Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has quickly spread all over the world. In this respect, traditional medicinal chemistry, repurposing, and computational approaches have been exploited to develop novel medicines for treating this condition. The effectiveness of chemicals and testing methods in the identification of new promising therapies, and the extent of preparedness for future pandemics, have been further highly advantaged by recent breakthroughs in introducing noble small compounds for clinical testing purposes. Currently, numerous studies are developing small-molecule (SM) therapeutic products for inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication, as well as managing the disease-related outcomes. Transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2)-inhibiting medicinal products can thus prevent the entry of the SARS-CoV-2 into the cells, and constrain its spreading along with the morbidity and mortality due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), particularly when co-administered with inhibitors such as chloroquine (CQ) and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH). The present review demonstrates that the clinical-stage therapeutic agents, targeting additional viral proteins, might improve the effectiveness of COVID-19 treatment if applied as an adjuvant therapy side-by-side with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been documented as the origin of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (Aghamollaei et al. 2021; Hosseini et al. 2021; Nejad et al. 2021; Mirzaie et al. 2020; Sheikhshahrokh et al. 2020). At this time, over 630 million individuals have been infected, and more than 6.5 million cases have lost their lives due to the virus across the world. Besides, the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the global economy (Halaji et al. 2020; Heiat et al. 2021a; Ranjbar et al. 2020; WHO 2022). As a virus enveloped with a positive non-segmented single-stranded ribonucleic acid (ssRNA) genome, the SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the family β-coronaviridae, similar to the SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Allahyari et al. 2021; Kaul 2020; Mirzaei et al. 2020; Mohammadpour et al. 2021; Torabi et al. 2020). However, the variant concerned is much more infectious than the SARS-CoV or the MERS-CoV, as evidenced in epidemiological research (Cui et al. 2019; Marra et al. 2003; Ruan et al. 2003). In this regard, the tactics improved for reducing and managing the COVID-19 incidence are immediately needed.

Of note, the four main structural proteins, i.e., spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N), are the primary ones expressed by the SARS-CoV-2. The crucial step for the entry of the SARS-CoV-2 into the host cells is the attachment of the S protein to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (Heiat et al. 2021b; Torre-Fuentes et al. 2021; Vankadari 2020). Moreover, the virus entrance into the host cells is further facilitated by the interaction of the S protein with the cellular transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2). As a result, the ACE2 and the TMPRSS2 can be utilized as the pharmaceutical targets to protect cells against the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Such medicines can be designed based on non-structural proteins (NSPs), such as the 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and the papain-like protease (PLpro), encoded by the SARS-CoV-2, which contribute to in viral replication (Elhusseiny et al. 2020; Nittari et al. 2020). In accordance with clinical and preclinical trials, small-molecule (SM) medicines, including lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r), chloroquine (CQ), remdesivir (RDV), arbidol (ARB), ribavirin/favipiravir, and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) have so far proved effective. The structural properties, targets, pharmacological activities, and adverse responses of the known SM medicines against the SARS-CoV-2 were thus retrieved and analyzed in this review.

SARS-CoV-2: from structure to pathology

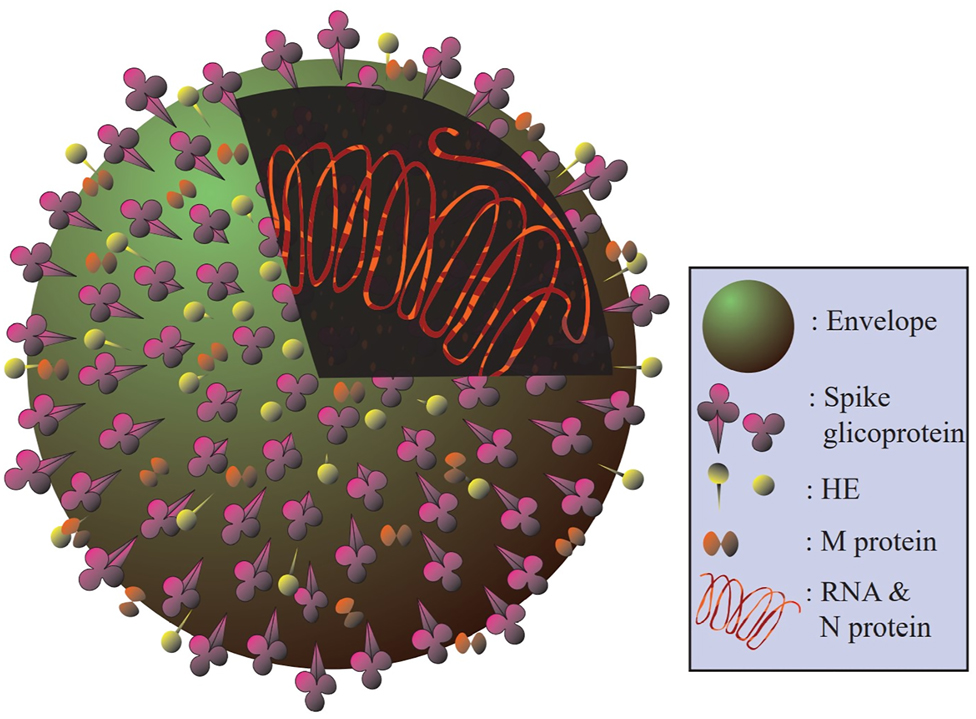

Considering its pleomorphism, the SARS-CoV-2 has a size range of 60–140 nm. The peplos generated from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or the Golgi cisternae membranes also envelope the virion. Other glycoproteins and conspicuous S proteins (Figure 1) also cross the peplos (viz., E, M). The nucleocapsid, characterized as the virion central body (i.e., N), further houses the genome and the phosphorylated nucleoprotein, and is also surrounded by the peplos. The genome is between 26 and 32 kb in size, and the SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequence is 80% homological with the SARS-CoV genome and 96–98% homological with the bat-derived virus genome (Grifoni et al. 2020). Notably, the SARS-CoV spreads via infecting its intermediate hosts, such as bats and the African civet (or Civettictis civetta) (Lu et al. 2015). Some hypotheses have been accordingly proposed for the SARS-CoV-2 transition from an animal host to humans, while none of them have been approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) to this point. Pangolin has been similarly assumed to be the intermediate host enabling the transfer of the SARS-CoV2 from the bat to the human, owing to its high homology with the bat-derived virus, and to a lesser extent, with the pangolin-derived CoV. Moreover, the SARS-CoV-2 has the same six amino acid residues in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S ligand as the virus obtained from pangolin. However, the pangolin-isolated virus is not genomically identical to the SARS-CoV-2, since it lacks the furin-sensitive polybasic site (Andersen and Rambaut 2020).

The molecular structure of a virion. The S protein, as the most visible on the virion surface, represents the CoV appearance. The peplos of the transmembrane M protein is also very hydrophobic, and has three domains. The peplos contains a little amount of the E glycoprotein. Of note, the protein called hemagglutinin-esterase (HE) is found in some strains of the CoV.

The oropharyngeal epithelial cells (ECs) and the upper respiratory tract (URT) ones are the common sites of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. According to epidemiological studies, COVID-19 has an average incubation time of 3–7 days. Nevertheless, it can last from 0 to 24 days, based on the rate of infection and immunological reactivity. A large percentage of respiratory viral infections are also asymptomatic, or characterized by mild to severe influenza-like symptoms, and caused by exposure to a limited number of virus particles (Totura and Baric 2012). Fever, fatigue, and a dry cough are the most reported clinical signs, while nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, pharyngeal pain, myalgia, and diarrhea occur to a lesser extent. Besides, the asymptomatic or relatively mild infections are more frequently experienced in children. Some believe that this age group forms an immunological memory from the common cold, induced by the coronavirus infection more effectively, and others deem that the cellular innate immune response is raised by the attenuated bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) or measles vaccines. The incubation period is also brief in vulnerable individuals with underlying pathology, immunodeficiency, and other conditions, like biological aging, with 15% of the infected cases proceeding to the severe form (Shi et al. 2020).

The common stages of the SARS-CoV-2 infection are as follows: (1) the asymptomatic incubation period, with the genomic test positive or negative; (2) the mild-symptom period with the genomic test positive; and (3) the severe-symptom stage with high viral concentration.

The viral infection also spreads from the URT to the ECs in the bronchial trees at the severe stages. As well, the SARS-CoV2 attacks the pulmonary alveolar ECs via the RBD to the ACE2 in cases with pre-existing medical conditions. Of note, the alveoli consist of two types of ECs, viz., squamous pneumocytes and pneumocytes, type I and II, releasing a phospholipid mixture that reduces the surface tension of the molecular water and avoids their collapse. Lung injury repair is typically facilitated by the alveoli type II. In the case of infection, the lung response is thus impaired, and the respiratory problems are exacerbated due to the high loads of the ACE2 in these cells (Guillot et al. 2013). Furthermore, the viral proliferation, caused by the cellular lysis, might result in the release of the cytoplasmic materials, which help accelerate the inflammatory response and pyroptosis. While some alveolar macrophages extend into the alveoli, others freely move in the alveolar space.

Dyspnea and hypoxemia (or pneumonia) are also common in the severe cases during the second or third weeks following being infected. The acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, acidosis, hemorrhage and coagulation dysfunctions, thrombocytopenia, tachycardia, and hyperbilirubinemia due to multiple vital organ failures, decreased diuresis, and impaired cognitive functions, which can all occur in a fast process in critical cases (Gralinski et al. 2018). Mild fever or a normal temperature can be further observed in patients at the advanced stages of the disease. The elderly and those suffering from chronic illnesses might have a bad prognosis. Low partial blood oxygen saturation (SpO2, 92%) and distinctive radiological images are thus the strong markers of viral pneumonia. The lung radiological image at the early stages of the COVID-19 infection accordingly shows the peripheral and posterior basal regions of infiltrative opacification. Infiltrates (containing monocytes/macrophages) also grow in both lungs as the disease advances, resulting in pleural effusion and opaque glass-like consolidations. Moreover, lymphopenia (particularly, the natural killer [NK] cells), leukopenia, and inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) are observed at the elevated levels, while the procalcitonin values remain normal (Huang et al. 2020).

Multiple tiny patched shadows along with interstitial alterations might be further seen on radiographs, mainly in the peripheral regions. Patients also develop numerous ground glass (GG)-like and infiltration shadows in both lungs as the disease progresses. Lung consolidation may correspondingly occur in the extreme situations, while pleural effusion is observed to a lesser extent (Zu et al. 2020).

Hyaluronic acid, synthesized at a rapid rate in the lungs, is also found in the alveolar fluid. In ECs and fibroblasts, the increased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF respectively enhance the hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2) activities. Since hyaluronic acid is hydrated 1000 times more than its molecular weight, the liquid component released in the alveoli is viscous, and fails to invade the systemic circulation. As a result, the viscous lung exudate is proposed to be possibly removed using the hyaluronidase as a treatment (Shi et al. 2020).

Besides, the atrophy of the spleen and the lymph nodes, the functional depletion of the T lymphocytes, the decrease at the Th and Ts lymphocyte levels, together with some other immune system (IS) dysfunctions can be observed in the SARS-CoV-2-infected cases, particularly in the more advanced ones. Unlike the proportion of the memory Th and T regulatory lymphocytes, that of the naive Th cells rises in the case of infection (Zu et al. 2020). The levels of the lactose dehydrogenase (LDH), the liver enzymes, the muscle enzymes, and the myoglobin may be a bit elevated in some cases. Originating from the plasmin-induced breakdown of fibrin, troponin and D-dimers can be also observed at the higher levels in the advanced cases. In addition, there have been some reports of vasculitis (including, endothelial lesions, alveolar septal vessel congestion, small vessel wall thickening, lumen stenosis, and occlusion), hypercoagulation with the hypoxic gangrene of the extremities, and multi-organ lesions in the lungs, heart, liver, and kidneys, characterized by the local hemorrhagic necrosis (Zu et al. 2020).

From a clinical standpoint, it becomes clear that there is a complicated condition involving the upper and lower respiratory symptoms along with the digestive issues. Some patients, mainly those at the minor ages also experience the digestive issues under unknown mechanisms. However, there are speculations that the distribution of the ACE2 receptors can be contributing. Another fascinating point is that many young people unknowingly suffer from hyposmia. COVID-19 patients have also been found to develop dysgeusia/hypogeusia/ageusia, that is to say, the taste sensation can be either distorted, reduced, or completely lost (Bocksberger et al. 2020). The patient’s sense of smell then deteriorates over time similar to the influenza cases, and the infection spreads unnoticed until the taste loss occurs. This indicates that the virus has the ability to infect only the neurons in the olfactory nerve, with no accompanying URT symptoms. Overall, the respiratory system-infecting viruses can lead to the smell sensation loss. Notably, there are over 200 viruses, 15% of which are from the family coronaviridae, that cause respiratory infections.

Containing the infection spread during the asymptomatic stage is of great value, which is impaired in cases with hyposmia, since they fail to notice the subtle alternations in the smell sensation. A large-scale public awareness campaign regarding the probable symptoms can be thus effective as a screening tool to identify the infected individuals. As a result, it is still unclear how each case reacts to the SARS-Cov-2 infection. In this respect, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test has been accordingly performed at several hospitals during the lockdown for screening as an initial assessment. Quite a few patients have also been found to be positive. The personal observations here have established that COVID-19 has been fully asymptomatic in patients with types of cancer, as an immunosuppressive condition.

SM metabolites and SARS-CoV-2 treatment

Kinase inhibitors

So far, the in vitro cell-based investigations have suggested that the ABL kinase inhibitors suppress the replications of various other viruses at different phases of their lifecycles, including the Coxsackie, dengue, Ebola, and vaccinia viruses (Clark et al. 2016; Coyne and Bergelson 2006; García et al. 2012; Newsome et al. 2006; Reeves et al. 2011). In this line, when the Coxsackie virus adheres to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein decay-accelerating factor (DAF) on the apical cell surface, the ABL kinase inhibitor is activated, which then induces the Rac-dependent actin reassembly, forming the virus-induced tight junctions (Coyne and Bergelson 2006). The ABL kinase inhibitors, imatinib and dasatinib, have been further found to reduce both the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV replications, while nilotinib can solely inhibit the SARS-CoV replication, in vitro (Dyall et al. 2014). The early phases of the life of the virus, as well as the viral replication, have also been inhibited by preventing the coronavirus virion fusion with the endosomal membrane, indicated by the mode of action of imatinib against the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV (Coleman et al. 2016; Sisk et al. 2018). To note, knocking down the ABL2, but not the ABL1, can greatly reduce the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV replication and entrance in vitro (Coleman et al. 2016). The fact that the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV need high doses, but not the toxic levels, of imatinib and dasatinib, may lie in the experimental factors, such as drug resistance in the cell lines, which boosts the virus propagation (Coleman et al. 2016; Dyall et al. 2014). Therefore, the optimal dosing requires in vivo testing to be effectively determined. Importantly, antiviral efficacy is cell-type-dependent in many cell-based experiments evaluating the effects of medicines on virus titer, and strain-dependent variability can be also observed in viruses. Imatinib, among 17 other Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medicines, similar in terms of the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV, suppresses the SARS-CoV-2 in vitro, according to the recent preprints (BioRxiv 2020). Virus replication has been further linked to some SRC family of protein tyrosine kinases (SFKs), including those linked to the SARS-CoV-2 or other different viruses. At the μM range doses and the early initial lifecycle stages of the virus, the MERS-CoV is comparably shown to be suppressed by the ABL/SRC inhibitor saracatinib (Shin et al. 2018). It is implied that the SRC family proteins, LYN and FYN, are necessary for the MERS-CoV replication, since the suppression of their associated small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) has resulted in large reductions in the MERS-CoV titer (Shin et al. 2018). The FYN is also associated with the Coxsackie virus entry via the epithelial tight junctions (Coyne and Bergelson 2006). As well, saracatinib has been demonstrated to work in tandem with gemcitabine, a type of medicine that has an anti-MERS-CoV action (Shin et al. 2018). The SRC has been further proven to be critical for the dengue virus replication using the siRNA knockdown. The dengue infection has been additionally suppressed by dasatinib, which inhibits the virus replication complex to produce the infectious virus particles (Chu and Yang 2007; Kumar et al. 2016). Likewise, saracatinib and dasatinib have functioned in vitro against the dengue virus, targeting the RNA replication factor FYN (de Wispelaere et al. 2013). Through genetic knockdown, YES has shown to lower the West Nile virus titers by affecting the viral replication cycle, and then inhibiting the viral assembly and egress (Hirsch et al. 2005). At last, the importance of the c-terminal SRC kinase (Csk) has been indicated by the siRNA library screenings, aimed at finding the host components essential for the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and dengue replications.

Extracellular signals from the growth hormones and cytokines are both mediated and amplified by the transmembrane protein Janus-kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which prevent the JAK activation, and have further proven beneficial for the treatment of inflammatory disorders (Bertsias 2020). The JAK1 and JAK2 are also primarily inhibited by both baricitinib and ruxolitinib (Bertsias 2020). The JAK inhibitors have been further shown to reduce the high doses of cytokines, and thereby inflammation, in the severely infected SARS-CoV-2 cases (Gaspari et al. 2020). Excessive cytokine release is thus assumed as a key factor in disease development in off-label situations, wherein such inhibitors have shown to be effective (La Rosée et al. 2020). Although some small studies (Zhang et al. 2020) have supported the concept that the JAK inhibitors can effectively counteract the high levels of the cytokine production in the SARS-CoV-2 infection, their impact on a larger population has yet to be examined.

The cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) also play a leading role in the control and advancement of the cell division cycle (Meijer 2000). Viruses, usually the ones replicated via altering the CDK signaling system, in turn regulate the cell division (Meijer 2000). In line with the new findings, the SARS-CoV-2 makes changes in the CDK activity, and causes cell cycle arrest through enhancing the CDK2 phosphorylation. The CoV infectious bronchitis virus and other RNA viruses have been further reported with the similar effects (Bouhaddou et al. 2020). The host cell division cycle arrest also ensures the appropriate repair of nucleotide and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), as well as the sufficient amount of the DNA-replication proteins for the virus (Bouhaddou et al. 2020). Moreover, CDKs have been discovered to be essential for the DNA and RNA virus replication (Schang 2004). The multiplication of cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and some other DNA viruses have been further indicated to be hindered by the CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) (Meijer 2000). The R-roscovitine (CYC202) and flavopiridol (as CDKIs) also inhibit the viral replication of the RNA viruses, like human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) (Pumfery et al. 2006). Indeed, the CDKIs function by targeting the host cellular proteins rather than the viral ones, to prevent viral replications (Schang et al. 2002). Considering the lack of specificity in the CDKIs, such inhibitors have a broader antiviral effect than the traditional ones (Schang 2004).

The CDKIs may also have a favorable effect on the COVID-19 management; however, further research is needed to verify this speculation. The CGP-604747, as a CDKI, is thought to play a role in the treatment of the COVID-19-induced lung injury (He and Garmire 2020). The CGP-604747 had thus lowered the expression of the indicator genes for the lung injury in the lung tissues of the COVID-19 patients, according to the RNA sequencing (He and Garmire 2020). Dinaciclib had also induced the potent antiviral activity in two cell lines against the SARS-CoV-2 (Bouhaddou et al. 2020). Nonetheless, randomized control trials (RCTs) are still required to approve the promising therapeutic effects of the CDKIs, as previously established in small studies. Worryingly, the CDKI-based medicines may impose cytotoxic outcomes due to their deregulatory impacts on the cell cycle. However, in the human cancer treatment trials, low molecular weight (LMW) CDKIs, like flavopiridol and roscovitine, have thus far exhibited little harm (Schang 2004). Neutropenia, corrected QT (QTc) interval prolongation, and hepatotoxicity are also among the few known side effects of the breast cancer treatment with the CDK 4/6 inhibitors, including palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib (Thill and Schmidt 2018). As a result, RCTs are needed to assess the possible short-term complications of the CDKI-based treatments for the COVID-19 patients.

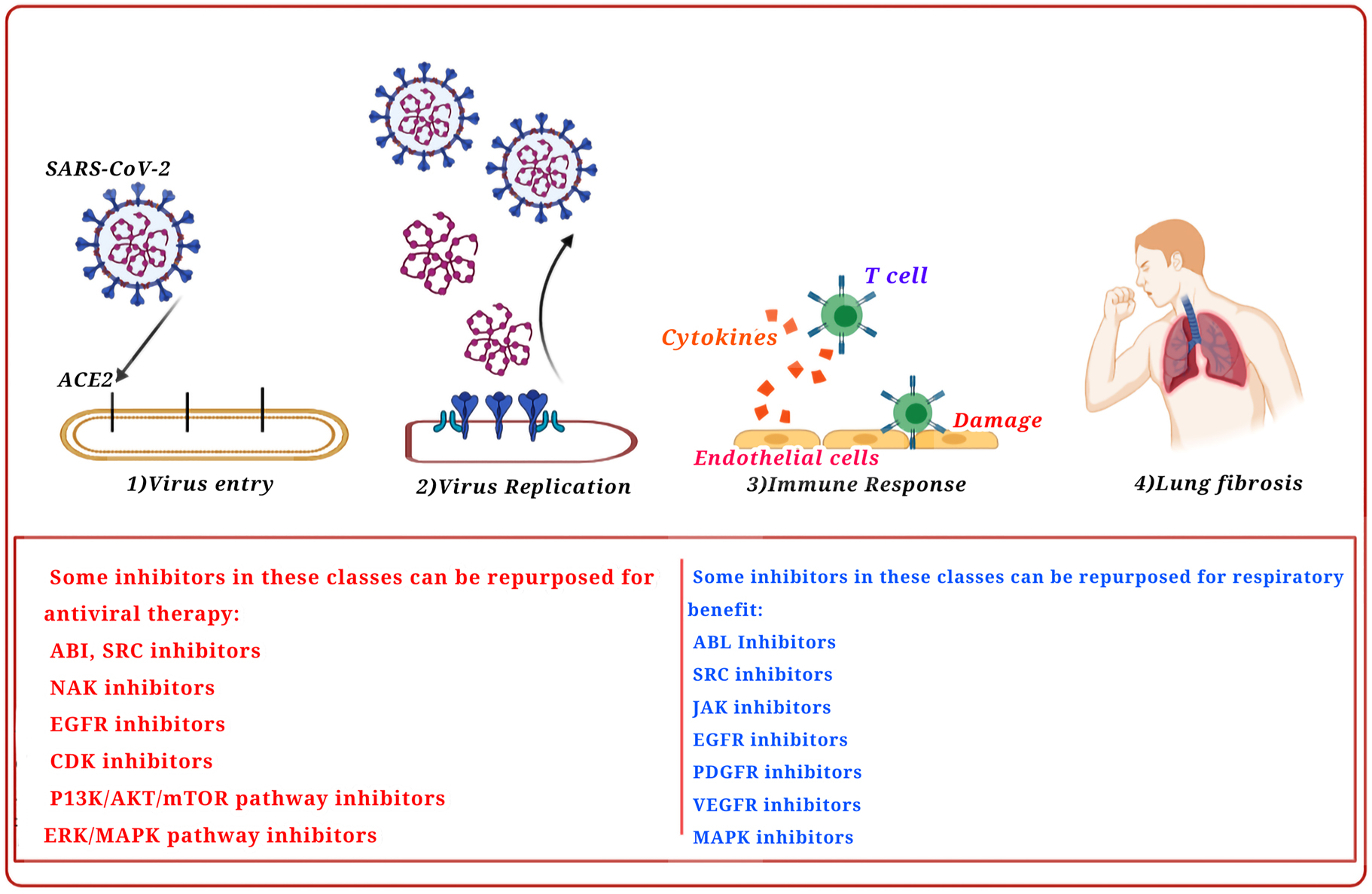

The FDA-approved kinase inhibitors have been further analyzed in terms of their ability to target the associated proteins in the SARS-CoV, the MERS-CoV, and the similar virus infections, such as the ABL proteins, AAK1, CSK, FYN, GAK, CDK9, KIT, LYN, CDK6, EGFR, SRC, RET, AXL, and YES, using the KINOME scan biochemical kinase profiling data from the Harvard Medical School Library of Integrated Network-based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) (Rouillard et al. 2016) (Figure 2).

Kinase inhibitors repurposed as antiviral treatments for their respiratory advantage.

Viral entry inhibitors

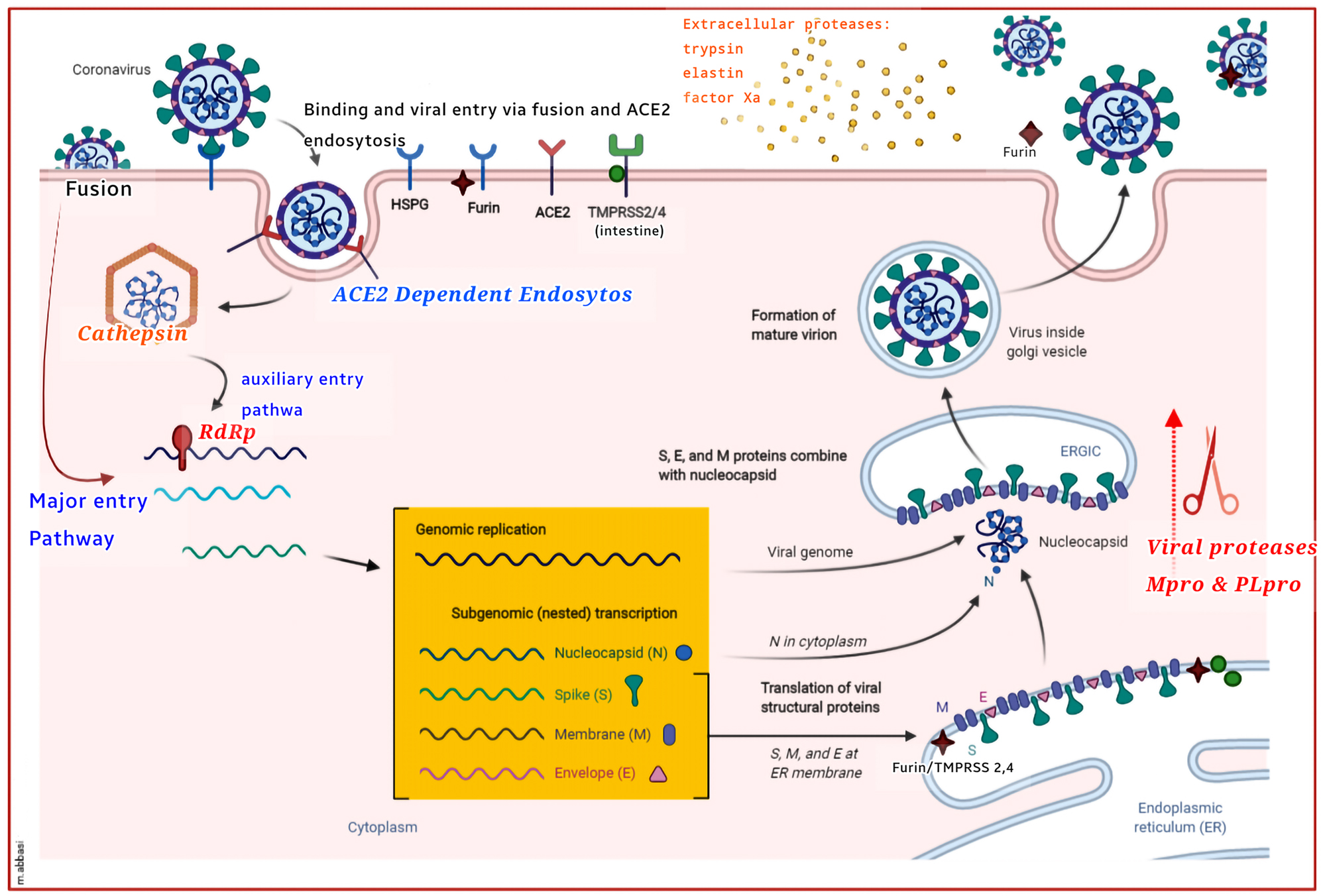

A number of proteases play critical roles in the SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication cycle in the human cells (Figure 3). The SARS-CoV-2, for example, is regulated by a vast array of host proteases during its binding and subsequent cell penetration (Millet and Whittaker 2015; Shang et al. 2020). The viral proteases, including the major protease (Mpro) and the PLpro, accordingly can significantly contribute to the intracellular replication and maturation of the virus (Anand et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2020). Conducting mechanistic studies on proteases is therefore essential for the successful prevention or treatment of COVID-19, using newly designed antiviral medicines. While a considerable number of hurdles in the way of utilizing proteases as pharmaceutical targets are brought up by the wide diversity of proteases, such diversity can offer researchers multiple potential targets for developing new medicines (Figure 3).

Host and viral proteases mediate SARS-CoV-2 infection and growth. Different host viral proteases, known to trigger some CoV S proteins, are depicted in the SARS-CoV-2 lifecycle. CoVs and other viruses also infect the cells by forming non-specific binds with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Viral fusion can effectively take place at the plasma membrane, using the membrane proteases, like TMPRSS2 & 4, and perhaps furin. As well, endocytosis, which may only act as an auxiliary entry mechanism in the TMPRSS+ cells, bypasses the viral entrance, dependent on the cathepsin and pH levels. Viral activation may also involve extracellular proteases, such as elastin, typsin, and factor Xa protease. In the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), trans-Golgi network (TGN), and cytoplasm, the maturation of the viral proteins (viz., S, M, E, and N) is further mediated by the viral proteases, Mpro and PLpro, which are then packaged into viral particles. In advance of the release of the mature viron, furin and perhaps the TMPRSS protease stimulate the S protein cleavage in the viron-associated ER and TGN systems. The unactivated virion (uncleaved, green), the semi-activated virion (S1/S2 cleaved, yellow), and the fully activated virion (S1/S2 and S1 cleaved, red) are thus the three models suggested for the SARS-CoV-2 particles. The ACE2+/furin+ and TMPRSS+ cells can also generate semiactive (yellow) and full-active (red) virions, thereby infecting the surrounding ACE2+ cells with or without the cell wall proteases. Spodoptera frugiperda furin (Sfurin) and cathepsin, for example, can stimulate the activation of the virus outside the cell, when secreted as the soluble proteases. This Figure with modifications taken from Tungadi et al. (2020).

The RBD interaction within the S1 region of the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein and the human ACE2 receptor, latter of which also facilitating the SARS-CoV contact, can cause tissue tropism and enable the host cell adherence to the virus (Hoffmann et al. 2020; Wrapp and Wang 2020). The 20-fold greater binding affinity between the CoV-2 RBD and the ACE2 is similarly the cause of the greater infectivity of the SARS-CoV-2, compared to that of the SARS-CoV (Wrapp and Wang 2020). Following the receptor interaction, the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) and/or the cathepsin B/L (CatB/L) cleave the S protein at the S1/S2 and S2 sites, allowing access to the host cellular cytoplasm (Hoffmann et al. 2020). The site S2 cleavage also results in the development of an antiparallel six-helix bundle (6-HB), which leads to the fusion process, and thereby the viral RNA uncoating and release into the cytoplasm (Bosch et al. 2003). The replicase gene is then translated into the viral RNA and polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, which produce non-structural proteins due to autocleavage (Nakagawa et al. 2016). For the replication of the viral genome, the replicase-transcriptase complex is formed by the non-structural proteins. In addition to the structural proteins (viz., S, E, M, and N), which form new virions at the final lifecycle stages of the virus, the genome also expresses the accessory proteins (Fehr and Perlman 2015), which induce viral pathogenicity, and suppress the host immune system (Zhao et al. 2012). Employing effector cells harboring the super folder green fluorescent protein (sGFP) fusion, the peptides generated from the HR2 regions of the SARS-CoV (Liu et al. 2004) and the MERS-CoV (Lu et al. 2014) have subsequently shown to suppress the intercellular fusion, mediated by the HCoV S. The IC50 value has been further estimated by the cell fusion assays to be around 0.6 µM for the MERS-CoV HR2P (SLTQINTTLLDLTYEMLSLQQVVKALNESYIDLKEL), while the HR2P-M1 mutant with two mutation and HR2P-M2 mutant with seven mutations, which have the potential of creating intramolecular salt-bridges, have proven more stable and water-soluble than their precursor HR2P peptide with a similar potency (Lu et al. 2014). In the cell fusion test, the CP-1 peptide (GINASVVNIQKEIDRLNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGKYE) of the SARS-CoV HR2 domain has been further estimated to have an IC50 of 19 µM (Liu et al. 2004). In cell fusion investigations for the WIV1-, NL63-, OC43-, 229E-, Rs3367-, SARS-, MERS-, and SHC014-CoVs, the EK1 peptide displays wide-ranging suppression with the IC50 values of 0.19–0.62 µM (Xia and Yan 2019). The EK1 dose-dependently suppresses infection and the replication of the NL63-, 229E-, OC43- and MERS-CoVs when tested against live HCoV infections. Furthermore, EK1 given intranasally had protected the OC43 and MERS-CoV-infected mice, and boosted their survival rates (Xia and Yan 2019). Preliminary data have further shown that the EK1 peptide is effective against the SARS-CoV-2 S protein-mediated membrane fusion in a dose-dependent manner (Xia et al. 2020). The EK1 peptide has also shown to be dose-dependently effective against the PsV infection and membrane fusion induced by the SARS-CoV-2 S protein, according to the preliminary results.

As an anti-HIV protease inhibitor that induces apoptosis and necrosis, and inhibits the SARS-CoV replication, nelfinavir mesylate (or Viracept) has recently been described as an inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 S-mediated cell-cell fusion and multinucleated cell generation (Yamamoto et al. 2004). Since the virus can intercellularly transmit without entering into the extracellular areas or being exposed to neutralizing immune agents, the syncytia development is considered as a critical cytopathic event. Furthermore, an inflammatory response with the possible side effects on the host cells can be activated by the virus-induced cell fusion during the CoV infection. In immunofluorescence experiments, nelfinavir mesylate has been demonstrated by the immunofluorescence assessments to completely inhibit the cell-cell fusion mediated by the SARS-CoV-2 and the SARS-CoV S glycoproteins at the 10 μM dosage, without influencing the S cell surface expression. Although there is no experimental proof, nelfinavir mesylate may attach to the trimeric S, close to the fusogenic region, according to the computational research. The compound is thus suggested to have the potential for intervening the post-translational procedures or preventing the cellular proteases involved in the S-n or S-o fusion activation, based on the pleiotropic effect previously reported for nelfinavir mesylate on the ER stress; however, experimental findings are yet to be achieved to support these assumptions. The SARS-CoV-2 S protein priming, along with the SARS-CoV and other CoVs, has recently been demonstrated to be mediated by theTMPRSS2 (Glowacka et al. 2011; Hoffmann et al. 2020; Kawase et al. 2012; Matsuyama et al. 2010; Simmons et al. 2005). Also known as epitheliasin, the TMPRSS2 is a type II TTSP of 492 amino acids, located on the cell membrane, regulating intercellular and cell-matrix interactions. As of now, 17 members of the human TTSP family have been identified, sharing structural similarities. In the N-terminal intracellular domain, the stem region, which possess a binding site in the initial extracellular part for low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and calcium in a single scavenger receptor Cys-rich (SRCR) domain and an LDL receptor A motif, proceeds by the transmembrane domain and several phosphorylation sites. The catalytic triad His-Asp-Ser, which contains the Ser hydroxyl group, is further located in the C-terminal extracellular endoprotease domain. The Ser hydroxyl group also enhances the priming site nucleophilic attacks (Szabo and Bugge 2008). The prostate is the primary site of the TMPRSS2 expression, but it has been detected in the lungs, colon, and pancreas. The TMPRSS2 expression in the physiologically unknown regions of the upper airways, bronchi, and lungs, correspondingly suggests its vital role in the pneumotropic process of the SARS-CoV, the MERS-CoV, the SARS-CoV-2, the HCoV-NL63, and some other life-threatening viruses. In fact, the ACE2, an enzyme ubiquitously found in the body organs especially the lungs, mediates the CoV entrance into the host cells. Furthermore, despite the fact that the ACE2 is found in the pneumocytes, type I and II, the SARS-CoV has been shown to induce the type I pneumocyte infection at the early stages (Fukushi et al. 2005; Matsuyama et al. 2010). As well, the TMPRSS2 induces the CoV transmission and immunopathology, according to in vivo experiments (Iwata-Yoshikawa et al. 2019). As previously stated, the endosomal pathway mediates the SARS-CoV-2 entrance into the cells using CatB/L; therefore, blocking this pathway can potentially treat the SARS-CoV-2 infection as evidenced by prior research on the SARS-CoV-2 and similar CoVs (Hoffmann et al. 2020; Shirato et al. 2017, 2018; Simmons et al. 2005; Zhou et al. 2015). The CatB/L, a member of the papain structure clan, are human lysosomal cysteine proteases that are comprised of 11 cathepsin subclasses of L (L1), B, C, F, H, K, O, V (L2), X, S, and W. Unlike lysosomes (LYSs), which are responsible for the immune reactions against external agents and the recycling and degradation of biological agents, cathepsins are involved to a greater or lesser extent in some procedures, such as protein degradation, autophagy, cell death, and immune signaling, depending on the cell/tissue types (Reiser et al. 2010).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) modulators

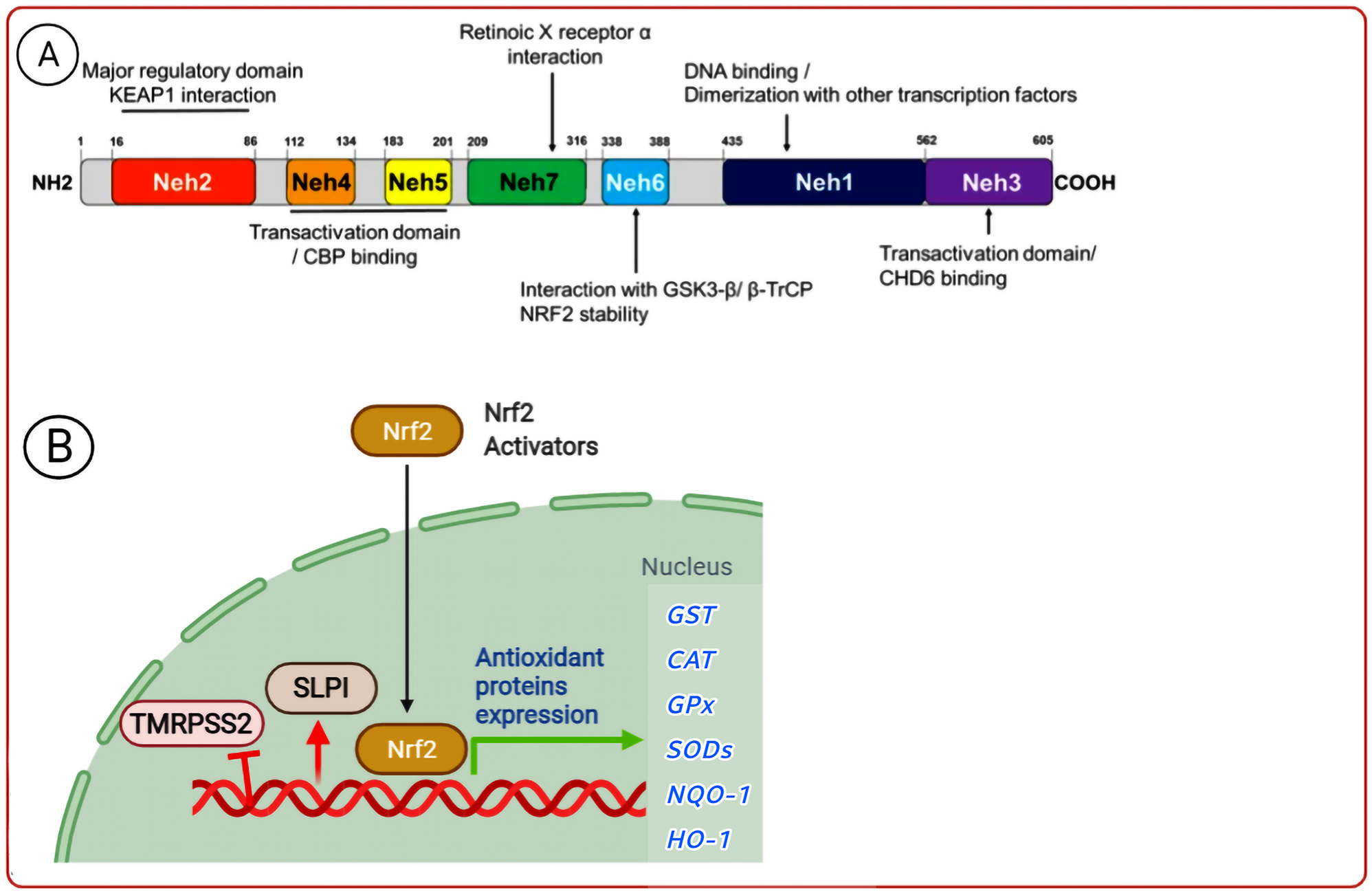

Known as a cap‘n’collar (CNC) basic-leucine-zipper transcription-factor family member, Nrf2 proposedly play a key role in the regulation of oxidative stress (OS) by upregulating glutathione and thioredoxin-antioxidant systems and some other anti-oxidant genes, along with the NAD (P) H quinine-oxide-reductase-1 (NQO1) and aldo-keto reductase (AKR). Moreover, the Nrf2 system suppresses inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidation (Al-Huseini et al. 2019; Al-Mudhaffer et al. 2019). The activating transcription factor (ATF) and cAMP-responsive element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB), Nrf-1, CREB/ATF AP-1 and -2, small MAFS, and nuclear factor/erythroid 2 (NFE-2) are also among other members of the CNC family. The Nrf2 is categorized with seven domains, namely the Nrf2-ECH-homology (Neh) domains of Neh-1 to Neh-7 (Figure 4) (Ahmed et al. 2017). The anti-protease secretion is thus boosted by the Nrf2 activators, such as the secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), which inhibits the serine protease activity. The Nrf2 activators can also bind to the promoter genes of the target cells, and then downregulate the TMPRSS2, thereby defending the target cells against viral infections (Schultz et al. 2014). As a result, these activators reduce the virus multiplication by impeding its entry into the respiratory ECs (Figure 4). In a 2005 study, Iizuka et al. had accordingly discovered that the SLPI had not been expressed in the Nrf2-knockout mice, causing the cells to be prone to inflammation by disrupting the protease/anti-protease balance, and that the SLPI gene had upregulated when the Nrf2 had been activated for inducing the anti-oxidant effect and preserving the balance between the proteases and anti-proteases (Iizuka et al. 2005). Likewise, Ling et al. (2012) had found that the gastrointestinal delivery of the epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG, as an Nrf2 activator), similar to that of seltamivir, had minimized the viral pneumonia entrance and replication in the lungs, thus increasing the survival rate.

Structure of human Nrf-2 and its function. The Nrf2 activator inhibits the virus entrance and replication by over-expressing the anti-oxidant enzymes and the SLPI anti-protease protein, as well as down-expressing TMRPSS2.

Once the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) interacts with the Nrf2 transcriptional-CREB-binding protein (CBP), the Nrf2 pathway induces ubiquitination and gene transcription to degrade the ikappaB kinase (IKK) and further limit the NF-κB activity. The activation of the Nrf2-dependent anti-oxidant genes further inhibits the production of inflammatory agents, including the TNF, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) (Thimmulappa et al. 2006). The expression of the toll-like receptors (TLRs) is also regulated by the Nrf2, which downregulates the receptor production (Al-Mudhaffer et al. 2019). Li et al. had accordingly found that the TLR4 expression was higher in the Nrf2 knockout mice than in the wild type ones (Wang et al. 2018). Wang et al. (2018) had similarly conducted immunohistochemistry (IHC) to investigate the way the Nrf2 activator therapy had affected the number of the TLR-positive cells, in which the TLR-positive cells had decreased in number compared to those in the control group (Wang et al. 2018). As well, ticfedra, a fumarate ester of the dimethyl fumarate (DMF), has been recently approved by the FDA for treating multiple sclerosis (MS) and psoriasis (Fox 2012). The DMF binds to and activate the IKK at Cys-179, thereby inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and exerting its powerful anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. The NF-κB is therefore prevented from being released from its cytoplasmic complex, NF-κB-IB, which results in the suppression of the downstream pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (Gold et al. 2012) (Figure 5). Furthermore, it improves cellular response to OS by modulating the glutathione system (Dibbert et al. 2013). The Nrf2 activation and the NF-κB prevention also signify the molecular mechanism of action of the DMF, which exerts a vital anti-inflammatory effect. The Nrf2 further interacts with the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) in the absence of the DMF, urging it to be ubiquitinated. Once the DMF disrupts the Keap1-Nrf2 complex at the Cys residues, the Nrf2 is released and translocated to the nucleus (Figure 5) (Gold et al. 2012).

The mechanism(s) of action proposed for DMF are depicted in a simplified flow diagram.

Other SM metabolites

Nucleoside and non-nucleoside medicines are the two categories into which the ribonucleic acid (RNA)-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors are divided. Drug resistance also limits the application of the non-nucleoside inhibitors, since they are unable to function on additional subtypes. The nucleoside medicines, on the other hand, can impose their direct effects on highly conserved active pockets while acting as the RdRp catalytic substrates. RDV (GS-5734), ribavirin/favipiravir, penciclovir, and ribavirin are currently the most effective nucleoside RdRp inhibitors for COVID-19 (Gordon and Tchesnokov 2020; Tchesnokov et al. 2019). RDV, known by some studies as Veklury, is further applied as a prodrug, and is converted into an active SM metabolite based on the metabolism inside the cell. This medicine is initially introduced into the body in the form of monophosphoramidate nucleoside (GS-5734) as a prodrug. After entering the cell, it finally turns into its active form, the active SM metabolite nucleoside triphosphate. This form is also called the RDV-triphosphate (GS-443902), whose mechanism is targeting the RNA polymerase SARS-CoV-2 (RdRp). In another expression, the GS-443902 acts as a substrate for the RdRp, competitively prevents the binding of the adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) to the RdRp, and ultimately disrupts the viral RNA replication pathway (Malin et al. 2020). Meanwhile, the mechanism of the inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 by favipiravir is still unknown. In general, favipiravir is used as a prodrug and is converted into the active form (favipiravir-ribofuranosyl-5′-triphosphate [RTP]) in the body. The active form inhibits the RNA replication by affecting the viral RdRp. In some studies, the stopping of the replication pathway by favipiravir has been attributed to the induction of the mutations in the virus genome. This theory has not been proven conclusively (Pavlova et al. 2021) (Figure 6).

Mechanism of RDV and ribavirin/favipiravir in the SARS-CoV-2 treatment.

Gilead Sciences, Inc. also produced RDV (GS-5734), a new nucleotide analog antiviral prodrug, as a therapy for the infection caused by the Ebola virus and the Marburg virus (Agostini et al. 2018; Wise 2020). Given its anti-SARS-CoV-2 capacity in vitro, RDV, a negative regulator of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase with previously approved antiviral action against the SARS-CoV-1 and the MERS-CoV in vitro, has been recently introduced as a viable therapy option for COVID-19 (Agostini et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2019; Sheahan et al. 2017, 2020; Wang et al. 2020). In this respect, RDV could effectively prevent the lung damage and viral infection in non-human primate samples once administered 12 h after the MERS-CoV injection (de Wit et al. 2013; de Wit et al. 2020).

Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. further developed favipiravir by chemically modifying a pyrazine analogue in a pyrazine carboxamide derivative (6-fluoro-3-hydroxy-2-pyrazinecarboxamide) and screening a chemical library for its inhibitory action against the flu virus (Furuta et al. 2017). Fujifilm and MediVector additionally collaborated on the international development of favipiravir (Joshi et al. 2021), as a T-705 prodrug with 157.1 g/mol molecular weight. In 2014, it successfully helped to manage the unprecedented or reappearing pandemic influenza virus infections, thereby receiving medical approval in Japan (Hayden and Shindo 2019; Shiraki and Daikoku 2020). Already been approved for the treatment of a new Chinese influenza in February 2020, favipiravir is currently being examined on the Chinese population regarding its possible therapeutic effects on COVID-19 (Li and De Clercq 2020).

A wide array of influenza viruses, such as the avian flu viruses of A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H5N1), and A(H7N9) have been successfully treated with favipiravir. As well, arenaviruses, phleboviruses, hantaviruses, Western equine encephalitis virus, noroviruses, flaviviruses, and the Ebola virus are among the RNA viruses that may be inhibited by this prodrug (Furuta et al. 2013).

Favipiravir has further exhibited an EC50 value of 67 M in Vero E6 cells, indicating its significant anti-SARS-CoV-2 action in these cells. Moreover, this medicine has proven highly efficient in protecting mice from EBOV (Wang et al. 2020). The Chinese State Medicine Administration also authorized favipiravir as the China’s first anti-COVID-19 medicine in March 2020, citing its strong effectiveness and low rate of adverse effects in a clinical trial. In a prospective, controlled, randomized, open-label human trial held at multiple centers (ChiCTR2000030254), the higher serum uric acid levels were the most frequently seen favipiravir-linked side effect (Chen et al. 2020).

Ribavirin is also a guanosine derivative that prevents the RNA and DNA viruses from replications. Nevertheless, ribavirin not only interferes with polymerases, but also disrupts the RNA capping that inhibits the RNA breakdown using natural guanosine. Furthermore, ribavirin directly suppresses inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, essential for guanine precursor transformation to guanosine, thereby inhibiting natural guanosine formation and promoting viral RNA instability (Graci and Cameron 2006). Little research on the CoV treatment during the Chinese and North American outbreaks of the SARS-CoV, as well as the MERS-CoV outbreaks in the Middle East and Asia have supported the clinical advantages of the ribavirin application; nonetheless, new studies are warranted to be done on the potential action of ribavirin against the novel CoV 2019 (nCOV2019). The first ribavirin application for treating the nCoV-related diseases in clinics is linked to its administration against the SARS-CoV, since the SARS-CoV symptoms are highly similar to those of acute respiratory syndrome, for which ribavirin has been typically prescribed (Lee et al. 2003; Peiris et al. 2003).

Conclusions

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers throughout the world have been working to create medicines for the SARS-CoV-2 treatment. Computer-simulation techniques, like molecule docking and free energy calculations, have been further exploited to find effective SARS-CoV-2 therapies. Several antiviral medicines, and the anti-SARS-CoV-2 ones in particular, have been further developed based on the highly conserved replicated gene sequence of the SARS-CoV-2, with targets such as PLpro, TMPRSS2, RdRp, 3CLpro, S protein, and ACE2. This breakthrough holds promises for providing new horizons in the future. The inhibitors of ACE2, proteases, TMPRSS2, ACE2, and virus/host cell membrane fusion, as well as the existing antimalarial medicines, are among them. Furin is further depended on the SARS-CoV-2 for participating in cell invasion in combination with TMPRSS2 and cathepsin; however, the SARS-CoV-2 uses the ACE2 to enter cells and the TMPRSS2 is employed to activate the S protein. Furin also induces the pre-activation of the S protein and reduces the SARS-reliance CoV-2 on its target cells, particularly those with the low levels of the TMPRSS2 and/or cathepsin. The furin protease and TMPRSS2 suppressors can thus work together to prevent the SARS-CoV-2 from infecting the host cells. These results have significant implications for combination therapy in pharmacological investigations and pharmacodynamics. Considering their tolerability, low pharmacological adverse effects, and high availability, flavonoids, isatins, terpenoids, and some other phytochemicals can be also administered to many cases for their antiviral effects against the SARS-CoV-2. Nevertheless, the targets, mechanisms of action, and the virus binding method of these medicines have yet to be clarified. Vaccine mass production and distribution, along with other preventive tactics, such as the quarantine and isolation of infected cases, are thus among the essential measures for bringing the pandemic to an end.

Various medical fields have further given rise to multiple theraputic agents, including pharmacological medicines, immunological agents, corticosteroids, and serum-derived antibodies from the currently COVID-19 infected individuals or the recovered ones. Sofosbuvir, galidesivir, ribavirin, RDV, and tenofovir have been thus represented as the effective medicines for treating the SARS-CoV-2 in docking analysis investigations. Moreover, indinavir, saquinavir, zanamivir, and RDV have been proven as the antiviral agents against the SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro in silico studies.

The RdRp inhibitors, like RDV, have been the most often utilized among the various COVID-19 medicinal treatments. RDV has been shown to suppress CoVs, such as the SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV, in cell culture and animal models. CoVs are generally endowed with the proofreading ability to some extent, via identifying and rectifying the erroneous insertions of the nucleoside analogues and the exact processes disrupted by the antiviral action of RDV. Although the RDV efficacy and tolerability are still under debate, this medicine has successfully improved the clinical status of severely infected COVID-19 patients in a compassionate use study. Increased liver enzymes, skin rash, renal dysfunction, diarrheas, and hypotension have also been documented as the most frequent side effects of RDV. As a result, more investigation and validation is required, including in vitro cell tests, in vivo animal studies, and pharmacological clinical trials. In one research, the high dosages of RDV had induced insulin pill toxicity and decreased sperm parameters in mice. As a result, more research into the reproductive effects of this medicine is required. Despite this, the first COVID-19 medicine authorized by the FDA was RDV. In order to develop noble therapeutic compounds, structural analyses are needed to be done on the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp in detail. In this regard, the cryostructure of the SARS-CoV-2 full-length NSP12 monomer, as well as that of its complexes with NSP7 and NSP8, has been recently revealed. Finally, the clinical-stage therapeutic agents, targeting the additional viral proteins, might improve the effectiveness of the COVID-19 treatment if used as an adjuvant therapy beside the RdRp inhibitors.

In future studies, it is suggested to carry out research aimed at investigating the effect of anti-infective SM metabolites by considering the underlying diseases separately.

Funding source: Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: Unassigned

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the Clinical Research Development Unit of Baqiyatallah Hospital, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for their valuable guidance and helpful advice.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Aghamollaei, H., Sarvestani, R., Bakherad, H., Zare, H., Guest, P.C., Ranjbar, R., and Sahebkar, A. (2021). Emerging technologies for the treatment of COVID-19. In: Clinical, biological and molecular aspects of COVID-19, pp. 81–96.10.1007/978-3-030-59261-5_7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Agostini, M.L., Andres, E.L., Sims, A.C., Graham, R.L., Sheahan, T.P., Lu, X., Smith, E., Case, J., Feng, J., Jordan, R., et al.. (2018). Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio 9: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00221-18.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ahmed, S.M., Luo, L., Namani, A., Wang, X.J., and Tang, X. (2017). Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 1863: 585–597, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Al-Huseini, L.M.A., Al-Mudhaffer, R.H., Hassan, S.M., and Hadi, N.R. (2019). DMF ameliorating cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in male rats. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 10: 206–213.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Mudhaffer, R.H., Al-Huseini, L.M.A., Hassan, S.M., and Hadi, N.R. (2019). Bardoxolone ameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in male rats. ATMPH 22: 122–130, https://doi.org/10.36295/asro.2019.220415.Search in Google Scholar

Allahyari, F., Hosseinzadeh, R., Nejad, J.H., Heiat, M., and Ranjbar, R. (2021). A case report of simultaneous autoimmune and COVID-19 encephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 27: 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-00978-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Anand, K., Ziebuhr, J., Wadhwani, P., Mesters, J.R., and Hilgenfeld, R. (2003). Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science 300: 1763–1767, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085658.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Andersen, K.G. and Rambaut, A. (2020). The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 26: 450–452, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bertsias, G. (2020). Therapeutic targeting of JAKs: from hematology to rheumatology and from the first to the second generation of JAK inhibitors. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 31: 105–111, https://doi.org/10.31138/mjr.31.1.105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bocksberger, S., Wagner, W., Hummel, T., Guggemos, W., Seilmaier, M., Hoelscher, M., and Wendtner, C.M. (2020). [Temporary hyposmia in COVID-19 patients]. HNO 68: 440–443, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-020-00891-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bosch, B.J., Van Der Zee, R., De Haan, C.A., and Rottier, P.J. (2003). The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 77: 8801–8811, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.77.16.8801-8811.2003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bouhaddou, M., Memon, D., Meyer, B., White, K.M., Rezelj, V.V., Correa Marrero, M., Polacco, B.J., Melnyk, J.E., Ulferts, S., Kaake, R.M., et al.. (2020). The global phosphorylation landscape of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell 182: 685–712, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.034.e19.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, A.J., Won, J.J., Graham, R.L., Dinnon, K.H.3rd, Sims, A.C., Feng, J.Y., Cihlar, T., Denison, M.R., Baric, R.S., and Sheahan, T.P. (2019). Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antivir. Res. 169: 104541, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104541.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chen, C., Huang, J., Cheng, Z., Wu, J., Chen, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, B., Lu, M., Luo, Y., and Zhang, J. (2020). Favipiravir versus arbidol for COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. MedRxiv.10.1101/2020.03.17.20037432Search in Google Scholar

Chu, J.J. and Yang, P.L. (2007). c-Src protein kinase inhibitors block assembly and maturation of dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104: 3520–3525, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0611681104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Clark, M.J., Miduturu, C., Schmidt, A.G., Zhu, X., Pitts, J.D., Wang, J., Potisopon, S., Zhang, J., Wojciechowski, A., Hann Chu, J.J., et al.. (2016). GNF-2 inhibits dengue virus by targeting abl kinases and the viral E protein. Cell Chem. Biol. 23: 443–452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.03.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Coleman, C.M., Sisk, J.M., Mingo, R.M., Nelson, E.A., White, J.M., and Frieman, M.B. (2016). Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J. Virol. 90: 8924–8933, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01429-16.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Coyne, C.B. and Bergelson, J.M. (2006). Virus-induced Abl and Fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell 124: 119–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Cui, J., Li, F., and Shi, Z.L. (2019). Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17: 181–192, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

De Wispelaere, M., Lacroix, A.J., and Yang, P.L. (2013). The small molecules AZD0530 and dasatinib inhibit dengue virus RNA replication via Fyn kinase. J. Virol. 87: 7367–7381, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00632-13.Search in Google Scholar

De Wit, E., Feldmann, F., Cronin, J., Jordan, R., Okumura, A., Thomas, T., Scott, D., Cihlar, T., and Feldmann, H. (2020). Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117: 6771–6776, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1922083117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

De Wit, E., Rasmussen, A.L., Falzarano, D., Bushmaker, T., Feldmann, F., Brining, D.L., Fischer, E.R., Martellaro, C., Okumura, A., Chang, J., et al.. (2013). Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) causes transient lower respiratory tract infection in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110: 16598–16603, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1310744110.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Dibbert, S., Clement, B., Skak-Nielsen, T., Mrowietz, U., and Rostami-Yazdi, M. (2013). Detection of fumarate-glutathione adducts in the portal vein blood of rats: evidence for rapid dimethylfumarate metabolism. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 305: 447–451, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-013-1332-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dyall, J., Coleman, C.M., Hart, B.J., Venkataraman, T., Holbrook, M.R., Kindrachuk, J., Johnson, R.F., Olinger, G.G., Jahrling, P.B., Laidlaw, M., et al.. (2014). Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58: 4885–4893, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.03036-14.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Elhusseiny, K.M., Abd-Elhay, F.A., and Kamel, M.G. (2020). Possible therapeutic agents for COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 18: 1005–1020, https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2020.1782742.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Fehr, A.R. and Perlman, S. (2015). Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 1282: 1–23.10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Fox, R. (2012). The New England Journal of Medicine publishes pivotal data demonstrating efficacy and safety of oral BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate) in multiple sclerosis. Can. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 34: 7–11.Search in Google Scholar

Fukushi, S., Mizutani, T., Saijo, M., Matsuyama, S., Miyajima, N., Taguchi, F., Itamura, S., Kurane, I., and Morikawa, S. (2005). Vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotyped with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Gen. Virol. 86: 2269–2274, https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.80955-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Furuta, Y., Gowen, B.B., Takahashi, K., Shiraki, K., Smee, D.F., and Barnard, D.L. (2013). Favipiravir (T-705), a novel viral RNA polymerase inhibitor. Antivir. Res. 100: 446–454, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Furuta, Y., Komeno, T., and Nakamura, T. (2017). Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 93: 449–463, https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.93.027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

García, M., Cooper, A., Shi, W., Bornmann, W., Carrion, R., Kalman, D., and Nabel, G.J. (2012). Productive replication of Ebola virus is regulated by the c-Abl1 tyrosine kinase. Sci. Transl. Med. 4: 123ra24, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003500.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gaspari, V., Zengarini, C., Greco, S., Vangeli, V., and Mastroianni, A. (2020). Side effects of ruxolitinib in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: two case reports. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56: 106023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Glowacka, I., Bertram, S., Müller, M.A., Allen, P., Soilleux, E., Pfefferle, S., Steffen, I., Tsegaye, T.S., He, Y., Gnirss, K., et al.. (2011). Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J. Virol. 85: 4122–4134, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02232-10.Search in Google Scholar

Gold, R., Linker, R.A., and Stangel, M. (2012). Fumaric acid and its esters: an emerging treatment for multiple sclerosis with antioxidative mechanism of action. Clin. Immunol. 142: 44–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2011.02.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Gordon, C.J. and Tchesnokov, E.P. (2020). Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 295: 6785–6797, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.ra120.013679.Search in Google Scholar

Graci, J.D. and Cameron, C.E. (2006). Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 16: 37–48, https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gralinski, L.E., Sheahan, T.P., Morrison, T.E., Menachery, V.D., Jensen, K., Leist, S.R., Whitmore, A., Heise, M.T., and Baric, R.S. (2018). Complement activation contributes to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathogenesis. mBio 9: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01753-18.Search in Google Scholar

Grifoni, A., Sidney, J., Zhang, Y., Scheuermann, R.H., Peters, B., and Sette, A. (2020). A sequence homology and bioinformatic approach can predict candidate targets for immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host. Microbe. 27: 671–680, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.002.e2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Guillot, L., Nathan, N., Tabary, O., Thouvenin, G., Le Rouzic, P., Corvol, H., Amselem, S., and Clement, A. (2013). Alveolar epithelial cells: master regulators of lung homeostasis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45: 2568–2573, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2013.08.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Halaji, M., Farahani, A., Ranjbar, R., Heiat, M., and Dehkordi, F.S. (2020). Emerging coronaviruses: first SARS, second MERS and third SARS-CoV-2: epidemiological updates of COVID-19. Inf. Med. 28: 6–17.Search in Google Scholar

Hayden, F.G. and Shindo, N. (2019). Influenza virus polymerase inhibitors in clinical development. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 32: 176–186, https://doi.org/10.1097/qco.0000000000000532.Search in Google Scholar

He, B. and Garmire, L. (2020). Prediction of repurposed drugs for treating lung injury in COVID-19. F1000Res. 9: 609, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23996.1.Search in Google Scholar

Heiat, M., Hashemi-Aghdam, M.R., Heiat, F., Rastegar Shariat Panahi, M., Aghamollaei, H., Moosazadeh Moghaddam, M., Sathyapalan, T., Ranjbar, R., and Sahebkar, A. (2021a). Integrative role of traditional and modern technologies to combat COVID-19. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 19: 23–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2020.1799784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Heiat, M., Heiat, F., Halaji, M., Ranjbar, R., Tavangar Marvasti, Z., Yaali-Jahromi, E., Azizi, M.M., Morteza Hosseini, S., and Badri, T. (2021b). Phobia and fear of COVID-19: origins, complications and management, a narrative review. Ann Ig 33: 360–370.Search in Google Scholar

Hirsch, A.J., Medigeshi, G.R., Meyers, H.L., Defilippis, V., Früh, K., Briese, T., Lipkin, W.I., and Nelson, J.A. (2005). The Src family kinase c-Yes is required for maturation of West Nile virus particles. J. Virol. 79: 11943–11951, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.79.18.11943-11951.2005.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, M., Kleine-Weber, H., Schroeder, S., Krüger, N., Herrler, T., Erichsen, S., Schiergens, T.S., Herrler, G., Wu, N.H., Nitsche, A., et al.. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181: 271–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.e8.Search in Google Scholar

Hosseini, M.J., Halaji, M., Nejad, J.H., and Ranjbar, R. (2021). Central nervous system vasculopathy associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): a novel case report from Iran. J. Neurovirol. 27: 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-00979-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, G., Xu, J., Gu, X., et al.. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497–506, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5.Search in Google Scholar

Iizuka, T., Ishii, Y., Itoh, K., Kiwamoto, T., Kimura, T., Matsuno, Y., Morishima, Y., Hegab, A.E., Homma, S., Nomura, A., et al.. (2005). Nrf2-deficient mice are highly susceptible to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Gene Cell. 10: 1113–1125, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00905.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Iwata-Yoshikawa, N., Okamura, T., Shimizu, Y., Hasegawa, H., and Takeda, M. (2019). TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 93: 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01815-18.Search in Google Scholar

Joshi, S., Parkar, J., Ansari, A., Vora, A., Talwar, D., Tiwaskar, M., Patil, S., and Barkate, H. (2021). Role of favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis 102: 501–508.10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.069Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kaul, D. (2020). An overview of coronaviruses including the SARS-2 coronavirus - molecular biology, epidemiology and clinical implications. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 10: 54–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.04.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kawase, M., Shirato, K., Van Der Hoek, L., Taguchi, F., and Matsuyama, S. (2012). Simultaneous treatment of human bronchial epithelial cells with serine and cysteine protease inhibitors prevents severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. J. Virol. 86: 6537–6545, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00094-12.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kumar, R., Agrawal, T., Khan, N.A., Nakayama, Y., and Medigeshi, G.R. (2016). Identification and characterization of the role of c-terminal Src kinase in dengue virus replication. Sci. Rep. 6: 30490, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30490.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

La Rosée, F., Bremer, H.C., Gehrke, I., Kehr, A., Hochhaus, A., and Birndt, S. (2020). The Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib in COVID-19 with severe systemic hyperinflammation. Leukemia 34: 1805–1815, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0891-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lee, N., Hui, D., Wu, A., Chan, P., Cameron, P., Joynt, G.M., Ahuja, A., Yung, M.Y., Leung, C.B., To, K.F., et al.. (2003). A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 348: 1986–1994, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa030685.Search in Google Scholar

Li, G. and De Clercq, E. (2020). Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19: 149–150, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lin, S., Shen, R., He, J., Li, X., and Guo, X. (2020). Molecular modeling evaluation of the binding effect of ritonavir, lopinavir and darunavir to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 proteases. BioRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929695.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, S., Xiao, G., Chen, Y., He, Y., Niu, J., Escalante, C.R., Xiong, H., Farmar, J., Debnath, A.K., Tien, P., et al.. (2004). Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet 363: 938–947, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15788-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lu, G., Wang, Q., and Gao, G.F. (2015). Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’ of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 23: 468–478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lu, L., Liu, Q., Zhu, Y., Chan, K.H., Qin, L., Li, Y., Wang, Q., Chan, J.F., Du, L., Yu, F., et al.. (2014). Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat. Commun. 5: 3067, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Malin, J.J., Suárez, I., Priesner, V., Fätkenheuer, G., and Rybniker, J. (2020). Remdesivir against COVID-19 and other viral diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34: 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00162-20.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Marra, M.A., Jones, S.J., Astell, C.R., Holt, R.A., Brooks-Wilson, A., Butterfield, Y.S., Khattra, J., Asano, J.K., Barber, S.A., Chan, S.Y., et al.. (2003). The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science 300: 1399–1404, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085953.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Matsuyama, S., Nagata, N., Shirato, K., Kawase, M., Takeda, M., and Taguchi, F. (2010). Efficient activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2. J. Virol. 84: 12658–12664, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01542-10.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Meijer, L. (2000). Cyclin-dependent kinases inhibitors as potential anticancer, antineurodegenerative, antiviral and antiparasitic agents. Drug Resist. Updates 3: 83–88, https://doi.org/10.1054/drup.2000.0129.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Millet, J.K. and Whittaker, G.R. (2015). Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 202: 120–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mirzaei, R., Karampoor, S., Sholeh, M., Moradi, P., Ranjbar, R., and Ghasemi, F. (2020). A contemporary review on pathogenesis and immunity of COVID-19 infection. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47: 5365–5376, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05621-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mirzaie, A., Halaji, M., Dehkordi, F.S., Ranjbar, R., and Noorbazargan, H. (2020). A narrative literature review on traditional medicine options for treatment of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Compl. Ther. Clin. Pract. 40: 101214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101214.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mohammadpour, S., Torshizi Esfahani, A., Halaji, M., Lak, M., and Ranjbar, R. (2021). An updated review of the association of host genetic factors with susceptibility and resistance to COVID-19. J. Cell. Physiol. 236: 49–54.10.1002/jcp.29868Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nakagawa, K., Lokugamage, K.G., and Makino, S. (2016). Viral and cellular mRNA translation in coronavirus-infected cells. Adv. Virus Res. 96: 165–192.10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nejad, J.H., Heiat, M., Hosseini, M.J., Allahyari, F., Lashkari, A., Torabi, R., and Ranjbar, R. (2021). Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19: a case report study. J. Neurovirol. 27: 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-00984-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Newsome, T.P., Weisswange, I., Frischknecht, F., and Way, M. (2006). Abl collaborates with Src family kinases to stimulate actin-based motility of vaccinia virus. Cell Microbiol. 8: 233–241, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00613.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nittari, G., Pallotta, G., Amenta, F., and Tayebati, S.K. (2020). Current pharmacological treatments for SARS-COV-2: a narrative review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 882: 173328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173328.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pavlova, V., Hristova, S., Uzunova, K., and Vekov, T. (2021). A review on the mechanism of action of favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19. Res. Rev. Insights 5: 1–7, https://doi.org/10.15761/rri.1000167.Search in Google Scholar

Peiris, J.S., Chu, C.M., Cheng, V.C., Chan, K.S., Hung, I.F., Poon, L.L., Law, K.I., Tang, B.S., Hon, T.Y., Chan, C.S., et al.. (2003). Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 361: 1767–1772, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13412-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pumfery, A., De La Fuente, C., Berro, R., Nekhai, S., Kashanchi, F., and Chao, S.H. (2006). Potential use of pharmacological cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors as anti-HIV therapeutics. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 12: 1949–1961, https://doi.org/10.2174/138161206777442083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ranjbar, R., Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini, H., and Safarpoor Dehkordi, F. (2020). A review on biochemical and immunological biomarkers used for laboratory diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Open Microbiol. J. 14: 290–296, https://doi.org/10.2174/1874434602014010290.Search in Google Scholar

Reeves, P.M., Smith, S.K., Olson, V.A., Thorne, S.H., Bornmann, W., Damon, I.K., and Kalman, D. (2011). Variola and monkeypox viruses utilize conserved mechanisms of virion motility and release that depend on abl and SRC family tyrosine kinases. J. Virol. 85: 21–31, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01814-10.Search in Google Scholar

Reiser, J., Adair, B., and Reinheckel, T. (2010). Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 120: 3421–3431, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci42918.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rouillard, A.D., Gundersen, G.W., Fernandez, N.F., Wang, Z., Monteiro, C.D., Mcdermott, M.G., and Ma’ayan, A. (2016). The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database, Oxford.10.1093/database/baw100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ruan, Y.J., Wei, C.L., Ee, A.L., Vega, V.B., Thoreau, H., Su, S.T., Chia, J.M., Ng, P., Chiu, K.P., Lim, L., et al.. (2003). Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet 361: 1779–1785, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13414-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schang, L.M. (2004). Effects of pharmacological cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors on viral transcription and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1697: 197–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Schang, L.M., Bantly, A., Knockaert, M., Shaheen, F., Meijer, L., Malim, M.H., Gray, N.S., and Schaffer, P.A. (2002). Pharmacological cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors inhibit replication of wild-type and drug-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by targeting cellular, not viral, proteins. J. Virol. 76: 7874–7882, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.76.15.7874-7882.2002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schultz, M.A., Hagan, S.S., Datta, A., Zhang, Y., Freeman, M.L., Sikka, S.C., Abdel-Mageed, A.B., and Mondal, D. (2014). Nrf1 and Nrf2 transcription factors regulate androgen receptor transactivation in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One 9: e87204, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shang, J., Wan, Y., Luo, C., Ye, G., Geng, Q., and Auerbach, A. (2020). Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117: 11727–11734, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003138117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sheahan, T., Sims, A., Graham, R., Menachery, V., Gralinski, L., Case, J., Leist, S., Pyrc, K., Feng, J., and Trantcheva, I. (2017). Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 9: eaal3653, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sheahan, T.P., Sims, A.C., Leist, S.R., Schäfer, A., Won, J., Brown, A.J., and Montgomery, S.A. (2020). Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 11: 222, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sheikhshahrokh, A., Ranjbar, R., Saeidi, E., Dehkordi, F.S., Heiat, M., Ghasemi-Dehkordi, P., and Goodarzi, H. (2020). Frontier therapeutics and vaccine strategies for sars-cov-2 (COVID-19): a review. Iran. J. Public Health 49: 18–29.10.18502/ijph.v49iS1.3666Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shi, Y., Wang, Y., and Shao, C. (2020). COVID-19 infection: the perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 27: 1451–1454, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-0530-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shin, J.S., Jung, E., Kim, M., Baric, R.S., and Go, Y.Y. (2018). Saracatinib inhibits Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus replication in vitro. Viruses 10: 1–19, https://doi.org/10.3390/v10060283.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shiraki, K. and Daikoku, T. (2020). Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol. Ther. 209: 107512, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shirato, K., Kanou, K., Kawase, M., and Matsuyama, S. (2017). Clinical isolates of human coronavirus 229E bypass the endosome for cell entry. J. Virol. 91: 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01387-16.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shirato, K., Kawase, M., and Matsuyama, S. (2018). Wild-type human coronaviruses prefer cell-surface TMPRSS2 to endosomal cathepsins for cell entry. Virology 517: 9–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.11.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Simmons, G., Gosalia, D.N., Rennekamp, A.J., Reeves, J.D., Diamond, S.L., and Bates, P. (2005). Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102: 11876–11881, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0505577102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sisk, J.M., Frieman, M.B., and Machamer, C.E. (2018). Coronavirus S protein-induced fusion is blocked prior to hemifusion by Abl kinase inhibitors. J. Gen. Virol. 99: 619–630, https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Szabo, R. and Bugge, T.H. (2008). Type II transmembrane serine proteases in development and disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40: 1297–1316, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tchesnokov, E.P., Feng, J.Y., Porter, D.P., and Götte, M. (2019). Mechanism of inhibition of Ebola virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase by remdesivir. Viruses 11: 326, https://doi.org/10.3390/v11040326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Thill, M. and Schmidt, M. (2018). Management of adverse events during cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor-based treatment in breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 10: 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835918793326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Thimmulappa, R.K., Scollick, C., Traore, K., Yates, M., Trush, M.A., Liby, K.T., Sporn, M.B., Yamamoto, M., Kensler, T.W., and Biswal, S. (2006). Nrf2-dependent protection from LPS induced inflammatory response and mortality by CDDO-Imidazolide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351: 883–889, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Torabi, R., Ranjbar, R., Halaji, M., and Heiat, M. (2020). Aptamers, the bivalent agents as probes and therapies for coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Mol. Cell. Probes 53: 101636, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcp.2020.101636.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Torre-Fuentes, L., Matías-Guiu, J., Hernández-Lorenzo, L., Montero-Escribano, P., Pytel, V., Porta-Etessam, J., and Gómez-Pinedo, U. (2021). ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Furin variants and SARS-CoV-2 infection in Madrid, Spain. J. Med. Virol. 93: 863–869, https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26319.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Totura, A.L. and Baric, R.S. (2012). SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2: 264–275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tungadi, R., Tuloli, T.S., Abdulkadir, W., Thomas, N., Madania, M., Hasan, A.M., and Sapiun, Z. (2020). COVID-19: clinical characteristics and molecular levels of candidate compounds of prospective herbal and modern drugs in Indonesia. Pharmaceut. Sci. 26: S12–S23, https://doi.org/10.34172/ps.2020.50.Search in Google Scholar

Vankadari, N. (2020). Structure of furin protease binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and implications for potential targets and virulence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11: 6655–6663, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01698.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wang, M., Cao, R., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Liu, J., Xu, M., Shi, Z., and Hu, Z. (2020). Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 30: 269–271, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central