Abstract

2-(2,4,6-Trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethyammonium halides 3–5 were prepared starting from 2-(methylthio)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazin-4(6H)-thione (1). First, compound 1 was S4-methylated to give 2,4-bis(methylthio)-6,7-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]-triazine (2) which, in turn, was hydrolyzed with corresponding aqueous solution of hydrogen halide. X-ray crystallographic study revealed that in crystals of 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium iodide (5) a chain of alternatively arranged anions and cations extending along [001] is formed through polymeric (anion-π)n interactions.

Introduction

Cyanuric acid, that in gas phase, solution and solid phase exists as isocyanuric acid [1], [2] has long been considered as an important derivative of s-triazine, weakly aromatic [3], biodegradable and non toxic to human and aquatic animals [4]. Besides its widespread use in outdoor swimming pools [5] and large water systems [6] to protect chlorine breakdown from sunlight, cuanuric acid derivatives of ascorbic acid have been investigated as potential anticancer agents [7]. Moreover, cyanuric acid-based siderophore analogs able to bind ferric ion stoichiometrically (artificial iron chelators) [8] and β-lactam (lorabid) conjugates [9] were synthesized to provide new classes of antimicrobial agents and siderophore-mediated drug delivery systems.

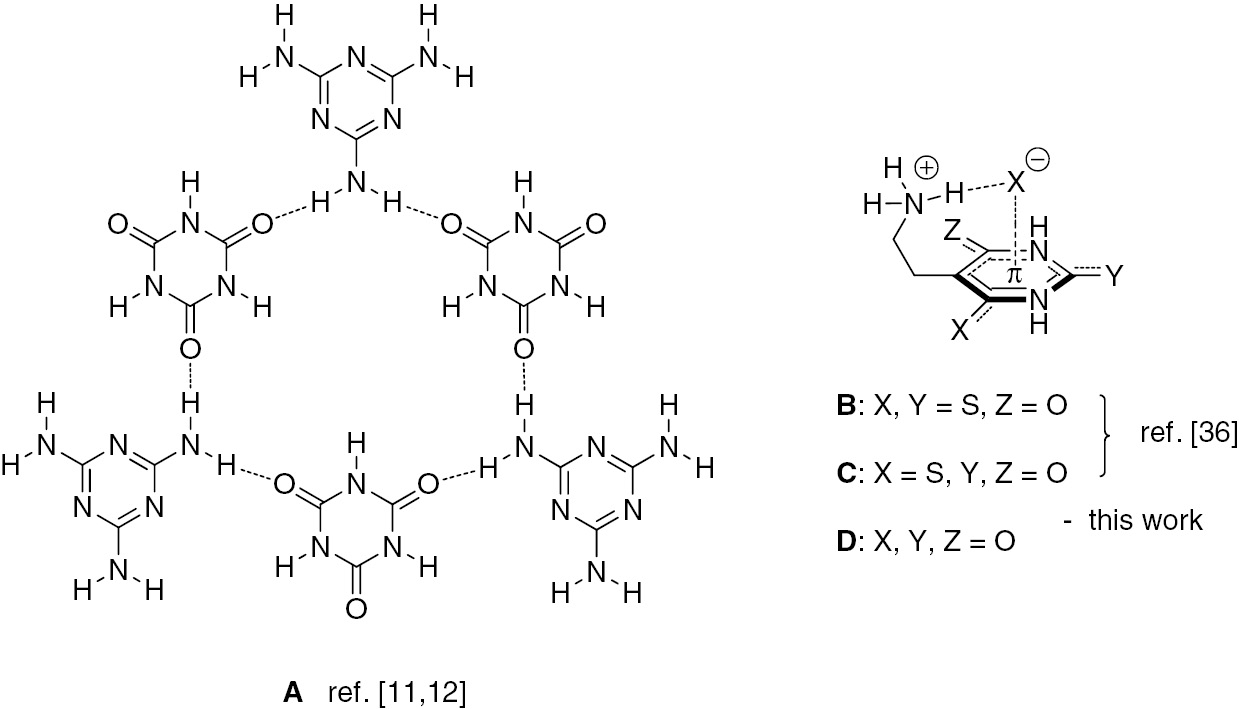

Perhaps the most representative are the applications of cyanuric acid and its derivatives in the area of supramolecular chemistry [10]. Thus, Whitesides and co-workers designed and performed noncovalent syntheses of supramolecular aggregates of cyanuric acid and melamine derivatives (Figure 1, structure A) [11], [12]. Such cooperative assembly structures prepared using intermolecular hydrogen bonding have subsequently found various practical uses, such as visual detection of melamine in raw milk and infant formula [13], preparation of precursors for imprinted and hybrid silica materials with molecular recognition properties [14], preparation of promising precursor materials of graphitic carbon nitride (g-CN) enabling optimization of the texture and photoelectric properties [15] and hydrothermal synthesis of organic channel structures [16]. Moreover, it was found that cyanuric acid reprograms the self-assembly of poly(adenine) DNA, RNA and peptide nucleic acid (PNA) to form novel nucleic acid structures [17].

(A) 1:1 complex between cyanuric acid and melamine; (B–D) cooperative anion-π and N-H···anion binding interactions between (thio)cyanuric acid derivatives and halide anions.

In recent years, however, cyanuric acid derivatives have drawn attention of researchers interested in noncovalent anion-aromatic bonding, the poorly explored counterpart of cation-π interactions [18]. The term “anion-π interactions” has been coined by Frontera and coworkers to describe energetically favorable interactions between anions and electron-deficient (π-acidic) rings, such as hexafluorobenzene, trinitrobenzene and s-triazine, with a permanent positive quadrupole moment [19]. Subsequently, anion-π interactions have been exploited in fields such as supramolecular assembly, anion sensing and transport through membranes in biological systems [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. However, despite the fact that research on synthetic anion transport systems has already grown into mature field [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], the examples of synthetic anionophores that work with anion-π interactions are rather scarce. Among the most prominent functional systems are naphthalenedimide rods designed to combine active, photoinduced transport of electrons in one direction with passive anion antiport along anion-π slides [35].

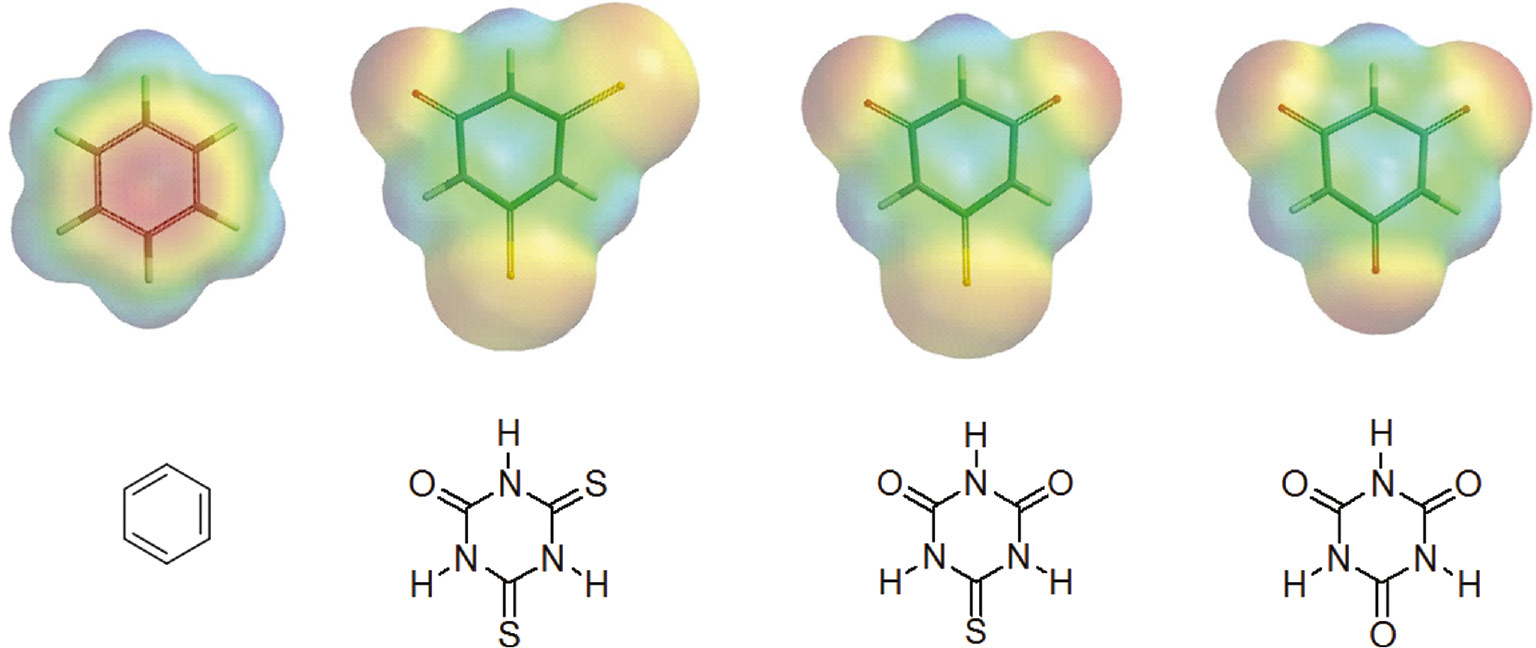

Our previous contribution to this field has been the synthesis of π-acidic dithio- and thiocyanuric acid derivatives (Figure 1, structures B and C, respectively) which exhibit cooperative anion-π and N-H···anion binding interactions [36]. As can be inferred from Figure 2, presenting calculated electron-density surfaces, (thio)cyanuric acids have positive quadrupole moments perpendicular to the aromatic plane, and therefore are able to attract electron-donor species. In the present communication we wish to describe a facile synthesis of the previously unknown cyanuric acid derivatives of type D (Figure 1) and unusual polymeric (anion-π)n interactions in crystals of 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium iodide (X=I).

Calculated electron-density surfaces of benzene and (thio)cyanuric acids, scaling areas of highest electron density (red) to lowest (blue).

Results and discussion

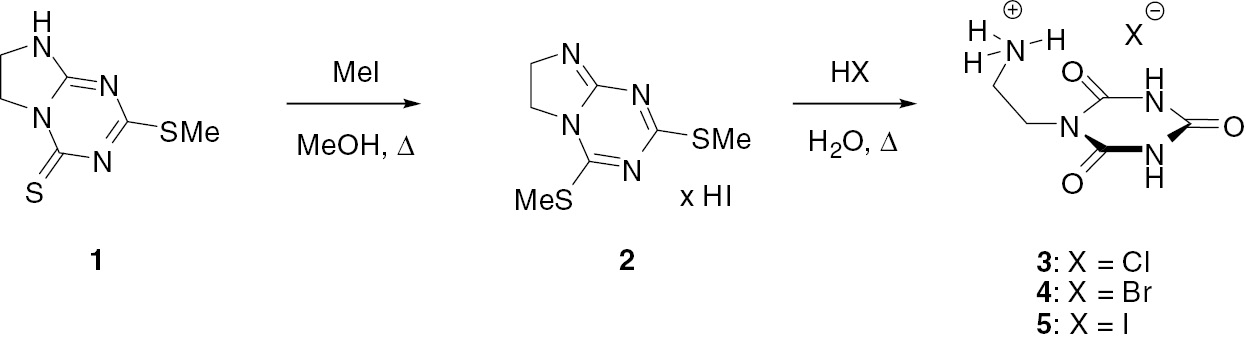

The synthetic path to 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium halides 3 (X=Cl), 4 (X=Br) and 5 (X=I) is presented in Scheme 1. First, the previously described 2-(methylthio)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazin-4(6H)-thione (1) [37] was subjected to the reaction with methyl iodide in boiling methanol for 1 h. Then, the resulting 2,4-bis(methylthio)-6,7-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5]-triazine (2) was hydrolyzed by heating in aqueous solution of an appropriate hydrogen halide to give the desired product 3–5 in good yield. Structures of the newly prepared compounds 2–5 were confirmed by CHN elemental analysis as well as IR and NMR spectroscopic data (see Experimental).

Preparation of compounds 2–5.

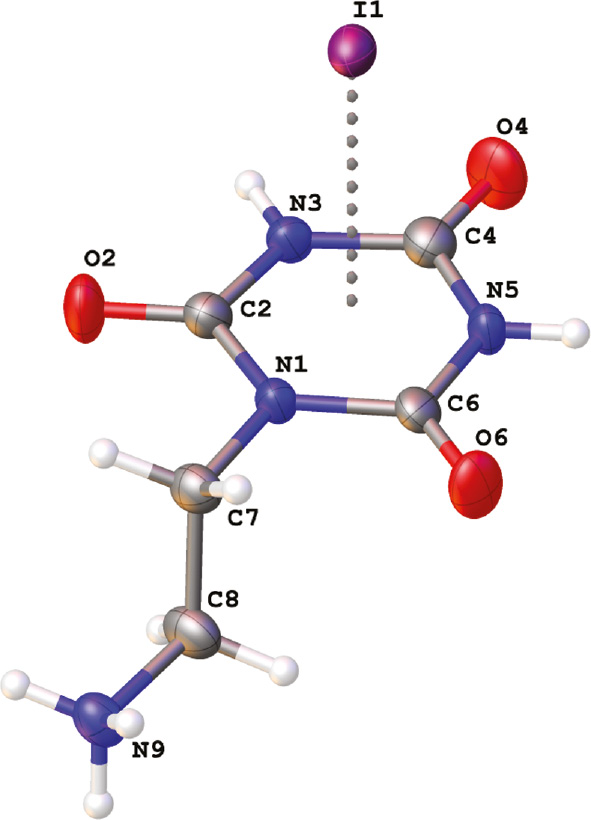

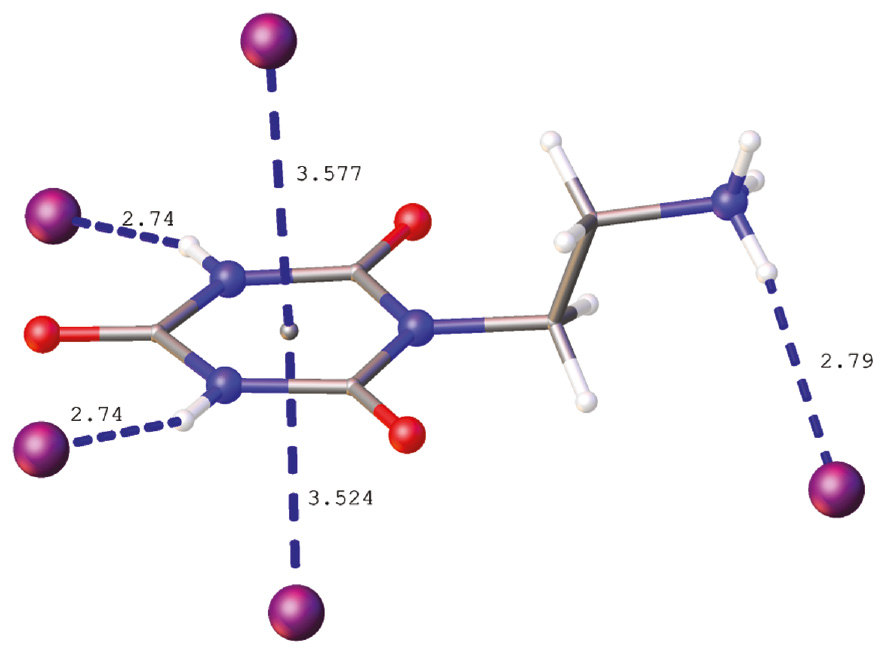

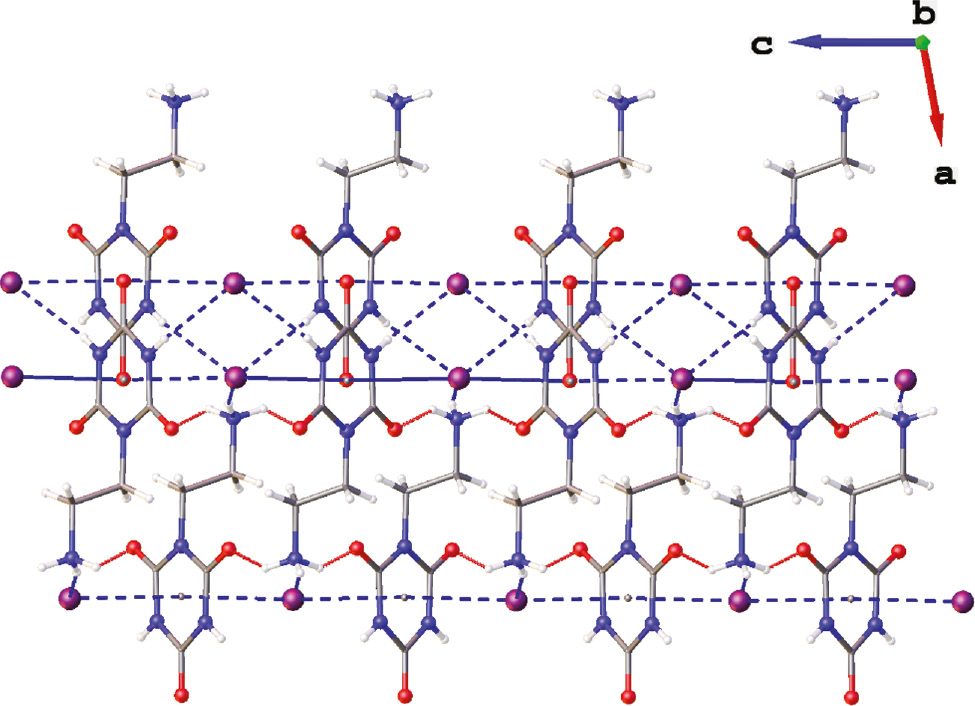

Crystallization of the iodide salt 5 from 1% aqueous HI solution provided crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. The asymmetric part of the unit cell together with the labeling scheme is presented in Figure 3. The organic cation in 5 differs in conformation with the analogous cations found in the structures of related thioxo derivatives, 2-(2-oxo-4,6-dithioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium halides of type B and 2-(2,4-dioxo-6-thioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium halides of type C [36]. In the latter ones, the conformation around N1-C7 and C7-C8 single bonds enables hydrogen bonding between the ammonium group and the halide ion placed nearly directly above the center of the electron-deficient π-system of the triazine ring. In the thioxo derivatives the halide anion exhibits anion-π interactions with one side of the triazine ring only. In turn, the 2-ethylammonium group in 5 adopts an extended conformation what prevents hydrogen bonding between the ammonium group and the anions interacting with the triazine π system of the same organic cation. Instead, the iodide anion is placed directly above the center (Cg) of the aromatic ring on both its sides with the I−···Cg distances of 3.524 and 3.577 Å and I−···Cg···I− angle of 177.4° (Figure 4). Because the cyanuric acid fragment of the cation is interacting with two iodide anions and each iodide anion is interacting with two triazine rings, a polymeric chain of alternatively arranged anions and cations extending along [001] is formed through anion-π interactions (Figure 5). These are not the only specific interactions of the cation with the anion as I1 is additionally involved in three hydrogen-bonding interactions: two N-H···I− interactions with the cyanuric acid fragment and one with the ammonium group of a symmetry related molecule (Figure 4). The former hydrogen bonds connect the chains into the (100) layers whereas hydrogen bonds involving the ammonium group connect the neighboring (100) layers into a three dimensional framework as illustrated in Figure 6.

Asymmetric part of the unit cell in 5with the atom labeling scheme.

Iodide anions interacting with the cation. Distances are given in Å.

![Figure 5 A polymeric chain formed via anion-π interactions along [001].](/document/doi/10.1515/hc-2016-0122/asset/graphic/j_hc-2016-0122_fig_005.jpg)

A polymeric chain formed via anion-π interactions along [001].

N-H···I− hydrogen bonds and anion-π interactions in 5 organizing cations and anions into a three dimensional framework – a view along the y axis.

Conclusion

We have obtained cyanuric acid derivatives 3–5 which may serve as substrates for the development of synthetic anion-π binding modules and halide transporters that can be used as models for biological anionophores or in the treatment of certain channelopathies.

Experimental

Melting points were determined using a Boetius apparatus and are uncorrected. Elemental analyses were carried out on a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN analyzer. IR spectra were recorded in KBr pellets on a Nicolet FT-IR spectrophotometer. 1H-NMR (500 MHz) and 13C-NMR (125 MHz) were recorded using a Varian Unity 500 spectrometer in DMSO-d6 with SiMe4 as an internal standard. Electron-density surfaces were calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory with use of Spartan’08 program, Wavefunction Inc. 2-(Methylthio)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazine-4(6H)-thione (1) was obtained according to the procedure described previously in Ref. [37].

2,4-Bis(methylthio)-6,7-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazine hydrogen iodide (2)

A solution of 2-(methylthio)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazine-4(6H)-thione (1, 0.5 g, 2.5 mmol) and methyl iodide (0.3 mL, 5.0 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (25 mL) was heated under reflux for 1 h. Then, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and the product 2 that precipitated was filtered off under suction, washed with cold water and dried: yield 0.45 g (51%); mp 179–180oC; IR: 3088, 3010, 1652, 1523, 1481, 1254, 1232, 1128 cm−1; 1H-NMR: δ 2.57 (s, 3H, SCH3), 2.7 (s, 3H, SCH3), 3.62 (t, 2H, CH2), 4.25 (t, 2H, CH2), 8.9 (br s, 1H, NH+). Anal. Calcd for C7H11N4S2I (MW=342.21): C, 24.56; H, 3.24; N, 16.37. Found: C, 24.18; H, 3.02; N, 16.68.

Synthesis of 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium halides (3–5)

A solution of compound 2 (0.87 g, 2.5 mmol) in 12% aqueous solution of HCl, HBr or HI was heated at reflux for 2.5 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure to a volume of 10 mL. Upon cooling to 5oC the pure product 3–5 that precipitated was separated by suction, washed with cold water and dried.

2-(2,4,6-Trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium chloride (3)

Yield 0.28 g (52%); mp 289–290oC (dec); IR: 3189, 3038, 2800, 1768, 1721, 1687, 1474, 1405, 1066 cm−1; 1H-NMR: δ 2.95 (sextet, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (t, 2H, CH2), 8.15 (s, 2H, NH), 11.50 (s, 3H, NH3+); 13C-NMR: δ 37.1, 38.2, 148.7, 150.1. Anal. Calcd for C5H9N4O3Cl (208.60): C, 28.78; H, 4.35; N, 26.86. Found: C, 28.64; H, 4.31; N, 27.09.

2-(2,4,6-Trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium bromide (4)

Yield 0.345 g (93%); mp 312–320oC (dec.); IR: 3187, 3048, 2789, 1765, 1720, 1682 cm−1; 1H-NMR: δ 2.98 (br s, 2H, CH2), 3.85 (t, 2H, CH2), 7.95 (s, 2H, NH), 11.56 (s, 3H, NH3+); 13C-NMR: δ 37.7, 38.5, 148.8, 150.2. Anal. Calcd for C5H9N4O3Br (253.06): C, 23.72; H, 3.58; N, 22.14. Found: C, 23.89; H, 3.82; N, 22.41.

2-(2,4,6-Trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium iodide (5)

The crude product was crystallized from 1% aqueous solution of HI to give 0.225 g of 5 (51% yield); mp 306–316oC (dec); IR: 3185, 2776, 1762, 1746, 1686, 1588, 1471, 14389, 1062 cm−1; 1H-NMR: δ 2.99 (br s, 2H, CH2), 3.88 (t, 2H, CH2), 7.69 (s, 2H, NH), 11.54 (s, 3H, NH3+); 13C-NMR: δ 37.9, 38.7, 149.23, 150.7. Anal. Calcd for C5H9N4O3I (303.05): C, 19.81; H, 2.99; N, 18.49. Found: C, 20.03; H, 3.15; N, 18.55.

X-ray crystallographic study

Diffraction data for 5 were collected with an Oxford Diffraction XcaliburE diffractometer at 293(2) K and processed using CrysAlisPro software [38]. The structure was determined from a twinned specimen because all checked crystals exhibited non-merohedral twinning. The structure was solved with SHELXT [39] and refined with SHELXL-2014 [39] implemented into Olex-2 [40]. All H atoms were placed geometrically and refined as riding on their carriers with Uiso(H)=xUeq(C,N), where x=1.5 for the NH3 group H atoms and x=1.2 the remaining H atoms.

Crystal data for 5: C5H9IN4O3 (M=299.10 g/mol): monoclinic, space group P21/c (no. 14), a=8.5770(6)Å, b=9.5588(5)Å, c=11.9097(7)Å, β=100.703(7)°, V=959.44(10)Å3, Z=4, T=293K, μ(MoKα)=3.300 mm−1, Dcalc=2.071g/cm3, 19543 reflections measured (6.45°≤2Θ≤51.36°), 3194unique (Rint=0.0466, Rsigma=0.0259) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0319 (I>2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0881 (all data). CCDC deposit number: CCDC1483456.

References

[1] Liang, X.; Pu, X.; Zhou, H.; Wong, N.-B.; Tian, A. Keto-enol tautomerization of cyanuric acid in the gas phase and in water and methanol. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem.2007, 816, 125–136.10.1016/j.theochem.2007.04.010Search in Google Scholar

[2] Weinbenga, E. H. Crystal structure of cyanuric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 6156–6157.10.1021/ja01143a548Search in Google Scholar

[3] Perez-Manriquez, L.; Cabrera, A.; Sansores, L. E.; Salcedo, R. Aromaticity in cyanuric acid. J. Mol. Model. 2011, 17, 1311–1315.10.1007/s00894-010-0825-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Seifer, G. B. Cyanuric acid and cyanurates. Russ. J. Coord. Chem.2002, 28, 301–324.10.1023/A:1015531315785Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yilmaz, T.; Yazar, Z. Determination of cyanuric acid in swimming pool water and milk by differential pulse polarography. Clean – Soil Air Water2010, 38, 816–821.10.1002/clen.201000071Search in Google Scholar

[6] Canelli, E. Chemical, bacteriological and toxicological properties of cyanuric acid and chlorinated isocyanurates as applied to swimming pool disinfection. Am. J. Pub. Health1974, 64, 92–103.10.2105/AJPH.64.2.155Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Wittine, K.; Stipkovic Babic, M.; Kosutic, M.; Cetina, M.; Rissanen, K.; Kraljevic Pavelic, S.; Tomljenovic Pavic, A.; Sedic, M.; Pavelic, K.; Mintas, M. The new 5- or 6-azapyrimidine and cyanuric acid derivatives of L-ascorbic acid bearing the free C-5 hydroxy or C-4 amino group at the ethylenic spacer: CD-spectral absolute configuration determination and biological activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2770–2785.10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Lee, B. H.; Miller, M. J.; Prody, C. A.; Neilands, J. B. Artificial siderophores 2. Synthesis of trihydroxamate analogues of rhodotorulic acid and their biological iron transport capabilities in Escherichia coli. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 323–327.10.1021/jm00381a011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Ghosh, M.; Miller, M. J. Iron transport-mediated drug delivery: synthesis and biological evaluation of cyanuric acid-based siderophore analogs and β-lactam conjugates. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 1020–1026.10.1021/jo00084a018Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yang, S. K.; Zimmerman, S. C. Hydrogen bonding modules for use in supramolecular polymers. Isr. J. Chem. 2013, 53, 511–520.10.1002/ijch.201300045Search in Google Scholar

[11] Seto, C. T.; Whitesides, G. M. Molecular self-assembly through hydrogen bonding: supramolecular aggregates based on the cyanuric acid-melamine lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 905–916.10.1021/ja00056a014Search in Google Scholar

[12] Zerkowski, J. A.; MacDonald, J. C.; Seto, C. T.; Wierda, D. A.; Whitesides, G. M. Design of organic structures in the solid state: molecular tapes based on the network of hydrogen bonds present in the cyanuric acid-melamine complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 2382–2391.10.1021/ja00085a018Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ai, K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L. Hydrogen-bonding recognition-induced color change of gold nanoparticles for visual detection of melamine in raw milk and infant formula. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9464–9497.10.1021/ja9037017Search in Google Scholar

[14] Arrachart, G.; Carcel, C.; Trens, P.; Moreau, J. J.; Wong Chi Man, M. Silylated melamine and cyanuric acid as precursors for imprinted and hybrid silica materials with molecular recognition properties. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6279–6288.10.1002/chem.200900278Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jun, Y.-S.; Lee, E. Z.; Wang, X.; Hong, W. H.; Stucky, G. D.; Thomas, A. From melamine-cyanuric acid supramolecular aggregates to carbon nitride hollow spheres. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3661–3667.10.1002/adfm.201203732Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ranganathan, A.; Pedireddi, V. R.; Rao, C. N. R. Hydrothermal synthesis of organic channel structures: 1:1 hydrogen-bonded adducts of melamine with cyanuric and trithiocyanuric acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1752–1753.10.1021/ja983928oSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Avakyan, N.; Greschner, A. A.; Aldaye, F.; Serpell, C. J.; Toader, V.; Petitjean, A.; Sleiman, H. F. Reprogramming the assembly of unmodified DNA with a small molecule. Nat. Chem.2016, 8, 368–376.10.1038/nchem.2451Search in Google Scholar

[18] Davis, J. T. Supramolecular chemistry: anion transport as easy as pi. Nat. Chem.2010, 2, 516–517.10.1038/nchem.723Search in Google Scholar

[19] Quinonero, D.; Garau, D.; Rotger, C.; Frontera, A.; Ballester, A.; Costa, P.; Deya, P. M. Anion-pi interactions: do they exist? Angew. Chem. Int. Eng. Ed.2002, 41, 3389–3392.10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3389::AID-ANIE3389>3.0.CO;2-SSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Gamez, P.; Mooibroek, T. J.; Teat, S. I.; Reedijk, J. Anion binding involving π-acidic heteroaromatic rings. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 435–444.10.1021/ar7000099Search in Google Scholar

[21] Schottel, B. L.; Chifotides, H. T.; Dunbar, K. R. Anion-π interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 68–83.10.1039/B614208GSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Bretschneider, A.; Andrada, D. M.; Dechert, S.; Meyer, S.; Mata, R. A.; Meyer, F. Preorganized anion traps for exploiting anion-π interactions: an experimental and computational study. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 16988–17000.10.1002/chem.201302598Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Gale, P. A.; Busschaert, N.; Haynes, C. J. E.; Karagiannidis, L. E.; Kirby, I. L. Anion receptor chemistry: highlights from 2011 and 2012. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 205–241.10.1039/C3CS60316DSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Mohan, N.; Suresh, C. H. Anion receptors based on highly fluorinated aromatic scaffolds. J. Phys. Chem A2014, 118, 4315–4324.10.1021/jp5019422Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Giese, M.; Albrecht, M.; Rissanen, K. Anion-π interactions with fluoroarenes. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8867–8895.10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00156Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Giese, M.; Albrecht, M.; Rissanen, K. Experimental investigation of anion-π interactions – applications and biochemical relevance. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 1778–1795.10.1039/C5CC09072ESearch in Google Scholar

[27] Lucas, X.; Bauza, A.; Frontera, A.; Quinonero, D. A thorough anion-π interaction study in biomolecules: on the importance of cooperativity effects. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1038–1050.10.1039/C5SC01386KSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Vilar, R. Recognition of anions; Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg, 2008.10.1007/978-3-540-79092-1Search in Google Scholar

[29] Davis, J. T.; Okunola, O.; Quesada, R. Recent advances in the transmembrane transport of anions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3843–3862.10.1039/b926164hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Gale, P. A. From anion receptors to transporters. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 216–226.10.1021/ar100134pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Gokel, G. W.; Barkey, N. Transport of chloride ion through phospholipid bilayers mediated by synthetic ionophores. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 947–963.10.1039/b817245pSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Shen, B.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Yao, X.; Yang, D. A synthetic chloride channel restores chloride conductance in human cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. PLoS One2012, 7, e34694.10.1371/journal.pone.0034694Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Li, H.; Valkenier, H.; Judd, L. W.; Grotherhood, P. R.; Hussain, S.; Cooper, J. A.; Jurcek, O.; Sparkes, H. A.; Shepard, D. N.; Davis, A. P. Efficient, non-toxic anion transport by synthetic carriers in cells and epithelia. Nat. Chem.2016, 8, 24–32.10.1038/nchem.2384Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Gokel, G. W.; Schlesinger, P. H. Synthetic ion channels. US 7,129,208 B2, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Jentzsch, A. V.; Hennig, A.; Mareda, J.; Matile, S. Synthetic ion transporters that work with anion-π interactions, halogen bonds, and anion-macropole interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2791–2800.10.1021/ar400014rSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Frontera, A.; Saczewski, F.; Gdaniec, M.; Dziemidowicz-Borys, E.; Kurland, A.; Deýa, P. M.; Quiñonero, D.; Garau, C. Anion-π interactions in cyanuric acids: a combined crystallographic and computational studies. Chem. Eur. J. 2005, 11, 6560–6567.10.1002/chem.200500783Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Sączewski, F.; Gdaniec, M. Synthesis, reactions, and crystal structure of 2-(alkylthio)-7,8-dihydroimidazo[1,2-a]-1,3,5-triazine-4(6H)-thiones. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1987, 1987, 721–724.10.1002/jlac.198719870816Search in Google Scholar

[38] Agilent Technologies. CrysAlis Pro software, Agilent Technologies Ltd: Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT– Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8.10.1107/S2053273314026370Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L. J.; Gildea, R. J.; Howard, J. A. K.; Puschmann, H. A. Complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341.10.1107/S0021889808042726Search in Google Scholar

©2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preliminary Communications

- Efficient synthesis of 4-amino-2,6-dichloropyridine and its derivatives

- Reactions of 3-arylmethylene-3H-furan(pyrrol)-2-ones with azomethine ylide: synthesis of substituted azaspirononenes

- Research Articles

- Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of 2-(1-phenyl-3-(2-thienyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)chroman-4-one derivatives

- Structural characterization of copper complexes with chiral 1,2,4-triazine-oxazoline ligands

- Synthesis of metallophthalocyanines with four oxy-2,2-diphenylacetic acid substituents and their structural and electronic properties

- Polymeric (anion-π)n interactions in crystals of 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium iodide

- 5-(N-Ethylcarbazol-3-yl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (ECTC): a novel fluorescent sensor for ferric ion

- Novel 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroimidazo[2′,1′:2,3]thiazolo[5,4-c]pyridine derivatives

- Halogenoheterocyclization of 2-(allylthio)quinolin-3-carbaldehyde and 2-(propargylthio)quinolin-3-carbaldehyde

- Convenient synthesis of the functionalized 1′,3′-dihydrospiro[cyclopentane-1,2′-inden]-2-enes via a three-component reaction

- Synthesis of spiro[pyrazole-4,8′-pyrazolo [3,4-f]quinolin]-5(1H)-ones by the reaction of aldehydes with 1H-indazol-6-amine and 1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preliminary Communications

- Efficient synthesis of 4-amino-2,6-dichloropyridine and its derivatives

- Reactions of 3-arylmethylene-3H-furan(pyrrol)-2-ones with azomethine ylide: synthesis of substituted azaspirononenes

- Research Articles

- Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of 2-(1-phenyl-3-(2-thienyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)chroman-4-one derivatives

- Structural characterization of copper complexes with chiral 1,2,4-triazine-oxazoline ligands

- Synthesis of metallophthalocyanines with four oxy-2,2-diphenylacetic acid substituents and their structural and electronic properties

- Polymeric (anion-π)n interactions in crystals of 2-(2,4,6-trioxo-[1,3,5]triazinan-1-yl)ethylammonium iodide

- 5-(N-Ethylcarbazol-3-yl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (ECTC): a novel fluorescent sensor for ferric ion

- Novel 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroimidazo[2′,1′:2,3]thiazolo[5,4-c]pyridine derivatives

- Halogenoheterocyclization of 2-(allylthio)quinolin-3-carbaldehyde and 2-(propargylthio)quinolin-3-carbaldehyde

- Convenient synthesis of the functionalized 1′,3′-dihydrospiro[cyclopentane-1,2′-inden]-2-enes via a three-component reaction

- Synthesis of spiro[pyrazole-4,8′-pyrazolo [3,4-f]quinolin]-5(1H)-ones by the reaction of aldehydes with 1H-indazol-6-amine and 1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one