The Mycobacterium tuberculosis prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase cleaves the N-terminal peptide of the immunoprotein CXCL-10

-

Trillion Surya Lioe

, Ziwen Xie

, Jianfang Wu

, Boris Tefsen

and David Ruiz-Carrillo

Abstract

Dipeptidyl peptidases constitute a class of non-classical serine proteases that regulate an array of biological functions, making them pharmacologically attractive enzymes. With this work, we identified and characterized a dipeptidyl peptidase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtDPP) displaying a strong preference for proline residues at the P1 substrate position and an unexpectedly high thermal stability. MtDPP was also characterized with alanine replacements of residues of its active site that yielded, for the most part, loss of catalysis. We show that MtDPP catalytic activity is inhibited by well-known human DPP4 inhibitors. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry we also describe that in vitro, MtDPP mediates the truncation of the C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10, indicating a plausible role in immune modulation for this mycobacterial enzyme.

Introduction

Tuberculosis is among the most prevalent of the communicable diseases, that only in the year 2020 was responsible for a staggering 1.5 million deaths. Although tuberculosis is still a tractable disease, the rise of antimicrobial resistance is manifestation of the slow obsolescence of the current antitubercular pharmacology (WHO 2021). Dipeptidyl peptidases (DPP) are non-classical serine proteases belonging to clan B of the S9 protease family (Rawlings et al. 2018). These proteases preferentially cleave off Xaa-Pro dipeptides from the N-terminus of polypeptides. This unique enzymatic specificity of DPPs is associated with a conserved structural fold that is defined by a β-propeller and an α/β hydrolase domain, as well as an unusual arrangement of the catalytic triad primary sequence that has the catalytic serine framed in a highly conserved Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly motif (Abbott et al. 1999; Aertgeerts et al. 2004; Bjelke et al. 2006; David et al. 1993; Nakajima et al. 2008; Pei et al. 2006; Rea et al. 2017; Roppongi et al. 2018; Ross et al. 2018; Waumans et al. 2015). One of the best characterized enzymes of the DPP family is the human DPP4 (hDPP4; EC 3.4.14.5), which is known to be a multifunctional enzyme involved in the regulation of insulin homeostasis and the aetiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Mortier et al. 2016; Mulvihill and Drucker 2014; Nauck 2016; Röhrborn et al. 2015). Demonstration of hDPP4 biological relevance propelled the development of hDPP4 inhibitors as successful pharmacological means for T2DM treatment (Mortier et al. 2016; Mulvihill and Drucker 2014; Nauck 2016; Röhrborn et al. 2015). DPPs have also been characterized in the bacterial kingdom, where they have been shown to be involved in nutrient processing, and identified as virulence factors (Kumagai et al. 2000, 2005; Nakajima et al. 2008; Rea et al. 2017).

Previous studies have shown the significance of mycobacterial proteases in contributing to Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenicity (Portugal et al. 2017; Zhao and Xie 2011; Zhao et al. 2021), however, the role of the mycobacterial post-proline DPPs has been neglected (Rea et al. 2017; Roppongi et al. 2018). A recent study showed that increased levels of truncated C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL-10) were found in tuberculosis (TB) lesion sites, an event that was interpreted as a potential result of hDPP4 hydrolysis (Blauenfeldt et al. 2018). However, it remains unknown whether a M. tuberculosis DPP activity can yield the cleavage of the CXCL-10 N-terminus. To help address this hypothesis, we have identified an M. tuberculosis DPP (MtDPP; GenBank: CNF91057.1), that shares low sequence homology with human DPPs (DPP4, 27.9%; fibroblast activation protein α, 30.0%; DPP8, 26.4%; DPP9, 26.4%) and bacterial DPPs (Pseudoxanthomonas mexicana DPP4, 32.6%; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia DPP4, 31.8%; Porphyromonas gingivalis DPP4, 26.5%) (Madden 2003). Here, we describe the biochemical characterization of MtDPP, and demonstrate that it possesses post-proline DPP activity, remarkable thermostability, and that its activity can be lowered by hDPP4 inhibitors. In addition, we show that MtDPP might play an immunomodulatory role, as it is able to truncate CXCL-10 in vitro, thus making it an attractive target for further studies involving M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

Results and discussion

MtDPP forms a homodimer

The GenBank sequence CNF91057.1 was cloned into the pET28a + plasmid for bacterial heterologous expression. The expressed MtDPP was consistently purified to high yields of recombinant protein (approximately 30 mg per liter of cultured bacteria) that eluted as a monodispersed peak from an S200 size exclusion chromatography column (SEC), depicted as a dominant single band on SDS-PAGE gels (Figure S1).The protein’s elution volume correlates with a molecular weight (MW) of approximately 154 kDa, whereas its MW characterized upon SDS-PAGE analysis was 85 kDa (Figures S1 and S2), indicating that MtDPP forms a homodimer in solution in agreement with the quaternary arrangement found among DPPs (Aertgeerts et al. 2004; Nakajima et al. 2008; Rea et al. 2017; Roppongi et al. 2018).

MtDPP exhibits rapid post-proline DPP activity

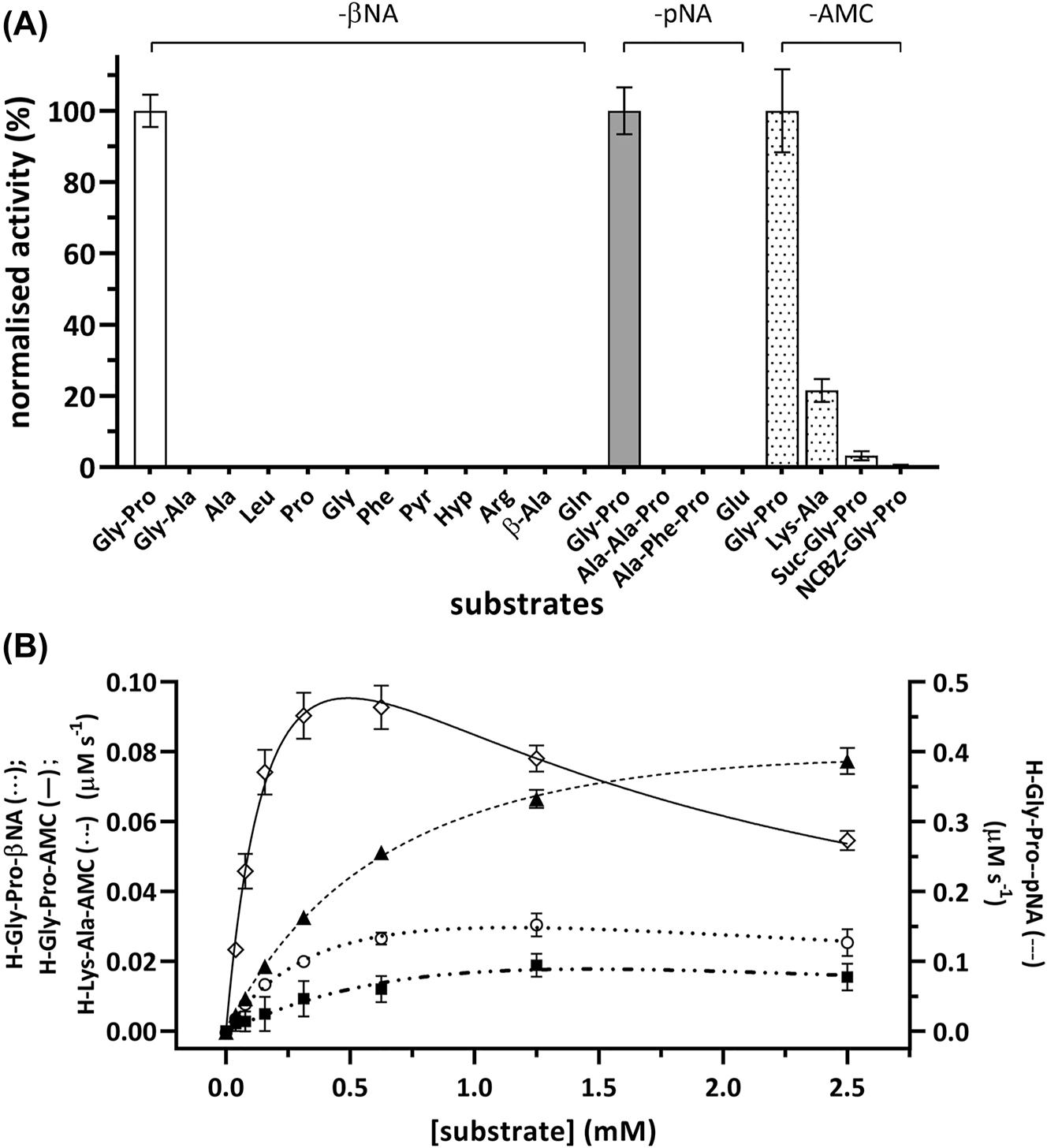

We demonstrate that MtDPP possesses an unequivocal post-proline DPP activity (Figure 1). Neither single amino acid nor tripeptide-based substrates were proteolytically cleaved by MtDPP (Figure 1A), which indicates that the positioning of the substrates’ free N-terminus imposes stringent limits to enable catalysis. Moreover, dipeptide substrates with non-proline residues in the P1 position yielded significantly lower (H-Lys-Ala-AMC; Figure 1A) or no catalytic activity (H-Gly-Ala-βNA; Figure 1A), which correlates with the capacity of other DPP orthologues that also catalyse the hydrolysis of substrates with alanine or serine occupying the P1 position but at catalytic lower rates (De Meester et al. 2002; Lambeir et al. 2001; Leiting et al. 2003; Mortier et al. 2016). The stringent specificity of MtDPP for proline-based substrates is consistent with the replacement of a tyrosine residue with phenylalanine at position 566 (Tyr631 in hDPP4; Figure S3A), which was found to be crucial for substrate S1-specificity determination in hDPP4 (Aertgeerts et al. 2004; Brandt 2002). Interestingly, although endopeptidase activity was not observed when the NCBZ-Gly-Pro-AMC substrate was used, MtDPP did exhibit marginal prolyl endopeptidase activity for Suc-Gly-Pro-AMC (3.3 ± 1.3%, normalised to h-Gly-Pro-AMC activity at 100%; Figure 1A), indicating that the active site of MtDPP can better accommodate ionized N-termini than hydrophobic ones, which aligns with its expected role as an N-terminal DPP.

MtDPP exhibits N-terminal post-proline dipeptidyl peptidase activity. The enzymatic activity was measured in buffer consisting of 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 M NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v) using surrogate substrates of the fluorophores βNA (excitation/emission wavelength: 330 nm/415 nm) and AMC (excitation/emission wavelength: 350 nm/450 nm), as well as the chromophore pNA (absorbance wavelength: 380 nm). Kinetic raw data was fitted using nonlinear regression to the Michaelis Menten (Y = V max * X/(K m + X)) or substrate inhibition (Y = V max * X/(K m + X * (1 + X/K i ))) equations, respectively. (A) MtDPP activity toward various single amino acid, dipeptidic and tripeptidic-based substrates (white, βNA; grey, pNA; dotted, AMC). MtDPP activity toward each substrate was normalised to that of a respective h-Gly-Pro substrate that shared the same leaving group. (B) MtDPP kinetics toward h-Gly-Pro conjugated to different fluorophores or chromophore (○ βNA, ◇ AMC and ▲ pNA). The experiment was conducted at substrate concentrations of 0–2.5 mM, from which rate of catalysis was determined for respective concentrations and plotted as above. Error bars indicate the standard deviation based on three independent experiments performed in triplicates.

Characterization of P1′ substrate position upon MtDPP hydrolysis was pursued using h-Gly-Pro substrates with different leaving groups (Figure S4), namely 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC), β-naphthylamine (βNA) and p-nitroanilide (pNA; Table 1; Figure 1B). MtDPP showed a mild difference between the observed K M constants, whereas the turnover k cat values depicted significant disparities (p-value < 0.001; Table 1). In contrast trend to hDPP4 kinetics (Bjelke et al. 2004; Leiting et al. 2003; Li et al. 2022; Roppongi et al. 2018), MtDPP exhibits lower turnover rate k cat constant for the AMC surrogate in comparison to the pNA conjugated substrate (Table 1). Moreover, the three different h-Gly-Pro derivatives display substrate inhibition patterns that would suggest the relevance of the P1′ leaving group during catalysis (Table 1). Despite that, a comparison between the magnitudes of the specificity constants k cat/K M for the three substrates show that they are hydrolysed at nearly diffusion rate limits (Table 1), 105–107 M−1 s−1 (Lambeir et al. 2001), indicating very rapid post-proline activity.

Kinetic parameters of the wild type and variants of MtDPP processing h-Gly-Pro dipeptide conjugated to different fluorophores.

| Protein variant | Substrate | K M a (µM) | k cat a (s−1) | k cat/K M a (µM−1 s−1) | K i a (µM) | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hDPP4b | H-Gly-Pro-AMC | 37.1 ± 1.6 | 35 ± 1.0 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | N/A | N/A |

| MtDPPc | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 2.30 ± 0.06 | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.9707 | |

| H-Lys-Ala-AMC | 0.6 ± 0.48 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 1.05 ± 1.2 | N/A | 0.7659 | |

| H-Gly-Pro-pNA | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 7.64 ± 0.11 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 11 ± 2.3 | 0.9957 | |

| H-Gly-Pro-βNA | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.9669 | |

| E184A | 2.53 ± 1.42 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.014 ± 0.004 | N/A | 0.9062 | |

| D598A | 0.64 ± 0.05 | 0.13 ± 0.002 | 0.199 ± 0.02 | N/A | 0.9774 | |

| V643S | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.148 ± 0.02 | N/A | 0.9876 | |

| Other variants | N/A | |||||

-

The enzymatic activity was measured in buffer consisting of 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 M NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v) using surrogate substrates of the fluorophores βNA (excitation/emission wavelength: 330 nm/415 nm) and AMC (excitation/emission wavelength: 350 nm/450 nm), as well as the chromophore pNA (absorbance wavelength: 380 nm). Kinetic raw data was fitted using nonlinear regression to the Michaelis Menten (Y = V max * X/(K m + X)) or substrate inhibition (Y = V max * X/(K m + X * (1 + X/K i ))) equations, respectively. a Mean ± SD values of three independently purified protein batches conducted in triplicates. b Kinetic values obtained from Roppongi et al. (2018). c Activity toward the three substrate analogues was measured with the same batch of purified protein.

Thermal stability of MtDPP and influence of pH and ionic strength on its enzymatic activity

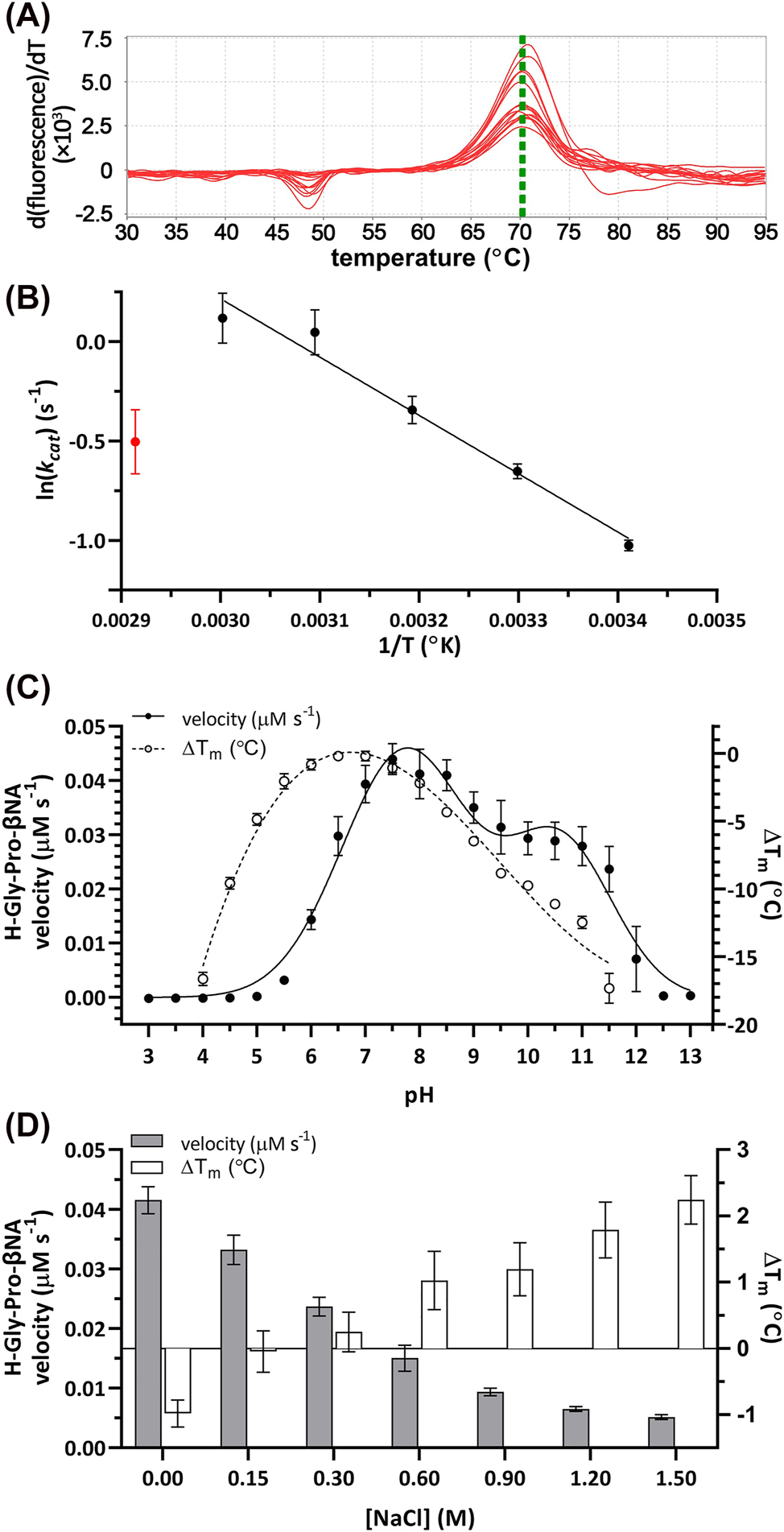

Like hDPP4 (Li et al. 2022), MtDPP displays a thermal stability characterised with a melting temperature (T m ) of 70.4 ± 0.3 °C measured in thermal shift assays (TSA) (Figure 2A). This stability was further confirmed by MtDPP showing increased catalytic rate as temperatures rise up to 60 °C, after which activity declines (Figure 2B). Characterization of the individual kinetic parameters in a temperature range between 20 and 70 °C showed that MtDPP has its maximum k cat /K M at 50 °C. In this temperature range, the changes in the observed K M values are relatively mild, at around 2.3-fold change between 30 and 50 °C; whereas the turnover rate constants increased by 2-fold in the same range of temperatures (Table 2). Unlike the kinetics assay performed using a continuous assay (Table 1), the temperature dependent kinetics assay showed no substrate inhibition (Table 2), which indicates the experimental limitations of the assay.

Biochemical characterization of MtDPP. (A) First derivative curve plot of wild type MtDPP in 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 M NaCl and 10% glycerol (v/v). (B) Arrhenius plot depicting MtDPP temperature dependent kinetics. Red data point indicates subversion to plot linearity (70 °C). (C) MtDPP catalytic rate (left y-axis; ● line) and thermal shift (∆T m ; right y-axis; ○ dotted) in different pH (3.0–13.0) conditions. (D) MtDPP catalytic velocity (left y-axis; grey bars) and ∆T m (right y-axis; white bars) in varying ionic strength environments. Control was performed in 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v). All error bars depict standard deviation derived from three experiments in triplicates. TSA melt curve plots can be found in Figure S6A and B.

Kinetic parameters of MtDPP toward h-Gly-Pro-βNA at a temperature range from 20 to 70 °C with 10 °C increments.

| Temperature (°C)a | V max b (µM s−1) | K M b (µM) | k cat b (s−1) | k cat/K M b (µM−1 s−1) | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.028 ± 0.001 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.12 | 0.9928 |

| 30 | 0.041 ± 0.003 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 1.52 ± 0.16 | 0.9860 |

| 40 | 0.056 ± 0.007 | 0.49 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 1.52 ± 0.40 | 0.9568 |

| 50 | 0.085 ± 0.016 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 1.07 ± 0.20 | 1.59 ± 0.76 | 0.8553 |

| 60 | 0.091 ± 0.019 | 1.30 ± 0.08 | 1.14 ± 0.24 | 0.94 ± 0.24 | 0.8891 |

| 70 | 0.048 ± 0.008 | 2.86 ± 1.06 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.9885 |

-

a MtDPP activity at different temperatures was measured with the same round of purified protein. b Mean ± SD values of three independently purified protein batches conducted in triplicates.

The enzymatic activity measured under constant ionic strength with varying pH showed that MtDPP is catalytically active within a wide range of the pH scale (Figure 2C). It displays a well-defined two peaked activity curve, with one peak centred on the near neutral pH range (pH 7.8), similar to what has been described for other MtDPP orthologues (Kumagai et al. 2000; Leiting et al. 2003; Nakajima et al. 2008); and the second peak centred towards the more alkaline range of the pH scale (pH 10.6). Interestingly, the activity of MtDPP at different pH values does not positively correlate with its thermal stability, as the most stable form of MtDPP was characterized to be in a more acidic pH range (Figure 2C), achieving maximal stability at a pH around 6.5. Previously, it has been shown that DPP activity is enhanced when the ionic strength increases up to values of 0.5 M NaCl (Polgar 1995). However, for MtDPP the increase in ionic strength resulted in an inverse correlation with the catalytic performance of the enzyme (Figure 2D, grey bars), whereas the thermal stability of MtDPP showed a direct correlation with the incremental increase in ionic strength (Figure 2D, white bars). Our characterization shows that MtDPP actually exhibits enhanced enzymatic activity in conditions that make the protein structurally more unstable (Figure 2C and D), which might indicate the relevance of the interdomain interactions during catalysis (Figure 3A). Considering its homology to human DPPs, the existence of a “Velcro” motif enabling a filter mechanism that increases selectivity for smaller peptides and the possible different conformations of the flap propeller loop next to the active site may both be structurally influencing catalysis (Fulop et al. 1998, 2000; Li et al. 2022; Polgar 1992). Therefore, conditions where these structural features on MtDPP are affected could result in more open protein conformations that enable easier substrate access to the active site and consequently an increase in catalytic activity.

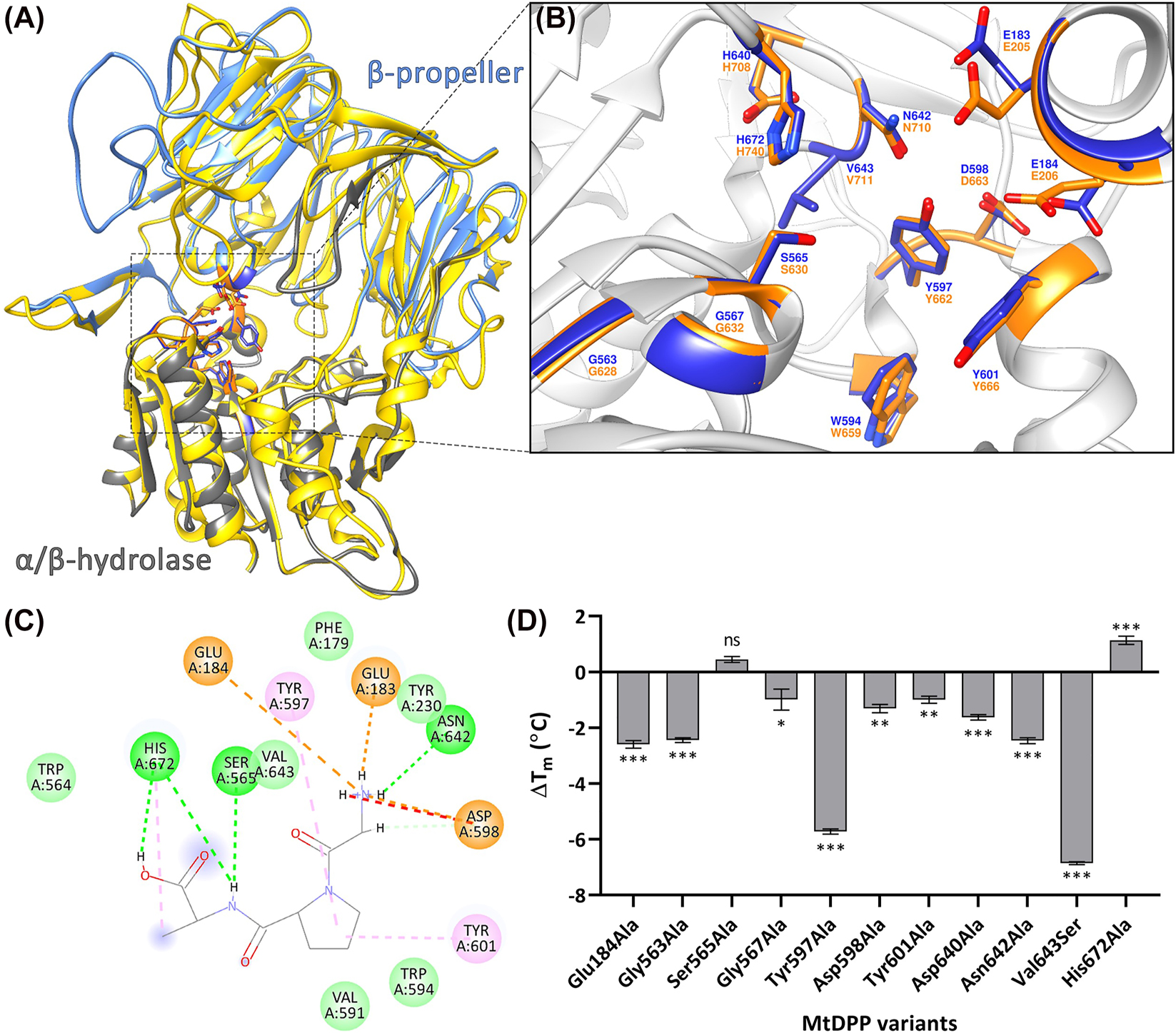

MtDPP structural model. (A) SWISS-MODEL predicted 3D ribbon model of MtDPP depicting the β-propeller (grey) and α/β-hydrolase (aqua) domains of the protein, superimposed on the hDPP4 structure (PDB: 2G5P; yellow) The model is available in ModelArchive at https://modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-ucdv8. Model statistics are shown in Figure S3B. (B) 13 superimposed catalytic site residues of MtDPP (blue) and hDPP4 (orange), indicating a conserved catalytic cleft. (C) 2D diagram representing interactions (light green circle, van der Waals; light green line, carbon hydrogen bond; green line/circle, conventional hydrogen bond; orange circle, attractive charge; orange line, salt bridge; pink line/circle, π-alkyl bond; red line, unfavourable donor–donor) between predicted MtDPP active site residues and a docked Gly-Pro-Ala substrate (PubChem CID: 7276371). (D) Thermal shift (∆T m ) of MtDPP and its variants. Error bars indicate the standard deviation derived from three experiments in triplicates. TSA melt curve plots can be found in Figure S6C.

Mapping the active site of MtDPP using site-directed mutagenesis

Based on sequence homologies (Aertgeerts et al. 2004; David et al. 1993; Nakajima et al. 2008; Pei et al. 2006; Rea et al. 2017) and a predicted MtDPP structure (Figure 3A; the model is available in ModelArchive https://modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-ucdv8), thirteen MtDPP variants were generated to map the active site of the enzyme (Figure 3B). Most MtDPP variants showed protein expression yields comparable to the wild type (WT; Figure S5A). Interestingly however, the His672Ala variant, although visible on SDS PAGE analyses, could never be detected in Western Blot experiments; and variants Trp594Ala and Glu183Ala failed to yield soluble proteins that could be used for further characterization. The failure of these active site related variants to yield soluble protein is testament to the very tight relation between protein function and structure (Uversky 2021). Many of the MtDPP variants generated were inactive (Table 1). Amino acid replacements involving the catalytic triad (Ser565, Asp640 and His672) and the nucleophilic elbow (Gly563 and Gly567) resulted in a complete loss of catalytic activity. Moreover, replacement of residues Tyr597 and Asn642, that are expected to coordinate the highly conserved double-glutamic acid (Glu183 and Glu184) motif responsible for the coordination of the substrate’s N terminus (Table 1; Figures 3B and C; Aertgeerts et al. 2004) also resulted in inactive protein variants. The same inactivity was observed with the replacement of Tyr601 (Table 1; Figures 3B and C), a substrate S1-specificity determining residue (David et al. 1993). Replacements of residues Val643, associated with the formation of the hydrophobic active site S1 pocket, as well as Asp598 and Glu184, involved in the substrate’s coordination of the N-terminus in the hDPP4 orthologue (Abbott et al. 1999; Aertgeerts et al. 2004), were characterized with smaller k cat and k cat/K M constants compared to WT, but with Asp598Ala and Glu184Ala displaying larger K M constants (Table 1) providing indication of their relevance for the binding of substrates.

The characterization of the thermal stability of seven of the MtDPP tested variants exhibited a mild reduction as indicated by thermal shifts (∆T m ) of at least 1 °C (Figure 3D), indicating that these residues contribute to enhancing the structural stability of the enzyme. Remarkably, variants Tyr597Ala and Val643Ser showed more pronounced reductions in thermostability, with a ∆T m of −5.76 ± 0.21 °C (p-value < 0.001) and −6.90 ± 0.08 °C (p-value < 0.001), respectively (Figure 3D). The variant Val643Ser in particular had an unusually flat melt curve (Figure S6C), indicating that the interactions between the dye and hydrophobic regions are similarly feasible within the tested temperature range (Huynh and Partch 2015), therefore suggesting that the Val643Ser variant significantly influences the folding state of the protein. Interestingly, the catalytic triad variants Ser565Ala and His672Ala were characterized with TSA as unaffected (with no significant change if compared to control) and slightly more stable with a higher T m value (p-value < 0.001), respectively (Figure 3D), suggesting that these residues promote a certain degree of instability in the WT enzyme.

The different protein stabilities characterized for the different protein variants support the existence of a tight relationship between the protein structure, that ensures the protein’s solubility and flexibility, and its function, that enable the catalytic process. Thus, our characterization shows that the activity of MtDPP correlates inversely with its thermal stability, and that the catalytically critical residues Ser565 and His672 counterintuitively may be identified as actual contributors to the protein’s instability.

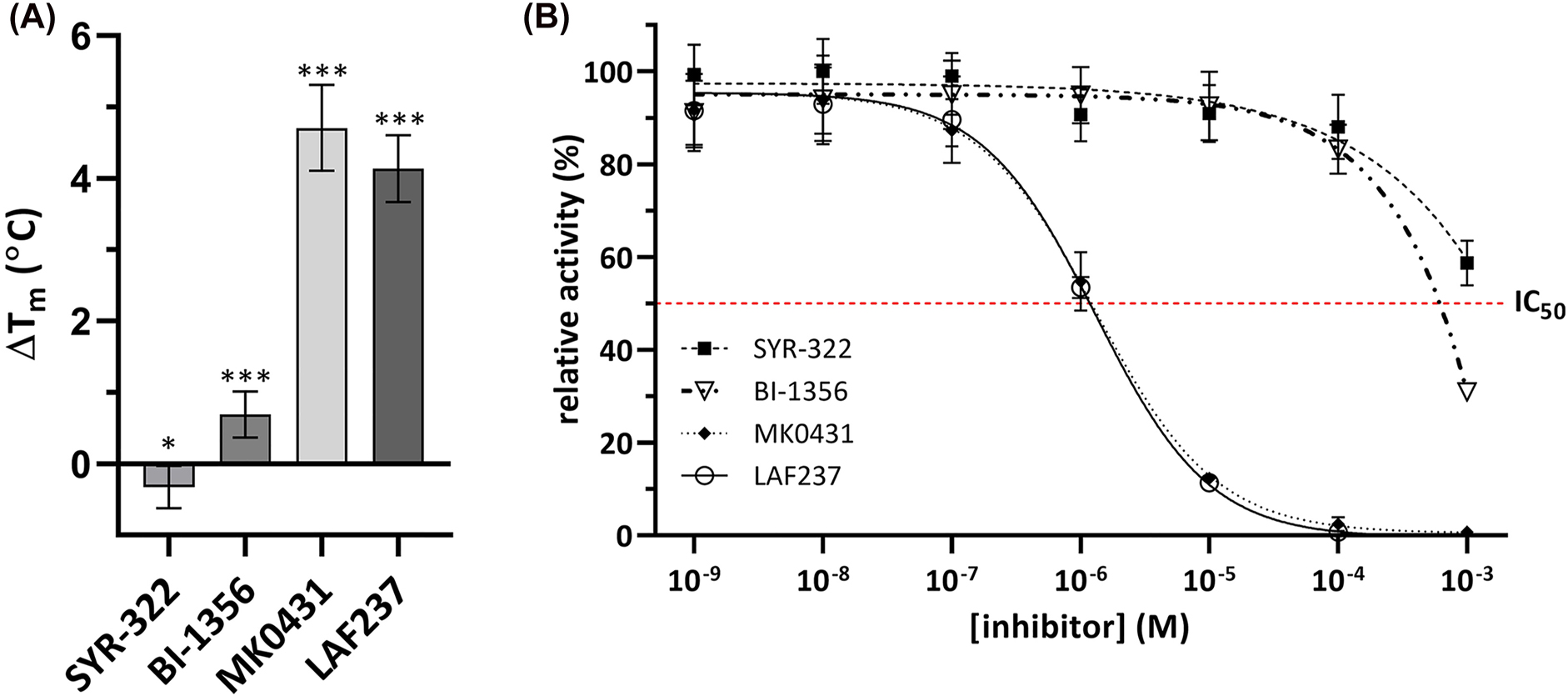

MtDPP activity is lowered by hDPP4 inhibitors

We characterized the thermal stability of MtDPP in the presence of known hDPP4 inhibitors belonging to classes 1 (LAF237), 2 (BI-1356 and SYR-322) and 3 (MK0431) (Nabeno et al. 2013; Röhrborn et al. 2015) (Figure S4). The thermal stability of MtDPP increased considerably in the presence of the molecules MK0431 and LAF237, with a ∆T m of approximately 4 °C (p-value < 0.001; Figure 4A). Interaction of MtDPP with BI-1356 also resulted in a milder increase in thermal stability (p-value < 0.001; Figure 4A), whereas a mild thermal destabilisation of MtDPP was observed in the presence of SYR-322 (p-value < 0.05; Figure 4A). Additional characterization of the inhibition of MtDPP activity with the same molecules showed that MK0431 and LAF237 displayed the strongest inhibition characterized with IC50 constants found in the low micromolar range (Figure 4B). Whereas BI-1356 and SYR-322 were characterized with weak inhibition of MtDPP with IC50 constants in the millimolar range. These results indicate that MtDPP may be more specifically inhibited by class 1 and 3 hDPP4 inhibitors, with the former interacting with the S1 and S2 subsites, forming a covalent bond with the catalytic serine residue, and the latter stabilising interactions with the S2-extensive subsite for the human homologue (Nabeno et al. 2013; Röhrborn et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the weaker bindings of these inhibitors to MtDPP indicate relevant structural differences between MtDPP and hDPP4 exist, as similarly found with other bacterial DPPs (Nabeno et al. 2013; Rea et al. 2017; Roppongi et al. 2018).

hDPP4 inhibitors bind to MtDPP and inhibit its activity. (A) ∆T m of MtDPP after treatment with hDPP4 inhibitors. (B) MtDPP IC50 inhibition assays with hDPP4 inhibitors depicting inhibition by compounds SYR-322 (■), BI-1356 (▽), MK0431 (◆) and LAF237 (○). In both, error bars depict standard deviation derived from three experiments in triplicates. Inhibition raw data was fitted to Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(1 + (IC50/X)ˆHillSlope) inhibition model. TSA melt curve plots can be found in Figure S6D.

MtDPP is able to truncate the chemokine CXCL-10 in vitro

Previously, hDPP4 has been shown to catalyse the truncation of a plethora of immune signalling molecules, including chemokines such as CXCL-10 and C-C motif chemokine ligand 22 (CCL-22), which are important for lymphocyte chemotaxis to sites of infection (Decalf et al. 2016; De Meester et al. 2002; Domingo-Gonzalez et al. 2016; Lambeir et al. 2001; Ou et al. 2013; Proost et al. 1999), as well as interleukin-23 (IL-23) which stimulates downstream signalling that leads to the production of IL-23 dependent cytokines such as interleukin-17 and 22 (Domingo-Gonzalez et al. 2016; Ou et al. 2013). Truncations of either of these molecules result in reduced lymphocyte chemotaxis (Mortier et al. 2016; Proost et al. 2017) and have been associated with TB infections (Blauenfeldt et al. 2018; Domingo-Gonzalez et al. 2016), therefore we hypothesized they could also be potential targets for processing by MtDPP.

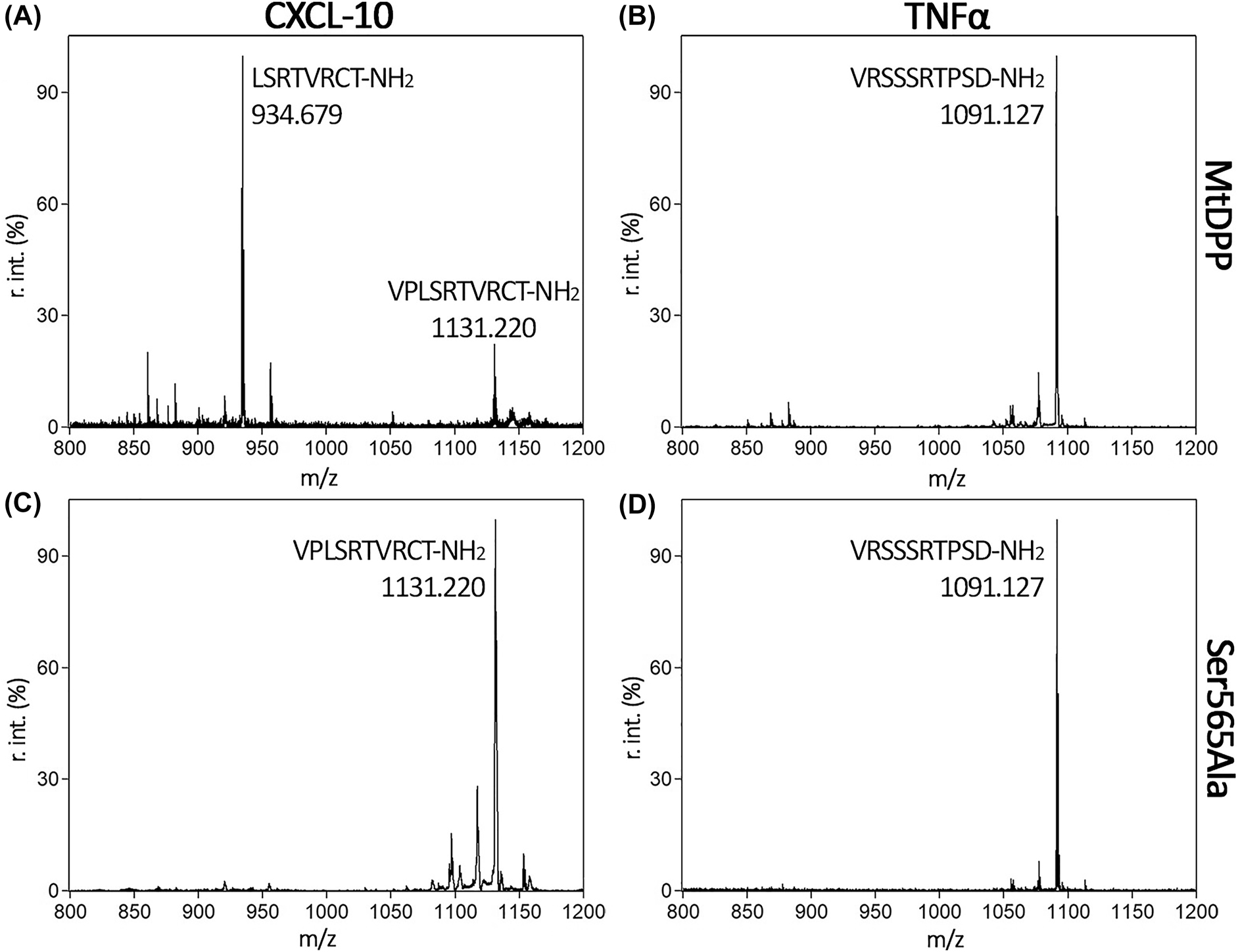

To test this hypothesis, short synthetic peptides of CXCL-10 (VPLSRTVRCT-NH2), CCL-22 (GPYGANMEDS-NH2), IL-23 (RAVPGGSSPAKER-NH2) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, VRSSSRTPSD-NH2) were incubated with MtDPP, followed by analysis using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figures 5 and S7). The results showed that MtDPP is able to cleave the N-terminus of CXCL-10 (Figure 5A), whereas the inactive MtDPP S565A variant is not (Figure 5C). As expected, the control peptide TNFα, was not processed by MtDPP (Figure 5B). Interestingly, MtDPP was unable to cleave the N-terminal dipeptide from neither the CCL-22 nor the IL-23 substrate (Figures S7A and B), strongly indicating the relevance of the P1′ leaving group in substrate processing, and thus clearly differentiating from reported hDPP4 activity. Previous studies have correlated increased levels of truncated CXCL-10 to infection severity and effectiveness of TB treatment (Blauenfeldt et al. 2018; Juffermans et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2012) with the proposal of hDPP4 having a regulatory role in active TB on CXCL-10/C-X-C chemokine receptor 3 driven chemotaxis of CD4+ T cells (Blauenfeldt et al. 2018). Although yet speculative, it seems plausible that MtDPP could potentially modulate the immune response by a rapid truncation of CXCL-10 to hinder migration of CD4+ T cells to the site of infection.

MALDI-TOF spectra analysing the processing of short chemokine and cytokine peptides by MtDPP. CXCL-10 (A and C) and TNFα (negative control, B and D) peptides were treated with wild type (A and B) or variant S565A (C and D) MtDPP. Peaks are labelled with their sequence and MW corresponding to incubated peptides or their resulting fragments. Peaks display the average relative intensities of three independent experiments.

Conclusions

In this study we showed that MtDPP exists as a homodimer and displays a preference for substrates with proline at the penultimate position of the N-termini. MtDPP displays a thermostability that yields higher enzymatic activity on the mild alkaline pH-range, and is not strongly influenced by ionic strength. The enzyme shows an inverse correlation between its enzymatic activity and thermal stability that suggests higher catalytically efficiency is achieved in conditions that promote a more open and structurally unstable conformation of the protein. We could characterize that hDPP4 inhibitors also inhibit MtDPP activity although only weakly. Moreover, MtDPP-dependent truncation of the CXCL-10 synthetic peptide indicates that the enzyme might play immunomodulatory roles during TB pathogenesis, making MtDPP an interesting target for further research.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The coding sequence of MtDPP was cloned into plasmid pET28a(+) in frame with an N-terminal 6 × His tag (GenScript™). BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli (TIANGEN®) transformed with the construct was grown in 450 mL LB supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C, 200 rpm. At an OD600 of 0.4, incubation temperature was reduced to 16 °C for 1 h, and protein expression subsequently induced with the addition of 0.2 mM final concentration of IPTG. After 24 h incubation, cells were harvested and re-suspended in purification buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 M NaCl, 10% glycerol [v/v]). Cells were sonicated (Qsonica Q700 Sonicator with microtip probe) at 40% amplitude for 20 min with 5 s on/off intervals, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was subsequently incubated at 55 °C for 10 min. Debris and protein aggregates were finally removed via centrifugation at 40,000 g, 4 °C for 30 min. The obtained supernatant was loaded onto Profinity™ immobilized metal affinity chromatography (Bio-Rad) as an initial step to purify the non-native MtDPP. MtDPP was eluted with purification buffer supplemented with 0.3 M imidazole. SEC using HiLoad™ 16/600 Superdex™ 200 pg column (Cytiva) pre-equilibrated with the purification buffer using the ÄKTAprime Plus system (Cytiva) was performed to complete the isolation of MtDPP (Figures S1). The column was calibrated using the High MW gel filtration calibration kit (GE Healthcare) and the elution volumes and molecular weights were plotted using a linear regression via GraphPad Prism v8.0.1 to resolve MtDPP MW (Figures S2A). Purified protein was concentrated with Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units with a 10 kDa MW cut-off. Protein concentration was determined both via NanoDrop A280 and bicinchoninic acid assay (Beyotime®).

Protein overexpression and purification were analysed via 10% SDS-PAGE gels and imaged via ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad; Figures S1 and S5). Immunoblotting was performed to confirm purification results with primary anti-6xHis polyclonal mouse antibody (Beyotime®) and secondary IRDye® 800CW goat-anti-mouse antibody (LI-COR®). Immunoblot images were acquired via LI-COR® Odyssey Classic Imaging system. The relative migration protein marker (PageRuler™ Prestained Protein Ladder) was measured using ImageJ (Schneider et al. 2012). The Log of the molecular weight and the relative migration factor of the protein marker were plotted using linear regression to generate a standard curve with GraphPad Prism v8.0.1 to resolve MtDPP MW (Figure S2B).

Enzyme assays: kinetics, pH, ionic strength, and temperature dependencies

Catalytic activity was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the emission and absorbance wavelengths of released fluorophore and chromophore conjugates of peptidic substrates, respectively. Fluorophores βNA (excitation 330 nm, emission 415 nm) and AMC (excitation 350 nm, emission 450 nm), as well as chromophore pNA (absorbance 380 nm) were used in this study (Figures S4). For all enzymatic assays, fluorescence and absorbance were measured via Varioskan® LUX microplate reader with the SkanIt® software (Thermo Scientific™). All assays were performed with 6 μg mL−1 enzyme on 96-well plates (BIOFIL®) in purification buffer supplemented with 0.3 mM substrate at 30 °C, shaking with low power at 600 rpm between each read (unless stated otherwise), and conducted in three experiments in triplicates. Raw data were processed with MS Excel and fitted onto plots via GraphPad Prism v8.0.1. Kinetic raw data was fitted using nonlinear regression to the Michaelis Menten (Y = Vmax * X/(K m + X)) or substrate inhibition (Y = V max * X/(K m + X * (1 + X/K i ))) equations, respectively.

Enzyme kinetics for both WT and variants of MtDPP were performed with substrate concentrations ranging from 0 to 2.5 mM pH dependency was performed with buffers from pH 3.0 to 13.0. The buffers were composed of 0.05 M acetic acid, 0.05 M 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid and 0.1 M Tris (Ellis and Morrison 1982). Ionic strength dependency assays were performed in the purification buffer (without glycerol) at increasing concentrations of NaCl within the range 0.0–1.5 M.

Temperature dependent kinetics of MtDPP were performed at temperatures from 20 to 70 °C with 10 °C increments. The assay was performed using the Veriti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosciences™). Buffer-substrate mixtures were aliquoted into MicroAmp® Fast Optical 96-well plates (Applied Biosciences™) and pre-incubated at respective temperatures for 5 min, followed by the addition of 75 ng of the enzyme. Catalysis was monitored for less than 5 min. Catalytic rates were determined by dividing the fluorescence detected by the duration at which the enzyme was allowed to catalyse the reaction.

Thermal shift assay

TSAs were performed with 0.4 mg mL−1 MtDPP (or MtDPP variants) in respective test buffers with the inclusion of other molecules being tested, and a final concentration of 5 × SYPRO™ orange dye (Invitrogen™). Fluorescence measurements were attained by running the assay on the QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems™) at increasing temperatures from 25 to 95 °C at 0.1 °C s−1 increments. Raw data analysis was performed via the Protein Thermal Shift software v1.3 (Applied Biosystems™). Temperature of melting values were determined using the Boltzmann fit value (Protein Thermal Shift™ Studies user guide – Applied Biosystems™); data were further processed with MS Excel and plotted onto bar charts or curves via GraphPad Prism v8.0.1. Experiments were conducted in three experiments in triplicates.

3D structure prediction and substrate docking

Sequence alignments were performed by CLUSTAL-W (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) (Thompson et al. 1994) and visualised via EsPript 3.0 (https://espript.ibcp.fr) (Robert and Gouet 2014). Predicted 3D structure of MtDPP (the model is available in ModelArchive https://modelarchive.org/doi/10.5452/ma-ucdv8) was constructed based on known hsDPP4 structure (PDB: 2G5P) via SWISS-MODEL (Waterhouse et al. 2018) – analysis and visualisation were performed using Chimera 1.14 (Pettersen et al. 2004). Ligand (Gly-Pro-Ala; PubChem CID: 7276371) docking with predicted MtDPP structure was performed with Rosetta ligand docking (DeLuca et al. 2015) and mapped into a 2D diagram via BIOVIA Discovery Studio.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The NEBaseChanger v1.3.2 tool (https://nebasechanger.neb.com/) was used to design primers to generate MtDPP proteins variants. Mutant constructs were created and amplified via PCR with Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), and the respective primers provided by NEBaseChanger (Synbio Technologies; Table S1). Amplified constructs were treated with DpnI and polynucleotide kinase (NEB) for 10 min at 37 °C, proceeded by ligation via T4 DNA ligase (NEB) for 6 min at RT. Respective constructs were transformed into DH5α E. coli (TIANGEN®). Site-directed mutagenesis was confirmed via plasmid sequencing (Synbio Technologies). Successfully mutated plasmids were transformed into BL21 (DE3) E. coli (TIANGEN®), followed by purification and analyses as previously described.

hDPP4 inhibitor inhibition assay

hDPP4 inhibitors SYR-322 (MedChemExpress) (Feng et al. 2007), BI-1356 (Macklin) (Eckhardt et al. 2007), MK0431 (Aladdin) (Kim et al. 2005) and LAF237 (Aladdin) (Singh et al. 2008) (Figures S4) were added separately into enzymatic assays at concentrations ranging from 1 × 10−6 to 1 mM and incubated with purified MtDPP in aforementioned enzymatic assay conditions at RT for 15 min prior to the addition of an h-Gly-Pro-βNA substrate. Catalytic activity was determined as previously described, and normalised to a control assay without the addition of the inhibitors. Experiments were conducted in three experiments in triplicates. Raw data were processed with MS Excel and fitted onto plots via GraphPad Prism v8.0.1 using the Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(1 + (IC50/X)ˆHillSlope) inhibition model.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

10–13 amino acid sequences of peptides above 1000 Da in MW were chemically synthesized (Chinese Peptides) at purities above 95%. Peptide digests were prepared as per the biochemical characterization assays, and incubated at 30 °C for 1 h (inactivated variant S565A was used as control). The reaction was terminated and diluted with the addition of TA30 (3:7, acetronitrile: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid), and further mixed with MALDI-TOF peptide analysis matrix α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg/mL in TA30) in a 1:1 ratio. Approximately 2 µL of the digest-matrix mixture was aliquoted onto an MTP 384 ground steel plate and left to air dry. The samples were processed via autoflex™ speed MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics) with an MW filter of 700–3500 Da flexControl, flexAnaysis software (Bruker Daltonics) and mMass v5.5.0 (Strohalm et al. 2008) were used to acquire and analyse obtained spectra.

Funding source: XJTLU Continuous Support Fund

Award Identifier / Grant number: RDF-SP-88

Funding source: XJTLU Research Development Fund

Award Identifier / Grant number: RDF-16-01-18

Funding source: XJTLU Key Program Special Fund

Award Identifier / Grant number: KSF-E-20

-

Author contributions: Trillion Surya Lioe: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing–original and revised drafts. Ziwen Xie: investigation. Jianfang Wu investigation. Wenlong Li: investigation. Li Sun: investigation. Qiaoli Feng: laboratory administration, investigation. Raju Sekar: supervision, revised draft, funding. Boris Tefsen: conceptualization, supervision, original and revised drafts, funding. David Ruiz-Carrillo: conceptualization, supervision, original and revised drafts, funding.

-

Research funding: The authors would like to thank the Department of Biological Sciences, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) for providing laboratory facilities and funding support. DRC would like to acknowledge the Research Development Fund RDF-16-01-18 for financial support. R.S. would like to acknowledge the Key Program Special Fund in XJTLU (Grant No. KSF-E-20) and Continuous Support Fund (RDF-SP-88) for financial support.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

Abbott, C.A., McCaughan, G.W., and Gorrell, M.D. (1999). Two highly conserved glutamic acid residues in the predicted beta propeller domain of dipeptidyl peptidase IV are required for its enzyme activity. FEBS Lett. 458: 278–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01166-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Aertgeerts, K., Ye, S., Tennant, M.G., Kraus, M.L., Rogers, J., Sang, B.C., Skene, R.J., Webb, D.R., and Prasad, G.S. (2004). Crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV in complex with a decapeptide reveals details on substrate specificity and tetrahedral intermediate formation. Protein Sci. 13: 412–421, https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.03460604.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bjelke, J.R., Christensen, J., Branner, S., Wagtmann, N., Olsen, C., Kanstrup, A.B., and Rasmussen, H.B. (2004). Tyrosine 547 constitutes an essential part of the catalytic mechanism of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 34691–34697, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m405400200.Search in Google Scholar

Bjelke, J.R., Christensen, J., Nielsen, P.F., Branner, S., Kanstrup, A.B., Wagtmann, N., and Rasmussen, H.B. (2006). Dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9: specificity and molecular characterization compared with dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochem. J. 396: 391–399, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20060079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Blauenfeldt, T., Petrone, L., Del Nonno, F., Baiocchini, A., Falasca, L., Chiacchio, T., Bondet, V., Vanini, V., Palmieri, F., Galluccio, G., et al.. (2018). Interplay of DDP4 and IP-10 as a potential mechanism for cell recruitment to tuberculosis lesions. Front. Immunol. 9: 1456, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01456.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Brandt, W. (Ed.) (2002). Cellular peptidases in immune functions and diseases 2. Springer US, Boston, MA.Search in Google Scholar

David, F., Bernard, A.M., Pierres, M., and Marguet, D. (1993). Identification of serine 624, aspartic acid 702, and histidine 734 as the catalytic triad residues of mouse dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26). A member of a novel family of nonclassical serine hydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 17247–17252, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)85329-2.Search in Google Scholar

De Meester, I., Durinx, C., Bal, G., Proost, P., Struyf, S., Goossens, F., Augustyns, K., and Scharpé, S. (Eds.) (2002). Cellular peptidases in immune functions and diseases 2. Springer US, Boston, MA.Search in Google Scholar

Decalf, J., Tarbell, K.V., Casrouge, A., Price, J.D., Linder, G., Mottez, E., Sultanik, P., Mallet, V., Pol, S., Duffy, D., et al.. (2016). Inhibition of DPP4 activity in humans establishes its in vivo role in CXCL10 post-translational modification: prospective placebo-controlled clinical studies. EMBO Mol. Med. 8: 679–683, https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201506145.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

DeLuca, S., Khar, K., and Meiler, J. (2015). Fully flexible docking of medium sized ligand libraries with RosettaLigand. PLoS One 10: 571–607, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132508.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Domingo-Gonzalez, R., Prince, O., Cooper, A., and Khader, S.A. (2016). Cytokines and chemokines in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.tbtb2-0018-2016.Search in Google Scholar

Eckhardt, M., Langkopf, E., Mark, M., Tadayyon, M., Thomas, L., Nar, H., Pfrengle, W., Guth, B., Lotz, R., Sieger, P., et al.. (2007). 8-(3-(R)-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-7-but-2-ynyl-3-methyl-1-(4-methyl-quinazolin-2-ylme thyl)-3, 7-dihydropurine-2, 6-dione (BI 1356), a highly potent, selective, long-acting, and orally bioavailable DPP-4 inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 50: 6450–6453, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm701280z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ellis, K.J. and Morrison, J.F. (Eds.) (1982). Methods in enzymology. Academic Press, New York.Search in Google Scholar

Feng, J., Zhang, Z., Wallace, M.B., Stafford, J.A., Kaldor, S.W., Kassel, D.B., Navre, M., Shi, L., Skene, R.J., Asakawa, T., et al.. (2007). Discovery of alogliptin: a potent, selective, bioavailable, and efficacious inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Med. Chem. 50: 2297–2300, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm070104l.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Fulop, V., Bocskei, Z., and Polgar, L. (1998). Prolyl oligopeptidase: an unusual beta-propeller domain regulates proteolysis. Cell 94: 161–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81416-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Fulop, V., Szeltner, Z., and Polgar, L. (2000). Catalysis of serine oligopeptidases is controlled by a gating filter mechanism. EMBO Rep. 1: 277–281, https://doi.org/10.1093/embo-reports/kvd048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Huynh, K. and Partch, C.L. (2015). Analysis of protein stability and ligand interactions by thermal shift assay. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 79: 28.9.1–28.9.14, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471140864.ps2809s79.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Juffermans, N.P., Verbon, A., van Deventer, S.J., van Deutekom, H., Belisle, J.T., Ellis, M.E., Speelman, P., and van der Poll, T. (1999). Elevated chemokine concentrations in sera of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive and HIV-seronegative patients with tuberculosis: a possible role for mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. Infect. Immun. 67: 4295–4297, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.67.8.4295-4297.1999.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kim, D., Wang, L., Beconi, M., Eiermann, G.J., Fisher, M.H., He, H., Hickey, G.J., Kowalchick, J.E., Leiting, B., Lyons, K., et al.. (2005). (2R)-4-Oxo-4-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-5, 6-dihydro[1, 2, 4]triazolo[4, 3-a]pyrazin-7(8H)-yl]-1-(2, 4, 5-trifluorophenyl)butan-2-amine: a potent, orally active dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 48: 141–151, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm0493156.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kumagai, Y., Konishi, K., Gomi, T., Yagishita, H., Yajima, A., and Yoshikawa, M. (2000). Enzymatic properties of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV produced by the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis and its participation in virulence. Infect. Immun. 68: 716–724, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.68.2.716-724.2000.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kumagai, Y., Yagishita, H., Yajima, A., Okamoto, T., and Konishi, K. (2005). Molecular mechanism for connective tissue destruction by dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV produced by the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 73: 2655–2664, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.73.5.2655-2664.2005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lambeir, A.M., Proost, P., Durinx, C., Bal, G., Senten, K., Augustyns, K., Scharpe, S., Van Damme, J., and De Meester, I. (2001). Kinetic investigation of chemokine truncation by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV reveals a striking selectivity within the chemokine family. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 29839–29845, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m103106200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Leiting, B., Pryor, K.D., Wu, J.K., Marsilio, F., Patel, R.A., Craik, C.S., Ellman, J.A., Cummings, R.T., and Thornberry, N.A. (2003). Catalytic properties and inhibition of proline-specific dipeptidyl peptidases II, IV and VII. Biochem. J. 371: 525–532, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20021643.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, T.T., Peng, C., Wang, J.Q., Xu, Z.J., Su, M.B., Li, J., Zhu, W.L., and Li, J.Y. (2022). Distal mutation V486M disrupts the catalytic activity of DPP4 by affecting the flap of the propeller domain. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43: 2147–2155, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-021-00818-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Madden, T. (2003). The BLAST sequence analysis tool. In: Madden, T. (Ed.), The NCBI handbook. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), Bethesda (MD).Search in Google Scholar

Mortier, A., Gouwy, M., Van Damme, J., Proost, P., and Struyf, S. (2016). CD26/dipeptidylpeptidase IV-chemokine interactions: double-edged regulation of inflammation and tumor biology. J. Leukoc. Biol. 99: 955–969, https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.3mr0915-401r.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mulvihill, E.E. and Drucker, D.J. (2014). Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of action of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Endocr. Rev. 35: 992–1019, https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2014-1035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nabeno, M., Akahoshi, F., Kishida, H., Miyaguchi, I., Tanaka, Y., Ishii, S., and Kadowaki, T. (2013). A comparative study of the binding modes of recently launched dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors in the active site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434: 191–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nakajima, Y., Ito, K., Toshima, T., Egawa, T., Zheng, H., Oyama, H., Wu, Y.F., Takahashi, E., Kyono, K., and Yoshimoto, T. (2008). Dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia exhibits activity against a substrate containing a 4-hydroxyproline residue. J. Bacteriol. 190: 7819–7829, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.02010-07.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nauck, M. (2016). Incretin therapies: highlighting common features and differences in the modes of action of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes. Metabol. 18: 203–216, https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.12591.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ou, X., O’Leary, H.A., and Broxmeyer, H.E. (2013). Implications of DPP4 modification of proteins that regulate stem/progenitor and more mature cell types. Blood 122: 161–169, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-02-487470.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pei, Z., Li, X., Longenecker, K., von Geldern, T.W., Wiedeman, P.E., Lubben, T.H., Zinker, B.A., Stewart, K., Ballaron, S.J., Stashko, M.A., et al.. (2006). Discovery, structure-activity relationship, and pharmacological evaluation of (5-substituted-pyrrolidinyl-2-carbonyl)-2-cyanopyrrolidines as potent dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 49: 3520–3535, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm051283e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Pettersen, E.F., Goddard, T.D., Huang, C.C., Couch, G.S., Greenblatt, D.M., Meng, E.C., and Ferrin, T.E. (2004). UCSF chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25: 1605–1612, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20084.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Polgar, L. (1995). Effects of ionic strength on the catalysis and stability of prolyl oligopeptidase. Biochem. J. 312: 267–271, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3120267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Polgar, L. (1992). Prolyl endopeptidase catalysis. A physical rather than a chemical step is rate-limiting. Biochem. J. 283: 647–648, https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2830647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Portugal, B., Motta, F.N., Correa, A.F., Nolasco, D.O., de Almeida, H., Magalhaes, K.G., Atta, A.L., Vieira, F.D., Bastos, I.M., and Santana, J.M. (2017). Mycobacterium tuberculosis prolyl oligopeptidase induces in vitro secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by peritoneal macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 8: 155, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00155.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Proost, P., Struyf, S., Schols, D., Opdenakker, G., Sozzani, S., Allavena, P., Mantovani, A., Augustyns, K., Bal, G., Haemers, A., et al.. (1999). Truncation of macrophage-derived chemokine by CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV beyond its predicted cleavage site affects chemotactic activity and CC chemokine receptor 4 interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 3988–3993, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.7.3988.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Proost, P., Struyf, S., Van Damme, J., Fiten, P., Ugarte-Berzal, E., and Opdenakker, G. (2017). Chemokine isoforms and processing in inflammation and immunity. J. Autoimmun. 85: 45–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2017.06.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Rawlings, N.D., Barrett, A.J., Thomas, P.D., Huang, X., Bateman, A., and Finn, R.D. (2018). The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 46: D624–D632, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1134.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rea, D., Van Elzen, R., De Winter, H., Van Goethem, S., Landuyt, B., Luyten, W., Schoofs, L., Van Der Veken, P., Augustyns, K., De Meester, I., et al.. (2017). Crystal structure of Porphyromonas gingivalis dipeptidyl peptidase 4 and structure-activity relationships based on inhibitor profiling. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 139: 482–491, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.08.024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Robert, X. and Gouet, P. (2014). Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: W320–W324, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku316.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Röhrborn, D., Wronkowitz, N., and Eckel, J. (2015). DPP4 in diabetes. Front. Immunol. 6: 386, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00386.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Roppongi, S., Suzuki, Y., Tateoka, C., Fujimoto, M., Morisawa, S., Iizuka, I., Nakamura, A., Honma, N., Shida, Y., Ogasawara, W., et al.. (2018). Crystal structures of a bacterial dipeptidyl peptidase IV reveal a novel substrate recognition mechanism distinct from that of mammalian orthologues. Sci. Rep. 8: 2714, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21056-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ross, B., Krapp, S., Augustin, M., Kierfersauer, R., Arciniega, M., Geiss-Friedlander, R., and Huber, R. (2018). Structures and mechanism of dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9, important players in cellular homeostasis and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115: E1437–E1445, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717565115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schneider, C.A., Rasband, W.S., and Eliceiri, K.W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9: 671–675, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Singh, S.K., Manne, N., and Pal, M. (2008). Synthesis of (S)-1-(2-chloroacetyl)pyrrolidine-2-carbonitrile: a key intermediate for dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 4: 20, https://doi.org/10.3762/bjoc.4.20.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Strohalm, M., Hassman, M., Kosata, B., and Kodicek, M. (2008). mMass data miner: an open source alternative for mass spectrometric data analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22: 905–908, https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.3444.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Thompson, J.D., Higgins, D.G., and Gibson, T.J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Uversky, V.N. (2021). The protein disorder cycle. Biophys Rev 13: 1155–1162, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12551-021-00853-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wang, J.Y., Chang, H.C., Liu, J.L., Shu, C.C., Lee, C.H., Wang, J.T., and Lee, L.N. (2012). Expression of toll-like receptor 2 and plasma level of interleukin-10 are associated with outcome in tuberculosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31: 2327–2333, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-012-1572-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Waterhouse, A., Bertoni, M., Bienert, S., Studer, G., Tauriello, G., Gumienny, R., Heer, F.T., de Beer, T.A.P., Rempfer, C., Bordoli, L., et al.. (2018). SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46: W296–W303, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky427.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Waumans, Y., Baerts, L., Kehoe, K., Lambeir, A.M., and De Meester, I. (2015). The dipeptidyl peptidase family, prolyl oligopeptidase, and prolyl carboxypeptidase in the immune system and inflammatory disease, including atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 6: 387, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

WHO (2021). Global tuberculosis report 2021. World Health Organisation (WHO), Available at: <https://www.who.int/publications/digital/global-tuberculosis-report-2021>.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, Q.J. and Xie, J.P. (2011). Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteases and implications for new antibiotics against tuberculosis. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 21: 347–361, https://doi.org/10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v21.i4.50.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhao, Y., Feng, Q., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y., Lukman, M., Jiang, J., and Ruiz-Carrillo, D. (2021). Mycobacterium tuberculosis puromycin hydrolase displays a prolyl oligopeptidase fold and an acyl aminopeptidase activity. Proteins 89: 614–622, https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.26044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2022-0265).

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Unravelling the genetic links between Parkinson’s disease and lung cancer

- Small-molecule metabolites in SARS-CoV-2 treatment: a comprehensive review

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Molecular Medicine

- Dynamic regulation of eEF1A1 acetylation affects colorectal carcinogenesis

- New lipophilic organic nitrates: candidates for chronic skin disease therapy

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- Altered population activity and local tuning heterogeneity in auditory cortex of Cacna2d3-deficient mice

- Inhibition of miR-143-3p alleviates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury via limiting mitochondria-mediated apoptosis

- Proteolysis

- The Mycobacterium tuberculosis prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase cleaves the N-terminal peptide of the immunoprotein CXCL-10

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Unravelling the genetic links between Parkinson’s disease and lung cancer

- Small-molecule metabolites in SARS-CoV-2 treatment: a comprehensive review

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Molecular Medicine

- Dynamic regulation of eEF1A1 acetylation affects colorectal carcinogenesis

- New lipophilic organic nitrates: candidates for chronic skin disease therapy

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- Altered population activity and local tuning heterogeneity in auditory cortex of Cacna2d3-deficient mice

- Inhibition of miR-143-3p alleviates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury via limiting mitochondria-mediated apoptosis

- Proteolysis

- The Mycobacterium tuberculosis prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase cleaves the N-terminal peptide of the immunoprotein CXCL-10