Estimating the social value of higher education: willingness to pay for community and technical colleges

Abstract

Much is known about private financial returns to education in the form of higher earnings. Less is known about how much social value exceeds this private value. Associations between education and socially-desirable outcomes are strong, but disentangling the effect of education from other causal factors is challenging. The purpose of this paper is to estimate the social value of one form of higher education. We elicit willingness to pay for the Kentucky Community and Technical College System (KCTCS) directly and compare our estimate of total social value to our estimates of private value in the form of increased earnings. Our earnings estimates are based on two distinct data sets, one administrative and one from the U.S. Census. The difference between the total social value and the increase in earnings is our measure of the education externality and the private, non-market value combined. Our work differs from previous research by focusing on education at the community college level and by eliciting values directly through a stated-preferences survey in a way that yields a total value including any external benefits. Our preferred estimates indicate the social value of expanding the system exceeds private financial value by at least 25% with a best point estimate of nearly 90% and exceeds total private value by at least 15% with a best point estimate of nearly 60%.

- 1

Heckman, Lochner and Todd (2006) scrutinize this research based on the Mincer (1974) equation and estimate more general, nonparametric earnings models that allow for earnings to vary by year after completion (nonlinearity) and allow for the nonstationarity of earnings over time. Their analysis shows (1) assuming linearity leads to a downward bias to the return, (2) taking into account taxes has little impact on the return estimates, (3) taking into account tuition costs of schooling lowers the return to college by a few percentage points, and (4) psychic costs, in addition to money costs, can be a barrier to college education. Their work emphasizes that the private returns to education are substantial.

- 2

Wolfe and Haveman (2002) identify and describe intrafamily productivity, marital choice efficiency, health of children, crime reduction, charitable giving, and social cohesion as schooling outcomes that are part of nonmarket private returns and social returns.

- 3

See also Turner, Tamura, Mulholland and Baier (2007) and Yamarik (2008).

- 4

Two professionally moderated focus groups consisting of Kentuckians were conducted to ensure that respondents’ understanding and interpretation of the survey questions matched the intention of the survey authors. One group consisted of eight members of the Donovan Scholar Program, who are individuals over age 65 who were attending selected classes at the University of Kentucky. The second focus group consisted of eight returning students who were attending the Maysville Community and Technical College. Focus groups were recorded and the results were used to refine elements of the survey. The complete survey instrument is available on line at http://cber.uky.edu/pdf/CBER_UL_KCTCSReport_10-2007.pdf.

- 5

Knowledge Networks invited 370 members of its web panel to participate in the web-based sample. Two hundred and seventy-five responded yielding a response rate of 74%. The mail-based sample consisted of an initial mailing of 10,000 households. Eight hundred and four were undeliverable. A total of 2681 surveys were returned for a response rate of 29% (2681/9196). Not all 2956 web and mail observations are usable due to: a wording error on two versions of the survey (1486), protestors who did not vote for the referendum and indicated in a follow-up question “my household should not have to pay more taxes to fund the expansion” (261), and item nonresponse for variables in the logit regression (186). The number of remaining usable observations from the web (109) and mail (914) surveys is 1023.

- 6

Another indication, and one that might tell something about unobservable characteristics, is that when we control for whether an observation comes from the high response web survey or the lower response mail survey, the coefficient on the dummy variable for the web survey is not statistically different from zero. This result will be reported in Table 3 below for the logit analysis of the contingent valuation referendum responses.

- 7

Kling et al. (2012) assess the state of contingent valuation with emphasis on related research during the last 20 years. In addition to certainty statements, they report on successful avoidance of hypothetical bias by making the contingent valuation consequential. In other words, if respondents believe their responses will influence policy, then they report what they would really do. We do not include a consequentiality script. However, we do include the statement that responses will help administrators make decisions that reflect the views of the people of Kentucky in the second section of the survey instrument about budget choices, and we do ask for a vote in a referendum format.

- 8

For example, Blumenschein et al. (2008, Figure 2, p. 127) show a plot of price against percentage buyers for a field experiment in which a health management program was offered to individuals for real. Similar “demand curves” are shown for contingent valuation of the same good for both all “yes” responses and for calibrated “yes” responses. The calibration is that only “definitely sure yes” responses are classified as true “yes” responses. The demand curve for all “yes” responses is noticeably (and statistically) higher than the real demand curve. The hypothetical demand curve based on certainty-calibrated “yes” responses is virtually and statistically indistinguishable from the real demand curve. In other words, any hypothetical bias is not detectable after the calibration.

- 9

Iterative valuation techniques tend to offer more precise estimates of willingness to pay but the precision comes at a cost. The iterations alter the incentives of respondents to reveal their willingness to pay. In addition, the initial round of valuation in iterative settings may contain unintended information that consequently alters an individual’s valuation; see Whitehead (2002).

- 10

Epstein (2003) evaluates the case for using contingent valuation and notes that, in general, possible negative values should not be ignored. Although some households may place a low or zero value on higher education, there was no indication of negative values in the focus groups.

- 11

Two additional variables are used to control for version of the survey. Based on a split sample study design some respondents were presented with a referendum and tax amount to prevent either a 10 or 25% reduction in the KCTCS and were also given a “cheap talk” exhortation to avoid hypothetical bias; see Cummings and Taylor (1999). Because we focus on the 10% expansion and use the follow-up certainty questions to mitigate hypothetical bias and we want to control for any combined reduction, cheap talk effect, we include the two variables for reduction/exhortation. Because of a wording error on the survey we do not have parts of our sample that permit clean tests for the effects of cheap talk or reductions separately, but we control for their combined effects. See footnote 17 for a discussion of the implications for sample size.

- 12

The results reported above are based on the pooled sample that includes responses from the web and mail surveys. We stratified and estimated logits of the yes/no responses for the web and mail subsamples. Differences across the two are not significant at the 5% level.

- 13

In addition to asking about willingness to pay for expansion of the KCTCS, we asked respondents about perceived benefits they receive from education. We asked respondents to allocate points to the various benefit categories. Respondents were told that allocating more points to a given category indicated that they believed education provided more benefit in the given category. Allocating no points to a given category indicated that they believed education produced no benefits to the given category. If responses are grouped, individual, private benefits in the form of “wages of attendees” and “health of attendees” are at least about 24% of the total. Spillover productivity benefits in the form of “economic development,” “technology,” and “wages of non-attendees” are about 39%. If “crime” and “better public decision-making” and “health of non-attendees” are added to spillover productivity benefits, they are about 68% of the total. Despite a separate category for “local purchases,” respondents may be considering the local impact of a nearby community college rather than the local spillover benefits from enhanced human capital. They may be thinking about the cash inflow from state-provided payrolls and expenditures and the impact on local sales. See Siegfried, Sanderson and McHenry (2007) for an exemplary discussion that makes a clear distinction between distributional impacts and efficiency spillovers associated with colleges and universities.

In Appendix Table A1 we report logit results that include two variables that combine the points allocated to quality of life (Crime, Better Public Decision Making, and Health of Non-Attendees) and productivity growth (Economic Development, Technology, and Wages of Non-Attendees). We also explored variables for the effect of a KCTCS campus being located in the county of residence, population density of the county of residence, and years the respondent has lived in Kentucky. None of these variables were statistically significant at conventional levels. The coefficient on Tax Amount, the key variable for estimating mean WTP, is influenced little by their inclusion. A set of dummy variables for regions in Kentucky was included in preliminary regressions, but they were jointly statistically insignificant and were dropped with little effect on remaining variables.

- 14

If the sample is restricted to only respondents who were asked about a 10% expansion, the two control variables for cheap talk and reductions combined can be eliminated. This greatly reduces the sample size from 1023 to 526 and slightly reduces the estimate of mean WTP from $55.84 to $51.67. If the means from ACS 2007 are used where available instead of the means from our sample in evaluating the logit, the estimate of mean WTP is increased slightly from $55.84 to $57.92 [43.05, 72.79]. The nonparametric point estimates of mean WTP are substantially higher. The Turnbull estimate is $72.66 with a 90% confidence interval of [62.02, 83.31] which overlaps the confidence interval for the parametric estimate [41.75, 69.92]. The Kriström estimate of $94.95 [86.28, 103.61] does not overlap. Although we believe our sample is representative overall, we have less confidence that it is representative for the cells for each of the eight tax amounts. The parametric estimates control for differences in income, age, education and other observable characteristics and are our preferred estimates.

- 15

In this study, household and family are used interchangeably for simplicity.

- 16

In order to be consistent with our estimates of total social value, all dollar amounts have been converted to 2007 dollars using the CPI-U.

- 17

We exclude individuals without a high school diploma from our analysis to ensure that the Census data are as comparable as possible with the administrative data from KCTCS.

- 18

To be consistent with previous literature, we express our log coefficients in terms of percentages. However, the precise interpretation of a coefficient b in percentage terms is (eb–1), where e is the exponential function. For comparison, a log coefficient of 0.4 is approximately 49% and a log coefficient of 0.2 is around 22%.

- 19

According to our administrative data from the KCTCS, more than half of the highest degrees awarded are certificates and diplomas.

- 20

For more detail on the data and estimation, see Jepsen et al. (2014).

- 21

Our estimates of the value of a 10% expansion of the KCTCS system, however, are based on the distribution of ages when degrees, diplomas, and certificates are actually earned.

- 22

The lifetime earnings estimates in Table 6 are based on the estimated values of earnings from equations (2) and (3). These estimated values are based on the coefficients for age (and age squared), highest degree, and the constant term, and all these coefficients differ between the Census and KCTCS data. Differences in the coefficients for age and the constant term explain why the estimated lifetime earnings returns to an associate’s degree are higher in KCTCS data than in the Census data even though the coefficients for associate’s degree are lower in the KCTCS data than in the Census data.

- 23

We assume that an expansion of 10% would increase output by 10% because we do not have a strong argument for an alternative. Some programs may have excess capacity and could expand without more funds. Others, particularly the fast growing health fields, are restricted due to current funding for faculty and labs. Moreover, expansion of programs could induce some current students to switch to new programs rather than attracting more students. Switching would lead us to overestimate the gain. However, to the extent that the expansion leads to better matches with students and jobs, then there will be greater productivity that will offset some of the overestimate.

- 24

Review of the focus group tapes confirmed that participants understood that the increase and payment were one-time.

- 25

For an associate’s degree, the estimated costs are $8003 in direct costs of tuition, fees and books, and 1 year of foregone earnings, the average earnings of a high school graduate the year prior to degree receipt. The average of earnings foregone is $19,950. We assume that the costs for a diploma are 75% of the costs for an associate’s degree, and the costs for a certificate are 50% of the costs for an associate’s degree.

- 26

The estimated private return for the Census data contains no controls for occupation. Because a worker’s occupation varies with education level, we also estimate the private returns with Census data that include controls for occupation, and find that the private returns fall from $53.4 million to $42.0 million. This finding suggests that part of the private return of an associate’s degree operates through changes in occupation. The KCTCS administrative data do not contain occupation information.

- 27

The NBER website http://users.nber.org/∼taxsim/marginal-tax-rates/reports estimates of tax rates based on the TAXSIM model. Estimates of average marginal tax rates on income for Federal and Kentucky taxes combined are approximately 27% for 2007.

- 28

For our best estimate of before-tax private financial value of $53.4 million and a tax rate of 27%, the additional tax revenue is $14.4 million. Because of the additional revenue, other taxes could be reduced at the same level of expenditure or additional expenditures could be made without increasing taxes and excess burden could be reduced. Hines (2008) review of the excess burden of taxes suggests the loss could be as high as 75%. Boardman, Greenberg, Vining and Weimer (2011) suggest that a rate of 23% is probably appropriate for income taxes. If we use a marginal excess burden rate of 30%, then the benefit of the additional $14.4 million revenue implies a reduction in excess burden of $4.3 million. Under the assumption that respondents did not consider this subtle benefit, the total social value increases to $97.0 million.

- 29

All estimates shown in Table 8 are positive, but negative values are possible with other combinations of assumptions. For example, if private non-market value is the same size as private financial value and the 90% lower bound on total social value is used, the education externality is negative $8.7 million. We consider this combination unlikely.

- 30

We also estimate a simple model to explore whether there is an area-wide education externality. The model is broadly similar to those found in Rauch (1993), Acemoglu and Angrist (2000), and Moretti (2004a), as well as the reviews by Moretti (2004b) and Lange and Topel (2006). However, no attempt is made to account for sorting. Focusing specifically on the associate’s degree offered by KCTCS, a 1 percentage point increase in the percentage of individuals in an area with at least an associate’s degree is associated with a 0.7% increase in earnings. Sorting has not been addressed, but this result hints that part of the private returns reported in Table 4 that reports earning equations using Census data is actually an education spillover. Results are shown in Appendix B.

- 31

Assumptions made about estimates of total social value matter too. If the lower bound of the 90% confidence interval of willingness to pay ($69.3 million) is used, then net social benefits are –$34.1 million with a benefit cost ratio of about 0.7.

- 32

McMahon (2007) uses a dynamic model of endogenous growth to estimate education externalities that are direct effects as well as externalities that are indirect effects that play out over time in growth and development. We estimate the direct effects and do not attempt to include any indirect effects.

Acknowledgments

For comments we thank Robert Haveman, Magnus Johannesson, Juanna Joensen, Helen Ladd, Peter Mueser, Lashawn Richburg-Hayes, Judith Scott-Clayton, Christian Vossler, John Whitehead and workshop participants at the Australian National University, the Baltic International Center for International Policy Studies, Deakin University, Stockholm School of Economics, University College Dublin, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, University of South Carolina, Xavier University, and the 2009 meetings of the Association of Public Policy and Management, North American Meetings of the Regional Science Association, Society for Benefit Cost Analysis, and Southern Economic Association. Comments from an associate editor and anonymous reviewers improved the paper and are greatly appreciated. Barry Kornstein at the University of Louisville provided assistance in estimating the returns using Census data. Christina Whitfield and Alicia Crouch helped greatly in getting the KCTCS data. Glenn Blomquist acknowledges support of colleagues at the Stockholm School of Economics while on sabbatical. This research was funded in part by the Kentucky Community and Technical College System. The authors alone are responsible for findings and views contained in this paper.

Appendix A

Logistic regression results with additional independent variables.†

| Coefficient | Standard Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax Amount | –0.0048 | *** | 0.0007 |

| HINC $25K-39K | 0.0348 | 0.3023 | |

| HINC $40K-59K | 0.3723 | 0.2969 | |

| HINC $60K-99K | 0.7444 | ** | 0.2956 |

| HINC >$100K | 1.2318 | *** | 0.3362 |

| HINC Missing | –0.2172 | 0.4675 | |

| HS Diploma | –0.1360 | 0.4165 | |

| Some College | 0.3280 | 0.4342 | |

| Associate’s Degree | 0.6016 | 0.4866 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 0.4027 | 0.4500 | |

| Master’s Degree + | 0.2027 | 0.4606 | |

| Age 30–39 | 0.2332 | 0.4773 | |

| Age 40–49 | 0.4137 | 0.4622 | |

| Age 50–64 | 0.8766 | * | 0.4514 |

| Age 65+ | 1.0347 | ** | 0.4946 |

| Age Missing | –0.4638 | 1.1530 | |

| Female | 0.0050 | 0.1723 | |

| White | –0.2710 | 0.3722 | |

| Taken a Class | –0.2575 | 0.2145 | |

| Family Attended | 0.4191 | ** | 0.1816 |

| Know Employee | 0.2970 | 0.1854 | |

| Web | –0.0448 | 0.2464 | |

| Cheap Talk Minus 10 | 0.7994 | *** | 0.1967 |

| Cheap Talk Minus 25 | 0.8500 | *** | 0.1912 |

| Quality of Life | –0.0043 | 0.0073 | |

| Productivity Growth | –0.0009 | 0.0068 | |

| County | 0.2154 | 0.1968 | |

| Population Density | –0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| Years in Kentucky | –0.0014 | 0.0050 | |

| Constant | –1.9132 | ** | 0.8047 |

| Sample Size | 949 | ||

| Likelihood Ratio Statistic | 152.57 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1364 |

†The dependent variable “Definitely Sure” equals one for respondents definitely sure of their affirmative response and zero otherwise. Base categories for income, education, and age are respectively: Under $25,000, Less than a High School Diploma, Age 18–25. Significance is shown as ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1.

Predicted lifetime private financial returns to KCTCS, 2007 dollars.

| Models | Total |

|---|---|

| Total Social Return | $92,694,000 |

| Census – Private Return, with age-adjusted work and survival probabilities | |

| 2% discount rate | $71,965,639 |

| 3.5% discount rate | $53,352,283 |

| 5% discount rate | $40,185,626 |

| KCTCS – Private Return, with age-adjusted work and survival probabilities | |

| 2% discount rate | $79,359,228 |

| 3.5% discount rate | $56,947,577 |

| 5% discount rate | $40,586,713 |

Increase in present value of expected earnings compared to high school diploma.

Appendix B

Wages, Area-wide Education, and OLS Estimates of the Education Externality.

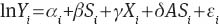

How much higher are a given worker’s earnings if he or she lives in an area with more educated individuals? This model can be illustrated by the following equation:

where Y, S, and X are defined as in equation (2) and ASi measures the level of schooling in the area. Examples of attempts to estimate equation (4) can be found in Rauch (1993), Acemoglu and Angrist (2000), and Moretti (2004a), as well as the reviews by Moretti (2004b) and Lange and Topel (2006).

As we discuss above, one of the problems with estimating equation (B1) is that there may be some unobserved factor about an area that is correlated with the average schooling in an area leading to a correlation between ASi and εi and a biased estimate of δ. In their estimates both Acemoglu and Angrist (2000) and Moretti (2004a) account for this bias using instrumental variables although Lange and Topel (2006) have questioned the validity of their instruments. Given their concerns, and the lack of sufficient variation in the available instruments for Kentucky data, we do not attempt to adjust for any possible bias in our estimates. We present them only to allow a comparison between our estimates of δ found using Kentucky data with the existing estimates using national data.

Table B1 contains the results from a model that estimates spillover effects using the data from the 2000 Decennial Census for Kentucky. (Because the regional education level does not vary within student in the KCTCS administrative data, the spillover effect is contained in the student fixed effect. Therefore, we do not estimate spillover effects with the KCTCS data.) An area is measured as one of the 30 Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMA) in Kentucky; see Blomquist et al., 2007) for details. The PUMAs in Kentucky have a universe population of between 100,000 and 200,000 persons. The sample size after filtering out individuals <25 years of age varies from between 3000 and 8000 per PUMA.

For consistency with previous results, estimates are provided separately for men and for women. So that we can easily compare our estimates with previous estimates, we measure ASi three ways. In columns (1) and (4) ASi is measured as the average years of schooling among residents in an area, which corresponds to the measures used by Rauch (1993) and Acemoglu and Angrist (2000). We compute the average years of schooling for all residents 16 years old and older. In columns (2) and (5) we measure ASi as the percentage of individuals in the area with at least a bachelor’s degree, which corresponds to the measure used by Moretti (2004a). In columns (3) and (6) we measure ASi as the percentage with at least an associate’s degree, which corresponds to the measure used in this paper.

We find a strong association between the level of schooling in an area and an individual’s earnings for all three measures. Looking at the results in columns (1) and (4) we see that a 1 year increase in the average education in an area is associated with an 8% increase in earnings for both men and women. This is slightly higher than Rauch’s (1993) estimates of 2.8 to 5.1%, but corresponds closely to the OLS estimate of 7.3% reported in Acemoglu and Angrist (2000). In columns (2) and (4) we see that a 1 percentage point increase in the percent of residents with a college degree is associated with a 0.7% increase in earnings, which is within the 0.6 to 1.2% range reported by Moretti (2004a). Our OLS estimates are similar to estimates found elsewhere in the literature even though we do not have instrumental variables to control for potential sorting by location.

Next, we compare the estimates of the effect of individual education on earnings results reported in Table 4 with the result in Table B1 when we include measures of educational attainment in an area. The results in column (3) and (6) in Table B1 show that a 1 percentage point increase in the percentage of individuals with at least an associate’s degree is associated with a 0.7% increase in earnings. In addition to these education spillovers, a person who receives an associate’s degree receives a private return of approximately 21% for men and 41% for women (according to Table B1.) These estimated private returns are slightly lower that the private returns reported in Table 4 (24% and 44%). We have not controlled for the potential endogeneity of education, but this pattern of results suggests that part of the private return in Table 4 is actually an education spillover.

Log earnings equation with area-wide education, 2000 U.S. Census data for Kentucky.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Individual Education | ||||||

| <1 Year of College | 0.143*** | 0.145*** | 0.143*** | 0.161*** | 0.164*** | 0.163*** |

| (0.0156) | (0.0156) | (0.0156) | (0.0179) | (0.0179) | (0.0179) | |

| Year or More of College, No Degree | 0.0865*** | 0.0866*** | 0.0846*** | 0.132*** | 0.132*** | 0.131*** |

| (0.0117) | (0.0118) | (0.0117) | (0.0141) | (0.0142) | (0.0141) | |

| Associate’s Degree | 0.209*** | 0.222*** | 0.209*** | 0.416*** | 0.416*** | 0.414*** |

| (0.0184) | (0.0184) | (0.0184) | (0.0183) | (0.0183) | (0.0183) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 0.488*** | 0.484*** | 0.480*** | 0.610*** | 0.605*** | 0.603*** |

| (0.0127) | (0.0128) | (0.0128) | (0.0159) | (0.0161) | (0.0161) | |

| Master’s Degree | 0.508*** | 0.501*** | 0.497*** | 0.791*** | 0.783*** | 0.782*** |

| (0.0192) | (0.0193) | (0.0193) | (0.0197) | (0.0199) | (0.0198) | |

| Professional or Doctoral Degree | 0.898*** | 0.887*** | 0.884*** | 1.029*** | 1.015*** | 1.014*** |

| (0.0231) | (0.0223) | (0.0233) | (0.0351) | (0.0352) | (0.0352) | |

| Region Level Education | ||||||

| Average Years of Schooling | 0.0796*** | 0.0823*** | ||||

| (0.00377) | (0.00447) | |||||

| Percent Bachelor’s or More | 0.00739*** | 0.00746*** | ||||

| (0.00038) | (0.00045) | |||||

| Percent Associate’s or More | 0.00739*** | 0.00728*** | ||||

| (0.00036) | (0.00042) | |||||

| Experience | ||||||

| Potential Years | 0.0702*** | 0.0709*** | 0.0700*** | 0.0616*** | 0.0621*** | 0.0621*** |

| (0.00157) | (0.00157) | (0.00157) | (0.00176) | (0.00176) | (0.00176) | |

| Potential Years Squared | –0.00136*** | –0.00137*** | –0.00137*** | –0.00112*** | –0.00113*** | –0.00114*** |

| (0.0000374) | (0.0000374) | (0.0000374) | (0.0000426) | (0.0000427) | (0.0000427) | |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Black | –0.234*** | –0.233*** | –0.236*** | 0.0122 | –0.0169 | –0.0141 |

| (0.0178) | (0.0178) | (0.0178) | (0.0197) | (0.0198) | (0.0198) | |

| Married | 0.440*** | 0.437*** | 0.438*** | 0.0123 | 0.00822 | 0.00816 |

| (0.0123) | (0.0123) | (0.0123) | (0.0150) | (0.0150) | (0.0150) | |

| Divorced | 0.194*** | 0.195*** | 0.195*** | 0.130*** | 0.127*** | 0.127*** |

| (0.0165) | (0.0165) | (0.0165) | (0.0183) | (0.0183) | (0.0183) | |

| Constant | 8.104*** | 8.912*** | 8.878*** | 7.748*** | 8.592*** | 8.561*** |

| (0.0460) | (0.0153) | (0.0159) | (0.0552) | (0.0189) | (0.0196) | |

| Observations | 38583 | 38583 | 38583 | 37396 | 37396 | 37396 |

| R2 | 0.252 | 0.251 | 0.252 | 0.149 | 0.147 | 0.148 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1. The dependent variable is the log of annual earnings. All earnings have been converted to 2007 dollars using the CPI-U. Numbers are in bold to draw attention to them because they are important and discussed in the text.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Angrist, J. (2000). How large are the social returns to education? Evidence from compulsory schooling laws. In B. S. Bernanke & K. Rogoff (Eds.), NBER Macroannual 15 (pp. 9–59). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Arrow, K. J., Solow, R., Portney, P., Leamer, E. E., Radner, R., & Howard, S. (1993). Report on the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. In Federal Register (Vol. 58, Iss. 10, pp. 4602–4614). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.Suche in Google Scholar

Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (2007). Education and consumption: the effects of education in the household compared to the marketplace. Journal of Human Capital,1(1), 9–35.10.1086/524715Suche in Google Scholar

Blomquist, G. C., Coomes, P. A., Jepsen, C., Koford, B., Kornstein, B., & Troske, K. R. (2007). The individual, regional, and state economic impacts of Kentucky community and technical colleges. Center for Business and Economic Research, University of Kentucky, http://cber.uky.edu/pdf/CBER_UL_KCTCSReport_10-2007.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Blumenschein, K., Johannesson, M., Blomquist, G., Liljas, B., & O’Conor, R. (1997). Hypothetical versus real payments in Vickery auctions. Economics Letters,56(2), 177–180.10.1016/S0165-1765(97)81897-6Suche in Google Scholar

Blumenschein, K., Johannesson, M., Blomquist, G., Liljas, B., & O’Conor, R. (1998). Experimental results on expressed certainty and hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Southern Economic Journal,65(1), 169–177.Suche in Google Scholar

Blumenschein, K., Blomquist, G. C., Johannesson, M., Horn, N., & Freeman, P. R. (2008). Eliciting willingness to pay without bias: Evidence from a field experiment. The Economic Journal,118(525), 114–137.10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02106.xSuche in Google Scholar

Boardman, A. E., Greenberg, D. H., Vining, A. R., & Weimer, D. L. (2011). Cost-benefit analysis: concepts and practice. (4th ed.). Boston: Prentice Hall.Suche in Google Scholar

Cain, T. (2011). Individual income tax returns, by state, 2007. Statistics of Income Bulletin, 30(1), 174–234.Suche in Google Scholar

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In O. C. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), The handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1801–1863). New York: Elsevier Science, North-Holland.Suche in Google Scholar

Carson, R. T., (2012). Contingent valuation: a practical alternative when prices aren’t available. Journal of Economic Perspectives,26(4), 27–42.10.1257/jep.26.4.27Suche in Google Scholar

Carson, R. T., & Groves, T. (2007). Incentives and informational properties of preference questions. Environmental and Resource Economics, 37(1), 181–210.10.1007/s10640-007-9124-5Suche in Google Scholar

Champ, P. A., & Bishop, R. C. (2001). Donation payment mechanisms and contingent valuation: An empirical study of hypothetical bias. Environmental and Resource Economics,19(4), 383–402.10.1023/A:1011604818385Suche in Google Scholar

College Board (2008). Winning the skills race and strengthening America’s middle class: an action agenda for community colleges. New York: College Board. http://professionals.collegeboard.com/profdownload/winning_the_skills_race.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Cummings, R. G. & Taylor, L. O. (1999). Unbiased value estimates for environmental goods: a cheap talk design for the contingent valuation method. American Economic Review,89(3), 649–665.10.1257/aer.89.3.649Suche in Google Scholar

Cutler, D. M. & Lleras-Muney, A. (2008). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. In J. House, R. Schoeni, G. Kaplan & H. Pollack (Eds.), Making Americans healthier: social and economic policy as health policy (pp. 29–60). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.Suche in Google Scholar

Dee, T. S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics,88(9–10), 1697–1720.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

Demming, D. (2011). Better schools, less crime. Quarterly Journal of Economics,126(4), 2063–2115.10.1093/qje/qjr036Suche in Google Scholar

Epstein, R. A. (2003). The regrettable necessity of contingent valuation. Journal of Cultural Economics,27(3), 259–274.10.1023/A:1026375220210Suche in Google Scholar

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Glaeser, E. L. & Saks, R. E. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics,90(6–7), 1053–1072.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.08.007Suche in Google Scholar

Grossman, M. (2006). Education and nonmarket outcomes. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.) The handbook of economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 577–633). Amsterdam: Elsevier, North-Holland.Suche in Google Scholar

Hanushek, E. A., Yui Leung, C. K., & Yilmaz, K. (2003). Redistribution through education and other transfer mechanisms. Journal of Monetary Economics,50(8), 1719–1750.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2003.01.004Suche in Google Scholar

Harrison, G. W. (2006). Experimental evidence on alternative environmental valuation methods. Environmental and Resource Economics, 34(1), 125–162.10.1007/s10640-005-3792-9Suche in Google Scholar

Hausman, J. (2012). Contingent valuation: from dubious to hopeless. Journal of Economic Perspectives,26(4), 43–56.10.1257/jep.26.4.43Suche in Google Scholar

Haveman, R. H. & Wolfe, B. L. (1984). Schooling and economic well-being: The role of nonmarket effects. Journal of Human Resources,19(4), 378–407.Suche in Google Scholar

Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L. J. & Todd, P. E. (2006). Earnings functions, rates of return and treatment effects: the Mincer equation and beyond. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), The handbook of economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 307–458). Amsterdam: Elsevier, North-Holland.Suche in Google Scholar

Hilmer, M. J. (1998). Post-secondary fees and the decision to attend a university or a community college. Journal of Public Economics,67(3), 329–348.10.1016/S0047-2727(97)00075-3Suche in Google Scholar

Hines, J. R., Jr. (2008). Excess burden of taxation. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online. Palgrave Macmillan. 19 June 2013. http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_E000315.Suche in Google Scholar

Jacobson, L. S., LaLonde, R. J. & Sullivan, D. G. (2005a). Estimating the returns to community college schooling for displaced workers. Journal of Econometrics, 125(1–2), 271–304.10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.04.010Suche in Google Scholar

Jacobson, L. S., LaLonde, R. J., & Sullivan, D. G. (2005b). The impact of community college retraining on older displaced workers: should we teach old dogs new tricks? Industrial and Labor Relations Review58(3), 398–415.10.1177/001979390505800305Suche in Google Scholar

Jepsen, C., Troske, K. R., & Coomes, P. A. (2014). The labor market returns for community college degrees, diplomas, and certificates. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(1), 95–121.10.1086/671809Suche in Google Scholar

Johansson, P.-O. (1995). Evaluating health risks: an economic approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511582424Suche in Google Scholar

Kane, T. J., & Rouse, C. E. (1995). Labor market returns to two-year and four-year schools. American Economic Review,85(3), 600–614.Suche in Google Scholar

Kenkel, D. S. (1991). Health behavior, health knowledge, and schooling. Journal of Political Economy,99(2), 287–305.10.1086/261751Suche in Google Scholar

Kling, C. L., Phaneuf, D. J., & Zhao, J. (2012). From Exxon to BP: Has some number become better than no number? Journal of Economic Perspectives,26(4), 3–26.10.1257/jep.26.4.3Suche in Google Scholar

Lange, F. & Topel, R. (2006). The social value of education and human capital. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), The handbook of economics of education, (Vol. 1, pp. 459–509). Amsterdam: Elsevier, North-Holland.Suche in Google Scholar

List, J. A. & Gallet, C. A. (2001). What experimental protocol influence disparities between actual and hypothetical stated values. Environmental and Resource Economics,20(3), 241–254.10.1023/A:1012791822804Suche in Google Scholar

Little, J. & Berrens, R. (2004). Explaining disparities between actual and hypothetical stated values: further investigation using meta-analysis. Economics Bulletin, 3(6), 1–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Lochner, L. (2011a). Education policy and crime. In P. J. Cook, J. Ludwig & J. McCrary (Eds.), Controlling crime: strategies and tradeoffs (pp. 465–515). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226115139.003.0011Suche in Google Scholar

Lochner, L. (2011b). Non-production benefits of education: crime, health, and good citizenship. In E. Hanushek, S. Machin & L. Woessmann (Eds.), The handbook of economics of education (Vol. 4, pp. 183–282). Amsterdam: Elsevier, North-Holland.10.3386/w16722Suche in Google Scholar

Lochner, L. & Moretti, E. (2004). The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American Economic Review, 94(1), 55–189.10.1257/000282804322970751Suche in Google Scholar

McMahon, W. W. (2007). An analysis of education externalities with applications to development in the deep south. Contemporary Economic Policy,25(3), 459–482.10.1111/j.1465-7287.2007.00041.xSuche in Google Scholar

McMahon, W. W. (2009). Higher learning, greater good: the private and social benefits of higher education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.10.1353/book.3416Suche in Google Scholar

McMahon, W. W. & Oketch, M. (2010). Bachelor’s and short degrees in the UK and US: New social rates of return and non-market effects on development. Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies Working Paper 12.Suche in Google Scholar

Meghir, C., Palme, M. & Schnable, M. (2012). The effect of education policy on crime: An intergenerational perspective. NBER Working Paper 18145.10.3386/w18145Suche in Google Scholar

Michael, R. T. (1973). Education in non-market production. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), 306–327.10.1086/260029Suche in Google Scholar

Milligan, K., Moretti, E., & Oreopoulos, P. (2004). Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1667–1695.10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.10.005Suche in Google Scholar

Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, experience, and earnings. New York: Columbia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Moore, M. A., Boardman, A. E., Vining, A. R., Weimer, D. L. & Greenberg, D. H. (2004). Just give me a number! Practical values for the social discount rate. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(4), 789–812.10.1002/pam.20047Suche in Google Scholar

Moretti, E. (2004a). Estimating the social return to higher education: evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional data. Journal of Econometrics, 121(1–2), 175–212.10.1016/j.jeconom.2003.10.015Suche in Google Scholar

Moretti, E. (2004b). Human capital externalities in cities. In V. Henderson & J. F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of urban and regional economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2243–2291). Amsterdam: North Holland.10.1016/S1574-0080(04)80008-7Suche in Google Scholar

Oreopoulos, P. & Salvanes K. G. (2009). How large are returns to schooling? Hint: Money isn’t everything. NBER Working Paper No. 15339.10.3386/w15339Suche in Google Scholar

Oreopoulos, P. & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: the nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives,25(1), 159–184.10.1257/jep.25.1.159Suche in Google Scholar

Poe, G. L., Clark, J. E., Rondeau, D. & Schulze, W. D. (2002). Provision point mechanisms and field validity tests of contingent valuation. Environmental and Resource Economics,23(1), 105–131.10.1023/A:1020242907259Suche in Google Scholar

Rauch, J. (1993). Productivity gains from geographic concentration of human capital: Evidence from the cities. Journal of Urban Economics,34(3), 380–400.10.1006/juec.1993.1042Suche in Google Scholar

Rosenthal, S. S. & Strange, W. C. (2008). The attenuation of human capital spillovers. Journal of Urban Economics,64(2), 373–389.10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.006Suche in Google Scholar

Siegfried, J. J., Sanderson, A. R. & McHenry, P. (2007). The economic impact of colleges and universities. Economics of Education Review,26(5), 546–558.10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.07.010Suche in Google Scholar

Turner, C., Tamura, R., Mulholland, S. E. & Baier, S. (2007). Education and income of the United States: 1840–2000. Journal of Economic Growth,12(2), 101–158.10.1007/s10887-007-9016-0Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. Bureau of Census (2007). American community survey. Public Use Microdata Sample Files. Population and Housing Records.Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2008). Digest of education statistics tables and figures. Washington, DC: http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d08/tables/dt08_189.asp.Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (2006). National vital statistics reports. 54, no. 14, April 19, 2006 (as revised March 28, 2007), http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_14.pdf. pp. 10–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Wheeler, C. H. (2008). Human capital externalities and adult mortality in the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2007-045C. St. Louis, MO.10.2139/ssrn.1023984Suche in Google Scholar

Whitehead, J. C. (2002). Incentive incompatibility and starting-point bias in iterative valuation questions. Land Economics,78(2), 285–297.10.2307/3147274Suche in Google Scholar

Winters, J. V. (2012). Human capital externalities and employment differences across metropolitan areas of the U.S. IZA Discussion Paper 6869.Suche in Google Scholar

White House (2010). Remarks by the President and Dr. Jill Biden at White House Summit on community colleges (October 5). URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2010/10/05/remarks-president-and-dr-jill-biden-white-house-summit-community-college Referenced November 22, 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolfe, B. L. & Haveman, R. H. (2002). Social and nonmarket benefits from education in an advanced economy. In Y. K. Kodrzycki (Ed.), Education in the 21st Century: meeting the challenges of a changing world (pp. 97–131). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/conf/conf47/conf47g.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Yamarik, S. J. (2008). Estimating returns to schooling from state-level data: A macro-Mincerian approach. The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 8(1) (Contributions), Article 23.10.2202/1935-1690.1571Suche in Google Scholar

©2014 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the editors

- Letter from the Editors for the JBCA, Volume 5, Issue 1 (2014) June 17, 2014

- Articles

- Estimating the social value of higher education: willingness to pay for community and technical colleges

- A benefit-cost framework for early intervention to prevent sex trading

- Behavioral economics and policy evaluation

- Role of BCA in TIGER grant reviews: common errors and influence on the selection process

- Identifying the analytical implications of alternative regulatory philosophies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the editors

- Letter from the Editors for the JBCA, Volume 5, Issue 1 (2014) June 17, 2014

- Articles

- Estimating the social value of higher education: willingness to pay for community and technical colleges

- A benefit-cost framework for early intervention to prevent sex trading

- Behavioral economics and policy evaluation

- Role of BCA in TIGER grant reviews: common errors and influence on the selection process

- Identifying the analytical implications of alternative regulatory philosophies