Abstract

Background

Medical microbiology represents a fundamental core curriculum for medical students. In order to adapt to the cultivation of high-level medical talents under the guidance of the concept of holistic education, the focus of this course is on the development of scientific thinking and professionalism. This paper took the example of Helicobacter pylori, an important pathogen in the digestive system, addressing the teaching design of this chapter in medical microbiology.

Teaching design

The design of this chapter includes learning objectives, teaching content, teaching model and assessment. The learning objectives were designed under the outcome-based education philosophy, integrating the three dimensions of attitude, skill and knowledge. The content of this chapter is designed to integrate a number of key concepts, including systematic thinking, critical thinking, the One Health perspective, and the mission and responsibility of infectious disease prevention and control. Question-oriented online-and-offline blended teaching model was adopted, and a multi-objective assessment system was applied.

Implementation

A series of questions were designed before, during, and after the class. These questions served as the primary focus of learning, guiding students through various teaching activities, including online self-study, offline discussion and analysis, and online extended learning. Concurrently, the evaluation is integrated throughout the teaching process, with particular emphasis on formative and process evaluations.

Conclusions

This teaching design facilitated the achievement of learning objectives and optimized the teaching effect. The students’ self-assessment of their overall improvement in knowledge, skills and attitude, as well as their high level of satisfaction with the classroom environment, is presented herewith. The teaching design of this chapter has a particular demonstrative effect.

Background

In the context of the frequent outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, there is a surge in the demand for clinical medical talents with knowledge of infectious diseases around the world. Medical microbiology is the foundation for a series of courses including infectious diseases and preventive medicine. The cultivation of medical students in the new medicine era needs to emphasize not only knowledge and skills, but also the scientific thinking and professional competency in medical microbiology teaching. These anticipated learning outcomes guide the design of the course, and this manuscript will use a representative chapter in medical microbiology – Helicobacter pylori as an example, to illustrate the operable teaching principles and strategies.

H. pylori is a significant pathogen that causes gastric infection and is classified within the genus Helicobacter and species pylori. In textbooks of medical microbiology, this chapter is often presented after Enterobacteriaceae, Vibrio and Campylobacter to distinguish it from other pathogenic bacteria of digestive system.

In this chapter, the classical teaching mode is still predominantly lecture-based, the teachers deliver basic knowledge in the classroom and students learn according to the teachers’ guidance. There is a paucity of teaching activities that encourage active participation. Additionally, the content is based solely on the textbook, with a lack of extended teaching material. The course does not align its learning outcomes with those of talent training. It is evident that such teaching mode is inadequate for the training of medical professionals in the context of the evolving medical landscape. It is therefore proposed that the teaching design presented in this paper be used as an applicable reference for teachers.

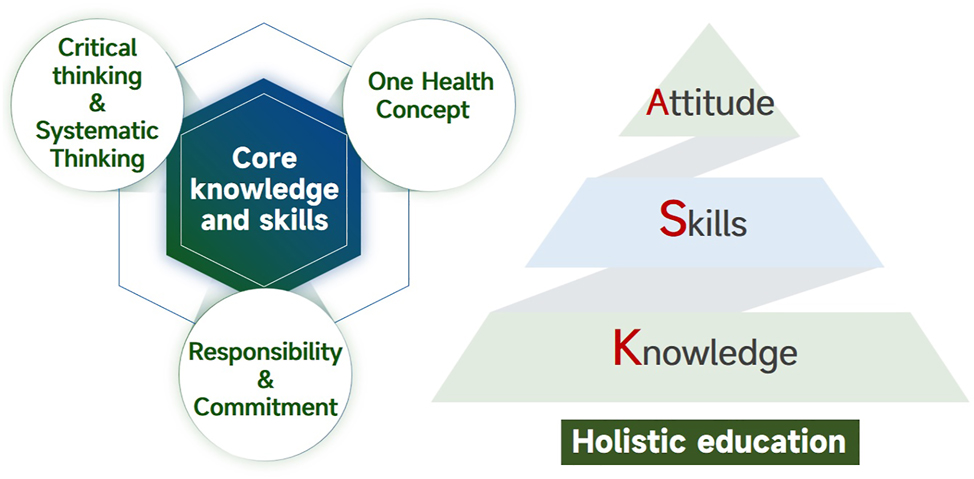

The principles of our teaching design should be aligned with the requirements of the learning objectives of the curriculum which is outcome based (Figure 1). In addition to the core knowledge and skills, the key points of the teaching design are to develop student systematic and critical thinking, as well as the concept of One Health, and to foster a sense of responsibility in the prevention and control of infectious diseases [1]. This requirement is also reflected in the design of the chapter on H. pylori.

Design principles for teaching medical microbiology. “ASK” educational philosophy is applied in the course design. In addition to the core knowledge and skills, critical and systematic thinking, the concept of One Health, and the responsibility and commitment of infectious disease prevention and control education are also integrated, reflecting the holistic education perspective.

The subject of this case study is eighth-year undergraduate students majoring in clinical medicine. The class size is 30 students, and the course is taught during the second semester of the second year of the undergraduate program. The course duration is 1 h.

Teaching design and implementation

Identification of learning objectives

The “ASK” educational philosophy is applied to the design of learning objectives, ASK stands for Attitude, Skill and Knowledge, and represents an educational philosophy that places a strong emphasis on the holistic development of the student, with a particular focus on the integrated development of knowledge, skills and attitudes (Figure 1).

Based on the “ASK” concept, the teaching design of H. pylori were considered in the development of the following principals for the learning objectives.

Development of systematic thinking

In order to foster the development of systematic thinking, it is recommended that educators commence with the pathogens associated with common infections of the digestive system. This approach will enable students to summarize and analyze the similarities and differences between the pathogens of the digestive system, as well as to clarify the characteristics of H. pylori.

Furthermore, the current standard for the treatment of H. pylori is a regimen of proton pump inhibitors, bismuth, and combined antibiotics. However, the long-term use of antibiotics raises concerns about the impact on the human microbiota, particularly the gut microbiota [2]. This is an important area for students to consider in terms of microecosystem balance.

Development of critical thinking

With regard to the development of students’ critical thinking, recent studies have indicated that H. pylori may have a protective effect against a number of diseases, including reflux oesophagitis and multiple sclerosis [3, 4]. Furthermore, children who have been infected with H. pylori in childhood appear to have a reduced incidence of immune-related diseases such as eczema and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) later in life 5], [6], [7. It is therefore beneficial for students to gain an understanding of pathogens from both positive and negative perspectives, to critically analyze the relationship between pathogens and human health, so as to stimulate the students’ interests in exploring the underlying mechanisms.

Reinforcing the meaning of Koch’s postulates

The discovery of H. pylori is a classic practice of Koch’s postulates in the discovery of pathogenic bacteria [8]. While Koch’s postulates and its application should be studied throughout medical microbiology course, students are expected to equip with the ability to use their knowledge of pre-existing pathogens to identify emerging pathogens in future infectious disease epidemics. Koch’s postulates represent a significant reference point in this context. The scientist’s spirit of truth-seeking and dedication to science, as exemplified by the discovery of H. pylori, helps to cultivate students’ responsibility and commitment in the prevention and control of infectious diseases.

Based on the above principals, following the backward design strategy, we propose the following learning objectives of H. pylori for the comprehensive medical students, viz. at the end of this chapter, the students can:

Review the history of H. pylori discovery.

Describe the morphology, staining, biochemical properties and culture characteristics of H. pylori.

List the diseases caused by H. pylori, along with the laboratory diagnostic methods and treatment of infection.

Identify similarities and differences between H. pylori and other gastrointestinal pathogens.

Have a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between H. pylori and human health.

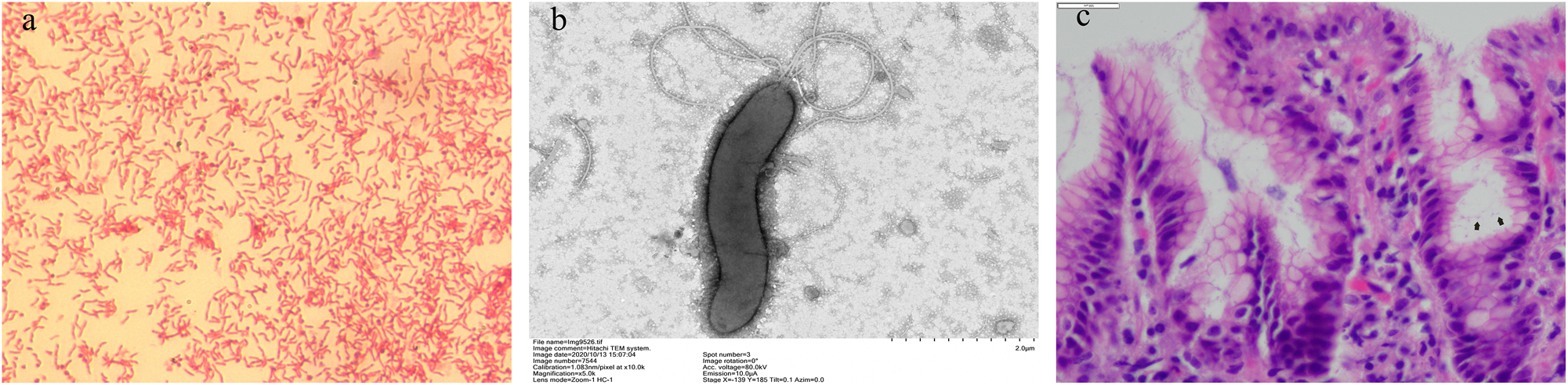

Morphology of Helicobacter pylori. (a) Gram staining of H. pylori (×1,000). H. pylori is Gram negative; (b) transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of H. pylori (×5,000). H. pylori is a curved, elongated bacterium with prominent flagella, facilitating its penetration of the thick mucous layer in the stomach; (c) Histologic manifestations of H. pylori infection (HE staining, ×400). H. pylori is visible as small red rods (arrows) on the epithelial surface and within the glands. The underlying mucosa shows inflammatory cells infiltration.

Remodeling of teaching content

The traditional teaching content of H. pylori includes physiology and structure, pathogenesis and immunity, epidemiology, clinical diseases, laboratory diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. The pedagogical focus of each section is presented in Table 1.

Teaching contents of Helicobacter pylori.

| Teaching sections | Traditional teaching contents | Key points | Advanced teaching content | Design intent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | Physiology and structure (Figure 2) | Spiral shape; motile; production of urease; microaerophilic | History of the discovery of H. pylori | Application of Koch’s postulates; transmission of norms and values present in the story |

| Part 2 | Pathogenesis and immunity | Virulence factors: urease; mucinase; phospholipases; vacuolating cytotoxin A (Vac A); cytotoxin-associated gene (cag A) | Recent advances in the pathogenesis mechanism of H. pylori infection | Integration of frontiers in H. pylori studies |

| Part 3 | Epidemiology | Humans are the primary reservoir for H. pylori; fecal-oral route | Recent data on the prevalence of H. pylori infection worldwide | H. pylori infection is an important digestive system disease |

| Part 4 | Clinical diseases | Gastritis; gastric ulcer; duodenal ulcer; gastric cancer; mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma | The dialectic between H. pylori and human health | Critical thinking development |

| Part 5 | Laboratory diagnosis | Microscopy; antigen detection; nucleic acid-based tests; culture | New diagnostic strategies such as biosensors based methods and advanced serological test | The latest techniques for laboratory diagnostics in infectious diseases |

| Part 6 | Treatment, prevention and control | Combination of a proton pump inhibitor, a macrolide and a β-lactam, with administration of 7–10 days | H. pylori eradication and gut microbiota homeostasis; a review of the current status of medication for the treatment | Critical thinking and systematic thinking development; development of new drugs |

On the basis of the traditional content, the following advanced contents were added in accordance with the learning objectives (Table 1).

History of the discovery of H. pylori

In 1984, Australian physicians Barry Marshall and Robin Warren reported a discovery that completely changed the approach to the treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease [8]. Furthermore, their findings established the foundation for understanding the cause of gastric adenocarcinomas and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas 9], [10], [11. In Barry Marshall and Robin Warren’s study, a histological analysis of gastric biopsy specimens from 100 consecutive patients undergoing gastroscopy was carried out. The researchers demonstrated the presence of curved Gram-negative rods, which they believed to be Campylobacter, in 58 patients. The bacteria were observed in the majority of patients presenting with active gastritis, gastric ulcers, and duodenal ulcers. Although similar organisms had previously been observed in gastric tissues, this report prompted a resurgence in investigations into the role of this “new” organism in gastric diseases. Despite initial skepticism, the significance of their work with Helicobacter was recognized in 2005 when Marshall and Warren received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2005/summary/).

The discovery of H. pylori provides a clear illustration of the application of Koch’s postulates in the identification of pathogenic bacteria, thereby establishing a causal relationship between bacteria and disease. Marshall and Warren exemplified the application of Koch’s postulates by observing the bacteria in a patient’s pathological specimen, isolating and culturing the bacteria, and then verifying the presence of the bacteria in their own bodies. Marshall and his assistants encountered difficulties in finding suitable animals to test the bacteria on, they decided to test the bacteria on themselves. This involved swallowing the culture of bacteria, which resulted in acute gastritis. This dedication to the pursuit of truth in science is worthy of respect and learning [12, 13].

In 2006, Barry Marshall published a book called Helicobacter Pioneer. In this publication, Barry Marshall indicates that several medical professionals, including doctors and researchers, had previously observed “small curved and S shaped bacilli” in the stomach. However, they all believed these to be transient bacteria. This was because at that time, prevailing medical opinion considered it impossible for a bacterium to survive and colonize under such a harsh and acidic environment as the stomach. However, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren observed the bacteria and applied Koch’s postulates to demonstrate the presence of bacteria in the stomach, and furthermore, to confirm the causal relationship between this bacterium and chronic digestive disease. Their discovery, therefore, can be considered a true discovery, whereas the previous observations could not be described as such. Consequently, this narrative illustrates that scientists are willing to challenge tradition and pursue the truth, which is an example worthy of emulation by students. Furthermore, it serves to illustrate the value of Koch’s postulates as a guide in the face of unknown pathogens.

The dialectic between H. pylori and human health

H. pylori is the most significant gastric pathogen, with numerous studies confirming a strong association between H. pylori infection and the development of chronic gastritis, duodenal ulcers, gastric ulcers, gastric mucosa-associated lymphomas, and gastric cancer [14]. Furthermore, it is postulated that H. pylori infection is associated with a series of extragastric manifestations, such as halitosis, eosinophilic esophagitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), liver cancer, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis, vitamin B12 deficiency, iron deficiency anemia, ophthalmic manifestations, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and cardiovascular diseases, etc. [3, 15, 16]. A positive correlation between H. pylori infection and the incidence or symptoms of these diseases has been observed in studies of patients with the aforementioned diseases or in animal models of the diseases.

However, the relationship between H. pylori infection and human health is still subject of debate. In 1997, a study suggested that H. pylori eradication can lead to reflux disease [17]. The majority of studies have demonstrated an inverse association between H. pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [4, 18]. On the other hand, "the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report" claims that H. pylori eradication has little clinical importance in acid production changes [19]. Nevertheless, the presence of H. pylori infection is thought to confer a degree of protection against multiple sclerosis, allergies, some autoimmune diseases, asthma and IBD [3].

The identification of the mechanisms by which H. pylori infection affects human health and the dialectical perspective on the relationship between microbes and host health for the purpose of better disease prevention and treatment should be reflected in the teaching of the content of this chapter.

H. pylori eradication and gut microbiota homeostasis

The eradication of H. pylori infection is a combination of proton pump inhibitors, bismuth and antibiotics, with dosing cycles ranging from seven to fourteen days. A long-term antibiotic combination is an effective method for the clearance of H. pylori; however, it is also important to consider the potential impact of antibiotic application on the gut microbiota homeostasis [2]. The gut microbiota dysbiosis will have adverse consequences. In order to adopt effective clinical diagnostic and therapeutic measures, it is essential to consider the human body as a unified system when we use antibiotics for treatment in bacterial infection. It is imperative that the principles of rational medication use to ensure microbiota homeostasis in the body be taught throughout the medical microbiology curriculum.

Other cutting-edge teaching content

The latest data on the prevalence of H. pylori infection worldwide, recent advances in the pathogenesis mechanism of H. pylori infection, new diagnostic strategies, a review of the current status of medication for the treatment of H. pylori infection, the One Health concept in the prevention and control of the spread of H. pylori resistance will also be included during the teaching process 20], [21], [22], [23], [24.

Case design

In addition to the theoretical content, for the purpose of facilitating the integration of organ-systems thinking within the curriculum and to reinforce the development of clinical thinking, it is recommended that this subject be taught in the form of case-based learning (CBL). It is therefore essential to conduct case design.

Case description:

A 24-year-old male presented to his family physician with a chief complaint of abdominal discomfort that had been progressively worsening over the past three weeks. He stated that the symptoms often abated immediately after meals or the ingestion of antacids. Additionally, he reported occasional heartburn but denied the presence of fevers, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, or bloody stools.

The patient was a journalist and was accustomed to working in a stressful environment. No other noteworthy prior social or medical history was identified.

Physical examination

Vital signs: temperature (T): 36.8 °C; pulse (P): 80/min; respiration (R): 15/min; blood pressure (BP) 106/75 mmHg.

A physical examination of the abdomen revealed mild tenderness in the mid-epigastric region, with no rebound. The rectal examination yielded normal results, and no blood was observed on the fecal occult blood test (Hemoccult test).

Laboratory diagnosis

Urea breath test: positive

Blood: Hematocrit test: 39 %; white blood cell count (WBC): 7,500/μL; Differential: normal; Serum chemistries: normal.

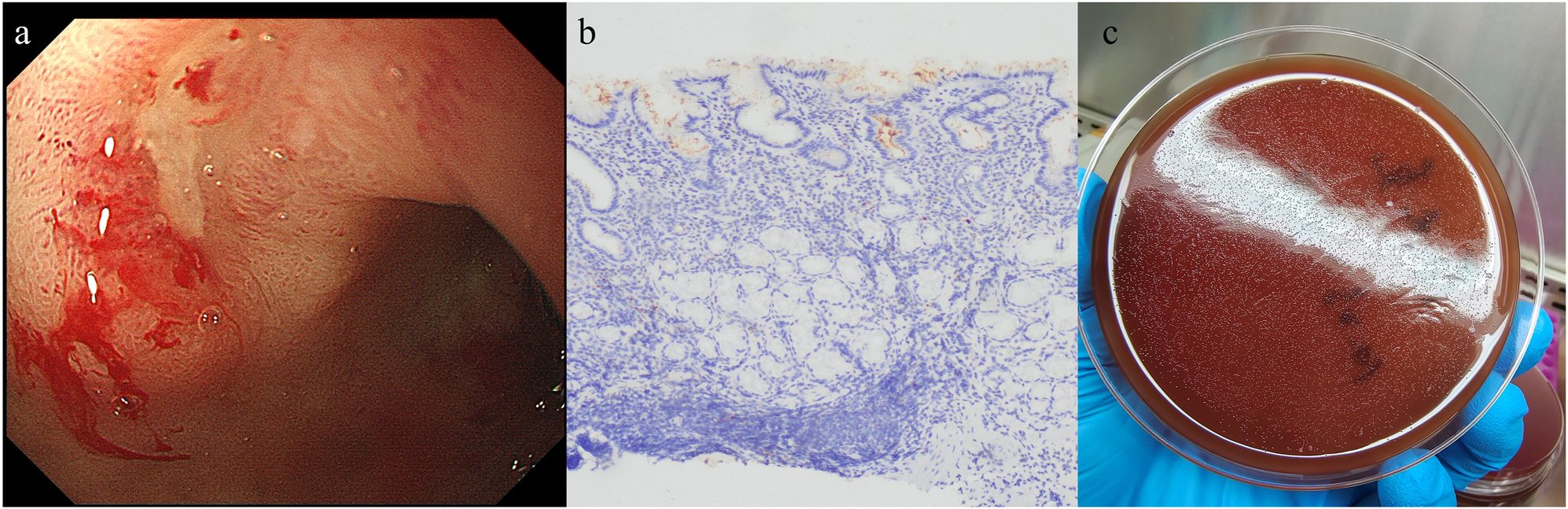

Endoscopic examination: The image demonstrates a duodenal ulcer with evidence of bleeding (Figure 3a).

Histologic examination: Endoscopic biopsy specimens were sectioned, stained, and examined microscopically. S-shaped organisms were observed adhering to gastric epithelial cells (Figure 3b).

Culture: endoscopic biopsy specimens cultured on brain-heart broth medium with blood under microaerophilic environment. After 96 h, colonies appeared and Gram staining was conducted, Gram-negative bacteria were observed under the microscope (Figure 3c).

Questions:

What is the diagnosis of this case?

Describe the microbiologic properties of the etiologic agent.

Compare the similarities and differences with other digestive system pathogens.

Whether all patients infected with the pathogen should undergo eradication therapy?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of existing treatment strategies? What is the current state of research into new treatments?

Teaching materials in case-based learning (CBL). (a) Image of endoscopic examination. Gastric ulcer with active bleeding was observed. (b) Histologic examination of Helicobacter pylori infected tissue (immunohistochemistry, ×40). H. pylori is stained brown in the gastric epithelial layer. (c) H. pylori colonies on culture medium (brain-heart infusion blood agar). Small, transparent colonies appeared on the plate after 96 h of culture.

Teaching model and methods

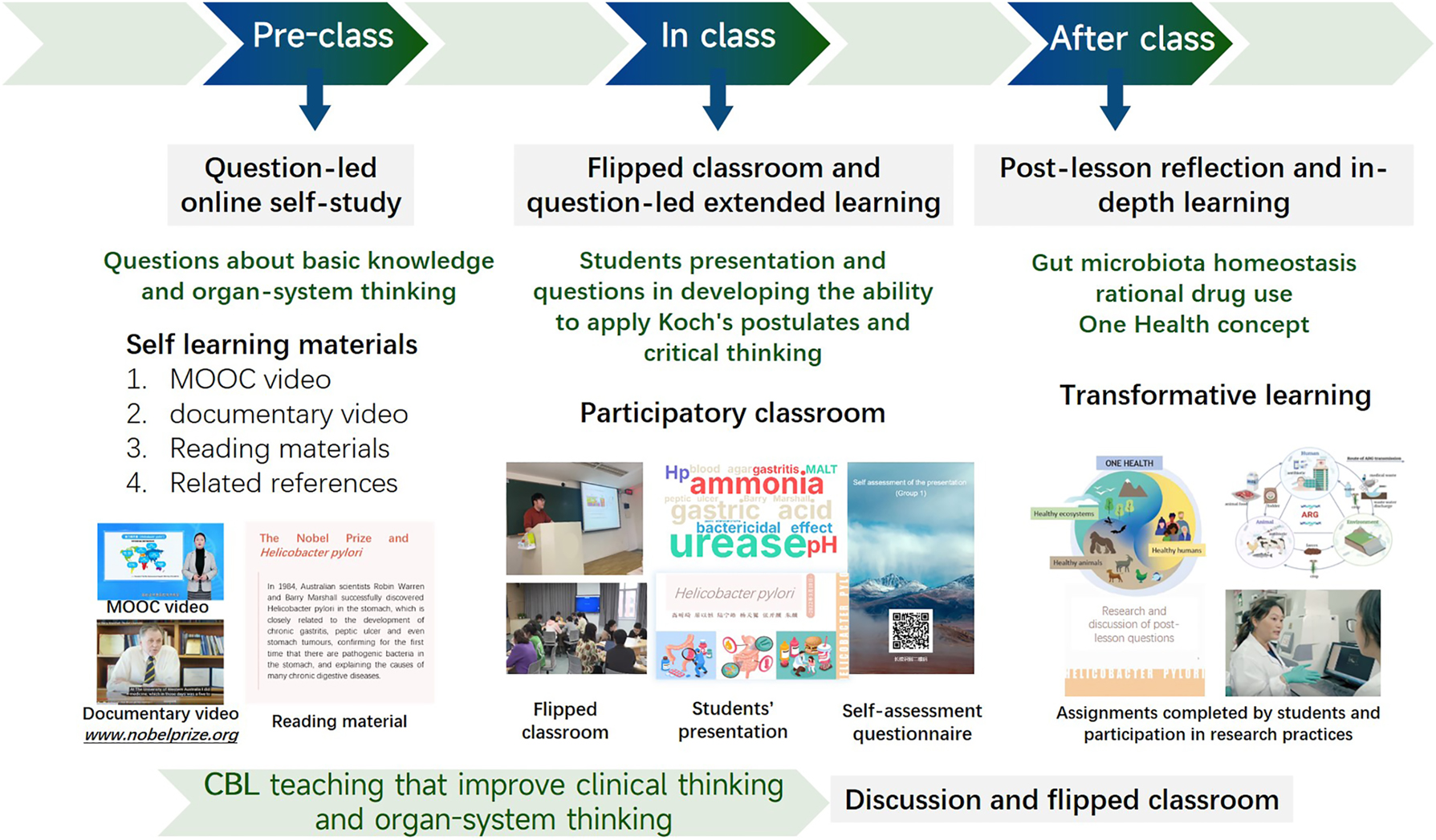

In order to achieve the corresponding learning objectives, questions-oriented teaching model is implemented, certain questions are designed before, during and after the lesson to guide students to learn independently, while teachers provide corresponding teaching resources (Figure 4).

Teaching model of Helicobacter pylori. The teaching process is divided into three distinct phases: pre-class, in-class, and after-class. Pre-class: students engage in question-led online self-learning; in-class: the flipped classroom approach is employed, with students engaged in question-led extended learning; after-class: students engage in deep learning and receive reflection. Throughout the process, multiple teaching activities are applied, and CBL is integrated to develop clinical and systems thinking. CBL, case-based learning; MOOC, massive open online course.

Pre-class

In this section, students are required to complete a question-led online self-study. Teachers prepare a series of learning materials on the course website, including original massive open online courses (MOOC) videos, a documentary video, and an article from WeChat official account. The MOOC video was teacher filmed lectures on the basic knowledge of H. pylori. While the documentary video is about Barry Marshall telling the story of his discovery of H. pylori with Robin Warren. Together with the article from WeChat, the students can gain an understanding of the whole process of H. pylori discovery.

During self-study, the teacher poses two questions:

In the digestive system, why does H. pylori infect the stomach but not the intestines?

Given the high prevalence of H. pylori infection, why is it discovered late?

After completing the self-study online, students will draw their own mind maps in relation to the questions and prepare a class presentation on the two questions.

The intention of question design:

These two questions, on the one hand, reinforce students’ organ-system thinking and, on the other hand, inspire their thinking and understanding of the basic characteristics of bacteria through contradictions.

In-class

Students are required to work in small groups to present in class, according to their pre-class preparation. This involves asking questions and interacting with each other in order to deepen their learning, while simultaneously evaluating each other.

Following the presentation by the students, the teacher provides a summary and then poses two questions to facilitate further study and thinking.

Who actually discovered H. pylori for the first time and what significant implications does this discovery have for medical students?

How to understand the relationship between H. pylori and human health precisely?

The intention of question design:

The first question is designed in the hope that students will learn from the following three aspects: the guiding significance of Koch’s postulates for the understanding of future emerging pathogens; to understand that seeing is not the same as discovering in science, reflecting the spirit of scientists’ courageous challenge and the pursuit of truth; to get touched by the dedication of the discoverer who tested the bacteria on his own.

The second question is designed to lead students to a critical understanding of the relationship between H. pylori and the host, to introduce cutting-edge advances in the protective role that H. pylori plays against some diseases, and also to stimulate students’ interest in science through the paradox between pathogenicity and protection.

After-class

After the class, the teacher presents two cutting-edge questions as below, based on these two questions, students complete micro-lecture recording assignments, make a mechanism figure, and students who have interest in H. pylori related studies can participate in scientific research training in the second classroom.

What effect will antibiotic treatment of H. pylori have on the gastrointestinal microbiota?

Explaining the spread of antimicrobial resistance of H. pylori from the One Health perspective.

The intention of question design:

These two questions are designed to incorporate the concepts of rational drug use, the impact of antibiotics on gut microbiota homeostasis, and the concept of One Health in the prevention and control of antimicrobial resistance. “One Health” approach emphasizes the harmony between humans, animals, and the environment, and encourages interdisciplinary communication and multi-sectoral collaboration which plays an important role in promoting the health of people, animals, and ecosystems.

CBL teaching

Discussion and flipped classroom are used in the CBL teaching. The application of online instant interactive system in the classroom, such as Chaoxing platform, Rain classroom, and Wenjuanxing, etc., can make the whole process of learning more active. Depending on the size of the class, students will be divided into groups of four to five, and the case content will be discussed and interacted with step by step based on the questions until the whole case is completed.

Teaching and learning evaluations

In order to ascertain the extent to which learning objectives have been achieved, it is necessary to adopt a multifaceted approach for assessment, encompassing a range of methodologies, both before, during and after the class (Table 2). Process and formative evaluation were both involved.

Assessment map for the learning of Helicobacter pylori.

| Process stage | Assessment | Points (100 in total) | Learning objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-class | Online unit test (10 points) | 10 | b, c |

| Completion of online learning resources | 8 | a–c | |

| Open questions preparation | 10 | b–d | |

| Design of mind map | 5 | b, c | |

| In-class | Presentations (content, logicality, academic norms, aesthetic value) | 20 | a–d |

| Group-based learning activities based on presentations | 5 | a–d | |

| Group-based discussion based on open questions | 9 | a, e | |

| After-class | Question-based assignments | 20 | e |

| Case-based learning | Discussions (participation, capacity to access information, ability to cooperate and communicate) | 3 | b–d |

| Answers of questions | 10 | b–d |

The objective of the online unit test is to ascertain whether the students have acquired a sufficient understanding of the fundamental principles associated with H. pylori. The remaining assessment strategies are designed to evaluate the integrated acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitude. Students’ self-improvement is self-assessed through questionnaires. At the end of this unit, teachers distribute evaluation questionnaires to find out students’ opinions and suggestions on the teaching model.

Teachers gain insight into their students’ learning through the utilization of diverse assessment strategies, which are subsequently conveyed to the students. In response to the assessment outcomes, teachers modify the teaching content and models. The entire process is cyclical, progressing in the form of “evaluation-feedback-improvement-enhancement.”

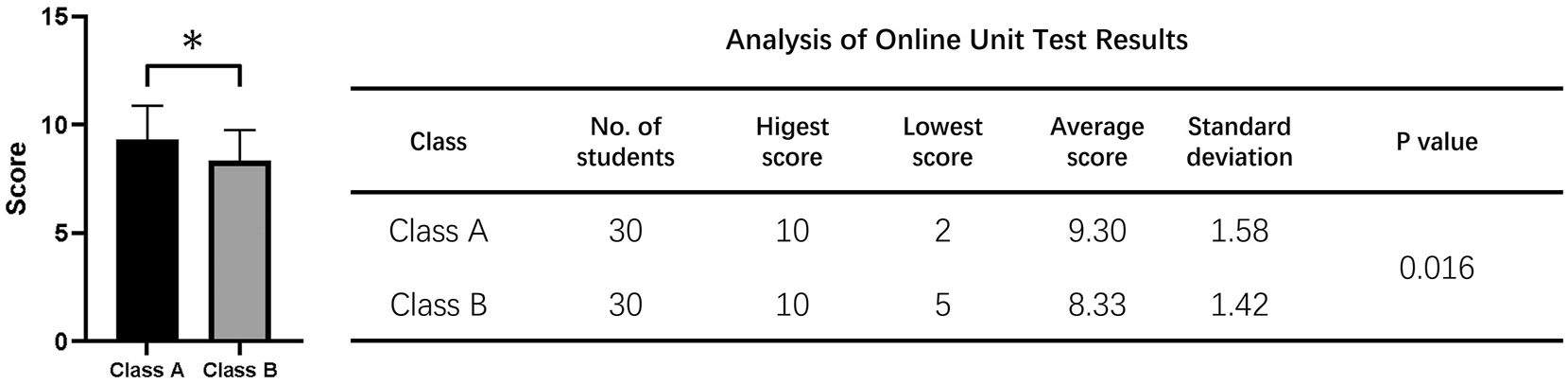

In order to confirm the real and effective results of the teaching design, the class using this teaching strategy is defined as Class A, while the class using traditional lecture-centered parallel teaching is defined as Class B. Class B is taught by the same teacher, takes knowledge objectives as the important teaching objectives, focuses on learning and consolidating core knowledge, and does not adopt the teaching methods and modes of discussion, online/offline learning and CBL. At the end of the course, the same online unit test will be used to check the results.

Students’ achievement and feedback

With regard to the acquisition of the fundamental knowledge of H. pylori, particularly in terms of performance on the online unit test, the class that employed this teaching model demonstrated significantly higher scores than the class that did not utilize this model (Figure 5).

Online unit test results in different class groups. The implementation of an effective teaching design and practice led to a significant increase in the performance of Class A students on online unit tests, in comparison to their counterparts in Class B. The experimental group, designated as Class A, was taught using the specified teaching design, while the control group, designated as Class B, utilized the traditional teaching mode.

Based on the results of questionnaire, the self-improvement ratings were found to be significantly higher in classes that employed the novel teaching model described above (Table 3). Furthermore, more favorable evaluations of teachers and teaching are achieved.

Statistical results of the questionnaire.

| Learning outcomes | Survey content | Statistical results (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very helpful/ | Helpful/satisfied/ | Unhelpful/ | |||||

| very satisfied/high | medium | unsatisfied/low | |||||

| Class A | Class B | Class A | Class B | Class A | Class B | ||

| Knowledge | Gain a comprehensive understanding of the basic knowledge of Helicobacter pylori | 37 | 32 | 63 | 60 | 0 | 8 |

| Retell the history of the discovery of H. pylori | 50 | 32 | 50 | 23 | 0 | 45 | |

| Have an understanding of the recent advances in the pathogenesis mechanism of H. pylori infection | 43 | 30 | 55 | 42 | 2 | 28 | |

| Review the recent data on the prevalence of H. pylori infection worldwide | 40 | 23 | 58 | 44 | 2 | 33 | |

| Describe the new diagnostic, prevention and treatment strategies | 42 | 12 | 57 | 34 | 1 | 54 | |

| Skill | Design a process for the identification of emerging pathogens | 42 | 11 | 56 | 18 | 2 | 71 |

| Identify similarities and differences between H. pylori and other gastrointestinal pathogens | 33 | 21 | 64 | 68 | 3 | 11 | |

| Attitude | Understand the criticism and dedication in the discovery of H. pylori | 55 | 12 | 45 | 60 | 0 | 28 |

| Have a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between H. pylori and human health | 56 | 20 | 44 | 31 | 0 | 49 | |

| Teaching evaluation | Satisfaction with teaching contents | 72 | 26 | 25 | 50 | 3 | 24 |

| Satisfaction with teaching model | 66 | 40 | 34 | 49 | 0 | 11 | |

| Satisfaction with learning needs | 69 | 42 | 30 | 41 | 1 | 17 | |

| Satisfaction with the teacher | 82 | 70 | 18 | 22 | 0 | 8 | |

Discussion

In light of the advancements in medicine and medical education that have occurred in the new era, there is a pressing need to produce a greater number of exceptional medical professionals. Furthermore, teaching and learning must extend beyond the mere transfer of knowledge, with a greater emphasis placed on the development of competencies, values and literacy. In the discipline of medical microbiology, in addition to core knowledge and skills, there is a need to place greater emphasis on scientific thinking and the integration of cutting-edge knowledge and concepts. This should guide students to understand existing pathogens and, at the same time, to develop the ability to understand unknown pathogens. It should also facilitate the scientific understanding of microorganisms and the adoption of appropriate measures and application of due diligence in the prevention and control of pathogenic microorganisms. Furthermore, it should encourage the One Health perspective.

This teaching design incorporates learning objectives within the framework of outcome-based education (OBE) [25], in alignment with the characteristics of the academic discipline’s development. It adheres to the aforementioned teaching principles and introduces significant innovations in the teaching of this chapter, including teaching contents, teaching model and assessments. The results of the questionnaire administered to the students indicate that the content of the traditional textbooks is no longer sufficient to meet their learning needs. The content was remodeled in accordance with the learning objectives, the expansion of the teaching and learning content will facilitate the achievement of higher-order talent development goals and encourage a re-determination of the way students think about microbiology issues. After this lesson, students were able to understand “to see is not to find.” They also gained insight into the dedication of scientists, as well as an understanding of Koch’s postulate and its application in identifying new pathogens, through the discovery of H. pylori. An understanding of the dialectical relationship between H. pylori and its host enables a multifaceted perspective on microorganisms. The concept of organ-systems thinking is reinforced through a comparison of the characteristics of different pathogens affecting the digestive system. The impact of antibiotic application on the gut microbiota was learned through the treatment of H. pylori. By posing One Health-related questions, students can gain an understanding of the close relationship between pathogen control and ecological health. The case design was developed with the learning objectives, while also facilitating the development of students’ clinical thinking.

The results of the questionnaire indicated that students are highly satisfied with the teaching model, with a rating of 100 %. This teaching mode represents a significant difference from the traditional lecture-based approach, combining online and offline elements to create a blended learning environment. It incorporates a diverse array of teaching resources and allows students to engage in a variety of learning activities, including independent study, classroom presentations, discussions, and extended reading. This multifaceted approach enhances the learning experience for students. It also improves the learning efficiency of students. Before the class, students’ scores on unit tests were significantly improved, which suggested that pre-class design ensures that students learn and master the most essential knowledge.

In terms of the teaching effect, students have demonstrated that knowledge, skill and attitude can be simultaneously enhanced, and have expressed high levels of satisfaction with the teaching design in this chapter.

Conclusions

The teaching design of H. pylori needs to be aligned with the teaching objectives of the curriculum medical microbiology, including the thinking in terms of the learning objectives, teaching content, teaching modes and evaluation methods of the content of this chapter, to create an interactive and highly participatory classroom capable of enhancing scientific thinking and shaping values in students, and to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of teaching and learning. The teaching design of this chapter has a particular demonstrative effect.

Funding source: Higher Education Research Planning Project by China Association of Higher Education

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24KC0416

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Xiaoyin Niu for revising the article and my colleagues Jinhong Qin, Wei Zhao, Jing Tao and Yufeng Yao from the medical microbiology teaching group.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Chang Liu designed and implemented the teaching design, Ping He provided assistance in teaching process, Yundong Sun and Hong Lu provided teaching resources such as photographs, Zhuoyang Zhang assisted in making online teaching resources, and Ke Dong was involved in writing and revising the manuscript. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Medical Education Research Project of Medical Education Branch of Chinese Medical Association (2018B-N03011, 2023B344).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Mettenleiter, TC, Markotter, W, Charron, DF, Adisasmito, WB, Almuhairi, S, Behravesh, CB, et al.. The one health high-level expert panel (OHHLEP). One Health Outlook 2023;5:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-023-00085-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Lopetuso, LR, Napoli, M, Rizzatti, G, Scaldaferri, F, Franceschi, F, Gasbarrini, A. Considering gut microbiota disturbance in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;12:899–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2018.1503946.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Santos, MLC, de Brito, BB, da Silva, FAF, Sampaio, MM, Marques, HS, Oliveira, ESN, et al.. Helicobacter pylori infection: beyond gastric manifestations. World J Gastroenterol 2020;26:4076–93. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Dellon, ES, Peery, AF, Shaheen, NJ, Morgan, DR, Hurrell, JM, Lash, RH, et al.. Inverse association of esophageal eosinophilia with Helicobacter pylori based on analysis of a US pathology database. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1586–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Amberbir, A, Medhin, G, Erku, W, Alem, A, Simms, R, Robinson, K, et al.. Effects of Helicobacter pylori, geohelminth infection and selected commensal bacteria on the risk of allergic disease and sensitization in 3-year-old Ethiopian children. Clin Exp Allergy 2011;41:1422–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03831.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Chen, Y, Blaser, MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis 2008;198:553–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/590158.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Herbarth, O, Bauer, M, Fritz, GJ, Herbarth, P, Rolle-Kampczyk, U, Krumbiegel, P, et al.. Helicobacter pylori colonisation and eczema. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:638–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.046706.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Marshall, BJ, Warren, JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1984;1:1311–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Group TES. Epidemiology of, and risk factors for, Helicobacter pylori infection among 3194 asymptomatic subjects in 17 populations. Gut 1993;34:1672–6.10.1136/gut.34.12.1672Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Group IW. IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: some industrial chemicals Lyon (FR), 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994;60:1–560.Search in Google Scholar

11. Herrera, V, Parsonnet, J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:971–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03031.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Marshall, B, Azad, M. Q&: Barry Marshall. A bold experiment. Nature 2014;514:S6–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/514s6a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Marshall, B, Adams, PC. Helicobacter pylori--a Nobel pursuit? Can J Gastroenterol 2008;22:895–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/459810.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Suerbaum, S, Michetti, P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1175–86. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra020542.Search in Google Scholar

15. de Korwin, JD, Ianiro, G, Gibiino, G, Gasbarrini, A. Helicobacter pylori infection and extragastric diseases in 2017. Helicobacter 2017;22. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12411.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Gravina, AG, Zagari, RM, De Musis, C, Romano, L, Loguercio, C, Romano, M. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:3204–21. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Labenz, J, Blum, AL, Bayerdorffer, E, Meining, A, Stolte, M, Borsch, G. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer may provoke reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1442–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70024-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Kandulski, A, Malfertheiner, P. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014;30:402–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/mog.0000000000000085.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Malfertheiner, P, Megraud, F, O’Morain, CA, Gisbert, JP, Kuipers, EJ, Axon, AT, et al.. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/florence Consensus report. Gut 2017;66:6–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Li, Y, Choi, H, Leung, K, Jiang, F, Graham, DY, Leung, WK. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;8:553–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(23)00070-5.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gravina, AG, Priadko, K, Ciamarra, P, Granata, L, Facchiano, A, Miranda, A, et al.. Extra-gastric manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Med 2020;9:3887. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9123887.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Sigal, M, Logan, CY, Kapalczynska, M, Mollenkopf, HJ, Berger, H, Wiedenmann, B, et al.. Stromal R-spondin orchestrates gastric epithelial stem cells and gland homeostasis. Nature 2017;548:451–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23642.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Cardos, AI, Maghiar, A, Zaha, DC, Pop, O, Fritea, L, Miere Groza, F, et al.. Evolution of diagnostic methods for Helicobacter pylori infections: from traditional tests to high technology, advanced sensitivity and discrimination tools. Diagnostics 2022;12:508. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020508.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Shakir, SM, Shakir, FA, Couturier, MR. Updates to the diagnosis and clinical management of Helicobacter pylori infections. Clin Chem 2023;69:869–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvad081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Jha, S, Sethi, R, Kumar, M, Khorwal, G. Comparative study of the flipped classroom and traditional lecture methods in anatomy teaching. Cureus 2024;16:e64378. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.64378.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Evolving landscapes in global medical education: navigating challenges and embracing innovation

- Review Articles

- Embarking on the era in new medicine: reshaping the systems of medical education and knowledge

- Aligning the education of medical students to healthcare in the UK

- Characteristics and considerations of French medical education

- Research Articles

- “Global challenge program” projects themed on preventing zoonosis: developing One Health core competences in medical students at SJTU

- Innovative exploration of designing the ‘Host Defense and Immunology’ course based on the concept of seamless learning

- Comparing the effects of blended learning and traditional instruction on “Medical Genetics and Embryonic Development” in undergraduate medical students: a randomized controlled trial

- The application of the “PICO” teaching model in clinical research course for medical students

- Factors bridging medical graduate students’ training and future academic achievements of dermatologists in China

- The teaching design and implementation of “Helicobacter pylori” in medical microbiology

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Evolving landscapes in global medical education: navigating challenges and embracing innovation

- Review Articles

- Embarking on the era in new medicine: reshaping the systems of medical education and knowledge

- Aligning the education of medical students to healthcare in the UK

- Characteristics and considerations of French medical education

- Research Articles

- “Global challenge program” projects themed on preventing zoonosis: developing One Health core competences in medical students at SJTU

- Innovative exploration of designing the ‘Host Defense and Immunology’ course based on the concept of seamless learning

- Comparing the effects of blended learning and traditional instruction on “Medical Genetics and Embryonic Development” in undergraduate medical students: a randomized controlled trial

- The application of the “PICO” teaching model in clinical research course for medical students

- Factors bridging medical graduate students’ training and future academic achievements of dermatologists in China

- The teaching design and implementation of “Helicobacter pylori” in medical microbiology