Abstract

Atg18, Atg21 and Hsv2 are homologous β-propeller proteins binding to PI3P and PI(3,5)P2. Atg18 is thought to organize lipid transferring protein complexes at contact sites of the growing autophagosome (phagophore) with both the ER and the vacuole. Atg21 is restricted to the vacuole phagophore contact, where it organizes part of the Atg8-lipidation machinery. The role of Hsv2 is less understood, it partly affects micronucleophagy. Atg18 is further involved in regulation of PI(3,5)P2 synthesis. Recently, a novel Atg18-retromer complex and its role in vacuole homeostasis and membrane fission was uncovered.

1 Introduction

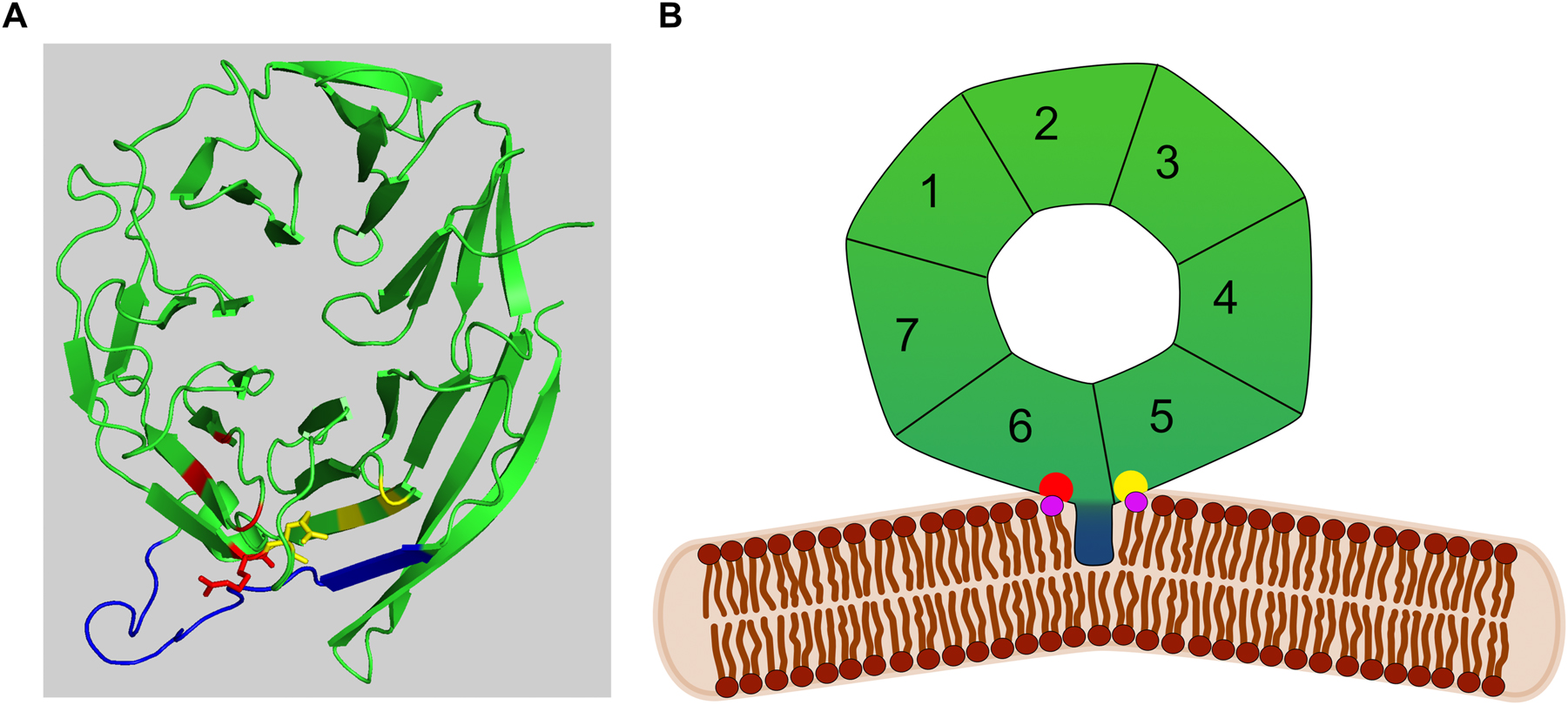

Saccharomyces cerevisiae Atg18, Atg21 and Hsv2 are members of a highly conserved family of PROPPINs (β-propeller that bind polyphosphoinositides). As shown by X-ray crystallography they fold as seven bladed β-propellers and bind via two binding sites at their circumference to PI3P and PI(3,5)P2 (Figure 1) (Baskaran et al. 2012; Krick et al. 2012; Lei et al. 2021; Liang et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2020; Scacioc et al. 2017; Watanabe et al. 2012). Atg18 and Atg21 were initially identified for their requirement for macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) (Barth and Thumm 2001; Barth et al. 2001; Guan et al. 2001; Meiling-Wesse et al. 2004; Obara et al. 2008; Reggiori et al. 2004; Stromhaug et al. 2004). During autophagy double membraned autophagosomes are formed, which fuse with the lysosome (vacuole) and release their contents for degradation and recycling. Autophagosomes can either enclose cytosol or selectively envelope superfluous or damaged organelles as well as bulky cargoes such as aggregates or pathogens. Accordingly, autophagy plays a major role in cellular homeostasis and quality control and is highly conserved from yeast to humans. Defects in autophagy are relevant for numerous diseases (Hu and Reggiori 2022; Klionsky et al. 2021; Yamamoto et al. 2023).

Structural features of PROPPINs. (A) Structure of K. lactis Hsv2 according to (Krick et al. 2012). The amphipathic α-helical loop 6CD is shown in blue, while the arginines in PI3P/PI(3,5)P2 binding site 1 and 2 are shown in red and yellow, respectively. (B) Model of Atg18 interacting with PI3P/PI(3,5)P2 (violet) via its binding sites (red and yellow). The amphipathic loop 6CD (blue) is partly inserted into the membrane and induces membrane bending.

2 Role of PROPPINs in autophagy

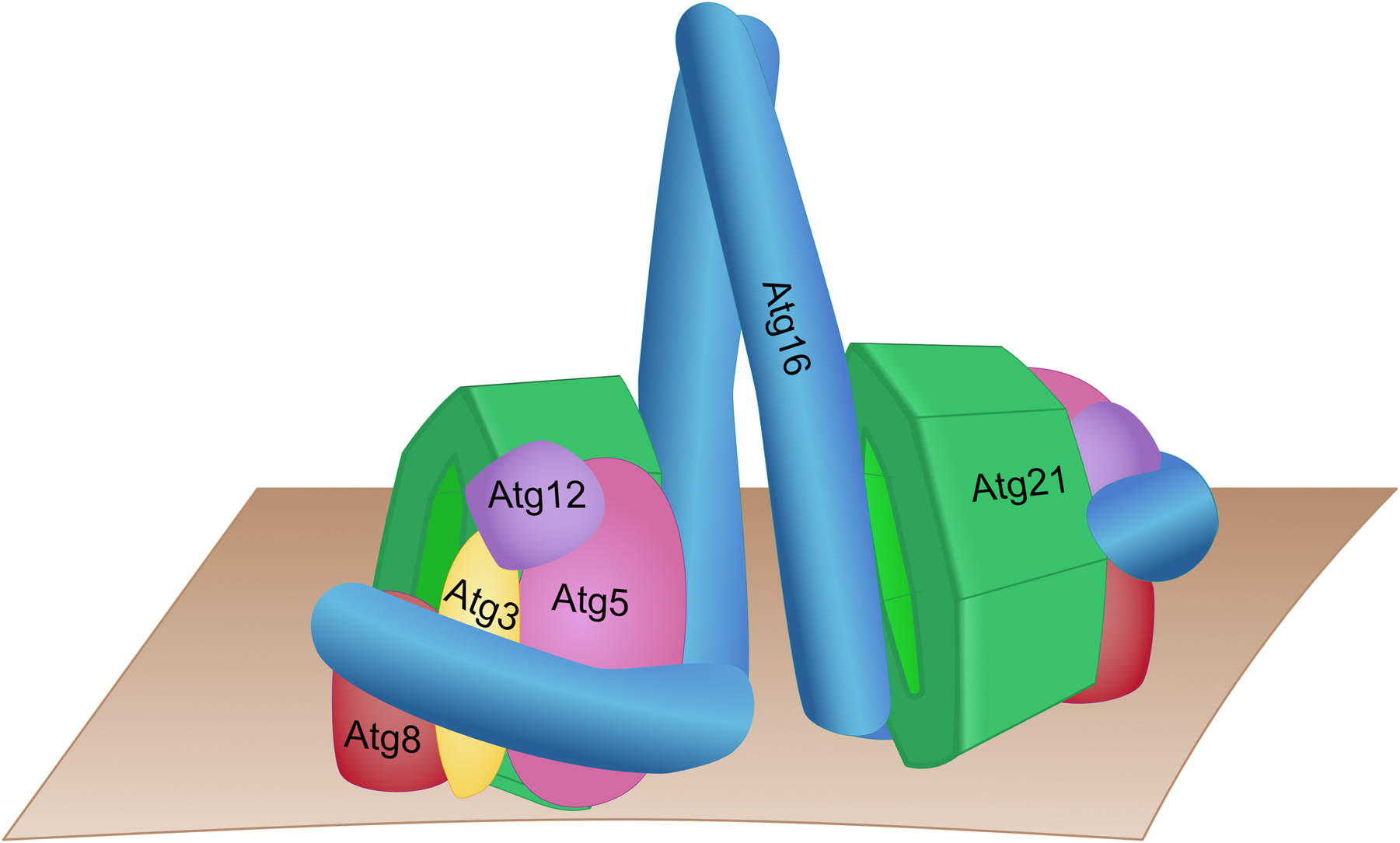

For autophagosome biogenesis in yeast few vesicles from the Golgi carrying the membrane protein Atg9 interact with a scaffolding complex containing Atg13, Atg11 and among others the serine/threonine kinase Atg1 to form a crescent-shaped double membraned phagophore (Sawa-Makarska et al. 2020). Interaction of vacuolar Vac8 with Atg13 or Atg11 for selective autophagy establishes a contact site of the phagophore with the vacuole (Gatica et al. 2021; Hollenstein et al. 2019, 2021; Munzel et al. 2021). This further leads to recruitment of a PI 3-kinase complex consisting of Vps34, Vps30, Vps15, Atg14 and Atg38. The PI3P then enables both Atg18 and Atg21 to localize to the PAS. Phagophore expansion requires the covalent coupling of the ubiquitin-like Atg8 to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) at the phagophore. For this, Atg8 is activated by the E1-enzyme Atg7. Activation of the E2-enzyme Atg3 further depends on an E3-complex, which is generated by covalent coupling of ubiquitin-like Atg12 to Atg5. The Atg12-Atg5 conjugate then dimerizes with the coiled-coil domain protein Atg16. Atg21 organizes Atg8 and the E2/E3-machinery at the phagophore vacuole contact and the structure of Atg21 in complex with the Atg16 coiled-coil domain was solved (Figure 2) (Juris et al. 2015; Munzel et al. 2021). Atg21 interacts with the larger bottom side of its β-propeller with the dimeric coiled-coil domain of Atg16. Atg8 further interacts with the top side of Atg21, which is required for efficient recruitment of Atg8 to the phagophore. Atg21 thus brings together the Atg16/Atg5-Atg12 E3-complex and Atg8, most likely coupled to Atg3. Since Atg21 binds two PI3P molecules at the phagophore membrane, it places Atg8 and its lipidation machinery in an orientation needed for coupling of Atg8 to PE (Figure 2). While Atg21 is typically required for selective types of autophagy, unselective bulk autophagy can proceed to some extend in its absence. This is most likely due to an alternate route of Atg8 lipidation. Indeed, Atg8 lipidation can also occur to some extent by direct interaction of Atg12 with the Atg1 kinase complex (Harada et al. 2019). Atg8-PE is distributed over the complete phagophore. On its outside it is expected to form a coat-like structure (Kaufmann et al. 2014), while on the inside it interacts with cargo receptors of selective autophagy.

Hypothetical model of the yeast Atg21 complex involved in Atg8-lipidation based on the structure of K. lactis Atg21 in complex with the coiled-coil domain of A. gossypii Atg16 (Munzel et al. 2021). Atg16 forms a complex with Atg5 and Atg12, acting as an E3 during Atg8 lipidation. Atg21 acts as a scaffold for recruiting Atg8 in conjugation with Atg3 to the top side of the PROPPIN (Juris et al. 2015).

Phagophore growth further requires a contact with the ER formed by a complex of the PI3P-adaptor Atg18, Atg2 and Atg9 (Obara et al. 2008; Rieter et al. 2013; Watanabe et al. 2012). Binding of Atg2 to Atg9 confines Atg2 to the phagophore edges and leads to interaction of Atg2 with Atg18. Complex stabilization is then achieved by both interaction of an amphipathic α-helix within the carboxyterminal domain of Atg2 with the phagophore membrane and by binding of Atg18 to PI3P at the phagophore. Furthermore, Atg2 tethers the phagophore with a domain at its amino-terminus to the ER (Chumpen Ramirez et al. 2022; Gomez-Sanchez et al. 2018; Kobayashi et al. 2012; Kotani et al. 2018). Establishment of this complex is essential for normal autophagy and phagophore elongation, since Atg2 mediates non-vesicular lipid transfer and the scramblase Atg9 delivers them to the inner membrane leaflet (Maeda et al. 2019, 2020; Matoba et al. 2020; Osawa et al. 2019; Valverde et al. 2019). The importance of this lipid flux for phagophore elongation is highlighted by the support of local lipid synthesis at the ER (Schutter et al. 2020). Hints for additional lipid transfer at the phagophore contact with the vacuole might come from the observation that phagophore elongation and formation of fully sized autophagic bodies was hampered in vac8∆ cells, which are affected in the formation of these contacts (Hollenstein et al. 2019; Munzel et al. 2021).

After phagophore closure Atg8 on the outside is removed by the proteinase Atg4. Furthermore, Atg9 is recycled to its post Golgi pool dependent on Atg18, either before or after fusion of the autophagosome with the vacuole. Atg18 thus plays a dual role in establishing the Atg2/Atg9 lipid transfer contacts and later in the retrograde transport of Atg9. Eventually, the matured autophagosome fuses with the vacuole depending on the autophagosomal SNARE Ykt6 (Barz et al. 2021; Gao et al. 2020; Kriegenburg et al. 2019).

While the roles of Atg18 and Atg21 during autophagosome formation are emerging, the function of the homologous Hsv2 remain elusive. Only a partial effect of Hsv2 was found on micronucleophagy (piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus, PMN), while both Atg18 and Atg21 were essential. During PMN induced by nitrogen-starvation the contact site between the vacuole and the nuclear envelope is degraded together with non-essential parts of the nucleus (Bo Otto and Thumm 2020; Krick et al. 2008; Otto and Thumm 2021). Furthermore, a role in the Golgi membrane associated degradation pathway (GOMED) has been reported (Yamaguchi et al. 2016, 2020). GOMED is induced by amphotericin B, which affects ergosterol homeostasis and thus Golgi to plasma membrane transport. This leads to swollen Golgi stacks and degradation of GFP-Sed5 and GFP-Gos1, SNARES involved in Golgi related traffic. GOMED appears to be an unconventional autophagy pathway targeting the abnormal Golgi stacks for vacuolar degradation. It depends on Atg1, but is independent from several autophagy proteins including Atg5, it is therefore typically monitored in atg5∆ cells. It has been found that upon amphotericin B treatment the autophagic marker GFP-Pho8∆60 is degraded in atg5∆ but not in atg5∆ hsv2∆ cells (Yamaguchi et al. 2020).

Mammalian cells possess the four PROPPINs WIPI1, WIPI2, WDR45B/WIPI3 and WDR45/WIPI4. WIPI2 supported by WIPI1 recruits the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 complex for lipidation of LC3 (a mammalian Atg8 orthologue) (Bakula et al. 2017; Dooley et al. 2015) and in this regard resemble Atg21. WIPI3 and WIPI4 are involved in autophagy regulation and phagophore elongation and can interact with the ATG2 proteins (Bakula et al. 2017; Ren et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2017). Mutations in the WIPI proteins especially in WIPI4 lead to diseases called β-propeller associated neurodegeneration (BPAN), SENDA (static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood) and NBIA5 (neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulations-5) (Cong et al. 2021; Vincent et al. 2021). Remarkably, crystal structures of the coiled-coil domain of human ATG16L1 in complex with WIPI2 (Strong et al. 2021) show an inverted orientation as compared to the coiled-coil domain of A. gossypii Atg16 together with K. lactis Atg21 (Munzel et al. 2021). This might be caused by structural differences between ATG16L1 and Atg16. For example, ATG16L1 has an additional carboxy-terminal WD40 domain required for LC3-associated phagocytosis but not canonical autophagy (Rai et al. 2019).

2.1 Non-autophagic roles of the PROPPINs

PROPPINs have beside their PI3P-dependent roles in autophagy additional non-autophagic functions. Atg18 negatively regulates the vacuolar PI3P 5-kinase Fab1 through interaction with Vac14 (Efe et al. 2007; Jin et al. 2008). It further functions in retrograde transport of the artificial cargo RS-ALP from the vacuole to the Golgi (Dove et al. 2004). The observed interaction of Atg18 with the myosin V-specific adaptor Vac17 could be related to this function, but this has not been shown so far (Efe et al. 2007). Atg18 and to a lesser extent Atg21 are further involved in vacuolar fragmentation upon hyperosmotic shock, which requires partial membrane insertion of the amphipathic α-helical loop 6CD located between the two PIP binding sites (Figure 1) (Busse et al. 2015; Gopaldass et al. 2017; Krick et al. 2008). Interestingly, mutations disturbing the amphipathic nature of this loop affected the membrane fission activity of Atg18, but not its autophagic function (Gopaldass et al. 2017). Comparatively, WIPI1 mediates recycling of the transferrin receptor to the plasma membrane and causes PI3P-dependent tubulation at endosomes, while their fission was PI(3,5)P2-dependent (De Leo et al. 2021). In line with these functions Atg18 and Atg21 are located at endosomes, the vacuole membrane and the phagophore. The large number of functions might be surprising, but β-propeller proteins are generally considered to act as scaffolds for the assembly of protein complexes.

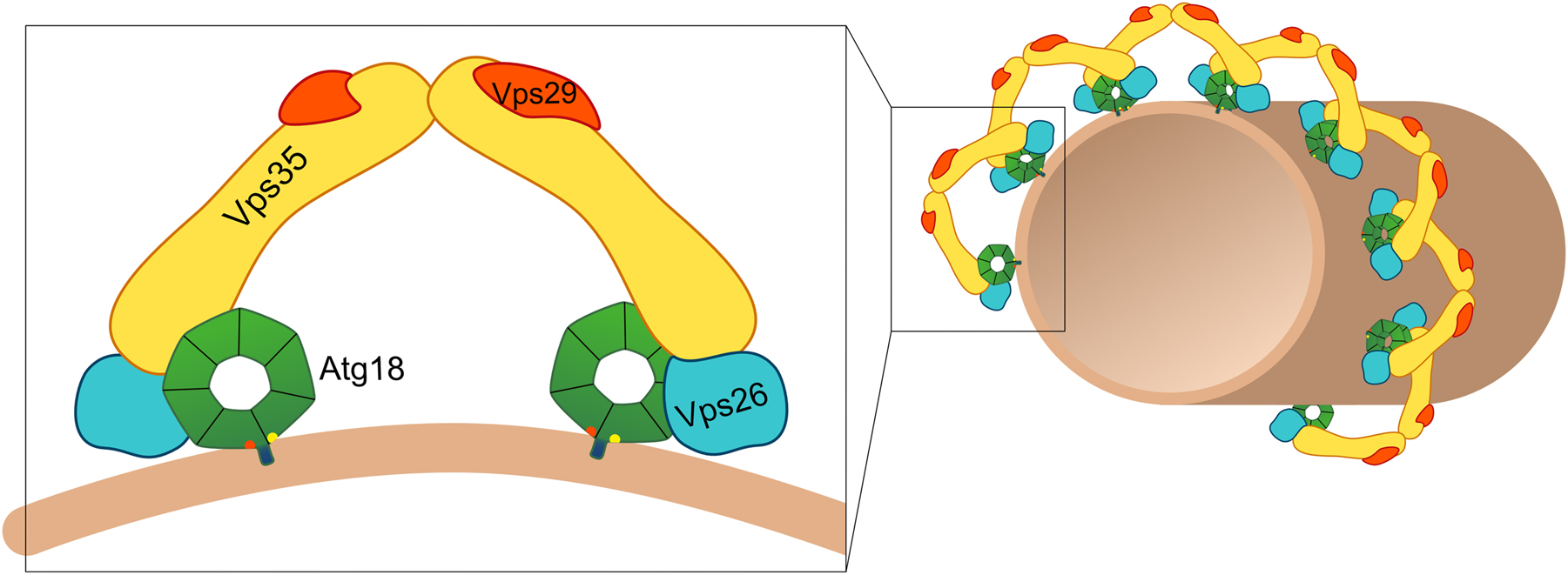

Another function of Atg18 might be related to the retromer complex, involved in endosomal sorting of membrane proteins. The proximity dependent labeling assay BioID allows the identification of proteins within the microenvironment of the bait proteins (Opitz et al. 2017; Roux et al. 2001). A recent study used this method to discover the novel Atg18-interactor Vps35 and confirmed the interaction by co-immunoprecipitation (Marquardt et al. 2023). Vps35 is part of the retromer complex involved in endosome to Golgi transport (Ma and Burd 2020). Together with Vps26 and Vps29, Vps35 forms an arch-like cargo selective complex (CSC or simply retromer). The CSC further interacts with the dimeric SNX-BAR sorting nexins Vps5 and Vps17, which can bind PI3P via their PX domain and confer membrane bending with the BAR domain. These retromer complexes assemble into a spiral coat and lead to membrane tubulation. Atg18 can bind to the membrane via its interaction with PI3P and is loop 6CD causes membrane bending, the PROPPIN could therefore replace SNX-BAR proteins functionally (Figure 3). Indeed, a competitive cross-talk was found between Atg18 and the sorting nexins. In the absence of Vps5 or Vps17 co-immunoprecipitation showed increased interaction of Atg18 with Vps35, while overexpression of Atg18 reduced the interaction of Vps35 with Vps5 (Marquardt et al. 2023). In line with the observed cross-talk between Atg18 and Vps5 or Vps17, overexpression of Vps5 inhibited vacuolar fragmentation.

Hypothetical model of the Atg18-retromer complex. Atg18 is thought to form an arch-like complex with Vps35, Vps26 and Vps29. The Atg18-retromer complexes then might assemble into a spiral coat and induce the formation of tubules and/or membrane fission.

One function of the novel Atg18-retromer complex is mediating vacuole fragmentation upon hyperosmotic shock. With 0.4 M NaCl atg18∆, vps26∆, vps29∆ and vps35∆ cells showed no normal vacuole fragmentation, whereas vps5∆ and vps17∆ cells had hyper-fragmented vacuoles (Marquardt et al. 2023). These findings were further complemented by an independent study, which additionally found that an Atg18-T56E mutant protein fails to interact with the CSC and lacks the vacuole fission activity (Courtellemont et al. 2022). Also, the analogous mammalian WIPI1-S69E failed to interact with the CSC and showed formation of long tubules out of endosomes, coupled with defects in recycling of the transferrin receptor. This suggests a role of a mammalian WIPI1-containing retromer complex in fission of endosomal transport carriers from endosomes (Courtellemont et al. 2022). However, the Atg18-retromer complex is not involved in the endosomal sorting of the known retromer cargo proteins Ear1 and Kex2, as their localization was not affected in the absence of the yeast PROPPINs (Marquardt et al. 2023). Interestingly, a mislocalization to the vacuolar lumen was found for the autophagic membrane protein Atg9 in vps35∆ cells, but not in vps5∆ cells. Indeed, co-immunoprecipitations uncovered an interaction of Atg9 with Vps35, independent of the presence of either Atg18 or Atg2. The interaction was further confirmed using the split-ubiquitin system, an assay similar to the 2-hybrid system but better suited for membrane proteins (Muller and Johnsson 2008). Consistent with a putative role of Atg18-retromer in recycling of Atg9 to its post-Golgi pool vps35∆, but not vps5∆ or vps17∆ cells showed a reduced autophagy rate (Marquardt et al. 2023). If the above mentioned Atg18-dependent retrograde sorting of RS-ALP also depends on Atg18-retromer is unclear at the moment.

About 20 years after uncovering the role of the S. cerevisiae PROPPINs in autophagic processes their molecular functions begin to emerge. Nevertheless, many questions remain open and need to be addressed in future research. Indeed, a so far not peer-reviewed study suggests that isolated Atg18 reconstituted with PI(3,5)P2-containg LUVs forms dimers bridging two membranes (Mann et al. 2022).This could indicate a role of Atg18 not only as platform for protein protein interactions, but also in organizing membrane contact sites.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: SFB860

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: Support was received from the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) within the SFB860 project B04.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Bakula, D., Muller, A.J., Zuleger, T., Takacs, Z., Franz-Wachtel, M., Thost, A.K., Brigger, D., Tschan, M.P., Frickey, T., Robenek, H., et al.. (2017). WIPI3 and WIPI4 beta-propellers are scaffolds for LKB1-AMPK-TSC signalling circuits in the control of autophagy. Nat. Commun. 8: 15637, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15637.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Barth, H., Meiling-Wesse, K., Epple, U.D., and Thumm, M. (2001). Autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway both require Aut10p. FEBS Lett. 508: 23–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03016-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Barth, H. and Thumm, M. (2001). A genomic screen identifies AUT8 as a novel gene essential for autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 274: 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00614-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Barz, S., Kriegenburg, F., Sanchez-Martin, P., and Kraft, C. (2021). Small but mighty: atg8s and Rabs in membrane dynamics during autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1868: 119064, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.119064.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Baskaran, S., Ragusa, M.J., Boura, E., and Hurley, J.H. (2012). Two-site recognition of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate by PROPPINs in autophagy. Mol. Cell 47: 339–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bo Otto, F. and Thumm, M. (2020). Nucleophagy-implications for microautophagy and health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21: 4506, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124506.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Busse, R.A., Scacioc, A., Krick, R., Perez-Lara, A., Thumm, M., and Kuhnel, K. (2015). Characterization of PROPPIN-phosphoinositide binding and role of loop 6CD in PROPPIN-membrane binding. Biophys. J. 108: 2223–2234, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.045.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chumpen Ramirez, S., Gomez-Sanchez, R., Verlhac, P., Hardenberg, R., Margheritis, E., Cosentino, K., Reggiori, F., and Ungermann, C. (2022). Atg9 interactions via its transmembrane domains are required for phagophore expansion during autophagy. Autophagy 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2136340.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cong, Y., So, V., Tijssen, M.A.J., Verbeek, D.S., Reggiori, F., and Mauthe, M. (2021). WDR45, one gene associated with multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Autophagy 17: 3908–3923, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2021.1899669.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Courtellemont, T., De Leo, M.G., Gopaldass, N., and Mayer, A. (2022). CROP: a retromer-PROPPIN complex mediating membrane fission in the endo-lysosomal system. EMBO J. 41: e109646, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2021109646.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

De Leo, M.G., Berger, P., and Mayer, A. (2021). WIPI1 promotes fission of endosomal transport carriers and formation of autophagosomes through distinct mechanisms. Autophagy 17: 3644–3670, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2021.1886830.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Dooley, H.C., Wilson, M.I., and Tooze, S.A. (2015). WIPI2B links PtdIns3P to LC3 lipidation through binding ATG16L1. Autophagy 11: 190–191, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2014.996029.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Dove, S.K., Piper, R.C., McEwen, R.K., Yu, J.W., King, M.C., Hughes, D.C., Thuring, J., Holmes, A.B., Cooke, F.T., Michell, R.H., et al.. (2004). Svp1p defines a family of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate effectors. EMBO J. 23: 1922–1933, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Efe, J.A., Botelho, R.J., and Emr, S.D. (2007). Atg18 regulates organelle morphology and Fab1 kinase activity independent of its membrane recruitment by phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate. Mol. Biol. Cell 18: 4232–4244, https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e07-04-0301.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gao, J., Kurre, R., Rose, J., Walter, S., Frohlich, F., Piehler, J., Reggiori, F., and Ungermann, C. (2020). Function of the SNARE Ykt6 on autophagosomes requires the Dsl1 complex and the Atg1 kinase complex. EMBO Rep. 21: e50733, https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050733.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gatica, D., Wen, X., Cheong, H., and Klionsky, D.J. (2021). Vac8 determines phagophore assembly site vacuolar localization during nitrogen starvation-induced autophagy. Autophagy 17: 1636–1648, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2020.1776474.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gomez-Sanchez, R., Rose, J., Guimaraes, R., Mari, M., Papinski, D., Rieter, E., Geerts, W.J., Hardenberg, R., Kraft, C., Ungermann, C., et al.. (2018). Atg9 establishes Atg2-dependent contact sites between the endoplasmic reticulum and phagophores. J. Cell Biol. 217: 2743–2763, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201710116.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gopaldass, N., Fauvet, B., Lashuel, H., Roux, A., and Mayer, A. (2017). Membrane scission driven by the PROPPIN Atg18. EMBO J. 36: 3274–3291, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201796859.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Guan, J., Stromhaug, P.E., George, M.D., Habibzadegah-Tari, P., Bevan, A., Dunn, W.A.Jr., and Klionsky, D.J. (2001). Cvt18/Gsa12 is required for cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport, pexophagy, and autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 3821–3838, https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.12.12.3821.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Harada, K., Kotani, T., Kirisako, H., Sakoh-Nakatogawa, M., Oikawa, Y., Kimura, Y., Hirano, H., Yamamoto, H., Ohsumi, Y., and Nakatogawa, H. (2019). Two distinct mechanisms target the autophagy-related E3 complex to the pre-autophagosomal structure. eLife 8: 685, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.43088.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Hollenstein, D.M., Gomez-Sanchez, R., Ciftci, A., Kriegenburg, F., Mari, M., Torggler, R., Licheva, M., Reggiori, F., and Kraft, C. (2019). Vac8 spatially confines autophagosome formation at the vacuole in S. cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 132: jcs235002, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.235002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Hollenstein, D.M., Licheva, M., Konradi, N., Schweida, D., Mancilla, H., Mari, M., Reggiori, F., and Kraft, C. (2021). Spatial control of avidity regulates initiation and progression of selective autophagy. Nat. Commun. 12: 7194, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27420-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Hu, Y. and Reggiori, F. (2022). Molecular regulation of autophagosome formation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50: 55–69, https://doi.org/10.1042/bst20210819.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Jin, N., Chow, C.Y., Liu, L., Zolov, S.N., Bronson, R., Davisson, M., Petersen, J.L., Zhang, Y., Park, S., Duex, J.E., et al.. (2008). VAC14 nucleates a protein complex essential for the acute interconversion of PI3P and PI(3,5)P(2) in yeast and mouse. EMBO J. 27: 3221–3234, https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2008.248.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Juris, L., Montino, M., Rube, P., Schlotterhose, P., Thumm, M., and Krick, R. (2015). PI3P binding by Atg21 organises Atg8 lipidation. EMBO J. 34: 955–973, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201488957.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kaufmann, A., Beier, V., Franquelim, H.G., and Wollert, T. (2014). Molecular mechanism of autophagic membrane-scaffold assembly and disassembly. Cell 156: 469–481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Klionsky, D.J., Petroni, G., Amaravadi, R.K., Baehrecke, E.H., Ballabio, A., Boya, P., Bravo-San Pedro, J.M., Cadwell, K., Cecconi, F., Choi, A.M.K., et al.. (2021). Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 40: e108863, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2021108863.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kobayashi, T., Suzuki, K., and Ohsumi, Y. (2012). Autophagosome formation can be achieved in the absence of Atg18 by expressing engineered PAS-targeted Atg2. FEBS Lett. 586: 2473–2478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Kotani, T., Kirisako, H., Koizumi, M., Ohsumi, Y., and Nakatogawa, H. (2018). The Atg2-Atg18 complex tethers pre-autophagosomal membranes to the endoplasmic reticulum for autophagosome formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 10363–10368, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806727115.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Krick, R., Busse, R.A., Scacioc, A., Stephan, M., Janshoff, A., Thumm, M., and Kuhnel, K. (2012). Structural and functional characterization of the two phosphoinositide binding sites of PROPPINs, a β-propeller protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E2042–E2049, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1205128109.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Krick, R., Henke, S., Tolstrup, J., and Thumm, M. (2008). Dissecting the localization and function of Atg18, Atg21 and Ygr223c. Autophagy 4: 896–910, https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.6801.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Kriegenburg, F., Bas, L., Gao, J., Ungermann, C., and Kraft, C. (2019). The multi-functional SNARE protein Ykt6 in autophagosomal fusion processes. Cell Cycle 18: 639–651, https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2019.1580488.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lei, Y., Tang, D., Liao, G., Xu, L., Liu, S., Chen, Q., Li, C., Duan, J., Wang, K., Wang, J., et al.. (2021). The crystal structure of Atg18 reveals a new binding site for Atg2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78: 2131–2143, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03621-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Liang, R., Ren, J., Zhang, Y., and Feng, W. (2019). Structural conservation of the two phosphoinositide-binding sites in WIPI proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 431: 1494–1505, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Ma, M. and Burd, C.G. (2020). Retrograde trafficking and plasma membrane recycling pathways of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Traffic 21: 45–59, https://doi.org/10.1111/tra.12693.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Maeda, S., Otomo, C., and Otomo, T. (2019). The autophagic membrane tether ATG2A transfers lipids between membranes. eLife 8, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.45777.Suche in Google Scholar

Maeda, S., Yamamoto, H., Kinch, L.N., Garza, C.M., Takahashi, S., Otomo, C., Grishin, N.V., Forli, S., Mizushima, N., and Otomo, T. (2020). Structure, lipid scrambling activity and role in autophagosome formation of ATG9A. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27: 1194–1201, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-00520-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mann, D., Fromm, S.A., Martinez-Sanchez, A., Gopaldass, N., Mayer, A. and Sachse, C. (2022). Structural plasticity of Atg18 oligomers: organization of assembled tubes and scaffolds at the isolation membrane. BioRxiv 2022.2007.2026.501514.10.1101/2022.07.26.501514Suche in Google Scholar

Marquardt, L., Taylor, M., Kramer, F., Schmitt, K., Braus, G.H., Valerius, O., and Thumm, M. (2023). Vacuole fragmentation depends on a novel Atg18-containing retromer-complex. Autophagy 19: 278–295, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2072656.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Matoba, K., Kotani, T., Tsutsumi, A., Tsuji, T., Mori, T., Noshiro, D., Sugita, Y., Nomura, N., Iwata, S., Ohsumi, Y., et al.. (2020). Atg9 is a lipid scramblase that mediates autophagosomal membrane expansion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 35: 453–459, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-00518-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Meiling-Wesse, K., Barth, H., Voss, C., Eskelinen, E.L., Epple, U.D., and Thumm, M. (2004). Atg21 is required for effective recruitment of Atg8 to the preautophagosomal structure during the Cvt pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 37741–37750, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m401066200.Suche in Google Scholar

Muller, J. and Johnsson, N. (2008). Split-ubiquitin and the split-protein sensors: chessman for the endgame. Chembiochem 9: 2029–2038, https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.200800190.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Munzel, L., Neumann, P., Otto, F.B., Krick, R., Metje-Sprink, J., Kroppen, B., Karedla, N., Enderlein, J., Meinecke, M., Ficner, R., et al.. (2021). Atg21 organizes Atg8 lipidation at the contact of the vacuole with the phagophore. Autophagy 17: 1458–1478, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2020.1766332.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Obara, K., Sekito, T., Niimi, K., and Ohsumi, Y. (2008). The Atg18-Atg2 complex is recruited to autophagic membranes via phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and exerts an essential function. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 23972–23980, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m803180200.Suche in Google Scholar

Opitz, N., Schmitt, K., Hofer-Pretz, V., Neumann, B., Krebber, H., Braus, G.H., and Valerius, O. (2017). Capturing the Asc1p/receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) microenvironment at the head region of the 40S ribosome with quantitative BioID in yeast. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16: 2199–2218, https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.m116.066654.Suche in Google Scholar

Osawa, T., Kotani, T., Kawaoka, T., Hirata, E., Suzuki, K., Nakatogawa, H., Ohsumi, Y., and Noda, N.N. (2019). Atg2 mediates direct lipid transfer between membranes for autophagosome formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26: 281–288, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-019-0203-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Otto, F.B. and Thumm, M. (2021). Mechanistic dissection of macro- and micronucleophagy. Autophagy 17: 626–639, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2020.1725402.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rai, S., Arasteh, M., Jefferson, M., Pearson, T., Wang, Y., Zhang, W., Bicsak, B., Divekar, D., Powell, P.P., Naumann, R., et al.. (2019). The ATG5-binding and coiled coil domains of ATG16L1 maintain autophagy and tissue homeostasis in mice independently of the WD domain required for LC3-associated phagocytosis. Autophagy 15: 599–612, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2018.1534507.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Reggiori, F., Tucker, K.A., Stromhaug, P.E., and Klionsky, D.J. (2004). The Atg1-Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre-autophagosomal structure. Dev. Cell 6: 79–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00402-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Ren, J., Liang, R., Wang, W., Zhang, D., Yu, L., and Feng, W. (2020). Multi-site-mediated entwining of the linear WIR-motif around WIPI β-propellers for autophagy. Nat. Commun. 11: 2702, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16523-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rieter, E., Vinke, F., Bakula, D., Cebollero, E., Ungermann, C., Proikas-Cezanne, T., and Reggiori, F. (2013). Atg18 function in autophagy is regulated by specific sites within its β-propeller. J. Cell Sci. 126: 593–604, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.115725.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Roux, K.J., Kim, D.I., and Burke, B. (2001). BioID: a screen for protein–protein interactions. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.Suche in Google Scholar

Sawa-Makarska, J., Baumann, V., Coudevylle, N., von Bulow, S., Nogellova, V., Abert, C., Schuschnig, M., Graef, M., Hummer, G., and Martens, S. (2020). Reconstitution of autophagosome nucleation defines Atg9 vesicles as seeds for membrane formation. Science 369: eaaz7714–7712, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz7714.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Scacioc, A., Schmidt, C., Hofmann, T., Urlaub, H., Kuhnel, K., and Perez-Lara, A. (2017). Structure based biophysical characterization of the PROPPIN Atg18 shows Atg18 oligomerization upon membrane binding. Sci. Rep. 7: 14008, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14337-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schutter, M., Giavalisco, P., Brodesser, S., and Graef, M. (2020). Local fatty acid channeling into phospholipid synthesis drives phagophore expansion during autophagy. Cell 180: 135–149. e114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Stromhaug, P.E., Reggiori, F., Guan, J., Wang, C.W., and Klionsky, D.J. (2004). Atg21 is a phosphoinositide binding protein required for efficient lipidation and localization of Atg8 during uptake of aminopeptidase I by selective autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 3553–3566, https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e04-02-0147.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Strong, L.M., Chang, C., Riley, J.F., Boecker, C.A., Flower, T.G., Buffalo, C.Z., Ren, X., Stavoe, A.K., Holzbaur, E.L., and Hurley, J.H. (2021). Structural basis for membrane recruitment of ATG16L1 by WIPI2 in autophagy. eLife 10: 1–23, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.70372.Suche in Google Scholar

Valverde, D.P., Yu, S., Boggavarapu, V., Kumar, N., Lees, J.A., Walz, T., Reinisch, K.M., and Melia, T.J. (2019). ATG2 transports lipids to promote autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 218: 1787–1798, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201811139.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Vincent, O., Anton-Esteban, L., Bueno-Arribas, M., Tornero-Ecija, A., Navas, M.A., and Escalante, R. (2021). The WIPI gene family and neurodegenerative diseases: insights from yeast and Dictyostelium models. Front Cell Dev Biol 9: 737071, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.737071.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Watanabe, Y., Kobayashi, T., Yamamoto, H., Hoshida, H., Akada, R., Inagaki, F., Ohsumi, Y., and Noda, N.N. (2012). Structure-based analyses reveal distinct binding sites for Atg2 and phosphoinositides in Atg18. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 31681–31690, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m112.397570.Suche in Google Scholar

Yamaguchi, H., Arakawa, S., Kanaseki, T., Miyatsuka, T., Fujitani, Y., Watada, H., Tsujimoto, Y., and Shimizu, S. (2016). Golgi membrane-associated degradation pathway in yeast and mammals. EMBO J. 35: 1991–2007, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201593191.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Yamaguchi, H., Honda, S., Torii, S., Shimizu, K., Katoh, K., Miyake, K., Miyake, N., Fujikake, N., Sakurai, H.T., Arakawa, S., et al.. (2020). Wipi3 is essential for alternative autophagy and its loss causes neurodegeneration. Nat. Commun. 11: 5311, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18892-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Yamamoto, H., Zhang, S., and Mizushima, N. (2023). Autophagy genes in biology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00562-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Zheng, J.-X., Li, Y., Ding, Y.-H., Liu, J.-J., Zhang, M.-J., Dong, M.-Q., Wang, H.-W., and Yu, L. (2017). Architecture of the ATG2B-WDR45 complex and an aromatic Y/HF motif crucial for complex formation. Autophagy 13: 0–14, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2017.1359381.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Integrative Structural Biology of Dynamic Macromolecular Assemblies

- Highlight: integrative structural biology of dynamic macromolecular assemblies

- Bayesian methods in integrative structure modeling

- The many faces of ribosome translocation along the mRNA: reading frame maintenance, ribosome frameshifting and translational bypassing

- Translation termination in human mitochondria – substrate specificity of mitochondrial release factors

- Molecular functions of RNA helicases during ribosomal subunit assembly

- Interaction of nucleoporins with nuclear transport receptors: a structural perspective

- Protein transport along the presequence pathway

- Autophagic and non-autophagic functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PROPPINs Atg18, Atg21 and Hsv2

- Influence of phosphorylation on intermediate filaments

- Mediator structure and function in transcription initiation

- Structure and phase separation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II

- The DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp5 is a key protein that couples multiple steps in gene expression

- Structure and function of spliceosomal DEAH-box ATPases

- Molecular simulations of DEAH-box helicases reveal control of domain flexibility by ligands: RNA, ATP, ADP, and G-patch proteins

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Integrative Structural Biology of Dynamic Macromolecular Assemblies

- Highlight: integrative structural biology of dynamic macromolecular assemblies

- Bayesian methods in integrative structure modeling

- The many faces of ribosome translocation along the mRNA: reading frame maintenance, ribosome frameshifting and translational bypassing

- Translation termination in human mitochondria – substrate specificity of mitochondrial release factors

- Molecular functions of RNA helicases during ribosomal subunit assembly

- Interaction of nucleoporins with nuclear transport receptors: a structural perspective

- Protein transport along the presequence pathway

- Autophagic and non-autophagic functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PROPPINs Atg18, Atg21 and Hsv2

- Influence of phosphorylation on intermediate filaments

- Mediator structure and function in transcription initiation

- Structure and phase separation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II

- The DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp5 is a key protein that couples multiple steps in gene expression

- Structure and function of spliceosomal DEAH-box ATPases

- Molecular simulations of DEAH-box helicases reveal control of domain flexibility by ligands: RNA, ATP, ADP, and G-patch proteins