Abstract

The reigns of Adad-nārārī II (911–891) and his son Tukultī-Ninurta II (890–884) are vital to understanding the rise of Neo-Assyria; yet, reconstruction of these is hampered by the scarce and fragmentary sources available. This study surveys the reigns of these two kings, and examines five fragmentary early Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions from the city of Aššur published in 2009 by Frahm within Keilschrifttexte aus Assur literarischen Inhalts 3, providing solid ascriptions of three of these to Adad-nārārī II and two to Tukultī-Ninurta II on philological and historical grounds. These findings are then integrated into present knowledge of this period in order to present new portraits of these kings’ respective reigns. This results in a clearer historical articulation of Adad-nārārī II’s remarkably successful incumbency, particularly shedding light on his early victories. In turn, Tukultī-Ninurta II’s difficult reign spent consolidating his father’s territorial gains can also be better understood. Interestingly, various innovations can be ascribed to this latter king, not least the ‘calculated frightfulness’ for which his son would become so (in)famous within Assyriology. Finally, some repercussions of these findings for the study of 10th and 9th century royal inscriptions are explored.

1 Introduction

Reconstructing the events of the early Neo-Assyrian period remains an exciting but fraught challenge:[1] In the span of a few generations, a kingdom reeling from the deprivations of the 11th and 10th centuries became a dominant state once more within the ancient Near East,[2] before ultimately overcoming its own structural constraints in the 8th century and attaining ‘true’ empire. The reigns of the early Neo-Assyrian kings Adad-nārārī II (911–891) and Tukultī-Ninurta II (890–884) are crucial in understanding the beginnings of this process, but they continue to suffer from a fragmentary state of documentation, and hence negligence on the part of scholars.[3]

This contribution seeks to presents an historical analysis of five early Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions from Aššur (Qal‘at Širqāṭ, Iraq) published by Frahm (2009b) within the third volume of the series Keilschrifttexte aus Assur literarischen Inhalts, for which he only furnished tentative suggestions as to their precise commissioner.[4] As will be demonstrated, close historical, historical-geographical, and philological analysis can safely accord each text an Assyrian monarch. While fragmentary, these texts are still rich in information with which to fill lacunae remaining within these kings’ respective reigns (see the summary of findings in Table 1).

Texts discussed and a summary of this study’s new historical findings.

| Text | Reference in Frahm 2009b | Main findings |

|---|---|---|

| KAL 3: 45–46 (= RIMA.0.101.21–22) | 92–97; pls. pp. 231–32; 233 | Tukultī-Ninurta II’s defeat of Nirdun & Na’iri, of Irbibu on the Upper Ḫābūr, discovery of a rock relief in the Tūr ‘Aḇdīn, and the quashing of a rebellion in Tillê and Kaḫat (ca. 890–887). |

| KAL 3: 47 | 97–98; pl. p. 234 | Adad-nārārī II’s first and second Na’iri campaigns and his defeat of Katmuḫi (909-ca. 905). |

| KAL 3: 48 | 98–101; pls. pp. 235–36 | Adad-nārārī II’s defeat of Ušḫu and Atkun and Qumānû (911), and further very fragmentary campaigning including a pre-901 campaign to the Middle Euphrates and a hunting tally. |

| KAL 3: 53 | 104–05; pl. p. 239 | Adad-nārārī II’s fourth Na’iri campaign, defeat of the Aḫlamû, and a campaign to the Middle Euphrates (ca. 905–901). |

| KAL 3: 56 | 108–111; pls. pp. 241–42; photo 274 | Side a.: Various small early campaigns of Tukultī-Ninurta II (ca. 890–889). Side b.: Reports of his later defeat and capture of Apâ of Ḫubuškia and quelling of a revolt of Naṣībīna and further march into the Tūr ‘Aḇdīn (887). Side a. unusually displays the deliberate striking through of many lines. |

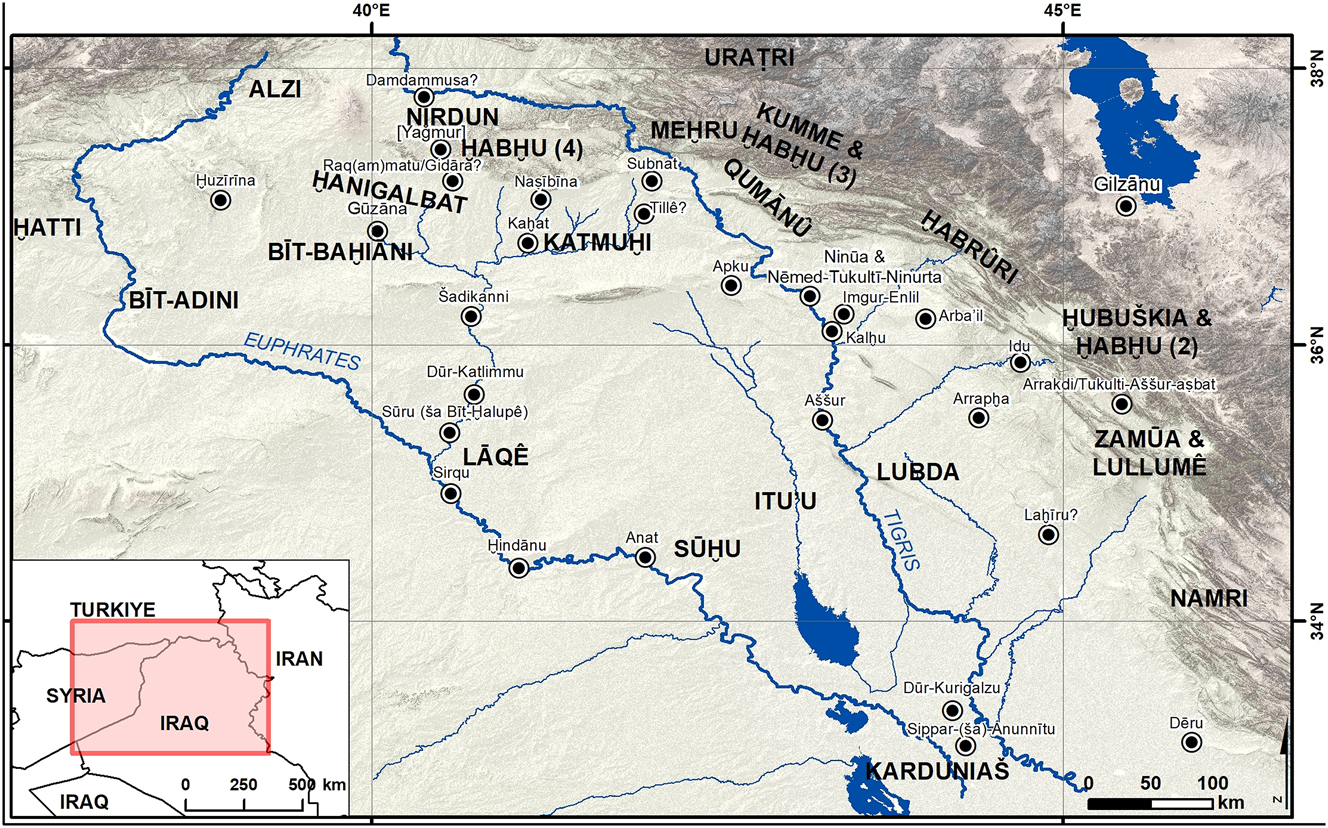

For the sake of brevity and considering their fine state of publication, text editions are not presented, but rather their pertinent contents are summarised and quoted where necessary; the five texts are here discussed sequentially in approximate chronological order (i.e. KAL 3: 48, 47, 53, 56, 45–46).[5] These five textual-historical analyses’ findings are then integrated into what is known of the reigns of Adad-nārārī II and Tukultī-Ninurta II, and presented in two historical summaries. Finally, new avenues of historiographical research yielded by this work are identified and considered. Prior to the discussion of the unattributed texts, however, it is vital to outline the present state of knowledge on both reigns, and overviews of those surrounding them, as a solid historical foundation for the ensuing analyses (see also the map in Figure 1).

Key toponyms mentioned in this paper. Map by Bartłomiej Szypuła.

2 Adad-nārārī II’s Reign and its Remaining Lacunae

The reign of Adad-nārārī II is generally characterised as a period of sweeping reconquest of Assyria’s erstwhile territory (e.g Grayson 1982: 249–51; Shibata 2023: 201–09). The backbone to reconstructing his reign is an extended semi-annalistic text from Aššur dubbed the ‘Gula Temple Inscription’ by Dewar (2019) after its appended building report (RIMA.0.99.2). Its historical portion is divided into two parts: The first is an unusual geographical summary (ll. 23–38) of the king’s achievements prior to 901 divided into multiple ruled sections culminating in the rebuilding of the city of Apku (’Abū Māryā, Iraq); the second is an extended annalistic section (ll. 39–119) running from 901 to 894 and describing his seven campaigns to Ḫanigalbat (Upper Ḫābūr plain, Syria and Turkey), some additional campaigning in the Zagros mountains including to Kumme (vicinity of Beytuşşebap, Turkey), and a march along the Euphrates. While this provides detailed coverage of the second half of his reign, the initial decade of his reign up to 901 (the ‘pre-Apku’ period) can only be understood schematically.

This situation is somewhat alleviated by another text, RIMA.0.99.1 (= KAL 3: 15), dated to 6th Kislīmu (IX) 909 which, although fragmentary, does report on a defeat of Qumānû (vicinity of the Zāḫū plain, Iraq) in his accession year, then (after a break) the conquest of Arrapḫa (Kirkūk, Iraq),[6] followed by yet another lacuna, and then a conquest on the Tigris involving 40 cities and the deportation of three more,[7] and then a final campaign dated 4th Araḫsamnu (VIII)[8] to Ḫabḫu (3)[9] and Meḫru (probably the Şırnak plain, Turkey), implying that the final two episodes occurred just before the inscription’s commission, in late 909.

Mention of Arrapḫa raises a tantalising issue, that of his assault upon Karduniaš known to have occurred prior to 901 (Shibata 2023: 203–04). The Synchronistic Chronicle mentions two (undated) wars between Assyria and Babylonia, the first clearly corresponding to that sketched in the pre-Apku summary, and the second evidently after the events of RIMA.0.99.2, at the close of the king’s reign (ABC 21 iii 1–21). The mention of Arrapḫa in RIMA.0.99.1 suggests that the first Assyro-Babylonian war was prior to 909, but it could also have unfolded in stages (see Fuchs 2011: 263 with ns.) The second, post-884 conflict seems to have been included in KAL 3: 16–17 (= RIMA.0.99.4), which presents a very late geographical summary (13’–52’) based on that of RIMA.0.99.2 23–38, albeit with additional content, some deletion or telescoping of earlier achievements, and a more logical geographical organisation. Comparison of these ‘pre-’ and ‘post-Apku’ summaries is revealing (Table 2):

The contents of the ruled sections of the pre- and post-Apku summaries of Adad-nārārī II with known dates.

| RIMA.0.99.2 | KAL 3: 16–17 = RIMA.0.99.4 |

|---|---|

| (23–25) marched from the other side of the Lower Zāb (the region Lullumê, Ḫabḫu (1) & Zamūa) to passes of Namri; made Qumānû submit (911) incl. Meḫru (909), Salua & Uraṭri | (13’–20’) marched from the other side of the Lower Zāb (the region Lullumê, Inner Ḫabḫu & Zamūa) to passes of Namri; made Qumānû submit (911) incl. Meḫru (909), Salua & Uraṭri; aided Kumme, sacrificed there, defeated enemy Ḫabḫu (3)-lands (896–895) |

| (26–29) takes control of & annexes all Katmuḫi; victor over all Karduniaš; defeated Šamaš-mudammiq (King of Babylonia) from Yalman to Turān; Laḫīru (1) to Ugār-Sallum appended to border; Dēru captured; Arrapḫa and Lubdu (Babylonian fortresses) annexed | (21’–26’) takes control of & annexes all Katmuḫi; marched 4th time to Na’iri (4 additional broken lines mentioning horses for chariots and tax) |

| (30–33) marched 4th time to Na’iri, captured Inner Ḫabḫu & cities Naḫur (and) Ašnaku; constantly traversed great mountains; captured cities of the land of Natbu; turned all Alzi to ruins, took hostages, imposed tribute and tax; defeated Aḫlamû-Arameans; received Sūḫu’s tribute | (27’–34’) Defeated Šamaš-mudammiq (King of Babylonia) from Yalman to Turān; Laḫīru (1) to Ugār-Sallum appended to border; Dēru captured; Arrapḫa and Lubdu (Babylonian fortresses) annexed (4 additional broken lines about Karduniaš [post-893]) |

| (34–35) Idu and Zaqqu (Assyrian fortresses) annexed; (reclaimed) cities Arinu, Turḫu, & Zaduru from Šubria | (35’–38’ – broken) |

| (36–38) Restoration of Apku (902) | (39’–41’) Defeated & plundered Sūḫu up to […] |

| (39–119) Conventional annalistic account of Ḫanigalbat, Zagros and Kumme campaigns and march to Middle Euphrates (901–894) | (42’–51’) Marched 7th time to Ḫanigalbat, defeated Nūr-Adad, imposed dominance over region |

| (52’onwards – broken) |

In KAL 3: 16–17, not only are Kumme and Ḫanigalbat now mentioned in summary (thus postdating 894), but the otherwise identical Karduniaš section is also supplemented with four additional (unfortunately broken) lines (31’–34’) describing the new conflict, and the section on Sūḫu (‘Āna and Ḥadīṯa Districts, Iraq) is extended from mere mention of tribute to a brief (but broken) description of Sūḫu’s defeat, implying further campaigning there. In turn, the Ḫabḫu (2) beyond the Lower Zāb has now become Inner Ḫabḫu (l. 14’), demonstrating deeper penetration of the Zagros, which must correspond to the defeat of Sikkur and Sappānu in 896 (RIMA.0.99.2 80–90). It remains unclear what must have filled the broken section of KAL 3: 16–17 35’–38’.

A final, unusual source is Tukultī-Ninurta II’s unique stele from Sirqu (Tall ‘Ašāra, Syria).[10] This curious Medioeuphratine monument (perhaps a kudurru?) seems to have been a pre-existing local sculpture of a mythological scene to which an ad hoc inscription and an Aramaicising carving of a deity (or Assyrian king?) were added.[11] Quite uniquely, it does not directly commemorate Tukultī-Ninurta II’s own deeds, but rather those of his father:

(ll. 1–2; 6–7) Adad-nārārī šar māt Aššur dā’iš Lāqê … Tukultī-Ninurta māršu šarru e[ršu …] ša abūšu īpušu šū īpuš […]

Adad-nārārī (II), king of Assyria, trampler of (the city of) Lāqê … Tukultī-Ninurta (II), his son, the wise king […], did that which his father had done

This inscription alludes to a campaign to the Middle Euphrates by Tukultī-Ninurta II which would tally well with the mention of Lāqê in his summary inscriptions (see below); it also implies that Adad-nārārī II violently subdued this region (indeed, uru La-qé-e would imply that Sirqu itself had been taken), although it is unclear as to whether this would have been before or after the peaceful march of 894, in the course of which this is unlikely to have occurred.[12] Moreover, it intimates that Adad-nārārī II himself did not create stelae outside of Assyria, and his son felt compelled to improvise such a monument while in Sirqu. Certainly, no rock reliefs or stelae of Adad-nārārī II have yet been found, nor do his inscriptions mention such activities. In turn, Aššur-nāṣir-apli II mentions only stelae of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I and Tukultī-Ninurta II at the Subnat source (Kebeli, Turkey). The hypothesis might hence be posed that Tukultī-Ninurta II was the first Neo-Assyrian king to create such monuments, as will be further explored. From all of this information, the following conservative reconstruction of Adad-nārārī II’s reign may be presented see (Table 3):

A summary of the hitherto-known events of Adad-nārārī II’s reign and their sources.

| 911 | AN II’s accession and campaign to Qumānû | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 10–19; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 15’-16’ | |

| Mid-late 911 to ca. mid 910 | (10–15 lines of campaign narrative, either various smaller campaigns or 1–2 larger campaigns) | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 20-ca. 30 | |

| ca. mid 910 to mid-909 | Campaign and annexation of Arrapḫa. War with Babylonia probably initiated | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. ca. 30 | |

| Mid-late 909 | Campaign to the Tigris, defeat of 40 cities, deportation of 3 others | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 1’–5’ | |

| 4th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 909 | Campaign against Ḫabḫu (3) & Meḫru | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 6’–9’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 24–25; KAL 3: 16–17 16’ | |

| 6th Kislīmu (IX) 909 | Renovation of quay at Aššur completed | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 10’–20’ | |

| 908–901 | Campaign to Salua and Uraṭri. Defeat of Babylonia. Campaign to Lullumê, Zamūa, Ḫabḫu (2), and Namri. 4 campaigns to Na’iri. Conquest of Katmuḫi. Defeat and resettlement of the Aḫlamû. Campaign to Middle Euphrates including Sūḫu. Reconquest of Arinu, Turḫu, & Zaduru from Šubria? | RIMA.0.99.2 23–35; KAL 3: 16–17 13’–34’; cf. ABC 21 iii 1–7; RIMA.0.100.1004? | |

| 901 or (immediately?) prior | Renovation of Apku completed. | RIMA.0.99.2 36–38 | |

| 901 | 1st Ḫanigalbat campaign. Nūr-Adad of Naṣībīna defeated at Pa’uza | RIMA.0.99.2 39–41 | |

| 900 | 2nd Ḫanigalbat campaign. Battle at Naṣībīna. Yaridu raided. Saraku occupied with the region’s crops | RIMA.0.99.2 42–44 | |

| 899 | 3rd Ḫanigalbat campaign. Huzīrīna taken. Mamlī defeated. Bīt-Adini sends diplomatic gift | RIMA.0.99.2 45–48 | |

| 898 | 4th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Mūquru of Raqamātu/Gidāra defeated | RIMA.0.99.2 49–60 | |

| 897 | 5th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Tribute received | RIMA.0.99.2 61 | |

| 896 | Earlier | 6th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Naṣībīna defeated after siege. Nūr-Adad removed and new client king installed | RIMA.0.99.2 62–80; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 48’–50’ |

| Later | Campaign to Sikkur and Sappānu | RIMA.0.99.2 80–90 | |

| 15th Simānu (III) 895 | 1st campaign to Kumme | RIMA.0.99.2 91–93; KAL 3: 16–17 17’–19’ | |

| Nisannu (I) 894 | 2nd campaign to Kumme | RIMA.0.99.2 94–96; KAL 3: 16–17 19’–20’ | |

| Simānu (III) 894 | 7th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Tribute collected. Campaign to the Middle Euphrates | RIMA.0.99.2 97–119; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 51’ | |

| 17th Abu (V) 893 | Renovation of Gula Temple at Aššur completed | RIMA.0.99.2 128–34 | |

| Late 893 to 891 | 2nd Babylonian war and subsequent peace treaty | KAL 3: 16–17 30’–34’; cf. ABC 21 iii 8–21 | |

| 2nd campaign to Sūḫu (after Babylonian war) | KAL 3: 16–17 39’–41’ | ||

| (other campaigns?) | KAL 3: 16–17 35’–38’; 52’ onwards | ||

| 891 | AN II dies | ||

From this summary, it is evident that the historian’s most pressing task is to establish an internal chronology of events between mid-late 911 to mid-909 and between 908 and 901. As this contained extensive campaigning in every direction and a momentous war with Babylonia, the order and tempo of these events would reveal a great deal about Assyria’s strategic motivations at this time.

3 Reconstructing the Missing Half of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s Reign

Studies of the reign of Tukultī-Ninurta II tend to emphasise its brevity and this ruler’s continuation of his predecessor’s policies; while some authors have underlined the restricted nature of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s campaigning (e.g. Grayson 1982: 251–53), Shibata (2023: 209–13) has recently presented a more positive assessment of this king. His reign’s state of preservation is much the same as for Adad-nārārī II.[13] The only extended annalistic text (RIMA.0.100.5 [+ KAL 3: 19–20]) is frustratingly broken, providing a narrative only from late 887 to 885.[14] This can be summarised in the following table (Table 4):

Campaigns of Tukultī-Ninurta II recorded in RIMA.0.100.5.

| Date | Event and Line Number |

|---|---|

| Late 887 | Conclusion of a campaign to Na’iri and Kāšiāru, TN II returns to Aššur (1–3) |

| Late 887 or very early 886 | Aftermath of the prior campaign, Bīt-Zamāni campaigns in Assyria’s name and forward tribute and hostages to TN II in Ninūa (4–8) |

| Early 886 | Rebellion of a ‘principal he’a in a piedmont region. Insurrectionist pursued up to difficult mountains.b TN II dispatches troops from Ninūa. They return with silver, gold and property (9–10) |

| 1st Simānu (III) 886 | TN II campaigns to Bīt-Zamāni (11–29) |

| 17th Tašrītu (VII) 886 | Campaign beyond Ḫabrûri to Ladānu (western Zamūa) (30–40) |

| 26th Nisannu (I) 885 | March to Babylonia, defeat of nomads in the Wādī aṯ-Ṯarṯār, tribute of Sūḫu, Lāqê and Lower Ḫābūr (41–127) |

| Prior to 9th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 885 | A single broken line refers to another (presumably unimportant) campaign (127) |

-

aThe present author uses the terms ‘principal he’ and ‘barbarian they’ to denote the foes engaged by Assyrian kings where their names are broken, and only suffixes (i.e. -šu and -šunu) survive. In Assyrian inscriptions, the former generally refers to individual leaders of ‘organised’ polities, while the latter is used to denote more ‘loosely’ structured groups such as nomads or mountain groups. bThe expression adi šadî eqli namrāṣi (RIMA.0.100.5 10) is tantalising. The closest parallels are in Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I’s description of his battles at Katmuḫi and in the Zagros (RIMA.0.87.1 i 73; ii 70; iii 42; 51; 97; iv 14). The implication here seems to be that the engagement occurred on accessible piedmont before the forces were chased into a rough mountain landscape.

From this, it is evident that a campaign to Na’iri (eastern Taurus and northern Zagros mountains) must have occurred late in 887, and that Bīt-Zamāni (vicinity of Diyarbakır, Turkey) followed this up with a campaign of their own which assisted Assyria. Tukultī-Ninurta II’s march to Bīt-Zamāni from Ninūa (Naynawā, Iraq) began on the 1st Simānu (III), a significant date also chosen by other kings to begin their campaigns (Frahm 2009b: 54), implying that it was carefully planned; that Tukultī-Ninurta II previously dispatched a force from Ninūa to quell a rebellion while remaining at Ninūa also implies that he was still in the process of massing his troops for the assault on the Upper Tigris, and thus that this must have occurred shortly beforehand in the spring. Considering that Bīt-Zamāni was still in Tukultī-Ninurta II’s graces following his campaign of 887, and that the Upper Tigris campaign of 886 was planned, it is hence likely that Bīt-Zamāni’s own campaigning must either have occurred very early in 886 (thus giving Tukultī-Ninurta II sufficient time to marshal his forces), or at the end of 887.

The three-and-a-half years prior to these events (alongside perhaps his final year) can only be reconstructed with the assistance of various near-identical geographical summary inscriptions intended for his unfinished residence at Nēmed-Tukultī-Ninurta (Qaḍīya, Iraq), here referred to as RIMA.0.100.6 (found at Naynawā = Thompson and Hutchinson 1929: 117–18; pl. 41) and Qaḍīya 1–3 (= Ahmad 2000).[15] The Ninūa copy seems the most trustworthy, as the Qaḍīya exemplars contain some howlers, such as one text repeating Sippar-ša-Šamaš (Tall Abū Ḥabba, Iraq) twice, and the other repeating the doublet Dūr-Kurigalzu (‘Aqar Qūf, Iraq) and Sippar-ša-Šamaš twice.[16] A composite rendering of the geographical section of RIMA.0.100.6 and Qaḍīya 1–3 is here provided:

kāšid (mātāt) Na’iri ana pāṭ gimrīša šarru ša ištu ebertān Idiqlat adi (māt) Ḫatti (māt) Lāqê ana siḫirtīša Na’iri ana pāṭ gimrīša (māt) Sūḫi adi (māt) Rāpiqi ištu nērebe ša (māt) Ḫabrûri adi (māt) Gilzāni Apâ šar {var. ebertān} (māt) Hubuškia qereb tamḫāri qāssu iṣbatu ištu nērebe ša Bābite adi (māt) Ḫašmar (māt) Zamūa ana siḫirtīša ištu Zāba elî adi Til-Bāri ša ellān (māt) Zabban (māt) Ḫirimmu (māt) Ḫarutu birāte ša māt Karduniaš ištu Ṣuṣi ša eli Idiqlat adi Dūr-Kurigalzi ištu Dūr-Kurigalzi adi Sippar-ša-Šamaš Sippur-ša-Anunnītu (?) (māt) Aramu qāssu ikšudu

Conqueror of (the lands of) Na’iri to its farthest extent, the king who took in the midst of the fray from the other side of the Tigris to (the land of) Ḫatti, (the land of) Lāqê and its environs, (the lands of) Na’iri to its furthest extent, (the land of) Sūḫu up to (the land of) Rāpiqu (and) from the passes of (the land of) Ḫabrûri to (the land of) Gilzānu (and as captive) Apâ, king of (the land of {var. the city of}) Ḫubuškia {var. Gilzānu on the other side of Ḫubuškia}. He captured from the passes of Bābite to (the land of) Ḫašmar (the land of) Zamūa and its environs, from the Lower Zāb to Til-Bāri from upstream of (the land of) Zabban, (the land of) Ḫirimmu and (the land of, var. the city of) Ḫarutu, fortresses of Karduniaš from the city of Ṣuṣi on the Tigris to Dūr-Kurigalzu, from Dūr-Kurigalzu to Sippar-ša-Šamas and Sippar-ša-Anunnītu (?), (the land of) the Arameans.

This geographical extent might be measured against the achievements of Adad-nārārī II (see also Zadok 2008: 322–23): The Synchronistic Chronicle reports the setting of the border at Til-Bāri at the close of Adad-nārārī II’s reign, this lasting until the time of Salmānu-ašarēd III’s intervention, and hence there is no change.[17] The mention of Ḫatti (northern Syria) does intimate Tukultī-Ninurta II’s penetration farther westwards than his predecessor, and the inclusion of the passes between Habrûri (Ḥerīr plain, Iraq) and Gilzānu (’Urūmīye basin, Iran) and the taking of Ḫubuškia (vicinity of Pirānšahr, Iran) and its king (in the Ninūa text) is novel. The mention in his geographical summary of the pass of Ḫašmar (region of Darband-i Ḫān, Iraq), in contrast to Adad-nārārī II venturing to Namri (western Kermānšāh Province, Iran), is difficult to qualify without more information.[18] It does, nonetheless, intimate that Tukultī-Ninurta II undertook at least one campaign across Zamūa (Šahr-i Zūr plain, Iraq).

Moreover his ‘conquest’ extending to Dūr-Kurigalzu and Sippar was merely the defeat of the Aramean tribes of the Itu’u on the Wādī aṯ-Ṯarṯār (see RIMA.0.100.5 49–50) on the way to Sūḫu. The inscription does note campaigning to Lāqê (Dayr az-Zūr District, Syria), Sūḫu, and Na’iri (all within the orbit of his father’s achievements), and places the most emphasis upon the lattermost region, as his summary is presaged with the epithet kāšid (mātāt) Na’iri ‘victor over the lands of Na’iri’, perhaps echoing Adad-nārārī II’s epithet as kāšid (māt) Karduniaš. All of this presents a relatively scant list of accomplishments for the first half of the Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign, which can be contextualised as follows (Table 5):

A summary of the hitherto-known events of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign and their sources.

| Date | Event | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 890 | Earlier | Accession of TN II | RIMA.0.100.1 28 |

| Later | Completion of wall at Baltil (Aššur) | RIMA.0.100.2 rev. 1’–12’ | |

| 890–887 | Campaign to border of Ḫatti. Defeat and capture of Apâ of Ḫubuškia | RIMA.0.100.6; Qaḍīya 1–3 | |

| Late 887 | Conclusion of a campaign to Na’iri and Kāšiāru, TN II returns to Aššur | RIMA.0.100.5 1–3 | |

| Late 887 or very early 886 | Aftermath of the prior campaign, Bīt-Zamāni undertakes campaign, forwards tribute and hostages | RIMA.0.100.5 4–8 | |

| Early 886 | Rebellion of a ‘principal he’ in piedmont and defeat | RIMA.0.100.5 9–10 | |

| 1st Simānu (III) 886 | Campaign to Bīt-Zamāni. Imposition of horse-trading deal and supervision by Assyrian officials | RIMA.0.100.5 11–29; KAL 3: 21 obv.? 2’–5’ | |

| 17th Tašrītu (VII) 886 | Campaign beyond Ḫabrûri to Ladānu (western Zamūa) | RIMA.0.100.5 30–40 | |

| 26th Nisannu (I) 885 | March to Babylonia, defeat of nomads in the Wādī aṯ-Ṯarṯār, tribute of Sūḫu, Lāqê, and Lower Ḫābūr | RIMA.0.100.5 41–126 | |

| Prior to 9th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 885 | A single broken line refers to another (presumably unimportant) campaign | RIMA.0.100.5 127 | |

| 9th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 885a | Completion of renovation of palace terrace at Aššur | RIMA.0.100.5 136–46; cf RIMA.0.100.3 rev. 7’–17’ | |

| 884 | TN II dies, his new palace at Nēmed-Tukultī-Ninurta remains unfinished | Cf. RIMA.0.100.6 | |

-

aIt is likely that RIMA.0.100.3 rev. 7’–17’ refers to precisely the same event; as the eponym date is Na’idi-ilu, governor of Katmuḫi, in RIMA.0.100.5 147, it is striking that an epigraph or colophon (?) on the edge of RIMA.0.100.3 reads ]-ḫa-a-ú. Although the use of ú is peculiar, this could stand for Katmuḫāyu ‘the Katmuḫian’. Alternatively, this could stand for an Aramaic name such as Idrī-aḫā’u (often written with a final -ú) and conceivably be a byname for Na’idi-ilu or even the following eponym, Iarî (whose obscure name is a hypochoristicon), although there would be no etymological link evident between names in either case.

Here, the historian’s task is to establish the events and internal chronology of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s regnal years prior to late 887. While the scarceness of achievements by his reign’s close implies that they were consolidatory in nature, this would provide vital information as to the state of Assyria’s much expanded realm in the wake of Adad-nārārī II’s conquests, and whether much resistance to Assyrian rule existed prior to his successor’s reign. Before the five unattributed texts might be considered, it is germane to consider the reigns surrounding this period, namely those of Aššur-dān II (934–912) and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II (883–859).

4 Framing the Era – The Reigns of Aššur-dān II and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II

The reigns of Aššur-dān II and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II could not seem more different. Where the first struggled to keep rampant nomads from Aššur’s gates, the latter could march to the Mediterranean, construct a new capital at Kalḫu (Nimrūd, Iraq) and invite emissaries from the nations surrounding the Neo-Assyrian kingdom to a giant spectacle at its inauguration. Despite this, the inscriptions to be discussed could ostensibly belong to the reigns of either king upon initial inspection of their language, script, or content.

Aššur-dān II’s reign lasted more than two decades, and yet only some seven undated and geographically limited campaigns are recorded within his inscriptions. The first three imply that Assyria was territorially reduced to its heartland (RIMA.0.98.1 6–32), while the latter demonstrate minor chevauchées and the reimposition of vassal arrangements on neighbours. While it could be argued that RIMA.0.98.1 (Aššur-dān II’s only extended annalistic text) hails from early in his reign as its eponym remains unattributed, this is contradicted by the large numbers of animals mentioned within his hunting tally (see discussion of tallies below in respect to KAL 3: 48), including some 120 lions, 1600 wild bulls, and 56 elephants (RIMA.0.98.1 68–72) which must have taken considerable time to accumulate, implying a date well into his reign. Constrained by his own kingdom’s weakness, it may well be that Aššur-dān II employed such hunting as a propagandistic pastime in lieu of campaigning. Regardless, none of the unattributed texts discussed here are compatible with what is known of his reign, and need not be further factored into the coming analysis.[19]

Akin to the end of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign, the opening of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s reign is very well documented, providing consecutive annalistic accounts running to roughly 877. While this leaves another 18 regnal years in which only Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s much-lauded ‘march to the sea’ and an abortive campaign to Amēdu 866 are annalistically extant, his various geographical summary inscriptions, the depictions on his gates from Imgur-Enlil (Balāwāt, Iraq), the literary text LKA 64, and the events of his successor Salmānu-ašarēd III’s early reign are sufficient to infer an historical framework.[20] During this period, Aššur-nāṣir-apli II would become embroiled in wars with Bīt-Adini (the plains between Şanlıurfa, Turkey, and the Euphrates) and later Urarṭu (northern Zagros), the exigencies of which would seemed to have well surpassed anything presented in the five inscriptions examined here. Indeed, the latter part of his reign seems to have been preoccupied with the shoring up of Assyria’s defences by diplomatic means, with the polities of Bīt-Zamāni and Bīt-Baḫiāni (Balīḫ basin, Turkey and Syria) being incorporated into the Assyrian realm as ‘transitional cases’ with their local rulers as governors (Edmonds 2021). One might further note the ‘international event’ that was his inauguration of his capital at Kalḫu (RIMA.0.101.30), the emphasis upon tribute in visual sources, or indeed reconciliatory depictions on palatial reliefs (Portuese 2017). He may well have become a better statesman than warrior by this period. Nonetheless, the window between 877 and 866 cannot be entirely discounted for the events of the texts herein studied, and will be reckoned with in the analysis. In the present author’s own mind, the many obelisk fragments found at Naynawā by Thompson and now spread between Birmingham, London, and Baġdād depicting the tribute of various peoples (see Reade 2005: 374) are probably to be attributed to this latter era of the reign of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, not only as what scant phraseology and names which might be securely read correspond to events from his reign,[21] but also because comparable fragments of an obelisk of his reign are now known from Aššur, and there is presently no evidence of any king between Aššur-nāṣir-apli I[22] and himself having created such a monument: Indeed, the pattern emerging rather places all dateable Assyrian obelisks and obelisk fragments in the reigns of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I, Aššur-nāṣir-apli I, Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, Salmānu-ašarēd III, and Adad-nārārī III respectively.[23] Three of these four obelisk-makers are known to have visited the shores of the Mediterranean and washed their weapons there, which may well be meaningful; perhaps Aššur-nāṣir-apli I made it further west than what little remains of his inscriptions intimates.[24] With this, the first unattributed inscription might be considered.

4.1 KAL 3: 48. Adad-nārārī II’s Accession, Campaign to Ušḫu and Atkun, and Conquest of Qumānû (911 BC) and an Early March to the Euphrates

This fragment begins with a singular description of the intended audience of royal inscriptions (obv. i 1’–5’), then mentions the sovereign’s accession and early conquests. These are the northern Zagrine polities of Ušḫu and Atkun (obv. i 6’–11’), and, in the next section, Qumānû including its capital Kipšūnu (obv. i 12’–13’). A further broken column (obv ii.) provides little diagnostic beyond a mention of gold (3’) and an i+na below a ruling which must point to the beginning of a dated campaign (6’). On the other side ([rev.] iv 1’), a broken description of hunting ensues ([rev.] iv 1’–14’). Frahm (2009b: 100) tended towards Adad-nārārī II, but did not exclude any other early Neo-Assyrian king, particularly Aššur-nāṣir-apli II.

The first point is that the events occurred in a king’s accession year. Here, it should be noted that Adad-nārārī II campaigned to Qumānû following his accession according to RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 10–19, and that Aššur-nāṣir-apli II campaigned to Ušḫu and Atkun in his first regnal year (RIMA.0.101.1 i 69–73; 17 i 90–93, albeit as his second campaign), while the beginning of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign is not preserved. While this mention of Ušḫu and Atkun would favour Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, it is clear from the description of mustering in KAL 3: obv. i. 6’–9’ that this was the king’s very first campaign, rendering the omission of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s 882 campaign to Ništun (RIMA.0.101.1 i 45–69; 17 i 65–95) implausible.

The next factor to be considered is Qumānû; Adad-nārārī II’s inscriptions explicitly commemorate its defeat early in his reign both in the geographical summaries and in a damaged account from his 909-annals (RIMA.0.99.1 10–19). In turn, Qumānû is remarkably absent from the royal inscriptions of subsequent Assyrian kings; it would be very strange that the defeat of a kingdom described as “expansive” (RIMA.0.99.2 24; KAL 3: 16–17 15’–16’) would have escaped scribes’ notice or have been redacted. Moreover, KAL 3: 48’s campaign initiates without casus belli; were this event to have occurred in a subsequent reign, then mention of Qumānû’s insubordination would be expected to presage the narrative. Rather, this mirrors the apparently unprovoked conquest of RIMA.0.99.1 and implies that this was the first time that a Neo-Assyrian king had subdued this kingdom.[25]

All of these points, along with Frahm’s (2009b: 100–01) observation of the very close phraseology between the hunting reports of KAL 3; 48 (rev.) iv 1’–14’ and RIMA.0.99.2 122–26 (particularly the hunting of elephants with traps) render an ascription to Adad-nārārī II certain.[26] Nonetheless, a few issues require resolution. The first of these is the differing information of the defeat of Qumānû presented in these two accounts, summarised in the following table (Table 6):

Differing accounts of the defeat of Qumānû.

| KAL 3: 48 obv. i 12’–16’ | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 10–19 |

|---|---|

| [ina līt kiš]šūtīya šūturte ana (māt) Qumēnî [(…) allik(?) … K]ipšūna šapliš [… ]-na ālāni [… i]kšudu/ū [… biltu madattu(?) elīšun]u ukīn […] |

ina qibit Aššur bēli rabê bēlīya narkabāti ṣābīya adki ana (māt) Qumānê lū allik rapšāti Qumānê lū akšud Ilūya šar (māt) Qumānê ina qabal ekallīšu qātī lū ikšussu aḫḫēšu ana gurunni lū amḫaṣ dīktīšunu ma’attu iddâk šallassunu būšīšunu makkūrīšunu alpīšunu immer ṣēnīšunu ana ālīya Aššur ubla ilānīšunu kī qīšūte ana Aššur bēlīya iqīš

sitāt ummānīšunu [ša ištu] pān kakkīya ipparšid[ūni] iturūni šubtu nēḫtu [ušēšibšunu …] |

| In the power of my overwhelming authority, [… I went (?)] to the land of Qumēnû [… K]ipšūna below […] cities [… th]ey/he took […] I imposed o[n them tribute (?)… ] | At the command of the great lord Aššur, my lord, I mustered my chariotry and troops. I went forth to the land of Qumānû. I took expansive Qumānû. I captured Ilūya, king of Qumānû, in the midst of his palace. I slew his brothers in heaps. I struck them a great blow. I brought their spoils, possessions, and property, their oxen, sheep, and livestock to my city Aššur. I bestowed them upon Aššur, my lord, as gifts. I settled in peaceful dwellings the remaining troops who had fled before my weapons and had since returned […] |

Although differences are apparent, both narratives are also incomplete: While only the end of RIMA.0.99.1’s version is lost, the vast majority of KAL 3: 48’s account has suffered this fate. What survives can, nonetheless, be reconciled. From the ‘die’ of Aya-ḫālu (formerly ‘Yaḫālu’), masennu rabû to Salmānu-ašarēd III, it is apparent that Kipšūnu was the capital of Qumānû;[27] hence, the capture of Ilūya “in his palace” in RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 12–13 must have occurred there. In turn, RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 14–19 describes collection of spoils and of the resettlement of returning Qumānû soldiers before breaking off. It is logical that the next topic would have been the imposition of tribute and vassalage, as probably preserved in KAL 3: 48, and that the intervening portion was abridged in the latter account. Finally, KAL 3: 48 appears to be more thematically focused on military expeditions, while RIMA.0.99.1 focuses more on aftermaths. Here, the emphasis in RIMA.0.99.1 on the transporting of spoils to Aššur and their dedication to the eponymous god (found after each campaign described) are key, as this text was composed to commemorate the renovation of the quay at Aššur.[28] KAL 3: 48 may well thus represent a more ‘military historical’ annalistic account.[29]

This leads to the next point, the omission of Ušḫu and Atkun from RIMA.0.99.1. One possibility is that the defeat of these hardy mountain communities did not yield any spoils with which to return to Aššur (thus disqualifying it from mention in the text). Another point is the apparent insignificance and banality of conquering these settlements (KAL 3: 48 devotes only two lines to the conquest); the mountainous flank of Nibur and Paṣâte in which they lay (Cudi Dağı, Turkey, and environs) has remained ungovernable throughout history, providing an eternal casus expeditionis. Both Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s unhurried conquest of the area on the way to Katmuḫi in his first year and Sîn-aḫḫē-erība’s extensive hiking and creation of rock reliefs following a perfunctory battle at Nibur (see Finkel 2014: 291–92) recall Fuchs’ suggestion that new kings would often choose the foothills of the Zagros as ‘soft’ targets with which to gain military experience (and an easy victory with which to return home).[30] Indeed, Aššur-bēl-kala had previously marched to exactly the same area with similarly bland results near the beginning of his reign, and had it recorded in a ruled section of two lines (RIMA.0.89.1 12’–13’).[31] While an exhaustive annalistic account might list this conquest, this would be the first achievement to be edited out of a king’s res gestae, particularly as the subsequent defeat of the nearby kingdom of Qumānû dwarfed it in scope.[32]

Mention of elephants, ostriches, and perhaps bitumen in the hunting section implies that this text must have been compiled following Adad-nārārī II’s earliest campaign to Sūḫu and the Middle Euphrates. This text’s broken state is hence particularly frustrating as it must have been an early recension of the king’s annals (particularly considering its retention of the episode of Ušḫu and Atkun); the text mentions him only having caught a single elephant in a kippu-snare (KAL 3: 48 [rev.] iv 3’), not the five which he would bag in such a manner by 893 (RIMA.0.99.2 125). This comparison of hunting reports does, nonetheless, demonstrate an interesting point – early Neo-Assyrian hunting reports were evidently running game tallies to which scribes would add following each royal hunting excursion and immortalise as such in the next royal inscription, perhaps as an encouragement for kings to reach ‘high scores’.[33]

4.2 KAL 3: 47. Adad-nārārī II’s Early Na’iri Campaigning and the Conquest of Katmuḫi (ca. 909–902 BC)

This short and broken text begins with the fragmentary tail-end of a campaign (ll. 1’–7’) describing the plundering and harrowing of a region in either the Upper Tigris or Zagros (on account of a ‘barbarian they’ and horses as spoils), following what would appear to be a dawn attack in which a fragmentary KUR s[u-can be recognised (l. 3’). Thereafter, underneath a ruling, may be found two broken lines which appear to relate to a second campaign on 28th Kislīmu (IX) of an unknown eponymate (ll. 8’–9’). After these, underneath yet another ruling, are the scarce fragments of another narrative (ll. 10’–15’), within which an URU-sign (11’) and a LUGAL-sign (14’, see comm.) are recognisable.[34] Beneath this lies what would seem to be yet another ruling, presumably signalling another sequence (evident on the copy, albeit not in Frahm’s score), and likely the top of an ITI-sign,[35] and thus the date of another campaign.

On grounds of the format of the dates and some phraseology, Frahm (2009b: 98) suspected that this text hailed from the reign of Adad-nārārī II. This is particularly interesting considering the sign-forms and rulings found in KAL 3: 53 (see below) are close enough to those here that they might hail from the same text. As he further notes, the expression ana šanûtēšu “for the second time” (l. 9’) is paralleled in the passage of Adad-nārārī II’s second campaign to Kumme (RIMA.0.99.2 94). Indeed, Adad-nārārī II’s inscriptions quite exceptionally rationalise campaigns into numbered campaigns within discrete regions, i.e. seven campaigns to Ḫanigalbat, two campaigns to Kumme, and four campaigns to Na’iri.[36] Hence, Adad-nārārī II’s Supertigridian expeditionary foursome is by far the most fitting historical context for the KAL 3: 47’s first (ll. 1’–7’) and second (ll. 8’–9’) sections.[37] A further point to be made is that the campaign “for a second time” is at the remarkably late date of 28th Kislīmu (IX); the only early Neo-Assyrian king to campaign so far into a mountainous region in winter was Adad-nārārī II, who marched to Ḫabḫu (3) and Meḫru on 4th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 909. This king’s remarkable energy in his initial regnal years would support an ascription of this campaign to his early reign.

Following from these conclusions, KUR s[u-probably refers to Suḫme, a polity on the Upper Tigris;[38] while this land is not mentioned in the summary, the neighbouring country of Alzi (Elaziğ Province, Turkey) is, rendering this plausible. It is noteworthy that dawn attacks (ina/lām Šamaš napāḫi ‘at/before daybreak’) are only attested four other times within the corpus of Assyrian royal inscriptions, once by Aššur-nāṣir-apli I in the Kāšiāru mountains’ (modern Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn, Turkey) northern fringe (RIMA.0.101.18 26’–27’, see above, n. 24 for ascription), and thrice by Aššur-nāṣir-apli II. The latter used this tactic once in the Upper Tigris against the Dirru-people (RIMA.0.101.1 ii 106; 17 iv 71; 19 73), and twice in Zamūa, once against Nūr-Adad of Dagara (RIMA.0.101.1 ii 48–49) and once when attacking the city of Ammali (RIMA.0.101.1 ii 53–54). This seems to have been a common Assyrian tactic intended to catch mountain-dwellers before they fled to inaccessible terrain.

The next and most striking point is the reference to a king. By the early Neo-Assyrian period, it was unusual for royal inscriptions to refer to foreign rulers as šarru, which permits inference of the land discussed; to the present author’s knowledge, only the rulers of Karduniaš, Katmuḫi, Gargamis (Ǧarābulus, Syro-Turkish border), Gilzānu, Dayaeni (mountains north of the Upper Tigris plain, Turkey), Naṣībīna (Nusaybin, Turkey), and Ḫubuškia are accorded this title. With the exception of Naṣībīna and possibly Ḫubuškia (of which nothing is attested prior to the reign of Tukultī-Ninurta II) the roots of each of these kingships stretch back into the second millennium. Considering the geographical remits of his activities, only two king(dom)s are plausible for Adad-nārārī II to have defeated prior to 901, namely Karduniaš and Katmuḫi. Considering the brevity of this account, it is unlikely to reflect the former, which already receives considerable shrift in the summary inscriptions and was obviously a signal achievement – by means of contrast, the narrative here receives scarcely five lines despite containing a king! Rather, the natural candidate is Katmuḫi, which was unceremoniously annexed to Assyria early in his reign (RIMA.0.99.2 26), albeit remaining a ‘transitional case’ well into Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s days. Aššur-dān II had deposed its previous king Kundibḫalê, and its shaky vassalage may have proven an impediment to an Assyria bent on campaigning in the Upper Tigris. Hence, it might be inferred that Adad-nārārī II’s conquest of Katmuḫi followed his second Na’iri campaign.

What is striking about this event, however, is that despite the ruling demonstrating that this is a new narrative, no precise date is given; by means of comparison, the sign ITI may be noted at the same position beneath a ruling on ll. 8’ and 15’ above and below this ruled section. Deviation from the usual dating formulae is known from Adad-nārārī II’s inscriptions, and is used to announce a further campaign in the same eponymate. As there does not seem to be enough space for a description of mustering troops or of a march from Assyria before a city is mentioned, the conclusion must be that this occurred immediately following the second Na’iri campaign. Considering the stark brevity of the second campaign, it may well have proven fruitless, and a defeat of Katmuḫi was necessary to return with glory and fulfil the Assyrian army’s rapine ambitions.[39]

4.3 KAL 3: 53. A Late Na’iri Campaign of Adad-nārārī II, his Defeat of the Aḫlamû, and a Harrying of the Middle Euphrates (ca. 909–902 BC)

Left unassigned by Frahm (2009b: 104–05), this text is noted by him to be of very similar ductus to KAL 3: 47. He suggests that it may in fact be from the same text, and, indeed the format, especially the rulings, supports this. If this is the case, then it must evidently hail from elsewhere in this same text; neither overlap nor direct join may be detected, and he notes, in turn, that the height of the lines in KAL 3: 53 does not precisely correspond to that of KAL 3: 47. Regardless, should the ductus be so arrestingly similar, then this text could well have been written out by the same scribe, and have been commissioned contemporaneously with KAL 3: 47.

The first preserved section is the fragmentary tail-end of a campaign to Na’iri mentioning harvesting, troops, the crossing of mountains[40] and the plundering of Usia, an otherwise unknown city likely in the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn.[41] The second (and very brief) ruled section (ll. 7’–8’) retains only the second halves of two lines: [… dīktī]šunu ma’attu adūk [… A]rrapḫi ušaṣ[bit?] “[…I mas]sacred them in droves [ … ] I settled them in Arrapḫa”; the use of the ‘barbarian they’ points to the Assyrian ruler’s foe here being either a mountaineer or nomadic group. The third section (ll. 9’–13’) evidences only a scarce few broken lines mentioning bronze and iron, perhaps the Euphrates, and harvesting.

While this seems little to go on, there are some diagnostic points. Firstly, as noted by Frahm, the verb eṣēdu is a rarity and only attested for Adad-nārārī II and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, as is also the case for dīktu ma’attu dâku. More vitally, Arrapḫa had been conquered early in Adad-nārārī II’s reign, and is not mentioned in the annals of any other king. Not only would the resettlement of a nomadic population there make particularly good sense if this was a relatively fresh conquest and Arrapḫa was undergoing restructuring,[42] but also narratologically inasmuch as the precise destinations of deportees are not generally provided in early Neo-Assyrian inscriptions: the Arrapḫa reference would thus refer back to an earlier conquest within the same composition, and hence to Adad-nārārī II’s reign. Perhaps the most suggestive argument, however, is the orthographic similarity to KAL 3: 47, which seems very likely to describe Adad-nārārī II’s deeds.

If such an ascription is pursued, then the events mentioned tally nicely with the early events of this king’s reign. The terse defeat of a ‘barbarian they’ in the second section and their subsequent settlement in Arrapḫa would accord extremely well with a mention by Adad-nārārī II in his summary that he defeated the Aḫlamû during the pre-Apku period.[43] In turn, the final section’s mention of not only bronze, but also iron (indicative of the Upper Tigris, the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn, or the Middle Euphrates) and probably of the Euphrates alongside eṣēdu could point very nicely to Adad-nārārī II’s early exploits in the latter region, as prior to 901 he must have received Sūḫu’s tribute and have harried Lāqê (thus justifying his epithet of dā’iš Lāqê on the Tall ‘Ašāra Stele), albeit not necessarily simultaneously; it might be imagined that he brought the crops to the neighbouring allied Assyrian bulwark of Dūr-Katlimmu (Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad, Syria) which he would claim outright as his own come 885 (RIMA.0.99.2 111–12). Finally, the first section’s mention of the lands of Na’iri seemingly in their entirety,[44] of harvesting, and of plunder of a city in the Kāšiāru on the return march all point to the successful conclusion of a period of concerted campaigning in the Upper Tigris and the establishment of supremacy there, perhaps with the bolstering of an outpost with the harvested crops (the obvious candidate for this early period being Damdammusa). It is hence reasonable to propose that this marked the last of his four Na’iri Campaigns.

4.4 KAL 3: 45–46. Some campaigns of Tukultī-Ninurta II to Nirdun and Na’iri Featuring a Rock Inscription, and his Defeat of Irbibu and a Superchaburine Insurrection (ca. 890–887 BC)

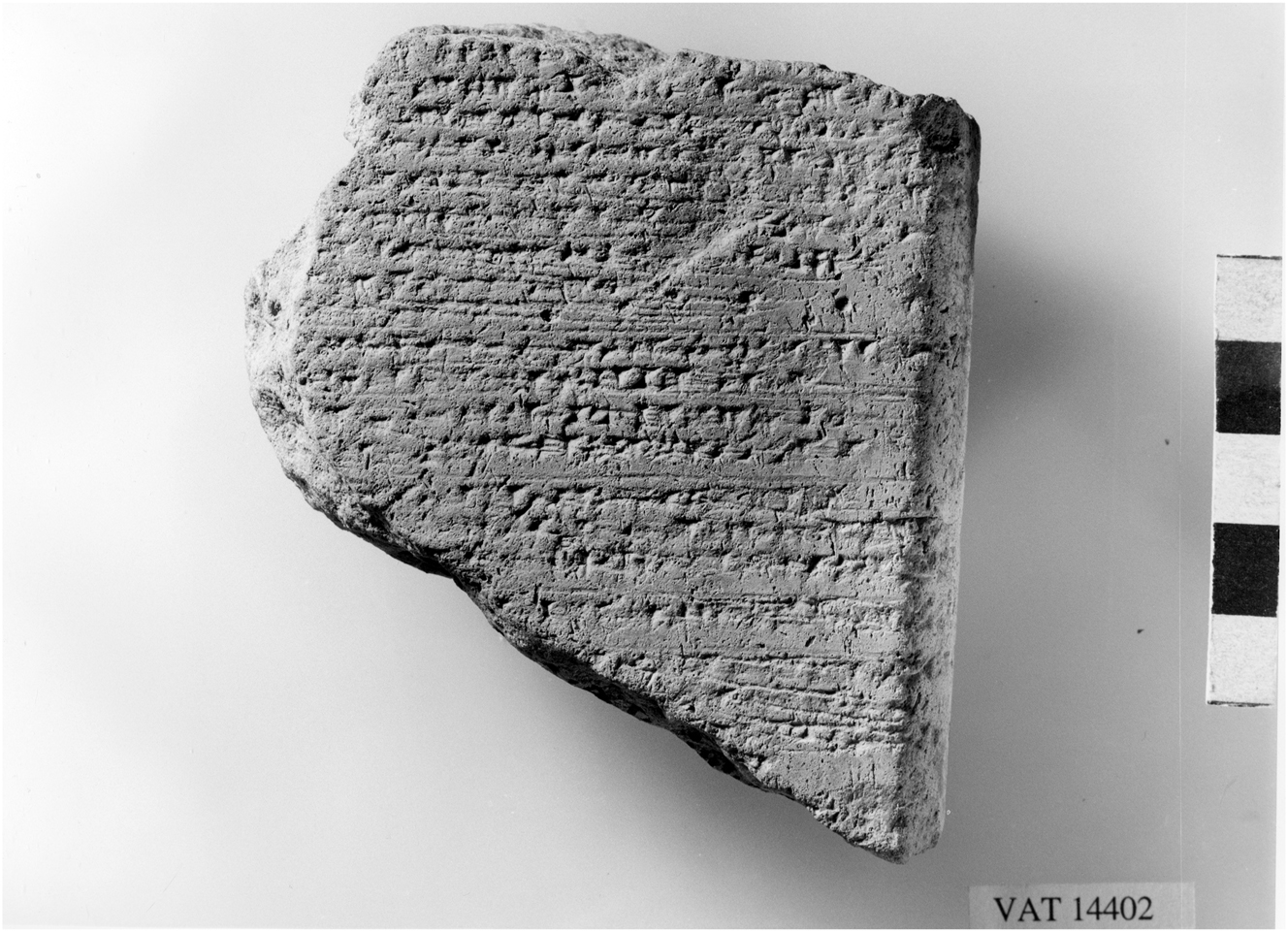

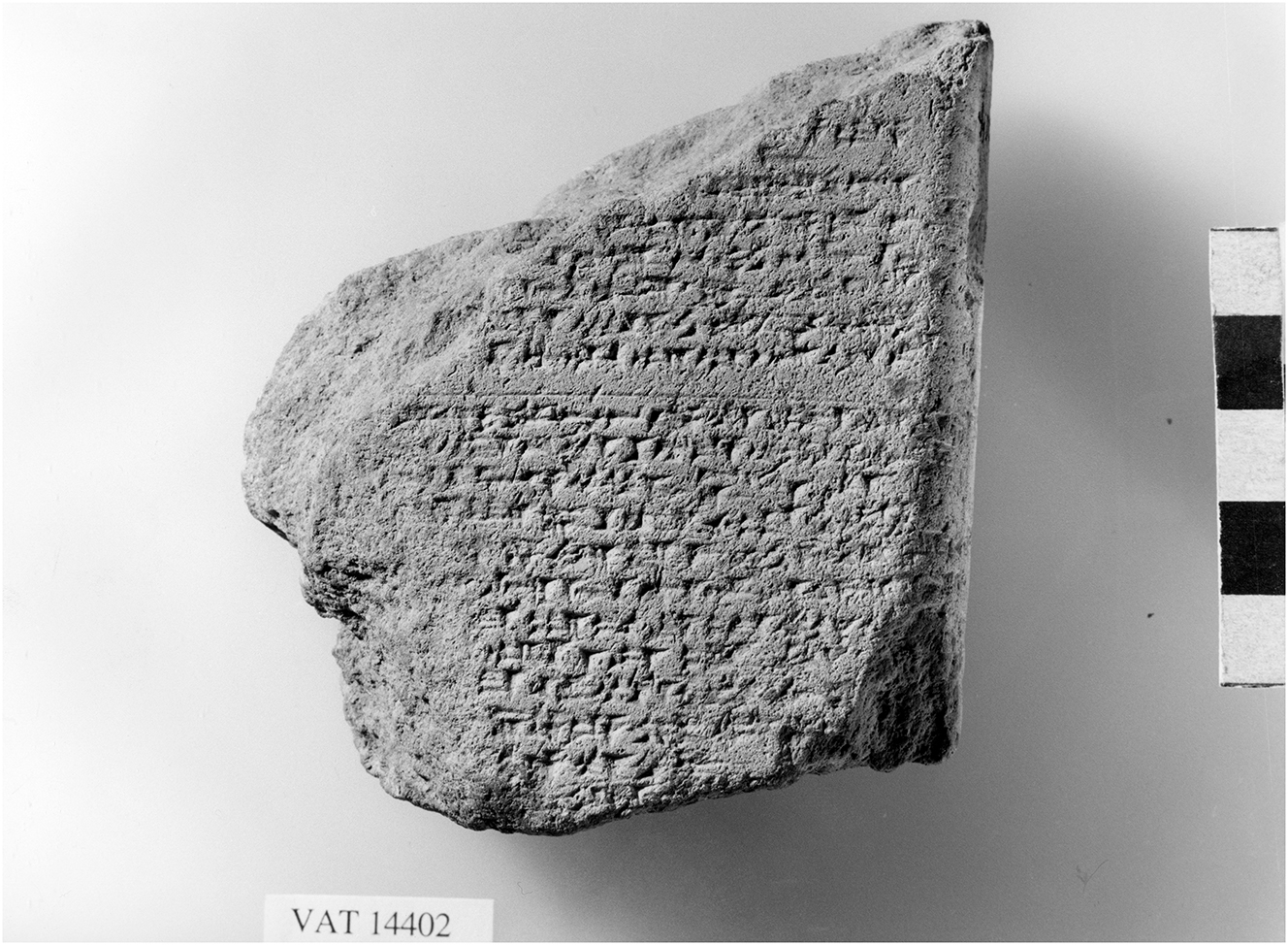

Unlike the other texts presented here, KAL 3: 45–46 possesses a long history of publication and interpretation. It consists of two exemplars, A (= VAT 9752) and B (VAT 9782+10944). B was first published by Schroeder (1922) as KAH 87 and 88, who suggested that it might date to the reign of Adad-nārārī II (108), a view tentatively followed by Luckenbill (1926: 124–25). By means of contrast, Seidmann (1935: 7) and Grayson (1991: 265–67) tended towards Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, while Schramm (1973: 7–8) also did not exclude Aššur-dān II and Tukultī-Ninurta II from consideration. In scholarly literature, A was known to duplicate VAT 9782, but was first published by Grayson (1991), who presented an edition of VAT 9752 and 9782 together as RIMA.0.101.21, but did not recognise that VAT 9782 joins with 10944; he published the latter separately as RIMA.0.101.22. As a result, it is only come Frahm’s edition that the text could be historically analysed in its fully preserved extent.

In his edition, Frahm (2009b: 92–97) notes the similarities in phraseology between this text and KAL 3: 56. This text is divided into a series of ruled passages. In the first section (ll. 1’–6’), the military of a ‘barbarian they’ is defeated and brought down into the lowlands, their livestock plundered, and slain in droves, including the amputation of hands and blinding. The land in which this happens must be a pastoral highland polity, probably Nirdun (Savur Çayı basin, Turkey).[45]

In the next and best-preserved section (ll. 7’–16’), Irbibu, a lord on the Upper Ḫābūr, refuses to pay tribute and has fortified his city with a moat. The Assyrian king lays siege to him with a series of encircling forts and marches down the Ḫarmiš River (Wādī al-Ǧaġǧaġ, Syria) plundering adjacent settlements, after which he takes the nearby fortified city of Malḫāni.[46] The king butchers 174 men, flays 12, blinds and amputates the tongues of an unknown number, cuts the throats of 153, and impales 21 particular individuals associated with Irbibu.

In a briefer section (17’–18’), Barzania and Dikun and their surrounding region are attacked by the Assyrian king and plundered. Thereafter, in a new ruled section (ll. 19’–25’) which is quite broken, a rock relief of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I is mentioned, and a mountain range is crossed to reach Na’iri. There, Barzania is attacked once more, its livestock plundered, and enemy soldiers beheaded and the area generally ravaged.

Finally, in lines 26’–31’, the city of Tillê (likely Tall Rumaylān, Syria) rebels and moves forces to Kaḫat (Tall Barrī, Syria) and another city, the name of which is lost. The Assyrian king marches forth and defeats the insurrectionists, looting their livestock and bringing prisoners back to Assyria.

Certainly, there is a wealth of information which excludes both Aššur-nāṣir-apli II and Adad-nārārī II from consideration. Tillê belonged to Katmuḫi (İdil plain, Turkey), which was conquered and incorporated into Assyria’s pale early in Adad-nārārī II’s reign (although it enjoyed something of a ‘transitional status’ well into Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s time), providing a terminus post quem. Nonetheless, a reasonable, if not certain terminus ante quem is furnished by Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s consecration of a palace there in 879 following some hunting about the region, which bespeaks a solidified Assyrian presence (RIMA.0.101.19 32–35). While a subsequent rebellion cannot be discounted (and Tillê would be the centre of such in the years 818–817), other historical indications support a window prior to Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s reign.

Key here is Irbibu’s rebellion on the River Ḫarmiš, which bespeaks a transitional situation in the Upper Ḫābūr; that such a state of affairs would have persisted as late as Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s reign is not impossible, but should the city of Malḫāni have been involved in the Irbibu insurrection as the traces suggest, then Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s nonchalant jaunt past there in 879 would again place this text’s events earlier. As noted, the siege technique of encirclement with towers mirrors that employed in KAL 3: 56.

In turn, as noted by Frahm, it is not insignificant that the only Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions presently recovered from Kaḫat were commissioned by Tukultī-Ninurta II for the construction of a palace there (RIMA.0.100.9). It could be imagined that this occurred in response to the uprising mentioned here (26’–31’) as a means of reinforcing Assyria’s presence.

Although the polity of Nirdun is first explicitly attested in the reign of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, it is only depicted as rendering tribute; considering that it occupied the region around the Savur Çayı, the chief entrance to the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn massif from the north, Assyria must have clashed with it prior to his reign. Here, it should be noted that its fortified settlement of Uda was already a target during the reign of Tukultī-Ninurta II, with Bialasi of Bīt-Zamāni campaigning there on Assyria’s behalf in late 877 (RIMA.0.100.5 6). As this was a follow-up to a prior Assyrian campaign, Nirdun must have endured the “wolf on the fold” prior to then, earlier in the same year at the very latest.

Next, the impalement must be considered; the history and terminology of this practice remains complicated, with Radner (2015) drawing a distinction between impalement upon a stake (zaqīpu) and the post-mortem hanging of a body from a post (gašīšu), the former during sieges and the latter in the aftermath. The scarcity of attestations precludes the drawing of many more inferences, but it might be noted that Aššur-bēl-kala’s annals are the first to describe the displaying of a body from a post by an Assyrian (RIMA.0.89.2 iii 12’). In turn, the first attestation of impalement proper (i.e. ana zaqīpi zuqqupu) hails from Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s first regnal year (882) following Aḫi-yababa’s aforementioned usurpation at Sūru of Bīt-Ḫalupê, with further examples occurring at Pitura (879), and Amēdu and Udu (866), these latter three in the Upper Tigris.[47] In this initial impaling on the Euphrates, however, Aššur-nāṣir-apli II created an elaborate tower with impaled bodies both atop and around its structure clad with flayed skins. Unless he was a punitive prodigy, the complicatedness of this cruel edifice implies that Aššur-nāṣir-apli II did not originate this practice, but rather that it already belonged to the Assyrian ruler’s ‘frightfulness-toolkit’ by his time, and that his tower of pain had simply elaborated on earlier practices.[48] In such a respect, it might be noted that his annals call his father Tukultī-Ninurta II ša kullat zā’irīšu inerrūma ina gašīši urettû pagrī gērīšu “he who defeated all of his enemies and fixed his foes’ corpses to posts”. Combined with the excruciating torture which will further be noted in KAL 3: 56 (see below), a somewhat dark image of Tukultī-Ninurta II emerges: might he have been the innovator of this brutality?

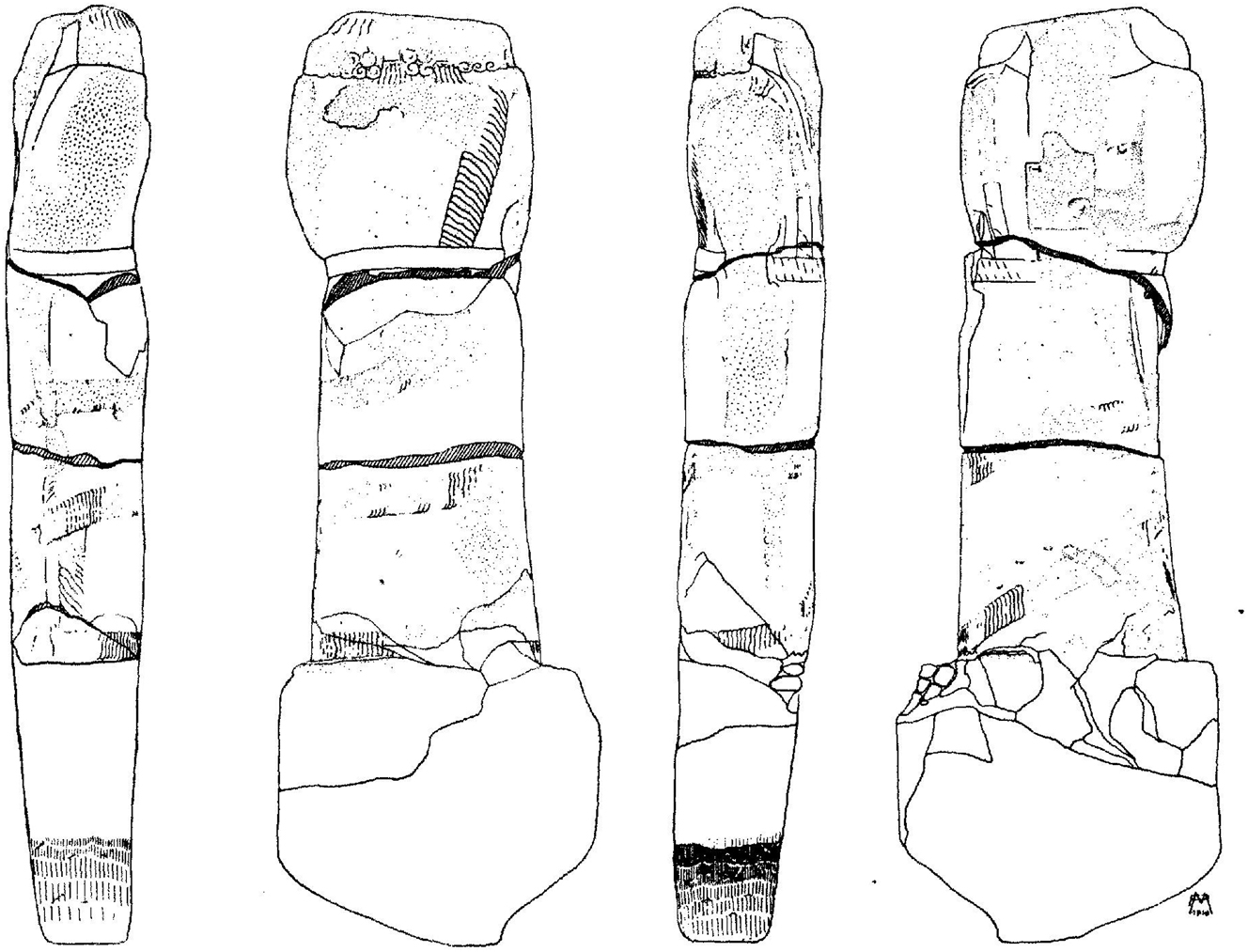

Turning to Barzania (which very likely corresponds to Barzaništun [see Bagg 2017: 97–98]), this polity was reached via Mount Amadānu (either the Maden Dağları or the Karacadağ, Turkey), as is evident from the itinerary of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s 866 campaign to Amēdu (RIMA.0.101.1 iii 104). It is fascinating to note that the second march there as described in the present text involves the visiting of a rock inscription of Tukultī-apil-ešarra I. As previously discussed, Tukultī-Ninurta II seems to have been the first Neo-Assyrian king to have left rock inscriptions, a pursuit eagerly followed by his son and grandson. Indeed, a recently identified group of three Assyrian rock inscriptions near the village of Yağmur in the western flank of the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn could correspond to the site mentioned in this text, with one of these (Panel 1) clearly from the reign of Tukultī-apil-ešarra I, and two other fragmentary examples (Panels 2 and 3) which must be early Neo-Assyrian in date (Genç and MacGinnis 2023). It is the present author’s opinion that one of the unattributed examples must be from Tukultī-Ninurta II, and that the king left an inscription here on the way to Barzania/Barzaništun, as the fragmentary passage here intimates.[49] Indeed, it is possible that he initially encountered the relief on his first campaign to Barzania and returned to ‘discover’ the inscription and carve his own companion piece immediately afterwards. Certainly, it makes little sense for an Assyrian army to raid the same distant, pastoral mountain polity twice in a row, and an ulterior motive might be assumed.[50]

Hence, taken together, these references render an ascription of this text to Tukultī-Ninurta II as certain, particularly in light of KAL 3: 56. This is further epigraphically supported by Frahm’s note (2009: 95) that idiosyncratic writings of the sign NA in this text only otherwise occur in inscriptions from Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign. Together with the activities of KAL 3: 56 (see below), it can be presumed that much of the early years of his reign is now covered by these two texts. The internal chronology of these events will be considered in the latter section.

4.5 KAL 3: 56. Tukultī-Ninurta II’s Early Campaigns along with his Later Flaying of Apâ of Ḫubuškia and Punishment of Naṣībīna (ca. 890–887 BC)

Frahm (2009b: 108–11) considered KAL 3: 56 to present very striking similarities with KAL 3: 45–46 in phraseology, although (as he further notes) the most remarkable congruence is their exceptionally elaborate and minute descriptions of torture. He thus contended that both texts must hail from the same ruler’s reign. Having noted historical incongruities with an attribution to Adad-nārārī II and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, he ultimately arrived at a very tentative ascription to Tukultī-Ninurta II.

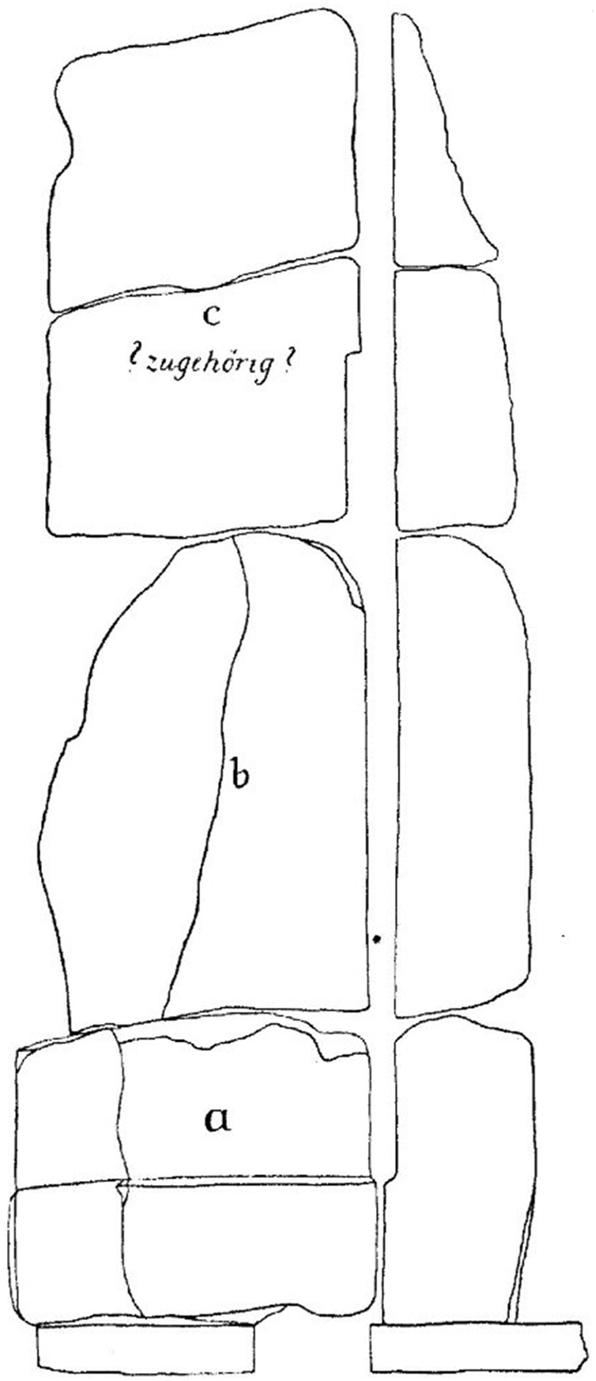

Side a. (probably obv.) is extremely fragmentary, with probably six different ruled sections (Figure 2). What is so exceptional about this tablet is that while Side b. is entirely intact (Figure 3), most of Side a. has been heavily damaged with long linear scratches made after the tablet had been baked (Figure 2). While Frahm notes these to be intentional, he does not comment on why they are only present on one side of the tablet, or why they are so long, parallel, and painstaking in places.[51] Scrutiny of the photograph included in the volume demonstrates that these are strikings-through of lines, as the lines run carefully through the middle of signs, implying that whoever did this possessed literacy, or at least some familiarity with cuneiform writing. As Side b. is unscathed, the implication must be that its text was needed for some purpose, perhaps for recopying, while that of Side a. was of no further use. One good possibility is that this side, which contains many brief episodes describing the reception of tributes, had been selected for deletion from the historical record;[52] if so, then this would be remarkable material evidence of the redaction of annalistic texts, although this would require further parallels to confirm.

The first of Side a.’s episodes (ll. 1’–8’) fragmentarily describes a campaign to a land possessing horses and a population referred to with the ‘barbarian they’ and contains the name ‘Adad-nārārī’ near its close. The following ruled section of two lines (ll. 9’–10’) describes an imposition of tribute upon a ruler whose name is lost. Yet another section of two lines (ll. 11’–12’) follows describing the reception of tribute from a ‘barbarian they’. The next possesses three unsalvageable lines (ll. 13’–15’). A single-line ruled section then refers to the reception of a livestock tribute without a ‘barbarian they’ (l. 16). A final ruled section of five lines before the tablet breaks is almost entirely gone (ll. 17’–21’); what little remains displays the ‘barbarian they’.

Side b. is far better preserved, presenting two longer narratives divided by a ruled line. The first (ll. 1’–10’) is somewhat fragmentary, but concerns the flaying and execution of a leader at Ninūa, the mutilation of his men, and the destruction of his city. The second narrative (ll. 11’–22’) describes an insurrection at Naṣībīna, possibly inflamed by another group (l. 12’), the name of which is not preserved. The Assyrian king defeats and horrifically tortures the insurrectionists, and then encircles another city, this one belonging to a ruler. This is followed by a march into the ḫabḫu-lands of the Kāšiāru (i.e. Ḫabḫu 4) before the text breaks off.

KAL 3: 56 Side a. (Photograph: Maul, Assur-Forschungsstelle Heidelberg).

KAL 3: 56 Side b. (Photograph: Maul, Assur-Forschungsstelle Heidelberg).

Perhaps the most obvious point of attack is the name Adad-nārārī (Side a., l. 7’), and yet this is unfortunately not all that diagnostic. The campaign in question must have taken place in the Upper Tigris or Zagros due to the horses present as spoil, most likely the former. As Adad-nārārī I campaigned as far afield as Eluḫat (RIMA.0.77.1 8; 2 38), he cannot be discounted as the referent here, although his later namesake was much more active there and revered by his son, as discussed.

Rather, the most vital indicator is the appearance of Naṣībīna, which provides a chronological framework. This polity was only defeated by Adad-nārārī II in 896, at which point its ruler Nūr-Adad was replaced with a docile new client king as described in a colourful passage.[53] Despite Adad-nārārī II’s continued activities in the Upper Ḫābūr, no mention is made of the city up to the end of annalistic documentation in 893, presenting a reasonable terminus post quem for the revolt. In turn, a good terminus ante quem is lent by the itinerary of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s journey up the Greater Ḫābūr at the close of his largely peaceful Medioeuphratine campaign of 885; the monarch ceased collecting tribute after Šadikanni (Tall ‘Aǧāǧa, Syria), implying that the series of settlements (including Naṣībīna) through which he passed thereafter on the way to Ḫuzīrīna (Sultantepe, Turkey) were not vassals, but rather provincial centres (RIMA.0.100.5 115–20). Were this to hold, then a brief window between late 893 and mid-to late 887 would be available for this uprising, probably discounting Adad-nārārī II and Aššur-nāṣir-apli II. While such an insurrection could be supposed subsequent to provincialisation, the multiple campaigns through the Kāšiāru mountains undertaken by Aššur-nāṣir-apli II early in his reign without mention of incident at Naṣībīna would seem to imply that the southern approaches to the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn were well secured, and that it was now the ḫabḫu-lands (4) nestled within the range which posed an issue (see Radner 2006a).

Considering all of the minor (and apparently deleted) actions listed on Side a. and the grander business of the capture and flaying of the ruler of a city prior to the revolt at Naṣībīna and ensuing campaign on Side b. (of what is at all preserved of the tablet), it seems very unlikely that Adad-nārārī II would have had time for these many activities alongside a new war with Karduniaš and an assault on Sūḫu in the three years prior to his death.[54]

In turn, and quite vitally, the gruesome and precisely documented torture forming the text’s most distinctive hallmark (akin to KAL 3: 45–46, see above) is entirely absent from Adad-nārārī II’s royal inscriptions, where enemies are simply slain in heaps. Here, some 45 or more individuals receive amputations, blindings (in one instance with apparently molten tin!), and mutilation of the ears. While Aššur-nāṣir-apli II also amputated the arms of captured soldiers and unabashedly decapitated, flayed, impaled, and even immured (RIMA.0.101.1 72), the other brutalities meted out here were not in his punitive inventory. Considering that KAL 3: 45–46 (see above) fields yet more of the same grisly horrors and displays many other similarities, it should be assumed that the same king commissioned both inscriptions.

A further point is the siegecraft depicted. Adad-nārārī II’s inscriptions laud him as having invented the siege technique used here of encirclement with fortresses during the siege of Raqamātu/Gidāra in 898 (RIMA.0.99.2 54–55). That it appears here (KAL 3: 56 Side b. 18’–19’) without further comment implies that this tactic was no longer novel and must postdate that year (and, indeed, 893). The same stratagem is employed in KAL 3: 45–46 10’–11’, further underlying these two texts’ chronological and stylistic propinquity. In turn, this technique excludes an ascription to the reign of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II, as this king favoured entirely different and more aggressive siege techniques such as storming, tunnelling, or using battering rams and siege towers.[55]

Hence, all of these various factors indicate that the events of this text must have occurred within the early years of the reign of Tukultī-Ninurta II (i.e. 890–887). From these findings, the capture and flaying of an enemy leader at Ninūa and the torture of his men in Side b., ll. 1’–10’ might be examined. Flaying at Ninūa or Arba’il (rather than in the field) was reserved for enemies of importance, either kings or individuals of particular royal loathing;[56] furthermore, this individual nonetheless only held sway over a single city, but possessed silver and gold. Finally, a broken ethnicon ]-˹a˺-ia survives (b. l. 3’). Considering the established timeframe, three plausible candidates exist: Apâ, king of the city-state of Ḫubuškia, an unknown ruler of an affluent city in Lāqê, or the governor of Sūḫu as all possess appropriately written gentilica[57] and rendered silver and gold as tribute.[58] What would bespeak Lāqê is the very similar treatment of Aḫi-yababa in 882 at Sūru of Bīt-Ḫalupê (probably Tall Fidēn, Syria), but what contradicts this is the lack of any disturbance of the lucrative region of Lāqê between Adad-nārārī II’s march of 894 and Tukultī-Ninurta II’s visit of 885, during which it was obviously in boom, and the very specific case of Aḫi-yababa who had killed Aššur-nāṣir-apli II’s double brother-in-law by inherited marriage;[59] in turn, none of Lāqê’s emporia were destroyed during this period.[60] Sūḫu may be similarly discounted: It was only defeated at the end of Adad-nārārī II’s reign, and Ilu-bāni/ibni would seem to have governed it from then on until his death early in the reign of Aššur-nāṣir-apli II.[61] Hence, it seems most likely that it is the ill fate of Apâ, King of Ḫubuškia, to which the reader is here party, which would make sense considering his appearance on the summary inscription. As his successors are termed ‘King of Na’iri’ (perhaps a hereditary or hegemonic title among the royalty of the Taurus and Zagros),[62] the prominence of this kingdom during this period is evident; in turn, Tukultī-Ninurta II would have truly earned the title kāšid (mātāt) Na’iri by authoring this sovereign’s doom. However, the question remains as to what justified this punishment. It is worth comparing this episode to that of Būbu, son of Babua the bēl-āli of Ništun, who was flayed by Aššur-nāṣir-apli II in his first regnal year (RIMA.0.101 i 67–68) shortly after Gilzānu and Hubuškia presented their tributes at Ḫabrûri (i 56–57); no motivation for this act is presented by the annals, and it is possible that it was done simply “pour encourager les autres”,[63] as the Assyrian demand for horses had become a crucial issue.[64]

Considering the tight timeframe of three years at the beginning of Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign, the deletion of the events of Side a., and that KAL 3: 45–46 must also date to this chronological span, the most logical constellation of events is to understand the events of Side b. as the latest events. Placing Side a.’s events prior to this, it seems most likely these six to seven campaigns occurred very early in Tukultī-Ninurta II’s reign, and that they had thereafter been redacted on account of their inconsequentiality once this king had achieved greater things (such as the defeat of Apâ), a situation akin to that of Ušḫu and Atkun’s deletion from the annals as early as 909 (see above). In light of the tightness of the period, it would be most logical to infer the Naṣībīna episode ending in a foray into the Upper Tigris region of Side b. 11’–22’ as constituting the first half of the Na’iri campaign of 887, which begins in media res in RIMA.0.100.5 1–3 with a return through the Ṭūr ‘Aḇdīn after campaigning in the Upper Tigris, pillaging Ki[baki] (presumably Mağara, Turkey) on the journey back. This would place the other campaigns in the Upper Ḫābūr and Upper Tigris recorded in KAL 3: 45–46 in the intervening period, perhaps between 889 and 888. With this analysis of the five texts completed, new portraits may be now presented of these two kings.

5 Adad-nārārī II – Warrior King

Adad-nārārī II’s reign is marked by sweeping conquests, the two main targets of which were Karduniaš and Ḫanigalbat. His throne name (which he himself intriguingly calls an “important name” [šumu kabtu, RIMA.0.99.2 9–10]) was programmatic,[65] as his namesake not only conquered a large swathe of Ḫanigalbat, but also celebratedly vanquished the Kassite king Nazi-Maruttaš, a deed celebrated in both an Assyrian epic composition and elsewhere in later literary tradition (Frazer 2013). The remarkable ambition implied by this decision is already demonstrated by the activities of his year of accession (911); after a minor campaign to Ušḫu and Atkun, perhaps as a first test of his abilities, Adad-nārārī II launched what would seem to be a surprise offensive on Qumānû, attacking its capital Kipšūna and capturing its king, Ilūya, and enforcing vassalage upon the kingdom. This aggressive strategy from the very outset could only have been enabled by a military and populace reinvigorated after the deprivations of the previous decades, and it must be assumed that Aššur-dān II’s reign had been responsible for this reflorescence. The following reconstruction of his reign can now be presented (Table 7):

A new chronological summary of the events of Adad-nārārī II’s reign.

| 911 | AN II’s accession. Campaign to Ušḫu and Atkun | KAL 3: 48 6’–11’ | |

| Campaign to Qumānû | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 10–19; KAL 3: 48 12’–18’; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 15’–16’ | ||

| Mid-late 911 to ca. mid 910 | (10–15 lines of campaign narrative, either various smaller campaigns or 1–2 larger campaigns) | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. 20-ca. 30 | |

| ca. mid 910 to mid-909 | Campaign and annexation of Arrapḫa. War with Babylonia probably initiated | RIMA.0.99.1 obv. ca. 30 | |

| Mid-late 909 | Campaign to the Tigris, defeat of 40 cities, deportation of 3 others | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 1’–5’ | |

| 4th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 909 | Campaign against Ḫabḫu (3) and land of Meḫru | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 6’–9’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 24–25; KAL 3: 16–17 16’ | |

| 6th Kislīmu (IX) 909 | Renovation of quay at Aššur completed | RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 10’–20’ | |

| Unknown year a. (909–901) | Campaign deeper into Ḫabḫu (3) to Salua and Uraṭri | RIMA.0.99.2 24–25; KAL 3: 16–17 16’–17’ | |

| Unknown year b. (first half of 900’s) | Prior (same year) | 1st Na’iri campaign | KAL 3: 47 1’–7’ |

| 28th Kislīmu (IX) | 2nd Na’iri campaign (very brief) | KAL 3: 47 8’–9’ | |

| Directly following previous campaign | Conquest of Katmuḫi | KAL 3: 47 10’-14’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 26; KAL 3: 16–17 21 | |

| Unknown year b.+1 (= year. c) | Date given but broken | Another campaign, of which nothing is preserved | KAL 3: 47 15’ |

| Unknown year d. (=c.?) | Defeat of Babylonia, conclusion of 1st Babylonian war | KAL 3: 16–17 27’–29’; cf. ABC 21 iii 1–7 | |

| Unknown year(s) e. | Campaign to Lullumê, Zamūa, Ḫabḫu (2), and Namri. (year d. likely terminus post quem) | RIMA.0.99.2 23–24; KAL 3: 16–17 13’–15’ | |

| Unknown year(s) f. | 1st campaign | 4th Na’iri campaign | KAL 3: 53 1’–6’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 30 |

| 2nd campaign | Defeat and resettlement of the Aḫlamû | KAL 3: 53 7’–8’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 33 | |

| 3rd campaign | Campaign to Middle Euphrates | KAL 3: 53 9’–13’; cf. RIMA.0.99.2 33 | |

| 901 or (immediately?) prior | Renovation of Apku completed | RIMA.0.99.2 36–38 | |

| 901 | 1st Ḫanigalbat campaign. Nūr-Adad of Naṣībīna defeated at Pa’uza | RIMA.0.99.2 39–41 | |

| 900 | 2nd Ḫanigalbat campaign. Battle at Naṣībīna. Yaridu raided. Saraku occupied with the region’s crops | RIMA.0.99.2 42–44 | |

| 899 | 3rd Ḫanigalbat campaign. Huzīrīna taken. Mamlī defeated. Bīt-Adini sends diplomatic gift | RIMA.0.99.2 45–48 | |

| 898 | 4th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Mūquru of Raqamātu/Gidāra defeated | RIMA.0.99.2 49–60 | |

| 897 | 5th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Tribute received | RIMA.0.99.2 61 | |

| 896 | Earlier | 6th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Naṣībīna defeated after siege. Nūr-Adad removed and new client king installed | RIMA.0.99.2 62–80; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 48’–50’ |

| Later | Campaign to Sikkur and Sappānu | RIMA.0.99.2 80–90 | |

| 15th Simānu (III) 895 | 1st campaign to Kumme | RIMA.0.99.2 91–93; KAL 3: 16–17 17’–19’ | |

| Nisannu (I) 894 | 2nd campaign to Kumme | RIMA.0.99.2 94–96; KAL 3: 16–17 19’–20’ | |

| Simānu (III) 894 | 7th Ḫanigalbat campaign. Tribute collected. Campaign to the Middle Euphrates | RIMA.0.99.2 97–119; cf. KAL 3: 16–17 51’ | |

| 17th Abu (V) 893 | Renovation of Gula Temple at Aššur completed | RIMA.0.99.2 128-34 | |

| Late 893 to 891 | 2nd Babylonian war and subsequent peace treaty | KAL 3: 16–17 30’–34’; cf. ABC 21 iii 8-21 | |

| 2nd campaign to Sūḫu (after Babylonian war) | KAL 3: 16–17 39’–41’ | ||

| (other campaign[s]?) | KAL 3: 16–17 35’–38’; 52’ onwards | ||

| 891 | AN II dies | ||

In the wake of this early victory, it seems that Adad-nārārī II already assaulted and took the Babylonian protectorate of Arrapḫa between late 911 and mid-909. As discussed, it is unclear whether his Karduniaš campaign should be linked with this activity or not. During this period, in the autumn of 909, he also attacked forty settlements on the Tigris and deported the populations of three, all seemingly belonging to a mountainous or pastoral polity, although it is unclear whether this occurred upstream or downstream of Assyria.[66] On 4th Araḫsamnu (VIII) 909, he would march into Meḫru, a vital source of timber (RIMA.0.99.1 rev. 6’–9’): That he ventured into the mountains so late in the year bespeaks once more his remarkable energy as king, and, indeed, he would even campaign into Na’iri as deep into winter as 28th Kislīmu (IX) on another occasion (KAL 3: 47 8’–9’, see above). At some point between early 908 and 901, he must have surpassed this and marched on to the more distant regions of Salua and Uraṭri (perhaps in the region of Çatak, Turkey?) as summarised in RIMA.0.99.2 24–25.

Only the vaguest of chronologies can be established for the ensuing period up to 901, and considering the remarkable number of actions already in his first years, various minor campaigns might be assumed. Whether it occurred prior to or after late 909, his successful war with Karduniaš was the defining achievement of this period, leading him to style himself kāšid (māt) Karduniaš. This need not have been a single year’s campaigning, but the decisive moment was the resounding defeat of his adversary Marduk-mudammiq, who is stated by the Synchronistic Chronicle to have adopted a defensive position on Mount Yalman, and his pursuit of the Babylonian to the River Turān (Diyālā), where the latter appears to have abandoned much of his equipment (ABC 21 iii 1–7). It may well be in the aftermath of this event that Adad-nārārī II undertook his dramatic foray southwards to Dēru (Tall al-‘Aqar, Iraq); in light of the religious significance of this city (Frahm 2009a) and the impermanence implied by kašādu, this may well have been a propagandistic pilgrimage (akin to Kumme) rather than a military operation. In the aftermath, Assyria had incorporated Lubdu (vicinity of the Ǧabal Ḥamrīn, Iraq) and controlled a swathe of territory stretching as far south as Laḫīru (1).[67]

The wake of this victory must have witnessed considerable ‘mopping up’, such as the re-incorporation of Idu (Sātū Qalā, Iraq) and Zaqqu into Assyria. It would also have been the precondition for campaigning in Lullumê which ensued, as Assyria’s new north-eastern flank now lay open.[68] His annals mention campaigning as far as the passes of Namri, also a Babylonian holding during this period. It is in this context that the rather forlornly named Assyrian garrison of Tukulti-Aššur-aṣbat at Arrakdi (probably as-Sulaymānīya, Iraq, see Radner 2017) must have been established, although it is unclear whether Adad-nārārī II or Tukultī-Ninurta II was responsible, and it may well have been the latter.

It was likely in the wake of his Babylonian expansion that Adad-nārārī II turned his attention to Na’iri. As KAL 3: 47 demonstrates, two campaigns to Na’iri certainly preceded his assault on Katmuḫi, which must have happened in the year following the second campaign, as it is dated to 28th Kislīmu (IX), at the very limits of the campaigning season. Perhaps marching through or around this previously disloyal vassal’s territory to the Upper Tigris presented a frustration, and so he determined to annex the kingdom come spring. The terminus post quem for this action would have been 907, thus with the second Na’iri campaign having unfolded late in 908, but these campaigns could also have reasonably occurred within the mid-900’s. As the remaining sources intimate, the chief priority here was the procuring of horses from the thriving husbandry of the Upper Tigris basin. The presumed reconquest of the cities of Arinu, Turḫu, and Zaduru from Šubria (RIMA.0.99.2 35 – the sentence is very curiously formulated) must have occurred during this period, and demonstrates the establishment of a ‘pre-provincial’ presence in the region, presumably in cooperation with the relict Assyrian community there (see Edmonds 2021: 79–81). His devastation of Alzi during the same period (RIMA.0.99.2 31–32) was likely a prophylactic measure to secure these Assyrian possessions. Following the intimations in KAL 3: 53, what was probably the last of the Na’iri campaigns saw the reinforcement of an Assyrian outpost in the Upper Tigris, presumably at Damdammusa, as is demonstrated by the harvesting of crops for the garrison there, and then his return through the Kāšiāru, his objectives apparently fulfilled. The conclusion of his Na’iri campaigns may have been close to 901, as a general spirit of consolidation throughout Assyria is evident during this later period.