular analytical puzzle. We also benefited from comments by student and faculty participants in Indiana State University’s Social Science Research Colloquium and the Brown Bag Seminar series of ISU’s Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Through careful reading and commentary the editor and reviewers for the Journal of Benefit Cost Analysis provided very useful critical advice. Any errors remain the responsibility of the authors.

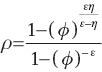

Appendix A: Analysis52 to derive non-replacement coefficient, ρ

The non-replacement coefficient represents the proportion of dissuaded sex traders (potential or actual) who are not replaced by new market entrants in response to an increase in earnings. This appendix explains the calculation of coefficient values in Table 2. To follow the derivation intuitively, readers could refer to Figure 1 in the text, which shows a stable demand curve (D) and two equilibria that result from an original supply curve (S1 with equilibrium e1) and a supply curve shifted leftward (S2 with equilibrium e2).

We use iso-elastic demand and supply relations with the following specifications. Demand:

Use this in the supply relation to find W*:

Consider two values of k, k1 for status quo, and k2 reflecting the impact of the intervention program on the supply of sex traders. Accordingly, we define the following equilibrium values:

Define

The non-replacement coefficient is defined as:

Substitute for

Define a supply shift parameter, φ, using k2=φk1 and substitute into the previous expression, which, with simplification, yields

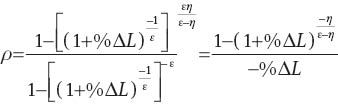

The shift parameter depends primarily on the extent of leftward shift of supply, but it is also sensitive to the supply elasticity. Since we cannot know precisely how much intervention will shift supply leftward, we investigate calculations of ρ for three different shifts defined as percentages from an arbitrary value of L1: 1%, 10% and 20%. To find the shift parameter, define the percent change in L at a constant wage as:

Substituting the expression for

Table A1 shows values of the non-replacement coefficient for three different assumptions for each elasticity and three different supply shifts. Without knowing the size of the market, we cannot know the percentage reduction of sex traders that an intervention would cause. Although this parameter is relatively insensitive to the extent of supply shift, it does increase with the shift extent. Thus a more conservative claim for intervention benefits would be based on a smaller supply shift. For the purpose of the case study we assume a 1% shift.

Values of ρ under different elasticity assumptions.

| Supply elasticity | Demand elasticity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| –0.5 | –1 | –2 | |

| 1% Reduction | |||

| 0.2 | 0.715 | 0.834 | 0.910 |

| 0.5 | 0.501 | 0.668 | 0.801 |

| 1 | 0.334 | 0.501 | 0.668 |

| 10% Reduction | |||

| 0.2 | 0.725 | 0.841 | 0.913 |

| 0.5 | 0.513 | 0.678 | 0.808 |

| 1 | 0.345 | 0.513 | 0.678 |

| 20% Reduction | |||

| 0.2 | 0.737 | 0.848 | 0.918 |

| 0.5 | 0.528 | 0.691 | 0.817 |

| 1 | 0.358 | 0.528 | 0.691 |

Appendix B: Comparison of model results with the original application

An earlier version of our framework supported policy discussion in Minnesota. Based on constructive critical remarks from conference participants and reviewers of this journal, we have since refined the model and adjusted its empirical content. The results are presented above in Section 5. Results from the original application of our framework can be found in the report released in 2012, which is available on-line here: http://www.miwrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Benefit-Cost-Study-Full.pdf.

This appendix explains specific changes made in refining the model and reviews how those changes affected results of the calculations. In general the refinements had minor impacts, and our overall conclusion remains the same. From the perspective of Minnesota taxpayers, an intervention program like we analyze returns a positive net present value, making it a good public investment. Below we list the individual modifications with brief assessments of how these changes affected results in relation to the original model application.

Inclusion of an additional harm: public cost of homicide investigation. This increased the present value of benefits by a small amount, about 0.1%.

A more conservative supply shift assumption (1% rather than 10%). This affected the non-replacement coefficient (see appendix A), decreasing it from 0.81 to 0.801. This decreased the present value of benefits proportionately, by about 1.1%. Combining this change with the additional harm noted above resulted in a reduction of about 1% in the present value of benefits.

Increase in Minnesota share of shelter cost. Our original application excluded all the federal contribution to shelter cost, which is considerable. In the revised model we included the portion of that contribution that can be linked to Minnesota taxpayers (3%). The effect was to increase annual shelter cost per client from $903 to $1402. When combined with programming service cost, this change increased overall cost per client by 28%. This decreased all NPV calculations where shelter cost is included, but the extent depends on both the rate of discount and the program effectiveness coefficient (α). At maximum program effectiveness (α=1) the reduction in NPV per client is around 0.6%. For very low program effectiveness (α=0.1) the reduction of NPV is around 8%. These effects are nearly the same for all three discount rates.

Broader sensitivity analysis with respect to the discount rate. In the original model application we used only three discount rates: the central rate derived from review of Minnesota general obligation bonds and rates higher and lower than this by 1 percentage point. The results presented in Section 5 include NPV figures calculated with 5% and 7% rates of discount as well. Given the model structure, higher discount rates will decrease the NPV, as can be seen in Tables 4 and 5, but the effects are relatively modest since the time profiles of most benefits is rather short.

References

Aldy, J. E., & Viscusi, W. K. (2008). Adjusting the value of a statistical life for age and cohort effects. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 573–581.10.1162/rest.90.3.573Suche in Google Scholar

American Law Institute. (1962). Model penal code. Philadelphia, Pa.: The Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Brewer, D. D., Dudek, J. A., Potterat, J. J., Muth, S. Q., 4 B. A.; Roberts, J. M., … Woodhouse, D. E. (2006). Extent, trends, and perpetrators of prostitution-related homicide in the United States. Journal of Forensic Science, 51(5), 1101–1108.10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00206.xSuche in Google Scholar

Curtis, R., Terry, K., Dank, M., Dombrowski, K., & Khan, B. (2008). The commercial sexual exploitation of children in New York city: the CSEC population in New York City: size, characteristics, and needs. (1). New York, New York: Center for Court Innovation.Suche in Google Scholar

Dalla, R. L. (2006). “You can’t hustle all your life”: an exploratory investigation of the exit process among street-level prostituted women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(3), 276–290.10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00296.xSuche in Google Scholar

DeRiviere, L. (2006). A human capital methodology for estimating the lifelong personal costs of young women leaving the sex trade. Feminist Economics, 12(3), 367–402.10.1080/13545700600670434Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards, J. M., Iritani, B. J., & Hallfors, D. D. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among adolescents in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(5), 354–358.10.1136/sti.2006.020693Suche in Google Scholar

Farley, M. (2004). Bad for the body, bad for the heart: prostitution harms women even if legalized or decriminalized. Violence Against Women, 10, 1087–1125.10.1177/1077801204268607Suche in Google Scholar

Farmer, A., & Horowitz, A. W. (2013). Prostitutes, pimps, and brothels: intermediaries, information and market structure in prostitution markets. Southern Economic Journal, 79(3), 513–528.10.4284/0038-4038-2011.153Suche in Google Scholar

Graham, N., & Wish, E. (1994). Drug use among female arrestees: onset, patterns, and relationships to prostitution. Journal of Drug Issues, 24, 315–330.10.1177/002204269402400207Suche in Google Scholar

Greene, J. M., Ennett, S. T., & Ringwalt, C. L. (1999). Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1406–1409.10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1406Suche in Google Scholar

Heckman, J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900–1902.Suche in Google Scholar

Kurtz, S. P., Surratt, H. L., Kiley, M. C., & Inciardi, J. A. (2005). Barriers to health and social services for street-based sex workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(2), 345–361.10.1353/hpu.2005.0038Suche in Google Scholar

Levitt, Steven, & Venkatesh, Sudhir. (2007). An empirical analysis of street-level prostitution. Working paper. Retrieved from http://economics.uchicago.edu/pdf/Prostitution%205.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, L., Hearst, M., & Widom, R. (2010). Meaningful differences: comparison of adult women who first traded sex as a juvenile versus as an adult. Journal of Violence Against Women, 16(11), 1252–1269.10.1177/1077801210386771Suche in Google Scholar

McClanahan, S. F., McClelland, G. M., Abram, K. M., & Teplin, L. A. (1999). Pathways into prostitution among female jail detainees and their implications for mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 50(12), 1606–1613.10.1176/ps.50.12.1606Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, C. L., Fielden, S. J., Tyndall, M. W., Zhang, R., Gibson, K., & Shannon, K. (2011). Individual and structural vulnerability among female youth who exchange sex for survival. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(1), 36–41.10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.003Suche in Google Scholar

Minnesota Department of Health. (2011). 2010 Minnesota sexually transmitted disease statistics. Retrieved from http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/dtopics/stds/stats/stdreport2010.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Monto, M., & Milrod, C. (2014). Ordinary or Peculiar Men? Comparing the customers of prostitutes with a nationally representative sample of men. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 58(7), 802–820.10.1177/0306624X13480487Suche in Google Scholar

O-Brien, James. (2013). The age-adjusted value of a statistical life: revealed preference evidence from automobile purchase decisions. Research paper presented at Annual Meetings of the Midwest Economics Association, Columbus, Ohio.Suche in Google Scholar

Paul, B., Linz, D. G., & Shafer, B. J. (2001). Government regulation of ‘adult’ businesses through zoning and anti-nudity ordinances: debunking the legal myth of negative secondary effects. Communication Law and Policy, 6, 355–392.10.1207/S15326926CLP0602_4Suche in Google Scholar

Persell, D. (2000). Sex worker assessment project: a HIV needs assessment of sex workers in the Twin Cities. Hennepin County Community Health Department, Red Door Clinic. Minneapolis.Suche in Google Scholar

Potterat, J. J., Brewer, D. D., Muth, S. Q., Rothenberg, R. B., Woodhouse, D. E., Muth, J. B., … Brody, S. (2004). Mortality in a long-term open cohort of prostitute women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(8), 778–785.10.1093/aje/kwh110Suche in Google Scholar

Potterat, J. J., Woodhouse, D. E., Muth, J. B., & Muth, S. Q. (1990). Estimating the prevalence and career longevity of prostitute women. The Journal of Sex Research, 27(2), 233–243.10.1080/00224499009551554Suche in Google Scholar

Saewyc, E. (2011). Ramsey county runaway intervention project, Annual Progress Report: 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

Saewyc, E. M., & Edinburgh, L. D. (2010). Restoring healthy developmental trajectories for sexually exploited young runaway girls: fostering protective factors and reducing risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(2), 180–188.10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.010Suche in Google Scholar

Saewyc, E., MacKay, L., Anderson, J., & Drozda, C. (2008). It’s not what you think: sexually exploitated youth in British Columbia (pp. 1–63). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia School of Nursing.Suche in Google Scholar

Saewyc, E. M., Taylor, D., Homma, Y., & Ogilvie, G. (2008). Trends in sexual health and risk behaviours among adolescent students in British Columbia. [Article]. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 17(1/2), 1–14.Suche in Google Scholar

Schackman, B., Gebo, K., Walensky, R., Losina, E., Muccio, T., Sax, P., … Freedberg, K. (2006). The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus cared in the United States. Medical Care, 44(11), 990–997.10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2aSuche in Google Scholar

Sloan, C. E., Champenois, K., Choisy, P., Losina, E., Walensky, R. P., Schackman, B. R., … Yazdanpanah, Y. (2012). Newer drugs and earlier treatment: impact on lifetime cost of care for HIV-infected adults. AIDS, 26(1), 45–56.10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dce6eSuche in Google Scholar

Sugden, R., & Williams, A. (1978). The principles of practical cost-benefit analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Surratt, H. L., Inciardi, J. A., Kurtz, S. P., & Kiley, M. C. (2004). Sex work and drug use in a subculture of violence. Crime and Delinquency, 50(1), 43–59.10.1177/0011128703258875Suche in Google Scholar

Tyler, K. (2009). Risk factors for trading sex among homeless young adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(2), 290–297.10.1007/s10508-007-9201-4Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. Department of State. (2013). Trafficking in Persons. Washington: U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/210742.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2001). Another decade of social scientific work on prostitution. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12, 242–289.Suche in Google Scholar

Weitzer, R. (2009). Sociology of sex work. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 213–234.10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120025Suche in Google Scholar

Willis, B. M., & Levy, B. S. (2002). Child prostitution: global health burden, research needs, and interventions. Lancet, 359(9315), 1417–1422.10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08355-1Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson, H. W., & Widom, C. S. (2010). The role of youth problem behaviors in the path from child abuse and neglect to prostitution: a prospective examination. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 210–236.10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00624.xSuche in Google Scholar

Zelizer, V. A. (2005). The purchase of intimacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Zerbe, R. O., & Bellas, A. S. (2006). A primer for benefit-cost analysis. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.Suche in Google Scholar

©2014 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the editors

- Letter from the Editors for the JBCA, Volume 5, Issue 1 (2014) June 17, 2014

- Articles

- Estimating the social value of higher education: willingness to pay for community and technical colleges

- A benefit-cost framework for early intervention to prevent sex trading

- Behavioral economics and policy evaluation

- Role of BCA in TIGER grant reviews: common errors and influence on the selection process

- Identifying the analytical implications of alternative regulatory philosophies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the editors

- Letter from the Editors for the JBCA, Volume 5, Issue 1 (2014) June 17, 2014

- Articles

- Estimating the social value of higher education: willingness to pay for community and technical colleges

- A benefit-cost framework for early intervention to prevent sex trading

- Behavioral economics and policy evaluation

- Role of BCA in TIGER grant reviews: common errors and influence on the selection process

- Identifying the analytical implications of alternative regulatory philosophies