A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of pranayama in reducing anxiety and stress in adolescents

Abstract

Background

Pranayama has garnered increasing attention in recent years due to its potential therapeutic effects on mental and physical health. However, a lack of age-specific synthesis of its efficacy, especially among adolescents, highlights the need for focused evaluation in this population. Therefore, this study aims to systematically review and meta-analyze (SRMA) the effectiveness of pranayama in reducing stress and anxiety in adolescents.

Methods

A systematic search was done on four databases, namely, the Cochrane Library, Medline (PubMed), Embase, and Web of Science, for articles published between 1st January 2015 and 31st December 2024. Independent screening of the articles was done by two reviewers, and duplicates were removed using NESTED Knowledge. Quality assessment of the studies was done using Cochrane and the JBI tools. A meta-analysis was undertaken in “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA)” software, and heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic.

Results

Eighteen studies were included in this SRMA of which 11 were RCTs and 7 were quasi-experimental studies. The overall standardized mean difference (SMD) was −1.166 [95 % CI: −1.979 to −0.353], indicating a moderate effect on stress reduction in favor of deep breathing. GRADE assessment revealed very low certainty of evidence due to serious concerns in the risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision domains.

Conclusions

Integrating pranayama into adolescents’ daily lives can help reduce their anxiety and stress levels. Rigorous research is required to generate good quality scientific evidence in this field.

Introduction

Pranayama is a yogic breathing practice involving controlled breathing techniques and has garnered increasing attention in recent years due to its potential therapeutic effects on mental and physical health [1]. Increased stress and anxiety may occur during adolescence, a crucial developmental stage marked by profound physical, emotional, and psychological changes. The prevalence estimates of stress and anxiety disorders among adolescents are alarmingly high, to the extent that 20 % of them have severe anxiety symptoms at some time throughout their adolescence [2]. The detrimental impact of stress and anxiety on academic performance, social relationships, and overall well-being is well known. There is an urgent need for effective interventions that can be easily integrated into the lives of youngsters. Pranayama is an integral component of yoga, deeply rooted in ancient Indian philosophy. It encompasses different techniques to regulate the breath, thereby influencing the mind and body. Pranayama practices are believed to enhance self-awareness, promote relaxation, and emotional regulation [3]. Researchers have explored the efficacy of pranayama as a non-pharmacological intervention for managing stress and anxiety among adolescents. According to preliminary research, consistent practice may result in significant decrease in anxiety and improvement in mood [4]. However, the existing literature is characterized by considerable variability in study designs, sample sizes, and methodological rigor, which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. The mechanisms behind the impact of pranayama on anxiety and stress are multifaceted. Research indicates that controlled breathing can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, leading to a state of relaxation [5]. This activation may result in reduced cortisol levels, thereby mitigating the physiological reactions occurring in response to stress [6]. Furthermore, pranayama has been shown to enhance the vagal tone, leading to improved emotional well-being and resilience against stressors [7]. These physiological changes may contribute to the observed psychological benefits of pranayama. Despite the promising evidence supporting pranayama’s role in alleviating stress and anxiety, there remains a lack of comprehensive reviews synthesizing the available data specifically focused on adolescents. Most existing reviews have primarily concentrated on adult populations or have not differentiated between various age groups [8]. This gap in the literature underscores the necessity for a “systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA)” that specifically examines the impact of pranayama on stress and anxiety in adolescents, systematically evaluating the current body of evidence. In addition to assessing overall efficacy, it is crucial to explore potential moderators that may influence the outcomes of pranayama interventions, as factors such as frequency and duration of practice, type of pranayama technique employed, and baseline anxiety and stress levels may all play significant roles in determining the effectiveness [9].

Methodology

This SRMA was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Table S1).

Inclusion criteria

Studies in English that were either “randomized controlled trials (RCTs)” or quasi-experimental in design were included. Observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, case-control), case reports, case series, letters, communications, editorials, abstracts, and conference proceedings were excluded. Studies on adolescents (aged 10–19 years) were included if the intervention was yogic breathing (pranayama), regardless of the type, frequency, or duration. , and the outcome measured was stress and/or anxiety measured using standard validated instruments. Studies involving adolescents with comorbidities were excluded. Studies were included if the intervention was compared with no treatment, placebo, or any other form of physical or breathing exercise. Studies employing any co-intervention were eligible if the same was employed across all the groups studied (Table S2).

Outcome variables

Change in stress and/or anxiety levels of adolescents.

Search strategy

Electronic databases, namely, the “Cochrane Library, Medline (PubMed), Embase, and Web of Science”, were searched for articles published between 1st January 2015 and 31st December 2024, with detailed search strings provided as a supplementary file (Table S3). Screening: After removing duplicate records, the title and abstract screening were carried out by two reviewers independently (GO and KD), and eligible studies were identified. Discrepancies when encountered were addressed through adjudication or by involving a third reviewer (AG) where necessary. Subsequently, GO and KD screened the full texts of the included articles independently. The discrepancies were resolved through adjudication with the third reviewer (AG).

Data extraction

Data extraction was done using a predesigned data extraction form. Details on the study participants, intervention and control arms, stress and anxiety as the outcomes, and their measures were extracted independently by two reviewers (GO and KD). This was followed by need-based adjudication and involvement of a third reviewer (AG) where discrepancies were encountered. Following this, an independent risk of bias assessment was conducted by the same two reviewers using the Cochrane “Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2)” for RCTs, and the JBI tool for quasi experimental studies.

Statistical analysis

To estimate pooled outcomes, a random-effects model based on maximum likelihood estimation was applied. The variability between studies was done using the I2 statistic, prediction intervals were also determined to capture the range of likely effects [10]. While Doi plots and the “Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK)” index were planned to assess publication bias, they were not used due to the smaller number of studies eligible for meta-analysis. “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA)” software was used for all statistical analyses [11], 12]. A correlation coefficient of 0.5 was assumed between pre- and post-intervention stress levels. To examine the stability of the results, sensitivity analyses were also performed using correlation values of 0.1 and 0.9.

Certainty of evidence

GRADEpro software was used to evaluate the certainty of the pooled estimate of each outcome, following the “Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE)” methodology [13].

Ethics

Ethics review is not applicable since this is a systematic review of already published studies.

Results

Study selection

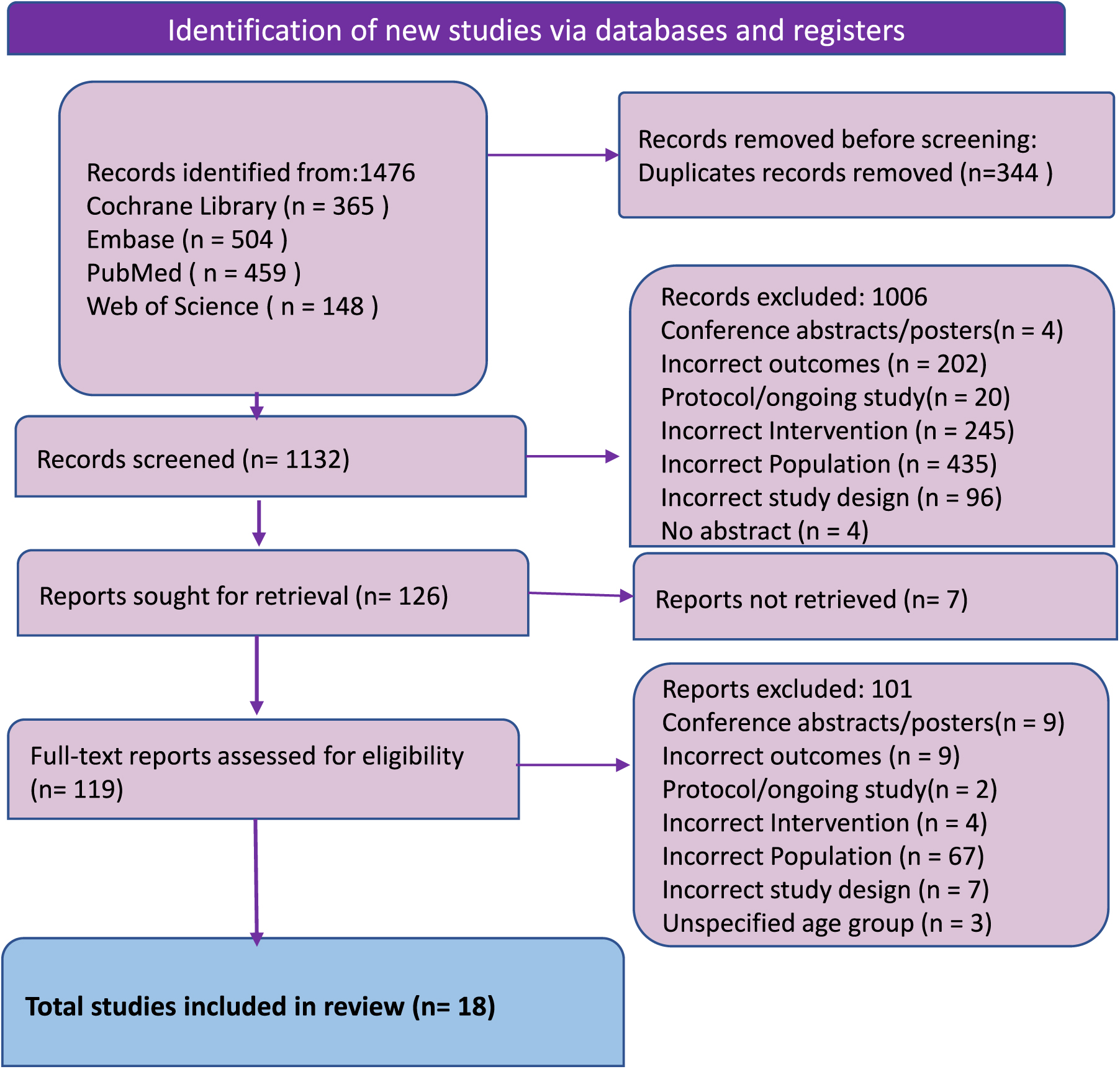

An efficient two-stage screening was done by two independent reviewers (GO and KD). Nested Knowledge was used for the proper management of all the studies extracted. Searching through the selected databases yielded 1,476 records. After removing duplicates and applying the exclusion criteria, 119 full-text studies were reviewed. For the final analysis, 18 records were included, of which 11 were RCTs and 7 were quasi-experimental studies (6 studies employed the before-after design and 1 was a non-randomized comparative study) (Figure 1).

PRISMA diagram for selection of the studies.

Characteristics of the included studies

The final eligible studies were from the USA, European countries, namely Poland, Germany, Portugal, and Greece, and Asian countries, namely South Korea, Indonesia, India, and Malaysia. The interventions were not homogeneous across studies. A total of 2,007 and 1,530 participants belonged to the exposed and control groups, respectively. The various interventions included in the 11 RCTs [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24] and 7 [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] quasi-experimental studies were various breathing exercises, including diaphragmatic breathing, deep breathing, abdominal breathing, pranayama, and app-guided breathing [14], 24]. Few studies reported the effect of specific types of breathing exercises like Kapalbhati, Nadi Shuddhi, Savitri Pranayama, and Anulom Vilom. Tellas et al. [19] and Wilson et al. [29] studied the effect of high-frequency breathing exercise, whereas Rodrigues et al. [20] studied the impact of deep breathing as a part of Quigong exercise. The durations and frequencies of the interventions varied from 2 to 12 weeks and from two times to several times per day (as described by Okado et al.). The most common intervention was deep breathing or pranayama (Table 1).

Characteristics of included studies.

| Sr no | Author, year | Study design | Study setting, region | Intervention | Sample size (intervention group) | Sample size (control group 1) | Sample size (control group 2) | Sample size (control group 3) | Duration of intervention (frequency) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Okado et al., 2020 [14] | RCT | Public university, California, USA | Diaphragmatic breathing | 44 (Diaphragmatic breathing training with handout) | 43 (Existing relaxation strategy) | 44 (Existing relaxation strategy with handout) | 81 (Online only, no face-to-face contact) | 2 weeks (several times a day) |

| 2 | Kim et al., 2024 [15] | RCT | Metro city, South Korea | Ten minutes of breathing exercise both before and after the program | 16 (Wind instrument and choral training group) | 17 (Choral training group) | 17 (Listening to music that helps with emotional relaxation) | NA | 12 weeks (2 times a week, 120 min per session) |

| 3 | Dziembowska et al., 2015 [16] | RCT | Psychophysiology laboratory, Poland | Abdominal breathing through pursed lips | 20 (Abdominal breathing through pursed lips) | 21 (Nothing) | NA | NA | 3 weeks (10 sessions in 3 weeks, 20 min per session) |

| 4 | Ariga et al., 2015 [25] | Quasi-experimental, non RCT | University, Medan, Indonesia | Deep breathing | 20 (Deep breathing) | 20 (NA) | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | Schleicher et al., 2024 [17] | RCT | District Hospital, Germany | Breathing exercises integrated into smartphones as a health app | 36 | 37 (Natural relaxation) | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | Nebhinani et al., 2024 [26] | Quasi-experimental, pre-post | Institute of National Importance, Rajasthan, India | Deep breathing | 100 | NA | NA | NA | 2 weeks with 8 modules of 1 h each |

| 7 | Ranjani et al., 2023 [18] | Cluster RCT | Schools at Chennai and New Delhi, India | Pranayama or deep breathing | 996 | 1,004 (45-min Educational session on healthy living) | NA | NA | 17 Sessions over 5 months (10-min session once a week) |

| 8 | Adhikari et al., 2023 [27] | Quasi-experimental, pre-post | University, Madhya Pradesh, India | Anulom-vilom and Kapalbhati | 50 | NA | NA | NA | 8 weeks (5 min 3 times a week) |

| 9 | Lagare et al., 2023 [28] | Quasi-experimental, non-RCT | Government Medical College, Kolhapur, India | Kapalbhati and Yogic Shwasan, followed by Nadi Shuddhi, Bhastrika and Bhramari | 30 | 120 (Nothing) | NA | NA | 12 weeks (20 min a day 6 days a week) |

| 10 | Telles et al., 2019 [19] | RCT | School, India | High-frequency yoga breathing, | 61 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | Wilson et al., 2015 [29] | Quasi-experimental, pre-post | School, Boston | High-frequency yoga breathing, | 85 | NA | NA | NA | 6–8 weeks (At least 30 min a week) |

| 12 | Wang et al., 2024 [30] | Quasi-experimental, pre-post | Public college, Malaysia | Abdominal breathing | 31 | NA | NA | NA | 5 weeks (60-min sessions 3 times a week) |

| 13 | Rodrigues et al., 2024 [20] | RCT | School, Portugal | Qigong exercise | 34 | 34 (Watching a TV documentary) | 36 (Typical school duties) | NA | 6 weeks (−8 sessions of 15–20 min each) |

| 14 | Parajuli et al., 2022 [21] | RCT | School, India | Breathing exercises and pranayama | 45 | 44 (Physical exercise) | NA | NA | 2 Months (1 h a day 4 days a week) |

| 15 | Khng et al., 2016 [22] | RCT | School, Singapore | Deep breathing | 154 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 16 | Bentley et al., 2022 [23] | Cluster RCT | Public high school, California, USA | Self-paced slow diaphragmatic breathing | 25 | 18 (Treatment as usual) | NA | NA | 5 weeks (3 times a week) |

| 17 | Nithiya Devi et al., 2018 [31] | Quasi-experimental, pre-post | Medical college hospital and research institute, Pondicherry, India | Savitri pranayama | 250 | NA | NA | NA | 2 h (4 Cycles of 5 min each) |

| 18 | Dimou et al., 2013 [24] | RCT | University, Athens, Greece | Diaphragmatic breathing | 30 | 30 (Nothing) | NA | NA | 8 weeks (2 times a week) |

The anxiety scales used across the included studies were “State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)”, “Patient Health Questionnaire – Somatization, Anxiety, and Depression (PHQ-SADS)”, “Spielberger’s State Trait Anxiety Inventory – State (STAI-S)”, “State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC)”, and DASS 21 (Supplementary Table S4). The Perceived Stress Scale, “Psychological Social Well-Being Index (PWI-SF)”, Trier Social Stress Test, subjective stress levels via ratings, Medical Students Stressor Questionnaire, “ADOlescence Stress Scale (ADOSS)”, Stress questionnaire designed by the International Stress Management Association, and Stress management subscale of the “Health-promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II)” were used for evaluating stress. Salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase levels were also used as surrogate markers of stress [17], 18].

Results of analysis

Deep breathing and its effect on stress

The pooled estimate shows that deep breathing significantly reduces stress levels compared to the pre-intervention period, over a 1–4 month period [15], 24]. Overall standardized mean difference (SMD) is −1.166 [95 % CI: −1.979 to −0.353], revealing a moderate effect in favor of deep breathing (Supplementary Figure 2). However, there was a substantial heterogeneity among the studies (I2=74.46 %). Sensitivity analysis at correlation coefficients of 0.1 and 0.9 did not change the significance of the results obtained (Supplementary Figure 1). The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed that the study by Kim et al. appeared to influence the results notably, and when it was removed, the overall effect remained statistically significant [15] (Supplementary Figure 3).

Narrative synthesis

Okado et al. [14] conducted a pilot study on the impact of short-term relaxation training on preventing stress-related problems, involving 132 participants who completed an in-person research session. A significant decline in anxiety scores was observed after a one-on-one diaphragmatic breathing training session among male athletes in this pilot study, which used a stress management tool consisting of rhythmic breathing. In the RCT conducted for 21 days, the mean anxiety levels of the intervention group significantly decreased (mean change = −4; p<0.001), whereas the control group showed no substantial change (p=0.817). In addition, compared to the control group, athletes who underwent biofeedback training showed notable and statistically significant improvements in heart rate variability, as well as substantial changes in alpha asymmetry and theta and alpha brain wave power spectra [16]. Khng et al. [22], Ranjani et al. [18], Nebhinani et al. [26], Ariga et al. [25], and Okado et al. [14] reported the effects of deep breathing on anxiety and stress levels. Nebhinani et al. observed a significant reduction in academic, interpersonal, social, and group activity-related stressors. The total stress score declined from 53.27 (±21.42) to 44.30 (±20.42) after three months of deep breathing exercises [26].

Pranayama interventions such as Anulom Vilom, Kapalbhati, and Savitri pranayama were used in several studies to assess their effects on stress and anxiety [21], 27], 28], 31]. Practicing pranayama for 5 min, three times a week, led to a reduction in stress scores from 9.42 (±2.80) to 3.96 (±1.04). A significant decrease in stress and anxiety-related difficulties was observed after a two-week follow-up. The pranayama group’s mean “Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)” score was significantly lower than that of the control group both immediately before the test and after the training (p<0.05) [28]. In both, an RCT [19] and a quasi-experimental study [29], high-frequency yoga breathing was used as an intervention to evaluate its effects on anxiety and stress. It was found that the STAI-S score decreased from 37.59 (±10.51) to 32.46 (±10.10) after practicing the intervention for 6– 8 weeks. It was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis for anxiety as an outcome variable due to the lack of a common outcome variable across the included studies.

Risk of bias

Out of the included RCTs, the quality assessment revealed a generally strong methodological quality, with most studies rated as having low risk or some concerns. Several studies, including Okado et al. [14], Kim et al. [15], and Dziembowska et al. [16], showed some concerns. Schleicher et al. [17] was the only study rated as having a high risk of bias overall, primarily due to a high risk in the domain of missing outcome data (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Table S5). All seven quasi-experimental studies had an overall appraisal as good and hence were included in the SRMA (Supplementary Table S6).

Certainty in evidence

GRADE assessment revealed very low certainty in the effectiveness of the breathing exercise in reducing the stress in adolescents, primarily due to serious concerns in risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision domains (Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

Deep breathing and pranayama interventions significantly reduce stress and anxiety over 1–4 months. This meta-analysis shows a moderate effect in favor of deep breathing (SMD = −1.166), though high heterogeneity exists (I2=74.46 %). Sensitivity analysis confirms result stability, with Kim et al. having a notable impact on results [15].

According to studies by Okado et al. [10] and Nebhinani et al. [22], there is a substantial decrease in stress in several domains, such as social and academic stressors. Biofeedback trials showed improvements in brainwave activity and variability in heart rate among male athletes. In RCTs, anxiety scores significantly decreased (p<0.001), and stress levels were further reduced by pranayama techniques, including Anulom Vilom and Kapalbhati, which were practiced three times per week. Over a 6- to 8-week period, high-frequency yoga breathing interventions reduced STAI-S scores. Overall, there was strong evidence that organized breathwork was effective at reducing stress, and other trials confirmed long-term advantages.

An experimental study by Joshi et al. on the effect of Om chanting and Bhramari Pranayama found significant reductions in anxiety levels among adolescents after a 20-day intervention, daily for 25 min [32]. According to Singh et al., the effects of pranayama techniques on teenage mental health, 30 min daily for 12 weeks, using techniques like Anulom Vilom and Bhastrika, significantly lowered stress, anxiety, and depression [33]. According to a study by Goswami et al. evaluating the effects of yoga and pranayama on emotional intelligence and mental health in Rajasthan, teens who engaged in both practices reported less stress and higher emotional intelligence than those who did not [34].

Cramer et al. conducted an SRMA including eight RCTs that evaluated yoga’s ability to reduce anxiety in adults diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Practicing yoga, comprising both breathing and asanas, had greater effects on anxiety than active comparators (SMD = −0.86, p=0.02) and smaller but significant effects than no therapy (SMD = −0.43, p=0.008). Depression showed slight improvements (SMD = −0.35, p=0.03). However, only three RCTs showed safety data findings without additional hazards, and effects were equivocal for recognized anxiety disorders [35]. While showing the potential of yoga, Khajuria et al.’s comprehensive evaluation of the biological effects of yoga on stress reduction utilizing biosignals revealed a dearth of research regarding the underlying mechanisms [36]. Maity et al.’s meta-analysis assessed how well yoga performed to enhance the physical and mental health of medical and dental students. Analysis of 18 studies indicated that yoga was a useful intervention, with substantial reductions in heart rate, stress (0.77 reduction), anxiety (1.2 reduction), and diastolic (2.92 mmHg) and systolic (6.82 mmHg) blood pressure [37]. More high-quality studies are recommended to strengthen the role of breathing practices in anxiety and stress management.

Adolescents practicing breathing exercises and pranayama experience less stress and anxiety because of improved parasympathetic activity, a regulated autonomic nervous system, and lower cortisol levels [33]. Methods like Bhastrika pranayama regulate brain activity, lowering amygdala hyperactivity associated with stress, and Nadi Shodhana enhances oxygenation and emotional balance [38]. Pranayama promotes emotional control and resilience, which is proven to improve mental health [39].

The strength of this study is that it is the first systematic review and meta-analysis determining the efficacy and effectiveness of Pranayama and yogic breathing exercises in reducing anxiety and stress in adolescents globally, showcasing notable strengths such as adherence to PRISMA guidelines, a comprehensive dataset of 18 studies encompassing 3,537 adolescent participants (intervention group: 2007 and control group: 1,530) across diverse regions, and a long time frame (2015–2024).

The findings were further validated by thorough sensitivity and risk of bias testing. Generalizability and reliability are improved by the majority of high-quality studies having low risk/minor issues. Yet, some limitations nevertheless require careful consideration. Despite comprehensive sensitivity analyses, the substantial heterogeneity in pooled estimates (I2=74.46 %) revealed variability among studies, most likely driven by differences in population dynamics, design, demographics, and diagnostic techniques/study instruments. Furthermore, estimations may have been impacted due to the exclusion of gray literature, unpublished studies, and studies published in languages other than English. Pooling results for anxiety using meta-analysis was not feasible due to the lack of a common outcome variable. GRADE assessment revealed very low certainty in the effectiveness of the breathing exercise in reducing stress in adolescents. Although these limitations do not diminish the validity of the study, they might affect the wider applicability.

Conclusions

Breathing techniques/Pranayama offer an effective means to improve adolescents’ mental health. Pranayama’s mind-body approach appears encouraging in current times when psychological and pharmacological treatments are commonly employed to manage stress and anxiety. In conclusion, the findings of this SRMA provide promise for incorporating pranayama as a useful intervention for reducing anxiety and stress in adolescents. There is a need for future studies that are rigorous in methodology to generate quality evidence in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the contribution of the Department of Health Research supported SARANSH-1 (Systematic Reviews And Networking Support in Health) workshop organised by the Department of Community medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur, India and the Technical Resource Centre (Centre for evidence-based guidelines), AIIMS Nagpur for developing their capacity to undertake the systematic review.

-

Research ethics: Ethics review is not applicable since this is a systematic review of already published studies.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: Concept and design: GO, KD, DI, APG. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: GO, KD, DI, APG. Drafting of the manuscript: GO, KD, PH, DI, APG. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: GO, KD, PH, DI, APG. Supervision: APG.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Nested Knowledge a semi-automated, AI-assisted platform for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses, was utilized to screen the studies.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Available in the manuscript and supplementary files.

-

PROSPERO Registration: CRD42025622283.

References

1. Jayawardena, R, Ranasinghe, P, Ranawaka, H, Gamage, N, Dissanayake, D, Misra, A. Exploring the therapeutic benefits of pranayama (yogic breathing): a systematic review. Int J Yoga 2020;13:99–110. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.ijoy_37_19.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Merikangas, KR, He, JP, Burstein, M, Swanson, SA, Avenevoli, S, Cui, L, et al.. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. Adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:980–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Brown, RP, Gerbarg, PL. Sudarshan Kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med 2005;11:711–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2005.11.711.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Narasimhan, L, Nagarathna, R, Nagendra, H. Effect of integrated yogic practices on positive and negative emotions in healthy adults. Int J Yoga 2011;4:13. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.78174.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Magnon, V, Dutheil, F, Vallet, GT. Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults. Sci Rep 2021;11:19267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98736-9.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Martarelli, D, Cocchioni, M, Scuri, S, Pompei, P. Diaphragmatic breathing reduces exercise‐induced oxidative stress. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:932430. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nep169.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Tyagi, A, Cohen, M, Reece, J, Telles, S, Jones, L. Heart rate variability, flow, mood and mental stress during yoga practices in yoga practitioners, non-yoga practitioners and people with metabolic syndrome. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2016;41:381–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-016-9340-2.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Tyagi, A, Cohen, M. Yoga and heart rate variability: a comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Yoga 2016;9:97. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.183712.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Khalsa, SBS. Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 2004;48:269–85.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Gandhi, AP, Shamim, MA, Padhi, BK. Steps in undertaking meta-analysis and addressing heterogeneity in meta-analysis. The Evidence 2023;1:78–92. https://doi.org/10.61505/evidence.2023.1.1.7.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Borenstein, M, Hedges, L, Higgins, J, Rothstein, H. Comprehensive meta‐analysis software. 2021:425–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119558378.ch49.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Daniel, WW, Cross, CL. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health Sciences, 11th ed. Wiley; 2018. https://www.perlego.com/book/3865662/biostatistics-a-foundation-for-analysis-in-the-health-sciences-pdf [Accessed 23 Jul 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

13. GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro guideline development tool [Software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime; 2025. https://www.gradepro.org/ [Accessed 23 Jul 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

14. Okado, Y, De Pace, D, Ewing, E, Rowley, C. Brief relaxation training for the prevention of stress-related difficulties: a pilot study. Int Q Community Health Educ 2020;40:193–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684x19873787.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Kim, BS, Kim, H, Kim, JY. Effects of a choral program combining wind instrument performance and breathing training on respiratory function, stress, and quality of life in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2024;19:e0276568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276568.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Dziembowska, I, Izdebski, P, Rasmus, A, Brudny, J, Grzelczak, M, Cysewski, P. Effects of heart rate variability biofeedback on EEG alpha asymmetry and anxiety symptoms in male athletes: a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2016;41:141–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9319-4.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Schleicher, D, Jarvers, I, Kocur, M, Kandsperger, S, Brunner, R, Ecker, A. Does it need an app? – differences between app-guided breathing and natural relaxation in adolescents after acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024;169:107148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2024.107148.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Ranjani, H, Jagannathan, N, Rawal, T, Vinothkumar, R, Tandon, N, Vidyulatha, J, et al.. The impact of yoga on stress, metabolic parameters, and cognition of Indian adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Integr Med Res 2023;12:100979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2023.100979.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Telles, S, Gupta, RK, Gandharva, K, Vishwakarma, B, Kala, N, Balkrishna, A. Immediate effect of a yoga breathing practice on attention and anxiety in pre-teen children. Children 2019;6:84. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6070084.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Rodrigues, JM, Matos, LC, Francisco, N, Dias, A, Azevedo, J, Machado, J. Assessment of Qigong effects on anxiety of high-school students: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Mind Body Med 2021;35:10–9.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Parajuli, N, Pradhan, B, Bapat, S. Effect of yoga on cognitive functions and anxiety among female school children with low academic performance: a randomized control trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2022;48:101614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101614.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Khng, KH. A better state-of-mind: deep breathing reduces state anxiety and enhances test performance through regulating test cognitions in children. Cognit Emot 2017;31:1502–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1233095.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Bentley, TGK, Seeber, C, Hightower, E, Mackenzie, B, Wilson, R, Velazquez, A, et al.. Slow-breathing curriculum for stress reduction in high school students: lessons learned from a feasibility pilot. Front Rehabil Sci 2022;3:864079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.864079.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Dimou, PA, Bacopoulou, F, Darviri, C, Chrousos, GP. Stress management and sexual health of young adults: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Andrologia 2014;46:1022–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/and.12190.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Ariga, RA. Decrease anxiety among students who will do the objective Structured Clinical Examination with deep breathing relaxation technique. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2019;7:2619–22. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.409.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Nebhinani, N, Kuppili, PP, Mamta. Feasibility and effectiveness of stress management skill training in medical students. Med J Armed Forces India 2024;80:140–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.10.007.MamtaSuche in Google Scholar

27. Adhikari, DM. Event of yogic exercises on psychological variables among the adolescents. J Pharm Negat Results 2023:599–601. https://doi.org/10.47750/pnr.2023.14.S01.7428.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Lagare, DAA, Shimpi, DPV. Effect of pranayama on stress level and VO2Max in first MBBS students. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2023;14:3207–13.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Wilson, HK, Scult, M, Wilcher, M, Chudnofsky, R, Malloy, L, Drewel, E, et al.. Teacher-led relaxation response curriculum in an urban high school: impact on student behavioral health and classroom environment. Adv Mind Body Med 2015;29:6–14.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Wang, F, Syed Ali, SKB. Health benefits of short Taichi Qigong exercise (STQE) to University Students’ core strength, lower limb explosive force, cardiopulmonary endurance, and anxiety: a Quasi experiment research. Medicine (Baltim) 2024;103:e37566. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000037566.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Devi, RN. Immediate effect of savitri pranayama on anxiety and stress levels in young medical undergraduates. Biomedicine 2018;38:254–7.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Joshi, DK. Effect of Om chanting and bphramari Pranayama on anxiety level among adolescents. IJOYAS 2006;2. https://indianyoga.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/v2-issue1-article6.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Singh, S, Kumar, DN. Impact of pranayama techniques on adolescent mental health: a study in palwal district. Soc Sci J 2023;13:5704–18.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Goswami, D. Study of effect of practice of pranayama and yoga on mental health, emotional intelligence and resilience of adolescents. JETIR 2023;10.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Cramer, H, Lauche, R, Anheyer, D, Pilkington, K, de Manincor, M, Dobos, G, et al.. Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 2018;35:830–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22762.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Khajuria, A, Kumar, A, Joshi, D, Kumaran, SS. Reducing stress with yoga: a systematic review based on multimodal biosignals. Int J Yoga 2023;16:156–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.ijoy_218_23.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Maity, S, Abbaspour, R, Bandelow, S, Pahwa, S, Alahdadi, T, Shah, S, et al.. The psychosomatic impact of Yoga in medical education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online 2024;29:2364486. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2024.2364486.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Novaes, MM, Palhano-Fontes, F, Onias, H, Andrade, KC, Lobão-Soares, B, Arruda-Sanchez, T, et al.. Effects of yoga respiratory practice (Bhastrika pranayama) on anxiety, affect, and brain functional Connectivity and activity: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00467.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Pandey, KN. Yoga as a mediating factor for stress, depression, anxiety, and adjustment in adolescents. Int J Adv Acad Stud 2025;7:110–2. https://doi.org/10.33545/27068919.2025.v7.i4b.1435.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2025-0094).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Investigating the determinants of mental health literacy in school students: a school-based study

- Examination of quality of life and expressed emotion in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without specific learning disorder

- A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of pranayama in reducing anxiety and stress in adolescents

- Depression and anxiety among transgender-identifying adolescents in psychiatric outpatient care

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Adolescents’ knowledge, attitude and perceived risks towards e-cigarette usage in Johor Bahru, Malaysia

- Beyond the puff: unravelling patterns and predictors of tobacco usage among adolescents and youth in Delhi, India

- Violence, Trauma, and Safety

- Development and psychometric properties of the adolescent risk behavior questionnaire

- “Tracing the impact of childhood adversity on social anxiety in late adolescence: the moderating role of social support and coping strategies”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Mental Health and Well-being

- Investigating the determinants of mental health literacy in school students: a school-based study

- Examination of quality of life and expressed emotion in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without specific learning disorder

- A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of pranayama in reducing anxiety and stress in adolescents

- Depression and anxiety among transgender-identifying adolescents in psychiatric outpatient care

- Substance Use and Risk Behaviours

- Adolescents’ knowledge, attitude and perceived risks towards e-cigarette usage in Johor Bahru, Malaysia

- Beyond the puff: unravelling patterns and predictors of tobacco usage among adolescents and youth in Delhi, India

- Violence, Trauma, and Safety

- Development and psychometric properties of the adolescent risk behavior questionnaire

- “Tracing the impact of childhood adversity on social anxiety in late adolescence: the moderating role of social support and coping strategies”