Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric

-

Sujinun Junsomang

, Apichet Jumneansuk

Abstract

Objectives

This study investigates the effectiveness of the P-Positive program in addressing emotional aggression among junior high school students in Lopburi Province, Thailand.

Methods

A quasi-experimental one-group pretest-posttest design was employed with 54 participants aged 13–15. The intervention, conducted over 16 weeks, applied the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) framework. Key components included emotional regulation, empathy development, and behavioral change, facilitated through structured activities. Emotional intelligence was assessed using the EQ Metric, evaluating nine dimensions comprehensively.

Results

Statistically significant improvements were observed across all dimensions of emotional intelligence (p<0.001). The most notable improvements were in self-control, empathy, and decision-making, with motivation showing the highest mean difference (4.333). Inner peace exhibited the smallest mean improvement (1.593), but the change was still statistically significant. These findings highlight the program’s effectiveness in enhancing emotional intelligence and reducing aggression.

Conclusions

The P-Positive program shows strong potential as a scalable intervention for improving emotional well-being and mitigating aggression in adolescents. It offers valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and public health stakeholders, suggesting the importance of integrating such programs into broader educational and health initiatives. Further refinements to address specific dimensions like inner peace may enhance its impact.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical stage of life marked by rapid emotional, social, and psychological changes that influence behavior significantly. Emotional aggression, manifesting as intense anger or inappropriate emotional responses, often stems from heightened sensitivity, peer pressure, and limited problem-solving skills during this transitional period [1]. Addressing such behaviors is crucial due to their potential to escalate into long-term mental health issues and societal challenges.

Globally, aggressive behavior among adolescents remains a pressing concern. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 32.8 % of secondary school students exhibit violent behaviors, while 16.6 % regularly carry weapons. Every year, violence-related injuries hospitalize over 707,212 young individuals aged 10–24, while school-related incidents claim the lives of 17 school-aged children [2]. In 2020, the Department of Mental Health in Thailand reported that aggressive behaviors affect 3.8 % of adolescents aged 13–15, or approximately 150,000 youth, primarily males. Contributing factors include neurochemical imbalances, family upbringing, exposure to violent media, and the imitation of inappropriate behaviors [3].

In addition to behavioral impacts, emotional aggression increases the risk of substance abuse, risky sexual behaviors, teenage pregnancies, and educational challenges, ultimately affecting family dynamics and social relationships [4]. Effective interventions are essential to mitigate these risks and foster emotional regulation among adolescents.

Current measures for managing emotional aggression among adolescents in Thai schools primarily focus on rules, punishments, and behavior control strategies to suppress aggressive expressions. However, these measures often lack an emphasis on emotional regulation and self-awareness, which are critical factors in addressing aggression effectively. The P-Positive program tries to fill in these gaps by combining the development of emotional intelligence (EQ) with structured activities that aim to make people more self-aware and give them the tools they need to control their emotions. The program further aims to reduce interpersonal conflicts, strengthen peer relationships, and proactively develop emotional skills before disputes arise, distinguishing itself from traditional reactive approaches.

The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) model guides the design of the P-Positive program, a behavioral intervention that aims to reduce aggressive tendencies. This framework focuses on cultivating knowledge, fostering positive attitudes, and promoting constructive behaviors. Central to the program’s implementation is the EQ Metric, a validated tool for assessing critical dimensions of emotional intelligence, such as self-awareness, empathy, and emotional regulation [5]. The EQ Metric effectively captures these dimensions, recognizing emotional intelligence as a pivotal factor in managing aggression.

In the context of Thai adolescents, the EQ metric holds particular relevance. The tool not only measures emotional regulation but also captures cultural nuances and interpersonal dynamics unique to this population. Its application enables a deeper understanding of how emotional intelligence influences behaviors within the Thai educational setting, providing data that can guide targeted interventions. Furthermore, the EQ Metric facilitates the identification of specific emotional and social deficits, allowing for the development of tailored strategies to address aggressive behaviors.

Despite the growing recognition of emotional intelligence in mitigating aggression, limited research has focused on evaluating the P-Positive program’s effectiveness among Thai adolescents, particularly in educational settings. This study seeks to bridge this gap by assessing the impact of the P-Positive program on emotional aggression in junior high school students, utilizing the EQ Metric as a key evaluative tool. This research aims to evaluate changes in emotional aggression levels before and after participation in the P-Positive program. Additionally, it explores the program’s effectiveness in enhancing emotional regulation and promoting positive social behaviors. By addressing these objectives, the study aspires to contribute to the development of evidence-based interventions tailored to the needs of Thai adolescents, ultimately fostering improved emotional well-being and social harmony in schools and communities.

Methods

Design and procedure

This study employed a quasi-experimental design, specifically a one-group pretest-posttest design, to evaluate the impact of the intervention. Data on aggressive behaviors were collected at two time points: prior to the intervention during the first week (pretest) and after the completion of the intervention during the sixteenth week (posttest). The study spanned a total of 16 weeks, during which participants engaged in structured activities aimed at addressing emotional aggression.

The intervention program, based on the P-Positive framework, was conducted over the course of 16 weeks. Participants attended weekly sessions that incorporated activities designed to enhance emotional regulation, foster empathy, and reduce aggressive tendencies. Each session was guided by the principles of the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) model, ensuring a focus on cultivating knowledge, improving attitudes, and promoting positive behavioral practices.

Participants and sampling

The participants in this study consisted of 54 junior high school students from Lopburi Province. The software G*Power was used to figure out the sample size. The test family was set to t-tests; the statistical test was named Mean: Difference between two dependent means (matched pairs); and the type of power analysis was set to a priori. Compute the required sample size – give α=0.05 and power=0.95. The effect size was set at 0.50, as suggested by Cohen (1977) [6]. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: students enrolled in grades 7–9 in schools located in Lopburi Province, attending the first semester of the 2024 academic year, and exhibiting emotional intelligence (EQ) scores below the normal range in at least four dimensions. Additionally, students were required to provide informed consent to participate in the program.

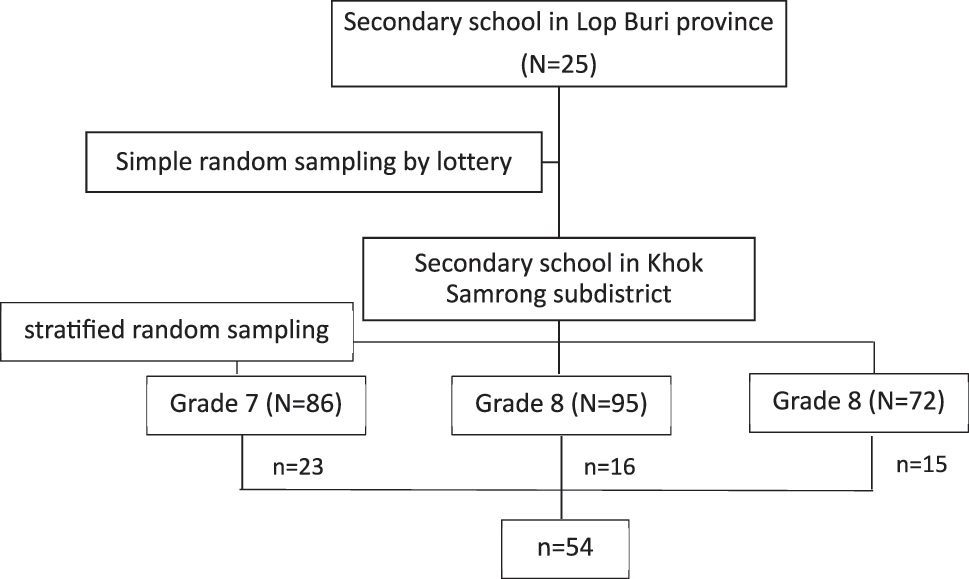

A two-step sampling approach was employed. First, schools and classrooms were selected using simple random sampling through a lottery system. Then, stratified random sampling was used to select participants from each grade level proportionally. The final sample included 23 students from grade 7, 16 students from grade 8, and 15 students from grade 9 (Figure 1). This sampling method ensured a representative distribution of participants across the different grade levels. By focusing on students with low EQ scores, the study aimed to target those most likely to benefit from the intervention, thereby maximizing the potential impact of the P-Positive program.

A flow chart for sampling.

Instruments

The instruments utilized in this study consisted of two components: the intervention program, P-Positive, and the evaluation tools for assessing outcomes. We designed the P-Positive Program as an intervention to reduce emotional aggression through structured activities conducted over 16 weeks. The program comprised eight activities aimed at fostering positive attitudes, emotional regulation, and behavioral change among participants. We repeated each activity cyclically from week two to week eight until we completed the 16-week duration. Table 1 presents the details of the activities.

Overview of the P-positive Program.

| Week | Activity name | Activity details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Icebreaking activity |

|

| 2 | Positive attitude |

|

| 3 | Positive knowledge |

|

| 4 | Positive relationship | Group bingo game involving mini-games or Q&A sessions to earn bingo chips if required. |

| 5 | Positive perception | Participants write behaviors they dislike when faced with aggression and share them in a group circle. |

| 6 | Positive priority | Group ranking activity: Teams prioritize the severity of aggressive behaviors using a provided board. |

| 7 | Positive thinking | Mini-game activity: Participants answer questions to progress toward a final goal. |

| 8 | Follow-up assessment | Summary of weekly activities and final assessment of individual aggression behaviors. |

The evaluation tools consisted of a self-administered questionnaire divided into two sections: (1) General information gathered demographic data, including gender, age, living arrangements, and family status.; (2) Emotional Intelligence Assessment the Emotional Intelligence (EQ) Scale consisted of 52 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (from “very true” to “not true”). This scale was developed by the Department of Mental Health [7] and assessed nine dimensions of emotional intelligence: Self-control (normal range: 13–18 points), Empathy (normal range: 16–21 points), Responsibility (normal range: 17–22 points), Motivation (normal range: 15–20 points), Decision-making and problem-solving (normal range: 14–19 points), Relationships (normal range: 15–20 points), Self-esteem (normal range: 9–13 points), Life satisfaction (normal range: 16–22 points), and Inner peace (normal range: 15–21 points).

The reliability of the EQ scale was supported by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.75 to 0.85, indicating high internal consistency. This tool provided a comprehensive measure of emotional intelligence, which was critical for evaluating changes in participants’ aggression levels before and after the intervention.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and variance, were used to describe the general characteristics of the sample and to summarize the levels of aggressive behavior before and after the intervention. A Paired Sample t-test was used to compare the mean scores of aggressive behaviors before and after the intervention.

Results

The data collection from 54 participants revealed the following demographic characteristics. The majority of the participants were male (53.7 %). Over half of the participants were 13 years old (55.5 %), with a mean age of 13.57 ± 0.716 years. Most participants lived with both parents (50.0 %), and the most common family status was parents living together (55.5 %), followed by separated families (25.9 %). Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 2.

Characteristics of samples (n=54).

| Characteristics | n, % | Characteristics | n, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Living arrangements | ||

| Male | 29 (53.7) | Living with both parents | 27 (50.0) |

| Female | 25 (46.3) | Living with either father or mother | 14 (25.9) |

| Age | Not living with either parent | 13 (24.1) | |

| 13 years old | 30 (55.5) | Family status | |

| 14 years old | 17 (31.5) | Living together | 30 (55.5) |

| 15 years old | 7 (13.0) | Divorced/Separated | 20 (37.0) |

| Mean±S.D=13.57 ± 0.716 years old Min=13 years old, max=15 years old |

Father or mother deceased/Both parents deceased | 4 (7.5) | |

The descriptive statistics for emotional aggression scores before and after the intervention are summarized in Table 3. The findings indicate improvements across all dimensions following participation in the P-Positive program. Each dimension consisted of six items, except for the Self-esteem dimension, which had four items. For Self-control, the mean score increased from 15.20 ± 2.334 before the intervention to 19.13 ± 1.749 after the intervention. Similarly, the mean score for Empathy improved from 16.57 ± 3.679 to 19.43 ± 1.609. In the Responsibility dimension, the mean score rose from 17.19 ± 2.978 to 18.78 ± 2.044. The Motivation dimension showed a significant increase, with the mean score rising from 15.22 ± 2.500 before the intervention to 18.78 ± 1.870 afterward. For Decision-making and problem-solving, the mean score increased from 14.69 ± 2.401 to 19.02 ± 1.447. In terms of Relationships, the mean score improved from 14.59 ± 3.195 to 18.85 ± 1.630. The Self-esteem dimension, which had four items, also demonstrated an increase, with the mean score rising from 9.61 ± 2.141 to 12.39 ± 1.250. For Life satisfaction, the mean score increased from 15.11 ± 3.045 to 19.24 ± 1.682. Lastly, the mean score for Inner peace improved from 14.39 ± 2.923 to 18.57 ± 1.678. Details in Table 3.

The descriptive statistics for emotional aggression scores.

| Emotional aggression | Before experimental | After experimental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean ± S.D. | Min | Max | Mean ± S.D. | |

| Self-control | 10.0 | 20.0 | 15.20 ± 2.334 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 19.13 ± 1.749 |

| Empathy | 9.0 | 23.0 | 16.57 ± 3.679 | 16.0 | 22.0 | 19.43 ± 1.609 |

| Responsibility | 12.0 | 23.0 | 17.19 ± 2.978 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 18.78 ± 2.044 |

| Motivation | 10.0 | 22.0 | 15.22 ± 2.500 | 15.0 | 22.0 | 18.78 ± 1.870 |

| Decision-making and problem-solving | 9.0 | 21.0 | 14.69 ± 2.401 | 16.0 | 22.0 | 19.02 ± 1.447 |

| Relationships | 8.0 | 22.0 | 14.59 ± 3.195 | 15.0 | 22.0 | 18.85 ± 1.630 |

| Self-esteem | 4.0 | 14.0 | 9.61 ± 2.141 | 10.0 | 16.0 | 12.39 ± 1.250 |

| Life satisfaction | 8.0 | 22.0 | 15.11 ± 3.045 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 19.24 ± 1.682 |

| Inner peace | 7.0 | 20.0 | 14.39 ± 2.923 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 18.57 ± 1.678 |

The paired sample t-test results for emotional aggression dimensions before and after the intervention are summarized in Table 4. Significant improvements were observed across all dimensions, as indicated by the mean differences, confidence intervals, and p-values. For Self-control, the mean difference was 3.926 (95 % CI: 3.209–4.643), with a t-value of 10.983 and a p-value of <0.001, indicating a significant improvement after the intervention. Similarly, the Empathy dimension showed a mean difference of 2.852 (95 % CI: 1.840–3.864), t=5.651, p<0.001. In the Responsibility dimension, the mean difference was 3.556 (95 % CI: 2.750–4.361), with a t-value of 8.856 and a p-value of <0.001. The Motivation dimension had the largest mean difference, 4.333 (95 % CI: 3.582–5.085), t=11.562, p<0.001, demonstrating a substantial effect. For Decision-making and problem-solving, the mean difference was 4.259 (95 % CI: 3.335–5.184), t=9.238, p<0.001. In the Relationships dimension, the mean difference was 2.778 (95 % CI: 2.099–3.456), with a t-value of 8.214 and a p-value of <0.001. The Self-esteem dimension, which consisted of four items, also showed a significant improvement, with a mean difference of 4.130 (95 % CI: 3.220–5.039), t=9.110, p<0.001. For Life satisfaction, the mean difference was 4.185 (95 % CI: 3.315–5.055), t=9.652, p<0.001. Finally, the Inner peace dimension had a mean difference of 1.593 (95 % CI: 0.812–2.373), t=4.094, p<0.001. Although the mean difference in this dimension was smaller compared to others, it was still statistically significant. Details in Table 4.

Paired sample t-test results for emotional aggression dimensions before and after the intervention.

| Emotional aggression | 95 % confidence interval | Mean differences | Std. Deviation | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Self-control | 3.209 | 4.643 | 3.926 | 2.627 | 10.983 | <0.001 |

| Empathy | 1.840 | 3.864 | 2.852 | 3.708 | 5.651 | <0.001 |

| Responsibility | 2.750 | 4.361 | 3.556 | 2.950 | 8.856 | <0.001 |

| Motivation | 3.582 | 5.085 | 4.333 | 2.754 | 11.562 | <0.001 |

| Decision-making and problem-solving | 3.335 | 5.184 | 4.259 | 3.388 | 9.238 | <0.001 |

| Relationships | 2.099 | 3.456 | 2.778 | 2.485 | 8.214 | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem | 3.220 | 5.039 | 4.130 | 3.331 | 9.110 | <0.001 |

| Life satisfaction | 3.315 | 5.055 | 4.185 | 3.186 | 9.652 | <0.001 |

| Inner peace | 0.812 | 2.373 | 1.593 | 2.858 | 4.094 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate significant improvements in all dimensions of emotional aggression among junior high school students following participation in the P-Positive program. Demographic analysis revealed that the majority of participants were male, aged 13, and lived with both parents, reflecting the typical characteristics of adolescents in the educational context. Notably, age was found to have a statistically significant influence on the expression of emotional aggression, particularly among students aged 13 and 14. This aligns with research indicating that age is a critical factor affecting aggressive behaviors in adolescents. Younger adolescents, who may exhibit lower psychosocial maturity, are more likely to display aggressive tendencies [8].

Descriptive statistics revealed significant increases in mean scores across all dimensions of emotional aggression. Key improvements were observed in Self-control, Empathy, and Decision-making and Problem-solving, highlighting the program’s effectiveness in fostering awareness and behavioral adjustment. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating that life skills development programs significantly enhance emotional intelligence in adolescents [9]. Moreover, the Motivation dimension exhibited the largest mean difference (4.333), indicating that participants became more enthusiastic and committed to managing their emotions positively. This is consistent with research showing that life skills training enhances motivation and determination in adolescents [9].

Inferential statistics further confirmed the program’s effectiveness. Paired t-test results indicated statistically significant differences (p<0.001) between pre- and post-intervention scores across all dimensions. Dimensions such as Self-control, Empathy, and Responsibility showed notable improvements, reflecting the program’s impact on essential emotional and social skills. These results align with previous findings that life skills programs can significantly improve students’ emotional and social intelligence [10]. Although the Inner Peace dimension exhibited the smallest mean change (1.593), it remained statistically significant. This suggests that developing inner peace may require additional time or alternative methods, underscoring the need to refine the program to emphasize this dimension.

The use of the KAP (Knowledge, Attitude, Practice) model in the P-Positive program played a pivotal role in achieving behavioral changes. By focusing on enhancing knowledge, reshaping attitudes, and promoting practice through diverse activities such as group discussions, games, and self-reflection, the program effectively facilitated positive behavioral transformations. Similar to Moitra et al. (2021), who reported that the KAP model improved knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to nutrition and exercise among Indian adolescents, this study confirms the model’s utility in shaping adolescent behavior [11]. Papasteri et al. (2024) found that the KAP framework effectively enhanced knowledge, attitudes, and practices in pandemic response strategies, further supporting its applicability in behavioral interventions [12].

The study also highlights the importance of using the EQ Metric as an evaluation tool. The metric effectively measured specific dimensions of emotional intelligence comprehensively, enabling the development of targeted intervention strategies for emotional and social behaviors within the Thai cultural and educational context. Additionally, the systematic use of the EQ Metric supported monitoring and evaluation of adolescents’ emotional skills development, facilitating the refinement of educational programs or supplementary activities that focus on emotional intelligence. This aligns with Bradberry (2022), who emphasized the value of EQ tools in fostering adolescents’ readiness to face challenges in life and society [13]. In conclusion, the application of the EQ Metric provided valuable insights into the strengths and areas for improvement in students’ emotional intelligence. Its alignment with Thai cultural values, which emphasize interpersonal relationships and social harmony, underscores its relevance in educational settings. This study confirms that assessing EQ is a powerful tool for promoting desired behaviors while mitigating undesirable ones, ultimately contributing to a more supportive and effective learning environment [13], 14].

Implications

The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of the P-Positive program in reducing emotional aggression and enhancing emotional intelligence among junior high school students. These results provide actionable implications for educational institutions, administrators, homeroom teachers, and subject teachers. Integrating this program into the school curriculum could address behavioral issues and promote social-emotional development among students. Furthermore, the findings suggest incorporating additional activities or methods specifically designed to enhance inner peace, a dimension with comparatively smaller improvements. Adjustments to the program, such as including mindfulness practices or reflective activities, could further support emotional stability and resilience in adolescents.

Households can adapt the P-Positive program by fostering emotional awareness and open communication within families. This approach strengthens parent-adolescent relationships, builds trust, and reduces emotional aggression at home. Additionally, practicing emotional regulation and empathy in a family setting provides consistent support, reinforcing skills learned at school across all environments.

Strengths and limitations

The evaluation and assessment of the program utilized the EQ Metric, enabling a detailed examination of emotional intelligence dimensions. This approach provided in-depth insights into the program’s impact across specific areas. Furthermore, the program’s activities incorporated the KAP framework (Knowledge, Attitude, Practice), reinforcing the structure of behavioral changes with a strong foundation in psychological and educational theories. This study addressed a critical issue among adolescents – emotional aggression – while offering practical and applicable recommendations for educators and school administrators.

However, there are limitations associated with the study design. The use of a one-group pretest-posttest design without a control group makes it difficult to definitively attribute observed changes solely to the program. Future research should include a control group to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings. Additionally, this study was conducted in a single province with a relatively small sample size, which may not fully represent the broader adolescent population. Expanding the sample to include diverse regions and demographics would improve the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the evaluation focused on short-term outcomes immediately after the program’s completion. Longitudinal studies are essential to assess the sustainability of behavioral changes over time. Addressing these limitations in future research will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the program’s effectiveness and its long-term impact.

Conclusions

The P-Positive program significantly reduced emotional aggression among junior high school students, highlighting its potential as an effective intervention for fostering emotional regulation and social skills. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the integration of emotional intelligence-based interventions into educational settings to promote adolescent well-being and prevent aggressive behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to the administrators, teachers, and students from the participating schools in Lopburi Province for their cooperation and commitment throughout this study. Their support and active engagement were invaluable to the successful implementation of the P-Positive program and the completion of this research.

-

Research ethics: Approval was granted by Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat University under the Royal Patronage Ethics Committee of Human Research: 0033/2567.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: The authors declare that ChatGPT, was utilized to improve the language and readability of this manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Arnett, JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000;55:469–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469.Suche in Google Scholar

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Global status report on violence prevention. Geneva: WHO; 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Boonruang, T. Department of Mental Health reveals survey results on Thai youth behavior; 2020. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jan 7]. Available from: https://dmh.go.th/.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Hennes, H, Christine, L. Youth violence: risk and protective factors. Pediatrics 2011;127:480–90.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence: why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books; 1995.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Cohen, J. Statistical power for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1977.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Department of Mental Health, Ministry of Public Health. EQ Manual: Emotional Intelligence. Mental health knowledge repository, Small Book Edition. Department of Mental Health; 2020. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jan 7]. Available from: https://dmh-elibrary.org/items/show/1199.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Srimahaprom, N, Jeewattana, S, Sri-Ngan, K. Causal factors affecting the aggressive behavior of grade 9 students. J Humanit Soc Sci Mahasarakham Univ 2022;42:85–95.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Suwanasaeng, N, Jittanoon, P, Balthip, K. The effect of life-skill development program on emotional intelligence of female adolescents in homes for children. Songklanagarind J Nurs. 2018;38:22–34.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Wichakul, S. Effects of life-skill program on emotional intelligence of the vocational students at bangsaen technical college, chonburi province. Reg Health Promot Cent 9 J. 2023;17:868–81.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Moitra, P, Madan, J, Verma, P. Impact of a behaviourally focused nutrition education intervention on attitudes and practices related to eating habits and activity levels in Indian adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2021;24:2715–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Papasteri, C, Letzner, RD, Pascal, S. Pandemic KAP framework for behavioral responses: initial development from lockdown data. Curr Psychol 2024;43:22767–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05670-w.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Bradberry, T. 11 signs that you lack emotional intelligence; 2022. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jan 7]. Available from: https://www.talentsmarteq.com/11-signs-that-you-lack-emotional-intelligence/#:∼:text=People%20who%20fail%20to%20use,and%20even%20th.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Rajanukul Institute. Survey on the situation of IQ and EQ levels among Thai school-aged children and related factors; 2017. [Internet] [cited 2025 Jan 7]. Available from: https://th.rajanukul.go.th/.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric