Abstract

Disulfide bonds play a critical role in a variety of structural and mechanistic processes associated with proteins inside the cells and in the extracellular environment. The thioredoxin family of proteins like thioredoxin (Trx), glutaredoxin (Grx) and protein disulfide isomerase, are involved in the formation, transfer or isomerization of disulfide bonds through a characteristic thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. Here, we review the structural and mechanistic determinants behind the thiol-disulfide exchange reactions for the different enzyme types within this family, rationalizing the known experimental data in light of the results from computational studies. The analysis sheds new atomic-level insight into the structural and mechanistic variations that characterize the different enzymes in the family, helping to explain the associated functional diversity. Furthermore, we review here a pattern of stabilization/destabilization of the conserved active-site cysteine residues presented beforehand, which is fully consistent with the observed roles played by the thioredoxin family of enzymes.

Introduction

Disulfide bonds are covalent interactions formed between cysteine residues through a link of the sulfur atoms in the side-chains of the thiol groups (-SH). They constitute the most important exception to the typical covalent bond present in proteins (peptide bonds). They are important building blocks in the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins, acting as inter- and intra-subunit cross links (Nagy, 2013), and play a very important role in the function and stability of proteins, particularly at the extracellular milieu. Disulfide bonds are stable bonds, only around 40% weaker than a typical C-C or C-H bond, with a dissociation energy of ca. 60 kcal/mol (251 kJ/mol) (Netto et al., 2007, 2016), and often also referred to as disulfide bridges, SS-bonds or crosslinks.

The disulfide bond results from a reversible oxidation of two thiol groups (Fernandes and Ramos, 2004):

The general SN2 mechanism for thiol-disulfide exchange involves a thiolate attack on one sulfur atom of a disulfide bond. This results in the breaking of the original disulfide bond with the release of a new thiolate, while a new disulfide bond forms between the attacking thiolate and the other sulfur atom. Hence, the process starts with a thiol deprotonation, which is highly unfavored at physiologic pH. The typical pKa of a solvent exposed thiol group is 8.3. However, the pKa of thiol groups can vary due to the surrounding protein electrostatic microenvironment, resulting in different enzymes operating in different pH ranges.

The mechanism for the thiol-disulfide exchange was studied computationally by Fernandes and Ramos (2004). In their work they confirmed that the thiolate anion was indeed the reacting species, proceeding via a simple SN2 reaction. They used a model reaction consisting of the nucleophilic attack of a methylthiol to the disulfide bond of an oxidized form of the most common protein reducing agent, dithiothreitol (DTT). This model reaction is almost free of steric strain as it is neither expected to result from the methylthiol when changing from the thiolate to the covalent product, nor from the DTT due to the hexagonal ring formed in the oxidized state. Therefore, both this model’s activation and reaction energies do reflect the intrinsic chemistry of a general thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. Fernandes and Ramos suggested in this work that the length of the disulfide bond at the transition state of this SN2 thiol-disulfide exchange reaction increased by ~0.37 Å. However, only in 2007, with the development of the exciting single-molecule techniques, were Julio Fernandez and co-workers (Wiita et al., 2006; Alegre-Cebollada et al., 2010), able to study the force-dependent chemical kinetics of the disulfide bond reduction, reporting a value of 0.34 Å, for the distance to the transition state of the reaction, in perfect agreement with Fernandes and Ramos work of 2004 (Fernandes and Ramos, 2004). More recently, Kolšek and co-workers suggested that thiol-disulfide exchange in protein folding often relies on simple accessibility criteria between thiolates (Kolsek et al., 2017).

Disulfide bonds participate in several folding pathways and are a critical part of the catalytic cycle of a variety of enzymes. The equilibrium between oxidized and reduced forms, i.e. between disulfide and free thiol is also of great biological significance in a number of processes. In particular, the thiol/disulfide ratio acts as a regulator of the cellular redox potential, controlling the intracellular redox homeostasis, a thermodynamic parameter that determines which redox reactions can occur spontaneously in cellular compartments (Nagy, 2013). The thiol/disulfide equilibrium is also involved in electron transfer processes across membranes and in the pathways of several secreted proteins (Rietsch and Beckwith, 1998; Wedemeyer et al., 2000; Sevier and Kaiser, 2002; Hogg, 2003; Bošnjak et al., 2014). In fact, while the redox environment at the cytosol tends to preserve cysteine residues in the reduced state, disulfide bonds form rapidly in the extracellular environment.

While there is a vast number of proteins in which the disulfide bond constitutes a stable component of their mature form, in their final folded structure, several important enzymes have pairs of cysteines that cycle between reduced and oxidized states. These are often involved in the formation, transfer or isomerization of disulfide bonds in other substrate proteins through a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction. From these, the first to be described was thioredoxin (Trx) (Laurent et al., 1964), an ubiquitous enzyme that participates in the reduction of several proteins present in the cytoplasm. Glutaredoxin (Grx) enzymes (Holmgren, 1976) also possess a similar Trx-fold, albeit with a different amino acid sequence, to reduce substrates using glutathione (GSH). Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (Wang et al., 2013) is another important oxidoreductase acting in disulfide bond formation and isomerization, involved in the isomerization of misformed SS bonds to promote the correct folding of secretory proteins.

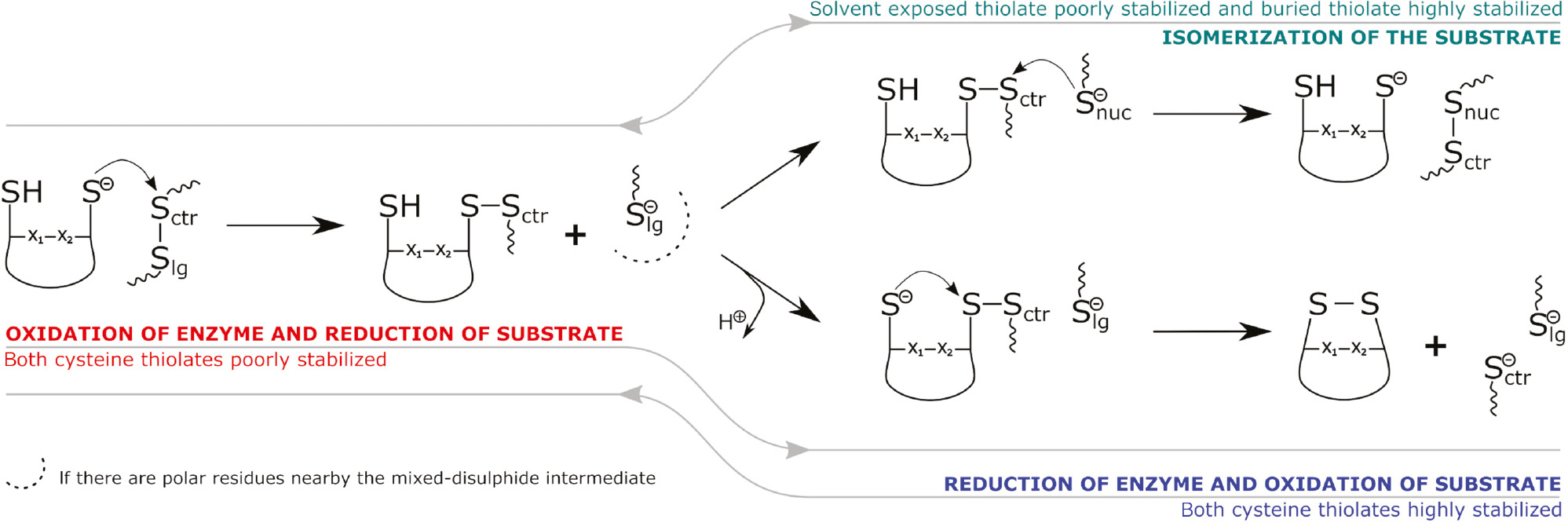

In 2008 and 2009 another breakthrough was reported (Carvalho et al., 2008, 2009) which established that a fine tuning of the nucleophilicity of both cysteines in the active site was the cause of which type of reaction the enzyme catalyzed. This was contrary to what was assumed then, i.e. that differentiation of catalysis was achieved through a different stabilization of the solvent exposed cysteine. However, in the newly established pattern, even though there seemed to be no doubt as to the fact that oxidant enzymes have both cysteine thiolates highly stabilized and reductant enzymes have both cysteine thiolates poorly stabilized, the mechanism of isomerization remained poorly understood then with the assumption that it could occur through more than just one pathway, with isomerases having one thiolate (solvent exposed) poorly stabilized and the other one (buried) thiolate highly stabilized.

Finally, in 2017, this pattern was partly verified as well as completed, with the work of Neves and co-workers (Neves et al., 2017) on the mechanism of PDI, which was in agreement with the predicted beforehand but clarified the isomerases role.

There is large evidence that thiol-disulfide exchange and thiol-oxidation/reduction processes are controlled kinetically, not thermodynamically (Sevier and Kaiser, 2002; Hogg, 2003; Carvalho et al., 2008; Bošnjak et al., 2014; Neves et al., 2017, Putzu et al., 2018). This means that the specific pathways followed are mainly a result from the relative reaction rates, which are carefully controlled by specific enzymes.

Functional role of the different families

As pointed out beforehand, thioredoxin (Trx) was the first enzyme found to catalyze the thiol-disulfide exchange (Laurent et al., 1964). It is a small monomeric protein with a molecular weight of around 12–13 kDa and was initially discovered in Escherichia coli, as a hydrogen donor for ribonucleotide reductase (Laurent et al., 1964), but present in many organisms, including plants, bacteria and mammals. This Trx gave the name to the thioredoxin structural superfamily, which contains a large array of enzymes, with a very marked degree of structural similarity, and characteristic tertiary structure, called the Trx fold. This global fold encompasses five stranded β-sheet flanked by four helices (β–α–β–α–β–α–β–β–α). However, the amino acid sequence can vary significantly among different enzymes in this superfamily. The thioredoxin structural family includes many enzymes such as Trx 1 and 2, glutaredoxins 1, 2, 3 (GrxA, GrxB, GrxC), and many eukaryotic proteins from the PDI family, such as PDI, Erp57, PDIp, P5, Erp72 and PDIR (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c). From these, Trx, Grx and PDI constitute the most representative subfamilies of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases in mammals, and they have been widely studied in the search for global patterns that may explain their different functions in light of their similar structure.

Characteristic among Trx enzymes is a CX1X2C motif at the active site, which encloses two catalytically active cysteine residues. In the CX1X2C motif, the two center amino acid residues X1X2 can be any and are usually different from each other. The nomenclature CXYC is used in the literature sometimes but Y should not be confused with the one-letter amino acid residue code Y, i.e. tyrosine. The most N-terminal cysteine residue, called nucleophilic cysteine, is largely exposed to the solvent, and typically deprotonated at physiological pH, while the other cysteine is buried into the protein chain and protonated (Lai et al., 2011). Different enzymes in this family have different amino acids in their CX1X2C motif, differing also in terms of characteristic pKa values for the nucleophilic cysteine and redox potentials. Trx itself has a CGPC motif (Figure 1), with the nucleophilic and buried cysteines residue positions 32 and 35, different from that characteristic of the other subfamilies (glutaredoxin and PDIs). In fact, in glutaredoxin these cysteines occupy the residue positions 22 and 25, with the enzymes adopting a CPYC motif, while in PDI they correspond to the positions 53 and 56 (CGHC motif) (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c). Another characteristic structural feature of the TRX-fold common to these enzymes is the presence of a cis-Pro loop close to the CX1X2C motif, which results in the approximation of a proline, important for substrate recognition (Gruber et al., 2006; Netto et al., 2016).

Representation of the CX1X2C motif for the most common thioredoxin-like enzymes discussed in the literature.

From left to right: thioredoxin (Trx), glutaredoxin (Grx) and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). The X1X2 variable motif is outlined in black lines. CysN and CysC stand for the nucleophilic (N-terminal) and buried (C-terminal Cys).

The Grx system was firstly described by Holmgren to be an alternative electron donor to ribonucleotide reductase in E. coli mutants lacking Trx (Holmgren, 1976). Grxs can also act both as electron donors and as regulators of cellular function in response to oxidative stress. Furthermore, they play a role in the dehydroascorbate reduction (Wells et al., 1990), and the regulation of cellular differentiation (Takashima et al., 1999), sulfur assimilation (Lillig et al., 1999), apoptosis (Chrestensen et al., 2000) and transcription (Bandyopadhyay et al., 1998). Grxs were also detected within HIV-1 and were proven to regulate the activity of glutathionylated HIV-1 protease in vitro (Davis et al., 1997). They are small proteins, usually around 9–15 kDa (Berndt et al., 2008), and they catalyze the reduction of oxidized diglutathione (GSSG) to a reduced GSH (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c) via a mechanism that includes a mixed-disulfide between Grx and substrate (Aslund et al., 1997; Adachi et al., 2004). Grxs can be divided into two major categories based on their active site motifs: the dithiol Grxs with active site motif CPYC and the monothiol Grxs with active site motif CPYS (Herrero and de la Torre-Ruiz, 2007, Lillig et al., 2008). The monothiol Grx can be further subdivided into single- and multi-domain Grxs (Herrero and de la Torre-Ruiz, 2007, Lillig et al., 2008). The multi-domain Grxs have not yet been identified in bacteria while both dithiol and single-domain monothiol Grxs are found in all forms of life like bacteria, plants and vertebrates (Lillig and Berndt, 2013). In particular, monothiol Grxs from E. coli, yeast and vertebrates, including humans, are crucially involved in iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis and regulation of iron homeostasis (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al., 2002). Another Grx division called CC-type Grx has proline in the second position replaced with cysteine (CCYC/S), and this is solely found in land plants (Xing et al., 2006).

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) is a multifunctional enzyme that catalyzes disulfide bond formation, cleavage and isomerization in eukaryotic cells. It is composed of 4 Trx-like domains (a, b, b′, and a′) (Wang et al., 2013), but only the a- and a′-domains present a CGHC motif that confers catalytic activity (Edman et al., 1985). The remaining domains exhibit hydrophobic patches that confer affinity to bind to several protein substrates, and are thus involved in its chaperone activity (Klappa et al., 1997). Even though, the catalytic domains of PDI can function independently, PDI’s maximum activity is achieved when all four domains contribute synergistically to catalysis (Darby et al., 1998). The main physiological function of PDI is in the secretory protein pathway, where it is a rate-limiting enzyme in the isomerization of native disulfides for the synthesis of functional proteins (Sevier and Kaiser, 2002). In addition, PDI is also an important regulator of the glutathione (GSH/GSSG) and hydrogen peroxide redox buffers of the endoplasmic reticulum (Tu and Weissman, 2004). In fact, recent studies showed that deletion of PDI leads to unbalance in the redox buffers of cells, which develops unfolded protein response phenomena (Tu and Weissman, 2004). The latter has been referred to be a precursor of diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or type-II diabetes (Benham, 2012). Additionally, PDI is frequently overexpressed in cancer cells and it has been regarded as a potential target in cancer treatment (Xu et al., 2014).

Mechanistic aspects

Thioredoxin

In Trx, the experimental pKa of the nucleophilic cysteine has been determined to vary between 6.3 and 7.1 (Dyson et al., 1991; Langsetmo et al., 1991; Forman-Kay et al., 1992; Chivers et al., 1997; Mossner et al., 1998; Moutevelis and Warwicker, 2004; Cheng et al., 2011) with a redox potential of ca. 270 mV (Miranda-Vizuete et al., 1997). The catalytic cycle of Trx is considered to occur in three main stages: (1) attack of the target disulfide by the active-site nucleophilic cysteine (CysN) resulting in a transient mixed disulfide between Trx and the target disulfide; (2) formation of an intramolecular disulfide bond by attack of the C-terminal buried cysteine (CysC) residue with reduction of the substrate; (3) regeneration of the reduced state of Trx by NADPH-dependent Trx reductase.

The first step of the mechanism has been shown to depend on the pKa value of CysN from the CX1X2C motif, which is typically around 7 (Dyson et al., 1991; Dillet et al., 1998). The lowering of the pKa is a consequence of the stabilization of the negative charge at the free thiolate through hydrogen bonding with neighboring residues (Foloppe et al., 2001).

Neighboring Asp and Lys amino acid residues, located in the vicinity of the two catalytic cysteine residues have been implicated in catalysis (Eklund et al., 1984; Collet and Messens, 2010; Netto et al., 2016). These residues help to define a charged region shielded from the environment located between the β2- and β3-strands and the α2-helix turn. In particular the Asp residue has been associated to activation of the CX1X2C motif as a nucleophile (Chivers et al., 1997; Menchise et al., 2001; Roos et al., 2009).

Trx has also two important conserved prolines, in addition to the proline residue that constitutes the characteristic CGPC motif. The latter determines the reducing power of the Trx enzymes, having a dramatic impact on the redox properties of the protein, well portrayed in mutagenesis studies involving Ser or Thr mutants (Gleason et al., 1990; Krause et al., 1991; Chivers et al., 1997; Mossner et al., 1998; Schultz et al., 1999; Roos et al., 2007; Lewin et al., 2008). One Pro occupies a position in the primary sequence of Trx, five residues after the CX1X2C, motif and is responsible for inducing a bend in the corresponding helix (α2-helix), important for the stabilization of the Trx-fold (de Lamotte-Guery et al., 1997; Chakrabarti et al., 1999). The third conserved Pro residue occupies a position around the active-site that is located opposite to the CX1X2C motif, adopting a conserved cis-conformation and playing an important role, both in terms of structure and redox potential (Gleason, 1992). A conserved Thr residue is also present near the third Pro and opposite to the CX1X2C motif, playing also an important structural role (Eklund et al., 1991). Similarly, a Trp residue located immediately before the CX1X2C sequence motif makes an important contribution to the thermodynamic stability of the enzyme (Garcia-Pino et al., 2009).

We have applied computational QM/MM methods to compare the dithiol groups in Trx and DsbA, and to rationalize the pKa difference of 4.5 existing between the nucleophilic cysteines of the two very similar homologous enzymes (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c). Our calculations indicated that the main factor responsible for this difference was the position of the α2-helices, which stabilized much more the CysN thiolate in DsbA than in Trx. Furthermore, double mutation by Ala of the Asp and Lys residues located in the vicinity of the two catalytic cysteines (Asp26/Lys57 in Trx, and Glu24/Lys58) that have been implicated in catalysis did not change the calculated pKa values, suggesting that these residues are not involved in the differentiation of properties of the active site dithiol. The calculations have also shown that the X1X2 residues at the CX1X2C motif did not promote differential thiolate stabilization.

We also explored the activation (deprotonation) of the buried thiol (with a pKa>9) (Kallis and Holmgren, 1980; Chivers et al., 1997; Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c; Cheng et al., 2011) and the role of the variable active-site residues, using density functional theory (DFT) and classical molecular dynamics (MD) (Carvalho et al., 2008). Our calculations suggested that the deprotonation of the buried thiol, which is required before the second SN2 step, can occur directly after the first SN2 step through proton abstraction by the thiolate leaving group, which is released in the vicinity of the thiol group of the buried Cys35. Furthermore, the application of MD simulations also helped to demonstrate the importance of a number of amine N-H groups in the stabilization of the nucleophilic Cys32 thiolate and the importance of structural rigidity in the X1X2 motif of Trx for activity.

Glutaredoxin

Grx have been widely studied through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography (Eklund et al., 1992; Xia et al., 1992). There are over 100 structures of Grxs from different organisms like Homo sapiens, E. coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, etc. in the protein databank. In bacterial Grxs, the structure contains four stranded β-sheets that are surrounded by three α-helices while other Grx types from yeast or human consist of four stranded β-sheets surrounded by five α-helices. The central β-sheet is composed of three antiparallel strands (β1, β3, β4) with β2 parallel to the adjacent β1. The active site motif is located on the loop connecting β1 and α1 (Figure 2). The CysN in the Grx active site is similar to Trxs, surface-exposed with low pKa (3.8) (Tagaya et al., 1989; Yang and Wells, 1991), while the CysC is buried in the molecule and has a much higher pKa value (>10.5) (Lillig et al., 2008; Roos et al., 2013).

(Left) Grx structure from human showing the 4 stranded β-sheets, the 5 α-helices; the position of the Cys-Pro-Tyr-Cys active site motif is marked with a small rounded rectangle; (right) structural representation of the reactant state in the catalytic mechanism of Grx, illustrating the CPYC motif in the reduction of glutathione disulfide.

The CysN thiolate has been reported to be stabilized by the electrostatic interaction with the positively charged residue (Lys20) in the active site region and also by the backbone amines of Tyr25 and Cys26, as well as the Cys26 thiol group (Figure 2). In fact, mutating Lys20 by Gln resulted in loss of catalytic activity due to an increase in the pKa value of the N-terminal Cys thiol (Jao et al., 2006). Human Grxs have two additional helices located at the N- and C-termini, and three additional solvent-exposed Cys residues (Cys8, Cys79 and Cys 83) in addition to those present in the active site (Sun et al., 1998). The exact role of these cysteines is yet to be established (Sun et al., 1998), but they are proposed to play a regulatory role because their oxidation leads to inactivation of the protein (Klintrot et al., 1984).

The catalytic mechanism of Grxs depends on the type of Grx. Monothiol Grx utilizes the CysN to reduce the protein substrate-GSH mixed disulfide, while dithiol Grx uses both active site cysteines to reduce the GSSG-disulfide through thiol-disulfide exchange (Ukuwela et al., 2018). Grx-catalyzed thiol-disulfide exchange reaction provides a means for thiol and disulfide redistribution in the cell (Axelsson and Mannervik, 1980). Studies have shown that the catalytic activity of Grx is specific for glutathionyl mixed-disulfide substrates because other nonglutathionyl disulfides react much more slowly (Bushweller et al., 1992; Rabenstein and Millis, 1995; Gallogly et al., 2009), leading to the conclusion that the γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl moiety of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and of the GSH-containing mixed disulfide are an important structural feature in their thiol-disulfide exchange reaction by Grx (Rabenstein and Millis, 1995).

The thiol-disulfide exchange catalyzed by Grx is also proposed to proceed via an SN2 transition state like other Trx enzymes, where the CysN thiolate group nucleophilically attacks a disulfide bond along the sulfur-sulfur axis to form the Grx-SSG intermediate. Thereafter, the Grx-SSG intermediate can either react with a molecule containing a thiol group (such as GSH) to regenerate the reduced form of Grx and the oxidized substrate, or undergo an intramolecular oxidation using the thiol group of CysC to form the oxidized Grx (GrxS2) and another molecule of GSH. The latter reaction is more favorable than the former due to the proximity of the CysC to the intermediate; however, this reactivity could be offset if the orientation of the CysC thiol relative to the Grx-SSG intermediate is unfavorable (Gallogly et al., 2009).

Protein disulfide isomerase

PDI can function primarily as an oxidoreductase by performing thiol-disulfide exchange in the GSH/GSSG buffer and in several protein substrates. However, the main function of PDI is to perform the isomerization of disulfide bonds in proteins during oxidative folding to produce functional proteins. Furthermore, PDI exhibits chaperone activity, which is critical during oxidative protein folding.

Experimental evidence regarding the chemical properties of its CGHC motif indicates that the CysN exhibits a lower pKa (~4.5) than that of equivalent Cys in Trx-like folds, while CysC exhibits a much higher pKa (~12.8) (Lappi et al., 2004). In addition, it is most often found in the reduced state (Appenzeller-Herzog and Ellgaard, 2008).

Consequently, the catalytic cycle of PDI as an isomerase is proposed to occur in two main stages: (1) formation of a mixed-disulfide PDI:substrate through nucleophilic attack of CysN on the CGHC motif to a non-native disulfide of a misfolded protein; and (2) cleavage of the mixed-disulfide intermediate by intramolecular oxidation or by another protein Cys or foreign thiolate species (Lappi and Ruddock, 2011).

We recently published a detailed proposal for the reductase mechanism of the a-domain of human PDI obtained by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, with atomistic resolution (Neves et al., 2017). We studied the reduction of GSSG, which is the simplest substrate of PDI and an important molecule in the cell’s redox buffers, to GSH.

The formation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate takes place through an SN2 nucleophilic substitution that we have extensively studied (Fernandes and Ramos, 2004; Neves et al., 2014, 2017), where the CysN (Cys53) is placed in line with the GSSG-disulfide. The Gibbs activation energy was determined to be 18.7 kcal·mol−1, in good agreement with the experimentally determined barrier of 17.6 kcal·mol−1 (Lappi and Ruddock, 2011). We also confirmed that the reaction is actually thermodynamically regulated, because the number of hydrogen bond donors in the immediacy of the leaving GSH product (at least two) is a requisite to observe a transition state for the reaction.

The analysis of the transition state disclosed the importance of the CGHC motif for the reaction (Figure 3). The state is dominated by the antisymmetric stretching of the three inline sulfur atoms; however, it is clear that there are two hydrogen bonds between the backbone of Gly54 and His55 and the CGHC nucleophilic sulfur that weaken considerably as the mixed-disulfide intermediate is formed. This fact emphasizes that these interactions should be critical to stabilize the nucleophilic Cys. We also observed that the neutral ionization state of His55 plays an important role in GSSG binding, while the positively charged ionization state precludes the formation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate.

Depiction of the structure, active site and reaction mechanism of PDI.

(Top left) The four Trx-like domains of the human PDI in the oxidized state (cartoon), and the catalytic CGHC motif on a- and a′-domains (ball and stick, and detailed in the top right); (top right) catalytic competent active site of the a-domain of human PDI with a peptide-like substrate (oxidized glutathione); (bottom) Gibbs energy profile for the formation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate between the N-terminal Cys53 and the disulfide of the substrate, and the intramolecular oxidation of the a-domain of PDI by the C-terminal Cys56.

Once the mixed-disulfide intermediate is produced, it can be easily reduced by neighboring nucleophilic sulfurs (ΔG‡ ~ 8 kcal·mol−1). Alternatively, we confirmed that the CysC of CGHC (Cys56) can also be easily deprotonated by the neighboring Glu47, via a water molecule, with minor structural rearrangements, leading to a thermodynamically stable intermediate. At this state, intramolecular oxidation is favored and occurs moderately fast through thiol-disulfide exchange through the attack of Cys56 to the mixed disulfide (ΔG‡<7.2 kcal·mol−1), depending on whether there are polar species that can stabilize the second leaving GSH, thus preventing the formation of trapped mixed-disulfides. From the comparison of both thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, we also proposed that the kinetic barrier for the reaction is highly-dependent on the number of hydrogen bond donors to the nucleophilic Cys (three for the formation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate and two for its cleavage).

Contrarily to what is predicted in the literature (Lappi and Ruddock, 2011), the formation of the mixed-disulfide intermediate seems to be the rate-limiting step of the reaction mechanism of PDI. Our results are also supported by mutagenesis studies that state that the activity of PDI is slightly reduced, but not compromised, upon mutation of Cys56 by Ser (Walker et al., 1996; Kersteen et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the actual isomerization rate of PDI is lower than the rate of thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, and the relative efficiency of each of its catalytic sites is dependent of the substrate and the synergistic effects in its environment (Darby et al., 1998).

Even though our study was the first one to study the nature of the reaction mechanism of PDI, further clarification is required on the full mechanism of disulfide isomerization by PDI during protein oxidative folding. In this regard, we highlight the clarification of PDI’s chaperone activity, its action in the prevention of protein aggregation, or the mapping of its domains for substrate binding. Past studies (mostly using NMR) determined that the b′-domain is mostly responsible for the binding affinity of PDI towards protein substrates, proposing some residues responsible for substrate binding (Pirneskoski et al., 2004; Byrne et al., 2009). However, only recently the mapping of the b- and b′-domains of PDI with a protein substrate along its folding stages was performed (Irvine et al., 2014). Upon the deposit of the first X-ray structures of human PDI (Wang et al., 2013), the oxidation of the a′-domain of PDI is also proposed to contribute to the chaperone activity.

Rationalization of the differences between the pKa of CysN in enzymes of the thioredoxin superfamily

Over the years many theories have been put forward to explain and rationalize the different reactivity patterns of Trx, Grx and PDI enzymes, particularly in terms of the different redox and pKa ranges (Roos et al., 2013). It is well known that the pKa of a Cys thiol can be strongly influenced by the surrounding protein environment. A variety of effects have been suggested including steric tension, the nature of the X1X2 amino acid residues, specific residues around the active site, charge-charge interactions, hydrogen bonds, aqueous desolvation and even helix-dipole effects (Nielsen et al., 2001; Harris and Turner, 2002; Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c; Roos et al., 2013).

Steric tension

One of these hypotheses is the enzyme’s steric tension. Thiol-disulfide exchange reactions occur through transition states presenting a quasi-linear geometry, typical for a SN2 reaction. It has been argued that steric factors at the active site could induce a strain around the disulfide, shifting the Cys-S-S-Cys dihedral angles from 90°. However, the high degree of structural similarity between the different enzymes in the family forecloses any direct correlation between the activity and the structural features associated to steric tension in these enzymes. The values for the two thiol bond angles are typically between 105–115°, with dihedrals in the range 60–90° and disulfide bond-lengths between 2.02 and 2.08 Å for all members of the family (Katti et al., 1990, 1995; Eklund et al., 1992; Jeng et al., 1994).

Alpha-helix

The pKa control of the CX1X2C motif in Trx-like enzymes was also related to its interaction with the α1-helix where the catalytic motif is included. This stabilizing effect is proposed to result from the interaction of the CysN-thiolate of CX1X2C and the dipole of the α1-helix, as well as from hydrogen bonds formed with neighboring residues (Guddat et al., 1998). In fact, computational studies by Roos and co-workers emphasized that this stabilization is mostly promoted by hydrogen bonds at the N-terminus of α-helices, and it seems to be more pronounced with a larger number of turns in the helix (Roos et al., 2006). In addition, a recent computational study also emphasized that Cys residues closer to the N-terminus of α-helices often exhibit lower pKas and higher nucleophilicity (Fowler et al., 2017).

Kortemme and coworkers proposed that this stabilization could decrease the pKa of Cys-thiols in ca. 1.5–2.1 units, which could explain the pKa of the CysN of Trx but would not explain differences up to 5 units observed among the thioredoxin family (Kortemme and Creighton, 1995). Later studies by Iqbalsyah and co-workers also verified that the deprotonated form of Cys is favored in helicoidal peptides, but again refer that other interactions should be required to lower the pKa of Cys to values close to the observed in DsbA or PDI (Iqbalsyah et al., 2006). On the same trend, Carvalho and co-workers (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c) obtained similar results, but first discussed the effect of this helix on the differentiation of enzyme function. Later, the contribution of the α1-helix for the increased reducing power of Trx was shown to be significant and dependent on the nature of the residues in the α1-helix, quickly converging upon increasing Ala mutations (Dumont et al., 2008).

Specific amino acid residues

Several pieces of evidence indicate that the presence of specific amino acid residues around the active site can result in a stronger or weaker stabilization of the nucleophilic Cys, affecting the pKa of this Cys in the different enzymes.

For example, in Trx, the ionization state and corresponding charge present at Asp26 was proposed to influence the pKa of the nucleophilic Cys (Kallis and Holmgren, 1980; Holmgren, 1985). Mutation Asp26Ala, Lys57Met and Asp26Ala/Lys57Met resulted in significant changes of the active site’s Cys thiol, particularly its nucleophilicity (Dyson et al., 1997), confirming the relevance of Asp26, but also of the Lys57···Asp26 pair, for the active site thiols. Conserved Asp and Lys residues at these positions were also found for PDIs, but not in glutaredoxin, where they were substituted by valine and Phe residues.

An additional study by Dyson and co-workers examined the pH-dependent behavior of Trx (Dyson et al., 1991, 1994). The authors showed that in addition to the two active-site Cys thiol groups, there was an additional group around the active site titrated over the same pH range. This behavior was attributed to Asp26, which through a salt bridge/hydrogen bond with Lys57 could promote Trx activity by providing both a source and sink for protons in the hydrophobic cavity that would serve as binding pocket for Trx substrates (Jeng and Dyson, 1996). More recently, we also observed that a Glu47 (in the same position as Asp26 in Trx) could control the protonation of CysC in PDI, promoting oxidation of the CGHC motif (Neves et al., 2017). However, no equivalent could be found in Grx.

More recently, Lafaye and co-workers observed that mutations that decreased the number of hydrogen bonds to the nucleophilic Cys of DsbG improved the activity of these enzymes towards nitrosylated thiols (Lafaye et al., 2016).

CX1X2C motif

A natural difference between the three active sites lies in the identity of the amino acid residues that constitute the X1X2 in the CX1X2C motif characteristic of the different enzymes. While in Trx the X1X2 motif is defined by a Gly and a Pro residue (CGPC), in Grx it is occupied by a Pro and a Tyr (CPYC), while in PDI it is played by a Gly and a His (CGHC) (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c).

Interestingly, mutating the -Gly-Pro- peptide of Trx by the -Pro-Tyr- and -Gly-His- of glutaredoxin and PDI, resulted in a change in the redox potential in a direction that paralleled the expected change for the wild type enzymes (Mossner et al., 1998; Lafaye et al., 2016). However, the magnitude of that effect was still far from the values of the corresponding wild type values (Mossner et al., 1998). Furthermore, Siedler and co-workers (Siedler et al., 1993, 1994) showed that all the octapeptides with the CX1X2C motif of Trx, Grx and PDI exhibited a redox potential of −0.20 V, which again suggested that redox potential is not solely determined by the CX1X2C motif.

Other authors have proposed that a hydrogen bond/proton sharing from the buried CysC to CysN could also modulate the pKa of CysN; however computational studies by Carvalho and co-workers (Carvalho et al., 2006a,b,c) provided that CysC exhibits a much higher pKa than CysN (~14 vs. 7.5).

Most consistent pieces of evidence point out that the number of hydrogen bond donors to the reactive Cys seems to be the closest to a unifying pattern among the thioredoxin-like family (Roos et al., 2013; Lafaye et al., 2016). In the past, we have discussed the effect of the stabilization of CysN and CysC on the function of Trx-like enzymes, namely by the X1X2 motif and the local enzyme environment (Carvalho et al., 2009). The work by Carvalho and co-workers proposed that the disulfide reducing, oxidizing or isomerizing function of these enzymes is fundamentally driven by the relative stabilization of the catalytic cysteines in the CX1X2C motif: while reductant enzymes possess less stabilized CysN and CysC, oxidant ones exhibit more stabilized CysN and CysC. Later, we were able to propose the isomerization mechanism by PDI and discuss all functions of these enzymes (Neves et al., 2017). While studying the mechanism of GSSG reduction by PDI, we again observed that two short hydrogen bonds from the backbone of His55 and Cys56 in CGHC favor the reduced state of the active over the oxidized state. The pKa of CysN in PDI (~4.4–6.7) (Hatahet and Ruddock, 2009) resembles that of Grx (where -Gly-His- is replaced by -Pro-Tyr-) or DsbA (which presents a -Pro-His- peptide), all of which present a similar hydrogen bond network, as opposed to that of Trx (-Gly-Pro- peptide) where only the CysC-backbone donate a hydrogen bond to CysN (Foloppe et al., 2001).

Conclusions and outlook

This work focuses on the mechanistic and structural aspects of disulfide bond formation in biological systems through thiol-disulfide exchange by Trx-like proteins. Disulfide bonds, which are often derived from two thiol groups coupling in proteins, are of great importance in protein folding and stabilization, and on the redox regulation of cells, in particular at the endoplasmic reticulum. Thioredoxin family proteins like Trx, Grx, and PDI, which are known to be involved in the formation, transfer or isomerization of disulfide bonds via thiol-disulfide exchange reaction are emphasized. This important reaction is involved in several biological processes ranging from gene expression/regulation and catalytic activity, to protein folding and stability.

Table 1 summarizes some characteristics of Trx, Grx and PDI. The CX1X2C active site motif conserved in the family, and the reactivity of the thiol sulfur is highly dependent on the Cys pKa value, as a lower pKa affects both nucleophilicity and leaving group ability of the associated thiolate. Although the pKa of nucleophilic CysN is lower than that of free Cys in solution, the value varies intriguingly depending on the Trx-like protein. These pKa values clearly contribute to the redox properties of the thioredoxin family proteins. In addition, the nature of X1X2 residues in the CX1X2C motif has key influence on the CysN pKa, contributing to why some of the proteins act as reductants, while others are more efficient oxidants. The effect of these two residues can be mostly understood based on the number hydrogen bonds that they can provide to stabilize the CysN-thiolate, which greatly affects the standard redox potential of the family. Finally, we gathered knowledge that could provide a rationale for the function of Trx-like enzymes and the CX1X2C motif: we proposed that more stabilized catalytic cysteines favor disulfide oxidation and less stabilized ones favor disulfide reduction, while disulfide isomerization depends on the availability of protein thiolates nearby the active site that may solve mixed-disulfide intermediates to form new protein disulfides, as opposed to the rescue of trapped mixed-disulfides through the intramolecular oxidation mechanism.

Main features of the most studied Trx-like proteins: thioredoxin, glutaredoxin and protein disulfide isomerase.

| Protein name | CysN-X1-X2-CysC | pKaCysN | pKaCysC | E0 (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thioredoxin (Trx) | CysN-Gly-Pro-CysC | 6.3–7.1 | >9.0 | −270 |

| Glutaredoxin (Grx) | CysN-Pro-Tyr-CysC | ~3.8 | >10.5 | −200/−230 |

| Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) | CysN-Gly-His-CysC | 4.4–6.7 | 12.8 | −180 |

Figure 4 summarizes all that has been said, establishing the extraordinary behavior of both cysteines from the CX1X2C motif in the active center of the enzymes that belong to the thioredoxin family.

Reaction mechanisms performed by Trx-like enzymes.

Summary of the reactions involved in disulfide bond oxidation, reduction or isomerization through thiol-disulfide exchange by the CX1X2C motif of Trx-like enzymes.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from European Union (FEDER funds POCI/01/0145/FEDER/007728) and National Funds (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação e Ciência – FCT/MEC) UID/MULTI/04378/2013, under the Partnership Agreement PT2020; NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000024, supported by Norte Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The authors would also like to thank Fundação para a Ciencia e a Tecnologia (FCT) (IF/00052/2014). The authors would also like to thank the Erasmus Mundus Programme of the European Master in Theoretical Chemistry and Computational Modelling (EMTCCM) with the support of the European Union for the Erasmus+scholarship awarded to Sodiq O. Waheed.

References

Adachi, T., Weisbrod, R.M., Pimentel, D.R., Ying, J., Sharov, V.S., Schoneich, C., and Cohen, R.A. (2004). S-Glutathiolation by peroxynitrite activates SERCA during arterial relaxation by nitric oxide. Nat. Med. 10, 1200–1207.10.1038/nm1119Suche in Google Scholar

Alegre-Cebollada, J., Perez-Jimenez, R., Kosuri, P., and Fernandez, J.M. (2010). Single-molecule force spectroscopy approach to enzyme catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18961–18966.10.1074/jbc.R109.011932Suche in Google Scholar

Appenzeller-Herzog, C. and Ellgaard, L. (2008). In vivo reduction-oxidation state of protein disulfide isomerase: the two active sites independently occur in the reduced and oxidized forms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 55–64.10.1089/ars.2007.1837Suche in Google Scholar

Aslund, F., Berndt, K.D., and Holmgren, A. (1997). Redox potentials of glutaredoxins and other thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases of the thioredoxin superfamily determined by direct protein-protein redox equilibria. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30780–30786.10.1074/jbc.272.49.30780Suche in Google Scholar

Axelsson, K. and Mannervik, B. (1980). General specificity of cytoplasmic thioltransferase (thiol:disulfide oxidoreductase) from rat liver for thiol and disulfide substrates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 613, 324–336.10.1016/0005-2744(80)90087-XSuche in Google Scholar

Bandyopadhyay, S., Starke, D.W., Mieyal, J.J., and Gronostajski, R.M. (1998). Thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) reactivates the DNA-binding activity of oxidation-inactivated nuclear factor I. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 392–397.10.1074/jbc.273.1.392Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Benham, A.M. (2012). The protein disulfide isomerase family: key players in health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 781–789.10.1089/ars.2011.4439Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Berndt, C., Lillig, C.H., and Holmgren, A. (2008). Thioredoxins and glutaredoxins as facilitators of protein folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 641–650.10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.02.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Bošnjak, I., Bojović, V., Šegvić-Bubić, T., and Bielen, A. (2014). Occurrence of protein disulfide bonds in different domains of life: a comparison of proteins from the Protein Data Bank. Prot. Eng. Sel. 27, 65–72.10.1093/protein/gzt063Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Bushweller, J.H., Aslund, F., Wuthrich, K., and Holmgren, A. (1992). Structural and functional characterization of the mutant Escherichia coli glutaredoxin (C14----S) and its mixed disulfide with glutathione. Biochemistry 31, 9288–9293.10.1021/bi00153a023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Byrne, L.J., Sidhu, A., Wallis, A.K., Ruddock, L.W., Freedman, R.B., Howard, M.J., and Williamson, R.A. (2009). Mapping of the ligand-binding site on the b′ domain of human PDI: interaction with peptide ligands and the x-linker region. Biochem. J. 423, 209–217.10.1042/BJ20090565Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Carvalho, A.T.P., Fernandes, P.A., and Ramos, M.J. (2006a). Similarities and differences in the thioredoxin superfamily. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 91, 229–248.10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.06.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Carvalho, A.T.P., Fernandes, P.A., and Ramos, M.J. (2006b). Determination of the Delta pKa between the active site cysteines of thioredoxin and DsbA. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 966–975.10.1002/jcc.20404Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Carvalho, A.T.P., Fernandes, P.A., and Ramos, M.J. (2006c). Theoretical study of the unusual protonation properties of the active site cysteines in thioredoxin. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 5758–5761.10.1021/jp053275fSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Carvalho, A.T.P., Fernandes, P.A., Swart, M., van Stralen, J.N.P., Bickelhaupt, F.M., and Ramos, M.J. (2009). Role of the variable active site residues in the function of thioredoxin family oxidoreductases. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 710–724.10.1002/jcc.21086Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Carvalho, A.T.P., Swart, M., van Stralen, J.N.P., Fernandes, P.A., Ramos, M.J., and Bickelhaupt, F.M. (2008). Mechanism of thioredoxin-catalyzed disulfide reduction. Activation of the buried thiol and role of the variable active-site residues. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 2511–2523.10.1021/jp7104665Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Chakrabarti, A., Srivastava, S., Swaminathan, C.P., Surolia, A., and Varadarajan, R. (1999). Thermodynamics of replacing an a-helical Pro residue in the P40S mutant of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Protein Sci. 8, 2455–2459.10.1110/ps.8.11.2455Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cheng, Z.Y., Zhang, J.F., Ballou, D.P., and Williams, C.H. (2011). Reactivity of thioredoxin as a protein thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase. Chem. Rev. 111, 5768–5783.10.1021/cr100006xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chivers, P.T., Prehoda, K.E., Volkman, B.F., Kim, B.M., Markley, J.L., and Raines, R.T. (1997). Microscopic pK(a) values of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 36, 14985–14991.10.1021/bi970071jSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Chrestensen, C.A., Starke, D.W., and Mieyal, J.J. (2000). Acute cadmium exposure inactivates thioltransferase (Glutaredoxin), inhibits intracellular reduction of protein-glutathionyl-mixed disulfides, and initiates apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26556–26565.10.1074/jbc.M004097200Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Collet, J.F. and Messens, J. (2010). Structure, function, and mechanism of thioredoxin proteins. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 13, 1205–1216.10.1089/ars.2010.3114Suche in Google Scholar

Darby, N.J., Penka, E., and Vincentelli, R. (1998). The multi-domain structure of protein disulfide isomerase is essential for high catalytic efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 276, 239–247.10.1006/jmbi.1997.1504Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, D.A., Newcomb, F.M., Starke, D.W., Ott, D.E., Mieyal, J.J., and Yarchoan, R. (1997). Thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) is detected within HIV-1 and can regulate the activity of glutathionylated HIV-1 protease in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25935–25940.10.1074/jbc.272.41.25935Suche in Google Scholar

de Lamotte-Guery, F., Pruvost, C., Minard, P., Delsuc, M.A., Miginiac-Maslow, M., Schmitter, J.M., Stein, M., and Decottignies, P. (1997). Structural and functional roles of a conserved proline residue in the alpha 2 helix of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Protein Eng. 10, 1425–1432.10.1093/protein/10.12.1425Suche in Google Scholar

Dillet, V., Dyson, H.J., and Bashford, D. (1998). Calculations of electrostatic interactions and pKas in the active site of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 37, 10298–10306.10.1021/bi980333xSuche in Google Scholar

Dumont, E., Loos, P.F., Laurent, A.D., and Assfeld, X. (2008). Huge disulfide-linkage᾽s electron capture variation induced by a-helix orientation. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 4, 1171–1173.10.1021/ct800161mSuche in Google Scholar

Dyson, H.J., Tennant, L.L., and Holmgren, A. (1991). Proton-transfer effects in the active-site region of e-coli thioredoxin using 2-dimensional H-1-NMR. Biochemistry 30, 4262–4268.10.1021/bi00231a023Suche in Google Scholar

Dyson, H.J., Jeng, M.F., Model, P., and Holmgren, A. (1994). Characterization by H-1-NMR of a C32S, C35S double mutant of e-coli thioredoxin confirms its resemblance to the reduced wild-type protein. FEBS Lett. 339, 11–17.10.1016/0014-5793(94)80375-7Suche in Google Scholar

Dyson, H.J., Jeng, M.F., Tennant, L.L., Slaby, I., Lindell, M., Cui, D.S., Kuprin, S., and Holmgren, A. (1997). Effects of buried charged groups on cysteine thiol ionization and reactivity in Escherichia coli thioredoxin: structural and functional characterization of mutants of Asp 26 and Lys 57. Biochemistry 36, 2622–2636.10.1021/bi961801aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Edman, J.C., Ellis, L., Blacher, R.W., Roth, R.A., and Rutter, W.J. (1985). Sequence of protein disulfide isomerase and implications of its relationship to thioredoxin. Nature 317, 267–270.10.1038/317267a0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Eklund, H., Cambillau, C., Sjoberg, B.M., Holmgren, A., Jornvall, H., Hoog, J.O., and Branden, C.I. (1984). Conformation and functional similarities between gluaredoxin and thioredoxins. EMBO J. 3, 1443–1449.10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01994.xSuche in Google Scholar

Eklund, H., Gleason, F.K., and Holmgren, A. (1991). Structural and functional relations among thioredoxins of different species. Proteins 11, 13–28.10.1002/prot.340110103Suche in Google Scholar

Eklund, H., Ingelman, M., Soderberg, B.O., Uhlin, T., Nordlund, P., Nikkola, M., Sonnerstam, U., Joelson, T., and Petratos, K. (1992). Structure of oxidized bacteriophage-T4 glutaredoxin (thioredoxin) – refinement of native and mutant proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 228, 596–618.10.1016/0022-2836(92)90844-ASuche in Google Scholar

Fernandes, P.A. and Ramos, M.J. (2004). Theoretical Insights into the mechanism for thiol/disulfide exchange. Chemistry 10, 257–266.10.1002/chem.200305343Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Foloppe, N., Sagemark, J., Nordstrand, K., Berndt, K.D. and Nilsson, L. (2001). Structure, dynamics and electrostatics of the active site of glutaredoxin 3 from Escherichia coli: comparison with functionally related proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 310, 449–470.10.1006/jmbi.2001.4767Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Forman-Kay, J.D., Clore, G.M., and Gronenborn, A.M. (1992). Relationship between electrostatics and redox function in human thioredoxin – characterization of Ph titration shifts using 2-dimensional homonuclear and heteronuclear NMR. Biochemistry 31, 3442–3452.10.1021/bi00128a019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Fowler, N.J., Blanford, C.F., de Visser, S.P., and Warwicker, J. (2017). Features of reactive cysteines discovered through computation: from kinase inhibition to enrichment around protein degrons. Sci. Rep. 7, 16338.10.1038/s41598-017-15997-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gallogly, M.M., Starke, D.W., and Mieyal, J.J. (2009). Mechanistic and kinetic details of catalysis of thiol-disulfide exchange by glutaredoxins and potential mechanisms of regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 1059–1081.10.1089/ars.2008.2291Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Garcia-Pino, A., Martinez-Rodriguez, S., Wahni, K., Wyns, L., Loris, R., and Messens, J. (2009). Coupling of domain swapping to kinetic stability in a thioredoxin mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 385, 1590–1599.10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.040Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Gleason, F.K. (1992). Mutation of conserved residues in Escherichia coli thioredoxin – effects on stability and function. Protein Sci. 1, 609–616.10.1002/pro.5560010507Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gleason, F.K., Lim, C.J., Geraminejad, M., and Fuchs, J.A. (1990). Characterization of Escherichia coli thioredoxins with altered active-site residues. Biochemistry 29, 3701–3709.10.1021/bi00467a016Suche in Google Scholar

Gruber, C.W., Cemazar, M., Heras, B., Martin, J.L., and Craik, D.J. (2006). Protein disulfide isomerase: the structure of oxidative folding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 455–464.10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.001Suche in Google Scholar

Guddat, L.W., Bardwell, J.C.A., and Martin, J.L. (1998). Crystal structures of reduced and oxidized DsbA: investigation of domain motion and thiolate stabilization. Struct. Fold. Des. 6, 757–767.10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00077-XSuche in Google Scholar

Harris, T.K. and Turner, G.J. (2002). Structural basis of perturbed pK(a) values of catalytic groups in enzyme active sites. IUBMB Life 53, 85–98.10.1080/15216540211468Suche in Google Scholar

Hatahet, F. and Ruddock, L.W. (2009). Protein disulfide isomerase: a critical evaluation of its function in disulfide bond formation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2807–2850.10.1089/ars.2009.2466Suche in Google Scholar

Herrero, E. and de la Torre-Ruiz, M.A. (2007). Monothiol glutaredoxins: a common domain for multiple functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 1518–1530.10.1007/s00018-007-6554-8Suche in Google Scholar

Hogg, P.J. (2003). Disulfide bonds as switches for protein function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 210–214.10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4Suche in Google Scholar

Holmgren, A. (1976). Hydrogen donor system for Escherichia coli ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase dependent upon glutathione. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73, 2275–2279.10.1073/pnas.73.7.2275Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Holmgren, A. (1985). Thioredoxin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 54, 237–271.10.1002/047120918X.emb1542Suche in Google Scholar

Iqbalsyah, T.M., Moutevelis, E., Warwicker, J., Errington, N., and Doig, A.J. (2006). The CXXC motif at the N terminus of an a-helical peptide. Protein Sci. 15, 1945–1950.10.1110/ps.062271506Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Irvine, A.G., Wallis, A.K., Sanghera, N., Rowe, M.L., Ruddock, L.W., Howard, M.J., Williamson, R.A., Blindauer, C.A., and Freedman, R.B. (2014). Protein disulfide-isomerase interacts with a substrate protein at all stages along its folding pathway. PLos One 9, e82511.10.1371/journal.pone.0082511Suche in Google Scholar

Jao, S.C., English Ospina, S.M., Berdis, A.J., Starke, D.W., Post, C.B., and Mieyal, J.J. (2006). Computational and mutational analysis of human glutaredoxin (thioltransferase): probing the molecular basis of the low pKa of cysteine 22 and its role in catalysis. Biochemistry 45, 4785–4796.10.1021/bi0516327Suche in Google Scholar

Jeng, M.F. and Dyson, H.J. (1996). Direct measurement of the aspartic acid 26 pK(a) for reduced Escherichia coli thioredoxin by C-13 NMR. Biochemistry 35, 1–6.10.1021/bi952404nSuche in Google Scholar

Jeng, M.F., Campbell, A.P., Begley, T., Holmgren, A., Case, D.A., Wright, P.E., and Dyson, H.J. (1994). High-resolution solution structures of oxidized and reduced Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Structure. 2, 853–868.10.1016/S0969-2126(94)00086-7Suche in Google Scholar

Kallis, G.B. and Holmgren, A. (1980). Differential reactivity of the functional sulfydryl groups of cysteine-32 and cysteine-35 present in the reduced form of thioredoxin from E. coli. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 261–265.10.1016/S0021-9258(19)70458-XSuche in Google Scholar

Katti, S.K., Lemaster, D.M., and Eklund, H. (1990). Crystal-structure of thioredoxin from Escherichia coli at 1.68 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 212, 167–184.10.1016/0022-2836(90)90313-BSuche in Google Scholar

Katti, S.K., Robbins, A.H., Yang, Y.F., and Wells, W.W. (1995). Crystal structure of thioltransferase at 2.2 Ångstrom resolution. Protein Sci. 4, 1998–2005.10.1002/pro.5560041005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kersteen, E.A., Barrows, S.R., and Raines, R.T. (2005). Catalysis of protein disulfide bond isomerization in a homogeneous substrate. Biochemistry 44, 12168–12178.10.1021/bi0507985Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Klappa, P., Hawkins, H.C., and Freedman, R.B. (1997). Interactions between protein disulphide isomerase and peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 248, 37–42.10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00037.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Klintrot, I.M., Hoog, J.O., Jornvall, H., Holmgren, A., and Luthman, M. (1984). The primary structure of calf thymus glutaredoxin. Homology with the corresponding Escherichia coli protein but elongation at both ends and with an additional half-cystine/cysteine pair. Eur. J. Biochem. 144, 417–423.10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08481.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Kolsek, K., Aponte-Santamaria, C., and Grater, F. (2017). Accessibility explains preferred thiol-disulfide isomerization in a protein domain. Sci. Rep. 7, 9858.10.1038/s41598-017-07501-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kortemme, T., and Creighton, T.E. (1995). Ionization of cysteine residues at the termini of model a-helical peptides – relevance to unusual thiol Pk(a) values in proteins of the thioredoxin family. J. Mol. Biol. 253, 799–812.10.1006/jmbi.1995.0592Suche in Google Scholar

Krause, G., Lundstrom, J., Barea, J.L., Delacuesta, C.P., and Holmgren, A. (1991). Mimicking the active-site of protein disulfide-isomerase by substitution of proline34 in Escherichia coli thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9494–9500.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)92848-6Suche in Google Scholar

Lafaye, C., Van Molle, I., Dufe, V.T., Wahni, K., Boudier, A., Leroy, P., Collet, J.F., and Messens, J. (2016). Sulfur denitrosylation by an engineered Trx-like DsbG enzyme identifies nucleophilic cysteine hydrogen bonds as key functional determinant. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 15020–15028.10.1074/jbc.M116.729426Suche in Google Scholar

Lai, T.-Y., Yang, C.-Y., Lin, H.-J., Yang, C.-Y., and Hu, W.-P. (2011). Benchmark of density functional theory methods on the prediction of bond energies and bond distances of noble-gas containing molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 244110.10.1063/1.3603455Suche in Google Scholar

Langsetmo, K., Fuchs, J.A., Woodward, C., and Sharp, K.A. (1991). Linkage of thioredoxin stability to titration of ionazable groups with perturbed pKa. Biochemistry 30, 7609–7614.10.1021/bi00244a033Suche in Google Scholar

Lappi, A.K. and Ruddock, L.W. (2011). Reexamination of the role of interplay between glutathione and protein disulfide isomerase. J. Mol. Biol. 409, 238–249.10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.024Suche in Google Scholar

Lappi, A.K., Lensink, M.F., Alanen, H.I., Salo, K.E.H., Lobell, M., Juffer, A.H., and Ruddock, L.W. (2004). A conserved arginine plays a role in the catalytic cycle of the protein disulphide isomerases. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 283–295.10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.051Suche in Google Scholar

Laurent, T.C., Moore, E.C., and Reichard, P. (1964). Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. 4. Isolation and characterization of thioredoxin hydrogen donor from E. coli B. J. Biol. Chem. 239, 3436–3444.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)97742-2Suche in Google Scholar

Lewin, A., Crow, A., Hodson, C.T.C., Hederstedt, L., and Le Brun, N.E. (2008). Effects of substitutions in the CXXC active-site motif of the extracytoplasmic thioredoxin ResA. Biochem. J. 414, 81–91.10.1042/BJ20080356Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lillig, C.H. and Berndt, C. (2013). Glutaredoxins in thiol/disulfide exchange. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1654–1665.10.1089/ars.2012.5007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lillig, C.H., Prior, A., Schwenn, J.D., Aslund, F., Ritz, D., Vlamis-Gardikas, A., and Holmgren, A. (1999). New thioredoxins and glutaredoxins as electron donors of 3′-phosphoadenylylsulfate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7695–7698.10.1074/jbc.274.12.7695Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lillig, C.H., Berndt, C., and Holmgren, A. (2008). Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 1304–1317.10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.06.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Menchise, V., Corbier, C., Didierjean, C., Saviano, M., Benedetti, E., Jacquot, J.P., and Aubry, A. (2001). Crystal structure of the wild-type and D30A mutant thioredoxin h of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and implications for the catalytic mechanism. Biochem. J. 359, 65–75.10.1042/bj3590065Suche in Google Scholar

Miranda-Vizuete, A., Damdimopoulos, A.E., Gustafsson, J.A., and Spyrou, G. (1997). Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel Escherichia coli thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30841–30847.10.1074/jbc.272.49.30841Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Mossner, E., Huber-Wunderlich, M., and Glockshuber, R. (1998). Characterization of Escherichia coli thioredoxin variants mimicking the active-sites of other thiol/disulfide oxidoreductases. Protein Sci. 7, 1233–1244.10.1002/pro.5560070519Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Moutevelis, E. and Warwicker, J. (2004). Prediction of pK(a) and redox properties in the thioredoxin superfamily. Protein Sci. 13, 2744–2752.10.1110/ps.04804504Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nagy, P. (2013). Kinetics and mechanisms of thiol-disulfide exchange covering direct substitution and thiol oxidation-mediated pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 1623–1641.10.1089/ars.2012.4973Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Netto, L.E.S., de Oliveira, M.A., Monteiro, G., Demasi, A.P.D., Cussiol, J.R.R., Discola, K.F., Demasi, M., Silva, G.M., Alves, S.V., Faria, V.G., et al. (2007). Reactive cysteine in proteins: protein folding, antioxidant. defense, redox signaling and more. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 146, 180–193.10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.07.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Netto, L.E.S., de Oliveira, M.A., Tairum, C.A., and Neto, J.F.D. (2016). Conferring specificity in redox pathways by enzymatic thiol/disulfide exchange reactions. Free Radic. Res. 50, 206–245.10.3109/10715762.2015.1120864Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Neves, R.P.P., Fernandes, P.A., Varandas, A.J.C., and Ramos, M.J. (2014). Benchmarking of Density Functionals for the accurate description of thiol-disulfide exchange. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 10, 4842–4856.10.1021/ct500840fSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

Neves, R.P.P., Fernandes, P.A., and Ramos, M.J. (2017). Mechanistic insights on the reduction of glutathione disulfide by protein disulfide isomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E4724–E4733.10.1073/pnas.1618985114Suche in Google Scholar

Nielsen, J.E., Borchert, T.V., and Vriend, G. (2001). The determinants of a-amylase pH-activity profiles. Protein Eng. 14, 505–512.10.1093/protein/14.7.505Suche in Google Scholar

Pirneskoski, A., Klappa, P., Lobell, M., Williamson, R.A., Byrne, L., Alanen, H.I., Salo, K.E.H., Kivirikko, K.I., Freedman, R.B., and Ruddock, L.W. (2004). Molecular characterization of the principal substrate binding site of the ubiquitous folding catalyst protein disulfide isomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10374–10381.10.1074/jbc.M312193200Suche in Google Scholar

Putzu, M., Grater, F., Elstner, M., and Kubar, T. (2018). On the mechanism of spontaneous thiol-disulfide exchange in proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 16222–16230.10.1039/C8CP01325JSuche in Google Scholar

Rabenstein, D.L. and Millis, K.K. (1995). Nuclear magnetic resonance study of the thioltransferase-catalyzed glutathione/glutathione disulfide interchange reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1249, 29–36.10.1016/0167-4838(95)00067-5Suche in Google Scholar

Rietsch, A. and Beckwith, J. (1998). The genetics of disulfide bond metabolism. Annu. Rev. Gen. 32, 163–184.10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.163Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Rodriguez-Manzaneque, M.T., Tamarit, J., Belli, G., Ros, J., and Herrero, E. (2002). Grx5 is a mitochondrial glutaredoxin required for the activity of iron/sulfur enzymes. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1109–1121.10.1091/mbc.01-10-0517Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Roos, G., Loverix, S., and Geerlings, P. (2006). Origin of the pKa perturbation of N-terminal cysteine in alpha- and 3(10)-helices: a computational DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 557–562.10.1021/jp0549780Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Roos, G., Garcia-Pino, A., Van belle, K., Brosens, E., Wahni, K., Vandenbussche, G., Wyns, L., Loris, R., and Messens, J. (2007). The conserved active site proline determines the reducing power of Staphylococcus aureus thioredoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 368, 800–811.10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.045Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Roos, G., Foloppe, N., Van Laer, K., Wyns, L., Nilsson, L., Geerlings, P., and Messens, J. (2009). How Thioredoxin Dissociates Its Mixed Disulfide. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000461.10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000461Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Roos, G., Foloppe, N., and Messens, J. (2013). Understanding the pKa of redox cysteines: the key role of hydrogen bonding. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 94–127.10.1089/ars.2012.4521Suche in Google Scholar

Schultz, L.W., Chivers, P.T., and Raines, R.T. (1999). The CXXC motif: crystal structure of an active-site variant of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Acta Cryst. D Biol. Cryst. 55, 1533–1538.10.1107/S0907444999008756Suche in Google Scholar

Sevier, C.S. and Kaiser, C.A. (2002). Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 836–847.10.1038/nrm954Suche in Google Scholar

Siedler, F., Rudolphbohner, S., Doi, M., Musiol, H.J., and Moroder, L. (1993). Redox potential of active-site bis(cysteinyl) fragments of thiol-protein oxidoreductases. Biochemistry 32, 7488–7495.10.1021/bi00080a021Suche in Google Scholar

Siedler, F., Quarzago, D., Rudolphbohner, S., and Moroder, L. (1994). Redox-active bis-cysteinyl peptides. 2. Comparative study on the sequence dependent tendency for disulfide loop formation. Biopolymers 34, 1563–1572.10.1002/bip.360341114Suche in Google Scholar

Sun, C., Berardi, M.J., and Bushweller, J.H. (1998). The NMR solution structure of human glutaredoxin in the fully reduced form. J. Mol. Biol. 280, 687–701.10.1006/jmbi.1998.1913Suche in Google Scholar

Tagaya, Y., Maeda, Y., Mitsui, A., Kondo, N., Matsui, H., Hamuro, J., Brown, N., Arai, K., Yokota, T., Wakasugi, H., et al. (1989). ATL-derived factor (ADF), an IL-2 receptor TAC inducer homologous to thioredoxin – possible involvement of dithiol-reduction in the IL-2 receptor induction. EMBO J. 8, 757–764.10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03436.xSuche in Google Scholar

Takashima, Y., Hirota, K., Nakamura, H., Nakamura, T., Akiyama, K., Cheng, F.S., Maeda, M., and Yodoi, J. (1999). Differential expression of glutaredoxin and thioredoxin during monocytic differentiation. Immunol. Lett. 68, 397–401.10.1016/S0165-2478(99)00087-5Suche in Google Scholar

Tu, B.P. and Weissman, J.S. (2004). Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J. Cell Biol. 164, 341–346.10.1083/jcb.200311055Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ukuwela, A.A., Bush, A.I., Wedd, A.G., and Xiao, Z.G. (2018). Glutaredoxins employ parallel monothiol-dithiol mechanisms to catalyze thiol-disulfide exchanges with protein disulfides. Chem. Sci. 9, 1173–1183.10.1039/C7SC04416JSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Walker, K.W., Lyles, M.M., and Gilbert, H.F. (1996). Catalysis of oxidative protein folding by mutants of protein disulfide isomerase with a single active-site cysteine. Biochemistry 35, 1972–1980.10.1021/bi952157nSuche in Google Scholar

Wang, C., Li, W., Ren, J.Q., Fang, J.Q., Ke, H.M., Gong, W.M., Feng, W., and Wang, C.C. (2013). Structural insights into the redox-regulated dynamic conformations of human protein disulfide isomerase. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 44–53.10.1089/ars.2012.4630Suche in Google Scholar

Wedemeyer, W.J., Welker, E., Narayan, M., and Scheraga, H.A. (2000). Disulfide bonds and protein folding. Biochemistry 39, 4207–4216.10.1021/bi992922oSuche in Google Scholar

Wells, W.W., Xu, D.P., Yang, Y.F., and Rocque, P.A. (1990). Mammalian thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) and protein disulfide isomerase have dehydroascorbate reductase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 15361–15364.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55401-6Suche in Google Scholar

Wiita, A.P., Ainavarapu, R.K., Huang, H.H., and Fernandez, J.M. (2006). Force-dependent chemical kinetics of disulfide bond reduction observed with single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 7222–7227.10.1073/pnas.0511035103Suche in Google Scholar

Xia, T.H., Bushweller, J.H., Sodano, P., Billeter, M., Bjornberg, O., Holmgren, A., and Wuthrich, K. (1992). NMR structure of oxidized Escherichia coli glutaredoxin – comparison with reduced Escherichia coli glutaredoxin and functionally related proteins. Protein Sci. 1, 310–321.10.1002/pro.5560010302Suche in Google Scholar

Xing, S., Lauri, A., and Zachgo, S. (2006). Redox regulation and flower development: a novel function for glutaredoxins. Plant Biol. (Stuttg) 8, 547–555.10.1055/s-2006-924278Suche in Google Scholar

Xu, S.L., Sankar, S., and Neamati, N. (2014). Protein disulfide isomerase: a promising target for cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today 19, 222–240.10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.017Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Y.F. and Wells, W.W. (1991). Catalytic mechanism of thioltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 12766–12771.10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98965-9Suche in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Complexity of type IV collagens: from network assembly to function

- Structural and mechanistic aspects of S-S bonds in the thioredoxin-like family of proteins

- Oxidative stress and antioxidants in the pathophysiology of malignant melanoma

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Genes and Nucleic Acids

- Dynamic characteristics of the mitochondrial genome in SCNT pigs

- Protein Structure and Function

- Conversion of chenodeoxycholic acid to cholic acid by human CYP8B1

- Molecular Medicine

- The comparative biochemistry of viruses and humans: an evolutionary path towards autoimmunity

- MiR-23a-3p-regulated abnormal acetylation of FOXP3 induces regulatory T cell function defect in Graves’ disease

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- Evidence for a protective role of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- LncRNA TINCR/microRNA-107/CD36 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer via PPAR signaling pathway based on bioinformatics analysis

- Regulatory effect of hsa-miR-5590-3P on TGFβ signaling through targeting of TGFβ-R1, TGFβ-R2, SMAD3 and SMAD4 transcripts

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Complexity of type IV collagens: from network assembly to function

- Structural and mechanistic aspects of S-S bonds in the thioredoxin-like family of proteins

- Oxidative stress and antioxidants in the pathophysiology of malignant melanoma

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Genes and Nucleic Acids

- Dynamic characteristics of the mitochondrial genome in SCNT pigs

- Protein Structure and Function

- Conversion of chenodeoxycholic acid to cholic acid by human CYP8B1

- Molecular Medicine

- The comparative biochemistry of viruses and humans: an evolutionary path towards autoimmunity

- MiR-23a-3p-regulated abnormal acetylation of FOXP3 induces regulatory T cell function defect in Graves’ disease

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- Evidence for a protective role of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- LncRNA TINCR/microRNA-107/CD36 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer via PPAR signaling pathway based on bioinformatics analysis

- Regulatory effect of hsa-miR-5590-3P on TGFβ signaling through targeting of TGFβ-R1, TGFβ-R2, SMAD3 and SMAD4 transcripts