Abstract

French medical education, with a long history and guided by laws and decrees set by the French Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health, aims at elite training, focusing on the cultivation of students’ clinical practice and scientific research capabilities, and implementing a unified medical talent training model. The French medical education system continuously seeks innovation and change. In September 2020, a new round of reforms was initiated in aspects such as admission pathways, examination system, and assessment methods. These changes aim to enhance medical students’ disciplinary backgrounds, strengthen process-based assessment, and foster the development of versatile medical professionals. This article analyzes the characteristics of French medical education and the main measures of this round of reforms, providing insights and considerations for the training of cultivated medical talents in China.

Introduction

In recent years, rapid development of global science and technology has brought huge impetus to the field of medicine, imposing higher demands on the training of medical talents. Many countries have launched a new round of medical education reforms to enhance the quality of medical training and to respond to the opportunities and challenges in healthcare.

French medical education has a long history and aims to cultivate elite talents. It has the characteristics of long academic system and high elimination rate. In recent years, the French healthcare system has faced challenges such as a decrease in the total number of doctors, aging medical personnel, and homogeneity in the backgrounds of medical students. In November 2019, a new round of medical education reforms was initiated in France by promulgating the “Decree on Entry into Medicine, Pharmacy, Dentistry and Midwifery Training”, aiming to promote the training of multi-disciplinary medical talents [1].

Similarly, the medical education and medical talent training in China are also faced with challenges related to an imperfect medical education management system, the incompatibility of academic degrees and professional settings with the international status quo, the shortage of multidisciplinary medical talents and the imbalance of regional health talents [2, 3]. The “Opinions on Deepening Medical Education Reform and Development through Medical-Educational Collaboration” issued by the State Council’s Office has proposed to “design medical development with new concepts, advance medical education with new positioning, strengthen medical student training with new content, and lead medical education innovation with the new medical science system” [4]. How to cultivate innovative “Medical + X” medical talents is a new problem that needs to be solved in the medical education reform.

The present review will introduce the overview of medical education in France, especially the characteristics of its three phases and the content of the latest round of reforms, providing ideas and references for the training of multidisciplinary integrated “Medical + X” medical talents and medical education reform in China.

Overview of medical resources in France

France, with a total area of 550,000 square kilometers, is divided into 13 regions and 94 departments, with a total population of 68.04 million. As a developed country, France maintains a high overall health standard, ranking among the top in the world [5]. The average life expectancy in France is 85.4 years for women and 79.3 years for men [6]. There are a total of 2,989 medical institutions of various levels in France, with a total of 387,000 inpatient beds and 80,000 day surgery beds [7]. France has a total of 230,000 registered practicing physicians, with general physicians accounting for 43 % of the total. There are also 45,200 registered dentists, 24,600 registered midwives, 73,400 registered pharmacists, and 632,600 registered nurses. In 2021, France registered 8,613 new physicians, a 4.2 % increase from the previous year [8]. In 2021, the total health expenditure in France was 235.8 billion euros, representing 12.3 % of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Notably, national health insurance covered over 80 % of these costs, with an average medical expenditure of 3,475 euros per person [9].

Overview of medical education in France

Basic information about medical schools in France

In France, the early medical education institutions were called “Schools of Medicine” (École de Médecine). The first school of medicine, named after Hippocrates (Civitas Hippocratica), was established in 846, enrolling about 10 medical students each year. The first “Faculty of Medicine” (Faculté de Médecine) was established in 1137 in Montpellier, southern France, making it the world’s oldest professional medical institution [10].

French medical education, with its long and rich history, has accumulated extensive experience in constructing medical education systems [11]. Unlike the tradition where elite education is distributed in private universities, French medical education is predominantly situated within public university medical schools. Following the reform of the medical school system in 1968, medical education laws and regulations were progressively implemented nationwide, leading to the establishment of the medical education system [12]. France currently has 45 faculties of medicine, with the largest medical school alliance located in Paris, mainly consisting of Paris Cité University School of Medicine (formerly the University of Paris V and VII), Sorbonne University School of Medicine (formerly the University of Paris VI), and Paris-Saclay University School of Medicine (formerly the University of Paris XI). French medical and health education is of high quality, consistently ranking among the top in the world. The Clinical Medicine program of the Paris Cité University ranks the second and its Health and Hygiene program ranks the first on the European continent [13]. The largest medical center in Europe is located in Lille, which has the most clinical inpatient beds and the largest clinical teaching base.

Policy and overall structure of medical education in France

Health and Hygiene education in France is divided into five parts, including medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, midwifery, and sports rehabilitation. Under the guidance of laws and decrees issued by the French Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health, each part has a unified academic system, learning objectives, European credits, internship and professional diplomas. Each faculty of medicine establishes its curriculum and course content within the overall framework of medical education set by the national authorities.

As a part of Health and Hygiene education, French medical education is characterized by its elite education model. In France, medical education is strictly managed, with a rigorous legal framework governing the education system. The French Education Code (Code de l’Éducation) explicitly defines the main methods for educating medical talents, highlighting that the purpose of medical education is to cultivate excellent medical and health professionals, provide high-quality medical services, and offer equal medical resources to residents in need, alleviating their illnesses [14].

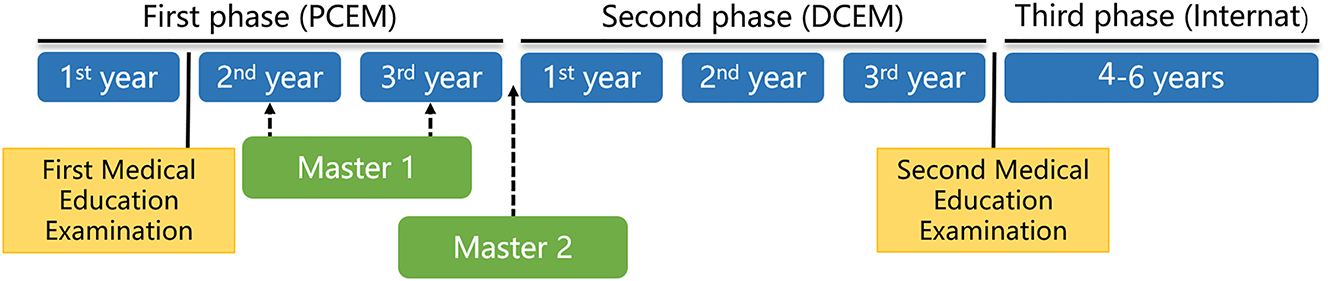

French medical education lasts 9–12 years and is divided into three phases, including the first phase (Premier cycle des études médicales, PCEM), the second phase (Deuxième cycle des études médicales, DCEM), and the third phase of residency training (Internat). Both the first and second phases last three years, while the third phase varies from four to six years depending on the medical disciplines (Figure 1).

Timeline of medical education and medical-science master’s training in France. PCEM, premier cycle des études médicales; DCEM, deuxième cycle des études médicales.

Three phases of medical education in France

First phase of medical education in France

As previously indicated, the first phase (PCEM) lasts three years. The first year of PCEM is a preparatory stage for medical studies. The specialized medical courses begin in the second year. According to the decree of March 22, 2011, the first phase requires the completion of 180 European Credits Transfer System (ECTS) [15]. Students who pass the first phase assessment will obtain the “Diplôme de Formation Générale en Sciences Médicales” (DFGSM).

First phase curriculum

Since 2010, all students in medical and related programs (including dentistry, midwifery, pharmacy, etc.) must finish a “First Year Common Health Courses” (Première Année Commune aux Études de Santé, PACES) accounting for 60 credits, according to the decree of October 28, 2009 [16]. The second and third-year courses each account for 60 credits. They are composed of mandatory courses, elective courses and clinical internships. Students will study basic medical sciences (biology, biophysics-nuclear medicine, genetics, immunology, bacteriology, virology, etc.), symptomatology, public health, medical English and clinical internships during the second and the third year of PCEM.

French medical education places great emphasis on the clinical skills training of medical students. All medical students must complete various clinical practices at different phases and obtain corresponding credits and certificates before beginning the next phase of medical education. During the first year, students must complete clinical internships like “Emergency Training” and “Fundamentals of Clinical Care.” Before starting the second phase, students must obtain a “Level 1 Emergency Skills and Care Training Certificate”, as well as “Identification and Prevention of Psychosocial Risks in Student and Professional Environments” [17].

First medical education examination

After completing the first-year PACES courses, students face the first national selection examination in medical education, known as the PACES exam (concours PACES) [18]. This exam is conducted by the National Management Center of the French Ministry of Health (Centre National de Gestion).

For many years, faculties of medicine in France have adopted a “Numerus Clausus” system, limiting the number of admissions at the end of the first year based on the national demand for doctors announced by the French Ministries of Education and Health. This system, with an average admission rate of only 10 %–18 %, results in many students being eliminated after the first year [19]. This high elimination rate forces many excellent high school graduates, who are eager to pursue a medical career, to re-enroll in alternative undergraduate programs. Moreover, the credits earned in the first year’s “Common Health Course” become invalid, resulting in a substantial waste of educational resources and loss of talent.

In response to the uneven distribution of medical resources [20], the shortage of medical staff, and the emergence of medical deserts in various parts of France [21], the French Ministries of Education and Health re-evaluated the “Numerus Clausus” system. In July 2019, the French Parliament passed the “My Health 2020” (Ma santé 2020) decree, aiming to increase the number of doctors in France by at least 20 % [22]. In November 2019, France issued a decree cancelling the “Numerus Clausus” and implementing a “Numerus Apertus” system. Each faculty of medicine, in consultation with the Health Department of its belonged province, determines the admission numbers for the following year in medicine, midwifery, dentistry, pharmacy, or physiotherapy (Médecine, Maïeutique, Odontologie, Pharmacie, Kinésithérapie, MMPOK) [23].

According to this decree [23], students have at least two different pathways to pursue an undergraduate degree in Medicine from 2020, the “Special Health Pathway” (Parcours Spécifique Accès Santé, PASS) and the “Undergraduate Medical Entrance Pathway” (Licence Accès Santé, L.AS) (Figure 2).

“Special health pathway” and “undergraduate medical entrance pathway” to pursue an undergraduate degree in medicine. PASS, parcours spécifique accès santé; L.AS, licence accès santé; MMPOK, médecine, maïeutique, pharmacie, odontologie, kinésithérapie.

The “Special Health Pathway” is designed for first-year medical students. The credits for the first year remain at 60. In addition to majoring in pre-medical studies, students are required to take non-medical courses such as physics, chemistry, or language studies. The National Management Center now conducts a comprehensive assessment of students’ first-year performance, replacing the PACES exam. The scores range from 0 to 20, with 10 being the passing mark. Students who fail lose the chance to retake the course and may register for other non-medical undergraduate programs. Each medical school sets its own cut-off score, for example, 18 points. Students scoring 18 or above automatically advance to the second year in different MMPOK specialties, while those scoring between 10 and 18 participate in the next round of selection exams (Concours de Médecine). Those who pass this exam continue their studies in MMPOK specialties. Students who fail can directly enroll in other undergraduate programs and start their second undergraduate year. Their first-year credits are recognized by the ECTS [24, 25].

The “Undergraduate Medical Entrance Pathway” primarily targets non-medical undergraduate students, which is a highlight of the current medical education reform in France. Any undergraduate student in a non-medical field can minor in “Common Health Courses.” Students can apply to transfer to MMPOK specialties at the end of their second or third undergraduate year. Each student has two opportunities to apply during their undergraduate studies, and those who pass the selection exam can transfer to an MMPOK specialty. This reform not only opens up medical study pathways for non-medical students but also provides an opportunity for students who did not pass the PASS course in their first year to return to medical studies.

Contrary to the “Numerus Clausus” system, this reform allows more students to gain access to the second year of healthcare studies. In 2020–2021, the proportion of second-year admission has increased significantly, with the admission rate being between 10 % and 45.2 % [26].

Second phase of medical education in France

The second phase of medical education (DCEM) spans three years, during which students delve into more comprehensive and in-depth clinical professional studies.

Second phase curriculum

The second phase mainly consists of clinical medical courses and internships. Theoretical courses include geriatrics, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, oncology, anesthesiology, as well as other clinical specialties. By learning the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment, prevention and nursing care related to common diseases in different clinical specialties, students cultivate a clinical mindset and improve clinical practice skills. Courses in social and human sciences and medical humanities are also offered in the second phase to help students gain a deeper understanding of the healthcare system in France, recognize the history and culture of different regions, and improve medical communication and patient interaction skills. During this phase, students are also required to acquire skills related to information systems and learn to use information technology for processing medical and health data.

The second phase of clinical internship lasts for a total of 18 months. Students can choose either full-time (18 months in total) or part-time (36 months in total) internships, with a minimum of 5 months (full-time) or 10 months (part-time) per year. Students have some autonomy in selecting internship departments and scheduling, but must complete internships in emergency and surgery, and at least 25 on-call shifts (mainly in emergency) within three years. The performance of internships is evaluated by clinical department directors. Medical students must obtain a “Level 2 Emergency Skills and Care Training Certificate” during this phase. As hospital employees, interns receive an average salary of about 2,000 euros per month. Students who complete 120 European credits and pass exams over three years receive the “Diplôme de Formation Approfondie en Sciences Médicales,” equivalent to a master’s degree.

Second medical education examination

The second medical education examination takes place at the end of DCEM. Before the present reforms, this examination is known as the “National Ranking Exam” (Epreuves Classantes Nationales, ECN) [27]. Each year, the French Ministries of Education and Health jointly plan and publish the number and locations of 44 national resident positions in various medical specialties Based on exam rankings, students choose their desired clinical specialty and the affiliated university hospital, beginning the third phase of residency studies [28]. After nearly 20 years of practice, the Ministries of Education and Health found that the “National Ranking” system often resulted in neglection of remote areas. Some students preferred to retake the exam the following year to secure a better ranking for their desired specialty or location in a major city, exacerbating the uneven distribution of medical resources and the shortage of medical personnel in remote areas.

To address the drawbacks of the ECN exam, the “ranking” system will be replaced by “matching” from 2024 [29, 30]. The student’s score for matching consists of three parts: the medical knowledge exam (Epreuves dématérialisées nationales, EDN) (60 %), the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) (30 %), and the formative assessment (10 %) [31].

The EDN exam primarily tests medical professional knowledge, with single-choice and multiple-choice questions. It is scheduled before the OSCE and is held in October of the final year of the second phase. The EDN consists of four exams, each lasting 3 h. The fourth exam is “critical reading,” in which students read two articles concerning clinical research and the pathophysiology of disease and answer questions within 3 h.

Medical knowledge in the EDN is categorized into Level A (essential clinical knowledge) and Level B (in-depth specialty knowledge). Students must score ≥14/20 in Level A to proceed to the OSCE exam. A retake opportunity is available in January of the following year, organized by each faculty of medicine. Students who fail the retake can participate in the EDN exam again the following year.

The OSCE primarily assesses clinical skills, including clinical reasoning, clinical skills and doctor-patient communication. The exam simulates clinical scenarios, each lasting 7–10 min, where students complete a series of clinical practices, including data collection, clinical examination, and treatment. The OSCE exam is scheduled in the spring of the sixth year, and students must score ≥10/20 to proceed to the third phase. Unlike the EDN, there is no retake opportunity for the OSCE in the same year. Students can retake it the following year. To increase the OSCE pass rate, the Ministries of Education and Health mandates that each faculty of medicine organizes a mock OSCE exam in the fourth and fifth years of the second phase to familiarize students with the exam process.

The formative assessment accounting for 10 % of the total score, includes international exchanges, scientific research, dual degree programs, language proficiency, and social activities. Faculties of medicine assess students based on language certificates, internship or social activity certifications, and published papers.

Third phase of medical education in France

Access to the third phase of medicine education is achieved through the second medical education examination. The third phase, also known as the “Residency Training,” lasts from four to six years, students succeed from the second medical education examination enters the one of the 44 medical specialties of their choice (Table 1 ). During this period, students are granted prescription rights and engage in clinical diagnosis and treatment under the supervision of senior physicians. As hospital employees, they receive salaries and paid leaves. Upon completion of residency training, students are awarded the “Diplôme d’Etudes Spécialisées” (DES) [32].

Specialist subjects in the third stage of medical education in France.

| No. | Subject name | No. | Subject name | No. | Subject name | No. | Subject name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allergology | 12 | Digestive surgery | 23 | Emergency medicine | 34 | Neurology |

| 2 | Anatomy and cytopathology | 13 | Dermatology and venereology | 24 | Occupational medicine | 35 | Oncology |

| 3 | Anesthesia and resuscitation unit | 14 | Endocrinology-diabetes and nutrition | 25 | General medicine | 36 | Ophthalmology |

| 4 | Medical biology | 15 | Genetic medicine | 26 | Critical care resuscitation | 37 | ENT and cervical-facial surgery |

| 5 | Maxillofacial surgery | 16 | Geriatrics | 27 | Internal medicine and clinical immunology | 38 | Pediatrics |

| 6 | Oral surgery | 17 | Gynecology | 28 | Medical jurisprudence and medical expertise | 39 | Pneumology |

| 7 | Trauma and bone surgery | 18 | Gynecology and obstetrics | 29 | Nuclear medicine | 40 | Psychiatry |

| 8 | Pediatric surgery | 19 | Hematology | 30 | Rehabilitation medicine | 41 | Imaging |

| 9 | Plastic and reconstructive surgery | 20 | Hepato-gastro-enterology | 31 | Vascular medicine | 42 | Rheumatology |

| 10 | Cardiothoracic surgery | 21 | Department of infectious and tropical diseases | 32 | Nephrology | 43 | Public health |

| 11 | Vascular surgery | 22 | Cardiovascular medicine | 33 | Neurosurgery | 44 | Urology |

-

ENT, ear, nose and throat.

In order to enhance progressively the professional knowledge and clinical skills of the resident doctors, residency training in the third phase includes a foundational stage, an advanced stage and a consolidation stage [33]. The first stage is to instill in the student, in one year, the culture and basics of the specialty. The advanced stage lasts two or three years during which the future doctors study all the fields of the specialty. In the consolidation stage which lasts one or two years, the autonomy of the future doctors will be promoted in order to gradually prepare them for the reality of his future practice.

The student’s knowledge and skills are individually assessed at the end of each of the three phases of the program. These formal assessments are based on the training agreement and the student’s portfolio. They do not preclude other assessments during each phase. It thus provides for a training agreement that specifies the knowledge and skills the student must acquire. This agreement is evolving and personalized as it integrates the student’s preferences for options or cross-specialization training (formation spécialisée transversale, FST). This agreement will be regularly updated. Additionally, a portfolio will compile the student’s training journey along with evaluation elements (including internships).

The curriculum for general practitioners (GPs) during the third phase differs from that of other specialties. GP training typically requires only the foundational and advanced stages, lasting four years. At the end of GP training, students must submit a DES thesis and participate in a defense. The format of the DES thesis is flexible. It can be a research paper, coursework completed during the three-year training period, reports on complex clinical cases, or experiences outside clinical internships. Given their role as primary care providers, the assessment of their lifelong learning capabilities is particularly important [34].

Specialists, on the other hand, must complete all three stages of training, which usually takes four to six years, and students are required to write a doctoral thesis and successfully defend it.

Research capability development in medical education in France

To enhance the research capabilities of medical students, various faculties of medicine also offer parallel Medical-Science Master’s programs, spanning two years and divided into two stages (Master 1, M1, and Master 2, M2) (Figure 1) [35]. Students can apply to take Medical-Science related courses in the second or third year of the first phase. Faculties of medicine select students with strong learning abilities and a keen interest in research to enter the Medical-Science Master’s program based on their application materials and interview results.

Each faculty of medicine determines its specialty direction, curriculum design, as well as teaching content based on its unique characteristics and talent training objectives. With the impact of global public health events like the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of telemedicine and information security has become more prominent, making health informatics a popular major among students in recent years [36]. For example, Sorbonne University School of Medicine offers students three different specialties: biology, health informatics and statistics, and biomedical engineering.

The M1 courses start after entering the second year of PCEM. Students enrolled in the M1 program retain their medical specialty enrollment and complete 60 credits in the M1 program. During the second and third years, students concurrently take theoretical courses related to the Medical-Science Master’s degree and complete four to six months of laboratory internships, learning basic experimental operations. The M2 courses usually start at the beginning of DCEM. Students maintain their medical specialty enrollment while completing M2’s theoretical courses and laboratory internships within one year, totaling 60 credits. The M2 research internship lasts five to six months (30 credits), under the guidance of a mentor. The M2 stage not only involves in-depth theoretical knowledge but also focuses on cultivating students’ critical reading and analytical thinking abilities in scientific research, guiding them in project design, and enhancing their abilities to identify and solve problems. Students who pass the theoretical course exams (written) and defense are awarded the “Diplôme de Master 2 en Sciences Médicales”.

Continuing medical education in France

Legally, France has strict regulations for physicians’ continuing medical education. The French Medical Ethics Code (Le Code de Déontologie) requires physicians to continuously be aware of their needs for progress and improvement in medical and health care [37]. According to the laws and regulations issued by the French Prime Minister’s Office, physicians must enhance their professional capabilities and levels through annual continuing education [38]. Each hospital must establish strict annual continuing education training standards for in-house physicians, with paid training during the continuing education period. These regulations provide substantial institutional support for physicians’ continuing education.

In France, there are generally two ways to obtain continuing medical education. One is through continuing education programs within the faculty of medicine, organized by faculties of medicine across France. The program lasts one to two years, with courses strictly arranged according to university semesters. Physicians participating in these programs must register at the university and can choose between full-time and part-time study. They will receive a continuing medical education diploma from the respective faculty of medicine. The other method is through continuing medical education training organized by medical professional associations, which are less rigorous than those offered by faculties of medicine and have shorter course durations. These courses, co-organized by various medical professional associations, focus more on the cutting-edge theories of the relevant discipline and are sometimes co-organized with faculties of medicine.

In France, relevant institutions evaluate every three years the improvement in practicing capabilities of all physicians obtained through continuing medical education. The evaluation includes continuous training, analysis and assessment of their practice, and risk management. The National Continuing Education Center and the National Health Industry Committee inspect the completion of continuing education training for physicians. Their main purpose is to evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum design and training content in medical continuing education [39]. Additionally, these two national institutions, along with the National Medical Committee, jointly evaluate physicians’ completion of continuing education projects and the degree of improvement in their practicing capabilities every three years, in collaboration with regional health bureaus and provincial medical committees [40].

Reflections on French medical education

The French Ministries of Education and Health play an active role in advancing the elite training of medical talents by setting a unified overall framework for medical education through laws and decrees. In the latest round of medical education system reform, France strengthened communication and consultation between faculties of medicine and national and local public health departments, reformed the examination system, and increased entry paths into medical professions. This reform helps to diversify the educational backgrounds of medical students and facilitates the training of multidisciplinary medical talents to better meet the needs of societal development.

In China, students mainly enter clinical medicine through the national college entrance examination. The channels for transitioning between medical and non-medical specialties are not fully open, leading to a relatively uniform disciplinary background among medical talents. We can draw inspiration from French medical education reforms and open up barriers between specialties to create opportunities for students passionate about medicine. It will enrich the disciplinary backgrounds of medical students and promote the training of diversified and multidisciplinary “Medicine + X” talents.

French medical education not only focuses on cultivating students’ clinical thinking and skills but also provides a platform for students passionate about research. From the first phase, medical students can combine their interests and career plans to minor in Medical-Science Master’s programs, and obtain a Medical-Science Master’s degree during their subsequent medical studies. This not only aids in completing and defending their doctoral projects in the third phase but also lays the foundation for conducting clinical research in diagnosis and treatment, forming a training model for medical scientists.

In China, most medical students engage in research training by research-based learning (RBL) during their spare time, often in fragmented periods. Students usually start the academic master’s program in medicine which lasts three years after completing their undergraduate clinical medicine studies. The French model of Medical-Science Master’s training can provide new insights for medical talent training in China. Since 2010, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine has learned from the French “Medical-Science Master’s Course” and initiated the “Sino-French Cooperation Master’s Degree Program in Life Sciences.” Through “1 year of domestic training + 1 year of overseas training” model, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine has broadened the training channels for comprehensive medical talents, and also created conditions for students to further pursue doctoral studies (PhD) in the future.

Conclusions

With the progress and development of the society, France continuously reforms its elite medical education model, standardizing and regulating the medical education system to cultivate multidisciplinary composite medical talents. The French medical education system and its reforms provide inspiration and reflection that will help China in the construction of new medical disciplines, achieving the goal of cultivating innovative and multidisciplinary top-tier medical talents.

Funding source: Shanghai Health Commission Human Resources

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-99

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the authors for their suggestions and hard work in writing this manuscript.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author(s) have (has) accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Wenhui Zhang and Xin Chen wrote this manuscript. Huiyun Yuan and Yong Zhang put forward many suggestions for the conceptualization of this manuscript. Dominique Bertrand and Gilbert Vicente provided a large amount of legal provisions and informations for this manuscript. Wenhui Zhang revised and reviewed the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by grant from Shanghai Health Commission Human Resources (No. 2021-99).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Arrêté du 4 novembre 2019 relatif à l’accès aux formations de médecine, de pharmacie, d’odontologie et de maïeutique. NOR: ESRS1930498A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000039309386/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

2. Li, M, Wang, WM, Xie, AN. Thoughts on the problems of undergraduate clinical education in China. Medical and Philosophy 2022;43:1–6.Search in Google Scholar

3. Deng, WJ, Xia, OD, Huang, W. Problems and strategies of training medical students in China. Medical Education Research and Practice 2018;26:9–12.Search in Google Scholar

4. Opinions on deepening medical education reform and development through medical-educational collaboration. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2017; n° 63 [Online]. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-07/11/content_5209661.htm [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

5. World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Shanghai: World Health Organisation; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

6. Bagein, G, Costemalle, V, Deroyon, T, Hazo, JB, Naouri, D, Pesonel, E, et al.. L’État de santé de la population en France [Online]. https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/publications-communique-de-presse/les-dossiers-de-la-drees/letat-de-sante-de-la-population-en [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

7. L’Activité en hospitalisation complète et partielle. Les établissements de santé, édition 2020 [Online]. https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/publications-communique-de-presse/les-dossiers-de-la-drees/letat-de-sante-de-la-population-en [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

8. Démographie des professionnels de santé au 1er janvier 2023 [Online]. https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/communique-de-presse-jeux-de-donnees/demographie-des-professionnels-de-sante-au-1er-janvier-2023 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

9. Arnaud, F, Lefebvre, G, Mikou, L, Portela, M. Les dépenses de santé en 2021: Résultats des comptes de la santé- édition 2022 [Online]. https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/publications-documents-de-reference-communique-de-presse/panoramas-de-la-drees/CNS2022 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

10. Comiti, VP. Histoire des universités de médecine: quelques jalons. Les Tribunes de la santé 2007;16:19–24. https://doi.org/10.3917/seve.016.0019.Search in Google Scholar

11. Barber, RM, Fullman, N, Sorensen, RJD, Bollyky, T, McKee, M, Nolte, E, et al.. Healthcare access and quality index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a nouvel analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2017;390:231–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30818-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Ordonnance n°58-1373 du 30 décembre 1958 relative à la création de centres hospitaliers et universitaires à la réforme de l’enseignement médical et au développement de la recherche médicales [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000886688/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

13. Shanghai Ranking. 2023 global ranking of academic subjects [online]. https://www.shanghairanking.com/rankings/gras/2023/RS0220 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

14. Code de l’éducation, Chapitre II: Les études médicales. (Articles L632-1 à L632-13) [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGISCTA000006166667/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

15. Arrêté du 22 mars 2011 relatif au régime des études en vue du diplôme de formation générale en sciences médicales. NOR: ESRS1106857A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000023850797/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

16. Arrêté du 28 octobre 2009 relatif à la première année commune aux études de santé. NOR: ESRS0925329A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000021276755/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

17. L’Arrêté du 21 décembre 2021 portant modification de plusieurs arrêtés relatifs aux formations de santé. NOR: ESRS2138080A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000044616269 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

18. Collet, L. Numerus clausus et accès aux études de médecine: bases juridiques. Les tribunes de la santé 2019;59:47–61. https://doi.org/10.3917/seve1.059.0047.Search in Google Scholar

19. Chen, X, Sun, YL, Huang, G. Reflection on the overall setting of the French medical education system. Chin J Med Edu 2023;43:67–71.Search in Google Scholar

20. Bertrand, D, Pataud, G, Rabiano, L, Chen, X. La procédure d’autorisation d’exercice pour les médecins à diplôme hors union européenne depuis la loi de financement de la sécurité sociale de 2006. Cah Fonction Publ 2016;367:65–9.Search in Google Scholar

21. Queneau, P, Ourabah, R. Rapport 23-11. Les zones sous-denses, dites « déserts médicaux », en France. États des lieux et propositions concrètes. Bull Acad Nati Med 2023;207:860–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.banm.2023.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

22. Ministère du travail de la santé et des solidarités. « Ma santé 2022, un engagement collectif» [Online]. https://sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/ma_sante_2022_pages_vdef_.pdf [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

23. LOI n° 2019-774 du 24 juillet 2019 relative à l’organisation et à la transformation du système de santé. NOR: SSAX1900401L [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGISCTA000038824774 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

24. Bertrand, D, Tillement, JP, Cailler, S, Collet, L, Dubois, G, Folliguet, M, et al.. Rapport 23-03. Rapport interacadémique. Conditions d’accès au plein exercice en France des chirurgiens-dentistes, des pharmaciens et des médecins à diplômes européens ou à diplômes hors Union européenne. Bull Acad Nati Méd 2023;207:534–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.banm.2023.03.015.Search in Google Scholar

25. Chen, X, Rubiano, L, Bertrand, D, Artigou, JY, Toupillier, D. La Procédure d’autorisation d’exercice en cardiologie de 2007 à 2015. Arch Mala Cœur Vaiss Prat 2017;2017:22–7.10.1016/j.amcp.2016.12.011Search in Google Scholar

26. Brunn, M, Genieys, W. Admission into healthcare education in France: half-baked reform that further complicates the system. Med Teach 2022;45:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2022.2151885.Search in Google Scholar

27. Fabiani-Salmon, JN. Histoire de l’internat des hôpitaux (1802–2005). Bull Acad Nati Méd 2022;206:1269–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.banm.2022.07.029.Search in Google Scholar

28. Cohen Aubart, F, Roux, D. La réforme du deuxième cycle des études médicales en France: risque ou opportunité? Rev Med Interne 2021;42:149–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2020.12.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Décret n° 2021-1156 du 7 septembre 2021 relatif à l’accès au troisième cycle des études de médecine. NOR: ESRS2112241D [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGIARTI000044027637/2021-09-09/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

30. Arrêté du 21 décembre 2021 relatif à l’organisation des épreuves nationales donnant accès au troisième cycle des études de médecine. NOR: ESRS2138083A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000044572679 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

31. Arrêté du 2 septembre 2020 portant modification de diverses dispositions relatives au régime des études en vue du premier et du deuxième cycle des études médicales et à l’organisation des épreuves classantes nationales. NOR: ESRS2018628A [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000042320018 [Accessed 23 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

32. Mouthon, L. La réforme du troisième cycle des études médicales: quelle évolution pour la médecine interne? Rev Med Interne 2017;38:355–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2017.03.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Le Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur et de la recherché. Réforme du 3e cycle des études de médecine : une formation rénovée, modernisée et simplifiée [Online]. https://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/fr/reforme-du-3e-cycle-des-etudes-de-medecine-une-formation-renovee-modernisee-et-simplifiee-49202 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

34. Bertrand, D, Bergoignan-Esper, C, Bousser, MG, Caton, J, Hauet, T, Le Gall, JR, et al.. Avis 23-08. Quels rôle et place pour le médecin généraliste dans la société française au XXIe siècle ? Du médecin traitant à l’équipe de santé référente. Bull Acad Nati Med 2023;207:706–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.banm.2023.04.016.Search in Google Scholar

35. Scherlinger, M, Bienvenu, TCM, Piffoux, M, Séguin, P. Le double cursus médecine-sciences en France, Etat des lieux et perspectives. Méd/Sci 2018;34:464–72. https://doi.org/10.1051/medsci/20183405021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Moulin, T, Simon, P, Staccini, P, Sibilia, J, Diot, P. Santé numérique - télémédecine : l’évidence d’une formation universitaire pour tous les professionnels de santé. Bull Acad Nati Med 2022;206:648–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.banm.2022.04.011.Search in Google Scholar

37. Article 11 du code de déontologie médicale. Titre 1: Devoirs généraux des médecins [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000006680509/2021-12-31 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

38. Loi n°2002-303 du 4 mars 2002 relative aux droits des malades et à la qualité du système de santé. NOR: MESX0100092L [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFSCTA000000889846 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

39. Décret n°2019-17 du 9 janvier 2019 relatif aux missions, à la composition et au fonctionnement des Conseils nationaux professionnels des professions de santé. NOR: SSAH1808219D [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000037972054/ [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

40. LOI n° 2009-879 du 21 juillet 2009 portant réforme de l’hôpital et relative aux patients, à la santé et aux territoires. NOR: SASX0822640L [Online]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000020879475 [Accessed 20 Jun 2024].Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Evolving landscapes in global medical education: navigating challenges and embracing innovation

- Review Articles

- Embarking on the era in new medicine: reshaping the systems of medical education and knowledge

- Aligning the education of medical students to healthcare in the UK

- Characteristics and considerations of French medical education

- Research Articles

- “Global challenge program” projects themed on preventing zoonosis: developing One Health core competences in medical students at SJTU

- Innovative exploration of designing the ‘Host Defense and Immunology’ course based on the concept of seamless learning

- Comparing the effects of blended learning and traditional instruction on “Medical Genetics and Embryonic Development” in undergraduate medical students: a randomized controlled trial

- The application of the “PICO” teaching model in clinical research course for medical students

- Factors bridging medical graduate students’ training and future academic achievements of dermatologists in China

- The teaching design and implementation of “Helicobacter pylori” in medical microbiology

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Evolving landscapes in global medical education: navigating challenges and embracing innovation

- Review Articles

- Embarking on the era in new medicine: reshaping the systems of medical education and knowledge

- Aligning the education of medical students to healthcare in the UK

- Characteristics and considerations of French medical education

- Research Articles

- “Global challenge program” projects themed on preventing zoonosis: developing One Health core competences in medical students at SJTU

- Innovative exploration of designing the ‘Host Defense and Immunology’ course based on the concept of seamless learning

- Comparing the effects of blended learning and traditional instruction on “Medical Genetics and Embryonic Development” in undergraduate medical students: a randomized controlled trial

- The application of the “PICO” teaching model in clinical research course for medical students

- Factors bridging medical graduate students’ training and future academic achievements of dermatologists in China

- The teaching design and implementation of “Helicobacter pylori” in medical microbiology